The Great Cause

The Economics behind Construction of the General Relief Society Building

Mary Jane Woodger and Kiersten Robertson

Kiersten Robertson, "The Great Cause: The Economics behind Construction of the General Relief Society Building," in Business and Religion: The Intersection of Faith and Finance, ed. Matthew G. Godfrey and Michael Hubbard MacKay (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 355–394.

In the mid-twentieth century an entire building was built and dedicated to the Relief Society of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints at the heart of Temple Square. Like many Latter-day Saint chapels of the past, this building was financed independently, but in this case it was specifically financed by women. Previously, the General Relief Society administration had shared a building with the Presiding Bishopric.

In December 1945 the First Counselor in the Presiding Bishopric, Marvin O. Ashton, wrote a letter to General Relief Society President Belle S. Spafford regarding the financing and construction of this new Relief Society building. For thirty-five years, the Relief Society and Presiding Bishopric had been housed in the same building, and the Relief Society General Board was eager for the auxiliary to have headquarters of its own. In his letter, Ashton remarked:

May you speedily start, and may you speedily finish it. If we are perfectly honest with you, and sometimes we are, we would say something like this to President Spafford, “Success to you in this building,” and, as the host said to those guests he had in the house as he went into the closet to take out their coats, “Here’s your hat, but what’s your hurry?”

Our building over there is crowded. You need a new building and so do we need more elbow room. Success to you![1]

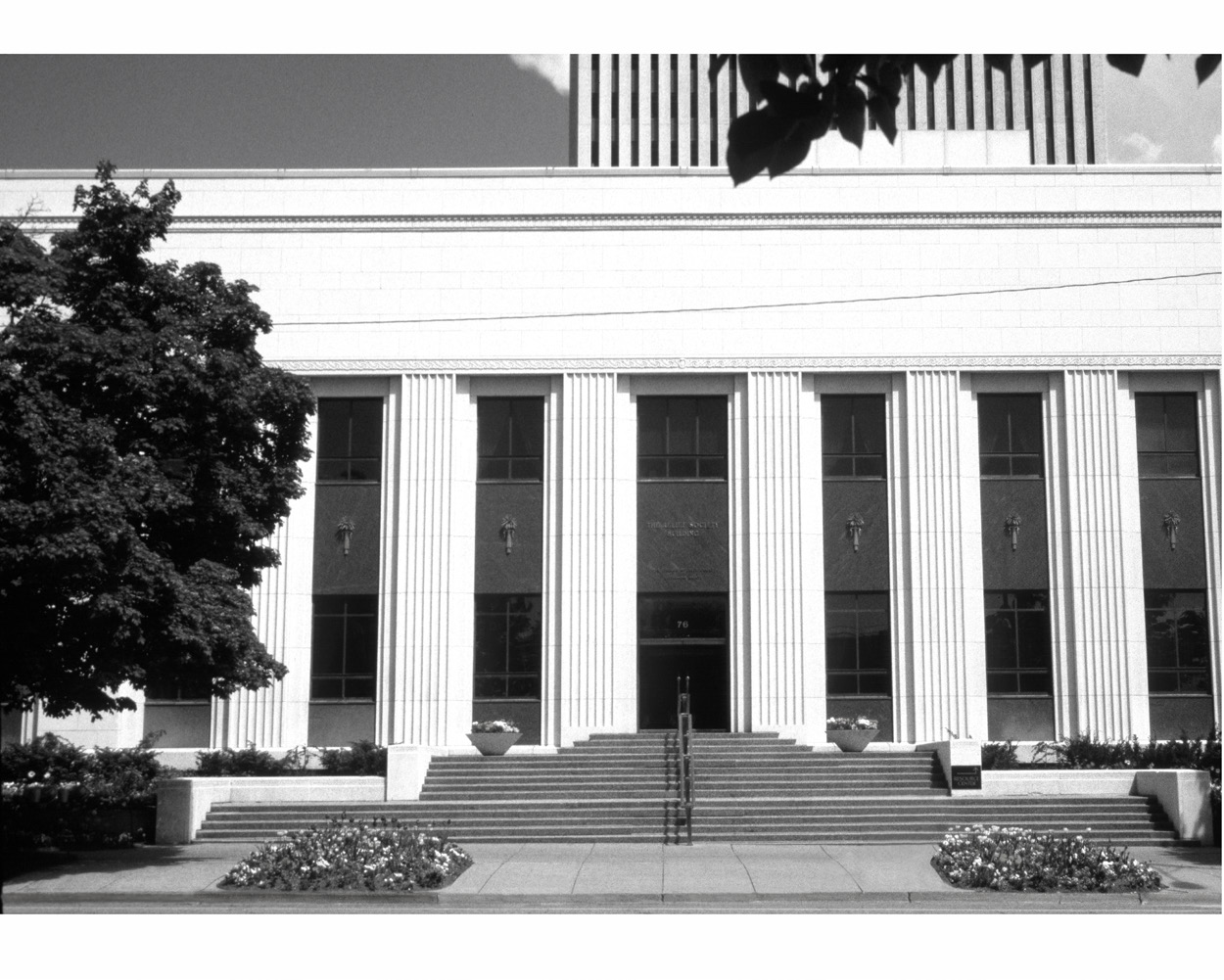

General Relief Society Building on the northeast corner of the temple block. Courtesy of the General Relief Society Presidency.

General Relief Society Building on the northeast corner of the temple block. Courtesy of the General Relief Society Presidency.

Ashton added, “I wish that every building that is financed would be financed as easily as you are going to finance this building; and I hope I have the privilege, and I am sure it won’t be denied, to give my pittance in this direction.”[2] Ashton touched upon a unique aspect of this project in his remarks to Spafford; the Relief Society building would be financed differently than any other building in the Church had been: it would be financed by women in the unique ways they typically generated income in the mid-1900s, through cottage industries, bazaars, dinners, and personal sacrifice. The unique financing and construction of this building represents the role of gendered religious fundraising in the governance of the finances of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The Foundation for a Building for the General Relief Society

When the Relief Society was first organized in the spring of 1842, its administration met within its own building. While in Nauvoo, Joseph Smith assigned the Relief Society “a lot belonging to the Church and a house on it which could be repaired and made useful.”[3] But the first General Relief Society building was short lived. As early as 28 April 1842, Joseph told the Relief Society that they “would not have his instruction long . . . that according to his prayers God had appointed him elsewhere.”[4] The doctrine and practice of plural marriage would eventually lead to the suspension of the Nauvoo Relief Society. As General President Emma Smith found the principle unsustainable, it caused disorder and disunity among the Relief Society sisters and the Brethren. Joseph had warned that “all must work in concert or nothing can be done.” Emma’s actions were out of harmony, and though during the 16 March 1844 meeting she announced her intent to call another, no further meetings of the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo ever took place.[5] When Joseph Smith was martyred and the Saints left Nauvoo, the Relief Society was abandoned along with their hopes of a building. Eventually the Relief Society was reestablished in December of 1866 with Eliza R. Snow as general president; however, it would be decades before the Relief Society again had a vision for their own building.

General Relief Society Building reflection pool, 2018. Courtesy of the General Relief Society Presidency.

General Relief Society Building reflection pool, 2018. Courtesy of the General Relief Society Presidency.

The abundance of temporal ventures by Utah women in the period of Eliza Snow’s presidency has been widely published, and nineteenth-century women also assumed part of the financial burden of constructing Latter-day Saint buildings, temples, and meetinghouses.[6] Each ward Relief Society would select projects, and each woman would determine her role in the project.[7] For instance, when the men who were working on the Logan Temple were discharged because there was no means to pay them, Jane S. Richards raised five hundred dollars in the Relief Society of Weber County to keep the men working.[8] There was a constant expectation that if the women helped with these projects, the brethren would in turn help them build a home for the Relief Society. During a Relief Society Jubilee celebration in 1892, Bathsheba W. Smith told the sisters, “We have helped the brethren, and now think it only fair for them to help us build a hall for ourselves.”[9]

While women cooperated with men on these projects “that basically the men directed, the men did assist the sisters in projects of their own as well,” such as when Relief Society women began to provide their own meeting places.[10] Relief Society Halls, as they were known in the early days of the Church, provided a home for Relief Societies. By way of illustration, Eliza R. Snow, encouraging the Relief Societies in Weber County to build their own hall, assured them that if they, “with the sanction of the brethren, undertake to build a house, the brethren will help them.”[11] Ward Relief Society presidents seemed to take the leading role in these projects. For example, in the Fifteenth Ward Relief Society of the Salt Lake Stake, President Sarah M. Kimball herself designed the building and then hired a contractor to frame a sixteen-by-thirty foot Relief Society Hall.[12] As Susa Young Gates, founder of the Relief Society Magazine, informs,

From the beginning of the Relief Society work in Utah the women were encouraged by Eliza R. Snow and her associates to build small halls for their meetings. . . . Oftentimes the halls were built near the Ward meeting houses, or the women would buy a piece of land or have a piece given them by some generous bishop or elder. . . . A partial report from twenty-three stakes in 1893 gives us an acknowledged total of twenty nine Relief Society Ward Houses or halls with estimated additions of thirty more. The women did all the business connected with this whole enterprise and we much conclude that the training in public enterprises was of far more value to all concerned than any financial returns or possessions.[13]

Eventually, Relief Society Halls were abandoned in 1921 when the Presiding Bishopric encouraged societies to cease building their own halls and move into ward meetinghouses, where a Relief Society room would be provided instead.[14]

Ironicically, while most wards’ Relief Societies provided their own meeting places during this time period, the general officers of the three women’s organizations were still meeting in rented rooms. The Relief Society was headquartered in the Woman’s Exponent offices, rented from editor Emmeline B. Wells.[15] In addition, there was no place available to preserve General Relief Society records.

With the goal of a home of their own in mind, at the General Relief Society Conference held on 3 October 1896 in the Assembly Hall on Temple Square, General Relief Society President Zina D. H. Young and her vice presidents (as they were called at the time) First Counselor Jane S. Richards, Second Counselor Bathsheba W. Smith, and Third Counselor Sarah M. Kimball discussed the possibility of a new meeting place. Young envisioned “a home of the heart of Relief Society of which every Relief Society member is a part. A home containing the loveliest offerings of the world-wide sisterhood.” “We want to have a house where the Relief Society could receive strangers and impart information,” Kimball told the sisters as she declared that “she felt it a humiliation to be without a place of our own; we had contributed to all public places and at all times. Now we want to have a house and we want land to build it on and it should be in the shadow of the temple.” Kimball then asked those who were present, “Do you want such a building as I have described?” The motion was then put to a vote, and the vote was unanimous in the affirmative.[16]

Entrance to the General Relief Society Building. Courtesy of the General Relief Society Presidency.

Entrance to the General Relief Society Building. Courtesy of the General Relief Society Presidency.

In 1900 the Relief Society received help when the Young Ladies Mutual Improvement Association and the Primary Association joined forces with the Relief Society, hoping the three auxiliaries together could raise enough money for a suitable “Women’s Building” for all three organizations. Under the leadership of the general auxiliary presidencies, women quickly began to establish female independence in relationship to financing the building and to display typical gender roles in fundraising. They raised money in culturally relevant ways for their time period and participated in Church finances as they had many times before as moneymakers. Whereas men would ultimately control the finances for operating the Church, female general presidencies would control the design of this building and the strategy for moneymaking activities. The design for the building as envisioned by the presidencies included “kitchens, pantries, banqueting hall, cooking utensils, a furnace and closets and a room for the janitor, and offices upstairs, with library and bureau of information.” This library was to “be in the best sense educational, and be open to all members of the society, and where lectures may be given by distinguished professors in all branches of science, art and literature, and on general topics.”[17]

In a meeting with stake Relief Society presidents at the October 1900 general conference, a fundraising program was launched when letters were sent to ward Relief Societies asking them to appropriate one-third of their cash on hand as a beginning.[18] Then in a united front, the auxiliary leaders presented the matter to President Lorenzo Snow in March 1901. The women had considered buying land, but were elated when the First Presidency offered them a lot directly across the street east of the temple. President Lorenzo Snow told them that when they had $20,000 raised toward the building, he would give them the deed. They could be assured that this would take place; the secretary noted his words that they could be as sure “as you will be of happiness when you get to heaven.”[19] With the donation of the building lot, the construction project became a joint venture between the Church and the Relief Society; however, the promise was that the partnership would only be temporary until the deed was turned over to the Relief Society and the Church would thereby relinquish control.

Four months later, on 9 July 1901, President Snow in an address given at the Saltair Resort stated,

I understand that one of the objects of this excursion is to raise funds toward the proposed Woman’s Building in Salt Lake City. . . . I have as Trustee in Trust, contributed a choice piece of land facing the Temple of God, on which to erect a structure that will be suitable headquarters for the Relief Society, Young Ladies Mutual Improvement Association and the Primary Association. I felt it was right and proper that you should have a building in which you could do your business, receive representatives from branch societies and distinguished visitors from abroad, hold council meetings and for various other purposes, and it gave me much pleasure to aid you to the extent of furnishing a beautiful site for the buildings. . . .

I am glad to note that you are making strenuous exertions to raise the requisite means for this purpose, and if you are all united and liberal in your feelings, I do not think you will find it a hard task. I would encourage every member of these organizations to assist in this work. I would also invite every Bishop to assist you in obtaining sufficient means to erect a magnificent edifice that shall reflect credit upon our women and attract the admiring gaze of the great and noble of all who may visit Zion. . . . You are now 30,000 strong I am told, with a building fund of nearly $5,000, and with upwards of $100,000 worth of property in your possession. . . . The Relief Society has been and is one of the most valuable adjuncts to the Priesthood. It is in very deed a help in government.[20]

With the phrase President Snow used in this address that the Relief Society was a valuable adjunct to the priesthood and a help in (Church) government, one might suggest that he was not seeing the funding and construction of the Relief Society as a separate financial entity controlled by women. Rather, he was suggesting that the part the Relief Society was playing in the project was as an assistant to the men who were really in charge. This statement seems to contradict the earlier phrase in the same address where President Snow suggested that he was merely aiding the Relief Society and not the other way around. These two contradicting statements show the balancing act female leaders were teetering with, being unsure whether they were in charge or the Church was.

Just one month later, in August, General Relief Society President Zina D. H. Young passed away, and just two months after that, President Lorenzo Snow also died. New president Joseph F. Smith then called Bathsheba W. Smith to succeed Young as Relief Society President, and the plans for a Relief Society building continued under her administration.

By the 1901 October general conference, fervor for raising funds was increasing. For instance, Eliza M. Oram of Pocatello, Idaho, said, “The sisters were liberal in contributing towards the Woman’s Building,” and Adelia Crosby of Panguitch, Utah, noted that “the sisters seem very willing to assist.”[21] Records show various amounts donated in a steady stream from individual women: some gave fifty cents, some a dollar—the amounts were recorded in the cash book of the building fund. In 1902 Pres. Bathsheba Smith wrote,

The sisters in all the Stakes of Zion are aware of the intention of erecting a woman’s building suitable for meetings and other purposes to be owned and controlled equally by the Relief Society, the Y. L. N. M. I. A., and the Primary Associations. Money has been voluntarily donated from the Relief Society and deposited in Zion’s Savings Bank for safe keeping and to accumulate interest thereon during the time of waiting to commence the structure. Meantime our sisters of the Relief Society are expected to continue donating according to their circumstances; no change having been made in the intention of having a place for women’s organizations and the intent is still to gather sufficient means to defray all expenses, before the building is commenced. The Relief Society will take such steps in the matter of building as are advised by the First Presidency of the Church; and all who have donated money will be duly notified when the time comes to lay the foundation, and commence the work. We who preside over the Society fully appreciate the spirit of liberality in which the sisters have contributed heretofore, and not one cent of their money will be made use of for any other purpose than the building.[22]

For the next five years contributions continued to pour into the Relief Society fund, until $14,005 had been raised by the three women’s organizations. “Then disturbing rumors reached the ears of President Bathsheba Smith that their plans had been shelved. A letter to the First Presidency asked if it were true, that they were not to have their building. Word came back: the rumors were true. A Presiding Bishop’s building was to be built on the lot they had been promised and would incorporate within it the women’s offices.” Upon hearing this development, Smith was “overcome with grief.”[23] Subsequent general board meetings were highly emotional, though the minutes simply record, “some members felt very much grieved over the way matters stood.” The board felt they were betraying donors in that they had “pledged to those who had contributed the money for a building that was to be their own.” The reason for the drastic change was not given, and the conversation at the next board meeting must have been heated, for as historians Jill Mulvay Derr, Janath Russell Cannon, and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher detail in their book Women of Covenant, “The following week’s minutes included the revealing comment that ‘some unnecessary paragraphs [have been] expunged from previous minutes.’”[24]

The decision to change the Relief Society Building to the Bishop’s Building was fraught with unkept promises from Joseph Smith to Lorenzo Snow. With the auxiliaries being well on their way to having the required $20,000, it must have been baffling. It was not what they had expected. They considered objecting but then decided to acquiesce and comply with the First Presidency’s decision. Sisters explained the change in various ways. Annie T. Hyde of the Bannock (Idaho) Stake “spoke of the woman’s building; said they were going to join with the brethren in building the house.”[25]

Susa Young Gates suggests some plausible reasons for the building’s ownership change that may or may not have been discussed with the auxiliary presidencies:

For a number of years, the Relief Society had been gathering funds for the erection of a Woman’s Building. In 1910, the Church erected a building on So. Temple St. which was to provide headquarters for all Latter-day Saint women’s associations. After consultation it was thought best for the Presiding Bishop and his staff to occupy the lower floor; in order that heavy overhead expenses of such a building might be bourne [sic] by the Church itself; so that when finally completed the women were given the three upper floors of the building, the Bishops occupying the first floor. This was wise, as a Woman’s separate Building would have taxed their financial resources to carry it on. All the Church Charity work was a double duty to be shared jointly by the Bishops and the Relief Society. The Presiding Bishops at this period were given direct supervision of Relief Society activities. The close association with the presidency and priesthood thus formed has proved of infinite value to the woman’s organization.[26]

This situation is indicative of how things were handled with Church finances and in the individual lives of woman in the early twentieth century. Though the women had been the movers and shakers in raising the funds and designing the building, the priesthood would ultimately have the decision-making power. These women had been empowered to raise money, but they were not given the autonomy to ultimately control the funds that they had raised. Although President Bathsheba Smith had seen that the “Relief Society is designed to be a self-governing organization,” in this instance the Relief Society was governed by a higher organization.[27] Fortunately, a later generation would see the fulfillment of the promises made to their mothers. A generation would pass before both the finances between the Relief Society and the Church and the finances between men and women would evolve, before the Relief Society would truly be able to self-govern their own finances and have their own building.

Though the Relief Society had donated $8,000 toward the construction of the building and was given rooms within it, the building was to be known as the Presiding Bishop’s Building rather than the General Relief Society Building. The edifice was completed in January 1910 and sat in the shadow of the temple at 40 North Main Street in Salt Lake City.

Despite disappointment, the new Relief Society accommodations were found to be adequate and were “appropriately and tastefully furnished.”[28] The Relief Society “had a second floor suite consisting of a large reception room with a president’s office adjoining, an office for the secretary, and a committee room.”[29] “It is the first time in all its history,” editorialized the Women’s Exponent, “where the General Society has had rooms for the transaction of business pertaining to the great work of this, the first and largest organization of women in the Church.”[30] On 21 January 1910, six days before the building’s dedication, the Relief Society held its first event in its new quarter: a celebration of the 106th anniversary of Eliza R. Snow’s birth. Women spent the evening discussing Snow’s memory.[31] Gates tells us of the benefits of the Relief Society being housed in the Bishop’s Building, which included the location for centralized activity; a spacious hall for public meetings; really comfortable rooms and appointments; no rent; no running expenses; private offices for the president of the Society, the secretary, and the editor of the magazine; business offices for the manager of the magazine; a Burial Clothes Department; a Social Welfare Department; offices for the clerks and stenographers; and a large council room for the Board’s weekly meetings.[32]

Still, this accommodation in the Presiding Bishop’s Building did not quench the Relief Society’s desire for a building of their own, one that would “beautifully and adequately represent the women of the Church. This desire, born and nurtured in the past, [was still] firmly rooted in [their] hearts.”[33]

Between Two Buildings

During the time the Relief Society was headquartered in the Presiding Bishop’s Building, it increased in membership, influence, and power. For instance, during the Great Depression, visiting teachers collected donations for their ward’s Relief Society charity funds, which provided funds for emergency relief and other purposes. There began to be more communication of such activities between bishops and those women working under their direction. “This closer cooperation between Relief Society and the bishops led to a more unified welfare program in the wards and paved the way for the shift to a church welfare program in 1936.”[34] Subsequently, a new welfare department was added to the responsibilities of the General Relief Society Presidency along with new welfare department offices in the Presiding Bishop’s Building. Larger office space was also needed for the evolution of social services and an ever-expanding General Relief Society Board.

With the onset of World War II, Relief Society sisters became entrenched with activities to support war efforts. This is well illustrated by Leone O. Jacobs, who served in the Ensign Stake Relief Society presidency. Jacobs, along with other Ensign Stake Relief Society members, worked during the war “in sending soap, clothing, and bedding overseas; supporting the American Red Cross’s Utah headquarters by sewing hospital gowns and bandages; and filling canning assignments at Welfare Square. Materials were scarce, so the Relief Society had to be resourceful and act quickly to buy supplies to make blankets, clothing, and other items when such dry goods became available. Members pooled their gasoline ration stamps while Jacobs, the only presidency member with a car, drove them on their expeditions to look for fabric.”[35] Most Relief Society sisters were as involved as Jacobs was with the war effort and had little interest in building a new home for the organization. During the war there was also a restriction on holding General Relief Society meetings because of the rationing of gas and other commodities. As President George Albert Smith asked sisters in 1945, “Do you realize that you have opened this tabernacle to the first general conference we have had in years?”[36] Rationing also contributed to building restrictions during the war. The Relief Society could not have built a new edifice legally even if they had decided to.

The war brought about cultural changes in that generation of Latter-day Saint women as it did for all women. Many more women began working outside the home while men served in the armed forces. This development brought about more independent Latter-day Saint women who were on more of an equal financial footing than their predecessors.

Post–World War II and the Relief Society Building

When the war ended in 1945, a postwar assessment of Relief Society revealed that “membership had dropped from 115,000 in 1942 to fewer than 102,000 in 1945. Visiting teaching and attendance had declined because of gas rationing, shifts in population, and increased numbers of women working away from home.” However, by 1946, the trend had already begun to reverse.[37] The Relief Society’s 1946 annual report included statistics from the Danish, French, Swedish, and Swiss-Austrian missions, the first statistics to come from Europe since 1938 when the war began. By 1947, reports also came from Czechoslovakia, East Germany, and the Netherlands missions. The Relief Society was recovering from the war and preparing for the future. With this progress, it seemed the right time to renew the dream of a building dedicated exclusively to the Relief Society. As Spafford later said, the building could only come “when the nations should still the guns of war.”[38]

And so, at the first postwar conference, in October 1945, General Relief Society President Belle Spafford called for a vote on a proposal to erect a Relief Society building to “more adequately house the general offices, the Temple-Burial Clothes Department, the Magazine, the Welfare, and other departments. . . . Like one great wave, thousands of uplifted hands unanimously voted in the affirmative.”[39] Spafford remarked two months later in December 1945, “As we are [entering] upon a second century of Relief Society, a strong and growing organization rich in the blessings of the Lord, this seems the right and appropriate time to bring to fruition this dream of the past, to erect a building that shall stand as a monument to Latter-day Saint women and a credit to the Church.”[40] Vesta P. Crawford, associate editor of the Relief Society Magazine, explained:

The Relief Society Building will be a home for this great women’s organization—a center place, from which direction and counsel and information will go forth. It will be a gathering place for the sisters—a home of ideals, and hopes, and sisterhood. It will be the administration building for the society, and it will be a symbol of Relief Society women of the past, of this day, and of the days to come. This building, in history, will be that precious “centerpiece” for the daughters of Zion, housing for them their heritage, their days of service upon the earth, and the bequeathing of Relief Society to their daughters.[41]

However, crossing some of the sisters’ minds must have been their efforts in 1902–1907, when they had raised $8,000 for what became the Presiding Bishopric’s Building. At a 1948 conference, in reference to the disappointing outcome of that first attempt to raise funds for a Relief Society building, the narration of a special recording made for the event stated, “We’ve appreciated the offices, yes. But you know how you feel when you’ve been living with relatives and then get a chance to move into a home of your own.”[42] The link with the earlier group of women who raised money for their own building was always present, and memories long retained would haunt the planners. At one time, Spafford told of an unusual visit to her office:

A woman in her eighties had traveled from Southern Utah, walked up the stairs of the Bishop’s Building because she was afraid of elevators, and approached President Spafford with her five-dollar contribution to the new building. “Although we’re glad to meet you,” quizzed Sister Spafford, “it was not necessary. . . . Why didn’t you give it to your ward Relief Society?”

“I have another little matter that I need to take up with you,” the woman countered. “Several years ago one of the Relief Society presidents raised money for a Relief Society building, and I paid five dollars then. And I want to know what became of my other five dollars.” Sister Spafford explained how the Relief Society had contributed to the Bishop’s Building, had been housed there rent-free, and would now receive back the money they had contributed in the first place.

“Do you mean that the Brethren are going to give us back our money?” the woman sputtered, incredulous.

“Yes, exactly,” returned Sister Spafford. “You have contributed ten dollars to this building.”

“You know, I’m glad I came!” responded the woman as she left. “I’m glad to know the Brethren are honorable men.”[43]

The $8,000 that had been raised by Relief Society sisters in 1906 was indeed returned to the Relief Society.[44] The Presiding Bishopric, somewhat acknowledging their benefit from the profits of the original fundraising of the Relief Society, sent the following letter to all stake presidencies and ward bishoprics on 6 November 1947:

We are enclosing herewith copy of letters mailed by the General Presidency of the Relief Society to the stake and ward Relief Societies outlining their plan for financing their proposed new building which, as you have already been told, and as indicated in the correspondence, has the approval of the First Presidency of the Church.

The Relief Society, as you brethren will all agree, is one of the great organizations of this Church. It has accomplished a great work in the past. It is accomplishing a greater work at the present time. The little support that is requested from the Relief Societies of the Church to make possible this beautiful new home which will be a monument to their achievements and add dignity and prestige to their standing for many years, and possibly centuries, to come, justifies every possible support of the bishoprics of the Church. It is for this reason that we are sending you this information that you may be advised of their program and that you may do all you can to see that the suggestions they have made are enthusiastically and promptly carried out in your wards. [45]

The letter was signed by LeGrand Richards, Joseph L. Wirthlin, and Thorpe B. Isaacson, the members of the Presiding Bishopric.

Financial Plan for the Relief Society Building

In that October conference of 1945, in which President Belle Spafford called for a vote on a new Relief Society building, newly appointed President George Albert Smith, addressing members of the Relief Society, made the following observation:

If you are going to have a house large enough to hold yourselves from now on, you may as well plan to build it. I am delighted to know that you are thinking of erecting such a structure.

Don’t you think it would be appropriate for you women of the Church of Jesus Christ, the only Church that bears his name by divine authority, to have a home of your own into which you could invite the spirit of the Lord when you hold your meetings? I realize you have been disappointed in the past; you thought you had a house once before, but it turned out to be the Presiding Bishop’s office also. But now your prospect seems to be better, and as you think about it and plan for it, you will be very happy. I don’t care how fine it is, how large it is, or how beautiful it is; it will not be better than you deserve. There isn’t anything too good for you as long as you keep the commandments of the Lord. . . . I am thinking today of the desirability of a house that will be the headquarters for the Relief Society of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. You may be sure that if you do your part, the Lord will do his. I am sure it will be a satisfaction to some of you who do not have homes of your own to know that there is a house in which you have some interest where you can meet and have enjoyment in the company of your sisters. It will be a gratifying experience for the daughters of Zion to feel that they have been able to provide themselves a suitable home, and that day is not far away.[46]

With the Prophet’s approval, Spafford quickly made plans for such a house as President George Albert Smith described. A committee for overseeing the construction of the Relief Society Building consisted of Velma N. Simonsen, Edith S. Elliott, Evon W. Peterson, Mary J. Wilson, and Leone G. Layton, with Marianne Sharp as chairwoman.[47] Under Spafford’s direction, the committee quickly prepared a financial plan to present to the new First Presidency.

The committee’s financial plan, prepared by 25 August, consisted of a year-long fundraising campaign that would commence on 2 October 1947 and close with Relief Society general conference in October 1948. Each local organization within the stakes was responsible for submitting a sum of money equal to five dollars for each member enrolled in the Relief Society, which would be transmitted to the General Board by 31 December 1948. Any deficits were to be made up from accrued earnings of the worldwide Relief Society or from cottage industries conducted by Relief Society sisters themselves, such as bazaars, dinners, concerts, and the sale of handmade goods.[48] Non–Relief Society members were welcome to participate if they desired. Any excess contributed was to cover contingencies, furnishings, and equipment. To meet any additional costs, the General Board hoped that members and nonmembers alike would contribute amounts larger than the quota. They also encouraged families to join together in making memorial gifts for loved ones, deceased or living. According to the detailed financial plan, these special gifts or contributions would not be counted toward the quota for each ward.[49] Branch Relief Societies and Church missions (except for those in Europe, which were struggling to recover from World War II) were expected to participate in the fundraising in accordance to the advice of their presiding leaders.[50]

When presented with the financial plan, Relief Society women immediately began thinking of creative ways they could raise money in cottage-industry fashion. One ward made money by quilting, another sold handmade articles at each Relief Society meeting. Another ward provided a food table where busy housewives could purchase homemade delicacies for supper, and various Relief Societies hosted concerts or parties to which members could bring their quotas.[51] By placing individual responsibility on each sister to raise funds, the General Board hoped that each would feel involved in the building construction and have a sense of stewardship and ownership of the building. One woman in Toronto, Canada expressed the value she placed on the Relief Society and her willingness to contribute to such a project. She wrote:

Now that the great University of Relief Society is to have a new home, I am grateful to send my small portion.

We Latter-day Saint women have been attending free of all tuition for over a hundred years.

It’s almost fifty years since I became an active member. I have known and listened to all the general presidents since Eliza R. Snow.

All my days I have been indebted to the host of great women who have shared their faith and teachings with me, all for the love of the gospel and their sisters of all races and creeds.

Nowhere on earth, even today, do women have the rich opportunities that are offered by our Relief Society, on such a broad cultural and spiritual basis. Many valiant ones who have had little formal schooling, because of Relief Society, are in the forefront of all the fine development that goes to enrich our lives here and hereafter.[52]

Sacrifices made by individual members of the Relief Society were at the heart of financial fundraising. On the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the building, General Relief Society President Bonnie D. Parkin observed that “she often watches women gather in the building for various reasons [and thinks] ‘Do they know the sacrifices that were made to build this building?’”[53]

The financial plan also placed responsibility on local leaders, emphasizing that stake Relief Society officers were responsible to the General Board to oversee collections from each ward or branch. Stake officers were prepared to accept all contributions, seeing that proper credit was given to the ward or branch for each sister that was a member.[54] In addition, as reported in the 1946 annual report, each stake was to contribute one half of the total amount of its cash on hand in the stake board funds. Each stake board was responsible for seeing that the full amount assigned to the wards within the stake was turned over to the General Board.[55]

Concerned that contributions were recorded appropriately, the General Board asked ward and stake Relief Society leaders to keep meticulous records. Many used creative methods to chart their progress. One ward built an arch twined with electric lights; each time a member paid her quota, a new light would come on. Another ward made a model of the building that was outlined with neon lights in proportion to the donations made.[56]

The financial plan also detailed other record-keeping devices. The General Board suggested that ward Relief Society leaders purchase an ordinary receipt book at a stationery store to record each time a Relief Society sister contributed a small amount toward her quota. The secretary-treasurer was to note each contribution on the back of the receipt. The financial plan describes in detail how quotas were to be written down and sent in to the General Board. Reports were to be made every two months to keep the General Board advised of progress. Wards and branches were to submit these reports to the stakes, and then the stakes were to submit their reports to the General Board by the twentieth day of December, April, June, and August. A final report would be specified at a later date in October 1948. Forms for the preliminary bimonthly reports were to be done in duplicate, with the white copy submitted to the Board and the colored copy retained by the stake. The names of the contributors were to be sent to the General Board, including the name of the ward, the quota, the amount of the quota remitted, the amount of the quota remaining, the amount of special and memorial gifts, the amount allotted the stake board, and so on. The women made a concerted effort to ensure that the entries in the financial section of the stake and ward record books were complete and accurate, including columns provided in a ward record book and a stake record book.

Visiting teachers were the volunteer force that kept the fundraising of the Relief Society Building afloat. As discussed in Women of Covenant, “Visiting teachers provided the vital communication system, publicizing the drive for funds, distributing supportive letters from bishops, and collecting donations. In many wards they distributed small containers, with the suggestion that they be left in a conspicuous place to encourage all family members to donate extra change. As their quotas were completed, wards and branches received recognition in the Relief Society Magazine.”[57] The names of all contributors were to be recorded by the Society accepting the contribution, and that record would be filed with the permanent records of the Society and inscribed by the General Board to be placed in the cornerstone of the building.[58]

This very detailed financial plan was sent to the First Presidency by the General Relief Society Presidency on 25 August and received their approval as follows:

We acknowledge your letter of August 25, in which you ask permission to have Sister Spafford announce the financial plan, as approved, for a new Relief Society building, setting out the details of a fund-raising campaign of one year, the campaign to end at the Relief Society General Conference in 1948.

We are happy by this letter to give you this authority and we wish for you a most successful campaign. We have never known the sisters to fail in anything they have undertaken in the past and we feel sure they will not fail in this.[59]

With the support of the First Presidency, the construction of the Relief Society Building was officially sanctioned and the proposed financial plan was adopted.[60] The Relief Society planned to raise an unheard-of $500,000, which in 2017 dollars would equal nearly seven million dollars. Considering the economic effects of World War II, it seemed an impossible undertaking.[61] However, Spafford was clear that this building would not only serve the generation that would raise the money, but it would also link past and future Relief Society women. She instructed:

This building program is not ours alone; it belongs to the past and it will belong to the future. In this magnificent achievement the women of this day have kept faith with the noble women of the past by opening the way whereby their dream may be brought to fruition. They have nobly and generously fulfilled the great special assignment given to the women of this Church. They have set a worthy pattern of loyalty and obedience for Relief Society women of the future, and those who follow after them will remember their efforts and bless them for what they have done.[62]

For Church News journalist, Julie Dockstader Heaps, the Relief Society Building symbolized “the rising of the sisterhood of [S]aints throughout the world and the healing of [the] postwar world,” for the more than one hundred thousand women who would donate five dollars each, as well as for their daughters and granddaughters.[63] Vesta P. Crawford, associate editor of the Relief Society Magazine, expressed, “Even as the walls of their home building rise in the mountain valley—over the wide reaches of the world, in many lands, the work of the beloved sisterhood will progress and the message and the spirit and the power of its inspiration will spread.”[64] As the fundraising began, it was a “testament also of the hopes and aspirations of the women who set their hands to the erection of a home for themselves.”[65]

Building Design

Belle Spafford described her vision of the building in October 1945, which included her desire that the building belong to women of the Church and that every Relief Society women would feel the “pride of ownership.” Spafford envisioned that it would not just be an office building but rather the edifice would provide a place where all Relief Society members could rest in the lounge rooms or “write a letter, or meet a friend; check rooms where you may leave your bundles; a relic room where choice articles of historic value may be preserved and displayed; an auditorium with well-equipped work and exhibition kitchens where homemaking demonstrations and lectures may be given, as well as other features suitable to a Relief Society building and the work of the Society.”[66] With Spafford’s vision in mind, the First Presidency stated in a letter to Spafford, dated 3 October 1952, that they had approved the Relief Society Presidency’s suggestion to erect the building on the northeast corner of the temple block, in front of the Joseph Smith Memorial Building.[67]

After the First Presidency’s location approval, the General Relief Society Presidency promptly requested plans from architect George Cannon Young, who would later design Primary Children’s Hospital and contribute to the Church Office Building, the North and South Visitors’ Centers on Temple Square, and the restoration of the Lion House.[68] It was important to the Relief Society General Board that the building represent a female personality and the Relief Society’s goals.[69] In the April 1948 issue of the Relief Society Magazine, the General Relief Society Presidency suggested that the sisters who contributed would “have a feeling of pride in the beauty and magnificence of the Church office building when we visit there or take our out-of-town friends to see the building.”[70] Spafford’s desire was that it would be a building that would “beautifully and adequately represent the women of the Church, one that should be a symbol to all people of the lofty position accorded faithful daughters of our Heavenly Father in the gospel plan.”[71]

The building plan called for a larger Temple-Burial Clothes Department, Relief Society Magazine offices, and a Social Service Department. Details were included. Restrooms and checkrooms would be made available—they had not been before. The plan also included an auditorium for demonstrations, as well as a room to house significant Relief Society artifacts. It was to be a building belonging to the women of the Church in which their work would be properly carried on—a monumental building, a beautiful building, as well as an administrative building.[72] Spafford called the type of building they needed “a mammoth undertaking,” requiring the full support of every member of the Relief Society.[73] This building would not just be a place to house leaders or to conduct the administration of the auxiliary; it was to be a symbol for every woman who participated or would participate in the Relief Society, and most especially for those who would participate in the financial plan.

Pride in Participation

The Board also suggested that the sisters’ pride of ownership would increase over the years: “Most of us have at times heard someone say with pride that he contributed to or assisted in the building of one of the temples. It will be just as great a source of joy for each of us to be able to say, ‘I helped in the building of this wonderful Relief Society building.’”[74] Throughout the history of the Church, Relief Society women had helped build temples and had donated to stake tabernacles, ward meetinghouses, and other Church buildings, generally raising funds for these edifices, as women do, from such methods as cooking, serving dinners, or hosting bazaars that required weeks and months of tedious preparation. As their circumstances and conditions allowed, they also furnished and beautified those buildings for the Church.[75] As Spafford related in a letter to Relief Society presidents, “There are but few buildings in the entire world erected by and for women, and it is eminently fitting that the women of the true Church should be thus represented.”[76]

The decision was made to work intensively for one year in fundraising, even at the cost of the Relief Society setting aside other projected fundraising programs. “Every effort must be bent toward the accomplishment of this one great undertaking,” Spafford remarked in December 1947.[77] During general conference held in the Tabernacle, an official representative from each of the stakes and missions would be recognized when their area fulfilled their quota, and an announcement would be made of the amount of money that had been collected.[78]

As was previously mentioned, the Presiding Bishopric gave its support by sending all stake presidencies and ward bishoprics a copy of the General Relief Society’s letter about the fundraising plan, “that you may be advised of their program and that you may do all you can to see that the suggestions they have made are enthusiastically and promptly carried out in your wards.”[79] This desire for women to take ownership and feel pride as part of raising and donating money, was transferred to individual sisters and individual Church units throughout the world. The following excerpt comes from a letter from one of the missions where sisters were feeling such ownership:

Many favorable reports have come from the branches concerning their share in this project. The sisters have expressed a keen desire to be a part of this great drive and to feel that they will actually own a part of the building. This feeling is akin to owning one’s own home. The example has inspired smaller groups to own and furnish their own Relief Society room where before they were content to meet in a hall or a home. Many ways and means are being employed to raise the money. These projects alone will knit the women more closely and will bring about a feeling of unity.[80]

Cottage Industries

For Spafford, the emphasis on generating funds through local cottage industries would reflect how Latter-day Saint women of the past had contributed to the building up of Zion. In a letter to Relief Society presidents dated 21 October 1947, she stated, “Just as Relief Society women of the past century gleaned in the fields to gather wheat and we today enjoy the fruits of that labor, so we call upon the sisters at this time to labor in this great cause so that the sisters of tomorrow and during all the years to come may be benefitted.”[81] The great bulk of the money came from individual donations earned by sisters through what was referred to as the “close and dear friend of Relief Society—‘Hard Work.’”[82] The sisters’ earnings were gained in ways different from their male counterparts. For instance, Alice Hobson Paul contributed her five dollars by raising chickens and selling eggs. Her granddaughter related, “My grandparents weren’t rich or wealthy. They were just ordinary people. For them back in those days, for her to come up with $5 was just extremely difficult.”[83] Many women sold bread, cakes, pies, flowers, aprons, and other items of clothing. Many wards delayed gathering funds until after the Christmas season.[84] In one case, a sister saved nickels and dimes, meaning her donation to be the ultimate Christmas gift. Others put off a personal purchase. It was the golden wedding anniversary gift for another. Many donated dollars represented the labor of individual sisters’ hands—aprons made, cakes baked, evenings spent caring for a baby, or days given to domestic service.[85]

Other missions, stakes, and wards joined together to meet the individual quotas. A letter written by a Sister Brinton, the stake Relief Society president in the Maricopa, Arizona, Stake explained that her stake was unique because it contained both an Indian and a Spanish ward. Brinton was worried that the building fund would be an especially undue hardship for sisters in these wards. In response to her concerns, Stake President Lorenzo Wright suggested that these wards hold a banquet. Arrangements were made. A bishop gave twenty-five dollars; the former president of the stake, Harold Wright, donated all the cake for the dinner; and others donated chickens. Sisters in the two wards “made many beautiful articles to be sold: Four quilts were appliqued, one pieced, baby quilts, aprons, dresses, dish towels, hot pad holders, and many other useful things.”[86] The sisters held meetings to create these items—some of them walking three miles to attend. Martina Schurtz, the Papago ward Relief Society president, lived in Mesa and worked at a dry cleaners. She missed work every Monday to attend these meetings. That meant that she gave up eight dollars a week, or thirty-two dollars a month, to attend Relief Society. Two elderly sisters who were nearly blind made pot holders on a frame. “Sisters helped plan the dinner, helped with the cooking and serving.” In typical Relief Society fashion, Mutual Improvement Association girls (or girls in what is now the Young Women organization) wearing white blouses with dark skirts and crepe aprons served the meal. The YWMIA president planned the program, which included “violin solos, duets, quartets, stories, and Indian dances.” It lasted over an hour and was “all Indian and very fine.” Commenting on the program, Brinton remarked that “it was well worth the money without the dinner.” The wards had planned on serving two hundred people, but almost three hundred attended, allowing the wards to send $135 to the General Board, which met their quota.[87]

The year from October 1947 to October 1948 was filled with much sacrifice and many achievements as women earned money for this great cause. One touching example is that of Annie Forrester Willardson, who at the time was a member of the Hollywood Ward in the Los Angeles Stake. Annie had been almost blind for several years. At the age of eighty-three, she wrote a check for her contribution. As she did so, the pen slipped out of her hand, leaving her signature unfinished. With the help of her daughter, Della Mortensen, Willardson was able to complete her signature. She passed away soon after making her contribution—it was one of the last acts of her life.[88]

Even the General Relief Society made its contribution. Years before the fundraising campaign, one of the General Authorities had written a series of articles for the Relief Society Magazine. The General Board later compiled these articles in a book form as a reference. The royalties from the book were supposed to go to the General Relief Society, but in November 1948 the earnings were earmarked to meet necessary expenses incidental to the building fund.[89] As quotas were met and individual units responded, it became clear that the individuals who participated felt a sense of pride and accomplishment.[90]

Relief Society Records Will Shine Forever

An October 1948 article in the Relief Society Magazine observed, “The Relief Society as part of the Church makes painstaking records and carefully preserves them, and out of Relief Society record books will shine forever bright the devoted and unselfish services of the women of the Church in the Relief Society Building Fund program of October 1947 to October 1948.”[91] The records for the program meticulously acknowledged every contribution made for the Relief Society Building.

Years later, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the dedication of the Relief Society Building, names of contributors, taken from the original handwritten record, were digitized for a permanent recorded history. Emma Artimissa Butler, who participated in the project, said she felt an incredibly strong connection to the sisters who contributed to the construction of the building and hoped to find her own mother’s name among the list of donors. On 6 March 2006 she did find the name of her mother, Rosamond Maxfield. Regarding their family’s personal circumstances during the year that her mother donated, Butler remarked that during the lean postwar times her mother, father, and the six children lived in a four-room house with no modern conveniences. In addition, during the fundraising period two brothers served missions and another joined the Marines. Her father worked three jobs and her mother worked part-time. To pay their quota for the Relief Society was “an incredible drain on our family’s income.” Butler stated that, “In retrospect, I have often thought how difficult this time of life must have been for my beloved parents and yet, how faithful they were to the gospel.”[92]

The General Relief Society Board was also careful in their reporting of donations and expenditures. In 1948, Marianne C. Sharp announced in the Relief Society Magazine that the interest on the funds in the banks for the past year had amounted to $211. In that same article entitled “And What of the Promise?” Sharp also reported that the five-dollar contribution quotas from the stakes amounted to $443,885, and that money contributed by missions’ quotas equaled $43,937, with a grand total of $554,016 donated to the Relief Society Building Fund.[93] Regarding expenditures, Sharp included the following report of the expenses that were incurred to raise money for the fund:

Postage 156

Stationery 27

Printing 758

Financial Clerk 735

Inscription on Certificates 234

Foreign Exchange 148

Total $2,058[94]

In December 1947 Spafford wrote, “In the Book of Psalms we are told: ‘The righteous shall be held in everlasting remembrance.’ The gospel of Jesus Christ teaches us to hold in sacred remembrance the righteous who have gone before us, to search out their names.”[95] The incredible record keeping of the Relief Society fulfilled an everlasting remembrance of those righteous who had gone before and made the building possible.

Building and Furnishing

As the sisters gathered for the 1948 Relief Society general conference, they came rejoicing. The great goal of half a million dollars had been reached and exceeded by nearly $70,000. The Church had previously agreed to match the Relief Society funds to $500,000. Since the building still needed to be furnished, the General Board asked the First Presidency if they would match the collected funds, including accrued interest and reserve funds, to a total of $100,000, thus allowing $200,000 for furnishing, equipment, and any overrun on the building. The First Presidency agreed to match the additional $100,000.[96]

And so, the construction of the building went forward. On 1 October 1953, ground for the building was broken, with Spafford turning a shovelful of dirt.[97] “Countless important decisions incident to the erection and furnishing of the building, and the management of the trusted funds” were all accomplished by women on the Relief Society General Board.[98]

1830 Meissen Vase donated by Austrian Relief Society sisters for the General Relief Society

1830 Meissen Vase donated by Austrian Relief Society sisters for the General Relief Society

Building. Courtesy of the General Relief Society Presidency.

Although the Europeans could not send money to contribute to the Building Fund due to strict laws following World War II, they did send objects.[99] As Sarah Dockstader Heaps observed, “these sisters from formerly war-torn countries . . . sent gifts to beautify the building.”[100] Indeed, “many of the exquisite furnishings, lamps, tables, vases, paintings, needlecraft, wood-carvings, pieces of sculpture work, models of ships, canoes, etc., dolls and figurines, as well as books for the library, desk sets, cabinets, etc. have been gifts to the building,” either from individuals, families, stakes, missions, or other groups.[101] These gifts represented many nations, both large and small, where women were affiliated with the Relief Society organization. Some gifts represented the native skills of women in their homelands, and these items became a treasure trove for the Relief Society.[102]

Deep-Seated and Tender Emotions

On 3 October 1956, President David O. McKay offered the dedicatory prayer for the new edifice. The event was held in the boardroom (which now serves as the president’s room), with a direct wire transmitting the service to the Tabernacle, where Spafford was conducting Relief Society general conference.[103] President McKay’s dedicatory prayer included mention of the careful financial planning and the unique way the Relief Society Building had been funded. Regarding those who had donated, McKay prayed, “Their devotion to duty is never-ending; their loyalty to Thee and to Thy Priesthood unquestioned; their administrations to the sick and to the needy, untiring; their sympathetic, gentle services give hope to the dying, comfort and faith to the bereaved.”[104] The dedicatory prayer continued,

The Relief Society has erected with the aid of the Church membership this beautiful Relief Society home in which the Presidency and members of the General Board may function more effectively in instructing, guiding, and rendering helpful aid to the Stakes, Wards, and Missionary Branches wherever organized.

To aid in the erection of this edifice, in its utility and beauty, contributions have come from individuals and groups in Nations throughout the world wherever the Church is organized.

For their generosity, self-sacrifice and love of a glorious Cause, O Lord, bless the givers fourfold.[105]

During the dedicatory services, Spafford, in speaking of the achievement of funding the building, shared that the “achievement represents deep-seated and tender emotions—the love of a daughter for her mother or grandmother; the love of a mother for her daughter; respect and devotion for a friend; the desire to memorialize a loved one whose memory is revered; the wish to reach out and include as a part of this wonderful sisterhood a dear one who may not have availed herself of this blessing.”[106]

In 1976, as noted on the official Temple Square Blog, “the building’s purpose was expanded as it became a resource center for Relief Society women of the Church in fulfilling their home and Church responsibilities through lectures, workshops, programs, displays and classes.” The old dream of the Relief Society, Young Women, and Primary auxiliaries being housed in one building was realized in 1984.[107]

The Role of Women in Church Finances as Exemplified by the Relief Society Building

The story of financing the General Relief Society Building is a fascinating look at fundraising and the economic issues in the Church that are tailored to gendered economic programs. The process by which the Relief Society Building was finally brought to fruition emphasizes the role of gendered religious fundraising, which facilitated female independence. If men were to have raised the funds for a self-sponsored building their gendered activities would have been completely different and maybe not as successful. The initial pairing of the Presiding Bishopric and the Relief Society is interesting in that the Church predominantly empowered men to do Church finances, and at the same time were trying to empower women to control the finances of the construction of the building. This pairing was eventually dissolved when President George Albert Smith let the women completely control the financing of their own building.

The interaction between General Relief Society President Belle Spafford and male leadership, most especially President George Albert Smith, can be viewed as an example of gender dynamics where soft power was used by female leaders. Soft power is defined as “the ability to get what one wants by attraction and persuasion rather than coercion or payment.” Soft power is the ability to shape the preferences of others through appeal and attraction, and the currency of soft power is culture. Recently, the term has also been used to describe changing and influencing social and public opinion through relatively less transparent channels and lobbying through powerful political and nonpolitical organizations.[108] In many instances, Spafford used soft-power strategies. Her emotional, persuasive approach talked of the culture of ideals, hopes, dreams, and sisterhood. The building itself was spoken of as a home rather than an office building, and Spafford helped to shape the preference that the building would stand as a monument to Latter-day Saint women. Her noncoercive soft-power approach used ingenuity, strength, and service rather than a hard-power approach of coercion. The timing of this gender dynamic was critical in that the cultural shift brought about by World War II placed Spafford and her General Relief Society Board in a more independent and influential social position with their male counterparts.

As Crawford indicated, the Relief Society represents the unified activities of females, as well as their ingenuity, strength, and service. These qualities are evident in how women successfully financed their own building through cottage industries, personal sacrifice, and teamwork. Indeed, the Relief Society Building serves as a monument to one generation’s ability to finance and raise money.

When the sisters realized they had a dream, they saw it all the way through, from the planning and fundraising, to the construction and furnishing. It is a tribute to Relief Society women that such a great feat was accomplished with relative ease. Through their unique financing and fundraising, the Relief Society women brought about “a home of the heart of Relief Society of which every Relief Society member is a part. A home containing the loveliest offerings of the world-wide sisterhood. Unitedly, through sacrifice . . . the Relief Society Building stands an ensign to women.”[109]

Notes

[1] Marvin O. Ashton, letter to President Belle Spafford, December 1945, as cited in “Success to a Relief Society Building,” Relief Society Magazine, December 1945, 753.

[2] Ashton, “Success to a Relief Society Building,” 753.

[3] Marianne C. Sharp, “Dream for a Relief Society Building,” Relief Society Magazine, December 1945, 749.

[4] Relief Society General Board Minutes, 1842–2007, typescript, 28 April 1842, LDS Church Archives, CR 11 10, as cited in Jill Mulvay Derr, Janath Russell Cannon, and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher, Women of Covenant: The Story of Relief Society (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992 ), 62.

[5] Relief Society General Board Minutes, 1842–2007, typescript, 16 March 1844, LDS Church Archives, CR 11 10, as cited in Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 62.

[6] The economic enterprises of the Relief Society has been the subject of scholarly articles and theses. See Leonard J. Arrington, “The Finest of Fabrics: Mormon Women and the Silk Industry in Early Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 46 (Fall 1978): 376–96; Sherilyn Cox Bennion, “Enterprising Ladies: Utah’s Nineteenth Century Women Editors,” Utah Historical Quarterly 49 (Summer 1981): 291–304; “Lula Greene Richards: Utah’s First Woman Editor,” BYU Studies 21 (Spring 1981): 155–74; and Jessie L. Embry, “Relief Society Grain Storage Program, 1876–1940” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1974). Papers dealing with women’s involvement in business, medicine, and education, presented at a 1982 conference of the Utah Women’s History Association, were published as John R. Sillito, ed., From Cottage to Market: The Professionalization of Women’s Sphere (Salt Lake City: Utah Women’s History Association, 1983).

[7] Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 98.

[8] Relief Society Minutes, 1892–1911, 3 October 1896, as cited in Sharp, “Dream for a Relief Society Building,” 749.

[9] Relief Society Minutes, 1892–1896, 6 April 1893; 5 April 1894, as cited in Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 142.

[10] Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 98.

[11] Eliza R. Snow, 14 August 1873, “An Address,” Woman’s Exponent 2 (15 September 1873): 63; Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star 34 (13 January 1874): 20.

[12] Sarah M. Kimball, “Duty of Officers of Female Relief Society,” Fifteenth Ward, Salt Lake Stake, Relief Society Minutes, 1868–1873, as cited in Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 99.

[13] Susa Young Gates, “Women in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints: How the Prophet Joseph Smith Opened the Gate Beautiful to Women,” transcription, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Archives, MS 7692, box 88, fld., 11, 20.

[14] Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 242.

[15] Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 174.

[16] Relief Society Minutes, 1892–1911, 3 October 1896, as cited in Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 174; Sharp, “Dream for a Relief Society Building,” 749.

[17] Sharp, “Dream for a Relief Society Building,” 749.

[18] Zina D. H. Young et al. to Mrs. E. L. S. Udall, 2 November 1900, St. Johns Stake Correspondence, Relief Society Headquarters Historical Files, as cited in Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 174.

[19] Relief Society Minutes, 1892–1911, 26 March 1901, as cited in Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 174.

[20] Lorenzo Snow, “Address Given at Saltair,” 9 July 1901, cited in The General Relief Society, Officers, Objects and Status: Minutes of First Organization, Biographical Sketch of Pres. Bathsheba W. Smith, General Instructions (Salt Lake City: The Deseret News Print, 1902), 20.

[21] “General Conference Relief Society,” Woman’s Exponent 30 (December 1901): 55–56; and Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 175.

[22] The General Relief Society, Officers, Objects and Status, 91.

[23] Bathsheba W. Smith, Martha H. Tingey, and Louie B. Felt to the Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 23 January 1907, First Presidency, General Administration Correspondence, Church Archives; Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 175.

[24] Relief Society Minutes 1892–1911, 1 and 15 February 1907, as cited in Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 175.

[25] “Relief Society Reports, Bancock Stake,” Woman’s Exponent 36 (October 1907): 30.

[26] Gates, “Women in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints,” 10.

[27] The General Relief Society, Officers, Objects and Status, 26.

[28] “Relief Society Headquarters,” Woman’s Exponent, January 1910, 45.

[29] Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 176–77.

[30] “Relief Society Headquarters,” Woman’s Exponent, January 1910, 45.

[31] Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 177.

[32] Gates, “Women in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints,” 14.”

[33] Belle S. Spafford, “A Relief Society Building to Be Erected,” Relief Society Magazine, December 1945, 751.

[34] Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 244.

[35] Jennifer Reeder and Kate Holbrook, At the Pulpit, 185 Years of Discovery by Latter-day Saint Women (Salt Lake City: The Church Historian’s Press, 2017), 145–46.

[36] George Albert Smith, “Address,” General Relief Society Conference, October 1945, in Relief Society Magazine, December 1945, 719.

[37] Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 308.

[38] Spafford, “A Relief Society Building to Be Erected,” 751.

[39] Belle S. Spafford, “Plan for Financing a Relief Society Building,” Relief Society Magazine, December 1947, 797.

[40] Spafford, “A Relief Society Building to Be Erected,” 751.

[41] Vesta P. Crawford, “A Journal History of the Relief Society Building,” Vesta P. Crawford Book Drafts, Vault MSS 1282, box 1, folder 1, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[42] Vera Mae Fuller, “The Symbol of a Dream,” Relief Society Magazine, February 1949, 89.

[43] Belle S. Spafford Oral History, interviews by Jill Mulvay Derr, 1975–1976, typescript 108–9, James H. Moyle Oral History Program, Church Archives; as quoted in Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 177.

[44] Marianne C. Sharp, “And What of the Promise?,” Relief Society Magazine, November 1948, 728.

[45] “Relief Society Building News,” Relief Society Magazine, January 1948, 24.

[46] George Albert Smith, “Address to the Members of the Relief Society,” Relief Society Magazine, December 1945, 715–16.

[47] Belle S. Spafford, “Joy in Full Measure,” Relief Society Magazine, November 1948, 725.

[48] Spafford, “Plan for Financing a Relief Society Building,” 798–99.

[49] Vesta P. Crawford, “Financial Plan for the Relief Society Building,” Vesta P. Crawford Book Drafts, mss 1282, box 1, folder 1, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[50] Crawford, “A Journal History of the Relief Society Building.”

[51] “Relief Society Building News,” March 1948, 151.

[52] “Relief Society Building News,” March 1948, 152.

[53] Julie Dockstader Heaps, “Milestone: Relief Society Building a Symbol of Sisterhood,” Deseret News, 25 March 2006.

[54] Crawford, “Journal History of the Relief Society Building.”

[55] Spafford, “Plan for Financing a Relief Society Building,” 798–99.

[56] “Relief Society Building News,” March 1948, 152.

[57] Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 309.

[58] Spafford, “Plan for Financing a Relief Society Building,” 798.

[59] Crawford, “Journal History of the Relief Society Building.”

[60] Crawford, “Journal History of the Relief Society Building.”

[61] Sharp, “And What of the Promise?,” 727.

[62] Spafford, “Joy in Full Measure,” 724.

[63] Heaps, “Relief Society Building a Symbol of Sisterhood.”

[64] Crawford, “Journal History of the Relief Society Building.”

[65] Crawford, “Journal History of the Relief Society Building.”

[66] Spafford, “Relief Society Building to Be Erected,” 752.

[67] First Presidency, “Letter of Permission to Grant Building Site for Relief Society Building, Oct. 3, 1952,” in Crawford, “Journal History of the Relief Society Building.”

[68] Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 308; “George Cannon Young, Architect,” Church History, https://

[69] The design for the building was inspired in part by the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC “George Cannon Young, Architect,” Church History, https://

[70] “Relief Society Building News,” April 1948, 229.

[71] Spafford, “Plan for Financing a Relief Society Building,” 796–97.

[72] Crawford, “Journal History of the Relief Society Building.”

[73] Spafford, “Relief Society Building to Be Erected,” 753.

[74] “Relief Society Building News,” April 1948, 229.

[75] Spafford, “Relief Society Building to Be Erected,” 752.

[76] Crawford, “Journal History of the Relief Society Building.”

[77] Spafford, “Plan for Financing a Relief Society Building,” 799.

[78] “Relief Society Building News,” August 1948, 518.

[79] “Relief Society Building News,” January 1948, 24.

[80] “Relief Society Building News,” April 1948, 229.

[81] Crawford, “Journal History of the Relief Society Building.”

[82] “Relief Society Building News,” February 1948, 83–84.

[83] Heaps, “Relief Society Building a Symbol of Sisterhood.”

[84] “Relief Society Building News,” February 1948, 83–84.

[85] Spafford, “Joy in Full Measure,” 725.

[86] “Relief Society Building News,” July 1948, 441.

[87] “Relief Society Building News,” July 1948, 441–42.

[88] “Relief Society Building News,” February 1948, 83.

[89] Sharp, “And What of the Promise?,” 728.

[90] “Relief Society Building News,” November 1948, 730–31.

[91] “Relief Society Building News,” October 1948, 654–55.

[92] Emma Artimissa Butler, “The Relief Society Building,” FamilySearch Memories; https://

[93] Sharp, “And What of the Promise?,” 728–29.

[94] Sharp, “And What of the Promise?,” 728.

[95] Spafford, “Plan for Financing a Relief Society Building,” 795.

[96] Sharp, “Report of Relief Society Building Activities,” 793.

[97] Tammy Reque, “Inside the Relief Society Building,” Temple Square Blog, https://

[98] Belle S. Spafford, “We Built As One,” Relief Society Magazine, December 1956, 799.

[99] Reque, “Inside the Relief Society Building,” https://

[100] Heaps, “Milestone: Relief Society Building a Symbol of Sisterhood.”

[101] Crawford, “Journal History of the Relief Society Building.”

[102] Different regions of the world that sent gifts for the Relief Society Building included Alaska, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Brazil, Canada, Central America, China, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Egypt, England, Finland, France, Germany, Hawaii, Iran, Italy, Japan, Korea, Libya, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Okinawa, Palestine, Samoa, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, Tahiti, and Tonga.

[103] Heaps, “Milestone: Relief Society Building a Symbol of Sisterhood.”

[104] David O. McKay, “Dedicatory Prayer of the Relief Society Building,” Relief Society Magazine, December 1956, 788.

[105] McKay, “Dedicatory Prayer of the Relief Society Building,” 789.

[106] Spafford, “Joy in Full Measure,” 725.

[107] Reque, “Inside the Relief Society Building,” https://

[108] Joseph Nye, “China’s Soft Power Deficit to Catch Up, Its Politics Must Unleash the Many Talents of Its Civil Society,” Wall Street Journal, 8 May 2012.

[109] Sharp, “Dedicated Home for Relief Society,” 817.