The Book of Moses and Temple Worship

Aaron P. Schade and Matthew L. Bowen, "The Book of Moses and Temple Worship," in The Book of Moses: from the Ancient of Days to the Latter Days (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 381‒412.

Introduction

As we have attempted to show throughout this volume, the Book of Moses influenced the early Church members in many profound ways. This scriptural text and the subsequent revelations given to the Prophet Joseph Smith expanded the Saints’ individual and collective views of heaven and earth, the purposes of their creation, and their place in the cosmos—God’s created order. The process of ongoing revelation from God to Joseph Smith reestablished an important link between heaven and earth that Enoch and his people had enjoyed and that similarly directed the early Church in its pursuit of Zion.

A major element of the pursuit of Zion involved the development of ritual and worship in temples.[1] Almost immediately after the establishment of the restored Church on April 6, 1830, the Prophet Joseph Smith began receiving revelations directing the Saints to “gather” to “the Ohio” and to build a temple. The first mention of this temple in the canonized revelations of the Doctrine and Covenants (36:8) came on December 9, 1830, but there is additional evidence that Joseph was receiving revelation on building a temple even before this.[2]

Concerning a December 1831 revelation, sometimes referred to as the “olive leaf . . . plucked from the Tree of Paradise,” Frederick G. Williams reported that “Bro[ther] Joseph arose and said, to receive revelation and the blessing of heaven it was necessary to have our minds on God and exercise faith and become of one heart and of one mind. Therefore he recommended all present to pray separately and vocally to the Lord for [him] to reveal his will unto us concerning the upbuilding of Zion.”[3] Joseph Smith then received the content of Doctrine and Covenants 88 along with the reiteration of the commandment to build a temple: “Organize yourselves; prepare every needful thing; and establish a house, even a house of prayer, a house of fasting, a house of faith, a house of learning, a house of glory, a house of order, a house of God; that your incomings may be in the name of the Lord; that your outgoings may be in the name of the Lord; that all your salutations may be in the name of the Lord, with uplifted hands unto the Most High” (vv. 119–20).

The development of latter-day temple worship appears to have commenced early in the Restoration and during the Prophet Joseph Smith’s translation of the Bible.[4] Although there are numerous intimations of temple ritual and worship throughout the Book of Mormon (e.g., 2 Nephi 32:4; Alma 12:9–11), it was during the later period of Joseph’s inspired translation of Genesis that God began revealing truths that would lead to the ritual reenactment of biblical narratives in temples as part of covenant-making ceremonies.[5] David Howlett has explained the effect of scripture on temple worship and its development:

No early Latter Day Saint systematized the emerging temple theology practiced in Kirtland. However, as a vernacular theology, their temple cultus can in part be approached as the outworking of an iconic reading of scripture. They read scripture as a living picture that they could recapture again in their lives. Philip Barlow argues that early Latter Day Saints “were actually recapitulating, living through the stories of Israel and early Christianity—reestablishing the covenant, gathering the Lord’s elect, separating Israel from the Gentiles, organizing the Church, preaching the gospel, building up the kingdom, living in sacred space and time. With this in mind, we can understand the Kirtland Temple rituals as performances of biblical stories that would transform the world. In other words, performing the rituals was not about remembering a day of Pentecost. It was about living Pentecost in the latter days. Such a recapitulation would result in millennial redemption, too.”[6]

The various temple ordinances, especially as we recognize them today, did not emerge ex nihilo fully formed, nor did the Lord reveal them in an instant. They came over time, and several developments occurred at important junctures.[7] The Prophet Joseph Smith administered them first to those closest to him, but by the end of the Nauvoo period they had become available to many more members of the Church. In this chapter we discuss this evolution of revealed temple rites and worship and how the Book of Moses came to bear on that process.

It is also important to understand that the temple rituals may not have been written down during Joseph Smith’s lifetime.[8] However, it seems clear from later statements by individuals who participated in temple worship that the rituals reflected the early chapters of the Book of Moses/

In the temple liturgy he completed in Nauvoo, [Joseph] Smith brought to an idiosyncratic fruition his twin projects of metaphysical translation: the transformation of texts and humans. His followers worshiped according to a script that deposited them directly into the scriptural scenes. . . . They found themselves bodily within the Garden of Eden, witnesses to the creation of heaven, earth, and humanity. As they became direct participants in cosmic history, welding their own links to their ancestors the same way scripture did, they were themselves transformed. They became queens and priestesses, kings and priests, and in that royal priesthood they witnessed the full flowering of their genetically divine nature. These Latter-day Saint worshipers simulated Elijah’s and Enoch’s translation into the presence of God, newly able to bear the divine glory. [Joseph] Smith was murdered by a vigilante mob before the physical structure of the Nauvoo temple could be completed, and he never reduced the liturgy to written form. Completing the temple and its endowment was a project for his successors. But he’d still managed to find a way to embody the theologies he had been pondering, testing, and fine-tuning for most of his adult life. . . . It is fitting that his grand project for rereading the Bible would find its way finally into a community in a sacred location on earth that proved to its participants to be a portal into heaven. This was the apogee of scripture and the fruition of a religious career.[10]

The scriptural accounts of creation and the Garden of Eden constituted important pieces of the theological development of temple ritual in the early Church. These accounts furnished the Prophet Joseph Smith with a means of telling modern audiences the story of how God intended to achieve the immortality and eternal life of his children. Moreover, they provided a vehicle for transporting the Saints through a series of Aaronic and Melchizedek Priesthood covenants and ordinances, the latter specifically preparing them to “see the face of God, even the Father, and live” (Doctrine and Covenants 84:22), all while producing the requisite “power of godliness” within individuals (v. 21).[11]

As outlined in the time line below, the early revelations associated with the Book of Moses and its attendant themes included visions of the heavens and the cosmos, the purposes of creation, and explanations of the human capacity—through Christ’s atoning sacrifice—to reach the realms of God and find one’s place among his eternal family, “creating a chain of God’s family who are sealed in heaven to him.”[12] As anticipated in the visions of Enoch, heaven and earth became more closely bound together as resurrected beings such as Moses, Elias, Elijah, John the Baptist, and the ancient apostles Peter, James, and John (all of whom were restoring priesthood keys; see Doctrine and Covenants 13, 27, 110; Joseph Smith—History 1:68–70) visited Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery. In these visitations, both realms experienced an at-one-ment of sorts that anticipated the final deification of the righteousness and ultimately the incorporation of the entire earth into the realm of God’s holiness (see Doctrine and Covenants 88:25–34).[13] For the Prophet Joseph Smith, “the culminating purpose of the Restoration was to provide the priesthood and temple ordinances that would seal men and women into eternal marriages and link them in an eternal, familial chain of belonging.”[14] The Garden of Eden and purposes of creation outlined in scripture provided the theological backdrop for accomplishing these objectives.

The Book of Moses and the concept of returning to Eden by “the way of the tree of life” (Genesis 3:24; Moses 4:31) back into the presence of God as a template of salvation perhaps profoundly influenced the relocation of the early Saints to Missouri, the revealed location of the Garden of Eden.[15] Later on, this template of salvation would also shape the architecture of the temple, which would incorporate a representation of the Garden of Eden as part of a ritual ascent back into the presence of God. The early Saints had already been introduced to a similar concept in 2 Nephi 31–32, in which the ancient prophet Nephi describes the “doctrine of Christ” with its principles and ordinances as “the way” back into God’s presence (see especially 2 Nephi 31:21; 32:1, 5).[16] Sam Brown summarizes how the Garden of Eden as part of the ritual reenactment of the Fall and the return to God’s presence was reflected in the early worship of the Saints and in temple worship as it developed in the restored Church:

In the endowment, worshipers participated in the cosmic order as it stretched through time. [Joseph] Smith had been talking to people about living in Eden since the 1830s. He’d been trying to settle his people in the section of Missouri that he associated geographically with Eden itself. The Saints sang about and worshiped near the great valley (Adam-ondi-Ahman) where they believed Adam had gathered his offspring for a deathbed farewell. Now in the temple rites, believers stepped into a ritual recapitulation of that Eden. They did so as part of their integration into the ancient cosmos. They did so in a way that both effected and affected that cosmic order. The order stood over them, but they also helped shape it.[17]

The temple would become the mechanism that linked and bonded the heavens where God dwells and the temporal earth together in purpose. The temple functioned as “the gate of heaven” (Genesis 28:17; Helaman 3:28), providing “a master plan that plots cosmic time and heavenly space and offers a means of traversing the chasm that impedes human union with the divine.”[18] The objective of seeking that which is eternal came to fruition through temple experiences in which heavenly beings, revelations, and rituals taught people “the words of eternal life” (Moses 6:59), including names and key words (see Doctrine and Covenants 130:11) that would enable entrance into God’s presence. These temple experiences would enable worshipers and covenant makers to see the face of God and live (see 84:19–22), just as Adam and Eve had seen God’s “face” in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3:8; Moses 4:14) and as Moses had seen him “face to face” as recounted in the revelations of the New Translation of the Bible (Moses 1:2, 31; 7:4).

Sequence of Events

The time line below outlines the development of temple worship, themes, and covenants:

Time Line[19]

21 September 1823: Joseph Smith—History 1:26, 40—first reference to priesthood and references to work to be done in future temples; Moroni quotes Malachi 3 and revealed it was about to be fulfilled

April–May 1829: Doctrine and Covenants 10, 11—Joseph Smith begins receiving revelations on Light of Christ and the creative process

April 1829: Doctrine and Covenants 6—revelation on establishing Zion and receiving mysteries

May 15, 1829: Doctrine and Covenants 13—Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery receive the Aaronic Priesthood under the hand of John the Baptist, a resurrected being

Late May/

6 April 1830: Doctrine and Covenants 20:1—restoration of the Church in the last dispensation

30 December 1830: Doctrine and Covenants 37:3; 38:31–32—Saints are to leave New York and gather to Ohio, where they “shall be endowed with power from on high”

1830–1831: Revelations including Doctrine and Covenants 36:8 (9 December 1830), 42:36 (9 February 1831), and 133:2 (3 November 1831) indicate that Jesus Christ will appear in the temple as part of the ushering in of his second coming

June 1830–31: Joseph Smith translates the Book of Moses/

1831–32: Joseph Smith translates the New Testament. In translating John 1, he learns more about the Creation

2 January 1831: Doctrine and Covenants 38:32—Saints will be endowed from on high

9 February 1831: Doctrine and Covenants 42:36—revelation to build the modern city of Zion; ancient temple prophecy of the Lord coming to his temple

February 1831: Doctrine and Covenants 43—Saints are counseled how not to be deceived; they will be endowed with power and knowledge of mysteries

2 July 1831: Doctrine and Covenants 57:1–3—revelation that “a spot for the temple is lying westward”

3 August 1831: Joseph Smith lays the cornerstone for a temple in Independence and the site is dedicated[21]

25–26 October 1831: Power to seal to eternal life is discussed[22]

5 November 1831: Doctrine and Covenants 68:2, 12—revelation on power to seal in heaven and on earth; precursors for the endowment ceremony eventually performed in the Kirtland Temple

15 November 1831: Elders seal individuals/

16 February 1832: Doctrine and Covenants 76—vision of the three kingdoms of glory

27–28 December 1832: Doctrine and Covenants 88—requirements to enter kingdoms, emphasis on light; the endowment is expanded and direction is given to establish a house of God (in Kirtland) and a School of the Prophets to receive instruction; new ordinance to be introduced: washing of feet

1833: Temple ordinances are revealed as “restorations of ancient ordinances of salvation”; Joseph Smith “[begins] to introduce these innovations piecemeal as, according to his own explanation, he slowly [comes] to understand them”[23]

23 January 1833: Joseph washes feet of members of School of the Prophets in Newel K. Whitney’s general store (see John 13)[24]

23 January 1833: Initial meeting of School of the Prophets begins (second precursor to the Kirtland endowment), includes washing of feet; Zebedee Coltrin records members seeing Father and Son

23 July 1833: Cornerstones of the Kirtland Temple are laid after the order of the holy priesthood[25]

September 1833: Elders continue to seal people to eternal life (not as a ceremony but as group pronouncements)

March 1834: Discussion of becoming “kings and priests unto God”[26]

1835 Summer–Fall: Abraham papyri acquired and Joseph begins their translation; information about creation, Garden of Eden, and increase in temple activity and ritual in Kirtland

1835–1836: Hebrew grammar classes begin; Joseph Smith translates Abraham 3 about stages of existence

1 October 1835: Joseph Smith, W. W. Phelps, and Oliver Cowdery work on the Egyptian alphabet and additionally the “system of astronomy [is] unfolded” to them; further information on temple worship[27]

November 1835: Abraham translation; development of endowment

21 January 1836: The first washings and anointing are given to the elders of the Church (First Presidency); accounts of visions during the anointing ceremony[28]

21 January 1836: Doctrine and Covenants 137:7–9—vision of the celestial kingdom, in which the doctrine of salvation for the dead is revealed; Joseph Smith sees his deceased brother Alvin

6 February 1836: Several anointings are performed; the anointed “receive the seal all of their blessings” and see visions[29]

21 January–February 1836: The endowment ceremony goes beyond the 1833 washing of feet, anointing with oil, and washing “sealed” with an anointing

27 March 1836: Doctrine and Covenants 109—dedication of the Kirtland Temple, becoming the Church’s first completed temple; accounts of outpourings of the Spirit, speaking in tongues, visions, and visitations (endowment of power) inspire the hymn “The Spirit of God”

3 April 1836: Doctrine and Covenants 110—sealing keys for temple ordinances are restored to Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery through Moses, Elias, and Elijah

December 1837: Ordinances (endowments of power) are continued in Kirtland until the Saints’ departure

26 April 1838: Doctrine and Covenants 11—temple to be built at Far West, Missouri

4 July 1838: Temple cornerstones in Far West are dedicated[30]

4 July 1838: Fourth temple site selected and cornerstones laid at Adam-ondi-Ahman[31]

27 June 1839: Joseph Smith explains the meaning of making one’s calling and election sure in a sermon in Nauvoo (based on 2 Peter 1:10–11 and tied to John 14:26 and the Second Comforter)[32]

15 August 1840: Joseph Smith teaches the doctrine of baptism for the dead[33]

August 1840: Announcement to build the Nauvoo Temple[34]

19 January 1841: Doctrine and Covenants 124:37—revelation and instructions for the Nauvoo Temple; baptism for the dead and washings and anointing must be performed in the house of the Lord in his name; hints at a greater endowment: “this understanding was reinforced by the physical layout of the temple wherein ordinances would be revealed in stages[;] the first begins an expansion of the earlier rituals of Kirtland”[35]

6 April 1841: Cornerstone ceremony for the Nauvoo Temple[36]

November 1841: The first baptisms for the dead in a modern temple are performed in a temporary dedicated font in the basement of the Nauvoo Temple[37]

19 February 1842: Wilford Woodruff mentions in his journal that “the Lord is Blessing Joseph with Power to reveal the mysteries of the kingdom of God [perhaps with specific reference to temple ordinances]; to translate through the urim & Thummim Ancient records & Hyeroglyphics as old as Abraham or Adam [perhaps suggesting Woodruff’s understanding of the relationship between Adam, Abraham, priesthood, and temple ordinances].”

Spring 1842: Joseph Smith translates the writings of Abraham (specifically Facsimile 2 about temple ritual); temple ritual expands

March–May 1842: All five chapters of the Book of Abraham, including the facsimiles, are published in Times and Seasons[38]

1 March 1842: The Times and Seasons prints Facsimile 1 and Abraham 1:1–2:18

15 March 1842: The Times and Seasons prints Facsimile 2 and more from the Book of Abraham; explanations of things to be understood in the temple

28 April 1842: The Relief Society is about to receive temple ordinances and receive “keys”[39] (compare the language in Facsimile 2 in the Book of Abraham)

1 May 1842: A revelation reveals that the “devil knows many signs,” but not the sign of the Son of Man, which can be known only in the “holiest of Holies”; keys to detect the devil (according to Wilford Woodruff, Joseph taught the key to detecting the devil previously on June 27, 1839)[40]

3 May 1842: Joseph Smith’s Red Brick Store is fitted and prepared to present the endowment ceremony; potted plants are brought in to represent the Garden of Eden

3 May 1842: Joseph Smith enlists a few men to prepare the space in his Red Brick Store where the Nauvoo Masons met, preparatory to endowing a few elders

4–5 May 1842: Joseph Smith reveals to a small company the specific temple-related ordinance called the endowment, which bestows the knowledge necessary for recipients to enter into God’s presence[41]

1843: Joseph Smith administers the endowment to other Church members and leaders[42]

17 May 1843: Doctrine and Covenants 131—“the more sure word of prophecy means a man’s knowing that he is sealed up unto eternal life, by revelation and the spirit of prophecy, through the power of the Holy Priesthood”

11 June 1843: Joseph teaches that God has always gathered people through temples “in any age”[43]

27 August 1843: More knowledge is revealed concerning patriarchal priesthood[44]

27 June 1844: Joseph Smith dies a martyr in Carthage Jail

December 1845: First descriptions of performing endowments in the Nauvoo Temple appear[45]

30 April and 1 May 1846: The Nauvoo Temple is dedicated[46]

Moses

The King James translation of Genesis, the revealed text of what would become the Book of Moses, and the revelations to the Prophet Joseph Smith that accompanied the reception of this material profoundly affected the development of temple worship in the early Restoration. The theophanic experiences of Moses—which took him from Egypt to Midian and his father-in-law Jethro, from whom Moses received the priesthood, and thence to Mount Sinai, where he received the pattern for the tabernacle—were means by which the Lord intended to prepare all his ancient people to return to his presence.

The Prophet Joseph Smith walked a similar path. Ancient scripture and modern revelation taught him about God’s purposes, including the necessity of the covenant and the temple. Like Moses, Joseph Smith received revelations, laws, priesthood, covenants, and the pattern for temple worship—all for the express purpose of bringing God’s children back into his presence. Those revelations associated with enacting covenantal ritual formulated from the Book of Moses, Genesis, and Abraham flesh out those details of the purposes of creation.

And yet, for the Prophet Joseph Smith even temple worship was just the beginning, for he learned remarkable truths about the divine nature, capacity, and destiny of the human family. As Sam Brown has noted: “Instead of being a process that wraps up before the creation of humanity, as was typical for theogonies, [Joseph] Smith’s divine anthropology had never started and would never end. It was always in process—tethered, through translations both textual and human, to the time before time when God organized the world. The ongoing birth of the gods recurs perpetually within the temple endowment.”[47] This concept had been everything the Saints had been striving toward as they pursued the Lord’s promises to endow them with blessings from on high. With all the spiritual blessings that accompanied them along their difficult path of discipleship, it was in the temple in the Nauvoo period where the people most poignantly came to know God and his purposes, a knowledge that would take them back to creation and the Garden of Eden. Brown further observes:

In a sermon in the summer of 1839, [Joseph] Smith made the association explicit. There he taught that the familial priesthood was the order established by Adam in the aftermath of the Fall. . . . “The Priesthood was. first given To Adam: he obtained the first Presidency & held the Keys of it, from gen[e]ration to Generation; he obtained it in the creation before the world was formed as in Gen. I, 26:28—he had dominion given him over every living Creature. He is Michael, the Archangel.” . . . In the time before mortal life Adam . . . obtained the priesthood that would transfer from generation to generation. That priesthood organized the Chain of Belonging on earth. Smith continued, “The Priesthood is an everlasting principle & Existed with God from Eternity & will to Eternity, without beginning of days or end of years.”[48]

We now turn to how Moses and his writings fit into the broader picture of temple worship, theophanies, and communing with God.

Moses and the Sinai Experience

Moses spent many years among the Midianites, during which time he received the priesthood and instruction from his father-in-law, Jethro (see discussion in chapter 6). During this tutoring period, the Lord prepared Moses to do on Mount Sinai what the ordinances of the Melchizedek Priesthood were designed to prepare a person to do: “see the face of God . . . and live” (Doctrine and Covenants 84:22; see Moses 1:4–5, 31; Exodus 2–3; JST Exodus 34:1–2). In this way Moses came to know the nature of God and his holiness. Moses’s ascending the mountain of God and speaking with him face-to-face became the template for the temple experience, for what temple teachings convey about obtaining heaven, and for what God desired the Israelites to experience upon their exodus from Egypt: his immediate presence.[49] The revelation found in Doctrine and Covenants 84:23–26 explains this concept:

Now this Moses plainly taught to the children of Israel in the wilderness, and sought diligently to sanctify his people that they might behold the face of God; but they hardened their hearts and could not endure his presence; therefore, the Lord in his wrath, for his anger was kindled against them, swore that they should not enter into his rest while in the wilderness, which rest is the fulness of his glory. Therefore, he took Moses out of their midst, and the Holy Priesthood also; and the lesser priesthood continued, which priesthood holdeth the key of the ministering of angels and the preparatory gospel.[50]

Exodus 24:9–10 informs us that seventy elders did behold God on the mountain, but the general withdrawal of the people demonstrated their need for more preparation (see 20:18–19). The Prophet Joseph Smith stated that “Moses sought to bring the children of Israel into the presence of God. through the power of the Priesthood but he could not.”[51] In the Joseph Smith Translation of Exodus 34:1–2, the Lord mentioned the higher priesthood and its ordinances associated with temple duties and worship in connection with Moses’s attempt to prepare Israel to commune with God:

And the Lord said unto Moses, Hew thee two other tables of stone, like unto the first, and I will write upon them also, the words of the law, according as they were written at the first on the tables which thou brakest; but it shall not be according to the first, for I will take away the priesthood out of their midst; therefore my holy order, and the ordinances thereof, shall not go before them; for my presence shall not go up in their midst, lest I destroy them. But I will give unto them the law as at the first, but it shall be after the law of a carnal commandment; for I have sworn in my wrath, that they shall not enter into my presence, into my rest, in the days of their pilgrimage. Therefore do as I have commanded thee, and be ready in the morning, and come up in the morning unto mount Sinai, and present thyself there to me, in the top of the mount.

These events precipitated the divine withdrawal of the higher ordinances that God had intended for ancient Israel. Brigham Young explained, “If they had been sanctified and holy, the Children of Israel would not have traveled one year with Moses before they would have received their endowments and the Melchizedek Priesthood [see Doctrine and Covenants 84:23].”[52] As a result of Israel’s withdrawal from God’s presence, God instituted the Levitical Priesthood with holiness codes to prepare the priests and the people to commune with God. The Lord instructed Moses to erect the tabernacle for the establishment and maintenance of covenants with God and to prepare individuals, and Israel as a whole, to become “holy” as God is “holy” (Leviticus 11:44–45). The tabernacle re-created an environment in the pattern of “Eden the garden of God” on “the holy mountain of God” (Ezekiel 28:13–14) and held forth the possibility that Israel could eventually, through Christ’s atonement, regain God’s presence and commune with God—a possibility reflected in its architectural and ritual design. Just as Moses’s experience with revelation and tabernacle/

Mount Sinai and the Tabernacle

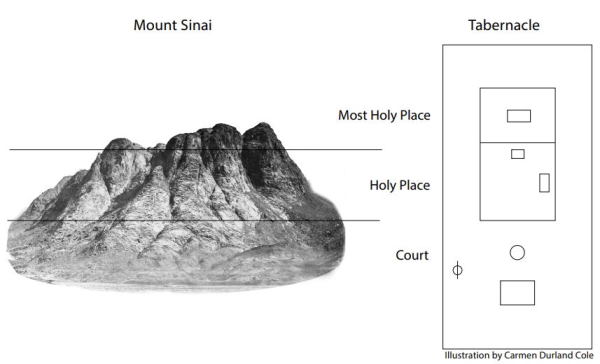

The experience and theophany of Moses on Mount Sinai appears to constitute a template of the temple and its representation of communion with God.[53] John Lundquist observed that “the temple of Solomon would seem ultimately to be little more than the architectural realization and the ritual enlargement of the Sinai experience.”[54] The wilderness tabernacle in a very real sense ritualized what Moses and Israel had experienced at Mount Sinai. Michael Morales has summarized the ritual aspect of Moses’s own experience on the mountain as follows:

The similarity of arrangement here [Sinai] with that of the subsequent tabernacle is striking. The fence around the mountain, with an altar at the foot of the mountain, would correspond to the court of the sanctuary with its altar of burnt offering; the limited group of people who could go up to a certain point on the mountain would correspond to the priests of the sanctuary, who could enter into the first apartment or “holy place”; and the fact that only Moses could go up to the very presence of Yahweh would correspond to the activity of the high priest, who alone could enter into the presence of Yahweh in the inner apartment of the sanctuary, or “most holy place.”[55]

Figure 3: Mount Sinai and the Tabernacle. The architecture of the wilderness tabernacle enacts ritual progression paralleling the journey into God's presence as Moses experienced it on Sinai. Both the mountain and the tabernacle experiences entailed entrance into the presence of God, with the tabernacle and its priestly ordinances ritually enabling that process for ancient Israel.

Figure 3: Mount Sinai and the Tabernacle. The architecture of the wilderness tabernacle enacts ritual progression paralleling the journey into God's presence as Moses experienced it on Sinai. Both the mountain and the tabernacle experiences entailed entrance into the presence of God, with the tabernacle and its priestly ordinances ritually enabling that process for ancient Israel.

Moses received the pattern of the tabernacle through revelation (see Exodus 25:9, 40; 26:30; 37:8), and God revealed to him the pattern of creation and the Garden of Eden, with its attendant ordinances and rituals as a way to be sanctified and commune with God.

From Joseph Smith’s journal, in the entry for Sunday, May 1, 1842, we learn that elements of developing modern temple worship (e.g., sacred keys, signs, and words along with references to the “holiest of Holies” and being “endued with power”) were on his mind during his translation of the Book of Abraham and that he had been receiving ongoing revelation concerning these concepts:

preached in the grove on the keys of the kingdom. . . . The keys are certain signs & words by which false spirits & personages may be detected from true.— which cannot be revealed to the Elders till the Temple is completed.— The rich can only get them in the Temple. The poor may get them on the Mountain top as did moses. The rich cannot be saved without cha[r]ity. giving to feed the poor. when & how God requires as well as building. There are signs in heaven earth & hell. the elders must know them all to be endued with power. to finish their work & prevent imposition. The devil knows many signs. but does not know the sign of the son of man. or Jesus. No one can truly say he knows God until he has handled something. &

thesethis can only be in the holiest of Holies.[56]

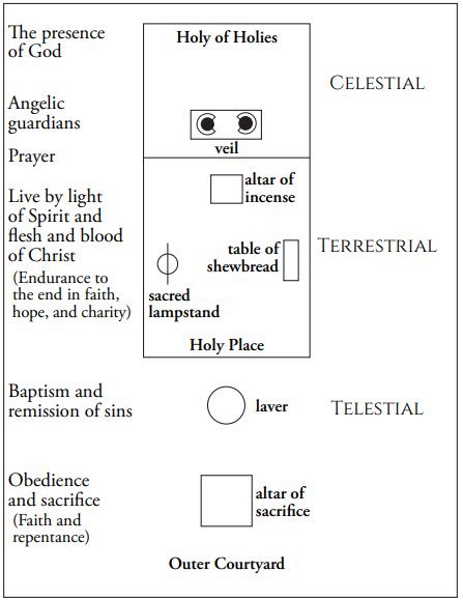

Figure 4: Tabernacle Interior.

Figure 4: Tabernacle Interior.

Among other important details revealed in this journal entry is that the Prophet Joseph Smith also learned through revelation that Moses’s mountaintop theophany was equivalent to a temple experience and its representation of theophany (i.e., it may imply that Moses obtained “certain signs & words” on “the Mountain top”). Joseph’s assertion that “the rich cannot be saved without cha[r]ity, giving to the poor” takes us right back to Moses 7 and Enoch’s society and helps us see the relationship between the temple and Zion. Such explanations provide us insights into the development of latter-day rituals and covenants and their connection to the Old Testament world, including ancient temples. The canonized revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants also inform us as to how the experience of Moses influenced the way Joseph viewed God’s developing temple theology and how he understood modern participation in temples and ordinances as reflections from the past.

The revelations of Doctrine and Covenants 84, received in September 1832, informed the Prophet Joseph Smith that through the power of the Melchizedek Priesthood and through the ordinances therein, “the power of godliness [was] manifest” and people could be prepared to “see the face of God” (vv. 20, 22).[57] Joseph also learned that this was what God was trying to accomplish for Moses and his people. The phrase “to see the face of God” specifically recalls Moses 1:2, 31, where Moses “saw God face to face, and he talked with him,” and later, after his confrontation with Satan and the latter’s expulsion, “Moses stood in the presence of God, and talked with him face to face.” It also recalls later instances in which Moses saw God’s face and lived (see Exodus 33:11; compare Exodus 24:9–11).

Moses and the Tabernacle

Joseph Smith and other early Saints found important antecedents for the Church’s temple architecture and developing ritual in biblical antiquity. With respect to these developments, Moses again (through his writings, revelations, and tabernacle construction projects) became a reference point. In 1841, following the loss of the Kirtland Temple, the Lord reiterated his will that the Saints build a temple for the specific purpose of carrying out ordinance work, including proxy rituals for the dead:

And, again, verily I say unto you, how shall your washings be acceptable unto me, except, ye perform them in a house which you have built to my name? for, for this cause I commanded Moses, that he should build a tabernacle, that they should bear it with them in the wilderness, and to build a house in the land of promise, that those ordinances might be revealed, which had been hid from before the world was; therefore, verily I say unto you, that your anointings and your washings, and your babtisms for the dead, and your solemn assemblys, and your memorials for your sacrifices, by the sons of Levi, and for your oracles in your most holy places, wherein you receive conversations, and your statutes, and judgements, for the beginning of the revelations and foundation of Zion, and for the glory and honor and endowment of all her municiples, are ordained by the ordinance of my holy house, which my people are allways Commanded to build unto my holy name.[58]

Some may question Moses’s historicity and whether ancient Mosaic ritual could have ever looked anything like what Joseph describes in the Restoration. We note, however, that the Lord speaks in the first person in this revelation. His words seem to establish the genetic relationship between the rituals and practices of ancient Israel and its temple and those of the restored gospel. The ordinances associated with Moses’s tabernacle were rooted in his own mountaintop theophanic experiences and, as the Book of Moses further makes clear, divine revelations dating back to the earliest of times (Adam and Eve, Enoch, and Noah). Just as these revealed rituals and ordinances from earliest antiquity linked Moses and his community with the remote past and prepared the people to commune with God themselves, they held (and hold) the capacity to link people today back to Moses, Abraham, and ultimately Adam and Eve. Indeed, the Book of Moses traces the experience of theophany, the performance of religious ritual, and the process of redemptive sanctification all the way back to Adam and Eve (see Moses 5; 6:48–68). Ancient texts and ages of experience converged to create a single continuum of rites and worship, with Joseph and the early Church standing at the summit. Michael Morales has described the interrelationship of the biblical text (especially the five book of Moses, or Pentateuch) with the experience of Moses, the tabernacle, and the community of Israel as follows:

That there appears to be deliberate narrative intention to demonstrate continuity between the cosmic mountain religion of the forefathers and the tabernacle/

temple cultus of the original audience seems beyond question—and our suggestion, that the creation, deluge, and exodus narratives “pre-figure” the tabernacle cultus, thereby follows as well. Moses’ “mountain experience” in Exodus 24 will thus become the community’s via the tabernacle: At first, the encounter is reserved for Moses. But the central significance of the Sinai narrative is to demonstrate how this encounter is made transferable, so that it can happen for the whole congregation. Therefore Moses, within the fire, receives the model for the sanctuary, which undoubtedly is heaven itself, the place where God’s own glory shines forth. Therefore the tent of meeting is built, and the cloud of God’s presence moves from Sinai, the world mountain, into the sanctuary, where it is possible for all to encounter God in cultic praise.[59]

Moses and Aaron established the Aaronic and Levitical priesthoods by conferring a limited priesthood upon the sons of Aaron and the tribe of Levi. The sons of Aaron were prepared to officiate in the temple cultus through ordinances of washing, anointing, and clothing (see Exodus 28; 40)—ordinances consonant with Adam and Eve’s baptism, reception of the Holy Ghost, and clothing in sacred protective tunics of animal skins that prefigured the protection of Christ’s atoning sacrifice and Adam’s priestly ordination. God revealed to Moses the pattern of the tabernacle—a pattern that centered on creation and the Garden of Eden and linking the community back to those earliest sacred events. Morales further describes the place that the tabernacle and its construction hold in relation to the creation accounts:

More narrowly, chapters 19–40 of Exodus may be considered, formally, a meticulously composed, coherent story that culminates with the glory cloud’s descent upon the completed tabernacle. Justifiably, then, Davies believes “worship” has a strong claim to be the central theological theme of Exodus, linking together salvation, covenant, and law—a theology, what’s more, going back as far as can be discerned in the history of the tradition. Now beyond all else to which the tabernacle/המשׁכן cultus and its rituals pertain, one must keep in view the fundamental understanding of it as the dwelling/שׁכן of God (cf. Exodus 25.8–9; 29.45–46), so that “worship” may be defined broadly as “dwelling in the divine Presence.” Already, then, the bookends of the Genesis-through-Exodus narrative begin to emerge: the seventh day/

garden of Eden (Genesis 1–3) and the tabernacle Presence of God among his cultic community (Exodus 40).[60]

Temple architecture and its ordinances symbolized and pointed to what ancient Israel could attain to through the priesthood (and what the Israelites were restricted from).[61] The sanctuary and the sacrificial rites were established to support God’s purposes. The washed, clothed, and anointed priests received sacred charges in priestly holiness codes that enabled them to worthily officiate and minister in the tabernacle. The people also received commandments for obtaining and maintaining their ethical and ritual purity and their holiness. The temple represented—and helped them visualize—their journey back to God. Sacrifices, ordinances, and the principles of divine holiness pointing to Jesus Christ provided the “way” (compare Nephi’s “doctrine of Christ,” in 2 Nephi 31).

We further note that the Book of Moses account of Enoch also furnished a precedent for the Mosaic tabernacle as the place of the Lord’s “dwelling” (Hebrew šākan). Moses 7:16 uses imagery that foreshadowed the tabernacle in reporting that “the Lord came and dwelt with his people, and they dwelt in righteousness.” In a corresponding image from the same pericope, the Lord foretold that latter-day Zion would be characterized by his presence, “for there shall be my tabernacle [compare Hebrew miškān], and it shall be called Zion, a New Jerusalem” (Moses 7:62). The tabernacle thus constituted a symbol linking Enoch’s Zion, Israel in the wilderness, and the restored Church as latter-day Zion/

Tabernacle Architecture

The architecture and sacred objects within the tabernacle re-created the Garden of Eden (the holy place), with the ultimate representation of God’s immediate presence depicted in the holy of holies. The mercy seat (Hebrew kappōret) represented the divine throne, or the place where the Lord was thought to sit or stand. The architecture and veils (particularly vibrant in Solomon’s temple) depicted cherubim guarding and mediating access to the dwelling place of God, intimated in the Genesis and Book of Moses presentations of the Garden of Eden as constituting the first temple.[62] Ancient Near Eastern temple architecture and iconography often involved garden scenes and trees of life.[63] The ritual texts affiliated with temple ritual, in all their varieties, were also commonly associated with rivers and gardens such as those encountered in the scriptural accounts of the Garden of Eden.[64] An example of this was the creation and animation of idols discussed in chapter 10. Ancient Near Eastern temple texts and iconography reflect a variety of patterns and architecture throughout the Bronze Age. The temple pattern described in Exodus in relation to the tabernacle, and later in the construction of Solomon’s temple in 1 Kings 5–8, became standard throughout the Iron Age in Syria-Palestine.[65] This included a tripartite construction consisting of an outer courtyard, an inner sanctuary, and a third component often described as the holy place, where a standing stone or objects representing the presence of the deity were situated. Ancient tripartite temple architecture corresponds to similar zones in latter-day temple architecture and to what Joseph Smith described as “the three principal rounds of Jacob’s Ladder, the Telestial, the Terrestrial and the Celestial glories or Kingdoms, where Paul saw and heard things which were not lawful for him to utter [see 2 Corinthians 12:2].”[66]

Ancient Near Eastern inscriptional material often used language that expressed the idea of “causing the god to dwell” in the holiest place (from the root yšb, “sit, remain, dwell”).[67] In the Old Testament tabernacle/

The design of the tabernacle (particularly pronounced in Solomon’s temple) consisted of floral objects and depictions, including the menorah, which functioned as a stylized tree of life, evoking images of creation and the events of the Garden of Eden.[69] Synthesizing the work of several scholars, Morales[70] notes the following:

The tabernacle, then, “is a microcosm of creation, the world order as God intended it writ small in Israel.”[71] The parallels thus established, when Yhwh fills the tabernacle, this is “a sign that the new ‘creation’ has been achieved.”[72] Interestingly, the sixth century Egyptian Christian Cosmas, in his book Christian Topography, posited that the creation account of Genesis 1 was Moses’ description of the תבנית shown him atop Sinai, and that “the tabernacle prepared by Moses in the wilderness . . . was a type and copy of the whole world”:

“Then when he [Moses] had come down from the Mountain he was ordered by God to make the tabernacle, which was a representation of what he had seen on the Mountain, namely, an impress of the world. . . . Since therefore it had been shown him how God made the heaven and the earth, and how on the second day he made the firmament in the middle between them, and thus made the one place into two places, so Moses, in like manner, in accordance with the pattern which he had seen, made the tabernacle and placed the veil in the middle and by this division made the one tabernacle into two, the inner and the outer.”[73]

For both Moses and the ancient Israelites, as well as Joseph Smith and the early Church, temples and sacred space were developed to evoke creation and garden scenes depicted in the recorded scriptural texts.

Texts and Rituals

Genesis as an ancient temple text?

While the architecture of the tabernacle and the subsequent Solomonic temple clearly reflect Edenic scenes and a covenantal journey back to the presence of God, conclusive evidence tying the early chapters of Genesis to actual temple texts that were ritually performed in the ancient tabernacle/

Going even further with temple ritual, some see the priestly enactment of the Day of Atonement described in Leviticus 16 as being connected with the creation and garden accounts of Genesis 1–3.[77] In fact, Morales addresses this intriguing possibility as follows:

We have seen how the cosmic mountain, as expressed through historical mounts in the narrative of the Pentateuch, gave way to the tabernacle cultus informed by it: the כבוד [kābôd] (divine presence) moved from Sinai to the tabernacle, the three part structure of the tabernacle corresponding to the three parts of the mountain with the Holy of Holies representing the clouded summit. As the peaks of Sinai and the Ararat mount had echoed Eden in their respective narratives, so the Holy of Holies corresponds to Eden and the blessing of the divine Presence, and the high priest portrays Adam (/

Noah/ Moses). Thus the narrative arc from Genesis 1–3 to Exodus 40 may be traced as the expulsion from the divine Presence to the gained re-entry into the divine Presence via the tabernacle cultus, from the profound descent of Adam to the dramatic “ascent” of the high priest into the Holy of Holies, particularly on the Day of Atonement.[78]

Thus, although it is unclear whether forms of Genesis 1–3 ever served as performance texts in the tabernacle/

The focus of Israel’s cultic calendar was upon entering the Holy of Holies, after elaborate preparations (Leviticus 16.2–17), one day out of the year, the Day of Atonement, a privilege granted the high priest alone—his “most critical role.” Indeed, this annual ritual of penetrating into the divine Presence may be considered the archetypal priestly act, whereupon Adam-like he fulfills the cosmogonic pattern: Once a year on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, Adam’s eastward expulsion from the Garden is reversed when the high priest travels west past the consuming fire of the sacrifice and the purifying water of the laver, through the veil woven with images of cherubim. Thus, he returns to the original point of creation, where he pours out the atoning blood of the sacrifice, reestablishing the covenant relationship with God.[80]

The priestly activity depicted in the Old Testament regularly reflected in ritual the Primeval History of the Creation and the Garden of Eden.[81] That the Aaronic/

Therefore all things had under the authority of the Priesthood at any former period shall be had again, bringing to pass the restoration spoken of by the mouth of all the Holy Prophets; then shall the Sons of Levi offer an acceptable sacrifice to the Lord. . . .

. . . These Sacrifices as well as every ordinance belonging to the Priesthood will, when the Temple of the Lord shall be built and the Sons of Levi be purified, be fully restored and attended to in all their powers, ramifications and blessings; this ever did and will exist when the powers of the Melchisedec Priesthood are sufficiently manifest. else how can the restitution of all things spoken of by all the Holy Prophets be brought to pass?[83]

Although we do not know all the details as to how and when Joseph Smith began to comprehend all these revelations affecting the development of the temple, a statement by David Calabro may offer a helpful summation (although, again, we do not claim that Genesis/

To what extent was Joseph Smith aware of the connections with ancient ritual in the texts he revealed? It is evident that, by the Nauvoo period at the latest, Joseph Smith did understand the Genesis account that had been revealed to him as a ritual text relating to the ancient temple. The Prophet’s sermons during this period, along with the ordinances and architecture of the Nauvoo Temple which he orchestrated, suggest as much.[84]

Calabro further notes[85] that Jeffrey Bradshaw has accumulated evidence[86] suggesting that Joseph Smith’s comprehension of the significance of the temple and its rituals goes back to his early revelatory experiences.[87]

The influence of Moses and Mosaic writings on the early Church, along with the construction of the ancient tabernacle and modern temples finds expression in a poem composed by Eliza R. Snow in the summer of 1841, entitled “The Temple of God.” In this poem, as Matthew McBride notes, “she captured the kinship the Saints felt with the children of Israel who built the tabernacle of Moses and the sense they had of fulfilling biblical prophecy by building the temple”:

Then, to whom shall Jehovah his purpose declare?

And by whom shall the people be taught to prepare

For the coming of Jesus—a “temple” to build,

That the ancient predictions may all be fulfil’d?

When a Moses of old, was appointed to rear

A place, where the glory of God should appear;

He receiv’d from the hand of the high King of Kings,

A true model a pattern of heavenly things. [. . .]

“Build a house to my name,” the Eternal has said

To a people by truth’s holy principles led:

“Build a house to my name, where my saints may be blest;

Where my glory and pow’r shall in majesty rest.”[88]

In coming to understand and appreciate Moses and the revelations of the Lord to him, early Latter-day Saints began to understand and appreciate the eternal nature of the gospel they were embracing and how the temple fit into that gospel.

Anointing

In connection with Moses and ancient Aaronic priests, Joseph Smith introduced the ordinances of washing and anointing patterned after the ancient order of priestly service.[89] In Old Testament times, temple ritual anointing was a hallmark of Aaronic Priesthood service. Early Church leaders such as Wilford Woodruff understood and viewed participating in ritual anointings as a reflection of priests performing their duties in the ancient tabernacle in the days of Moses.[90] The anointings involved the use of “holy anointing oil” as described in the book of Exodus, and beginning in January of 1836, anointings were performed “in recapitulation of an Old Testament priestly rite.”[91] Sam Brown further notes how “Oliver Cowdery claimed the elders were being ‘annointed with the same kind of oil and in the man[ner] that were Moses and Aaron.’ Following the pattern of Aaron, they would ‘be hallowed’ by the anointings they received.”[92] Moses later appeared as a resurrected being at the Kirtland Temple to restore priesthood keys to gather Israel (see Doctrine and Covenants 110:11), and the ordinances performed in this period reflected a significant reliance on the priestly experience of Moses. The hymn “The Spirit of God” captured the essence of anointing’s significance during the Kirtland Temple period:

The Spirit of God like a fire is burning

The latter day glory begins to come forth

The visions and blessings of old are returning

And angels are coming to visit the earth

We’ll sing and we’ll shout with the armies of heaven,

Hosanna, hosanna, to God and the Lamb!

Let glory to them, in the highest be given!

Henceforth and forever, Amen and amen.

We call in our solemn assemblies, in spirit,

To Spread forth the kingdom of heaven abroad,

That we through our faith may begin to inherit

The visions, and blessings, and glories of God

We’ll wash, and be wash’d and with oil be anointed

withal not omitting the washing of feet

For he that receiveth his penny appointed

Must surely be clean at the harvest of wheat.[93]

Despite the glorious outpouring of spiritual blessings that accompanied the observance of these washings and anointings, this was just the beginning of the temple ordinances the Lord intended to reveal. Brown writes: “On January 28, [1836] when church leaders assembled to ‘seal the blessings which had been promised to them by the holy anoint[ing],’ Sylvester Smith (1806–1880) ‘saw a piller of fire rest down & abide upon the heads of the quorem.’ Despite repeated outpourings of Pentecostal power, though, [Joseph] Smith continued to insist that more was yet to come.”[94]

The Book of Moses as the basis of an ancient temple experience reenacted in a modern setting

The Book of Moses constitutes an important part of the foundation on which much of the revealed temple ritual and worship has been built.[95] The ritual re-experiencing of creation, the Garden of Eden, and the story of Adam and Eve became a significant part of the ancient Israelite experience restored through Joseph Smith.[96] Adam and Eve’s story became every person’s story within a latter-day covenantal context. Anderson and Bergera cite Glen M. Leonard thus:

According to LDS historian Glen M. Leonard, the men’s washings and anointings were “followed by instructions and covenants setting forth a pattern or figurative model for life. The teachings began with a recital of the creation of the earth and its preparation to host life. The story carried the familiar ring of the Genesis account, echoed as well in Joseph Smith’s revealed book of Moses and book of Abraham. The disobedience and expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden set the stage for an explanation of Christ’s atonement for that original transgression and for the sins of the entire human family. Also included was a recital of mankind’s tendency to stray from the truth through apostasy and the need for apostolic authority to administer authoritative ordinances and teach true gospel principles. Participants were reminded that in addition to the Savior’s redemptive gift they must be obedient to God’s commandments to obtain a celestial glory. Within the context of these gospel instructions, the initiates made covenants of personal virtue and benevolence and of commitment to the church. They agreed to devote their talents and means to spread the gospel, to strengthen the church, and to prepare the earth for the return of Jesus Christ.”[97]

The scriptural texts clearly affected the development of temple worship and how early Church members understood the temple experience and its purposes. For example, the Book of Moses explained that Adam was baptized, received the holy priesthood and participated in its ordinances, and thus became a “son of God.” Regarding the original use of mysteries in OT1 at what is now Moses 6:59, David Calabro has observed that “the word mysteries, found in the original manuscript but later omitted, is certainly suggestive of a temple initiation”[98] that preceded Adam’s becoming a “son of God” as a pattern to be followed by his descendants in the future (see Moses 6:67–68).

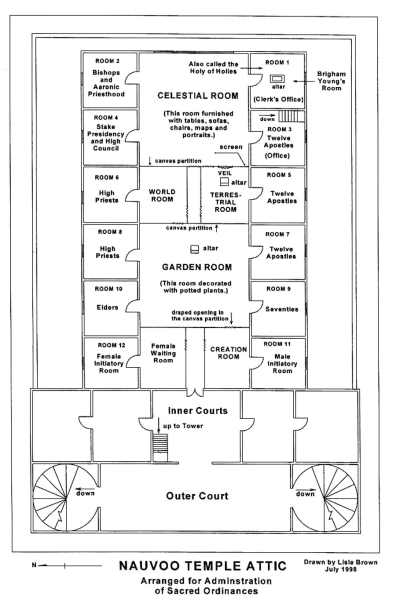

Similar to the ancient tabernacle and Solomon’s temple, the Nauvoo Temple included the architectural representation of progression and ascent to God. For temple initiates, that symbolic journey concluded in a celestial room representing the dwelling place of God and constituting the functional equivalent of the holy of holies in the ancient tabernacle.[99] Devery Anderson has noted the interrelated development of temple ordinances and temple architecture:

In a revelation on January 19, 1841, the temple received attention as a holy place where the new ordinance of proxy baptisms for the dead, initially performed in the Missouri River, could be undertaken (cf. D&C 124:37–41). . . . In addition to the familiar references to washings and anointings, the revelation hinted at greater ordinances to be revealed in connection with the temple. This understanding was reinforced by the physical layout of the temple wherein ordinances would be revealed in stages, the first being an expansion of the earlier rituals of Kirtland.[100]

Figure 5: Floor Plan of the Nauvoo Temple's Attic Story. This is where the endowment was performed. Drawing courtesy of Lisle G. Brown.

Figure 5: Floor Plan of the Nauvoo Temple's Attic Story. This is where the endowment was performed. Drawing courtesy of Lisle G. Brown.

As temple ritual evolved, it was increasingly rooted in the early garden experience of Adam and Eve, who lived in, lost, and eventually regained God’s presence as expressed in the layout of the Nauvoo Temple.

As displayed in the accompanying drawing of the Nauvoo Temple, designated areas were constructed wherein particular ordinances could be performed. These rooms included a creation room and a garden room whose construction was based on the Primeval History narratives from scripture. Accounts from those who experienced the Nauvoo Temple firsthand described the garden room as depicting events from the Creation to the lives of Adam and Eve. In essence, the architecture of the Nauvoo Temple reflected a re-creation of the early chapters of Moses, Genesis, and Abraham.

The direct connection between the temple architecture and the ancient scriptural accounts is readily apparent. The Prophet Joseph Smith had seen multiple temple plans in vision.[101]

The size of the Kirtland Temple was given by revelation in D&C 95, followed by a vision in which were provided details about its structure and design. Frederick G. Williams later recounted to Truman Angell a conversation he had with workers building the temple: “Joseph received the word of the Lord for him to take his two counselors, Williams and Rigdon, and come before the Lord, and He would show them the plan or model of the house to be built. We went upon our knees, called on the Lord, and the building appeared within viewing distance, I being the first to discover it. Then we all viewed it together. After we had taken a good look at the exterior, the building seemed to come right over us, and the makeup of the Hall seemed to coincide with [w]hat I there saw to a minutiae.” . . . Joseph Smith also saw the Nauvoo Temple in vision. . . . “I wish you to carry out my designs. I have seen in vision the splendid appearance of that building illuminated, and will have it built according to the pattern shown me.” John Pulsipher recalled that the Nauvoo Temple had been “built according to the pattern that the Lord gave Joseph” and Parley P. Pratt said that “angels and spirits from the eternal worlds” had instructed Smith “in all things pertaining to . . . sacred architecture.”[102]

As we have noted, the ritual reenactment in the temple came to consist of creation accounts and Garden of Eden scenes, all within the context of making covenants. The reenacted creation accounts articulated the concept and purposes of being created in the image and likeness of God as well as the human capacity to become like him through the covenants of the temple. This included both men and women from a very early period:

A revelation Joseph Smith dictated in January 1841 commanded the building of a temple for “your anointings, and your washings, and your baptisms for the dead” and for other ordinances yet to be revealed. (D&C 124:39, 28) In his addresses to the Relief Society in 1842, Smith anticipated the completion of this temple and exhorted women to prepare to “move according to the ancient Priesthood.” An entry in his journal had earlier stated that a restoration of the “ancient order of [God’s] Kingdom” would prepare “the earth for the return of [Jehovah’s] glory, even a celestial glory; and a kingdom of Priests & Kings to God & the Lamb forever on Mount Zion.” Smith told the women he intended “to make of this Society a kingdom of priests an [as] in Enoch’s day— as in Paul’s day.” These intentions would be realized in the temple rituals in which both women and men would participate.[103]

The Prophet Joseph Smith began administering ordinances well before the completion of the Nauvoo Temple, as is apparent from this journal entry:

4 May 1842 • Wednesday

<4> Wednesday 4 I spent the day in the upper part of the Store (I.E.) in my private office (so called, because in that room I kept my sacred writings, translated ancient records, and received revelations) and in my general business office or Lodge Room (I.E. where the Masonic fraternity met occasionally for want of a better place) in Council with General James Adams , of Springfield , Patriarch Hyrum Smith , Bishops Newel K. Whitney and George Miller ,—— —— and Presidents [HC 5:1] Brigham Young , Heber C. Kimball and Willard Richards , instructing them in the principles and order of the Priesthood, attending to washings, anointings, endowments and the communication of Keys pertaining to the Aaronic Priesthood, and so on to the highest order of Melchisedec Priesthood, setting forth the order pertaining to the ancient of Days, and all those plans and principles, by which any one is enabled to secure the fulness of those blessings, which have been prepared for the Church of the first born, and come up and abide in the presence of the Eloheim in the Eternal worlds. In this Council was instituted the Ancient order of things for the first time in these last days. And the communications I made to this Council were of things Spiritual, and to be received only by the Spiritual minded: and there was nothing made known to these men, but what will be made known to all <the> Saints of the last days, so soon as they are prepared to receive, and a proper place is prepared to communicate them, even to the weakest of the Saints; [p. 1328]

<May 4> therefore let the Saints be diligent in building the Temple , and all houses which they have been, or shall hereafter be commanded of God to build; and wait their time with patience, in all meekness, faith and perserverance unto the end, knowing assuredly that all these things referred to, in this Counsel, are always governed by the principle of Revelation.[104]

The preparations for this event included the re-creation of scriptural texts. Latter-day Saints continue to reenact scripture in a very similar way today:

In contrast to written scripture, the endowment taught participants by inviting them to symbolically reenact key aspects of the plan of salvation, including “the most prominent events of the creative period, the condition of our first parents in the Garden of Eden, their disobedience and consequent expulsion from that blissful abode, their condition in the lone and dreary world when doomed to live by labor and sweat, the plan of redemption by which the great transgression may be atoned.” During the course of this reenactment, they covenant to obey God’s commandments, commit to devote themselves fully to His work, and acquire knowledge needed to “walk back to the presence of the Father.”[105]

Red Brick Store and the ordinances

The Saints’ return to the presence of God constituted the supreme objective of the restored gospel, and the temple pattern and ancient texts with their attendant covenants and ordinances provided the mechanism to accomplish that goal. Before the Nauvoo Temple’s completion, Joseph Smith’s Red Brick Store furnished a temporary “house” for such purposes. Bathsheba Wilson Bigler Smith, wife of Apostle George Albert Smith, explained that “in company with my husband, I received my endowment in the upper room over the Prophet Joseph Smith’s store. The endowments were given under the direction of the Prophet Joseph Smith, who afterwards gave us lectures or instructions in regard to the endowment ceremonies.”[106] Accounts explain that in preparation for administering the endowment, the store’s upper room was partitioned off (like the Nauvoo Temple), potted plants were brought in to re-create a Garden of Eden, and a veil was hung to separate the holy place of God.[107] Brigham Young recalled the following:

When we got our washings and anointings under the hands of the Prophet Joseph at Nauvoo, we had only one room to work in with the exception of a little side room or office where we were washed and anointed, and had our garments placed upon us and received our New Name. After he had performed these ceremonies, he gave the Key Words, signs, tokens, and penalties. Then after this we went into the large room over the store in Nauvoo. Joseph divided upon the room the best that he could, hung up the veil, marked it, gave us our instructions as we passed along from department to another, giving us signs, tokens, penalties with the key words pertaining to those signs. After we had got through, Brother Joseph turned to me [Pres B. Young] and said. “Brother Brigham this is not arranged right but we have done the best we could under the circumstances in which we are placed.”[108]

After the Prophet’s death, Brigham Young became responsible for refining the ordinances. Later accounts describe worship in the pioneer temples out west and include fascinating details such as John Taylor portraying a cherub armed with a sword guarding the way back to God in the Garden of Eden, people representing Adam and Eve, and even ritual scenes portraying Satan within the garden, details we find specifically included in the Book of Moses. Through it all, the Book of Moses served a quintessential role in the revelatory unfolding of temple worship and the developing concept of the Saints’ journey toward eternal life. The Prophet Joseph Smith explained the reason behind temple worship in all ages:

What was the object of Gathering the Jews together or the people of God in any age of the world, the main object was to build unto the Lord an house whereby he could reveal unto his people the ordinances of his house and glories of his kingdom & teach the peopl[e] the ways of salvation. . . . It is for the same purpose that God gathers togethe[r] the people in the last days to build unto the Lord an house to prepare them for the ordinances & endowment washings & anointings &c.[109]

From the start, the Prophet Joseph Smith viewed the restoration of temple ordinances and worship as a most serious matter:

The Lord commanded us, in Kirtland, to build a house of God; . . . this is the word of the Lord to us, and we must, yea, the Lord helping us, we will obey: as on conditions of our obedience He has promised us great things; yea, even a visit from the heavens to honor us with His own presence. We greatly fear before the Lord lest we should fail of this great honor, which our Master proposes to confer on us; we are seeking for humility and great faith lest we be ashamed in His presence.[110]

Joseph Smith’s translation of the Bible (including the Book of Moses) and other ancient scripture such as the Book of Mormon and the Book of Abraham, together with the ongoing revelations received in conjunction with their reception, was the Lord’s way of unfolding and developing in the dispensation of the fulness of times everything that those books of scripture taught about God’s purposes for his children. The teachings of ancient and modern scripture and the words and direction of ancient and modern prophets came to fruition in covenants made and ordinances performed in temples.

Conclusion

From the beginning of Joseph’s reception of Moses 1, which recounted Moses’s encounter with God “face to face” atop a mountain-temple, and his subsequent translation of the creation and Eden accounts from the Bible, Joseph’s revelations on the temple would grow and intertwine with his understanding of these texts. Throughout the next fourteen years (1830–1844), Joseph Smith labored with all urgency to fulfill the commission to build temples that would enable the Latter-day Saints to have the Moses-like temple experience of being restored to the presence of God. During the remainder of his life, the Prophet received an abundance of revelation on the temple that centered on the story of Adam and Eve and the Garden of Eden as depicted in the Book of Moses. Before the completion of the Nauvoo Temple, he administered Eden-centric temple ordinances in the Red Brick Store. He and the Saints gave their all to complete a temple in Nauvoo with architecture that included a ritual replication of Eden and represented the progressive ascent to, or journey back into, the presence of God.

After the Latter-day Saints were expelled from their homes and temple again and settled in the West, they built temples like the Nauvoo Temple that conformed to the tripartite cosmological design of the ancient tabernacle and temple of Solomon with their architectural replications of Eden. Through it all, the Book of Moses remained an important resource as temple ritual and architecture developed. The experiences of Adam, Eve, Enoch, Noah, and Moses all found ritual expression in the temple worship that took shape. The Book of Moses remains an important resource for the Latter-day Saints today as the temple ritual continues to evolve and the words of the Book of Moses continue to be incorporated into the endowment.

Notes

[1] See McBride, House for the Most High, xix–xx; Doctrine and Covenants 57:1–4 (July 20, 1831); and History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834], p. 127, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[2] See Covenant of Oliver Cowdery and Others, 17 October 1830, p. [1], The Joseph Smith Papers.

[3] Quoted in Ricks and Carter, “Temple-Building Motifs,” 156; see Minutes, 27–28 December 1832, p. 3, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[4] Bradshaw and Larsen, in In God’s Image, 2:519, suggest, “Contrary to the common belief that the highest temple ordinances were not anticipated until the last few years of Joseph Smith’s ministry, several references to temple-related concepts occur in his early revelations.” Bradshaw has additionally argued that “the divine tutorial that took place during Joseph Smith’s Bible translation effort was focused on temple and priesthood matters.” Bradshaw, In God’s Image, 1:3–6. See also Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Book of Moses, 13–16; Bradshaw, “Sorting Out the Sources in Scripture,” 267n205; and, generally, Bradshaw, “What Did Joseph Smith Know about Modern Temple Ordinances?”

[5] See Anderson, Development of LDS Temple Worship, xxv; and Anderson and Bergera, Joseph Smith’s Quorum of the Anointed, ix. Some of the earliest revelations and heavenly manifestations, beginning with at least Moroni in 1823 (see Doctrine and Covenants 2; Joseph Smith—History 1:36–39), focused on temple-related themes and priesthood authority that would eventually be instrumental in performing ordinances in temples.

[6] Howlett, Kirtland Temple, 21.

[7] For the development of temple ritual and worship, see Buerger, Mysteries of Godliness, 1–58; and Anderson and Bergera, Joseph Smith’s Quorum of the Anointed, xvii.

[8] Buerger, in Mysteries of Godliness, 73, states that no written text of the 1842 or 1843 rituals exists and that by 1845 we start getting written descriptions of the ordinances and their administration. “The secrecy also generated opportunities to create a wholly oral canon, free from the incursions of literality, because the Saints not only couldn’t speak about it outside the temple, they couldn’t write it down for later perusal. In essence, temple secrecy was an agreement that certain things were so intrinsically ineffable that one mustn’t even try to contaminate them with immanent language. In Kathleen Flake’s classic argument, this allows for a fluidity that looks like fixity. They are playing at the interface of textuality and orality. There are things that can’t be spoken, and the temple is the place for many of them.” Brown, Joseph Smith’s Translation, 259.

[9] See Buerger, Mysteries of Godliness, 37, 41–43, 74ff.; Smith, in History of the Church, 5:2; Givens and Hauglid, Pearl of Greatest Price, 4; and Brown, Joseph Smith’s Translation, 244–45. “Heber C. Kimball wrote to his fellow Apostle Parley P. Pratt, who was not in Nauvoo when the endowment was first given, ‘I cannot give them to you on paper for they are not to be written.’ In contrast to written scripture, the endowment taught participants by inviting them to symbolically reenact key aspects of the plan of salvation. . . . Joseph Smith never described how the endowment came to be, and there is no recorded revelation outlining its content. However, Willard Richards, who was among the few to receive the endowment from Joseph Smith, testified that the ordinance was ‘governed by the principles of Revelation.’” “Temple Endowment,” Church History Topics. See Heber C. Kimball Letter, Nauvoo, to Parley P. Pratt, June 17, 1842, Church History Library.

[10] Brown, Joseph Smith’s Translation, 269–70.

[11] “That central attribute of the Nauvoo temple liturgy [anointing and ordaining individuals to become kings and priests unto God (and queens and priestesses)—i.e., deification] ought not to be forgotten. Ritualistically, in the temple rites the Latter-day Saints were acting out the broader journey their lives were meant to take. The journey was spatial within the endowment, but it was also ontological. The worshipers were moving into heaven as they were becoming the kinds of beings who could physically tolerate the actual divine presence. . . . [Temple ritual] was the promise that people were more than they appeared to be.” Brown, Joseph Smith’s Translation, 252.

[12] Brown, In Heaven as It Is on Earth, 225n119. Temple worship encapsulated everything that Joseph Smith had learned through revelation about the nature of God and his children, as well as his purposes for their being created in his image and likeness.

[13] “In the temple the established binaries—past and present, human and divine, spirit and body—merged in anticipation of the utter transformation of human beings. The constituents continued to exist in their own right even as they were melded together.” Brown, Joseph Smith’s Translation, 264.

[14] Givens and Hauglid, Pearl of Greatest Price, 263. “Enoch, Elijah, Moses, Alma, and the Latter-day Saints in their temple were all tasked with taking mere physical human beings and placing them into the unmediated presence of God. They were called to translate, to scintillate between the two realms or states of being. [Joseph] Smith was advocating that his followers understand themselves as capable of being human and divine, immanent and transcendent—though not necessarily at the same time. They would have to flit between the two.” Brown, Joseph Smith’s Translation, 265. This chain of belonging was articulated as a welding link, resulting in “a whole and complete and perfect union, and welding together of dispensations, and keys, and powers, and glories should take place . . . from the days of Adam even to the present time” (Doctrine and Covenants 128:18). Ordinances performed under the authority of the priesthood would enable such a welding link. See Mackley, Wilford Woodruff’s Witness, 62; and Doctrine and Covenants 128:14, 18.

[15] Joseph Smith’s early identification of Jackson County, Missouri, is clear from later statements made by Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball. Brigham Young recalled, “Joseph the Prophet told me that the garden of Eden was in Jackson [County] Missouri.” See Kenney, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, March 15, 1857, 33. Heber C. Kimball also reported, “From the Lord, Joseph learned that Adam had dwelt on the land of America, and that the Garden of Eden was located where Jackson County, Missouri, now is.” Jenson, Historical Record, 7:439; see Whitney, Life of Heber C. Kimball, 219. Citing the foregoing examples, Bruce Van Orden has further noted that “other early leaders have given the same information.” Van Orden, “What Do We Know about the Location of the Garden of Eden?,” 54–55.

[16] See, e.g., Volluz, “Lehi’s Dream of the Tree of Life,” 14–38 (especially p. 35); Parker, “Doctrine of Christ in 2 Nephi 31–32,” 161–78; and Reynolds, “‘This Is the Way,’” 79–91.

[17] Brown, Joseph Smith’s Translation, 246.

[18] Givens and Hauglid, Pearl of Greatest Price, 125.

[19] The following time line is not exhaustive but representative of important events.

[20] See discussion in MacKay, “Event or Process?,” 80.

[21] See John Whitmer, History, 1831–circa 1847, p. 32, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[22] See Minutes, 25–26 October 1831, p. 11, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[23] Anderson and Bergera, Joseph Smith’s Quorum of the Anointed, xiii.

[24] See Minutes, 22–23 January 1833, p. 7, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[25] See “Kirtland Temple,” Church History Topics.

[26] Letter to the Church, circa March 1834, p. 144, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[27] Journal, 1835–1836, p. 3, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[28] See Journal, 1835–1836, p. 135, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[29] Journal, 1835–1836, p. 151[a], The Joseph Smith Papers.

[30] Baugh, “Mormon Temple Site,” 80–81.

[31] Olmstead, “Far West and Adam-ondi-Ahman,” Revelations in Context.

[32] History, 1838–1856, volume C-1 [2 November 1838–31 July 1842], p. 9 [addenda], The Joseph Smith Papers.

[33] See Letter to Quorum of the Twelve, 15 December 1840, p. [6], The Joseph Smith Papers.

[34] See McBride, House for the Most High, 3.

[35] Anderson and Bergera, Joseph Smith’s Quorum of the Anointed, xviii.

[36] See “Celebration of the Anniversary of the Church,” Times and Seasons, 376–77.

[37] See Wilford Woodruff Journal, November 21, 1841; and “An Epistle of the Twelve,” 779.

[38] See Introduction to Facsimile Printing Plates and Published Book of Abraham, circa 23 February–circa 16 May 1842, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[39] Journal, December 1841–December 1842, p. 94, The Joseph Smith Papers; see Nauvoo Relief Society Minute Book, p. [34], The Joseph Smith Papers.

[40] Discourse, 1 May 1842, as Reported by Willard Richards, p. 94, The Joseph Smith Papers; see Kenney, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, June 27, 1839, 341.

[41] See Journal, December 1841–December 1842, p. 94, The Joseph Smith Papers; and History, 1838–1856, volume C-1 [2 November 1838–31 July 1842], p. 1328, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[42] See History, 1838–1856, volume D-1 [1 August 1842–1 July 1843], p. 1561, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[43] Discourse, 11 June 1843–A, as Reported by Wilford Woodruff, p. [42], The Joseph Smith Papers.

[44] See Discourse, 27 August 1843, as Reported by Willard Richards, pp. [74]–[75], The Joseph Smith Papers.

[45] See Editor, “January,” Times and Seasons, January 15, 1846, 1096.

[46] See Kenney, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, April 30–May 1, 1846, 41–42.

[47] Brown, Joseph Smith’s Translation, 249.

[48] Brown, Joseph Smith’s Translation, 247. This concept of the eternal nature of the gospel is discussed in chapter 4 of the present volume.

[49] In Exodus 3:12, during the burning bush theophany, Moses learned that God had sent him to deliver Israel from Egypt with the intent that they would all serve God on “this mountain.” Moses’s experience and theophany with God was to be all of Israel’s experience. God then revealed his name to Moses (see v. 14) as a means of identifying the theophany and the mountain experience, signifying his intent to personally commune with Moses.