Starving Our Doubts and Feeding Our Faith

Robert L. Millet

Robert L. Millet, "Starving Our Doubts and Feeding Our Faith," Religious Educator 11, no. 2 (2010): 105–119.

Robert L. Millet (robert_millet@byu.edu) was a professor of ancient scripture at BYU when this was written.

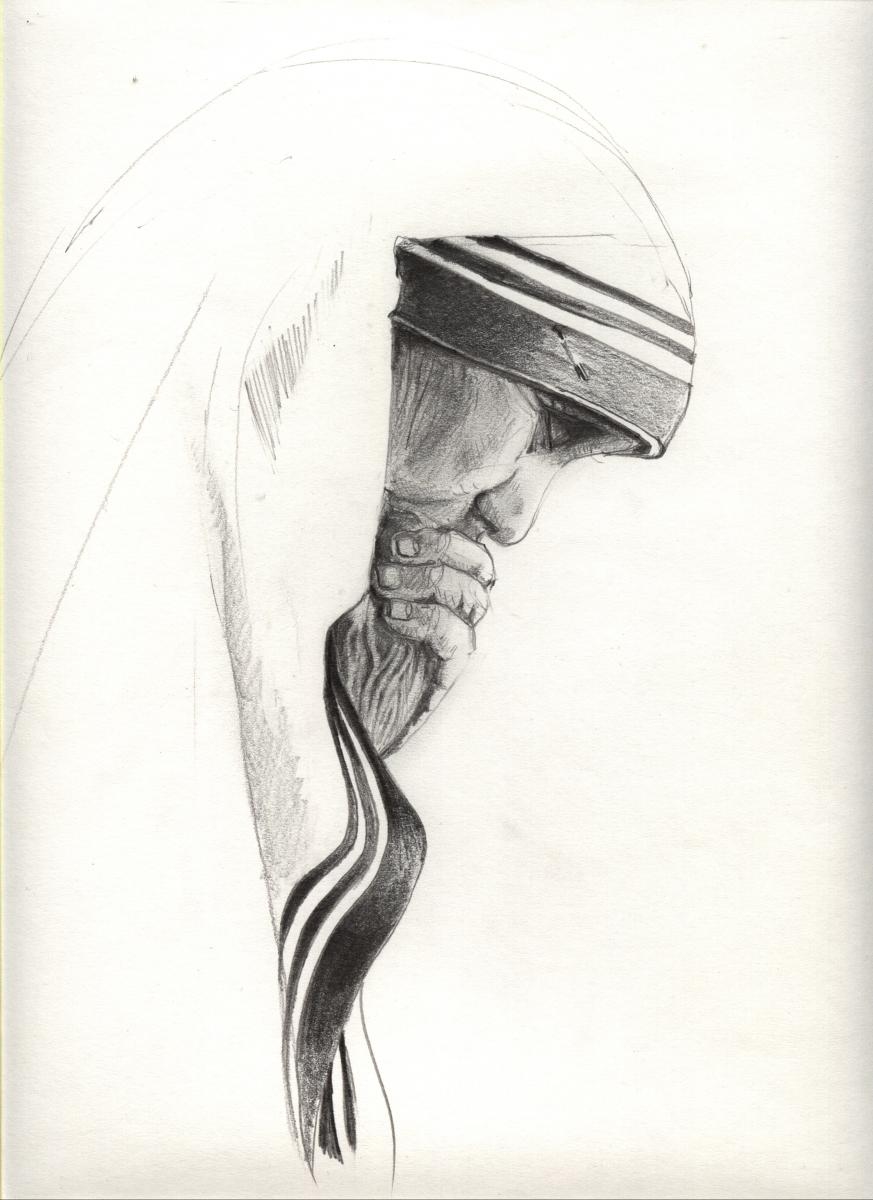

Mariola Kasprzak Paini, Artist of the Saints.

Mariola Kasprzak Paini, Artist of the Saints.

Mother Teresa of Calcutta lived and died a saint in the eyes of those who knew her. Though she inspired many during her ministry among the poor and needy, Mother Teresa herself struggled with feelings of loneliness and unrest.

As a professor at BYU, I have in the past year met with more students and mature members of the Church who are burdened with doubt and are on the verge of throwing in the towel and leaving the Church than I have met in the previous twenty-five years. Some wrestle with Church history issues, others with doctrinal matters. In every case, the person allowed his or her questions to morph into doubts, but this process is unnecessary. As Elder John A. Widtsoe pointed out, each of us will have questions so long as we are thinking, reflective human beings. Questions are a part of life, a vital part of growing in truth and understanding. But doubt should be only a temporary condition, a state that is resolved either through the serious pursuit and investigation of the matter under consideration—resulting in acquisition of new knowledge by study or by faith—or in a settled determination to place the question “on the shelf” for a time, at least until new insights or perspectives come to light. [1]

“Doubt is a perennial problem in the life of faith,” Oxford theologian Alister McGrath observed. “Doubt reflects our inability to be absolutely certain about what we believe. As Paul reminds us, we walk by faith, not by sight (2 Corinthians 5:7), which has the inevitable result that we cannot prove every aspect of our faith. This should not disturb us too much. After all, what is there in life that we can be absolutely certain about? We can be sure that 2 + 2 = 4, but that is hardly going to change our lives. The simple fact of life is that everything worth believing in goes beyond what we can be absolutely sure about.”[2]

That forward pursuit, in which we do not allow the unknown to distract or beset us, is called faith. Faith is in fact the antidote to doubt, the answer to skepticism, the solution to cynicism. It is “hope for things which are not seen, which are true” (Alma 32:21), an “anchor to the souls of men which [makes] them sure and steadfast, always abounding in good works, being led to glorify God” (Ether 12:4).

This is a topic worthy of an entire book at least, but in this article I would like to pursue two ways of dealing with doubt: learning to manage the seasons of unrest in our lives and taking the distant view as prerequisite to eventually seeing things as they really are.

Times of Darkness

“The gift of the Holy Ghost is the right to the constant companionship of that member of the Godhead based on faithfulness."[3] This definition of the gift of the Holy Ghost has been used for a very long time. While eternal life or exaltation is the greatest of all the gifts of God in the eternal scheme of things (see D&C 6:13; 14:7), the receipt of the Holy Ghost, given at the time of confirmation and administered by the laying on of hands, is a divine grace of immeasurable worth. “You may have the administration of angels,” President Wilford Woodruff stated, “you may see many miracles; you may see many wonders in the earth; but I claim that the gift of the Holy Ghost is the greatest gift that can be bestowed upon man.”[4]

The constant companionship. Constant! That word is a bit daunting. Why? Because I know by personal experience that I do not enjoy a constant flow of revelation, a constant effusion of discernment, a constant sense of comfort and confidence, or a constant outpouring of peace and joy. While I have miles and miles to go before I rest, at least in terms of cultivating the gift and gifts of the Spirit as I should, I know something about the precious privilege it is to have the Spirit’s direction and warmth. I know something about how vital it is to avoid ungodliness and worldly lusts and how diligently I have tried to be a dedicated disciple of the only perfect being to walk this earth. I guess you could say that I really do try to keep myself going in the commandment-keeping direction, knowing with a perfect certainty that the fulfillment I enjoy in this life and the eternal reward I hope to receive in the life to come are parts of the mercy and grace promised to the followers of the Christ.

My trust is in Jesus. My hope is in his atoning power to forgive my sins, cleanse my heart, transform my mind, and glorify my soul hereafter. But I do not always feel the Spirit in the same way from moment to moment or from day to day. How often have you had a magnificent and uplifting Sabbath, partaken reverently and introspectively of the emblems of the sacrament, been enlightened and motivated by the sermons and lessons delivered, searched the scriptures and discovered “new writing” as the Spirit directed your eyes and your attention to passages in holy writ that had special meaning that very minute, and knelt in prayer at the end of a supernal day and thanked a gracious God for his tender mercies? In short, how often have you closed the day on a spiritual high in which the Spirit of God like a fire was burning in your heart, only to awaken the next day with a very different feeling, one that caused you to notice that you did not feel the same Spirit you enjoyed only hours before; one, in fact, that prompted you to cry out, “What happened? Where did it go? What did I do? Was I wicked during the night without realizing it?”

Perhaps I am the only member of the Church of Jesus Christ to experience such a thing. But I do not think so. My guess is that each one of us has our spiritual highs and lows; but these are caused not by negligence or willful sin, not by a negative attitude or a critical or murmuring disposition, not by anything we have done wrong. So what’s going on? “The wind bloweth where it listeth,” Jesus said to Nicodemus, “and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit” (John 3:8). The word translated here as wind is the Greek word pneuma, which may also (as in Hebrew) be rendered as breath or spirit. It is as if Jesus had said, “The Spirit goes where it will, and you can hear the sound [also rendered as voice] but you cannot always tell where it came from or where it is going. So it is with each person who has been born again.” For one thing, the influence of the Spirit of God is not under our immediate direction or control. It cannot be called here or sent there according to human whim. It cannot be manufactured, elicited, or produced whenever we as humans desire it; however, we can certainly set the stage—we can prepare properly, listen to uplifting music, search the scriptures, pray, and ask humbly for the Spirit’s intervention or manifestation. But we cannot presume upon the motions or movement of this sacred spiritual endowment. “You cannot force spiritual things,” President Boyd K. Packer explained. “Such words as compel, coerce, constrain, pressure, demand do not describe our privileges with the Spirit. You can no more force the Spirit to respond than you can force a bean to sprout, or an egg to hatch before its time. You can create a climate to foster growth; you can nourish, and protect; but you cannot force or compel: You must await the growth.”[5]

Clearly you and I cannot enjoy the Spirit’s promptings or peace if we are guilty of unresolved sin, if we continue to pause indefinitely on spiritual plateaus, or if we persist in living well beneath our spiritual privileges. My impression is that all of us understand this. What we do not so readily understand is that the power of the Holy Ghost may come and go in terms of its intensity and its evident involvement in our lives. What President Harold B. Lee taught about testimony is true with respect to the work of the Comforter. He explained that our testimony today will not be our testimony tomorrow; a testimony is as fragile as an orchid, as elusive as a moonbeam.[6] In practical language, this means that we should take heart even when we do not feel the presence of the Holy Ghost with the same magnitude on a regular, ongoing basis.

In October of 2000, I experienced something I never had before—I went into a deep depression for several months. Oh, I’d had a bad day here and there before, had known frustration and disillusionment like everyone else, but I had never been trapped by the tentacles of clinical depression so severely that I simply could not be comforted and could not see the light at the end of the tunnel. For days at a time I only wanted to sleep or gaze at the walls and be alone. For weeks I felt as though I was in a closed casket, a prison cell that allowed in no light or sound whatsoever. I prayed. Oh, how I prayed for deliverance! I sought for and received priesthood blessings. I counseled with my friends who had known such pain and alienation from firsthand experience. One physician described my condition as “depletion depression,” meaning my body, my emotions, and my mind had chosen—whether I liked it or not—to take a vacation from normalcy. I had been driven for too long and could no longer live on adrenaline. I clung to my wife and children. I read the Liberty Jail revelations from the Doctrine and Covenants over and over, holding tenaciously to the words, “Thine adversity and thine afflictions shall be but a small moment” (121:7). Again and again I pleaded with my Heavenly Father, in the name of the Prince of Peace, to lift the pall, chase the darkness away, and bring me back into the light. It was so very dark and lonely out there!

During those weeks of suffering, I had great difficulty feeling the Spirit. In my head I knew that I was “worthy” in the sense that I was striving to live in harmony with the teachings of the Savior, but I simply did not feel the peace, joy, and divine approbation that I had come to expect and cherish. I was serving as a stake president at the time, and the First Presidency and my Area Presidency tenderly and kindly encouraged me to turn everything over to my counselors, take the break I needed, and follow my doctor’s orders, including using prescribed medication if needed. Let me see if I can state this more accurately: I knew in my mind, in my heart of hearts that the Lord was pleased with my life, but I did not feel close to God as I had felt only days and weeks before. This experience, which, by the way, thankfully passed within a short period of months, taught me something that was and is extremely valuable—namely, it is one thing to have the Spirit of the Lord with us, even the “constant companionship of that member of the Godhead,” and another thing to always feel that influence. Many, if not most times that the Spirit enlightens us, we feel it. Many, if not most times that we are being divinely led, we are very much aware of it. But there are occasions when the Holy Ghost empowers our words or directs our paths and, like the Lamanites who had been taught by Helaman’s sons Nephi and Lehi and enjoyed a mighty spiritual rebirth, we know it not (see 3 Nephi 9:20).

That is to say, there is a mental or intellectual component to spiritual living that is in many ways just as important as the emotional component. Sometimes God tells us in our minds, sometimes in our hearts, and sometimes in both (see D&C 8:2–3; 128:1). To take another example, I found as a priesthood leader that it was not uncommon at all to work with a person who had been involved in serious transgression and then watch with sheer delight as changes took place in their bearing and their behavior as the light of the Holy Spirit returned to their countenances. They were forgiven. The sin was now behind them. And yet they themselves could not let it go, could not forgive themselves, and strangely, sought to respond more to some sense of personal inner justice than to the workings of the Spirit and the word of their ecclesiastical leader. In many interviews in which I counseled such individuals to not look back and to move on with their lives, I found myself reading the following profound lesson from the Apostle John: “If our heart condemn us”—that is, if our overactive conscience continues to plague us after a remission of sins has been granted—we should remember that “God is greater than our heart, and knoweth all things” (1 John 3:20; emphasis added).

Seasons of Unrest

Each of us, at different times in life, encounters what we might call “seasons of unrest,” periods of time when we do not feel close to our Lord, when we feel unworthy, when we almost feel as though God has turned his back on us, or when we find ourselves filled with questions and perhaps even doubts. During such seasons, there are remarkable lessons to be learned from the saintly woman who came to be known to the world simply as Mother Teresa of Calcutta. Born in 1910 as Agnes Gonxha Bojaxhiu, this slight but spiritually sensitive soul determined early in life that she wanted to serve her Lord and Savior through loving and caring for the “poorest of the poor” in India. At age eighteen she traveled to Ireland to become a part of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a cloistered assembly of sisters dedicated to education.

In 1948 she received permission from her local authorities and from Rome to assume a different role as a nun—to go out into the streets; to visit the homes of the poor, the starving and emaciated, the sick and the dying; and to deliver to them tenderness and food and love and a kind word, including the word of salvation found in and through Jesus Christ. She had felt a specific call from God to do this in 1946. After establishing the congregation or ministry known as the Missionaries of Charity in 1948 and being named as its overseer under her local bishop, Mother Teresa’s work expanded and grew to fill the earth, and the poorest of the poor in many lands received the comfort, peace, sustenance, and dignity to which each person is entitled as a child of God. She continued her work, driven and directed by that charity that flows from heaven, until her frail and spent body gave up the ghost in 1997, leaving behind a legacy of love that will forevermore be celebrated. That’s the story.

Let’s take a moment, though, to consider the rest of the story, a poignant insight into Mother Teresa’s life that was not known by the public until 2007, the tenth anniversary of her death. Brian Kolodiejchuk, a member of the Missionaries of Charity, published a book entitled Mother Teresa: Come Be My Light and made known, for the first time, most of her personal correspondence, which revealed a secret that she had carried in her heart for some fifty years. You see, in spite of a lifetime spent in the service of God and her fellow mortals, spending decades of taxing and arduous labor and grueling hours devoted to the refuse and offscouring of society and almost fifty years of ministering to “the least of these” (Matthew 25:40), Mother Teresa’s life had also been one of pain, of emptiness, of spiritual alienation, of searching for comfort, of doubt and despair. The author explained, “Mother Teresa strove to be [the] light of God’s love in the lives of those who were experiencing darkness. For her, however, the paradoxical and totally unsuspected cost of her mission was that she herself would live in ‘terrible darkness.’” Mother Teresa wrote that from 1949 or 1950 “this terrible sense of loss—this untold darkness—this loneliness this continual longing for God—which gives me that pain deep down in my heart—Darkness is such that I really do not see—neither with my mind nor with my reason—the place of God in my soul is blank—There is no God in me—when the pain of longing is so great—I just long & long for God—and then it is that I feel—He does not want me—He is not there. . . . The torture and pain I can’t explain.’”[7]

Her season of unrest of almost fifty years actually caught her off guard; it was something that she had never anticipated in her wildest imaginations. And yet, in spite of it all, in spite of the doubt and the pain and the agony of loneliness—in spite of what she did not feel—she knew in her mind that God loved her, was reinforcing and upholding her, and would stand by her. In time she came to realize that her sufferings were divinely orchestrated by God to allow her to more closely identify with those she served—the lonely, the confused, the starving, the downtrodden—to allow her to know something of their pain. And with greater maturity she also came to know that her torturous personal agonies had been put in place to humble her, to drive her to her knees, to cause her to trust implicitly in the Lord Jesus Christ, and to allow her a glimpse into the nature of her Redeemer’s passion, his alienation, his rejection, his emptiness during the hours of Gethsemane and Golgotha. She became a fellow traveler on the road of pain, one who participated in the fellowship of his suffering.[8]

Mother Teresa certainly didn’t always live in the light, joy, peace, solace, and sweet refreshment that one would expect to be enjoyed by such a saintly person, but she possessed a faith in Jesus—a total trust, a complete confidence, and a ready reliance upon his merits, mercy, and grace—that transcended her bitter cup and gave her the unbelievable strength and enabling power to carry on her labors and maintain her optimism and tender tutorials to her sisters and coworkers. “Cheerfulness,” Mother Teresa wrote, “is a sign of a generous and mortified person who forgetting all things, even herself, tries to please her God in all she does for souls. Cheerfulness is often a cloak which hides a life of sacrifice, continual union with God, fervor and generosity.”[9]

David C. Steinmetz has written:

From time to time everyone endures a barren period in the life of faith. Prayers bounce off the ceiling unanswered. Hymns stick in one’s throat, and whatever delight one once felt in the contemplation or worship of God withers away.

In such circumstances Christians should “do what is in them”—that is, they should keep on keeping on. They should keep on with their prayers, their hymns of praise and their daily round of duties. Even though it seems like they are walking through an immense and limitless desert, with oases few and far between, they plod on, knowing that obedience is more important than emotional satisfaction and a right spirit than a merry heart.

To such people, “God does not deny grace.” They live in hope, however, that sooner or later the band will strike up a polka and the laughter and the dancing will start all over again. But if it does not—and it did not in Mother Teresa’s case—the grace that was in the beginning will be at the end as well. Of that, one can be sure. . . .

She did not abandon the God who seemed to have abandoned her, as she very well might have done. By doubting vigorously but not surrendering to her doubts, she became a witness to a faith that did not fail and a hidden God who did not let her go. That is what sanctity is all about.[10]

I still have moments and days of depression that creep into my soul unexpectedly, times when I feel confined and shrouded, gloomy and overwhelmed, but I have learned to work through it, to “keep on keeping on.” And yes, there are those times when questions arise, hard questions—whether challenges to doctrine or Church history—when I am stumped for a season or baffled for a time. But I will not give in to doubt or to fear. I know what I know, and I refuse to discard or belittle what I know because of some minuscule matter that my limited understanding cannot explain for the time being.

If a person received direct heavenly guidance in every aspect of their lives, Elder Orson Pratt asked, “Where would be his trials? This would lead us to ask, Is it not absolutely necessary that God should in some measure, withhold even from those who walk before him in purity and integrity, a portion of his Spirit, that they may prove to themselves, their families and neighbors, and to the heavens whether they are full of integrity even in times when they have not so much of the Spirit to guide and influence them? I think that this is really necessary, consequently I do not know that we have any reason to complain of the darkness which occasionally hovers over the mind.”[11] Similarly, Elder Richard G. Scott stated that we should take heart when no answer comes after extended prayer. “Be thankful that sometimes God lets you struggle for a long time before that answer comes. Your character will grow; your faith will increase. . . . You may want to express thanks when that occurs, for it is an evidence of His trust.”[12]

On many occasions the Spirit of the living God has whispered truth to my heart, verities that my head did not yet comprehend. I can wait. Far too many manifestations of divine favor and confirmations of the truth concerning scores of matters—coming through the Spirit and founded upon the rock of revelation—have come into my mind and heart for me to trip over the pebbles of what I do not yet understand. I will be patient. The Almighty has spoken in words and feelings that I cannot and dare not deny.

A Time of Decision

Many decisions, when made in earnest, when made with one’s whole heart, are extremely influential in our lives. I decided to marry Shauna Sizemore in the Salt Lake Temple in 1971. I decided that I would love her, cherish her, pray for her, provide for her, be a righteous example for her, and be attentive to her needs and deepest desires. Only she can say how well I have done that, but I have really tried to make her happy and secure. And all of this because of a decision.

I decided when I was very young that I would observe the Word of Wisdom all my days, that I would abstain from alcohol, tobacco, coffee, tea, and habit-forming drugs. My wife and I made a decision before we were married that our marriage would best be visualized as a triangle representing Shauna, Bob, and the Lord. Our individual lives and our marriage would belong to him. We decided that we would welcome children into our home, pay a full tithing, be active and involved in the Church, and accept and magnify callings. We have been married now for a little less than forty years and, despite the challenges and pain and vicissitudes of life that inevitably come to every marriage, ours has been a happy union. We have had our differences, our disagreements, our divergent views on things; but the idea of throwing in the towel and choosing to divorce has never been an option. We feel the influence of that Holy Spirit of Promise to whom it is given to bind and seal couples and families for eternity. We made an eternal decision. We have stuck with it. And that has made all the difference.

Almost thirty years ago a colleague and I were asked to read through, analyze, and look for patterns in a massive amount of anti-Mormon propaganda. It was drudgery. It was laborious. It was depressing. It carried a bitter and draining spirit, and consequently I had to just push my way through to complete the assignment. After a period of addressing certain questions, my partner shook his head and indicated that the constant barrage of issue after issue was simply wearing him down and he wasn’t sure he could stick with it. I pointed out that we were almost done, that a few more hours would be sufficient to make our report. He stared at me for a moment and asked, “This isn’t damaging to you, is it? I mean, you don’t seem to be very upset by what we are reading.” I assured my friend that there were obviously other things I would rather be doing and that the hateful and contentious spirit did in fact weigh on me, but no, I wasn’t particularly bothered by it. “Why?” he followed up. “I can’t say for sure,” I responded. “It’s ugly but it doesn’t really affect my faith.”

Not long ago I was in conversation with a friend of another faith. She began to ask about my impressions of some anti-Mormon videos on the Book of Mormon and the book of Abraham that had recently been released. I indicated that I had seen them and put them away. She asked, “Bob, this doesn’t cause you to wonder if you’re believing in a fairy tale?” “Of course not,” I replied. “This doesn’t make you doubt that Joseph Smith was a true prophet?” she inquired. “Not in the slightest,” I said. She then added, “I just don’t understand you!” Later that night as I laid in bed, I rehearsed that conversation, which reminded me of the one I had thirty years earlier. I asked myself: Why am I not unnerved by attacks on the Prophet Joseph, the Church, or its teachings? Why don’t these things challenge my mind or get to my heart? I wasn’t sure.

Not long afterward, I sat with my wife in our living room as we watched the April 2007 general conference. As I usually do, I took notes that would help remind me and my students of what was said—at least until the May issue of the Ensign came out. During the Sunday morning session, Elder Neil L. Andersen began his remarks by relating the very touching story told by President Gordon B. Hinckley in the April 1973 conference of a young Asian man who had joined the Church while in the military but later faced the sobering realities of ostracism by his family and foreclosure of future promotions in the military. “Are you willing to pay so great a price for the gospel?” President Hinckley had asked. “With his dark eyes moistened by tears, he answered with a question: ‘It’s true, isn’t it?’ President Hinckley responded, ‘Yes, it is true.’ To which the officer replied, ‘Then what else matters?’”

Elder Andersen continued:

The cause in which we are laboring is true. We respect the beliefs of our friends and neighbors. We are all sons and daughters of God. We can learn much from other men and women of faith and goodness. . . .

Yet we know that Jesus is the Christ. He is resurrected. In our day, through the Prophet Joseph Smith, the priesthood of God has been restored. We have the gift of the Holy Ghost. The Book of Mormon is what we claim it to be. The promises of the temple are certain. . . .

It’s true, isn’t it? Then what else matters? . . .

How do we find our way through the many things that matter? We simplify and purify our perspective. Some things are evil and must be avoided; some things are nice; some things are important; and some things are absolutely essential.

Then came the following words, words that have changed my life and provided answers to the question, Why doesn’t anti-Mormonism affect my faith? “Faith is not only a feeling,” Elder Andersen taught, “it is a decision. With prayer, study, obedience, and covenants, we build and fortify our faith. Our conviction of the Savior and His latter-day work becomes the powerful lens through which we judge all else. Then, as we find ourselves in the crucible of life, . . . we have the strength to take the right course.”[13]

That was it. That was the answer. Faith is a decision. Decades ago I made a decision: I determined that God is my Heavenly Father. I also decided that Jesus Christ is my Lord and Redeemer, my only hope for peace in this life and eternal reward in the life to come, and that Joseph Smith is a prophet of God, through whose instrumentality the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, the Pearl of Great Price, many plain and precious truths, the keys and covenants and ordinances of the priesthood, and the organization of the Church have been restored. I decided that I would be loyal to the constituted authorities of the Church, that I would not take offense when there came an either inadvertent or intended “ecclesiastical elbow,” as Elder Neal A. Maxwell used to call it.[14] I decided that I was in this race for the long haul, that I would stick with the Good Ship Zion and that I would die in the faith in good standing. No man or woman would ever chase me out of the Church. No unresolved issue or perplexing doctrinal or historical matter would shake my faith.

Now, I suppose some would respond that I am either living in denial or am simply naïve about troublesome problems. I assure you that I am neither. I am a religious educator, have been so for over thirty years, and am very much aware of seeming incongruities that pop up here and there. I spend a good portion of my time with people who are of different faiths, and some of them are ever so eager to bring to my attention questions intended to embarrass me or the Church. There are just too many things about The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that bring joy and peace to my heart, light and knowledge to my mind, and a cementing and sanctifying influence into my family and my interpersonal relationships for me to choose to throw it all away because I am uncertain or unsettled about this or that dilemma. To put this another way, the whole is much greater than the sum of its parts.

There is a very tender scene in the New Testament that comes to mind when I contemplate what it would mean to leave the Church or to take my membership elsewhere. When Jesus delivered his Bread of Life Sermon, a deep and penetrating message on the vital importance of partaking fully of the person and powers of the Messiah, many in the crowd at Capernaum did not understand and were even offended by the Master’s remarks. “From that time many of his disciples went back,” John records, “and walked no more with him. Then said Jesus unto the twelve, Will ye also go away?” What a poignant moment: our Lord seemed to display a sense of disappointment, a somber sadness for those in the darkness who could not comprehend the light. Would he be left alone? Was the price too great to pay? Was the cost of discipleship so expensive that perhaps even those closest to him would leave the apostolic fellowship? “Then Simon Peter answered him, Lord, to whom shall we go? Thou hast the words of eternal life. And we believe and are sure that thou art that Christ, the Son of the living God” (John 6:66–69; emphasis added). Once one has enjoyed sweet fellowship with Christ, how does he or she turn away? Where does one go? What possible message, way of life, social interaction, or eternal promise can even compare with what Jesus offers?

Many years ago I attended a symposium where a number of presentations on Mormonism were made, some of which were fairly critical of our faith and way of life. One man, a convert to the Church, spent the first two-thirds of his talk quipping about all of the silly, nonsensical, embarrassing, and even bizarre things that had happened to him since becoming a Latter-day Saint. The crowd roared. The laughter over the Church and its programs was cruel, painful to hear, and continued nonstop for almost an hour. And then the speaker became very sober and said, in essence: “Now all of this is quite hilarious, isn’t it? There are really some dumb things that happen within Mormonism. There are matters that for me just don’t add up, un-Christian behaviors that really sting, and situations that need repair. I think we all agree on that. But now let me get to the meat of the matter: I have spent many years of my life studying religions, investigating Christian and non-Christian faiths, immersing myself in their literature, and participating in their worship. I have seen it all, from top to bottom and from back to front. And guess what: there’s nothing out there that will deal with your questions, solve your dilemmas, or satisfy your soul. This gospel is all there is. If there is a true church, this is it. And so you and I had better become comfortable with what we have.” He stepped down from the podium as silence reigned in the room. His message had struck a chord.

Conclusion

Some years ago, my Evangelical–Latter-day Saint dialogue group—about twelve to fifteen of us who meet twice a year to discuss similarities and differences in doctrine—came together to consider the claim of Joseph Smith to be a prophet. The conversation, as always, was pleasant, cordial, and instructive. One of my Evangelical friends said at a certain point, “You have to understand that we as traditional Christians take the Savior’s warning against false prophets very seriously. This is why we just don’t jump on the bandwagon and accept Joseph Smith without serious reservations.” I spoke at that point: “We understand your position and can see where you’re coming from. But that same Lord, in that same chapter, said something that is just as deserving of our attention and ought to be a significant part of your assessment of Joseph Smith—when it comes to judging prophets, ‘ye shall know them by their fruits’ (Matthew 7:16). The fruits of Joseph Smith, including the people of the Church, their manner of life, the lay ministry, the missionary effort, the temples, the charitable work of the Church throughout the world—these are things that cannot be taken lightly.”

Some have wandered away from the Church because they did not exercise the kind of faith that required a decision. Consequently, when something went wrong or something else didn’t seem to make sense, they chose to avoid Church meetings and eventually the Church.

If you have allowed unanswered questions in your life to develop into destructive doubts, I plead with you to think through the long-term implications of a decision to distance yourself from the Church. Ponder on what you are giving up. Think carefully about what you will be missing. Reflect soberly on what you are allowing to slip from your grasp. If you are one who finds yourself struggling with a doctrinal question or a historical incident, seek help. Seek it from the right persons, including your Heavenly Father. Be patient. Be wise. Assume the best rather than the worst. If you are an otherwise active member of the Church who finds yourself overly troubled by something that should never have happened or something that can be remedied in your heart by simply recognizing that all of us are human and that forgiveness is powerful spiritual medicine, leave it alone. Let it go.[15] Keep the big picture and refuse to be bogged down by exceptions to the rule. Focus on fundamentals. Simplify your life and open yourself to that pure intelligence from the Spirit that is promised to us all, a state of mind and heart characterized by calmness and serenity.[16]

“Faith is basically the resolve to live our lives on the assumption that certain things are true and trustworthy,” Alister McGrath has written, “in the confident assurance that they are true and trustworthy. And that one day we will know with certainty that they are true and trustworthy.”[17] Have you made a decision? Have you made the decision? Have you sought for and obtained a witness from God that the work in which we are engaged is heaven-sent and thus true? If you have not, remember that such a quest is foundational to your future happiness and peace. Pursue it with fidelity and devotion. If you have received such a testimony, cherish it, cultivate it, and ask the Father in the name of the Son to broaden and deepen it. Then make the decision. Such a decision is a surrender to what you know in your heart of hearts to be true, even though you cannot necessarily see the end from the beginning.

As God’s light shines in our individual souls, it shines also on things of eternal worth in the external world. That is to say, the light within points the way to go, the path to pursue, the avenue to tread. Contrary to a world immersed in pure naturalism, when we are alive with faith, then for us, believing is seeing. C. S. Lewis, the great Christian writer who had such unusual insight into sacred matters, observed: “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.” [18]

Notes

[1] John A. Widtsoe, Evidences and Reconciliations (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1960), 31–33.

[2] Alister McGrath, Knowing Christ (New York: Doubleday Galilee, 2002), 79.

[3] Sermons and Writings of Bruce R. McConkie: Doctrines of the Restoration, ed. Mark L. McConkie (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1989), 125.

[4] Discourses of Wilford Woodruff, ed. G. Homer Durham (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1946), 5. See also Joseph Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation, 3 vols., comp. Bruce R. McConkie (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1954), 1:44.

[5] Boyd K. Packer, “That All May Be Edified” (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1982), 338; emphasis in original.

[6] Teachings of Harold B. Lee, ed. Clyde J. Williams (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1996), 139.

[7] Brian Kolodiejchuk, ed., Mother Teresa: Come Be My Light (New York: Doubleday, 2007), 1–2.

[8] St. John of the Cross (1542–91) spoke of “the dark night of the soul” through which one passes as a part of the divine purification that brings about a union with the Lord; see his Dark Night of the Soul, trans. and ed. E. Allison Peers (New York: Image Books, 1959).

[9] Kolodiejchuk, Mother Teresa, 33.

[10] David C. Steinmetz, “Growing in Grace,” The Christian Century 124, no. 22 (October 30 2007), 10–11; emphasis added.

[11] Orson Pratt, in Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 15:233.

[12] Richard G. Scott, “Using the Supernal Gift of Prayer,” Ensign, November 2007, 8–11.

[13] Neil L. Andersen, “It’s True, Isn’t It? Then What Else Matters?” Ensign, May 2007, 74–75.

[14] See, for example, Neal A Maxwell, “Why Not Now?” Ensign, Nov. 1974, 12.

[15] See Boyd K. Packer, in Conference Report, October 1977, 89–92; October 1987, 17–21.

[16] Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, comp. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 149–50.

[17] Alister McGrath, Doubting: Growing through the Uncertainties of Faith (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2007), 27.

[18] C. S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory (New York: HarperCollins, 2001), 140.