Conclusion and Charge

Jeffrey R. Holland

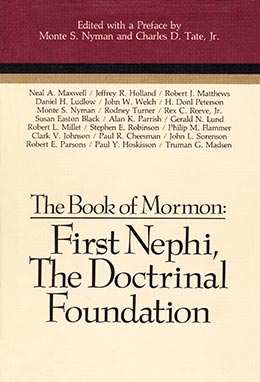

Jeffrey R. Holland, “Conclusion and Charge,” in The Book of Mormon: First Nephi, The Doctrinal Foundation, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1988), 315–23.

Jeffrey R. Holland was president of Brigham Young University when this was published.

May I express my deep personal appreciation for all who have organized, prepared, attended, and participated in this second annual symposium on the Book of Mormon. I am very proud of the Religious Studies Center at Brigham Young University and the Religious Education administrators and faculty who carry the lion’s share of the responsibility for pursuing the work of the center. It is one of my highest personal hopes that the Religious Studies Center will be an extremely visible and very influential agency on the Brigham Young University campus, stimulating the strongest and best kind of religious research underscoring and reaffirming the truths of the Restoration.

I am also in hopes that the center and its work will involve not only all of our Religious Education faculty at BYU but also many of our colleagues from the full range of disciplines across the campus and that we will reach beyond the campus to friends, adjunct scholars, and interested participants the Church over. I realize that geography and travel hold some limitations for us, but we hope that just such events as this Book of Mormon symposium will continue to make BYU the center of strong, reliable teaching and research in all of the areas that are of doctrinal importance to the kingdom of God in these last days.

In that spirit I thank all of you for your participation and attendance here these past two days. I only wish I could have been in every session for every hour. I am very proud of your accomplishments and wish to conclude this symposium with a strong expression of encouragement for next year’s topic, for the year after that, and so forth. We have an everlastingly rich source of doctrinal ore here to mine, especially in the Book of Mormon, and I encourage all of us to participate in that task. BYU intends to facilitate your work and give expression to it.

May I just add something of my own personal testimony to the theme that has been pursued at the symposium. I commend Dean Robert Matthews, Associate Dean Monte Nyman, and all who have assisted them for their decision to have us focus on a manageable segment of the Book of Mormon and, in effect, work our way through the book over the next several years. That manageable but immensely rich segment for this symposium has been 1 Nephi, “The Doctrinal Foundation.”

I don’t know just where I was in my teaching career when I began to realize what remarkable pieces of material 1 Nephi specifically and the small plates of Nephi generally really were. I suppose all of us have wondered about the detail and doctrine that were lost with the disappearance of that initial 116 pages of Book of Mormon manuscript. Indeed, one of my fantasies since youth has been that I would be the one rummaging around in an old attic or library somewhere and would discover those manuscript pages. I would then triumphantly bear them off as a gift to the President of the Church. I guess that is still kind of a fun fantasy to have, and if any of you have suggestions about old attics in which I should be rummaging, I’m open to suggestion.

Nevertheless I have long since come to believe that when the Lord in his omniscient wisdom foresaw the Martin Harris problem and planned for its remedy more than two thousand years in advance of that loss, he knew full well what our needs would be and provided in that replacement matter (that is, the small plates) perhaps an even richer resource for our study and edification than those initial 116 pages of abridged material would have proven to be. I do not want this to sound like heresy, much less even hint that I’m glad the 116 pages were lost, but if such a loss is what it took in order for us to have 1 Nephi and the rest of the small plates given to us, so be it. I confess I cannot imagine what the Book of Mormon would be without those first 145 printed pages you and I now enjoy.

I suppose I am intrigued with this introductory material in part because all of us have to be intrigued—and captivated and led on and inspired—by how a book begins, or else we are likely not to read the rest of the book at all. My life and library contain a lot of books in which I have read the first fifty or seventy-five pages and then have closed the books, never to read there again. Patience is not one of my great virtues, and if a book cannot say something to me forcefully and well somewhere in the course of its first pages, I am not very sanguine that it is going to say much to me thereafter. Perhaps that is an unfair judgment to make, but it is one I do make regularly as a reader, and perhaps you do as well.

For that reason truly great books, and I believe virtually all even reasonably good books, have a strong, compelling beginning. We have been agreeing with Aristotle ever since he said that “a good book must have a calculated structure and development which gives a unified impact from beginning to end.” [1] I believe that by Aristotle’s standard the Book of Mormon is not only a good book; it is a classic. In spite of the fact that it is written by a series of prophets who had different styles and different experiences, in spite of the fact that it has some unabridged materials mixed with others that have been greatly condensed, in spite of the fact that it has unique and irregular chronological sequences, it is nonetheless a classic book—indeed, Aristotle’s kind of book: unified, whole, verses fitting with verses, chapters fitting with chapters, books fitting with books, and always that strong beginning.

Several years ago I was asked to write on this subject for the Ensign magazine, and there I tried to suggest, particularly for a younger reading audience, that in the first chapter of 1 Nephi, twenty carefully written and powerfully stage-setting verses, a great deal is said about what the rest of the Book of Mormon is going to be. Now, putting aside some other very important items that occur even in such a brief chapter, we note that a rough outline of those first twenty verses indicates that

- A prophet prays

- He has a vision

- In the vision he sees heavenly messengers (including Jesus Christ)

- In the vision he receives a book filled with remarkable truths and prophecies

- He is rejected by most of the people

For me it cannot be coincidental that Lehi’s experience at the beginning of this book parallels so closely that of Joseph Smith’s. For one thing, I believe all prophets have some special experiences in common. One thing we know they have in common is receiving revelation from the Lord, revelation that often gets canonized in books of scripture. Furthermore, it seems to me that this parallel experience, sketchy as it is, links an older dispensation of prophets who lived the Book of Mormon experience with a modern-day prophet who would translate and reveal it to the world. That is just one more way in which we realize that if we accept Lehi and the Book of Mormon, we surely have to accept Joseph Smith as a prophet of God: the former cannot be seen as an authentic, ancient prophet without acknowledging the divine work of the latter which revealed such a fact to the world. On the other hand, when we accept Joseph Smith as a prophet we surely must accept and faithfully seek to live by the teachings of Lehi and the others who follow him in this record, because a true prophet will bring forth true teachings.

This first chapter of 1 Nephi is just one of those impressive ways by which revelation leaps the traditional impediments of time and space, giving great unity to the dispensations and to the doctrinal truths of the kingdom which characterize and connect them. In that sense the Book of Mormon is not only the testimony of Nephi and Alma and Mormon and Moroni, but it is also the testimony of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young and Spencer W. Kimball and Ezra Taft Benson. Just as all scripture is, in a sense, one in God’s hand, so are all the prophets who provide it.

Above all, what this chapter and the rest of 1 Nephi says to us—and for my purposes here, what the entire Book of Mormon says to us—is that revelation is indeed the great binding mortar of this dispensation and of every dispensation. The Prophet Joseph said that revelation is the rock on which the Church of Jesus Christ will always be built and that there can never be any salvation without it. [2] That is the principle we are forced to deal with in the opening verses of 1 Nephi, and we continue to be inundated with it through all of 1 Nephi. It is clear to us very early that revelation is what the book is about, and if we do not accept that principle rather quickly we are in trouble on the very first page of the book.

I have already noted Lehi’s revelatory experience in chapter 1. Notice how chapter 2 begins. “For behold, it came to pass that the Lord spake unto my father, yea, even in a dream, and said unto him. . . .”

Chapter 3: “And it came to pass that I, Nephi, returned from speaking with the Lord. . . . And . . . [my father] spake unto me, saying: Behold I have dreamed a dream, in the which the Lord hath commanded me. . . .” Later in the chapter an angel appears and speaks.

Chapter 4 tells of Nephi being led by the Spirit, not knowing beforehand the things which he should do.

Chapter 5 speaks of the plates of brass (scripture), giving some general outline of their doctrinal, historical, and genealogical contents.

Chapter 6 is an editorial comment about the value of scripture.

Chapter 7 simply continues the theme: “After my father, Lehi, had made an end of prophesying concerning his seed, it came to pass that the Lord spake unto him again. . . .”

Chapter 8, of course, tells of that remarkable first vision of the tree of life. The chapter begins with Lehi’s declaration—again—"Behold, I have dreamed a dream; or, in other words . . . seen a vision”; and then the stunning details of that well-known vision unfold.

Chapter 9 is an editorial comment from Nephi about why the small plates had been recorded, and chapter 10 contains the first extensive Book of Mormon commentary on the Savior of the world. Nephi, speaking of his father’s sermon, says, “He also spake concerning the prophets, how great a number had testified of these things, concerning this Messiah, of whom he had spoken, or this Redeemer of the world.”

Then, of course, in chapter 11 Nephi takes his own rightful place as one of those prophets when he is led by the Spirit to see all that his father had seen and eventually much more, a vision of remarkable content and detail and revelatory impact.

That is enough, sketchy as it is, to suggest the incessant revelatory nature of these opening chapters. Prophets, dreams, angels, visions, scripture, promptings of the Spirit, more prophets, more visions—they come in every chapter, on every page. By the time we get to 1 Nephi 15 or so we have dealt with almost every conceivable form of divine revelation and yet are only thirty pages into the book. Again it strikes me that at this point the intellectually honest reader must make a very fundamental concession: the Book of Mormon presupposes the reality of revelation. Indeed in some ways it is one long revelation about revelation. If that premise is unacceptable to the reader, as it unfortunately is to some, that is why (it seems to me) he or she may as well close the book and conclude the reading, as some unfortunately do.

Consider the role this special book of revelation(s) played in the sequence of the Restoration. With the book finally published in the last days of March 1830, the stage was set for the organization of the Church just days later on the sixth of April. The Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ and its institutional church would have everything to do with and everything to say about revelation. Indeed its principal document, the Book of Mormon, was written, watched over, preserved, revealed, translated, published, and carried to the world to declare—again—that revelation had not ceased, that the heavens were again open, that God does speak to men. Nothing else that Samuel Smith and those early missionaries would teach could have much impact if that cardinal, fundamental truth about revelation was not accepted by the people they taught.

And so it still is today. That confrontation with revelation and the reality of God’s direction to his prophets is part of the intellectual sequence and spiritual journey into which the reader of the Book of Mormon is immediately forced to step. I believe if we are still reading after the first thirty pages, and reading with intent and honesty and examination, we are ineluctably on our way to accepting not only a millenium of Nephite history but also the boy prophet and the restored Church which published it to the world. All of the revelatory grandeur of the Restoration, with all of its glory and abundance, lies just beyond 1 Nephi. No wonder the book begins the way it does.

Let me suggest another thing that I believe is happening in 1 Nephi. I mentioned earlier that I believed this was a superbly crafted book, verses fitting with verses and chapters fitting with chapters. Somewhere along the way, as we read 1 Nephi, we realize that these revelatory experiences just alluded to are posing a seemingly endless series of confrontations and choices. Lehi is one kind of local leader, his relative Laban is another; Nephi is one kind of son, Laman is another; and so forth, ad infinitum.

If we read for a while we inevitably begin making something of a mental list showing this significant string of alternatives—all in 1 Nephi: Lehi versus Laban, Nephi and Sam versus Laman and Lemuel, New Jerusalem versus Old Babylon, the tree of life versus the depths of hell, the virgin mother of Christ versus the harlot mother of abominations, the church of the Lamb of God versus the church of the devil, and of course ultimately what we are seeing by the end of 1 Nephi is simply Christ versus Satan.

Along such a path of choices and alternatives we come, with some difficulty, through the wilderness of mortal life, finding virtually no good that seems not to be countered by an opposite evil.

“Opposition in all things.” Now, that is a phrase with a familiar ring to it. I suggest it is not accidental that such extensive and skillful preparation is laid in 1 Nephi for the doctrinal exposition we fill find in 2 Nephi. That book, of course, contains one of the greatest scriptural discourses in all the Book of Mormon (and all scripture, I might add) on opposition in all things, dramatized by the issues surrounding the Fall of Adam and the Atonement of Christ.

I am sure that Lehi could have given a mighty sermon (or, in this case, a patriarchal blessing) on opposition and agency somewhere back in 1 Nephi, but how much more powerful it is for his sons and for us as readers to have lived through fifty pages of such confrontations and alternatives before we hear it verbalized as a doctrinal issue. The faithful few in that little family have had about as much “opposition in all things” as they can stand, but it has taught them something about themselves, about a fallen world, about the plan of God, about the majesty of Christ, and about the eternal exercise of choice.

It would seem, then, that all the hardships of 1 Nephi have had significant purpose in pointing us toward the doctrinal climate of 2 Nephi and the figure of Christ which will entirely dominate that book, including the Isaiah chapters that are included there. I suppose, in a sense, I am being led into next year’s symposium sequence. But then that is part of my point. It is very hard—and sometimes even dangerous—to read the Book of Mormon piecemeal. It has been carefully edited and its text highly selected for a particular purpose. I believe those purposes blend together from cover to cover. As a practical matter we have to divide the book up to study it, but it is clear to me that we will read it best and help our students read it best when we keep returning to it in the grand sweep that starts at the first and continues to the last, giving a wholeness and unity to the book, to the dispensations, and to our view of the gospel plan.

With that I close. About a year or eighteen months ago I was struggling with a very real and very difficult problem. It was as difficult as anything I had faced for a long time, and it had implications for the university and for me personally. I struggled and hurt and ached and prayed. I wondered whether peace would come and answers would be provided. I think I must have felt at least a little as Lehi felt traveling for the space of many hours in a dark and dreary waste. You have had those struggles too.

One weekend when I was alone with my own thoughts and praying about this problem, I was prompted to pick up the Book of Mormon and open it at random. I do not intend to make too much out of such an act, and I do not suggest that every random opening of the Book of Mormon is heaven directed, but I felt there was a message for me that day and I would be led to something that was important for me to know.

I got up off my knees and opened the book and these are the words I read directly:

They said unto me: What meaneth the rod of iron which our father saw, that led to the tree?

And I said unto them that it was the word of God; and whoso would hearken unto the word of God, and would hold fast unto it, they would never perish; neither could the temptations and the fiery darts of the adversary overpower them unto blindness, to lead them away to destruction.

Wherefore, I, Nephi, did exhort them to give heed unto the word of the Lord; yea, I did exhort them with all the energies of my soul, and with all the faculty which I possessed, that they would give heed to the word of God and remember to keep his commandments always in all things.” (1 Nephi 15:23–25)

That is my prayer for all of us as we continue to study the Book of Mormon. To the extent that I have a charge as outlined in the symposium schedule, my charge is to cling to that rod of iron, to cherish the word of God, to study it as the ancient Israelites were commanded to study the law, “both day and night,” to have us meet here again one year from now to continue our exchange and study and enlightened discourse on this “most correct of any book on earth” (Book of Mormon introduction, 1981 edition). I believe that, like these travelers in 1 Nephi, we too will “search them [the scriptures] and [find] that they [are] desirable; yea, even of great worth unto us, insomuch that we could preserve the commandments of the Lord unto our children. Wherefore, it [is] wisdom in the Lord that we should carry them with us, as we [journey] in the wilderness towards the land of promise” (1 Nephi 5:21–22).

May we so search and journey together, with our grasp firmly on the rod of iron, I pray, in the name of Jesus Christ, Amen.

Notes

[1] Richard McKeon, ed., The Basic Works of Aristotle, (New York: Random House, 1941).

[2] Joseph Fielding Smith, comp., Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 274.