Angels in the Age of Railways

Steven C. Harper

Steven C. Harper, "Angels in the Age of Railways," Religious Educator 11, no. 3 (2010): 39–57.

Steven C. Harper (steven_harper@byu.edu) was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this was written. Address at a BYU conference on religious authority April 8, 2006.

"While we were...praying and calling upon the Lord, a messenger from heaven descended in a cloud of light, and having laid his hands upon us, he ordained us" (Joseph Smith-History 1:68). Del Parson.

"While we were...praying and calling upon the Lord, a messenger from heaven descended in a cloud of light, and having laid his hands upon us, he ordained us" (Joseph Smith-History 1:68). Del Parson.

For nearly two millennia, meetings have convened to discuss authority in Christian traditions. For nearly two centuries, such meetings have involved Latter-day Saints. One of these meetings took place in Burslem, England, in 1842 at the behest of Brabazon Ellis, incumbent of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. He invited Alfred Cordon, a lay Mormon minister, to discuss authority in Christian traditions. Each man brought a companion, “and after the usual compliments,” they all knelt as Ellis prayed that the Lord would enlighten each of them. Cordon voiced a heartfelt “amen” and then fielded Ellis’s first question:

He asked me who ordained me in the Church of Latter Day Saints. I told him Wm Clayton. I then said and Sir, Who ordained you. He answered The Bishop. He then asked me who ordained Wm Clayton. I answered Heber C Kimball. I then asked him who ordained the Bishop. He answered: Another Bishop. He then asked me who ordained Heber C. Kimball; I answered Joseph Smith and said I: Joseph Smith was ordained by Holy Angels that were sent by commandment from the Most High God. I asked him from what source the Ministers of the Church of England obtained authority. He answered from the Apostles.

Ellis offered Brother Cordon a book to establish his claim to apostolic succession, and Cordon accepted and promised to read it diligently. Then Ellis asked Cordon to “work him a miracle.” Cordon “asked him whether he was a believer and a Minister of Christ. He answer[ed] that he was.” “Show me a miracle and then I will believe it,” Cordon replied. From there the conversation touched on several controversies of Christian history and doctrine. Each man asserted authority for his positions. Each arrived at his assumptions and conclusions through different epistemologies. Cordon wrote that afterward “we wished him good night and walked to our own homes, more confirmed in the faith of Latter Day Saints than ever.”[1]

I examine the question of authority in Christian traditions with the same assumptions that Alfred Cordon took to his encounter with Brabazon Ellis. I approach my task as an historian who believes that divine authority is vested in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and as one who is willing to openly investigate all other claims with diligence. I recognize, as Joseph Smith put it, that “it may seem to some to be a very bold doctrine that we talk of” (D&C 128:9). Given that bold doctrine, my words may sound apologetic or combative to some. That is not my intention. My desire is to explicate Mormonism’s historical claims to divine authority along with a particularly Mormon epistemology. I will put my faith on display for examination, leaving judgment about its merits or weaknesses to readers.

Long before he was a Mormon invited to meet with Brabazon Ellis, Alfred Cordon avidly read the Bible. He was brought up in the Church of England and “in the fear of God.” As a young apprentice in the Staffordshire potteries, Cordon went from one post to another. He married in 1836 but “led a desolate life.” “I was troubled again and again on account of my sins,” he wrote, “but I would not begin to serve God.” Then his infant daughter “took very ill with convulsions” and died in agony in early 1837, spurring Alfred to “pray to the Lord to direct me and to have mercy upon me.” He did. Shortly after the Cordons buried their daughter, members of Robert Aitken’s short-lived Christian Society visited and discussed religion. “I was quite willing to give up my sins and do anything to find salvation,” Cordon wrote. Though he was a bit shocked by what he called the “terrible noise” of an enthusiastic Christian Society prayer meeting, Cordon nevertheless “came home rejoicing in God my Savior and my Redeemer.” He devoted himself to the Christian Society and became a class leader; his wife “yielded and was made happy” also.[2]

About this same time, a Mormon woman named Mary Powel told Cordon that “the Lord had set his hand again the Second Time to recover the remnant of his people . . . and that the Angel spoken of” in Revelation 14 had come, bringing “the Everlasting Gospel once more unto lost man.” Cordon rejoiced, for, as he wrote,

I had many times prayed for this time to come. We began to talk about the Ordinances of the Gospel and I found that I was standing upon the Precepts of Men and not on the pure word of God. Away I went to my Bible and to prayer. The Spirit of God bore testimony to the truth of what she said. We conversed about the Baptism of Christ. I saw plainly it was by Immersion. Without hesitation I made up my mind in spite of all other things I would obey the Gospel. As soon as the Atkinites heard that I Had been with her they came unto me to try if they could stop me but it was all in vain.

Cordon’s friends told him that Latter-day Saints were “money diggers, gypsies, fortune tellers and anything but a good report.” But Cordon wanted to talk about baptism. Was it essential for salvation? It was not, Reverend Staley declared.[3]

The next morning Cordon set out on foot for Manchester to be baptized by David Wilding, an elder in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Wilding immersed Cordon and soon thereafter laid hands on him to confirm Cordon a member of the Church and invite him to receive the gift of the Holy Ghost. A few weeks later, Mormon leader William Clayton baptized and confirmed several others, Cordon noted, and “he ordained me to be a Priest” by the laying on of hands. “I commenced preaching,” Cordon wrote; and he never stopped, but “went on laboring in the cause of God preaching and baptizing.”[4]

What does this mean? What in the teachings of the Mormon woman Mary Powel was so compelling to Alfred Cordon, and how did he come to know it for himself? Why would he walk to Manchester to be baptized and confirmed by a Mormon elder? What was it about Alfred Cordon’s ordination that turned him from a teacher whose authority was grounded in knowledge of the Bible into a minister with authority to baptize others by immersion for the remission of their sins, an ordinance in which he would pronounce the words “Having been commissioned of Jesus Christ, I baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost”? (D&C 20:73).

Latter-day Saints believe “that a man must be called of God, by prophecy, and by the laying on of hands by those who are in authority, to preach the Gospel and administer in the ordinances thereof” (Articles of Faith 1:5). “By what authority?” one may justifiably ask, as the chief priests and elders did of Jesus (NIV, Matthew 21:23). By priesthood authority, Mormonism answers, meaning an unmediated divine commission, direct authorization from God to preach and administer gospel ordinances like baptism, communion, confirmation, and, for Mormons, temple ordinances that represent the ultimate in our theology.[5] The Prophet Joseph Smith wrote, “We believe that no man can administer salvation through the gospel, to the souls of men, in the name of Jesus Christ, except he is authorized from God, by revelation, or [in other words] by being ordained by some one whom God hath sent by revelation.”[6] Mormonism’s modern Apostles call this “divine authority by direct revelation” the faith’s “most distinguishing feature.”[7]

The Apostles Peter, James, and John bestowed the higher priesthood authority on Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery. Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Apostles Peter, James, and John bestowed the higher priesthood authority on Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery. Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

“And who gave you this authority?” the elders asked Christ (NIV, Matthew 21:23). Joseph Smith answers frankly, baldly, thus: “The reception of the holy Priesthood [came] by the ministring of Aangels.”[8] In his now-canonized history, Joseph Smith remembered the events of May 1829 as he and scribe Oliver Cowdery were translating the Book of Mormon from ancient metal plates revealed by an angel. “We . . . went into the woods to pray and inquire of the Lord respecting baptism for the remission of sins, that we found mentioned in the translation of the plates. While we were thus employed, praying and calling upon the Lord, a messenger from heaven descended in a cloud of light, and having laid his hands upon us, he ordained us” (Joseph Smith—History 1:68). Joseph continued his matter-of-fact narrative, noting how the angel “said this Aaronic Priesthood had not the power of laying on hands for the gift of the Holy Ghost, but that this should be conferred on us hereafter; and he commanded us to go and be baptized, and gave us directions that I should baptize Oliver Cowdery, and that afterwards he should baptize me.” Only late in the account, almost as an afterthought, does Joseph reveal the identity of the ministering angel. He “said that his name was John, the same that is called John the Baptist in the New Testament, and that he acted under the direction of Peter, James and John, who held the keys of the Priesthood of Melchizedek, which Priesthood, he said, would in due time be conferred upon us, and that I should be the first Elder of the Church, and he (Oliver Cowdery) the second” (vv. 70, 72).

Joseph Smith combined nonchalance and historicity in his recounting of the event. He remembered that “it was on the fifteenth day of May, 1829, that we were ordained under the hand of this messenger, and baptized” (v. 72). Oliver Cowdery, by contrast, could hardly contain himself when he sat down to pen the good news:

The angel of God came down clothed with glory, and delivered the anxiously looked for message, and the keys of the gospel of repentance!—What joy! what wonder! what amazement! . . . our eyes beheld—our ears heard. As in the "blaze of day;” yes, more—above the glitter of the May Sun beam. . . . Then his voice, though mild, pierced to the center, and his words, “I am thy fellow servant,” dispelled every fear. We listened—we gazed—we admired! ’Twas the voice of the angel from glory— ’twas a message from the Most High! . . . But, dear brother think, further think for a moment, what joy filled our hearts and with what surprise we must have bowed . . . when we received under his hand the holy priesthood, as he said, “upon you my fellow servants, in the name of Messiah I confer this priesthood and this authority.”[9]

But Cowdery, too, in other statements, reported the events with striking straightforwardness. This example makes the point well: Joseph “was ordained by the angel John, unto the . . . Aaronic priesthood, in company with myself, in the town of Harmony, Susquehannah County, Pennsylvania, on Fryday, the 15th day of May, 1829. . . . After this we received the high and holy priesthood.”[10]

The understated nature of these claims to overtly historical ordinations by corporeal angels becomes more striking, for neither Joseph Smith nor Oliver Cowdery composed a narrative of their ordination to the high or Melchizedek priesthood by the Apostles Peter, James, and John. All we have are passing reminiscences: an 1834 revelation to Joseph in which the Lord describes “Peter, and James, and John, whom I have sent unto you, by whom I have ordained you and confirmed you to be apostles” (D&C 27:12); an 1842 musing about the time when Joseph Smith met “Peter, James, and John in the wilderness” near the Susquehannah River and they declared “themselves as possessing the keys of the kingdom.” They, along with a veritable who’s who of angels, transmitted to Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery “the power of their priesthood” (D&C 128:21). Smith and Cowdery in turn ordained new Apostles. Cowdery told them, “You have been ordained to the Holy Priesthood. You have received it from those who had their power and authority from an angel.”[11]

The climactic event in this history came as Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery prayed together in the temple at Kirtland, Ohio. No account of the event was published until 1852, but Joseph’s journal entry for April 3, 1836, says that they “saw the Lord standing upon the . . . pulpit before them.”[12] He was followed in succession by Moses, Elias, and Elijah, each authorizing some aspect of the gospel, the gathering of Israel, or the preparation of the world for the impending millennium. Feeling self-important, Oliver became disaffected from Joseph shortly thereafter. He confessed later to being hypersensitive but defended his character on the grounds that he had “stood in the presence of John . . . to receive the Lesser Priesthood—and in the presence of Peter, to receive the Greater, and look[ed] down through time, and witness[ed] the effects these two must produce.”[13]

“In the early Spring of 1844,” reported Wilford Woodruff, “Joseph Smith called the Twelve Apostles together, and he delivered unto them the ordinances of the Church and Kingdom of God; and all of the keys and powers that God had bestowed upon him.”[14] Joseph’s commission of the Apostles, Brigham Young chief among them, is crucial to Latter-day Saint claims to continuing priesthood authority. An early statement by the Apostles is therefore celebrated. It states that a quorum of Apostles were “confirmed by the holy anointing under the hands of Joseph,” after which he declared “that he had conferred upon the Twelve every key and every power that he ever held himself.”[15]

Many years later, Spencer W. Kimball stood with Elder Boyd K. Packer and others in the Church of Our Lady in Copenhagen, Denmark, admiring Thorvaldsen’s Christus and his sculptures of the Twelve Apostles. “I stood with President Kimball . . . before the statue of Peter,” Packer said. “In his hand, depicted in marble, is a set of heavy keys. President Kimball pointed to them and explained what they symbolized.”[16] Kimball then charged Copenhagen stake president Johan Bentine to “tell every prelate in Denmark that they do not hold the keys. I hold the keys!”[17] As the party left the church, President Kimball shook hands with the caretaker, “expressed his appreciation, and explained earnestly, ‘These statues are of dead apostles.’” Then, pointing to Apostles Tanner, Monson, and Packer, he added, “You are in the presence of living apostles.”[18] Terryl L. Givens wrote that “Mormonism’s radicalism can thus be seen as its refusal to endow its own origins with mythic transcendence, while endowing those origins with universal import since they represent the implementation of the fullest gospel dispensation ever. The effect of this unflinching primitivism, its resurrection of original structures and practices, is nothing short of the demystification of Christianity itself.”[19]

Such claims to authority have always been contested. But how does one contest the claims of two witnesses that they have been “ordained under the hands” of John, Christ’s baptizer?[20] How can one disprove Oliver Cowdery’s testimony that “upon this head has Peter James and John laid their hands and confered the Holy Melchizedek Priestood?’”[21] “Where was room for doubt?” Cowdery asked. But there was plenty of doubt, if not disproof. Joseph Smith was threatened with violence for claiming that “angels appear to men in this enlightened age.”[22] His history says that he and Oliver “were forced to keep secret the circumstances of our having . . . received this priesthood; owing to a spirit of persecution.”[23] But the secret was soon out. Oliver Cowdery “pretends to have seen Angels,” one editor wrote in 1830, and “holds forth that the ordinances of the gospel, have not been regularly administered since the days of the apostles, till the said Smith and himself commenced the work.”[24]

Alexander Campbell also contested Mormon claims to authority. Many of the first Mormons in Ohio came from his flock, including Sidney Rigdon, one of Campbell’s “leading preachers” until, Campbell said, he fell “into the snare of the Devil in joining the Mormonites” and “led away a number of disciples with him.”[25] At least two of those disciples were looking for God to “again reveal himself to man and confer authority upon some one, or more, before his church could be built up in the last days.”[26] Edward Partridge went to New York to be baptized by Joseph Smith and became Mormonism’s first bishop shortly thereafter. Parley P. Pratt liked Campbell’s doctrine very much, “but still one great link was wanting to complete the chain of the ancient order of things,” Pratt wrote (using one of Campbell’s favorite phrases), “and that was, the authority to minister in holy things—the apostleship, the power which should accompany the form.”[27] Pratt began looking for someone like Peter, who “proclaimed this gospel, and baptized for remission of sins, and promised the gift of the Holy Ghost, because he was commissioned so to do by a crucified and risen Saviour.”[28] He asked those of Campbell’s ministry, “Who ordained [you] to stand up as Peter?” Pratt subsequently set out in search of authority. He found it in Manchester, New York, at the home of Hyrum Smith. The two men talked through the night as Hyrum unfolded “the commission of his brother Joseph, and others, by revelation and the ministering of angels, by which the apostleship and authority had been again restored to the earth.” Pratt said he duly weighed “the whole matter in my mind” and concluded “that myself and the whole world were without baptism, and without the ministry and ordinances of God; and that the whole world had been in this condition since the days that inspiration and revelation had ceased.”[29] When Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery ordained twelve Apostles in 1835, Parley P. Pratt was one of them.

Campbell’s remaining followers criticized Mormons for “their pretensions to miraculous gifts” and apostolic authority and dismissed Mormonism as one more group of “superlative fanatics” claiming extrabiblical revelation.[30] A war of words ensued in which Campbell and Joseph Smith jabbed at each other by evoking passages from the Acts of the Apostles, each man casting himself implicitly as a modern Apostle. Alexander Campbell was like Paul condemning Elymas the sorcerer.[31] Joseph Smith was like Peter, calling on a modern son of Sceva to “repent, and be baptized . . . in the name of Jesus Christ . . . , and ye shall receive the gift of the Holy Ghost” (Acts 2:38).

A December 1830 revelation pressed this point. It called Rigdon to “a greater work” than assistant to Campbell and acknowledged that Rigdon had been baptizing “by water unto repentance, but they received not the Holy Ghost; but now I give unto thee a commandment, that thou shalt baptize by water, and they shall receive the Holy Ghost by the laying on of the hands, even as the apostles of old” (D&C 35:5–6). Joseph Smith emphasized the point in subsequent editorial answers to Campbell’s critiques, associating himself with Apostles while noting that whatever Campbell’s gifts, he neither had nor claimed apostolic authority to lay on hands: “With the best of feelings, we would say to him, in the language of Paul to those who said they were John’s disciples, but had not so much as heard there was a Holy Ghost, to repent and be baptised for the remission of sins by those who have legal authority, and under their hands you shall receive the Holy Ghost, according to the scriptures.”[32]

In 1832 Nancy Towle watched as Joseph Smith

turned to some women and children in the room; and lay his hands upon their heads; (that they might be baptized of the Holy Ghost;) when, Oh! cried one, to me, ‘What blessings, you do lose!—No sooner, his hands fell upon my head, than I felt the Holy Ghost, as warm water, to go over me!’

But I was not such a stranger, to the spirit of God, as she imagined; that I did not know its effects, from that of warm water! and I turned to Smith, and said ‘Are you not ashamed, of such pretensions? You, who are no more, than any ignorant, plough-boy of our land! Oh! blush, at such abominations! and let shame, cover your face!’

He only replied, by saying, ‘The gift, has returned back again, as in former times, to illiterate fishermen.’[33]

So it went, Joseph Smith claiming that “the Savior, Moses, & Elias—gave the Keys to Peter, James & John . . . and they gave it up” to him,[34] and critics like Charles Dickens citing Joseph’s ignorance, low-breeding, credulity, deception, and “pitiable superstitious delusion.” Said Dickens, “Joseph Smith, the ignorant rustic, sees visions, lays claim to inspiration, and pretends to communion with angels,” all “in the age of railways.”[35]

Competing but rarely expressed assumptions underlie these two positions. Mormons assume prima facie the possibility of Peter, James, and John ordaining Joseph Smith. Most people simply do not. Those among the majority who believe in angels at all are confident that they stopped appearing to rustics about the same time the last fisherman was ordained an Apostle, certainly before the Enlightenment or the age of railways. This certainty strikes Mormons as presumptuous, much as Mormon certainty of angels in the age of railways sounds presumptuous to others.

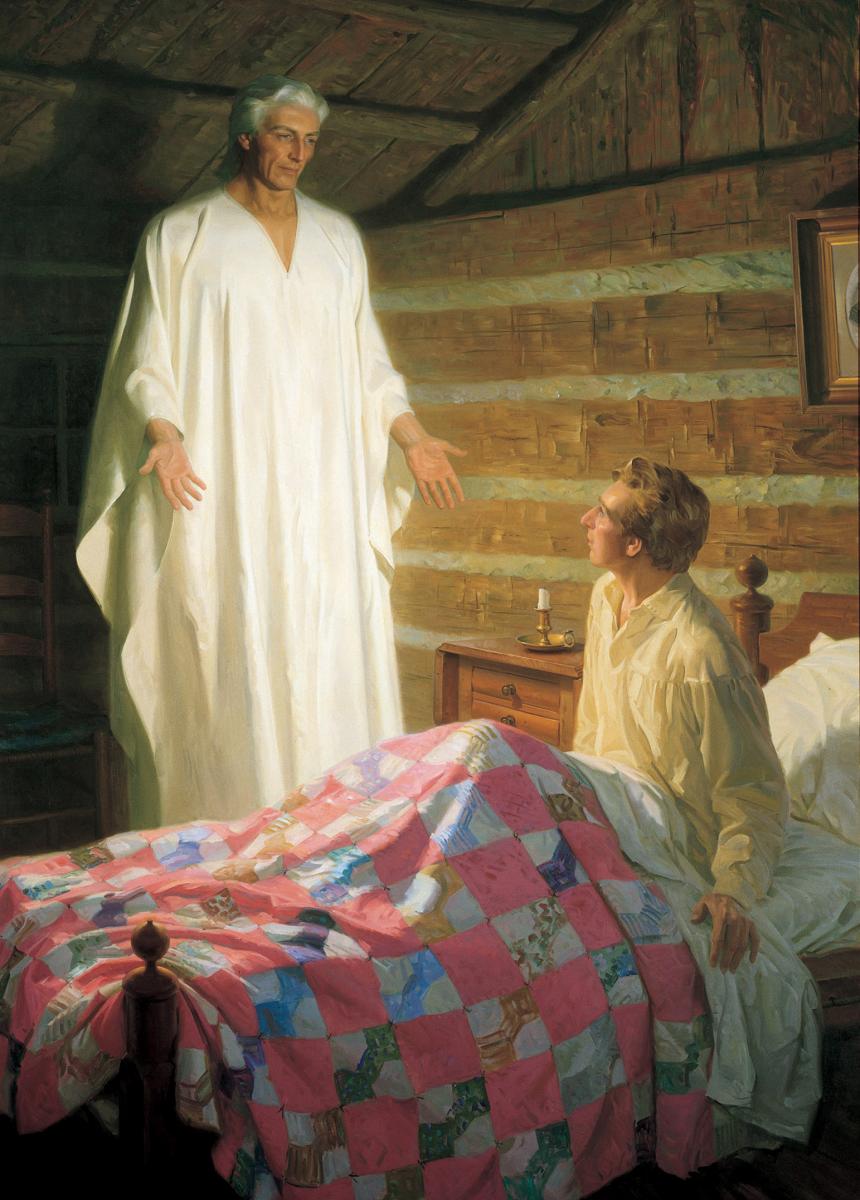

Moroni appeared at Joseph's bedside and told him about a book written on gold plates.Tom Lovell, The Angel Moroni Appears to Joseph Smith, Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Moroni appeared at Joseph's bedside and told him about a book written on gold plates.Tom Lovell, The Angel Moroni Appears to Joseph Smith, Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

In May 2005, various holders of these two assumptions took the stage at the Library of Congress in a conference on the worlds of Joseph Smith. His assertion of apostolic authority by direct revelation was a pervasive theme in their presentations. It was another installment in the long history of discussions about authority in Christian traditions, more polite but otherwise not far removed from the nineteenth-century contests over Joseph Smith’s testimony. Elder Dallin H. Oaks, former law professor, university president, and state supreme court justice, was the featured speaker, but not primarily on those credentials. He is an Apostle, and alongside references to his own research and scholarship, he spoke like one.

Mormon philosopher David L. Paulsen spoke on the ways Joseph Smith challenges Christian theology, beginning with the premise that theology itself is necessary only in the absence of Apostles who are chosen and ordained as the New Testament indicates. “Apostolic authority is not something that can be chosen,” Paulsen argued. “It was a divine calling issued by the Lord himself, the fruits of which are evidence of the call’s divine origin.” Chief among such fruits, said Paulsen, are revelations that “enabled the apostles to direct the church’s affairs under God’s direction.” The rise of theology is evidence of the end of apostolic authority, Paulsen contends, and his is no voice in the wilderness. Thus Joseph Smith’s claim to direct revelation from God is his ultimate challenge to theology, “a challenge based on the Bible itself.”[36]

Randall H. Balmer, professor of religion at Barnard College of Columbia, addressed Paulsen’s key points, agreeing that “the issue of authority has been vexing throughout Christian history”[37] but rejecting Paulsen’s premise that a loss of apostolic authority necessitated a divine restoration. Instead, Balmer argued, Jesus put authority in Peter in a very Protestant way, so as to “vitiate some of the authoritarianism of the episcopal polity in the Roman Catholic Church.” Balmer calls Peter “the apotheosis of fallibility,” arguing that Christian authority, God’s special revelation, is Jesus, and following him, “of course, is the scriptures.” Knowing our next question, Balmer asks it himself. “What counts as scripture?”[38] “How does one know what is and is not scripture?” The questions unfold. “How do we know anything? What is the basis for our epistemology?”[39] Elder Oaks had the previous evening set forth a distinctive Mormon epistemology, “the principle of independent verification by revelation.”[40] Paulsen asserted it again by quoting an early LDS newspaper article: “Search the revelations which we publish, and ask your Heavenly Father, in the name of His Son Jesus Christ, to manifest truth unto you, and if you do it with an eye single to His glory nothing doubting, He will answer you by the power of His Holy Spirit. You will then know for yourselves.”[41]

I longed to hear Balmer’s analysis of this epistemology, which I find compelling, but instead he dismissed it as quickly as Alexander Campbell had done, though on different grounds.[42] “Circularity,” Balmer called it, caricaturing Paulsen as saying that we know the Book of Mormon is true because it says so, or that Joseph Smith received revelations because he said he did. Balmer did not engage the epistemology of independent verification by personal revelation, and he offered little instead. “The early church settled the issue of canonicity,” he says, “through a kind of emerging consensus, codified finally in various church councils.”[43] The kind of consensus to which Balmer refers is a highly qualified kind, as Arians and Donatists would testify. When has there been any other kind of consensus among Christians about the canon? Balmer concluded with what must have been self-conscious irony. He quoted Karl Barth’s “simple Sunday-school ditty: ‘Jesus loves me, this I know; for the Bible tells me so.’”[44] The questions he raised went unanswered.

Thus the Library of Congress conference did not resolve Christianity’s contested claims to authority. But it was an impressive stage for the ongoing debate. Durham University professor of religion Douglas J. Davies led off the concluding session with a learned analysis of Mormonism’s potential to become recognized as a world religion. He predicted the possibility that Mormonism would grow globally by decentralizing and taking on regional identities.[45] “Not and continue to be Mormonism,” I thought to myself. Roger R. Keller, professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University and a former Presbyterian minister, offered a penetrating response based on his own learning and experience. “Latter-day Saints have often said to me,” Keller stated, “We are so glad that you found the gospel.” My response has always been, ‘I knew the gospel long before I was a Latter-day Saint. What I have found is the fullness of the gospel.’ The essence of that fullness is that the authority of the priesthood is found only within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. . . . This understanding of authority is absent from Davies’s paper,” Keller said, “and this absence colors what he has said about the dynamics and constraints of Latter-day Saint church growth.”[46]

Keller concluded with his own prediction that Mormonism will never take on the decentralized and diverse characteristics Davies prescribed for global religions, precisely “because . . . restored authority to administer the saving ordinances of the gospel through a divinely revealed structure . . . will not permit us to do so.”[47] Davies rose when it was time to respond and said with obvious frustration, “What are we doing here?” venting some of the tension that always accompanies Mormon claims. Brabazon Ellis vented it by asking Alfred Cordon to work him a miracle. There was none of that at the Library of Congress, but Davies wondered aloud whether we were having an academic conference or proselyting. It is hard and somewhat purposeless for Mormons to separate the two. Because Mormon claims to authority are historical and because they demystify Christianity, merely asserting them—as I have done—sounds like preaching. They have a kind of challenging aspect.

This is simply so, and it makes me feel like taking another crack at explaining the epistemology of independent verification by personal revelation. It is, first of all, irreducibly historical. As Paulsen put it, “Joseph claimed that God restored divine authority by literal hand-to-head transfer by the very prophets and apostles whose lives and words are recounted in the Bible.”[48] But we misunderstand if we think Mormonism claims to be scientifically provable based on historical documentation or Enlightenment propositions. Rather, the historical record provides Latter-day Saints with something to verify independently by direct revelation. And, to quote Joseph Smith, “Whatever we may think of revelation . . . without it we can neither know nor understand anything of God.”[49] A person does not know that John the Baptist ordained Joseph Smith because Joseph said so, but because God has revealed to that individual that Joseph told the truth when he said so. The first and perhaps finest example of this is Samuel Smith, Joseph’s younger brother. Joseph’s history says that a few days after John the Baptist ordained him and Cowdery, Samuel came to visit. Zealous teaching by the newly ordained missionaries notwithstanding, Samuel “was not very easily persuaded . . . but after much enquiry and explanation he retired to the woods, in order that by secret and fervent prayer he might obtain of a merciful God, wisdom to enable him to judge for himself: The result was that he obtained revelation for himself sufficient to convince him of the truth of our assertions to him, and . . . Oliver Cowdery baptized him, and he returned to his father’s house greatly glorifying and praising God, being filled with the Holy Spirit.”[50]

Elijah appeared to Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery in the Kirtland Temple. Dan Lewis, Elijah Appearing in the Kirtland Temple, 2007 Dan Lewis.

Elijah appeared to Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery in the Kirtland Temple. Dan Lewis, Elijah Appearing in the Kirtland Temple, 2007 Dan Lewis.

Joseph Smith was conscious, as I am, of the perils of self-deception and all manner of pseudorevelation. Mormonism certainly runs that risk. But considering the alternatives of agnosticism, or even of strict historicism, or of an epistemology dependent on so-called philosophical consensus, I have chosen to put my faith in independent verification by personal revelation and have not been disappointed. An inerrant Bible would not even suffice unless we had inerrant interpreters, or, as Mormons assert, an inerrant Christ to guide otherwise fallible interpreters by revelation.[51] Still, without revelation, we cannot know anything of God. “God has revealed it to us by his Spirit,” Paul taught the Corinthians, based on the premise that “no one knows the thoughts of God except the Spirit of God” (NIV, 1 Corinthians 2:10–11).

I find this principle of independent verification by revelation to be liberated from the limitations of Enlightenment or postmodern epistemologies, and unconstrained by what Joseph Smith regarded as the God-muzzling composition of creeds and closure of the canon.[52] Often Joseph turned the Bible on those who regarded themselves as its biggest defenders. To the question, “Is there any thing in the Bible which lisenses you to believe in revelation now a days?” He answered, “Is there any thing that does not authorise us to believe so; if there is, we have, as yet, not been able to find it.” But “is not the cannon of the Scriptures full?” “If it is,” he replied, “there is a great defect in the book, or else it would have said so.”[53] Holding open the possibilities that angels could restore priesthood, and that anyone can verify whether they have by direct revelation, is liberating and empowering epistemology. It frees the mind to believe that some things can indeed be certainly known, though not by history itself. Rather, this knowledge is gained at the intersection of historically attested events and a kind of pragmatism of personal experience.

My life is organized by this priesthood authority. I was baptized by my father, who afterward laid his hands on my head and invited me to receive the Holy Ghost. I share the tangible if incommunicable experience of Samuel Smith and of the woman Joseph Smith confirmed in 1832, whose witness Nancy Towle dismissed as the effects of warm water. My father later ordained me to the Aaronic and the Melchizedek priesthoods, giving me a line of authority that traces my ordination through him back to Peter, James, and John. He again laid hands on me when I was critically ill with encephalitis, and I was healed. My grandfather laid his hands on my head for a patriarchal blessing when I was fourteen and was fixated on things other than an academic life. He talked much of school and foretold several of my most formative experiences, including my endless pursuit of education. Most personally, my wife and I were sealed in the temple by this priesthood, which transcends death. For us that means our children are bound eternally to us and us to each other. I now bless and baptize and confirm those children in turn by virtue of the holy priesthood Joseph Smith received from ministering angels. It is the single greatest determinant of my life.

Some will surely say, then, that Mormon priesthood is just so much sentimentality. But for me its power is undeniable. And not primarily because it heals bodies or validates binding ordinances. Rather, the power of the priesthood holds the key to knowing God, the key to transcendence and godliness (see D&C 84:19–23). One of Joseph Smith’s most sublime revelations declared that “the rights of the priesthood are inseparably connected with the powers of heaven,” which cannot be controlled or handled illicitly. Priesthood may be conferred, the revelation says, but “amen to the priesthood or the authority of that man” who exercises control, or dominion, or compulsion on anyone in any degree of unrighteousness. Authoritarianism is not authority. Priesthood is not license. Men exercise authority tyrannically by nature and disposition, the revelation says, but this is apostate priesthood. Priesthood power is as dew that distills upon the soul who self-consciously rejects authoritarianism in favor of persuasion, long-suffering, gentleness and meekness, kindness, and unfeigned love without hypocrisy or guile. Otherwise, “no power or authority can or ought to be maintained.” Anyone who exercises what the revelation calls “unrighteous dominion” forfeits priesthood and “is left unto himself . . . to fight against God” (see D&C 121). God, though sovereign, compels no one. He makes plans and provisions for the salvation of his children but neither elects them to grace unconditionally nor saves them contrary to their will. He love, sacrifices, and ministers. We may be confident in his presence only if we willingly act in the same selfless ways.

Nineteenth-century Protestants made no pretensions to “confer any new powers by the acts of ordination,”[54] but increasingly democratized authority by locating priesthood in believers generally. Catholic and Mormon priesthood seemed the opposite of this and akin to each other. Ordination in both traditions elevated one nearer to Christ.[55] But the priesthood Joseph Smith conferred actually elevated the ordained even as it maximized their number. His radical priesthood of believers did not mitigate authority by democratizing it, but universally endowed ordained men with “transcendent power which cut against every grain of American, republican culture.”[56] Joseph Smith read Hebrews 7 literally. Melchizedek was ordained a priest of the Most High God, and made like the Son of God, and abideth a priest continually. But Joseph Smith added a potent gloss, declaring that “all those who are ordained unto this priesthood are made like unto the Son of God, abiding a priest continually” (JST, Hebrews 7:3, LDS Bible appendix; emphasis added). Joseph “wanted to invest all the men among his followers with the powers of heaven descending through the priesthood.”[57] Such power renders God knowable and every man and woman capable of exaltation in the image of God (see D&C 84, 132). A kitschy plaque I received before my ordination summed all this up. “Priesthood,” it said, “is not only the power to act in the name of God. It is the power to become like Him.” That possibility is blasphemous to most Protestants and Catholics, though not, unless I am mistaken, to Orthodox Christians. It seems therefore safe to say that Joseph Smith’s testimony of angels ordaining him to priesthood for the express purpose of exalting men and women as priests and priestesses, kings and queens, will continue to be contested for a long time.[58]

I cannot solve the problem; perhaps I can only exacerbate it. Randall Balmer asked, “Why Smith?”[59] I ask, Why not? The documentation evidencing John the Baptist’s ordination of Joseph Smith is at least as good as the documentation evidencing his baptism of Christ. If one can independently verify both claims by direct revelation through the Holy Spirit, why not believe? And if one cannot independently verify the truthfulness of a claim by revelation, why believe? I wonder whether such an epistemology will appeal to anyone unwilling to grant the premise that angels could have ordained Joseph Smith or that he might have received extrabiblical revelations or that anyone can verify these by an unmediated experience with God. But for me to be convinced otherwise would require potent refutation—not merely rejection—of those same premises. The argument would have to explain why God no longer gives special revelation to prophets and apostles, and it seems unlikely that anything short of a special revelation could do that. The Westminster Confession’s certainty about the sufficiency of the Bible, “unto which nothing at any time is to be added,” not even by “new revelations of the Spirit,”[60] sounds presumptuous in Mormon ears—perhaps as presumptuous as St. Peter ordaining a New York farmer must sound to many Christians. Divine authority by direct revelation is the reason for Mormonism’s existence.[61] Moreover, the power to know for oneself that divine authority is vested in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is that without which Mormonism would cease to be, or at least cease to be compelling to me.[62] This pair of doctrines is simultaneously authoritative and empowering to the individual—truth that makes one free.

Is it possible that angels could appear in this enlightened age, bringing authority to unsophisticated mortals to act for Christ again, as in former times? As the epigraph for his influential Millennial Harbinger, Alexander Campbell chose Revelation 14:6: “I saw another angel flying in midair, and he had the eternal gospel to proclaim to those who live on the earth” (NIV, Revelation 14:6), though Campbell rendered it as “I saw another messenger flying through the midst of heaven, having everlasting good news to proclaim to the inhabitants of the earth.” What Campbell intended by replacing the biblical word angel with the less-defined messenger, I do not know. But Joseph Smith’s literal reading of the same passage is a revealing contrast. He thought John’s revelation foresaw actual angelic ministers, one of whom appeared in Joseph’s New York bedroom as he prayed on September 21, 1823. Joseph said, “He called me by name, and said unto me that he was a messenger sent from the presence of God to me, and that his name was Moroni; that God had a work for me to do; and that my name should be had for good and evil among all nations” (Joseph Smith—History 1:33). Such a claim was foolishness to Alexander Campbell, Nancy Tracy, Charles Dickens, and countless others. It was biblical and thoroughly believable, however, to those who knew Joseph best. And it sounded so to Alfred Cordon on the other side of the Atlantic. But how could he know? He sought independent verification by direct revelation. “Away I went to my Bible and to prayer,” he wrote, and “the Spirit of God bore testimony to the truth” of the assertion that the angel of Revelation 14 had indeed proclaimed the eternal gospel in the age of railways.[63]

Notes

[1] Alfred Cordon Journal, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City; hereafter cited as Cordon, Journal. For a discussion of the Episcopal views on authority that informed Brabazon Ellis, see E. Brooks Hollifield, Theology in America: Christian Thought from the Age of the Puritans to the Civil War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 245–47.

[2] Cordon, Journal.

[3] Cordon, Journal.

[4] Cordon, Journal.

[5] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Of Missions, Temples, and Stewardship,” Ensign, November 1995, 53.

[6] Joseph Smith to Isaac Galland, March 22, 1839, in Dean C. Jessee, ed., Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, rev. ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret, 2002), 459.

[7] Jeffrey R. Holland, “Our Most Distinguishing Feature,” Ensign, May 2005, 43. Also Dallin H. Oaks, “Joseph Smith in a Personal World,” BYU Studies 44, no. 4 (2005): 154.

[8] “A History of the Life of Joseph Smith Jr.,” Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah, quoted in Opening the Heavens, ed. John W. Welch (Provo, UT: Salt Lake City: Brigham Young University Press; Deseret Book, 2005), 4.

[9] Messenger and Advocate, October 1834, 14–16.

[10] Patriarchal Blessings, Book 1 (1835), 8–9, “Oliver Cowdery, Clerk and Recorder. Given in Kirtland, December 18, 1833, and recorded September 1835.”

[11] Kirtland High Council Minutes, February 21, 1835, 159.

[12] Dean C. Jessee, ed., The Papers of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989–92), 2:209; D&C 110.

[13] Oliver Cowdery to Phineas Young, March 23, 1846, Church History Library.

[14] Wilford Woodruff statement, March 19, 1897, Church History Library.

[15] Declaration of the Twelve Apostles, Brigham Young Papers, Church History Library.

[16] Boyd K. Packer, The Holy Temple (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1980), 83.

[17] Edward L. Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride: The Presidency of Spencer W. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005), 327.

[18] Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride, 108.

[19] Terryl L. Givens, Viper on the Hearth: Mormons, Myth, and the Construction of Heresy (Provo UT: Maxwell Institute, 1997), 8.

[20] Stephen Post, Journal, Stephen Post Papers, March 27, 1836, Church History Library.

[21] David H. Cannon, Autobiography, quoted in Brian Q. Cannon, “Priesthood Restoration Documents,” BYU Studies 35, no. 4 (1995–96), 198 n. 10.

[22] “Mormonism—No. II,” Tiffany’s Monthly, June 1959, 168.

[23] Joseph Smith, “History, 1839,” Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library, 18; compare Joseph Smith—History 1:74–75.

[24] “The Golden Bible,” Painesville Telegraph, November 16, 1830, 3.

[25] Millennial Harbinger 2 (1831): 100–101. In June 1828 Campbell noted how effective Rigdon had lately been: “Bishop’s Scott, Rigdon, and Bentley, in Ohio, within the last six months have immersed about eight hundred persons.” “Extracts of Letters,” Christian Baptist (June 2, 1828), 263.

[26] Edward Partridge Papers, May 26, 1839, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[27] Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt, ed. Scot Facer Proctor and Maurine Jensen Proctor (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 13.

[28] Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt, 14.

[29] Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt, 22.

[30] Alexander Campbell, “Mormonism Unveiled,” Millennial Harbinger, January 1835.

[31] In the January 1831 issue of the Millennial Harbinger, Campbell’s influential article, “Delusions,” includes this line: “I have never felt myself so fully authorized to address mortal man in the style in which Paul addressed Elymas the sorcerer as I feel towards this Atheist [Joseph] Smith” (96). Campbell refers to Acts 13:6–12.

[32] Joseph Smith, “To the Elders of the Church of the Latter Day Saints,” Messenger and Advocate, December 1835, 225–230. The article continues: “Then laid they their hands on them, and they received the Holy Ghost.—Acts: ch. 8, v. 17. And, when Paul had laid his hands upon them, the Holy Ghost came on them: and they spake with tongues, and prophesied.—Acts : ch. 19, v. 6. Of the doctrine of baptisms, and of laying on of hands, and of resurrection of the dead, and of eternal judgment.—Heb. ch. 6, v.2. How then shall they call on him in whom they have not believed? and how shall they believe in him of whom they have not heard? and how shall they hear without a preacher? And how shall they preach except they be sent? as it is written, How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the gospel of peace, and bring glad tidings of good things!—Rom. ch. 10, v. 14–15.”

[33] Nancy Towle, Vicissitudes Illustrated, in the Experience of Nancy Towle, in Europe and America (Charleston, SC: James L. Burges, 1832), 144–45.

[34] The Words of Joseph Smith, ed. Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1980), 9.

[35] Charles Dickens, “In the Name of the Prophet—Smith!” Household Words 69, no. 3 (July 1851), 69.

[36] David Paulsen, “Joseph Smith Challenges the Theological World,” BYU Studies 44, no. 4 (2005): 178.

[37] Randall H. Balmer, “Speaking of Faith: The Centrality of Epistemology and the Perils of Circularity,” BYU Studies 44, no. 4 (2005): 23.

[38] Balmer, “Speaking of Faith,” 225.

[39] Balmer, “Speaking of Faith,” 226. See also Robert Clyde Johnson, Authority in Protestant Theology (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1959).

[40] Oaks, “Joseph Smith in a Personal World,” 167.

[41] David Paulsen, “Joseph Smith Challenges the Theological World,” 202.

[42] Alexander Campbell, “Delusions,” Millennial Harbinger, February 10, 1831, 96.

[43] Balmer, “Speaking of Faith,” 226.

[44] Balmer, “Speaking of Faith,” 230. On this point also see Kathleen C. Boone’s penetrating study The Bible Tells Them So: The Discourse of Protestant Fundamentalism (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989). See also Randall Balmer, Growing Pains (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos, 2001), 61–62, and Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory: A Journey into the Evangelical Subculture in America, 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), especially 40–45.

[45] Douglas J. Davies, “World Religion: Dynamics and Constraints,” BYU Studies 44, no. 4 (2005): 253–70.

[46] Roger R. Keller, “Authority and Worldwide Growth,” BYU Studies 44, no. 4 (2005): 308–9.

[47] Keller, “Authority and Worldwide Growth,” 315.

[48] Paulsen, “Joseph Smith Challenges the Theological World,” 184.

[49] Editorial, 1 April 1842, Nauvoo, Illinois, “Try the Spirits” Times and Seasons, April 1, 1842, 743–48.

[50] Papers of Joseph Smith, 1:232.

[51] Boone, The Bible Tells Them So, 77.

[52] An admirable work limited by Enlightenment rationalism is Hans Von Campenhausen, Ecclesiastical Authority and Spiritual Power in the Church of the First Three Centuries (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1969). A postmodern approach is Laura Salah Nasrallah, An Ecstasy of Folly: Prophecy and Authority in Early Christianity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003). For a Catholic approach shaped by both Enlightenment and postmodern modes, see David J. Stagman, Authority in the Church (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1999).

[53] Editorial, Elders’ Journal, July 1838, 42–44.

[54] Joseph Tuckerman, A Memorial of Rev. Joseph Tuckerman (Worcester, MA: Private press of Franklin P. Rice, 1888), 264.

[55] David Holland, “Priest, Pastor, and Power: Joseph Smith and the Question of Priesthood,” Archive of Restoration Culture (Provo, UT: Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Latter-day Saint History, 2000): 11–12.

[56] Holland, “Priest, Pastor, and Power,” 14.

[57] Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 160.

[58] Richard J. Mouw, “Joseph Smith’s Theological Challenges: From Revelation and Authority to Metaphysics,” BYU Studies 44, no. 4 (2005); D&C 2, 84, 107, 132.

[59] Balmer, “Speaking of Faith,” 225.

[60] Westminster Confession of Faith, 1:6.

[61] Joseph Smith taught that “the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was founded upon direct revelation, as the true church of God has ever been, according to the scriptures.” “Latter Day Saints,” in I. Daniel Rupp, He Pasa Ekklesia: An Original History of the Religious Denominations at Present Existing in the United States (Philadelphia: J. Y. Humphreys, 1844), 404.

[62] James E. Faust, “Where Is the Church?” devotional address delivered at Brigham Young University, March 1, 2005.

[63] Cordon, Journal.