William P. MacKinnon, "Off-the-Books Warfare: Financing the Utah War's Standing Army of Israel," in Business and Religion: The Intersection of Faith and Finance, ed. Matthew G. Godfrey and Michael Hubbard MacKay (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 175–196.

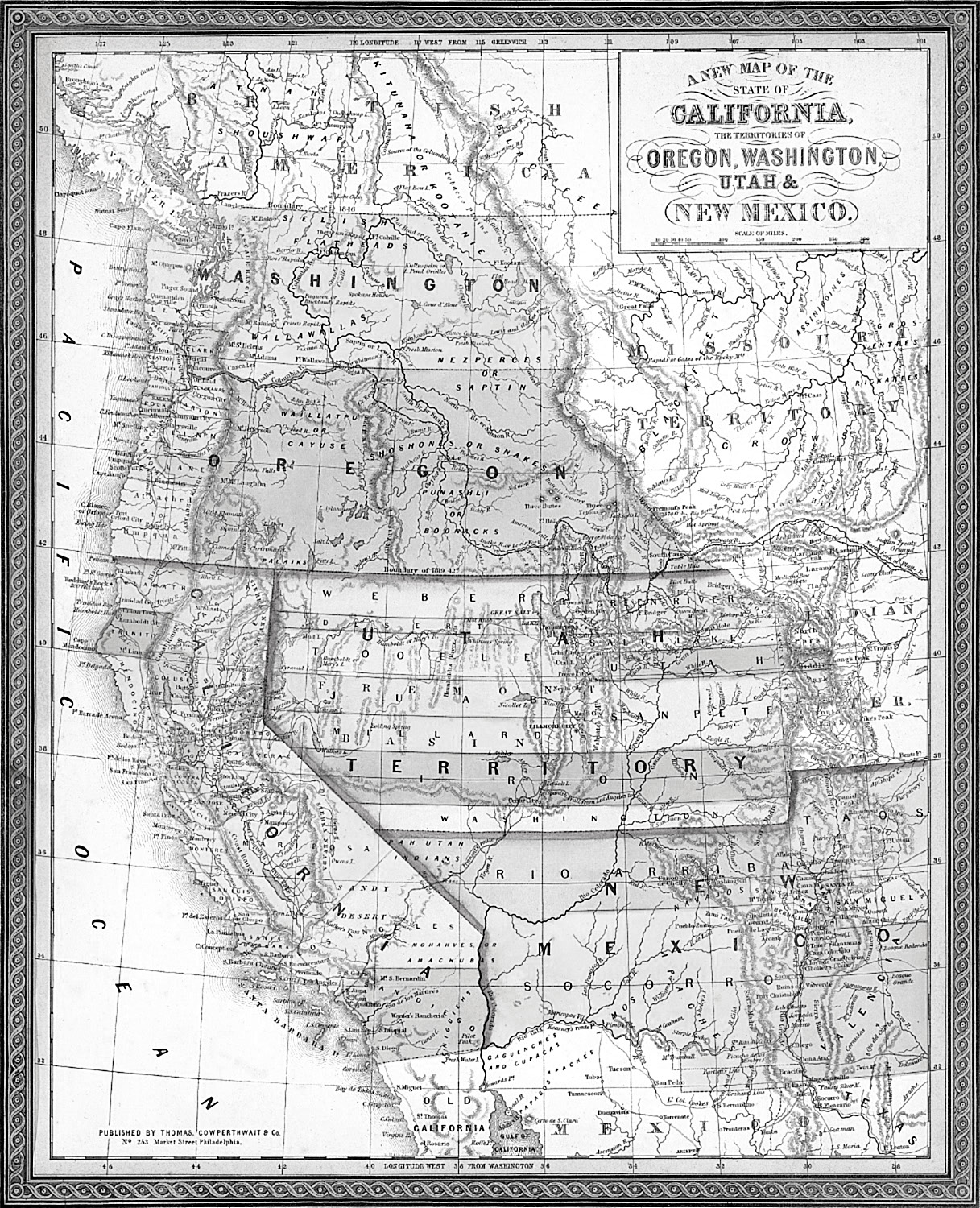

Utah Territory, showing the Utah War’s scope and sweep. During this conflict Utah Territory was 700 miles wide. By 1858 the war had touched virtually the entire American West with international impact on the Pacific Coast possessions of Russia and Great Britain as well as northern Mexico, Spanish Cuba, coastal Central America, the Kingdom of Hawaii, and the Dutch East Indies. Map (1853) by Thomas Cowperthwait & Co., Philadelphia, from the author’s collection.

Utah Territory, showing the Utah War’s scope and sweep. During this conflict Utah Territory was 700 miles wide. By 1858 the war had touched virtually the entire American West with international impact on the Pacific Coast possessions of Russia and Great Britain as well as northern Mexico, Spanish Cuba, coastal Central America, the Kingdom of Hawaii, and the Dutch East Indies. Map (1853) by Thomas Cowperthwait & Co., Philadelphia, from the author’s collection.

To determine the war’s cost for either side, let alone the totality of its economic impact during the country’s most severe recession in twenty years, would be a fascinating but daunting study far beyond the scope of this essay.[1] What is possible here, though, is a limited examination of how Brigham Young found the wherewithal to conduct his side of the conflict and to do so by focusing on just one of the multiple, incredibly costly initiatives that he launched in the fall of 1857 to deal with the approach of the US Army’s Utah Expedition. I refer to Brigham Young’s secret creation of the Standing Army of Israel, a private 1,000-man cavalry brigade intended to extend the combat reach of the territorial militia or Nauvoo Legion.

Through an exploration of what the Standing Army was and how it was financed, the equally short but costly sagas of the Y. X. Carrying Company and the Move South will have a clearer context.[2] All three initiatives were bold ventures sharing decision-making characteristics and methodologies that were hallmarks of Brigham Young’s distinctive leadership. His was a decisive style characterized by the exercise of intuitive judgment, improvisation, and what could be called “situational ad hockery.” It was an operational approach very different from that of today’s more careful, budget-oriented Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Background

In addition to his plethora of formal church, civil, and military titles, Brigham Young was an accomplished woodworker, glazer, and painter as well as an amateur architect and civil engineer. For purposes of this essay, I will argue that, in many respects, Young was also at heart an auditor, although he would probably bridle at such a descriptor.

Along with the surviving tsunami of letters and journals that Brigham Young generated, are hundreds of financial ledgers in which he directed his clerks and business managers to post the extent and cost of a wide range of church, business, and personal activities. At the time of Young’s death in 1877 he left 454 account books dealing with his personal financial affairs and another forty-five shelf feet of ledgers pertaining to church affairs.[3] This material was so extensive and the personal and church transactions so intertwined—even murky—that it took a work group of two apostles and the nineteenth-century equivalent of a certified public accountant several years to untangle the complexities involved so that a fair settlement of the estate could be proposed to the members of Young’s large extended family.[4] So powerful was Young’s reputation for record keeping and micromanaging that in 1871, after only a one-day visit to Salt Lake City, a Gentile traveler from Boston felt compelled to report, “The great ledgers, the strong safes, are in his office; he is his own Chancellor of the Exchequer, although he never unfolds his budget; he counter signs his own signatures, he audits his own accounts.”[5]

The use to which Brigham Young put this massive body of financial records is elusive. To me it is clear that these ledgers were not used to determine the cost of the Utah War to the Church and its members or to reconcile these expenditures against the limitations of a budget imposed by either Utah’s territorial legislature or the Church’s First Presidency. Neither were these books intended to provide analytical information for important make-or-buy decisions such as the cost effectiveness of manufacturing gunpowder and revolvers in Utah versus buying and freighting such items from California and the Kansas-Missouri frontier. There were no such budgets, analyses, and feasibility studies.

Records of the Standing Army of Israel. To arm the new Standing Army, Maj. Howard Egan, one of Brigham Young’s most audacious officers, scoured southern California in a risky quest for munitions. In January 1858 he returned to Salt Lake City packing 675 lbs. of gunpowder, 30,000 percussion caps, and 100 lbs. of ballistic lead, probably requisitioned from the Church-operated mine near Las Vegas. Notwithstanding Egan’s exhaustion, he had to complete paperwork like this with Col. Thomas W. Ellerbeck, Chief of Ordnance, and then again with Brig. Gen. Lewis Robison, Quartermaster General. From the William M. Egan Papers, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Library, New Haven; other similar receipts in Brigham Young Financial Papers, Special Collections, Merrill-Cazier Library, Utah State University, Logan, Utah.

After studying finance at the Harvard Business School, working for ten years in General Motors’ corporate financial staff in New York, and studying Latter-day Saint history for sixty years, I conclude that what was going on in Salt Lake City during the 1850s was a matter of recording transactions primarily for the sake of keeping records. It was an emphasis on booking accounting entries without a clear end use in mind—one that evokes Oscar Wilde’s aphorism: “a cynic is a man who knows the price of everything but the value of nothing.”

A prime example of this behavior came in mid-October 1857 in the immediate aftermath of Nauvoo Legion lieutenant Bill Hickman’s murder of Richard E. Yates, a non–Latter-day Saint civilian ammunition trader who resisted Brigham Young’s demand to sell his inventory of gunpowder to the Legion. When Yates instead sold his munitions to the US Army’s Utah Expedition, he was consigned to a shallow grave in Echo Canyon near Legion headquarters. Upon hearing of this war atrocity, President Young’s concern was not that it had taken place but rather that a complete inventory be made of the animals and goods seized from the trader: “Yates & partner have sold [the army] beef, oxen, ammunition & therefore take and keep what you can find belonging to them, keeping an accurate account of the same. Use the blankets and clothing as well as beef and other supplies as needed for the boys, also keep an accurate account of each issue.”[6] Why the need for such records in a murder case? The reason is unclear, especially since no effort was made to contact Yates’s family in the Midwest to transmit the value of his “estate.” Neither was an accounting or settlement proffered to Mrs. Yates in the 1870s when she visited Salt Lake City to attend the trial of Hickman and others indicted for her husband’s murder nearly fifteen years earlier.

When it became clear to Brigham Young in the summer of 1857 that he had on his hands a serious armed confrontation, if not a full-blown war, he did not undertake what Abraham Lincoln was to do four years later. With the US Treasury drained by the impact of the Utah War and the attack on Fort Sumter a reality, Lincoln called Congress into an emergency session during the summer of 1861 to begin the traditional American behavior of seeking financial support and sanction for a major military effort through the congressional process of debate, appropriation, and authorization.

Young, by contrast, chose not to summon Utah’s territorial legislature until 15 December 1857, described the Utah Expedition bivouacked at Fort Bridger—the largest garrison in North America—as mere rumor, never asked the legislature to fund the military activities of the Nauvoo Legion, and instead simply plunged into an extensive, unbudgeted military campaign. He financed this effort on an as-needed, ad hoc basis out of a combination of general Church tithing funds and the in-kind contributions of individual Utahns. Through this process, Brigham Young armed, equipped, and fed the Nauvoo Legion.[7]

Young’s unilateral requisitions on Utah’s population for cash, goods, and services to support the Legion were, of course, grounded in a decades-long tradition of volunteerism within the Church’s stakes and wards. The most common practice of that nature was that of abruptly calling members to distant, perhaps international, missions without any Church financial support for the missionary or the family left behind. Hence arose the tradition of hundreds of Latter-day Saint missionaries afield “without purse or script,” trusting for support from a combination of divine providence, the generosity of local members, and the kindness of strangers.

During the Utah War, such levies sometimes took place in high-handed fashion, as in the revealing case of prosperous farmer John Pack of Bountiful, Utah. Pack’s experience is known because he had the standing and temerity to complain in writing to Brigham Young in August 1857 after a six-man Legion detachment arrived in his wheat field at the command of the local bishop, seized one of his draft horses, and threatened Pack’s juvenile farmhands with summary execution when they resisted the requisition. As a dismayed farmer Pack put it to the unwelcome foraging party, “Bishops [do] not send an armed force to execute their orders.”[8] In this case that is precisely what Bountiful’s Bishop John Stoker did.

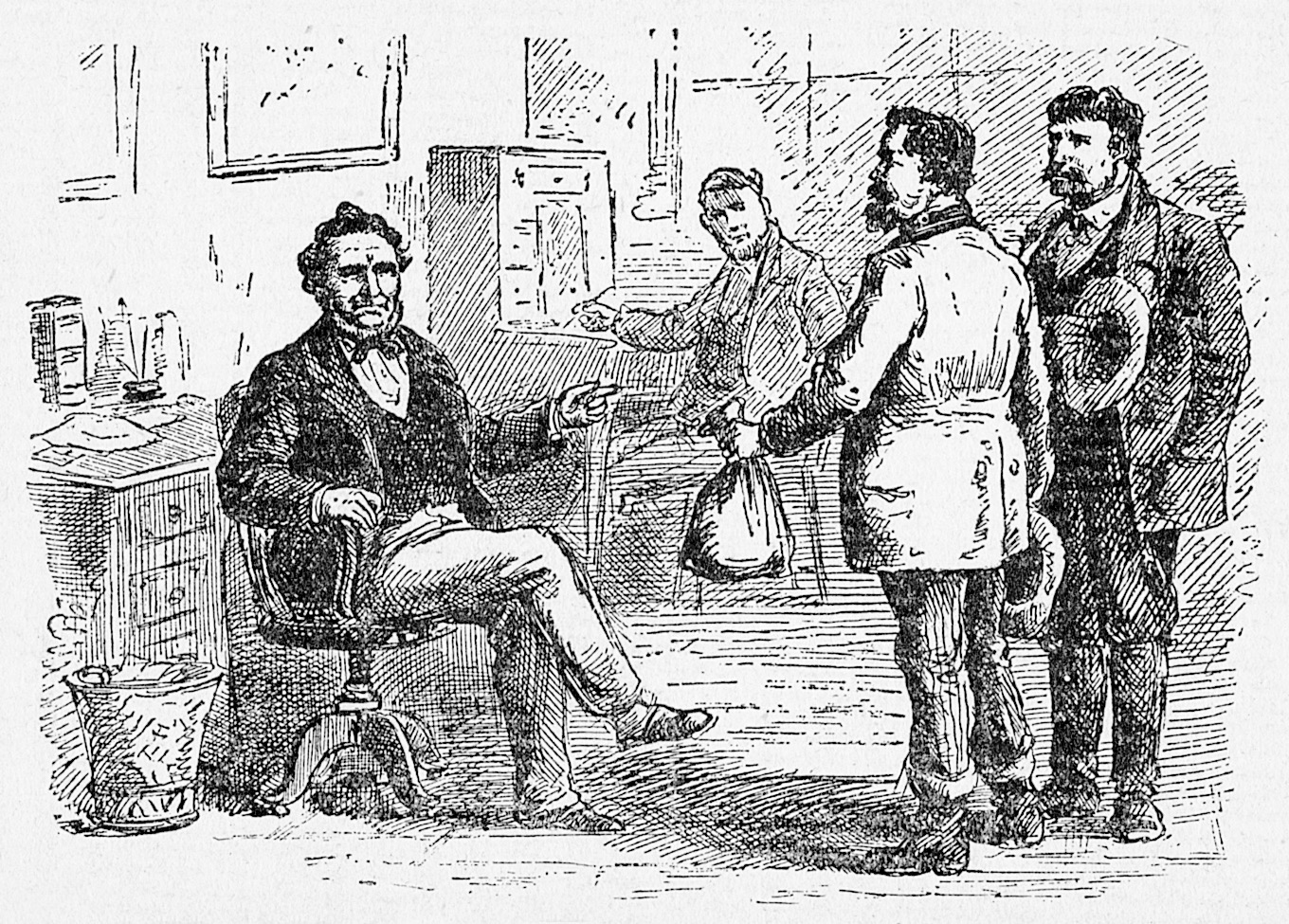

Lt. William A. Hickman delivers cash stripped from ammunition trader Richard E. Yates, Brigham Young’s Office, October 1857. In a drawing illustrating his lurid 1872 memoirs, Brigham’s Destroying Angel, Hickman, a free-ranging officer in both the Nauvoo Legion and Standing Army, depicts his delivery of $900 in Yates’s gold to his leader as one of Young’s office clerks prepares a receipt. Hickman claimed that his plea for a share of this cash was rebuffed, with Young ruling “it must go towards defraying the expense of the war.” Both men were later indicted (but never tried) for Yates’s murder in Echo Canyon.

Lt. William A. Hickman delivers cash stripped from ammunition trader Richard E. Yates, Brigham Young’s Office, October 1857. In a drawing illustrating his lurid 1872 memoirs, Brigham’s Destroying Angel, Hickman, a free-ranging officer in both the Nauvoo Legion and Standing Army, depicts his delivery of $900 in Yates’s gold to his leader as one of Young’s office clerks prepares a receipt. Hickman claimed that his plea for a share of this cash was rebuffed, with Young ruling “it must go towards defraying the expense of the war.” Both men were later indicted (but never tried) for Yates’s murder in Echo Canyon.

Most requisitions, though, were of a more gentle nature than Pack experienced at the hands of a Nauvoo Legion foraging detail. In his study of this subject, Ralph Hansen noted, “When Utah Territory was threatened by a United States Army force in 1857, the Church in all its branches participated in supplying the army [militia] in the field. No longer was the paymaster required to find funds for the men. They were serving on missions for the L. D. S. Church. In the capacity as missionaries they were supported by the wards in which they made their homes. . . . At no time during the course of its history did the Nauvoo Legion take upon itself the responsibility of outfitting its membership. The uniform, when obtainable, was purchased at the discretion of the individual,” with most of the enlisted troops foregoing such clothing and instead choosing to take up arms attired as the somewhat ill-clad frontiersmen they were.[9]

Starting in August 1857, Young also announced his intent to provide for the Legion’s needs through the forcible acquisition, sometimes at gunpoint, of horses, mules, beef cattle, arms, and munitions from US Army contractors and hapless travelers who stumbled into the middle of the conflict en route to the Pacific Coast. Again the Yates case is instructive, illustrating not only President Young’s emphasis on receipts and meaningless records but the unmistakable directness with which he ordered his military subordinates to take what they needed—with or without compensation—to prosecute the war. These were instructions that led directly to atrocities, especially after General D. H. Wells, the Legion’s commander, told his quartermaster general at Fort Bridger on 1 September, “Mr Yates I understand refuses to sell, although offered by Mr. John Kimball 50 percent advance for his entire stock over cost and carriage [freight]. This is to you therefore [authorization] not to permit the ammunition to leave this part of the country, it is wanted and you will please see that it goes in the proper direction. If he comes here, with it all right, but he talks of going to the Flathead country [Oregon Territory]. . . . Keep a good look out, and let us know about matters as soon as you receive. We have just learned that Mr. Yates now asks 60 per cent advance and includes his waggons, which no person would do, take his ammunition and give your receipt for it or pay him for it if you can for we must have it, forward it here as soon as you can.” A week later Brigham Young informed the same officer, “We want the Government [wagon] trains to come in inasmuch as the Government has refused to pay the [Utah] Legislature, the Secretary and several other debts which we hold against them. We think if they get here [with these goods] we shall collect these debts.”[10]

This resort to looting was not a Latter-day Saint tradition, but it was situational behavior encouraged in 1857 by senior leaders that had a negative, unsavory impact on discipline within the Legion, if not the territory broadly. Such methods stained the Church’s reputation, especially after the murders and looting in the fall of 1857 involving not only trader Yates but the six-man Aiken party and, most disastrously, the far larger and more prosperous Baker-Fancher party of Mountain Meadows notoriety.[11]

The Standing Army of Israel

As the fall of 1857 wore on, scouts on the Great Plains made it clear that the army was not going to winter at Fort Laramie and was instead headed for Fort Bridger, if not the Salt Lake Valley. In response, an increasingly alarmed President Young’s methods for prosecuting and supporting the war became more draconian.

On 17 October, he sent his senior leaders in the field a rambling letter full of suggestions, advice, and commands ranging from the whimsical to the deadly. For example, he dispensed advice on what Legionnaires should shout to entice army deserters as well as the merits of fabricating medieval longbows and crossbows to augment the use of scarce firearms.

As he had done earlier in August, he also sent a clear signal that he fully intended to seize the possessions of private merchants as well as government contractors—looting on a grand scale. More ominously, he abandoned his previous restrictions on bloodshed and directed that, should the Utah Expedition move west of Fort Bridger, the Legion was to use lethal force, killing first the army’s officers, civilian guides, and noncommissioned officers. Here was the stuff from which treason and murder indictments were to flow.

In terms of manpower, Young’s landmark letter added that “it has been suggested to my mind . . . to select some 2000 of the right kind of men . . . and organize them into a standing army to be most—or all—the time on duty in the field. And so appointed on the different . . . approaches to our Territory as circumstances may from time to time require, and each Ward supporting so many families so that our soldiers can be perfectly free. About 100 on the Southern route to California, about 200 on the [western St.] Mary’s River route, 100 north to watch for Oregonians, and the remainder to watch the different eastern routes, the latter so placing their stores and rendezvous that they can operate together or apart . . . we really do think that 2000 men of the right stripe can prevent all the armies of the world from coming here.”[12]

The origins of this notion are not clear, but it appears that it came directly and solely from President Young rather than from within the Nauvoo Legion’s command structure. In a public discourse the next day, Young repeated the idea without having waited for feedback from key subordinates. Thus began the development of what became the Standing Army of Israel.[13]

There are signs that the concept of supplementing the Nauvoo Legion—technically part of the nation’s organized militia—with a “regular” two-thousand-man military force of infantry and mounted troops was not greeted with enthusiasm. The implicit economic burden of such a new thrust—vague as it was at that stage—would have been daunting in addition to the strain already felt throughout the territory to support the Nauvoo Legion. As in all complex organizations in which the supreme leader peppers his subordinates with creative ideas of varying practicality, this one met some resistance. As one can imagine, such behavior took the form not of open debate or overt opposition but rather that of a time-tested organizational way of dealing with such situations in low-risk fashion—superficial acceptance and compliance accompanied by subterranean foot-dragging. Sensing these dynamics, at the end of 1857 Young gently reminded General Wells, the Legion’s uniformed commander and his second counselor in the First Presidency, that he needed to get on with the formation of the new force.

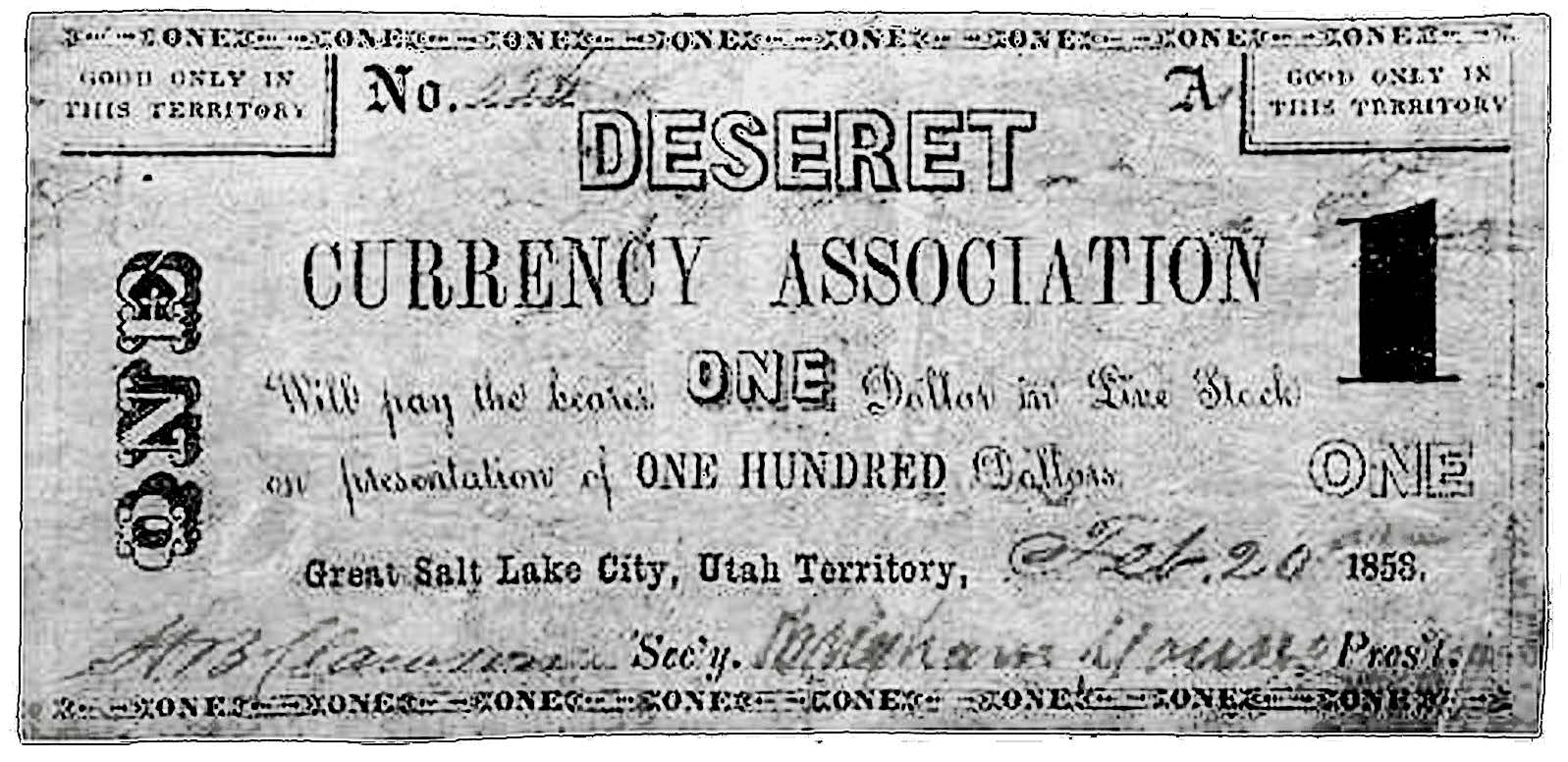

Currency Association Note. Hand signed by Brigham Young and his son-in-law Brig. Gen. Hiram B. Clawson. This note was issued 20 February 1858, five days before Thomas L. Kane of Philadelphia arrived in Salt Lake City on a mission to mediate the war. So urgent was the need to finance the war that this early “A” Series note was typeset and printed in the office of the Deseret News rather than engraved, as were subsequent, more elegant issues. A great rarity among collectors, this note sold at auction for $9,775 in 2004 although originally issued in a $1 denomination. Because D.C.A. notes were uniquely backed with church livestock and often bore an engraved image of cattle, some members referred to them as “moo currency.” Photo courtesy of Stack’s Bowers Gallery, Santa Ana, Calif.

During January 1858, the organizational gloves came off. Brigham Young became far more forceful about bringing the Standing Army into being as an active fighting force while simultaneously unveiling a new mechanism for financing the Utah War—the issuance and sale of notes by a newly created, Church-sponsored entity, the Deseret Currency Association. In effect, through the association Brigham Young was undertaking to print paper money in cash-starved Utah, where gold and silver coins were in extremely short supply. It was a controversial financing scheme born out of necessity and evoking memories of Joseph Smith’s disastrous entry into the banking (and banknote) business in Kirtland, Ohio, twenty years earlier.

All this was unveiled at a community-wide business meeting held in the Salt Lake Tabernacle on 19 January. At this session Young signaled that he had backed away from his earlier plans for a 2,000-man mixed force of infantry and mounted troops but was insistent about creating a Standing Army consisting of a 1,000-person cavalry brigade. He now expected the Latter-day Saints to raise and equip such a force without further delay. It was to be commanded by Brig. Gen. William H. Kimball, a Nauvoo Legion colonel and son of Brigham’s first counselor Heber C. Kimball.

Exactly what the Standing Army’s mission was and how it meshed with that of the Nauvoo Legion was unclear. It was an important ambiguity, especially since the officer corps of both forces overlapped. Unstated publicly was Young’s secret intent to use the Standing Army to break a stalemate in the war by striking a decisive blow against Fort Bridger in the spring of 1858 and then thrusting further east to capture Fort Laramie, Nebraska Territory. Doing so with a privately raised cavalry brigade reporting to him as Church president rather than through the more conventional Nauvoo Legion would ensure the availability of troops not otherwise available to him if he lost the governorship and its command of Utah’s militia.

What was clear is that Brigham Young expected each trooper in the Standing Army to be equipped by his family or community with a horse, pack mule, rifle, revolver, clothing, and provisions for a year of campaigning—a substantial outlay far exceeding the somewhat ragtag level of support by which Legionnaires were armed, equipped, and clothed. It is highly revealing that in the Standing Army’s table of organization Young made provision for plenty of aides-de-camp and adjutants but named no officer to serve in the normally crucial assignments of quartermaster or chief of ordnance. With volunteerism, improvisation, and foraging (raiding) as the operative methodologies for building and sustaining the Standing Army, there was apparently no need for such staff assignments.

By mid-January a committee of prominent citizens of the West Jordan Ward near Salt Lake City provided Young with a list of thirty-six families committed to supporting a total of fifteen men for the Standing Army. Acting on their own rule of thumb that “every three thousand dollars worth of property should outfit Support and Sustain One man and his family,” groups of families (usually three) planned to pool their resources to equip and provision a single cavalryman. The best-known man on the list, William Adams (“Bill”) Hickman, the killer of ammunition trader Yates, agreed to support two soldiers, one of whom may have been himself. As Apostle George A. Smith explained to his younger brother in England, “Porter Rockwell and Wm Hickman are getting up two independent companies. All the men selected are well mounted, expert riders, and dead shots—armed with Rifles and revolvers.”[14]

Records for the wards in Ogden are especially helpful in shedding light on that town’s contributions. In early February William Luck, a visiting Nauvoo Legion adjutant, recorded: “Thursday attended a mass meeting held [in Ogden] for the purpose of selecting some young men for the standing army. Saturday morning . . . started again for home . . . this Mon. called upon to furnish 35 men for the standing army of Utah. A tax levied to fit them up. The tax amounted to 17%. My taxes amounted to $95.00. Gave some clothing, etc.” A list dated 1 February 1858, recorded eleven members of Ogden’s 1st Ward as the donors of a wide range of items: $25 in cash, two horses, two saddles, seventeen bushels of unmilled wheat, oats, and corn, one hundred pounds of pork, three steers, one revolver, a shirt, four rifles, one hundred pounds of flour, and two blankets. Two days later another Ogden ward met to consider its support for the Standing Army, with one attendee committing to contribute $100 while three other men agreed to “fit out” in shares the equivalent of one cavalryman.[15]

In Bountiful, Joseph Holbrook, clearly one of the community’s more prosperous residents, itemized the elements of his financial commitment to outfit two men for the Standing Army, a list that totaled a staggering $1,000.

Despite these efforts, Brigham Young was impatient, and he said so in blistering terms in a discourse on 28 February that took to task bishops, military leaders, the Standing Army’s potential recruits, and even their womenfolk:

We have called upon Bishops and wards to sustain a certain portion of the community to act in our defense. I want to correct some mistakes, [because] reports have come to me which convinces me that they have no idea of what is required of them. Some have asked what it will take to sustain one man for a year. The Bill for this has been made out for $700, including fit out of animals, arms and ammunition. . . . This was not designed in the first place. The men that we called to go out we want them to have art enough and brain enough to fit themselves out instead of a Bishop having to furnish for 20 individuals $700 each to fit them out. . . . Do as the Indians do, they take a bow and arrow, a Lariat, a Blanket and a Breech-clout, and they expect to get [forage for] what they need. I tell you these things . . . for my bones have burned for weeks because of the ignorance and foolery of Bishops and men.[16]

It was a substantial public overreaction on Young’s part of the sort reflected in a sarcastic letter that he had written earlier in February to James G. Willie, bishop of Salt Lake City’s 7th Ward and leader of one of the emigration companies caught in the 1856 Willie-Martin handcart disaster. Perceiving a lack of enthusiasm for the Standing Army in Willie’s ward, Young applied pressure in terms that no Latter-day Saint congregation was happy to hear or willing to resist, especially one led by a man who less than two years earlier had suffered an ordeal that involved the greatest loss of life in the entire American overland experience. In scathing terms mocking the financial condition of Bishop Willie’s flock, Young offered to buy out the property of the entire ward for $25,000 and demanded “an immediate answer.”

Brigham Young’s volcanic discourse touched nerves throughout Utah. At a meeting in the Salt Lake Stake’s North Cottonwood Ward, Col. P. C. Merrill felt it necessary to clarify that, “with regard to the words of Bro Brigham last Sunday about the fitting out the army, [they] were not applicable to our Bishop at all.” Merrill’s congregation then redoubled its already substantial efforts in support of the Standing Army.

Concerns also arose in Utah County’s town of Provo, a community not always viewed as being at one with Brigham Young’s more demanding initiatives. From there, on 16 February, James C. Snow wrote to Apostle George A. Smith to express alarm that Provo was being undeservedly tarred with the brush of recalcitrance with respect to its support for the Standing Army. Acknowledging that Provo had “seemed to be a speckled Bird in times gone by whether deserving or undeserving to be thrown a shot at,” Snow took issue with rumors being spread in Salt Lake City by a controversial former resident with the improbable name Philander Colton Buckmaker,

that the people of Provo would Rebel before they would be taxed for the fitting out of the Standing Army. Also that we had Taxed those who had been called to go with [the Standing Army companies led by] Porter Rockwell and Wm Hickman which is utterly false, and without the least Shadow of truth and he is the only one that has Mutanized [mutinied] to my Knowledge, and I hope that he has not, also that he will retrace his steps and like the old woman in Boston, when he gets sober acknowledge that he was in the fault and Provo is sober. The Brethren have been and are doing well in fitting up the boys and there seems to be no lack in making the necessary exertions.[17]

If there was nervousness in Salt Lake and Utah Counties about the war’s cost and how the Standing Army was to be financed, the Buchanan administration experienced its own anxieties. Smarting under congressional pushback over the president’s proposal to expand the US Army and the country’s growing restlessness over a mushrooming budget deficit, the Democratic Party’s “organ,” the Washington Union, lashed out editorially:

The opposition blunder when they suppose they can make capital against the Utah expedition by declaiming against its cost. The religious sentiment of the whole country is stirred up against this Mormon imposture that has planted itself in the heart of our continent, and bids defiance to our laws and our authority. . . . The opposition, if they feel so disposed, may try the experiment of making a demagogue opposition to this war on the ground of its cost. The democracy will gladly accept the issue. If the war feeling was ever strong and universal among our people, it is so in regard to this Mormon rebellion—it is so in regard to the military measures on foot to put it down and crush it out.[18]

Meanwhile in Nephi, resourceful, self-reliant behavior was exhibited by Homer Brown, a farmer and new trooper in the Standing Army. During February 1858 Brown assembled the animals, weapons, and clothing he required by a combination of barter, home craftsmanship (he made his own saddle and stirrups), and, as a last resort, the outlay of small amounts of cash to buy items such as a hat. Homer Brown was a member of the Standing Army who needed no tongue-lashing from leaders as motivation. He just heeded counsel and quietly got on with the task of equipping himself.

And then, suddenly, it was all for naught. On 21 March 1858 Brigham Young unexpectedly announced still another gargantuan new initiative, the Move South. It was to be an exodus of some thirty thousand Saints from northern Utah and Salt Lake City that would become the country’s greatest mass movement of refugees since the flight of British Loyalists to Canada during the American Revolution. With the launch of the Move South, Young also announced without explanation the abolition of the Standing Army of Israel. Collapse of his private cavalry brigade was a bitter pill for Young, one for which he paid a price of unknown cost in terms of diminished credibility with his flock.

On 24 March he informed Bishop Aaron Johnson of Springville, a Legion brigadier general, that “the standing army is superseded, and justice requires that property collected for our army be returned to those who furnished it, at least as far as they call for it.” Charles Derry, an English convert and subsequent apostate, viewed the creation and dissolution of the Standing Army with cynicism. Writing from a vantage point outside the Church in 1908, Utah War veteran Derry recalled, “The means were raised, the men equipped, but perhaps Uncle Sam’s icy fetters were broken and the mountains of snow had melted and Brother Brigham saw the fiery determination in Uncle Sam’s eye to enter these valleys if he had to wade through the blood of Brigham’s hosts; for Brigham declared the Lord accepted the sacrifice and the standing army was disbanded. But Brigham’s lord forgot to return the poor man’s cow, or horse, etc., now that they were no longer needed. Perhaps Brigham needed them.” In July 1858 an anonymous apostate complained to the New York Times that after “the army was abolished, and notice given that all property subscribed would be refunded, how much of [live]stock, clothing or saddlery, to say nothing of wheat and other food which each had given, was returned to the owners? Not three cents out of every ten.”

The notes of the Deseret Currency Association issued to finance a portion of the war’s cost—some $40,146 printed between 19 February and 27 March 1858—were viewed with similar cynicism. Over the subsequent years Utahns who had acquired these notes in payment for their war materiel or services were largely unable to redeem them for specie. Essentially, they became worthless to the holder unless he was lucky enough to negotiate their use as tithing credit.[19]

Thus ended the Standing Army of Israel, another of Brigham Young’s ad hoc, unplanned improvisations to prosecute the Utah War. In a sense, it was an undertaking not unlike his repeated dispatch of exploring parties to Utah’s west deserts in the spring of 1858 to seek out what he mistakenly believed were large oases of refuge.[20] The Standing Army was essentially financed “off the books” by the personal contributions of an already hard-pressed, economically over-burdened territorial population. But then the biggest, most expensive initiative of them all—the Move South—welled up unexpectedly to place a still heavier burden on these hardscrabble, incredibly loyal people. In the process of this enormous mass exodus to an undisclosed destination, the earlier sacrifice put forth to create the short-lived Standing Army of Israel was supplanted in Latter-day Saint memory.

I have argued elsewhere that the Utah War had no winners, only losers.[21] Among other factors, the intricacies of the conflict’s financing arrangements and the leadership quirks on both sides bear out this judgment. The war’s enormous costs damaged the economies of Utah Territory and the United States as well as the reputations of individuals and institutions in both places.[22]

Notes

[1] For an interesting but inconclusive attempt by the Latter-day Saint side to calculate the cost of the Utah War to the US government, see Schedule of the Campaign of 1858 (n.d.), Historian’s Office Letterpress Copybooks, vol. 1 (1854–1861), 233, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. This estimate was apparently developed in September 1858, perhaps to provide insight into the economic unsustainability of continued federal intervention in Utah.

[2] In this volume see R. Devan Jensen, “The Mail, the Trail, and the War: Rise and Fall of the Brigham Young Express and Carrying Company.”

[3] “Brigham Young’s Personal Finances,” History Blazer, April 1996, 25–26.

[4] Leonard J. Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985), 250–401; and Arrington, “The Settlement of the Brigham Young Estate, 1877–79,” Pacific Historical Review 21 (February 1952): 1–20.

[5] Hamilton A. Hill, “A Sunday in Great Salt Lake City,” Penn Monthly 2 (March 1871): 139.

[6] Brigham Young to George D. Grant, Robert T. Burton, and Lewis Robison, 26 October 1857, Nauvoo Legion (Utah), Adjt. Gen. Records 1851–1870, p. 151, Church History Library.

[7] Governor’s Message to Utah Legislative Assembly, 15 December 1857. Deseret News, 23 December 1857, 3/

[8] John Pack to Brigham Young, 22 August 1857, Church History Library.

[9] Ralph Hansen, “Administrative History of the Nauvoo Legion in Utah” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1954), 53, 58.

[10] Daniel H. Wells to Lewis Robison, 1 September 1857 and Brigham Young to Lewis Robison, 7 September 1857, both Church History Library.

[11] For Young’s important discourse of 16 August 1857, as well as a related analysis of wartime looting by the Nauvoo Legion and its negative impact on discipline within that force, see William P. MacKinnon, ed., At Sword’s Point, Part 1: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858 (Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark, 2008), 238–43, 316–17, 326.

[12] Brigham Young to Daniel H. Wells, John Taylor, and George A. Smith, 17 October 1857, Church History Library.

[13] The balance of this article’s discussion of the Standing Army is adapted from William P. MacKinnon, ed., At Sword’s Point, Part 2: A Documentary History of the Utah War, 1858–1859 (Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark, 2016), 68–72, 246–55, 323–24.

[14] George A. Smith to John L. Smith, 5 February 1858, Historian’s Office, Letterpress Books, Church History Library.

[15] A List of Donations towards Fitting Out Soldiers for the Army of Israel, MS, BYU Library printed in Hansen, “Administrative History of the Nauvoo Legion in Utah,” 53–4.

[16] Brigham Young, discourse, 28 February 1858, in The Complete Discourses of Brigham Young, ed. Richard S. Van Wagoner (Salt Lake City: Smith-Pettit Foundation, 2009), 3:1408–11.

[17] James C. Snow to George A. Smith, 16 February 1858, George A. Smith Papers, Church History Library. Snow’s obscure reference to a “speckled bird” runs to Joseph Smith Jr.’s characterization of his secretary-ghostwriter W. W. Phelps’s talents and eccentricities, which, in turn, was derived from a biblical verse, Jeremiah 12:9. Rumors about support for the Standing Army roles of lieutenants Rockwell and Hickman may have been prompted by their notoriety as the most violent of Brigham Young’s “b’hoys.”

[18] Editorial, “The Utah Expedition,” Washington (D.C.) Union, 20 April 1858, 2/

[19] Leonard J. Arrington, “Mormon Finance and the Utah War,” Utah Historical Quarterly 20 (July 1952): 219–37.

[20] Clifford L. Stott, Search for Sanctuary: Brigham Young and the White Mountain Expedition (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1984).

[21] MacKinnon, At Sword’s Point, Part 2, 618–20.

[22] Brigham Young was not the only Utah War leader to approach matters of financing in an unorthodox fashion. For example, with Congress in recess during the spring and summer of 1857 and no budget authorization in effect when the Utah Expedition was initiated, US Secretary of War John B. Floyd took the unprecedented step of secretly paying army freighters and other contractors with unauthorized “acceptances” (IOUs). He issued millions of dollars of this paper, later arguing that he had to do this to support the distant Utah Expedition in the field. When President Buchanan became aware of Floyd’s irregular practice in the late summer of 1857, he ordered him to stop such financing and to await proper authorization once Congress reconvened in early December. When the army appropriation bill fell victim to protracted budget wrangling in early 1858, a desperate Floyd covertly resumed issuing acceptances over his signature to finance the Utah War much as Brigham Young would soon sign notes of the Deseret Currency Association to support his Standing Army. In December 1860 Buchanan became aware of this resumption as well as the fact that a distant relative of the secretary, an employee of the Interior Department, had “borrowed” over $870,000 in departmental bonds to forestall discovery of Floyd’s financing arrangement. The president chose not to disclose this scandal and forced Floyd to resign but permitted him to preserve family honor by enabling the fiction that Floyd was departing over the secession crisis. When news of this scandal leaked, a federal grand jury in Washington indicted Floyd for malfeasance in office during January 1861 as he fled south and soon became a Confederate general. Combined with a series of other scandals involving Floyd’s stewardship and the president’s own controversial exercise of the patronage power, an odor of corruption arose that still marks Buchanan’s reputation. John M. Belohlavek, “The Politics of Scandal: A Reassessment of John B. Floyd as Secretary of War,” West Virginia History 31 (April 1971): 145–60.