The Double Nature of God’s Saving Work: The Plan of Salvation and Salvation History

Heather Hardy

Heather Hardy, “The Double Nature of God’s Saving Work: The Plan of Salvation and Salvation History,” in The Things Which My Father Saw: Approaches to Lehi’s Dream and Nephi’s Vision (2011 Sperry Symposium), ed. Daniel L. Belnap, Gaye Strathearn, and Stanley A. Johnson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 15–36.

Heather Hardy earned an MBA from Brigham Young University and worked for several years in university administration at Yale and BYU before leaving the workforce to raise children and pursue a life of learning.

While tarrying in the valley of Lemuel, Lehi instructed his family members on their individual spiritual well-being by relating his dream of a tree laden with precious fruit, as recorded in 1 Nephi 8. Two chapters later, in the same address, he prophesied additionally of the Lord’s future redemptive acts on behalf of collective Israel. Nephi received a vision of his own, reported in 1 Nephi 11–14, which integrated these two distinct aspects of salvation by elaborating on the Lord’s redemption of both individuals and entire peoples. Over the ensuing decades, Lehi, Nephi, and Nephi’s brother Jacob pondered the implications of this double nature of God’s saving work, studying scriptural precedents and receiving new revelations. Their insights—expanding on Lehi’s wilderness address—serve as both the thematic underpinning of Nephi’s small plates and the theological foundation of the Lehite understanding of salvation.

Lehi’s Wilderness Address as Differentiating Two Aspects of Salvation

Whenever considering Lehi’s dream, readers should keep in mind that 1 Nephi 8 was only the first half of the prophet’s address to his family in the valley of Lemuel. Despite the fact that Nephi concludes this chapter with the words “After he had preached unto them, . . . he did cease speaking to them” (1 Nephi 8:38), when the account resumes after a brief editorial interlude (1 Nephi 9), Lehi is still talking. As Nephi reports, “After my father had made an end of speaking the words of his dream, and also of exhorting [Laman and Lemuel] to all diligence, he spake unto them concerning the Jews” (1 Nephi 10:2). Subsequent textual evidence confirms a continuation of Lehi’s speaking. For example, when Nephi expresses his desire to see, hear, and know his father’s teachings for himself, he mentions both “the things which [Lehi] saw in a vision, and also the things which he spake by the power of the Holy Ghost” (1 Nephi 10:17). In describing his own vision, Nephi includes elements not only from Lehi’s dream but also from his prophecies. Later, when Laman and Lemuel seek clarification of difficult elements “concerning the things which [Lehi] had spoken unto them” (1 Nephi 15:2), their questions address the meaning of the allegory of the olive tree (from 1 Nephi 10) as well as of Lehi’s dream of the tree (from 1 Nephi 8; see 1 Nephi 15:7–36). It is within a single discourse, then, that Lehi teaches his children about obtaining the fruit desirable above all others (see 1 Nephi 8:2–38) and also about the coming of a Messiah, the scattering of Israel, and the ministering of the Holy Ghost to the Gentiles (see 1 Nephi 10:2–14).

The balanced structure of Lehi’s wilderness teachings similarly suggests an intended unity in his account of the dream in 1 Nephi 8 and his discussion of the destiny of the house of Israel in 1 Nephi 10. Both segments include an allegory (8:4–35; 10:12–14), prophecies (8:38; 10:3–15), and some level of interpretation (8:36; 10:4, 13, 15). Each allegory focuses on a particular fruit-bearing tree. The first, the allegory of the tree of life, [1] came to Lehi as an original revelation and reflects his concerns about the well-being of family members as they traveled in the wilderness. It depicts individuals responding to the offer of sustenance inherent in an exquisite tree whose fruit is “desirable to make one happy” (1 Nephi 8:10). The second, the allegory of the olive tree, was apparently derived from Lehi’s study of the prophet Zenos’s writings on the brass plates since both compare the house of Israel to an olive tree whose branches are broken off, dispersed, and eventually gathered together again (see 1 Nephi 5:10, 21; see also Jacob 5). Lehi’s reading of Zenos is supplemented by new revelation that seems to have been prompted by his concern for the well-being of the house of Israel in light of Jerusalem’s pending destruction (see 1 Nephi 10:2–3). Significantly, these are the only two allegories included in the Book of Mormon, and Lehi adopts each in turn as the conceptual foundation for a distinct aspect of salvation.

By his own admission, Nephi substantially abridges Lehi’s teachings in both 1 Nephi 8 and 10, explicitly to save room on the plates and avoid redundancy (8:29–30, 38; 10:8, 15). He indicates that a more comprehensive version of his father’s wilderness address is preserved “in mine other book” (1 Nephi 10:15), and he seems to presume, erroneously as it turns out, that his readers will have access to both accounts. Here, in the small plates, Nephi’s editing initially de-emphasizes the unity of Lehi’s discourse; instead of combining the two segments into a single literary unit, Nephi deliberately separates them by inserting an extended editorial comment in the middle (1 Nephi 9). [2] The disconnection invites readers to consider the thematic link between the two portions of Lehi’s teachings.

Nephi has previously articulated a strong editorial priority for his second record, the account we are reading in 1 and 2 Nephi: “And it mattereth not to me that I am particular to give a full account of all the things of my father, for they cannot be written upon these plates, for I desire the room that I may write of the things of God. For the fulness of mine intent is that I may persuade men to come unto the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, and be saved” (1 Nephi 6:3–4; emphasis added). If this focus on salvation is indeed the “fulness” of Nephi’s intent, and if the capacity of the small plates is indeed limited, we should expect that everything that Nephi includes in these writings can be readily understood as encouraging his readers to believe in God’s saving power and respond accordingly.

In Nephi’s telling here, Lehi does, in fact, open each half of his discourse with the subject of salvation. Regarding the dream, Lehi reports, “And behold, because of the thing which I have seen, I have reason to rejoice in the Lord because of Nephi and also of Sam; for I have reason to suppose that they, and many of their seed, will be saved” (1 Nephi 8:3). Later, in speaking of the future of the Jews, Lehi again begins his remarks in salvific terms, prophesying first of their eventual deliverance from Babylon, that “they should return again, yea, even be brought back out of captivity” (1 Nephi 10:3). Note here that these passages—abbreviated as they are—seem to be describing very different concepts of salvation: the first concerning the spiritual well-being of individuals; and the latter, the temporal redemption of an entire people. The contours of these distinct but complementary concepts of salvation will become clearer as we proceed through Nephi’s small plates.

Lehi introduces the plan of salvation (1 Nephi 8). At this point, we turn to Lehi’s dream in 1 Nephi 8. The elements of the allegory are familiar enough: a beautiful tree, a rod of iron, a river, mists of darkness, and a great and spacious building. An angel will reveal their meanings to Nephi in his subsequent vision (see 1 Nephi 11:21–25; 36; 12:16–18), and Nephi will emend some of his father’s details when he responds to Laman’s and Lemuel’s questions, describing an awful gulf of filthiness and a flaming fire ascending up forever (see 1 Nephi 15:26–30). Decades later, he will again return to the symbols of Lehi’s dream, finally identifying the strait and narrow path and how it is that one can “press forward” thereon (see 1 Nephi 8:20, 21, 24, 30; 2 Nephi 31:9, 18–20; 33:9).

In keeping with the salvific theme of Lehi’s brief introduction, the thing to note here about the dream is that the people clinging to the rod, or arriving at the tree, or jeering from the great and spacious building are all making personal choices and are being rewarded or punished as individuals. Although the invitation to come to the tree is offered to all, the actual partaking (or rejecting) of the fruit is performed individually. And while “great was the multitude that did enter into that strange building” (1 Nephi 8:33), the people have all self-selected; the edifice represents a collective of individuals and not a nation or people such as the Gentiles or the Babylonians.

Lehi is particularly concerned about his eldest sons’ choices and the gravity of their consequences: “But behold, Laman and Lemuel, I fear exceedingly because of you,” he tells them twice, “lest [you] should be cast off from the presence of the Lord” (1 Nephi 8:4, 36). This last comment is the only part of Lehi’s interpretation of the allegory that Nephi provides us, and it suggests two things. First, the offer of a blessing (the fruit of the tree) is an oppositional one that ultimately separates those who choose to accept it from those who do not. Once the offer is extended, there is no neutral response; it culminates in either salvation or judgment. Second, although the allegory’s focus is on nourishment, albeit of a remarkable kind, the reality it addresses has a spiritual significance far beyond the typical dailiness of such concerns. While Lehi acknowledges the import and urgency of the risk of being cast off from the Lord’s presence, it is Nephi who will later make explicit that this dissociation will last “forever and ever,” having “no end” (1 Nephi 15:30).

From the allegory, we can outline the concept of salvation that Lehi is presenting here: It is available to individuals as a matter of personal decision and action. It is something that must be pursued and persisted in. It has been planned in advance—there is a clearly defined goal and a particular path to follow for its attainment. The path is punctuated by perils; it is possible to be diverted along the way, to become confused, to wander off, and even to enjoy the blessing and then be ashamed. It is possible to request assistance and receive guidance. Others can either aid in the endeavor (by inviting and encouraging one’s progress) or detract from it (by presenting distractions or mocking the journey). The nature of salvation itself is not precisely defined. It is represented as deliverance from darkness, fatigue, and weariness with the world, and it somehow constitutes what is happy, sweet, pure, and desirable in superlative ways.

Although familiar to Latter-day Saints, this complex of ideas would have been very new to Lehi and his family, who would have been accustomed to thinking of both the conditions and rewards of salvation in the context of the house of Israel, covenants, and the material blessings of prosperity, political security, and tenure in the promised land. While an allegory is an effective vehicle for rendering a new complex of ideas both accessible and memorable, it is a less than optimal foundation for establishing doctrine; and in this regard, we sorely miss the preaching and prophesying that Lehi added by way of interpretation (see 1 Nephi 8:38) and that Nephi chose to omit at this point from his record. The doctrine will be provided later, an understanding of salvation that we will label here as the plan of salvation.

When we as Latter-day Saints speak of the plan of salvation, we generally mean God’s design—in its grandest scope—for the well-being of his children as individuals, from premortal existence through the three degrees of glory, sealed together in eternal family units. There is little evidence that the Nephites knew of the two extreme ends of the plan (even for Joseph Smith, a full understanding of this was revealed only gradually). Nevertheless, beginning with Lehi’s allegory of the tree in 1 Nephi 8, the Book of Mormon clearly teaches that mortality is a time of testing, that all people will eventually be returned to the presence of God in a resurrected state to be judged of their actions during the days of their probation, and that, while in mortality, individuals can choose to come to Christ, repent of their sins, and be saved from eternal captivity to the devil through the Atonement regardless of ethnicity, gender, or social station. [3] Although only the intermediate events of God’s plan, from mortality through judgment, were revealed to Lehi and his family, they were sufficient to instruct them (along with Nephi’s readers) in knowing how, as individuals, “to come unto . . . God . . . and be saved” (1 Nephi 6:4).

Lehi introduces salvation history (1 Nephi 10). Lehi preaches about a different aspect of salvation in 1 Nephi 10. He begins by prophesying of the return of the Jerusalem exiles from their captivity in Babylon, and he then predicts that God will again intervene in Israel’s history at a very specific time and place: “Yea, even six hundred years from the time that my father left Jerusalem, a prophet would the Lord God raise up among the Jews—even a Messiah, or, in other words, a Savior of the world” (1 Nephi 10:4). Although Lehi is alluding here to a well-known prophecy from Moses (see Deuteronomy 18:15, 18), the specificity of his teaching regarding both the timing and identity of this prophet is communicated as new revelation. Lehi has searched the scriptures and found additional corroborating witnesses, and he goes on to affirm “how great a number [of the prophets] had testified of these things, concerning this Messiah” (1 Nephi 10:5). Nephi will later quote several of them from their writings on the brass plates (see 1 Nephi 19:8–17).

Lehi returns to speaking of the Jews and their relationship to both the Gentiles and also to “remnants of the house of Israel” (1 Nephi 10:14). He again provides a conceptual framework by way of an allegory—this time borrowed from the brass plates rather than of his own devising—comparing the future history of these various peoples (including his own descendants) to an olive tree with branches that are broken off and then grafted back in. Throughout these prophecies, he is always speaking of large groups. Clearly, the “Jews” and the “Gentiles” are made up of individuals who make personal decisions regarding the gospel; but, in Lehi’s discussion of salvation here, they are always treated by God as corporate entities.

In this part of his discourse, Lehi presents salvation as large-scale events in which God himself enters into the arena of human activity to judge or deliver entire peoples. We will use the term salvation history to designate these historical actions of corporate salvation, a term long used by biblical scholars to denote God’s redemptive activity in the human sphere. [4] In contrast to either spiritual concepts of redemption or secular accounts of history, salvation history refers to the sum of those occasions in which God intervenes in human affairs to work out his divine purposes through this-worldly events. Promised blessings are typically both temporal and collective in nature, including land, prosperity, posterity, and political security. Before 600 BC, salvation history was the standard way of reflecting on God’s relationship with his people.

Within this theological construct, it is understood that God reveals himself to Israel particularly through “saving acts” that simultaneously offer salvation to the righteous and judgment upon the wicked. These acts include such historical events as the Exodus, the offering of the Mosaic covenant, and the establishment of the children of Israel in the land of Canaan.

In keeping with this tradition, Lehi prophesies in 1 Nephi 10 that the Jews will be restored from captivity only to be scattered again, the Lehites will be led to their own land of promise, and the Gentiles will receive a witness of the Holy Ghost and, eventually, the fulness of the gospel. In Nephi’s overarching intention to persuade all men to come unto God and be saved (see 1 Nephi 6:4), the term “men” applies as much to these corporate groups as to individuals, just as “saved” applies to the groups’ receipt of such collective blessings as their restoration as a nation, their tenure in a land of promise, and their blessing of having the presence of God in the midst of their community. Although a serious concern with the corporate salvation of the house of Israel is lost from the bulk of the Nephite record after the demise of the first generation that migrated from Jerusalem, it is restored to prominence in the prophecies of the resurrected Jesus as recorded in 3 Nephi 16:4–20 and 20:10–26:5. Salvation history is never thereafter far from the Nephite record keepers’ minds as they recognize (and direct) their own writings as a vehicle of both salvation and judgment to the Jews, Gentiles, and Lehites of latter days. [5]

Nephi’s Vision as Integrating and Elaborating on Lehi’s Two Aspects of Salvation

At the conclusion of Nephi’s presentation of Lehi’s wilderness address, he has not made it obvious for his readers how the allegories of the two trees (which, in turn, represent the plan of salvation and salvation history) fit together thematically or otherwise. In Nephi’s telling, the meaning was apparently unclear to him on first hearing as well, since his initial response was to inquire of the Lord to “see, and hear, and know of these things” (1 Nephi 10:17). It seems here that this desire was not so much for the spiritual encounter he ultimately received as it was for a comprehensive understanding of his father’s teachings.. Nephi affirms the unfolding of God’s mysteries to those who diligently seek for it (see 1 Nephi 10:19); and, once he has been carried away in the Spirit, his request, somewhat surprisingly, is to know the interpretation of the allegory of the tree rather than to taste of the precious fruit (see 1 Nephi 11:10–11). In reporting his own vision, Nephi will forge a conceptual unity between the two aspects of salvation that he has to this point kept separated. [6]

We need to keep in mind that the meaning of Lehi’s dream is only half of what Nephi sought to understand after listening to his father’s teachings. [7] In the vision he receives, Nephi is first offered a clear identification of elements from the dream in plan of salvation terms: the tree and the fountain represent the love of God, the iron rod is the word of God, the river is the depths of hell, the mists of darkness are temptations of the devil, and the large and spacious building is the pride of the children of men (see 1 Nephi 11:25; 12:16–18). But Nephi’s angelic guide goes on to interpret these same symbols in salvation history terms as well, now identifying the tree as the tree of life from the Garden of Eden (thus linking a saving act with individual salvation, a topic Lehi will return to in 2 Nephi 2:15–23); the spacious building represents those who persecute the Apostles, and later the Lehites who, in their folly, war against each other (see 1 Nephi 11:35–36; 12:18–19); and the mists are identified as precursors to the judgments that will befall Lehi’s descendants before both the calamities preceding Christ’s Nephite visitation and their subsequent annihilation (see 1 Nephi 12:4, 17, 19).

While interspersing interpretative commentary on Lehi’s dream from 1 Nephi 8, the presentation of the vision follows the outline provided by Lehi’s prophecies from 1 Nephi 10. Nephi first witnesses the mortal coming and baptism of the Messiah (see 1 Nephi 11:14–27; see also 10:4, 9–10), with an explicit reference to Lehi’s account: “I looked and beheld the Redeemer of the world, of whom my father had spoken, and I also beheld the prophet who should prepare the way before him” (1 Nephi 11:27, see also 10:5, 7). Immediately before this disclosure, the angel reveals to Nephi that Jesus Christ is the centerpiece of both portions of Lehi’s teachings by identifying the tree of the precious fruit with “the Lamb of God” (1 Nephi 11:21; see also 1 Nephi 10:10).

Like his father before him, Nephi also “[speaks] much concerning the Gentiles, and also concerning the house of Israel” (1 Nephi 10:12). Although he makes no explicit reference in his vision to the allegory of the olive tree, he does provide further interpretation of it by mentioning both the judgment and scattering of Israel and a detailed description of his own family’s future in the land of promise (see 1 Nephi 12:1–23; 13:39; see also 10:13). Where Lehi prophesies that “after the Gentiles had received the fulness of the Gospel, the natural branches of the olive-tree, or the remnants of the house of Israel, should be grafted in, or come to the knowledge of the true Messiah” (1 Nephi 10:14), Nephi provides an explanation of the prophecy in terms of future saving acts: the Lord will manifest himself in the flesh to both the Jews and the Lehites; both of these peoples will record accounts of the Lord’s ministry, and then through these accounts (and through the Holy Ghost) the Lord will manifest himself to the Gentiles. [8] Once in the possession of the Gentiles, the records of the Jews and the Lehites “shall be established in one” and “shall make known to all kindreds, tongues, and people, that the Lamb of God is the Son of the Eternal Father, and the Savior of the world” (1 Nephi 13:40–41). Nephi describes how, in the latter days, the salvation of the house of Israel and the salvation of the Gentiles will be intertwined. God’s favors will be shown to each in turn so that salvation may ultimately be offered to the entire world (see 1 Nephi 13:42; 14:7).

Additional Development of Lehi’s Two Aspects of Salvation

When Nephi takes up the task of presenting the two aspects of God’s saving work to his readers, he begins, as he tells us Lehi did, by relating the two allegories in 1 Nephi 8 and 10, thus rendering accessible the broad contours of the plan of salvation and salvation history. In recounting the remainder of Lehi’s teachings in the valley of Lemuel, Nephi additionally presents to his readers what is presumably familiar to them from Israel’s scriptures (allusions to specific passages, a prophecy of the Jews returning from exile, an understanding of God’s saving acts on Israel’s behalf, and so forth). Only then does he introduce the innovative prophecies and doctrines that have been gradually unfolded to his family.

Regarding salvation history, Lehi and his sons find much prophetic collaboration for their own revelations in the brass plates, which is hardly surprising since revealing such acts before they occur is one of the primary responsibilities of Israel’s prophets (see Amos 3:7). Lehi, as we have seen, alludes to Moses’ teachings in Deuteronomy 18 regarding the coming of the Messiah (see 1 Nephi 10:4). Nephi quotes this verse (see 1 Nephi 22:20–21), [9] as well as passages from Zenock, Neum, and Zenos (see 1 Nephi 19:10–12). Most of the cited scriptures provide support for new prophecies regarding God’s future dealings with Israel (see 1 Nephi 15:20; 19:22–24; 2 Nephi 6:4–5; 25:7–8). Lehi borrows his allegory of the olive tree in 1 Nephi 10 from Zenos, and he quotes an extensive passage from Joseph of Egypt in 2 Nephi 3. Nephi includes most of Isaiah’s chapters 2–14, 29, 48–49 verbatim, along with dozens of individual verses and distinctive phrases; [10] and Jacob quotes Isaiah 49:22–52:2 in 2 Nephi 6–8 and later includes Zenos’s entire allegory in Jacob 5. In all cases, their incorporation of the words of brass plates’ prophets is careful, deliberate, and nuanced, supporting their own revelations and demonstrating the great value they placed on these records.

The many citations likewise confirm that for Lehi and his sons salvation history was a familiar means of understanding God’s saving acts in the context of Israel and her covenants. In contrast, the relative scarcity of prophetic corroboration for Lehi’s plan of salvation teachings (Lehi refers to Genesis 3:4–5, 23–24 and Isaiah 14:12 in 2 Nephi 2; Jacob and Nephi both quote Isaiah 55:1 at 2 Nephi 9:50 and 26:25 respectively) demonstrates just how original this doctrine was for Lehi’s family. Nephi admits to his brothers that Lehi “truly spake many great things . . . which were hard to be understood, save a man should inquire of the Lord” (1 Nephi 15:3). He, Jacob, and Lehi do inquire and are repeatedly blessed with divine instruction.

The varied but unquestionably authoritative nature of the inspiration the three of them receive confirm its truth value, as they appeal to visions (see 1 Nephi 8:2; 11:1; 2 Nephi 1:4; 2:3; 4:23, 25), the voice of the Lord (see 1 Nephi 13:33–37; 14:3, 7; 2 Nephi 1:20; 9:16, 23; 10:7–19; 2 Nephi 28:30–29:14; 31:11–15), angelic communication (see 1 Nephi 11–14; 19:8–10, 2 Nephi 6:9, 11; 10:3), and the instruction of the Spirit (see 1 Nephi 10:17; 15:12; 2 Nephi 1:6; 4:12; 25:11; Jacob 4:15). As Nephi reflects upon this learning process, he expresses deep satisfaction with all that he has come to know: “For my soul delighteth in the scriptures, and my heart pondereth them, and writeth them for the learning and the profit of my children. Behold, my soul delighteth in the things of the Lord; and my heart pondereth continually upon the things which I have seen and heard (2 Nephi 4:15–16).”

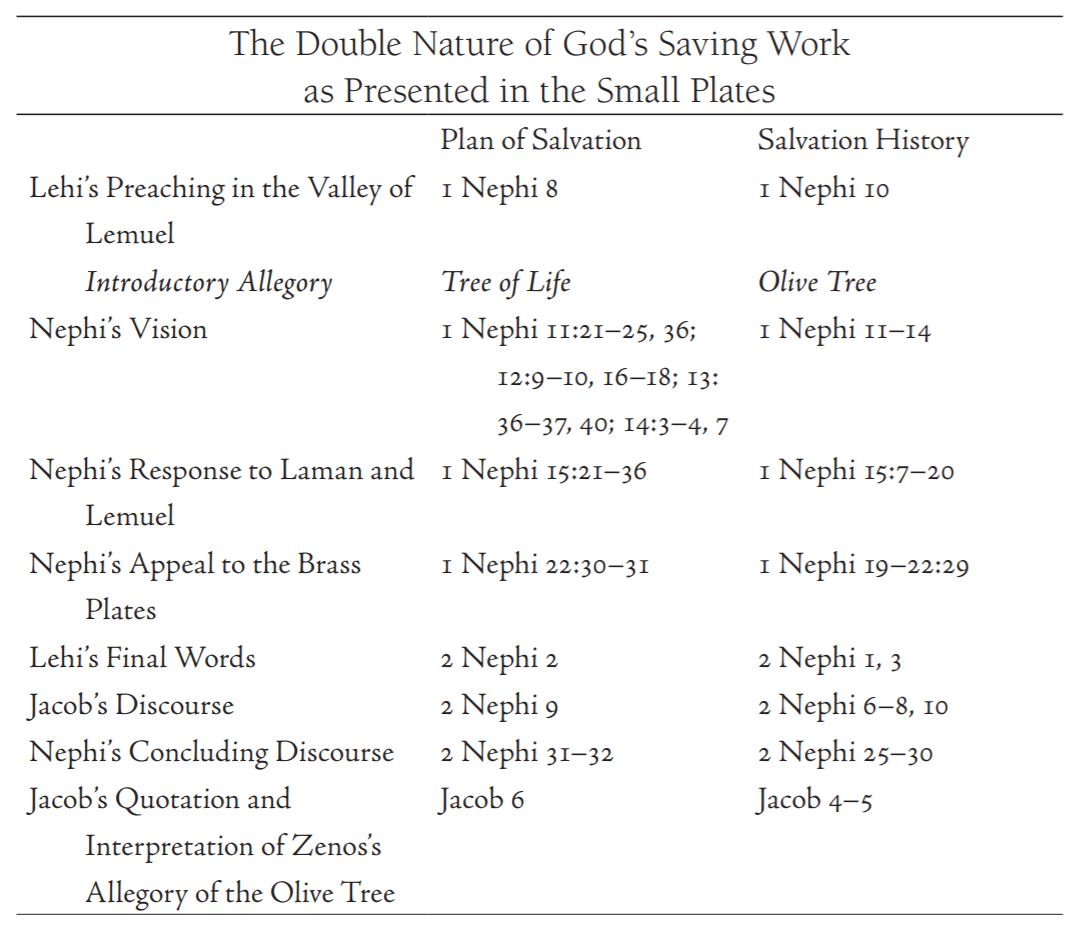

The expanded understanding of Lehi and his sons is expressed in seven additional discourses, six reported by Nephi and the seventh added by Jacob in his own writings. All of these writings focus on the nature of salvation, and each incorporates both the plan of salvation and salvation history, the two aspects Lehi first introduced in his teachings in the valley of Lemuel. [11] The content of these eight salvation-focused discourses can be categorized as follows:

We see here the inclusion of two sermons each from Lehi and Jacob as well as four from Nephi himself. Evidently, it is important to Nephi to confirm that these doctrines of salvation were independently affirmed by multiple teachers. Elsewhere he explains this commitment to the Deuteronomic law of witnesses: “I will send their words forth unto my children to prove unto them that my words are true. Wherefore, by the words of three, God hath said, I will establish my word.” Although Nephi is explicitly referring here to the revelations of Isaiah and Jacob, Lehi’s testimony certainly applies as well. He concludes, “Nevertheless, God sendeth more witnesses, and he proveth all his words” (2 Nephi 11:3; see also Deuteronomy 19:15).

Note the consistency of how all of the eight above-listed discourses address both the plan of salvation and salvation history, even if only for a few verses. Sometimes the two aspects of salvation are thoroughly integrated, as in Nephi’s vision; at other times they are balanced but clearly divided, as in Nephi’s response to Laman’s and Lemuel’s questions or in Lehi’s final words; and sometimes one aspect or another is emphasized, as in Nephi’s appeal to the brass plates. But both aspects of salvation are always included.

Also note that in contrast to Lehi’s opening discourse, which presents the plan of salvation first, subsequent iterations always begin with salvation history. This may simply reflect the words as they were originally uttered, but the consistency of the presentation suggests that it may have been Nephi’s intention generally to begin with more familiar, scripture-based teachings before moving on to newly revealed tenets. Regardless, there is a significant development of both detailed prophecy and plain-spoken doctrine as Nephi progresses through his reporting of these discourses, beginning with the allegories that distinguish the two aspects of salvation in 1 Nephi 8 and 10, and culminating in his own teachings at 2 Nephi 25–32 which specify the role that Lehi’s posterity will play in the coming forth of a salvific book in the latter days and then finally enumerate conditions for attaining individual salvation.

There are dozens of examples of how Lehi, Nephi, and Jacob clarify and integrate the concepts of the plan of salvation and salvation history in their discourses, either by means of explicit instruction or by such indirect strategies as scriptural allusion and recontextualization, wordplay, and the juxtaposition of prophecies. By way of illustration, we will consider a few examples from each of these founding Nephite prophets. First, we will see how Lehi deftly recontextualizes salvation history prophecies from the brass plates in plan of salvation terms, followed by the observation of Jacob’s clever use of wordplay to highlight connections between the two aspects of salvation. Then we will consider Nephi’s most significant integration of the plan of salvation and salvation history as we trace the development of his teachings about the Atonement of Jesus Christ over the course of his writings, concluding with his return to Lehi’s wilderness teachings in declaring how it is that individuals can “come unto the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, and be saved” (1 Nephi 6:4).

Lehi’s recontextualization of salvation history prophecies in plan of salvation terms. Nephi opens his account of Lehi’s final words to his family with a paraphrase of the blessings they have thus far received. Lehi’s first quoted words report another revelation: “For behold . . . I have seen a vision, in which I know that Jerusalem is destroyed” (2 Nephi 1:4), and he continues to prophesy about the welfare of his posterity in their new land of promise. Later, when he shifts to admonishment, he elaborates on a passage from Isaiah: [12]

|

Isaiah 52:1–2 Awake, awake, put on thy strength, O Zion; put on thy beautiful garments, O Jerusalem, the holy city; for henceforth there shall no more come into thee the uncircumcised and unclean. Shake thyself from the dust; arise, and sit down, O Jerusalem; loose thyself from the bands of thy neck, O captive daughter of Zion. |

2 Nephi 1:13–14 O that ye would awake; awake from a deep sleep, yea, even from the sleep of hell, and shake off the awful chains by which ye are bound, which are the chains which bind the children of men, that they are carried away captive down to the eternal gulf of misery and woe. Awake! and arise from the dust. |

Note the similarity in theme and distinctive wording here: both passages cluster the exhortations to awake and shake oneself or arise from the dust in the context of the chains or bands of captivity. But where Isaiah is foreseeing the deliverance of Jerusalem from Babylonian captivity through the perspective of salvation history, Lehi recontextualizes the prophecy in plan of salvation terms for his wayward sons. Both the placement of his words and its revised message are emotionally devastating. After praising God for the land of liberty to which he has brought them, Lehi indicates that Laman and Lemuel are already in captivity, not politically or temporally but rather with the chains of hell, which will bring them finally to captivity in the “eternal gulf of misery and woe.” Lehi takes the same words that Isaiah has used to proclaim deliverance and instead warns of destruction.

Later in the discourse, after giving his most complete description of the plan of salvation, Lehi again conflates the two aspects of salvation by recontextualizing a critical text from the brass plates. Consider his application of the famous conclusion of the Lord’s covenant with the children of Israel just prior to their entry into Canaan: “I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing: therefore choose life, that both thou and thy seed may live” (Deuteronomy 30:19; emphasis added). Although Moses is speaking here to the people collectively in a salvation history mode, Lehi’s adaptation at 2 Nephi 2:27–28 will again shift to a plan of salvation context (including a corresponding shift from mortal “life” to “eternal life”): “Wherefore, men are free . . . to choose liberty and eternal life, through the great Mediator of all men, or to choose captivity and death, according to the captivity and power of the devil. . . And now, my sons, I would that ye should look to the great Mediator, and hearken unto his great commandments; and be faithful unto his words, and choose eternal life.”

Jacob’s use of wordplay to highlight connections between salvation history and the plan of salvation. For a second example of a particular strategy for integrating salvation history and the plan of salvation, we will consider Jacob’s use of several instances of wordplay in 2 Nephi 9. Several chapters earlier, following the general pattern, Jacob opens this discourse with a discussion of salvation history that appeals to both established scripture and new revelation (see 2 Nephi 6:4, 8–9). After interspersing his own commentary with a lengthy quotation from Isaiah, Jacob makes a transition in 2 Nephi 9 to a discussion of the plan of salvation by first identifying and then manipulating an ambiguity.

“For I know that ye have searched much, many of you, to know of things to come” Jacob tells his listeners. In keeping with the salvation history emphasis of the discourse so far, he continues by relating a prophecy with which his audience is by now very familiar: “I know that ye know that in the body [the Lord] shall show himself unto those at Jerusalem from whence we came” (2 Nephi 9:4–5). But in between these two comments, and camouflaged by his use of similar rhetoric, Jacob inserts an apparent non sequitur: “I know that ye know that our flesh must waste away and die; nevertheless, in our bodies we shall see God.” The ambiguity Jacob is playing off here is the particular content of the “things to come.” Is it the salvation history proclamation of the coming of the Son of God or the plan of salvation inevitability of postmortal judgment? Jacob’s presentation suggests both and also implies a connection between the two events, not just because they share the rather generic connections of Nephite interest and futurity but also because they each involve the literal witnessing of God.

As he moves on to a comprehensive articulation of how it is that “in our bodies we shall see God,” Jacob continues to manipulate ambiguities to his advantage by applying plan of salvation meanings to familiar salvation history concepts. One of his most clever wordplays in this regard is his use of the salvation history term “restoration.” As 2 Nephi 9 opens, Jacob’s theme has been the dual nature of this concept for Israel’s future when, in the latter days, “they shall be restored to the true church and fold of God” and also “established in all their lands of promise” (v. 2). But in short order he has applied both of these aspects—a spiritual sense as well as a physical one—to resurrection itself, in which hell and paradise will each deliver up the spirits they contain and the grave will deliver up its captive bodies so that “the bodies and the spirits of men will be restored one to the other” (vv. 12–13). Later, Jacob tries yet another permutation, this time comparing a plan of salvation sense of united, resurrected bodies being “restored to that God who gave them breath” (v. 26; emphasis added) with a salvation history sense of his distant posterity as a group being “restored” to God by coming to “the true knowledge of their Redeemer” (2 Nephi 10:2; emphasis added).

Nephi’s presentation of the Atonement of Christ as the ultimate integration of salvation history and the plan of salvation. Absolutely the most significant integration of salvation history and the plan of salvation in the small plates is its prophetic declaration of the person and mission of Jesus Christ. He is the central figure in each aspect of salvation, and we will consider in turn how his coming into the world constitutes a saving act for entire peoples, and also how it provides the necessary mediation for the eternal deliverance of individual souls. Indeed, he is the only “way” or “name” given whereby man can be saved (see 2 Nephi 9:41; 25:20; 31:21), either collectively or individually.

Lehi begins his prophesying of the coming of Christ in 1 Nephi 10 in terms of salvation history. He is the prophet to be raised up among the Jews (see v. 4). He will provide redemption for the sins of the world as “the Lamb of God,” that is, in the ritual terms of the Mosaic law, as a scapegoat for the collective (v. 10). Nephi expands the understanding of the Messiah’s coming as a saving act when he makes clear from his own vision that Christ will manifest himself in turn to the Jews, the Lehites, and the Gentiles. In each case, the divine manifestation will cause division among an entire people, resulting in both judgment and salvation.

Thus Nephi reports that when the Holy One of Israel comes in the flesh among the Jews, he will minister in power and great glory, performing mighty miracles, healing the sick, and casting out devils (see 1 Nephi 11:28, 31). These gracious actions in themselves offer deliverance for their recipients and are sufficient evidence for those who observe them to know that he is their God. Nephi assures us that those at Jerusalem who believe in Christ will be saved in the kingdom of God (see 2 Nephi 25:13), but the vast majority will stiffen their necks against him, judge him to be a thing of naught, and cast him out from among them (see 2 Nephi 10:5; 1 Nephi 19:9; 11:28). In their rejection of Jesus, the Jews will collectively bring down the judgments of God upon themselves, or, as Zenos prophesied, “they shall be scourged by all people, because they crucify the God of Israel, and turn their hearts aside, rejecting signs and wonders, and the power and glory of the God of Israel” (1 Nephi 19:13; emphasis added; see also 2 Nephi 6:10; 10:6; 25:12).

Nephi asserts that Jesus’ postmortal manifestation to the Lehites will also constitute a saving act. In this case, the division of the people will precede his coming. The wicked who kill those prophets and Saints that testify of Christ will be destroyed in the great and terrible judgments preceding his visitation (see 1 Nephi 12:4–5; 2 Nephi 26:3–6), but to those who believe in the prophecies and wait patiently for his coming, “the Son of righteousness shall appear unto them, and he shall heal them, and they shall have peace with him” (2 Nephi 26:9). Again, these are momentous events that will be experienced by multitudes, all together, in historical time.

Both Lehi and Nephi describe the manifestation of Jesus Christ to the Gentiles, a manifestation which will not take the bodily form that it does for the Jews and Lehites. [13] Rather, Lehi prophesies that after the Messiah has risen from the dead, he will make himself known to the Gentiles by the Holy Ghost and then, in the latter days, will offer to them “the fulness of the Gospel” (1 Nephi 10:11, 14). Nephi explains that the Lamb of God will “manifest himself unto them in word, and also in power, in very deed,” such that “if the Gentiles repent it shall be well with them; . . . [but] whoso repenteth not must perish” (1 Nephi 14:1, 5).

Jesus’ coming into the world also provides the necessary mediation for the eternal deliverance of individual souls in accordance with the plan of salvation. Lehi, Nephi, and Jacob each attest that the mortal mission of Jesus Christ will culminate in his making intercession with the Father for all of the children of men. According to Lehi, “redemption cometh in and through the Holy Messiah,” who “offereth himself a sacrifice for sin” (2 Nephi 2:6, 7). Nephi indicates that he will be “lifted up upon the cross and slain for the sins of the world” (1 Nephi 11:33). Jacob clarifies that God will raise all men from physical death by the power of Christ’s Resurrection, while those who have faith in the Redeemer can also be saved from spiritual death by the power of his Atonement (see 2 Nephi 9:10–16; 10:25). It is finally in 2 Nephi 31 that Nephi presents the “doctrine of Christ” (2 Nephi 31:2), indicating with plainness and precision how it is that individuals can come unto Christ and be so saved.

Nephi’s return to Lehi’s wilderness teachings in his concluding discourse. In delivering this culminating message, Nephi returns to both halves of Lehi’s teachings in the valley of Lemuel, as well as to his own sweeping angelic vision from 1 Nephi 11–14. In doing so, he brings the fulness of his gospel understanding back to its foundational origins, subtly testifying of just how much salvific truth the Lord has revealed to his family. He opens his concluding remarks by inviting readers to return with him to those early teachings, recalling first the Messiah’s baptism foretold by Lehi in 1 Nephi 10 but not commented on since his own vision in 1 Nephi 11: “I would that ye should remember that I have spoken unto you concerning that prophet which the Lord showed unto me, that should baptize the Lamb of God, which should take away the sins of the world” (2 Nephi 31:4, emphasis added).

Although referencing his own experience here (“I have spoken . . . concerning that prophet which the Lord showed unto me,” see also vv. 8, 17), Nephi acknowledges the dependency of his vision upon his father’s prior prophecy by employing Lehi’s words in describing John the Baptist: “After he had baptized the Messiah with water, he should behold and bear record that he had baptized the Lamb of God, who should take away the sins of the world” (1 Nephi 10:10; emphasis added). The latter phrase appears only in these two verses in the small plates, and although the designation of Jesus as the “Lamb of God” is a key phrase in Nephi’s vision, employed there more than two dozen times, it, too, has not been mentioned since in Nephi’s writings. The fact that he now employs it again several times in quick succession (see 2 Nephi 31:4–6) provides strong support for the intentionality of the allusion here to earlier teachings.

As Nephi continues with his meditation on Jesus’ baptism, he will also incorporate three distinctive, though as yet undefined, elements from Lehi’s dream in 1 Nephi 8: the invitation from the man in a white robe to “follow me” (see v.6; 2 Nephi 31:10, 12–13), the strait and narrow path (see v. 20; 2 Nephi 31:18, 19), [14] and the necessity for travelers to the tree to continue “pressing forward” (see vv. 21, 24; 2 Nephi 31:20). He begins by posing a question: “And now, if the Lamb of God, he being holy, should have need to be baptized by water, to fulfil all righteousness, O then, how much more need have we, being unholy, to be baptized, yea, even by water?” (2 Nephi 31:5). Drawing on insights from his father’s dream, Nephi responds that one of the purposes of Christ’s baptism was to show humankind the way to salvation: “It showeth unto the children of men the straitness of the path, and the narrowness of the gate by which they should enter, he having set the example before them. And he said unto the children of men, ‘Follow thou me’” (2 Nephi 31:9–10, emphasis added).

Appealing to what may be his most remarkable revelation of all, Nephi reports crucial information to his readers, defining the conditions of their individual salvation. Instead of claiming the Spirit, a vision, or even an angelic guide as his authority (as he and his family members have done in the past to support their developing understanding of salvation), Nephi instead relates a scripturally unprecedented exchange between the Father and the Son, whose voices come to him in turn, in essence enacting a saving covenant as they unfold the principles and ordinances of the gospel:

The Father: “Repent ye, repent ye, and be baptized in the name of my Beloved Son.”

The Son: “He that is baptized in my name, to him will the Father give the Holy Ghost, like unto me; wherefore, follow me, and do the things which ye have seen me do.”

The Son: “After ye have repented of your sins, and witnessed unto the Father that ye are willing to keep my commandments, by the baptism of water, and have received the baptism of fire and of the Holy Ghost, . . . and after this should deny me, it would have been better for you that ye had not known me.”

The Father: “Yea, the words of my Beloved are true and faithful. He that endureth to the

end, the same shall be saved” (see 2 Nephi 31:11, 12, 14, 15).

Interspersed with these statements is a running commentary in which Nephi highlights Jesus’ plan of salvation role as exemplar and encourages his readers to follow both the actions and commandments of Christ. Nephi expresses this encouragement in terms from Lehi’s dream, concluding with a final promise from the Father:

And now, my beloved brethren, after ye have gotten into this strait and narrow path, I would ask if all is done? Behold, I say unto you, Nay; for ye have not come thus far save it were by the word of Christ with unshaken faith in him, relying wholly upon the merits of him who is mighty to save. Wherefore, ye must press forward with a steadfastness in Christ, having a perfect brightness of hope, and a love of God and all men. Wherefore, if ye shall press forward, feasting upon the word of Christ, and endure to the end, behold, thus saith the Father, Ye shall have eternal life (2 Nephi 31:19–20; emphasis added).

The return of a few key phrases reminds us of Lehi’s description of those who were “pressing forward . . . holding fast to the rod of iron” (1 Nephi 8:30), a rod later interpreted as “the word of God” (1 Nephi 11:25).

The Fulness of the Gospel

In 1 Nephi 6:4, Nephi states that his intention in writing the book that is itself to become a saving act in latter days is to “persuade men to come unto the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, and be saved.” We have seen how he has carefully devised his own contribution to that record by using his father Lehi’s distinction in 1 Nephi 8 and 10 between the two aspects of God’s saving work: the plan of salvation, for the eternal deliverance of individuals from death, hell, and captivity to the devil; and salvation history, the divine intervention in human affairs which delivers entire peoples from physical destruction and captivity, both to their enemies and to ignorance.

In addition to these two aspects of salvation, the phrase “the fulness of the Gospel” was also introduced by Lehi in his foundational discourse in the valley of Lemuel (1 Nephi 10:14). Nephi clarifies the concept in 1 Nephi 15:13–14, emphasizing that this fulness will come unto the Gentiles in the latter days, confirming Israel’s covenant relationship with God, testifying of the Redeemer of the world, and instructing all humankind in “the very points of his doctrine, that they may know how to come unto him and be saved.” It may be that the integration of the plan of salvation and salvation history found in Nephi’s record can be profitably understood as constituting this fulness of the gospel—the summation of the tidings of great joy declaring that God has prepared a way to deliver humankind from bondage, whether spiritual or temporal, individual or collective.

Notes

[1] Lehi himself never refers to the tree in his dream as the tree of life. This identification was added by Nephi at 1 Nephi 11:25.

[2] Nephi does seem to be aware of the parallel nature of the two sections of Lehi’s discourse even though he chooses not to highlight it at this point. This is evidenced in his conclusion of both sections with a reference to being “cast off” from the presence of God (1 Nephi 8:36–37; 10:21) and also with a comment that the preceding preaching occurred while Lehi “dwelt in a tent, in the valley of Lemuel” (1 Nephi 9:1; 10:16).

[3] Many of the great sermons included by Mormon and Moroni deal precisely with this theme, including King Benjamin’s discourse (see Mosiah 2–6); Abinadi’s prophesying (see Mosiah 12–17); Alma’s sermons and teachings to his sons (see Alma 5, 7, 36–42), Alma’s and Amulek’s preaching (see Alma 9–13; 32–34); Samuel the Lamanite’s prophesying (see Helaman 13–15); and Mormon’s sermon on faith, hope, and charity (see Moroni 7); see also Mormon’s lamentation at Helaman 12 and Moroni’s exhortation at Moroni 10.

[4] The term salvation history was popularized in the nineteenth century by J. C. von Hofmann as heilsgeschichte. For summaries of its widespread usage, see H. G. Reventlow, Problems of Old Testament Theology in the Twentieth Century (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1985), 87–110; Gerald G. O’Collins, “Salvation,” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 5:907–914; and John Ruemann, “Salvation History,” in The Encyclopedia of Christianity, ed. Erwin Fahlbusch and others (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans; Leiden: Brill, 1999–2008), 4:832–36.

[5] For Mormon’s and Moroni’s commitment to the concept of salvation history, see 3 Nephi 29–30; Mormon 3:17–22; 5:8–24; 7:1–10; Ether 2:11–12; 4:8–19; 12:22–29; title page.

[6] Previous authors have noted connections between Lehi’s dream at 1 Nephi 8 and Nephi’s vision of 1 Nephi 11–14, but they have not recognized that Lehi’s prophecies at 1 Nephi 10 were part of his original explication of his dream and that Nephi’s vision picks up elements from both chapters. See John W. Welch, “Connections Between the Visions of Lehi and Nephi,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 49–53; and in more detail in Corbin T. Volluz, “Lehi’s Dream of the Tree of Life: Springboard to Prophecy,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2, no. 2 (1993): 14–38.

[7] Or perhaps only a third, since there is textual evidence to suggest that Nephi’s vision also includes details from the vision Lehi received at the time of his prophetic call. Common notable details not identified in 1 Nephi 10 include the vision of one “descending out of heaven” (1 Nephi 1:9; 11:7; 12:6), the Messiah’s twelve followers (see 1 Nephi 1:10; 11:29; 12:7); and the book presented by one of the twelve (see 1 Nephi 1:11; 14:20–23).

[8] Interestingly enough, in Nephi’s telling it is the Gentiles who are to be grafted in to Israel (“numbered among the house of Israel,” 1 Nephi 14:2) and not the other way around as suggested by the allegory at 1 Nephi 10:14. Another slight discrepancy is that in Nephi’s reporting of the words of the Lord, the latter-day Gentiles are to receive “much of my gospel” (1 Nephi 13:34) rather than “the fulness of the Gospel” spoken of in 1 Nephi 10:14.

[9] Nephi seems to be applying Deuteronomy 18:18–19 here to the Lord’s Second Coming rather than to his mortal ministry. Jesus Christ applies the same prophecy to his Nephite ministry at 3 Nephi 20:23–26, equating the term “raise up” with his own Resurrection. In all three cases, though, the scripture is recognized as being fulfilled in the person of Jesus Christ.

[10] For a preliminary list of these phrasal quotations and allusions, see the footnotes for 1 Nephi 22 and 2 Nephi 25–30 in Grant Hardy, ed., The Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Edition (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2005).

[11] Several decades ago, Bruce W. Jorgensen suggested that typology might provide a unified reading of the Book of Mormon based on Lehi’s dream, but his short article did not allow for sustained analysis along these lines, and as he himself admitted, because the dream was not a historical event, it was therefore “not properly a type or figure.” More recently, Steven L. Olsen has proposed that Mormon patterned his historical narrative on Nephi’s vision, but the correspondence between Nephi’s prophecies and their fulfillment in later history seems natural enough both in terms of chronology and major events. I believe there is another continuity between the small plates and Mormon’s abridgment of the large plates in the way the theological breakthrough realized by Lehi and Nephi with regard to salvation is explored and elaborated on by later Nephite prophets. See Bruce W. Jorgensen, “The Dark Way to the Tree: Typological Unity in the Book of Mormon,” in Literature of Belief: Sacred Scripture and Religious Experience, ed. Neal E. Lambert (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1981), 217–32; and Steven L. Olsen, “Prophecy and History: Structuring the Abridgments of the Nephite Records,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 15, no. 1 (2006): 18–29.

[12] Lehi actually seems to be combining two Isaiah passages here in his expansion, both of which feature the keyword “dust.” In addition to alluding to Isaiah 52:1–2, Lehi also clusters the following distinctive phrases from Isaiah 29: “deep sleep” (2 Nephi 1:13; Isaiah 29:10), coming out of the dust (see 2 Nephi 1:14, 21, 23; Isaiah 29:4) and “out of obscurity” (2 Nephi 1:23; Isaiah 29:18), although there is little thematic overlap. Nephi will quote Isaiah 29:3–24 in 2 Nephi 26–27.

[13] The resurrected Jesus Christ confirms to the Nephites that his mission to manifest himself directly (either by his voice or by his physical presence) applies only to the house of Israel. The Gentiles, in contrast, are to receive the testimony of Israel and the witness of the Holy Ghost (see 3 Nephi 15:19–16:3).

[14] Jacob also alludes to the strait and narrow path at 2 Nephi 9:23, 41, where he introduces the notion of a gate which may or may not have been an element in either Lehi’s dream or his subsequent interpretation of the dream. Mormon, in an apparent allusion to Lehi, makes mention of “the gate of heaven” as well as of laying hold on “the word of God” and walking “a strait and narrow course across that everlasting gulf of misery” (Helaman 3:28–29). A “strait” or “narrow” gate is mentioned in 2 Nephi 31:9, 17–19; 33:9; and Jacob 6:11.