Of Soils and Souls: The Parable of the Sower

Jared M. Halverson

Jared M. Halverson, "Of Soils and Souls: The Parable of the Sower" Religious Educator 9, no. 3 (2008): 31–48.

Jared M. Halverson (HalversonJM@ldsces.org) was a CES coordinator in Nashville, Tennessee when this was written.

The parable of the sower ranks first among the parables in many respects. Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

The parable of the sower ranks first among the parables in many respects. Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

There are certain stories which are not so much the heritage of the scholar and the material of the theologian as the possession of every man; and such are the parables of Jesus. Even in an age when men know less and less of the Bible, and care less for it, it remains true that the stories Jesus told are the best known stories in the world.[1]

Among the parables of Jesus, the parable of the sower ranks first in some respects. Chronologically, wrote Elder James E. Talmage, the sower comes “first in the order of delivery” and deserves “first place among productions of its class.”[2] The primacy of this parable, however, goes beyond chronology and composition. Significance also comes from the story’s repetition and explanation. It is one of three parables repeated in all three synoptic Gospels. Similarly, it is one of the few parables for which the Lord Himself included a detailed interpretation, which all three synoptists made sure to include.[3] As Jesus later explained to His disciples, “Unto you it is given to know the mysteries of the kingdom of God” (Luke 8:10). Evidently the Master considered this particular parable a mystery the disciples could ill afford to misunderstand (see Matthew 13:51).

Moreover, the Prophet Joseph Smith interpreted the parable of the sower at length, connecting it to the other parables of the kingdom in Matthew 13 and placing them all in specific historical context. Like the Savior before him, the Prophet saw in the sower a topic of immense importance for his hearers, one they could not fail to comprehend would they “but open [their] eyes, and read with candor, for a moment.”[4]

Today’s disciples should be no less concerned with understanding this parable—to find, in Elder Talmage’s words, “the living kernel of gospel truth within the husk of the simple tale.”[5] Yet, paradoxically, students of the scriptures seem to spend less time deciphering this “parable of parables” than many of its counterparts. Why? Perhaps because in the case of the sower, the teacher already seems to have done the students’ work.

Almost without exception, a parable is narration without explanation, “arresting the hearer by its vividness or strangeness, and leaving the mind in sufficient doubt about its precise application to tease it into active thought.”[6] Perhaps because the Gospels include a rather “precise application” from the author Himself, the parable of the sower does not tease as much active thought as it should. Yet should not the opposite be true? The fact that the Savior specifically interpreted this parable (and Joseph Smith did too) should lead students of the scriptures to pay more attention to the sower, not less.

In that light, this essay invites readers to examine (1) the parable’s content and (2) the Savior’s objective in telling it. With such an understanding, today’s disciples—especially those teachers and leaders who go “forth to sow” (Matthew 13:3)—may then achieve a third objective: a wider perception of the parable’s intended application, one that will affect their ministry in the same way the Savior originally intended it to affect that of His disciples.

This insight can come only by looking through the lens of Joseph Smith’s inspired explanation of the parables of the kingdom. His comprehension facilitates our own. By connecting the sower to the parables that immediately follow, the Prophet allows today’s reader to go beyond simple classification (seeing the parable solely as a description of separate types of individuals) and to approach the parable historically (as a depiction of the preaching of the gospel in the apostolic age) and linearly (as one soul’s progression through varying degrees of discipleship).

The Sower and the Parables of the Kingdom

For the Prophet Joseph Smith, parables were often firmly rooted in history. He saw in them large-scale historical developments, not simply timeless truths or ethical abstractions. To him, parables were as much about prophecy as they were about principles, and in nothing was this more true than in the parables of the kingdom found in Matthew 13. Specifically, Joseph saw in these parables—beginning with and in large part growing from the sower—”as clear an understanding upon the important subject of the gathering, as anything recorded in the Bible.”[7] The Prophet explained that when the Savior first taught the parable of the sower, it had “an allusion directly, to the commencement, or the setting up of the Kingdom in that age.” The chapter’s remaining parables likewise concerned the kingdom, the destiny of which, Joseph said, could be “trace[d]” in those sayings “from that time forth, even unto the end of the world.”[8]

In stunning sequence, Joseph applied each parable to a specific scene in the progress of the kingdom of God—the sower to the establishment of the kingdom in the time of Christ; the parable of the wheat and tares to the corruption of the Church in the age of apostasy; the mustard seed to the growth of the kingdom in the last days; the leaven to the expanding testimony of truth that was first granted to the Three Witnesses; the treasure hidden in the field to the gathering of the Latter-day Saints in their lands of inheritance; the pearl of great price to the Saints’ search to find places for Zion; and the gospel net to the gathering of people “of every kind” to the kingdom before their separation on the Day of Judgment.[9] Joseph Smith took his audience through the parables the way a historian takes his readers through the past, pointing out parallels with a fixed fulfillment in time.

By explaining—and connecting—these parables in this way, the Prophet showed them to be one cohesive narrative rather than a collection of separate stories. In so doing, he affirmed that the sequence of parables in Matthew 13 was a deliberate teaching tool of the Savior, not merely an organizational technique considered typical of Matthew.[10] Jesus wanted the disciples to see these particular parables not as seven stories but as one story in seven parts, each part relating to the others and proceeding in a definite sequence. As if in summary, Jesus asked His disciples at the conclusion of this discourse, “Have ye understood all these things?” (Matthew 13:51; emphasis added). In answer to this question, Joseph Smith responded for the Saints in his day, “Yea, Lord; for these things are so plain and so glorious, that every Saint in the last days must respond with a hearty Amen to them.”[11]

Joseph’s unified view of the parables of the kingdom finds further evidence in the Master’s words as recorded in Mark 4:13. When the disciples “asked of him the parable” of the sower, the Lord responded: “Know ye not this parable? and how then will ye know all parables?” (Mark 4:10, 13). Some have cited this verse to suggest that the sower was meant as a model to illustrate and elucidate this way of teaching. Typical of this view, one scholar labeled it “a parable about parables” constituting “the key to understanding the rest.”[12]

Thus the Prophet’s panoramic interpretation shows the sower to be much more than a practice parable; its link to the stories that followed was one of substance, not merely of style. Indeed, if the overarching theme of the Lord’s parables “was the kingdom of God and especially its eschatological significance for the chosen people living in his day,”[13] then Joseph’s understanding of the sower (as a direct allusion to the establishment of that kingdom in Christ’s time) affirms its placement as the first of the parables. Clearly, when Jesus based the understanding of “all parables” on the understanding of “this parable” (Mark 4:13), He asserted the foundational character of the sower. His other parables, particularly the parables of the kingdom, were outgrowths of the story of seeds and soils.

This was especially true in the two parables that immediately followed—the parable of the wheat and tares and the parable of the mustard seed. Based on Joseph’s view of a continuing historical narrative, it is not surprising that the Lord employed similar symbols in these three stories. In fact, just as the two later parables grew out of the first, the symbols of the first may have given rise to the symbols of the others. The parable of the wheat and tares thus parallels the seed that fell among thorns, left to grow amid the weeds; and the mustard seed mirrors the seed in good ground, which grows to a miraculous maturity. If, as the Prophet explained, the sower showed “the effects that [were] produced by the preaching of the word” in the time of Christ, then the two subsequent parables followed the fate of such seeds: choked by tares through the age of apostasy, yet eventually nurtured, “securing it by . . . faith to spring up in the last days.”[14] Within the elements of the sower, the Savior provided a summary statement from which He revealed to His disciples the destiny of the kingdom of God.

Thus informed, the disciples understood what the Savior was doing at that exact moment—sowing seeds in the very act of speaking about them. However, Christ was not to be the only sower in the story; they had been called to sow as well. Therefore, an understanding of the what behind the sower was insufficient. The disciples also needed to comprehend the why.

Content in Context

The audience that first heard the parable of the sower consisted of a sampling of “soils” that varied from barren to fertile, with every grade between. Moreover, in the parable itself the number of soil types was four, a number that often symbolizes completeness.[15] The gospel seed was intended for all people, and the Savior’s immediate audience embodied a representative sample. The parable was being fulfilled as it was given, with the audience spreading itself across the spectrum with each word the Savior spoke. Because the disciples were to participate in this planting, they would likewise need to know about the soils in which they sowed.

This was especially true considering the prevalence of less-than-fertile ground, or, as one writer noted, “the amount of attention that is given to the variety of ways in which the seed may come to nothing.”[16] Mark placed the sower “immediately after a direct challenge by the Jerusalem religious authorities concerning the nature of Jesus’ authority,” making it a symbol of “Israel’s response to and rejection of Jesus.”[17] Edersheim argued that such underlying opposition was “common to all the Parables. . . . They are all occasioned by some unreceptiveness on the part of the hearers.”[18] As Matthew recounted, the accusations of the Pharisees (see Matthew 12:2, 10, 14, 24), the sign seeking of the scribes (see Matthew 12:38–39), and the pronouncement of these parables all occurred on “the same day” (Matthew 13:1).

Aware of the mounting opposition, Jesus told His disciples that He taught in parables “because they seeing see not; and hearing they hear not, neither do they understand” (Matthew 13:13). Citing the same verse, Joseph Smith explained that the Lord taught people parables “because their hearts were full of iniquity”—the same phrase the Prophet used immediately thereafter to define those who received seed “by the way side.”[19] Jesus spoke of the wayside when speaking to the wayside, whereas He gave the good news plainly to those on good ground.

This meting of the message based on the receptivity of the audience is evident in Jesus’s clear differentiation between the multitudes who would not understand and the disciples who at first could not understand but who desired to. To the latter group, “it is given . . . to know the mysteries of the kingdom of heaven.” To the former, “it is not given” (Matthew 13:11).[20] Jesus may have “withdraw[n] verbally into the veiled speech of parables, just as he [withdrew] physically” from the multitudes, but in both cases He brought His disciples with Him—physically “into the house” apart from the masses (Matthew 13:36) and symbolically into an understanding of the parables He had taught.[21]

Obviously, whereas the sower was meant for the many, its interpretation was intended for the few. According to Joseph Smith’s inspired translation, Christ did not explain the parable until “he was alone with the twelve, and they that believed in him” (Joseph Smith Translation, Mark 4:10; emphasis added). Therefore, the Lord had a separate purpose in explaining the seeds and soils to them. As discussed, Christ was revealing to His fellow sowers a prophetic view of the kingdom they were working to establish. Even before He taught these parables, Christ had called upon His disciples to preach that kingdom (see Matthew 10:7), and after He explained His stories, He would send them forth to do more of the same (see Luke 9:2; 10:9). They needed to know that in spite of seeds that never sprouted or weeds that choked the word, the kingdom of God would eventually find good soil and bring forth “an hundredfold” (Matthew 13:8, 23).

The disciples, once they truly “understood all these things” (Matthew 13:51) as Jesus hoped, would recognize their roles during the critical opening scenes of the kingdom of God during the meridian of times. Taking these parables as a whole, they would anticipate their efforts’ mixed results in the short term (the sower), expect a corruption of their work in the long term (the wheat and tares), and be assured of eventual triumph in the end (the mustard seed). They would know of the kingdom’s powerful potential (the leaven), its priceless value (the treasure in the field and the pearl of great price), and its two-edged effect (the gospel net). Furthermore, they would know that not all seeds would bear fruit but that they were still to be sowed.

From the parable of the sower, they would receive great reassurance and hope: rejection was inevitable, but so was an eventual harvest. There would be waysides, stones, and thorns to confront, but there would be good ground and plentiful yields as well. They would face Pharisees, unwilling to plant the word themselves and intent on trampling down whatever seed might possibly be planted in others (see Matthew 23:13). They would find curious sign seekers, eagerly following one who might miraculously provide bread but “[going] back” at the first “hard saying” (see John 6:60–66). They would meet the otherwise obedient who would not loosen their grip on lesser things (see Matthew 19:16–22). Nevertheless, they would also find themselves among the faithful who would “go and bring forth fruit, and [whose] fruit should remain” (John 15:16).

To Plow in Hope

How were the disciples to respond to the grades of soils described in the parable? Obviously classification was intended, for it was inherent in the Savior’s interpretation. Yet how firm were those dividing lines, and how fixed were they meant to remain? Were they to pass final judgment or determine present conditions? Were they to classify individual hearers of the word or initial reactions to the word? Depending on their response to these questions, the disciples may have limited their classification of hearers to a mere four categories, when real reactions were more numerous and nuanced. Worse, they may have pigeonholed people who might otherwise have been amenable to change. If the Savior taught and interpreted the parable to give hope to those who would be preaching His word, He must have intended it as a continuum upon which hearers were in constant motion, not merely as a dresser with four unchangeable drawers.

Elder James E. Talmage made these same two allowances in his analysis of the parable. First, he referred to the soil not as different types but as varying “grades” described “in the increasing order of their fertility.” Even the good ground was of “varying degrees of productiveness, yielding an increase of thirty, sixty, or even a hundred fold, with many inter-gradations.”[22] Thus the sower was not meant to compartmentalize listeners but rather to depict “the varied grades of spiritual receptivity existing among men.”[23]

Second, Elder Talmage refused to see in this parable what other scholars had tried to advance: “evidence of decisive fatalism in the lives of individuals.” He did not accept the interpretation—rooted in Calvinism—that individuals were either “hopelessly and irredeemably bad” or “safe against deterioration and . . . inevitably productive of good fruit.” In his opinion, the Savior “neither said nor intimated that the hard-baked soil of the wayside might not be plowed, harrowed, fertilized, and so be rendered productive; nor that the stony impediment to growth might not be broken up and removed, or an increase of good soil be made by actual addition; nor that the thorns could never be uprooted, and their former habitat be rendered fit to support good plants.”[24] After all, Jesus had come—to paraphrase His words to the Pharisees—”not . . . to call [the good ground], but [the wayside] to repentance” (Matthew 9:13). He had sent forth His disciples to till the earth, break up stones, weed out thorns, and help others “bring forth . . . fruits meet for repentance” (Matthew 3:8). He taught that souls, like soils, could change.

After all, in explaining the sower to His disciples, how could the Savior promise that by listening and understanding, the unbelieving “should be converted, and I should heal them” (Matthew 13:15) if such conversion was impossible in the first place? Moreover, how could He give “more abundance” to “whosoever receiveth” and take away from those who “continueth not to receive” (Joseph Smith Translation, Matthew 13:10–11) if movement across the spectrum was never possible?

Under such confining categorization, how could the disciples “plow in hope” (1 Corinthians 9:10) if wayside soil could never be plowed in the first place? How could God give “an heart of flesh” if the “stony heart” (Ezekiel 11:19) could not be taken out at all? How could the fir tree take the place of the thorn (see Isaiah 55:13) if thorns were a permanent condition? Christ’s fellow sowers needed to know this foundational truth in order to continue their labors on less than fertile soil. Otherwise, they would have simply turned their attention to the good ground, leaving the fowls, stones, and thorns to do as they may.

But such was not the way of the Lord of the Vineyard. Jesus refused to give up on the seemingly barren soil that surrounded Him, as shown in the parable of the barren fig tree: after waiting for fruit in vain for three years (an allusion to the Savior’s mortal ministry), when even the owner of the vineyard was ready to give up on the unproductive plant, his servant pleaded, “Lord, let it alone this year also, till I shall dig about it, and dung it: and if it bear fruit, well: and if not, then after that thou shalt cut it down” (see Luke 13:6–9). In an even more dramatic example, the allegory of the olive tree portrayed a Master who was willing to prune and pluck, dig and dung, nourish and graft—and involve His servants in the same untiring efforts (see Jacob 5:41, 47). Eventually the harvest and judgment would come, but until then, there was hope for every soil. Jesus had not come merely in search of good ground but in hopes of calling “sinners to repentance” (Luke 5:32).

Soils across the Spectrum

In interpreting the parable of the sower, the Master was preparing His disciples for the wide range of soils they would encounter in their preaching, not that they might make final decrees but preliminary diagnoses. By identifying a soil’s existing state, the disciples would be able to decide how best to treat it for more successful sowing in the future. In this regard, the Savior’s explanation of the soils was of immense value—an explanation He gave only to those who would be sowing and nurturing the seed. Theirs would be the work of plowing hardened earth, removing stones, or uprooting thorns, depending on the soil before them.

However, what of the sowers of today? What of those who live in the days of the ever-expanding mustard seed and the quickly filling gospel net? As timely as the sower was in fitting the historical context of Jesus’s day, it is also timeless in teaching the spiritual truths needed to successfully sow the seed in our own day. Thus today’s sowers should feel twofold appreciation for the parable of the sower. First, we can rejoice in seeing the fulfillment of yesterday’s ultimate hopes (as if in echo of Matthew 13:17). Second, in our own sowing we can identify existing soil types and tailor our teaching to the soils that sit before us, with proximate hope that each plant can come bear fruit. To this end, the soils themselves—and the Savior’s descriptions of them—deserve particular attention.

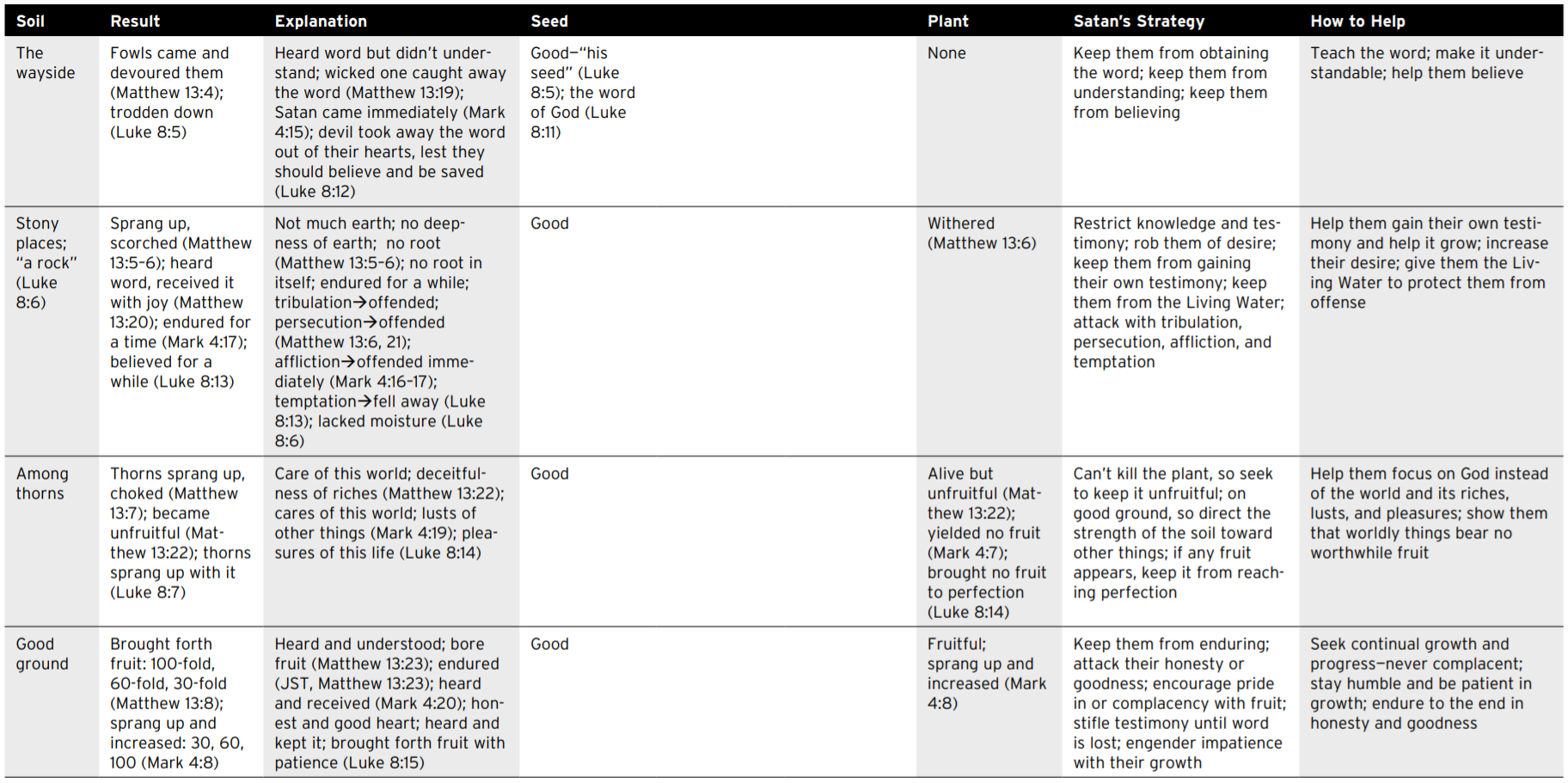

The wayside. The most striking characteristic of wayside soil is its total absence of plant life. Yet the real problem is not the lack of vegetation but the absence of fruit. John the Baptist called for “fruits meet for repentance” and warned that “every tree which bringeth not forth good fruit is hewn down, and cast into the fire” (Matthew 3:8, 10). Christ Himself echoed this warning (see Matthew 7:19; John 15:2) and left a striking reminder when He cursed the fig tree for having “leaves only” (Matthew 21:19). Similar emphasis on “bringing forth fruit” appears in the parable of the wicked husbandmen (see Matthew 21:33–43) and is the core of the parable of the barren fig tree (see Luke 13:6–9). Clearly the word of God, as symbolized by the seed, is of no real worth unless fruit is forthcoming.

If fruitfulness is the chief goal of the Master, fruitlessness must ever be the adversary’s aim. And there can be no fruit where there is no plant. This is precisely the condition of the wayside. In the parable, the moment the seeds left the hand of the sower, “the fowls of the air came and devoured them up” (Mark 4:4; see also Matthew 13:4), “lest a grain of it perchance find a crack in the trampled ground, send down its rootlet, and possibly develop.”[25] Any seeds that escaped the birds’ eager advances were “trodden down” (Luke 8:5) lest they sprout. Such soil is reflected in Jeremiah’s lament over Israel: “The birds round about are against her; come ye, assemble all the beasts of the field, come to devour. Many pastors have destroyed my vineyard, they have trodden my portion under foot, they have made my pleasant portion a desolate wilderness” (Jeremiah 12:9–10).

Such is the state of the soul who “heareth the word of the kingdom, and understandeth it not” (Matthew 13:19), the Savior explained. Satan comes—”immediately,” inserts Mark—to take away “the word that was sown in their hearts” (Mark 4:15), “lest they should believe and be saved” (Luke 8:12). The combined details provided by the three synoptists outline the process of spiritual growth the word is meant to accomplish: hear, understand, believe, and be saved. With reason, therefore, the adversary seeks to disrupt this process, and the earlier the better. Consequently, the adversary’s initial opposition usually consists in restricting the word. Insofar as he is able, he keeps people from hearing; if they hear, he tries to keep them from understanding; if they understand, he attempts to keep them from believing. Christ described the process using Isaiah’s words: the people would not “hear with their ears” and therefore would not “understand with their heart” and therefore would not “be converted” (believe) that He should “heal them [be saved]” (Matthew 13:15).

The Savior, meanwhile, invites all people in the opposite direction—away from the wayside—sending His servants forth to make the word accessible and understandable and helping His listeners believe what they are taught. Appropriately, in explaining good ground, the Master listed these two essential conditions first: hearing and understanding the word (see Matthew 13:23).

Stony ground. If a seed perchance escapes the pecking of birds and the trampling of feet, it at least has some chance to germinate, but Satan is not easily deterred. Seeds may sprout and plants may grow, but things that live can also be made to die. This best occurs “on stony ground” (Mark 4:5).

Unlike the seeds that are “immediately” taken away from the wayside (Mark 4:15), those that fall on stony ground “immediately” spring up to life (Mark 4:5) only to wither away just as quickly (see Luke 8:6). They have “no deepness of earth” (Matthew 13:5), only a thin layer of soil covering the rock just beneath it, a geological condition common in Israel. Without room to grow downward, the upward growth is momentary at best, leaving these plants, which have “no root,” to wither away once the sun comes up to scorch them (see Matthew 13:6; Mark 4:6).

Less concerned with the depth of the soil, Luke recorded that the reason the plant withers is not primarily because it lacks earth but “because it lack[s] moisture” (Luke 8:6). Yet this lack of moisture is not due to lack of rain, which God promises will always come “in due season, [for] the land [to] yield her increase, and the trees of the field [to] yield their fruit” (Leviticus 26:4). The lack of moisture results when such rain is wasted as runoff, unable to penetrate the rock beneath the scant layer of soil. Unable to send forth roots that might reach a more permanent (but deeper) source of water, these plants depend on what little they might first catch from the clouds.

Unlike those by the wayside who refuse to hear, understand, and believe, those with stony ground “heareth the word” (Matthew 13:20), “receive it with gladness” (Mark 4:16), and “believe” (Luke 8:13). Unfortunately, this step—a step up from the wayside—is short-lived. They believe, but only “for a while” (Luke 8:13); they endure, but only “for a time” (Mark 4:17).

The reasons that they wither are fourfold: “tribulation” (Matthew 13:21), “affliction” (Mark 4:17), “persecution” (Matthew 13:21; Mark 4:17), and “temptation” (Luke 8:13), each represented by the scorching heat of the sun. Ironically, the heat that causes them to wither could also cause them to grow, for seeds require sunlight. When these opposing forces arise “because of the word” (Matthew 13:21), and “for the word’s sake” (Mark 4:17), the two-edged effects of the sun depend completely, as Luke records, on the amount of moisture. If individuals “have no root” (Luke 8:13) or, more specifically, “no root in themselves” (Mark 4:17; emphasis added; see also Matthew 13:21), they become “offended”—whether “immediately” (Mark 4:17) or “by and by” (Matthew 13:21)—and eventually “fall away” (Luke 8:13).

Knowing of people’s need for continual spiritual sustenance, Satan tries to restrict its availability, confident that even the good word of God will not last long without the living water. Tribulation and affliction are inevitable in life, temptation is common, and persecution is certainly not rare, but their effect upon us will be harmful only if we fail to “draw water out of the wells of salvation” (Isaiah 12:3). At such times, surface spirituality no longer suffices, and disciples whose faith is not deeply rooted are unable to draw upon the more profound sources of moisture. Furthermore, if they “have no root in themselves” (Mark 4:17; emphasis added), they will eventually find themselves unable to survive in thin soil on someone else’s water.

Jesus, on the other hand, seeks the opposite course (see Psalm 80:8–9). Knowledge and testimony are given room to grow. The scorching heat of the sun is not necessarily lessened, but to offset it, the true disciple is given “a well of water springing up into everlasting life.” And unlike the plant with no root in itself, this disciple’s well of water is “in him” (John 4:14).

Among thorns. Even when a person’s “soil” is free of the stones that would confine the seed’s growth, the adversary attempts to divert the sunlight and redirect the rain so that the strength of the soil might be leached by lesser plants. Such is the case when a seed falls “among thorns.”

In this instance, the ground produces an abundant yield—but of the wrong crop. Unfortunately, because of the plentiful thorns, the growing plant is “choked” and becomes—though still living—of no worth at the harvest. As Mark records, it yields “no fruit” (Mark 4:7). According to Luke, the thorns spring up with the sprouting seed (see Luke 8:7). Apparently the thorns were not there previously; the seed and the thorns grow together in ground that was ready for planting. Even in Matthew’s and Mark’s accounts, the thorns do not “spring up” until after the seed has been sown. Accordingly, the third type of soil seems no different from the fourth type of soil before its planting. Only after the seeds begin growing do the thorns appear.

Originally, thorns were a product of the Fall (see Genesis 3:18), as are the vices these thorns represent in the parable: “cares and riches and pleasures of this life” (Luke 8:14), “the care[s] of this world, and the deceitfulness of riches” (Matthew 13:22; Mark 4:19), and “the lusts of other things” (Mark 4:19). When the word is preached to the honest in heart (good ground), it begins to germinate within them. And “when they have heard, [they] go forth” (Luke 8:14), intent on bringing forth fruit. Meanwhile, however, Satan ensures that worldly distractions begin “entering in” (Mark 4:19) as well, until they sap the strength of the growing seedling and keep it from bearing fruit—fruit which is likely already in the bud when the thorns begin to appear.

Luke does mention fruit, but the plant he describes, in its depleted condition, could “bring no fruit to perfection” (Luke 8:14). In Matthew’s and Mark’s accounts, the plant “becometh unfruitful” (Matthew 13:22; Mark 4:19; emphasis added), suggesting that earlier at least some fruit had grown. In either instance, the plant remains alive, but, as the Lord lamented in a later parable, only to cumber the ground (see Luke 13:7).

Satan works quickly on this type of soil, alarmed when conditions exist that are conducive to growth. Once-eager listeners pass through his preliminary attempts to sabotage the soil, but as soon as they shift from mere membership to true discipleship, the adversary begins to offer alluring alternatives to divert the person’s time and strength. If he succeeds, individuals of great potential will have “changed their glory for that which doth not profit” (Jeremiah 2:11). Their “strength shall be spent in vain: for [their] land shall not yield her increase, neither shall the trees of the land yield their fruits” (Leviticus 26:20). God will have “sown wheat, but shall reap thorns” (Jeremiah 12:13).

Worst of all, because the plant has not yet withered, a person with such soil may have a false sense of accomplishment, having achieved at least something, and a false sense of security, seeing that the plant is at least marginally alive. Such a person is present but not productive, living but not lively, honorable but not valiant (see D&C 76:75, 79). Like the foolish servant in the parable of the talents, those among thorns thought subsistence would do, when the Master expected increase (see Matthew 25:14–30).

Good ground. The sower’s final soil—and ultimate goal—is described simply as “good ground,” good not merely because it is able to support seeds but because those seeds “sprang up, and bare fruit” (Luke 8:8; emphasis added). In fact, in some cases the harvest is miraculous: the seed in Luke’s version “bare fruit an hundredfold” (Luke 8:8).

“But even here,” wrote Elder Bruce R. McConkie, “crops of equal value are not harvested by all the saints. There are many degrees of receptive belief; there are many gradations of effective cultivation.”[26] This gradation is inherent in the accounts of both Matthew and Mark—in Matthew “some [produce] an hundredfold, some sixtyfold, some thirtyfold” (Matthew 13:8)—but growth is most evident in Mark, in which the fruit “sprang up and increased” (Mark 4:8; emphasis added). Thus, when Mark listed the same quantities as Matthew but in ascending order, perhaps he was underscoring an ever-increasing productivity, not merely a differentiation of yields. As Christ later told His Apostles, “Herein is my Father glorified, that ye bear much fruit” (John 15:8; emphasis added). Wherefore, “every branch in me that beareth not fruit he taketh away: and every branch that beareth fruit, he purgeth it, that it may bring forth more fruit” (John 15:2; emphasis added).

These ever-increasing yields obviously take time. Thus, in Luke’s account, whereas the plant “sprang up” (Luke 8:8) quickly, achieving the hundredfold harvest only comes “with patience” (Luke 8:15; see also James 5:7). Fortunately, in contrast with others on the spectrum, those with good ground are willing to devote that time to nurture the seed as it grows. Unlike the wayside, they “heareth the word, and understandeth it” (Matthew 13:23); unlike the stony ground, they “endureth” (Joseph Smith Translation, Matthew 13:23); and unlike the soil with thorns, they “keep [what they hear], and bring forth fruit” (Luke 8:15). The sowing is successful because of the current nature—or ongoing preparation—of the soil: the scattered seed has fallen “in an honest and good heart” (Luke 8:15).

Pulling toward the Poles

Analyzing the enemy’s tactics through the different soils—from wayside to good ground—is like watching an army in retreat: it fights, then falls back, only to regroup and renew attacks elsewhere. Meanwhile, in hope, the Lord and His fellow sowers draw their hearers in the opposite direction. They know, as the parable of the sower suggests, that the word of God leads to understanding, belief, acceptance, and fruitfulness; to patience, goodness, endurance, and salvation. They also know the final destiny of the kingdom they are laboring to build.

In this tug-of-war, hearers of the word can alone decide their direction, edging toward the wayside or progressing toward good ground. The sowers of the seed, as Jesus and Joseph both taught, can but rest in the ultimate triumph of the kingdom and work for the proximate progress of those they serve. Such is always the case when God’s children come in contact with His word—in Christ’s day, in Joseph Smith’s day, and in our own. The fowls, stones, and thorns are once again poised to take their positions, as each individual decides what type of soil he will be. This is not a single decision, resulting in our permanent placement amid the soils. Rather, it is an ongoing process—with continual motion across the continuum until the wheat is harvested, the mustard seed grown, the meal leavened, the pearl found, and the fishes gathered. Until then, the sower still goes forth to sow, hoping to find in us “faith, and . . . diligence, and patience, and long-suffering, waiting for the tree to bring forth fruit” (Alma 32:43).

Notes

[1] William Barclay, And Jesus Said: A Handbook on the Parables of Jesus (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1970), 9.

[2] James E. Talmage, Jesus the Christ (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 263, 265.

[3] Many modern scholars wrongly assume that the interpretation of the parable was an insertion made later by the Christian community; however, Elder Talmage (and a host of others, including Joseph Smith) credits it to “the divine Author” Himself, which makes the parable, in Elder Talmage’s words, “particularly valuable” (Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 263).

[4] Joseph Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, comp. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 96.

[5] Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 277.

[6] C. H. Dodd, The Parables of the Kingdom, rev. ed. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1961), 5; quoted in James L. Bailey and Lyle D. Vander Broek, Literary Forms in the New Testament (Louisville, KY: Westminster/

[7] Smith, Teachings, 94.

[8] Smith, Teachings, 97; emphasis added.

[9] Smith, Teachings, 94–102.

[10] Giving voice to the accepted contemporary view of the Gospel of Matthew, John P. Meier wrote of the “monumental remodeling of the gospel form in the direction of lengthy discourses” (David Noel Freedman, ed., The Anchor Bible Dictionary [New York: Doubleday, 1992], 4:628, s.v. “Matthew, Gospel of”).

[11] Smith, Teachings, 102.

[12] Morna D. Hooker, “Mark’s Parables of the Kingdom,” in Richard N. Longenecker, ed., The Challenge of Jesus’ Parables (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), 87.

[13] Richard D. Draper, “The Parables of Jesus,” in Studies in Scripture: The Gospels, ed. Kent P. Jackson and Robert L. Millet (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 266.

[14] Smith, Teachings, 97–98.

[15] “The number four symbolizes geographic completeness or totality. In other words, if the number four is associated with an event or thing, the indication is that it will affect the entire earth and all its inhabitants” (Alonzo L. Gaskill, The Lost Language of Symbolism [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003], 119).

[16] Leon Morris, The Gospel according to Matthew (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1992), 335.

[17] Hooker, “Mark’s Parables of the Kingdom,” 89.

[18] Alfred Edersheim, The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah (n.p.: Hendrickson, 1993), 400.

[19] Joseph taught, “This is he which receiveth seed by the way side. Men who have no principle of righteousness in themselves, and whose hearts are full of iniquity, . . . and have no desire for the principles of truth, do not understand the word of truth when they hear it. The devil taketh away the word of truth out of their hearts, because there is no desire for righteousness in them” (Smith, Teachings, 96; emphasis added).

[20] See Matthew 13:10–16. The Prophet made it a point to provide the antecedents of the pronouns in these verses (Smith, Teachings, 94–95).

[21] Meier, “Matthew, Gospel of,” in Freedman, The Anchor Bible Dictionary, 629.

[22] Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 265.

[23] Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 266; emphasis added.

[24] Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 265–66.

[25] Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 264.

[26] Bruce R. McConkie, The Mortal Messiah (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1980), 2:253.