R. Devan Jensen, "The Mail, the Trail, and the War: The Brigham Young Express and Carrying Company," in Business and Religion: The Intersection of Faith and Finance, ed. Matthew G. Godfrey and Michael Hubbard MacKay (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 151–174.

Joseph Smith Jr. and members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints boldly professed to belong to “the only true and living church upon the face of the whole earth, with which I, the Lord, am well pleased” (Doctrine and Covenants 1:30). Such statements, proclaimed with missionary zeal, understandably elicited tense responses from neighbors in New York, Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois, culminating in a mob’s 1844 murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, the Saints’ prophet and patriarch. Then, as pressure mounted from citizens of Illinois for the Latter-day Saints to move from Nauvoo, senior apostle Brigham Young deliberated with a secret Church organization called the Council of Fifty as to how and where to move—certainly outside the boundaries of the United States.[1]

Brigham Young, later nicknamed an American Moses,[2] led an 1846 exodus across muddy Iowa to Winter Quarters (north of today’s Omaha) on the west bank of the Missouri River. After wintering there, on 5 April 1847 he led a pioneer company of 143 men, 3 women, and 2 children westward. Church members developed their own trail north of the Platte River to avoid the more crowded Oregon and California Trails on the south side, whose travelers included Missourians, with whom Church members still had uneasy relations. Trailing the main company by a few days because of sickness, “Brother Brigham” arrived in the Salt Lake Valley on 24 July 1847, declaring it to be the right place to build.[3] He wanted to establish the Latter-day Saints as an independent people in the heart of the Rocky Mountains, where they would be free to practice their religion “according to the dictates of [their] own conscience” (Articles of Faith 1:11).

To further his people’s independence, Young wanted to develop an effective mail system, safe transportation across the Great Plains, and local industry that favored Latter-day Saint economic interests, sometimes ostracizing outside entrepreneurs. Within a month of arriving in the Great Salt Lake Valley, he motioned to call the central gathering place “Great Salt Lake City” and designated a site for a building to be called “The Great Basin Post Office.”[4] He then returned to Winter Quarters, assigning members to build settlements and plant and harvest crops to aid later emigrants. Subsequent wagon trains relied on way stations in today’s Nebraska and the rugged high plains of today’s Wyoming before traversing the final arduous, winding passage of climbs and descents into the Great Salt Lake Valley. I will trace Brigham Young’s steps to develop the mail and the trail, focusing on his efforts to launch a tremendously costly express and transportation company that increased federal alarm and factored into the Utah War of 1857–58. These developments resulted in greater distrust between federal officers and Latter-day Saints. According to Leonard J. Arrington, the express company was “the largest single venture yet tackled by the Mormons in the Great Basin . . . [and] a bold and well-conceived enterprise, which if ‘war’ had not been its outcome, would undoubtedly have changed the whole structure of Mormon, and perhaps Western, economic development.”[5] The company certainly made vital developments to a route later adopted by the Pony Express and the transcontinental telegraph system.

An Avalanche of Immigration with Unreliable Mail Delivery

Just as the Saints were struggling to establish a stronghold in the Great Basin, two events only nine days apart triggered an avalanche of immigration through the region: gold was discovered in California on 24 January 1848 (Mormon Battalion members recorded that discovery at Sutter’s Mill),[6] and on 2 February the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ceded the vast area that is now the western United States.[7] Essentially, Uncle Sam’s long arms reached out across the Great Plains to reembrace the Saints.

The trail across the plains thus became a lifeline, transporting western-bound gold rushers, supplies, and mail through what became Utah Territory. Responding to a petition from the Salt Lake settlers, the United States established its first official post office there on 18 January 1849 with Bishop Joseph L. Heywood as postmaster and Almon W. Babbitt as mail contractor.[8] Babbitt would carry mail between Salt Lake City and Kanesville, Iowa, six times a year at his own expense, being compensated by mail fees.[9] Within the Salt Lake Valley, Howard Egan delivered the mail, but many members complained about paying the exorbitant cost.[10]

The 1850s became a decade of rapid western expansion and intense competition to win bids and deliver mail despite daunting obstacles, including primitive mountain roads, infrequent way stations, and American Indian resistance. The US Post Office Department invited competitive bids in 1850 to deliver mail from Independence, Missouri, to Great Salt Lake City. Samuel Woodson and James Brown—both Missourians and therefore suspect to Latter-day Saints—won the bid for thirty-day service. The mail contractors were to leave the first day of each month and arrive by the last day, commencing operations on 1 August.[11] Woodson struggled to deliver on time, building way stations to help his teams. Facing rugged terrain and deep snow from fall to spring between Fort Laramie and Salt Lake City, he subcontracted that portion in 1851 to Feramorz Little, Brigham Young’s nephew. After repeated mail delays, Woodson lost his contract on 30 June 1854.[12] On this route (no. 8911), delays, canceled contracts, and rebidding became the pattern rather than the exception.

Into this competitive scene entered W. M. F. Magraw of Maryland, who won the bid of $14,400 per year for monthly mail service by four-horse coaches.[13] John M. Hockaday joined him as a silent partner, and they convinced Congress to raise their compensation to $30,000 annually.[14] Magraw rode into Salt Lake City on 31 July 1854, noting that the postmaster at Fort Laramie was irresponsible and had not given him any mail. Deseret News editor Albert Carrington optimistically observed that the energetic Magraw would likely improve the mail service, having recently improved mail security by installing brass locks on the mail sacks.[15]

W. M. F. Magraw, from Thomas B. Searight, The Old Pike: A History of the National Road, with Incidents, Accidents, and Anecdotes Thereon (Uniontown,

W. M. F. Magraw, from Thomas B. Searight, The Old Pike: A History of the National Road, with Incidents, Accidents, and Anecdotes Thereon (Uniontown,

PA: T. B. Searight, 1894), 333.

Unfortunately, both Magraw and Hockaday were distracted from giving full attention to the mail as they were busy forming other enterprises. Utahns complained of delayed mail, often due to weather delays and Indian depredations.[16] Salt Lake residents gathered at a June 1856 public assembly to issue a formal complaint about the mail service.[17] At Magraw’s request, the US Senate and House of Representatives canceled his contract and paid him for his losses.[18] Deseret News editor Albert Carrington glibly bade Magraw farewell and wished “that the large amount of government funds, paid to him, for getting in the way of those who would have [the job] . . . may prove as little of a gratification and benefit to him as his mail-course has been to us.”[19] The angry and frustrated Magraw submitted another bid and anxiously awaited the outcome. “To free-enterprising . . . businessmen like Magraw,” Arrington noted, “the rigid personal and business code of Mormonism was a symbol of puritanical superstition and an invitation to open resistance. . . . The church frequently interfered to prevent the uninterrupted operation of free markets; therefore, the church was a combination in restraint of trade. The church encouraged its members to consecrate all their property to the trustee-in-trust; therefore, the church was a monopoly whose power and economic interests were growing stronger and stronger. The church expected extensive donations for community projects and cooperation in their completion and maintenance; therefore, the church was coercive.”[20]

Rise of the Mail Company—Return of Competition

Fast, reliable mail delivery and transportation had become priorities in Utah Territory, and Governor Brigham Young and other territorial leaders had gathered on 2 February 1856 to propose an express line from the Missouri River to the Pacific Coast.[21] Because so many Latter-day Saint emigrants came from the eastern United States or the United Kingdom, the mail was an emotional lifeline to the families left behind, as well as a source of news that was vital to immigration. To secure this express line, Hiram S. Kimball,[22] Governor Young’s undeclared agent, submitted a low bid of $23,000—half of Magraw’s new proposal.[23] The Post Office Department awarded the contract to the Church’s company in early October, although the same snowstorms that stranded the Willie and Martin handcart companies in Wyoming delayed the news. Brigham Young was now acting governor of Utah Territory, ex officio superintendent of Indian affairs, President of the Church, and head of the express and carrying company. Federal officials would have considered control of the federal mail contract an alarming conflict of interest, especially when added to reports by Magraw and federal officials such as Judge Drummond who had fled in panic from Utah Territory (discussed below). These complaints led Utah Territory to the brink of war.

A bitterly disappointed Magraw wrote to President Franklin Pierce on 3 October 1856 about “personal annoyances in the Mormon country,” arguing that Utah Territory had “no vestige of law and order” and that the “so-styled ecclesiastical organization” was “despotic, dangerous and damnable.”[24] Three days later John Hockaday’s brother Isaac complained to Pierce that “the entire Territory of Utah is under the complete control of a most lawless set of knaves and assassins who trample under foot the rights of those not belonging to their so called religious community.”[25] The letters built on and amplified antagonistic sentiments of the time.[26] That same year the Republican Party had adopted a presidential platform plank calling for eradication in the territories of “those twin relics of barbarism—Polygamy, and Slavery.”[27] Uncle Sam did not want to touch slavery in the States but was preparing to poke the beehive from the relatively safe distance of Washington.[28]

Because snow at Devil’s Gate had delayed the contract, Kimball did not sign it by the deadline, creating uncertainty from the beginning. Kimball finally learned by letter via Los Angeles on 6 January 1857 that he had been awarded the contract. He launched the service on 2 February, even though the actual contract still had not arrived. He carried the mail on 8 February, arriving in Independence twenty-six days later. The return to Salt Lake City spanned twenty-eight days. John Murdock and William Hickman would manage the portion from Independence to Fort Laramie, and Porter Rockwell would manage from Fort Laramie to Salt Lake City.[29]

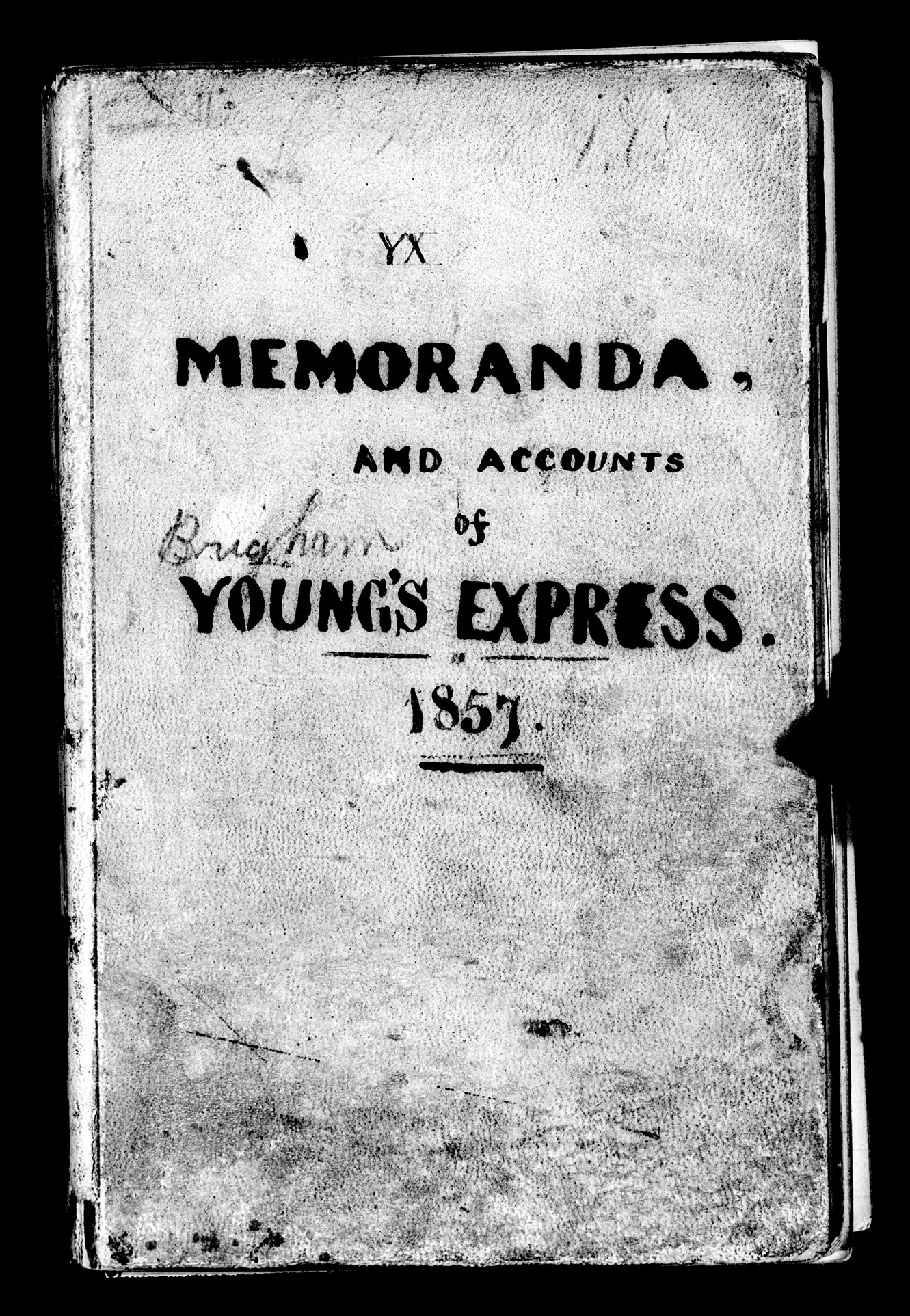

Young paid Kimball $1,000 for the contract and rushed to form the Brigham Young Express and Carrying Company. To lower his profile in the company, Young retained Kimball as a “front” and muted his own ownership role by calling it the “Y. X. Company.” Young did not disclose to the Post Office Department his religious motivation to promote immigration.

Young planned four parts of the express and carrying company: a “swift pony express” to deliver mail, stagecoaches to transport emigrants quickly across the plains, wagons to deliver freight, and way stations to outfit and feed western- and eastern-bound emigrants.[30]

The “swift pony express” would travel during the winter and summer in less than twenty days between Independence and Salt Lake City. This was a major innovation years ahead of its time—three years before the government-sanctioned Pony Express of the same name.[31]

YX Memoranda, and Accounts of Brigham Young’s Express, 1857. Brigham Young office files, Brigham Young Express and Carrying Company Files, 1857–1860, CR 1234 1, box 83, folder 6, image 2. Church History Library.

YX Memoranda, and Accounts of Brigham Young’s Express, 1857. Brigham Young office files, Brigham Young Express and Carrying Company Files, 1857–1860, CR 1234 1, box 83, folder 6, image 2. Church History Library.

Young said a stagecoach service would invite “Priests, Editors, and the great ones of the earth who are so much concerned about the affairs of Utah” to travel to the territory to “learn the truth relative to the Latter-day Saints and their institutions.”[32] Hence, the company would satisfy a missionary motivation as well.

The freight business would reduce the cost of shipping to 12½ cents per pound; they hoped to avoid the current “excessive charges” because the Latter-day Saints were “working so hard for a bare pittance and spending their strength to enrich a set of ostentatious, proud and epicurean gentiles.”[33] Brigham Young was a lifelong advocate of home industry over competing enterprises.

Thus, the Church-owned company began building or improving the existing way stations, creating a safe emigrant trail with stations strategically placed every fifty miles, about as far as a mule team could pull in a day, to help the handcart pioneers. Under President Young’s direction, the Church began to expend large amounts of scarce capital to build and maintain those way stations and farming settlements, buy teams and wagons, and buy supplies and equipment and seed to plant crops to feed the emigrant companies. To provide supplies, the Church immediately borrowed $12,000.[34] The ledger of the Y. X. Company is filled with hundreds of pages of purchases of clothing, equipment, food, horses, livestock, and seed.

As a matter of duty, members were asked to donate labor, livestock, and equipment with the expectation of sharing some of the dividends resulting from the enterprise. Between February and July 1857, members donated a total of $107,000 worth of livestock, equipment, and supplies—in today’s dollars, more than $3 million.[35] These donations came from members who were both unselfishly promoting safe emigrant travel for their fellow members and seeking money from the mail express, the freight business, and overland traffic to California for their own interests.

Participating members were told not to ask, “How much shall I have for my labor?” Nor should they ask for immediate compensation for donated “animals, wagons, flour, and other property.”[36] The company ledger lists about four hundred individual donors. For example, John Bagley donated a $75 horse, Joseph Horne donated $50 worth of “tithing office pay,” Elizabeth Foss donated a $6 quilt, Marriner Merrill donated a $3.50 wagon cover, and Laura Kimball donated a pair of socks for some needy driver![37] Brigham Young reported on 4 July that the express company planned to continue shipping animals “until we get the road stocked with 1,000 horses and mules.”[38]

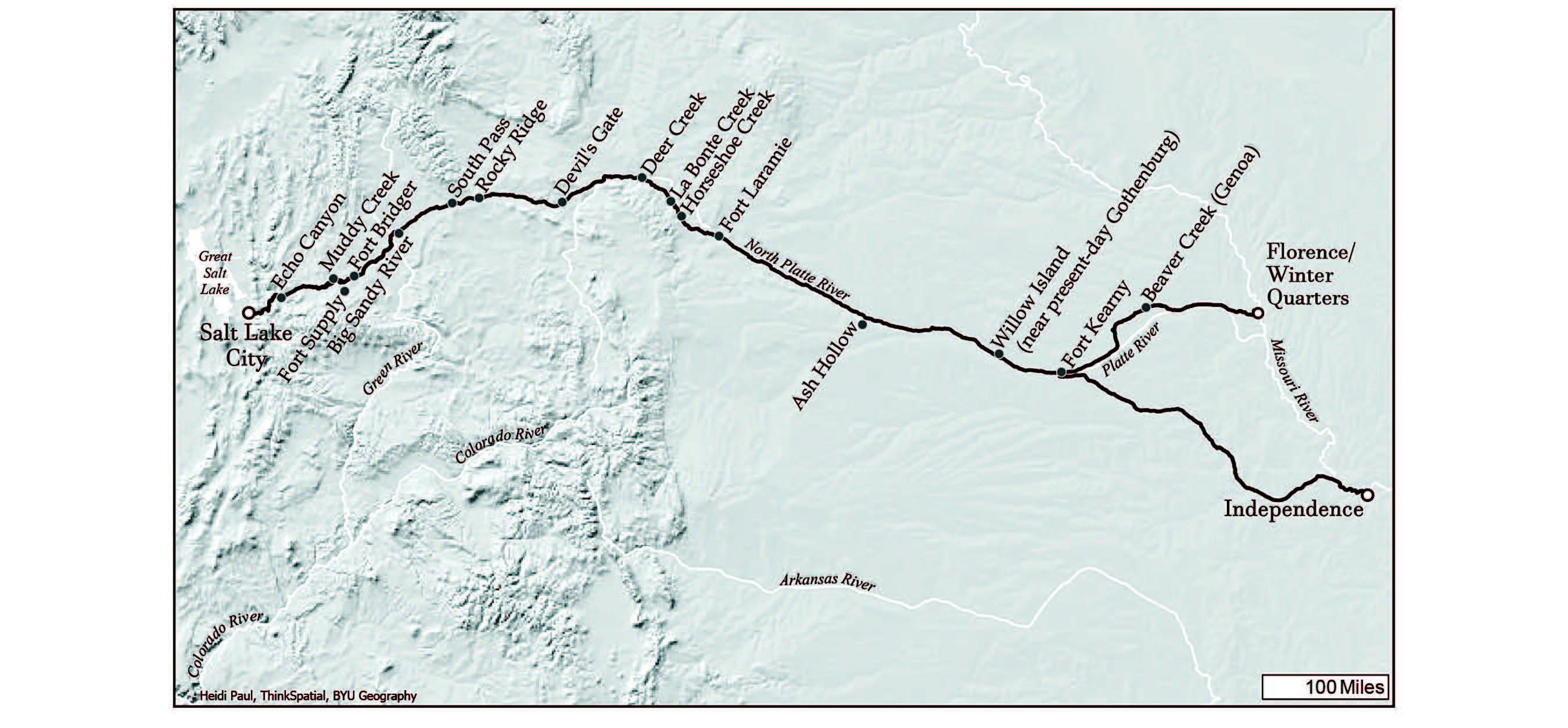

Sites used by the Brigham Young Express and Carrying Company, 1857. Heidi Paul, ThinkSpatial, Brigham Young University.

Sites used by the Brigham Young Express and Carrying Company, 1857. Heidi Paul, ThinkSpatial, Brigham Young University.

The company initially developed existing stations at Fort Bridger and Fort Supply. They then started new stations near the headwaters of the Sweetwater River, Rocky Ridge, and Devil’s Gate. Eastward of the Continental Divide, they established stations at Deer Creek (west of today’s Glenrock, Wyoming),[39] La Bonte Creek, Horseshoe Creek (thirty miles west of Fort Laramie), and other locations (see map above).[40] For example, Nathaniel V. Jones oversaw creation of the first permanent station at Deer Creek. By July, Church members had erected a corral 150 feet square, stocked it with seventy-six mules and horses, and had nearly completed a stockade and stockyard.[41] Indian agent Thomas Twiss wrote on 13 July that Latter-day Saints had driven Sioux Indians from Deer Creek and planned to “monopolize all the trade with the Indians.”[42]

On the far eastern side of the trail, settlers traveled a hundred miles from the Winter Quarters–Council Bluffs area to establish a substantial settlement at Beaver Creek (today’s Genoa) in Nebraska, arriving on 11 May. They planted corn, potatoes, wheat, and vegetables. They built a sawmill and a brickyard and had a community of 160 people. (Because the Church and its agents never acquired title to the lands on which relay stations were built, this ambiguity raised troubling issues with both the tribal bands and the federal government. Most of these stations would later be adopted and maintained by the Pony Express.)

Acting in his dual role as Church President and president of the Y. X. Company, Young took time in the Church’s general conference of 6–7 April 1857 to promote the company as a missionary-run business enterprise. That April, Church leaders called nineteen missionaries in April to serve in the company: John D. Park, Alexander H. Hill, James Dimond, James B. Park, Ira N. Hinckley, John Vance Jr., James Seward, Henry M. McArthur, John S. Houtz, Samuel Green, George A. Williams, William Showel, Llewellyn Hursey, Henry Wilson, Orrin S. Lee, Alonzo Clark Merrill, Reuben Gates, George Davidson, and John P. Wimmer.[43] Young enthusiastically reported the progress of the company:

That Company has now commenced its business operations. Three companies [of up to 100 men each] have already left this city, and the particular object in view is to establish places where our brethren can stop and rest, recruit and refresh themselves until they can continue their journey and arrive in this valley. Our main object is to make settlements and raise grain at suitable points and convenient distances, where we can prepare resting places for the Saints. The last season’s immigration [of 1856] . . . has prompted us materially to this action. If we had had settlements . . . where people can raise grain, our last year’s belated immigration might have had habitations, food, and other conveniences for comfortably tarrying through the winter, and thus saved this community a vast expense.[44]

Hon. James Buchanan, photograph by Mathew Brady, Brady National Photographic Art Gallery, US National Archives and Records Administration.

Hon. James Buchanan, photograph by Mathew Brady, Brady National Photographic Art Gallery, US National Archives and Records Administration.

Of course, the term vast expense included the rescue of the handcart and wagon companies—some of the worst tragedies on the Overland Trail. It is noteworthy that President Young mentioned the financial cost but did not mention the loss of lives—a fresh and painful memory and the cause of some finger-pointing as to why the travel was so late in the season, leading to the loss of lives. The Church indeed had strong motivations to provide good communication and safe, speedy travel.

The mostly volunteer company was poised to become a major force for safely transporting mail and people across the plains. “Ironically enough,” concluded Leonard J. Arrington, “the activities of the Brigham Young Express and Carrying Company in carrying out its mail contract and in performing other economic chores for the Church figured prominently among the factors” leading to war.[45]

End of the Company, Start of the War

The express company died in infancy as friends and foes alike stirred a hornets’ nest. James Buchanan, the president-elect, made his way to the White House on a train furnished by Robert Magraw, brother of the disgruntled mail carrier.[46] On 6 January 1857, Utah legislators approved provocative memorials to Washington, arguing for rejection of federal officials who did not reflect local values.[47] As historian Brent M. Rogers has argued, “The question of sovereignty—or determining who possessed and could exercise governing, legal, social, and even cultural power—is at the crux of Utah Territory’s history.”[48]

The memorials arrived in Washington on 17 March, the same day the New York Herald called for “immediate and decisive action” on Utah and Kansas. Two days later, Secretary of the Interior Jacob Thompson called the memorials “a declaration of war.”[49] Thompson’s martial mood was likely sparked by a letter received the same day from William W. Drummond, associate justice of the Utah Territory Supreme Court, a married man who flaunted his mistress in public while criticizing the practice of polygamy. Drummond tried to diminish Latter-day Saint influence by reducing the power of Utah’s county probate courts. After disagreeing with local officials, he complained to Washington, then fled to California and later New Orleans, where he resigned with a letter alleging that Church leaders had destroyed territorial Supreme Court papers and murdered government officials.[50] Drummond called for a replacement as governor “with a sufficient military aid” to see the job through.[51] On 20 March, Chief Justice John F. Kinney hand-delivered to federal authorities a letter calling for military intervention along with a recommendation by Utah surveyor general David H. Burr for “a small Military force” to enforce laws.[52]

April proved to be a month of decision. John M. Bernhisel, Utah’s territorial delegate in the US House of Representatives, wrote to Governor Young that “the clouds are dark and lowering, . . . that the Government intended to put [polygamy] down,” and that federal troops might be sent to overturn the perceived rebellion.[53] The Washington National Intelligencer reprinted a long letter on 21 April asking for a federal force of five thousand to deal with Brigham Young. It was signed by “Verastus” (likely Magraw), described as “a respectable citizen, who lately spent twelve months in the Salt Lake Valley, engaged in business connected with the transit of the mails throughout the territory.”[54] Two days later, Buchanan appointed Magraw superintendent of the newly approved Pacific Wagon Road from Fort Kearny to South Pass to Honey Lake; thus Magraw would triumphantly return to Utah Territory.[55]

At the end of the month, Robert Tyler, one of Buchanan’s closest advisers and the son of President John Tyler, recommended a plan to help the nation “forget Kansas” and to replace “Negro-Mania” with “the almost universal excitements of an Anti-Mormon Crusade.”[56] Meanwhile, attorney John Hockaday sought an audience with President Buchanan, likely about Utah Territory—later turning a tidy profit for Hockaday when he regained the mail route.

In May, while Congress was adjourned, Buchanan ordered 2,500 US soldiers to escort and install a new territorial governor (Alfred Cumming of Georgia was later appointed),[57] and the newly appointed chief justice of Utah’s territorial Supreme Court, Delana R. Eckels.[58] To aid the army, but without authorization, the bitter and drunken Magraw loaned fifteen thousand dollars’ worth of wagons, mules, and employees to the new Utah Expedition—a personal abuse of authority that led to his dismissal from the road contract in 1857.[59] But the fires had been lit.

Just after the president sent US troops to Utah Territory, the Post Office Department annulled the mail contract on 10 June.[60] Senator Stephen A. Douglas argued on 12 June that “when the authentic evidence shall arrive,” Congress would see fit to “apply the knife and cut out this loathsome and disgusting ulcer.”[61]

Mail conductors Abraham O. Smoot and Nicholas Groesbeck arrived in Independence about 1 July and were denied the westbound mail. Smoot had previously encountered heavy westbound freight trains and concluded that they might be part of US Army supplies for troops to replace Young.[62] At the mail stations, Smoot asked the men to dismantle the stations and retreat to Salt Lake City. Thus began a period of a severely disrupted communication, which greatly exacerbated the anxiety, rumors, and reactions across the United States and even influenced Russia and Great Britain to make changes. Historian William P. MacKinnon notes, “Russian tsar Alexander II . . . reacted to rumors of a Mormon rush to the Pacific Coast by trying to sell Alaska; and Queen Victoria . . . responded to speculation about the same threat by creating the crown colony of British Columbia while sending the Royal Navy to protect the Kingdom of Hawaii.”[63]

On 24 July (ten years after a vanguard company of pioneers entered the Salt Lake Valley), Abraham Smoot, Porter Rockwell, and Judson Stoddard dramatically shared alarming news with people gathered for a pioneer celebration in Big Cottonwood Canyon that the US Army was marching on Utah Territory and that it was reportedly commanded by William S. Harney, a general with a reputation for brutality.[64] Governor Young reported, “The Utah mail contract had been taken from us—on the pretext of the unsettled state of things in this Territory.”[65]

Governor Young activated the territorial militia to defend Utah’s borders and asked Lieutenant General Daniel H. Wells to draft a declaration of martial law on 29 August.[66] The territorial militia equipped itself with express company supplies, and the Church public works system that had previously outfitted the express company began manufacturing “guns, bullets, cannon balls, and canister shot.”[67]

Young proclaimed martial law on 15 September, four days after southern Utah members of the Nauvoo Legion, assisted by some Paiutes, killed more than 120 members of the Baker-Fancher emigration party in the Mountain Meadows Massacre.[68]

In the western part of Utah Territory (in today’s Wyoming), Wells ordered the Legion to “take no life, but destroy their trains and stampede or drive away their animals at every opportunity.”[69] The Legion burned the express company’s way stations at Fort Bridger and Fort Supply. In early October, Lot Smith burned three contractor wagon trains that were hauling tons of food and supplies for the army.[70] The following week, he ran off seven hundred head of federally owned cattle. That number increased to a thousand and then two thousand. These actions escalated to the point that both Col. Albert Sidney Johnston, incoming commander of the Utah Expedition, and Brigham Young authorized the use of deadly force.[71]

Colonel Johnston arrived on 3 November, escorting Governor Cumming and Chief Justice Eckels. The army then established temporary winter quarters at Camp Scott, about two miles southwest of Fort Bridger. Utah troops continued to watch the army from nearby Bridger Butte. Meanwhile, Governor Young was gathering in members from the outlying colonies and missions (Hawaii, San Francisco, San Bernardino, and Carson Valley).

Col. Thomas L. Kane rode into the frustrated US Army camp on 12 March 1858 as an unofficial conflict mediator who favored the Saints.[72] Soldiers suspected Kane was a Latter-day Saint, and as Capt. Jesse A. Gove reported, his men “want[ed] to hang him.”[73] Kane convinced Governor Cumming to ride unescorted by the military into the Salt Lake Valley, where he was wined and dined by Brigham Young.

At the end of May, two official peace commissioners (Benjamin McCulloch and Lazarus W. Powell) arrived with a proclamation of general pardon if members of Utah Territory would proclaim loyalty to federal authority. Negotiations elicited an indignant reaffirmation of loyalty. With the threat of all-out war over, the army marched through the Salt Lake Valley, eventually establishing a military outpost called Camp Floyd, southwest of Salt Lake City, to keep a watchful eye over the territory.

Conclusion

After months of campaigning during the Utah War, Magraw’s former partner John Hockaday secured the lucrative mail contract—now worth $190,000—and rebuilt dismantled way stations.[74] This was a bitter pill for the Latter-day Saints to swallow.

Ironically, Hockaday’s stations were soon taken over by the Pony Express in 1860, then largely outmoded in 1861 by the transcontinental telegraph system—connected, of all places, at the crossroads of the West: Salt Lake City. In an inaugural telegram delivered after the outbreak of the American Civil War, Brigham Young diplomatically affirmed, “Utah has not seceded, but is firm for the constitution and laws of our once happy country, and is warmly interested in such useful enterprises as the one so far completed.”[75] Meanwhile, Alfred Cumming and Albert Sidney Johnston had departed Utah Territory.[76]

So how do we count the costs of this costly mail-and-war episode? Arrington concludes that “it was one of the few occasions in American history in which raw federal power, rather than the voluntary process of reason, was depended upon to force conformity of social viewpoint and political submission.” He then estimated the cost at $15 million ($452 million in today’s dollars).[77] It also led to much avoidable death and suffering when Latter-day Saints evacuated settlements in northern Utah in what became known as the Move South.

On the Latter-day Saint side, when Brigham Young complained about abuse at the hands of the US government, he viewed the termination of his express company as a costly blow. Historian Leonard J. Arrington said that in donations, capital improvements, and wages, the Church had nearly exhausted its resources by spending nearly $200,000 ($6 million in today’s dollars).[78] The opportunity cost from lost transportation revenues would be enormous. Factoring in the losses sustained by the disrupted colonies, missions, and the Move South makes the cost a truly staggering sum.

In conclusion, the mail-and-war episode sowed seeds of mutual distrust. Latter-day Saints in Utah increasingly resisted perceived incursions into their local industry and become even more resistant to outside influences. Outside entrepreneurs would struggle to find equal footing in the Utah marketplace for at least another four decades.

Eventually, however, passenger services fulfilled Brigham Young’s dream of transporting “Priests, Editors, and the great ones of the earth” to tour Utah. At the end of the American Civil War in 1865, Samuel Bowles III, editor of the Springfield Republican, took time during his cross-country trip to report about the Latter-day Saints. “The result of the whole experience,” he wrote, “has been to increase my appreciation of the value of their material progress and development to the nation; to evoke congratulations to them and to the country for the wealth they have created and the order, frugality, morality and industry that have been organized in this remote part in our Continent.”[79] However, he criticized the practice of polygamy and predicted that “the click of the telegraph and the roll of the overland stages are its death-rattle now; the first whistle of the locomotive will sound its requiem; and the pick-ax of the miner will dig its grave.”[80] The telegraph and the train did not terminate the practice of polygamy, which continued another thirty-plus years, but they did dramatically deliver—and improve upon—the goals of Brigham Young’s express company: to provide fast and reliable communication and transportation across America.

Notes

[1] For more about the Council of Fifty, see Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016); and Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith, The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017). The context of religious persecution, vigilantism, and indifference from state and federal officials helps explain Latter-day Saint attitudes and sermons about the United States during this period.

[2] Leonard J. Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985).

[3] Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 23 July 1847, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[4] Minutes of a Special Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints held in the Bowery, on the Temple Block, in Great Salt Lake City, 22 August 1847, Church History Library.

[5] Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958), 162.

[6] Henry W. Bigler, Bigler’s Chronicle of the West, ed. Erwin G. Gudde (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1962), 88.

[7] Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, 2 February 1848, http://

[8] Announcements of this event appeared in such papers as the New Orleans Times-Picayune of 5 April 1849.

[9] Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 28 February 1849; Wilford Woodruff to Orson Pratt, Journal History, 1 March 1849.

[10] “Salt Lake Postage,” Frontier Guardian (Kanesville, IA), 7 March 1849.

[11] Steven C. Walske and Richard C. Frajola, Mails of the Westward Expansion, 1803 to 1861 (San Francisco: Western Cover Society, 2015), 121.

[12] Walske and Frajola, Mails of the Westward Expansion, 121. In April 1851, George Chorpenning Jr. and Absalom Woodward won the contract for monthly transport between Sacramento and Salt Lake City. Both routes employed Latter-day Saints.

[13] US House, Executive Documents, 34th Congress, First Session, No. 122, 335 (mail contracts).

[14] US Statutes at Large, vol. 10, 634.

[15] Deseret News, 8 August 1854.

[16] William P. MacKinnon, “The Buchanan Spoils System and the Utah Expedition: Careers of W. M. F. Magraw and John M. Hockaday,” Utah Historical Quarterly 31 (Spring 1963): 133.

[17] Deseret News, 11 June 1856.

[18] Walske and Frajola, Mails of the Westward Expansion, 121.

[19] Deseret News, 11 June 1856, 4.

[20] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 174.

[21] LeRoy R. Hafen, The Overland Mail, 1849–1869: Promoter of Settlements, Precursor of Railroads (Lawrence, MA: Quarterman Publications, 1976), 61; LeRoy R. Hafen and Ann W. Hafen, Handcarts to Zion: The Story of a Unique Western Migration, 1856–1860 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1960), 150.

[22] Hiram S. Kimball was born in Vermont and baptized in 1843. He came to Utah Territory in 1850. He was the husband of Sarah Granger Kimball, who was an early leader in the Relief Society and an advocate for women’s rights. He was called on a mission to the Sandwich Islands in 1863 but died en route. http://

[23] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 164.

[24] W. M. F. Magraw to Mr. President [Franklin Pierce], 3 October 1856, in The Utah Expedition. Message from the President of the United States, 35th Congress, House of Representatives, 1st session, Ex. Doc. 71 (Washington, DC: James B. Steedman, 1858), 2–3.

[25] Isaac Hockaday to Franklin Pierce, 6 October 1856, Miscellaneous Letters of Dept. of State, National Archives.

[26] “Challenged by the House to prove that a Mormon rebellion had in fact existed in the spring of 1857, Buchanan ordered the members of his cabinet to search their files for relevant material. On February 3, 1858, Secretary of State Lewis Cass reported back to the President that ‘. . . the only document on record or on file in this department, . . . is the letter of Mr. W. M. F. Magraw to the President, of the 3d of October last.” MacKinnon, “Buchanan Spoils System,” 130. Buchanan failed to present Isaac Hockaday’s letter to the House. MacKinnon, “Buchanan Spoils System,” 136.

[27] Republican Party Platform of 1856, http://

[28] 1856 Democratic Party Platform, http://

[29] “By Ocean or by Land: Roots of the Pony Express,” chapter 1 of Pony Express: Historic Resource Guide, https://

[30] Brigham Young office files, Brigham Young Express and Carrying Company Files, 1857–1860, CR 1234 1, box 83, folder 6, Church History Library.

[31] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 164.

[32] Brigham Young to Orson Pratt, Millennial Star, 1 March 1857, 363.

[33] Young to Pratt, 1 March 1857, 410.

[34] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 167.

[35] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 167. Conversions to modern dollars are made by using Samuel H. Williamson, “Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount—1774 to Present,” www.measuringworth.com/

[36] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 166.

[37] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 167.

[38] Brigham Young to George Q. Cannon, 4 July 1857.

[39] “From 1857 to 1861, the post also was a trading center for the nearby Upper Platte Indian Agency, located about three and a half miles upstream along Deer Creek.” http://

[40] “Mormon Emigrants: 1848–1868—Y.X. Company,” http://

[41] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 168.

[42] Thomas S. Twiss to J. W. Denver, 13 July 1857, in The Utah Expedition: Message from the President of the United States (35th Congress, 1st Session, Executive Doc. No. 71), 192.

[43] Ralph L. McBride, “Utah Mail Service before the Coming of the Railroad, 1869” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1957), 59–60.

[44] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 4:302 (6 April 1857).

[45] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 172. In an email to me on 26 January 2019, historian William P. MacKinnon commented, “I think Arrington substantially overstated the case for the formation of the Y. X. Carrying Company as a ‘cause’ of the Utah War.” That opinion has validity. Clearly, federal concerns about Brigham Young’s accumulation of power led to cancellation of the mail route, which was linked to the beginning of the Utah War.

[46] William P. MacKinnon, ed., At Sword’s Point, Part 1: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858 (Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark, 2008), 58.

[47] MacKinnon, At Sword’s Point, Part 1, 62–63, 67–73.

[48] Brent M. Rogers, Unpopular Sovereignty: Mormons and the Federal Management of Early Utah Territory (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2017), 5.

[49] Jacob Thompson, as quoted in MacKinnon, At Sword’s Point, Part 1, 102.

[50] “Utah and Its Troubles,” dated 19 March 1857, New York Herald, 20 March 1857, 4–5, as cited in At Sword’s Point, Part 1, 102–3.

[51] “Judge Drummond’s Letter of Resignation,” in The Utah Expedition, 1857–1858: A Documentary Account of the United States Military Movement under Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, and the Resistance by Brigham Young and the Mormon Nauvoo Legion, ed. LeRoy R. Hafen and Ann W. Hafen (Glendale, CA: Arthur H. Clark, 1982), 363–66, emphasis in original.

[52] John F. Kinney to James Buchanan, 1 August 1857, Office of the Attorney General, Correspondence from the President, Letters Received (RG 60), National Archives; the Burr–Black letter is filed therewith.

[53] John M. Bernhisel to Brigham Young, 2 April 1857, Church History Library, as cited in At Sword’s Point, Part 1, 106–7.

[54] MacKinnon, “Buchanan Spoils System,” 136.

[55] MacKinnon, “Buchanan’s Spoil System,” 137.

[56] Robert Tyler to James Buchanan, 27 April 1857, as cited in David A. Williams, “President Buchanan Receives a Proposal for an Anti-Mormon Crusade, 1857,” BYU Studies 14, no. 1 (1974): 104–5.

[57] A former mayor of Augusta, Georgia, Cumming served as Utah’s territorial governor from 1858 to 1861.

[58] Eckels served from 1857 to 1860 and was both preceded and succeeded by John F. Kinney.

[59] MacKinnon, “Buchanan’s Spoil System,” 140–41, 143.

[60] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 169.

[61] Remarks of the Hon. Stephen A. Douglas on Kansas, Utah, and the Dred Scott Decision, Delivered at Springville, Illinois, June 12, 1857 (Chicago: Daily Times Book and Job Office, 1857), 12–13.

[62] Quentin Thomas Wells, Defender: The Life of Daniel H. Wells (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2016), 176.

[63] MacKinnon, At Sword’s Point, Part 2, 37.

[64] Richard Whitehead Young, “The Nauvoo Legion,” Contributor 9 (August 1888): 362. See also MacKinnon, At Sword’s Point, Part 1, 354. General Harney did not actually lead the Utah Expedition to Utah. He was replaced by Col. Albert Sidney Johnston.

[65] Everett L. Cooley, ed., Diary of Brigham Young, 1857 (Salt Lake City: Tanner Trust Fund and University of Utah Library, 1980), entry for 24 July 1857, 49.

[66] Although scholars once debated whether Governor Young issued two martial law proclamations—5 August and 15 September—scholars now think the purported August document was an uncirculated draft. See Will Bagley, “Like Any Other Place, Utah History Contains Shares of Mysteries” and “If the Document Is Authentic, How Can We Explain Weird Dates?,” Salt Lake Tribune, 3 and 10 August 2003; MacKinnon, At Sword’s Point, Part 1, 285–86n14; Ronald W. Walker, Richard E. Turley Jr., and Glen M. Leonard, Massacre at Mountain Meadows: An American Tragedy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 358n116.

[67] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 177.

[68] The militia first claimed that Paiutes killed the emigrants, but later trials proved otherwise. Governor Young apparently did not order the massacre, but his violent rhetoric influenced the territorial militia. John G. Turner, Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2012), 280.

[69] Orders of Daniel H. Wells as quoted in Third District Court (Territorial), Case Files, People v. Young, Series 9802, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City.

[70] “Narrative of Lot Smith,” in Mormon Resistance: A Documentary Account of the Utah Expedition, 1857–1858, ed. LeRoy R. Hafen and Ann W. Hafen (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1958), 220–28.

[71] David L. Bigler and Will Bagley, The Mormon Rebellion: America’s First Civil War, 1857–1858 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), 218, 222.

[72] For Kane’s friendship with the Latter-day Saints and motivations behind this unofficial peace mission, see Matthew J. Grow, “Liberty to the Downtrodden”: Thomas L. Kane, Romantic Reformer (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), and David J. Whittaker, ed., Colonel Thomas L. Kane and the Mormons, 1846–1883 (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2009).

[73] MacKinnon, At Sword’s Point, Part 2, 283.

[74] “News Items,” Deseret News, 2 June 1858, 3.

[75] “The Completion of the Telegraph,” Deseret News, 23 October 1861, 5.

[76] Johnston would die at the Battle of Shiloh, becoming the highest-ranking officer killed in the Civil War.

[77] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 172.

[78] Leonard J. Arrington, Mormon Finance and the Utah War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958), 220. The relative value is $6,020,000.

[79] Samuel Bowles, Across the Continent: A Summer’s Journey to the Rocky Mountains, the Mormons, and the Pacific States, with Speaker Colfax (Springfield, MA: Samuel Bowles, 1865), 106.

[80] Bowles, Across the Continent, 108.