Ideological or Financial?

Academies or Seminaries and the Making of the Modern Church Educational System

Scott C. Esplin

Scott C. Esplin, "Ideological or Financial? Academies or Seminaries and the Making of the Modern Church Educational System," in Business and Religion: The Intersection of Faith and Finance, ed. Matthew G. Godfrey and Michael Hubbard MacKay (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 317–338.

At times in its history, interests of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints “seem especially rife with paradox,” observed scholar Terryl Givens. These tensions include some the faith shares with other religious movements, like the contrast between temporal and spiritual, Zion and Babylon, and authority and freedom. They extend to cultural practices as well, including, as Givens highlights, the arts and architecture. Indeed, “a field of tension seems a particularly apt way to characterize” our history.[1] As a practical example, the long story of education within the Church exhibits tension between the ideological and the financial.[2] Modern revelations dictated by Joseph Smith speak of God’s glory being intelligence (Doctrine and Covenants 93:36), command the acquisition of knowledge of things “both in heaven and in the earth” (Doctrine and Covenants 88:79), and declare “it impossible . . . to be saved in ignorance” (Doctrine and Covenants 131:6). Yet, the financial realities of a growing global faith challenge the Church’s ability to solely provide this education for all of its members. Can the Church, or should it, educate all its youth in faith-sponsored institutions? If the Church cannot educate all its youth in this way, how did it decide in the first decades of the twentieth century to educate some of them?

President Boyd K. Packer, as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, repeatedly spoke of the ideological and financial tensions that exist within Church education.[3] In the October 1992 general conference, he reviewed the history of Latter-day Saint education, including the early call for all to gather to Zion, the absence of public schools in the fledgling Utah territory, and the Church’s operation of its own schools to fill the void. “As public schools became available,” President Packer noted, “most of the Church schools were closed. At once, seminaries and institutes of religion were established in many nations. Some few schools are left over from that pioneering period, Brigham Young University and Ricks College among them.”

President Packer then revealed, “Now BYU is full to the brim and running over. It serves an ever-decreasing percentage of our college-age youth at an ever-increasing cost per student. Every year a larger number of qualified students must be turned away simply because there is no room for them. Leaders and members plead for us to duplicate these schools elsewhere. But we cannot, neither should we, attempt to provide secular education for all members of the Church worldwide. Our youth have no choice but to attend other schools.” He concluded, “The Church must concentrate on moral and spiritual education; we may encourage secular education but not necessarily provide it. . . . Unless you have the vision of the ever-growing millions of members all over the world, you may not understand why the Brethren make the decisions we make concerning Church schools.”[4]

President Packer is not the only General Authority to have openly reflected on the ideological and financial tensions at the heart of Church education. In his 1938 landmark address, “The Charted Course of the Church in Education,” President J. Reuben Clark of the First Presidency questioned if the correct decision had been made to abandon Church schools in favor of seminaries and institutes. Troubled by secular influences that were infiltrating religious education in his day, President Clark observed,

Our course is clear. If we cannot teach the gospel, the doctrines of the Church, and the standard works of the Church, all of them, on “released time” in our seminaries and institutes, then we must face giving up “released time” and try to work out some other plan of carrying on the gospel work in those institutions. If to work out some other plan be impossible, we shall face the abandonment of the seminaries and institutes and the return to Church colleges and academies. We are not now sure, in the light of developments, that these should ever have been given up.

President Clark reflected the tensions pulling at Church education in his day. “We are clear upon this point, namely, that we shall not feel justified in appropriating one further tithing dollar to the upkeep of our seminaries and institutes of religion unless they can be used to teach the gospel in the manner prescribed,” President Clark declared. “The tithing represents too much toil, too much self-denial, too much sacrifice, too much faith, to be used for the colorless instruction of the youth of the Church in elementary ethics. This decision and situation must be faced when the next budget is considered. In saying this, I am speaking for the First Presidency.”[5]

While debates over how to spend limited resources to educate the youth appear to permeate the ongoing story of Church education, the ideological and financial decisions that frame the discussion were made decades ago. The history of Latter-day Saint education during the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century demonstrates the establishment of priorities, the necessity for compromise, and the powerful pull of reality in shaping Church educational policy and practice.

Establishing the Church Academies

In 1880, at the height of the antipolygamy crusade aimed at reshaping Latter-day Saint society, US president Rutherford B. Hayes declared, “The [Utah] Territory is virtually under the theocratic government of the Mormon Church. . . . To destroy the temporal power of the Mormon Church is the end in view. . . . Laws must be enacted which will take from the Mormon Church its temporal power. Mormonism as a sectarian idea is nothing; but as a system of government it is our duty to deal with it as an enemy to our institutions and its supporters and leaders as criminals.”[6]

Among the laws enacted to reduce the Church’s grasp on territorial life were several targeting the region’s schools, which in the earliest decades of Utah’s history had been Church dominated. Congressional legislation dictated that federal appointees occupy administrative positions, control staffing and curriculum, and confiscate property to fund territorial common schools.[7] The legislation threatened the control the Church had over the instruction given the youth of the territory, and leaders reacted decisively. In April 1886 President John Taylor declared, “The duty of our people under these circumstances is clear; it is to keep their children away from the influence of the sophisms of infidelity and the vagaries of the sects. Let them, though it may possibly be at some pecuniary sacrifice, establish schools taught by those of our faith, where, free from the trammels of State aid, they can unhesitatingly teach the doctrines of true religion combined with the various branches of a general education.”[8]

Labeling public schools a “great evil,” President Wilford Woodruff acted on the call to establish separate schools.[9] President Woodruff formed the Church Board of Education in 1888, was appointed its president, and called for “one Stake Academy [to be] established in each Stake, as soon as practicable.”[10] Response to the charge was swift. In several instances, Church-sponsored schools opened in only four short months. Within fourteen months, twenty of the twenty-one stakes in Utah opened a stake academy.[11] By the end of 1891, all but four of the thirty-two stakes in the Church had an operating Church school.[12] With leaders like President George Q. Cannon directing that tuition charges be reduced in order to compete with free district schools and President Lorenzo Snow calling the Church school system “one of the most important factors in establishing the Kingdom of God upon the earth,” idealism reigned supreme in the newly formed Church educational system.[13] The model epitomized a late attempt at the separation and self-sufficiency that characterized the administration of President Brigham Young and eventually dominated much of nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint life. Patterned after economic and social responses to the completion of the railroad a generation earlier, isolationism and protectionism encompassed education.[14]

Financial Realities Imperil Church Education

While ideals like preserving faith and protecting youth dominated the founding of Church academies, fiscal realities quickly derailed it. An economic crisis swept the nation in the 1890s, catching the fragile Church schools in its grasp. The gravity of the situation was compounded by a region-wide drought, lingering effects from the seizure of Church assets during the antipolygamy crusade, and a corresponding downturn in tithing donations. Appeals for assistance flooded the Church Board of Education, who was financially unable to comply.

Reflecting on the fiscal realities the Church faced, President Woodruff wrote the Tooele Stake Board of Education shortly after the call to establish stake academies, “The Church feels the stringency of the times, and we do not receive anything like sufficient in the shape of tithing to enable us to meet our current expenses. . . . At the same time there is a feeling of liberality in the breasts of the brethren concerning schools. The cause of education, as is now proposed under the direction of these Boards, is one that lays very near to the hearts of the brethren, and they feel willing to strain a point to render aid, as soon as we can see our way clear to do so.”[15]

Despite their hopes, a brighter financial future failed to materialize. As early as 1891, President Lorenzo Snow “spoke of the difficulties, mostly of a financial character in the way of the establishment of these schools, advocating very strongly the necessity of the teachers laboring in a missionary spirit.”[16] By 1893 Church leaders were struggling to fund the system. Board minutes record the decision to “notify Stake Boards to take steps and make necessary arrangements to take care of, and pay expenses of Stake Schools and not look to the General Board for help other than the Annual Appropriations.”[17] In June 1893 board secretary George Reynolds wrote leaders of the Church’s Weber Stake Academy, outlining the fiscal reality: “I am directed to say that, at present, the General Board is entirely out of funds, having overdrawn its appropriation from the Church several thousand dollars, and the Church is not in a condition, just now, to make further appropriations.”[18]

Six years later, Reynolds informed the stake president in Thatcher, Arizona, “The appropriation to the General Church Board of Education by the Church for the present calendar year (1899) has already been divided up. I fear it will be a number of years before anything will reach you from that source. So small are the amounts divided that the Colleges at Logan and Salt Lake City both talk of closing, and at the Brigham Young Academy many of the teachers are arranging to work on a missionary basis.”[19] He likewise wrote the struggling Weber Stake Academy, “I am sorry I can send you no encouraging word. Nearly all the church schools tell me they will have to close at the end of the present school year if they do not receive more help. I presume it is certain that the college in this city will close with the present semester, and the institutions in Provo and Logan both talk the same way, if help from some quarter is not obtained.”[20]

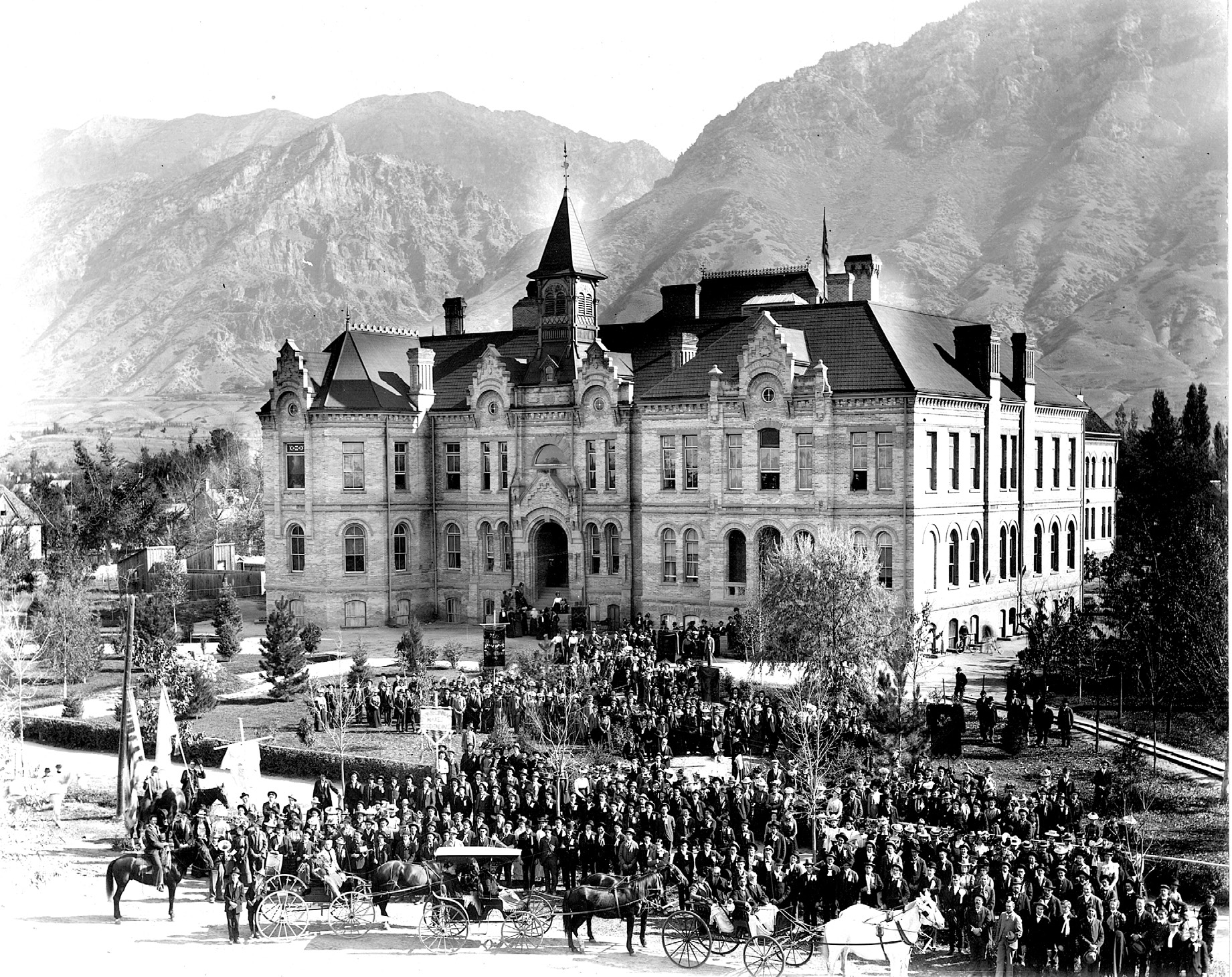

Brigham Young Academy, Provo, Utah, ca. 1900. Photograph by Charles Roscoe Savage.

Brigham Young Academy, Provo, Utah, ca. 1900. Photograph by Charles Roscoe Savage.

Reynolds’s premonition turned into reality. As early as 1893, Church schools in Morgan, Millard, Panguitch, Mount Pleasant, and Manti were shuttered.[21] Two years later, superintendent of Church schools Karl G. Maeser reported to the board, “Out of the forty church schools that had been organized since the establishment of our church school system only fifteen have been in operation during the last school year.”[22] Financial realities overwhelmed an ideological founding grounded in protectionism.

Emergence of Secular and Spiritual Alternatives

As the Church academies struggled against fiscal pressures to fulfill their founding vision, they also faced an alternative in the form of the growing high school movement. At the dawn of the century, only six public high schools existed in the entire state of Utah, with only the schools in Salt Lake City and Ogden boasting student populations exceeding sixty-five.[23] With the closure of most of the stake academies, public schools were subsequently established in Latter-day Saint communities all across the Intermountain West.[24] Public high school expansion in the region matched similar growth nationally, where secondary school enrollment in the United States exploded from 360,000 in 1890 to 2,500,000 in 1920.[25]

The growing number of public schools, coupled with higher academic expectations of educators, created a demand for trained teachers across the region. Complementing this need, several of the surviving Church academies, including Brigham Young University (Provo, Utah), Brigham Young College (Logan, Utah), Weber Normal College (Ogden, Utah), Snow Normal College (Ephraim, Utah), Dixie Normal College (St. George, Utah), Ricks Normal College (Rexburg, Idaho), and Gila Normal College (Thatcher, Arizona), were transformed into teacher training centers. With the encouragement of President Joseph F. Smith, state officials accredited the Church teacher training programs, accepting their graduates for public school teaching positions.[26]

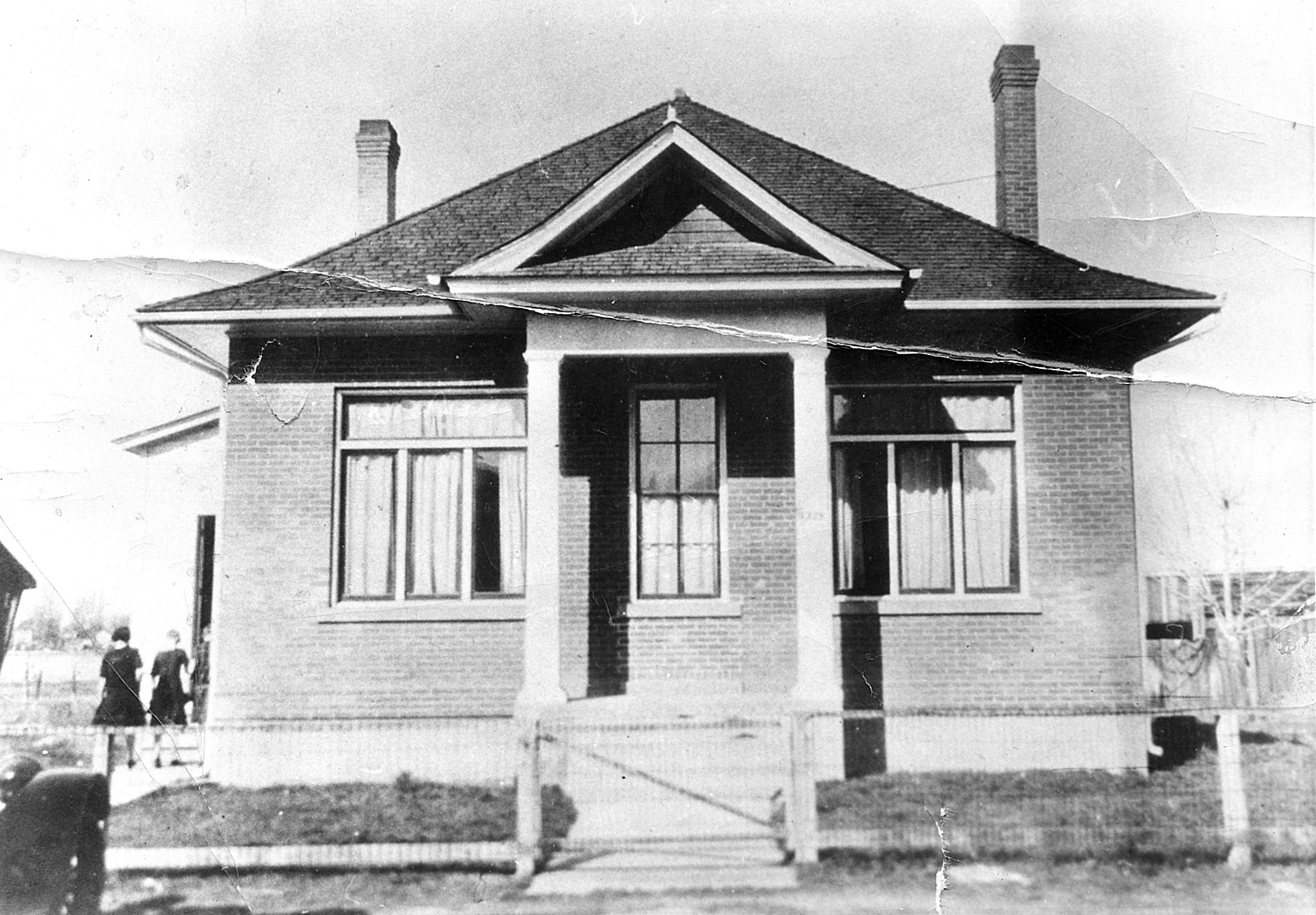

Granite High School Seminary Building, ca. 1912. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

Granite High School Seminary Building, ca. 1912. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

Additionally, to support Latter-day Saint youth attending public high schools, a released-time program known as seminary emerged. Beginning with an enrollment of seventy students at Salt Lake’s Granite High School in 1912, the program quickly expanded to twenty schools and over 3,200 students by the end of the decade. By 1930 nearly twenty-six thousand students were enrolled in seminaries across the region. The system also expanded to college-age youth through a program known as college seminaries or institutes of religion.[27]

Born of a desire to provide spiritual education for youth attending secular schools, the seminary system was also rooted in fiscal realism. As early as 1906, board discussions included “investigating whether or not a more economical and profitable use of the money expended on the Church school system could be made than at present.” Willard Young, president of Salt Lake’s Latter-day Saints’ University, observed, “If we had unlimited funds, the Church should have a complete system of schools; but not having unlimited funds, the thing to be sought for is how to do the most good to the greatest number with the means at our command.”[28]

While fiscal responsibility was one important issue facing Church leadership, equitable educational opportunities appear also to have been of grave concern. In June 1909 President Joseph F. Smith wrote on behalf of the rest of the General Church Board of Education to the leaders of Brigham Young College in Logan, “It is not the feeling of either of the committees, nor is it thought a wise policy by this Board to use from the limited money available the large sums that would be needed in giving college education to the comparatively few who are able to take it; but it is thought that this portion of the tithes of the people should be spent in making many Latter-day Saints of our children in high schools rather than a comparative few in colleges.”[29]

The seminary option that presented itself in 1912 proved to be the solution the board sought to equitably utilize limited resources. Minutes from the Church Board of Education meeting where the Granite Seminary was approved read, “Several of the brethren expressed themselves favorable to the movement, it being regarded as a good opportunity to start a new policy in Church school work, which, if successful, will make it possible to give theological training to the students of the State high schools at a nominal cost.”[30] Subsequent board minutes regularly report on the per-student savings of the seminary system over the Church schools.[31]

Debating the Merits of Church Schools or Seminaries

Though educational opportunities abounded for Latter-day Saints throughout the early 1900s, operating the expansive system overextended the Church financially. General Church appropriations for education skyrocketed. In 1909 Church officials expressed concern to the leadership of Brigham Young College. “Within less than a decade the annual appropriation for maintaining the Church schools has increased almost tenfold. This is altogether out of proportion to the increase of the revenues of the Church; a ratio that cannot longer be maintained.”[32] Inflating educational expenses greatly troubled Church leadership in the years that followed. Summarizing expenditures for the fifteen-year period from 1901 to 1915, President Joseph F. Smith reported spending $3,714,455 for schools, the largest expenditure in the entire Church budget for the time period.[33]

Church Board of Education minutes reflect President Smith’s growing apprehension regarding educational expenses. Responding to Weber Academy’s request for funding to expand teacher training, “President Smith,” according to the minutes of a 1915 meeting, “explained to the brethren the condition of the Church finances and clearly pointed out that the Trustee-in-Trust is in no position at present to promise an increase of funds for educational purposes. While he was heartily in favor of the idea of our turning attention to the making of teachers and would be very glad if some of the smaller schools could be turned into public high schools, to have the means thus saved expended for normal work, he did not see how he could undertake at present to branch out and incur more expense; we would simply have to trim our educational sails to the financial winds.”[34]

In October 1915 President Smith chose to make his concerns regarding educational expenditures public when he raised the matter in general conference. Knowing he would be “criticized by professional ‘lovers of education’ for expressing [his] idea in relation to this matter,” President Smith nevertheless remarked in his opening address at the gathering, “I hope that I may be pardoned for giving expression to my real conviction with reference to the question of education in the State of Utah. . . . I believe that we are running education mad. I believe that we are taxing the people more for education than they should be taxed. This is my sentiment.”[35]

The gravity of the Church’s financial state resulting from its commitment to education extended beyond President Smith’s administration. During the administration of President Heber J. Grant, leaders began seriously reconsidering their educational program. In a Church Board of Education meeting held in March 1920, commissioners of the Church Educational System observed, “It is manifestly impossible, under present conditions, to increase the number of academies, though not a few stakes are earnestly hoping that this be done. It is not an easy matter to satisfy these petitioners when they claim that other stakes more favorably situated as regards centers of learning than they, have the benefit of these educational courses. The limit of Church finances, however, has definitely limited the number of academies, but it does seem advisable that some plan should be devised that might have more general application than the present system.”[36]

Developing a financially viable plan with “more general application” came to dominate the discussions of those who led Church education for the next decade. Early in the 1920s, Church leaders decided to eliminate duplication of state education programs. Adam S. Bennion, superintendent of Church schools from 1920 to 1928, observed, “It became increasingly clearer that the Church could not and ought not compete against the public high school. . . . It became evident that when the public high school was established, the Church was in the field of competition. Such competition was costly and full of difficulties.”[37]

While openly acknowledging the need to eliminate competition, Church leaders also acted realistically. In 1920 Commissioner of Church Education David O. McKay warned, “We see clearly that continuing our present school policy, maintaining twenty-one schools and a seminary generally in connection with the public High Schools, is a policy that will inevitably bankrupt the Church.” He “expressed the view that up to this time the seminary has not been made a successful substitute for the Church School but expressed the opinion that if properly conducted the seminary can be made a successful substitute.” Accordingly, Elder McKay “proposed that all small Church Schools in communities where LDS influence predominates be eliminated and that we maintain four or five schools with the aim in view of giving first class training to teachers.”[38]

The first shift, announced in March 1920, was a transfer of selected Church academies to the state to be run as public high schools. By 1924 twelve Church-supported academies were either turned over to the respective states for operation or were closed.[39] The only schools remaining, aside from the Juárez Academy in Mexico, were those that had expanded to include some form of collegiate work.[40]

The Church colleges that were retained focused on teacher training. Commissioner of Education McKay reasoned that if Church normal schools were preserved, they could influence youth by supplying teachers for state schools. Elder McKay outlined, “So the policy is, first, to establish teacher training schools in centers accessible to the greater part of the Church; second, to place in the state high schools our own trained teachers, as far as possible, and then supplement that by the spiritual training in the seminaries.”[41] Elder McKay was not alone in his feelings. His successor as Commissioner of the Church Educational System, Elder John A. Widtsoe, noted as early as 1923, “The church schools will cost more than ever unless some check is interposed.” Accordingly, he proposed that “after the present year we begin to withdraw gradually from the high school field and leave it entirely to the state, and that we emphasize the strengthening of junior colleges.”[42]

But even this restructuring was not enough. At a board meeting in February 1926, President Grant revealed: “I am free to confess that nothing has worried me more since I became President than the expansion of the appropriation for the Church school system. With the idea of cutting down of the expense, we appointed three of the Apostles as Commissioners; but instead of cutting down we have increased and increased, until we decided a year or two ago that there should be no further increase. We decided to limit the Brigham Young University to $200,000. Last year that school got $165,000 extra for a new building, and inside of two or three years they expect a regular appropriation of $300,000, besides which they have plans laid out for new buildings involving an expenditure of over a million, if not a million and a half. Well, we can’t do it, that’s all.”[43]

Throughout March 1926, Church Board of Education officials debated the fate of the Church school program. The financial condition of the Church and the ideological value of the schools dominated discussions. Former Church educator Elder David O. McKay led out in the effort to preserve Church schools. “I think the intimation that we ought to abandon our present Church Schools and go into the seminary business exclusively is not only premature but dangerous,” Elder McKay warned. “The seminary has not been tested yet but the Church schools have, and if we go back to the old Catholic Church you will find Church schools have been tested for hundreds of years and that church still holds to them.” Championing Church schools, Elder McKay appealed, “Let us hold our seminaries but not do away with our Church schools.”[44]

In spite of Elder McKay’s pleas, the recommendation that the Church divest itself of nearly all its schools prevailed. Joseph F. Merrill, superintendent of Church schools and later a fellow Apostle, reported in 1928, “The policy of the Church was to eliminate church schools as fast as circumstances would permit.”[45] Offering Gila College to the state of Arizona, Merrill wrote, “The LDS Church does not care to go forward in the field of secular education.”[46]

Board minutes preserve how officials determined to expand the seminary model at the expense of the surviving Church-run academies and postsecondary institutions.[47] As the Board and its leaders worked to unwind the Church school system, financial realities weighed heavily in the decision. When some questioned if it was indeed “the policy of the Church . . . to eliminate Church schools . . . and to substitute for them seminaries and institutes,” President Charles W. Nibley of the First Presidency remarked that “according to his understanding the funds of the Church could no longer maintain both schools and seminaries and that since the per capita cost was something like ten to one in favor of the seminaries it was decided to eliminate the schools and establish seminaries.”[48] Reflecting later on the decisions that marked his tenure, Elder Merrill recalled, “The Church Board of Education and the Church’s leading educators and thinkers in many fields had long realized that Church-operated academies were a financial burden and were performing a limited service, geographically at least.”[49]

Facing financial arguments favoring seminaries over the continuance of Church schools, Elder David O. McKay sought, unsuccessfully, to bring the discussion back to the system’s ideological founding. “Did we do high school work merely for the purpose of doing high school work and because the State did not do it, or did we establish the schools to make Latter-day Saints?” Elder McKay asked.[50] He then admitted,

We have had two extreme views presented here—one favoring higher education with the hope of endowment, the other eliminating Church Schools entirely and going into the seminaries. I stand right between these two extremes. I am not in favor at all of spending money on higher education in Church Schools. We reach too few people, and I think religious sentiments are pretty well established before our people reach that stage. We can reach a far greater number by centering our efforts on the high school age and possibly the first two years of college; but I hesitate about eliminating the schools now established, because of the growing tendency all over the world to sneer at religion. When President Woodruff sent out his letter advising Presidents of Stakes to establish Church Schools, he emphasized that we must have our children trained in the principles of the gospel. We can have that in the seminaries, it is true, but he added this, “and where the principles of our religion may form part of the teaching of the schools.” President Young had the same thought in mind when he told Dr. Maeser not to teach arithmetic without the spirit of the Lord. The influence of our seminaries, if you put them all over the Church, will not equal the influence of the Church Schools that are now established.[51]

In spite of Elder McKay’s historical review, financial concerns and a desire to equitably serve more Church youth through supplementary religious education carried the day.

Conclusion

“The 1920s became the graveyard of church business ventures,” noted historian Thomas Alexander. This included the Church’s educational system, which “resembled nothing quite so much as a balloon. Expanding during the period to 1920, it shrank rapidly during the 1920s.”[52] The decisions that precipitated these changes, as well as the actions themselves, reflect the tension between the ideological and the financial so often evident throughout the history of the Church.

In its founding, the Church Educational System, with its corresponding network of stake academies, was an ideological stand against federal intrusion into education as well as a demonstration of a separationist and protectionist worldview. “That system of godless education has proven unsatisfactory, and we will have none of it,” decried general superintendent of Church schools Karl G. Maeser.[53] Announcing that “the time [had] arrived when the proper education of our children should be taken in hand by us as a people,” President Wilford Woodruff and his associates acted in the face of financial peril to provide for the spiritual and secular education of the youth of the Church.[54] However, financial realities and a changing church and state dynamic derailed the initiative, and only the largest, most established schools survived into the twentieth century.

A generation later, desires to provide spiritual education for public school youth drove the founding of the seminary system. In 1926 Rudger Clawson, president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, predicted, “The spirit of Church School work is a grand spirit and if the growth of it is to be met at all, I think it will be through the seminary movement, and the benefits will be very widely distributed.”[55] While his statement proved prophetic through the development of the modern Church Educational System worldwide, seminary growth came at the cost of the Church schools. Financial realities doomed the costlier of the two programs when Church school dreams were shuttered in the name of fiscal viability. In their place, a more equitable model emerged, fitted to face the financial headwinds of the Great Depression and, later, to follow the worldwide growth of the Church.

The story of Church education is the story of an ideological founding, fiscal realities, and practical reactions. Reflecting tensions that shape Church practice, it traces the replacement of an isolationist worldview with one more open to outside interaction. Emerging, phoenix-like, from each setback across its history was a new model, designed to teach more youth “of things both in heaven and in the earth,” preparing them to “magnify the calling [and] mission” they will be given (Doctrine and Covenants 88:79–80).

Notes

[1] Terryl L. Givens, People of Paradox: A History of Mormon Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), xiv.

[2] For an extended analysis of the philosophy underlying education in the Church and the educational context within which it emerged, see Scott C. Esplin and E. Vance Randall, “Living in Two Worlds: The Development and Transition of Mormon Education in American Society,” History of Education 43, no. 1 (Winter 2014): 3–30. This paper builds upon that earlier study by focusing on the financial aspects of Latter-day Saint educational practice.

[3] See Boyd K. Packer, “The Edge of the Light,” in Educating Zion, ed. John W. Welch and Don E. Norton (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, Brigham Young University, 1996), 165–76; Boyd K. Packer, “The Snow-White Birds” (Brigham Young University Conference, 29 August 1995), speeches.byu.edu.

[4] Boyd K. Packer, in Conference Report, October 1992, 98–100. In his address, President Packer cautioned, “We must not ignore these warnings in the Book of Mormon: The people began to be distinguished by ranks, according to their riches and their chances for learning; yea, some were ignorant because of their poverty, and others did receive great learning because of their riches. Some were lifted up in pride, and others were exceedingly humble; . . . And thus there became a great inequality . . . insomuch that the church began to be broken up” (3 Nephi 6:12–14).

[5] J. Reuben Clark Jr., “The Charted Course of the Church in Education,” Improvement Era, September 1938, 575.

[6] William Henry Smith and Charles Richard Williams, The Life of Rutherford Birchard Hayes, Nineteenth President of the United States (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), 2:225.

[7] Frederick S. Buchanan, “Education among the Mormons: Brigham Young and the Schools of Utah,” History of Education Quarterly 22, no. 4 (Winter 1982): 441.

[8] John Taylor, “An Epistle of the First Presidency to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in General Conference Assembled,” April 1886, in Messages of the First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1933–64, ed. James R. Clark (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965–75), 3:59.

[9] Wilford Woodruff, George Q. Cannon, and Joseph F. Smith, letter to stake presidents and bishops, 25 October 1890, in Clark, Messages of the First Presidency, 3:196.

[10] Wilford Woodruff to the Presidency of St. George Stake, 8 June 1888, cited in Clark, Messages of the First Presidency, 3:167–68.

[11] John D. Monnett, “The Mormon Church and Its Private School System in Utah: The Emergence of the Academies, 1880–1892” (PhD diss., University of Utah, 1984), 121.

[12] The four stakes without academies by 1891 included the Kanab, Maricopa, San Juan, and San Luis Stakes. The Maricopa Academy (Mesa, Arizona) opened in 1895 and the San Luis Academy (Manassa, Colorado) began operation in 1907. Researchers with Brigham Young University’s Education in Zion exhibit have identified as many as fifty-seven secondary and postsecondary schools operated by the Church from 1888 until 1933. Thirty-five of these schools were called stake academies. In addition, twenty-two other secondary schools existed, often called seminaries because a corresponding academy already existed in the stake. Finally, ten elementary schools, also called seminaries, were operated in Mexico during the early twentieth century. Less formally, some missions, including those in the Pacific islands, provided limited schooling as well. Brett Dowdle to Scott C. Esplin, email, 5 June 2008. Research for the Education in Zion exhibit, Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2008.

[13] Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 9 April 1889, General Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 1888–1902, UA 1376, box 1, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah (hereafter Perry Special Collections).

[14] See Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005); and Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1986).

[15] Wilford Woodruff to Hugh S. Gowans, 20 August 1888, correspondence, Church Board of Education letterpress copybooks, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[16] Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 2 June 1891, General Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 1888–1902, UA 1376, box 1, Perry Special Collections.

[17] Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 29 May 1893, General Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 1888–1902, UA 1376, box 1, Perry Special Collections.

[18] George Reynolds, letter to Joseph Stanford, 1 June 1893, Board of Education (General Church: 1888–1917) letterpress copybooks, 1888–1917, CR 102 1, Church History Library.

[19] George Reynolds to Andrew Kimball, 7 March 1899, correspondence, Church Board of Education letterpress copybooks, Church History Library.

[20] George Reynolds to L. F. Moench, 3 March 1899, correspondence, Church Board of Education letterpress copybooks, Church History Library.

[21] Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 11 August 1893, General Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 1888–1902, UA 1376, box 1, Perry Special Collections.

[22] Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 10 August 1895, General Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 1888–1902, UA 1376, box 1, Perry Special Collections.

[23] Emma J. McVicker, Third Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State of Utah (Salt Lake City: State of Utah, Department of Public Instruction, 1900), 25–26. The six public high schools in Utah were located in Salt Lake, Ogden, Park City, Brigham City, Nephi, and Richfield. The latter three only offered ninth and tenth grades, in conjunction with the earlier grammar grades.

[24] The 1902 state superintendent’s report counted nineteen public high schools in Utah. A. C. Nelson, Fourth Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State of Utah (Salt Lake City: State of Utah, Department of Public Instruction, 1902), 22.

[25] David B. Tyack, Turning Points in American Educational History (Waltham, MA: Blaisdell, 1967), 358.

[26] Joseph F. Smith to Utah State Board of Education, 5 May 1911, in William MS 7643, Peter Miller, Weber College (1888–1933), Church History Library.

[27] Seminary and Institute Statistical Reports, 1919–1953, CR 102 235, Unified Church School System (1953–1970), Church History Library; Church Educational System Historical Resource File, 1891–1989, CR 102 301, Church Educational System (1971–present), Church History Library.

[28] Church Board of Education minutes, 28 February 1906, box 23, folder 1, Centennial History Project Papers, UA 566, Perry Special Collections.

[29] Minutes of the General Church Board of Education, 30 June 1909, Centennial History Project Papers, UA 566, box 23, folder 7, Perry Special Collections.

[30] Church Board of Education minutes, 29 May 1912, General Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 1888–1902, UA 1376, box 1, Perry Special Collections.

[31] For example, Church Board of Education minutes for 7 March 1923 report “a per capita cost of $14.50,” for the 5,169 seminary students enrolled Churchwide at “about 1/

[32] Minutes of the General Church Board of Education, 30 June 1909, Centennial History Project Papers, UA 566, box 23, folder 7, Perry Special Collections.

[33] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, April 1916, 7.

[34] General Church Board of Education minutes, 27 January 1915, Centennial History Project Papers, UA 566, box 24, folder 8, Perry Special Collections.

[35] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, October 1915, 4.

[36] Minutes of the General Church Board of Education meeting, 3 March 1920, in Kenneth G. Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion: Superintendent of L.D.S. Education, 1919 to 1928” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1969), 52.

[37] Adam S. Bennion to Church Board of Education, 1 February 1928, Adam S. Bennion, Papers, 1909–1958, MSS 1, folder 8, box 6, Perry Special Collections. Statistically, public schooling in Church-dominated areas experienced a meteoric rise. In 1890, for example, public high schools in Utah enrolled only 5 percent of the state’s secondary student population. By 1924, 90 percent of all students attended public schools. Milton R. Hunter, The Mormons and the American Frontier (Salt Lake City: L.D.S. Department of Education, 1940), 223.

[38] Minutes of the Meeting of the Commission of Education, 24 February 1920, Centennial History Project Papers, UA 566, box 25, folder 7, Perry Special Collections.

[39] Seminary and Institute Statistical Reports, 1919–1953, CR 102 235, Unified Church School System (1953–1970), Church History Library.

[40] Schools that offered collegiate work included Brigham Young University, Brigham Young College, Weber College, Snow College, Dixie College, Ricks College, and Gila College.

[41] Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 15 March 1920, General Board of Education Minutes 1919–1945, D. Michael Quinn Papers, Uncat. WA MS.98, box 11, folder 4, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University Library; see also Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 15 March 1920, Scott G. Kenney Research Collection, MSS 2022, box 10, folder 4, Perry Special Collections.

[42] Minutes of the Church Board of Education, 3 January 1923, Centennial History Project Papers, UA 566, box 26, folder 4, Perry Special Collections.

[43] Minutes of the Church Board of Education, 3 February 1926, Centennial History Project Papers, UA 566, box 27, folders 2–3, Perry Special Collections.

[44] David O. McKay, Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 3 March 1926, Centennial History Project Papers, UA 566, box 27, folder 3, Perry Special Collections. See also Ernest L. Wilkinson, ed., Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), 2:73.

[45] Joseph F. Merrill, in Wilkinson, Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years, 2:85.

[46] Joseph F. Merrill, letter to H. L. Schantz, 1 February 1929, Joseph F. Merrill Papers, 1887–1952, MSS 1540, folder 3, box 5, Perry Special Collections.

[47] It is important to note that Elder Joseph F. Merrill, who oversaw the dismantling of the Church academy system, had been instrumental in the founding of the seminary alternative. He served as a counselor in the Granite Stake Presidency when the first seminary was formed at Granite High School. The idea for released-time religious education stemmed, in part, from Merrill’s experience with religious seminaries as a graduate student in Chicago and from witnessing his wife, Annie Laura Hyde Merrill, draw upon her religious training as a student of James E. Talmage at the Salt Lake Academy to teach their children. Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1986), 168; By Study and Also by Faith, 34–35.

[48] Minutes of the meeting of the General Church Board of Education, held in the President’s office, Salt Lake City, 20 February 1929, William E. Berrett Research Files, CR 102 174, Church History Library.

[49] Joseph F. Merrill, “A New Institution in Religious Education,” Improvement Era, January 1938, 12.

[50] Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 3 March 1926, Centennial History Project Papers, UA 566, box 27, folder 3, Perry Special Collections.

[51] Minutes of the Church Board of Education, 23 March 1926, Centennial History Project Papers, UA 566, box 27, folder 3, Perry Special Collections.

[52] Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 87, 157–58.

[53] Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 9 April 1889, General Church Board of Education meeting minutes, 1888–1902, UA 1376, box 1, Perry Special Collections.

[54] Wilford Woodruff to the Presidency of St. George Stake, 8 June 1888, cited in James R. Clark, ed., Messages of the First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965–1971), 3:167–68.

[55] Church Board of Education minutes, 23 March 1926, Centennial History Project Papers, UA 566, box 27, folder 3, Perry Special Collections.