The Textual Context of Doctrine and Covenants 121–23

Ryan J Wessel

Ryan J. Wessel, "The Textual Context of Doctrine and Covenants 121-23," Religious Educator 13, no. 1 (2012): 103–115.

Ryan J. Wessel (wesselrj@ldschurch.org) was a seminary and institute instructor in Mesa, Arizona when this was written.

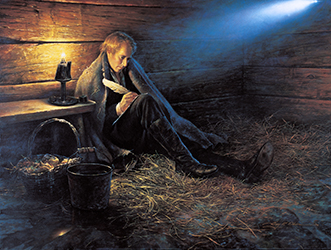

Jerry Thompson, image from Book of Mormon Stories, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Used by permission of Greg Olsen, Art Publishing, Inc.

Jerry Thompson, image from Book of Mormon Stories, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Used by permission of Greg Olsen, Art Publishing, Inc.

Doctrine and Covenants 121–23 is composed of selected portions of a two-part letter dictated March 20–25, 1839, by Joseph Smith while he was incarcerated in Liberty Jail. The letter was addressed “To the Church of Latter-day Saints at Quincy, Illinois, and Scattered Abroad, and to Bishop Partridge in Particular.”[1] The letter was dictated to Alexander McRae and Caleb Baldwin, with a few handwritten corrections by Joseph Smith.[2] Though the Prophet Joseph Smith sent several letters to his wife and other members of the Church from the jail, I will refer to this letter as the Liberty letter.

Portions of the Liberty letter were first published as Doctrine and Covenants 121–23 in the 1876 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants.[3] The portions were selected by Orson Pratt under the direction of President Brigham Young.[4] The edition of the Doctrine and Covenants containing the sections as they currently read was first sustained as scripture at the October 1880 conference of the Church.[5]

The purpose of this paper is to view Doctrine and Covenants 121–23 against the backdrop of the portions of the noncanonical text of the Liberty Jail letter. Similar to historical context, textual context can add depth and meaning to a document by connecting or disconnecting ideas through proximity and by adding information about the author’s situation, surroundings, and disposition in which the document originated. For sections 121–23, the noncanonical portions of the Liberty letter provide that textual context. Understanding this letter is valuable as we prepare to teach our students sections 121–23.

A fairly robust body of work has been published about the noncanonical portions of the letter, presenting different aspects of the history and text to various audiences. The most notable of these articles is by historians Dean C. Jessee and John W. Welch.[6] This paper seeks to build on what has already been published by suggesting specific ways the literary context can be used to teach Doctrine and Covenants 121–23.

While portions of Doctrine and Covenants 121–23 are taken from a much broader literary context, the sections as they read in the scriptures do not omit truths. The literary background gained from a study of the noncanonical text is meant to emphasize, not detract from, the weight and clarity of the canon.

Themes and Threads

When the Liberty letter is viewed as one continuous document, a few themes emerge. The continuity of the letter suggests that we can ascribe some continuity to Doctrine and Covenants 121–23. These themes provide insight into the Prophet Joseph’s heart and mind, attitude, and testimony.

From beginning to end, the Liberty letter reveals the prophetic mantle of Joseph Smith. The Prophet opened the letter in a style similar to Paul’s writings, identifying himself as a “prisoner for the Lord Jesus Christ’s sake... in company with his fellow prisoners.” He then connected himself to Peter, overtly paraphrasing 2Peter 1 by listing virtues and using phrases such as “grace of God,” and “may not be barren.”[7] Later, Joseph Smith was told that his suffering was “not yet as Job” (D&C 121:10), and he stated that his own suffering was comparable to that of Abraham.[8]

It is evident that the Prophet relied on the record of the persecuted to make it through his own persecution. Together with Paul, Peter, Job, and Abraham, he was suffering for the sake of Christ. These comparisons bring to light the Savior’s words: “Blessed are ye, when men shall... persecute you.... Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: . . . for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you” (Matthew 5:11–12). The text shows that Joseph’s experience in Liberty Jail was a personal reaffirmation of his prophetic identity.

Remembering that Joseph spoke with the same prophetic weight as Peter and Abraham reaffirms the scriptural nature of sections 121–23. Like Peter and Abraham, Joseph Smith was able to write with inspiration and reveal the will of the Lord under difficult circumstances and bitter persecution.

Examples

It is helpful to understand that some of the text now designated as Doctrine and Covenants 121–23 was taken from the middle of an idea or paragraph (see D&C 121:33; 123:1). In a few cases, it picks up midsentence (see D&C 121:7, 26). Below are a few examples of how acknowledging the literary context of a block of scripture increases our understanding of the verses.

Compassion. To point out the Prophet’s cry “O God, where art thou?” (D&C 121:1) is a particular favorite of gospel teachers. Joseph pleaded that the Lord’s heart would “be softened toward [the Saints].... Let thine ear be inclined; let thine heart be softened, and thy bowels moved with compassion toward us” (D&C 121:3–4). For many readers, this plea encapsulates our individual need for compassion and help from the Almighty.

As Joseph continued in Doctrine and Covenants 121:5, he shifted focus from the suffering Saints to the guilty mobs. Instead of asking for compassion, Joseph asked for the Lord’s anger, fury, and judgment to fall upon the enemies of the Saints. In the opening paragraphs of the Liberty letter, Joseph passionately enumerated many injustices that were suffered by the Saints and the prisoners in Missouri. He painted a heart-wrenching picture of men “mangled for sport! women... robbed of all that they have..., and finally left to perish with their helpless offspring clinging around their necks.” He then paraphrased Matthew 18:7: “It must needs be that offenses come, but woe unto them by whom they come.”[9] It is in the context of remembering both the offended Saints and the offending mobs that Joseph cried, “O God, where art thou?” (D&C 121:1).[10]

In response to section121, we see a God who not only aids his ailing children but also, in his own due time, punishes his offending children (see D&C 121:7–25). Elder Dallin H. Oaks explained how both God’s compassion and wrath are exercised to the same end:

We read again and again in the Bible and in modern scriptures of God’s anger with the wicked and of His acting in His wrath against those who violate His laws. How are anger and wrath evidence of His love? Joseph Smith taught that God “institute[d] laws whereby [the spirits that He would send into the world] could have a privilege to advance like himself.”[11] God’s love is so perfect that He lovingly requires us to obey His commandments because He knows that only through obedience to His laws can we become perfect, as He is. For this reason, God’s anger and His wrath are not a contradiction of His love but an evidence of His love.[12]

The Prophet Joseph’s plea for both compassion and God’s judgment is evidence of his understanding of God’s love. The Prophet later conveyed, “We do not rejoice in the affliction of our enemies but we shall be glad to have truth prevail.”[13] He understood that anger, fury, and wrath may not be preferable, but they are sometimes necessary in teaching God’s children.

Proximity of plea and response. As it reads in the canonized scripture, God’s response came immediately after Joseph’s cry (see D&C 121:7–25). In the Liberty letter, however, the response came several paragraphs later.[14] In the noncanonical portion, Joseph mentioned consoling letters received the evening before from his wife, Emma, his brother Don C. Smith, and Bishop Edward Partridge. For Joseph, peace was found in the voices of family and friends, as well as in the voice of God. In many regards, these timely letters helped prepare the way for God’s answer to Joseph’s plea. Joseph conveyed the blessings of friendship as follows: One token of friendship from any source whatever awakens and calls into action every sympathetic feeling; it brings up in an instant everything that is passed; it seizes the present with the avidity of lightning; it grasps after the future with the fierceness of a tiger; it moves the mind backward and forward, from one thing to another, until finally all enmity, malice and hatred, and past differences, misunderstandings and mismanagements are slain victorious at the feet of hope.[15] This portion of the letter also mentions a prerequisite to God’s promise of peace. Placing the canonized portion back into the original sentence, we read: “And when the heart is sufficiently contrite, then the voice of inspiration steals along and whispers, [My son, peace be unto thy soul; thine adversity and thine afflictions shall be but a small moment....]”[16]

We can help our students discover where they fit into this equation. Students can understand that as they extend friendship, their friendly words can help prepare the way for God’s peace to reach others. They can also discover what it means to be “sufficiently contrite” in relation to obtaining personal peace from the Lord.

Another principle we may draw from this text is how and when the Lord grants blessings. In the scriptures, Joseph’s statement “Remember thy suffering saints, O our God” is immediately followed by “My son, peace be unto thy soul” (D&C 121: 6–7). For Joseph, relief did not come immediately, but the promise of relief did come. Elder Jeffrey R. Holland reiterated this: “Some blessings come soon, some come late, and some don’t come until heaven; but for those who embrace the gospel of Jesus Christ, they come.”[17] So it is for all the righteous. In the midst of trials, relief may not be immediate, but it will come.

If you do these things. Doctrine and Covenants 121:26 is the second half of a full sentence in the Liberty letter. Prior to this verse, Joseph chastised the Saints for acting “too low, too mean, too vulgar, too condescending for the dignified characters of the called and chosen of God.” Joseph then exhorted the Saints to “honesty, and sobriety, and candor, and solemnity, and virtue, and pureness, and meekness, and simplicity.” He then promised, “And now, brethren, after your tribulations, if you do these things, and exercise fervent prayer and faith in the sight of God always, [He shall give unto you knowledge by His Holy Spirit, yea by the unspeakable gift of the Holy Ghost....]”[18]

The canonized portion of the letter assures us that God is a revealing God. He desires to give us knowledge “by the unspeakable gift of the Holy Ghost” (D&C 121:26). The noncanonical portion helps us remember to avoid vulgarity and embody solemnity in order to qualify for the gift of the Holy Ghost. As our students face an increasingly vulgar world, it is important for them to remember these principles.

Floodwater. The “rolling waters” imagery of Doctrine and Covenants 121:33 is a paragraph taken from a longer portion in the Liberty letter. The text of the letter employs this imagery much more broadly. The Prophet Joseph first spoke of the filthiness caused by newly rolling water. It was at first full of all kinds of debris and impurities. Then he asked, “How long can rolling water remain impure?” Almost as an answer to his own question, he asked, “What is [Governor] Boggs or his murderous party, but wimbling willows upon the shore to catch the flood-wood?” In Joseph’s time, the knowledge poured from heaven had stirred up rubbish. Notwithstanding, the Prophet knew that the “next surge” of opposition and trial would “bring to [the Saints] the fountain as clear as crystal, and as pure as snow.”[19] He understood that opposition has a purpose in purifying the moving water.

In our time, this principle is still true. As a newly converted individual begins to implement the laws of the gospel in his or her life, opposition is often stirred up. However, as the individual continues in righteousness, that opposition has a purifying effect. Joseph Smith made a simple scientific comparison in the same thought:

As well might we argue that water is not water, because the mountain torrents send down mire and roil the crystal stream, although afterwards render it more pure than before; or that fire is not fire, because it is of a quenchable nature, by pouring on the flood; as to say that our cause is down because renegados, liars, priests, thieves and murderers, who are all alike tenacious of their crafts and creeds, have poured down, from their spiritual wickedness in high places, and from their strongholds of the devil, a flood of dirt and mire and filthiness and vomit upon our heads.

No! God forbid. Hell may pour forth its rage like the burning lava of mount Vesuvius, or of Etna, or of the most terrible of the burning mountains; and yet shall “Mormonism” stand. Water, fire, truth and God are all realities. Truth is “Mormonism.” God is the author of it. He is our shield.[20]

Joseph showed that fighting against something does not destroy the nature of the thing itself. Dirtying water does not wipe out all sources of pure water. Quenching a fire does not eradicate all fire from the face of the earth. Stifling Mormonism in no way defeats the truth of God’s Church or its progress in the years to come. Man’s “puny arm” is indeed feeble when put in this context (D&C 121:33).

One Continuous Thought

In the original text, there is no break between Doctrine and Covenants 121 and122.[21] This would suggest that the prerequisites mentioned in section121 might be applied to the promises of section122. Regarding this continuity, Jessee and Welch stated the following: “The continuity of these passages, blending in and out of each other, raises the interesting possibility, however, that all of the second person pronouns in this text (thee, thy, thou) might refer both to Joseph Smith or Bishop Partridge as well as to all righteous Saints.”[22]

Knowing the continuity of the letter may aid in teaching a few verses that are often skimmed over. When section122 is read alone, the first four verses can be lost in the shadow of the later verses. Many teachers encourage students to insert their own life experiences into Doctrine and Covenants 122:5–9, teaching that our trials “shall give [us] experience, and shall be for [our] good” (D&C 122:7). These are sometimes the only verses covered in this section.

The literary context suggests personal application to the first four verses as well. As we connect the end of Doctrine and Covenants121 with the beginning of Doctrine and Covenants122, we see a conditional promise. If a leader acts in righteousness, with virtuous thoughts and charitable actions (see D&C 121:45), then “the ends of the earth shall inquire after thy name, . . . and the virtuous, shall seek counsel, and authority, and blessings constantly from under thy hand. And thy people shall never be turned against thee” (D&C 122:1–3; emphasis added). The two sections read together lead to application to a broad range of God’s servants.

Principles in the Noncanonical Portions

Understanding the noncanonical text provides readers with clarifying cross-references to the canon. While the following principles have no proximate literary connection to canonized portions, the ideas complement the canon quite well.

Equal to Abraham’s trials. Between verses 25 and 26 of Doctrine and Covenants 121 is a lengthy noncanonical paragraph that has drawn the attention of many historians and scholars.[23] In this paragraph, the Prophet Joseph compared his trial in Liberty Jail to that of Abraham. He wrote, “We think also, it will be a trial of our faith equal to that of Abraham, and that the ancients will not have whereof to boast over us in the day of judgment, as being called to pass through heavier afflictions; that we may hold an even weight in the balance with them.” To some readers, it may seem presumptuous for Joseph Smith to compare his trials so boldly to those of Abraham. However, in the same paragraph, Joseph reminded us, “[God] has chosen His own crucible, wherein we have been tried.”[24] The Prophet was teaching that there is equality between a cold prison and a sacrificial altar because each of us passes through the crucible God has prepared for our own experience and growth.

President Boyd K. Packer identified some modern-day crucibles: “Some are tested by poor health, some by a body that is deformed or homely. Others are tested by handsome and healthy bodies; some by the passion of youth; others by the erosions of age. Some suffer disappointment in marriage, family problems; others live in poverty and obscurity. Some (perhaps this is the hardest test) find ease and luxury. All are part of the test, and there is more equality in this testing than sometimes we suspect.”[25]

This idea could be used when teaching Doctrine and Covenants 122:5–7. Most students have never had “enemies tear [them] from the bosom of [their] wife, and of [their] offspring” (v. 6). The Prophet Joseph did not have the same trials as Abraham, and our students need not have the same trials as either of them. Each individual experiences personalized fires through which God permits him or her to pass. Like Joseph Smith, our students can know that their trials “shall give [them] experience, and shall be for [their] good” (v. 7).

Flattery and exhortation. Also found between verses 25 and 26 of section121 is Joseph’s own proverb. He first quoted Proverbs 16:18, warning that “pride goeth before destruction.” He then offered this thought: “Flattery also is a deadly poison. A frank and open rebuke provoketh a good man to emulation; and in the hour of trouble he will be your best friend.”

Joseph himself practiced this principle. Two paragraphs later he wrote, “We exhort one another to a reformation with one and all, both old and young, teachers and taught, both high and low, rich and poor, bond and free, male and female.”[26] Again, at the end of the Liberty letter, Joseph Smith promised “from henceforth to disapprobate *-everything that is not in accordance with the fullness of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, and is not of a bold, and frank, and upright nature.”[27] Joseph felt an increased need to correct faults—his own and others’. He knew that by doing so, he would strengthen his bonds with the righteous individuals around him.

This principle and example could be used as a clarifying cross-reference for Doctrine and Covenants 121:42–43. These scriptures teach that gentleness, love, and kindness are necessary attributes of a good leader. Some students may mistakenly think that gentleness and love must be shown through overly kind words. Joseph clearly taught, however, that flattery is not a manifestation of kindness; appropriate reproof is.

Aspiring to the Honors of Men

Doctrine and Covenants 121:1–33 was taken from the first part of the Liberty letter. Verse34 and everything after was taken from the second part of the letter dictated a few days later.[28] During the intervening days, the Prophet Joseph received a correspondence from Bishop Edward Partridge in which he learned of some sympathy toward the Saints and of land opportunities in Iowa that would allow the Saints to gather. This may be part of the reason Joseph discussed the ideas presented in Doctrine and Covenants 121:34–40.[29]

Joseph began the second part of the letter in a hopeful tone. He then gave a warning to those who might stand to gain from prospecting in the possible land deal. He enjoined the leaders to be “properly affected one toward another, and... careful by all means to remember, those who are in bondage.” He then wrote, “And if there are any among you who aspire after their own aggrandizement, and seek their own opulence, while their brethren are groaning in poverty, and are under sore trials and temptations, they cannot be benefited by the intercession of the Holy Spirit.”[30]

Earlier letters from Liberty Jail identify Church members guilty of aspiring after their own aggrandizement, thereby disqualifying themselves from the help of the Holy Ghost. In Joseph Smith’s first letter written from Liberty Jail, dated December16, 1838, Joseph chided William E. McLellin and David Whitmer for their recent attempt “to bring into existence a re-organized church with David Whitmer as the president thereof.”[31] In the same letter, Joseph spoke of Dr. Sampson Avard and “many other designing and corrupt characters like unto himself, [who] have been teaching many things which the Presidency never knew were being taught in the Church by anybody until after they were made prisoners.”[32] A few weeks later, Joseph wrote of Isaac Russell, “Russell turned prophet (apostate). He said Joseph had fallen and he was appointed to lead the people.”[33]

When teaching Doctrine and Covenants 121:34–40, a teacher could refer to Whitmer, McLellin, and Russell as case studies. Each of them “aspire[d] to the honors of men” (v. 35) and grieved the Spirit of the Lord because of it (see v. 37). As our students see others who were guilty of self-aggrandizement, we hope they will be less likely to be guilty of it themselves.

Many Teachers but Perhaps Not Many Fathers

There are four short paragraphs between the end of section122 and the beginning of section123. In this portion, Joseph Smith counseled the Saints not to organize in large bodies on common stock principles. He then gave a reason for this instruction, saying, “We have reason to believe that many things were introduced among the Saints before God had signified the times; and notwithstanding the principles and plans may have been good, yet aspiring men... perhaps undertook to handle edged tools.”

To help readers better understand his analogy, the Prophet went on to make a comparison between the Saints and children when he wrote: “Children, you know, are fond of tools, while they are not yet able to use them.” He further advised: “Time and experience, however, are the only safe remedies against such evils. There are many teachers, but, perhaps, not many fathers. There are times coming when God will signify many things which are expedient for the well-being of the Saints; but the times have not yet come, but will come, as fast as there can be found place and reception for them.”[34]

Note Joseph’s distinction between teachers and fathers. In this context, the Prophet seemed to be describing a teacher as one who imparts knowledge to a student as fast as the student can mentally absorb it. A father, understanding the character and nature of the child, imparts knowledge only as the child is ready to use it.

President Boyd K. Packer called this “the principle of prerequisites”: “When, as teachers, we are confronted with difficult questions, we must keep in mind the principle of prerequisites, and if the inquirer has not had the prerequisite courses, then we should start there and give him a brief course in fundamentals. He will learn the answer in no other way.”[35] President Packer referred to a teacher who understands this principle as a “mature teacher.”[36] Joseph Smith referred to a teacher who understands this principle as a “father.” Our Heavenly Father teaches in this way; we would do well to do the same.[37]

A Path of Hope

The vocabulary that Joseph Smith chose to employ at different parts of the Liberty letter reveals a theme. The words and phrases follow a clear path of hope. In the first part of the letter, Joseph began in despair, listing the trouble he and the Saints had experienced and crying out for the help of the Almighty. For the remainder of the letter, the Prophet spoke in a comforting tone concerning the promise of the Second Coming, his escape from prison, friendship, peace, and growth from adversity. He lovingly counseled the Saints to beware of pride and unrighteous aspirations and promised the unspeakable gift of the Holy Ghost. Similarly, in the second part of the letter, Joseph spoke of open doors, intercession, positive lessons gained from negative experiences, and a promise that all things will eventually be for the good of the Saints. He began to close the letter with this canonized verse: “Therefore, dearly beloved brethren, let us cheerfully do all things that lie in our power; and then may we stand still, with the utmost assurance, to see the salvation of God, and for his arm to be revealed” (D&C 123:17).

While at first Joseph descended into the valley of despair, he spent the rest of the document guiding the reader along an upward path of encouragement. He ended the document squarely on the peak of hope and good cheer. The hopeful trajectory of the letter is also seen as one looks at Doctrine and Covenants 121–123 as a whole. The noncanonical text suggests that a reader may do so. From these sections, our students can understand that, like the Prophet Joseph Smith, they can allow the Lord to help them climb out of discouragement into hope.

One way in which Joseph lifts the reader is through a rare, powerful testimony. Toward the end of the first part of the letter, he said simply, “Truth is ‘Mormonism.’ God is the author of it.”[38] According to Jessee and Welch, “This is the only known document in which Joseph Smith bears his personal testimony of these truths so directly.”[39] Again, at the end of the second part of the letter, the Prophet spoke boldly: “We say that God is true; that the Constitution of the United States is true; that the Bible is true; that the Book of Mormon is true; that the Book of Covenants is true; that Christ is true; that the ministering angels sent forth from God are true, and that we know that we have an house not made with hands eternal in the heavens, whose builder and maker is God.”[40] There is no doubt or equivocation in these words. The Prophet Joseph Smith was resolute in what he knew.

Conclusion

For a group of teachers with both the necessity and time to understand the scriptures deeply, the Liberty letter provides an extra layer of insight to Doctrine and Covenants 121–123. While we must be careful not to overemphasize the noncanonical portions, they can provide context and clarity to the principles contained in the scriptures. As we teach the scriptural principles well, our students will be blessed to know and understand the important lessons taught from Liberty Jail.

Notes

[1] History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1980), 3:289.

[2] See Dean C. Jessee and John W. Welch, “Revelations in Context: Joseph Smith’s Letter from Liberty Jail, March 20, 1839,” BYU Studies 39, no. 3 (2000): 125.

[3] Approximately one-third of the text was canonized. There are about 7,450 words in the original letter and about 2,400 words in Doctrine and Covenants 121–23.

[4] See Historian’s Office Journal (January15, 1875),70, located at the Church History Library.

[5] See Doctrine and Covenants Student Manual (Religion 324–325) (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1981),296; Robert J. Woodford, “The Historical Development of the Doctrine and Covenants, Volume III” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1974), 1566–67.

[6] For additional reading on the principles in the Liberty letter, see Jessee and Welch, “Revelations in Context,” 125–45; Keith W. Perkins, “Trials and Tribulations in Our Spiritual Growth: Insights from Doctrine and Covenants 121 and 122,” in The Heavens Are Open: The 1992 Sperry Symposium on the Doctrine and Covenants and Church History (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1993), 278–89. For a historical overview, see Dean C. Jessee, “‘Walls, Grates and Screeking Iron Doors’: The Prison Experience of Mormon Leaders in Missouri, 1838–1839,” in New Views of Mormon History: A Collection of Essays in Honor of Leonard J. Arrington, ed. Davis Bitton and Maurine Ursenbach Beecher (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987), 19–42; Leonard J. Arrington, “Church Leaders in Liberty Jail,” BYU Studies 13, no.1 (1972): 20–26; H. Dean Garrett, “Seven Letters from Liberty,” in Arnold K. Garr and Clark V. Johnson, eds., Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: Missouri (Salt Lake City: Church History Department,1994), 189–200.

[7] History of the Church, 3:289–90.

[8] History of the Church, 3:294.

[9] History of the Church, 3:291.

[10] See Jessee and Welch, “Revelations in Context,”126: “The Prophet’s plaintive plea does not come out of nowhere. It grows out of extraordinary faith, hope, and love, as well as extreme affliction and injustice. The Prophet’s soul-rending petition then provides the text for the first six verses of section121.”

[11] History of the Church, 6:312.

[12] Dallin H. Oaks, “Love and Law,” Ensign, November 2009, 26–29; emphasis and bracketed material in original.

[13] Encyclopedia of Joseph Smith’s Teachings, ed. Larry E. Dahl and Donald Q. Cannon (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000),219.

[14] The cry for peace is found on page3 of the actual document, while the promised peace is on page 8; see Jessee and Welch, “Revelations in Context,” 133,135.

[15] History of the Church, 3:293.

[16] History of the Church, 3:293; emphasis added; bracketed material in original; see also D&C 121:7; Jessee and Welch, “Revelations in Context,”127; Perkins, “Trials and Tribulations in Our Spiritual Growth,”281.

[17] Jeffrey R. Holland, Ensign, November 1999,38; emphasis in original.

[18] History of the Church, 3:296; see also Jessee and Welch, “Revelations in Context,”127.

[19] History of the Church, 3:297.

[20] History of the Church, 3:297.

[21] History of the Church, 3:300.

[22] Jessee and Welch, “Revelations in Context,”129.

[23] History of the Church, 3:294–96; see Jessee and Welch, “Revelations in Context,”127; Perkins, “Trials and Tribulations in Our Spiritual Growth,”283.

[24] History of the Church, 3:294.

[25] Boyd K. Packer, “The Choice,” Ensign, November 1980,21; emphasis added.

[26] History of the Church, 3:295–96.

[27] History of the Church, 3:303.

[28] History of the Church, 3:299–301.

[29] See Jessee and Welch, “Revelations in Context,”128.

[30] History of the Church, 3:299.

[31] History of the Church, 3:228n.

[32] History of the Church, 3:231.

[33] History of the Church, 3:226.

[34] History of the Church, 3:301–2; emphasis added.

[35] Boyd K. Packer, Teach Ye Diligently (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1991), 82–83; see also chapters 11 and 17.

[36] Packer, Teach Ye Diligently, 83.

[37] Isaiah 28:10 is a good starting point in studying this topic.

[38] History of the Church, 3:297.

[39] Jessee and Welch, “Revelations in Context,”130.

[40] History of the Church, 3:304.