Conquest of the Heart: Implementing the Law of Consecration in Missouri and Ohio

Blair G. Van Dyke

Blair G. Van Dyke, “Conquest of the Heart: Implementing the Law of Consecration in Missouri and Ohio,” Religious Educator 3, no. 2 (2002): 45–65.

lair G. Van Dyke was an institute instructor at the Orem Utah Institute of Religion when this was published.

A willingness to subscribe to the law of consecration serves as a key indicator of the condition of the heart of a Latter-day Saint. Consider the words of Elder Orson F. Whitney:

Ah reader, the redemption of Zion is more than the purchase or recovery of lands, the building of cities, or even the founding of nations. It is the conquest of the heart, the subjugation of the soul, the sanctifying of the flesh, the purifying and ennobling of the passions. Greater is he who subdues himself, who captures and maintains the citadel of his own soul, than he who, misnamed conqueror, fills the world with the roar of drums, the thunder of cannon, the lightning of swords and bayonets, overturns and sets up kingdoms, lives and reigns as king, yet wears to the grave the fetters of unbridled lust, and dies the slave of sin.[1]

Simply, the tenets of the law of consecration deal with what we are becoming, not what we are accumulating. As Elder Neal A. Maxwell explained: “We tend to think of consecration only as yielding up, when divinely directed, our material possessions. But ultimate consecration is the yielding up of oneself to God. Heart, soul and mind were the encompassing words of Christ in describing the first commandment, which is constantly, not periodically, operative (see Matt. 22:37). If kept, then our performances will, in turn, be fully consecrated for the lasting welfare of our own souls.”[2]

Knowing these things, we recognize that it is unfortunate the law of consecration is frequently perceived to be, and is often presented in Church instruction exclusively as, a temporal welfare program. Although there are important temporal elements of the law of consecration that will be explored in this article, temporality is not the ultimate focus of consecration. The basic principles of consecration are outlined in the account of the people of Enoch in the Pearl of Great Price. There we learn that the ancient Saints of that community (1) were of one heart; (2) were of one mind; (3) dwelt together in righteousness; and, therefore, (4) lived without any poor among them (see Moses 7:18). With these basic principles always in mind, in this article I will take a two-pronged view of the law of consecration that may lead to more well-rounded instruction regarding this important law.

First, we will consider the historical context of the revelations received by Joseph Smith regarding the law of consecration. A general awareness of the setting wherein these revelations were received is imperative to understanding the doctrinal development of the law of consecration as the Lord revealed it to the Saints, line upon line and precept upon precept. Second, we will explore some of the practical ways through which the principles of the law of consecration have been put into practice since the initial revelations on consecration were received in 1831. Apparently, from the historical context of the coming forth of the law of consecration in the last days and from the scriptural record, the intent of the law is to focus the attention of Latter-day Saints on attaining a separation from worldly pursuits while encouraging wholehearted devotion to God and a unified and lasting concern for the welfare of the Saints.

Historical Overview—Parley P. Pratt and Sidney Rigdon

The conversion of Parley P. Pratt was a benchmark occurrence in the coming forth of the law of consecration. His conversion served as a catalyst to a series of events that resulted in almost doubling the Church population in a three-week period of time. This, in turn, led to the Church headquarters being located in Ohio, where Joseph Smith received initial principles of the law of consecration in February 1831.

Early in 1830, Parley P. Pratt was proselytized by a Reformed Baptist preacher named Sidney Rigdon in northeastern Ohio. Rigdon and Pratt were seekers. They acknowledged that they did not have legitimate priesthood authority and were seeking for a religious movement that precisely mirrored the first-century Church of Christ as described in the New Testament. Specifically, they were searching for an organization that claimed legitimate apostolic authority, the laying on of hands, prophecy, visions, revelation, healings, and unity of faith in both spiritual and temporal matters as described in the four Gospels and the book of Acts. According to Pratt, Rigdon preached such a message, lacking only apostolic authority. After listening to Rigdon on several occasions, Pratt and many of his associates in that region of Ohio embraced Rigdon’s brand of Reformed Baptist faith. Although it was evident that Rigdon lacked true priesthood authority, Pratt wrote that “we were thankful for even the forms of truth, as none could claim the power, and authority, and gifts of the Holy Ghost—at least so far as we knew.”[3]

With this new affiliation with Rigdon’s congregation, Pratt set out to spread the gospel message. His course led him from Ohio to Newark, New York. He traveled by canal boat. Once in Newark, he felt strongly impressed to disembark and preach in that region. It was dawn when he left the boat and walked about ten miles into the country, where he met a Baptist deacon named Hamblin. Mr. Hamblin had recently acquired a book called the Book of Mormon. Pratt borrowed the book, read all day and night, and became convinced of its truthfulness. He was later baptized by Oliver Cowdery, “an Apostle of the Church of Jesus Christ,” in Seneca Lake.[4]

The Family

While Pratt embraced the Latter-day Saint faith in New York, Sidney Rigdon and his congregation continued their efforts to simulate the first-century Church. In 1830, Rigdon organized his congregation into a communal group known as “the Family.” They were striving to live a cooperative life based upon Rigdon’s perception of the first-century Saints who established an economic order wherein they had all things in common (see Acts 2:44). For as Luke recorded: “Neither was there any among them that lacked: for as many as were possessors of lands or houses sold them, and brought the prices of the things that were sold, and laid them down at the apostles’ feet: and distribution was made unto every man according as he had need” (Acts 4:34–35). Some of Rigdon’s group lived together on the Isaac Morley farm near Kirtland.

The Mission

Late in October, Elder Pratt, together with his missionary companions Oliver Cowdery, Peter Whitmer Jr., and Ziba Peterson, embarked by foot toward Buffalo on the first leg of a missionary journey to teach the Lamanites on the western frontier (see D&C 32:2–3). After introducing the gospel to a group of Native Americans near Buffalo, Pratt convinced his companions to stop at Kirtland and nearby Mentor, Ohio, which would allow the missionaries to introduce the restored gospel to Pratt’s friend and former mentor, Sidney Rigdon.

Rigdon and his followers received the missionaries kindly. The Book of Mormon captivated the community. This interest, coupled with the announcement that apostolic priesthood authority had been restored to the earth through Joseph Smith, led hundreds in the area to investigate the Church seriously. Sidney Rigdon knew he had no legitimate apostolic authority and by mid-November 1830 had requested baptism and the gift of the Holy Ghost at the hands of the Latter-day Saint missionaries. At the time of his baptism, he was also ordained an elder. Within two or three weeks of the conversion of Sidney Rigdon, 127 people had joined the Church in the Kirtland area. Nearly all the converts had been followers of Sidney Rigdon, and many of them had been a part of Rigdon’s “Family” communal experiment. This influx of converts almost doubled Church membership. According to Elder Pratt, investigation continued at a rapid pace, and the number of converts soon rose to a thousand.[5]

Among the initial investigators in Kirtland was Edward Partridge. He was hesitant to be baptized before he met Joseph Smith in person.[6] It would be important to allay his concerns as Partridge would eventually be called to serve as the first bishop of the Church. This position would include the duty of administering the practical day-to-day elements of the law of consecration as it was revealed to Joseph Smith.

A Meeting with Joseph Smith in New York

Shortly after the missionaries left Kirtland for Missouri, Sidney Rigdon and Edward Partridge traveled to Fayette, New York, to meet Joseph Smith in person. As a result of this meeting, Partridge was thoroughly convinced of the truthfulness of the gospel and was baptized by the Prophet in the Seneca River on 11 December 1830.[7] Joseph Smith was duly impressed with Partridge, referring to him as “a pattern of piety, and one of the Lord’s great men.”[8]

In subsequent conversations, Rigdon and Partridge related to the Prophet the success experienced by the missionaries in Kirtland. Given the prominent place of “the Family” experiment in Ohio, it seems reasonable to conclude that Rigdon explained to Joseph Smith his feelings and intentions regarding the communal life and his hopes to recreate the economic order that existed in the first-century Church. It also seems likely that such conversations helped to further prepare the Prophet’s heart and mind for receipt of soon-to-be-disclosed revelations from the Lord regarding His ideal economic and spiritual order. These conclusions receive greater credibility in light of other events and revelations received in December 1830.

A New Scribe—The Prophecy of Enoch—Gathering in Kirtland

Joseph Smith sought the will of the Lord regarding Rigdon and Partridge soon after their arrival. In a revelation received in December 1830, Partridge was commanded to “teach the peaceable things of the kingdom . . . with a loud voice” (D&C 36:2–3). That same month the Lord likened Sidney Rigdon to John the Baptist in that Sidney had served as a forerunner and had prepared the way for greater things to transpire in Kirtland. The Lord called him to be a part of that “greater work” (D&C 35:3).

Specifically, Rigdon was called to serve as a scribe for Joseph Smith, who was working on a translation of the Bible (see D&C 35:20). It is noteworthy that as Rigdon assumed duties as scribe in December 1830, Joseph Smith was considering Genesis 5 and received, by revelation, the prophecy of Enoch (now Moses 7). This prophecy restored a detailed account of how Enoch led God’s followers to become a Zion people.[9] The revealed history implied a spiritual unity as well as an economic unity among the ancient Saints. In the words of Moses, “And the Lord called his people Zion, because they were of one heart and one mind, and dwelt in righteousness; and there was no poor among them” (Moses 7:18). Joseph had been commanded to “seek to bring forth and establish the cause of Zion” as early as April 1829 (D&C 6:6). Without question, his translation of Genesis 5 brought clarity and scope to that command.

Finally, one last revelation was received in December 1830. The Lord commanded Joseph Smith to gather the Saints together in the area of Kirtland, Ohio (see D&C 37). This was the first commandment concerning a gathering since the establishment of the Church.[10] Subsequently, the Lord explained that after the Saints were gathered to Ohio, He would reveal His “law” that the Saints “may know how to govern my church and have all things right before me” (D&C 41:3). That law was the law of consecration (see D&C 42).

An Assessment of “the Family” in Ohio

Apparently “the Family” communal system served as a forerunner to the law of consecration. It raised awareness, attentiveness, and questions that were significant stepping-stones toward the Lord’s everlasting order. As valuable as it was, however, the communal and economic order laid out by Rigdon was incomplete and otherwise flawed. The Saints living this order were well intentioned, but there were at least two glaring problems. First, the communal order was not governed by modern revelation. It was necessary for Peter and his fellow Apostles to govern the communal efforts of the Saints in the first century. A prophet of God would be equally essential in the latter days. Second, “the Family” made no provisions for individual stewardship. Although confiscation was deemed inappropriate by the members of the community, they lacked clearly articulated guidelines designed to maintain rights of personal possession within the group. Therefore, occasions arose when selfishness went unchecked, creating a chaotic environment wherein what belonged to one belonged to all—seemingly without limitations.

An incident in February 1831 between two members of the Church, sixteen-year-old Heman Bassett and twenty-seven-year-old Levi Hancock, who were also part of “the Family” experiment, serves to illustrate this problem. Hancock owned a watch that he was carrying in his pocket. Bassett reached into Hancock’s pocket, took the watch, and walked away. Hancock thought Bassett would return with the watch, but he did not. Rather, Bassett sold the watch and kept the money. When confronted by Hancock about the watch, Bassett responded, “Oh, I thought it was all in the family.” Hancock replied, “I [do] not like such family doing and I would not bear it.”[11]

Possibly, this incident is merely the prank of an unruly teenager (see D&C 52:37) and is not indicative of day-to-day life in the community. As mentioned earlier, however, apparently no constraints or directives existed within “the Family” bylaws to counter such self-serving activities. In the end, the problem was of sufficient magnitude that the Lord later addressed the issue when a more perfect order was revealed through Joseph Smith (see D&C 42:54).

The Practical and Spiritual Need for Consecration

Joseph Smith reacted quickly to the Lord’s directive to move to Ohio. In his own history, he records that he traveled with his wife, Emma, Sidney Rigdon, and Edward Partridge. The party arrived in Kirtland at the first of February 1831.[12] Upon their arrival in Kirtland, the practical need for a “Zion” community like the one described in the restored writings of Moses became increasingly evident to the Prophet. He wrote: “[Members of] the branch of the Church in this part of the Lord’s vineyard . . . were striving to do the will of God, so far as they knew it. . . . The plan of ‘common stock,’ which had existed in what was called ‘the family,’ whose members generally had embraced the everlasting Gospel, was readily abandoned for the more perfect law of the Lord.”[13] Furthermore, a revelation was received by the Prophet on 4 February 1831 that unquestionably served to enhance his anticipation to receive the promised law of the Lord. In that revelation, Edward Partridge was called to serve as the first bishop of the Church with the specific directive to “spend all his time in the labors of the church; to see to all things as it shall be appointed unto him in my laws in the day that I shall give them” (D&C 41:9–10).

To summarize, at least four factors contributed to Joseph Smith’s desire to quickly receive the Lord’s will for the Saints in Kirtland regarding a new spiritual and economic order.[14]

First, as previously mentioned, when Joseph Smith had seen for himself the problems associated with “the Family” communal system, he was highly motivated to establish a more perfect order as revealed by the Lord.

Second, following instructions given in a revelation received on 2 January 1831, Joseph Smith left thirteen acres of land he owned in Harmony, Pennsylvania, to be sold or rented (see D&C 38:37). The land did not sell for two and a half years.[15] Therefore, when Joseph arrived in Kirtland, he and Emma were homeless with few or no resources at their disposal. They lived with the Newel K. Whitney and the Frederick G. Williams families until Joseph was able to build his own home.[16] Furthermore, Edward Partridge had been commanded to “leave his merchandise and spend all his time in the labors of the church” (D&C 41:9). A new economic order could provide a way for these early leaders to subsist.

The third factor involved the pending arrival of approximately two hundred Saints from the three branches of the Church in New York (Colesville, Fayette, and Manchester). A divinely inspired communal order would serve to motivate the Latter-day Saint property owners in Kirtland to consecrate their lands and resources for the general welfare of the otherwise homeless Saints soon to arrive in northeast Ohio.

The fourth, and most important, factor involved a spiritual endowment. In a revelation given on 5 January 1831, the Lord explained: “And inasmuch as my people shall assemble themselves at the Ohio, I have kept in store a blessing such as is not known among the children of men, and it shall be poured forth upon their heads. . . . And he that receiveth these things receiveth me; and they shall be gathered unto me in time and in eternity” (D&C 39:15, 22). Joseph Smith was anxious to supplicate the Lord for these promised blessings. In fact, less than ten days had passed after the Prophet’s arrival in Kirtland when the law of consecration was initially revealed to the Church.

Doctrine and Covenants 42: The Law of the Church

According to Joseph Smith’s own record, “On the 9th of February, 1831, at Kirtland, in the presence of twelve Elders, and according to the promise heretofore made [see D&C 37], the Lord gave the following revelation, embracing the law of the Church.”[17] The Lord’s stated purpose undergirding this promised revelation was to provide directions that the Saints “may know how to govern my church and have all things right before me” (D&C 41:3). In this regard, Doctrine and Covenants 42 contains directives relating to a variety of Church activities such as missionary work (verses 4–9), priesthood ordination and leadership (verse 11), and moral conduct (verse 18–29). Finally, the Lord introduced the law of consecration (verses 30–42, 53–55, 70–73). The two most pressing problems within “the Family” communal system were addressed in this first revelation on consecration. Those problems were a need for direction by prophecy and revelation and the lack of stipulations doe personal possessions within the community.

The ongoing supplications of Joseph Smith beginning late in 1830 and early 1831 solved the first problem. As will be seen later in this article, the second problem was addressed in phases by an infusion of individualism and, eventually, ownership into the communal environment. The Lord explained, “Every man shall be made accountable unto me, a steward over his own property, or that which he has received by consecration” (D&C 42:32). The Lord also explained that “thou shalt not take thy brother’s garment; thou shalt pay for that which thou shalt receive of thy brother” (D&C 42:54).

The introduction of this law changes the tenor of the rest of the Doctrine and Covenants. To this point, the principles of consecration are threaded throughout the text (see D&C 6:6; 14:7; 19:26; 29:11; 35:14; 38:15–22). However, following the introduction of the law in section 42, consecration became a directly stated theme and focal point that was squarely treated and developed in at least twenty-four subsequent revelations.[18] Furthermore, it becomes increasingly evident that the principles of consecration are laced through almost every other revelation received by Joseph Smith and subsequent prophets whose revelations appear in the Doctrine and Covenants—namely Brigham Young, John Taylor, Wilford Woodruff, Joseph F. Smith, and Spencer W. Kimball. Indeed, Hugh Nibley observed that “the main purpose of the Doctrine and Covenants, you will find, is to implement the law of consecration.”[19]

Implementation of the Law of Consecration in Ohio and Missouri: An Overview

The law of consecration is an all-inclusive term pointing us to the law of God’s realm. It includes all spiritual and temporal principles needed to produce a truly Godlike people. The principles that make up this law may be employed in a variety of ways and may be adapted to the needs of the people implementing the law. During different periods of modern Church history, the Lord has revealed to the President of the Church how the law of consecration should be implemented. Generally, the revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants addressing consecration deal with four different systems wherein principles of the law were instituted by the Lord through Joseph Smith. For the purposes of this article, these four systems will be designated as (1) the law of consecration and stewardship; (2) the Literary Firm; (3) the United Firm; and (4) the law of tithing. The following sections will provide an overview of these four systems of consecration, including the sections of the Doctrine and Covenants that specifically address them.

Throughout this overview, it should be remembered that the intent of each of these systems is to assist the Saints in their efforts to conquer and yield up their hearts to God and become a Zion people. By definition, if this spiritual condition exists among the Saints, they will, without compulsion, strive to relieve the poor and establish temporal security for the Church (see Moses 7:18).

The Law of Consecration and Stewardship

The law of consecration and stewardship was introduced in February 1831. The Lord commanded: “If thou lovest me, thou shalt serve me and keep all my commandments; and behold, thou shalt consecrate all thy properties, that which thou hast unto me, with a covenant and deed which can not be broken; and they shall be laid before the bishop of my church, and two of the elders, such as he shall appoint and set apart for that purpose” (Book of Commandments 44:26; emphasis added; compare with D&C 42:29–31). Under this system, all property belonged to God and was to be administered by the bishops of the Church. While an element of individualism was infused into the system through the principle of stewardship, there was no private ownership of property in the earliest stages of this order. All properties were consecrated to and owned by the Church.[20]

The first opportunity to live the law of consecration and stewardship was not extended to previous members of “the Family.” Rather, the opportunity was given to a faithful group of Saints from Colesville, New York, who, in accordance with the commandment of the Lord, moved from New York to Thompson, Ohio, near Kirtland (see D&C 37, 38). They were homeless and bereft of many other basic necessities of life, while the Saints associated with “the Family” were generally settled in the region with means to survive. In fact, some of these Saints were quite wealthy landholders. Remembering the commandment that “thou wilt remember the poor, and consecrate of thy properties for their support that which thou hast to impart unto them, with a covenant and a deed which cannot be broken” (D&C 42:30), the Colesville Saints were well suited to serve as the test case for the law of consecration and stewardship.

In May 1831, the Colesville Saints, led by Newel Knight, began to arrive in the Kirtland area. Bishop Edward Partridge approached Joseph Smith and asked how to organize the group in light of the principles outlined in Doctrine and Covenants 42. In Doctrine and Covenants 51, the Lord commanded Bishop Partridge to organize the Colesville Saints “according to my laws,” appointing to each family an equal stewardship “according to his circumstances and his wants and needs” (D&C 51:3). Furthermore, the Lord explained that it was a great “privilege” to be thus organized according to the laws of the Lord (D&C 51:15).[21] Following these directions, Bishop Partridge approached a recent convert to the Church named Leman Copley. Copley was formerly a Shaker (another Christian sect involved in communal living in Ohio) and one who owned a considerable tract of farmland (759 acres in Thompson).[22] The law of consecration and stewardship was never fully practiced in Ohio. Nevertheless, at the invitation of Bishop Partridge, Copley agreed to enter into an introductory phase of the law of consecration and stewardship with the newly arrived Colesville Saints (see D&C 48:2–3). Soon thereafter, the Colesville Saints moved onto part of the Copley farm and began building cabins and working the land.

In early June 1831, Copley broke his covenant, turned from the faith, and evicted the Colesville Saints from his land. Newell Knight traveled to Kirtland to receive directions from Joseph Smith. The Prophet inquired of the Lord. In the ensuing revelation, the Lord explained that the law of consecration and stewardship among the Colesville Saints had become “void and of none effect” (D&C 54:4). Furthermore, the Lord condemned Leman Copley for breaking his covenant (see D&C 54:5) and commended the Colesville Saints for keeping theirs (see D&C 54:6). Finally, the Colesville Saints were commanded to travel to western Missouri “unto the borders of the Lamanites” (D&C 54:8). This ended the limited practice of the law of consecration and stewardship in Ohio. It was determined that the Ohio Saints were too spread out geographically to make another attempt at that time.[23]

To this point, apparently, this introductory attempt to employ the law of consecration and stewardship had been an acute failure. The Colesville Saints were again homeless and impoverished. However, by employing the principles of the law of consecration, they had successfully moved from New York to Ohio and on to Jackson County, Missouri, where the prospects for land acquisition were much better than in Ohio. Even more important, however, is what happened to the people. Parley P. Pratt was serving a mission to the western states in the late summer of 1831 and spent time with these Saints in Jackson County through the fall and winter. His description of these Saints makes it clear that their hearts were in the process of being given over to God. He wrote:

This Colesville branch was among the first organized by Joseph Smith, and constituted the first settlers of the members of the Church in Missouri. They had arrived late in the summer, and cut some hay for their cattle, sowed a little grain, and prepared some ground for cultivation, and were engaged during the fall and winter in building log cabins, etc. The winter was cold, and for some time about ten families lived in one log cabin, which was open and unfinished, while the frozen ground served for a floor. Our food consisted of beef and a little bread made of corn, which had been grated into coarse meal by rubbing the ears on a grater. This was rather an inconvenient way of living for a sick person; but it was for the gospel’s sake, and all were very cheerful and happy.

We enjoyed many happy seasons in our prayer and other meetings, and the Spirit of the Lord was poured out upon us, and even on the little children, insomuch that many of eight, ten or twelve years of age spake, and prayed, and prophesied in our meetings and in our family worship. There was a spirit of peace and union, and love and good will manifested in this little Church in the wilderness, the memory of which will be ever dear to my heart.[24]

This description is indicative of the stated intent of consecration. On one hand, people were fed, clothed, and provided for. Even more importantly, they were kind, gentle, submissive and willing to bear the burdens of one another, and they seemed to be of one heart. In fact, the ever-faithful dispositions of the Colesville Saints made it possible for Joseph Smith to seal them up to eternal life during a visit to Missouri in 1832.[25]

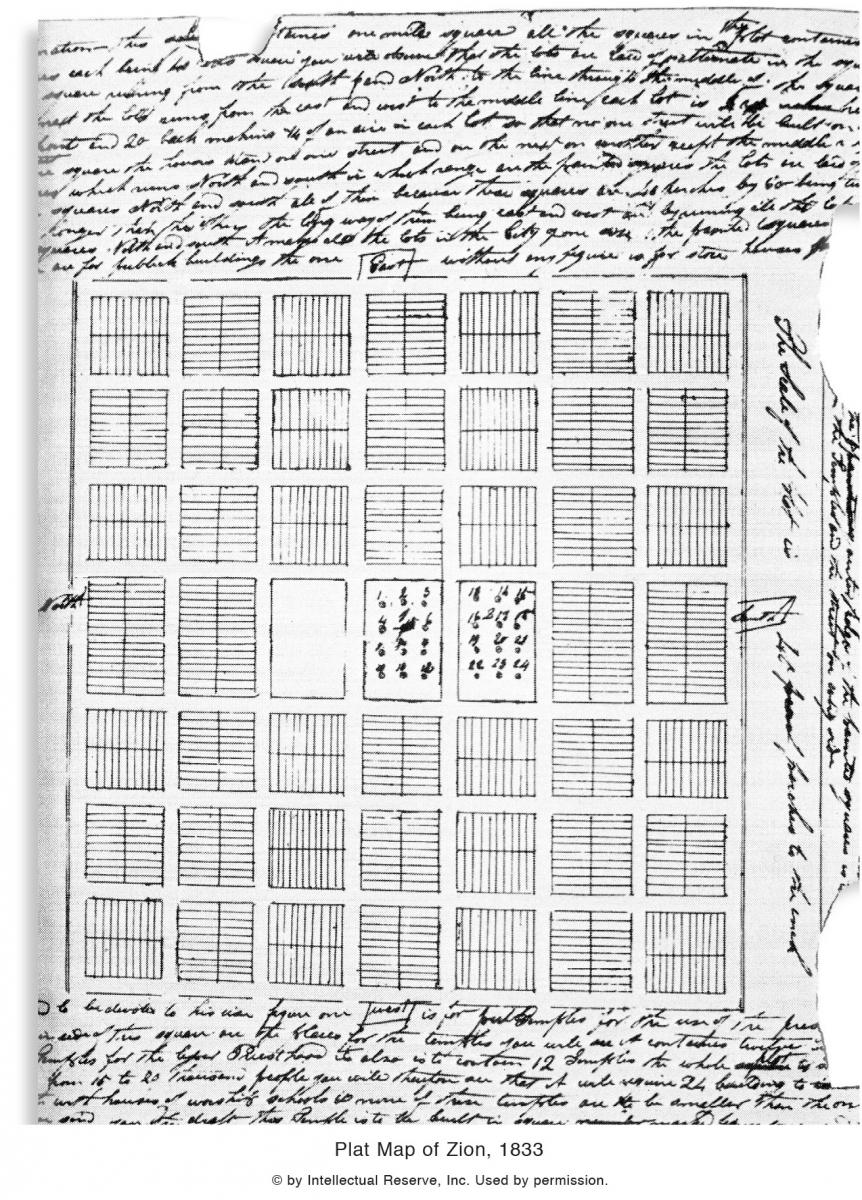

The Location of the City of Zion

On 20 July 1831, Joseph Smith received a much-anticipated revelation wherein Jackson County was identified “as the place for the city of Zion” (D&C 57:2). The Saints began to gather to Missouri. Only those who were willing to live the law of consecration and stewardship could join the Saints in Jackson County.[26] In 1833, a man named Bates withdrew from the order and sued Bishop Edward Partridge, demanding that the land he had consecrated to the Church be returned. Even though binding contracts had been drawn, the frontier court ruled in favor of Bates. His land was returned.[27] As a result of this case, Church leaders determined that private ownership rights must be included in the process of consecrating properties and receiving a stewardship. Simply, the participant would consecrate all properties to the bishop of the Church. The bishop would then deed back to the steward properties, farm implements, and resources in sufficient measure according to needs and wants. The deed was legally binding, and the steward obtained ownership of the respective allocation.[28]

By the summer of 1833, about a thousand Saints were living in Jackson County. Parley P. Pratt noted that a Zion community was being forged because of the goodness of the Saints; therefore, the general practice of the law of consecration and stewardship was succeeding. He wrote that the Saints “lived in peace and quiet; no lawsuits with each other or with the world; few or no debts were contracted; few promises broken; there were no thieves, robbers, or murderers; few or no idlers; all seemed to worship God with a ready heart. On Sundays the people assembled to preach, pray, sing, and receive the ordinances of God. Other days all seemed busy in the various pursuits of industry. In short, there has seldom, if ever, been a happier people upon the earth than the Church of the Saints now were.”[29]

Unfortunately, these idyllic conditions did not persist. Selfishness and corruption crept in among some of the Saints, and internal strife ensued. Some members refused to acknowledge the directions of Church leaders in Missouri. Others made attempts to create their own “stewardship” independently of Bishop Partridge.[30] William W. Phelps requested that Joseph Smith come to Jackson County from Kirtland to mediate the downward spiritual spiral then occurring amidst the Missouri Saints. Orson Hyde and Hyrum Smith were appointed to respond to this request. They wrote: “We want to see a spirit in Zion, by which the Lord will build it up; that is the plain, solemn, and pure spirit of Christ. Brother Phelps requested in his last letter that Brother Joseph should come to Zion; but we say that Brother Joseph will not settle in Zion until she repent, and purify herself, and abide by the new covenant, and remember the commandments that have been given her, to do them as well as say them.”[31]

Problems were compounded because of fears among Missourians that the “Mormons” would gain political control of the region, and such fears sparked hostile persecution against the Saints.[32] They were driven from their homes and lands in Jackson County in the final months of 1833. Scattered and destitute, the needs of the Missouri Saints far outweighed their ability to consecrate properties sufficient to raise the standard of living for the entire group. Discouragement accompanied their impoverished and scattered circumstances. In their attempts to accumulate the very essentials of life, their drive to consecrate what little they had diminished markedly.

The Lord rebuked the Saints in a revelation given 16 December 1833. He explained, “I, the Lord, have suffered the affliction to come upon them, wherewith they have been afflicted, in consequence of their transgressions; yet I will own them, and they shall be mine in that day when I shall come to make up my jewels” (D&C 101:2–3). On 22 June 1834, Joseph Smith received a revelation as he led Zion’s Camp (a group of about two hundred men who were traveling from Kirtland to Jackson County, Missouri, to reclaim the consecrated lands of the Saints). In this revelation, the Lord chastened the Saints for failing to “impart of their substance, as becometh saints, to the poor and afflicted among them; and are not united according to the union required by the law of the celestial kingdom; and Zion cannot be built up unless it is by the principles of the law of the celestial kingdom; otherwise I cannot receive her unto myself” (D&C 105:3–5). He further explained that the Missouri Saints would live the law of consecration fully after Zion had been redeemed (see D&C 105:34). Therefore, while the Saints were expected to continue to live their lives according to the principles of the law of consecration (see D&C 105:29), this period of severe persecution, poverty, scattering, and sickness brought to a close the general and communal nature of the order.[33] Interestingly, participants in the law of consecration and stewardship enjoyed the most blissful of circumstances and the most bitter. Apparently, the determining factor between joy and pain in this regard was the condition of the hearts of the people who were participating.

The Literary Firm

The law of consecration and stewardship was predominately an agrarian enterprise. However, other interests of the Church required different and varied talents that were not agrarian in nature. For example, as the Book of Commandments was being prepared for printing in the latter months of 1831, the Lord called six men—Joseph Smith, Martin Harris, Oliver Cowdery, John Whitmer, Sidney Rigdon, and W. W. Phelps—to consecrate their time, talents, and money to the endeavor of printing and selling scriptures and other publications produced by the Church (see D&C 70:1; 57:11–12). These men constituted the original members of the Literary Firm. Later, Jesse Gause was added as a member. When he was excommunicated from the Church, Frederick G. Williams was appointed to take his place. In both cases, appointment to the enterprise was connected with their callings to serve in the First Presidency (see D&C 81; 90; 92). There were never more than eight members of the Literary Firm.[34]

Specifically, their stewardship involved a business venture geared to sell and distribute the printed word of God, such as the Book of Mormon and the Book of Commandments, “unto the ends of the earth” (D&C 72:21; see also D&C 70:6). A high priority was also placed upon printing the Book of Commandments, the Book of Mormon, the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible, a hymnal, Church newspapers, children’s literature, and a Church almanac.[35] The most significant publications produced and sold by the Literary Firm included the first edition of the Doctrine and Covenants, the second edition of the Book of Mormon, the first Latter-day Saint hymnal, and newspapers such as the Evening and Morning Star and the Latter-day Saints’ Messenger and Advocats.

The Lord stipulated that seed money for the Literary Firm could be acquired from the bishop of the Church (see D&C 72:20). Eventually, however, the venture was to be self-sustaining, and the members of the firm would receive their livelihood from the proceeds of the business. Any surplus would be turned back to the bishop for the purpose of relieving the poor and building up Zion (see D&C 70:5–9).

Because the Literary Firm weathered many difficult times (including the destruction of its printing press in 1833), the business began to decline in the first half of 1836. The final printing conducted by the Literary Firm was the Elders’ Journal in July, and by August 1838, the organization and efforts of the Literary Firm were brought to a close.

The Literary Firm was remarkable in that it served as the medium through which an entirely new book of scripture was introduced to the world, the Doctrine and Covenants. This book is so singular that Joseph Smith referred to it as “the foundation of the Church in these last days, and a benefit to the world, showing that the days of the mysteries of the kingdom of our Savior are again entrusted to man.”[36] If fruitfulness in both cooperation and output are the measures of success, the Literary Firm served its purpose well for several years.

The United Firm

The Literary Firm had a sister business organization known as the United Firm (later known as the United Order[37]). The United Firm was organized by revelation in March 1832, just a few months after the organization of the Literary Firm. Participants in the United Firm consisted of a small number of Church leaders and never exceeded twelve persons.[38] In a revelation to Joseph Smith, the Lord commanded that “the time has come, and is now at hand; that there be an organization of my people in regulating and establishing the affairs of the storehouse for the poor of my people, both in this place [Kirtland] and in the land of Zion [Jackson County]—for a permanent and everlasting establishment and order unto my church, to advance the cause, which ye have espoused, to the salvation of man, and to the glory of your Father who is in heaven; that you may be equal in the bonds of heavenly things, yea, and earthly things also, for the obtaining of heavenly things. For if you are not equal in earthly things ye cannot be equal in obtaining heavenly things” (D&C 78:3–6).

A driving principle behind the United Firm was the hope “that the church may stand independent above all other creatures beneath the celestial world” (D&C 78:14). The original members of the United Firm were Joseph Smith, Newel K. Whitney, and Sidney Rigdon (see D&C 78:9). The private enterprises undertaken by members of the United Firm were intended to provide a livelihood for its participants and furnish a surplus that could infuse greater stability into the agrarian-based law of consecration and stewardship and the business-centered efforts of the Literary Firm.

As prescribed by revelation, the United Firm was to conduct business ventures in Kirtland, Ohio, and Jackson County, Missouri (see D&C 78). The firm functioned primarily through two business fronts: Gilbert, Whitney, and Company in Missouri and Newel K. Whitney and Company in Kirtland. The Missouri and Ohio companies each operated a store—one in Independence, the other in Kirtland. Large sums of money were secured from New York banks to stock the stores, buy additional land, and purchase farm equipment. Furthermore, the firm operated a tannery, brickyard, and ashery.[39]

Within one year, the joint Ohio-Missouri enterprise was in financial straits. Legal fees from a lawsuit, travel expenses, and the July 1833 destruction of the printing press and the dismantling of the Gilbert and Whitney Company store in Jackson County led to a severe financial shortfall. The United Firm was on the verge of collapsing.

In response to these conditions, Joseph Smith, Newel K. Whitney, Frederick G. Williams, Oliver Cowdery, and Heber C. Kimball met in Kirtland on 7 April 1834. They united in prayer and begged the Lord to “deliver the Firm from debt, that they might be set at liberty.”[40] A petition was made by Joseph Smith to the Saints in general to come to the aid of the United Firm “for Zion’s sake.”[41] In a letter to Orson Pratt, he warned, “Now, Brother Orson, if this Church, which is essaying to be the Church of Christ will not help us, when they can do it without sacrifice, with those blessings which God has bestowed upon them, I prophesy—I speak the truth, I lie not—God shall take away their talent, and give it to those who have no talent, and shall prevent them from ever obtaining a place of refuge, or an inheritance upon the land of Zion.”[42]

The Saints failed to supply the needed capital and aid to save the United Firm. Therefore, on 10 April 1834, Joseph Smith met with the Kirtland members of the enterprise and dissolved the order.[43] On 23 April 1834, the Lord revealed, “Therefore, you are dissolved as a united order with your brethren [in Missouri]” (D&C 104:53). By revelation, Joseph Smith distributed the remaining assets of the United Firm among those who had been participants (see D&C 104:20–59). Since the Missouri members of the order had lost their properties at the hands of mobs, there were no resources to reallocate; therefore, no mention is made of them in his regard.

In conclusion, the private undertakings of the United Firm maintained the values and principles so essential to creating a Zion people whose hearts belong to God. Again, the focus was on what they were becoming—not what they were accumulating. The Lord explained: “And all this for the benefit of the church of the living God, that every man may improve upon his talent, that every man may gain other talents, yea, even an hundred fold, to be cast into the Lord’s storehouse, to become the common property of the whole church—every man seeking the interest of his neighbor, and doing all things with an eye single to the glory of God. This order I have appointed to be an everlasting order unto you, and unto your successors, inasmuch as you sin not” (D&C 82:18–20). Unfortunately, one of the reasons the United Firm was dissolved arose because the Saints failed to live by the principles of the law of consecration, which would have moved them to seek the interests of their neighbors as commanded in the revelations.

The Law of Tithing

The mid-1830s brought a season of acute financial shortfall for the Saints. In the wake of this shortfall, Joseph Smith determined to move Church headquarters from Kirtland, Ohio, to Far West, Missouri. Unfortunately, the Prophet was too impoverished to be able to make the trip to Missouri. In fact, he was so poor that he had sought for work cutting and sawing wood so he could feed himself and his family.[44]

At this point, as with other junctures in this history, it may seem that the efforts of consecration among the Saints in Ohio and Missouri were a complete failure. However, the way Joseph Smith obtained passage to Far West serves as another example that the principles of consecration were working in the hearts of many Saints.

Joseph Smith approached Brigham Young and said, “You are one of the Twelve who have charge of the kingdom in all the world; I believe I shall throw myself upon you, and look to you for counsel in this case [getting to Far West, Missouri].” Brigham Young then uttered a bold prophecy. He said, “If you will take my counsel it will be that you rest yourself, and be assured you shall have money in plenty to pursue your journey.”

With the charge to get Joseph Smith to Missouri on his mind, Brigham Young was approached by a Saint named Tomlinson who had been trying to sell his farm without success. Tomlinson asked Brigham Young for advice. Brigham Young said that “if he would do right, and obey counsel, he should have an opportunity to sell.” Three days later, an offer was made on the property. When Tomlinson reported this to Brigham Young, Tomlinson was told that “this was the manifestation of the hand of the Lord to deliver Joseph Smith from his present necessities.” Brother Tomlinson was strictly obedient and quickly provided the Prophet with $300, allowing Joseph to make the journey to Far West.[45]

Once in Far West, the Prophet continued to cope with the abject poverty of the Church. He asked Bishop Partridge and his counselors to submit recommendations for the purpose of raising liquid capital to meet the working needs of the Church. They suggested an annual tithe of two percent on all families in the Church with the exception of widows and families whose assets totaled less than $75.[46]

This recommendation apparently served as a forerunner to the law of tithing revealed just over six months later in the summer of 1838.[47] On 8 July 1838, the Lord revealed the following to Joseph Smith: “Verily, thus saith the Lord, I require all their surplus property to be put into the hands of the bishop . . . for the building of mine house and for the laying of the foundation of Zion . . . and for the debts of the Presidency of my Church. And this shall be the beginning of the tithing of my people. And after that, those who have thus been tithed shall pay one-tenth of all their interest annually; and this shall be for a standing law unto them forever . . . [and] all those who gather unto the land of Zion shall be tithed of their surplus properties, and shall observe this law, or they shall not be found worthy to abide among you” (D&C 119:1–5).

The law of tithing is part of the law of consecration. Under this law, stewards still consecrated all of their goods to the bishop for the building up of Zion (see D&C 119:1–2). In addition to this consecration, a tithe was paid on the surplus of each steward. This tithe was to be paid annually (see D&C 119:4). Simply, the essence of the law of tithing is to support the poor and provide for the maintenance of the Church. And, most importantly, as Elder Jeffrey R. Holland taught, the consistent payment of a full tithe serves “as a declaration that possession of material goods and the accumulation of worldly wealth are not the uppermost goals of your existence.”[48]

Shortly after the implementation of the law of tithing, the Saints were driven from Missouri. Under the principles of the law of consecration, the Saints were able to take their impoverished numbers to a new state and new home. As the Saints were being evicted from Missouri, the Prophet Joseph Smith wrote a letter from Liberty Jail wherein he defined consecration under the law of tithing. He explained: “Now for a man to consecrate his property, wife and children, to the Lord, is nothing more nor less than to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, visit the widow and fatherless, the sick and afflicted, and do all he can to administer to their relief in their afflictions, and for him and his house to serve the Lord. In order to do this, he and all his house must be virtuous, and must shun the very appearance of evil.” [49] As with the other forms of consecration, the focus of the law of tithing is the condition of the heart. In Nauvoo, while the Saints crossed the plains, and later in Utah, the principles of consecration were employed in a variety of ways under the direction of the President of the Church. Nevertheless, the law of tithing was the final phase of consecration introduced during the Ohio and Missouri periods of Church history.

Consecration Today

From 1831 to 1838, four mediums existed through which the principles of the law of consecration were implemented. In each case, the methods of consecration were overseen by the President of the Church. According to the Doctrine and Covenants, the purpose of consecration was to train Latter-day Saints to yield up their hearts to God, provide for the poor, and sustain the operations of the Church. Consecration in Ohio and Missouri shaped members of the Church in ways that are still perceptible today. Their successes and failures beg the question today, “Could we do it if called upon?”

Interestingly, the law of consecration has never been rescinded. Quite the opposite, mature and faithful Latter-day Saints are expected to consecrate. In large measure, this is done today through a series of personal covenants, tithes of temporal assets, and offerings of time and talents. Additionally, Elder Bruce R. McConkie taught that the day must come wherein a more structured format of consecration will be reintroduced to the Church.[50] In the meantime, practicing the principles of this celestial law in our personal lives will ultimately result in celestial blessings. In this regard, then Presiding Bishop Robert D. Hales explained that “this promised Zion always seems a little beyond our reach. We need to understand that as much virtue can be gained in progressing toward Zion as in dwelling there. It is a process as well as a destination. We approach or withdraw from Zion through the manner in which we conduct our daily dealings, how we live within our families, whether we pay an honest tithe and generous fast offering, how we seize opportunities to serve and do so diligently. Many are perfected upon the road to Zion

Notes

[1] Orson F. Whitney, The Life of Heber C. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1945), 65–66.

[2] Neal A. Maxwell, “Consecrate Thy Performance,” Ensign, May 2002, 36.

[3] Parley P. Pratt, Autobiography (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1985), 14.

[4] Pratt, Autobiography, 27.

[5] Pratt, Autobiography, 36; see also Church History in the Fulness of Times (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2000), 82.

[6] Pratt, Autobiography, 36; see also Lucy Mack Smith, The Revised and Enhanced History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, ed. Scot Facer Proctor and Maurine Jensen Proctor (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1996), 249–50.

[7] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2d ed., rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1948), 1:129; hereafter cited as HC.

[8] See heading of Doctrine and Covenants 36.

[9] HC, 1:132.

[10] See heading of Doctrine and Covenants 37.

[11] Levi Hancock Journal, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University), 28.

[12] HC, 1:145–46.

[13] HC, 1:146–47.

[14] These four factors are an adaptation of a similar listing found in Leonard J. Arrington, Feramorz Y. Fox, and Dean L. May, Building the City of God: Community and Cooperation Among the Mormons (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 19–20.

[15] Larry C. Porter, “‘Ye Shall Go to the Ohio’: Exodus of the New York Saints to Ohio, 1831,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: Ohio, ed. Milton V. Backman Jr. (Provo, Utah: Department of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University, 1990), 3.

[16] Porter, “Ye Shall Go to the Ohio,” 1–5.

[17] HC, 1:148.

[18] See William O. Nelson, “To Prepare a People,” Ensign, January 1979, 23. See also Church History in the Fulness of Times, 98.

[19] Hugh Nibley, Approaching Zion, ed. Don E. Norton (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989), 174.

[20] Lyndon W. Cook, Joseph Smith and the Law of Consecration (Orem, Utah: Keepsake, 1991), 8.

[21] HC, 1:173. Of interest here is the fact that Parley P. Pratt was present with the Prophet when Joseph received the revelation known as Doctrine and Covenants 51. Parley provides a detailed account of the manner in which Joseph Smith received revelations (see Pratt, Autobiography, 65–66).

[22] Larry C. Porter, “The Colesville Branch in Kaw Township, Jackson County, Missouri, 1831 to 1833,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint History: Missouri, ed. Arnold K. Garr and Clark V. Johnson (Provo, Utah: Department of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University, 1994), 281.

[23] Cook, Joseph Smith and the Law of Consecration, 16.

[24] Autobiography, 56.

[25] Dean Jessee, “Joseph Knight’s Recollection of Early Mormon History,” BYU Studies 17, no. 1 (autumn 1976): 39.

[26] Cook, Joseph Smith and the Law of Consecration, 16.

[27] Cook, Joseph Smith and the Law of Consecration, 20–21.

[28] In Daniel H. Ludlow, ed., Encyclopedia of Mormonism (New York: Macmillan, 1992), s.v. “Consecration in Ohio and Missouri.” See also Cook, Joseph Smith and the Law of Consecration, 29–30.

[29] Pratt, Autobiography, 75.

[30] Pratt, Autobiography, 128.

[31] HC, 1:319.

[32] Pratt, Autobiography, 78.

[33] Cook, Joseph Smith and the Law of Consecration, 36–37.

[34] In Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, s.v. “Consecration in Ohio and Missouri.”

[35] Cook, Joseph Smith and the Law of Consecration, 44.

[36] See heading of Doctrine and Covenants 70; see also Joseph Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, comp. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1958), 7–8.

[37] Cook explains that in the second edition of the Doctrine and Covenants printed in 1835, the word “Firm” was replaced with the word “Order.” It was believed that the word “Order” would sound more like a religious fraternity and less like a business. Therefore, the word “Firm” was replaced in each instance in sections 78, 82, 92, 96, and 104 (see Cook, Joseph Smith and the Law of Consecration, 65, 67).

[38] Cook, Joseph Smith and the Law of Consecration, 57, 66. The names of the twelve participants are Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, Oliver Cowdery, Newel K. Whitney, Edward Partridge, A. Sidney Gilbert, John Whitmer, William W. Phelps, Frederick G. Williams, John Johnson, Martin Harris, and Jesse Gause (whose name was deleted from the order when he left the Church). See also Arrington, Fox, and May, Building the City of God, 31; see Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, s.v. “Consecration in Ohio and Missouri.”

[39] Cook, Joseph Smith and the Law of Consecration, 60.

[40] HC, 2:47.

[41] HC, 2:48.

[42] HC, 2:48.

[43] HC, 2:49.

[44] HC, 3:2.

[45] HC, 3:2.

[46] Donald Q. Cannon and Lyndon W. Cook, ed., Far West Record (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 128–30; see Cook, Joseph Smith and the Law of Consecration, 75–77.

[47] See Cook, Joseph Smith and the Law of Consecration, 77.

[48] Jeffrey R. Holland, in Conference Report, October 2001, 40; or Ensign, November 2001, 34.

[49] HC, 3:231; see also Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, 127.

[50] Bruce R. McConkie, Mormon Doctrine, 2d ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1966), 158.