The Jerusalem Conference: The First Council of the Christian Church

Frank F. Judd Jr.

Frank F. Judd Jr., "The Jerusalem Conference: The First Council of the Christian Church," Religious Educator 12, no. 1 (2011): 55–71.

Frank F. Judd Jr. (frank_judd@byu.edu) was an associate professor of ancient scripture at BYU when this was written.

Caesarea is where Cornelius received his vision and where Peter taught and baptized the first Gentile converts. Courtesy of David M. Whitchurch.

Caesarea is where Cornelius received his vision and where Peter taught and baptized the first Gentile converts. Courtesy of David M. Whitchurch.

The most famous council of the early Christian Church is probably the Council of Nicaea, which took place in AD 325 in the city of Nicaea, located just south of Constantinople, or modern-day Istanbul, Turkey. At the Council of Nicaea, Christian leaders from all over the Roman Empire convened in order to discuss, among other things, doctrinal issues related to the controversial teachings of Arius, a presbyter or local leader from Alexandria, Egypt. Much of the discussion centered on the views of Arius concerning the nature of Christ as well as the Savior’s precise relationship to the other members of the Godhead: God the Father and the Holy Ghost.[1] This conference resulted in the formulation and distribution of the Nicene Creed.[2] Despite the declarations of the leaders of the Church at that time, doctrinal controversies relating to the teachings of Arius persisted.[3]

The Council of Nicaea, however, was not the first council of the Christian Church. Roughly two decades after the crucifixion of the Savior, leaders of the Church met in Jerusalem to discuss issues relating to the law of Moses, Gentile conversion, and the obligations of faithful members of the Church of Jesus Christ. This council also resulted in the formulation and distribution of important documents—letters announcing the decisions of the council (see Acts 15:23–31). Significantly, even after the leaders of the Church made certain decisions at this conference, questions remained unanswered.

This paper will analyze the Jerusalem Conference. First, I will outline the attitudes toward the law of Moses and Gentiles that led up to the council. Then I will discuss factors of the early Christian proselytizing of Gentiles. Finally, I will investigate the decisions made by the leaders of the Church at this council and their effect upon the remainder of the members of the Church. The leaders were inspired in their council regarding the law of Moses, but followers of Christ still struggled to maintain the proper balance between the doctrine of the Church and the traditions of the Jewish Saints.

The Law of Moses

Jesus Christ is the Lord Jehovah of the Old Testament. When the resurrected Savior appeared to the Nephites, he declared: “I am he who gave the law, and I am he who covenanted with my people Israel” (3 Nephi 15:5; compare Exodus 3:14 and John 8:58). Before the children of Israel received the law of Moses, however, they were offered an opportunity to accept the gospel. The Prophet Joseph Smith taught that “when the Israelites came out of Egypt they had the Gospel preached to them.”[4] Comparing Church members in his own day with the children of Israel, the author of the Epistle to the Hebrews similarly explained, “For unto us was the gospel preached, as well as unto them” (Hebrews 4:2).[5] Referring to crucial information concerning the higher priesthood and ordinances of the gospel, the Lord has told us, “This Moses plainly taught to the children of Israel in the wilderness, and sought diligently to sanctify his people” (D&C 84:23). Jehovah clearly told Moses that the purpose for the escape of the children of Israel from Egypt was “that they may serve me in the wilderness” (Exodus 7:16; see also Exodus 8:1, 20; 9:1, 13; 10:3). This means that the Lord’s original intent was that the Israelites would serve him by receiving and living the fullness of the gospel.

Eventually the Lord gave to Moses two tablets of stone (see Exodus 31:18), upon which was inscribed the gospel. But when Moses descended from Mount Sinai with the tablets, he found the children of Israel rebelling against the teachings they had received, and in his anger Moses broke the original tablets (see Exodus 32:19). When Moses asked Jehovah for another set of tablets, the Lord agreed, but then explained to Moses: “But it shall not be according to the first, for I will take away the priesthood out of their midst; therefore my holy order, and the ordinances thereof, shall not go before them” (Joseph Smith Translation, Exodus 34:1). Thus the first set of tablets contained the gospel of Jesus Christ, including the higher priesthood and ordinances, while the second set contained the law of Moses, which was to be administered by the lower priesthood.

In a revelation to the Prophet Joseph Smith, we are taught about the rebellion of the children of Israel: “But they hardened their hearts and could not endure his presence; therefore, the Lord in his wrath, for his anger was kindled against them, swore that they should not enter into his rest while in the wilderness, which rest is the fulness of his glory. Therefore, he took Moses out of their midst, and the Holy Priesthood also; and the lesser priesthood continued” (D&C 84:24–26).

Though it was the lower law, the law of Moses was nonetheless a binding covenant and an inspired set of commandments written by “the finger of God” (see Exodus 31:18; Deuteronomy 9:10) and given by Jehovah to the children of Israel to teach them about Christ and his gospel.[6] By the time of the New Testament, the importance of the law of Moses was well established among the Jews living in Judaea and Galilee, though at times it was taken by some to the extreme as oral traditions were multiplied and sometimes amplified beyond the original intent of the original law (see Matthew 15:1–6). The seriousness with which many Jews treated the law of Moses is demonstrated in the Gospels by the multiple occasions when groups of Jewish leaders accused Jesus of breaking that law (see Matthew 12:1–2; John 7:49).

It is important to note that during his mortal life, though he did not agree with the oral traditions that Jewish teachers had created over the centuries, Jesus fully supported keeping the actual written law of Moses.[7] For example, the Savior declared to a man he had just healed from leprosy: “Go thy way, shew thyself to the priest, and offer for thy cleansing those things which Moses commanded” (Mark 1:44). Further, in his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus declared, “Whosoever therefore shall break one of these least commandments, and shall teach men so, he shall be called the least in the kingdom of heaven: but whosoever shall do and teach them, the same shall be called great in the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 5:19).[8] The Savior’s own attitude toward the law of Moses had a great effect upon the outlook of the disciples concerning the Mosaic regulations.

Gentiles and the Law

The law of Moses contains certain teachings concerning the relationships between Israelites and non-Israelites. Although Jehovah had strictly charged the children of Israel to avoid worshipping any foreign deities (see Exodus 20:3–5), they were also directed to refrain from mistreating non-Israelites: “Thou shalt not oppress a stranger: for ye know the heart of a stranger, seeing ye were strangers in the land of Egypt” (Exodus 23:9).[9] The Lord declared, however, that Gentiles should not eat of the Passover meal unless the males were circumcised (see Exodus 12:43–48). Further, non-Israelites were forbidden to partake of any priestly sacrificial meals (see Exodus 29:31–33; Leviticus 22:10). But, overall, Israelites were to treat non-Israelites with respect and compassion.

The law of Moses did not forbid association between Israelites and non-Israelites. Following the Babylonian captivity, however, Jewish attitudes toward non-Jews became increasingly skeptical and exclusive, presumably to prevent the kind of foreign religious influences that led to the exile in the first place. For example, a Jewish document entitled Ecclesiasticus, a book of the Apocrypha written around 200 BC, declares, “Receive strangers into your home and they will stir up trouble for you, and will make you a stranger to your own family” (Ecclesiasticus 11:34).[10] Similarly, the Jewish book of Jubilees—probably written in the second century BC—states: “Separate yourself from the gentiles, and do not eat with them, and do not perform deeds like theirs. And do not become associates of theirs. Because their deeds are defiled, and all of their ways are contaminated, and despicable, and abominable” (Jubilees 22:16).[11] By the time of the New Testament, these kinds of negative attitudes toward contact with Gentiles were common in Jerusalem.

When Jesus Christ commissioned his Twelve Apostles, he commanded them, “Go not into the way of the Gentiles” (Matthew 10:5). The Savior, however, never intended the disciples to permanently withhold the gospel from Gentiles, but was informing them that they were not to teach them at that time. Earlier, Jesus had prophesied to a group of Jews in Galilee concerning the faith of a Roman centurion: “Many shall come from the east and west, and shall sit down with Abraham, and Isaac, and Jacob, in the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 8:11). During his mortal ministry, in spite of the temporary prohibition he gave his disciples, the Savior himself blessed the lives of Gentiles (see Matthew 8:5–13; 15:21–28). The inability of some early disciples to accept new revelation concerning the Gentiles, however, would fracture the young Church.

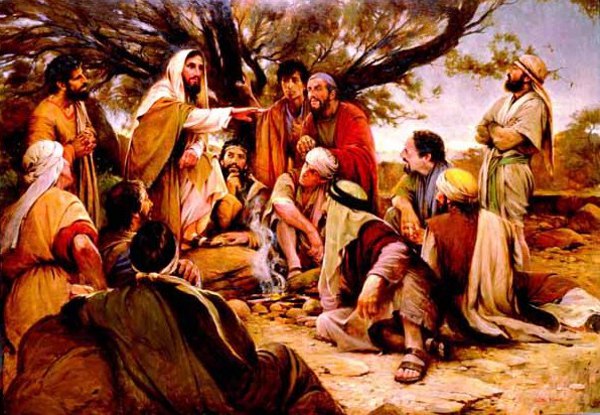

When Jesus commissioned his Twelve Apostles, he commanded them, "Go not into the way of the Gentiles." Walter Rane, These Twelve Jesus Sent Forth, courtesy of Church History Museum.

When Jesus commissioned his Twelve Apostles, he commanded them, "Go not into the way of the Gentiles." Walter Rane, These Twelve Jesus Sent Forth, courtesy of Church History Museum.

Early Apostolic Mission

According to the Gospel of Matthew, the resurrected Lord declared to his disciples: “Go ye therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost” (Matthew 28:19; emphasis added; see also Mark 16:15–16). Following the forty-day ministry, the Savior reminded them, “Ye shall be witnesses unto me both in Jerusalem, and in all Judaea, and in Samaria, and unto the uttermost part of the earth” (Acts 1:8; emphasis added).[12] Possibly because there were Jewish communities scattered all over the Roman world, however, the early disciples did not seem to fully appreciate the significance and scope of the Savior’s declarations until later.[13]

For the earliest Christians, the first opportunities for missionary work were with groups of Jews in and around Jerusalem. These Jewish audiences were taught that Jesus of Nazareth was the true Messiah, was crucified for the sins of the world, and had been resurrected (see Acts 2:21–36; 3:13–26). The precise teachings of these early missionaries about the law of Moses, however, are not as clear. What is clear is that they stirred up controversy. Stephen, for example, was accused of teaching “blasphemous words” concerning the temple and the law of Moses (see Acts 6:11, 13).[14] His accusers stated: “We have heard him say, that this Jesus of Nazareth shall destroy this place [i.e. the temple], and shall change the customs which Moses delivered us” (Acts 6:14).[15] The future tense of the verbs (i.e. “shall destroy” and “shall change”) may indicate that some early disciples, including Stephen, misunderstood the divine timetable in the process of fulfilling the law, supposing that the law of Moses was to be fulfilled at the destruction of the temple, rather than at the death of the Savior.[16] Thus, many of the earliest Jewish Christians were not prepared to allow non-Jewish converts to refrain from the requirements of the law of Moses.

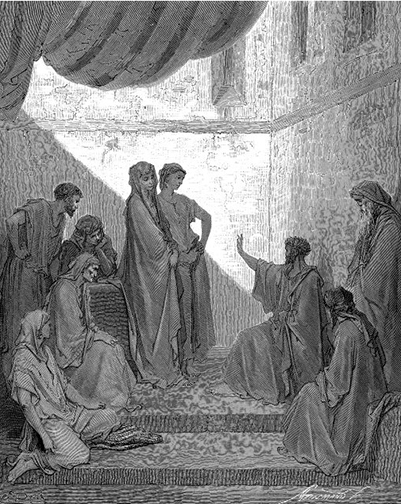

Here the Apostle Peter is shown preaching to Cornelius and his family. Cornelius' conversion was the first time in the early Church that an individual who was not already keeping the law of Moses was allowed to be baptized. Paul Gustave Dore, St Peter in the house of Cornelius.

Here the Apostle Peter is shown preaching to Cornelius and his family. Cornelius' conversion was the first time in the early Church that an individual who was not already keeping the law of Moses was allowed to be baptized. Paul Gustave Dore, St Peter in the house of Cornelius.

Peter’s experience with Cornelius seems to support this conclusion. On one occasion after the resurrection of the Savior, the chief Apostle Peter was visiting his friend Simon in the coastal city of Joppa.[17] While taking a nap on the roof in the middle of the day, Peter had a vision in which he saw a large sheet containing animals that were unclean according to the law of Moses.[18] When a voice commanded him to kill and eat these animals, Peter promptly responded by defending his faithful observance of the law of Moses: “Not so, Lord; for I have never eaten any thing that is common or unclean” (Acts 10:14). The voice then declared to Peter: “What God hath cleansed, that call not thou common” (Acts 10:15). This experience was repeated three times.[19]

At first, “Peter doubted in himself what this vision which he had seen should mean” (Acts 10:17). But before his arrival at the coastal city of Caesarea, the true meaning of his dream—that it was about people, not animals—was revealed to Peter. When the sincere Gentile Cornelius greeted the faithful Jewish Peter, he “fell down at [Peter’s] feet, and worshipped him” (Acts 10:25). Peter acknowledged the Jewish cultural taboo concerning interaction between Jews and non-Jews, but then declared emphatically: “But God hath shewed me that I should not call any man common or unclean” (Acts 10:28). Peter taught a radical new perspective to those who were present in Caesarea: “God is no respecter of persons: But in every nation he that feareth him, and worketh righteousness, is accepted with him” (Acts 10:34–35). The Lord had previously sent an angel to Cornelius, preparing him to receive the good news from Peter (see Acts 10:1–8, 30–33). After listening to Peter, many of the Gentiles who were present were filled with the Holy Ghost (see Acts 10:44–46). Peter then took those Gentiles who believed and “commanded them to be baptized in the name of the Lord” (Acts 10:48).

The conversion of Cornelius is extremely important. Before this point in the history of the early Church, all Christians were either Jews, who were already keeping the law of Moses, or “proselytes”—Gentiles who had previously converted to Judaism and were also keeping the law of Moses at the time they became Christians.[20] Cornelius is identified as “a devout man, and one that feared God” (Acts 10:2). The descriptions “devout” and “God fearer” seem to be “quasi-technical phrases” that refer to Gentiles who were sympathetic toward Judaism and worshipped Jehovah, but were not keeping the regulations of the law of Moses, especially that of circumcision.[21] Jewish Christians were “astonished” (Acts 10:45) because the gifts of the Spirit were shared with those whom many considered their enemies. Thus Cornelius’ conversion was the first time in the early church that an individual who was not already keeping the law of Moses was allowed to be baptized.[22]

Given the importance that most early Jewish Christians placed upon faithful observance of the law of Moses, it should come as no surprise that some Jewish members of the Church reacted less than enthusiastically to the news of Cornelius’ baptism. When Peter arrived in Jerusalem, Jewish Christians “contended with him” (Acts 11:2) because of his association with Gentiles.[23] Peter defended himself by recounting the details of the dream he received from God and bore his solemn witness that “God gave [the Gentiles] the like gift as he did unto us, who believed on the Lord Jesus Christ; what was I, that I could withstand God?” (Acts 11:17).[24] Many in the audience “glorified God” (Acts 11:18) because of the new revelation, but as we will see, resistance from Jewish Christians continued.[25]

The Council Proceedings

While Paul and Barnabas were in Asia Minor on their first mission, they experienced some success among groups of non-Jews (see Acts 13:7, 42, 48; 14:1, 21–23). When they returned to their headquarters in Antioch of Syria, Paul and Barnabas testified that God “had opened the door of faith unto the Gentiles” (Acts 14:27). While in Antioch, groups of Jewish Christians visiting from Judea were teaching the false doctrine, “Except ye be circumcised after the manner of Moses, ye cannot be saved” (Acts 15:1).[26] Paul and Barnabas “had no small dissension and disputation with them” (Acts 15:2).[27] After Paul received “revelation” on the matter (Galatians 2:2), he and the Christians in Antioch were convinced that he “should go up to Jerusalem unto the apostles and elders about this question” (Acts 15:2).[28]

In about AD 49 or 50, Paul and Barnabas traveled from Antioch to Jerusalem to meet with other leaders of the Church concerning whether Gentile converts should be compelled to keep the law of Moses.[29] Along the way, Paul and Barnabas met with groups of Christians and were favorably received when they preached about “the conversion of the Gentiles” (Acts 15:3). Paul brought with him a new Gentile convert by the name of Titus, who had joined the Church but had not undergone circumcision (Galatians 2:1–3). Titus seems to have been brought along to encourage the leaders of the Church to make a firm decision on the matter: here was an uncircumcised Gentile Christian—how would Peter and the Jewish Christians in Jerusalem respond toward him?[30]

The council was attended by a number of those who “were of reputation” within the Church at Jerusalem (Galatians 2:2), including “apostles and elders” (Acts 15:4). Paul and Barnabas were the first to speak, and they shared with the audience the success they had experienced among the Gentiles during their mission (see Acts 15:4). In his letter to the Galatians, Paul indicated that the Church leaders in attendance at this meeting recognized the inspiration of his mission to the Gentiles (see Galatians 2:7). Jewish Christians who had been Pharisees, however, interjected that “it was needful to circumcise them, and to command them to keep the law of Moses” (Acts 15:5). The leaders at the council discussed the issue with no immediate resolution (see Acts 15:6–7).

Peter, who was the leader of the Church, arose and reminded those who were present of his revelation concerning Gentiles and the prophetic interpretation of his dream—that God “put no difference between us and them, purifying their hearts by faith” (Acts 15:9). He then bore his witness that “through the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ we shall be saved, even as they” (Acts 15:11). Peter likened the requirement to keep the regulations of the law of Moses unto a burdensome “yoke upon the neck of the disciples, which neither our fathers nor we were able to bear” (Acts 15:10). Following this, Paul and Barnabas addressed the audience a second time and reinforced Peter’s declaration by recounting the “miracles and wonders God had wrought among the Gentiles by them” (Acts 15:12).

The final speaker at the meeting was James, the brother of Jesus.[31] By the time of the Jerusalem Council, Paul recognized James as one of the “pillars” (Galatians 2:9) or leaders of the Church alongside Peter and John.[32] While Peter was the overall leader of the early Church, James seems to have been functioning as the local leader of the branch of Jewish Christians in Jerusalem.[33] James acknowledged Peter’s experiences concerning the Gentiles and declared that they fulfilled Amos’s prophecy that non-Israelites would seek after the truth of the Lord (compare Acts 15:16–17 with Amos 9:11–12). Thus, following the testimonies of Paul, Barnabas, Peter, and James, the stage was set for the important verdict.

The Decision of the Council

After the leaders had discussed their views on the matter, James announced the decision of the council.[34] One might have expected Peter, the chief Apostle and leader of the entire Church, to be the one to make the announcement. But recall that Peter’s reputation had suffered because of his association with Cornelius and other Gentiles at Caesarea (see Acts 11:1–4). In addition, James was the leader of the Jerusalem branch, many of whom seem to have been in attendance (see Acts 15:4, 22). Therefore, James was the logical choice to deliver the decision of the council. It is likely that the Jewish Christians would be more willing to accept whatever verdict was given if it came from their own respected leader.

James charged the Jewish Christians to “trouble not them, which from among the Gentiles are turned to God” (Acts 15:19). This first expression may have initially sounded like a complete victory for the Gentile Christians—freedom from all the requirements of the law of Moses. But then James clarified the decision, stating that Gentiles should “abstain from pollutions of idols, and from fornication, and from things strangled, and from blood” (Acts 15:20). These rules are not just random moral obligations—they are all regulations from the law of Moses.

The term “fornication” is a translation of the Greek word porneia. It is used in the Septuagint—or Greek version—of Leviticus 18:6–18 to describe various types of prohibited sexual unions.[35] The other three prohibitions are from Leviticus 17:8–15 and describe requirements for non-Israelites who were living among Israelites.[36] Such individuals were required to worship the Lord Jehovah rather than false idols (see Leviticus 17:8–9), abstain from eating animals that had not been properly or ritually prepared and drained of their blood (i.e. “strangled”) (see Leviticus 17:13–15), and refrain from ingesting animal blood (see Leviticus 17:10–12). According to Paul, the leaders in Jerusalem also asked Paul “to remember the poor” (Galatians 2:10), which, Paul affirmed, he was already eager to do. Both Paul and Barnabas had already been active in gathering assistance for those in need at Jerusalem (see Acts 11:29–30).

Thus, while Gentile Christians were not forced to submit to circumcision, they were expected to keep four regulations from the law of Moses. This is important because it is sometimes thought that the law of Moses was completely rescinded, but such is not the case.[37] The decision of the leaders at the Jerusalem Conference was ratified by the Holy Ghost (see Acts 15:28), but it was, in essence, a concession.[38] The Jewish Christians, on the one hand, wanted the Gentile members to be required to keep the entire law of Moses. The Gentile Christians, on the other hand, desired complete freedom from Mosaic regulations, especially circumcision. The leaders settled upon an inspired solution which, they hoped, would appease both sides.[39]

The limited scope of this concession, however, is sometimes overlooked. While Gentile converts would not be required to undergo circumcision or keep all aspects of the Mosaic law, it is important to note that the council made no declaration concerning whether or not Jewish Christians needed to continue keeping the law of Moses. This compromise permitted the Jewish Church members to maintain their previous practice of following the Mosaic regulations if they desired.[40] In fact, there is evidence in the Book of Acts that Jewish Christians continued to keep aspects of the law of Moses well after the Jerusalem Council.[41] The decision at the conference addressed only the relationship of Gentile Christians—not Jewish Christians—to the Mosaic law.

Since Peter knew that the law of Moses was not necessary for salvation—for either Jew or Gentile—why did the Church leaders not come down more firmly on this important issue? Why did they not simply declare the truth and let the consequences follow? Robert J. Matthews has suggested a number of possibilities: “Perhaps they hoped to avoid dividing the Church and alienating the strict Jewish members. Likewise, they would not have wanted to invite persecution from nonmember Jews. . . . By wording the decision the way they did, the Brethren probably avoided a schism in the Church and no doubt also the ire that would have come from the Jews had the decision been stronger. There must have been many who preferred a stronger declaration, but the Brethren acted in the wisdom requisite for their situation.”[42]

In order to inform the general membership of the Church of the council’s decision, the leaders composed a letter contradicting the previous teachings of the Jewish Christians and announcing the new policy.[43] This letter read in part: “We have heard, that certain [men] which went out from us have troubled you with words, subverting your souls, saying, Ye must be circumcised, and keep the law, . . . [but] we gave no such commandments” (Acts 15:24).[44]

In addition, in order to help reassure these Christians that the letter contained a genuine pronouncement and it was not a fraud, the leaders sent “chief men among the brethren” (Acts 15:22), named Judas Barsabas and Silas, to accompany Paul and Barnabas and act as witnesses of the decision of the council.[45]

Reactions and Results

Apparently, not all Jewish Christians readily accepted the ruling of the Jerusalem Council. At some point after it took place, Peter and Paul were eating with some Gentile converts in Antioch when a group of Jewish Christians arrived from Jerusalem.[46] Peter, the head of the Church, “withdrew and separated himself” (Galatians 2:12) because, in the opinion of Paul, he feared the disapproval of the Jewish Christians, who viewed eating with Gentiles as violating the law of Moses (see Galatians 2:12).

Paul was upset because Peter’s actions were having a negative effect upon those who were present, including Paul’s close friend and companion Barnabas (see Galatians 2:13). Paul felt that the example of Peter would completely undermine the decisions that had been made at the Jerusalem Conference and influence Gentiles to think they needed to “live as do the Jews” (Galatians 2:14), probably meaning to submit to the regulations of the Mosaic law. Paul likened these Jewish Christians unto “false brethren” whom he felt, in essence, were attempting to once again bring non-Jews into spiritual bondage by requiring them to keep the Jewish law (Galatians 2:4). In response to this issue, Paul boldly testified concerning the true relationship between salvation and keeping the law of Moses: “A man is not justified by the works of the law [of Moses], but by the faith of Jesus Christ, even we have believed in Jesus Christ, that we might be justified by the faith of Christ, and not by the works of the law [of Moses]: for by the works of the law [of Moses] shall no flesh be justified” (Galatians 2:16).[47]

One may wonder why Peter, who had recently received an important revelation concerning Gentiles, who had authorized the baptism of the Gentile Cornelius, and who had testified at the Jerusalem Conference, would respond this way. In defense of the chief Apostle, however, one should recall that Peter was the leader of a relatively small church that was composed of two emotionally fragile factions; the situation was delicate. The Jewish Christians, on the one hand, did not appreciate the reluctance of some Gentiles to submit to the regulations of the Mosaic law, especially circumcision. Paul and his followers, on the other hand, were not worried about offending the feelings of the Jewish Christians who still held fast to the traditions of the law of Moses. Peter the prophet, naturally, loved and was concerned about both Jewish and Gentile members of the Church.

It was a no-win situation for Peter. If he continued eating with the Gentiles, he would offend the visiting group of Jewish Christians. If he departed, he would offend Paul and the Gentile Christians in Antioch. No compromise was possible. Either way, he was going to hurt some feelings. Maybe Peter felt that an offended Paul would still remain true, while an offended group of Jewish Christians would potentially influence many others to dissent or leave the young church.[48] In any case, Peter chose to leave. The ambiguity of Jewish Christian attitudes toward the law of Moses would unfortunately continue for decades.[49]

Conclusion

There are lessons that one can learn from this interesting episode in earliest Christian history. First, as Robert J. Matthews has pointed out, there can be “a conflict between culture and doctrine.”[50] Because the law of Moses had been the central feature of Jewish life for over one thousand years it was extremely difficult to give up even after it was fulfilled in Christ. Applying the lessons learned from the Jerusalem Council, Elder Spencer J. Condie observed, “Sometimes cultural customs obfuscate eternal principles.”[51] Indeed, true disciples of Jesus Christ must be willing and able to give up long-held traditions when they conflict with living the principles of the gospel.

Second, the events associated with the Jerusalem Council clearly demonstrate the necessity of having a living prophet to receive continuing revelation and teach the will of God concerning current circumstances. Richard Lloyd Anderson explained, “The apostles were inspired to go beyond the Bible, to reverse the lesser law given earlier and to extend the higher law through Christ. In other words, not past scripture but new revelation was the foundation of the Church of Christ.”[52] This is a fundamental truth of the restored gospel. As Elder Dallin H. Oaks taught, “For us, the scriptures are not the ultimate source of knowledge, but what precedes the ultimate source. The ultimate knowledge comes by revelation,” particularly through those we sustain as prophets, seers, and revelators.”[53] The Lord himself has declared to his Saints in the latter days: “Whether by mine own voice or the voice of my servants, it is the same” (D&C 1:38). Obedience to the teachings of living prophets and apostles is always the safest path as we face decisions concerning our own cultural or traditional preferences and the revealed will of God.

Notes

[1] See Justo L. González, The Story of Christianity (Peabody, MA: Prince Press, 1999), 158–67.

[2] For the creed and canons of the Council of Nicaea, see Bart D. Ehrman and Andrew S. Jacobs, Christianity in Late Antiquity 300–450 C.E. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 251–56.

[3] See W. H. C. Frend, The Early Church (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1982), 146–58.

[4] Joseph Fielding Smith, ed., Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 60. See also Larry E. Dahl and Donald Q. Cannon, eds., Encyclopedia of Joseph Smith’s Teachings (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 301.

[5] On issues relating to the authorship of Hebrews, see Terrence L. Szink, “Authorship of the Epistle to the Hebrews,” in How the New Testament Came to Be, ed. Kent P. Jackson and Frank F. Judd Jr. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006), 243–59.

[6] Paul taught that the law of Moses was “ordained by angels in the hand of a mediator” and was “our schoolmaster to bring us unto Christ” (Galatians 3:19, 24).

[7] The law of Moses was not fulfilled at the birth of Jesus Christ, but rather at his death. Therefore, disciples of Christ were obligated to keep the law of Moses during the mortal ministry of the Savior (compare 3 Nephi 1:23–25 with 3 Nephi 9:17–20). The Savior’s attitude toward the oral traditions, which some Jews felt were equally as binding as the written law, is illustrated in Matthew 15:1–6.

[8] The Joseph Smith Translation includes the following statement: “Whosoever shall do and teach these commandments of the law until it be fulfilled, the same shall be saved . . . in the kingdom of heaven” (JST, Matthew 5:121; emphasis added). For a convenient collection of all the JST changes in the New Testament, see Thomas A. Wayment, ed., The Complete Joseph Smith Translation of the New Testament (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005).

[9] See also Exodus 22:21, Leviticus 19:33–34, and Deuteronomy 10:18; 23:7; 24:14. Israelites were also to allow Gentiles to rest on the Sabbath (see Exodus 23:12 and Leviticus 25:6), to glean the leftovers from the field (see Leviticus 19:10; 23:22 and Deuteronomy 24:19–21), to receive protection in any city of refuge (see Numbers 35:15), to be judged fairly according to the law (see Deuteronomy 1:16; 27:19), and to receive welfare support from the annual tithes (see Deuteronomy 14:28–29; 26:12).

[10] This document is also known as the Wisdom of Jesus ben Sirach. Translation is from Michael Coogan, ed., The New Oxford Annotated Apocrypha, 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001).

[11] English translation is from O. S. Wintermute, “Jubilees,” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, ed. James H. Charlesworth (New York: Doubleday, 1985), 2:98.

[12] The Old Testament also contains prophecies that the message of Jehovah would eventually be received by non-Israelites (see, for example, Matthew 4:14–16, which quotes Isaiah 9:1–2).

[13] For example, the resurrected Savior…..to the Nephites, concerning his teaching to the Jews in John 10:16: “They understood not that the Gentiles should be converted through their preaching” (3 Nephi 15:22).

[14] Peter was similarly accused. See, for example, Acts 10:28 and 11:2.

[15] The Savior himself and the Apostle Paul were similarly accused (see Matthew 26:59–61; Mark 14:55–58; Acts 21:28 and 25:7–8).

[16] Jeffrey R. Chadwick has proposed that the Savior never taught the Jewish Christians to stop keeping the law of Moses (see “What Jesus Taught the Jews about the Law of Moses,” in The Life and Teachings of Jesus Christ: From the Transfiguration through the Triumphal Entry, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Thomas A. Wayment [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006], 176–207). Most Latter-day Saint scholars, however, interpret such passages as JST, Matthew 5:19, Alma 25:15, Alma 34:13–14, 3 Nephi 9:17–20, 3 Nephi 15:3–8, Moroni 8:8, and Galatians 3:24–25 to refer to all followers of Christ, regardless of their lineage.

[17] It is extremely difficult to date these events with precision. Acts 1 begins forty days after the crucifixion of the Savior (c. AD 30–33) and Acts 12 describes how James was martyred shortly before the death of Herod Agrippa I (c. AD 44). Therefore Peter’s vision occurred somewhere in the late 30s or early 40s. It is interesting to note that Simon was a tanner (see Acts 9:43)—a man who worked with animal hides to sell the leather. The law of Moses forbade contact with the carcasses of certain dead animals (see, for example, Leviticus 11:24–40). Thus, tanners not only were generally looked down upon in Jewish society, but also would have been ritually unclean according to the law of Moses (see C. K. Barrett, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles [Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1994], 1:486–87; F. F. Bruce, The Book of the Acts, rev. ed. [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1988], 200).

[18] See Acts 10:9–12. See Leviticus 11:1–47 for these kosher food laws.

[19] Note also the threefold repetition of Moroni’s appearance to Joseph Smith (see Joseph Smith—History 1:30–47). The Prophet Joseph Smith stated that such repetition left very deep impressions upon his mind (see Joseph Smith—History 1:46). It is possible that Peter’s dream was also repeated to achieve such lasting impressions.

[20] There were proselytes in the audience on the Day of Pentecost (see Acts 2:10) who may have heeded Peter’s call to be baptized (see Acts 2:38, 41). Nicolas, one of the “seven men of honest report” (Acts 6:3) who were given the responsibility to oversee the temporal welfare of “the Grecians” (Acts 6:1), or Greek-speaking members of the Church, is specifically identified as “a proselyte of Antioch” (Acts 6:5). Robert J. Matthews, “The Jerusalem Council,” in Sperry Symposium Classics: The New Testament, ed. Frank F. Judd Jr. and Gaye Strathearn (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University: 2006), 257.

[21] Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Acts of the Apostles (Doubleday: New York, 1998), 449–50. See also F. F. Bruce, The Acts of the Apostles: Greek Text with Introduction and Commentary, 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1990), 252–53.

[22] Robert J. Matthews stated: “Cornelius is a good man, an Italian, and a soldier, but he is not a proselyte to Judaism. . . . This is the first clear case of a Gentile coming into the Church without having first complied with the law of Moses through circumcision and so forth” (“The Jerusalem Council,” 258).

[23] See Acts 11:3. These Jewish Christians who defended keeping the law of Moses are sometimes called “Judaizers” by modern scholars.

[24] Similarly, after the prophet Wilford Woodruff announced that the practice of plural marriage was being rescinded, he testified: “I should have let all the temples go out of our hands; I should have gone to prison myself, and let every other man go there, had not the God of heaven commanded me to do what I did do” (Deseret Weekly, November 14, 1891; excerpt reprinted following Official Declaration 1 in the Doctrine and Covenants).

[25] There were a number of Jewish Christians who would continue to go forth “preaching the word to none but unto the Jews only” (Acts 11:19).

[26] Elder Bruce R. McConkie pointed out, “This is not circumcision as an operation for reasons of health or personal hygiene, but circumcision as a saving ordinance, as a part of the plan of salvation” (Doctrinal New Testament Commentary [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1971], 2:139). Richard Lloyd Anderson stated, “Circumcision symbolized this issue, but Judaizers were talking about hundreds of obligations beyond circumcision” (Understanding Paul, 2nd ed. [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2007], 50). In sum, as Robert J. Matthews taught, “The manner in which the word circumcised is used throughout the book of Acts and the Epistles is generally as a one-word representation for the entire law of Moses; hence when the Jewish members of the Church insisted that Gentiles be circumcised, they meant that the Gentiles should obey all the law of Moses” (“The Jerusalem Council,” 260–61; emphasis in original).

[27] It is not necessary to suppose that these Judaizers were evil. As Sidney B. Sperry taught, they “were in most respects good Church members,” and they “were simply a party of otherwise good men who needed a considerably broader and more accurate outlook on the teachings of Christianity” (Paul’s Life and Letters [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1955], 55).

[28] A minority of scholars feel that Paul’s epistle to the Galatians should be dated before the Jerusalem Council in Acts 15, and therefore Galatians 2 does not describe Paul’s view on the proceedings of that conference. See, for example, Ben Witherington III, Grace in Galatia: A Commentary on St. Paul’s Letter to the Galatians (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998), 8–20. Most scholars, however, conclude that Galatians was written after the Jerusalem Council and therefore Galatians 2 contains Paul’s perspective on that council (see James D. G. Dunn, Christianity in the Making, vol. 2: Beginning from Jerusalem [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008], 446–47).

[29] The arguments concerning the date of the Jerusalem Council are complex. Most scholars estimate that it took place around AD 49 or 50. On this issue see J. Louis Martyn, Galatians (New York: Doubleday, 1997), 180–82; and Matthews, “The Jerusalem Council,” 263.

[30] Sidney B. Sperry referred to Titus as a “test case” (Paul’s Life and Letters, 59).

[31] James was technically the half-brother of Jesus. According to the Gospel of John, the brothers of Jesus did not believe in Jesus during his mortal ministry (see John 7:5). See also Mark 3:21, where “his friends” should probably be translated as “his family.” Later, the resurrected Savior appeared to his brother James (see 1 Corinthians 15:7). On this, see Gerald N. Lund, “I Have a Question,” Ensign, September 1975, 36–37. The brothers of Jesus were included among those who were praying with Mary the mother of Jesus after the Resurrection (see Acts 1:14). Paul refers to James as an Apostle (see Galatians 1:19).

[32] James, the brother of John, had been martyred earlier by the order of Herod Agrippa I (see Acts 12:1–2).

[33] There are a number of early Christian traditions which claim that James was made “bishop” of Jerusalem. For references, see Glenn A. Koch, “James,” in Encyclopedia of Early Christianity, ed. Everett Ferguson, 2nd ed. (New York: Garland Publishing, 1998), 604. See also Thomas A. Wayment, From Persecutor to Apostle: A Biography of Paul (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006), 98–99.

[34] Compare Acts 15:13 (“James answered . . .”) with Acts 15:19: (“My sentence is . . .”).

[35] See Lancelot C. L. Brenton, The Septuagint with Apocrypha: Greek and English (Hendrickson: Peabody, Mass, 1986), 152–53. Similarly, Paul uses the term porneia in 1 Corinthians 5:1 to refer to illicit sexual relations.

[36] See Leviticus 17:8: “Whatsoever man there be of the house of Israel, or of the strangers which sojourn among you” (emphasis added).

[37] See Wayment, From Persecutor to Apostle, 104.

[38] Elder Dean L. Larsen called the decision “a compromise” (“Some Thoughts on Goal-Setting,” Ensign, February 1981, 64). Similarly, Robert J. Matthews called it “a half step forward” (“The Jerusalem Council,” 263).

[39] Sidney B. Sperry taught that “Paul would, of course, have no objection to the prohibitions added at the end of the letter [i.e. the announcement of the decision], since they involved no important principles for which he had fought so hard” (Paul’s Life and Letters, 61).

[40] See Larsen, “Some Thoughts on Goal-Setting,” 64; see also Anderson, Understanding Paul, 51; Matthews, “The Jerusalem Council,” 263; Sperry, Paul’s Life and Letters, 63; and Wayment, From Persecutor to Apostle, 104.

[41] When Paul visited Jerusalem in Acts 21, possibly around a decade after the decision made at the Jerusalem Council, James informed him that there were still “thousands” of Jewish Christians who were “zealous of the law” (Acts 21:20). For further references, see Chadwick, “What Jesus Taught the Jews about the Law of Moses,” 183–88.

[42] Matthews, “The Jerusalem Council,” 264; see also D. Kelly Ogden and Andrew C. Skinner, Verse by Verse: Acts through Revelation (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006), 75–76; and Wayment, From Persecutor to Apostle, 103.

[43] Similarly, when plural marriage was rescinded during the administration of Wilford Woodruff and when the priesthood was extended to all worthy males during the presidency of Spencer W. Kimball, the First Presidency issued letters announcing the revelations and the new policies. For excerpts of these letters, see Official Declarations 1 and 2 in the Doctrine and Covenants.

[44] At a later point in the narrative, Luke, the writer of Acts, refers to these letters as “decrees” (Acts 16:4). The Greek word translated as “decree” is the same word that Luke uses elsewhere (e.g., Luke 2:1 and Acts 17:7) when describing “official edicts of the Roman Emperor” (Anderson, Understanding Paul, 52).

[45] See Acts 15:22, 25, 27. The issue of forgery was a real one even during this early period. Paul warned the Thessalonian Christians: “Be not soon shaken in mind, or be troubled, neither by spirit, nor by word [or rumor], nor by letter as from us” (2 Thessalonians 2:3; emphasis added). Some person had apparently forged a letter in the name of Paul (i.e., as if from Paul).

[46] See Galatians 2:12. This likely included partaking of the sacrament of the Lord’s supper. On this, see F. F. Bruce, The Epistle to the Galatians: A Commentary on the Greek Text (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1982), 129; and Martyn, Galatians, 232.

[47] For an in-depth study of the proper balance between faith and works, see Stephen E. Robinson, Believing Christ (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992).

[48] Sidney B. Sperry suggested that Peter “may have recognized in the party certain weak persons whose faith could be hurt if they discovered their great leader’s close and continued association with the Gentiles” (Paul’s Life and Letters, 64).

[49] Robert J. Matthews observed, “In avoiding a major division in the Church, they also created in effect two types of practice within the Church: the Jewish practice with the law of Moses, and the Gentile practice without the law of Moses” (Behold the Messiah: New Testament Insights from Latter-day Revelation [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1994], 306).

[50] Matthews, “The Jerusalem Council,” 265.

[51] Spencer J. Condie, Your Agency: Handle with Care (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1996), 51.

[52] Anderson, Understanding Paul, 51.

[53] Dallin H. Oaks, “Scripture Reading and Revelation,” Ensign, January 1995, 7.