The Last Best West

The Politics of Cooperation Among Latter-day Saints in Southern Alberta

Brooke Kathleen Brassard

Brooke Kathleen Brassard, "The Last Best West: The Politics of Cooperation Among Latter-day Saints in Southern Alberta," in Business and Religion: The Intersection of Faith and Finance, ed. Matthew G. Godfrey and Michael Hubbard MacKay (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 113–150.

Before members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints accepted their permanency in the District of Alberta (later, Province of Alberta), Canada, they remained tied to the ways of nineteenth-century Utah and settled new communities following the farm village plan. They also developed businesses that stressed community benefits. For the nineteenth-century Church of Jesus Christ, “the ideal society was theocratic . . . [with an emphasis on] group consciousness and activity, rather than on the individual, . . . and each person working for the good of the whole.”[1] Latter-day Saints rejected the highly individualistic economics of nineteenth-century America, underscored group interests, and experimented with economic systems until the federal government and American society forced them to cooperate with the nation’s social, political, and economic expectations.[2] Cultural geographer Ethan R. Yorgason explained in his chapter on “privatizing Mormon communitarianism” that in the early twentieth century, private wealth and individual self-sufficiency assumed priority over the welfare of the community, and around the time of the First World War, Utahns were no longer regionally independent, but national participants.[3]

In southern Alberta, the Mormon Farm Village (a settlement plan where Latter-day Saints built homes in villages or towns with wide streets and large yards, separate from the farms on homesteads) and cooperative interests—such as sugar beets and the large, corporate Cochrane Ranch (Alberta’s first large-scale cattle ranch)—were products of strategies, intentional or not, that kept the Saints isolated and self-reliant. Their willingness to give up some of this self-sufficiency and reach outside their community with more long-term financial plans and humanitarian goals required interaction and cooperation with those not of their faith and enabled them to take another step toward integration into Canadian society. While pockets of radical, nondominant political groups (for example, the Socialist Party of America) existed in Utah, similar “radicals” in the province of Alberta achieved such levels of success and support that they dominated the provincial government for forty years (from 1921 to 1971). Utahns and American Latter-day Saints left their radical past behind and became more “American.” Alberta, with its radical, nonpartisan, populist parties, incubated the values and ideals such as group interests and cooperation that Latter-day Saints south of the border had to abandon in order to become more “American.”

Political participation signaled at least some desire on the part of the Latter-day Saints to contribute to their new home and other people. They successfully entered politics at all levels: municipal, provincial, and federal. The ideologies central to three significant political parties in Alberta from the early twentieth century to the end of the 1940s demonstrated how Canadian Saints, as they integrated into Canadian society, created barriers between themselves and their American associates. As they became more involved in Canadian politics, many Saints joined organizations in Alberta such as the United Farmers of Alberta, the Social Credit Party, and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. These distinctly Canadian associations promoted platforms that criticized capitalism and justified cooperation, foreshadowing Canada’s trend toward both Keynesian liberalism and, later, neoliberalism.[4] Cooperation and communal ideologies caused Canadian Latter-day Saints to draw closer to their Canadian neighbors and disconnect from the American Saints.

When the Church faced severe pressure from the American government, Church President John Taylor looked back to his time in Canada and suggested that the Church search Canadian territory for a place where Latter-day Saints might find peace from prosecution for their practice of plural marriage.[5] Following the efforts of President Charles Ora Card (1839–1906) of the Cache Stake, Latter-day Saints began settling in the District of Alberta in the North-West Territories in 1887. Many of these settlers were involved in nonmonogamous relationships but tended to bring only one spouse to the new Canadian communities. The federal government divided the prairies into townships (thirty-six-square-mile sections) and, after reserving land for the Canadian Pacific Railway, British male subjects and settlers received homesteads of 160 acres. In Will the Real Alberta Please Stand Up?, author Geo Takach stated that “the notions of starting afresh on the frontier and struggling to survive unleashed a bias against entrenched power, inherited privilege and the haughty attitudes that went with them.”[6] This bias manifested itself in numerous ways, such as the creation of lobby groups and political parties looking to defend the people of Alberta against the power and privilege associated with Ottawa and central Canada.

In his introduction to the Mardons’ book on the Mormon contribution to politics in Alberta, educational sociologist Brigham Y. Card (1914–2006) argued that “when a person stands for nomination for the Alberta Legislature or the House of Commons, it is a signal. First, that the person is a Canadian citizen, and second, that the person is willing to serve the local and larger good of the province and country.”[7] Political participation and shared ideological support for political parties by Latter-day Saints signaled their integration into Canadian society. This chapter examines provincial and federal levels of government and the roles of Latter-day Saints as they transitioned from outsiders to active citizens. Introducing the section on economics and government, editors of The Mormon Presence in Canada claimed,

Although Alberta Mormons have not been innovators of economic or political ideas, they have regularly adapted ideas that appear to offer solutions to the problems facing a hinterland economy. Mormons in Alberta have in the past been able to reconcile their religious beliefs with political ideas ranging from the moderate left to the extreme right.[8]

An examination of the various political parties in Alberta and the involvement of Latter-day Saints provides insight into the growing distance from the American membership and the increasing attachment to their new homeland.

United Farmers of Alberta

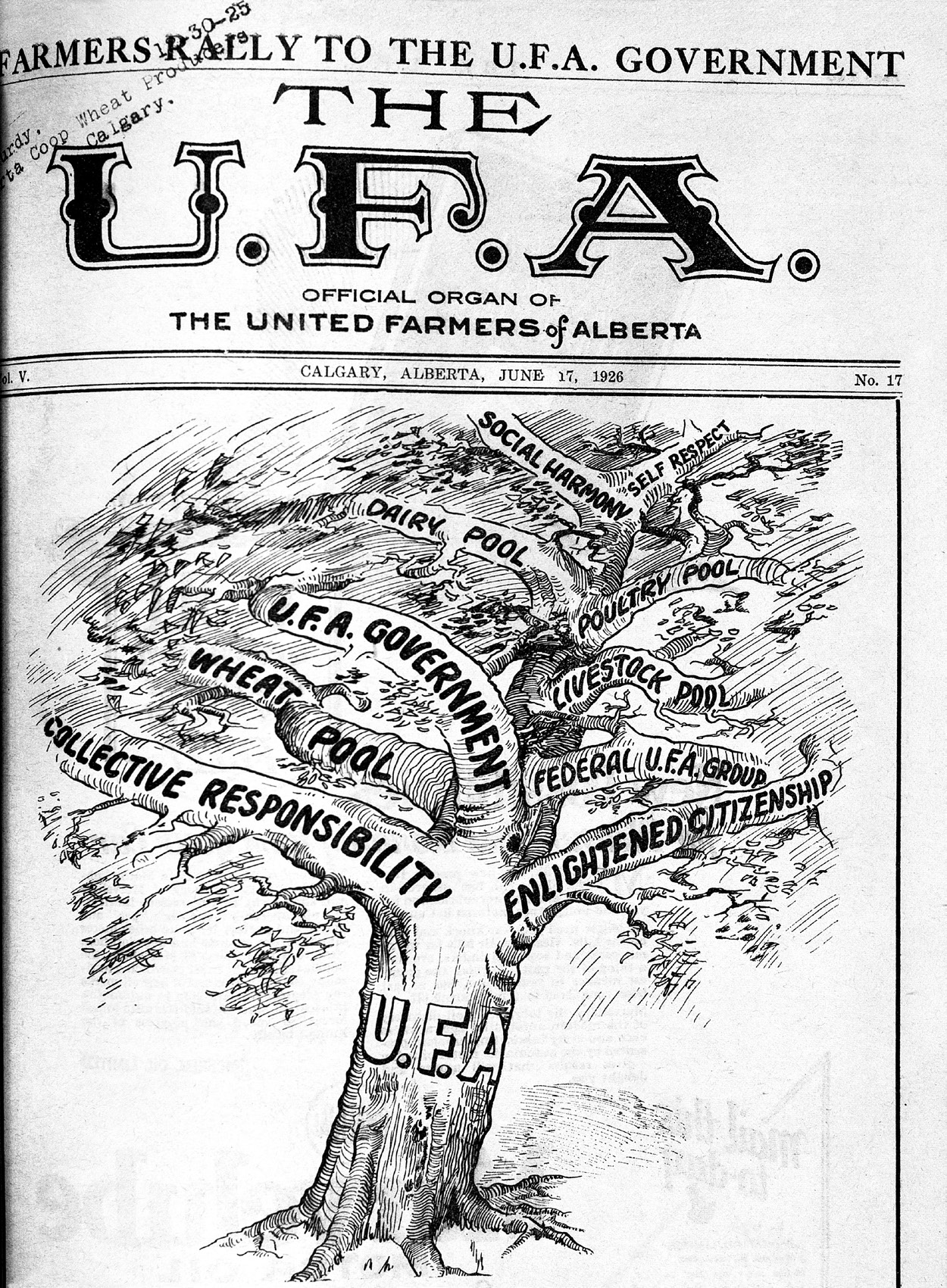

Front page of the U.F.A. newspaper, 17 June 1926. Glenbow Archives NA-789-94.

Front page of the U.F.A. newspaper, 17 June 1926. Glenbow Archives NA-789-94.

Political scientist Clark Banack described the United Farmers of Alberta (UFA) as “an extensive network of highly participatory ‘locals,’ community-level groupings of farmers that sought to protect their economic interests by lobbying government and by pooling both their purchasing power and their agricultural produce in an effort to leverage their way to better financial outcomes.”[9] Prior to the 1920s, before the farmers of Alberta turned their lobby group into a political party, they evolved from a larger North American agrarian movement where farmers tried to protect themselves against the impact of the growing commercial-capitalist economy. Farmers developed “a sense of opposition to corporations that denied them their land’s wealth, which prompted them to establish the early farm associations for protection.”[10] Although American populism never officially gained a foothold in Canada, it influenced the Alberta farmers’ movement with the promotion of farmer cooperation, establishment of agrarian ideals in farm culture, advancement of equal rights, producerism, and antimonopolism. If one mixes these ideals with British cooperative, labour, and socialist thought, the situation motivating the organization of farmers in the province of Alberta becomes clear.

Struggling against the dominance of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and the abuse from grain companies, farmers formed the Territorial Grain Growers’ Association (TGGA) in 1902. In 1905, when Alberta became a province, the Alberta branch of the TGGA became the Alberta Farmers’ Association (AFA). The AFA aimed to forward the farmers’ interests in grain and livestock, to encourage superior production and breeding, to obtain by united effort profitable and equitable prices for farm produce, and to watch legislation relating to the farmers’ welfare (particularly that affecting the marketing and transportation of farm produce).[11] Latter-day Saint communities with branches of the AFA included Cardston, Raymond, Magrath, and Stirling.[12]

Named “one of the most progressive and enterprising farmers of Southern Alberta,” Latter-day Saint Thomas H. Woolford (1856–1944) joined the AFA and served as president of the Cardston AFA branch.[13] Woolford moved to Canada from Utah in April of 1899 and settled on land that is now known as Woolford Provincial Park. In 1903 Woolford reported threshing a sum total of 7,700 bushels of grain (oats, barley, and wheat).[14] In 1907 he joined the executive committee of the AFA as vice president.

In 1909 the AFA merged with the Canadian Society of Equity to create the government lobby group known as the United Farmers of Alberta (UFA). The Society of Equity, sharing similar goals with the AFA, tried to obtain profitable prices for all products of the farm garden or orchard, to build and control storage of produce, to secure equitable rates of transportation, to educate, to prevent the adulteration of food and marketing of same, to establish an equitable banking system, and to improve the highways.[15] The Society of Equity combined with the AFA in order to further advance the causes of the farmers in the province.

The UFA was originally meant to be a nonpartisan organization/

Because of his experience within the Disciples of Christ and at Christian University in Missouri in the late 1890s, Wood developed a particular social and political theory directly tied to his faith. Wood believed that humans are natural social beings who are destined to construct a proper social system within which they can flourish. For Wood, history progressed in a linear fashion, characterized by a cosmic struggle between two opposing forces, cooperation and competition. At the end of this evolutionary process would be the creation of the morally perfect individual within a perfectly moral society. The kingdom of heaven on earth, according to Wood, would come about from individual and social regeneration. Individual regeneration involved repentance and following natural social laws, the moral laws of Christ. Social regeneration would be initiated by those who had accepted the teachings of Christ and desired to build a social system founded upon the call for social cooperation issued by Christ through a gradual, evolutionary process. “Wood adhered to a clear evangelical postmillennial Christian interpretation wherein humanity was to bring about a perfect social system, which he equated to God’s kingdom on earth, by way of personal, and eventual social, devotion to the co-operative message of Christ.”[18] The agrarians of rural Alberta would handle the practical details of this process.

Wood promoted a rural social gospel movement that would establish the kingdom of God on earth by “large-scale voluntary individual regeneration” and “co-operation of those regenerated individuals within voluntary organizations.” It would not be established by government regulation.[19] While emphasizing democratic participation and individual responsibility, Wood rejected increased state ownership and socialism, believing instead that rebirth through Christ would cause the regenerated people to accept the cooperative spirit, issued by Christ, and work at the local level to secure policy decisions and economic well-being.[20] The challenges following the First World War—including the struggling economy, increasing living costs, dependence on credit, and the spread of influenza—fueled southern Alberta farmers’ requests that the UFA lend some assistance and organize a wheat pool in order to force governments to lower producers’ costs and assist with irrigation.[21] Farmers were dissatisfied with numerous issues such as the government’s handling of prohibition, health policy, debt, the farm mortgage crisis, the lack of credit assistance, and the province’s irrigation policies. In 1921 the movement officially politicized, and Albertan farmers launched “what would be the most resilient agrarian political crusade in North American history.”[22] Although some Latter-day Saints in southern Alberta joined the Canadian Liberal or Conservative parties, the UFA drew many Saints into their organization.

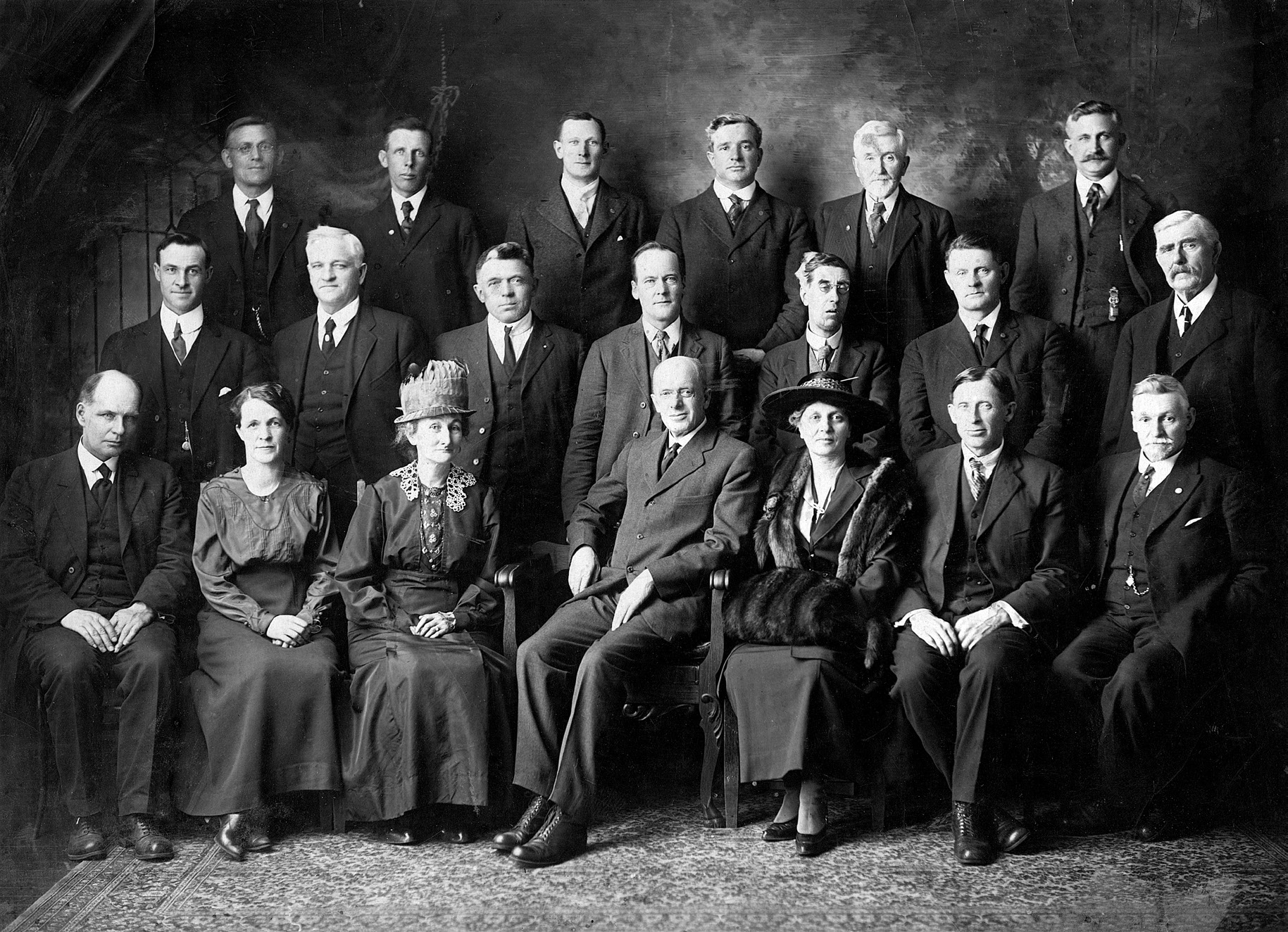

United Farmers of Alberta and United Farm Women of Alberta, Board of Directors, 1919. Glenbow Archives PB-244-2.

United Farmers of Alberta and United Farm Women of Alberta, Board of Directors, 1919. Glenbow Archives PB-244-2.

Lawrence Peterson (1873–1951) moved from Provo, Utah, to Raymond, Alberta, in 1902 and eventually settled in Barnwell near Taber. According to the Barnwell Relief Society, the first UFA meeting in the area was held in March 1913, and the twenty-six members selected Peterson as their first president.[23] Other Latter-day Saints who took an active interest in the UFA were William F. LeBaron (1884–1968), A. M. Peterson, N. J. Anderson (1884–1958), and A. Anderson, all of whom accompanied Peterson to the UFA’s annual convention in 1915 and 1916. Latter-day Saints formed UFA groups, or locals, in Magrath, Raymond, Leavitt, Stirling, Barnwell, Spring Coulee, Cardston, Taber, and Mountain View.[24]

In 1919 UFA members elected Peterson as the director of the entire constituency of Lethbridge.[25] Another active UFA member and Latter-day Saint was Frank Leavitt (1870–1959) who, according to Peterson, offered great assistance in the year 1919.[26] In his report for 1919, Peterson said that the “Cardston Local and those surrounding [e.g., Aetna, Leavitt] have carried on a very successful co-operative trading company.”[27] Members of the Cardston District UFA purchased a building site from the Cardston Creamery, another local cooperative endeavor, and constructed a large warehouse to “sell practically everything required by the farmer from machinery of all kinds down to smaller effects and in time, possibly groceries.”[28] An advertisement for the Cardston District UFA Co-operative Association said, “High Cost of Living Reduced. Come and see us in our new Warehouse. The busiest place in town.”[29] In October, the Co-operative Association claimed that they were the only organization in the province to receive hay at “snipped” prices, enabling them to sell it for $20 per ton.[30]

In 1921 Peterson reported on additional progress: “Raymond and Magrath have also obtained a good deal of success along co-operative lines. . . . Through the elections the farmers have learned the power they have when working together. . . . I believe that if every U.F.A. member will take his proper place in this great work by helping wherever he finds an opportunity, we shall be able to put Democracy in action, in the truest sense of the word.”[31] Active Latter-day Saint locals in 1921 were the same as in 1918 with the additions of Kimball, Taylorville, Spring Coulee, and Aetna.[32]

In 1921 the UFA won thirty-eight seats out of the sixty-one electoral districts in the provincial election, taking a majority government and pushing the Liberals out of power. The Cardston Review stated that the Liberal government “was not overturned by an irate electorate who had lost confidence in the administration, but by a friendly group with different ideals of government and perhaps with progressive plans in legislature.”[33] Alternatively, looking back on the 1921 provincial election, the Globe and Mail summarized the UFA’s strategy and success:

They capitalized on discontent among farmers, who faced hard times due to years of drought and a plunge in grain prices after the wartime economic boom. Accordingly, the UFA focused its campaign only on rural ridings, running only one candidate in Edmonton and none at all in Calgary.[34]

Latter-day Saints George L. Stringam (1876–1959) and Lawrence Peterson (1873–1951) won two of these seats, Stringam for the Cardston constituency and Peterson for the Taber constituency. Cattle rancher George L. Stringam was born and raised in Utah and moved to Alberta in 1910 after purchasing half a section of land north of Glenwood.[35] He participated in politics at the municipal level until 1921 when he entered the race for Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) as a UFA candidate; he earned 1,343 votes while Liberal candidate Martin Woolf (1858–1928) earned 651. Peterson ran in the Taber district of the provincial election as a UFA candidate against the Liberal incumbent Archibald J. McLean (1860–1933) and won with 2,309 votes over 1,991 for McLean.[36] He prevailed again in 1926 against the Liberal and Conservative candidates for the Taber electoral district.[37]

Cooperation remained a consistent platform of the UFA. This aspect might have drawn the attention of Latter-day Saints and been a reason for their participation in the movement and political party since they valued and practiced cooperation from the start of settlement in Alberta. This phase in their economic history known as “the co-operative movement” lasted, according to Latter-day Saint Church Historian (1972–1982) Leonard J. Arrington, from 1868 to 1884.[38] However, his description of the Church colonies in Alberta and Mexico (Sonora and Chihuahua) presented situations typical of the supposedly dead movement. Arrington wrote,

Each of the new settlements was designated as a gathering place, and nearly all were founded in the same spirit, and with the same type of organization and institutions, as those founded in the 1850’s and ’60’s. Colonizing companies moved as a group, with church approval; the village form of settlement prevailed; canals were built by co-operative labor; and the small holdings of farm land and village lots were parceled out in community drawings.[39]

Furthermore, ecclesiastical corporations in the 1880s held church property, and mercantile and industrial cooperatives became incorporated as joint-stock concerns.[40] One of these corporations was the Alberta Land and Colonization Company, incorporated in 1896.

As those first Latter-day Saints remembered it, there was no practice of the United Order (a cooperative and communal economic plan) in Cardston, but as William L. Woolf (1890–1982) explained in an interview, “the people were very co-operative.”[41] They were so cooperative that they formed a “joint-stock corporation, organized under the sponsorship of the church, with a broad basis of public ownership and support . . . motivated principally by welfare rather than profit; patronage was an act of religious loyalty.”[42] Arrington further explained,

Cooperation was deliberately promoted by the church as a solution to its problems, both spiritual and material. Cooperation, it was believed, would increase production, cut down costs, and make possible a superior organization of resources. It was also calculated to heighten the spirit of unity and “temporal oneness” of the Saints and promote the kind of brotherhood without which the Kingdom would not be built.[43]

Before the cooperative efforts in southern Alberta, the Church in Utah faced many financial challenges, including the panic and financial depression of 1873 that initiated the extension of “the co-operative principle to every form of labor and investment, and to cut the ties which bound them to the outside world.”[44] That year the United Order Movement began, and the Church asked each member of the community to donate his property to “the Order” and receive in return the equivalent capital stock.[45] Some united orders required members to share the net income of the enterprise rather than work for fixed wages, others required members to donate all their property and share everything equally, or the united order functioned like a joint-stock company with the aim of helping already existing cooperatives (no one was required to give up their property).[46] Members of the Church established about two hundred united orders in their communities, but this ended around 1877, according to Arrington, and in 1893, according to the Encyclopedia of Mormonism.[47] In Alberta, a third type of united order existed where

such orders did not require consecration of all one's property and labor but operated much like a profit-sharing capitalist enterprise, issuing dividends on stock and hiring labor. . . . Brigham Young believed that pooling capital and labor would not only promote unity and self-sufficiency but would also provide increased production, investment, and consumption through specialization, division of labor, and economies of scale.[48]

In 1888, by their second summer in the district of Alberta, the Latter-day Saints considered implementing a united order. At the Card residence, Zina Y. Card (1850–1931) told the Cardston Relief Society that they should prepare “to live in the United Order.”[49] That winter, Charles Ora Card opened the first general store and began as the sole owner.[50] However, less than a year later, the Saints in Cardston hoped “to incorporate for rearing stock, Co-operative Stores, Dairy, Saw mill and Grist mill purposes,” and Card thus met with a lawyer named Haultain to begin the paperwork.[51] At a priesthood meeting in May 1890, Card, as recorded in his personal diary, discussed “the necessity of unity among [the Latter-day Saints] in all things temporal and spiritual. [He] Advised cooperation in our business operations. Advised the brethren to herd out stock and save our grain. Advised the brethren to take the Oath of Allegiance to the Canadian Government. Also to pay their tithes and offerings.”[52] Card wanted to accomplish two goals: group cooperation among Saints themselves and at least the appearance of loyalty to the Canadian government. The members must work together to prosper, but, at the same time, they must not alienate themselves from help that might come from government officials. In 1892 the Cardston Company was granted incorporation.[53] The first directors on the board for Cardston Co. Ltd. were Charles Ora Card, John Anthony Woolf (1843–1928), Samuel Matkin (1850–1905), Oliver L. Robinson (1860–1948), Neils Hanson (1832–1902), and Heber S. Allen (1864–1944) as secretary.[54] The board elected Card as the first director and then president.

Grain elevators in Stirling, Alberta, ca. 1937. Glenbow Archives PD-220-85.

Grain elevators in Stirling, Alberta, ca. 1937. Glenbow Archives PD-220-85.

Under the UFA provincial government, an example of cooperation put into practice was the Alberta Wheat Pool. A year before the UFA won the provincial election, the Canadian Council of Agriculture passed a resolution providing for the appointment of a Wheat Pool Committee to be composed of representatives from the four provincial farmers’ organizations and the farmers’ companies.[55] Establishing a national pool became too difficult to accomplish, but the UFA continued at the provincial level and passed a resolution asking for direct selling of commodities through a means whereby speculation could be eliminated.[56] In 1923 the U.F.A. newspaper reported that “U. F. A. Locals in the Cardston, Claresholm, Granum and Macleod districts are making efforts to organize a local wheat pool.”[57] Henry Wise Wood’s presidential address also acknowledged that “the idea of co-operative selling of wheat has been crystalizing in the minds of the Alberta wheat producers for four years.”[58] The wheat pool committee organized under the association called Alberta Co-operative Wheat Producers, Limited, which acted as the agent and attorney for the contracting wheat growers. The main features of the Alberta Wheat Pool were that “the association would be a co-operative, non-profit organization, without capital stock. All surpluses, after defraying operating expenses and providing for adequate reserves, would be returned to the members in proportion to the wheat shipped.”[59] “It is now up to the individual members of the U.F.A. to put into practice those principles of co-operation which have been so long preached.”[60] Grain growers signed a contract stating that

the undersigned Grower desires to cooperate with others concerned in the production of wheat in the province of Alberta and in the marketing of same, hereinafter referred to as Growers for the purpose of promoting, fostering and encouraging the business of growing and marketing wheat co-operatively and for eliminating speculation in wheat and for stabilizing the wheat market, for co-operatively and collectively handling the problems of Growers for improving in every legitimate way.[61]

Christian Jensen (1868–1958), another Latter-day Saint, worked in both his Church and local UFA. In the 1920s he acted as the director for the Lethbridge Constituency.[62] He was also a main player in the birth of the Alberta Wheat Pool. Jensen sat as a trustee on the board of the Alberta Co-operative Wheat Producers, Ltd., the central selling agency located in Calgary, from its inception in 1923. He was also a director for the Lethbridge district of the pool until 1945.[63] In addition to these roles, Jensen served as president of the Canadian Co-operative Wool Growers association from 1937 to 1949 and first president of the Alberta Federation of Agriculture.[64] The cooperative movement in Alberta stemmed from the tradition in England called the Rochdale Plan, where an organization of textile workers united and decided that “dividends, instead of being paid on the basis of capital invested, were paid on a basis of volume of business done, capital being borrowed at a fixed rate of interest. After provision for reserve and educational funds and necessary overhead, all surplus profit was divided among the purchasers in proportion to the volume of their buying.”[65]

Cooperation and economic goals were never far from UFA meetings. At a meeting for Cardston and Magrath Locals in 1925, politician William Irvine (1885–1962) said that “the hope of civilization was to be found in the co-operative idea.”[66] In 1926 Henry Wise Wood lectured to an audience in Cardston on the economic and political goals of the UFA. Wood explained, “What the U.F.A. aims at is to have all classes cease exploitation of each other, but rather increase their efficiency for the benefit of all.”[67] On the topic of the UFA movement, an article in the Cardston News elaborated that “it is a great socializing and educational factor in the lives of thousands. . . . It enters into their daily activities as no other organization, except the [restored Church of Jesus Christ], has ever done. . . . It is true that some sections of the country were not so much in need of the U.F.A. as a social factor, as particularly the Cardston District, where the Church supplies this need to a very great extent.”[68] Similar to a Church ward or branch, a UFA Local held regular meetings and gathered scattered farmers to congregate at least once a month to discuss agriculture, politics, moral issues, and finances. Sometimes a UFA Local organized debates and dealt with subjects such as consolidated rural schools, compulsory social insurance, municipal hospitals, and women’s suffrage.[69] According to a pamphlet on how to organize a UFA Local, additional subjects for discussion included infant mortality, district nurses, the beef ring, rural mail delivery, and elimination of waste.[70]

Why would Latter-day Saints join the UFA? According to his daughter, Jensen joined the UFA because of his anger for “the entrenched grain trade monopoly” and the realization that farmers needed “to unite co-operatively to benefit their position in the matter of grain grading, markets and marketing practices.”[71] They joined because most of the Saints in southern Alberta were farmers, ranchers, or otherwise involved in agriculture. Known as active Latter-day Saints and community builders, Clyde Bennett, a UFA member, and his wife Inez Bennett, active in the United Farm Women of Alberta, participated in the agrarian movement “to get better farm conditions.”[72] Furthermore, they might have believed that “the U.F.A. is the most powerful agency in Canada to-day for the establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth.”[73] This may not have been the same as the Latter-day Saint version of the kingdom of God, but they at least shared the concept of cooperation and Christian beliefs. At the 1926 UFA convention, during a successful resolution regarding cooperative marketing, members agreed that

the past few years considerable emphasis has been laid upon co-operative marketing of farm projects. . . . the fruits of the efforts are now being realized notably in the case of the Wheat Pool, and the Southern Alberta Co-operative. . . . there are still large numbers of farmers, who because of special circumstances or because of indifference, or because of their inability to see the interests of their class, are still outside of these movements; Be it therefore resolved, that this Convention call upon all farmers in the Province to give their support to these movements and thus assure the ultimate victory of the farming industry.[74]

Success of the farming industry equaled, in the minds of UFA members, success for the entire province, no matter what class you were.

In the 1926 election, Stringam faced Conservative candidate Joseph Y. Card (1885–1956) and Liberal candidate Walter H. Caldwell (1875–1962). Caldwell’s father, David Henry Caldwell (1828–1904), was born in Upper Canada, joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1843, moved to Nauvoo, Illinois, and completed the trek to Utah in 1853. David, a farmer, moved his family to Cardston in the summer of 1898. Walter Caldwell also farmed, but by the 1920s worked as a butcher. In the 1926 election, Liberal candidate Caldwell advocated for a reduction in taxation and the payment of the provincial debt.[75] Conservative candidate Card worked as a real estate and investment broker and served as president of the Cardston Board of Trade. Joseph was two years old when his father, Charles Ora Card, started the migration to southern Alberta, but he frequently traveled between the United States and Canada; Joseph also attended Brigham Young College in Logan, Utah. Walter and Joseph both descended from prominent Latter-day Saint men, and their lives were not restricted to farming, which might explain their attraction to political parties other than the UFA.

Stringam returned to the legislature with over 1,300 votes, defeating Conservative candidate Joseph Y. Card and Liberal candidate Walter H. Caldwell (both men were also Latter-day Saints). However, in the town of Cardston itself, Caldwell received 298 votes, Card 200, and Stringam only 193.[76] Caldwell, former mayor of Cardston and a town resident, appealed to some citizens of Cardston because of the constituency’s Liberal heritage before the UFA’s political action. The smaller, more rural villages voted overwhelmingly in favor of Stringam. He received approximately 96 percent of the vote in Glenwood, 94 percent in Leavitt, 59 percent in Aetna, 56 percent in Magrath, and 69 percent in Hill Spring.[77] That year, the UFA maintained its majority government and earned forty-three seats.

In his speech at the 1930 UFA Political Nominating Convention, Stringam stated, “My Policy is that whatever is best for the Province as a Whole is best for this constituency.”[78] Stringam’s concept did not differ drastically from the organization of the Church of Jesus Christ. Sociologist Thomas O’Dea explained the hierarchical structure in The Mormons: “The original relationship between the prophet and his disciples evolved into a relationship between the prophet and an oligarchy of leading elders, which merged into and exercised ascendancy over the rank and file of the membership.”[79] Responsibility moved from the bottom up while authority came from the top down since a living prophet remains the highest role in the Church.[80] The UFA functioned through its Local organizations (rank and file of the membership), facilitating social and individual regeneration, and it expected these Locals to cooperate and do what was best for the province of Alberta. What was best for the province was decided by the government, the provincial legislature run by the UFA, but objectives would be accomplished at the local level.

Social Credit Movement

The Great Depression engulfed the 1930s and “opened the way for a change in government and ideological direction, in that Social Credit had no interest in the UFA’s notion of co-operative ‘group government’ and was based on a leader-oriented type of democracy.”[81] Social credit theory “blamed the current economic conditions [the Great Depression] on a lack of purchasing power possessed by regular citizens, who were beholden to large financial institutions that controlled credit. . . . the economy was slowed to a halt because self-interested bankers refused to lend at reasonable rates.”[82] The solution, according to this theory, was to have the state “take control of credit away from greedy financiers . . . and provide its citizens with a share or ‘dividend’ of this ‘social credit’ to allow them to buy goods.”[83] But this is what Charles Ora Card attempted years ago in Cardston. He issued hundreds of scrips to community members to use at cooperative businesses, but people were unable to pay him back, which compromised the Cardston Co-operative Company. In 1895, the population of Cardston approached 1,000 residents, the cheese factory produced over 45,000 pounds of product, the sawmill produced over 180,000 feet of lumber, the grist mill ran six months of the year at a capacity of 180 bushels per diem, and farmers cultivated over 750,000 acres of land.[84] It was in the aftermath of this prosperity when Card issued scrip to the citizens of Cardston to use at the cooperative store or cheese factory. In his diary, Card wrote,

I signed my name to 700 Pieces of scrip or mdse [merchandise] Orders for the Cardston Co. Ltd our co-operative store & cheese factory. This is our first Issue of Printed issues of which we have $500.00 printed. I signed up $890.00 being 100 pieces each denomination 5, 10, 25 & 50 cents, 100 each of $1.00, $2.00 & $5.00.[85]

But, by February 1896, three years into the depression of 1893–1897, the large number of people failing to pay their accounts placed the Cardston Company in trouble, and Card spent the month of March looking to borrow $4,000 to aid the business.[86] Social scientist S. D. Clark confirmed,

The close relationship between sectarian techniques of religious control and monetary techniques of economic and political control has been most evident, of course, in the Social Credit experiment in Alberta; here the Mormon members of the government in particular had a perfectly good historic example in the use of scrip and the carrying-on of banking operations by the Mormons in Utah.[87]

Less than five years later, Card resigned from the Cardston Company, and four community members purchased all interests of the company.[88]

William Aberhart, founder of the Alberta Social Credit Party, was motivated by a fundamentalist, premillennial, religious-based political thought that rejected the idea of a kingdom of heaven on earth, emphasized individual freedom, and vilified socialism.[89] The social credit theory appealed to politicians such as Aberhart because it provided a way to fulfill the general Christian duty toward others by guaranteeing an end to the suffering associated with the economic hard times, and it protected individual freedoms vital to personal spiritual growth, which, in their opinion, socialist plans did not.[90] For Aberhart and other premillennialist thinkers, the coming of the kingdom of God existed outside the realm of human agency so Christians should focus on assisting others in their spiritual rebirth before the Rapture.[91] Although Latter-day Saint millennial expectations were not as pessimistic as Aberhart-type premillennialist theories, they did agree on concepts of individual liberty, sharing the Christian message with others, and placing trust in a leader. Clark observed, “The religious-political experiment in Alberta resembled very closely that tried much earlier in Utah; in both cases, religious separatism sought support in political separatism, and encroachments of the federal authority were viewed as encroachments of the worldly society.”[92] However, in the 1930s, as the Social Credit Party battled the UFA for control of provincial politics and debated social-economic-political theories that seemed similar to Latter-day Saint united orders and past economic experiments, in reality, Utahns and American Latter-day Saints had already shed their commitments to communal economic systems in favor of individualism and private wealth. Thus, the political messages received and welcomed by Saints in southern Alberta sometimes contradicted the socioeconomic cultural conventions adopted by the American Saints.

“The UFA pursued giving life and form to direct democracy in government, but Social Credit’s democracy was more plebiscitary. In its view, governmental policy making, a matter of technical skill and special qualification, was best left to experts.”[93] In his essay for The New Provinces: Alberta and Saskatchewan, 1905–1980, professor of religious studies Earle Waugh noted a list of reasons why Church members in southern Alberta consistently supported social credit. First, Aberhart’s eschatological teachings matched their idea of building Zion in the American West and, in addition, appreciated the labor of the ordinary worker.[94] Concerning Zion specifically, Latter-day Saints believed that the establishment of Zion (both God’s followers and a place of gathering) would lead to the millennial reign of Christ.[95] Aberhart’s political leadership style would have reminded the Saints of their religious leaders because Aberhart “ruled Alberta from an authoritarian position, and he dealt directly with citizens through his radio broadcast and his frequent public meetings. . . . all important decisions were left to his personal discretion.”[96] This style of direct communication resembled how, in the Church of Jesus Christ, God spoke directly to the people. Third, the mix of politics and religion was familiar to the Saints since most settlers in southern Alberta came from Utah, where “a unique and religiously permeated political culture” operated and many “locally controlled government offices were held by ecclesiastical leaders.”[97] Also, the notion of a creative work ethic attracted Latter-day Saints to social credit because they believed “that individual initiative and activism had transcendent import [and] underlined the necessity of providing the opportunity for sanctified labour.”[98] Lastly, Aberhart and Latter-day Saints shared a unique eschatology where they were ideologically premillennialist, but practiced a postmillennial enthusiasm.[99] They believed Jesus Christ would usher in the Millennium, but they did not adopt a pessimistic view of their current situation, the Depression, and instead saw temporal and spiritual advantages to improving their circumstances.

While some Church members climbed on to the social credit wagon, the Church itself shifted its own ideology concerning economic well-being. The United Order, a cooperative and communal economic plan, became a concept reserved for implementation when Jesus redeemed Zion during the Millennium. In the 1930s stake presidents in urban areas arranged with nearby farmers to have “idle urban members” assist with the harvest in return for a share of the crops to store in Church-controlled facilities and to be distributed according to need.[100] This initiative led to the establishment of welfare farms under Church ownership. In Cardston in 1938, Mark A. Coombs (1868–1944) reported that the Alberta Stake Welfare Committee began “preparing to assist those who may be in needy circumstances this winter . . . preparing to begin work at once on a cellar to store produce expected to be received from the various wards of the stake.”[101] Bishops of the surrounding wards reported that “excellent co-operation is being given by all the wards of the stake in welfare work, and that canning of fruits and vegetables, and raising of wheat are being carried out as community projects.”[102] That August the Alberta Stake began construction of a large storage cellar near the old Bishop’s Storehouse and tithing barn.[103] James Forest Wood (1903–1995), son of Alberta stake president at the time, Edward J. Wood, remembered gardening and canning as welfare projects that replaced government assistance.[104] Similarly, John O. Hicken (1905–1987) recalled a welfare center in the 1930s with a canning factory and storehouse.[105]

At the quarterly conference for the Taylor Stake in July 1938, Elder Stringham A. Stevens of the Church Welfare Committee educated the audience on the Church’s welfare plans, explaining that “it was not a dole” but a method of collecting from those who had a surplus and shifting some of that surplus to those in need.”[106] The Church’s First Presidency later advised members to rely on the Welfare Plan from the Church and not from their government. They stated that government welfare “would run contrary to all that has been said over the years since the Welfare Plan was set up [in 1936]. . . . these isms [Socialism and Communism] will . . . destroy the free agency which God gave to us.”[107] Myrtle Passey (1893–1983) was president of the Taylor Stake Relief Society from 1939 to 1947 when the main objective was welfare in every phase, both temporal and spiritual, and the plan was “We will take care of our own” and not accept government aid.[108] Assistant Church Historian Andrew Jensen recorded the purchase of six acres of irrigated land in 1940 by the Magrath First Ward for the purpose of ward welfare work.[109] Over in Aetna, the Aetna Welfare Committee entered the cattle business, and “every family in the ward [was] asked to contribute one calf or its equivalent, to be delivered to the committee on the 6th day of May.”[110]

At the forefront of the Church Welfare Plan in Canada was soil chemist and dryland farming specialist Asael E. Palmer (1888–1984). Minutes from a meeting of the Canadian Regional Welfare Committee, which Palmer chaired, revealed plans involving canning projects spread through all Latter-day Saint stakes in Alberta. By the summer of 1939, the Alberta Stake had seven small units to process vegetables and meat. The Taylor Stake operated one unit and the Lethbridge Stake had five units with a daily output of one thousand cans.[111]

As the province entered the long reign of the Social Credit Party (Social Credit stayed in power until 1971), many Saints in southern Alberta aligned under the Social Credit platform of ending economic hard times, fulfilling Christian duty to one another, and protecting individual freedoms. The Church Welfare Plan provided the balance sought by Albertan Latter-day Saints since it both protected individual freedom and free agency vital to spiritual development and aimed to end the suffering associated with the Depression through the actions performed by Latter-day Saints to benefit another’s welfare.

Co-operative Commonwealth Federation

Not all Albertan Latter-day Saints stayed with the Social Credit Party, and some were enticed by the ideology of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. In 1932, while Aberhart introduced social credit theories during his weekly radio program, other Albertans, also disillusioned with the UFA and current economic conditions, gathered in Calgary and formed the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF). The CCF Manifesto, grounding itself in the ideas of European socialism, petitioned for the nationalization of banks and reform of credit institutions.[112] However, the results of the 1935 and subsequent provincial elections demonstrated that approximately 90 percent of UFA members transferred their allegiance to Social Credit and not the CCF.[113] Nonetheless, some Latter-day Saint UFA members did switch to CCF. Some members of both Labour and Farm organizations saw the only solution to the Great Depression to be drastic economic reform. “The C.C.F.’s ideological background had clear socialist elements; and it sprang from the urban labour movement, from the social gospel of the churches, and from radical intellectuals, as well as from the soil of the wheat belt.”[114]

One of the leaders of the CCF was John Johansen, a Latter-day Saint in Woolford. Johansen’s father was Peter Johansen (1827–1895), who met, and later married, Ane Christensen (1836–1899) on their journey from Denmark to Utah in 1858 first upon the ship John Bright from Liverpool to New York and then during their overland travels in the Russell K. Homer Company.[115] Peter took a plural wife, Larsena Jacobsen (1846–1923) in 1869, eight years before the birth of his son John Albert Johansen (1877–1957). John and his wife Anna moved to Raymond in 1904 and lived there for two years before moving out near Woolford.[116] As an active member of the Church of Jesus Christ, Johansen was immediately appointed to the Taylor Stake Sunday School Board and, after his move to Woolford, given charge of the Woolford Sunday School as superintendent until 1913. He became second counselor to Leo Harris, bishop of the Woolford Ward, and first counselor in 1915 to Bishop W. T. Ainscough Sr. He served as first counselor until 1924 when he was called as bishop for five years.[117] Johansen farmed two sections of land near Woolford, served on the Woolford district school board for nine years, and was central to the organization of the Cardston Municipal Hospital.[118]

In August 1935, Johansen received the nomination as UFA-CCF (later just CCF) candidate for the Lethbridge federal constituency. In his acceptance speech, Johansen promised to raise the standard of living by ensuring that “the natural resources . . . must belong to the people with every individual getting the benefit of what he produced by the application of real work and human effort.”[119] That October community members gathered in the Cardston School gymnasium in support of the CCF and Johansen. Among the crowd were prominent Latter-day Saints James Walker (1885–1954) and Melvin King (1891–1974).[120] Speaking to the room of supporters, Johansen lectured on the subject of trade, refuting the notion that “competition [was] the Life of Trade” and stating that “the Co-operative movement is the spear head of a new day.”[121]

The 1935 federal election placed Liberal leader William Lyon McKenzie King (1874–1950) in power in Ottawa, but Alberta, once again, was mostly Social Credit. As reported by the Cardston News on 15 October 1935, Johansen earned 700 votes, the Reconstruction candidate Gladstone Virtue earned 424, Lyn E. Fairbairn (Liberal) earned 2,104, J. S. Stewart (Conservative) earned 2,910, and John H. Blackmore (Social Credit) earned 6,473.[122]

In the 1944 provincial election, the CCF candidate for Cardston was Edward Leavitt (1875–1958) of Glenwood.[123] At a CCF meeting in the Cardston school gym (still in the gym and not the tabernacle or meetinghouse), Leavitt spoke on the policy of nationalizing banks and promised that rather than nationalizing banks, the CCF could set up local branches and remove financial control from the hands of the few (the nine chartered banks in Canada) in order to benefit the people of Canada.[124] Part of the CCF platform included free health insurance and other social services, as well as people’s ownership and control of natural resources.[125]

Conclusion

The story of the Latter-day Saints in southern Alberta began with their distinctive building strategies and town planning based on the Mormon Farm Village. By keeping the family homes close together with the conveniences of town life, community members attended regular Church and social meetings. Latter-day Saint areas fostered close-knit communities and prevented isolation sometimes experienced on faraway homesteads. The Saints transcribed the values of cooperation and unity once taught in Utah to their new homes in Alberta. Welfare, not simply profit, weighed heavily on the minds of the Saints, and they wanted all community members to not only survive but also thrive in Alberta.

Political participation at all levels of government demonstrated the Saints’ acceptance of their permanency in Canada and their willingness to contribute to issues concerning their immediate communities. Members in southern Alberta also differed from their American counterparts by involving themselves in three distinctly Canadian and Albertan political parties: the UFA, Social Credit Party, and CCF. Participation in these three parties made room for a greater expression of cooperative economics at a higher level. It was one way Latter-day Saints shared something critical to their faith (cooperation and unity) with outsiders who agreed on the importance of such qualities. The Wheat Pool, for example, like a Latter-day Saint cooperative company, required the pooling of resources and finances, along with the trust and cooperation of the parties involved who relied on the “profit” for survival or to support their family.

The theme of business and politics showed the various layers of integration into Canadian society. The Latter-day Saints kept the traditions and practices of the homeland (farm village and communal economics), which gave them an initial status as “Other” to those who were not members of their church. Saints in southern Alberta also found themselves creating some distance between themselves and their American brethren in terms of political ideology. Integration into Canadian society did not mean sacrificing one’s entire identity. It meant balancing both fitting in (e.g., through political participation) and maintaining boundaries (e.g., through lay participation) that reminded them of their distinctiveness as Latter-day Saints.

The process also made them different than the Church in America because of Canadian culture and context. In the United States, explained Yorgason,

The major turn-of-the-century change was not that Mormons suddenly became capitalists. Many church members had already successfully embraced such principles. Rather, the key transformation was further acceptance of capitalist cultural logic. . . . Less discussion remained of people sharing responsibility for one another’s welfare on a community scale. Moral strictures by 1920 centered on a person’s (a man’s) responsibility to provide for his family.[126]

The Saints in Utah reinterpreted their history, focusing more on socially conservative aspects rather than on radical ones, and “by merging its destiny with America’s destiny and starting to behave like other churches, insulated itself from critiques of power relations between leaders and members.”[127] In Alberta, however, the Latter-day Saints aligned with fellow Albertans rather than Canadians in the east. “By the 1920s, the [American] Mormon culture region’s dominant moral order suggested that to question the nation’s power and norms was to unleash the forces of anarchy, religious struggle, and unwelcome authoritarianism.”[128] In Alberta, to question the nation’s power (Ottawa’s power), as members of the UFA and Social Credit did, was the norm.

Notes

[1] John S. McCormick and John R. Sillito, A History of Utah Radicalism: Startling, Socialistic, and Decidedly Revolutionary (Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 2011), 9.

[2] McCormick and Sillito, History of Utah Radicalism, 10. These historians highlight that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints transformed from a “radical challenge to the American way of life” to a deliberate incorporation into its mainstream. While this happened, the Socialist Party of America attracted some Utahns and Latter-day Saints. McCormick and Sillito, History of Utah Radicalism, 11.

[3] Ethan R. Yorgason, Transformation of the Mormon Culture Region (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 98–105.

[4] “Keynes argued that the answer to such destabilizing private-sector behaviour was an activist public-sector stabilization policy. He specifically argued for increased government expenditures and lower taxes to raise demand and pull world output and employment out of their Depression slump.” See Ronald G. Wirick, “Keynesian Economics,” in The Canadian Encyclopedia, published 7 February 2006 and last edited 8 January 2014, https://

[5] John Taylor (1808–1887) started life in Milnthorpe, Westmorland, England; was christened in the Church of England; and later became an adult member of the Methodist Church. His parents relocated to Upper Canada around 1830, and John joined them in Toronto in 1832 where his connections to Methodism led him to his first wife Leonora Cannon (1796–1868), whom he married in January 1833. Growing dissatisfaction with the Methodist Church and a meeting with Latter-day Saint missionary Parley P. Pratt (1807–1857) opened the Taylors to learning about the new church. According to Latter-day Saint Church history, Pratt baptized John and Leonora in the year 1836 in Black Creek at Georgetown, Ontario. The following year, the Prophet Joseph Smith (1805–1844) traveled to Upper Canada and soon called John Taylor as an apostle, an ordained leader of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which required his relocation to Missouri. Taylor eventually became the third President and Prophet of the Church in 1880.

[6] Geo Takach, Will the Real Alberta Please Stand Up? (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2010), 64.

[7] B. Y. Card, “Introduction,” in The Mormon Contribution to Alberta Politics, ed. Ernest G. Mardon, Austin A. Mardon, Catherin Mardon, and Talicia Dutchin (Edmonton: Golden Meteorite Press, 2011), x.

[8] “Mormons in the Economy & in Government,” in The Mormon Presence in Canada, ed. Brigham Y. Card et al. (Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press, 1990), 232.

[9] Clark Banack, God’s Province: Evangelical Christianity, Political Thought, and Conservatism in Alberta (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016), 63. According to Banack, the UFA emerged out of the conflicts surrounding the American liberal and postmillennial evangelical Protestant tradition, higher criticism, and the adoption of the Darwin-inspired “evolution-friendly conception of social change driven largely by human action in accordance with the moral teachings of Christ.”

[10] Bradford James Rennie, The Rise of Agrarian Democracy: The United Farmers and Farm Women of Alberta, 1909–1921 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000), 35.

[11] “The Farmers’ Association,” Saturday News, 30 December 1905, 6.

[12] Alberta Farmers’ Association minute book, 1906–1907, United Farmers of Alberta fonds, Glenbow Archives, Calgary, Alberta (hereafter cited as UFA fonds). Secretaries of the branches were as follows: Cardston—Edward Neale Barker; Raymond—James Francis Johnson (1879–1941); Magrath—George A. Hacking (1876–1955); Stirling—Frederick Zaugg (1869–1956). Prominent members of the Raymond branch were Thomas J. O’Brien (1866–1938) and Francis B. Rolfson (1872–1941).

[13] “Consider Farmers’ Interests,” Edmonton Bulletin, 1 August 1908, 6.

[14] “Local and General,” Alberta Star, 26 November 1903, 8. In 1906 Woolford reported to the Cardston Star that his oats went 115 bushels to the acre without irrigation. “Local Topics,” Lethbridge News, 30 October 1906, 4. Another prominent Latter-day Saint farmer was Richard W. Bradshaw (1868–1948) in the Magrath settlement. Bradshaw moved his family from Lehi to Alberta in 1901 and eventually acquired Rosedale Farms, initially producing fine cattle and award-winning wheat, and later expanding into the importing and breeding of Percherons. See Vilate Bradshaw, “Biography of Richard William Bradshaw,” contributed by richardcarlylebradshaw1 on 9 March 2015, https://

[15] Society of Equity constitution and bylaws, ca. 1906–1908, UFA fonds.

[16] Rennie, Agrarian Democracy, 7.

[17] Banack, God’s Province, 65.

[18] Banack, God’s Province, 78.

[19] Banack, God’s Province, 85.

[20] Banack, God’s Province, 91–95.

[21] Rennie, Agrarian Democracy, 180.

[22] Rennie, Agrarian Democracy, 206. In Utah, at this time, the state said goodbye to its first non–Latter-day Saint, Democratic governor Simon Bamberger (1845–1926), who served as governor of Utah from 1917 to 1921. Bamberger, while under the heading of “Democrat,” aligned with the short-lived Progressive Party of Theodore Roosevelt and implemented numerous reforms in the state of Utah, such as a Workmen’s Compensation Act, a Labor Organization Act, and a Public Utilities Commission. See Miriam B. Murphy, “Bamberger, Simon,” in Utah History Encyclopedia, originally published by University of Utah Press, 1994, https://

[23] Barnwell Relief Society, Barnwell History (Ann Arbor: Edwards Bros., 1952), 70. The Church appointed Peterson bishop of the Barnwell Ward in 1915, and he kept that position until 1925. See Barnwell Relief Society, Barnwell History, 145.

[24] Lethbridge Constituency, The United Farmers of Alberta (Inc.) Annual Report and Year Book containing Reports of Officers and Committees for the Year 1918 Together with Official Minutes of the Eleventh Annual Convention, 41.

[25] “Directors Are Chosen for the United Farmers,” Edmonton Bulletin, 25 January 1919, 1.

[26] Lawrence Peterson, “Lethbridge,” The United Farmers of Alberta (Inc.) Annual Report and Year Book containing Reports of Officers and Committees for the Year 1919 Together with Official Minutes of the Twelfth Annual Convention, 18.

[27] Peterson, “Lethbridge,” Year 1919, 18.

[28] “Cardston to Have Big Ware Houses,” Cardston Globe, 29 March 1919, 1. The Cardston District sold shares at $25 and limited investors to ten shares.

[29] Advertisement, Cardston Globe, 26 September 1919, 8. John Ford Parrish (1870–1957) was the business manager.

[30] Cardston Globe, 11 October 1919, 1.

[31] Lawrence Peterson, “Lethbridge,” 14 December 1921, Barnwell, in The United Farmers of Alberta (Inc.) Annual Report and Year Book containing Reports of Officers and Committees for the Year 1921 Together with Official Minutes of the Fourteenth Annual Convention, 25.

[32] Lethbridge Constituency, Year 1921, 66.

[33] “The Result,” Cardston Review, 21 July 1921, 4.

[34] Evan Annett and Jeremy Agius, “The PC Dynasty Falls: Understanding Alberta’s History of One-Party Rule,” Globe and Mail, published 5 May 2015 and updated 5 June 2017, https://

[35] “George L. Stringam, M. L. A. U. F. A. Candidate for Cardston Riding,” Cardston News, 12 June 1930, 1. See also George Owen Stringham, oral history, interviewed by Charles Ursenbach, Cardston, Alberta, 7 March 1974, transcript, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[36] Austin A. Mardon and Ernest G. Mardon, Alberta’s Political Pioneers: A Biographical Account of the United Farmers of Alberta 1921–1935, ed. Justin Selner, Spencer Dunn, and Emerson Csorba (Edmonton: Golden Meteorite Press, 2010), 140.

[37] Mardon and Mardon, Alberta’s Political Pioneers, 140. Peterson: 1,929 votes; J. J. Horrigan: 709; James Harper Prowse: 551.

[38] Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958), 293.

[39] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 354.

[40] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 383.

[41] William L. Woolf, oral history, interviewed by Maureen Ursenbach Beecher, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1972, transcript, Church History Library.

[42] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 293

[43] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 315.

[44] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 324.

[45] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 328.

[46] L. Dwight Israelsen, “United Orders,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 1493–95.

[47] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 341; Israelsen, “United Orders,” 1494.

[48] Israelsen, “United Orders,” 1494.

[49] Relief Society minutes, 11 June 1888, Cardston Ward Relief Society Minutes, 1887–1911, Church History Library.

[50] Willard and Bernice Brooks, “Cardston—Historic Firsts,” in Chief Mountain Country: A History of Cardston and District, vol. 2, ed. Beryl Bectell (Cardston: Cardston and District Historical Society, 1987), 2.

[51] Charles Ora Card diary, 27 June 1889, Charles Ora Card collection, MSS 1543, Nineteenth-Century Western & Mormon Manuscripts, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University (hereafter MSS 1543, Perry Special Collections). Also see Card diary, 15 July 1889, MSS 1543, Perry Special Collections. In Calgary, Card “looked about the Business houses for information that would be of benefit to our Co-operative Store at Cardston.”

[52] Card diary, 31 May 1890, MSS 1543, Perry Special Collections.

[53] J. Royal, Lieutenant Governor, N.W.T., Report concerning the Administration of the North-West Territories for the Year 1892, Annual Report of the Department of the Interior for the Year 1892 (Ottawa: S. E. Dawson, 1893).

[54] Card diary, 6 February 1891, MSS 1543, Perry Special Collections.

[55] Henry Wise Wood, speech, January 1924, U.F.A. President’s Address, Official Reports of the UFA Annual Convention, 1. UFA fonds.

[56] Wood, President’s Address, 2.

[57] “Southern Farmers Forming Local Wheat Pool,” U.F.A., 16 July 1923, 14.

[58] Wood, President’s Address, 2–3.

[59] W. J. Jackman, “A Wheat Pool for Alberta,” U.F.A., 16 July 1923, 1.

[60] Jackman, “Wheat Pool for Alberta,” 10.

[61] “The Wheat Pool Contract,” Edmonton Bulletin, 18 August 1923, 14.

[62] The United Farmers of Alberta Inc., Directors for 1922, Annual Report and Year Book containing Reports of Officers and Committees For the Year 1921 Together with Official Minutes of the Fourteenth Annual Convention, 87. See The United Farmers of Alberta Inc., convention minutes, 1924, scanned microfilm, UFA fonds. The United Farmers of Alberta Inc., convention minutes, 1935, scanned microfilm, UFA fonds.

[63] “Elect Trustees for Alberta Wheat Pool,” Redcliff Review, 23 August 1923, 1. See Raymond Recorder, 6 December 1945, 1.

[64] “Canadian Churchman Dies,” Church News, 1 February 1958, 1. “A Valued Citizen,” Lethbridge Herald, 23 January 1958, 4. Also see Lalovee R. Jensen, “History of Christian Jensen Jr.,” contributed by RS Ririe on 27 May 2013, https://

[65] “Co-operation in Alberta: Annual Meeting of Alberta Co-operative League,” Red Deer News, 11 June 1924, 2.

[66] “Campaign Launched in Lethbridge Districts in Preparation for the Annual Convention,” U.F.A., 15 December 1925, 18.

[67] “H. W. Wood Explains,” Cardston News, 4 February 1926, 2. “President Wood At Cardston,” U.F.A., 15 February 1926, 15.

[68] “The Aims of the U.F.A.,” Cardston News, 4 February 1926, 2.

[69] United Farmers of Alberta, How to Organize and Carry on a Local of the United Farmers of Alberta (Calgary: Office of the Provincial Secretary, 1920), 44. In addition, the United Farm Women of Alberta organized locals and regularly met to discuss their own agendas and follow their own programs.

[70] How to Organize and Carry on a Local, 45.

[71] Afton Keeler, transcript of talk about Christian Jensen, Magrath Museum, Magrath, Alberta.

[72] “Clyde and Inez R. Bennett Family,” Magrath Museum, Magrath, Alberta.

[73] “U.F.A. Sunday,” Western Independent, 12 May 1920, 1.

[74] The United Farmers of Alberta Inc., convention minutes, 1926, scanned microfilm, UFA fonds.

[75] “Liberal Rally at Owendale,” Cardston News, 24 June 1926, 6.

[76] “How Cardston Constituency Voted,” Cardston News, 1 July 1926, 1.

[77] “How Cardston Constituency Voted,” 1.

[78] “George L. Stringam Wins Farmers’ Convention Nomination,” Cardston News, 29 May 1930, 1.

[79] Thomas F. O’Dea, The Mormons (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963), 160.

[80] O’Dea, Mormons, 185.

[81] Nelson Wiseman, In Search of Canadian Political Culture (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007), 242.

[82] Banack, God’s Province, 123.

[83] Banack, God’s Province, 124.

[84] Samuel. B. Steele, Annual Report of Superintendent S. B. Steele, Commanding Macleod District, 1895, Sessional Papers of the Dominion of Canada : Volume 11, Sixth Session of the Seventh Parliament, Session 1896 (Ottawa: S.E. Dawson, 1896).

[85] Card diary, 14 January 1896, MSS 1543, Perry Special Collections.

[86] Card diary, 1 February 1896, 16 March 1896, and 21 March 1896, MSS 1543, Perry Special Collections.

[87] S. D. Clark, “The Religious Sect in Canadian Politics,” American Journal of Sociology 51, no. 3 (1945): 210.

[88] Card diary, 10 October 1901 and 24 October 1901, MSS 1543, Perry Special Collections.

[89] Banack, God’s Province, 27.

[90] Banack, God’s Province, 125.

[91] Banack, God’s Province, 214.

[92] S. D. Clark, The Developing Canadian Community, 2nd ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1968), 134–35, as cited in Wiseman, In Search of Canadian Political Culture, 246.

[93] Wiseman, In Search of Canadian Political Culture, 248.

[94] Earle H. Waugh, “The Almighty Has Not Got as Far as This Yet: Religious Models in Alberta’s and Saskatchewan’s History,” in The New Provinces: Alberta and Saskatchewan, 1905–1980, ed. Howard Palmer and Donald Smith (Vancouver: Tantalus Research Limited, 1973), 206.

[95] A. D. Sorensen, “Zion,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 1626.

[96] Waugh, “Almighty Has Not Got as Far as This Yet,” 207.

[97] Nathan B. Oman, “Mormonism and Secular Government,” in Mormonism: A Historical Encyclopedia, ed. W. Paul Reeve and Ardis E. Parshall (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2010), 331.

[98] Oman, “Mormonism and Secular Government,” 331.

[99] Oman, “Mormonism and Secular Government,” 331.

[100] Garth L. Mangum, “Welfare Services,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 1555.

[101] “1700 Hear Conference Speakers,” Cardston News, 12 July 1938, 1.

[102] Oman, “Mormonism and Secular Government,” 1.

[103] Raymond Recorder, 19 August 1938, 4.

[104] James Forest Wood, oral history, interviewed by Charles Ursenbach, Cardston, Alberta, 1974, transcript, Church History Library.

[105] John O. Hicken, oral history, interviewed by Charles Ursenbach, Raymond, Alberta, 1974, transcript, Church History Library.

[106] “Quarterly Conference,” Raymond Recorder, 15 July 1938, 1.

[107] First Presidency letter to Willard L. Smith, 5 February 1947, Raymond Alberta Canada Stake Manuscript History and Historical Reports, 1903–1975, Church History Library. Also in Octave W. Ursenbach papers, MSS 3116, Perry Special Collections.

[108] Myrtle N. Passey, “Myrtle N. Passey, 1939–1947,” Taylor Stake Relief Society History, 1962, Church History Library.

[109] Magrath 1st Ward Manuscript History and Historical Reports, 1899–1984, Church History Library.

[110] “Aetna,” Cardston News, 21 February 1939, 2.

[111] Minutes of a meeting of the Canadian Regional Welfare Committee, Magrath High School, 23 July 1939, Asael E. Palmer papers, MSS 6084, roll 1, box 1, folder 5. Twentieth-Century Western and Mormon Manuscripts, Perry Special Collections.

[112] Franklin L. Foster, “John E. Brownlee, 1925–1934,” in Alberta Premiers of the Twentieth Century, ed. Bradford James Rennie (Regina: Canada Plains Research Center, University of Regina, 2004), 97. For an explanation of why some CCF and UFA supporters voted Social Credit see Alvin Finkel, The Social Credit Phenomenon in Alberta (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1989), 22. For example, in a letter to member of Parliament George Gibson Coote (1880–1959), a CCF-supporting farmer indicated that many farmers were disillusioned with the UFA. In addition, UFA members proposed a Social Credit program before Aberhart established the official party so, when faced with a decision between CCF and Social Credit, some chose Social Credit. See Edward Bell, Social Classes and Social Credit in Alberta (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press), 16.

[113] Foster, “John E. Brownlee,” 97.

[114] Kenneth McNaught, A Prophet in Politics: A Biography of J. S. Woodsworth (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), 255.

[115] “Russell K. Homer Company (1858),” Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, https://

[116] Government of Canada, Census of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, 1916, Library and Archives Canada, http://

[117] Mable Johansen Palmer, “History of John Albert Johansen,” contributed by bethanykariannteerlink1 on 1 January 2014, https://

[118] “J. A. Johansen Nominated as Federal U. F. A. – C. C. F. Candidate,” Cardston News, 13 August 1935, 6.

[119] “J. A. Johansen Nominated,” 1.

[120] “C. C. F. Program Explained At Gym Meeting,” Cardston News, 8 October 1935, 1.

[121] “C. C. F. Program Explained At Gym Meeting,” 4.

[122] “Alberta Remains Social Credit,” Cardston News, 15 October 1935, 1.

[123] “C.C.F. Rally,” Cardston News, 30 March 1944, 1. Leavitt was patriarch of the Alberta Stake, he served a mission in Manitoba, and he was bishop of the Glenwood Ward for fourteen years, trustee and secretary of the first school board in Glenwood for four years, council man on the board of the Municipal District of Cochrane for eighteen years, reeve for eight years, and member of the United Irrigation District for thirteen years (chairman for three); from 1939 to 1945 he was chairman of the board and manager of the UID cheese factory. See obituary, 1958, contributed by Dave Olsen on 5 August 2014, https://

[124] “C.C.F. Rally,” 1.

[125] “Take a Step Forward with the C.C.F.,” Cardston News, 3 August 1944, 1.

[126] Yorgason, Transformation of the Mormon Culture Region, 127–28.

[127] Yorgason, Transformation of the Mormon Culture Region, 170.

[128] Yorgason, Transformation of the Mormon Culture Region, 170.