Profiles of the Prophets: Brigham Young

Charles Swift

Charles L. Swift, “ Profiles of the Prophets: Brigham Young,” Religious Educator 8, no. 1 (2007): 103–122.

Charles L. Swift was an assistant professor of ancient scripture at BYU when this was written.

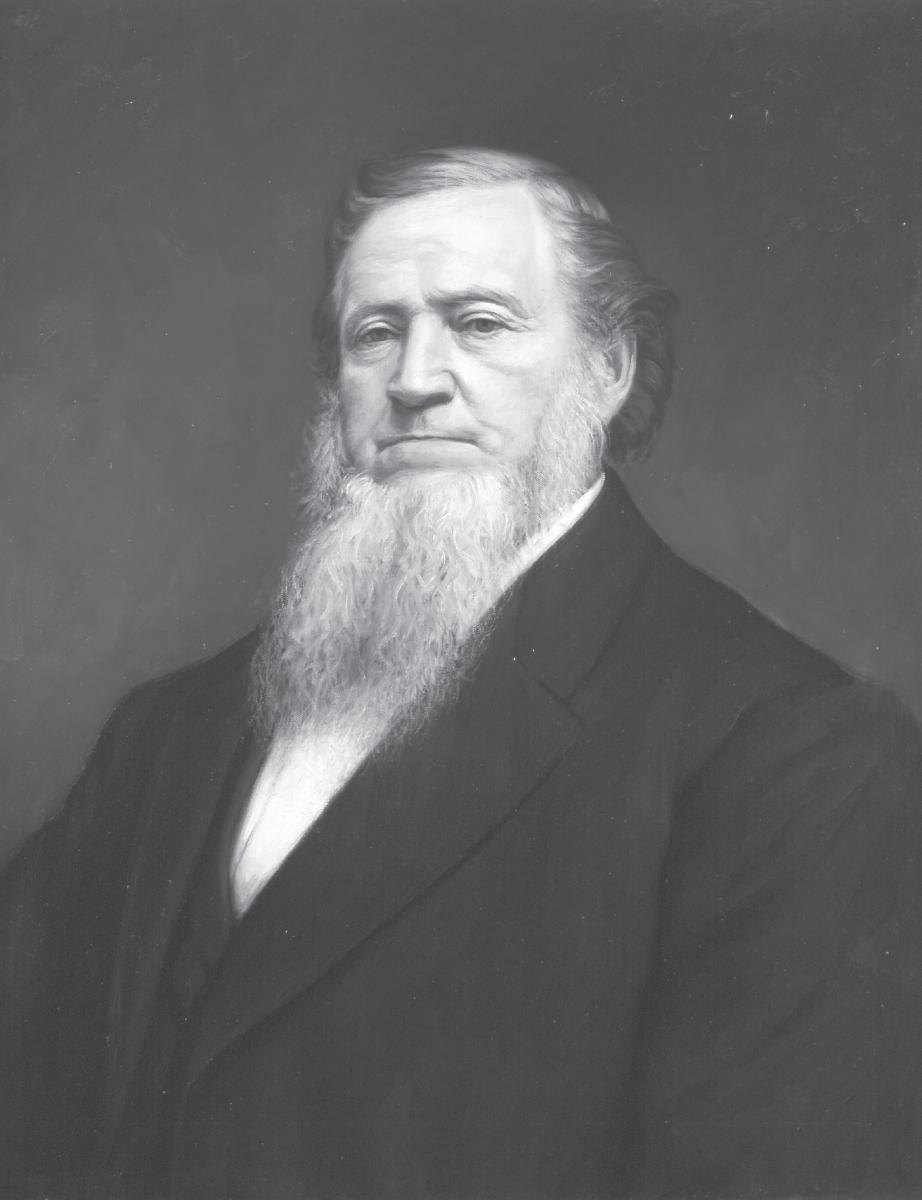

Brigham Young portrait, about 1882 (attributed to John W. Clawson). Courtesy of Museum of Church History and Art.

Brigham Young portrait, about 1882 (attributed to John W. Clawson). Courtesy of Museum of Church History and Art.

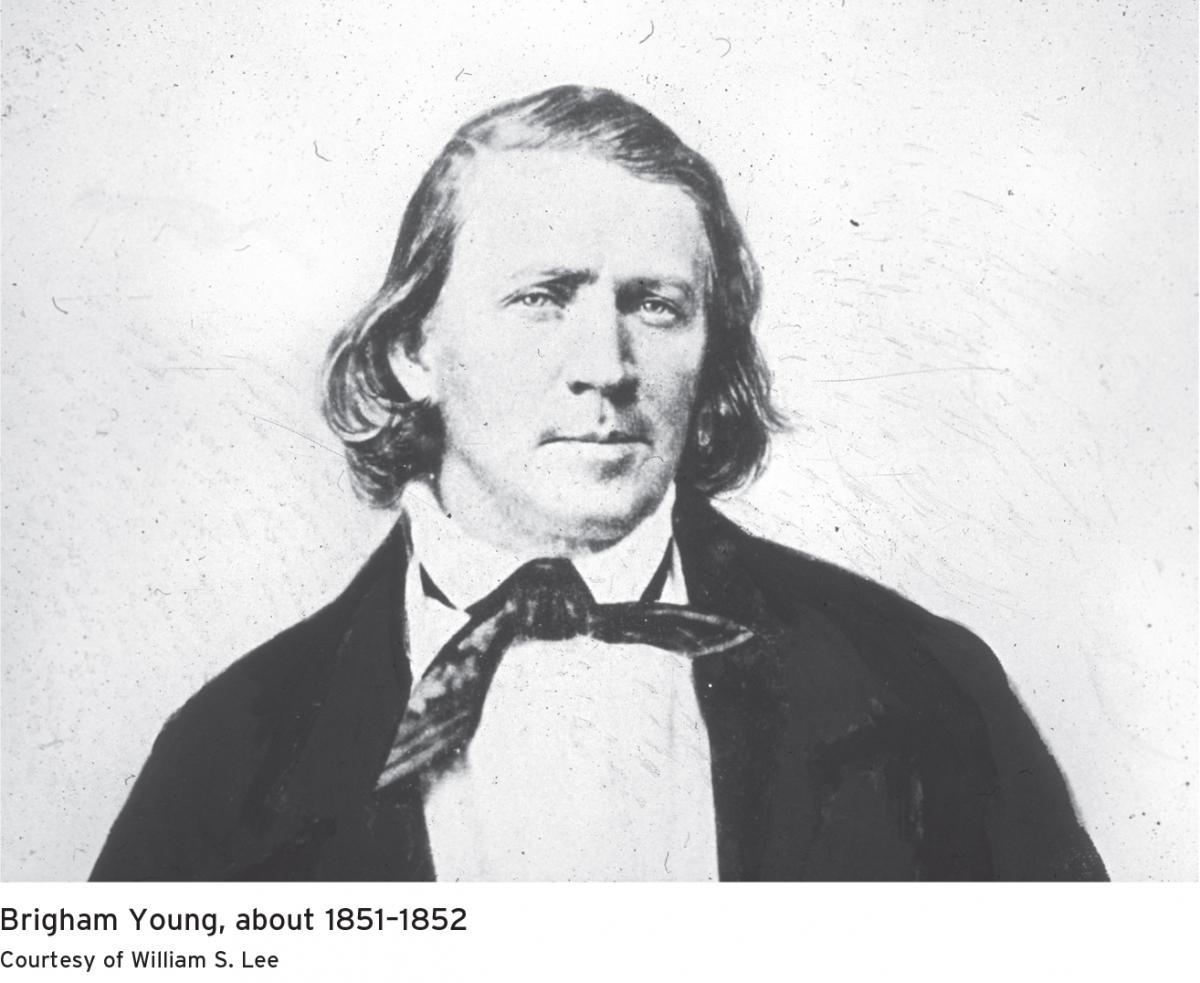

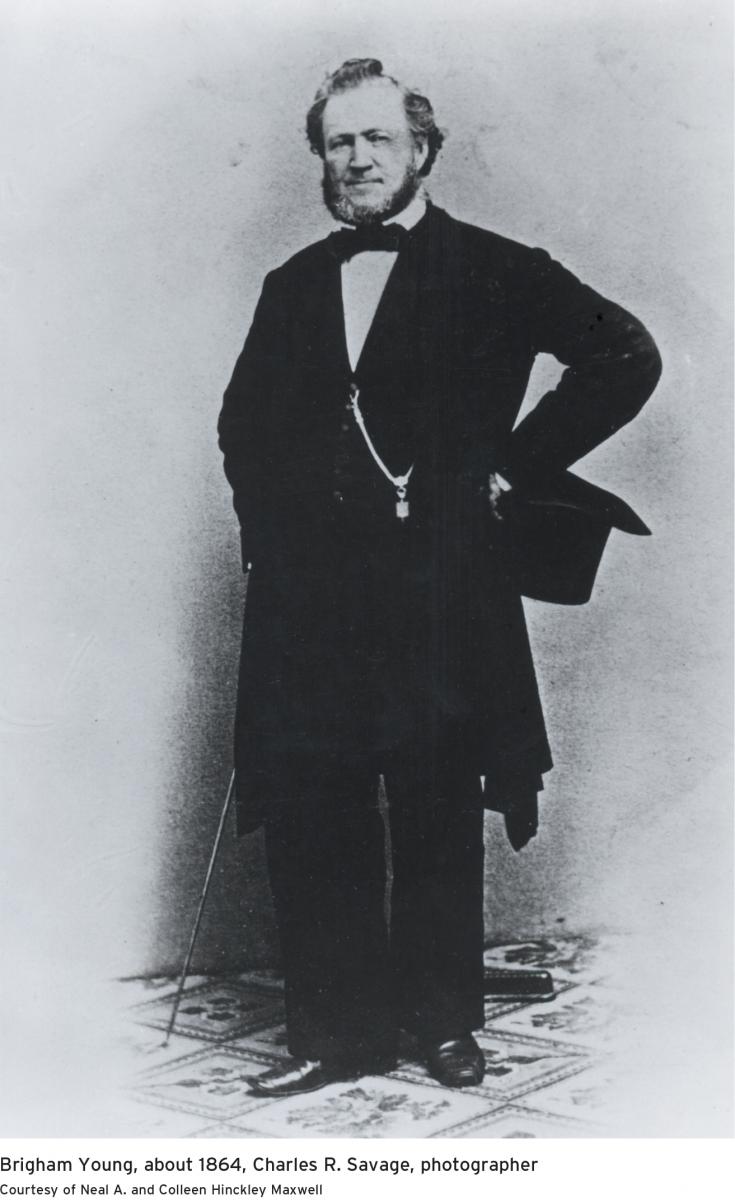

Brigham Young was born to a farming family in Vermont. He learned to work hard early on, and his practical skills and perspective helped him throughout his life. He eventually married and, after years of religious study, learned of the restored gospel and was baptized. A dedicated follower of Christ, Brother Brigham was always loyal to the Prophet Joseph Smith and was committed to the building up of the kingdom of God. Eventually, Brigham was called to be an Apostle and, later, the President of the Quorum of the Twelve. When the Prophet Joseph was martyred, the Quorum of the Twelve guided the Church under President Young’s leadership. He organized and led the Saints’ westward exodus and was ordained President of the Church in 1847.

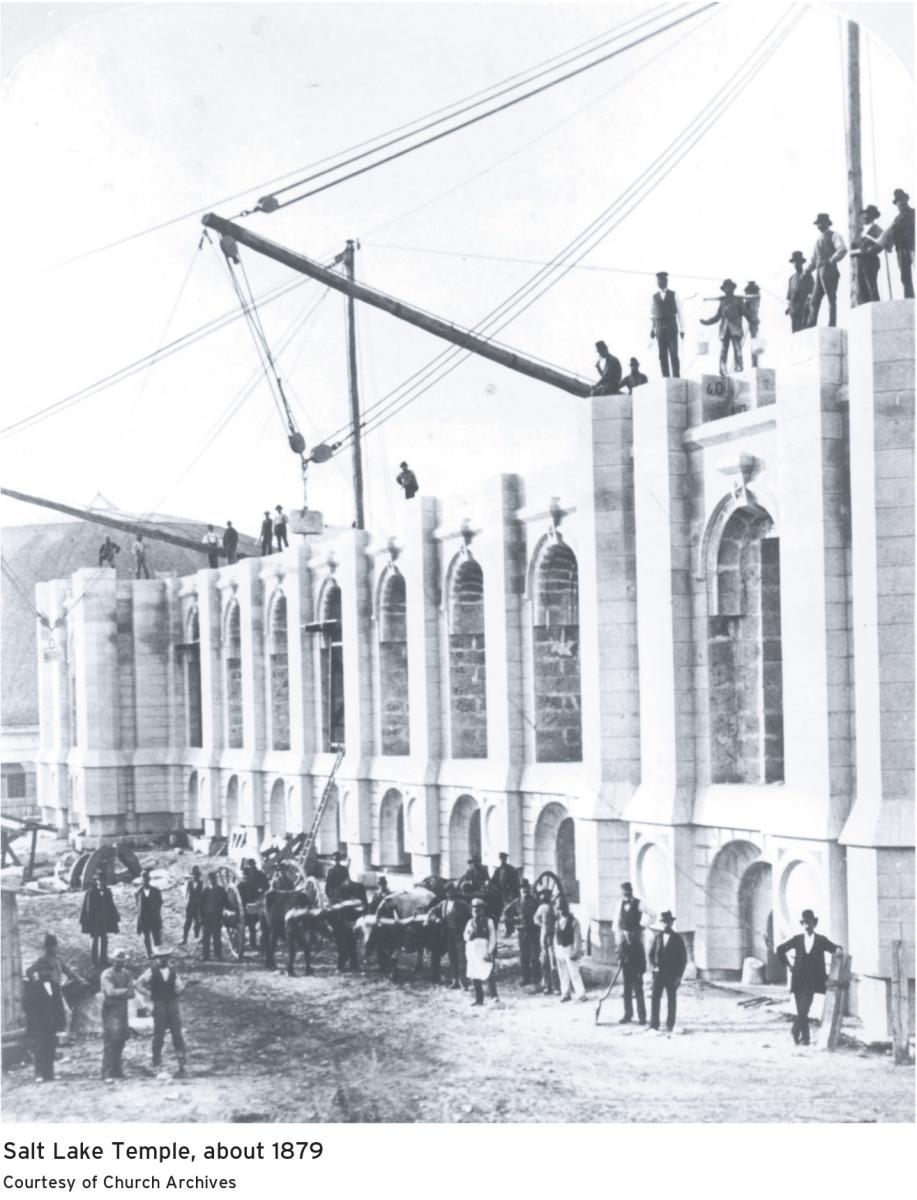

A remarkable colonizer, President Young helped the Saints settle the Great Basin. In a relatively short time, he was elected governor of the provisional state of Deseret, sent settlers throughout the basin, established the Perpetual Emigrating Fund Company, and broke ground for the Salt Lake Temple. Missionary work remained paramount in his administration as he sent missionaries throughout the world.

Life History

Brigham Young was born in Whitingham, Vermont, on June 1, 1801. He was the ninth of eleven children born to John and Abigail Young. Abigail suffered from tuberculosis and had to rely on the children to care for each other and be responsible for the many duties around the house. The family struggled to make a living off the land and, in 1804, moved to central New York in hopes of finding better land to farm. The family was large and poor, so Brigham diligently labored to help with all the necessary chores. He later remarked that there were times when he worked in the “summer and winter, not half clad, and with insufficient food until my stomach would ache.”[1]

When Brigham was only fourteen years old, his mother lost her struggle with tuberculosis and passed away. Her death, combined with the rigors of farm life, helped the boy grow quickly into a man. The children were left in the care of their father who, though a good man, was often very strict. Brigham later said of his father that “it used to be a word and a blow, with him, but the blow came first.”[2] His father sometimes had to leave the children on their own while he worked or got supplies. One time Brigham and his brother were so hungry, with nothing but maple sugar in the house, that Brigham resorted to shooting a robin so the two boys could have something to eat.[3] It was not long after his mother’s death that his father told him it was time to leave home. “When I was sixteen years of age, my father said to me, ‘You can now have your time; go and provide for yourself;’ and a year had not passed away before I stopped running, jumping, wrestling and the laying out of my strength for naught; but when I was seventeen years of age, I laid out my strength in planing a board, or in cultivating the ground to raise something from it to benefit myself.”[4]

Brigham left home and became an apprentice carpenter, painter, and glazier.[5] Over the next five years, he gained a reputation for being a capable and hardworking man. He eventually met and married a beautiful young woman, Miriam Works, and the couple was blessed with two daughters.

Finding Peace in the Restored Gospel

Brigham’s parents belonged to a branch of the Methodist Church and raised their children in a strict religious environment.[6] But despite the fact that young Brigham grew up in such circumstances, studied the Bible, and meditated upon deeply spiritual questions, he did not belong to any church for quite some time. His resistance to the religious teachings of his day was not born of arrogance; he recognized that there was truth in some of what was said, but he wanted to “reach the years of judgment and discretion” so he could “judge” for himself.[7] Brigham tried to live a good, Christian life of morality and utmost integrity, conscientiously studying the Bible and applying its teachings, but he simply could not find a church that appeared to be founded upon those teachings. Finally, about the time of his marriage, Brigham joined the Reformed Methodist Church. He insisted on being baptized by immersion, even though his new church did not believe the method of performing the ordinance was important.[8]

In 1830, Brigham’s older brother Phinehas purchased a copy of the Book of Mormon from Samuel Smith, the young missionary brother of the Prophet Joseph. Phinehas, as well as other members of the Young family, read the book and quickly proclaimed their acceptance of it. Brigham, on the other hand, took more time, carefully studying the book and the church behind it. While he had investigated a number of different religions, this new religion struck him as something very different from all the others. This religion went deeper for Brigham than the others he had examined; it answered his questions and made sense to him. He was careful, however, not to rely only on his practical approach of studying or on the commitment to the new church that others in his family were willing to make. He wanted to pray and feel right about each important aspect of the religion before moving forward.

After studying the Book of Mormon and Bible, meeting with missionaries, and even traveling to Pennsylvania to observe a church meeting, Brigham firmly decided to be baptized. “I examined the matter studiously for two years before I made up my mind to receive that book,” he later said. “I knew it was true, as well as I knew that I could see with my eyes, or feel by the touch of my fingers, or be sensible of the demonstration of any sense. Had not this been the case, I never would have embraced it to this day; it would have all been without form or comeliness to me. I wished time sufficient to prove all things for myself.”[9]

On a snowy day in April 1832, Eleazer Miller baptized Brigham in his own millpond. The next day his close friend Heber C. Kimball was also baptized, and within three weeks, the wives of both men were baptized as well.[10] Eventually, all of Brigham’s immediate family joined the Church. Brigham had found the restored gospel and the joy that comes through living it. “Our religion has been a continual feast to me. With me it is Glory! Hallelujah! Praise God! instead of sorrow and grief. Give me the knowledge, power, and blessings that I have the capacity of receiving. . . . Give me the religion that lifts me higher in the scale of intelligence—that gives me the power to endure—that when I attain the state of peace and rest prepared for the righteous, I may enjoy to all eternity the society of the sanctified.”[11]

Serving the Lord as a New Disciple

Brigham demonstrated his commitment to the restored gospel by his unwavering willingness to diligently serve the Lord and His Church. He devoted much of his time to preaching the gospel, including going on a mission by foot to Canada. He met with personal tragedy once again in his life when his wife, Miriam, passed away from tuberculosis, leaving him to care for their two young daughters. Despite the challenges he faced, he was completely dedicated to the gospel and felt no hesitancy to do what he could to serve in his new religion. “I hear people talk about their troubles, their sore privations, and the great sacrifices they have made for the Gospel’s sake. It never was a sacrifice to me. Anything I can do or suffer in the cause of the Gospel, is only like dropping a pin into the sea; the blessings, gifts, powers, honour, joy, truth, salvation, glory, immortality, and eternal lives, as far outswell anything I can do in return for such precious gifts, as the great ocean exceeds in expansion, bulk, and weight, the pin that I drop into it.”[12]

One especially significant event was his first visit with the Prophet Joseph Smith. Brigham, his brother Joseph, and Heber C. Kimball stayed with family in Kirtland, Ohio, and soon made their way to the Smith home. They were informed that the Prophet was chopping wood. “We immediately repaired to the woods,” Brigham later explained, “where we found the Prophet, and two or three of his brothers, chopping and hauling wood. Here my joy was full at the privilege of shaking the hand of the Prophet of God, and received the sure testimony, by the Spirit of prophecy, that he was all that any man could believe him to be, as a true Prophet.”[13] Brigham was always a true friend to the Prophet and was loyal without question.

In 1833, Brigham moved to Kirtland with his two daughters. “When I went to Kirtland,” he later said, “I had not a coat in the world, for previous to this I had given away everything I possessed, that I might be free to go forth and proclaim the plan of salvation to the inhabitants of the earth. Neither had I a shoe to my feet, and I had to borrow a pair of pants and a pair of boots.”[14] At that time, Kirtland was a village of about thirteen hundred people, set in a beautiful location of rolling green hills near the Chagrin River. While there, he grew closer to the Prophet Joseph, continuing his gospel education. Brigham met Mary Ann Angell, a native of New York who was then living in Kirtland, and the two married on February 18, 1834.[15] While Brigham labored in building homes, he spent most of his time preaching.

Although the Prophet Joseph and many of the Saints resided in Kirtland, about twelve hundred members of the Church had settled in Jackson County, Missouri, to help establish Zion there. Many difficulties arose for the Saints, in Missouri, however. “There, an angry mob, led by a militant minister, destroyed the Mormon store and printing establishment, tarred and feathered the bishop, and finally, in November 1833, drove the Saints from their homes with whippings and plunder. Many houses were burned, live-stock was killed, and furniture and other domestic property were seized and carried away.”[16] Daniel Dunklin, the Missouri governor, promised to help the Saints get their homes back if they would provide him with help in doing so. The Prophet decided to recruit a group of men, called Zion’s Camp, to help. Always a staunch supporter of the Prophet, Brigham was one of the first to volunteer for the camp; he and Heber were chosen to be captains of their respective companies.

The march to Missouri was extremely difficult with little sleep, poor roads, hot weather, and unsanitary eating and drinking conditions. Many of the men complained to the Prophet about their circumstances. “We had grumblers in that camp,” Brigham said. “We had to be troubled with uneasy, unruly and discontented spirits. . . . Brother Joseph led, counselled and guided the company, and contended against those unruly, evil disposed persons.”[17] By the time the men made it to Missouri, the governor had backed away from his promise, deciding not to help the Saints recover their homes.[18] The men of Zion’s Camp received threats of violence but were spared when an approaching mob was stopped by a terrible storm within two miles of Zion’s Camp and had to turn back. The company of Saints saw the hand of the Lord in this and were grateful for His protection. It was just a matter of days later, though, that cholera spread throughout the camp. Sixty-eight members of the camp were afflicted, and fourteen died. Joseph called the men together and told them that if they would humble themselves and covenant to follow his direction, the epidemic would be stopped. The men covenanted to be obedient, and the Prophet’s promise came true. On July 3, 1834, he discharged the group without their having to go to battle.[19]

The Prophet had promised Brigham that if he would follow him to Missouri and keep his counsel, he would come back unharmed.[20] Brigham did indeed return safely, but, sadly, some did not. The Prophet later spoke of how he had a vision in which he saw the men who had died in Zion’s Camp and how the Lord had cared for them. “Brethren, I have seen those men who died of the cholera in our camp; and the Lord knows, if I get a mansion as bright as theirs, I ask no more.”[21]

In the eyes of some members of the Church at the time, Zion’s Camp failed in what was thought to be its purpose. However, it proved to be an important education for many men who would later be leaders in the Church. “Ask those brethren and sisters who have passed through scenes of affliction and suffering for years in this Church, what they would take in exchange for their experience, and be placed back where they were, were it possible,” Brigham said years later. “I presume they would tell you, that all the wealth, honors, and riches of the world could not buy the knowledge they had obtained, could they barter it away.”[22] Brigham gained much from closely associating with the Prophet during this trying time and considered it an important beginning for learning how to lead the Saints. Regarding those who questioned the benefit of Zion’s Camp, Brigham proclaimed, “I told those brethren that I was well paid—paid with heavy interest—yea that my measure was filled to overflowing with the knowledge that I had received by travelling with the Prophet. When companies are led across the plains by inexperienced persons, especially independent companies, they are very apt to break into pieces, to divide up into fragments, become weakened, and thus expose themselves to the influences of death and destruction.”[23]

Loyal Member of the Twelve Apostles

In February 1835, just a few months after Zion’s Camp had returned to Kirtland, Joseph Smith gathered together the veterans of the camp, along with other Church leaders, and announced that the time had come to organize the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and the Quorum of the Seventy. Joseph called upon the Three Witnesses—Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and Martin Harris—to select the Twelve, and they called both Brigham and Heber to be members of the Quorum. Because the first Quorum of the Twelve was organized according to age, Elder Brigham Young was the third in the quorum, and Elder Heber C. Kimball was the fourth. Nine of the twelve men called to the Quorum had served with the Prophet Joseph in Zion’s Camp.[24]

During the summer months, Elder Young served missions in the eastern United States, and for the rest of the year, he helped build up the Church in Kirtland and care for his wife and children. He was involved in painting and finishing the Kirtland Temple, working on the windows, and helping supervise the exterior masonry; later, he participated in the temple’s dedication. Such devotion to building of the first temple in this dispensation was not without sacrifice, for Elder Young found little time to support his family financially and had to rely on the Lord and the help of others. At this time, he was also involved in the School of the Prophets, where he received instruction in the gospel and other subjects, such as history and languages.[25]

Despite the great blessings that flowed from having the temple in Kirtland, a troubling spirit of fierce contention spread throughout the village. Many members of the Church believed that Joseph was unwisely combining the spiritual with the secular and should not allow the Church to be involved in temporal affairs. They blamed him for “meddling” with a financial institution, the Kirtland Safety Society Anti-Banking Association, which ultimately failed.[26] Brigham Young defended him and his inspired role as head of the Church against all critics—even certain members of the Twelve. He knew Joseph was not perfect, but he also knew he was a prophet. The unrest against the Prophet and those who supported him became so severe that Elder Young had to leave Kirtland under the cover of night for his own safety.

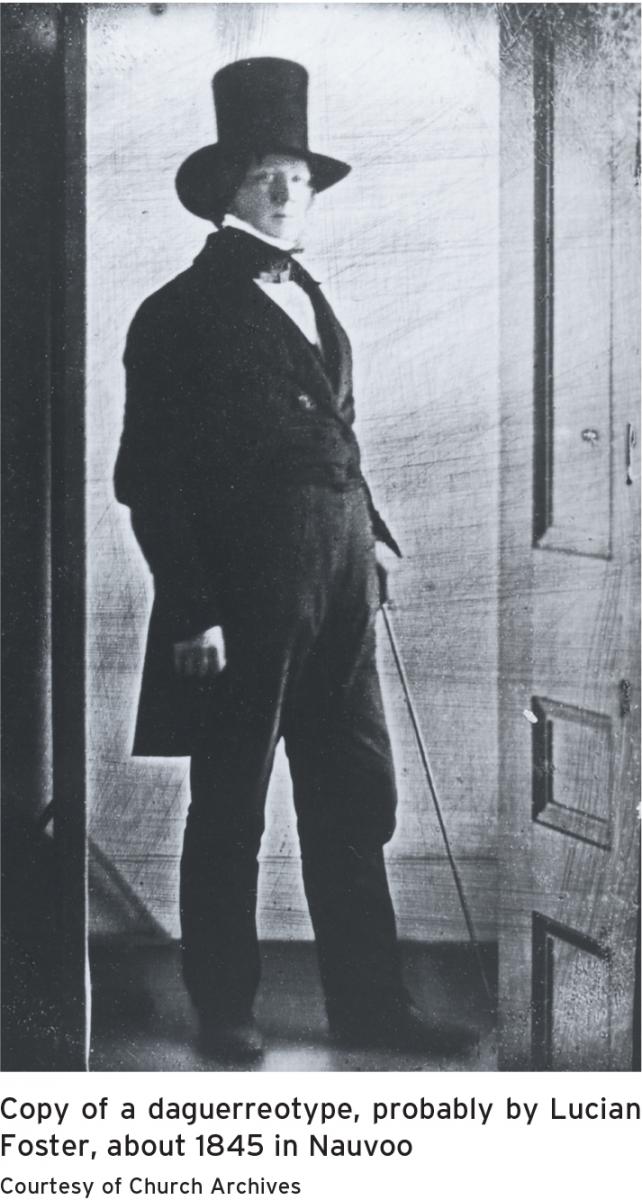

Not long thereafter, the Prophet, Elder Young, and many other Saints began settling in Far West, Missouri. Eventually, the governor of Missouri, Lilburn W. Boggs, issued his infamous “extermination order.”[27] The Saints fled to Nauvoo, a new gathering place that the Prophet Joseph had designated for the members of the Church. After a short time, Elder Young and other members of the Twelve left for missions to Great Britain. Elder Young was extremely ill but refused to listen to his sister’s pleadings for him to wait until he was well. “I was determined to go to England or to die trying,” he said. “My firm resolve was that I would do what I was required to do in the Gospel of life and salvation, or I would die trying to do it.”[28]

In April 1840, the Apostles in England “formally and unanimously” sustained Brigham Young as the President of the Twelve, a role he had filled since 1838.[29] He quickly led his brethren in an extensive program of doing missionary work, publishing, and preparing to help the English Saints immigrate to America. Among their publications were an edition of the Book of Mormon, a hymnbook, and the Millennial Star.[30] After a year of hard work and continual spiritual development, President Young and his brethren had baptized thousands of people. The positive effects of this English mission for the Twelve blessed the Saints for years to come. “As a result of the mission to England, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles came of age precisely at the time its support and strength were needed most. Under Brigham Young’s direction, the Twelve had achieved unprecedented proselyting success and, for the first time, had become an effective agency of ecclesiastical administration.”[31]

After the mission to England, the available members of the Twelve were called together by the Prophet. He announced that the time had come for that quorum to take additional responsibilities in overseeing the affairs of the Church. Also, during this time in Nauvoo, the Prophet instructed the Twelve on four new doctrines and practices: baptism for the dead, plural marriage, the full temple endowment, and the sealing of children to parents.[32] As always, President Young supported the Prophet and followed his teachings, but Brigham found that the doctrine of plural marriage was an especially difficult concept. “I was not desirous of shrinking from any duty,” President Young later said about first hearing of the new practice, “nor of failing in the least to do as I was commanded, but it was the first time in my life that I had desired the grave, and I could hardly get over it for a long time.”[33] After weeks of study and prayer, President Young accepted the doctrine and, with his wife’s consent, married his first plural wife, Lucy Ann Decker Seeley, in June 1842.[34] He married a number of other plural wives throughout his life.

As President of the Quorum of the Twelve, Brigham Young was a very influential man with many responsibilities in Nauvoo. He was president of the quorum that had been charged by the Prophet to take care of such things as “directing missionary work and the work of the gathering” of the Saints, “managing the temporal affairs of the Church,” and “assisting in the building of the Nauvoo temple.”[35] Around March 26, 1844, Joseph conducted a solemn meeting with the Twelve in which he announced that something important was going to happen soon—perhaps he would even be murdered. He bestowed upon them all the keys and powers that he held, thus ensuring the authority needed for the future administration of the Church. [36] Just three months later, this sacred meeting proved to be a priceless treasure to the Saints and their future.

Receiving the Mantle of the Prophet

President Young was away on a mission in Boston when he found himself deeply sorrowful while sitting in a railway station on June 27, 1844. Though he did not know the reason for his “depression of spirit” at the time, he learned weeks later about the martyrdom of the Prophet Joseph and his brother Hyrum.[37] He returned to Nauvoo as quickly as he could, only to find Sidney Rigdon trying to persuade the Saints that he should lead the Church as its “guardian.” Sidney was a member of the First Presidency but had become unsupportive of the Prophet and had moved from Nauvoo. President Young did not wonder about the next course of action, however, because he understood that he and the Twelve held the priesthood keys necessary to lead the Church.

A miraculous event occurred when President Young stood to address the gathered Saints. Many in attendance received a “divine witness” that the mantle of the martyred Prophet had fallen upon him.[38] Many thought President Young sounded and even looked like Joseph as he spoke. In fact, there are at least 101 “written testimonies of people who say a transformation or spiritual manifestation occurred.”[39] As one of the witnesses to this amazing event, Benjamin F. Johnson wrote that “President Brigham Young arose and spoke. I saw him arise, but as soon as he spoke I jumped upon my feet, for in every possible degree it was Joseph’s voice, and his person, in look, attitude, dress and appearance was Joseph himself, personified; and I knew in a moment the spirit and mantle of Joseph was upon him. . . . I knew for myself who was now the leader of Israel. New confidence and joy continued to spring up within me.”[40] The people voted to sustain the Twelve as the leaders of the Church.

Though the Prophet Joseph was gone, his influence was forever with President Young. Brigham wrote one of his daughters about feeling Joseph’s presence in spirit though not in body: “This much I can say—the spirit of Joseph is here, though we cannot enjoy his person. Through the great anxiety of the church, there was a conference held last Thursday. The power of the Priesthood was explained and the order thereof, on which the whole church lifted up their voices and hands for the twelve to move forward and organize the church and lead it as Joseph had. This is our indispensable duty. The brethren feel well to think the Lord is still mindful of us as a people.”[41] Not only did President Young rely on the experiences he had with the Prophet’s teachings and character but he also received counsel from him in spiritual experiences. In one dream, for example, the Prophet Joseph appeared to President Young and taught him the importance of the people’s being humble and following the Spirit. “Tell the people to be humble and faithful,” the Prophet told him, “and be sure to keep the spirit of the Lord and it will lead them right. Be careful and not turn away from the small still voice; it will teach you what to do and where to go; it will yield the fruits of the kingdom. Tell the brethren to keep their hearts open to conviction, so that when the Holy Ghost comes to them, their hearts will be ready to receive it.”[42]

Leading the Saints to the Great Basin

The increasing hostility toward the Church made it clear that the Saints would not be able to stay in Nauvoo much longer. Joseph Smith had spoken of finding a place for them to dwell peacefully west of the Rocky Mountains, and, after much study and discussion, the Twelve decided to lead the Saints in an exodus to the Great Salt Lake Valley. [43] Believing it imprudent to wait, President Young led a group in the snowy cold of February 1846. In leading his people on such a dangerous exodus, he did not leave them so he could travel in comfort; rather, he did all he could to help them. “I would not go on until I saw all the teams up,” he wrote about their departure from Nauvoo. “I helped them up the hill with my own hands.”[44]

During the difficult journey west, having just seen his people forced out of their homes without governmental protection, Brigham received word that U.S. President James Polk had authorized the enlistment of five hundred Mormon men to serve in the U.S. war with Mexico. He realized that this was an opportunity not only to serve the country but also to earn much-needed funds for the exodus west, and he personally visited men and boys to encourage them to volunteer for what would be called the “Mormon Battalion.”[45] Although members of the Mormon Battalion are honored today for “their willingness to fight for the United States, for their march of some two thousand miles from Council Bluffs to California, for their participation in the early development of the West, and for making the first wagon road over the southern route from California to Utah in 1848,” they were also honored by President Young for blessing the Church.[46]

After staying in Winter Quarters, Nebraska, for the winter of 1846–47, President Young headed for the Salt Lake Valley with an advance party. Because he was ill, he did not arrive in the valley with the advance party but came a few days later. On July 24, 1847, he saw the valley and confirmed that it was the right place for the Saints to settle. He identified the spot where the temple would be built and began directing the settling of the valley in such endeavors as farming, surveying, and building. In August, President Young led a group of men back to Winter Quarters to help the families there prepare for the trek to the Great Salt Lake Valley. Later, President Young refused to take praise for the great accomplishment of guiding so many people so far: “I do not wish men to understand I had anything to do with our being moved here, that was the providence of the Almighty; it was the power of God that wrought out salvation for this people, I never could have devised such a plan.”[47]

After President Young returned to Winter Quarters, the Twelve met several times for “lengthy discussions and prayer sessions” concerning how the leadership of the Church should be organized. After much deliberation, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles decided to organize a First Presidency, with Brigham Young as President, in December 1847. They sustained his selection of Heber C. Kimball and Willard Richards as counselors. Three weeks later, the Iowa members of the Church sustained the new First Presidency.[48]

Though President Young had presided over the Church as President of the Twelve, he now presided over the Church as its President. Years before, when Brigham Young was a new convert to the Church, the Prophet Joseph made what must have seemed to be an amazing prophecy at the time. The Prophet said that “the time will come when brother Brigham Young will preside over this Church.”[49] Similarly, Levi Hancock bore his testimony that “one day he was chopping a Beech log with Joseph and saw Br Brigham for the first time. Joseph remarked to him before Brigham came within hearing ‘There is the greatest man that ever lived to teach redem[p]tion to the world and will yet lead this People.’”[50]

President of the Church

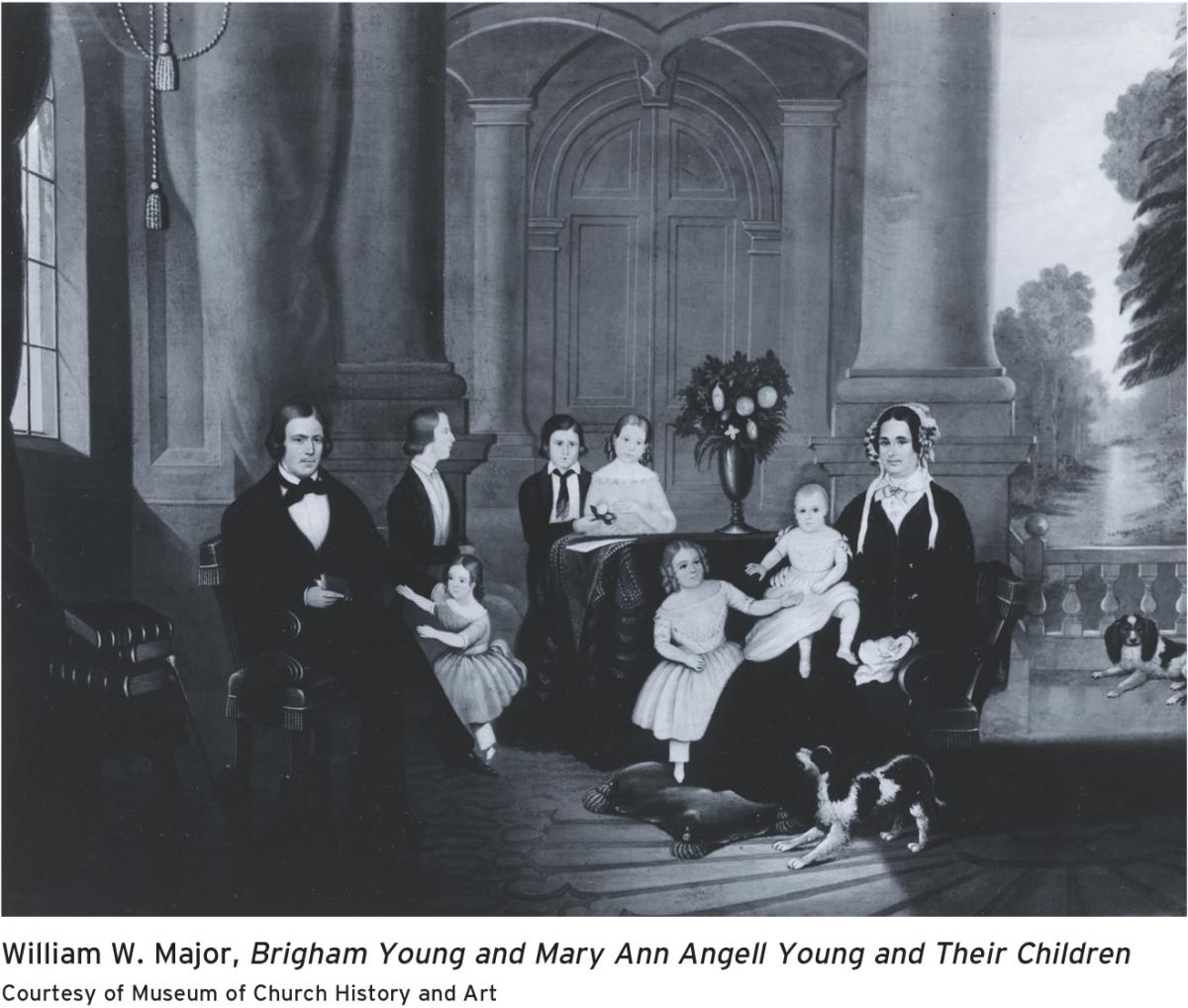

One of the greatest challenges President Young faced was settling the Great Basin area and thereby establish a place for the Saints to gather. “We came to these mountains because we had no other place to go,” he said. “We had to leave our homes and possessions on the fertile lands of Illinois to make our dwelling places in these desert wilds, on barren, sterile plains, amid lofty, rugged mountains.”[51] His great strength as a leader and organizer proved invaluable in meeting these challenges. He led the wide variety of efforts needed to bring in the newly arrived Saints successfully and established the many programs and systems they needed to start their new lives. And always, despite his many heavy responsibilities, President Young was a caring father and husband, actively participating in all the facets of his large family’s life. One of his daughters, Clarissa, shared a particular account of what it was like to have Brigham Young as her father: “Father usually discussed the topics of the day, and then we would all join in singing some familiar songs, either old-time ballads or songs of religious nature. Finally we would all kneel down while Father offered the evening prayers. One distinct phrase in his prayer I shall never forget it so impressed my childish mind was—’Bless the church and Thy people, the sick and the afflicted and comfort the hearts that mourn.’”[52]

In 1849, President Young convened a constitutional convention that created the “state of Deseret”—a vast area, comprising most of present-day Utah and Nevada and portions of Arizona, Oregon, Wyoming, Idaho, Colorado, New Mexico, and California.[53] He was elected governor of this provisional state and considered one of his most important goals to be getting Deseret admitted as a state in the United States. As a first response in 1850, the U.S. Congress changed the name from “Deseret” to “Utah” and established a territorial government for it instead of granting statehood.[54] President Young attempted to gain statehood for the territory several times, but Utah was not granted such status until after his death.

President Young established the Perpetual Emigrating Fund Company in 1849 to help with the immigration of thousands of members of the Church to the area. His vision of settling the Great Basin was not a matter of simply occupying the land; he saw a paradise and had the determination to build it. “Let the people build good houses, plant good vineyards and orchards, make good roads,” President Young taught his people, and “build beautiful cities in which may be found magnificent edifices for the convenience of the public, handsome streets skirted with shade trees, fountains of water, crystal streams, and every tree, shrub and flower that will flourish in this climate, to make our mountain home a paradise and our hearts wells of gratitude to the God of Joseph.”[55]

In 1851, U.S. President Millard Fillmore appointed President Young as superintendent of Indian Affairs of Utah Territory and governor. Though President Young certainly had the support of the people of Utah, he faced many problems working with the appointees who were assigned by the federal government. He did not see them as sympathetic to the Church or to the needs and interests of the people of the territory. Many of the individuals who had been appointed by the federal government in various capacities returned to the East with complaints about President Young and the Saints in general. In addition, the public announcement in 1852 about the practice of plural marriage caused even greater concern among leaders of the United States. By 1857, Washington, D.C. was filled with “rumors and allegations charging the Mormons with murder, destruction of legal records, religiously biased courts, and conspiracy with the native American Indians to promote conflict against non-Mormon immigrants.”[56]

As a result of these allegations and rumors, U.S. President James Buchanan decided to replace President Young with a federally appointed governor and to send part of the U.S. Army to Utah to put down any Mormon rebellion. He did not inform President Young of the military action, so when soldiers were observed heading for the territory, President Young assumed the worst and told his people to prepare to defend their homes. “They never did anything against Joseph till they had ostensibly legalized a mob; and I shall treat every army and every armed company that attempts to come here as a mob,” President Young told the members of the Church.[57] Before any battle became necessary, however, a peaceful solution was agreed upon, and the army occupied Camp Floyd, about forty miles from Salt Lake City. President Young was replaced as governor, and the army left at the start of the Civil War in 1861.

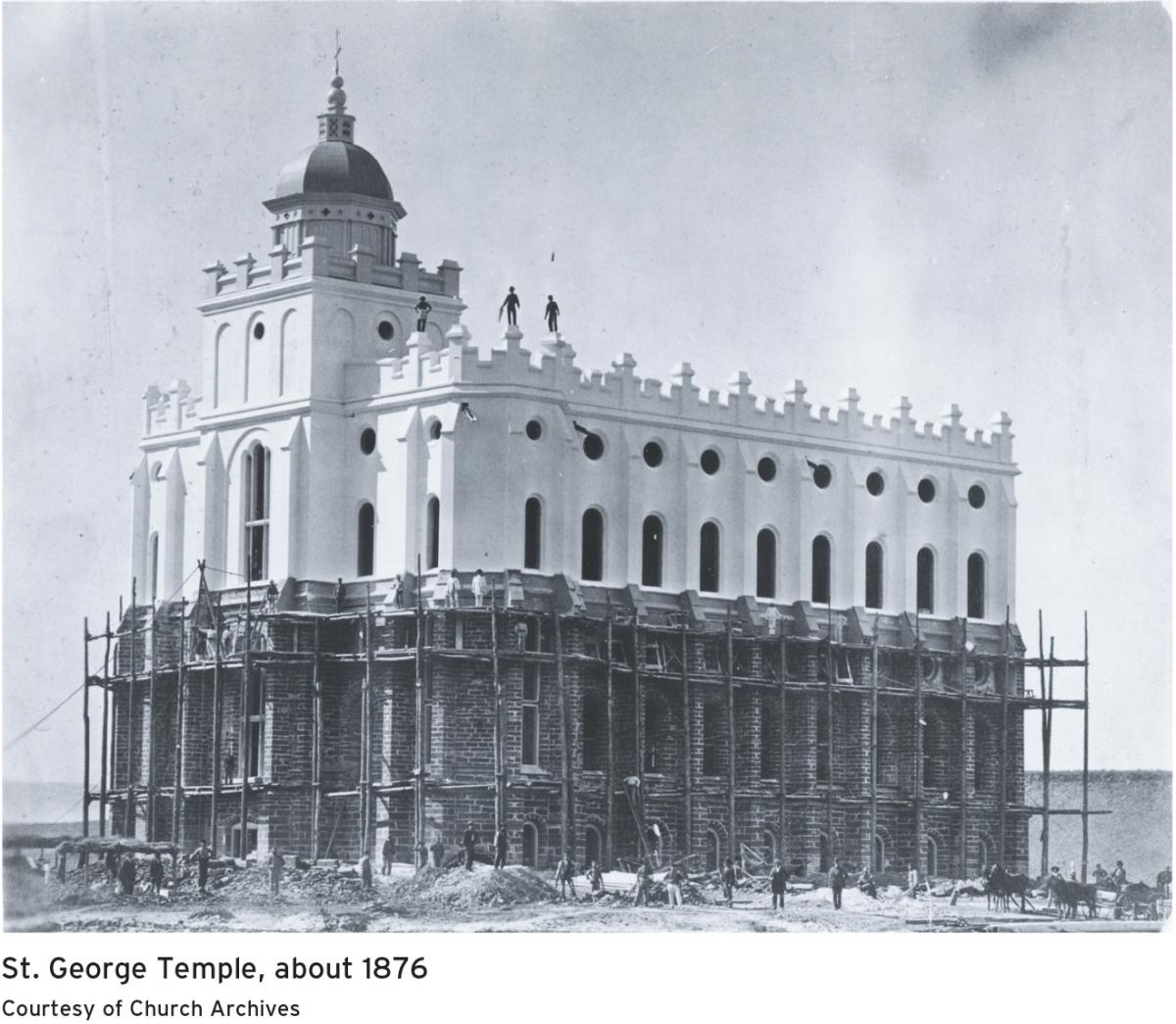

President Young was first and foremost a disciple of Christ. He was a committed member of the kingdom and was willing to serve faithfully and fully in whatsoever role he was called upon to assume. Above such titles as governor or such duties as organizer and colonizer, he was the President of the Church. His organizational abilities and spiritual gifts were great blessings to the Saints. He divided the city into wards and appointed bishops, counseled with countless people, encouraged the Saints to develop their communities as places of education and culture, and sent groups of missionaries to many countries. He gave hundreds of sermons in which he shared his recollections of the Prophet Joseph, his commitment to the restored gospel, and his great views of the doctrines of the kingdom. Always searching to bless the Saints, President Young encouraged the organization of Relief Societies in each ward and established both the University of Deseret (later named the University of Utah) and Brigham Young Academy (later named Brigham Young University). Though he did not live to see the completion of the Salt Lake Temple, he dedicated the temple in St. George, Utah.

President Young taught his people the gospel with great enthusiasm and plainness. He believed in a practical gospel to make a person’s life better not only in the next life but also in this one as well. “Life is for us, and it is for us to receive it to-day, and not wait for the millennium. Let us take a course to be saved to-day, and, when evening comes, review the acts of the day, repent of our sins, if we have any to repent of, and say our prayers; then we can lie down and sleep in peace until the morning, arise with gratitude to God, commence the labours of another day, and strive to live the whole day to God and nobody else.”[58]

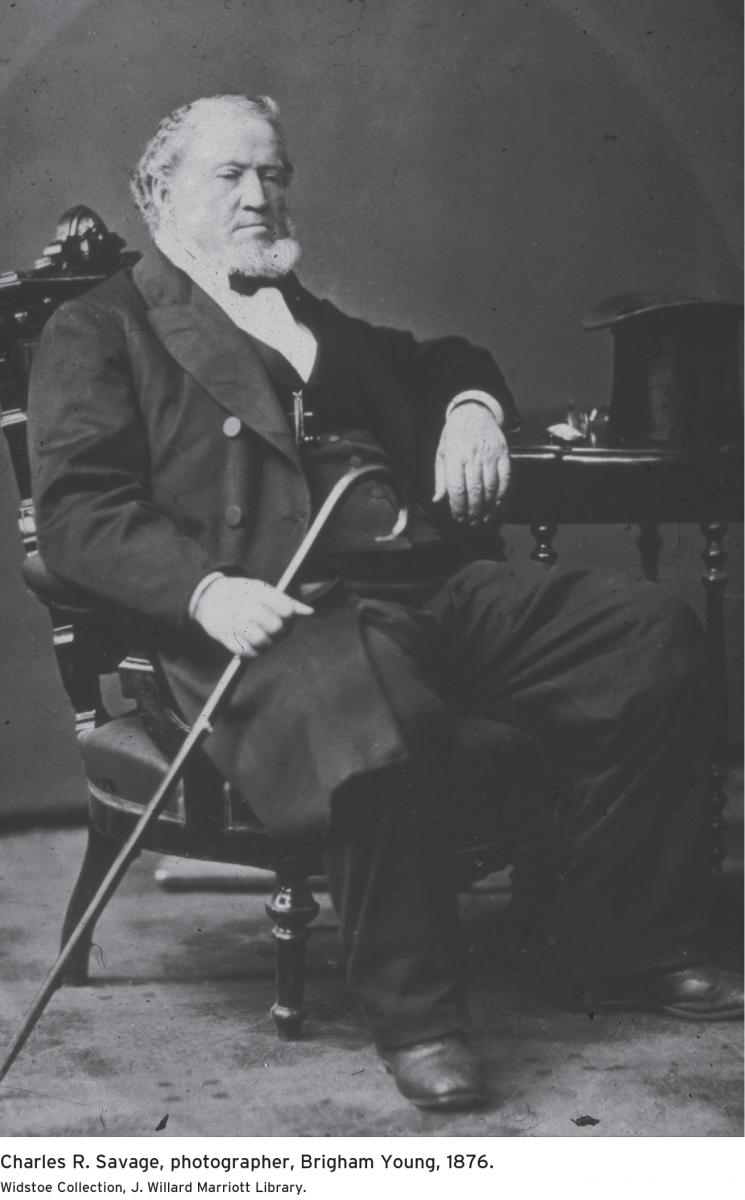

On August 29, 1877, a great period of Church history ended with President Brigham Young’s death. He had been suffering from what doctors now believe to be an infection caused by a ruptured appendix. As one of his daughters wrote, when “he was placed upon the bed in front of the window he seemed to partially revive, and opening his eyes, he gazed upward, exclaiming: ‘Joseph! Joseph! Joseph!’ and the divine look in his face seemed to indicate that he was communicating with his beloved friend, Joseph Smith, the Prophet. His name was the last word he uttered.”[59] Brigham Young was the man the Lord raised up to accomplish overwhelming tasks in an especially difficult time—and accomplish them he did. It is little wonder that he is known as the American Moses, the Lion of the Lord.

Notes

[1] Brigham Young, Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1862), 12:287.

[2] Young, Journal of Discourses, 4:112.

[3] Eugene England, Brother Brigham (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1980), 3.

[4] Young, Journal of Discourses, 10:360.

[5] Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and R. Q. Shupe, My Servant Brigham: Portrait of a Prophet (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1997), 57.

[6] Ronald K. Esplin, “Conversion and Transformation: Brigham Young’s New York Roots and the Search for Bible Religion,” in Lion of the Lord: Essays on the Life and Service of Brigham Young, ed. Susan Easton Black and Larry C. Porter (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1995), 23.

[7] Young, Journal of Discourses, 14:112.

[8] Esplin, “Conversion and Transformation,” 29.

[9] Young, Journal of Discourses, 3:91.

[10] Leonard J. Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses (New York: Knopf, 1985), 30.

[11] Young, Journal of Discourses, 8:119.

[12] Young, Journal of Discourses, 1:313.

[13] Millennial Star, July 11, 1863, 439.

[14] Young, Journal of Discourses, 2:128.

[15] Arrington, American Moses, 37.

[16] Leonard J. Arrington, “Joseph Smith,” in The Presidents of the Church, ed. Leonard J. Arrington (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 28.

[17] Young, Journal of Discourses, 10:20.

[18] Arrington, “Joseph Smith,” 29.

[19] Arrington, American Moses, 42–45.

[20] Preston Nibley, Brigham Young: The Man and His Work (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1965), 15.

[21] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1948), 2:181.

[22] Young, Journal of Discourses, 2:10.

[23] Young, Journal of Discourses, 10:20.

[24] Arrington, American Moses, 48.

[25] Arrington, American Moses, 51–52.

[26] Ronald K. Esplin, “Brigham Young and the Transformation of the ‘First’ Quorum of the Twelve,” in Lion of the Lord, 62.

[27] England, Brother Brigham, 31.

[28] Young, Journal of Discourses, 13:211.

[29] James B. Allen, Ronald K. Esplin, and David J. Whittaker, Men with a Mission, 1837–1841: The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in the British Isles (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 89.

[30] Arrington, American Moses, 81.

[31] Allen, Esplin, and Whitaker, Men with a Mission, 314.

[32] Arrington, American Moses, 100–2.

[33] Young, Journal of Discourses, 3:266.

[34] Arrington, American Moses, 102.

[35] Milton V. Backman Jr., “The Keys Are Right Here: Succession in the Presidency,” in Lion of the Lord, 109.

[36] Arrington, American Moses, 109–10.

[37] Backman, “The Keys Are Right Here: Succession in the Presidency,” 107.

[38] James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 216.

[39] Lynne Watkins Jorgensen and BYU Studies Staff, “The Mantle of the Prophet Joseph Passes to Brother Brigham: A Collective Spiritual Witness,” in BYU Studies 36, no. 4 (1997): 131, 125–204.

[40] Benjamin F. Johnson, My Life’s Review (Independence: Zion’s Printing & Publishing Company, 1979), 103–4.

[41] Brigham Young to Vilate Young, August 11, 1844, Brigham Young Papers, Church Archives, Salt Lake City, as quoted in Holzapfel and Shupe, My Servant Brigham, 72.

[42] Brigham Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 1846–1847, ed. Eldon J. Watson (Salt Lake City: Eldon J. Watson, 1971), 529.

[43] Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 142.

[44] Smith, History of the Church, 7:585.

[45] Susan Easton Black, “The Mormon Battalion: Religious Authority Clashed with Military Leadership,” in Lion of the Lord, 155.

[46] Black, “The Mormon Battalion: Religious Authority Clashed with Military Leadership,” 167.

[47] Young, Journal of Discourses, 4:41.

[48] Arrington, American Moses, 153.

[49] Millennial Star, July 11, 1863, 439.

[50] Charles Lowell Walker, Diary of Charles Lowell Walker, ed. A. Karl Larson and Katharine Miles Larson (Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 1980), 1:422.

[51] Young, Journal of Discourses, 10:223.

[52] Clarissa Young Spencer and Mabel Harmer, Brigham Young at Home (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1968), 33.

[53] Dale F. Beecher, “Colonizer of the West,” in Lion of the Lord, 174.

[54] Beecher, “Colonizer of the West,” 175.

[55] Young, Journal of Discourses, 10:3–4.

[56] Holzapfel and Shupe, My Servant Brigham, 16.

[57] Young, Journal of Discourses, 5:231.

[58] Young, Journal of Discourses, 8:124–25.

[59] Susa Young Gates with Leah D. Widtsoe, The Life Story of Brigham Young (New York: Macmillan, 1930), 362.