Paul and James on Faith and Works

Mark D. Ellison

Mark D. Ellison, "Paul and James on Faith and Works," Religious Educator 13, no. 3 (2012): 147–171.

Mark D. Ellison (EllisonMD@ldschurch.org) was a writer for Curriculum Services, Seminaries and Institutes, Salt Lake City Central Office when this article was published.

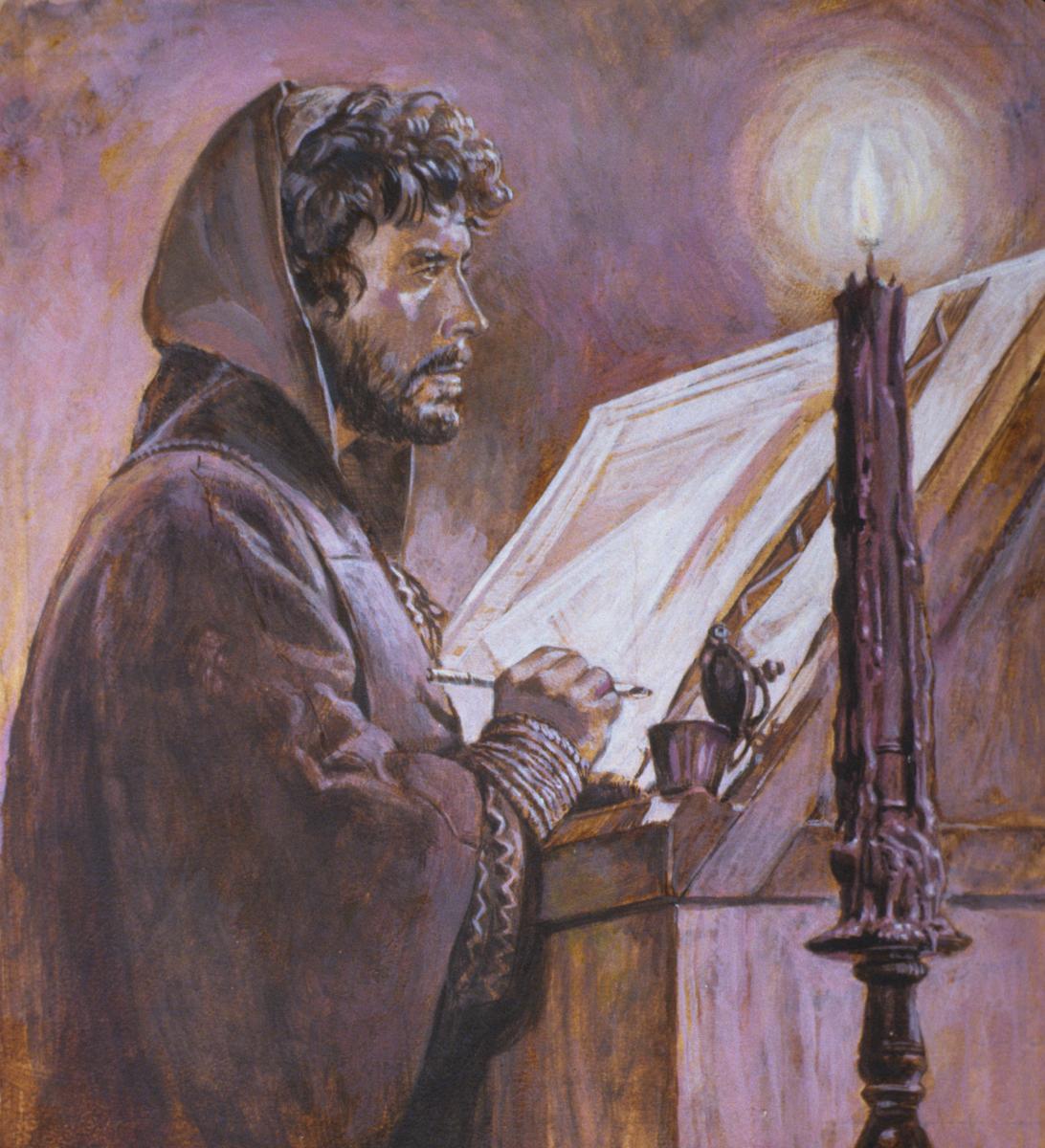

In reading Paul and James it may seem like they contradict each other on faith versus works and what saves us. We come to understand that they actually profess the same thing. © 1984 Robert Barrett.

In reading Paul and James it may seem like they contradict each other on faith versus works and what saves us. We come to understand that they actually profess the same thing. © 1984 Robert Barrett.

An Apparent Problem

Students of the New Testament will confront an apparent contradiction between the teachings of Paul and James on the subject of faith and works. Perhaps it is best represented in the following passages. [1] In his epistle to the Galatians, Paul wrote:

Knowing that a man is not justified by the works of the law, but by the faith of Jesus Christ, even we have believed in Jesus Christ, that we might be justified by the faith of Christ, and not by the works of the law: for by the works of the law shall no flesh be justified....

Even as Abraham believed God, and it was accounted to him for righteousness.

Know ye therefore that they which are of faith, the same are the children of Abraham. (Galatians 2:16; 3:6–7)

Paul made very similar statements in his epistle to the Romans (see Romans 3:28; 4:1–3). James, however, stated:

But wilt thou know, O vain man, that faith without works is dead?

Was not Abraham our father justified by works, when he had offered Isaac his son upon the altar?...

And the scripture was fulfilled which saith, Abraham believed God, and it was imputed unto him for righteousness....

Ye see then how that by works a man is justified, and not by faith only. (James 2:20–21, 23–24)

Without yet defining their terms, we notice that in these passages, both Paul and James used the terms faith, works, and justified. [2] Both Paul and James appealed to Abraham as an example of one who was justified. Both quoted from the same scripture, Genesis 15:6, which says that Abraham “believed in the Lord; and he counted it to him for righteousness [or justification].” [3] But Paul said that justification comes “by the faith of Christ, and not by the works of the law” (Galatians 2:16) while James said that “by works a man is justified, and not by faith only” (James 2:24).

Over the course of Christian history, some individuals, having seen no way that both Paul and James could be right, have concluded that they disagreed with each other. Theological disputes have persisted between Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox Christians over the question of whether man is justified by faith or works, pitting Paul and James against each other in the process. [4]

We who teach in the Church have often responded by expounding a balanced view of the roles of faith and works in salvation, appealing to a broad spectrum of scriptural teaching and prophetic commentary but without adequately clarifying the specific passages that seem to contradict each other. [5] Though this approach does help our students understand and appreciate correct doctrine, it can leave them confused still about what Paul and James meant and why they wrote what they did.

If we simply explain doctrine without clarifying these passages, we miss an opportunity to help our students connect with the scriptures and develop greater confidence in them. Our students might find these passages troubling. How is it that two Apostles [6] of the Lord Jesus Christ could apparently disagree so completely about a doctrine as fundamental as how people may be justified?

The Actual Problem

My purpose in this paper is to deal with these problematic verses while avoiding the historical errors of pitting James against Paul or simplistically dichotomizing faith and works. I hope instead to demonstrate that those ways of characterizing the problem are without foundation, scripturally or doctrinally. Though there certainly were disputes among the Savior’s early disciples (see Galatians 2:11–14; 3 John 1:9–10; D&C 64:8), in this case the scriptural record supports another explanation for the seeming disagreement between James and Paul. That “disagreement” exists primarily because some have failed to read the scriptures in context. As we come to understand what these passages by Paul and James actually mean in context, we see that the supposed contradiction between them is no contradiction after all. These two Apostles in fact taught a harmonious view of the gospel of Jesus Christ, albeit to different audiences with different circumstances.

Much of the difficulty in understanding Paul and James stems from asking the wrong questions. The Prophet Joseph Smith said, “If we start right, it is easy to go right all the time; but if we start wrong we may go wrong, and it will be a hard matter to get right.” [7] This principle can apply to understanding the scriptures. We start right by approaching the scriptures with the right questions. [8] When it comes to understanding Paul and James, the question is not, “Which one was right—Paul or James?” or “Which one saves us—faith or works?” These questions are wrong from the start because they contain flawed assumptions. Perhaps more productive questions would be “What circumstances might have led both Paul and James to write about faith and works, using the example of Abraham and appealing to Genesis 15:6?,” “What exactly did Paul and James mean by the terms faith and works?,” and “How does understanding these terms in context clarify the doctrines Paul and James taught?”

We cannot safely assume that just because a term has a certain meaning in one place in the scriptures, it necessarily carries that exact same meaning every other place it appears. For example, the Bible Dictionary informs us that in the New Testament, the word Apostle sometimes refers to the twelve men Jesus chose and ordained during his mortal ministry, but it also applies to others like Paul, James, and Barnabas: “The New Testament does not inform us whether these three brethren also served in the council of the Twelve as vacancies occurred therein, or whether they were apostles strictly in the sense of being special witnesses for the Lord Jesus Christ” (Bible Dictionary, “Apostle,” 612). Similarly, in Doctrine and Covenants 25, the Lord told Emma Smith that she would be “ordained” under the hand of Joseph Smith (D&C 25:7). A footnote explains that in this instance, “ordained” simply means “set apart” (v. 7 footnote a), not having the authority of a priesthood office bestowed.

Terms like Apostle and ordain, like faith and works, can have more than one meaning or application. Therefore, we should ask, “When Paul spoke of faith and works, what exactly did he mean?” and “When James used those terms, what did he mean?” When we explore these questions, we find that Paul and James did indeed use the terms faith and works in different ways and in different settings. Recognizing this resolves much of the apparent discrepancy between them.

Understanding Paul’s Use of Faith and Works in Galatians

Paul wrote to the Galatians in response to a doctrinal and ecclesiastical controversy created by Judaizers—Jewish-Christians who were teaching Gentile members of the Church the false doctrine that in order to be saved, they must be circumcised and observe the ritual requirements of the law of Moses. [9]

The book of Acts refers to similar teachers, providing helpful historical background about what apparently was not an isolated controversy. Prior to the events recorded in Acts10, probably most, if not all, members of the Church were Jewish. Either they were Jews by birth, or they were proselytes—Gentiles who had converted to Judaism by being circumcised and committing to live the law of Moses. [10] But in Acts 10, Peter, the senior Apostle, received a revelation that Gentiles who had faith in God and followed his teachings were “accepted with him” (Acts 10:35) and were to be received into the Church by baptism, without first having to convert to Judaism by undergoing the rite of circumcision (see Acts 10:43–48). Peter then taught and baptized Cornelius, “probably the first gentile to come into the Church not having previously become a proselyte to Judaism” (Bible Dictionary, “Cornelius,” 650).

Following these events, a controversy caused by Judaizers arises in Acts 15:

And certain men which came down [to Syrian Antioch] from Judaea taught the brethren, and said, Except ye be circumcised after the manner of Moses, ye cannot be saved. When therefore Paul and Barnabas had no small dissension and disputation with them, they determined that Paul and Barnabas, and certain other of them, should go up to Jerusalem unto the apostles and elders about this question. (Acts 15:1–2)

The council of Apostles and elders that met in Jerusalem rejected the teaching of the Judaizers and affirmed that Gentile members of the Church did not need to be circumcised or observe other rituals of the law of Moses (see Acts 15:24–29). The Apostles and elders did call upon Gentile Saints to live moral teachings of the law, specifically to avoid idolatry and sexual sin (see Acts 15:28–29). They also counseled Gentile Saints to observe some kosher dietary restrictions, apparently not as a requirement for salvation but to avoid offending the Jewish communities where they lived and thus potentially hindering missionary work in those communities. [11]

Whether Paul wrote his epistle to the Galatians shortly before or sometime after this council in Jerusalem is a question that is still debated. [12] In either case, the account in Acts attests to the disputes that were occurring in the mid–first century over the question of how Gentile converts were to be received into the Church and what their obligation was to the law of Moses. This is the very problem that Paul addressed in Galatians.

In Galatia, Paul had preached the gospel, established branches of the Church, and then departed to spread the gospel in other locations. [13] Sometime later, he received word that the Saints in Galatia were quickly beginning to embrace a different gospel message taught by people who were perverting the gospel of Christ (see Galatians 1:6–7). From the content of the epistle, it is clear that this “other gospel” (v. 8) was the teaching of Judaizers like the people described in Acts 15 (see Galatians 5:1–8; 6:12–15). “They constrain you to be circumcised,” Paul wrote (Galatians 6:12). They had also convinced the Galatians that they needed to observe the Jewish Sabbath, Jewish feasts, and the Jewish calendar: “Ye observe days, and months, and times, and years,” Paul noted, adding, “I am afraid [for] you, lest I have bestowed upon you labour in vain.” Paul continued, “If ye be circumcised, Christ shall profit you nothing” (Galatians 4:10–11; 5:2). [14]

Paul understood that in this crisis, the Galatian Saints were at risk of losing eternal blessings. Why was it so serious a matter for these Gentile converts to be circumcised and start observing the law of Moses? Paul explained: “For as many as are of the works of the law are under the curse: for it is written [in Deuteronomy 27:26], Cursed is every one that continueth not in all things which are written in the book of the law to do them” (Galatians 3:10; emphasis added). That is, when a person underwent circumcision and signaled his intention to live by the law of Moses, he obligated himself to keep the entire law—all its rituals, all its prescribed sacrifices, all its dietary regulations, all 248 commandments and 365 prohibitions given in the Torah and taught by the rabbis. [15]

Failure to keep just one commandment was failure to keep the whole law (see Galatians 5:3), and no one successfully kept them all: “That no man is justified by the law in the sight of God, it is evident: for, The just shall live by faith,” Paul wrote (Galatians 3:11). By the strict teaching of the law itself, everyone was accursed: “The scripture hath concluded all under sin” (Galatians 3:22; see also Romans 3:9–20, 23). Therefore, for Gentile Christians, choosing to be circumcised amounted to deliberately placing oneself “under the curse” (Galatians 3:10) or “under sin” (Galatians 3:22).

Paul taught that the way God had provided for people to become free from the curse of sin was through the Atonement of Jesus Christ: “Christ hath redeemed us from the curse of the law, being made a curse for us: for it is written, Cursed is every one that hangeth on a tree: that the blessing of Abraham might come on the Gentiles through Jesus Christ; that we might receive the promise of the Spirit through faith” (Galatians 3:13–14; see also 2Corinthians 5:21). The Atonement of Christ was central in Paul’s thinking. He argued that Gentile Christians who were choosing to be circumcised were in effect saying that Christ’s suffering had no saving effect: “For if righteousness come by the law, then Christ is dead in vain” (Galatians 2:21). Essentially, the law was given to lead to Christ (see Galatians 3:24–25) and not vice versa. Righteousness, or justification—being “pardoned from punishment for sin and declared guiltless” [16]—came not by the law, but by Christ.

It was in this context that Paul wrote to the Galatians about faith and works. His main point is found in Galatians 2:16 (the passage cited above that appears to be contradicted by James). Notice that in this verse, Paul used the term works three times, but never once by itself. Each time it was part of the phrase “the works of the law” [ergōn nomou]: “A man is not justified by the works of the law, but by the faith of Jesus Christ, . . . we have believed in Jesus Christ, that we might be justified by the faith of Christ, and not by the works of the law: for by the works of the law shall no flesh be justified” (Galatians 2:16; emphasis added). Throughout Paul’s discussion of faith and works in Galatians, every time he used the term works [ergōn], he consistently used it as a part of the phrase “the works of the law.” [17]

In this context, it is evident that Paul used the term works with particular reference to circumcision and the other distinctively Jewish observances of the Mosaic law, such as the Sabbath and feasts held at specific times during the calendar year. The Judaizers were teaching Gentile Saints that to be saved they essentially had to become Jewish and do Jewish works—the rituals of the law of Moses. The Judaizers probably emphasized circumcision because it was the rite by which one entered the old covenant and committed oneself to the obligations of the law of Moses; for this reason, the term circumcision became an abbreviated way of referring to all the requirements of the law. [18]

With this understanding, we can appreciate why Paul bolstered his argument by referring to Abraham. For Paul, Abraham was an ideal case study, the quintessential role model of one who was justified by faith and not by the works of the law of Moses. [19] First, Paul observed that scripture itself, in Genesis 15:6, said that God imputed righteousness (or justification) to Abraham based on his faith: “Abraham believed [episteusen, “had faith in”] God, and it was accounted to him for righteousness” (Galatians 3:6; emphasis added). Moreover, Paul pointed out, Abraham lived more than four centuries before Moses. Since he was declared righteous by God before the law of Moses even existed, justification could not be said to come by the law of Moses: “Now to Abraham and his seed were the promises made. . . . And this I say, that the covenant, that was confirmed before of God in Christ, the law, which was four hundred and thirty years after, cannot disannul, that it should make the promise of none effect” (Galatians 3:16–17). [20]

Since Jews and believing Gentiles revered Abraham as the “father” of the faithful (see Romans 4:11,16), Paul’s demonstration that Abraham himself was justified by faith and not by the law of Moses was a persuasive argument against the Judaizers. Paul reasoned: “Know ye therefore that they which are of faith, the same are the children of Abraham” (Galatians 3:7)—that is, Gentile converts who were embracing the gospel of Jesus Christ by faith were being justified in the same way Abraham was and were to be considered among the covenant people. “And the scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the heathen [ta ethnē, “the Gentiles”] through faith, preached before the gospel unto Abraham, saying, In thee shall all nations [ethnē, “Gentiles”] be blessed. So then they which be of faith are blessed with faithful Abraham” (Galatians 3:8–9).

Paul anticipated that his readers would wonder, “If Abraham could be justified without the law of Moses, why did God ever give the law?” Paul wrote:

Wherefore then serveth the law? It was added because of transgressions, till the seed should come to whom the promise was made.... Wherefore the law was our schoolmaster to bring us unto Christ, that we might be justified by faith. But after that faith is come, we are no longer under a schoolmaster (Galatians 3:19, 24–25).

Paul was urging the Galatian Saints to abide in the new covenant, the gospel covenant, rather than regress to the terms of the old covenant under the Mosaic law. [21]

We can see that in this context, when Paul taught that men are not justified by works, he was not referring to “works” generally as efforts to obey God, good deeds of charity, or striving to live the gospel. Paul was not teaching that human efforts are unimportant in the process of salvation. This confusion sometimes arises because of later contexts (particularly Ephesians 2:8–9) in which Paul does appear to have used the term works more generally. But those passages use different terms in a different context and thus teach a different doctrine. [22] Part of our responsibility as teachers is to help our students avoid confusing the terms and contexts of different scripture passages. In the specific context of Galatians, Paul used works to mean distinctively Jewish practices of the law of Moses. (This is also true of Paul’s teachings in Romans 3:20–31.) He was teaching that the means of salvation that God had provided for all people, Jew and Gentile, was ultimately not the law of Moses but the Atonement of Jesus Christ. Salvation came through Christ; the law had been given to lead Israel to Christ.

What, then, did Paul mean by faith in the statement that we are justified “by the faith of Jesus Christ [dia pisteōs Iēsou Christou]” (Galatians 2:16)? [23] Since the Greek word translated faith (pistis) can mean both “faith” and “faithfulness,” and the grammar of the Greek phrase is ambiguous, Paul’s statement can teach more than one truth. First, it teaches that we are justified by our faith in Jesus Christ. This is seen in the logic of Galatians 2:16: “Knowing that a man is not justified by the works of the law, but by the faith of Jesus Christ, even we have believed in Jesus Christ [eis Christon Iēsoun episteusamen, “we have placed our faith in Jesus Christ”], that we might be justified by the faith of Christ” (emphasis added). [24]

Second, Paul’s statement teaches that we are justified by the faithfulness of Jesus Christ—that is, by Jesus Christ’s own faithfulness in atoning for our sins. [25] This is seen in Paul’s testimony that it was the suffering and death of Christ that made redemption from sin possible (see Romans 3:24–25; 5:10–11; Galatians 3:13). The ambiguous phrasing chosen by the King James translators, “by the faith of Jesus Christ” (Galatians 2:16; emphasis added), preserves both teachings—both our faith in Christ and his faithfulness in atoning for us are essential elements of our salvation.

In teaching about our faith in Christ, Paul did not use the word faith to mean merely passive mental assent. The Greek words translated faith (pistis) and to have faith or to believe (pisteuō) both have layers of meaning that imply a deep level of belief resulting in personal commitment and action—connotations like trust, confidence, faithfulness, and obedience. [26] Thus, Paul spoke of “faith which worketh” (Galatians 5:6). Elsewhere, he wrote of “obedience to the faith” (Romans 1:5) or “the obedience that comes from faith,” [27] “obey[ing] the gospel” (Romans 10:16), “bringing into captivity every thought to the obedience of Christ” (2 Corinthians 10:5), and even “obedience unto righteousness [dikaiosunēn, or “justification”]” (Romans 6:16). For Paul, placing faith in Jesus Christ naturally involved repenting, being baptized in Christ’s name, receiving the Holy Ghost, and striving to live the Savior’s teachings (see Acts 16:30–33; 19:1–6; Romans 6:1–11; 1 Corinthians 6:9–11).

As Paul reminded the Galatian Saints, their faith was inseparably connected to their baptism: “Ye are all the children of God by faith in Christ Jesus. For as many of you as have been baptized into Christ have put on Christ” (Galatians 3:26–27). For that reason, they were not to regard a life of faith as license to sin or “an occasion to the flesh” (Galatians 5:13), but they were to “walk in the Spirit” and thus “not fulfil the lust of the flesh” (Galatians 5:16; see also vv. 17–25).

Nevertheless, Paul did not classify baptism or obedience to the gospel as works, because, as we have seen in this context, works meant works of the law of Moses—distinctively Jewish rituals—not general efforts to live the gospel. Paul saw baptism and obedience to the gospel as outgrowths of faith in Jesus Christ. For Paul, faith meant a wholehearted acceptance of salvation through the Atonement of Christ; to place faith in Christ was to commit oneself into his care with a trust that naturally manifested itself in actions such as repentance, baptism, and striving to live by the Spirit.

Just as circumcision was an abbreviated way of referring to the entire law of Moses, Paul’s use of faith in Christ, as the first principle of the gospel, seems to function as an abbreviated way of referring to living the principles and ordinances of the gospel of Jesus Christ. At least, living those principles and ordinances was implied by Paul’s use of the term faith. As Stephen E. Robinson explained: “Paul clearly understands faith to be more than just believing. For him faith still retains its Old Testament meaning of ‘faithfulness’ . . . or commitment to the gospel. . . . If we use Paul’s definition of faith as faithfulness to the gospel covenant, then we find that Paul’s formula . . . is correct: Faith alone (commitment to the gospel) will justify us to God, even without living the law of Moses.” [28] What Paul taught the Galatians was essentially what we proclaim in the third article of faith: “We believe that through the Atonement of Christ”—not the performances of the law of Moses—“all mankind may be saved, by obedience to the laws and ordinances of the Gospel.”

Avoiding Confusion with Paul’s Later Writings

As Paul later wrote to the Saints in Rome, he expanded upon many of the same teachings that he had presented in Galatians (see Romans 1–8). In particular, he again expounded the doctrine of justification by faith in Christ apart from “the deeds [ergōn, “works”] of the law” (Romans 3:28). [29] But further into the epistle, Paul began referring simply to “works,” dropping the appellation “of the law” that he had consistently used in Galatians (see Romans 4:2,6; 9:11; 11:6). Perhaps in some of these instances, Paul was just being concise, using “works” as a shorter way of referring to “works of the law.” [30] However, he also seems to have begun using the term works in a way that differs significantly from his earlier, narrow focus on the rituals of the Mosaic law. Notice that in each of these passages where Paul referred simply to works, he also referred to grace: “For if Abraham were justified by works, he hath whereof to glory; but not before God. For what saith the scripture? Abraham believed God, and it was counted unto him for righteousness. Now to him that worketh is the reward not reckoned of grace, but of debt” (Romans 4:2–4; emphasis added). “And if by grace, then is it no more of works: otherwise grace is no more grace. But if it be of works, then is it no more grace: otherwise work is no more work” (Romans 11:6).

Still later, Paul wrote the epistle to the Ephesians, [31] once more referring to “works” and not “works of the law,” and again writing about “grace”: “For by grace are ye saved through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God: not of works, lest any man should boast” (Ephesians 2:8–9; emphasis added).

Briefly, two important characteristics of these passages need to be recognized. First, Paul was using different terms to make a different comparison, juxtaposing “works” and “grace,” not “works of the law” and “faith in Christ.” The difference in terminology and usage signals a difference in doctrinal teaching. [32] While Paul’s teachings about faith and works of the law in Galatians and Romans3 dealt with the gospel of Christ (the new covenant) and the law of Moses (the old covenant), Paul’s teachings about grace and works change the subject to that of God’s role compared with ours in the salvation process. Works in this context does appear to refer more broadly to our acts of religious devotion in general. Paul’s statement in Ephesians that we are saved “by grace” and “not of works” teaches the doctrine that ultimately, even our faith-driven efforts to live the gospel do not save us—it is Jesus Christ who saves us. [33] Christ’s Atonement, and all the saving blessings it brings, constitutes the great manifestation of God’s grace toward us (see John 3:16; Romans 3:24; 5:6–11). Without it, we would be forever lost (see 2 Nephi 2:8–9; 9:7–9; Alma 34:9; D&C 76:61,69). On the basis of our works, we all fall short.

As Paul wrote to the Saints in Rome, “All have sinned, and come short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23). Therefore, he taught, if we are to be justified, it can only be “freely by [God’s] grace through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus” (Romans 3:24). [34] Paul taught the Saints in Philippi that even our efforts to live our faith, to “work out [our] own salvation,” are possible only because of grace, “for it is God which worketh in [us] both to will and to do of his good pleasure” (Philippians 2:12–13). [35]

Second, we should note that Paul’s contrast between works and grace does not appear at all in Galatians (an early epistle), that it is used obliquely in Romans (a somewhat later epistle), and finally that it forms the basis of a clear, overt statement about salvation in Ephesians (a still later epistle). Paul’s increasing emphasis on grace over time suggests that it was a doctrine that grew increasingly important to him with reflection and life experience. [36] The doctrine of grace affected the way Paul came to view works in general. It deepened his appreciation for the Atonement of Christ. Thus, we cannot assume that even Paul always meant the same thing by the terms he used. We all grow over time in our understanding and appreciation of gospel principles, and such “line upon line” growth is reflected in what we teach and write.

Misunderstandings and Misrepresentations of Paul’s Teachings

As we move from understanding Paul to understanding James, we first need to consider how Paul’s teachings were received and reported, for that provides valuable context for the epistle of James. A number of details in the latter half of the New Testament indicate that misunderstandings and misrepresentations of Paul’s teachings circulated among the early members of the Church. The second epistle of Peter mentions this: “Our beloved brother Paul . . . according to the wisdom given unto him hath written unto you; as also in all his epistles, . . . in which are some things hard to be understood, which they that are unlearned and unstable wrest [streblousin, “distort, twist”], as they do also the other scriptures, unto their own destruction” (2 Peter 3:15–16).

Passages in Romans in which Paul defended himself give us a glimpse at some of the ways people were “wresting” his teachings. In Romans 3:8, Paul mentioned that it was being “slanderously reported” that he and his missionary companions were teaching, “Let us do evil, that good may come.” This appears to have been one of the attacks on Paul’s way of presenting the gospel. Paul taught that God’s response to the problem of human sin was to offer redemption through the Atonement of his Son (see Romans 1–3; Galatians 3:22). Since the Atonement was a good thing, and it came in response to a bad thing (sin), Paul’s opponents mocked it by making it appear logically ridiculous: If God responds to sin with goodness, then why not sin? “Let us do evil, that good may come.” Paul bluntly expressed how he felt about those who were so perversely misrepresenting his message: “[Their] damnation is just” (Romans 3:8). Twice more in his epistle to the Romans, Paul refuted the charge that he promoted or condoned sin (see Romans 6:1–2, 14–15).

Paul was also accused of teaching against the law of Moses, which if true would have been regarded as a serious offense—blasphemy—for the law had been given by God. But Paul took pains to clarify that the law was good. The law was not responsible for human sin or the consequences of sin; the law merely made human sins clear for all to recognize:

By the law is the knowledge of sin....

What shall we say then? Is the law sin? God forbid. Nay, I had not known sin, but by the law: for I had not known lust, except the law had said, Thou shalt not covet....

Wherefore the law is holy, and the commandment holy, and just, and good.

Was then that which is good made death unto me? God forbid. But sin, that it might appear sin, work[ed] death in me by that which is good; that sin by the commandment might become exceeding sinful. (Romans 3:20; 7:7, 12–13)

Paul explained that the problem with the law was that while it clarified what sin was, it did not deal with the problem of human weakness or impart spiritual life (see Romans 8:3; Galatians 3:21). For that, we needed the Atonement of Christ.

Notwithstanding Paul’s insistence that he was not teaching against the law, and that justification by faith did not condone sinful behavior, misrepresentation and hostility continued. When Paul returned to Jerusalem following his third missionary journey, a riot broke out in the temple courts when Jews from Asia Minor spotted Paul in the temple: “The Jews which were of Asia, when they saw him in the temple, stirred up all the people, and laid hands on him, crying out, Men of Israel, help: This is the man, that teacheth all men every where against the people, and the law, and this place” (Acts 21:27–28).

Understanding James’ Use of Faith and Works

The persistent misrepresentations of Paul’s teachings might help explain why James wrote the passage quoted at the outset of this paper. It seems that James wrote not to counter what Paul had taught or written, but more likely to counter distortions of Paul’s teachings like the ones we can see were in circulation during the time Paul and James ministered as Apostles.

We know from the account in Acts 21 that after Paul’s third mission, he met with James in Jerusalem. James and the elders of the Church told Paul that the members of the Church in Jerusalem, who were “all zealous of the law,” had heard that Paul had been teaching Jews “to forsake Moses” and “not to circumcise their children, neither to walk after the customs” (Acts 21:20–21). This, of course, was not true; Paul and the other Apostles taught that Gentile members of the Church did not need to live the law of Moses. [37] James and the elders acknowledged this (see Acts 21:25) but asked Paul to go to the temple and publicly undergo rites of purification (as observant Jews did after they had traveled in Gentile countries), so that “all may know that those things, whereof they were informed concerning thee, are nothing; but that thou thyself also walkest orderly, and keepest the law” (Acts 21:24).

To dispel the rumors, Paul went to the temple as requested—and that is where the riot broke out and Paul was arrested (see Acts 21:26–36). We learn some important facts from this account: James and his associates had indeed heard misrepresentations of Paul’s teachings; James was interested in putting those rumors to rest; James wanted to help Jews in Jerusalem see that Paul was not the threat he was made out to be; and Paul was willing to cooperate with James in this effort. Though many commentators have emphasized the seeming disagreement between Paul and James, it is possible to see them as mutually supportive, each ministering to different ethnic groups, and both trying very hard to keep the Church together at this time of extraordinary cross-cultural tensions. We do not know whether James wrote his epistle before or after this meeting, but we can see at least that he was disposed to alleviate misunderstandings about Paul’s teachings. [38]

If James wrote his epistle toward the end of his life (about AD 62), after Paul had written Galatians and Romans (before AD 59), it is possible that he wrote in response to distortions of Paul’s written teachings. But even if James wrote his epistle much earlier, we need to remember that Paul’s teachings would have been in circulation before he ever wrote Galatians and Romans. The account of Paul’s first mission that we read in Acts shows that even at that early date, Paul preached the same doctrine of justification by faith that he would later expound and defend in his epistles: “Through this man [Jesus Christ] is preached unto you the forgiveness of sins: and by him all that believe are justified from all things, from which ye could not be justified by the law of Moses” (Acts 13:38–39). Moreover, in Paul’s epistle to the Romans, he stated that the gospel message he presented to them was the same that he had already preached throughout his years of missionary labors from Jerusalem to Illyricum (see Romans 1:15–17; 15:18–22).

Paul faced opposition from Jews nearly everywhere he preached (see Acts 13:45; 14:1–5, 19; 17:5–13; 18:5–6, 12; 19:8–9), and every year at least some Jews from those locales would have traveled to Jerusalem for the feasts of Passover, Pentecost, or Tabernacles (see Acts 2:1, 5–11), potentially bringing with them news of Paul’s activities. Orally transmitted distortions of Paul’s teachings could have come to James’ attention in Jerusalem from early on in Paul’s ministry. Therefore, whether one postulates an early or late date for the writing of James, it is possible that the epistle could have responded to reports of Paul’s teachings. [39]

It does seem that James was responding to such accounts, judging from phrases he used to introduce his discussion on faith and works: “What doth it profit, my brethren, though a man say he hath faith, and have not works?... Yea, a man may say, Thou hast faith, and I have works” (James 2:14, 18; emphasis added). These phrases suggest that James and his readers were aware of people who were speaking in a simplistic way about faith absent from works. [40] The phrase “faith without works” (pistis chōris ergōn), found twice in James (James 2:20,26), is also found in Paul’s epistle to the Romans: “Therefore we conclude that a man is justified by faith without the deeds [pistei . . . chōris ergōn] of the law” (Romans 3:28). It is reasonable to suppose that the phrase “faith without works” that Paul used in this verse was one that he also used on occasion in his teaching which may have been repeated and passed on by those who heard him. Over time, the phrase “faith without works” could have become a catchphrase disconnected from the original context and meaning Paul had given it. [41]

Certainly Paul’s meaning of faith and works in Galatians is not the same as what we find in the epistle of James. In James 2:14–26, James used faith in two ways: (1) true faith, meaning belief that impels to action (similar to Paul’s usage) and (2) a merely passive mental acquiescence resulting in no changes in behavior, loyalty, or character. [42] By works, James did not mean rituals of the law of Moses, as Paul did in Galatians, but good deeds and actions consistent with the belief one professes. We can see these usages at work throughout these verses in James.

“What doth it profit, my brethren, though a man say he hath faith, and have not works? can faith [hē pistis] save him?” (James 2:14). The King James Version does not translate the Greek article h? before the second use of “faith.” The article renders the sense of the question “Can [that sort of] faith save him?” [43] James was not making a blanket statement about faith in general; he was making a statement specifically about a false representation of faith as something passive, something that does not lead to any action.

This is the first of several places where James’ Greek employed an article to differentiate true faith from nonresponsive assent. Another is seen in the verses that immediately follow: “If a brother or sister be naked, and destitute of daily food, and one of you say unto them, Depart in peace, be ye warmed and filled; notwithstanding ye give them not those things which are needful to the body; what doth it profit? Even so faith [hē pistis], if it hath not works, is dead, being alone [or, Even so that kind of faith, which results in no action, is dead]” (James 2:15–17). Again, what James rejected as ineffective was not true faith in Christ, but only the shallow so-called “faith” that made no difference in one’s behavior. Here we also see that works, for James, means “actions consistent with what one professes.” If you really want the hungry to be fed, you do what you can to feed them.

“Yea, a man may say, Thou hast faith, and I have works: shew me thy faith without thy works, and I will shew thee my faith by my works” (James 2:18). This verse is comprised of three statements: (1)The quotation “Thou hast faith, and I have works,” which might be paraphrased, “One person has faith and another has works,” is essentially claiming that faith and works are not necessarily connected and that a person might conceivably have one without the other. [44] James refuted this claim with the next statement: (2)“Shew me thy faith without thy works,” a challenge rhetorically pointing out an impossibility; it is not possible to show one’s faith except through one’s actions. Thus James concluded: (.I will shew thee my faith by my works.”

“Thou believest that there is one God; thou doest well: the devils also believe, and tremble. But wilt thou know, O vain man, that faith [hē pistis] without works is dead?” (James 2:19–20). This last sentence could alternately be translated, “Know that that kind of faith that is without works is unproductive.” [45] Here again, James was not teaching about faith in general but was continuing to demonstrate the ineffectiveness of the so-called “faith” that is nonresponsive. Even devils can have this kind of “belief,” acknowledging, for example, that Jesus is the Christ, while refusing to give him their allegiance (see Mark 1:24, 34; 3:11; 5:7).

James next turned, as Paul did, to the example of Abraham. Again, Paul’s teachings about Abraham may well have been in circulation when James wrote, whether that was before or after Paul wrote Galatians and Romans. Since Paul’s preaching typically involved quoting from the scriptures of the Old Testament (see Acts 17:2–3, 10–12; 28:23), it is reasonable to expect that as he taught about justification by faith rather than by the law (see Acts 13:38–39), he appealed to some of the same scriptures he later quoted in his epistles—including Genesis 15:6 and the example of Abraham. It is plausible, therefore, that James could have heard distorted versions of what Paul had taught about Abraham and felt impelled to reassure his readers and correct doctrinal misunderstandings. We know that pious, law-abiding Jewish Christians complained to James of rumors they heard about Paul’s teachings (see Acts 21:18–21). If at some point such complaints included the charge that Paul’s converts spoke simplistically of “faith without works” and defended themselves by invoking Genesis 15:6, James could hardly have clarified what true faith is more effectively than he did in James 2:21–24: “Was not Abraham our father justified by works, when he had offered Isaac his son upon the altar? Seest thou how faith wrought with [sunērgei, “worked with”] his works, and by works was faith made perfect [eteleiōthē, “made complete”]? And the scripture was fulfilled which saith, Abraham believed God, and it was imputed unto him for righteousness: and he was called the Friend of God. Ye see then how that by works a man is justified, and not by faith only.”

The driving question in James’ teaching here was not “How are we saved?” but “What is true, complete faith?” James answered that such faith is shown in our actions, and cannot be isolated from actions (“faith only”). Paul would have agreed, for, as we have seen, Paul did not conceive of faith without obedience. Thus James did not oppose Paul; he opposed only the false idea that faith was passive. Paul would not have disagreed. Paul had taught that God offered salvation through the Atonement of Christ, and thus the way we receive the blessings of the Atonement is by faith in Christ—faith that leads us to enter the new covenant and live the gospel. James would not have disagreed.

As President Joseph Fielding Smith stated about Paul and James, “There is no conflict in the doctrines of these two men.” [46] The Mormon position, as Truman G. Madsen stated, is “a repossession of a New Testament understanding that reconciles Paul and James.” [47]

Both Paul and James taught faith in Jesus Christ and lived by that faith. Both knew that true faith in Christ transforms us, for both had experienced personal transformation arising from their faith. James had initially disbelieved that his brother Jesus was the Christ, and Paul had initially persecuted the Church (see Mark 3:21; John 7:5; Acts 9:1–2; Galatians 1:13). Both had their own sacred experiences coming to know the risen Lord (see Acts 9:1–22; 1Corinthians 15:7). And crowning their faithful service as Apostles, both, within a few years of each other, gave their lives as martyrs, [48] sealing their testimonies with their blood, and showing by their deeds their faith in Jesus Christ.

Notes

[1] For the general form in which this problem is cast, I am indebted to presentation of the subject in Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 316–17. Though I find Ehrman’s way of presenting the problem useful, I disagree with him on numerous points of analysis and interpretation, as I will note in references to follow. My approach to this subject is also somewhat similar to that of Stephen E. Robinson (see Following Christ [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1995], 82–85) and of Brian M. Hauglid (see “The Epistle of James: Anti-Pauline Rhetoric or a New Emphasis?” in The Life and Teachings of the New Testament Apostles, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Thomas A. Wayment [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010], 157–70). I agree with Robinson and Hauglid generally that Paul and James harmonize in doctrine while differing in semantics, audience, and historical setting, but the scope of this paper has permitted a more in-depth, contextual look at these issues.

[2] Topical Guide, “Justification, Justify,” 265. However, Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Eric D. Huntsman, and Thomas A. Wayment maintain that “James does not discuss the technical subject of justification—restoring a sinner to good standing before God—as does Paul.” Jesus Christ and the World of the New Testament (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006), 271. What James meant by the terms dikaiosunē (righteousness, justification) and dikaioō (justify) in James 2:21, 23–24 is a much-debated subject. Although the dating of James’ epistle in relation to Paul’s letters is not known, I would suggest that James at least wrote in response to oral reports of Paul’s teachings (if not his writings). James’ use of the terms, whatever he meant by them, is important to acknowledge, for it lends support to the idea that he wrote in response to Paul’s teachings, in which justification figures prominently. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that James’ intent in James 2:14–26 was not to answer the question “How are we justified?” but to answer the question “What is true faith?”

[3] The King James Version of Galatians 3:6 and James 2:23 uses the word righteousness to translate the Greek dikaiosunēn (justification) found in the Greek Septuagint version of Genesis 15:6 quoted by both Paul and James.

[4] The classic example is Martin Luther, who in the preface to his 1522 edition of the Bible wrote of the epistle of James: “It is flatly against St. Paul and all the rest of Scripture in ascribing justification to works. It says that Abraham was justified by his works when he offered his son Isaac; though in Romans 4 St. Paul teaches to the contrary that Abraham was justified apart from works, by his faith alone, before he had offered his son, and proves it by Moses in Genesis15. Now although this epistle might be helped and an interpretation devised for this justification by works, it cannot be defended in its application to works of Moses’ statement in Genesis 15. For Moses is speaking here only of Abraham’s faith, and not of his works, as St. Paul demonstrates in Romans 4. This fault, therefore, proves that this epistle is not the work of any apostle. . . . [Its author] wanted to guard against those who relied on faith without works, but was unequal to the task in spirit, thought, and words. He mangles the Scriptures and thereby opposes Paul and all Scripture.” “Luther’s Treatment of the ‘Disputed Books’ of the New Testament,” Bible Research: Internet Resources for Students of Scripture website, http://

[5] For example, see E. Richard Packham, “My Maturing Views of Grace,” Ensign, August 2005, 22–25; David Rolph Seely and JoAnn H. Seely, “Paul: Untiring Witness of Christ,” Ensign, August 1999, 28; Robert E. Parsons, “I Have a Question,” Ensign, July 1989, 59–61; Daniel C. Peterson and Stephen D. Ricks, “Comparing LDS Beliefs with First-Century Christianity,” Ensign, March 1988,7; Jack Weyland, “I Have a Question,” Ensign, January 1985, 43–45; Gerald N. Lund, “Salvation: By Grace or by Works?,” Ensign, April 1981, 16–23.

[6] The author of the Epistle of James was probably James, the Lord’s brother, a son of Mary and Joseph, not James the son of Zebedee and brother of John. Though James the brother of the Lord was not one of the original Twelve, Paul implied that he later became an Apostle (as James the son of Zebedee had been) when he mentioned meeting him and Peter during a visit to Jerusalem: “But other of the apostles saw I none, save James the Lord’s brother” (Galatians 1:19; see also 1 Corinthians 9:5). Paul stated that this James, along with Cephas (Peter) and John were “pillars” in the Church at Jerusalem (Galatians 2:9). The second century AD Christian writer Papias referred to James as “James the bishop and apostle” Fragment X, in Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, eds., Ante-Nicene Fathers: The Writings of the Fathers Down to A.D. 325, vol. 1, The Apostolic Fathers, Justin Martyr, Iranaeus (1885; Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1995), 155.

[7] History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1980), 6:303.

[8] The Prophet Joseph Smith stated: “I have a key by which I understand the scriptures. I enquire, what was the question which drew out the answer, or caused Jesus to utter the parable? . . . To ascertain its meaning, we must dig up the root and ascertain what it was that drew the saying out.” History of the Church, 5:261.

Professor Krister Stendahl helped revolutionize the world of Pauline scholarship with his assessment that traditional Christian interpretation of Paul had taken his writings out of context by approaching them with the wrong questions: “We tend to read him as if his question was: On what grounds, on what terms, are we to be saved? . . . But Paul was chiefly concerned about the relation between Jews and Gentiles—and in the development of this concern he used as one of his arguments the idea of justification by faith. . . . If we read Paul’s answer to the question of how Gentiles become heirs to God’s promises to Israel as if he were responding to Luther’s pangs of conscience, it becomes obvious that we are taking the Pauline answer out of its original context.” Paul among Jews and Gentiles (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1976), 3.

[9] The term “Judaizers” comes from a Greek word used by Paul when he took issue with Peter for implicitly compelling Gentile Saints “to live as do the Jews [Ioudaizein]” (Galatians 2:14). For more information, see The Eerdmans Dictionary of Early Judaism, ed. John J. Collins and Daniel C. Harlow (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2010), “Judaizing,” 847–48.

[10] See Matthew 23:15; Acts 2:10; 6:5; 13:43; Bible Dictionary, “Proselytes,” 754.

[11] After James proposed the dietary counsel that should be given to Gentile Christians (see Acts 15:20), he spoke of its reason: “For Moses of old time hath in every city them that preach him, being read in the synagogues every sabbath day” (Acts 15:21). That is, throughout the regions where Paul and his companions were doing missionary work and Gentiles were joining the Church, there were communities of Diaspora Jews. The implicit meaning is that in the Church’s missionary approach to bring the gospel to Jews first and then to the Gentiles (see Romans 1:16), the Church should avoid causing any undue offense to Jews, thus creating potential hindrance to Jews in accepting the gospel.

The distinction between commandments observed as moral imperatives and others observed out of cultural sensitivity is seen in Paul’s teachings. He repeatedly taught that those who persisted in sexual sin and idolatry would not inherit the kingdom of God (see 1 Corinthians 6:9–10; Galatians 5:19–21; Ephesians 5:5), but in none of these passages did he teach that failure to observe kosher laws would disqualify Gentile Christians from the kingdom (admittedly an argument from silence). However, he did teach Gentile Saints to avoid giving offense in matters regarding what they ate and where they dined (see Romans 14:1–15:3; 1 Corinthians 8:1–13), and Paul himself voluntarily modified his behavior to avoid offending Jewish sensibilities (see Acts 16:1–3; 21:20–26; 1 Corinthians 8:13; 9:19–22).

[12] For a discussion of the issues related to the dating of Galatians and the argument for a post–Jerusalem conference date of composition, see James Montgomery Boice, “Galatians,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 10, Romans through Galatians (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1991), 409–21. For analysis of Galatians from the perspective of a pre–Jerusalem conference date of composition, see Holzapfel, Huntsman, and Wayment, Jesus Christ and the World of the New Testament, 216–21. For analysis of Acts 15 demonstrating correspondence with Galatians 2 and therefore supporting a post–Jerusalem conference composition of Galatians, see Boice, “Galatians”; Frank F. Judd Jr., “The Jerusalem Conference: The First Council of the Christian Church,” Religious Educator12, no.1 (2011): 55–71.

[13] The exact location of Galatia, and thus the exact makeup of Paul’s audience, is another much-debated topic among New Testament scholars. Two competing hypotheses posit a northern, ethnically defined Galatia versus a southern, politically defined Galatia. For a presentation of both views, see Boice, “Galatians,” 412–17; see also Richard Lloyd Anderson, Understanding Paul, rev. ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2007), 147–48. If Paul wrote to the Saints in southern Galatia, he would have been writing to the congregations he established on his first missionary journey in cities such as Derbe, Lystra, Iconium, and the Pisidian Antioch, which he apparently visited on later missionary journeys (see Acts 16:6; 18:23).

[14] Paul, however, did circumcise Timothy as they prepared to embark on a mission together (see Acts 16:1–3). This act should be understood not as a requirement of salvation for Gentiles, but as a measure taken to enable Timothy to be an effective missionary to Jews as well as Gentiles (see Acts 16:3). Timothy, whose mother was Jewish but whose father was a Gentile, apparently had never been circumcised. He willingly underwent full conversion to Judaism to remove any potential obstacle for Jews to receive the gospel message from him. In this sense he reflected the ethic of his mentor Paul: “Unto the Jews I became as a Jew, that I might gain the Jews; to them that are under the law, as under the law, that I might gain them that are under the law” (1 Corinthians 9:20).

[15] See Babylonian Talmud, Makkot, 23b–24a. But this traditional counting may be conservative: “When the Mishnah was written down not long after Paul, it had sixty-three chapters containing five thousand to ten thousand rules on what a righteous Jew could and could not do.” Anderson, Understanding Paul, 159.

[16] Guide to the Scriptures, “Justification, Justify,” http://

[17] See “works of the law” in Galatians 3:2, 5,10. Other uses of “work” and “works” appear in Galatians, but in different contexts, not as a part of Paul’s discussion of justification by faith in Christ rather than by the works of the law of Moses. For example, Galatians 5:6 (energoumenē, “faith which worketh [within us] by love”); 5:19 (ta erga tēs sarkos, “the works [deeds] of the flesh”); 6:4 (ergon, “let every man prove his own work,” where “work” parallels “burden” in 6:5 and deals with personal responsibility; emphasis added).

[18] “The word circumcision seems to have been representative of the law” (Bible Dictionary, “Circumcision,” 646). Similarly, “they of the circumcision” was synonymous with “Jews,” while “the uncircumcision” referred to the Gentiles (see Acts 10:45; 11:2; Romans 3:30; 4:9–12; 15:8; Galatians 2:7–9, 12; Ephesians 2:11; Colossians 4:11; Titus 1:10).

[19] Paul may also have appealed to Abraham in response to arguments the Judaizers might have posed to the Galatians regarding Abraham. For example, the Judaizers might have argued that since Abraham had been circumcised (see Genesis 17:23) and God had told Abraham, “In thee shall all nations [ethnē, “Gentiles”] be blessed” (Galatians 3:8, quoting Genesis 22:18), the Galatian Saints, as Gentile converts, should be circumcised as Abraham was.

[20] It should also be noted that Abraham was declared righteous in Genesis 15:6—about fourteen years before he underwent circumcision (see Genesis 17:23). Paul’s audience was conversant with the scriptures of the Old Testament and may have recognized this implicit point.

[21] Paul expounded on “the two covenants” (Galatians 4:24) by use of the allegory of Hagar/

[22] Ephesians 2:8–9 juxtaposes grace and works, not faith (in Jesus Christ) and works of the law. See discussion in the next section, “Avoiding Confusion with Paul’s Later Writings.” See also Holzapfel, Huntsman, and Wayment, Jesus Christ and the World of the New Testament, 221.

[23] Paul used the identical Greek phrase in Romans 3:22 (“The righteousness of God which is by faith of Jesus Christ [dia pisteōs Iēsou Christou] unto all and upon all them that believe”; italics added). Paul also used nearly the same phrase in Philippians 3:9 (“not having mine own righteousness, which is of the law, but that which is through the faith of Christ [dia pisteōs Christou], the righteousness which is of God by faith”; emphasis added).

[24] See also Romans 3:22: “The righteousness of God which is by faith of Jesus Christ unto all and upon all them that believe [tous pisteuontas, “those who have faith (in Christ)”]”; and Romans 3:26: God is “the justifier of him which believeth in [ek pisteōs, “has faith in”] Jesus.” Note that Paul’s teaching of justification by faith echoes Peter’s teaching at the Jerusalem council: “[God] put no difference between us [the Jews] and them [the Gentiles], purifying their hearts by faith” (Acts 15:9; italics added). The doctrine of justification by faith was not Paul’s invention, as is sometimes claimed; it was based on revelation that Peter, the senior Apostle, had received from the Lord. Stendahl seems to hint at Pauline invention of the doctrine in stating that “a doctrine of justification by faith was hammered out by Paul for the very specific and limited purpose of defending the rights of Gentile converts to be full and genuine heirs to the promises of God to Israel” (Paul among Jews and Gentiles,2). But Professor Stendahl may have meant merely that Paul expounded the doctrine in that particular context; he is certainly correct in observing that traditional Christian interpretation of Paul has failed to read him in context.

[25] See Holzapfel, Huntsman, and Wayment, Jesus Christ and the World of the New Testament, 221; see also Gaye Strathearn, “The Faith of Christ,” in A Witness for the Restoration: Essays in Honor of Robert J. Matthews, ed. Kent P. Jackson and Andrew C. Skinner (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2007), 93–127.

[26] Rudolf Bultmann, in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, traces the usage of pisteuō, pistis, and related terms in classical Greek, Hellenistic Greek, the New Testament in general, and the writings of individual New Testament authors. Examining Paul’s use of these terms, Bultmann concludes: “Paul in particular stresses the element of obedience in faith. For him pistis [faith] is indeed hupakoē [obedience]. . . . Faith is hupakoē [obedience] as well as homologia [profession, confession]. . . . [Faith is] an attitude which controls all life. . . . [Faith is] man’s absolute committal to God.” In Gerhard Friedrich, ed., Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1964–76), 6:206, 217–19). The indivisibility of faith and obedience is seen in the Joseph Smith Translation of Romans 4:16: “Therefore, ye are justified of faith and works, through grace.”

[27] The New International Version (NIV) translates Romans 1:5 hupakoēn pisteōs as “the obedience that comes from faith.” The same phrase appears in Romans 16:26 and is translated “the obedience of faith” in the King James Version.

[28] Stephen E. Robinson, Following Christ: The Parable of the Divers and More Good News (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1995), 84–85.

[29] Romans 2:6–7 and 2:13 have sometimes confused readers: “[God] will render to every man according to his deeds [erga, “works”]: to them who by patient continuance in well doing seek for glory and honour and immortality, eternal life. . . . For not the hearers of the law are just before God, but the doers of the law shall be justified.” These statements seem to contradict what Paul said in the very next chapter: “By the deeds of the law there shall no flesh be justified in [God’s] sight” (Romans 3:20). At first glance, Paul seems to be speaking out of both sides of his mouth, saying first that we are saved by our works, and then that we are not. The key to understanding what Paul said in Romans 2 is, once again, careful attention to context.

Romans 3:9 reveals Paul’s intent in the preceding chapters: “We have before proved both Jews and Gentiles, that they are all under sin.” This is Paul’s overt thesis statement—an interpretive key to the meaning of what he had just argued in Romans 1–2. He had been making a case that all people are under sin. Romans 1:18–32 had formed an indictment of all people for their sins, particularly Gentiles. Beginning in Romans 2:1, Paul had turned his focus on his own people, the Jews, and had begun to explain how they too were all under sin.

Romans 2:6–7 has to be seen in context of the overall argument of Romans 1–3, as well as in the context of its surrounding verses. It is part of a section (Romans 2:5–12) that deals not with the topic of salvation but with “the righteous judgment of God” (Romans 2:5). Since God judges fairly, he “will render to every man according to his deeds” (Romans 2:6; compare Revelation 20:12–13). The obedient will receive glory, honor, and peace, but the disobedient will receive wrath (see Romans 2:7–10). All this is a set-up for what comes next: “For as many as have sinned without law [i.e., the Gentiles] shall also perish without law: and as many as have sinned in the law [i.e., the Jews] shall be judged by the law” (Romans 2:12). Paul is making his case that all people, Jews as well as Gentiles, are guilty of sin. Strictly speaking, there is nobody in the “obedient” category. Without the Atonement, Gentiles and Jews will all perish because of their sins; and Jews, further, will be judged by the law, “for not the hearers of the law are just before God, but the doers of the law shall be justified” (Romans 2:13). It is not enough for Jews merely to possess the law of Moses and hear it read in the synagogue on the Sabbath; they are under covenant to obey it (see Galatians 3:10).

The statement “the doers of the law shall be justified” (Romans 2:13) needs to be understood in light of Romans 3:23: “All have sinned, and come short of the glory of God.” While theoretically, one way of being justified—held guiltless before God—would be to unfailingly keep all the law’s commandments and prohibitions throughout one’s life (thus being a “doer of the law”), no one other than Jesus truly does this. All have sinned (see Romans 3:9–20). Paul’s logic prepares the way for him to present the most important point of his message—that God has provided a way for man to be justified, a way that is possible with faith, and it is through the Atonement of Jesus Christ: “But now the righteousness [dikaiosunē, “justification”] of God without the law is manifested, . . . even the righteousness of God which is by faith of Jesus Christ unto all and upon all them that believe. . . . God hath set forth [Jesus Christ] to be a propitiation through faith in his blood, to declare his righteousness for the remission of sins that are past” (Romans 3:21–22, 25).

[30] For example, the reference to “works” in Romans 9:11 occurs in proximity to the phrase “the works of the law” in Romans 9:32. However, the references to “works” in Romans 4:2,6 also occur near references to “deeds [works] of the law” in Romans 3:20, 28 but nevertheless seem to carry a more general meaning of “works” since they juxtapose “works” and “grace.”

[31] Though many modern New Testament scholars believe Paul did not write Ephesians, their arguments seem flawed by (1) treating Paul’s thought and language as static, failing to consider the possibility of development in his thought over time, and (2) failing to account for Paul’s use of scribes in the process of writing epistles. For an excellent discussion of the topic of Paul’s use of scribes and how this relates to questions of authorship, see Lincoln H. Blumell, “Scribes and Ancient Letters: Implications for the Pauline Epistles,” in How the New Testament Came to Be: Sidney B. Sperry Symposium, ed. Kent P. Jackson and Frank F. Judd Jr. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006), 208–26.

[32] See Holzapfel, Huntsman, and Wayment, Jesus Christ and the World of the New Testament,221.

[33] This is the same doctrine taught by Nephi: “For we labor diligently to write, to persuade our children, and also our brethren, to believe in Christ, and to be reconciled to God; for we know that it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do” (2 Nephi 25:23). The context of this statement, in which Nephi emphasized the importance of dependence upon Christ (see also v. 26), makes it clear that his emphasis is on salvation by grace—that is, even after all we can do, it is only by the grace of God that we are saved. Unfortunately, this scripture is often misapplied to teach the importance of works, as if Nephi had harshly taught, “You will not receive any saving grace until you have first done all you might conceivably have done”—effectively placing the grace of God at an impossible distance and teaching a defacto doctrine of salvation by works. See Stephen E. Robinson, Believing Christ (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 90–92. Modern Apostles have clarified how Nephi’s statement is to be understood: “It is only through the infinite Atonement of Jesus Christ that people can overcome the consequences of bad choices. Thus Nephi teaches us that it is ultimately by the grace of Christ that we are saved even after all that we can do (see 2 Ne. 25:23). No matter how hard we work, no matter how much we obey, no matter how many good things we do in this life, it would not be enough were it not for Jesus Christ and His loving grace. On our own we cannot earn the kingdom of God—no matter what we do. Unfortunately, there are some within the Church who have become so preoccupied with performing good works that they forget that those works—as good as they may be—are hollow unless they are accompanied by a complete dependence on Christ.” M. Russell Ballard, “Building Bridges of Understanding,” Ensign, June 1998,65; emphasis added. See also M. Russell Ballard, “When Shall These Things Be?,” Ensign, December 1996,61; Dallin H. Oaks, “What Think Ye of Christ?,” Ensign, November 1988, 66–67.

[34] The Joseph Smith Translation of Romans 3:24 adds the word only—“being justified only by his grace”—emphasizing the absolute necessity of relying upon the grace of Christ for salvation.

[35] See Oaks, “What Think Ye of Christ?” 66–67.

[36] I am indebted to Professor Eric D. Huntsman for this insight, as he shared it in an inservice meeting for the Curriculum Services Division of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion on November 18, 2008.

[37] “In none of his [Paul’s] writings does he give us information about what he thought to be proper in these matters for Jewish Christians.” Stendahl, Paul among Jews and Gentiles,2. Paul’s own conduct suggests that he himself remained a devout observer of the law (see Acts 16:1–3; 18:18; 21:26; Philippians 3:6), though he sometimes departed from some Jewish customs (such as avoiding table-fellowship with Gentiles) in order to serve effectively as a missionary to the Gentiles (see 1 Corinthians 8:13; 9:19–23; Galatians 2:11–14).

[38] See Holzapfel, Huntsman, and Wayment, Jesus Christ and the World of the New Testament, 271.

[39] In a concurring opinion in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, Sophie Laws argues that it is “unlikely that James was familiar with Paul’s argument as Paul himself presented it.” James had “heard the language [of faith without works] used even more generally [than Paul himself used it], to support a religious attitude which emphasized the pious expression of trust in God and regarded works of active charity as of little importance. . . . It is probable that those who thus appealed to ‘justification by faith’ as their slogan did so on what they saw to be Paul’s authority, and that James knew this.” “James, Epistle of,” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 3:625–26. It is also possible that these rumors came to James from zealous, observant Jews who opposed Paul and distorted what he and his converts were really saying.

[40] The phrase “a man” in the King James Version of James 2:14,18 translates the indefinite Greek pronoun tis (“someone” or “anyone”). James seems to refer not to a specific man (like Paul or some other individual) but indefinitely to some unnamed source or sources of sayings about “faith without works.”

[41] A similar version of this possibility is suggested in Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997),317. Ehrman, however, postulates a late date for the writing of James and thus proposes later contact between the author of James and the orally transmitted oversimplifications of “faith without works.” In my judgment, the New Testament presents ample evidence that distorted reports of Paul’s teachings could have come to James’ attention much earlier than Ehrman is willing to allow. Even in our day, the teachings of Apostles are sometimes misrepresented and distorted, occasionally even by faithful, well-meaning members of the Church. Misunderstanding and misrepresentation are facts of human communication. And if they still happen in our day, with all our communications and information technology, how much more likely are they to have happened in the days of the New Testament Apostles like Paul, particularly among people who opposed him and did not necessarily feel obligated to be accurate.

[42] Ehrman oversimplifies James’ use of “faith,” identifying only the latter usage: “When James . . . speaks of ‘faith’ in 2:14–26, he appears to mean ‘intellectual assent to a proposition.’” New Testament: A Historical Introduction,316. Robinson also identifies only this latter usage, saying that James defined faith as “mere belief.” Following Christ, 84. But as I argue, the Greek articles James used in connection with this definition of “faith” show that James himself did not conceive of “faith” in this way—it was other people who were speaking of “faith” in this distorted sense. Daniel B. Wallace more accurately identifies both usages of “faith” in James: “The author examines two kinds of faith in 2:14–26, defining a non-working faith as a non-saving faith and a productive faith as one that saves” Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1996),219.

[43] Wallace renders the phrase: “This [kind of] faith is not able to save him, is it?” Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics, 219. Several modern translations attempt to convey the nuance added by the article. The NIV, for example, renders the question “Can such faith save him?” and the New American Standard Bible has “Can that faith save him?” (emphasis added).

[44] The analysis of this verse draws from that of Donald W. Burdick, “James,” in Expositor’s Bible Commentary, vol. 12, Hebrews through Revelation, 183.

[45] In James 2:20, the King James Version uses “dead” to translate the Greek argos, which means “unproductive, useless, worthless.” Frederick William Danker, ed., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 3rd. ed. [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000],128). In James 2:17 and 2:26, “dead” more closely translates the Greek nekra, “dead, lifeless.”

[46] Joseph Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation, ed. Bruce R. McConkie (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1954–56), 2:310.

[47] Truman G. Madsen, ed., Reflections on Mormonism: Judeo-Christian Parallels (Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1978),175.

[48] According to Josephus, James was stoned to death in Jerusalem in AD 62 (see Antiquities of the Jews, 20.9.1). Paul, according to tradition, was beheaded in Rome during the reign of Nero, about AD 64. Early references to Paul’s death as a martyr are found in 1 Clement 5:5–7 (dated to about AD 95) and in the epistle of Ignatius to the Ephesians 12:2 (dated to about AD 107).