West German Mission

Roger P. Minert, “West German Mission,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 23–42.

The Main River flows from east to west through the city of Frankfurt, one of Germany’s most important cities. Famous for its role in finance, politics, literature, culture, and transportation, the city had 548,220 inhabitants in 1939. On the south bank of the Main is the quarter known as Sachsenhausen. Some of Frankfurt’s finest modern buildings lined that side of the river during the years leading up to World War II. One of those was Schaumainkai 41, the home of both the West German Mission office and the family of the mission president. Located at the corner of Schweitzerstrasse, the front windows of the building offered a fine view of the Main and the main part of the city on the other side of the river.

The missions of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the German-speaking nations of Europe were reorganized on January 1, 1938. For several decades, there had been two missions: the Swiss-German Mission, consisting of Switzerland and the western states of Germany, and the Austrian-German Mission, consisting of Austria and the eastern states of Germany. With the new year, three missions were constituted: the Swiss-Austrian Mission (with its office in Basel, Switzerland), the West German Mission (Frankfurt am Main), and the East German Mission (Berlin). In order to balance the populations of the missions in Germany, the Weimar District was moved from the East to the West. Philemon Kelly had been the president of the East German Mission since August 1937 but moved to Frankfurt in January 1938 to assume the leadership of the new West German Mission. [1]

| West German Mission [2] | 1939 |

| Elders | 359 |

| Priests | 165 |

| Teachers | 148 |

| Deacons | 317 |

| Other Adult Males | 864 |

| Adult Females | 2919 |

| Male Children | 303 |

| Female Children | 258 |

| Weimar District* | 337 |

| Total | 5670 |

*Detail not reported

| 1938 | East | West |

| Elders | 402 | 390 |

| Priests | 194 | 179 |

| Teachers | 243 | 161 |

| Deacons | 445 | 345 |

| Other Adult Males | 1245 | 939 |

| Adult Females | 4336 | 3172 |

| Male Children | 384 | 329 |

| Female Children | 358 | 280 |

| Total | 7,607 | 5,795 |

For a few weeks, President Kelly’s office was located in the Weber Inn at Weserstrasse 1, but a search began immediately for a more formal setting for the office. The West German Mission history reported the following success on Saturday, February 12, 1938:

New Mission Home Occupied. The new permanent headquarters for the West German Mission on Schaumainkai [41] were occupied on this day. All of the ceilings, walls, woodwork, fixtures and floors have been renovated and repaired. Although the office was completely bare at the time of occupation, before the end of the month sufficient furniture, equipment, utensils etc. had been installed to permit the home and office life to run smoothly. [3]

Fig. 1. The West German Mission (with districts identified) and the East German Mission of the LDS Church during World War II.

Fig. 1. The West German Mission (with districts identified) and the East German Mission of the LDS Church during World War II.

The new location in the upper-class neighborhood on the south bank of the Main River lent an air of respectability to the mission office. The affairs of the mission in general were in excellent condition at the time. Approximately eighty missionaries were serving in the mission in 1938, nearly all of them from the United States. The seventy branches of the Church were grouped in thirteen districts, and all of the auxiliary programs of the Church were functioning in Germany. [4] At the northern end of the mission was the Schleswig-Holstein District, and at the far southeast extent of the mission was the Vienna District.

Philemon Kelly’s work in Frankfurt lasted only a few months. In August 1938, he was released and succeeded by a dapper young businessman from Salt Lake City, Utah—M. Douglas Wood. Along with his wife Evelyn and his daughters Carolyn and Annaliese, President Wood arrived in Frankfurt on June 26, 1938. [5] He had served in the Swiss-German Mission in the early 1920s and was well suited to the task when he returned to Germany.

Fig. 2. The new home of the West German Mission office at Schaumainkai 41 in Frankfurt. The entrance was on the west side (right). The stairs in front of the building lead down to a promenade along the Main River. (G. Blake)

Fig. 2. The new home of the West German Mission office at Schaumainkai 41 in Frankfurt. The entrance was on the west side (right). The stairs in front of the building lead down to a promenade along the Main River. (G. Blake)

| Mission | East (Berlin) | West (Frankfurt) | Total |

| Districts | 13 | 13 | 26 |

| Branches | 75 | 69 | 144 |

Adolf Hitler (Germany’s chancellor since 1933 and also its president since 1934) had led the country to a position of prominence and power by the time the Wood family arrived in Frankfurt. The nation’s international influence was growing (thanks in part to the successful Olympic Games of 1936), its economy was flourishing, the military was increasing in size and strength, and most of the eighty million Germans were participating in their country’s recovery from the Great War that had ended in disaster nearly two decades earlier. The 13,500 members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were likewise contributing to and benefiting from the prosperity of the nation. Even many of those members who had once dreamed of immigrating to the United States felt increasingly secure in Germany and were becoming convinced that the Saints could be blessed for their efforts in building Zion there. [6]

| The Largest LDS Branches in Germany in 1939 | ||

| Branch | Membership | |

| 1 | Chemnitz Center | 469 |

| 2 | Königsberg | 465 |

| 3 | Hamburg-St.Georg | 400 |

| 4 | Dresden | 369 |

| 5 | Stettin | 359 |

| 6 | Leipzig Center | 328 |

| 7 | Nuremberg | 284 |

| 8 | Annaberg-Buchholz | 274 |

| 9 | Berlin Center | 268 |

| 10 | Breslau West | 265 |

Reacting to rumblings of impending war, the First Presidency in Salt Lake City directed President Wood to evacuate his American missionaries to the Netherlands or Denmark on September 14, 1938. The missionaries were pleased to return to their assigned areas three weeks later. [7] War had not begun, but tension in central Europe was beginning to mount, and the American missionaries found themselves the object of official curiosity at times. Perhaps the most serious incident was reported in the mission history on October 14, 1938:

Elders Royal V. Wolters and Allen Luke were sent to Switzerland because the police were on their trail. They had taken some pictures which the government had forbidden to be taken. The pictures were taken while the two of them were laboring in Hannoversch-Münden. They were sent to Brother Johann Kiefer in Saarbruecken, who is a photographer. Upon inspecting Brother Kiefer’s records, the police discovered the forbidden negatives and some months later he was arrested. The two elders were traced and would have been involved in the situation, but were transferred to Switzerland just in time to avoid being called in by the police. The investigation of Brother Kiefer and his part in the affair was carried to court in Saarbruecken, and quite some trouble made of it. [8]

Elders Wolters and Luke had taken pictures of military sites. Fortunately, no real damage was suffered by either the missionaries or the Saints, but greater caution was encouraged among the American missionaries. Many of those young men found the Hitler movement and the rearmament of Germany to be fascinating and believed that the developments had nothing to do with the United States. [9]

As Germany’s power and influence grew, Hitler initiated a series of “bloodless conquests” in Europe. One of those occurred on March 12, 1938, when the German army marched into Austria and peacefully occupied the entire country. Many of the citizens of this small nation had voted on several occasions since 1918 to be joined to Germany, but the League of Nations had forbidden the move. The German dictator asked no permission to annex the country, and the international community made no attempt to oppose the takeover. Austria’s new status in Germany’s Third Reich made travel for foreign missionaries between Austria and Switzerland difficult, so the decision was made to add Austria to the West German Mission. This organizational change was made with approval from Salt Lake City on November 1, 1938. [10]

The conference of the West German Mission held in Frankfurt in May 1939 was a wonderful event. The health of the branches and districts is evident from the ambitious program of the conference that lasted from Saturday until Monday, May 27–29. More than a thousand members of the Church registered for the conference, and some came from as far as nine hundred miles away. The different sessions of the conference were held in rented meeting halls in downtown Frankfurt. More than one thousand attended a testimony meeting on Sunday morning, six hundred attended the Relief Society session, and twelve hundred attended the evening session that included the performance of a play entitled Jesus of Nazareth. On Monday, the concluding event took place thirty miles to the west, where seven hundred Saints boarded a boat for a cruise on the Rhine River. Several members had to be turned away when the boat was filled to capacity. The mission history includes the following summary statement regarding the conference: “The entire conference was a huge success and far greater in extent and beauty than had even been hoped for. . . . The results of this conference are far reaching and the good it did in cementing bonds of understanding, friendship and cooperation in the work of the Lord in this mission can never [be] told.” [11]

Following the mission conference, President Wood conducted a conference for the full-time missionaries. They met in the rooms of the historic Frankfurt city hall (Rathaus-Römer) in the oldest part of the city.

![Fig. 3. The Frannkfurt city hall was decked out with the flag of the United States in May 1939. [12] (G. Blake)](/sites/default/files/pub_content/image/4737/WGM_Fig_3.jpg) Fig. 3. The Frannkfurt city hall was decked out with the flag of the United States in May 1939. [12] (G. Blake)

Fig. 3. The Frannkfurt city hall was decked out with the flag of the United States in May 1939. [12] (G. Blake)

Elder George Blake of Vineyard, Utah, had been serving in the West German Mission since November 1937. In early August, 1939, he was transferred from the southern German town of Durlach to the mission office. He listed the following persons who lived and worked in the office as of August 18:

Pres. M. Douglas Wood, his wife Evelyn, his daughters Carolyn (8) and Anna (16).

J. Richard Barnes, executive secretary

W. Elwood Scoville, financial secretary

Elmer Tueller, priesthood support

Arnold Hildebrand, Mutual Improvement Association (with the help of Evelyn Wood)

Sister [Hildegard] Heimburg, translation and lesson manuals

Sister [Ilse] Brünger, translation

Sister [Berta] Raisch, translation (replacing Sister Brünger)

Sister [Ilse] Krämer, maid and cook

Grant Heber [Baker], Sunday School and Primary Organizations

[George Blake, printing, ordering books, genealogy] [13]

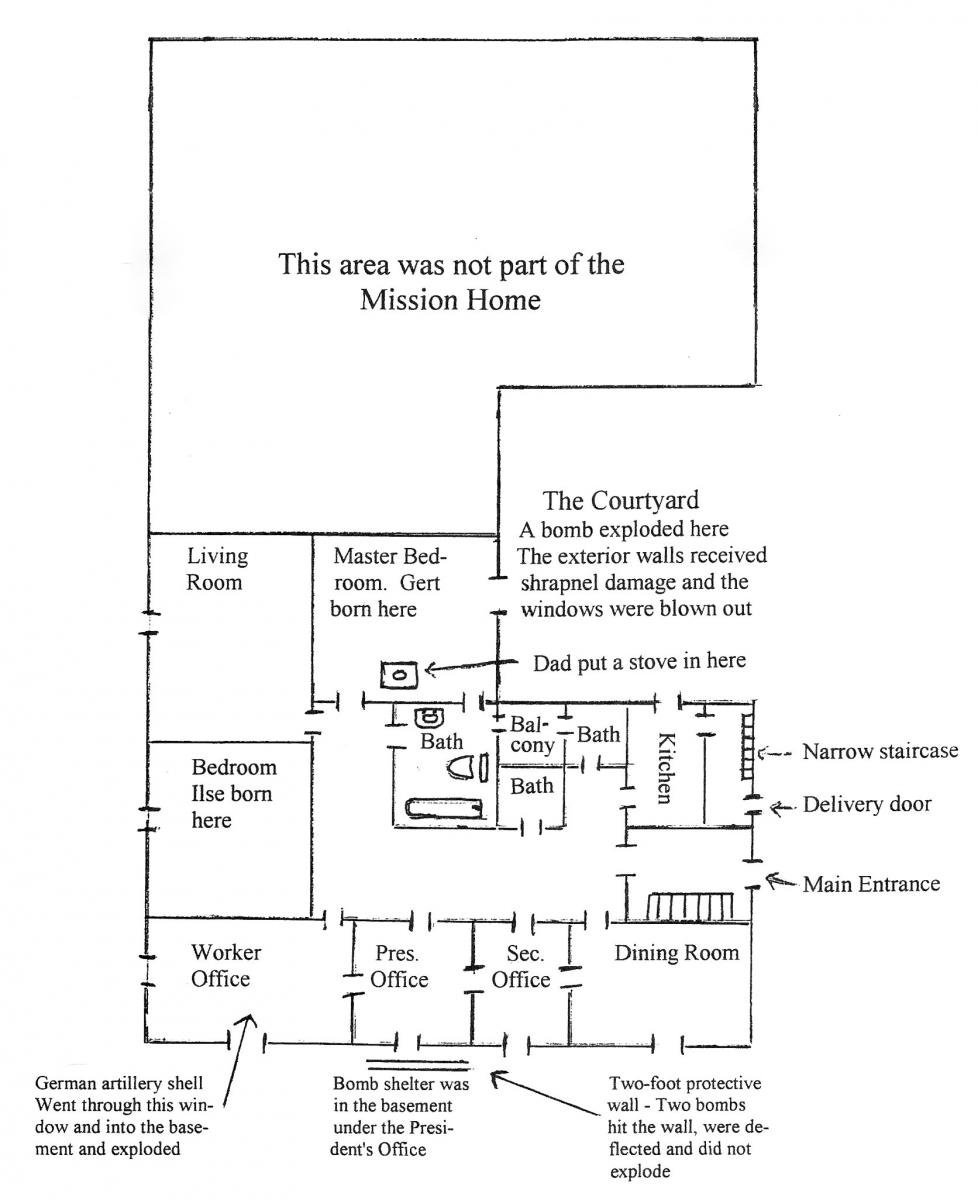

Elder Blake described the interior of the mission home in these words:

All six [American] missionaries lived in the attic. The Wood family lived on the second floor. The two secretaries were German ladies and they were . . . on the same or next floor up. . . . The church used the entire building and we were scattered throughout. The mimeograph room was in the basement. The entry was on the west side, not the front. The actual mission office was both the ground floor and the next one up. The ground floor was pretty much the church offices, with a nice waiting room and a large dining room and a couple of rooms for the secretaries. I don’t remember what was on the third floor. My desk with the mimeograph machine was in the basement. We had one big community dinner on the main floor with a large table, because we had fourteen to sixteen people and a couple of cooks. [14]

Elder Blake’s description of the routines in the building is both informative and entertaining:

As for the rules, they are quite loose. 7:30 in the morning is supposed to be class (only held when apostles or other good men come). 8:00 breakfast. 12:30 dinner. Usually have an hour after dinner for reading newspaper, taking pictures, napping, playing piano etc. 6:30 supper. After supper is free unless one is overworked (which is usually the case). Operas, movies, study, visiting etc. etc. Anna [Wood] usually wants to “quatch” (throw the bull) or wants someone to take her to the movies, but is otherwise O.K.! [15]

The West German Mission was experiencing a veritable golden age in the late summer of 1939, but national and international developments soon conspired to slow the Church’s progress. On Thursday, August 24, 1939, instructions arrived from the office of Church President Heber J. Grant in Salt Lake City that all American missionaries were to be evacuated from the countries of central Europe. When the message arrived in Germany, President Wood was touring the mission with Elder Joseph Fielding Smith. The two leaders and their wives were in the city of Hannover, where they were contacted on Friday by mission executive secretary, J. Richard Barnes, from the office at Schaumainkai 41. Elder Smith and President Wood immediately flew to Frankfurt to assess the situation. The instructions were repeated in more detail on August 25 in a telegram from President Grant to Elder Smith:

Have issued instructions to mission presidents in Holland, Denmark, Norway and Sweden to prepare to receive missionaries from Great Britain, Germany, France, and have instructed mission presidents in those latter countries to cooperate with American diplomatic representatives in evacuating the missionaries to Holland and Scandinavia. Will you kindly assume general charge and direction of this whole missionary situation. [16]

![Fig. 4. Elders Hillam and Welti were in Düsseldorf when they received this telegram instructing them to leave for the Netherlands immediately. “Assign tempory [sic] successor” meant that they were to appoint a temporary leader of the Düsseldorf Branch before departing. (C. Hillam)](/sites/default/files/pub_content/image/4737/WGM_Fig_4.jpg) Fig. 4. Elders Hillam and Welti were in Düsseldorf when they received this telegram instructing them to leave for the Netherlands immediately. “Assign tempory [sic] successor” meant that they were to appoint a temporary leader of the Düsseldorf Branch before departing. (C. Hillam)

Fig. 4. Elders Hillam and Welti were in Düsseldorf when they received this telegram instructing them to leave for the Netherlands immediately. “Assign tempory [sic] successor” meant that they were to appoint a temporary leader of the Düsseldorf Branch before departing. (C. Hillam)

The following message was sent to the mission office that same day by the United States consulate in Frankfurt:

CONFIDENTIAL

It has been learned that in view of the present tension in Europe, the American Embassy in Berlin is advising American citizens that it might be best to leave Germany. This advice, of course, does not imply that the Embassy or any officer representing the Embassy or any Consular Office can assume any responsibility in connection therewith, but each one who may act upon this suggestion or advice must do so at his own risk and responsibility. [17]

President Wood decided that a telegram must be sent to each pair of missionaries with instructions to leave for Amsterdam or Copenhagen without delay. The task fell to George Blake, as he recalled years later:

I was in the office the 24th [25th] of August and it was my job to go to the [telegraph] office to send the telegrams . . . one to each pair. It took me all day long because [the telegraph office] was jammed with official business. So they would take one or two and then they would wait for half an hour and then they’d take another one or two. . . . [President Wood] directed me to tell everyone to either go to Amsterdam or Copenhagen, and then they were supposed to wire back saying they’d received [the message]. [18]

Within days, all of the American missionaries serving in the West German Mission had been evacuated to the Netherlands or Copenhagen. [19] Based upon their experience in September and October 1938, the Americans were optimistic that they would soon be allowed to return to Germany to continue their service. However, the matter became doubtful on Friday, September 1, 1939, when the German army invaded Poland. Two days later, Great Britain and France honored their promises to resist Hitler’s plans for expansion of power in Europe by declaring war on Germany. What would become known as World War II had begun.

With his characteristic industry, President Wood continued to direct the activities of the mission from Copenhagen, and with the help of Elder Barnes wrote dozens of letters back to Frankfurt. A batch of letters was sent on September 8, 1939. The first was addressed to Friedrich Biehl, a member of the Essen Branch. Brother Biehl was designated the temporary leader of the mission and was authorized to retain all current mission office staff to assist him. Part of his instructions were as follows:

In localities where branches have diminished to exceedingly small numbers, and especially where there are no priesthood holders, it might be advisable to give up some of the [meeting halls]. . . . We don’t want to let our saints down, and we want to keep up their spirit in the gospel, but naturally we can’t keep up expenses very long where the income does not justify them. In cases such as this kind, it might be advisable to encourage the saints to hold regular meetings in their homes. . . . Some of the brethren from neighboring branches can pay them visits as often as it might be advisable and give them the sacrament. . . . I want to assure you that our faith and prayers are united for the saints there in Germany. As I said before, leaving you is the hardest thing that has come into our lives. We’re counting on you, and know that you will come through for us. [20]

Regarding decisions to be made in directing the mission, Wood expressed the following philosophy:

We feel it much more advisable to hold a strong central control, and try to save some of the expense in the smaller branches. Things will hold together much better with a strong center than if they are left too much to their own. For that reason, the office should be maintained, and some of the smaller branches closed, meetings being held in private homes. However, meetings should be held regularly where it is at all possible. [21]

President Wood then suggested that the rental of meeting rooms in the following cities be terminated as soon as the contracts allowed: Wilhelmshaven, Göttingen, Uelzen, Durlach, Saarbrücken, and Gotha. He recommended that the two branches in Wuppertal (Elberfeld and Barmen) be combined. Elder Biehl was then instructed to direct inquiries until further notice to President Thomas E. McKay, who had moved from Berlin to Basel as the temporary European mission president.

Also on September 8, President Wood wrote a personal letter to each of the five women living and working at Schaumainkai 41. Ilse Brünger was to serve as the mission secretary and office manager, [22] Hildegard Heimburg was to direct the activities of the auxiliary organizations, Berta Raisch was to keep the mission statistics and to assist Sister Heimburg with translations and Sister Brünger with finances, Elfriede Marach was to assist Sister Heimburg with the auxiliaries, and Ilse Krämer was to do the cooking and housekeeping. Wood offered each a monthly salary of 50–75 Reichsmark in order to give them official status as employees and to prevent the government from compelling them to take other employment. Within days, each of the women responded affirmatively to the assignment and expressed the hope that the mission president would return soon. [23]

To the disappointment of all, Joseph Fielding Smith eventually announced that the missionaries would not be returning to Germany. Those whose terms of service were nearly completed were to be released, and the rest were to be assigned to missions in North America. Initially, M. Douglas Wood was to go to Sweden to assume the leadership of the mission there.

From Basel, President McKay sent a letter dated September 8, 1939, to be read throughout the West German Mission. The end of that letter reads:

All who will receive this letter, must not only take care of their own responsibilities but also of those officers, teachers and members who have been called to serve their country.

We pray sincerely to our Heavenly Father, that He might protect and bless those that have been called to arms and that He might strengthen those who have remained at home for the additional responsibilities that rest upon your shoulders.

Don’t neglect your personal and family prayers. Live a pure virtuous life, keep the Word of Wisdom, pay your tithing, fast offering and other contributions, visit and participate in all the meetings, keep free from finding fault and bearing false witness, sustain those that have been called to preside and to direct and it is our promise, that the Lord will guide and lead you in all things and that you, even in the midst of afflictions and difficulties, will find joy and satisfaction.

Be always mindful that we are engaged in the work of the Lord and that Jesus is the Christ; He is our head, we are members of His Church and His truth [is] the plan of salvation. His gospel, as it has been revealed to the Prophet Joseph Smith, will be victorious. This is my testimony for you, my beloved brethren, sisters and friends. We love you and leave our blessings with you.

Your Brother

Thomas E. McKay, Mission President [24]

President Wood and his wife then wrote to the Frankfurt office staff to express their sorrow at not being allowed to return. A few days later, they traveled to Stockholm, Sweden, to direct the work of the mission there. In October, they were denied visas to stay and joined the missionaries returning to the United States. Wood’s final letter to the Saints in Frankfurt included this message:

Dear Brethren,

During my absence I have called Brother Friedrich L. Biehl (Riehlstrasse 15 in Essen-West) to be the temporary mission supervisor of the West German Mission. I ask that you all support Brother Biehl in his work with all of your energies.

I hope that you will continue to conduct the business of your branches as you have previously done. The work in the branches should not come to a standstill. Please do not forget that the work of the Lord can only go forward if you cooperate well with each other. You bear the responsibility, so please take this seriously. I trust that you will do your very best. Lead the members by your good example and fulfill your duties faithfully and conscientiously. May the spirit of brotherly love and joyful cooperation be felt everywhere.

We all pray that everything will turn out well. I would be very grateful to you if I could hear from you very soon. May our Heavenly Father bless you in your work. May he bless and protect your dear German homeland.

I send you my most heartfelt greetings and remain with best regards,

M. Douglas Wood

Mission President [25]

A veteran of the Swiss-German Mission (1934–1937), Friedrich “Fritz” Biehl (born 1913) was only twenty-six years of age and an elder when he became the new Missionsleiter (supervisor, not president) of the West German Mission. He spoke fluent English and had an engaging personality. A member of a stalwart Latter-day Saint family, he was dedicated to the work of the Church. His younger sister, Margaretha, described him as “caring, studious, and quiet, but also athletic.” [26]

He lived and worked in Essen, about two hundred miles northwest of Frankfurt. Employed in a dental clinic in his home town, he took the train to Frankfurt each Friday after work and spent the weekend there. He attended church on Sunday and then took the train back to Essen late Sunday evening. According to his sister, it was an exhausting schedule, and within a few months Biehl requested that his employer release him so that he could move to Frankfurt to dedicate himself full time to the work of the Church. His employer kindly granted the request but reminded the young man that if he left Essen he would be considered unemployed and as such would probably be drafted by the army very soon. Biehl stuck to his decision.

American missionary Erma Rosenhan (born 1915) spent some time in the Biehl home in Essen and made the following comments in her diary: “Sunday April 30, 1939: After church to Biehls for supper. Talked with Bro. Fritz Biehl. He is very brilliant. Tuesday May 9 1939: Bro. Biehl told me a lot of political jokes. Sister Rohmann complained about that.” [27]

Fig. 5. Mission supervisor Frierich Biehl of Essen (M. Biehl Haurand)

Fig. 5. Mission supervisor Frierich Biehl of Essen (M. Biehl Haurand)

Biehl’s tenure was short but productive. He wrote the following in his brief autobiography:

With the beginning of World War II, 1 September 1939, I became the Mission Leader of the West German Mission, with headquarters in Frankfurt/

Main. Every Saturday I would [travel] to Frankfurt to take care of any business that needed to be done. Several different Sundays, I visited Fall Conferences in Bielefeld, Hamburg, Hanover, Erfurt, Stuttgart, and Nürnberg. I was drafted into the army on 14 December 1939 so I could no longer function as the mission leader. [28]

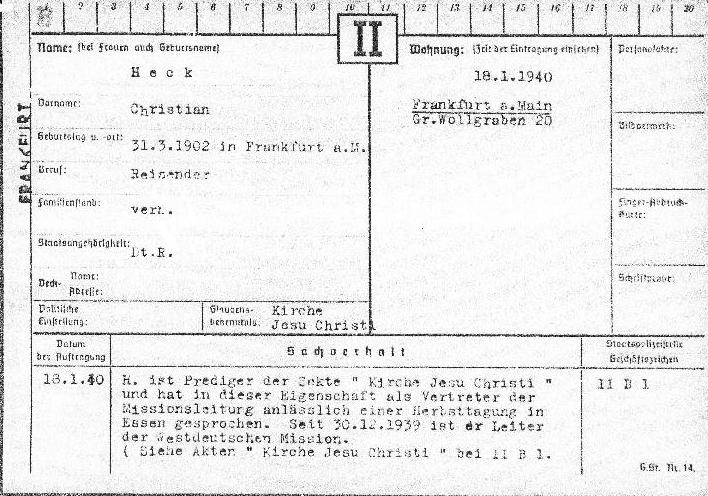

As his employer in Essen had predicted, Friedrich Biehl was classified as unemployed by the city government in Frankfurt, and a draft notice from the Wehrmacht arrived in December. With this development, President McKay issued a call to Christian Heck of the Frankfurt Branch to assume leadership of the mission. Brother Heck had served as the editor of the Church’s German-language publication, Der Stern, and was well versed in the gospel. At the time of his call, he was an unemployed salesman, but he soon found work again. His occupation required frequent travel, which allowed him to visit many of the branches in the mission for the next three and one-half years. Brother Heck selected Anton Huck (Frankfurt District president) as his first counselor and Johannes Thaller (Munich District president) as his second counselor.

Heck lost no time in assuming his duties as mission supervisor. His personal records include the following travel schedule for district conferences in the fall of 1940:

| 29–30 August | Hannover |

| 12–13 September | Bielefeld |

| 19–20 September | Essen |

| 26–27 September | Hamburg |

| 3–4 October | Flensburg |

| 10–11 October | Vienna |

| 17–18 October | Karlsruhe |

| 24–25 October | Weimar |

| 31 October–1 November | Stuttgart |

| 7–8 November | Nürnberg |

| 21–22 November | Frankfurt |

Only the Bremen and Karlsruhe Districts were not visited at the time [29]

According to Luise Heck, her husband, the mission supervisor, “was seldom at home. When my youngest child was born he was at a conference in Nürnberg. He even used vacation time for conferences. My husband recorded everything and kept all of his papers in superb order. . . . He did not have enough time to keep a diary. Every day after work he went to the mission office and worked there until late at night. Most Sundays were devoted to conferences.” [30]

All of the five women employed in the mission office at Schaumainkai 41 remained there for various lengths of time. Paying them a stipend (as well as granting them free room and board) was probably effective in allowing them to stay there as employees for some time. [31]

Hildegard Heimburg had served in the Swiss-German Mission (based in Basel, Switzerland) in the 1930s. She was a native of Gotha in eastern Germany but had moved with her family to Frankfurt am Main in 1938. Her younger brother, Karl Heimburg, recalled spending time in the mission office as a volunteer: “I was an auto mechanic apprentice and worked all day long at my trade. In the evening I went to the mission office and did all the printing downstairs in the basement.” He also became acquainted with the Wood family before they departed Germany. [32]

Ilse Brünger (born 1912) had joined the Church in 1938 and accepted a call as a missionary within a year. Under M. Douglas Wood, she became the secretary responsible for finances. She wrote the following about the working conditions during the war: “I loved my work. I had a very good relationship with all the district presidents and did most of the correspondence with them. The work was hard; it took long hours, but it was very rewarding. . . .Traveling was nearly impossible, yet we did travel to all [district] conferences.” [33] In September 1940, Ilse was drafted to work as a censor in English and French in a military office. Her kind supervisor, a captain, allowed her to continue working in the mission office.

Fig. 6. Mission supervisor Christian Heck (seated in front row left) is shown here as a member of the Frankfurt District choir in 1936. (O. Förster)

Fig. 6. Mission supervisor Christian Heck (seated in front row left) is shown here as a member of the Frankfurt District choir in 1936. (O. Förster)

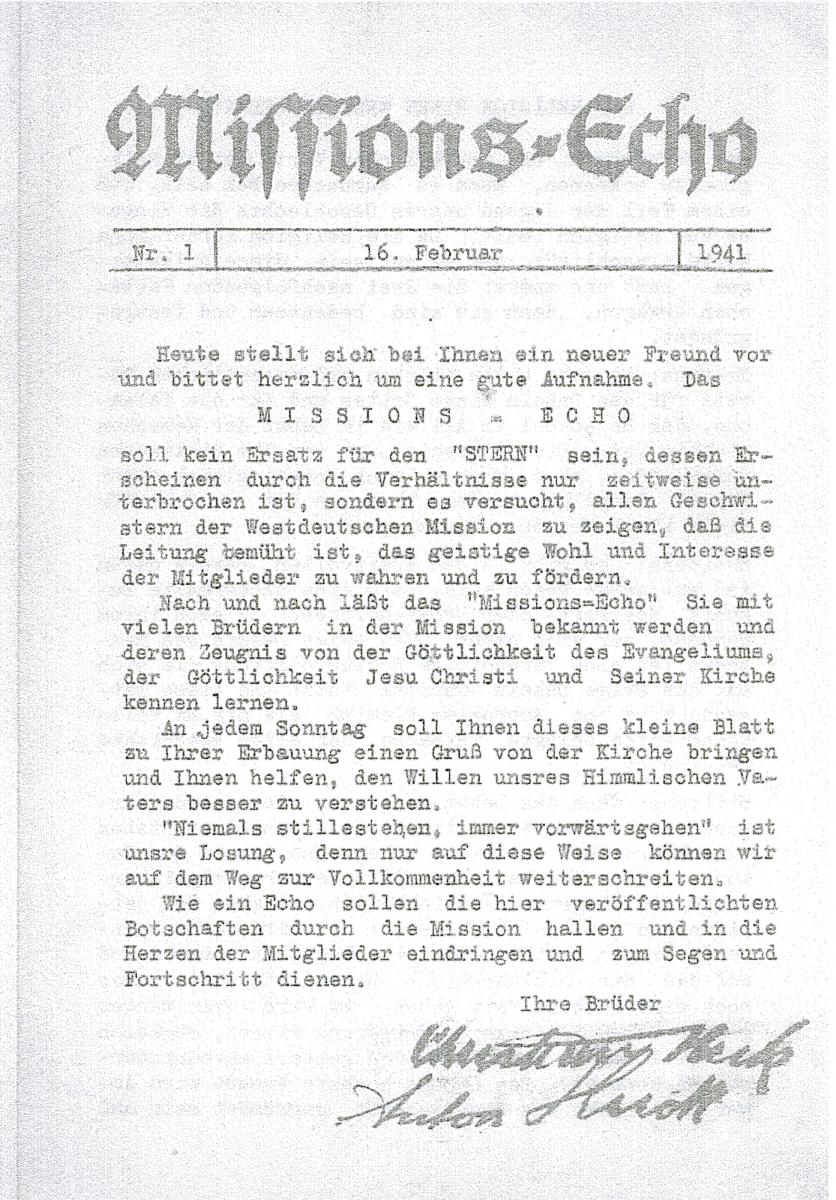

In 1941, government restrictions on paper supplies caused the discontinuation of the Church publication Der Stern. In an attempt to maintain communications with the branches, the mission office in Frankfurt published a newsletter entitled Missions-Echo from February 16, 1941, to at least April 17, 1941. [34] This four-page publication featured articles by Church leaders, essays by district presidents, and messages from mission leaders and office staff members. The inaugural issue began with this text:

Today we are introducing to you a new friend, the Mission-Echo. This is not to be a replacement for Der Stern (the publication of which is only temporarily interrupted) but is designed to remind all of the Saints in the West German Mission that the mission leaders are determined to support and promote the spiritual welfare of the members. . . . This little missive will bring you greetings from the Church every Sunday and will help you to understand better the will of our Heavenly Father. . . . The messages presented in these pages should serve as an echo throughout the mission and enter into the heart of each member and bring blessings and progress.

This message bears the signatures of Christian Heck and Anton Huck. The first issue included a talk by Asahel D. Woodruff and the schedule for district conferences to be held in the spring of 1941.

Fig. 7. The first edition of the Missions-Echo appeared on February 16, 1941.

Fig. 7. The first edition of the Missions-Echo appeared on February 16, 1941.

That Christian Heck also visited small branches is confirmed by the minutes of meetings held in the tiny branch of Bühl, in the southwest corner of the mission. On July 13, 1941, the Saints there must have been a bit surprised to see not only Heck but also the two counselors of the faraway East German Mission, Richard Ranglack and Paul Langheinrich from Berlin. All three spoke during the Sunday School service. [35] Heck visited the same branch three more times by May 16, 1943, and on one occasion, he sang a solo of the beloved German hymn Noch Nicht Erfüllt.

Heck was a man of many talents. For a short time he had served as the editor of Der Stern. His daughter Hannelore (born 1939) offered this description: “He was a traveling salesman—an agent. During the depression years, that was [the only kind of work] that was available but it was not actually his occupation. He loved learning and even taught himself English out of books. He also taught himself Italian and French, although I don’t know how fluent he was in those two languages.” [36]

Annaliese Heck, another daughter, recounted an experience from the year 1938 that embodied her father’s dedication to God:

My parents were very spiritual. They had two children, my sister Hannelore and me, and those were difficult times. My father was a factory representative and wasn’t doing very well financially. My parents had said that if my father got a good position with a steady income and he didn’t have to travel as much and have so many other expenses, then they would have another child. That was in Easter 1938. And I said, “How can you do that? There will be a war within a year.” And my mother said to my father, “Maybe we should rethink that decision to have another child. When we made that covenant with our Heavenly Father, we didn’t know there would be a war.” Then my father said, “A covenant is a covenant. War or not,” and she said that she was ashamed that she had even thought of [changing their plan]. And that is precisely what they did. And then our youngest sister, Krista, was born in 1940; it was very remarkable. [37]

For the leaders of the West German Mission, the war years were not a time to rest. The mission history shows the constant influx of reports from branch and district presidents (mostly from the districts of Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg, and Bremen). Whereas most of those reports dealt with Sunday School and sacrament meetings, Relief Society programs and district conferences, there were also numerous reports of leaders who had been drafted and therefore needed to be released and replaced. The very first report received during the war was dated Friday, September 1, 1939, and conveyed disappointing news from the distant city of Bremen:

The meeting hall of the Bremen Branch was confiscated by the German Army. All requests, that at least one room [be] made available to the branch, are mockingly denied. “You are only trying to blunt the intellects of the people,” President Willy Deters is told. Meetings in Bremen are held again in the Guttempler Logenhaus at Vegesackerstrasse. However, it is only possible to hold one Sacrament meeting on Sundays. At this time Brother Albert Adler, Brother Erwin Gulla and Brother Johann Woeltjen are called into the military service. The Bremen Branch is now under the direction of district President Willy Deters. [38]

Other reports contained the following information:

March 16–17, 1940: The Hamburg District held its spring conference, during which five persons were baptized. [39]

October 5–6, 1941: The fall conference of the Bremen District was held. Elders Heck and Huck were among the 153 persons in attendance. “The spirit of God was present in the meetings in rich abundance.” [40]

March 22, 1942: During the centennial celebration of the Relief Society, a play was performed in the St. Georg Branch (Hamburg District) meeting hall. The play was written by Inge Baum of the Kassel Branch (who also attended). Sisters from all over the district participated. Five hundred persons were served lunch from the branch kitchen. [41]

Fig. 8. Christian Heck (seated in the middle of the front row) represented the West German Mission at a conference of the East German Mission in Berlin in 1942. To his left is East German Mission supervisor Herbert Klopfer.

Fig. 8. Christian Heck (seated in the middle of the front row) represented the West German Mission at a conference of the East German Mission in Berlin in 1942. To his left is East German Mission supervisor Herbert Klopfer.

A curious document is found among the papers of Erwin Ruf, who was president of the Stuttgart District. Entitled “Decision,” the one-page statement is dated January 31, 1942, and appears to have been issued to dispel any doubt regarding Christian Heck’s authority to function as the mission supervisor. [42] The translation of the text reads as follows:

A council convened today consisting of the following brethren: Johann Thaller, president of the Munich District; Hermann Walther Pohlsander of Celle [representing the Hannover District], and Erwin Ruf, president of the Stuttgart District. The council arrived at the following decision:

We hereby recognize Elder Christian Heck of Frankfurt/

Main as the current supervisor of the West German Mission until such time as he is released from this office by Church authorities. It has also been decided that the mission leadership be expanded to include a second counselor. Brother Johann Thaller was nominated.

[signed] Joh. Thaller

H. W. Pohlsander

Erwin Ruf

The following brethren accept the above decision:

[signed] Anton Huck Christian Heck

As a witness, representing the East German Mission:

[signed] Paul Langheinrich

Because there is no evidence that members of the Church questioned Heck’s assignment (who by then had served in that calling for nearly two years), the document was likely produced in order to confirm the position of Heck as the spokesman of the Church in the eyes of the government. The statement may also have proved to the government the claim made by Heck that he needed to travel by rail to points all over western Germany to administer the affairs of the Church.

Fig. 9. Mission financial secretary Ilse Brünger with her groom Otto Förster on December 20, 1941. (O. Förster)

Fig. 9. Mission financial secretary Ilse Brünger with her groom Otto Förster on December 20, 1941. (O. Förster)

In the mission office, the Saints were not always unified in their political opinions. According to Ilse Brünger Förster (who married Otto Förster in December 1941), “One evening there was a big misunderstanding in the mission office due to political differences, and I saw things which were too hard for a young convert to understand. I was a young girl, still full of optimism and the hope of a bright future. I was so hurt and felt so sorry for one brother who did not agree politically with another brother and nearly had a heart attack over this conflict.” [43]

A visit from the Gestapo frightened Ilse in June 1942. Returning with Otto from a visit in Michelstadt, she found that the office had been inspected and sealed by the secret police. The next morning, she was taken from the office to Gestapo headquarters on Lindenstrasse. She recalled the experience in these words:

At the Gestapo Headquarters I was questioned for six hours or more and then was asked to come back the next morning with a report of all the tithing money that had been collected since 1936 and all the membership records. I told the three people who questioned me that it was impossible to obtain all that information in such a short period of time, but they requested the reports the next morning without any arguments on my part. . . . [Otto and I] sat together all through the night and worked; just before 7 o’clock the next morning the papers were ready. It is a miracle to me that we got it done. . . . I know with all my heart that God gave us this miracle to show us that he was on our side. [44]

Although none of the wartime leaders of the mission told of restrictions placed on the Church by the Gestapo, attempts were made early in the war or perhaps even prior to the war to avoid words or phrases that appeared to be foreign (non-German). As in the East German Mission, the Saints did not sing hymns featuring words such as “Israel” and “Zion”—terms directly linked with the Jewish culture so despised by the Nazis. In the West German Mission, additional linguistic alterations were introduced. For example, the names of groups and meetings were modified. [45] The term for Relief Society was changed from Frauenhilfsvereinigung to Schwesternklasse (sisters’ class). The sacrament meeting was changed from Abendmahlsversammlung to Predigversammlung (sermon meeting). The term Gemeinde (branch) was supplanted in public literature by the word Verein (society). The use of the word Kirche (church) was even suppressed in some cases in favor of the word Verein (society). [46] The foreign word Distrikt was also replaced by the German termBezirk.

Christian Heck was a loyal servant of God—a man determined to preserve the Church in Germany when no help from the United States was to be had. For example, at the conclusion of a district presidents conference held in Frankfurt on February 21, 1943, he offered this farewell:

I wish you well on your trip home, that all of you may return to your districts with a strengthened spirit and that you will take up your work again according to the suggestions made in this conference with renewed courage and that you will use these suggestions and instructions in the future. This is not our work but the work of the Lord. This is not a matter for individuals, and not a matter for many people, but the work of God, given to man for the last time in this dispensation. [47]

On May 17, 1943, Christian Heck responded to a draft notice of the German army and was sent to the Eastern Front. His wife, Luise, recalled:

Despite all of the opposition he faced, he did his duty until the very end. I recall very clearly—and will never forget for as long as I live—that on that last Sunday (which happened to be our wedding anniversary and Mother’s Day) he spent the last hours doing the work of the Lord. He had had to make a last-minute trip to Bühl, Baden in order to solve some problems there. [48]

In Christian Heck’s absence, the district leaders of the West German Mission met to decide whom to designate as the supervisor of the mission. Their choice was the first counselor, Anton Huck. Huck (born 1872) was too old to be drafted and would thus be likely to be able to remain in this calling for some time. He had already traveled extensively with Heck, was well known throughout the mission, and had even attended at least one conference of the East German Mission in Berlin. While he worked to maintain order at Schaumainkai 41, he was assisted all over the mission by dedicated district presidents who likewise were constantly on the road to visit branches of the Saints in their respective areas. From the available literature, it is clear that Johann Thaller, president of the Munich District, and Kurt Schneider, president of the Strasbourg District, served as counselors to Huck. Each enjoyed the use of a company automobile for personal activities, which allowed them to travel much more frequently and greater distances than other district presidents.

Fig. 10. The official Gestapo record of mission supervisor Christian Heck. He is classified as a traveling salesman. The note at bottom reads, “Heck is a preacher of the sect ‘Church of Jesus Christ’ and recently spoke at a fall conference in Essen as a representative of the mission leadership. He has been the leader of the West German Mission since December 30, 1939.” (Frankfurt City Archive) [49]

Fig. 10. The official Gestapo record of mission supervisor Christian Heck. He is classified as a traveling salesman. The note at bottom reads, “Heck is a preacher of the sect ‘Church of Jesus Christ’ and recently spoke at a fall conference in Essen as a representative of the mission leadership. He has been the leader of the West German Mission since December 30, 1939.” (Frankfurt City Archive) [49]

Ilse Brünger Förster received a telephone call in July 1943 with the news that many Saints in Hamburg had been bombed out and several killed. She called the Relief Society president of the Frankfurt Branch,

and within a few hours we were in touch with all the members of the Frankfurt Branch and asked them to help the members in the Hamburg area. I have never seen busier people. Everyone helped with clothing, bedding, and other items. In a very short time relief was on its way to all the members in Hamburg. At that moment I felt that we were all a big family helping and loving one another. I must say that all the things we collected were good things, not just worn out things, but the very best things and that made me feel so wonderful. [50]

In 1943, Anton Huck was for a short time a person of interest to the state police. One morning at 7:30, Gestapo agents knocked at his door and asked to see his historical records. Then they instructed him to dress and accompany them to the mission office (they also took several Church books and pamphlets from his home). Upon arriving at the mission office, they found six more agents going through the Church records, “especially our lesson material and our financial records.” Huck was required to respond to this question: “Mr. Huck, under your leadership this mission has had a great financial increase. What is the reason for this?” His response: “Before the war we had many unemployed men and women and today they are all working and as you know, we have the law of tithing in our church. Before the war we had to spend money for missionary expenses, to build up branches, to buy furniture, organs and pianos. Today we only pay our current expenses. These are the reasons for an increase in our funds.” [51] The agent was apparently satisfied with the explanation. At the end of the day, the Gestapo confiscated several books. Two days later, Huck was asked to report at Gestapo headquarters where he underwent a lengthy interview. After the interview was properly recorded, he was asked to sign the transcript. When the entire investigation was completed, Huck was asked why he had not joined the National Socialist (Nazi) Party. He explained that he was responsible for seventy-three branches of the Church and had no time for other activities. This reply apparently did not engender the ire of the officials. [52] Perhaps they were not worried about a seventy-one-year-old man who claimed to be a church administrator and worked in a huge building that must have been mostly empty at the time. [53]

Anton Huck was a popular leader, in part because he traveled extensively both within the West German Mission and to events in the East German Mission. Maria Schlimm (born 1923) of the Frankfurt Branch had this recollection of Elder Huck: “We called him ‘Papa Huck’ and we liked him very much. He was already retired but had worked as a streetcar driver before that. Because he was not working anymore, they could not get him to join the [Nazi] party.” [54] Several eyewitnesses had been told that Anton Huck was denied promotions by his employer because of his membership in the Church.

Fig. 11. Anton Huck served as the supervisor of the West German Mission for the last two years of the war. (E. Wagner Huck)

Fig. 11. Anton Huck served as the supervisor of the West German Mission for the last two years of the war. (E. Wagner Huck)

On October 4, 1943, a major air raid destroyed large parts of the city of Frankfurt. Anton Huck’s family lost their home in the attack and they moved into rooms in the mission home with what little of their belongings they had been able to rescue from the flames. While the Hucks were sad at having lost their home, Huck now had much more time to devote to the work of the West German Mission. In a report written shortly after the war, he recalled that air raids all over the mission territory had made it impossible to maintain communications, to receive donations, and to record and deposit money safely. On several occasions, the mission received reports that funds had been transferred, but those funds never arrived.

As the war progressed, reports regarding branches in the Alsace-Lorraine province of France (occupied by German troops since 1940) arrived in the mission office. Mention was made of Latter-day Saints in the capital city of Strasbourg on the Rhine River and in Mühlhausen to the south. The general minutes of the Bühl Branch (Karlsruhe District) report a number of activities undertaken by Bühl members and their counterparts across the Rhine in Strasbourg. [55] The first such report was dated March 3, 1942: Anton Huck from the mission office conducted a funeral for a sister Maria Kuester in Strasbourg, and two members of the Bühl Branch attended the service. On April 26, 1943, eleven Bühl Saints and eight from the Strasbourg Branch had a party at the home of the Paul Kaiser family in Grüneberg, near Strasbourg.

In August 1943, a new meeting place for the Strasbourg Branch was dedicated under the leadership of Anton Huck. Eleven members of the Bühl Branch were in attendance, as were forty more members from the branches of Frankfurt, Saarbrücken, Karlsruhe, Mannheim, Pforzheim, and Freiburg. The same Paul Kaiser was the branch president in Strasbourg. On December 12, 1943, Anton Huck presided over a meeting in which a new Strasbourg District was established that included the neighboring branch in Bühl. [56] The only Alsace-Lorraine branches named in the record were those in Strasbourg and Mühlhausen. For the next year, several more activities involving Saints in France and Bühl were reported in the Bühl Branch minutes.

During the last two years of the war, air-raid alarms and attacks made it increasingly challenging to carry on the work of the West German Mission office. Equipment was moved to the rooms on the lower floors. Huck was constantly on the road, presiding over church services where no priesthood holders were present and conducting weddings and funerals in various branches. For example, after he appointed a young woman to see that meetings were held in the Bad Homburg Branch (ten miles northwest of Frankfurt), he attended the Sunday meetings on a regular basis in order to assist with the administration of the sacrament. [57] In accordance with the instructions given to the leaders of the West German Mission in 1940, Huck recalled that he “kept constantly in touch with the leaders of the East German Mission. We exchanged opinions and also things that we were in need of, as much as possible.” [58]

Christian Heck had experienced the war in Russia but became quite ill and was sent home in early 1945. It may have been unfortunate that he recuperated there, because as the war drew to a close, he was sent out to fight against the invading American army in southern Germany. It was there that he was shot in the stomach in early April 1945. According to his daughter, Annaliese (born 1925), the operation to remove the bullet was successful, but his heart did not tolerate the stress, and he died in a Catholic hospital in Bad Imnau, Hohenzollern. “We received a wonderful letter from a Catholic nun informing us of my father’s death,” she recalled. [59] Just forty-three years old, Christian Heck became the third former or current German mission supervisor to die in World War II. [60] He was buried in Bad Imnau, 150 miles south of Frankfurt. In May 1945, a fellow soldier visited Sister Heck, informed her of the fate of her husband, and presented her with his personal effects.

A few years after the war, Luise Heck had this to say about her husband: “I comfort myself with the idea that God could have protected my husband if He had wanted to. As if by a miracle, He brought him safely back from Russia. Would it then not have been possible to protect him in his homeland?” [61]

Of the many meetings held in the mission home in the last year of the war, the sacrament meeting on February 7, 1945, may have been the most memorable, at least in the mind of Carola Walker (born 1922). She recalled that the sirens sounded just as the sacrament was being passed, and they all went downstairs without delay.

The airplanes started to [drop their bombs] and it did not take long before we realized that we would be hit. The basement was absolutely not a safe place. The windows were above ground and offered only minimal protection together with the sand bags. . . . We knelt down to pray and I was kneeling in front of a wooden box filled with potatoes. . . . We heard the whistling of the falling bombs. I did not breathe. The detonation of the bombs made the walls sway back and forth—like a heavy earthquake. The ground was shaking and we wondered if the walls would straighten out again or if the house would collapse. We would be buried alive. I could not pray. I could not form the words to ask Heavenly Father to protect us. Every fiber of my body was crying out to Him for help. A sister kneeling beside me was praying aloud despite the whistling of the bombs. She was pleading with our Heavenly Father to protect us. I don’t remember what she said but it gave me a feeling of comfort. It finally got quiet and we went outside and see how serious the damage was. Nothing had happened to the mission home. Beside the building there was a hole, maybe a yard in diameter. A bomb had fallen there and disappeared in the ground but not exploded. If it had exploded, we would have been buried under five stories of stone. The prayer did help. [62]

By April 1945, the mission office on the south bank of the Main River was home to several dozen Saints from local branches who had lost their homes in air raids. Because the meeting rooms of the Frankfurt Branch at Neue Mainzerstrasse 8–10 had also been lost, Sunday meetings were being held in the mission home as well. [63] It must have been a serious challenge for the adults in the building to locate enough food in a city that had been destroyed to an appalling degree.

Fig. 12. Otto Förster lived in the mission home at the end of the war. He drew this plan from memory years later. The president’s office was on the north side of the building facing the river. (O. Förster)

Fig. 12. Otto Förster lived in the mission home at the end of the war. He drew this plan from memory years later. The president’s office was on the north side of the building facing the river. (O. Förster)

The war came to an end at Schaumainkai 41 on March 26, 1945. A resident in the building at the time with his family, Anton Huck was confronted by American soldiers, who informed him at 6:45 p.m. that all occupants of the building had to be out by 7:00 p.m.; the soldiers (“about fifty of them, many of those were colored”) guarding the Main River bridge just across the street were to be quartered in the building. Huck and the other LDS refugees had a very difficult time finding new rooms to inhabit. The few structures in the neighborhood that were intact were filled with people of similar circumstances. According to Huck, the invaders stayed in the building for more than a month. “In our absence much damage was done. All the suitcases, packages, and everything that was wrapped was torn open, ransacked and completely or partly destroyed. . . . It was hard to describe how bad [the damage] was.” Despite the collapse of the Third Reich, the presence of the victorious Allies, the loss of Church property, and the scattering of the Saints, Huck wrote in 1946 that “the condition of the mission was spiritually and financially very good.” [64]

Ilse Brünger Förster commented on the aftermath of the American occupation of the building:

We came back only to find that all the beautiful things like china, silverware, crystal, which I had safely brought through the war, were gone. Nothing was left. The furniture that did not get damaged during the bombings was either stolen or completely destroyed maliciously by the soldiers. I cried many tears, but that did not bring back my belongings. [65]

J. Richard Barnes, the American missionary who served as executive secretary to M. Douglas Wood in August 1939, returned to Germany in 1945 as a major in the United States Army. When he found himself in the vicinity of Frankfurt, he immediately sought an opportunity to visit the mission home and determine the status of the Church. A letter he wrote to Thomas E. McKay in Salt Lake City was eventually published in the Deseret News under the title “War Leaves Stamp on German Mission.” [66] He described his first impression in these words: “To my surprise I found that the mission home and office is still standing, and only slightly damaged. A few broken windows here and there. A bomb had hit in the little ‘Hof’ formed by the two parts of the building, but had only cracked the wall slightly and left a large crater.”

Major Barnes expressed optimism for the future of the Church in Germany and suggested that efforts begin as soon as possible to locate the Saints who were scattered throughout the country. All fourteen districts were still functioning in 1945 under the leadership of Anton Huck, although a few branches had become defunct. The French portion of the fledgling Strasbourg District was returned to the French Mission upon the departure of German troops.

The building at Schaumainkai 41 in Frankfurt continued to serve the West German Mission after the war. The building had survived virtually intact and was used by the mission office until 1952, when new quarters were found across the river on Bettina-Strasse. Today the former mission home serves as the Deutsches Filmmuseum (German Cinema Museum). Barnes visited the museum in the 1970s and observed that whereas the largest rooms on the main floor had been redesigned and an entrance constructed in the north facade, several offices still looked as they had in 1939. [67] The director of the museum informed the author in 2009 that the entire interior of the building had been renovated in the early 1980s and that none of the rooms look as they did during the war.

Fig. 13. The former West German Mission office at Schaumainkai 41 is now the home of the German Cinema Museum (R. Minert, 2008)

Fig. 13. The former West German Mission office at Schaumainkai 41 is now the home of the German Cinema Museum (R. Minert, 2008)

Notes

[1] West German Mission History quarterly report, 1938, no. 1, CHL LR 10045 2. Philemon Kelly was succeeded in Berlin by Alfred C. Rees.

[2] West German Mission History quarterly report, 1938, no. 6. It was not until August 24, 1938, that Philemon M. Kelly offered a prayer of dedication for the Frankfurt mission office. West German Mission History quarterly report 1938, no. 30.

[3] For details on the Church in eastern Germany, see In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009).

[4] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[5] West German Mission quarterly report, 1938, no. 15. Evelyn Wood became famous years later in the United States for her speed-reading course known as “Reading Dynamics.”

[6] The 1938 year-end report showed the following: “Members 5190 plus 134 baptisms = 5332; 13 districts; 68 organized branches (48 presided over by local leaders); 89 missionaries; 47 children of record baptized, 87 converts baptized; 1090 full tithe payers, 522 part, 1347 non-tithe payers; 1219 members paid fast offerings (per capita mission average $0.60).” West German Mission quarterly report 1938, no. 46.

[7] West German Mission quarterly report, 1938, no. 34.

[8] CHL LR 10045 2 QR 1938:38

[9] The diaries of several Americans who served in the West German Mission in the late 1930s reflect a fascination with the Third Reich. Many felt that Hitler did indeed offer Germans a promising and prosperous future.

[10] West German Mission quarterly report 1938 no. 41.

[11] West German Mission quarterly report 1939 nos. 20–22.

[12] It is interesting to note that the flag in this 1939 photograph had only forty-five stars rather than forty-eight. This was the flag flown in the United States from 1896 to 1908, following the admission of Utah as a state. The outdated flag was probably procured by the city around the turn of the century and kept for subsequent events.

[13] George Blake, papers, CHL MS 17781.

[14] George Blake, papers. In March 1945, the following persons and families also lived in the building: Dr. Richter (second floor), Dominick (third floor), Hecht (fourth floor), caretaker Mr. Armbruester (fifth floor). Each tenant also had a storage room on the fifth floor. Several of those rooms were used as bedrooms for missionaries (Ilse Foerster Young).

[15] George Blake, papers.

[16] M. Douglas Wood, papers, CHL.

[17] Ibid.

[18] George Blake, interview by the author, Provo, Utah, April 1, 2009.

[19] The adventures of many of those missionaries are recounted in Terry Bohle Montague, Mine Angels Round About, 2nd ed. (Orem, UT: Granite, 2000). The missionaries were in a hurry to leave at the time but were not in any danger. American citizens were not required to leave the country in August 1939, and indeed several hundred Americans stayed safely in Germany until the two nations exchanged declarations of war in December 1941. Several dozen American citizens were still in Germany in 1942 and were interned in a luxury hotel in Bad Homburg until the war ended. Whereas it is possible that some Germans feared invasion from France or even air raids, none of the American missionaries are quoted as having shared that fear when they departed Germany.

[20] M. Douglas Wood, papers.

[21] M. Douglas Wood to Friedrich Biehl, September 8, 1939.

[22] The sum of 21,000 Reichsmark was held in accounts in several banks at the time. Wood instructed Sister Brünger to withdraw the money and hide it if there was any chance that it would be confiscated by the government. Wood believed that tithing payments would drop substantially as members lost their jobs, but he wanted the mission office to remain open as long as possible.

[23] M. Douglas Wood, papers.

[24] Thomas E. McKay, papers, CHL B 1381:3.

[25] M. Douglas Wood, papers.

[26] Margaretha Biehl Haurand, interview by the author, Bountiful, Utah, February 16, 2007.

[27] Erma Rosehan, papers, CHL MS 16190.

[28] Friedrich Ludwig Biehl, autobiography (unpublished), 194; private collection.

[29] Christian Heck, papers, 12, CHL MS 651.

[30] Luise Heck to Justus Ernst, October 20, 1960; Christian Heck, papers, CHL MS 651.

[31] Anton Huck recalled that each of the women was released at the proper time, but it is not known precisely when they came to the mission office. If all of them were indeed released on schedule, none would have been at Schaumainkai by 1942. The Barnes letter of 1945 makes it clear that this did not happen.

[32] Karl Heimburg, interview by the author, Sacramento, California, October 24, 2006.

[33] Ilse Wilhelmine Friedrike Brünger Förster, autobiography (unpublished, about 1981); private collection.

[34] Copies of eleven issues of the Missions-Echo were provided to the author by Gustav Karl Hirschmann.

[35] Bühl Branch general minutes, 105, CHL LR 1180 11.

[36] Hannelore Heck Showalter, telephone interview with the author, March 9, 2009.

[37] Annaliese Heck Heimburg, interview by the author, Sacramento, California, October 24, 2006.

[38] Thomas E. McKay correspondence 1939–1946, CHL CR 271 40.

[39] West German Mission History, March 16–17, 1940, CHL LR 10045 2 A 2998:217.

[40] Thomas E. McKay correspondence.

[41] West German Mission History, March 22, 1942, CHL LR 10045 2 A 4560:71–72.

[42] Stuttgart Germany District general minutes, CHL LR 16982 11.

[43] Ilse Brünger Förster, autobiography. Most eyewitnesses would assume that the two were Christian Heck and Anton Huck.

[44] Ilse Brünger Förster, autobiography. Ilse claimed that Christian Heck did not assist her in this crisis. “He said that I was the secretary and responsible for everything. That was one of the hardest things for me as a young convert to understand.”

[45] To date, no literature has been found to explain the reasons for the changes in these terms, but the substitute names are found in the minutes of branches all over the mission.

[46] The two dominant churches in Germany at the time (the Roman Catholic and Lutheran Churches) were still slow to grant the Latter-day Saints the status of Church members. See the Stuttgart Branch chapter for an example of interaction between the Lutheran Church and the LDS Church.

[47] Christian Heck, papers.

[48] Luise Heck to Justus Ernst, October 20, 1960, Christian Heck papers.

[49] Ilse Brünger Förster, autobiography.

[50] The author expresses his gratitude to Lutz Becht for locating this document in the archive and providing a digital image.

[51] Anton Huck, statement, March 17, 1946, CHL LR 10045, vol. 1.

[52] The question of Anton Huck’s Nazi Party membership is one that has been debated for years. Several eyewitnesses, who requested anonymity when interviewed by the author, insisted that Huck was a party member and that he wore the small, round, party swastika lapel pin on his suit coat. One eyewitness clearly recalled hearing Huck pray for Adolf Hitler in a Church meeting (and being reprimanded publicly by the branch president for doing so). Several persons have stated that it was Anton Huck who required the president of the St. Georg Branch in Hamburg to display a sign with the wording “Juden Verboten” (Jews forbidden) by the entrance to the branch meeting hall (see Hamburg-St. Georg Branch chapter). Just after the war, it was suggested that Huck had visited branches in Alsace-Lorraine (the Strasbourg District included occupied French territory bordering the Rhine River) and recommended that the Saints there (most of whom were French citizens) should support Hitler in his righteous campaigns.

[53] Erich Bernhardt (born 1920) was one of many eyewitnesses who were convinced that Elder Huck was an enthusiastic party member. He made the following statement: “The fact is, that I don’t know why Br. Huck became a mission president, knowing that he approved the Nazis one hundred percent and there are a whole number of leaders who also were involved. Brother Biehl was not one of those. I don’t want to mention any names, but Huck was very well known as a Nazi.” Erich Bernhardt, oral history interview, 10, CHL MS 8090.

[54] Maria Schlimm Schmid, interview by the author in German, Frankfurt, August 18, 2008; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[55] Bühl Branch general minutes, 144, CHL LR 1180 11.

[56] Bühl Branch general minutes, 150.

[57] See the Bad Homburg Branch section.

[58] Anton Huck, statement, March 17, 1946.

[59] Annaliese Heck Heimburg, interview.

[60] The first was Friedrich Biehl and the second was Herbert Klopfer of the East German Mission, who died in a Soviet POW camp on March 19, 1945.

[61] Christian Heck, papers, 75.

[62] Carola Walker Schindler, autobiography (unpublished), private collection. Used with permission of Karl Schindler. This event was also recorded in the general minutes of the Frankfurt Branch on February 7, 1945, and mentioned in a report written by J. Richard Barnes a few months later.

[63] Maria Schlimm Schmidt, interview by the author in German, Frankfurt am Main, August 18, 2008.

[64] Anton Huck, statement, March 17, 1946.

[65] Ilse Brünger Förster, autobiography.

[66] Deseret News, July 2, 1945.

[67] John Richard Barnes, recollections, 1985; courtesy Terry Bohle Montague.