Striving for Cooperation and Economic Improvement

The Straw-Braiding Home Industry

Patricia Lemmon Spilsbury

Patricia Lemmon Spilsbury, "Striving for Cooperation and Economic Improvement: The Straw-Braiding Home Industry," in Business and Religion: The Intersection of Faith and Finance, ed. Matthew G. Godfrey and Michael Hubbard MacKay (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 93–112.

A commitment to faith, obedience, and industry have long been associated tenets of Christianity. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints foresaw the significance of unity and cooperation in conjunction with those qualities, recognizing their potential impact on the lives of the Saints as they worked together to build self-sufficient communities. Women took on expanded economic roles during the early years of the Church as husbands and fathers were called on missions throughout the country and the world, increasing women’s significant economic contributions to family and to local communities. The braiding of palm leaf and straw was a valuable skill used to support families as well as to aid in building new Zion communities in the western United States.

Palm-leaf and straw braiding were significant home industries for women in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries that allowed them to work at home with their children, maintain their household responsibilities, and contribute to the family economy. In an article written by William Makepeace Thackeray that appeared in the March 1850 issue of Punch, he reports visiting the “working people” of Essex and described Castle Hedingham and the surrounding area as a location where “an enormous amount of straw plaiting is carried on.” He described the low rate of pay for adult women and their children engaged in plaiting straw, as well as the “wretchedly low” pay of agricultural workers, stating that “were it not for the straw plait, the people would generally be in a far worse condition then they are at present.”[1]

Palm-leaf and straw braiding were ancient crafts found in Egypt as early as the New Kingdom, 1200 BC.[2] In more modern times, the practice of straw braiding, or plaiting, came out of Italy. Straw hats were popular in France by the late 1600s, and by 1760, they were introduced into England.[3]

Examples of the hats manufactured in Italy were referred to as “Leghorn” hats, made of the slender straws from bearded wheat, grown specifically for that purpose. The leghorn hat had a basic wide brim with a skull cap.[4]

Though the materials changed over time—from imported palm leaves to different varieties of straw—the tools used to prepare them for braiding did not demand a large financial investment, such as the purchase of a loom for weaving. Moreover, the techniques used to prepare and braid the straw were not difficult to learn. Mothers included their children in both the preparation and braiding of the straw, making it truly a “home industry.”[5]

“New England Bonnet Makers,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, October 1864.

“New England Bonnet Makers,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, October 1864.

An article that appeared in the October 1864 issue of Harper’s Magazine described the evolution of the straw hat. “Many a chase after a blown-away hat induced the ladies to put their wits to work in order that they might put an end to the vexations which were caused them by their broad and flapping hat-brims.” The result was the Dunstable bonnet made from finer straw cut into thinner widths. This bonnet style was very popular, encouraging the manufacture of the hats at home.[6] Hat design continued to evolve as families emigrated to America, where straw hat manufacture centered initially in New England, specifically in Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

By the early eighteenth century, the work environment of women shifted, in part due to the market economy. Social historian Thomas Dublin, in his book Transforming Women’s Work, stated that the effects of the Industrial Revolution extended far beyond “power-driven machinery” and cotton; the revolution also influenced the growth of outwork occupations[7] in farming communities and “transformed the rural labor market.”[8] Material culture specialist Laurel Thatcher Ulrich describes straw and palm-leaf braiding for hats and bonnets as “a classic form of outwork.” Going beyond purely domestic use, straw braiding provided a ready means of making additional income for the family, usually during the winter and early spring months, when less farm work was required and more discretionary time was available.[9] Outwork also included such occupations as sewing and weaving.

In the early twenty-first century, we may not recognize the critical role such skills played in the lives of our early mothers. Home industry supported the strong work ethic of women, allowing mothers to remain in the home nurturing children, feeding and milking the family cow, making butter and cheese, tending the family garden, and sewing clothing for the family, while also contributing their skills to the family’s financial well-being. Straw braiding was a valuable option for domestic women.[10]

As the early Saints joined the Church, they were encouraged through revelation to gather together “unto one place upon the face of this land” (Doctrine and Covenants 29:7–8). Joseph Smith taught that such gathering would allow the Saints to build a temple in which the Lord would reveal his ordinances, a prerequisite for the establishment of Zion. Also, such gathering would provide a refuge—a place of protection and spiritual instruction for the people.[11] As the years passed, the site moved from Kirtland, Ohio, to Jackson County, Missouri, to Nauvoo, Illinois, and finally, to the Salt Lake Valley.

The skills early members of the Church brought with them as they joined the Church were critical to the success of their community. Women’s individual stories have a common thread: they used those acquired skills—the same skills they used to meet the daily challenges of providing for themselves and their families—to assist in building the kingdom. For many, those were the only means they had to raise the funds to finance this gathering.

The story of John and Emma Grace Austin illustrates the economic challenge of gathering and the impact of the domestic skill of straw braiding. The Austin family lived in Studham, Bedfordshire, England, where Emma was converted to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1848, and her husband, John, two years later. British Latter-day Saints were encouraged to gather with the Saints in America, and the Austins wanted to emigrate. However, finding the means to do so seemed impossible; it took all their combined efforts to meet the survival needs of their large family. Raising funds for their passage and subsequent travel to the main body of the Saints seemed hopeless, but Emma was determined. She quietly began to put away what scant moneys she could.

One day in 1854 a peddler came to the Austin’s door selling bundles of straw for braiding. Being a good salesman, he encouraged her to purchase several extra bundles and then sell them to her neighbors, offering her a one-cent commission for each bundle she sold. Emma was successful in this initial effort and the next time purchased additional bundles. Her daughters joined with her, braiding the straw and making hats. Over time, Emma built up her own business and established a small store. By 1866, twelve years later, the family had saved enough to send the two eldest children, Harriet and George, to Zion.

Within two years, John felt a strong desire for the whole family to emigrate—no small undertaking with nine children. Through the kindness of a neighbor and good friend who also wanted to emigrate, they borrowed the remaining funds needed and left in June 1868. They settled in Lehi, where Harriet and George were living. John continued farming, and Emma continued her straw-braiding business.[12]

Elizabeth George also demonstrated her obedience and strong commitment in spite of the economic challenges she faced in emigration. Once again, her skill with straw enabled her to gather with the Saints. She was born in Mursley, Buckinghamshire, England, where she married Thomas Labrum in 1837. They met Latter-day Saint missionaries, and Elizabeth was baptized in 1849. Her oldest daughter joined the Church two years later, but her husband chose not to be baptized. Elizabeth’s family disowned her as a result of her decision. Together, Elizabeth and Thomas decided Thomas would go ahead of the family to America to make a new home, and they would follow. During the voyage to New Orleans, Thomas listened again to the missionaries and was baptized. Upon arriving in St. Louis, he contracted cholera and died. Prior to his death, he left his belongings and money with a friend, who promised to take them to Utah and keep them for his family, which he did.

Elizabeth did not learn of Thomas’s death for six months. In England, she and her seven children moved to the “poor farm” for a time and then to Billington, Bedfordshire, where she braided straw hats. In 1853 she started a millinery business and, with her children, made hats and sold them door to door. By mid-1862 she had saved enough to take her four youngest children and a grandson to America. Her three oldest children emigrated the following year. The family settled in Salt Lake City, where they continued to work together to make and sell straw hats. Elizabeth was active in the South Cottonwood Ward’s millinery efforts.[13]

The economic solution that allowed these two British families to gather with the Saints in America centered on straw—selling bundles of straw to others, working it in their own homes, then selling the braided straw hats. The process of preparing the straw—gathering, soaking, bleaching, drying, and splitting it—could be accomplished using materials readily available, with the only expenditure perhaps being an instrument to split the straw, which initially could be done with a single nail.

Gathering to Zion in the American West, beginning a new life, and forging new settlements required a diversity of talents, abilities, and skills of all members of the community—men, women and children. Once they had gathered, the tasks of finding shelter, food, and a means to support the family were paramount. High mortality rates and mission calls heavily impacted the responsibilities of women not only in caring for their family and contributing to community needs, but, additionally, in taking on the full responsibility of providing economically for the family. According to historian Carol Cornwall Madsen: “The traditional household division of labor dissolved under the tremendous economic challenges and high mortality of Nauvoo. Women became instant providers when sickness and death struck down the traditional breadwinners. Historically, they turned to their domestic skills to support themselves and their families.”[14]

Recognizing the increase of responsibility that fell to them, women established manufacturing industries within their homes. They were well equipped to do so. Spinning, weaving, sewing, basketry, and straw braiding were skills early members, women and men, brought with them as they gathered to Zion. Willard Richards sent a letter to his sister, Hepzibah, who was living in Hamilton, New York, in early 1837, inviting her to gather with the Saints in Kirtland. “Here you may labor and receive your reward; . . . straw bonnets worth 2.50 in Richmond—4.00 in Greenfield would be worth from 5.00 to 6.00 in Kirtland. . . . [There is] no straw milliner here [and] one is much wanted. . . . If you come out soon I know of no reason why you may not before long have as much of the best work in silk circassion crepe & straw as you can find hands to do, both in bonnet & dressmaking.”[15]

Among those who gathered to Zion with straw-manufacturing skills was future General Relief Society President Eliza R. Snow, who learned straw braiding as a young girl, winning first prize for her leghorn hats two years in a row at the county fair.[16] Rhoda Richards, another sister of Willard Richards, related that as a girl she learned to knit stockings for her family, make her own clothes, braid and sew straw hats and bonnets, and learned to card, spin, and weave.[17] Lucy Meserve Smith also learned palm-leaf and straw braiding to make hats.[18] Hannah Brandham Williams was raised in a straw-braiding family in Eaton Bay, Bedfordshire, England. Before her mother died, she taught Hannah to braid straw and sew hats. Her skills helped Hannah emigrate with her aunt’s family. They settled in Kaysville, where she continued braiding straw to support her own family.[19] Elizabeth Haven Barlow was young when she learned to braid straw hats, pinlaces, and other delicate trimmings to provide for herself after the death of her mother—skills that also helped pay for her education. She graduated from Amherst College as a teacher in 1816. Her cousins Willard Richards and Brigham Young introduced her to the Church in 1837.[20] Straw-manufacturing experience enabled these women not only to contribute to the economic security of their family and their community but also to grant them some economic independence.

Recognizing the economic potential of straw and palm-leaf braiding, in January 1845, Bishop Newel K. Whitney called on ward bishops in Nauvoo to “establish the manufacturing of palm leaf and straw hats, willow baskets and other business that children are capable of learning, that they may be raised to industrious habits.”[21] Hosea Stout attended a meeting in March of that year, in the Evans Branch, about four miles south of Nauvoo, “for the purpose of organizing the Sisters in Associations according to their several occupations for the purpose of promoting the cause of home industry.”[22] By April, Nancy Rockwood was chosen president of the Straw Association in Nauvoo, which had organized a “straw manufactory” to “carry into operation the manufacturing of straw bonnets and hats, and to promote the objects of industry, and economy.”[23] Sarah Southworth Burbank learned to braid straw hats in a boarding school in Nauvoo, and after her marriage she supplemented the family income by making and selling them for a dollar each to passengers on the steamships that came in and out of Nauvoo.[24] Zina Jacobs learned to braid palm-leaf hats at her mother’s home in Nauvoo in 1845. She tells of making a hat for her husband, Henry, and refers several times to working on hats before she left Nauvoo.[25]

As the Saints traveled west to the Salt Lake Valley, their concerns and struggles did not change, though their environment did. Primarily they were still concerned with finding shelter, food, and means to support their families, as well as wrestling with the desert environment in the valley. Very soon, families were sent throughout the territory to build settlements, and men were called to fill missions in far-flung areas of the world. The full responsibility of providing for families fell to wives, mothers, daughters, young sons, and their small tight-knit communities. Home industry skills were critical.

Though the Female Relief Society had been disbanded in Nauvoo in the mid-1840s, once the Saints had settled in the Salt Lake Valley, the sisters began gathering together across ecclesiastical boundaries to coordinate efforts to assist those in need. However, the disruption caused by the Utah War took years to overcome. Once the Civil War ended, Church leadership focused efforts on strengthening membership and on organizing institutions that would encourage economic self-sufficiency as well as training the youth of the Church. In 1866 Brigham Young recognized the need to organize the women of the Church. He stated, “If we could get up Female relief Societies and they would use their influence to get the Sisters to make their own bonnets and make and wear their own Home made clothing it would do much good.”[26] The following year he urged bishops to move forward to organize relief societies under the direction of Eliza R. Snow.

As the completion of the transcontinental railroad approached, calls for retrenchment were issued, placing greater emphasis on home manufacture and industry to prevent dependence on outside sources. At April conference in 1868, held in the newly completed Tabernacle, Brigham Young asked “the Bishops to sow a little rye, to make straw for hats and bonnets . . . that the sisters of their wards may have straw to manufacture. . . . Gather the straw, and make your bonnets and hats, and wear them when you come to this tabernacle; and make hats for your husbands and sons to wear, and for your brothers and your sisters, your daughters and your mothers, and let us see all the sisters and all our brethren and all our children wearing hats and bonnets of material produced and manufactured by ourselves.”[27] He specifically called on the women to organize: “Now, ladies, go to and organize yourselves into industrial societies, and get your husbands to produce you some straw, and commence bonnet and hat making.”[28]

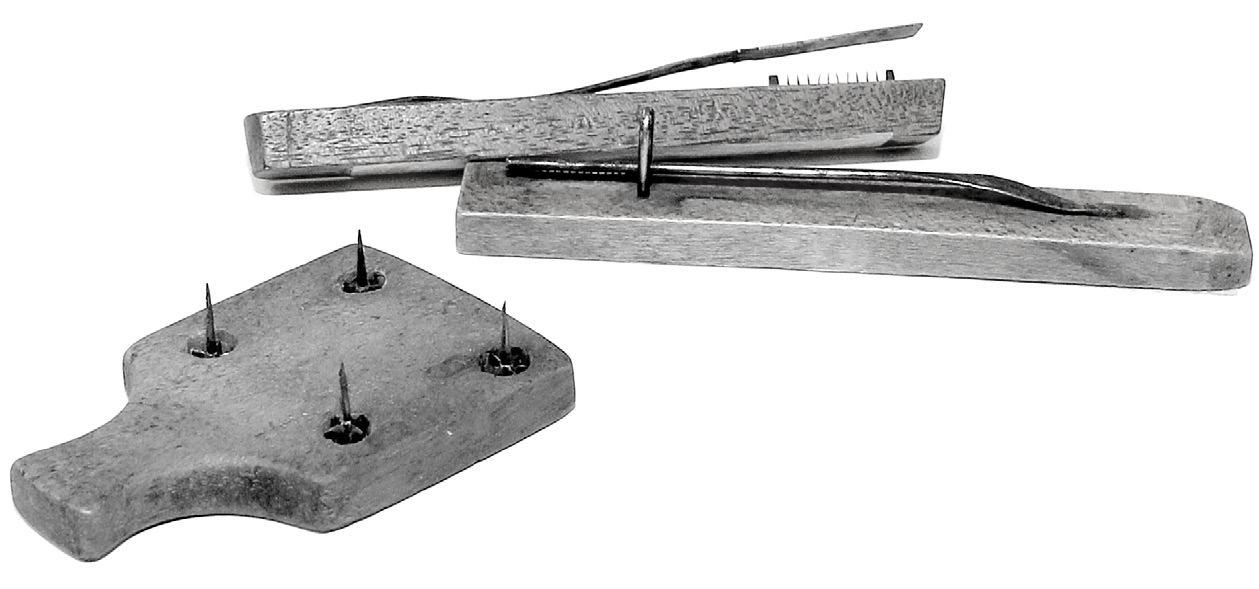

Many Relief Societies responded to his call. From Ogden to St. George, Relief Societies began establishing “straw braiding departments,” such as in the Salt Lake City 16th Ward. Patty Sessions felt straw braiding was an important skill for young women. Her remarks to that effect were recorded in her ward Relief Society minutes on 15 July 1868: “It would be a blessing for the rising generation of girls to learn the straw manufacture.”[29] Her Relief Society president, Olive Walker, concurred. On 25 November, “it was motioned & seconded that Mrs. P Sessions be apointed to preside over the Straw Braiding Department to meet at her house at one o’clock on Fast days.”[30] Patty spent the next few days gathering the materials needed for the school, in particular a “straw spliter.” An experienced straw braider, she could not find one that was to her liking. She designed one herself and engaged a man to make ten of them for her, demonstrating the creativity and innovation of women and their organizations to accomplish their charge.[31] In addition to the splitter, Patty would have needed a large tub for steaming the straw and a roller or flattener.

Martha Webb Campkin Young brought a straw roller with her from England aboard the ship Caravan and across the plains with the Willie Handcart Company. Her daughter, Martha Ann Campkin Merrell, told how her mother made straw hats for their family and for sale:

We used to gather straws, break them at the joints and tie them in bundles. Mother would work the straws over night, roll them and split them in different sizes. . . . Would dip them in warm water[,] put two together smooth side out and braid. “Under one and over two, that's the braiders do.” Before and after braiding she would whiten the straw with sulfur by placing a dish of sulfur in a tub then place braid or hats around the dish, cover [the] tub and leave [it] over night or longer, if necessary. [She] made them for her own family and also for sale.[32]

Patty Sessions was not alone in her commitment to straw braiding and its importance in the community. Soon after her arrival in Lehi in 1866, Harriet Austin Jacobs, daughter of John and Emma Grace Austin spoken of earlier, opened a millinery shop that remained in business for more than thirty years. She hired several women to assist her, including Harriet Webb, Sarah Gurney, Ann James, and Elizabeth Cutler. Her mother joined them upon her arrival in 1868. They used straw grown in Lehi, which they selected, cut, split, and braided by hand. She frequently advertised in the Lehi Banner and other newspapers. Interestingly, in July 1868, Brigham Young visited Lehi. He was so impressed by the women’s hats that he ordered twelve from Harriet Jacobs at four dollars each.[33]

Straw splitters. Top: Straw would be drawn across the teeth embedded at the end of the instrument. Used in the Brigham City hat factory; donated to the DUP by Fannie Grashis. Bottom (very small): Each straw would be poked down and pulled through the hole, splitting it into 4, 5, 6, or 7 strands. Donated to the DUP by Zina Young Card; an heirloom of the Huntington family, brought to the Salt Lake Valley in 1847. Courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers Picture Collection.

Straw splitters. Top: Straw would be drawn across the teeth embedded at the end of the instrument. Used in the Brigham City hat factory; donated to the DUP by Fannie Grashis. Bottom (very small): Each straw would be poked down and pulled through the hole, splitting it into 4, 5, 6, or 7 strands. Donated to the DUP by Zina Young Card; an heirloom of the Huntington family, brought to the Salt Lake Valley in 1847. Courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers Picture Collection.

David and Mary Ann Sharratt Rollins emigrated in 1853, settling in Ogden. David raised a more pliable type of straw, and they worked it together. David braided it, and Mary Ann sewed the hats, which were sold to local residents as well as to immigrants passing through on their way to California.[34] Elvira Stevens Barney also benefited from the gold-seeking California immigrants. She braided and sewed straw hats and sold them to pioneers, who were relieved to replace their “hot black wool hats.”[35] Both she and the Rollins participated in and benefited from the larger economy as well as needs in their local communities.

In April 1875 Eliza R. Snow, recognized as the de facto general president of Relief Society, issued a call “to every branch of the Relief Society in Zion to call your mental and physical powers into action, and lead out in establishing Home Industries. This is an important mission which now devolves on us.” She recognized the efforts of the Ogden Relief Society as “an example worthy of imitation in the line of Straw Manufacture.”[36]

Relief Societies throughout the Territory responded. The Farmington Relief Society reported they were beginning “the silk business,” and they “also have a Millinery started, and are saving something by making men’s hats, both from straw and cloth.”[37] The Ephraim Relief Society made “very handsome straw trimmings.”[38] In Mantua, Box Elder County, the Relief Society reported they “intend after a little to have a shop or workhouse built, wherein our sisters will manufacture straw hats, artificial flowers, trimmings, breakfast shawls, hoods, neckties, scarfs,” and other articles.[39] Local priesthood leaders in Payson “applauded the sisters for their talent and ingenuity; the needle and straw work, it was thought, could not be excelled,” reflecting that the utilitarian practice of straw braiding had led to more reputable and refined talent.[40] The Mound Fort Relief Society contributed to the Ogden Stake Relief Society Cooperative Mercantile and Millinery Institution. They gathered, split, braided, and sewed straw hats for sale in the Ogden Straw Store. Annie Dyer Taylor directed the work of the women and also involved children and young girls.[41] The Hyrum, Cache County, Relief Society maintained a braiding school and made hats for summer wear.[42]

The women’s efforts often included the younger generation. Eliza R. Snow credited the Ogden Relief Society again as she noted “forty young ladies and girls have been trained during the last winter to braid and are now being taught in the other branches, sewing, etc.”[43] In Huntsville, the Relief Society organized a “young girls society,” and they shared in the Woman’s Exponent, “we are braiding some straw and piecing up a quilt.”[44] The Willard City Relief Society reported that “last spring we had a braiding school here, that the young sisters might learn braiding; and now the young ladies of Willard are wearing hats of their own manufacture.”[45] The 16th Ward Straw Braiding School began meeting on 3 December 1868, with thirteen “schollars present.”[46] More sisters joined the class as the sessions continued. Ruth Free, Elizabeth Sessions, Betsy Birdenow, and probably Elisabeth Mousley instructed the sisters in good braiding technique, often returning after their tenure as teachers to join with the young girls in their braiding.[47]

The production of braided straw hats was one means by which women contributed economically to their families, their communities, and to the building of Zion, as did Emma Grace Austin, Elizabeth George, Patty Sessions, David and Mary Ann Sharratt Rollins, Harriet Austin Jacobs, Hannah Brandham Williams, Elizabeth Haven Barlow and so many others. Straw braiding was also a means by which younger women could acquire necessary skills to provide for themselves and their families—a means to raise funds for emigration and education, a means to teach others important skills to support themselves, and a means to establish cooperative groups “to assist the poor to live more comfortably and those not so poor to live more frugally.”[48]

The interrelated goals of obedience to the gospel of Jesus Christ, the strong desire for personal and community economic development and improvement, and a unity of perspective and effort exhibited through family and community cooperation characterized the communities of early Latter-day Saints. As they had in the early days of Kirtland and Nauvoo, women continued to play a large role in building “the Latter-day Saint commonwealth” in Utah Territory. Their efforts, both individually and cooperatively, were focused to relieve suffering, to bear the burdens of family and community members, and to teach others the skills necessary to become contributing members of self-sufficient communities. Their organization of and participation in home-industry efforts—from spinning, weaving, sewing, braiding straw, basketry, and the cultivation of silk both at home and in the organization of cooperatives—was a response to calls from their leaders and demonstrated their significant economic contributions to the kingdom.

Notes

[1] William Makepeace Thackeray, Punch, March 1850, as found on History House (http://

[2] British Museum, Pair of woven palm-leaf sandals, Sandal, EA4464 (https://

[3] Harry Inwards, Straw Hats: Their History and Manufacture (London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, 1922), 10.

[4] “Straw Bonnets,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, October 1864, 576.

[5] “Straw Bonnets,” 579–80; Thomas Dublin, “Women’s Work and the Family Economy: Textiles and Palm Leaf Hatmaking in New England, 1830–1850,” Toqueville Review (1983): 298–300.

[6] “Straw Bonnets,” 576.

[7] “Outwork describes paid women’s work generally performed at home, typically by farming families doing traditional handicrafts, such as palm leaf hatmaking, sewing, weaving and other textile industries.” Dublin, “Women’s Work and the Family Economy,” 297–300.

[8] Thomas Dublin, Transforming Women’s Work (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994), 1.

[9] Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), 397–98.

[10] Dublin, Transforming Women’s Work, 4, 10.

[11] Ronald D. Dennis, “Gathering,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 2:536–37.

[12] Hamilton Gardner, History of Lehi (Salt Lake City: Lehi Pioneer Committee and Deseret News, 1913), 334–36.

[13] Daughters of Utah Pioneers, Lesson Committee, comp., Museum Memories (Salt Lake City: International Society of Utah Pioneers, 2011), 3:429–32.

[14] Carol Cornwall Madsen, In Their Own Words: Women and the Story of Nauvoo, Faith and Community (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994), 8–9.

[15] Willard Richards to Hepzibah Richards, letter, 20 January 1837, Levi Richards Family Correspondence, MS 12765, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[16] Janet Peterson and LaRene Gaunt, Elect Ladies (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1990), 24. Jaynanne Morgan Payne, “Eliza R. Snow: First Lady of the Pioneers,” Ensign, September 1973.

[17] Edward W. Tullidge, The Women of Mormondom (New York: Tullidge and Crandall, 1877), 163.

[18] Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “The Significance of Trivia,” Journal of Mormon History 19, no. 1 (1993): 64.

[19] Posted by Ann Laemmlen Lewis on FamilySearch.org, Hannah Brandham (KWNK-JJS), Audrey Nelson, “Hannah Brandham Williams: A Brief Sketch of Her Life”; Mabel W. Christensen and Mildred A. Raymond, “History of Hannah Brandham Williams”; 1851 UK Census of Eaton Bray, Bedfordshire, England, Hannah Brandham, 9.

[20] Israel Barlow, Wikiwant (www.wikiwand.com/

[21] History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1970), 7:351.

[22] Juanita Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout, 1844–1861 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1964), 27.

[23] “Straw Manufactory,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 16 April 1845, 3.

[24] Sarah Southworth Burbank, autobiographical sketch, 1924, [p. 3], MS 3039, Church History Library.

[25] Later Zina Diantha Huntington Jacobs Smith Young. Maureen Ursenbach Beecher, “‘All Things Move in Order in the City’: The Nauvoo Diary of Zina Diantha Huntington Jacobs,” BYU Studies 19, no. 3 (Spring 1979): 304, 310, 312, 318.

[26] Scott G. Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal 1833–1898 (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1984), 6:309. Jill Mulvey Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matthew J. Grow, The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women’s History (Salt Lake City: The Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 177–78, 236–42.

[27] Journal of Discourses, 12:193–94.

[28] “Remarks,” Deseret News, 29 April 1868, 3.

Serve Sm

[29] Sixteenth Ward Relief Society Minutes and Records, 1868–1968, LR 8335 14, vol. 1, 1868–1879, 15 July 1868, 9.

[30] Sixteenth Ward Relief Society Minutes and Records, 1868–1968, LR 8335 14, vol. 1, 1868–1879, 25 November 1868, 25.

[31] Donna Toland Smart, ed., Mormon Midwife: The 1846–1888 Diaries of Patty Bartlett Sessions (Logan, UT: Utah State University, 1997), 406.

[32] FamilySearch.org, Memories, Martha Ann Campton (KWC8–ZP8), “Pioneer History Related to Martha A. Merrell,” contributed by Norma Jean Wood, 19 March 2014.

[33] DUP Lesson Committee, comp., “Harriet Austin Jacobs,” Daughters of Utah Pioneers, Pioneer Pathways (Salt Lake City: International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 2004), 7:354–55. “Lehi’s Pioneer Milliner, Harriet Austin Jacobs,” Lehi Free Press, 20 July 2017.

[34] Lesson Committee, Daughters of Utah Pioneers, Museum Memories (Salt Lake City: International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 2011), 3:438.

[35] Elvira Stevens Barney, The Stevens Genealogy Embracing Branches of the Family Descended from Puritan Ancestry (Salt Lake City: Skelton, 1907), 262, 270.

[36] “To Every Branch of the Relief Society in Zion,” Woman’s Exponent, 1 April 1875, 164–65.

[37] “R.S. Reports,” Woman’s Exponent, 15 August 1875, 42.

[38] “R.S. Reports,” Woman’s Exponent, 15 August 1875, 42.

[39] “R.S. Reports,” Woman’s Exponent, 1 March 1876, 146.

[40] “R.S. Reports,” Woman’s Exponent, 1 July 1876, 22.

[41] Ogden Stake, Ogden Stake Relief Society History, vol. 2, 1908–1920, LR 6467 29, Church History Library.

[42] “F. R. Society Reports,” Woman’s Exponent, 1 November 1872, 82.

[43] “To Every Branch of the Relief Society in Zion,” Woman’s Exponent, 1 April 1875, 164–65.

[44] “Little Letters,” Woman’s Exponent, 15 June 1875, 16.

[45] “R.S. Reports,” Woman’s Exponent, 15 August 1875, 42.

[46] Sixteenth Ward Relief Society Minutes and Records, 1868–1968, LR 8335 14, vol. 1, 1868–1879, 3 December 1868, 26

[47] Smart, Mormon Midwife, 406–8.

[48] Leonard J. Arrington, “The Economic Role of Pioneer Mormon Women,” Western Humanities Review 9, no. 2 (Spring 1955): 147.

Appendix: Examples of straw hats made in Utah

A typical ladies leghorn-style hat—referred to as a straw boater; made by Mary Jorgensen Seely in the early 1900s. Note the trim. This bonnet features nine straw flowers and is trimmed with braided horse hair. LDS 84–124–9–2 Church History Museum.

A typical ladies leghorn-style hat—referred to as a straw boater; made by Mary Jorgensen Seely in the early 1900s. Note the trim. This bonnet features nine straw flowers and is trimmed with braided horse hair. LDS 84–124–9–2 Church History Museum.

A ladies linen poke bonnet. The poke bonnet had a section behind the head, into which ladies could “poke,” or tuck their hair. This Dunstable-style hat typically featured a small crown with a wide and rounded front brim. The bonnet features narrow straw-braided trim across the top and around the edges with an extravagant straw flower. It belonged to Sarah Heller Conrad Bunnell. International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers Picture Collection.

A ladies linen poke bonnet. The poke bonnet had a section behind the head, into which ladies could “poke,” or tuck their hair. This Dunstable-style hat typically featured a small crown with a wide and rounded front brim. The bonnet features narrow straw-braided trim across the top and around the edges with an extravagant straw flower. It belonged to Sarah Heller Conrad Bunnell. International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers Picture Collection.

A small exquisite flat hat, an apparent adaptation of the Fanchon and Bergere styles, popular in the 1860s. The size of the cut straw is minute, three braids per strand, two colors per strand, woven and sewn together to cover the frame, and then trimmed with a single strand of braided light straw, several straw blossoms and straw leaves. The donor is unknown. LDS 40–323–1 Church History Museum.

A small exquisite flat hat, an apparent adaptation of the Fanchon and Bergere styles, popular in the 1860s. The size of the cut straw is minute, three braids per strand, two colors per strand, woven and sewn together to cover the frame, and then trimmed with a single strand of braided light straw, several straw blossoms and straw leaves. The donor is unknown. LDS 40–323–1 Church History Museum.