On Agency

D. Morgan Davis

D. Morgan Davis, "On Agency," Religious Educator 11, no. 3 (2010): 59–77.

D. Morgan Davis (morgan_davis@byu.edu) was an assistant research fellow at BYU’s Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship when this written.

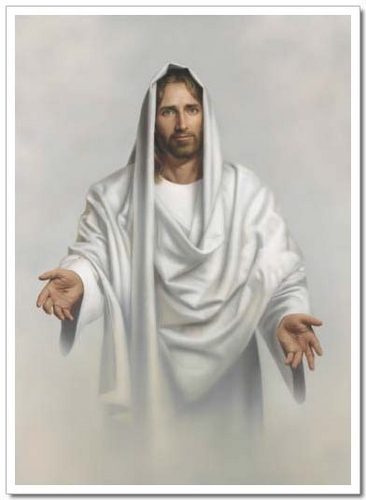

The Atonement itself is a fruit of Christ's own agency: he freely suffered and gave his life for mankind, freely submitting his own will to the will of the Father. Copyright Simon Dewey. Courtesy Atlus Fine Art/

The Atonement itself is a fruit of Christ's own agency: he freely suffered and gave his life for mankind, freely submitting his own will to the will of the Father. Copyright Simon Dewey. Courtesy Atlus Fine Art/

The Articles of Faith reflect the importance of moral agency in God’s plan for his children. They begin with a statement of belief “in God, the Eternal Father, and in His Son, Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Ghost” (Articles of Faith 1:1). A belief in God is surely the foundational doctrine of the gospel. But what article of faith comes very next? It is this: “We believe that men will be punished for their own sins, and not for Adam’s transgression” (Articles of Faith 1:2). Within the Church, this declaration is most often (and not incorrectly) seen as a rejection of the traditional Christian notion of original sin—the teaching that everyone born into this world is guilty of the transgression committed by Eve and then Adam in the Garden of Eden. But it is more than that. In rejecting original sin, the second article of faith nevertheless affirms the reality of the Fall and establishes the immovable doctrine of each person’s individual liability for the wrong choices he or she makes—we will be punished for our own sins. It is a statement, in other words, that recognizes the operation of individual moral agency. Only after this profoundly basic statement do we have, in the third article of faith, the hope-filled declaration, “We believe that through the Atonement of Christ, all mankind may be saved, by obedience to the laws and ordinances of the gospel” (Articles of Faith 1:3). In the priority of the Articles of Faith, then, agency precedes even the Atonement and is second only to the reality of the Godhead as a most basic teaching of the gospel; the second article of faith constitutes the basis for the third. If it were not for agency, by which came sin and death, there would be no need for an Atonement, by which comes redemption and life.[1] Indeed, there could be no Atonement, since the Atonement itself is a fruit of Christ’s own agency: he freely suffered and gave his life for mankind, freely submitting his own will to the will of the Father (see Luke 22:42; Mosiah 15:7).

For many years it was common within the Church to speak of the power to choose as “free agency.” This term was used in the sermons and writings of Presidents of the Church and other General Authorities, in the videos and printed materials produced officially by the Church, and in the common parlance of the general membership.[2] Presumably the term “free agency” was initially intended and properly understood to convey a positive appreciation for the fruits of Christ’s redemptive work, such as when Lehi prophetically testified:

The Messiah cometh in the fulness of time, that he may redeem the children of men from the fall. And because that they are redeemed from the fall they have become free forever, knowing good from evil; to act for themselves and not to be acted upon, save it be by the punishment of the law at the great and last day, according to the commandments which God hath given.

Wherefore, men are free according to the flesh; and all things are given them which are expedient unto man. And they are free to choose liberty and eternal life, through the great Mediator of all men, or to choose captivity and death, according to the captivity and power of the devil; for he seeketh that all men might be miserable like unto himself. (2 Nephi 2:26–27; emphasis added)

And we have this lyric by Eliza R. Snow, one of the Restoration’s great poets:

His precious blood he freely spilt;

His life he freely gave,

A sinless sacrifice for guilt,

A dying world to save.[3]

According to these and other witnesses, Christ’s atoning sacrifice, freely given, makes men and women free—free from Adam’s transgression, free to choose and walk the path that will lead them to eternal life, or free to take the path that will lead them to spiritual death. But there are also at least two important ways that men and women are not free.

First, we are not free to remain neutral. We must and do choose; to be indecisive or vacillating is itself a choice. The Encyclopedia of Mormonism states: “Agency is such that . . . individuals capable of acting for themselves cannot remain on neutral ground, abstaining from both receiving and rejecting light from God. To be an agent means both being able to choose and having to choose.”[4]

Second, we are bound by the consequences of our choices. In For the Strength of Youth, the First Presidency has forthrightly declared: “While you are free to choose for yourself, you are not free to choose the consequences of your actions. When you make a choice, you will receive the consequences of that choice. The consequences may not be immediate, but they will always follow, for good or bad.”[5]

We are no more free to choose the spiritual consequences of our moral choices than we are to choose the physical consequences of driving—intentionally or otherwise—over a cliff, or of swallowing poison. And yet all around us we see pervasive evidence of a society deluded into supposing that unethical or sinful behavior does not matter as long as one is not caught, and that one can in fact get away with murder, fraud, or infidelity. Too many believe as Cain, who, with the innocent blood of his brother staining his hands, “gloried in that which he had done, saying: I am free” (Moses 5:33). Perhaps it is this Cain-like confusion or self-deception that has prompted a shift in diction regarding agency within the Church. The change was first signaled publicly by President Boyd K. Packer of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in 1992. In his April address at general conference that year, an address pointedly entitled “Our Moral Environment,” President Packer noted that “the phrase ‘free agency’ does not appear in scripture. The only agency spoken of there,” he stated, “is moral agency.”[6] More recently, the curriculum for the Primary sharing time and the Primary sacrament meeting program contained the following clarification as part of a glossary of terms:

As you teach . . . this year, please use and help the children understand correct terms and doctrine. Pay particular attention to the following: . . .

Agency: The ability to choose and act for oneself. Use the term agency rather than free agency to describe our freedom to choose. Agency is the term used in the scriptures (see D&C 29:36; Moses 7:32).[7]

Likewise, we find this note in the lesson on agency in Preparing for Exaltation: Teacher’s Manual: “Although the term ‘free agency’ is often used, the correct, scriptural term is simply ‘agency.’”[8]

Elder D. Todd Christofferson has summarized the Church’s deemphasis of the term free agency thus:

In years past, we generally used the term free agency. That is not incorrect, but more recently we have taken note that free agency does not appear as an expression in the scriptures. They talk of our being “free to choose” and “free to act” for ourselves and of our obligation to do many things of our own “free will.” But the word agency appears either by itself or, in Doctrine and Covenants, section 101, verse 78, with the modifier moral: “That every man may act in doctrine and principle . . . according to the moral agency which I have given unto him, that every man may be accountable for his own sins in the day of judgment” (emphasis added). When we use the term moral agency, then, we are appropriately emphasizing the accountability that is an essential part of the divine gift of agency. We are moral beings and agents unto ourselves, free to choose but also responsible for our choices.[9]

These clarifications seem intended to underscore the point that freedom of choice is itself not free; it has multiple costs. First, it comes with irrevocable and unavoidable consequences for each agent. Second, the guarantor of human agency is Christ, who paid its price with his own blood. Third is another price that is sometimes overlooked; it is the price the Father himself paid when he allowed the third part of the hosts of heaven—his children—to use their agency to follow Lucifer in open rebellion against him and the plan he had established to make them free. As a consequence of the Father’s own commitment to uphold the principle of moral agency, a significant portion of his family were lost to him and cast down, put forever beyond the reach of Christ’s liberating and exalting Atonement (D&C 29:36–37; see also v. 29). The events of the premortal Council in Heaven are still reverberating today and still have much to teach about the nature of agency.

What Happened in Heaven

Many members of the Church are unaware that there is an area of interpretive ambivalence regarding the account of Lucifer’s rebellion against the Father’s plan to send Christ to be the Savior of the world. There are at least two mutually incompatible interpretations of how Lucifer intended to destroy the agency of man. As will be seen, this is not merely a matter of academic trivia. How we read Lucifer’s premortal gambit for power has implications for our understanding of the nature of agency itself. The ambivalence was stated succinctly by President J. Reuben Clark Jr. of the First Presidency: “As I read the scriptures, Satan’s plan required one of two things: Either the compulsion of the mind, the spirit, the intelligence of man, or else saving men in sin. I question whether the intelligence of man can be compelled. Certainly men cannot be saved in sin, because the laws of salvation and exaltation are founded in righteousness, not sin.”[10]

The most detailed account of what was said and done in that premortal council is found in Moses 4. The wording is important. There, the Lord teaches Moses:

That Satan, whom thou hast commanded in the name of mine Only Begotten, is the same which was from the beginning, and he came before me, saying—Behold, here am I, send me, I will be thy son, and I will redeem all mankind, that one soul shall not be lost, and surely I will do it; wherefore give me thine honor.

But, behold, my Beloved Son, which was my Beloved and Chosen from the beginning, said unto me—Father, thy will be done, and the glory be thine forever.

Wherefore, because that Satan rebelled against me, and sought to destroy the agency of man, which I, the Lord God, had given him, and also, that I should give unto him mine own power; by the power of mine Only Begotten, I caused that he should be cast down;

And he became Satan, yea, even the devil, the father of all lies, to deceive and to blind men, and to lead them captive at his will, even as many as would not hearken unto my voice. (Moses 4:1–4)

The third sentence above crucially says that Satan “sought to destroy the agency of man.” Note that the word is not abridge or curtail or limit, but destroy. Lucifer was plotting a total coup, not just of God’s power, but of everyone’s agency. But what specifically was he proposing to do, and how would it have destroyed agency?

The “Forced Obedience” Reading

What seems currently to be the most widespread interpretation of Lucifer’s counterproposal to the Father’s plan is expressed in the lyrics of a popular LDS musical, My Turn on Earth, where a character representing Lucifer sings, “I have a plan / It will save every man / I will force them to live righteously.”[11] This is not merely a folk interpretation of the account, however. Perhaps the earliest and still one of the most influential statements of it is found in James E. Talmage’s Jesus the Christ, a monumental work first published in 1915. It is still widely read and consulted today, and it is part of the approved library for all missionaries of the Church. Early in the volume, Elder Talmage discusses the premortal council and characterizes Lucifer’s plan as one of “compulsion, whereby all would be safely conducted through the career of mortality, bereft of freedom to act and agency to choose, so circumscribed that they would be compelled to do right—that one soul would not be lost.”[12]

The logic behind the “forced obedience” interpretation of Lucifer’s proposal might be summed up as follows: If agency is the ability to act for oneself, then the statement that Lucifer sought to destroy agency means that he intended to destroy man’s freedom of action. Man would be compelled in his actions because perfect compliance with an immutable standard of righteousness—without the benefit of any Atonement or grace to make repentance for transgressions possible—would be required for salvation. All souls would be compelled to righteous action at every juncture in order that all might be saved.[13]

This, as has been said, is a very prevalent interpretation. It has been articulated by various leaders of the Church since Elder Talmage and can be found in various places throughout the current official Church curriculum.[14]

In 1950, President David O. McKay taught:

Freedom of the will and the responsibility associated with it are fundamental aspects of Jesus’ teachings. . . .

Force, on the other hand, emanates from Lucifer himself. Even in man’s [premortal] state, Satan sought power to compel the human family to do his will by suggesting that the free agency of man be inoperative. If his plan had been accepted, human beings would have become mere puppets in the hands of a dictator, and the purpose of man’s coming to earth would have been frustrated. Satan’s proposed system of government, therefore, was rejected, and the principle of free agency established.[15]

President McKay uses the imagery of puppets to suggest the outcome of the destruction of agency. Persons would be moved in all ways and in all things by an all-powerful dictator who had total physical and mental control of them. President Joseph Fielding Smith held a similar view:

If there had been no free agency, there could have been no rebellion in heaven; but what would man amount to without this free agency? He would be no better than a mechanical contrivance. He could not have acted for himself, but in all things would have been acted upon, and hence unable to have received a reward for meritorious conduct. He would have been an automaton; could have had no happiness nor misery, “neither sense nor insensibility,” and such could hardly be called existence. Under such conditions there could have been no purpose in our creation.[16]

Note here President Smith’s emphasis on freedom to act as the essential trait of agency. He continues in this vein when he writes that “Satan’s plan in the beginning was to compel. He said he would save all men and not one soul should be lost. He would do it if the Father would give him the honor and the glory. But who wants salvation when it comes through compulsion, if we have not the power within ourselves to choose and to act according to the dictates of conscience? What would salvation mean to you if you were compelled?”[17]

President Smith’s question is a fair one, and it raises yet another: Who indeed would subscribe to a plan that proposed total compulsion for every action? Is such a plan even plausible on its face? Consider the following thought experiment, quoted in a still-current Church curriculum manual, where, in a much older article from the Improvement Era, agency is again characterized primarily as freedom of action:

Even before we came to earth, we were required to choose whether we would follow God’s plan and be free to act as we chose or to follow Satan and act under force. . . .

“Suppose we take a child and arrange to rear him as Satan suggested, so that he cannot make the smallest mistake. We tell him exactly what to do, how to do it and when to do it; and then make sure he conforms to orders. We never let him make choices, never let him try different solutions to problems of everyday living. He must not be allowed to err. Year by year the child’s body will grow, but what of his mind? What of his spirit? Though he grow to be six feet tall, he will never become a mature adult. His mind and spirit will have been starved. They will have failed to grow for lack of nourishment.” (Lester and Joan Essig, “Free Agency and Progress,” Instructor, Sept. 1964, 342)[18]

This proposal actually highlights one of the biggest difficulties inherent in the “forced obedience” interpretation of Lucifer’s proposal. Freedom of action and thought, however trammelled, is so integral to human existence that it is difficult to imagine, even for purposes of a thought experiment, conditions under which it could be totally abridged. President Spencer W. Kimball, who also appears to have held the interpretation being discussed here, had this to say:

There was rebellion in the ranks. The proposed program called for total controls by each individual of his personal life, including restraints, sacrifices, and self-mastery. . . Had the rebels won that great war you and I would have been in a totally different position. Ours would have been a life under force. You could make no decisions. You would have to comply. Every determination would be made for you regardless of your will. Under compulsion you would do the bidding of your dictator leader in whose image the Khrushchevs, Hitlers, Napoleons, and Alexanders were but poor and ineffectual novices in comparison. Your life would be cut out for you and you would fit into the mold made for you.[19]

It is a sad fact of human history that some people have attempted to totally control the minds and compel the actions of other people, and the results of such experiments have been indeed horrific. But even these extreme examples do not approach the totalitarian proposal that is presumed to have been Lucifer’s plan under this interpretation. The devil would have removed from each soul the very ability to think and the capacity even to will—let alone perform—actions that were alternative in any way to those prescribed by him. A family of mindless automatons, to use President Smith’s term, or puppets, to use David O. McKay’s, is the picture that emerges,[20] which returns us to the question: Is it likely that a third part of the hosts of heaven—untold numbers of spirits—would have subscribed to such a patently malicious and injurious proposal, even if Lucifer had made a most cunning and masterful pitch? Would so many souls have wanted and voted for such a fate? And yet the scriptures say that Lucifer sought to destroy the agency of man. What else could his proposal have entailed if not total control of all human actions? Is not agency indeed the freedom to act? How else than by removing that freedom could Lucifer have “sought to destroy the agency of man?”

A possible answer is suggested in the scriptures. In 2 Nephi 2:27, Lehi teaches that men “are free to choose liberty and eternal life, through the great Mediator of all men, or to choose captivity and death, according to the captivity and power of the devil.” In speaking of individual freedom to choose, Lehi’s emphasis is not on actions, but on ultimate outcomes (eternal life or eternal captivity). This is crucial to understanding agency in its fullest sense and what is at stake with each moral choice. Every daily decision—each act taken, each thought entertained, each word spoken—orients the soul towards one or the other of the ultimate outcomes of which Lehi speaks. Children of God are engaged, deed by deed, in a process of becoming, and it is what each soul is to become as a result of day-to-day and moment-by-moment choices that is most at stake when we speak of agency. This leads us to the other interpretation that has been given of Lucifer’s counterproposal to the Father’s plan.

The “Unconditional Redemption” Reading

“Here am I, send me,” said Lucifer to the Father, “I will be thy son, and I will redeem all mankind, that one soul shall not be lost, and surely I will do it; wherefore give me thine honor” (Moses 4:1). Rather than interpret this proposal as an attempt to make puppets and automatons of the human race, a number of Church leaders have interpreted it as Lucifer offering a universal and unconditional redemption from sin as well as from death. There are several hints in Lucifer’s language that support this interpretation. For example, he says, “I will be thy son.” What did he mean by that? Was he not already, at the time of the Council, a spirit son of God? The Church’s teachings on this point have consistently held that he was. Then what was he suggesting? The answer inevitably appears to be that he was seeking to become the Only Begotten Son of the Father in the flesh—the Redeemer—a position we know that he continued to covet even after he had been cast down.[21]

The unique mission of the Only Begotten Son, as outlined from the beginning by the Father, was to overcome the everlasting effects of sin and death by coming into mortality, born of a mortal woman but with the immortal capacities of God the Father. In this capacity, the Son of God would have power to suffer beyond what anyone else could suffer “except it be unto death” (Mosiah 3:7) and the power to lay down his life and take it again (John 10:17–18, Ether 12:33) in order to loose the bands of death for all mankind. Lucifer, according to the “unconditional redemption” interpretation of Moses 1:4, was ostensibly proposing to do all of this, but with a crucial difference. Joseph Smith characterized it this way: “The contention in heaven was—Jesus said there would be certain souls that would not be saved; and the devil said he could save them all, and laid his plans before the grand council, who gave their vote in favor of Jesus Christ. So the devil rose up in rebellion against God, and was cast down, with all who put up their heads for him.”[22]

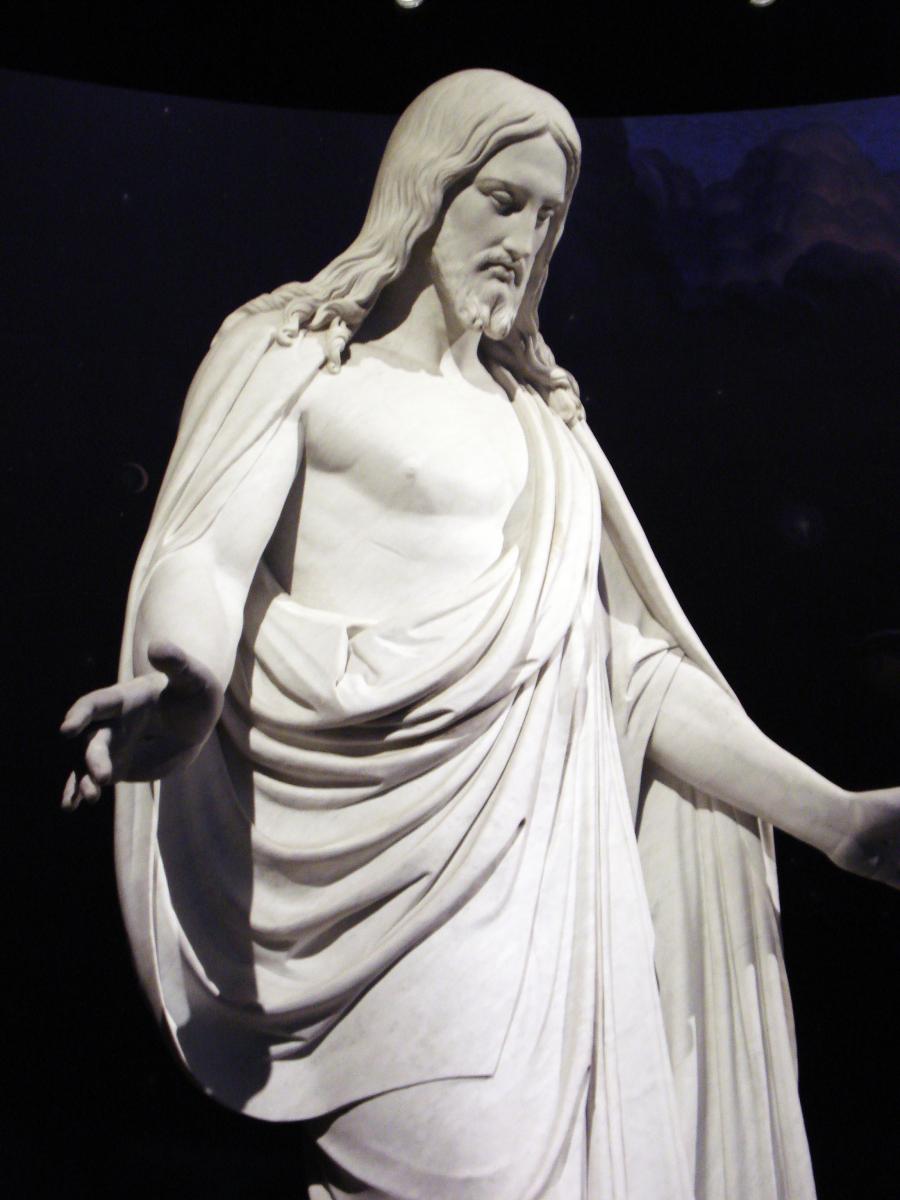

As the Son of God, Jesus had power to suffer beyond what anyone else could suffer and the power to lay down his life and take it again.

As the Son of God, Jesus had power to suffer beyond what anyone else could suffer and the power to lay down his life and take it again.

By detailing the implications of the Father’s plan as espoused by Christ (that some souls would not be saved due to their freely made choice to reject Christ’s grace), Joseph Smith seems to be suggesting that what was at stake was not whether souls would be allowed to sin, but whether or not they would be allowed to choose salvation from sin after the fact, or be compelled in their salvation. Such a reading is supported by the language of Moses 4:1, where Lucifer proposes to “redeem” all “that one soul shall not be lost.” The primary meaning of redeem is to retake or reclaim, and in the religious sense “to free from the consequences of sin,”[23] not to avoid a loss or to prevent sin from occurring in the first place. On this reading, Lucifer’s proposal was to save all mankind in their sins. This is unambiguously the way President Brigham Young understood the matter when he elaborated his own version of the dialogue in heaven, beginning with the Father’s question:

“Who will redeem the earth, who will go forth and make the sacrifice for the earth and all things it contains?” The Eldest Son said: “Here am I”; and then he added, “Send me.” But the second one, which was “Lucifer, Son of the Morning,” said, “Lord, here am I, send me, I will redeem every son and daughter of Adam and Eve that lives on the earth, or that ever goes on the earth.” “But,” says the Father, “that will not answer at all. I give each and every individual his agency; all must use that in order to gain exaltation in my kingdom; inasmuch as they have the power of choice they must exercise that power. They are my children; the attributes which you see in me are in my children and they must use their agency. If you undertake to save all, you must save them in unrighteousness and corruption.”[24]

Note that this version specifically indicates that an atoning sacrifice (“the sacrifice for the earth and all it contains”) was required, and that, by asking to be the one sent, Christ and Lucifer each signaled that they were willing to offer it. But Lucifer, according to this interpretation, wanted to use his sacrifice to save God’s children in—not from—unrighteousness and corruption.

President Young’s interpretation finds resonance in the more recent writings of Elder Bruce R. McConkie. He, too, indicates his reading of Moses 4:1 by way of offering a restatement of the dialogue in Heaven. Lucifer, he suggests, was saying: “I reject thy plan. I am willing to be thy Son and atone for the sins of the world, but in return let me take thy place and sit upon thy throne. Yea, ‘I will ascend into heaven, I will exalt my throne above the stars of God; . . . I will be like the most High’” (Isa. 14:13–14).[25]

On Elder McConkie’s reading, as with Brigham Young’s, Lucifer was offering to perform an atonement of some kind as God’s Only Begotten (note that he capitalizes “Son” in his paraphrase). The difference would be that instead of an atonement in which forgiveness of sin would be conditioned on faith, repentance, baptism, etc., Lucifer would offer an atonement that could ostensibly save all souls universally and unconditionally. Furthermore, since Lucifer would be the one to “make the sacrifice,” acting in the office of God’s Only Begotten Son, he was demanding that the glory should be given to himself for the salvation of God’s children.

An interesting variation on this reading of Lucifer’s proposal is found in the writings of President John Taylor. He also held the view that a redemptive sacrifice would somehow be required under Lucifer’s proposal, but he suggested that rather than offering himself as the one who would make the necessary sacrifice, Lucifer may have intended to make each person pay for their own sins in some way:

Satan (it is possible) being opposed to the will of his Father, wished to avoid the responsibilities of this position [as redeemer], and rather than assume the consequences of the acceptance of the plan of the Father, he would deprive man of his free agency, and render it impossible for him to obtain that exaltation which God designed. It would further seem probable that he refused to take the position of redeemer, and assume all the consequences associated therewith, but he did propose, as stated before, to take another plan and deprive man of his agency, and he probably intended to make men atone for their own acts by an act of coercion, and the shedding of their own blood as an atonement for their sins; therefore, he says, “I will redeem all mankind, that one soul shall not be lost; and surely I will do it; wherefore, give me thine honor.”[26]

It is more difficult to imagine on what basis Lucifer would claim all the glory for himself under this scenario, since the suffering for sin would devolve upon the sinners rather than upon himself. Perhaps it was enough that he had proposed the plan and on that basis he wanted to claim all the glory for its eventual “success.” In any case, the guilt of sinners is presumed here as well. The only question is whether forgiveness and redemption would be conditioned upon their desire for it, or whether they would all receive atonement by compulsory means.

While these speculations on the mode of atonement proposed by Lucifer may vary, the core understanding that Lucifer was proposing to save men unconditionally and universally despite their sins predominates in the statements of the earliest presidents of the Church and is articulated afresh in modern times by Bruce R. McConkie.

According to the unconditional redemption scenario, rather than being turned into automatons, persons under Lucifer’s plan would be free to act as they wished and heaven would be the reward regardless of their actions. Stated this way, unconditional redemption offers a stronger explanation as to why Lucifer’s proposal might have persuaded a third part of the hosts of heaven to rebel against the Father and follow Lucifer to perdition. The notion of being rendered a puppet (forced obedience) seems far less appealing than the free pass idea of unconditional redemption. If human nature here in mortality is any guide to what mankind’s propensities might have been in premortal life, then surely unbounded freedom and escape from negative consequences for behavior are more appealing than to be subject to the whims and dictates of someone in total control of life in every way. People here below will fight to the last drop of blood for their freedom, but once freedom is secured in some measure, many people will, like Cain, go to great lengths to skirt the law, get something for nothing, hide their misdeeds, and evade any consequences for wrongdoing. Everything from notions of salvation without works, to abortion, to exploitation of the poor, to fraudulent business practices may be seen as manifestations of this proclivity. If this intuitive appraisal of human nature is granted, it would seem that Lucifer’s plan, in order to win the numbers that it did, must have appealed to this notion of effortless salvation for all rather than to some desire to be dominated and controlled at every turn—an impulse that is still scarce to be found in human nature. For these reasons, I find the unconditional redemption version of Lucifer’s proposal (in its basic outlines at least) to be the most plausible, and it is this interpretation and its ramifications that will be considered for the balance of this essay.

The Justice of God and the Agency of Man

Lucifer’s proposal was too good to be true. His “plan” for saving all souls may have made a great presentation, but the devil was literally in the details. His proposal was both malicious and insidious. It violated at least two inviolable principles: the justice of God and the agency of man.

Saving persons in their sins, not from them, was incompatible with the justice of God, as the Book of Mormon dialogue between Zeezrom and Amulek makes clear:

And Zeezrom said again: Who is he that shall come? Is it the Son of God?

And he said unto him, Yea.

And Zeezrom said again: Shall he save his people in their sins? And Amulek answered and said unto him: I say unto you he shall not, for it is impossible for him to deny his word. . . .

And I say unto you again that he cannot save them in their sins; for I cannot deny his word, and he hath said that no unclean thing can inherit the kingdom of heaven; therefore, how can ye be saved, except ye inherit the kingdom of heaven? Therefore, ye cannot be saved in your sins. (Alma 11:32–34, 37)

Salvation without conditions, without requirements for obedience to law or repentance for violations of that law would have the effect of rendering any such law meaningless. There might as well be no law at all. And if so, there might as well be no lawgiver. The justice of God would be destroyed and, if it were possible, God would cease to be God. This annihilating logic is spelled out scripturally in Lehi’s monumental discourse in 2 Nephi 2:

And if ye shall say there is no law, ye shall also say there is no sin. If ye shall say there is no sin, ye shall also say there is no righteousness. And if there be no righteousness there be no happiness. And if there be no righteousness nor happiness there be no punishment nor misery. And if these things are not there is no God. And if there is no God we are not, neither the earth; for there could have been no creation of things, neither to act nor to be acted upon; wherefore, all things must have vanished away. (2 Ne. 2:13; see also Alma 42)

It is precisely this kind of catastrophic collapse of divine law and divine justice that Lucifer’s proposal would have set in motion.

But what of moral agency? Under unconditional redemption, people would have been granted maximum freedom of action with no lasting jeopardy to themselves. While this approach at first might seem to enhance individual freedom and autonomy, in the broader analysis it destroys agency by violating the law of consequences. The Encyclopedia of Mormonism discusses this law succinctly:

To be an agent means both being able to choose and having to choose either “liberty and eternal life, through the great Mediator” or “captivity and death, according to the captivity and power of the devil” (2 Ne. 2:27–29; 10:23). A being who is “an agent unto himself” is continually committing to be either an agent and servant of God or an agent and servant of Satan. If this consequence of choosing could be overridden or ignored, men and women would not determine their own destiny by their choices and agency would be void.[27]

Though mankind would be saved despite “unrighteousness and corruption,” they would also be saved whether they wanted it or not. Like forced obedience, the unconditional redemption scenario results in persons having no choice in the matter of their salvation. Salvation ostensibly would have been accomplished either by Lucifer’s fiat, or by an unconditional atonement that he performed and then imposed upon all, or by an atonement that he compelled all to undergo themselves. Whatever the case, his plan was indeed a plan of compulsion, but compulsion at a different point or on a different basis than simply controlling individual actions. It destroyed the opposition between sin and righteousness and obliterated the need for genuine repentance, allowing an anything-goes state of universal anarchy while claiming—or rather insisting—that somehow all people would irresistibly be saved. Everyone would be compelled into heaven.

Elder McConkie put it this way:

Lucifer sought to dethrone God . . . and to save all men without reference to their works. He sought to deny men their agency so they could not sin. He offered a mortal life of carnality and sensuality, of evil and crime and murder, following which all men would be saved. His offer was a philosophical impossibility. . . .

Lucifer and his lieutenants preached . . . a gospel of fear and hate and lasciviousness and compulsion. They sought salvation without keeping the commandments, without overcoming the world, without choosing between opposites. (Bruce R. McConkie, Millennial Messiah, 666–67)

Note that Elder McConkie is suggesting that the very notion of sin would have become void under Lucifer’s lawless proposal. As a result, “righteousness could not be brought to pass, neither wickedness, neither holiness nor misery, neither good nor bad” (2 Nephi 2:11) because his plan would have erased these distinctions—not because people would be compelled to be righteous. “Hell” would have become a null concept, and “heaven” would have been populated with every kind of morally recumbent soul. Such a place, of course, ceases to be heaven in any meaningful way. Hence the “philosophical impossibility,” to use Elder McConkie’s characterization, of Lucifer’s plan for totalitarian exaltation.

To Become or Not to Become

Moral agency is more than just the power to act; it is the freedom to become. Individual agency and Christ’s Atonement make it possible to become as God is—or not. Agency is the freedom to put on the nature of Christ by obeying his word (his law and covenant) and by freely seeking and freely receiving his redeeming and compensating grace—or not.

But why would anyone choose not to be saved? Why would anyone deliberately reject God and his proffered gift of exaltation and eternal life? Here is a question that gets to the very heart of what it means to be free and what it means to be saved. Once again, the problem arises only when we lose sight of the principle of becoming. We choose “liberty and eternal life” or “captivity and death” not in a single, once-and-for all decision, but through a series of decisions—an accrual of countless choices under myriad circumstances, each one of which has the effect of orienting us more or less towards one or the other of those ultimate outcomes. To be obedient is a choice, to sin is a choice, and to repent is also a choice.

Ultimately, the Atonement makes available to each soul the power to become like Christ through a pattern of choices—made or amended through the grace of Christ—that lead to oneness with the Father. The Atonement makes this possible because God’s grace gives strength beyond each person’s own, but also because it gives second chances, third chances, fourth chances, and so on. If it were not for the Atonement, each person’s first sin would be spiritually fatal. It is the Atonement that allows the Father’s plan to function as a saving process for his children, rather than an all-or-nothing, now-or-never proposition. It is the Atonement that makes it possible for persons to learn by doing, liberated from the paralyzing fear that, spiritually speaking, the slightest misstep would be their last. But even the Atonement cannot guarantee success if the patient is not patient.

To be one with the Father is eternal life; anything less is not. But this is a station, taught Joseph Smith, at which no one arrived in a moment.[28] Anyone can raise their hand for salvation; but are they willing to undergo the tutoring and sometimes painful transformative work that the grace of Christ must perform upon them in order to convert them from their natural, carnal, and fallen state into creatures of grace, the children of Christ? The answer to this question cannot be given with the lips; it must be given in the authentic, counterfeit-proof currency of actual effort—of work and sacrifice and sustained faith. To be saved, in the fullest sense, means nothing less than to become like Christ, acquiring his attributes and forsaking all else. Anything short of growing “unto the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ” (Ephesians 4:13) is to take his name in vain.

It requires more than mere assent to Christ’s Lordship to do this. Jesus himself proclaimed, “Not every one that saith unto me, Lord, Lord, shall enter into the kingdom of heaven; but he that doeth the will of my Father which is in heaven” (Matthew 7:21). The surest way to signal one’s desire to be like Jesus is to actually try to be like Jesus. Such an effort will be imperfect and will inevitably fall short of the goal without God’s grace, but the effort itself is crucial. Salvation is and must be the result of due diligence on the part of both the Savior and the saved. The Savior has abundantly fulfilled his mission of rescuing love. His arms of mercy are extended toward each soul as far as he can possibly reach without infringing individual agency. The free choice of each soul to be rescued by him is proven in the effort each makes to reach back in return.

Final Thoughts

It is significant that the first hymn in the first hymnbook of the restored Church emphasizes the point and promise of moral freedom or agency:

Know then that ev’ry soul is free,

To choose his life and what he’ll be;

For this eternal truth is given,

That God will force no man to heaven.

He’ll call, persuade direct him right;

Bless him with wisdom, love, and light;

In nameless ways be good and kind;

But never force the human mind.

It’s my free will for to believe,

’Tis God’s free will me to receive:

To stubborn willers this I’ll tell,

It’s all free grace, and all free will.[29]

God himself exercises agency and has consistently and resolutely respected and defended the right of his children to make crucial choices for themselves. Agency is welded to the law of consequences from which God exempts neither himself nor his children. Whenever people suppose they can somehow circumvent this law, the outcome is inevitably sorrow and lost opportunity for growth. The more faithfully God’s children freely adhere to his plan, the greater their progress in becoming like him, and the greater their growth and happiness.

Whether one is persuaded more by the forced obedience interpretation of what took place in the premortal Council in Heaven or the unconditional redemption interpretation, we can speak of these matters with sufficient care and precision as to avoid inaccuracy when teaching about agency. For example, when discussing the Council in Heaven, it is accurate to state that Lucifer’s proposal would have destroyed the agency of all mankind. Depending on the circumstance, one may further acknowledge that there are different versions of how his proposal would have functioned: either he was going to compel righteousness or he was going to save all with regard neither to their works nor their desires. In either case the outcome would have been the destruction of moral agency and the overthrow of God and his plan of happiness for his children.

The unconditional redemption reading of Lucifer’s proposal holds greater explanatory power for why so many premortal spirits were persuaded by him and aligned themselves with his impossible attempt to supplant God. Furthermore, attention to this option is worthwhile because it demands a richer view of what moral agency fully is—the power and freedom not just to act but to become according to our wills. But until further authoritative clarification of the issue—that is, more revelation—becomes available, this point of ambivalence is open to further study. In either case, the good news of the gospel is that endless possibilities are enfolded within the single point where human agency meets the grace of God through the Atonement of Jesus Christ.

Notes

An excellent article by Kevin M. Bulloch on a similar theme as this essay was recently published in Religious Educator 11, no. 1. Each of us composed and submitted our work for publication unaware of the other. Taken together, the two articles bear witness to the significance of the points upon which they coincide even as each makes a unique contribution to a discussion of the subject.

[1] See Bruce R. McConkie, “The Purifying Power of Gethsemane,” Ensign, May 1985, 11.

[2] For examples, see some of the quotes appearing later in this essay. A fairly late example of the use of the term free agency in official Church media is “Our Heavenly Father’s Plan,” a video produced in the mid-1980s to introduce the gospel message to people outside of the Church.

[3] “How Great the Wisdom and the Love,” Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), no. 195; emphasis added.

[4] C. Terry Warner, “Agency,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow, (New York: Macmillan, 1992).

[5] For the Strength of Youth (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2001), 4.

[6] Boyd K. Packer, “Our Moral Environment,” Ensign, May 1992, 66; see D&C 101:78. As early as 1987, Elder Dallin H. Oaks had noted that the term “free agency” was not scriptural and could be confusing. See “Free Agency and Freedom,” Brigham Young University 1987–88 Speeches (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1988), 1.

[7] 2006 Outline for Sharing Time and the Children’s Sacrament Meeting Presentation: I Will Trust in Heavenly Father and His Son, Jesus Christ, Their Promises Are Sure (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2006), 2.

[8] Preparing for Exaltation: Teacher’s Manual (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1998), 8.

[9] D. Todd Christofferson, “Moral Agency,” in Brigham Young University 2005–2006 Speeches (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 2006), 1.

[10] J. Reuben Clark Jr., in Conference Report, October, 1949, 193; quoted in Doctrines of the Gospel Student Manual: Religion 430 and 431 (Salt Lake City: Church Educational System, 1986), 15.

[11] “I Have a Plan,” My Turn on Earth, words by Carol Lynn Pearson, music by Lex de Azevedo (Salt Lake City: Embryo Music, 1977).

[12] James E. Talmage, Jesus the Christ (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1982), 8; emphasis added.

[13] I am aware that this summary of forced obedience does not address the question of whether there would even be a law to be obeyed or, indeed, any standard of righteousness to be met under Lucifer’s proposal. Such a question is certainly germane to an analysis of agency, and it will be addressed below. It does not enter in at this point, however, because the fact is simply that many people interpret Moses 4:3 as saying that Satan was somehow going to compel all people to be righteous—that is, to commit no sin but choose the right always—and the analysis stops there. It is assumed that there would be a standard of righteousness to be met for salvation, even under Lucifer’s proposal.

[14] For the purposes of this paper, I regard as current any curriculum material available through the Church’s official website, www.lds.org.

[15] In Conference Report, April 1950, 34–35; cited in Teachings of Presidents of the Church: David O. McKay (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2003), 207.

[16] Joseph Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation, comp. Bruce R. McConkie (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1954), 1:64–65; emphasis added.

[17] Joseph Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation, 1:70; emphasis added.

[18] The Latter-day Saint Woman: Basic Manual for Women, Part B, rev. ed. (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2000), 11–12. This manual is intended for use in developing areas of the Church where the full curriculum is not yet in use.

[19] Edward L. Kimball, ed., The Teachings of Spencer W. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1982), 32–33.

[20] Elder Dallin H. Oaks, drawing on the writings of President Joseph Fielding Smith, has also said that “under [Satan’s] plan, . . . we would have been mere robots or puppets in his hands.” “Free Agency and Freedom,” 3.

[21] A dramatic demonstration of this is found in Joseph Smith’s revealed account of Moses’ confrontation with Satan in Moses 1:12–19: “And it came to pass that . . . Satan came tempting [Moses], saying: Moses, son of man, worship me. And it came to pass that Moses looked upon Satan and said: Who art thou? For behold, I am a son of God, in the similitude of his Only Begotten; and where is thy glory, that I should worship thee? . . . Now, when Moses had said these words, Satan cried with a loud voice, and ranted upon the earth, and commanded, saying: I am the Only Begotten, worship me.”

[22] Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, ed. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 357; Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2007), 209. Although it is possible to give a more historically precise transcription of the records from which the version quoted here is derived, this account is sufficiently accurate for purposes of this essay.

[23] Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary, “redeem.”

[24] John A. Widtsoe, ed., Discourses of Brigham Young (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1954), 53–54, as cited in Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Brigham Young (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1997), 51; emphasis added. The fuller quotation in the Discourses seems to indicate a view on Brigham Young’s part that Lucifer would have adopted even the name Jesus Christ—or at least an identity as “Savior of the world”—and would have saved murderers who did no more than claim to repent and confess him.

[25] Bruce R. McConkie, The Promised Messiah (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1978), 50

[26] John Taylor, The Mediation and Atonement of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1888; reprint, Grandin Book, 1992), 96–97.

[27] Warner, “Agency.”

[28] Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, 51.

[29] “Know Then That Ev’ry Soul Is Free,” A Collection of Sacred Hymns, for the Church of the Latter Day Saints, Selected by Emma Smith (Kirtland, OH: F. G. Williams & Co., 1835), no. 1, verses 1, 2, and 5; emphasis added. A version of this same hymn is found in the current hymnal of the Church: “Know This, That Every Soul is Free,” Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), no. 240. The text is by an anonymous poet, Boston, ca. 1805.