“The Loving Friend of Children, the Prophet Joseph”

J. B. Haws

J. B. Haws, “The Loving Friend of Children, the Prophet Joseph,” Religious Educator 3, no. 2 (2002): 19–28.

J. B. Haws was a seminary teacher at the South Ogden Utah Junior Seminary when this was published.

[1] My wife and I were sitting in a special parents’ session of stake conference. The opening musical number was presented by a young family consisting of a smiling couple and their five children. The mother was holding the youngest boy, who could not have been more than two years old. The family was singing “Teach Me to Walk in the Light,” but the two-year-old wasn’t singing. He was suffering from what was probably his first bout of stage fright. He just stared at the microphone. For three verses, he just stared. However, when the song ended and the family members began filing off of the stand, it was as if the microphone’s hypnotic spell was suddenly lifted, and the two-year-old realized he had missed his big debut. A look of terror fell on him. He began to wail, and everyone in the chapel could hear what he was screaming: “I want to walk in the light! I want to walk in the light!” He was still pleading his case as his embarrassed mother and giggling siblings exited into the foyer.

We all smiled, and the meeting continued. But we sensed something special about that little boy’s cry—something that left a deep impression on us. “I want to walk in the light!” What a powerful declaration! It brought to mind Book of Mormon descriptions of times when He who is the Light of the World “did teach and minister unto the children of the multitude” and “great and marvelous things” resulted (3 Nephi 26:14). I couldn’t help but think of President J. Reuben Clark’s landmark statement, “The youth of the Church are hungry for things of the Spirit; they are eager to learn the gospel, and they want it straight, undiluted.”[2] I could picture thousands of young men and young women standing and shouting, in unison, “I want to walk in the light!”

That little toddler capsulated the heartfelt prayers and the spiritual hunger of the noble young people who fill the classrooms of the Church. But every so often it is tempting to get a little cynical and ask if that is still their heartfelt prayer when they are sleepy on a hot afternoon in May or when the alarm goes off long before the sun rises on a Monday in January. Is there a way, even at those difficult times, to present the gospel “straight” and “undiluted”?

When questions like these challenge us, it helps to look at comments made by the youth in Joseph Smith’s era. The statement of eleven-year-old Alvah Alexander whispers hope to our doubting hearts and causes us to sit up and take notice. Alvah said, “No amusement or games were as interesting to me as to hear [the Prophet Joseph Smith] talk.” [3] Mary Field Garner, a seven-year-old, said similar things. Even though her father had passed away and the impoverished family was reduced to rations of one pint of meal a day, she said, “We did not complain. . . . We were too thankful to be at Nauvoo . . . and listen to [Joseph Smith’s] teachings.”[4] Teenager Goudy Hogan was “very anxious to go to meeting,” even though it meant walking eight miles from his home to Nauvoo.[5] And young John Pulsipher, like so many others, thrilled at the chance to hear the Prophet’s “instruction weekly and sometimes daily.”[6] We begin to sense that we have an answer when cynical thoughts arise about real chances for edification through teaching. We have the Prophet Joseph Smith.

What was it about Joseph Smith that so powerfully affected the young people who associated with him? That question is not easy to answer because there is so much to the Prophet—so much that is remarkable, inspiring, and worth emulating. Still, an important insight into the Prophet’s power comes through a statement by President Boyd K. Packer when he voiced this timeless principle: “The attributes which it has been my choice privilege to recognize in [ideal teachers] . . . are no more nor less than the image of the Master Teacher showing through.”[7] Most simply stated, the Prophet’s greatness grew out of his efforts to be like the Savior.

Joseph Smith emulated the Savior in teaching doctrine, in using priesthood power, in forgiving enemies, and ultimately in being willing to suffer persecutions unto death. But the Prophet’s character takes on a new depth when we see how he emulated the Savior in associations with children. Children who knew him revealed what it was that made Joseph Smith so heroic: he loved them with a love that the Savior had both commanded and exemplified. The recollections of young Saints remind us of principles that are applicable in every Church classroom, because these recorded memories show how the Prophet took to heart the charge that the Lord had given to Peter centuries earlier to “feed my lambs” (John 21:15). Joseph Smith fed the youth again and again with his words, his example, and, most important, his loving attention. He fed them in a way that can teach each of us, because he fed them just as the Master Teacher had done in the meridian of time.

The Power of Plainness

The early Saints repeatedly reveal that one component of the Prophet’s power was his plainness. Daniel Tyler remembered the specifics of one sermon after almost sixty years because Joseph Smith made it “so plain that a child could not help understanding it.”[8] The Prophet, like the Savior, used illustrations and examples to teach truth in simplicity. He wanted the children to learn the gospel. When he taught about prayer, he said, “Be plain and simple and ask for what you want, just like you would go to a neighbor.”[9] When he sent out missionaries, he told them, “Make short prayers and short sermons.”[10] The simplicity and the illustrations worked. One little girl, Henrietta Cox, was deeply impressed by such a lesson, even though she was only six at the time. A brother chided Joseph for “being bowed in spirit” and told him to “hold [his] head up.” Joseph replied that “many heads of grain in that field [bend] low with their weight of valuable store, while others there [are] which, containing no grain to be garnered, [stand] very straight.”[11] It was a short sermon, but a child never forgot it.

“To him,” Mercy Thompson observed, “all things seemed simple and easy to be understood, and thus he could make them plain to others as no other man could that I ever heard.”[12] Like the Master, Joseph Smith wanted “the most unlearned member . . . [to] know and understand the truth.”[13] And because of this simplicity and purity, his teachings, like the Master’s, were ratified by the Spirit. Daniel Tyler said the power of the Spirit “filled the house where we were sitting,” listening to a sermon.[14] Sariah Workman remembered, “I always felt a divine influence whenever I was in his presence. The Holy Ghost testified to me then.”[15] The Spirit that accompanied Joseph’s words led Mary Westover to decide, “as [she] sat there, that the Lord was speaking through Joseph.”[16] Even when the Prophet would stop in for a baked potato or a piece of pie, young James Henrie “felt the Spirit and power of God come” as Joseph “always [asked] God to bless them. . . . [James] knew beyond any question of doubt that [Joseph] was a Prophet of God, and he loved him better than anyone he ever knew in his life.”[17] What “great and marvelous things” these testimonies are, and they are testimonies that came as Joseph Smith followed the Savior’s example and taught the gospel in a way that children could understand. But the Prophet’s most lasting teaching came not from what he said to the children but from what he did when he was with the children. He, like the Lord, taught by precept and example.

The Power of Example

When the Savior gently corrected the disciples and told them to “suffer little children . . . to come unto me,” He wasn’t speaking figuratively. He let the children physically come close enough that He could “[lay] his hands on them” (Matthew 19:13–15). Some might say that this was a dangerous move, because proximity brings added responsibility. It is difficult to hide questionable words and actions when others are nearby. But the Savior was never afraid to have children see Him in His everyday setting, and neither was the Prophet. In that context, Brigham Young’s statement becomes even more telling: “I do not think that a man lives on the earth that knew [Joseph Smith] any better than I did; and I am bold to say that, Jesus Christ excepted, no better man ever lived or does live upon this earth.”[18] This is a powerful testimony because those who know us best also know best our shortcomings. For President Young to declare that he knew Joseph intimately and still felt he was the best of men speaks volumes about the Prophet’s character and about his power as a teacher.

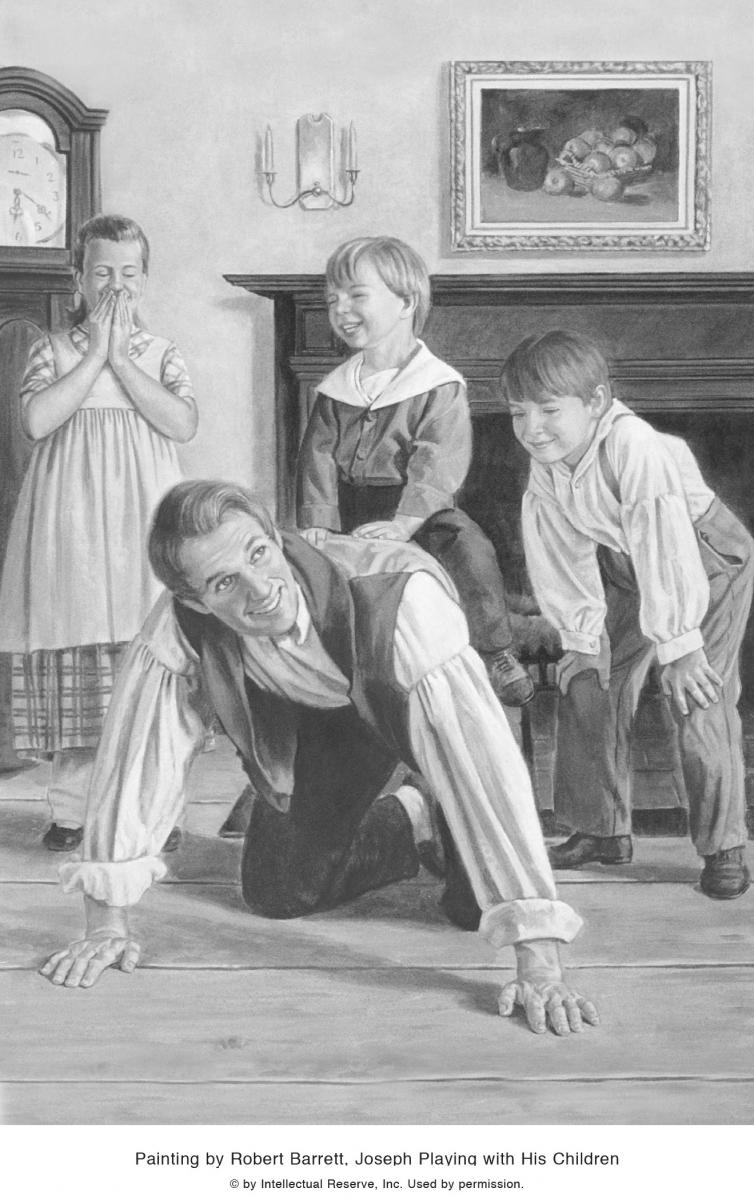

Joseph Smith wanted the children around, wanted them to know what he was doing, and wanted to work and play alongside them. He, like the Savior at Judea, did not mind taking time out of his schedule to be with them, even when it was “inconvenient.” Those who knew him understood that in this way he could teach by the power of example.

Truman Madsen relates an experience that Harvey Cluff had with the Prophet. When the ushers at a meeting, like well-meaning disciples, got too severe with young people who were moving to the side of the makeshift pulpit in one of Nauvoo’s groves, Joseph Smith said, “Let the boys alone, they may hear something that they will never forget.” More likely, by being close to him, they would see and feel something they would never forget. In fact, Harvey Cluff reported that incident was his first impression of the divinity of Joseph Smith’s calling.[19] Others had similar impressions as they associated with “Brother Joseph.”

The Prophet is famous for his love of playing games with the children, but in this he taught great lessons about the need for a proper balance in life. When the study of Greek and Latin became too tiring, he “would go and play with the children in their games about the house to refresh himself before returning to work.”[20] His willingness to take his “little Frederick” to go “sliding on the ice” taught all the children who were with him that day the preeminence of “family” in the mind of the Prophet.[21]

More often than not, Joseph Smith followed a game with a lesson about work or service. He did not preach; he simply did. Enoch Dodge played ball with the Prophet and “the boys” many times, and often after a game, Joseph Smith said, “‘Well, I must go to my work.’ He would go and all the boys would stop playing and go home as he did. This showed his great influence.”[22] Because those close to him saw how hard he worked, they themselves were motivated to do better. Joseph Bates Noble traveled 250 miles to meet Joseph Smith at Kirtland, but when he arrived, the Prophet informed him that he was on his way to the hayfield. He said Brother Noble could join him if he wanted. Joseph Noble stayed in Kirtland for nine days, and on six of those days he worked with the Prophet. Brother Noble recorded that “much good instruction was given by President Joseph Smith.”[23] Example is a powerful sermon.

John Pulsipher saw Brother Joseph work “with his own hands, quarrying stone for [the temple] walls.”[24] It should not be surprising, then, that boys like Jonathan Ellis Layne, an eight-year-old, would want to help cut wood for the temple.[25] Edwin Holden remembered a time when, after playing “various out-door games with the boys, Joseph noticed that some were getting “weary. He saw it, and calling them together he said: ‘Let us build a log cabin.’ So off they went, Joseph and the young men, to build a log cabin for a widow woman.”[26] It is doubtful that any discourse on “pure religion” could have had a greater impact. A nine-year-old boy learned in Nauvoo what it meant to “love thy neighbor” when his father’s wagon got stuck in a mudhole. Brother Bybee, the father, was just about to go get help, when along came a man who waded into the mud “halfway to his knees” and helped free the wagon. The helper’s identity was revealed when the boy’s father called out, “Thank you, Brother Joseph.”[27]

Like the Savior, the Prophet was never too busy to stop and give of his time to children. When a Nauvoo homeowner shooed away a group of would-be ballplayers from his house, the children became depressed. Joseph Smith, who was passing by, noticed their despair and took them all to Main Street and taught them to play a game called “tippies.”[28]

The Prophet even interrupted meetings if he felt he needed to help a child. One day, while conducting a city council meeting, he saw through the window two boys fighting a block away. He excused himself from the meeting, ran to the boys, and pulled them apart. He told them that only he, the mayor, was allowed to fight in Nauvoo. Then, “with a twinkle in his eye,” he said, “Next time you feel like fighting come to my home and ask for a fight and I’ll fight you, and it will be legal.”[29]

Is it surprising then that children wanted to be close to him and that he wanted to be close to them? Just as the Lord had done almost two thousand years before, Joseph Smith allowed children to come close so he could touch them with his example and his character and his spirit. But perhaps more than that, he wanted them to be close so that he, like the Savior, could bless them with his love and attention.

The Power of the “One-by-One” Principle

Elder Frank Y. Taylor shares a story that is similar to experiences that Mosiah Hancock and Margarette McIntire Burgess also had. It was about a group of boys who were walking barefoot during a storm down a muddy street in Far West, Missouri. The boys were all crying because of the cold. Joseph Smith came along on horseback and carried each boy, one by one, to solid ground, and then he used his silk handkerchief to warm up their feet.[30] This image reminds us of the Book of Mormon ministry of Jesus Christ when “he took their little children, one by one, and blessed them, and prayed unto the Father for them” (3 Nephi 17:21). There is something so special about the way that Joseph Smith and the Master both took the children “one by one, and blessed them.” Joseph’s majesty reached soaring heights when he was on his knees, talking and holding and loving a little child.

My great-great-grandfather is Archibald Gardner, and one of his wives, who had lost her first husband, shared a jewel of a personal experience she had with the Prophet. Her name is Abigail Bradford, and she and her first husband were taking their little son Rawsel to the doctor where, they feared, their son’s “hand would have to be amputated. On the way they met the Prophet Joseph. He examined the injured hand and told them to return home as it would be all right, and it was.”[31] Abigail probably understood a little better the wondrous joy that must have come to the widow of Nain for an unexpected blessing to her child.

Margarette McIntire Burgess called the Prophet “the loving friend of children” because she had felt that love during a special blessing. “One morning,” she recorded, “I had a very sore throat. It was much swollen and gave me great pain. He took me up in his lap, and gently anointed my throat with consecrated oil and administered to me, and I was healed. I had no more pain nor soreness.”[32] I am sure that William McIntyre, Margarette’s father, knew a little more of Jairus’s relief.

It is impossible to know how many children, like Barbara Belinda Mills Haws, could tell about talking with the Prophet while sitting “on his knees.”[33] He was so tender and so aware of every person, young or old. He once ran out of his store to greet a young passerby, David Smith, who said “it made him feel so good to have the Prophet of God take so much pains to come out to shake his hand and bless him, he felt it through his whole system.”[34] Imagine the impact that Joseph Smith had on the life of eight-year-old Jesse Smith. Jesse was on his way to school when the Prophet called him over, talked with him, and gave him a copy of the Book of Mormon for school.[35] And these are not isolated incidents. “When wagon loads of grown people and children came in from the country to meeting, Joseph would make his way to as many of the wagons as he well could and cordially shake the hand of each person. Every child and young babe in the company were especially noticed by him and tenderly taken by the hand, with his kind words and blessings.”[36] We say with Margarette McIntire Burgess, “Was it any wonder that [they] loved that great, good and noble man of God?”[37]

Two final anecdotes show just how completely the Prophet followed the “one-by-one” principle. Mercy Thompson, whose husband, Robert, died at Nauvoo, related that “when riding with [the Prophet Joseph] and his wife Emma in their carriage I have known him to alight and gather prairie flowers for my little girl.”[38] Mary Ann Winters and her father were sitting next to the Prophet on a steamboat trip. Mary Ann was tired, and she said, “Pa took me in his arms to rest. Brother Joseph stopped speaking, stooped and took my feet on his knees and when I would have drawn them away, he said, ‘No, let me hold them; you will rest better.’”[39] It is significant to me that the man who carried the weight of the kingdom would think first of the happiness and comfort of two little girls. Joseph Smith had truly internalized the Savior’s words that “inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me” (Matthew 25:40).

I am sure that Joseph Smith loved and respected and treated children as equals because he knew what a child’s prayer could bring to pass. I am sure he listened to children because he knew what it felt like to be spurned by adults. And I am sure he held so many babies because he knew the pain of empty arms. This hero knew that “of such is the kingdom of heaven.”

A True Prophet

Even after all of these instances, too much is still left unsaid about the Prophet and his relationship with children. Scores of Latter-day Saint youth were taught the gospel through Joseph Smith’s words, his example, and his love. These children loved him so much that they wanted to be his bodyguards, they wanted to cut firewood for him, and they were especially delighted when they could give him the “mammoth musk melon” they had grown on their farm.[40] They used the words “noble” and “godlike” and “heavenly” and “great” over and over whenever they described him. They talked about the thrill they had when they first shook his hand or how they picked him out of a crowd before they had even met him. They would all shout “Amen!” to what Daniel McArthur remembered: “To me he seemed to possess more power and force of character than any ordinary man. I would look upon him when he was with hundreds of other men, then he would appear greater than ever. My testimony is that he was a true Prophet of the living God.”[41]

Although I never disembarked at the Nauvoo landing and although I never sat through a meeting in the grove, Brother Tyler’s stirring words ring true to me. I can say, with Elder Frank Y. Taylor, “I was not, of course, acquainted with the Prophet Joseph Smith,” but these eyewitnesses were “intimate with him, and hundreds of times I have listened to [them] discourse on the merits and graces that characterized the Prophet, and I learned to love him more dearly . . . because he loved all persons, little children and all. . . . The kindness of the Prophet Joseph . . . struck me as being very similar to the character of our Savior.”[42] That is why Joseph Smith is a hero, a giant among men, whether viewed through the eyes of the young or the old.

That is also why the Prophet is a hero for gospel teachers everywhere. We too would do well to focus on plainness in our teachings by using illustrations and straightforward explanations. We too can feel the ratifying influence of the Holy Ghost in our classrooms as pure testimonies are borne. We too can show that we enjoy being with the young people by “working” with them in the scriptures, by sharing their concerns and joys, and by smiling and laughing with them. We too can live the gospel in such a way that there is power not only in our words but also in the integrity of our lives. And perhaps most important, we must take “especial notice” of all students to pull them “out of the mud,” “to dry their tears,” and to help heal wounds. We too should always have time to pick the flowers that would mean so much to a struggling child. We too must remember that the Savior blessed the children “one by one.”

Jane Snyder Richards recalled “that upon one occasion when [the Prophet Joseph Smith’s] enemies were threatening him with violence, he was told that quite a number of little children were then gathered together praying for his safety. Upon hearing of that he replied: ‘Then I have no fear; I am safe.’”[43] This little story speaks volumes about faith and trust and love. It also speaks volumes about how we should view the little ones who are all around us, whose hearts truly are the “holy places that must be neither polluted nor defiled.”[44] Therefore, when we think of Joseph Smith, we can think of a prophet—and a teacher—who magnified the charge to be like the Son of Man and to feed all the Father’s children. It is now left to us to go and do likewise.

Notes

[1] This line in the title comes from Margarette McIntire Burgess, “Recollections of the Prophet Joseph Smith,” Juvenile Instructor, 1 January 1892, 66. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2001 BYU Religious Education Student Symposium and later included in Selections from BYU Religious Education 2001 Student Symposium (Provo, Utah: BYU Religious Education, 2001), 119–27.

[2] President J. Reuben Clark Jr., “The Charted Course of the Church in Education,” in Charge to Religious Educators, 3d ed. (Salt Lake City: Church Educational System, 1994), 4.

[3] Alvah Alexander, “Joseph Smith, the Prophet,” Young Woman’s Journal, December 1906, 541.

[4] Mary Field Garner, Autobiography, typescript, Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, 4.

[5] William G. Hartley, “Joseph Smith and Nauvoo’s Youth,” Ensign, September 1979, 28.

[6] Diary of John Pulsipher, vol. 1, typescript, Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, 13.

[7] Boyd K. Packer, “The Ideal Teacher,” in Charge to Religious Educators, 22.

[8] Daniel Tyler, “Recollections of the Prophet Joseph Smith,” Juvenile Instructor, 1 January 1892, 93. In 1892, the Juvenile Instructor had a feature in each edition called “Recollections of the Prophet Joseph Smith.” This special addition to the magazine highlighted reminiscences sent in by Latter-day Saints who had personally known Joseph Smith. The feature appeared from January to October. Dozens of these firsthand memories were published, and because of that, volume 27 is a treasure! It should also be noted that many of the reminiscences cited here have been published in Hyrum L. Andrus and Helen Mae Andrus, comps., They Knew the Prophet (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1999).

[9] Henry W. Bigler, “Recollections,” Juvenile Instructor, 1 March 1892, 151.

[10] Bigler, “Recollections,” 152.

[11] Henrietta Cox, “Recollections,” Juvenile Instructor, 1 April 1892, 203.

[12] Mercy R. Thompson, “Recollections,” Juvenile Instructor, 1 July 1892, 399. 13. Garner, Autobiography, 2.

[13] Garner, Autobiography, 2.

[14] Daniel Tyler, “Recollections,” Juvenile Instructor, 1 February 1892, 94.

[15] Sariah Workman, “Joseph Smith, the Prophet,” Young Woman’s Journal, December 1906, 542.

[16] Workman, “Joseph Smith, the Prophet,” 545.

[17] Manetta Prince Henrie, Ancestry and Descendants of William Henrie, 1799–1883, Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, 154.

[18] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 9:332, in Dallin H. Oaks, “Joseph, the Man and the Prophet,” Ensign, May 1996, 73.

[19] Truman G. Madsen, Joseph Smith the Prophet (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1989), 55, 154.

[20] John W. Hess, “Recollections,” Juvenile Instructor, 15 May 1892, 302; see also William G. Hartley, “Joseph Smith and Nauvoo’s Youth,” Ensign, September 1979, 27.

[21] Leonard J. Arrington, “The Human Qualities of Joseph Smith, the Prophet,” Ensign, January 1971, 37; T. Edgar Lyon, “Recollection of ‘Old Nauvooers’: Memories from Oral History,” BYU Studies 18 (winter 1978): 148.

[22] Enoch Dodge, “Joseph Smith, the Prophet,” Young Woman’s Journal, December 1906, 544.

[23] Journal of Joseph Bates Noble, typescript, Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, 4.

[24] Diary of John Pulsipher, vol. 1, 11.

[25] Writings and History of Jonathan Ellis Layne, typescript, Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, 3.

[26] Edwin Holden, “Recollections,” Juvenile Instructor, 1 March 1892, 153.

[27] Lyon, “Recollection of ‘Old Nauvooers’: Memories from Oral History,” 147–48.

[28] Lyon, “Recollection,” 145.

[29] Lyon, “Recollection,” 144–45.

[30] Frank Y. Taylor, in Conference Report, October 1905, 30; see also Mosiah Lyman Hancock, The Life Story of Mosiah Lyman Hancock (n.p., n.d.), 3.; Leon R. Hartshorn, comp., Classic Stories from the Lives of Our Prophets (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1981), 13.

[31] Delila Gardner Hughes, The Life of Archibald Gardner, 2d ed. (Draper, Utah: Review and Preview Publishers, 1970), 154.

[32] Burgess, “Recollections,” 66.

[33] History of Barbara Belinda Mills Haws, papers in possession of my father, Greg W. Haws.

[34] David Smith, “Recollections,” Juvenile Instructor, 15 August 1892, 471.

[35] Jesse Smith, “Recollections,” Juvenile Instructor, 1 January 1892, 24.

[36] Louisa Y. Littlefield, “Recollections,” Juvenile Instructor, 1 January 1892, 24.

[37] Burgess, “Recollections,” 66.

[38] Thompson, “Recollections,” 399.

[39] “Joseph Smith, the Prophet,” Young Woman’s Journal, December 1905, 558.

[40] Samuel Miles, “Recollections,” Juvenile Instructor, 15 March 1892, 174.

[41] Daniel McArthur, “Recollections,” Juvenile Instructor, 15 February 1892, 128–29.

[42] Frank Y. Taylor, in Conference Report, October 1905, 30.

[43] Jane Snyder Richards, “Joseph Smith, the Prophet,” Young Woman’s Journal, December 1905, 550.

[44] Clark, “The Charted Course,” 8.