"We Cannot Sit Down Quietly and See our Children Starve"

An Economic Portrait of a Nineteenth-Century Polygamous Household in Utah

Sherilyn Farnes

Sherilyn Farnes, "'We Cannot Sit Down Quietly and See our Children Starve': An Economic Portrait of a Nineteenth-Century Polygamous Household in Utah," in Business and Religion: The Intersection of Faith and Finance, ed. Matthew G. Godfrey and Michael Hubbard MacKay (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 197–228.

In early August 1870, Amasa Lyman received an unexpected letter from Eliza and Caroline Partridge Lyman, the mothers of ten of his children. Written on 31 July 1870, the letter began, “You will perhaps be somewhat surprised at receiving a letter from us, but we are driven by stern necessity to do something. We cannot sit down quietly and see our children starve.” Eliza, who wrote the letter, and who at times even wrote in first person singular, stated her case, “We are living now by borrowing of one neighbor then another, without any prospect of ever paying which I consider not a very creditable way of doing, It seems to me that there is no need of all this destitution, that we are not so much worse off than other folks with regard to property, and can you not devise some plan whereby your family can be fed and clothed and have some little chance for an education?”[1]

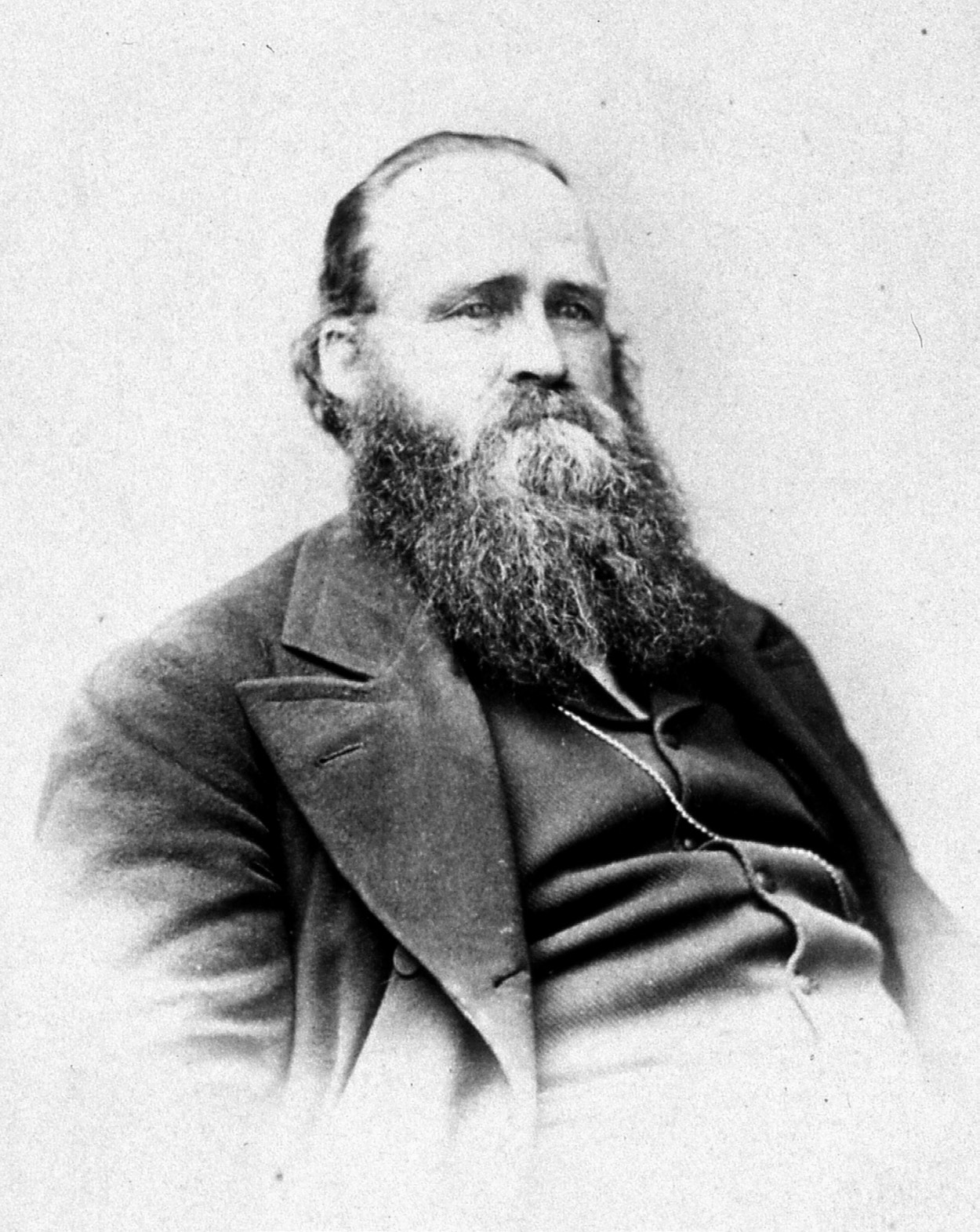

Amasa Lyman. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

Amasa Lyman. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

What prompted these sisters to write such a letter? Both Eliza and her sister Caroline had married Apostle Amasa Lyman twenty-six years earlier, in September 1844.[2] However, Amasa had left the Church to accept a leadership position in the Godbeite Church in 1870.[3] Following either his disaffection with the Church in 1867 or his excommunication in 1870, his relationship with the Partridge sisters seems to have become strained and distant, leading to separation.[4] Instead of the usual familiar “Dear Friend” or “Dear Amasa” with which the Partridge women had typically begun letters in years past, they began this 1870 letter by addressing him as “Dear Brother Lyman.” Apostasy was sufficient cause for divorce in nineteenth-century Utah if parties desired it, and marriages could be dissolved by mutual consent. Several family sources indicate that the Partridge sisters eventually divorced Amasa. Even in cases of divorce, however, fathers were responsible to continue to provide for their children, and ex-wives sometimes asked for, demanded, or pleaded for economic support.[5]

The larger issue this letter represents is not whether the Partridge sisters had divorced Amasa by this point. Instead, the problem seems to have been a continuation of what was a theme throughout their entire married lives: inconsistent temporal support from their husband. Amasa was a man gifted in preaching and administrating, though not in providing for his large family. As one biographer noted, almost in his opening paragraph, “It would be difficult to find any other church leader who took so little opportunity to permanently establish himself and his loved ones on a more firm economic foundation. [Amasa Lyman’s] life is a study of dedication to that church, but clearly sometimes at the expense of family comfort and well-being.”[6] While plural marriage is often viewed as lessening the economic disparity in nineteenth-century Utah, in some cases, such as Amasa’s, even his previously financially secure wives often struggled repeatedly to provide for their families.[7]

As historian Jessie Embry wrote of polygamy, “Understanding the diverse experiences of individual families is an antidote for oversimplified conclusions or stereotypes.”[8] This paper attempts to add to the scholarship on the various economic experiences in polygamy by examining one Utah household in detail. Referring to the intersection of law, religion, and individual lived experience, Kathryn Daynes argued in her book More Wives Than One: Transformation of the Mormon Marriage System, 1840–1910—a brilliant mix of personal stories and broader applications—for more case studies when she wrote, “individual-level data on behavior need to replace generalizations about families.”[9] Both Daynes and Embry study broad patterns in polygamy while not losing sight of the individuals who make up those data sets. This paper analyzes the individual-level data of the economic situation of the household of Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman, a plural wife of Amasa Mason Lyman. To contextualize her experiences, some facts of the lives of other wives and children of Amasa will also be included.[10]

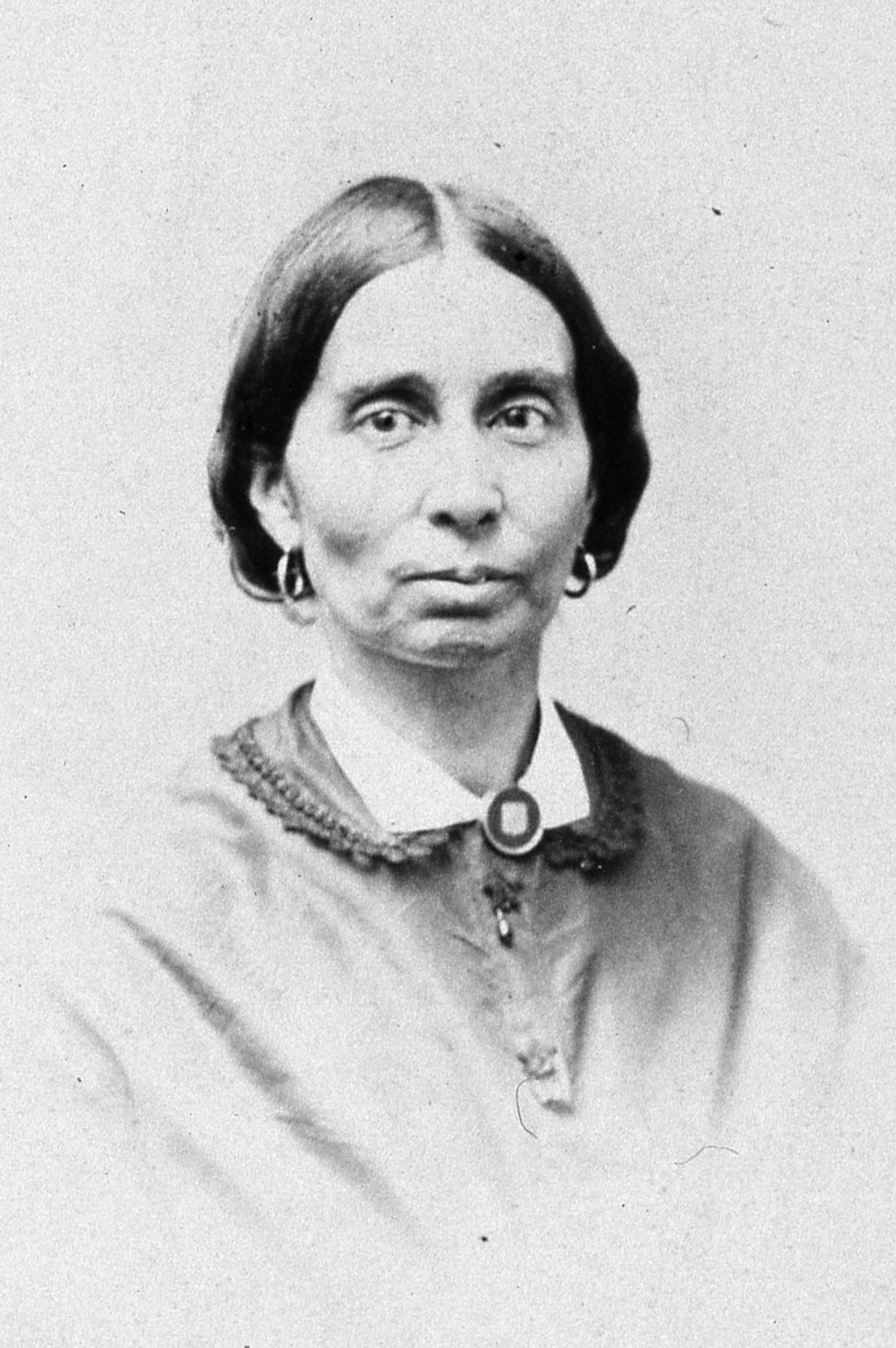

Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

In many ways, Eliza and her sisters married to Amasa were typical of those who entered plural marriage, if such patterns can be called so, since the backgrounds and experiences of those who entered plural marriage were diverse.[11] Between 1860 and 1900, about three out of four Saints in Utah resided in Latter-day Saint villages or rural areas, while the remainder lived in the Salt Lake area.[12] The Partridge sisters married to Amasa usually lived in such a village or rural area. They themselves were also fatherless and not economically well off when they entered plural marriage—women in these two groups were more likely to enter plural marriage, according to historian Kathryn Daynes.[13] Like many in the study of Manti by Daynes, the Partridge sisters married during the economically difficult years of 1844 to 1859.[14] Sources indicate that they also eventually divorced Amasa, a not uncommon feature of plural marriages, because of his apostasy.[15] Furthermore, Eliza had already been married to Joseph Smith for eternity, so her remarriage to Amasa Lyman was for time only, a typical choice for a widow remarrying into a plural marriage.[16] Although she did everything she could to contribute to the household economy, in expecting support from Amasa, Eliza was aligned with the rest of society in Utah in which a man who fathered children was expected to support them and their mother.[17] Additionally, Eliza, like many plural wives, at least partially if not completely supported herself; some worked outside the home.[18]

In the aforementioned 1870 letter, Eliza and Caroline informed Amasa that, among other necessities, their children—a total of eight minor children—who were also his children, needed food.[19] Eliza’s letter, in fact, reflects several areas in which her economic situation affected her life’s circumstances. She wrote that she had “no Husband to lighten my cares, no Father to provide for my children or to help me in rearing them, no home that I can call my own, no means that I can command to support myself and Family, all are gone, gone.” While strict economic realities matter—how much food one has, where one lives, who is providing—the mental, emotional and psychological impact of one’s financial well-being on an individual is perhaps even more critical: not knowing if there will be enough food to eat or wood to burn today or tomorrow or next week or next month or next year affects one’s daily outlook. Because of that insight, this paper focuses not just on the physical reality of their situation, but specifically on Eliza’s yearnings relating to economic stability in the following five areas: a consistent external provider, the assistance of others, the ability to provide for herself, the ability to share temporal resources with others, and a stable or comfortable home. I will explore the ways in which she yearned for each of these, and the varying degrees with which these yearnings were fulfilled in her life.

Early Life of Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman

Insights into Eliza’s early life help illustrate how her formative childhood years differ greatly in economic stability from her married life. Born in Painesville, Ohio, in 1820, to Edward and Lydia Clisbee Partridge, she was the oldest of seven children. Her father owned several pieces of land—even though he was primarily a hatter—including three plots on the Main Street of Painesville, Ohio, and over 130 additional acres in two different parcels of land elsewhere.[20] Eliza’s sister Emily later described the home the Partridge children grew up in as having “rose bushes and sweet-brier” in front, and in the back “an arbor, or summer-house . . . with seats on both sides . . . covered with grapevines with clusters of blue grapes hanging among the leaves and twigs.” She also recalled flowers of many kinds, including “daffodils, blue bells, lilly, iris, snowballs, etc.” lining the path between the house and arbor. Other foliage around the home included a “delicious cling-stone peach,” a cherry tree, and a “large weeping willow near the shop.” The shop adjoined Partridge’s hat store next to the street. A large frame barn and a “yard full of black fowls” with a cow and horse completed her word picture of their childhood home.[21] The first ten years of Eliza’s life were a time of prosperity for her family.

In late 1830, her family joined what later became called The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and moved to Missouri within the year. After traveling to Missouri in the summer of 1831 ahead of his family, her father Edward recognized that their temporal circumstances would be changing and wrote to his wife Lydia, “We have to suffer & shall for some time many privations here which you and I have not been much used to for years.”[22] The Partridges settled about a half mile west of the town square in Independence. In the first two years in Jackson County, Partridge purchased over two thousand acres of land, which he distributed to the Saints.[23] In July 1833 tensions that had been growing between the Latter-day Saints and other settlers came to a head. An angry mob tarred and feathered Partridge and another church member, destroyed the Church’s printing press, and demanded that the Saints leave Jackson County. Faced with no other choice, they reluctantly agreed to leave, and following further violence later that year fled north to Clay County.[24]

While in Clay County from 1833 to 1836, Eliza’s family shared a log cabin with the Corrill family. Eliza’s sister Emily remembered that “the rats and rattlesnakes were too thick for comfort. There was a large fireplace in the one habitable room. . . . The weather was extremely cold, so cold that the ink would freeze in the pen as father sat writing close to the fire.”[25] During this time period Partridge served two consecutive missions in 1835 and then remained in Kirtland the following winter to attend the School of the Prophets and the Kirtland Temple dedication before returning home. Soon after his arrival in Missouri, the Partridges and the rest of the Saints peacefully left Clay County for Caldwell and Daviess Counties. Again Partridge purchased land on behalf of the Church in his role as bishop and distributed it to the other Saints. By 1838 he “held eight hundred and sixty eight acres of land in Caldwell county,” as well as a “title to forty acres of land in Clay Co. and more than four fifths of the lots in the town of Far West, Caldwell Co.”[26] Partridge wrote a letter to his younger brother in 1837 stating, “I have reserved a lot or two for you if you want them.”[27] Clearly Eliza grew up in a household of one who managed exceedingly large amounts of property on behalf of his fellow Saints. However, as conflicts between the Latter-day Saints and their neighbors again escalated, armed mobs drove the majority of the Saints from the state in the winter of 1838–1839.[28]

Most church members fled to Illinois, where they began building up a new city named Nauvoo. Within two years of his departure from Missouri, Partridge died in Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1840 while trying to build a home for his family.[29] A few years later, Eliza and her sister Emily married Joseph Smith as plural wives in 1843 but did not live long with him. Following Joseph Smith’s death in 1844, Eliza and her sister Caroline both married Amasa Lyman in the fall of 1844.[30] Less than eighteen months later, they had to flee again, this time leaving Nauvoo in Amasa Lyman’s pioneer company to Utah. Eliza’s trip to Utah lasted from 1846 to 1848, but she and her sister shared a wagon to themselves, hinting at Amasa’s ability to provide at least initially. She gave birth twice along her way. Upon her arrival in Utah, her initial impression was not favorable. She noted wryly in her journal: “I do not think our enemies need envy us this locality or ever come here to disturb us.”[31]

The month following Eliza’s arrival in Salt Lake City, Amasa was called to go to California on an exploratory mission to collect tithing and to meet with the Saints. He left in April 1849 and returned in September 1850.[32] He was then called to help settle San Bernadino, California, between 1851 and 1857.[33] A series of Eliza’s journal excerpts from April 1849, the month Amasa first left for California, gives an idea of her initial economic situation in the Rocky Mountains: “We are spinning some candle wick which we shall try to sell for bread stuff.” “Moved on to our lot to live in wagons again. We are 4 in the family, Sister Caroline, Brother Frederic, myself and babe. I sold a ball of candle wick for three and a half quarts of corn, sold another ball for three and a half quarts of meal, which has to be divided between Pauline Lyman, Mother and my family.” “Sister Emily brought us 15 lbs. of flour, said President Young heard we were out of bread, and told her to bring that much although they have a scant allowance for themselves. I sincerely hope I may be able to return it before they need it.” “Carded and spun three balls of candle wick. Br. Frederic setting out fruit trees on the lot. Jane James, a colored woman, let me have about 2 lbs of flour, it being about half she had.” “Samuel White gave Paulina a dollar to buy corn with. Sister Caroline gave two and a quarter dollars for a calico dress pattern, gave Charles Burke 25 cts for his trouble in getting it for her.”

In May 1849, while on a short trip visiting sister wives and their families in Cottonwood, she wrote, “Heard from home; learned that Sister Caroline had taken a school about ten miles north of us because she has nothing to eat at home and is under necessity of doing something, as there is nothing to be bought although we have the money to pay for flour if there was any.” [34] Letters from Amasa’s associates indicate that the family’s economic situation by the fall was comfortable, though Eliza’s journal entry for 2 September 1849, stated, “We have very cold nights, and our house, if house it can be called, is very uncomfortable, the logs laid up, part of the roof on, and a very little chinking in it.”[35] In Utah, the economic situation of Eliza, her sisters, and their children fluctuated greatly, sometimes parallel with the ups and downs of the general population and sometimes at variance with it.

Yearning for a Consistent Provider

While several themes appear in the 1870 letter mentioned above, Eliza’s yearning for a consistent provider appears prominently. Eliza pointed out, “I think you can testify that during the last twenty four or five years we have borne poverty and privations of almost every kind without complaint and have done all in our power to make your life as <happy as> possible under the circumstances and be in truth a help to you, and it is not with a desire to add one sorrow to your heart that we write now, but to let you know how we are situated and see if there cannot be something done to relieve our wants a little.”[36] This line implies that he didn’t know the economic situation of his family, but that he might be willing to help once he was made aware. Eliza worried she might have “said too much,” but explained, “I feel almost desperate sometimes, my health is gone and old age comes creeping on, and now when I most need some one to lean on, I find myself standing alone.” Not only was she bereft of a husband’s help, she also plaintively noted that “the weight of responsibility that rests upon me is sometimes <almost> more than I can bear, but I put my trust in the Lord knowing that when all others forsake us he is still our Friend.” The sisters then jointly closed the letter with the optimistic, “Hoping to hear from you soon we subscribe ourselves your Friends, Eliza M. Lyman, Caroline E. Lyman.”[37]

Amasa likely would have received the letter within the week. Four days later, he noted in his journal, “Wrote to Eliza & Caroline.” He then continued, “and to Marion [a son by another wife] sending him a draft of one hundred dollars.”[38] While it is unclear if he corresponded with Marion to obtain money for the sisters or not, it seems likely that he did not send it to the Partridge sisters, though the return letter from Marion does not indicate definitively either way.[39] This is not to say he did not help them at all, for “later developments indicate [that the Partridge sisters] did draw flour from Lyman’s gristmill for a time,” though that might have been in repayment for his sons working for him.[40] Yet at one point after the Partridge sisters separated from him, rumors circulated that Amasa planned to stop giving them flour from his gristmill. Whether or not these speculations were true, one of Amasa’s sons from another wife was concerned enough that he wrote his father a letter in December 1870 mentioning the rumors in circulation and their negative effect on Fillmore residents’ opinion of Amasa.[41] This seems to imply that Amasa offered the flour to them not as payment for work but out of a willingness to support them.

Eliza yearned to have the ideal of a consistent husband-provider who would live with her or nearby and care for all of his families well and equitably. She rarely if ever had that privilege. Instead she made do with what she had. Amasa had eight wives and almost forty children, so his immediate family included nearly fifty people![42] Even though some of his children died young, he also felt at least some responsibility for other people associated with his family, such as his widowed mother-in-law, Lydia Clisbee Partridge Huntington.[43] His economic burden is not to be underestimated, but unfortunately, he struggled to provide.

It is important to note, however, that Amasa likely received much pressure to take on plural wives because of his high Church position.[44] As Daynes notes in her study of plural marriage in Manti, “For the most part, polygamists were wealthier than other men, and those with a higher church rank were more likely to have plural wives.” In fact, “church rank was more important than wealth in predicting a plural marriage.” Thus, some men who were not exceptional providers perhaps felt pressured to enter plural marriage because of their Church rank rather than because of an ability to provide for other women and children.[45] Interestingly, of those men Daynes studied in Manti, even though they may have had more wives over time, the overwhelming majority of those in plural marriage chose to have only two wives at a time, a significant difference from Amasa’s eight wives. In fact, Daynes notes that less than five percent of the men in Manti had five or more wives at the same time.[46] Additionally, those living longer in Utah tended to have greater wealth, while Amasa spent much of his time in California, sometimes to his financial loss.[47]

In the introduction to the published version of Lyman’s diaries, the editors noted that when he arrived in Missouri in the 1830s, “he found temporary employment but discovered he was not very good at menial tasks. It foreshadowed his lifelong challenge in providing for his family when most men did so through manual labor and his talents lay elsewhere. Even in places like San Bernardino, where he lived longer than a few months, he was an administrator. He could convert people and manage them, however fleeting the temporal compensation was for that.”[48] Similarly, the editors stated that after he returned from California, where he collected tithing, he “found his family impoverished, but decided there was not much he could do about it, as part of the pattern whereby he would visit occasionally but not linger. If he was not sent abroad, he would travel through the Mormon corridor on his own initiative, speaking and visiting with the Saints in their communities.”[49] After one departure, Eliza recorded in her journal, “Some time in the spring of 1860, Br. Lyman started on a mission to England, leaving us to do the best we could, which was not very well, as we were as usual in very poor circumstances. We had poor health and no means to help ourselves with.”[50]

Sometimes, however, he was able to send money or supplies while he was away. Such help arrived often enough that in an 1854 letter Eliza wrote that her family expected to have flour the way they always did—a husband, though distant, provided it.[51] He might send gold dust or cash from California during the 1850s.[52] An 1850s letter from Caroline indicated that they had “plenty to eat,” but, while a positive sentiment, it makes one wonder if she only specified that because it was not always the case.[53] Amasa also may have arranged for others to help care for his families in his absence, but even the best-laid plans could go astray. Eliza wrote, “A man may make his calculations and lay his plans for his family to work by when he is gone, but circumstances change so that is it almost impossible to live up to them, which places a family sometimes in a very awkward situation.”[54] One additional complicating factor with plural families was how resources were divided among the different wives. In her book Mormon Polygamous Families: Life in the Principle, Jessie Embry discusses how the division of goods could be a source of disagreement and contention, as a husband might divide his resources evenly between his wives, or divide them based on a variety of factors: the number of children each wife had, the number of children at home, the number of children at home who were too young to work, the wives or children whom he loved most, or the ones most in need. Each husband divided differently, and his methods might change over time.[55]

During one of Amasa’s absences, Eliza recorded on 3 October 1849 the distribution of goods he sent from California:

D. Frederic divided the goods that Bro. Lyman sent; 11½ pounds of coffee to each woman of the family, counting S. White and wife and Sarah Clark in the family; 13 lbs. of sugar, less than a pound of tea; 18 yards of cotton cloth to the most of us, one bolt of calico each. Lydia, one bolt, mother a half bolt, Brother Tinney one bolt, John Gleason one bolt. he also sent one bolt pants cloth, one doz. hickory shirts, one bolt white flannel, one red and two bolts of blue drilling which has been divided into dress patterns of which we each took one, that is, seven of us. I let mine go to Sarah Clark to pay for one that I had been under the necessity of getting from her before the goods came.[56]

David Frederic was a man about eleven years Eliza’s senior who had been “spiritually adopted” by Amasa Lyman as a son under the practice of “spiritual adoption” in place in Nauvoo. Since individuals could only be sealed to others who had accepted the gospel message, converts with parents who rejected the restored gospel could be sealed to unrelated Church members in child-to-parent relationships. Scholar Jonathan Stapley noted that “adoption practice and theology served as an important nexus in organizing migration to the Great Basin.”[57]

Instead of just noting that she had received items from Amasa in California, Eliza specifically mentions not only that “D. Frederic” divided the goods, but how much each person received. Was this perhaps a subtle reference to her opinion of the division of the goods or was it simply the recording of an event that occurred and not intended as criticism? Or was it recorded to serve as a reference of the equitable division of goods, should a discussion arise in the future? It was not uncommon for plural wives to feel, even if just at times, that other members of the family were being taken care of better than they were. Eliza expressed a few years later in a letter to Amasa that “I have lived without bread when some of the family had bread to throw to the pigs, and can do it again if necessary.”[58] One might suspect that the first wife was treated the best, but Marion, a child of Amasa’s first wife, remembered, “Our family was always poor and pinched” and said of his mother, “A more frugal woman never lived.”[59] While not speaking to the exact division of goods, such comments suggest again that Amasa struggled to provide for all of his families.

Even though Amasa did not consistently provide well when present, he appears to have attempted to do so, at least until the 1860s. Around that time, Eliza wrote that his behavior had changed, and although Amasa was with his families, he did not exert himself in their temporal behalf: “Br. Lyman and part of his family moved to Fillmore. . . . [He seemed to feel uncomfortable.] I did not know what was wrong with him, but I could see that he was very unhappy. He left his family mostly to their fate, or to get along as best they could, although he was with them.”[60] Sadly, Eliza and her sister wives weren’t unique in needing to help provide for themselves. Jessie Embry’s study of 225 plural wives found that “almost 9 percent of the wives received no support from their husbands and 3 percent received only minimal support and basically cared for themselves and their families.” Thus, about one in ten plural wives in her focus group essentially supported themselves.[61]

Receiving Assistance from Others

In addition to—or often instead of—Amasa, Eliza, her sisters, and his other wives often relied on other family members for financial or temporal support. Eliza’s younger brother Edward Partridge assisted greatly. He was only fifteen when they arrived in the valley, but Eliza’s journal reflects his help in a variety of ways: in the span of less than a week in June 1849 she noted him going after livestock, building a hen house, and hauling logs to the mill to be split.[62] His departure a few years later for a mission left her worried for her own welfare. She noted on 7 April 1854 that he was “called to go on a mission to the Sandwich Islands, which will leave us without man or boy to do anything, but it is all right.”[63] Though trying to appear resolute, a sense of foreboding is apparent in the entry. Emily, Eliza’s only living sister not married to Amasa, and Emily’s family also sometimes helped, such as with the flour mentioned above. In December 1879 Eliza wrote that she had “Received a present of ten dollars in money from my sister Emily’s children.”[64]

Eliza’s own children also substantially contributed as they grew older. Since most plural marriages weren’t companionate marriages, plural wives often “intensified the strength of the bonds they forged with their children.”[65] Such strengthening of bonds likely both contributed to and was the result of the temporal support of mothers by their children. When Eliza’s oldest son Platte was called on a mission, it was a troubling financial blow. After returning from her 1867 trip to Salt Lake City to see Platte married and off on his mission to England, she wrote, “I felt as if I were returning from a funeral. I had a family on my hands, but had no one to provide for us. Brother J. V. Robison and wife and brothers Albert and Alonzo were very good to me. They brought me many things for my comfort and cut my wood which was a great comfort in my helpless situation. I always think of them with feelings of gratitude.”[66] Perhaps compounding her sense of loneliness was the fact that Amasa had been dropped from the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles less than two weeks before Platte’s marriage, and if not already before then, her relationship with him—including his financial support—may have begun to dissolve.

Eliza’s other son, as well as her daughters, also provided financial assistance. In August 1876, she wrote that her nineteen-year-old son Joseph looked for work “as we are out of bread and have no way to get it.” He rode his horse over one hundred miles to Cottonwood in order to find work earning one bushel of wheat a day. He returned about a month later, having milled his wheat, “which was a great blessing to us all as my sister Caroline was also out of flour.”[67] As his brother Platte was on a mission, Joseph was likely his mother’s primary provider at the time. A few years later, in 1883, Eliza, then in her early sixties, wrote that her two living sons, “Joseph and Platte, furnish my provisions and try to make me as comfortable as they can.”[68] She also recorded specific gifts: Joseph “gave me two pair of shoes,” “sent me 25 dollars in money,” while Platte “presented me with 10 dollars in cash,” “gave me gingham for a bonnet,” “gave me 5 dollars, also syrup and flour.”[69] Other wives’ children also assisted both their mothers and their “aunts” (a common title for their father’s other wives). A letter from Amasa to his wife Paulina in 1870 indicated that Amasa would have a hard time getting bread or flour to her that winter and he wondered if Oscar, her twenty-two-year-old son who had married a year and a half ago, could not figure out how to get some so Amasa didn’t have to take other sons out of school to haul flour the great distance to Paulina’s town.[70]

When no family could help, Eliza often was forced to rely on the kindness of friends. She mentions repeatedly in her journal several longtime friends who assisted over the years, including Daniel P. Clark and his wife, the former of whom may have also been “spiritually adopted” by Amasa.[71] Not everyone was so helpful however. It is possible that some neighbors grew frustrated at Amasa’s lack of providing for his families. As she lamented in a letter to Amasa, “one thing I do know, and that is that <some> persons profess great friendship for a man when he is present, and make him believe they would do almost any thing for him or his family but as soon as he is gone they seem to have forgotten that they ever knew you I believe the most are of this class, or at least I find them so.”[72] Yet so very often she survived in part because of the kindness of friends. For example, in December 1879, she wrote in her journal, “Yesterday Brother George Lovell brought me some wood on his shoulders from his place as he saw I was out.”[73]

At times she and her family also received Church resources, not only when Amasa was absent, but also when he was present, since Church members helped support apostles in their ministry. For instance, when Amasa moved to Fillmore in the 1860s on assignment from Brigham Young, local Church members offered to help build houses for his wives. Unfortunately, such efforts took time and energy, the latter sometimes waning over the former.[74] Also at times when Amasa was absent, the Church helped to support his families. Church leaders had created a Mission Fund in 1860 to which Church members could contribute money, food, goods, or clothing to help support missionaries’ families while their providers were away. Later on, “missionary gardens and farms” helped to support the families. Some sources also state that local Church leaders theoretically bore the responsibility for providing for the families of absent missionaries, but with the understanding that the missionaries would leave their families in the best financial situation possible before they left.[75]

Eliza noted having to call occasionally upon the Mission Fund. In August 1860, Eliza noted the birth of her daughter, Lucy Zina, a challenge compounded by the fact that “at this time my sister Caroline was very sick in the next room, and had been for nearly two months. She had a babe who was also very sick. We had to have watchers every night for them and girls to do the work, and not even flour in the house to eat, or soap to wash our clothes with.” With no other avenue of help, Eliza admitted that they “were at last reduced to the necessity of calling on the Missionary Fund for help to take us through our sickness.” She then said, “This is always very trying to me,” an indication that this was not the first request for assistance. Eliza noted reluctantly, “To ask help is far from being pleasant to me, and I do hope if ever I do leave this state of existence that I shall find myself situated a little changed from what I have had here.”[76]

Church leadership also watched over and helped to care for the Partridge sisters and presumably some of Amasa’s other wives after he left the Church. In 1873, just a few years after Eliza wrote the 1870 letter with which this article began, correspondence between Bishop Thomas Callister in Fillmore and Brigham Young indicated that the Church was helping to provide for the three Partridge sisters who had married Amasa: Eliza, Caroline, and their youngest sister, Lydia, who had married him in 1853.[77] This assistance included providing homes for them.[78] In her later years, Eliza noted, “Received a letter from Pres. J. F. Smith, also a present of an order on the Tithing Office of 200 dollars from the First Presidency.”[79]

Ironically, one wonders how much of this hardship might have been avoided had Amasa paid better attention to his family’s economic situation when he was serving missions. Apparently while on his European mission Lyman “assumed, perhaps naively, that his family would be cared for in Utah. He apparently provided little economic assistance, even though he had few temporal cares himself and ordered custom-made suits and sat for portraits.”[80] He also engaged in drills in his diary to improve his spelling and penmanship instead of attempting to support his family. Interestingly, nearly the entire time period of his European mission is blank in Eliza’s diary. Did she remove statements about hardships in her copying of her journal? Or was she just too busy to write?

Eliza’s temporal situation was not always exceedingly bleak, however. On occasion, Eliza and her sister wives had funds to hire help, provided either by Amasa, by their own work, or by trading work for board and room. In 1854, Eliza twice hired a man to work for them.[81] In an 1855 letter, she wrote that her family decided not to do a garden, “but I have no fears but that we shall get along some way, and that is bad enough sometimes, we have had to pay a man in flour for cutting up the last of our wood, we thought we had rather eat less than to chop so much and the wood was so large that we could not cut it any how.”[82]

Providing for Herself and Her Family

Eliza yearned to have the health, strength, and opportunity to help provide for herself and her family, but she often felt weak. Eliza’s mother, Lydia Clisbee Partridge Huntington, who often lived with or near Eliza, wrote in 1855 as part of a letter to Amasa, “I believe your family here are willing to lighten the burden that rests on you as far as it can be done by industry and econemy but it seems impossible to live here without making some expence espesialy for so large a family Eliza has worked some this winter for brother Colister he has paid for our milling which was nine dollars.”[83] Sometimes the sister wives bartered one service for another. For example, Caroline noted that “Eliza sewed for Thomas Callister to pay him for ploughing.”[84]

At other times, Eliza, her sister wives, and their children worked for pay. In 1856 she wrote, “During the last eighteen months we have done weaving to the amount of 102 dollars, besides a great amount of other work, such as sewing and spinning, coloring, housework, tending garden, and almost every kind of work that a woman was ever known to do.”[85] In 1868, while living in Fillmore, she wrote, “I commenced teaching school in the State House, had about 60 scholars.”[86] After her son Platte had been called to preside in Oak Creek in 1871, leaving her “without a provider” again, she started working in the Fillmore store, where her brother, Edward Partridge Jr., either still was or had recently been the manager.[87] In 1874, she taught school again for three terms.[88] In 1883 she wrote again of working in a store, noting, “Received 25 dollars in goods for my services in the store.”[89] Even had she not been separated from Amasa and then widowed by this time, Eliza’s participation in the cash economy mirrored that of other plural wives in the 1870s and 1880s. She increasingly turned to labor outside of the home, in addition to completing the usual gendered division of work at home.[90]

Eliza wasn’t the only one who taught school. Like Eliza, other wives of Amasa also worked for pay at times. One of Amasa’s wives, Paulina, wrote in 1855, “I am now living at Uncle Ezra’s and helping . . . teach school we had one hundred and twentythree scholars today I attend to the small ones it is pretty hard work more experience will make it lighter <I think> I left home with Bro. Rich’s council as their was no other chance for me to earn any thing this winter.”[91] Other plural wives also turned to traditionally feminine occupations such as teaching school.[92] Embry noted that of the plural wives she studied, “20 percent worked outside of the home at some point during their married lives, but none did so continually. They worked when necessary at very conventional jobs—teaching, housekeeping, midwifery, and clerking—and returned to their traditional roles as soon as possible.”[93] While some worked outside the home, all economized to help provisions and supplies last longer. Nearly half used “their home skills, sold farm goods, took in boarders or washed clothes to earn extra money.” An additional “Thirty-two percent did not work outside of the home for wages, but helped support their families by frugally budgeting the goods their husbands provided.”[94] Lydia, Eliza’s youngest sister, who married Amasa several years after Eliza and Caroline and who was surely well aware of their financial situations, wrote to her new husband within a year of their marriage, “I should be far happyer if I knew of any way that I could lighten your cares but do not know of any better than to be as careful and saving of what I have <as possible> and do nothing that I know will displease you.”[95]

Part of Eliza’s yearning for economic stability included the ability to focus on more than just the basic necessities of life. In one letter from the early 1850s, she noted that her family had been low on food. “I do not feel at all discouraged, but I certainly see no way to get bread,” she stated. She had earlier written about the lack of wheat because of problems last year with grasshoppers, possibly flooding, and then neglect this year because the men were fighting the Indians. She also did not know how she would obtain “vegetables to live on this winter, but I make no doubt but we shall live a good while, yet, if we do not die till we are starved to death, for I think I have proved that, that was<is> not easy to do.”[96] In an 1855 letter, she wrote, “With all that we can do it is impossible to keep ourselves in what seems to be the necessaries of life, although we could not starve if we had nothing but bread or meat, but it is very convenient to have other things.”[97]

Sharing with Others

Ideally, however, Eliza’s family would have enough of the necessities of life—food, fuel, clothing—that she could also share with others. It is hard to tell from what scarcity or abundance she gave, because she often wrote about not having enough food or not knowing where their food or fuel would come from, but she did not always assess her economic situation when life was more comfortable. However, hints indicate that she had enough to eat and to care for her family at least some of the time and that economic prosperity is partly a matter of perspective. Although in September 1854 Caroline wrote in a letter to Amasa, “We get along as well as we can, though that is not saying much,” three months earlier in June 1854, Eliza wrote “I made a small gift to the Society for the Lamanites. Only 5 yds factory cloth, but I hope to be able to give more soon.”[98] Latter-day Saint women in Utah Territory had recently formed the Indian Relief Society to sew clothing for Southern Paiute women and children.[99] Though she had enough to give some to the Indian Relief Society, it did not come easily. Eliza continued, “I have employed myself so far this spring and summer with very hard work, such as working in the garden, doing house work washing, ironing, spinning, taking care of children, and in attending to the education of my little boy myself at present sewing [etc.] when I can get the chance and have no time to idle way.”[100] As Daynes notes, “Few Utah women . . . could afford not to work” even in the unpaid economy of the home. Work was a necessity on the frontier for all women—polygamous or otherwise.[101] Two decades later, in March 1877, she wrote, “Went to meeting. There was a call for donations towards building a temple in Sanpete [i.e., Manti]. I gave five dollars in money. Mother gave some buckskin gloves, several pair.”[102] She also donated to the Relief Society on multiple occasions.[103]

Yearning for a Stable Home

Perhaps the most prominent theme of yearning in Eliza’s writings was for a stable and comfortable home where she could live permanently with enough room to care for her family. Eliza often wrote about moving, staying with one family member or another, or living in a tent, seemingly without a significant sense of stability. Upon arriving in Utah in 1848, Amasa and three of his wives lived in “a small single-room cabin with a leaky roof.” Perhaps the poor living situation contributed to Amasa’s quick acceptance of a call to go to California.[104] In his absence, his wives survived through the assistance of neighbors.[105]

The spring after her arrival in Utah, just four days after the tent in which she was living burned down, Eliza noted that she was now living in a wagon, but there was “snow blowing furiously. We were so very uncomfortable, although we had a stove in the wagon, that we thought best to go to the Fort to Mother’s. We did so and found her worse off than we were, for the rain was running through the roof, and everything in the house was wet, and the ground perfectly muddy under her feet. We thought it would never do for her to live that way, so we took her and her effects to the wagons, deeming it more prudent to live out of doors than in such a house as this.”[106] Subsequent homes in Utah proved equally troubling.

At times Eliza was able to settle in one place for a period of years; however, in the spring of 1864, she wrote, “I moved up farther into the town, and occupied a room in Br. Lewis Brunson’s house. In the fall I moved into an unfinished brick house of Br. Lyman’s, where I lived for several years.”[107] It is interesting that in her journal, she always separated what belonged to Amasa and what belonged to her. Perhaps because she was only one of his wives, she recognized that what was his was not necessarily hers. It is an interesting contrast to the letters and diaries of women on the home front during the Revolutionary War and the Civil War who began to assume more ownership for the farms or businesses that their husbands left behind. As author Alan Taylor wrote, “With so many men away fighting, wives and daughters had to run family farms and shops, or the economy would collapse. . . . Many letters showed a growing confidence by women who had referred to the farm or shop as ‘his’ but later began to call it ‘ours’ or even ‘my farm’ in letters to distant husbands.”[108] Embry similarly noted that since “plural wives had more responsibility for outside work because their husbands divided their time between several households . . . more polygamous children than monogamous children described the garden as ‘my mother’s’ rather than ‘my father’s.’”[109]

Eliza often lived in other people’s homes, either renting rooms or living with other family members. While she usually seems to have enjoyed the company, she also craved more stability. The lack of her own home subjected her to other people’s decisions regarding housing. In 1879 she wrote, “We shall stay at Br. A. Roper’s till my boys, Platte and Joseph start for San Juan, when I expect to occupy my son Platte’s house during the winter, or until some of the boys come back.” Some days later she updated her situation, “Platte has sold his house and lot to George Lovell, but I have the privilege of living there, and having the fruit off of two rows of trees, and a part of the lucern until Platte comes back, which we expect will be sometime in the summer of 1880.”[110] Perhaps she felt that if she owned her own land, she would not have to move according to others’ schedules.

In the 1870 letter with which this paper began, Eliza mentioned that Amasa owned property. Millard County deed records from spring 1871 shed light upon this aspect of his economic situation. On 20 May 1871, Amasa deeded plots of land to the three Partridge sisters whom he had married over two decades earlier: Eliza, Caroline, and Lydia. Each of the land records notes that the lots were about an acre in size. Amasa did not charge them for the land but gave it to them as “good will.”[111] In his diary, he noted, “I exicuted some transfers of landed property, to my wives Eliza, Caroline, and Lydia whose peculiar views religious would not allow them to continue to live with me.”[112] Amasa’s comment refers to the fact that several of his wives, the Partridge sisters among them, distanced themselves from him following his departure from the Church. In an interesting side note, perhaps illustrative of the responsibility that Eliza felt, Amasa often mentioned Eliza first when he spoke of the sisters, although he married Caroline shortly before Eliza. Eliza was the oldest in her family, and it is possible that she felt responsible for her sisters, seven and ten years younger than herself, even into adulthood.

While this paper’s scope does not include following the complete trail of Eliza’s land in Fillmore, later in life she sought to purchase other land. It is thus possible that she eventually sold the land deeded to her by Amasa to provide for herself. Alternatively, she moved back and forth more than once between Fillmore and Oak Creek (or Oak City) in central Utah, so she may have rented her home in Fillmore when she eventually settled in Oak Creek to be closer to family.[113] By the 1880s Eliza had also spent time living near her sons Platte and Joseph and their families in San Juan County in southern Utah. She returned to central Utah in August 1884 and stayed with her sister Caroline in Oak Creek. Nine months later, she was still in her sister Caroline’s house. A few months after that, she moved to her nephew Edward Leo Lyman’s home for the winter.[114]

Years earlier, in one letter in 1854, after referring to her sister Emily, who was married to Brigham, Caroline mentioned offhand that “[brother] Brigham is building another large house for the rest of his family.”[115] While perhaps she intended nothing more than to pass along information of interest, one cannot help but juxtapose the financial situation of Brigham’s wives with Amasa’s wives. Embry and Daynes prove correct yet again: the state of a plural wife varied widely from one situation to another, and examination of individual-level data provides snapshots that can be compiled into a collage that gives a broader picture of plural marriage in nineteenth-century Utah. Studying the life of Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman, with reference to Amasa’s other wives and children, provides one such individual portrait of the economic situation of plural marriage households.

Conclusion

Throughout her life, Eliza’s yearnings for an external provider, assistance from family and friends, the ability to provide for herself and her family, the attainment of enough to share with others, and a stable home were sometimes realized, though often not. Although plural marriage often helped economically marginalized women raise their status through marriages to financially well-off men, in Eliza’s case, she moved from childhood in a financially stable home to economic uncertainties following her father’s death and her transition into plural marriage. While she often received temporal support from Amasa, her economic situation also affected her ability to raise and care for her children, as she had to leave them at times to teach school or work in a store.

Daynes wrote, “The men who became polygamists, of course, needed attributes that could fulfill the religious and economic needs of those marrying as plural wives.” While Amasa struggled to provide financially, he was an apostle for nearly the entirety of his time as a husband of plural wives, which was appealing to many women at that time. It is interesting to note that Lydia did not marry Amasa until 1853 when she was nearly twenty-three years old, almost a decade after her sisters married him. While Amasa had already contributed to her support (such as in the 1849 division of goods mentioned earlier), and Lydia was surely aware of his inability to provide at other times, Daynes notes that “many Latter-day Saints in the nineteenth century believed they should be married for eternity, or sealed, during their lifetimes if they hoped to be exalted.”[116] The Partridge sisters were also typical of other plural-marriage patterns in that other polygamous men often married relatives of their wives, usually their wives’ sisters, but occasionally their wives’ nieces or others.[117]

Daynes further explained, “For the most part, polygamists were wealthier than other men, and those with a higher church rank were more likely to have plural wives. Wealthier men could more easily provide for additional wives . . . and those of higher church rank were considered more likely to attain exaltation in the next life and thus provide women with the eternal spouses they needed for their own exaltation.”[118] It is interesting to note that despite economic hardships, apparently none of the Partridge sisters left him while he was an active Church member, despite the ease of divorce. Were their financial hardships not as consistently unfortunate as it seemed? Or were their longings for and expectation of a reward in the next life more important than temporal earthly hardships? Either way, the sisters’ lives following the separation from Amasa continued, again supported at times by Amasa, but in large part through their own efforts, the help of their children and other family members and friends, as well as the Church.

Fifteen years after the letter with which this article opened, and perhaps fittingly indicative of her desire to settle permanently on her own land, the final journal entry Eliza recorded, in December 1885, just over two months before she passed away at the age of 65, read, “Dec. 23rd Bought some land . . . to build on.”[119]

Notes

[1] Eliza M. Lyman and Caroline E. Lyman to Amasa M. Lyman, 31 July 1870, Amasa M. Lyman Collection, 1832–1877, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[2] Edward Leo Lyman, Amasa Mason Lyman, Mormon Apostle and Apostate: A Study in Dedication (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2009), 496–97.

[3] Lyman, Amasa Mason Lyman, 426–29.

[4] See, for example, Ronald Walker, Wayward Saints: The Godbeites and Brigham Young (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 347; and Amasa M. Lyman and Scott H. Partridge, ed., Thirteenth Apostle: The Diaries of Amasa M. Lyman, 1832–1877 (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2016), 557–58. In addition, in November 1873 Amasa noted in his diary that he saw Lydia Partridge Lyman and “her” daughter Ida for the first time in several years. Ida would have been fourteen years old at that time. 24 November 1873 diary entry, in Lyman and Partridge, Thirteenth Apostle, 791.

[5] See Kathryn M. Daynes, More Wives Than One: Transformation of the Mormon Marriage System, 1840–1910 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001), 156–59; Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835–1870 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017), 280–81.

[6] Lyman, Amasa Mason Lyman, x.

[7] See, for example, “Plural Marriage and Families in Early Utah,” https://

[8] Jessie L. Embry, Mormon Polygamous Families: Life in the Principle (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987), xvi.

[9] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 3.

[10] Eliza and Caroline were only two of the eight wives with whom Apostle Amasa had lived for decades as a plural husband. Amasa Lyman had married at least three other women in Nauvoo who had all separated from him soon thereafter and eventually divorced him. See Lyman, Study in Dedication, 110.

[11] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 11.

[12] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 9.

[13] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 12–13, 133.

[14] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 116.

[15] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 156–59.

[16] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 77.

[17] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 83–84.

[18] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 134–35.

[19] Eliza M. Lyman and Caroline E. Lyman to Amasa M. Lyman, 31 July 1870.

[20] As a hatter, his business did not require land other than a lot for a factory, store, and house. His additional lands may have been used to grow a few crops for his family, or they may have been a means of consolidating his wealth.

[21] Emily Dow Partridge Young, “Reminiscences of Emily Dow Partridge Young.” 7 April 1884, typescript, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[22] Edward Partridge to Lydia Partridge, 5–6 August 1831, Church History Library.

[23] Edward Partridge, Affidavit, 15 May 1839, Edward Partridge Papers, Church History Library.

[24] Sherilyn Farnes, “Fact, Fiction and Family Tradition: The Life of Edward Partridge (1793–1840), The First Bishop of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2009), 1–2, 49–52.

[25] Emily D. P. Young, “Autobiography,” Woman’s Exponent, 15 February 1885, 138.

[26] Edward Partridge, Affidavit, 15 May 1839, Edward Partridge Papers; Clark V. Johnson and Ronald E. Romig, An Index to Early Caldwell County, Missouri Land Records (Independence, MO: Missouri Mormon Frontier Foundation, 2002), iv, 141.

[27] Edward Partridge to Emily Partridge Dow, 12 October 1837, photostat in possession of State Historical Society of Missouri. The note to Partridge’s younger brother is attached to the letter to Emily Partridge Dow.

[28] Farnes, “Life of Edward Partridge,” 52–63.

[29] “Obituary,” Times and Seasons, June 1840, 127; Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman, Journal, 1846 February–1885 December, Church History Library, 12. The early pages of Eliza’s journal contain an autobiographical sketch with numbered pages.

[30] Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman, Journal, Church History Library, 13, 15; Lyman, Study in Dedication, 496–97.

[31] Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, ed. Scott H. Partridge (Provo, UT: Grandin Book, 2003), 17 October 1848.

[32] Lyman, Study in Dedication, 163, 188; Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 13 April 1849; 29 September 1850.

[33] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 11 March 1851; 3 June 1857. See also Lyman, Study in Dedication, 188–91, 245–46.

[34] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 18, 21, 25, 28 April; 7 May 1849. Eliza’s extant journal is actually a copy of her original journal. The location of her original journal is unknown, but she apparently copied dozens of pages into what she titled, “Life and Journal of E. M. P. L. S.” It is apparent that she edited as she went, since at times she would copy her earlier diary entry, and then make a comment only possible from the perspective of later years. For example, when her first grandson was born, she wrote about his birth and then poignantly included this line in past tense, “We always called him Alton,” since her grandson had died at the age of four and a half.

[35] Lyman, Study in Dedication, 167; Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 2 September 1849.

[36] Eliza M. Lyman and Caroline E. Lyman to Amasa M. Lyman, 31 July 1870.

[37] Eliza M. Lyman and Caroline E. Lyman to Amasa M. Lyman, 31 July 1870.

[38] 4 August 1870 diary entry, in Lyman and Partridge, Thirteenth Apostle, 621.

[39] Francis Marion Lyman to Amasa M. Lyman, 12 August 1870, Amasa M. Lyman Collection, 1832–1877, Church History Library.

[40] Lyman, Study in Dedication, 441.

[41] Francis Marion Lyman to Amasa M. Lyman, 29 December 1870, Amasa M. Lyman Collection, 1832–1877, Church History Library.

[42] Lyman, Study in Dedication, 495–99.

[43] See, for example, his inclusion of Lydia Clisbee Partridge Huntington in the distribution of goods sent from California. Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 3 October 1849.

[44] See, for example, Daynes, More Wives Than One, 71–72, in discussing the pressures on Church leaders, even down to stake presidents and bishops, to take on additional wives.

[45] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 128.

[46] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 130.

[47] See Daynes, More Wives Than One, 133, for general statements on wealth and time in Utah.

[48] Lyman and Partridge, Thirteenth Apostle, xii.

[49] Lyman and Partridge, Thirteenth Apostle, xv.

[50] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 1860 [no month or day listed].

[51] Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman to Amasa Mason Lyman, 29 June 1854, Church History Library.

[52] Lyman, Study in Dedication, 165–66.

[53] Caroline E. Lyman to Amasa M. Lyman, 28 April 1855, Church History Library.

[54] Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman to Amasa Mason Lyman and others, 29 August 1853, Church History Library.

[55] Embry, Mormon Polygamous Families, 123–27.

[56] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 3 October 1849.

[57] See Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 48n178. Family references to “Uncle David” or “Uncle Frederick” also seem to support this fact. See, for example, Albert R. Lyman, Biography [of] Francis Marion Lyman, 1840–1916: Apostle 1880–1916 (Delta, UT: edited, printed, and published by Melvin A. Lyman, 1958), 7. Albert Lyman provides an uncited quotation from Francis Marion Lyman that “Uncle David Frederic was our teamster.” For references to the practice of the adoption of biologically unrelated adult Church members to one another, see Jonathan Stapley, The Power of Godliness: Mormon Liturgy and Cosmology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 20, 39.

[58] Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman to Amasa Mason Lyman and others, 29 August 1853, Church History Library.

[59] Albert R. Lyman, Biography [of] Francis Marion Lyman, 6–7; Lyman, Study in Dedication, 222.

[60] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, July 1863.

[61] Embry, Mormon Polygamous Families, 94–95.

[62] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 6, 8, 11 June 1849.

[63] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 7 April 1854.

[64] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, December 1879.

[65] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 5.

[66] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 24 May 1868.

[67] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 15 August 1876; Joseph A. Lyman, Journal, 4 August–29 September 1876, Church History Library.

[68] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 5 May 1883.

[69] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 22 November 1882; 18 January 1883; 28 April 1883; 5 May 1883.

[70] Amasa Mason Lyman to Paulina Lyman, 16 December 1870, Church History Library.

[71] Lyman, Study in Dedication, 135.

[72] Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman to Amasa Mason Lyman and others, 29 August 1853, Church History Library.

[73] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 26 December 1879.

[74] Lyman, Study in Dedication, 347–49, 352, 354.

[75] Reid L. Neilson, “Mormon Mission Work,” in The Oxford Handbook of Mormonism, ed. Terryl Givens and Philip L. Barlow (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 190.

[76] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 26 August 1860.

[77] Lyman, Study in Dedication, 499.

[78] See, for example, Brigham Young to Thomas Callister, 12 July 1873, Church History Library.

[79] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, May 1883.

[80] Lyman and Partridge, Thirteenth Apostle, xviii.

[81] Caroline E. Lyman to Amasa Mason Lyman, 14 September 1854, Church History Library; Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman to Amasa Mason Lyman, 29 June 1854, Church History Library.

[82] Lydia P. Lyman and Eliza P. Lyman to Amasa Mason Lyman, 1 March 1855, Church History Library.

[83] Eliza Maria Lyman, Caroline E. Lyman, and Lydia Huntington to Amasa Mason Lyman, 30–31 January 1855, Church History Library.

[84] Caroline E. Lyman to Amasa Mason Lyman, 28 April 1855, Church History Library.

[85] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 19 February 1856.

[86] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 7 December 1868.

[87] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, spring 1871 [no month or day]; Esshom, Frank, Pioneers and Prominent Men of Utah: Comprising Photographs, Genealogies, Biographies (Salt Lake City: Utah Pioneers Book, 1913), 1090; Platte D. Lyman Journal, 20 February 1871, Church History Library.

[88] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 1874 [no month or day].

[89] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 14 May 1883.

[90] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 134–35.

[91] Paulina E. Lyman to Amasa M. Lyman, 24 January 1855, Church History Library.

[92] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 134.

[93] Embry, Mormon Polygamous Families, 95–96.

[94] Embry, Mormon Polygamous Families, 96. Surely these areas also overlapped.

[95] Lydia Partridge Lyman to Amasa M. Lyman, 11 December [1853], Church History Library.

[96] Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman to Amasa Mason Lyman and others, 29 August 1853, Church History Library.

[97] Lydia P. Lyman and Eliza P. Lyman to Amasa Mason Lyman, 1 March 1855, Church History Library.

[98] Caroline E. Lyman to Amasa M. Lyman, 14 September 1854; Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 9 June 1854.

[99] Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835–1870 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017), 288, 301–4.

[100] Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman, Journal, 9 June 1854, Church History Library.

[101] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 134–35.

[102] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 18 March 1877.

[103] See, for example, Oak City Ward, Delta Utah Stake, Relief Society Minutes, 1874–1965, Volume 1, 4, 8.

[104] Lyman, Study in Dedication, 168.

[105] Lyman and Partridge, Thirteenth Apostle, xiv.

[106] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 23 May 1849.

[107] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, [spring] 1864.

[108] Alan Taylor, American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750–1804 (New York: W. W. Norton, 2017), 200.

[109] Embry, Mormon Polygamous Families, 97–98.

[110] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 12, 20 October 1879.

[111] Millard County Deeds, vol. C, 81–83, microfilm at Family History Library.

[112] 20 May 1871 diary entry, in Lyman and Partridge, Thirteenth Apostle, 656–57. Unless he neglected to note that they were his former wives, Amasa apparently still considered Eliza, Caroline, and Lydia his wives in May 1871.

[113] In 1877 she wrote, “Lucy and I moved the furniture, etc. out of the west end of our house so as to rent it.” Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 17 April 1877.

[114] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 15 August 1884; 15 June 1885; 27 October 1885.

[115] Caroline E. Lyman to Amasa M. Lyman, 14 September 1854, Church History Library.

[116] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 4.

[117] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 70.

[118] Daynes, More Wives Than One, 128.

[119] Lyman, Eliza Maria Partridge Journal, 23 December 1885.