The Navigator, or Samoan, Islands, September 1895–October 1895

Reid L. Neilson and Riley M. Moffat, eds., Tales from the World Tour: The 1895–1897 Travel Writings of Mormon Historian Andrew Jenson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 141–61.

As a rule, the [Samoan] natives are kind and hospitable to the elders as they travel among them. When visiting in the outlying villages, they are always invited in and treated to food and lodging, the best the people have, free of charge. When at their regular stations, the elders make their home in the respective meetinghouses, which are generally partitioned off into two rooms, the smaller of which is occupied by the elders as a private apartment and the larger one reserved for meeting purposes. When at their stations, the natives always bring them the necessary food, which generally consists of taro, breadfruit, bananas, yams, fish, oranges, and other kinds of fruits. The elders have learned from long experience that this kind of diet is healthier and better for them while in the tropics than imported or foreign food. In traveling around on the different islands, the brethren generally travel on foot, occasionally also in small boats along the coasts; but the latter mode is fraught with considerable danger and has of late years been discouraged. In going from island to island, passages are often obtained on trading schooners and other small crafts free of charge; at other times they have to pay.

—Andrew Jenson[1]

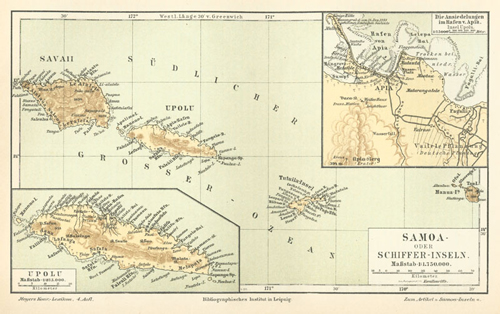

Samoa, Meyers Konversations-Lexikon (Leipzig: Verlag des Bibliographischen Instituts, 1885)

Samoa, Meyers Konversations-Lexikon (Leipzig: Verlag des Bibliographischen Instituts, 1885)

“Jenson’s Travels,” September 18, 1895 [2]

Saleaula, Savai‘i, Samoa

Wednesday, September 11. This is my second Wednesday this week. I spent the day at Fagali‘i, Samoa, culling historical data from the mission records, being assisted by Elder William G. Sears, the secretary of the mission.

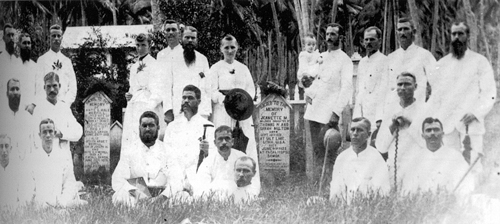

Thursday, September 12. I continued my labors of yesterday and also visited the private graveyard, located on a hill about three hundred yards southeast of the mission house, (Photo of Fagali‘i cemetery) where the earthly remains of Elder Ransom M. Stevens, Sister Ella A. Moody, and three children of Elder Thomas H. Hilton and wife are deposited. Elder Stevens died April 28, 1894; Sister Moody, May 24, 1895. Elder Stevens is buried in the grave that was formerly occupied by the remains of Sister Kate E. Merrill, who died in 1891, but whose remains were taken home by her husband when he returned from his mission in 1894. Sister Merrill was the first of our missionaries who died in Samoa. Compared to time and number, the Samoan Mission history records more deaths among our missionaries than any other mission we have so far established as a church—one elder, two missionary sisters, and three children in seven years out of eighty missionaries who, since 1888, have been sent from Zion to labor in Samoa and Tonga.

Mormon missionaries at Fagali'i cemetery. Courtesy of R. Carl Harris.

Mormon missionaries at Fagali'i cemetery. Courtesy of R. Carl Harris.

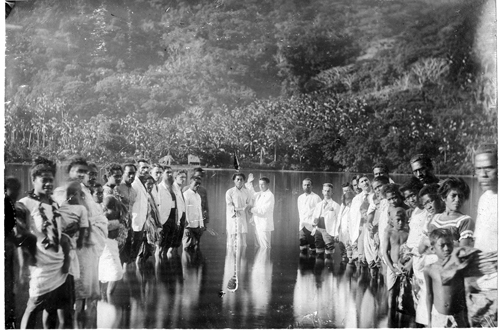

The Samoan Mission embraces two important groups of the South Pacific Islands, namely: Samoa, or the Navigator Islands, and Tonga, or the Friendly Islands. At present, 33 elders from Zion are laboring as missionaries on the two groups, to wit, 23 in Samoa and ten in Tonga. Of those engaged in the ministry in Samoa, 11 are laboring on the island of Upolu, 6 on Savai‘i, and 6 on Tutuila. There are 11 regularly organized branches of the Church, which also constitute that many permanent missionary stations, at each of which two elders are located, except at headquarters at Fagali’i, where there are at present three, including the president of the mission. At all these stations or branches, regular Sabbath meetings—and, in some, Sunday Schools—are held, presided over, and conducted by the elders who, however, are assisted by native Saints. According to the statistical report for 1894, there were at the beginning of the present year 263 native Saints in the mission, namely, 147 males and 116 females. Of the native brethren 25 held the priesthood, 4 of them being elders, 2 priests, 13 teachers, and 6 deacons. Of the total number of native Saints mentioned, 97 were on the island of Upolu; 84 on Tutuila and ‘Aunu‘u; 71 on Savai‘i, and 11 in Tonga. To this might consistently be added 107 children belonging to members of the Church, namely, 42 on Upolu, 27 on Tutuila, 32 on Savai‘i, and 6 in Tonga. Since the mission was first established in Samoa in 1888, all the villages on the three principal islands (Upolu, Savai‘i, and Tutuila) have been visited, most of them many times. Tracts have also been distributed in all the villages and meetings held in nearly all. The elders stationed at the respective branches in Samoa do not confine their labors, by any means, to the particular village in which the meetinghouse or their headquarters are located, but extend their operations to the surrounding country. Thus every village on the three islands named are included in some one of the missionary circuits. As a rule, the natives are kind and hospitable to the elders as they travel among them. When visiting in the outlying villages, they are always invited in and treated to food and lodging, the best the people have, free of charge. When at their regular stations, the elders make their home in the respective meetinghouses, which are generally partitioned off into two rooms, the smaller of which is occupied by the elders as a private apartment and the larger one reserved for meeting purposes. When at their stations, the natives always bring them the necessary food, which generally consists of taro, breadfruit, bananas, yams, fish, oranges, and other kinds of fruits. The elders have learned from long experience that this kind of diet is healthier and better for them while in the tropics than imported or foreign food. In traveling around on the different islands, the brethren generally travel on foot, occasionally also in small boats along the coasts; but the latter mode is fraught with considerable danger and has of late years been discouraged. In going from island to island, passages are often obtained on trading schooners and other small crafts free of charge; at other times they have to pay. There is no interisland steamship accommodation in Samoa. The white traders, most of whom have married Samoan wives, are generally good to the elders and have shown them numerous acts of kindness. The Germans constitute the bulk of the white population in Samoa. After them the English and Americans rank as to number, and there are also a few Scandinavians. Seven white men are among those baptized in Samoa. In this connection I may also state that from 1888, when the mission was first opened, till the close of 1894, 342 persons were baptized in the Samoan Mission, (Photo of Samoan baptism) namely, 37 on the island of ‘Aunu‘u, 103 on Tutuila, 111 in Upolu, 78 on Savai‘i, and 12 in the Tongan part of the mission. Of this number, 57 have been excommunicated and 22 are dead.

Baptism in Samoa. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Baptism in Samoa. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

The natives of Samoa are a fine race of people physically, as fair skinned as the natives of Hawaii and Tonga. But while the Tongans are compelled by law to cover their bodies from shoulder to knee, no such law exists in Samoa. Hence the natives, on ordinary occasions, confine their clothing to their vale vale, or waistcloth. On Sundays, however, the men wear a shirt and the women a sort of sash in addition to the vale vale.

The opportunities of obtaining a livelihood in native style in Samoa are very good. It requires next to no effort at all to obtain the necessary food. Taro, or kalo, grows with but a very little help in the shape of cultivation, and this is the staple article of food on the group. Breadfruit is picked from the trees as it ripens for several months during the year, and the cocoanut is always to be had. Its flesh is used by the natives in the preparation of many of their “rare dishes.” When the breadfruit is out of season, and the people have neglected to plant taro, they are sometimes compelled to subsist, for months together, on bananas. At different times in past years, when the islands have been visited by hurricanes, which have blown down all the breadfruit and coconuts and often pulled up or broken down the trees themselves, the people have been reduced to a point of starvation until they could plant and reap bananas or until the next crop of breadfruit would ripen. The group of Manu‘a is an exception to this. There the people always keep a year’s supply on hand, and by this precaution have always escaped famine.

On the same principle that food is obtained so easy on Samoa, the natives also desire to secure salvation on as easy terms as possible. Hence our elders, with their practical religion and their “faith and works” doctrines, have a hard time of making converts. The sectarian “way to heaven” by faith alone is, as a rule, much preferred by the South Sea Islanders.

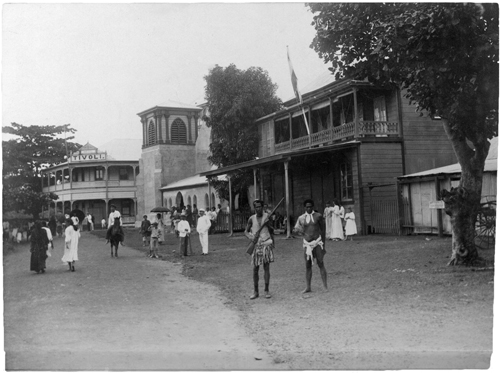

Street scene in Apia. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Street scene in Apia. Courtesy of Church History Library.

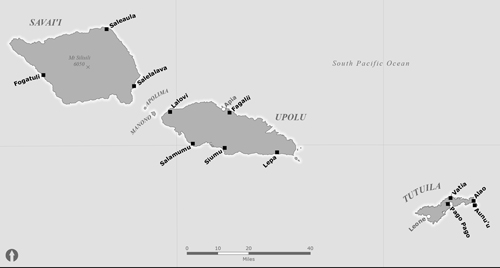

From a Samoan geography published in 1887 and from many other sources, I glean the following: The Samoan group is situated between south latitude 13˚30´ and 14˚20´ and west longitude 169˚24´ and 172˚45´. (Map of Samoa from Meyer’s 1885 Konversations Lexikon) There are ten inhabited islands in the group and a number of very small islets not inhabited. The distance from the Manu‘a group, which is situated the farthest east, to the westernmost point of Savai‘i, the west island, is 265 miles. The names on the east are Ta‘u, Olosega, Ofu, ‘Aunu‘u, Tutuila, Nu‘utele, Upolu, Manono, Apolima, and Savai‘i. The three first named constitute the Manu‘a group, which have a separate and distinct government of their own. The total area of all the islands is 1,650 square miles, and the number of inhabitants 34,000. The three islands—Upolu, Savai‘i, and Tutuila—are by far the largest and most important and contain the great bulk of the inhabitants. Samoa may be regarded as one of the loveliest, most agreeable, and productive of all the South Sea groups. The fertility of the soil is such that the cultivation of tropical plants yields abundant returns, and the means of subsistence are perhaps more easily obtained here than in any other part of the world. All the islands belonging to the Samoan group are volcanic, and their appearance are enchanting in many places, where the fine, fertile plains extend to the foot of the wooded hills. The Samoan Islands are quite subject to hurricanes, being situated so near the equator, where the disastrous storms are frequent. In April 1850, the capital (Apia) was almost entirely destroyed by one, and the terrible storm of March 15 and 16, 1889, by which seven American and German men-of-war were either totally or partly destroyed, is a circumstance still fresh in the memory of newspaper readers. Earthquakes are also frequent in Samoa, but not very severe; and they do little damage owing to the elasticity and strength of the native dwellings, which are entirely constructed of posts and light rafters securely lashed together.

Branches in Samoa described by Andrew Jenson during his tour of 1895

Branches in Samoa described by Andrew Jenson during his tour of 1895

The Samoans are classed among the fairest of all the Polynesian races; and although not so much advanced in the arts and manufactures as some of their neighbors, Samoans surpass them all in many of the characteristics of a race civilization. Captain Erskine, of Pacific navigation fame, remarks that they carry their habits of cleanliness and decency to a higher point than the most fastidious of civilized nations. Their public meetings and discussions are carried on with a dignity and forbearance which Europeans never equal; while even in the heat of war, they have shown themselves amenable to the influences of reason and religion.

In Samoa, commercial interests have acquired great expansion, and the German houses, mostly connected with the Hamburg trade, were in earlier days followed by a well-regulated social culture among the natives. The coconut palm is largely cultivated for exportation, besides coffee and maize. Cotton was formerly one of the staple products. The great importance of the seaport of Apia (Photo of Apia) is due to the fact that it has become the emporium of the produce of all other Pacific Islands, Tahiti and the neighboring group, alone excepted. The scarcity of labor, however, forms a great obstacle to the economical cultivation of the coconut palm in Samoa. To satisfy this want, the natives of the Carolines, the Gilbert, and Marshall Islands have, in recent years, been frequently introduced, these settlers contracting to serve for four or five years. They are readily attracted by the inducements of better nourishment, good dwellings, and kind treatment they receive on the plantations, which are managed after the European fashion. In 1872, the United States assumed the protectorate of the Samoan group, and have established a coaling station at the commodious harbor of Pago Pago on the island of Tutuila; but of late years the German and British influence have become predominant, and the Americans have almost withdrawn from the field.

Ta‘u, the easternmost of the three islands constituting the Manu‘a group, is six miles long by four and a half miles wide; the highest point on the island, which like the neighboring islands is of volcanic formation, is 2,520 feet above sea level. Three and a half miles westward lies Olosega, a small, triangular-shaped island. Immediately west, and only separated from Olosega by a narrow channel less than half a mile in width, is Ofu, another small island about two miles long from east to west. The inhabitants on the three islands named number about 1,800. The Samoan group derives its name from an old line of kings who ruled Manu‘a and who each in succession took the name of Moa. The prefix “Sa” in the Samoan tongue signifies “of” or “belonging to.” For instance, if Matua was the name of a man, Sa-Matua would indicate his family or relations. According to Samoan tradition, the Manu‘a group was the first inhabited of all the islands now included in Samoa. This seems to indicate that the first settlers in Samoa hailed from the east. In that group also the inhabitants have retained the pure or older Samoan language. The same may be said of Savai‘i, while the language has become more or less corrupted on all the other islands.

Tutuila is situated sixty miles nearly due west from the Manu‘a group and is seventeen miles long by six miles wide. The highest point on that island is the mountain peak called Matafao, 2,340 feet above the level of the sea. The inhabitants number about 3,400, who dwell in villages situated on the coast. The Pago Pago Harbor on the south coast of the island is one of the deepest and safest natural harbors in the South Pacific Ocean. The dialect of the inhabitants of Tutuila has lately undergone some changes, among which may be noted the substitution of the letter k for t like the Hawaiians; as for instance tagata (man), as formerly written, is now spelled kagaka. In some cases they have also substituted the n for the g. Thus gamu (mosquito) is now pronounced namu. The g, however, is pronounced as “ng” in “singing.” There are at present six elders from Zion laboring on the island of Tutuila, who are located in pairs at their missionary stations. These are at the village of Pago Pago, situated on the harbor of that name on the south side; Vatia on the opposite side of the island, distant about three miles northeast; and Alao near the east end of the island on the south coast. Immediately south of the east end of Tutuila, and distant from it about one mile, lies the little island of ‘Aunu‘u, where Elder Joseph H. Dean, in opening the Samoan Mission in 1888, first commenced his operations. This island, which is scarcely three miles in circumference, contains only one village.

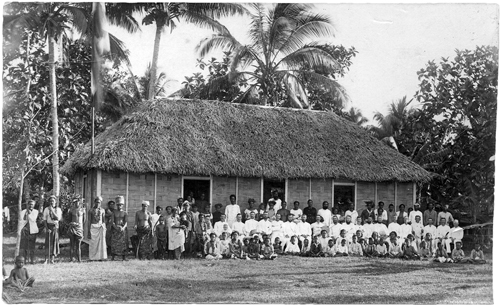

Fagali'i Branch chapel. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Fagali'i Branch chapel. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Upolu, the chief, though not the largest, island of the Samoan group, is separated from Tutuila by a channel thirty-five miles wide. Upolu is forty-four miles long from east to west with an average width of thirteen miles. It contains the principal town of Apia, where nearly the entire foreign population of the group resides. The interior is mountainous and covered with a dense tropical forest and mostly unknown to the present inhabitants. The chief mountain peak, called Talua, is 2,500 feet high and is situated about twenty miles from Apia near the west end of the island. It forms a perfectly round lava cone and crater completely filled with a dense forest. The population of Upolu is about 15,600, or nearly one-half of the entire population of the group, Lanoto‘o is the name of a beautiful freshwater lake situated about ten miles inland from Apia, near the center of the island and close to the tips of the mountains. The water in the lake is nearly sixty feet deep and ranks as a pleasure and health resort for the Europeans. There are numerous streams on the island and a number of beautiful waterfalls, of which the most important is Fuipisia, at which a good-sized mountain stream dashes over a precipice 720 feet high. This fall is near the east end of the island.

At the native village of Fagali‘i, situated on the north coast about two and a half miles east of Apia, are situated the headquarters of the Samoan Mission. The home of the elders at this point consists of a four-room frame building, with an adjoining kitchen all standing in a coconut grove nearly six feet above high watermark, and about six rods from the beach. (Photo of Fagali‘i mission home) The lot on which it stands embraces about half an acre of land on which grow a number of coconut, orange, and mango trees, also one breadfruit tree. Immediately west of the dwelling house stands the meetinghouse, built in a style peculiar to its own, which originated with the first elders on Samoa. The framework consists of imported lumber; the walls or sidings are made of bamboo ingeniously interwoven, and the roof is thatched, the material used being sugarcane leaves. (Photo of Fagali‘i branch chapel) The building is 38x18 by feet and is a fair sample of nine other Latter-day Saint meetinghouses in Samoa. There are four other missionary stations on Upolu, where elders in pairs are permanently located. One of these is at Lalovi, a small native village situated on the extreme west point of Upolu; another is at Si‘umu on the south side of the island across the mountains from Fagali‘i, and distant from that place about twenty miles by trail; and still another station is located in the district of Lepa, near the east end of the island about thirty-five miles from Siumu. At Sale‘a‘aumua, at the extreme east end of the island, a new station has just been opened, and a meetinghouse is now in course of construction there.

Off the east end of Upolu about half a mile lies the little island of Nu‘utele, containing only a few families. It is scarcely two miles in circumference. Immediately southeast is the still-smaller island of Namu‘a, which for twenty-two years has been inhabited by a German family. A short distance north of these two small islands are two uninhabited rock islets. West of Upolu, and separated from that by a channel two miles wide, lies another small inhabited island called Manono, renowned for its brave warriors and conspicuous for the absence of mosquitoes. The island, though only four miles in circumference, contains several villages. About two miles northwest of Manono is the smaller island of Apolima, containing only one village. Both Manono and Apolima are situated in the ten-mile-wide channel which separates the islands of Upolu and Savai‘i.

Savai‘i, the largest and westernmost of all the islands belonging to the Samoan group, is forty-eight miles long from east to west with an average width of twenty-five miles. It has a population of 12,450. Savai‘i has been so recently subject to volcanic action that much of its surface is absolutely sterile. It has many extinct craters, chief among which is the lofty peak of Mua, which rises to a height of about 4,000 feet. Going inland from the district of A‘opo, a village near the north coast, the traveler passes over a tract of country thickly strewn with scoria [3] and ashes, which are evidently of very recent origin, so that the native tales of the last eruption (having taken place only two hundred years ago) are probably correct. In the northwest of the island are also many miles of lava plains, but little altered, and in the east there is an older and larger lava bed partly decomposed and covered with scanty vegetation. In spite of a considerable rainfall, Savai‘i possesses no rivers, owing to the porous nature of the vesicular lava, which offers a large extent of heated surface, so as to evaporate the greater part of the moisture, while the remainder sinks down and appears as springs near the coast. The mountainous interior is thus entirely waterless. In the absence of paths through the interior, the traveling there is very difficult. It is a solitude destitute of animal life, alternately heated by a tropical sun and deluged by fierce rain storms, and affording neither food nor permanent water. But it is generally covered with green tropical foliage. The narrow belt of fertile soil which in places extends between the mountains and the sea is, however, exceedingly beautiful, covered with a luxuriant vegetation and with lofty groves of coconut and fruit trees. Here and in some of the more fertile valleys dwell the population of the island. Savai‘i is noted for its picturesque scenery, remarkable caves, ancient ruins, large coconut plantations, etc. Six Latter-day Saint elders are permanently located on the island at three different missionary stations. One of these is at the village of Sale‘aula, on the east end of the island; another is at Saleaula on the north side of the island and distant about thirty-five miles from the first named. That is the most important and largest branch in the Samoan Mission. The third station or branch is at Fogatuli on the south coast near the west end of the island.

“Jenson’s Travels,” September 28, 1895 [4]

‘Aunu‘u, Samoa

Friday, September 13. One of the brethren who visited Apia reported on his return to Fagali‘i that a Mr. David Kenison [5] was about to sail for the island of Savai‘i on his schooner and would be pleased to take any of the elders with him free of charge, a favor which he has extended to them on many former occasions. As Savai‘i was one of the islands on my traveling programme, Elder Beck and myself decided to avail ourselves of the proffered opportunity, for which purpose we left Fagali‘i late in the afternoon. We spent the evening at the reading room in Apia and the night with our friend Mr. Hellesoe. Our bed consisted of a single mat spread on the hard parlor floor with a small pillow for each of us and a sheet for covering. I shall never forget that unyielding floor. Lie how I would, the boards underneath the single mat would not conform to the shape of my body. How often during that restless night did I wish for more flesh on my bones; the change of diet and climate having deprived me of ten pounds of the scanty supply with which I left home four months ago. I imagine, for obvious reasons, that a man built somewhat after the style of my friend Brother Frances M. Lyman would have slept much more comfortable on the single bed than I did. How I felt like punching myself in the morning when I discovered a soft parlor sofa standing in the room, just long enough for a man of my size to stretch out in. Why didn’t I get up in the night to occupy it? My companion assured me in the morning that he had slept well during the night, but I imagined I saw a mischievous smile on his face when he said so. This was my introduction to a Samoan bed, though the natives sleep on their gravel or pebble stone floors instead of lumber.

Saturday, September 14. Quite early in the morning we boarded Mr. Kenison’s schooner, a fine little craft of ten tons capacity and with a deck forty-five feet long. It is generally manned by Mr. Kenison and his son Thomas when there is no Mormon elder onboard to assist. At 9:00 a.m., anchor was lifted, and I started out on the first schooner voyage of my life. The wind blowing gently from the north, we had to tack out of the Apia Bay or harbor; but at 10:30 a.m., we found ourselves outside the reef and were able to steer straight for Savai‘i, the mountainous heights of which were seen in the west. For some time our progress was very slow owing to a calm, but after “Tommy” and a native lad had whistled repeatedly for wind, a pleasant breeze arose from the east which at once filled the sails and sent us toward our point of destination at a good speed. While Elder Beck tried his hand at the rudder, Captain Kenison and myself talked Bible, religion, and history until the good captain lost his reckoning and gave Tommy the wrong word of command, which resulted in running the schooner aground on the rocks just as we had safely crossed the dangerous reef at sundown to the smooth waters inside. And there she lay till the tide arose and lifted her off about midnight. But in the meantime, Elder Beck rowed himself and me on shore in the little boat carried by the schooner. The distance was about a mile, and we landed at Mr. Kenison’s pier at Salelavalu, near which one of our meetinghouses also stands. Seeing that the two elders stationed here were at home, I conceived of the idea of playing smart by leaving Elder Beck behind and introducing myself to the brethren as a stranger. But I either played my part clumsily or my assumed looks and actions could not hide my true character as a Mormon elder, for as soon as I appeared in the door, Elder Lewis B. Burnham, though he had not seen me before, greeted me quite naturally with, “Come in, Brother Jenson.” So I went in, and Brother Beck followed; and we spent a pleasant evening with the brethren, after feasting with them on breadfruit and fish. It was the first time in my life that I partook of breadfruit. I was hungry and ate it with such relish that I called for breadfruit again at the next meal. Elder Lewis B. Burnham presides over the missionary work on the island of Savai‘i and also has charge of the station at Salelavalu, assisted by his cousin, Elder George S. Burnham. Our schooner voyage during the day represented a distance of about thirty-five miles.

Sunday, September 15. Meeting was held in the meetinghouse at Salelavalu, commencing at 8:00 a.m. Owing to the stormy weather—the rain descending in torrents—only about a dozen people attended. Elder Beck and I were the speakers. After the meeting we walked over to the residence of Brother Fred Kenison, the only white member of the Church at Salelavalu, and partook of a splendid meal prepared by Brother Kenison’s native wife. At 1:45 p.m., we four elders boarded a little boat manned by Fred Kenison and his younger brother George, and sailed along the coast five miles in a northerly direction to the residence of Brother David Kenison Jr. at Tuasivi Point. The rain descended unceasingly while on the water, but the boat sped on at a rapid rate, the wind blowing from the right corner; and in about three-fourths of an hour from the time of starting we landed at Tuasivi Point, happy and cheerful, though drenched to the skin, and received a warm welcome by Brother Kenison and his native wife, whose kind hospitality we soon shared. Commencing at 4:00 p.m., we held a good little meeting at Brother Kenison’s house, quite a number of natives attended notwithstanding the bad weather. Brother Beck and myself were again the speakers. And now came a request from a prominent chief residing in the neighboring native village for us to hold a meeting in his house in the evening. The chief’s name was Lauate and the village Fogapoa. Of course the request was compiled with, and wending our way thither in the darkness we found on our arrival nearly one hundred people assembled, who listened very attentively to a few remarks, interpreted by Brother Beck, from myself, and then a powerful gospel discourse from Elder Beck. Quite a number of chiefs, some from a distance, were present, who after the meeting expressed their friendship by throwing at our feet a large piece of ava, which was grated and made into a drink that was partaken of by all the white people present and the chiefs. The short, customary speeches were made and a good feeling prevailed. We also showed the chiefs some Church relics and album views which I brought along and left at a late hour to obtain a good night’s rest in the house of Brother Kenison.

Monday, September 16. Elder Beck and I were bound for another missionary station, about twenty-five miles away, and in order to shorten our walk it was decided that we be taken a few miles by boat, as our course lay along the coast. Consequently we sailed from Tuasivi Point at 8:00 a.m., intending to go by boat about seven miles; but after sailing a little more than half that distance, our boat ran aground, the tide being out, so we were forced to land at the village of Lano, where Elder Beck and myself set out on our long tramp, the other brethren returning with the boat. Each of us packed a little satchel containing a few books and a few indispensible articles of light clothing. After walking about three miles through a number of villages, we reached the edge of the “bush,” through which the distance is about twelve miles, and there are no human habitations of any description. Just as we entered that lonely tract, a rainstorm opened its fury upon us, and Elder Beck suggested that we strip off all unnecessary clothing in order to keep it dry and put it on again after the storm. The suggestion, though a queer one for a man who had been used to put on an extra coat or two in order to keep dry in a rainstorm, was acted upon; and I am sure our friends in Utah would have paid something to have seen us in our traveling costume. And then we were richly attired compared to the native pedestrians whom we met on the road. They were absolutely nude, walking with their only article of clothing, vale vale, in their hands, but on meeting us, they hurriedly wrapped the article mentioned around them only to take it off again as soon as they had passed. I pitied their bare feet; but they appeared to be tougher than my shoes, which gave out on me through their rough usage on the hard and sharp-edged volcanic rock that abound all the way through the bush. In fact, the whole tract of country is nothing but an old lava bed or a lava flow, commencing in the mountains far inland, where some terrible eruptions took place in past ages, and extending clear to the sea. Subsequently, trees and shrubs took root in the cracks of the cooled lava, and hence the present bush. The path leading through it is narrow and winding. Horseback travel is impossible, and a footman has enough to do in places to scramble over the big rocks and fallen timber. Notwithstanding the rain, it was not miry. One could always find a rock to place his foot upon; and I believe that in walking the twelve miles we never took a step without either putting a foot upon a rock or upon roots or fallen trees. There is no soil here either to make mire or dust. On the long, dreary walk we only emerged from the bush once, and that was to an opening on the rock-bound seacoast where the waves beat themselves to foam and spray against the perpendicular walls constituting the coast. No sandy beach at this point to blend sea and land gently together.

Well, we got through at last, and then we found ourselves in a Catholic village, where we entered a native house and sat down to rest, which is the custom of the country. An old woman placed food and water before us, of which we partook, while eating the one-half of a loaf of bread which we had carried with us that far. For the other half we induced a boy to climb a tree and get us some young coconuts, which we then opened and drank the milk. As we were very thirsty, this tasted very good indeed. I am sure the veterans of Salt Lake City don’t drink lemonade on Old Folks’ Day with greater relish than we drank our coconut milk in the village of Lealatele. After resting a little, we tackled the last six miles of our journey. It led through a number of villages; at length we reached our destination and surprised Elders Christian Jensen Jr. and James C. Knudsen at Saleaula by suddenly appearing in their midst as they were earnestly engaged in teaching a class of boys and girls some of the rudiments of an English education in the meetinghouse. The meeting was a happy one, and our brethren gave us a hearty welcome, as also the native Saints who dropped in one by one and a few at the time to see us and greet us with their usual “talofa.” Elder Beck and I had already walked twenty-one miles over the roughest road imaginable during the day; but in order to convince ourselves and our friends that we were not tired, we walked one and a half miles farther to a small river where we took a refreshing bath. When we had retraced our steps to the meetinghouse, I had to admit that I was tired, very tired, and needed rest. I had waited for Brother Beck to say that first, but he wouldn’t or didn’t. I hated to give up first. The natives now brought us some splendid food which was spread for us on the floor; and we ate till we were filled and enjoyed the meal immensely. Next on the program was an evening meeting. Nearly all the people of the village gathered, about 150 in number. The little house was filled to overflowing, and many were unable to gain admittance. My sermon was ably translated by Elder Beck, and we had a splendid time. After the meeting, six native girls entertained us with an exhibition of their peculiar “siva” dance and some singing, followed by the same number of boys. To me, who saw and heard this for the first time, it was very interesting, and many of their movements were truly graceful.

Sale‘aula is one of the principal missionary stations in the Samoan Mission. Among the members of the Church here, there are a number of leading and influential chiefs; the meetings and Sunday Schools are well attended, and also the day school. Strenuous efforts are being made by the elders laboring here to teach the young the gospel and keep them in the paths of virtue. In order to guard and protect them, about a dozen half-grown boys sleep with the brethren in the meetinghouse. After conversing till a late hour, we retired to forget our long walk and to dream of our loved ones in Zion.

Tuesday, September 17. This day was pleasantly spent at Saleaula. We wrote and culled history; conversed with natives; sang English, Samoan, and Danish hymns; talked of things past, present, and the good times to come; ate native food; and were happy. It was a rather strange coincidence that four direct descendants of the old Scandinavian “Vikings” should by accident be brought together on one of the South Sea Islands, so far away from the land of their forefathers. But so it was, and while visiting a very interesting cave or underground passage over half a mile long situated in the bush immediately back of the village, we raised our voices and caused the rocks to echo our attempt at singing “Underlige Aftenlufte,” etc., or “Ochlenchleegers Hjemve” for the first time, at least at that particular place, in the bowels of the earth. In the evening we held another good and well-attended meeting at the meetinghouse, Elder Beck being the principal speaker.

Wednesday, September 18. At 7:30 a.m., Elder Beck and I gave the parting hand to Elders Jensen and Knudsen and left Saleaula on our return trip. We stopped to eat breadfruit and drink cocoa and milk in Lealatele; entered the bush at 9:00 a.m.; got through at 12:30 p.m.; met Elder Lewis B. Burnham at Puapua, the first native village reached after getting through the bush; and then walked with him three miles farther to a point where the boat sent to meet us was anchored. There we also met Elder George S. Burnham and our young friend George Kenison, who were in charge of the boat. After refreshing ourselves by drinking some coconut milk, we boarded the little craft and rowed about four miles to Tuasivi Point, where we again partook of the hospitality of Brother David Kenison Jr. and wife; and at 5:00 p.m., we continued our travel by boat, going five miles to Salelavalu, where the native Saints, under the direction of Brother Fred Kenison, prepared a feast for us. Thirty-five people sat down upon the meetinghouse floor to eat, with the elders at the head of the table. Nearly every variety of native food was provided, most of which was very good and palatable. After the feast we held a meeting according to previous appointment, at which I spoke first and was followed by Elder Beck.

Thursday, September 19. The day was stormy, and at times the rains descended as it only can in the tropics. At 4:00 p.m., Elder Beck and your correspondent, accompanied by the two elders, Burnham and Brother Fred Kenison, boarded a boat belonging to Mr. David Kenison and pulled out for Upolu. The wind being contrary, we had to row all the way, and that, too, while the rain was liberally pouring down upon our devoted heads. In order to shorten the distance, we ventured through a narrow and somewhat dangerous passage over the reef into the open ocean. We then pulled straight for the little rocky island, Apolima, intending to land there and spend the night; but on nearing the island, the breakers were seen to roll very high at or near the only landing place, and the darkness of the night also having settled down upon us, Brother Kenison considered it unsafe to attempt to land. Consequently, we changed our course and pulled for the island of Manono, lying about two miles further to the east. Having reached the west coast of that island, we were told that the village in which we ought to spend the night was situated on the opposite side. Hence the rowers, tired as they were, continued their labors, paddling the boat around the north side of the island. At length, tired and hungry, we landed at the village of Saleataua, situated at the extreme southeastern point of the island. We had come a distance of about twelve miles. After securing our boat, we entered a native house, where a family belonging to the Church lived. Here we ate our own food for supper, after which we were sent to a neighbor’s house to sleep. There we stretched ourselves on the mats provided for us and used our shoes and satchels for pillows. The master of the house being told about my special mission showed me additional attention by throwing me a white sheet to cover myself with. The other brethren slept without covering.

Friday, September 20. We arose at daylight, prayed, and took a morning promenade around the island. By walking at an ordinary gait, it took us one hour and twenty-five minutes. There are nine small villages on the island, and we passed through all of them. We were offered no breakfast by the natives, though we had divided with them the evening before. At 8:00 a.m. we continued our voyage by rowing two miles over to Lalovi, one of our missionary stations situated on the west end of Upolu. Here we met Elders Joseph A. Rasband and William A. Moody, who hold the missionary fort at this point, and I started to work at once to obtain the needed historical information and to give the usual instructions in regard to record keeping. By and by the natives brought us a splendid meal consisting of breadfruit, shark, chicken, devilfish, and another kind of fish called matu by the Samoans. At 2:00 p.m., the two Elders Burnham and Fred Kenison started by boat on their return trip to Savai‘i, and we who remained held a good little meeting with the Saints at Lalovi. Brother Beck and I were the speakers. Towards evening Elders Beck and Moody started on foot for Fagali‘i, leaving me to follow alone on horseback the next day.

Saturday, September 21. Elder Rasband and myself arose at daylight and walked to the neighbor who had promised us the use of his horse. After some difficulty the animals was found, caught, saddled up, and mounted; but the brute insisted on going backward instead of forward, and cut up quite a number of capers when he found that we wanted him to leave his master’s premises. It was not till Elder Rasband had belabored him somewhat roughly with a “fraction” of a tall tree that he could be induced to start for Apia. The ride proved more tiresome to me than the walk would have been, but I got there at last. Counting the numerous villages that I passed through; getting off and on the horse to climb fences; holding onto my heavy satchel, which I had failed to fasten to the saddle; and endeavoring to show the animal that carried me white man’s manners, kept me busy as I pursued my lonely ride along the narrow, winding path, leading alternately through village and bush. I also stopped in a native house to get lunch and obtained a coconut to drink from a native boy who could talk a little English. At 2:30 p.m., I arrived at Apia, about thirty miles from Lalovi, and after partaking of refreshments at Mr. Hellesoe’s, I continued to Fagali‘i, where I found that Elders Beck and Moody had preceded me a few hours. After this trip to Savai‘i, embracing it as did quite a variety of experiences, I consider myself properly initiated into Samoan missionary life and am perhaps better prepared to write the history of the mission than I was before.

“Jenson’s Travels,” October 3, 1895 [6]

Fagali‘i, Samoa

Sunday, September 22. I attended two meetings at Fagali‘i, one early in the morning and one in the afternoon. Only a few natives attended, the branch of the Church at the mission headquarters not being large; nor are the few members here very lively as a rule.

Monday, September 23. At 3:00 p.m. Elder John W. Beck and myself left Fagali‘i to make a trip to the island of Tutuila. Elder Kippen took us in the mission cart to Apia, where we boarded a small schooner christened Tutuila belonging to Thomas Meredith, an Apia merchant. The little craft was named by a German who could boast of a Samoan wife of no ordinary character and a slim, tall, very long-legged native of Savage Island who became all attention when his master called out “Jim,” which he did at very short intervals indeed. At 5:00 p.m. the schooner loaded with ballast and two Mormon elders, besides captain and “Jim,” some boiled bananas, and other necessaries, left her moorings in the Apia Harbor; and after beating against the wind for some time, we succeeded in reaching the open ocean, where the waves rolled high and the brisk trade wind threatened to blow us to Savai‘i instead of helping us on toward Tutuila in the opposite direction. O these blessed trade winds in the South Seas! Everything must conform to them. Hence a trip to Tutuila from Apia generally means beating against southeast wind for the space of three days, while the return trip is often accomplished in a few hours. Though the little vessel was tossed to and fro upon the face of the great waters while doing her best to obey the rudder, which kept her close up against the wind, Elder Beck and I stood the motion well. We only fed the fishes once or twice, and even this we did very quietly. We did not wish to give offence to each other, nor did we wish to lose the reputation for seamanship which we were so anxious to establish more fully; but our pale faces and somewhat soiled clothing told the story the next morning. We were only a short distance from Apia when the sun went down, and the darkness closed in on the lonely craft so thick that even the outlines of the nearest mountains of Upolu could not be discerned. The captain offered us a place in his little cabin to rest our heads during the night, but the smell from below frightened us from the first; so we chose to take our chances on deck. Elder Beck stretched himself on one side of the main hatchway, while I crawled into the little boat which was carried onboard, and it was not till the astonished captain launched it in the Pago Pago Harbor three days later that the discovery was made that the weight of my body had very near parted the bottom from the rest of the boat, which filled with water so fast that Elder Beck and myself nearly reached Tutuila swimming.

Tuesday, September 24. The early morning found us beating against a very gentle breeze off Fagatogo Bay, about fifteen miles from Apia; and there we remained all day, enjoying the “sweet pleasures” of a genuine Pacific calm while exposed to the burning rays of a tropical sun shining through a cloudless sky. In vain did we wish for more wind, even if it would blow from the wrong point of the compass; for with a brisk wind some little progress can always be made by beating against it; but a calm leaves sailing craft absolutely helpless and drifting. Half- sick and sleepy through not having rested the night before, we were unable to read, talk, or sing with any sense all that long, weary day. The heat nearly stupefied us and deprived us of all ambition. One suggested a swim in the ocean, but “Jim” told us he had great respects for the sharks which abounded here; he suggested, however, that we could do as we pleased. But as I still remembered very distinctly the peculiar shape of the teeth and shark’s jaw which I had seen at Nukualofa, Tonga, I feel no particular desire to expose my body to the tender mercies of such another jaw in the employ of a real, live shark, nor did Brother Beck; so we remained onboard; and I only dipped my feet and head in the water alternately. “But, man,” says the captain, “don’t you know that to wet your head thus with salt water will make the skin sore and produce severe headache?” No, I did not know then, but I soon found out. Though the captain’s stories were not all true or consistent, he seemed in this instance to know what he was talking about; I have never dipped my head in salt water since. Poor “Jim,” how could he help the calm! But the captain was cross and swore and cursed in German, Samoan, and broken English because the wind would not blow; and as “Jim” was his only servant he was made the hapless victim on which the commander wended his spleen. “Jim” did not know the English name for all the ropes belonging to the schooner, nor did he move with that rapidity which is characteristic of the genuine and experienced sailor. And that made the captain angry, especially when the order was “‘bout ship,” and all the sails with their ropes and other belongings were to “change sides” at once. And, besides, “Jim” was somewhat top heavy, as compared with his lower extremities, and he had to steady himself so as not to spill himself in the sea when the schooner rolled from one side to another.

In the evening the captain dropped a hook and line and soon caught a large fish of the Sapatu family, which served a good purpose at meals the following day. About midnight, when the wind freshened up a little from the north, we succeeded at last in clearing the east end of the island of Upolu and the two small islets lying off the east point, about thirty miles from Apia, and we then headed for Tutuila thirty-five miles away.

Wednesday, September 25. As the sun rose, the outlines of Tutuila could plainly be seen toward the eastern horizon. We breakfasted on fish and boiled bananas and then spent another day on the ocean in perfect inactivity. The wind blew very gently indeed, and only a little breeze called by the captain a “Yankee slant” moved us a little toward the point of our destination. My face and neck, being exposed to the heat, pained me all day, and the time passed wearily away.

Thursday, September 26. A breeze which had sprung up during the latter part of the night had sped us somewhat onward so that the still hours of morning found us beating against the trade wind a short distance southward from the extreme western point of Tutuila. The island is mountainous, the formation volcanic, most of the coast rockbound, and the scenery grand and imposing. To watch the waves spend their fury upon the rocks and see the spray shoot up high on the face of the perpendicular cliffs which constituted the coast was very interesting; and our condition onboard was made more tolerable by the refreshing wind, which, though blowing from a wrong point of the compass to suit our course, enabled us to make a little progress by beating against it. After tacking a number of times, we succeeded in rounding a rocky headland, of[f] which stands a needle-shaped rock arising from the bottom of the ocean which is called “the lonely fisherman” by navigators. Thence we steered straight for the mouth of the Pago Pago Harbor in all Samoa; and at 1:00 p.m. we anchored safely off the village of Fagatogo, one of the native towns situated on the harbor just named, after coming a distance of seventy-five miles from Apia; but I am sure 150 miles would hardly cover the mileage for us who came beating against the wind much of the distance. From Fagatogo Elder Beck and I walked a mile around the head of the harbor to the village of Pago Pago, where there is a Latter-day Saint missionary station. Here our arrival surprised Elders D. Foster Cluff and Abinadi Olsen, two of our Utah elders laboring in Tutuila, for they had not been apprised of our intended visit at this particular time. We now spent a pleasant afternoon with our brethren; partook of a good meal prepared by the native Saints, who also gave us a hearty welcome; held an interesting meeting in the evening, at which Elder Beck and I were the speakers; took a refreshing bath in the harbor after nightfall; drank awa with the village chiefs, some of whom were members of the Church; culled history from the records till a late hour; and enjoyed a short night’s rest.

Friday, September 27. According to arrangements made in council with the native chiefs the evening previous, we arose very early intending to start for the island of Manu‘a. Following a faithful native brother who led us in the darkness around the head of the harbor, we came to a point where one of the village boats was lying in a shed. Five natives, all members of the Church except one, were called out by our friend, Elder Viali. We Utah elders (four in number) helped them to launch the boat and gather the tackling; and at 7:00 a.m. we sailed from Pago Pago, the natives and elders rowing three miles to the mouth of the harbor, where sails were set, and the beautiful boat—for such it was after the sails were spread—sped quickly over the water out into the open ocean, beating heavily, however, against a pretty strong southeast wind. We had an interesting voyage, but Elders Cluff and Olsen, who lacked the three days’ training that Elder Beck and I had undergone, suffered considerable with seasickness. The five natives who treated us to this genuine Samoan voyage were Teo, Viale, Fiatele, Suega, and Tauvaga, the latter being a nonmember but a relative of Teo. After several hours’ sailing we at length reached the one-mile-wide strait which separates the little island ‘Aunu‘u from the largest island of Tutuila; and after taking in the sails, the natives, assisted by the elders, rowed into the north shore of ‘Aunu‘u, passing safely through the breakers, and we landed on the sandy beach in front of the only village on the island, pulling the boat up after us. We were kindly received by the head chief, whose name is Lemafa. He is one of the few members of the Church left of the large branch which was organized here by Elder Joseph H. Dean in 1888. Nearly all have turned away and resumed their former mode of worship. After drinking coconut milk and partaking of a sample native meal in regular native style, we visited Manoa, [7] one of the two Hawaiian elders who first introduced the true gospel in Samoa about thirty-three years ago. From him I obtained some valuable and interesting data, which will be used in the compilation of the mission history. Elder Manoa kept a journal during his missionary days and could give accurate information about his labors and those of his fellow laborer, who now rests beneath the sod of Tutuila. In the evening we held a good meeting in one of the largest houses in the village; about seventy-five of the two hundred people that constitute the population of the village and island attended, and Elder Beck and I were the speakers. The natives seemed to revive in their spirits while we addressed them, and it may be possible for the elders who labor on Tutuila and who visit ‘Aunu‘u once in a while to recognize the branch here. After the meeting, the usual greeting, and awa drinking, tasting only on our part was gone through with according to Samoan custom; and we enjoyed a good night’s rest in the same house where we held the meeting, being protected against the mosquitoes by the indispensable netting.

Saturday, September 28. We arose early; took leave of our native friends of ‘Aunu‘u, some of whom made us small presents; launched our boat; boarded it; rowed it safely through the breakers; set sail; and headed for the Pago Pago Harbor eight miles away at 7:00 a.m. The wind was good and brisk, and the sea rolled high; but the voyage proved very interesting. Our little craft, which bore all the canvass it possibly could stand, literally flew along the water, cutting through the waves and sending the spray at times half way up to the top of the mast and also over crew and passengers. But we cared not! We were in the tropics. If we did get wet, we would not freeze nor catch cold if we took care to change our clothing before sleeping in them. It took us just one hour by my American watch to sail from ‘Aunu‘u to the mouth of the Pago Pago Harbor. To sail the same distance the day before required five long hours and a fraction. Just as we reached the mouth of the harbor, we spied our old friend Captain Brandt, with his wife and “Jim” and some other passengers, coming out with his schooner on his return to Apia. He was to have left the evening before, and we were to join him at Leone, on the west end of the island, but as the weather was rough in the evening he had concluded to wait till morning. This was providential for us, as we thereby escaped a long tramp on foot over the mountains of Tutuila. Our native friends, instead of taking in sails and “laying to” at once, could not withstand the temptation of trying the schooner in a race, in which they beat as they expected, their craft necessarily being a swifter sailer than the heavy-built schooner. After considerable labor and some little danger, the two vessels came down together, and we sprang onboard the schooner at an opportune moment when the waves lifted us to a proper elevation; and after bidding Elders Cluff and Olsen and our native Saints and friends goodbye, we continued our voyage on the schooner from the mouth of Pago Pago Harbor. In two hours and a half we sailed twelve miles with a good wind and over a rough sea to Leone, off which town we cast anchor at 11:00 a.m. As the schooner was to take in a cargo of copra at this place, all hands landed, and Elder Beck and myself put up with Brother James Mackie, a European member of the Church. He and his native wife made us very welcome and treated us with much hospitality and kindness. We spent the day and evening in pleasant conversation and in taking a walk through the village, which is the largest in Tutuila. It is beautifully situated on a bay and looks like a little city, when one approaches it from the seaside. The houses scattered along the beach and the fine-steepled Catholic church in the center of the village, presents a most enhancing picture. The church can be seen a long ways off at sea and serves the navigators as a conspicuous mark. The place reminded me very much of the little city of Saby, situated on the coast of the Kattegat, in old Denmark, where I spent some of my boyhood days.

Contrary to our expectations we were obliged to spend two nights at Leone, as the natives who were to put the cargo onboard the schooner flatly refused to work till Monday. There was a marriage feast going on in an adjoining village to which nearly all the young people of the town were invited; and the Samoans are so very much more fond of feasting, eating, and drinking than work that our captain and the merchants who were interested in the cargo pleaded in vain for having the schooner loaded on the Saturday.

Sunday, September 29. As we unexpectedly had to spend a Sunday in Leone, we concluded to hold a meeting. But through the influence of the London Mission priest who resides here, we were unable to obtain the large native building which might properly be termed the town hall and in which chiefs meet together for council. We were thus obliged to hold our meeting in Brother Mackie’s native house, where only about twenty people met with us. In the afternoon I attended Catholic services in the church already mentioned and also in the London Mission church, where the native minister endeavored to influence his flock against the “Mormons,” who were in the village just then. Of course he got his inspiration from his white chief. We spent another pleasant evening at Brother Mackie’s house, Edward Hahn, a German brother, who also has a Samoan wife, being among those present. Brothers Mackie and Hahn and one native are the only members of the Church at Leone; but an attempt will perhaps now be made to open a station here.

building which might properly be termed the town hall and in which chiefs meet together for council. We were thus obliged to hold our meeting in Brother Mackie’s native house, where only about twenty people met with us. In the afternoon I attended Catholic services in the church already mentioned and also in the London Mission church, where the native minister endeavored to influence his flock against the “Mormons,” who were in the village just then. Of course he got his inspiration from his white chief. We spent another pleasant evening at Brother Mackie’s house, Edward Hahn, a German brother, who also has a Samoan wife, being among those present. Brothers Mackie and Hahn and one native are the only members of the Church at Leone; but an attempt will perhaps now be made to open a station here.

Monday, September 30. At 3:00 p.m., Elder Beck and I boarded the schooner, after taking an affectionate leave of our friends in Leone, and set sail for Apia. Before leaving, Brother Mackie made me a present of a fine Samoan mat to take home. We spent the night crossing the thirty-five-mile-wide strait that separates the islands of Upolu and Tutuila. The captain’s wife and two other natives were the other passengers onboard.

Tuesday, October 1. Having spent an uncomfortable night rolling to and fro on the deck of the schooner, the morning hour found us sailing off the north coast of Upolu, and as the wind soon afterwards died out, or nearly so, it took us all forenoon to get to Apia. But we got there at last; and we felt greatly relieved in body and mind when the anchor was dropped in the Apia Harbor precisely at 12:00 noon. Our trip to Tutuila had consumed eight days, during which we had sailed about 250 miles (including beating distance); and we had been successful in obtaining historical information, though we missed some of the elders from Zion whom we had expected to see.

On our landing at Apia, we learned that the steamer Taviuni, with which I should have taken passage to New Zealand, had come and gone during our absence, and that for a month to come no other Union Steam Ship Company’s vessel would leave for Auckland. This was somewhat disappointing to me, but I decided to secure a passage on the next mail steamer from America, which was expected in a day or two. After taking lunch with our friend, Mr. Hellesoe, Elder Beck and I walked through the bush, following a winding trail, to Fagali‘i, where we arrived at 3:00 p.m. and found all well at headquarters, Elders Sears, Kippen and Lemon holding fort. The latter, however, was there on a visit from his station on the east end of Upolu, where the brethren are busily engaged in building a new meetinghouse.

“Jenson’s Travels,” October 15, 1895 [8]

Auckland, New Zealand

Wednesday, October 2. I spent the day at Fagali‘i, Samoa, busily engaged in historical labors, assisted by Elder William G. Sears.

Thursday, October 3. We spent the forenoon writing at Fagali‘i, and in the afternoon Elders Beck, Sears, Kippen, and myself went to Apia and sat down in a photographer’s gallery while a picture of our dear selves were being taken. In company with Elder Beck, I also visited Malietoa, the king of Samoa, (Photo of Malietoa) who lives in a neat little frame cottage standing near the beach immediately west of Apia. He is an ordinary-looking man possessing only average intelligence, and he appears to be very guarded and slow in his conversation. His clothing consisted of a plain shirt and the ordinary lava lava (breechcloth) worn by the natives. He could not tell us how old he was; but we noticed that his hair was quite grey. His best room, in which he receives visitors, is kept tidy and neat. The floor is covered with fine mats and the walls ornamented with pictures; among them we noticed a good portrait of Queen Victoria, of England, and a ditto of Emperor Wilhelm I of Germany. The king was very reluctant in expressing his opinion in regard to “Mormonism,” but he showed us a neat copy of the large-type edition of the Book of Mormon in English, which he received some years ago as a present from the First Presidency in Zion.

On our return to Fagali‘i we called on Mr. Mulliner, the American consul to Samoa, who was about to return to his country. He had no great love for neither Samoa nor its people. I spent the remainder of the day and evening at Fagali‘i finishing up my historical notes, packing a small box to send home, and conversing with the brethren. About midnight we sighted the mail steamer Monowai steaming into Apia Harbor. (Image of Monowai)

Friday, October 4. I arose at daylight and roused up the other elders. We had early prayer and breakfast, after which Elder John W. Beck and myself boarded a little boat which belonged to a European brother (Christopher Pike) who together with a Mr. Fischer, both from Tutuila, had stopped at the mission house overnight. Exposed to the drenching rain against which our umbrellas afforded us but little protection, we rowed three miles to the Apia Harbor, where the steamship Monowai was anchored; and after securing passage and berth I landed once more in Apia to finish up my labors in connection with Elder Beck, of whom I took leave at 12:00 noon to be rowed a quarter of a mile (while exposed to another drenching rain) to the Monowai, which about an hour later lifted her anchor and steamed off for New Zealand. We rounded the east end of Upolu at 3:00 p.m., and before nightfall we had enjoyed the last glimpse of the Upolu Mountains far away to the north. Seasickness has peculiar freaks, at least so far as its dealings with me are concerned. After having been jotted, pitched, and tossed about onboard a little schooner for several days without hardly getting seasick, I had no anticipation of being made the victim of that most unpleasant malady onboard a steady-going ocean steamer in fair weather. But fate would have it otherwise; and after this, whenever I start on a voyage I shall frankly admit that I don’t know whether I am to get seasick or not.

Saturday, October 5. The sea was rough, and the wind was blowing hard. Seasickness was king and kept nearly all the passengers in humble submission below.

Sunday, October 6. I had an interesting morning conversation with the commander of the ship, Captain Michael Carey, who accepted with thanks my offer to give a lecture in the evening in the ship’s social hall. At 8:00 p.m., as duly announced by a neat little notice written and posted up by the purser, most of the saloon passengers and quite a number also from the forecabin, as well as some of the officers and men belonging to the ship, assembled in the beautiful hall and listened very attentively while I addressed them over an hour on “Utah and her people,” taking particular pains to tell them what the Mormons believed in. In answer to earnest prayer, the Lord strengthened His servant, who spoke with considerable freedom and plainness. After I was through, one of my fellow passengers who expressed himself as being much pleased with what he had heard made a neat little speech, in which he in his way bore testimony to the truth of what I had said; and a hearty vote of thanks was next in order. A Swedish clergyman (Methodist), who was making a tour around the world and who had never heard a Mormon elder speak before, was very much surprised to learn that, notwithstanding all he had heard to the contrary, the Mormons believed in Christ and the Bible and were actually Christians. He insisted upon treating me to something to drink, as he believed me dry after speaking so long. I accepted of lemonade. During the day I had several conversations with another Swede, Olson by name, who was returning to New Zealand with his family, from a visit to his relatives in Box Elder County, Utah. He did not find his relatives to be as good as he had expected. If he had, he would have remained in Utah. In the evening we crossed the Tropic of Capricorn (latitude 23º30´ S) into the South Temperate Zone.

Monday, October 7. I had a number of interesting conversations with officers and passengers on Utah and religion, my lecture the previous evening having created a desire within many to learn more. At noon the daily bulletin read, latitude 27º7´ S; longitude 178º1´ W; 902 miles from Apia, and 688 miles to Auckland. I spent much of the day and evening writing in the saloon and retired at a late hour. When I arose the next morning, I was informed by Captain Carey that Wednesday, October 9, had dawned upon this part of the world. What had become of Tuesday, October 8? At 4:00 a.m. that morning we had crossed the imaginary line known as the 180th meridian. That explained all. I had crossed that line twice before—first between Hawaii and Fiji, which robbed me of a Sunday, and second between Tonga and Samoa, which gave me two Wednesdays in one week. The day was quite cold and windy.

Thursday, October 10. The cold and cloudy day made my extra underclothing, which I had not worn during my sojourn in the tropics, feel quite comfortable, when I put it on this morning. At 11:00 a.m., land was seen ahead with the naked eye, and those of the passengers who had never been in New Zealand before were informed by those who had that this particular land was the mountainous island known as the “Great Barrier,” which is distant from Auckland about sixty miles. Soon after this a heavy gale struck the ship, which made her rigging groan and crackle and the hull shake and tremble. One of the furled sails became undone and flapped with great violence against the cross spar and mast. One of the most experienced sailors was sent up to fasten it, and after much exertion he succeeded in doing so, but it looked very dangerous; and many of the passengers who watched him trembled with fear lest he should be knocked overboard. At noon we were 1,531 miles from Apia and fifty-nine miles from Auckland. As we proceeded, we were shown the spot off the rocky coast of the Great Barrier where the steamer Wairarapa was wrecked a few months ago, causing the loss of several hundred lives. Near this place (also off the Great Barrier), a number of strange-looking rocks are seen rising out of the ocean independent of each other, some of them attaining a height of nearly a hundred feet—perhaps more. It was very interesting to watch the breakers spend their fury upon those majestic rocks which are known to navigators as “The Needles.” At 1:00 p.m., we were sailing close to a mountainous island on our right, and soon afterwards the shores of the mainland or the North Island of New Zealand were visible. In the meantime, the wind continued to blow hard, and though somewhat shielded by land, the good Monowai sped on her course in a somewhat shaky manner, which made some of the passengers shaky, too. At 4:30 p.m., we entered the beautiful harbor of Auckland, and at 6:00 p.m., we lay alongside of the wharf. In looking over the big crowd of people which had gathered on the wharf to watch the steamer come in and to meet friends and relatives, I noticed a man with a long, sandy beard who distinguished himself from all the rest of that smiling and pleasant countenance characteristic of a true Mormon elder. Nor was I mistaken, for he turned out to be Elder William Gardner, president of the Australasian Mission, who, together with Elders John Johnson of Elsinore and Thomas S. Browning, of Ogden, Utah, had come down to meet me, as they had reason to expect me in by the Monowai. They had looked for my arrival at an earlier date, my visits to the other islands having occupied more time than at first anticipated. The meeting with these elders was very pleasant to me, and so was also the mail from home which awaited me here. For three months I had not heard a word from my family or anyone else in Zion, my route of travel having been such that no letters could reach me.

The Australasian Mission has no permanent headquarters, though Auckland is understood to enjoy that distinction. But the president spends nearly his entire time traveling in the different districts, paying particular attention to the Maori part of the mission, and when at Auckland rooms with Elders Johnson and Browning, who rent a small apartment of an old lady on Grey Street, No. 145, and board themselves. These two brethren have been appointed to labor in Auckland and vicinity, where they are endeavoring to raise up a branch of the Church. I am now making my temporary home with these elders also, while I peruse the records of the mission; afterwards I expect to visit the different districts, constituting the New Zealand part of the Australasian Mission.

Notes

[1] “Jenson’s Travels,” Deseret Weekly News, January 11, 1896.

[2] “Jenson’s Travels,” Deseret Weekly News, January 11, 1896.

[3] A type of material ejected from the volcanoes of Savai‘i.

[4] “Jenson’s Travels,” Deseret Weekly News, January 18, 1896.

[5] Captain Kenison moved to Samoa about 1865 from New Zealand and had a large family. Some of his children had already joined the Church. Captain Kenison was baptized in 1898.

[6] “Jenson’s Travels,” Deseret Weekly News, February 1, 1896.

[7] In 1862, Walter Murray Gibson sent Hawaiian elders Kimo Pelio and Samuela Manoa as missionaries from Hawaii to Samoa. They made the little island of ‘Aunu‘u their headquarters and baptized upwards of two hundred members. The elders sent a few letters back to Hawaii for help, but no help came until Joseph Dean and his family were assigned to Samoa from the Hawaiian Mission in 1888 and started reorganizing the Church there, beginning at ‘Aunu‘u. For more background on this interesting story, see Spencer McBride, “Mormon Beginnings in Samoa: Kimo Belio, Samuela Manoa, and Walter Murray Gibson,” in Mormon Pacific Historical Society Proceedings 2006, 50–63.

[8] “Jenson’s Travels,” Deseret Weekly News, February 8, 1896.