Laws and Commandments

Roger R. Keller, “Laws and Commandments” in Book of Mormon Authors: Their Words and Messages (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 21–39.

In chapter 1, a methodology using word clusters was developed which suggested that unique word usage could be identified among the various Book of Mormon authors. This chapter and those that follow are designed to test that suggestion.

When Latter-day Saints think of the Lord’s commandments, they frequently think of paying tithing, living the law of chastity, attending meetings, performing temple ordinances, following the Brethren, and magnifying callings. This would hardly be an exhaustive list of “commandments,” however, and the list varies from person to person, depending on circumstances. Why do we have commandments anyway? What is the Lord’s purpose in giving them to us? This chapter will attempt to answer these questions by examining the authors within the Book of Mormon and their use of the words related to Law/

This chapter will extend the research explained in chapter 1. Here a comparative methodology has been applied to a very specific and narrow set of words. While the previous chapter dealt with large groups of words centered around specific themes, here we deal with a small group of eleven words related to Law/

Two things will be seen as a result of this study: (1) there are significant differences in the ways the words are used by the various authors; and (2) according to Jesus, all laws and commandments given by God lead to only one commandment—”Come unto Christ.”[2]

Significant Use of the Law/

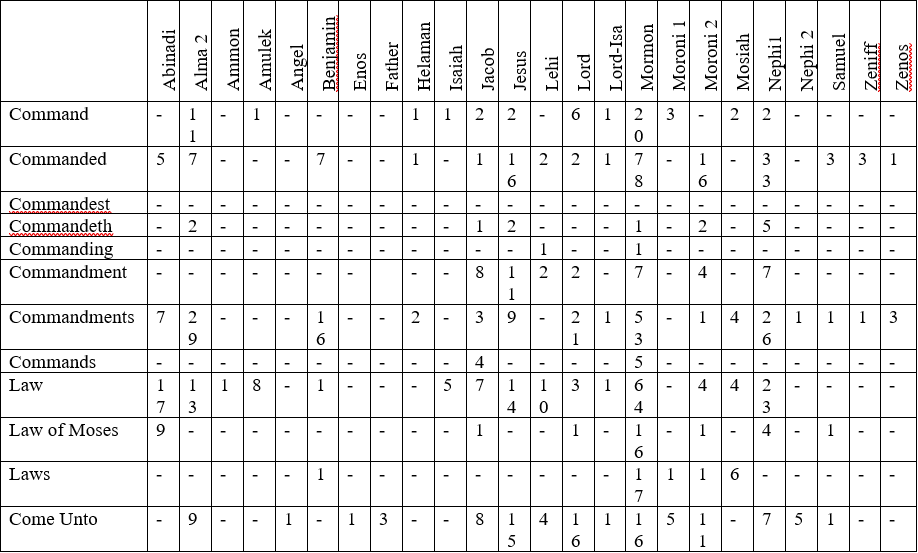

Figure 1 shows how the use of this word group is distributed across the various authors. Listed are simply the number of occurrences of the various words. Their use ratios will be noted in the text or in footnotes.

Even a cursory glance at figure 1 makes it clear that there are variations between the authors in their choice of words. Command, Commanded, Commandment, and Commandments are most generally used, but there are clear differences in who chooses to use what. Similarly, many of the authors speak of Law, but not all refer explicitly to the Law of Moses. Finally, a number of the authors use the phrase Come Unto, and we will explore what each means by the special use of that phrase. We will divide the following material into three categories which deal with various meanings and contexts for these words, i.e., ethical and secular, theological, and editorial. Finally, we will turn to Jesus’ theological key which unlocks the ultimate meaning of this complex of words.

A Predominantly Secular or Ethical Meaning

The Law/

Alma 2.

For Alma 2, the Law/

The word Law focuses most clearly on the secular/

This occurrence immediately follows Alma 2’s question to the people of Zarahemla asking whether they have been spiritually born of God. He then asks them about their faith in God and if they are prepared to be judged against the deeds they have done while in their mortal bodies—i.e., judged against their ethical behavior. Would they be invited to come to God because of their righteousness, or would they be filled with remorse and guilt because they violated God’s commandments (Alma 5:14–18)?

For Alma 2, a person’s spiritual relationship with God (Alma 5:14) was clearly a precursor to all that followed ethically, yet ethics—living by God’s commandments—did matter (Alma 5:16, 18). Other texts show a similar spiritual/

The word which reinforces the above relationship between spirituality and ethics is Command. On the one hand, Command has the rather mundane meaning of ordering or directing someone to keep the records (Alma 37:1–2) or not to impart certain knowledge (Alma 12:9, 14; 37:1–2,16,20,27; 39:10,12). On the other hand, Command appears in Alma 5:60–62 as the culmination of a magnificent chapter on the work of Christ. Clearly the ethical element is present, but of even greater importance is the emphasis on coming to Christ, repenting, and being baptized.

Amulek.

Amulek makes almost no use of the Law/

Benjamin.

The Law/

Commandments carries a strong ethical context (Mosiah 1:3–4; 2:13, 21–22), but there is the added dimension of being commanded to know the history of God’s dealings with his people, thereby placing ethics within God’s promises of redemption (Mosiah 1:5–7,11; 2:41; 4:6, 30). Even the king’s commandments are the commandments of God (Mosiah 2:31).

Benjamin’s use of Commanded sharpens the picture, for he makes it clear that service to one’s fellow human beings is the essence of God’s commands (Mosiah 2:13,17,23,27). In addition, Benjamin is commanded to reveal the mysteries of God to his people (Mosiah 2 2–10), the essence of which seems to be “that ye are eternally indebted to your heavenly Father, to render to him all that you have and are” (Mosiah 2:34). Such knowledge came from the records, the holy prophets, and the fathers (Mosiah 2:34–35).

Mosiah.

Proportionately, the Law/

Nephi 1.

Nephi l’s use of the Law/

Almost universally in Nephi l’s writings, the word Commandments means instructions, a meaning that is unique to Nephi 1. Of the twenty-eight occurrences of the word, twenty bear the meaning of instructions,[8] while of the remaining eight occurrences, three others may mean this in part (1 Nephi 22:30–31; 2 Nephi 31:7).

The word Law always means the Law of Moses (e.g., 1 Nephi 4:15; 2 Nephi 25:25–30), and where Law of Moses is used explicitly, Nephi 1 tells us that it points toward Christ (2 Nephi 11:4) or is to be kept until Christ comes (2 Nephi 25:24).

Summary.

Among those authors who use the Law/

From these examples, one observes precisely what one would expect to see among different authors whose works had been edited and recorded in a single volume—diversity in language and diversity in the meanings attached to a single word. Figure 2 is a summary table of the above results.

|

SECULAR/ |

|

|

Alma 2 (3.03) |

|

|

Commandments |

Ethical and lead to righteousness |

|

Living by God’s directions |

|

|

Fulfilled in relation to Christ |

|

|

Law |

Secular or Law of Moses |

|

Amulek (2.52) |

|

|

Law |

Secular |

|

Benjamin (5.92) |

|

|

Commandments |

Ethics or know the history of God |

|

Commanded |

Service |

|

Mosiah (14:41) |

|

|

Commandments |

God’s commands the basis of secular law |

|

Laws |

Secular laws |

|

Nephi 1 (2.92) |

|

|

Commandments |

Instructions on daily issues |

|

Law |

Law of Moses |

A Predominantly Theological Meaning

In this section, the Law/

Abinadi.

For Abinadi, the Law/

When Abinadi uses Commanded, it is almost always in the context of God commanding persons, through Abinadi’s preaching, to repent (Mosiah 11:20–21,25; 12:1; 13:3; 16:12) and, in the broader context, to come to Christ and his atonement. The people’s repentance must focus on their violation of the Ten Commandments, which clearly state God’s will for them (Mosiah 12:33; 13:4, 11,25; 15:22, 26). The priests of Noah claim that salvation comes through the Law of Moses, but Abinadi gives an interesting twist to that argument. He says he knows that if they keep the commandments of God, they will be saved. He then quotes the beginning of the Ten Commandments: “I am the Lord thy God, who hath brought thee out of the land of Egypt.. . . Thou shalt have no other God before me” (Mosiah 12:34–36). Abinadi’s basic charge is that the priests of Noah have not kept God foremost in their lives, thereby giving rise to all their other sins (Mosiah 12:37). Thus, the Law of God is central, but specifically the law which places the person of God and one’s relationship with him above all other things. When the Law of Moses is rightly understood, it is a type of him who is to come (Mosiah 13:31–32; 16:14). Until such time, the ordinances are given to keep the remembrance of God constantly before the people (Mosiah 13:29–30).

Jacob.

Jacob uses most of the Law/

Jacob’s use of the word Law appears, in part, to mean the Law of Moses. But it goes beyond this to a sense that is equivalent to the plan of salvation, for it seems to encompass the work of Christ and God’s overall purposes (2 Nephi 9:17, 24–27, 46). Finally, the Law of Moses points souls to Christ (Jacob 4:5). Hence, Jacob’s use of the word group is different from that of other authors in that there is not a dominant theme attached to the word group.

Moroni 2.

The Law/

Lehi.

The use ratio of the Law/

Summary.

Among those authors who stress the predominantly theological sense of the Law/

|

THEOLOGICAL |

|

|

Abinadi (10.39) |

|

|

Commanded |

God commands repentance |

|

Commandments |

No other God—relational |

|

Law |

Law of Moses points to Christ |

|

Jacob (3.05) |

|

|

Commandments |

No favorite meaning |

|

Law |

Law of Moses points to Christ |

|

Moroni 2 (1.46) |

|

|

Commanded |

Lord or his father commands |

|

Lehi (2.70) |

|

|

Command |

Messenger formula—Lord commands |

|

Laws |

Law of Moses |

Predominantly Editorial in Nature

This section is reserved for Mormon, who, although he might have been placed with those whose word use was primarily secular, must be analyzed separately to see the uniqueness that he brings to his work. As is generally accepted, Mormon’s words begin with the Words of Mormon, are interspersed as he edits the books of Mosiah through 4 Nephi, appear in Mormon 1–7, and are present once again in Moroni 7–9. Given the immense amount of material which Mormon edits and the numerous and separate places where his personal words and thoughts appear, it is important to note that he maintains, across the spectrum of his writings, several unique meanings for words within the Law/

Words from this word group appear 245 times with a moderate use ratio of 2.50. The word group clearly has importance to Mormon. However, because of the size of Mormon’s writings (97,912 words), no single word in the group reaches a use ratio of 1.00, even when it appears seventy-eight times as does Commanded (0.80) or fifty-three times as does Commandments (0.54). Even so, the Law/

Command is one such word. In Alma 2, for example, the word appears nine times as a verb[10] and twice as a noun meaning “an order” (Alma 5:62; 12:9). In Jesus’ words it occurs twice as a verb (3 Nephi 15:16; 16:4), and in the Lord’s words four times as a verb (2 Nephi 3:8; 29:11; Jacob 2:30; Helaman 10:11) and twice in the phrase “at my command” (Ether 4:9). Mormon’s use is very different. Command appears seventeen times as a noun[11] and three times as a verb (Alma 52:4; 3 Nephi 3:17; Mormon 7:4). The dominant meaning as a noun is that of military or social “leadership,” a definition no other writer gives to the word.

Commanded also displays unique characteristics when used by Mormon, being dominated by kings, prophets, or military leaders who command. Thus, Benjamin, Limhi, Ammon, Noah, Alma 1, Amulon, Alma 2, and Gidgiddoni all command their followers to do a variety of secular things.[12] In almost all instances the meaning is essentially nontheological. When Mormon is not editing material, however, it is the Lord who commands (Mormon 3:16; 6:6; 7:10; Moroni 8:21).

The secular motif within the word group continues with the words Law and Laws. In virtually every instance Law means secular law[13] or, more specifically, the Law of Mosiah (e.g., Mosiah 29:39; Alma 1:17; 11:1). Only in Mormon’s sermonic material does the secular motif vanish with the meaning being either the Law of Moses or, perhaps, shorthand for the plan of salvation (Moroni 7:28; 8:22, 24). Laws is also secular in meaning, i.e., Mosiah’s law (e.g., Alma 1:1; Helaman4:21) or tribal law (3 Nephi 7:11, 14).

Mormon is not, however, without interest in things theological. This is manifest in his use of the word Commandments, signifying things which come from God and which seem to convey the idea of “the Christian life.” The term is extremely broad in scope, and no single definition such as Abinadi’s Ten Commandments, Mosiah’s judicial commandments, or Alma the Younger’s ethical commandments is sufficient. Thus, “Christian Life” seems to be the best equivalent for Mormon’s use.[14] Even in his sermonic material, this broad meaning still seems to be operative (Moroni 8:11, 25).

Finally, when Mormon refers specifically to the Law of Moses, it bears theological meaning only in relation to Christ, for it is a type, it points to Christ (e.g., Alma 25:15–16), and it passes away at his coming (3 Nephi 1:24; 15:2).

In summary, Mormon used the terms of the Law/

|

Mormon (2.50) |

Editorial |

Sermonic |

|

Command |

Noun: “Leadership” |

|

|

Commanded |

Royal secular commands |

The Lord commands |

|

Law |

Secular (Mosiah’s) |

Law of Moses |

|

Laws |

Mosiah’s or tribal |

|

|

Commandments |

Christian Life |

|

|

Law of Moses |

Type of Christ |

Jesus’ Theological Key

In this book, “Lord” refers to the Lord who speaks from the heavens. In actuality, this is Jesus, either before his mortal birth or as the resurrected Lord when he speaks from the heavens. Until now neither the words of the resurrected Jesus nor those of the Lord speaking from the heavens have been considered. Yet for each, the Law/

The Lord.

The Lord’s use of the Law/

The Resurrected Jesus.

As we turn to the resurrected Jesus and his use of the Law/

As we study the words Jesus uses, the first thing to note is his consciousness that even he does nothing that the Father does not direct him to do. For example, because his Father has so directed, he does not tell his disciples in the Old World about the Nephites (3 Nephi 15:13–15), yet he goes to other scattered peoples at his Father’s command (3 Nephi 16:3). Further, he completes the work which his Father has commanded him to do, i.e., the gathering of Israel (3 Nephi 20:10).

The heart of the issue, however, is to be found in 3 Nephi 12:17–20. Here Jesus makes clear both his and his Father’s will for members of the Church. Jesus tells us what his command is for those persons who seek to do God’s will:

Think not that I am come to destroy the law or the prophets. I am not come to destroy but to fulfil; For verily I say unto you, one jot nor one tittle hath not passed away from the law, but in me it hath all been fulfilled. And behold. / have given you the law and the commandments of my Father, that ye shall believe in me, and that ye shall repent of your sins, and come unto me with a broken heart and a contrite spirit. Behold, ye have the commandments before you, and the law is fulfilled. Therefore come unto me and be ye saved; for verily I say unto you, that except ye shall keep my commandments, which I have commanded you at this time, ye shall in no case enter into the kingdom of heaven (emphasis added).

These verses appear in the midst of Jesus’ sermon at the temple in Bountiful and give focus to all else that is said in the sermon. What Jesus is instructing the people to do is entirely possible, unless they seek to separate their lives from a relationship with him. Perfection of life—our lives—is to be found in Christ, for he fulfills perfectly the essence of the law (3 Nephi 12:18–19, 46; 15:4–5,8–10).

The emphasized text above states the relationship between the laws and commandments of God and Jesus as our Savior. The text may be interpreted in at least two ways, neither of which necessarily precludes the other. It could mean that Jesus has given in the past, through the Law of Moses and other commands, the directions of his Father, all of which should lead persons to believe in him as the Christ, repent of their sins, and come to him with a broken heart and a contrite spirit.

It could also mean that Jesus was at that moment conveying the Father’s fundamental commands to his children, which are that they shall believe in Christ, repent of their sins, and come to Christ with a broken heart and a contrite spirit. This would mean that obedience to all other commands, particularly those contained in the sermon at the temple, grows out of a person’s relationship with Christ, as well as pointing him or her toward that relationship. This interpretation is supported by Jesus’ next statement: “Except ye shall keep my commandments, which I have commanded you at this time, ye shall in no case enter into the kingdom of heaven” (emphasis added). This seems to suggest that it is not past commandments with which the Lord is concerned, but rather the fundamental commandment to come to him which he wants us to hear. From that relationship comes a “mighty change of heart” which then enables those who have become true Saints to keep the other articulated commands of God—to live the life which the children of God should live—meaning that they possess the mind of God or are Godlike.

Jesus’ use of the other words in the Law/

The centrality of coming to Christ is never left in doubt throughout Book of Mormon history. The Lord, speaking from the heavens, constantly directed the people to turn to him.[17] Nephi also called his people to come to the God of Abraham (1 Nephi 6:4), to God (1 Nephi 10:18; 2 Nephi 26:33), to the Redeemer, and to the fold of God (1 Nephi 15:14–15). Similarly, Jacob summons all to come to the Lord (2 Nephi 9:41), to God (2 Nephi 9:45), to the Holy One of Israel (2 Nephi 9:51), and to Christ (Jacob 1:7). Finally, Moroni 2 bears his witness of the need to come to the Lord (Mormon 9:27), to the Father in the name of Jesus (Ether 5:5), to the fountain of righteousness (Ether 8:26), and to Christ (Moroni 10:30,32). In addition, as seen in the earlier sections of this chapter, Alma 2, Amulek, Nephi 1, Abinadi, Jacob, and Mormon all use certain of their words from the Law/

Conclusions

As a result of the above discussions, two areas need to be highlighted: (1) the divergent ways in which the above authors use the words within the Law/

Author Individuality.

Precisely the kind of diversity that one would expect to find between authors, separated sometimes by centuries in time, has been observed as we considered the ways in which the various authors used the Law/

Theological Implications.

As suggested at the beginning of this chapter, we as Latter-day Saints tend to place a strong emphasis on obedience to the commands of the Lord. Generally, we have in mind ethical commands or commands which direct us to fulfill certain ordinances. In doing so, however, there is a danger that the real commandment—to come unto the Lord—may become lost in the shuffle, causing us to misunderstand the essence of our faith and substitute slavish pharisaism where there should be Christian freedom. Below are some suggestions concerning how this may have occurred and how we may once again realize the incredible freedom that exists in Latter-day Saint theology.

Much of our attention with our young people is turned toward trying to keep them safe in a terribly wicked world. We realize that teenagers do not yet have enough experience with life to see the long-range consequences of their actions. Thus adults, in their wisdom, stress to the younger generation the ethical commands of the Lord in order to keep that generation safe until they have developed the spiritual equipment to keep themselves out of trouble. No active Latter-day Saint would or could deny the validity of this approach. We lay down the law that the young may enter adulthood clean and unsullied by the world, and our study of the Book of Mormon authors certainly validates this approach.

The question to be answered, in light of the above study, is whether we as adults have ever ceased to be spiritual teenagers. Have we gone on to the deeper meanings of the faith? In the end, the “thou shalts” and the “thou shalt nots” are only interim ethics until we have achieved spiritual adulthood in the gospel—an adulthood which means being of one mind with Christ and the Father. A key passage concerning what the Lord understands our goal to be in relation to his law is found in Jeremiah 31:31—34:

Behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel, and with the house of Judah: Not according to the covenant that I made with their fathers in the day that I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt; which my covenant they brake, although I was an husband unto them, saith the Lord: But this shall be the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel; After those days, saith the Lord, I will put my law in their inward parts, and write it in their hearts; and will be their God, and they shall be my people. And they shall teach no more every man his neighbour, and every man his brother, saying, Know the Lord: for they shall all know me, from the least of them unto the greatest of them, saith the Lord: for I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more.

For all of us the day must come when we know God’s will naturally, not because we have a list of things to do or not to do, but because the will of God is ingrained in our very being. In doing so we become one with the Father in the same way the Son is one with the Father, no longer needing to have external rules and laws, because our knowledge of divine things is instinctive. Granted, until such time as we become perfected through the work of the Holy Ghost, we need the laws of God as a tutor and a guide. But the day will come when we no longer need the law, for we will be perfectly one with the Father through the work of Jesus Christ.

Thus, each day that we walk with Christ toward the full realization of our existence in the presence of the Father, we should be less and less dependent on external norms and mandates and more and more dependent upon Christ in whom we will finally live and move and have our full being. The relationship with the Father through Jesus Christ should grow day by day, so that even our thoughts and desires are perfected, and all commands but the one command, “Come unto me,” will fade away and will be no longer needed.[18]

Notes

[1] If there are not at least five occurrences of words from the word group in an author’s text sample, no conclusions are drawn. Similarly, if the use per thousand words of text for the entire word group does not exceed 1.00, that author will be viewed as making a limited contribution to this study, except to say that for him, the material under consideration is of limited importance.

The use-per-thousand figure is determined by taking the number of words in an author’s text (e.g., twenty thousand), dividing it by one thousand to determine the number of “thousands” of words in the text (e.g., twenty), and then dividing the number of occurrences by the number of “thousands” (e.g., forty occurrences divided by twenty thousands, giving a use ratio per thousand of 2.00). If the number of occurrences had been ten, then the ratio would have been 0.50 (ten occurrences divided by twenty thousands). A use ratio of less than 1.00 will not generally be considered of major significance in an author. However, if an author has a long text, such as Mormon, a use ratio of less than 1.00 need not be a barrier in considering the way he uses the words under consideration.

Given these criteria, the following authors will not be considered in chapter 2 because the available sample is too small: Ammon, Nephi 1’s angel, Enos, the Father, Helaman, Isaiah, the Lord in Isaiah, Captain Moroni, Nephi 2, Samuel, Zeniff, and Zenos.

[2] See the section entitled “Jesus’ Theological Key” later in this chapter.

[3] Eleven times with a 0.55 use ratio.

[4] Twelve times with a 0.60 use ratio.

[5] Alma 7:15–16, 23; 9:8, 13; 12:30–32, 37; 13:1, 6; 36:1, 13, 30; 37:13–16, 20, 35; 38:1–2, 39.

[6] 3.79 use ratio.

[7] 1.66 use ratio.

[8] E.g., 1 Nephi 3:7, 15; 4:11; 16:8; 2 Nephi 5:19, 31.

[9] E.g., Ether 2:5; 4:1; 9:20; 12:22, etc.

[10] Alma 5:61; 12:14; 37:1–2, 16, 20, 27; 39:10, 12.

[11] Mosiah 27:3; Alma43:16–17; 47:3, 5,13; 52:15; 53:2; 59:7; 62:3,43; Helaman 12:8; 3 Nephi 4:23, 26; Mormon 5:1, 23; Moroni 7:30.

[12] E.g., Mosiah 1:17; 7:8; 17:1; 18:21; Helaman 4:22; 3 Nephi 4:13, etc.

[13] E.g., Alma 1:32; 10:14; 30:9; Helaman 2:10; 3 Nephi 5:5; 6:30.

[14] See Mosiah 6:1; 17:20; Alma 1:25; 31:9; 48:25; Helaman 3:20, 37; 3 Nephi 5:22.

[15] See also 1 Nephi 2:22; 4:14; 15:11; 17:13; 2 Nephi 1:20; 4:4; Enos 1:10; Jarom 1:9; Mosiah 13:14; Alma 9:13; 50:20; Helaman 10:5.

[16] See also 2 Nephi 4:4; Jacob 2:29; Enos 1:10; Omni 1:6; Alma 9:13; 50:20.

[17] 2 Nephi 26:25; 28:32; Alma 5:34; 3 Nephi 9:14, 22; Ether 3:22; 4:13–14, 18; 12:27; Moroni 7:34.

[18] This is not meant to diminish the necessity of the ordinances of the Church. There is not a single ordinance with a purpose other than to bring us to Christ.