The Friendly, or Tongan Islands, August 1895–September 1895

Reid L. Neilson and Riley M. Moffat, eds., Tales from the World Tour: The 1895–1897 Travel Writings of Mormon Historian Andrew Jenson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 113–39.

In perusing literature on the Polynesian race, I find that several authors refer to the apparent similarity between some of the characteristics, religious ceremonies, etc., of the Polynesians and the ancient Jews, or Israelites. They also generally favor the theory of a common origin and close relationship between all the brown-colored inhabitants of Polynesia, including those of the Hawaiian Islands, Samoa, Tonga, New Zealand, the Society Islands, the Tuamotu Archipelago, and other groups lying between New Zealand and America. Though most whites try to advance the cries for an eastward emigration from Asia and the East Indies, they all have to acknowledge that the proofs are lacking to sustain the same.

—Andrew Jenson

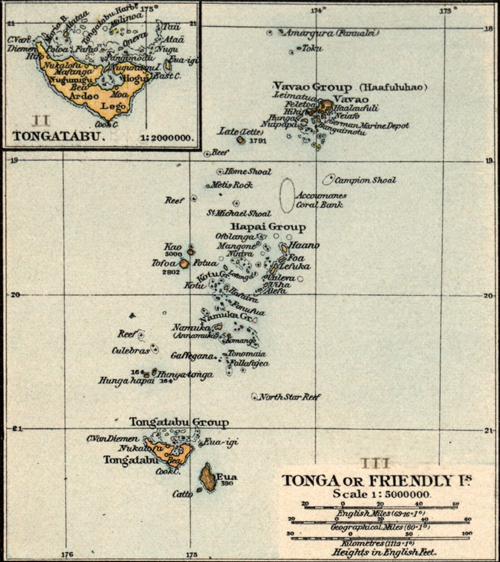

Tongan Islands, The Times Atlas (London: Times, 1895), 6

Tongan Islands, The Times Atlas (London: Times, 1895), 6

“Jenson’s Travels,” August 24, 1895 [1]

Nuku‘alofa, Tongatapu, Tonga

Thursday, August 22. I spent the day at the mission house at Mu‘a, perusing and culling from the mission records, which have been well kept from the beginning.

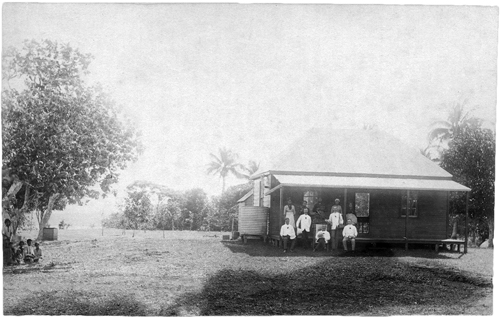

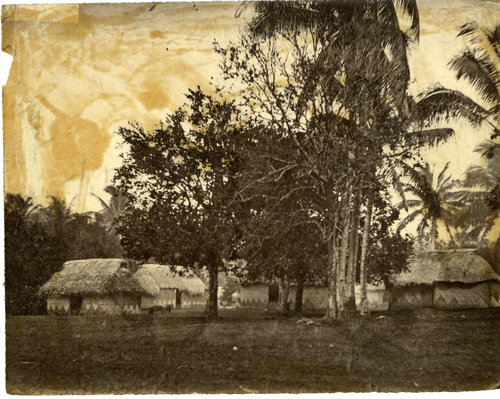

The mission house consists of a four-room frame building facing southeast. The two large rooms were built in 1861–1862, and the two smaller added in 1893. (Photo of mission home) There is also a small kitchen and a little storehouse adjoining the main building. The lumber and iron roofing used in its construction were imported from New Zealand. The land on which it stands—about one and a half acres—belongs to the government like all other lands on Tonga, and the mission pays $20 per annum in rent for the use of it. Most of the lot is covered with a natural grass lawn, but there are also a number of trees on it, among which four breadfruit trees (from which the brethren get all the breadfruit they need while it is in season), four coconut palms, and sixteen orange trees. Besides this, the elders have free access to a fine coconut grove lying adjacent to the mission premises, from which they can get nearly all they need in the coconut line. They very seldom have to buy any, and if they do they get all they want at the rate of half a cent per nut. Oranges can be had for twenty-five cents per hundred; but the brethren can get all they want for picking them, as a rule; and at other times the natives bring them some in exchange for matches, writing paper, envelopes, pepper medicine, etc., which costs next to nothing. Most of the ufi which they use they obtain in a similar way, though sometimes they buy it at the rate of three-fourth cents per pound. Flour costs about $2.50 per hundred; and meat (canned), salt, and sugar are somewhat expensive; but taking it all through the expense for food, which the elders cook for themselves, foots up to only about twelve cents per day for each man. The brethren take turns in cooking, changing every day, and the only objection that one would naturally have to the mode of living is the sameness in the food. It is ufi, rice, and coconut sauce at every meal, of which only two are taken per day, namely, breakfast between nine and ten in the morning and dinner between four and five in the afternoon. They have breadfruit about six months in a year; occasionally they also eat sweet potatoes and fish. Bananas are also plentiful. For a cheap and easy living Tonga stands ahead of any locality and country that I have ever visited. In fact people could subsist for months on what nature herself provides for the inhabitants, without any exertion on their part except to pick fruit and eat. And this naturally makes the natives of the Tongan Islands the most independent people imaginable. That this has a tendency to make them lazy and indolent is but natural. The average Tongan is not supposed to work more than about one day per week.

Mission home at Mu's, Tonga. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Mission home at Mu's, Tonga. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

The lot upon which the mission house stands is four chains (sixteen rods) deep and three chains and sixty-five links (fourteen and three-fifths rods) wide. The southeast side faces the government road and the opposite side the sea beach, or rather the lagoon shore. Through them is a narrow strip of government land intervening, reserved for beach purposes. The house stands back from the road about five and a half rods, and one and a half rods in from the northeast line. The distance from the house to the boat landing is about twenty rods. On the three sides of the premises are beautiful coconut groves, and the one immediately in front of the house, across the government road is particularly pleasing to the eye, though it shuts off the inland view entirely. The view to the northwest is toward and over the lagoon, which at the point is about one mile across. The wooded island and peninsula on the other side, with their tall coconut trees rising high above the thick foliage which reaches clear down to the water’s edge, presents a very fine landscape. Taking it altogether, I think the Tongan mission house is a very good sample of a tropical home. The house itself with its broad verandas and all its surroundings certainly entitles it to that distinction. The lot is not fenced. There is a native home standing just seven rods northeast of the mission house, occupied by what could consistently be termed a sample native family. They are quite neighborly and kind to the missionaries and occasionally attend meeting, but as they belong to the Wesleyan denomination they do not feel at liberty to adopt the religion of their neighbors.

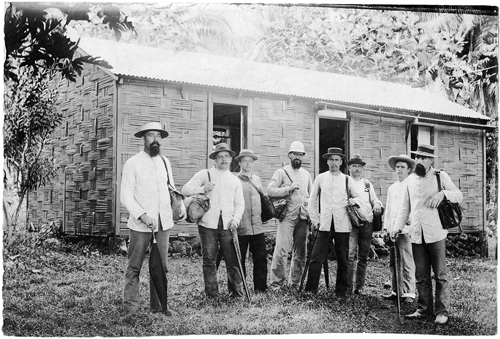

The elders are supposed to spend most of their time out among the natives in their respective villages, but it is often hard to get food and lodgings; hence, the mission house is naturally made more attractive than it otherwise would be the case, especially for the new elders who are learning the language and who, until they can speak it, would not fare well among the natives.

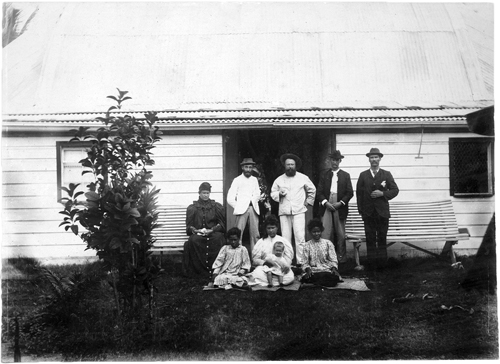

Missionaries and natives at the mission home in Mu'a, Tonga. Courtesy of Church History Library

Missionaries and natives at the mission home in Mu'a, Tonga. Courtesy of Church History Library

The young elders when at their mission headquarters are by no means idling away their time. They are studying hard to learn the language and to post themselves in regard to the principles of the gospel; and their hearts are in the work before them, and it would be unjust to ascribe the little success attending their labors so far in Tonga to any lack of energy and earnestness on their part. The usual daily routine at the mission house is to rise about 6:00 in the morning, and have prayer at 7:00 a.m. Before prayer is offered a chapter or two is read from the Tongan translation of the Bible and a hymn is sung; the same is repeated in the evening, prayer being offered at 8:00 p.m. Between breakfast and dinner, the only two meals taken, the brethren attend to their general labors. The evenings are usually devoted to some public duty or other. Thus Tuesday nights are devoted to testimony meetings, conducted in the Tongan language, and Thursday evenings to singing practices. The general meetings are held on Sundays, namely, at 9:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. In the evening a testimony meeting is held, the English language being used.

Mu‘a, where the mission house is located, is the largest native village on Tongatapu. It is beautifully situated on the south side of the lagoon and is surrounded by coconut groves. It has a population of nearly one thousand. There are only six white men in the village, five of whom are traders. Three of them have families. By all these the elders are treated with considerable kindness and consideration, and one of them at least is investigating the principles of the gospel. There are five Church buildings in Mu‘a, a Catholic and a regular Wesleyan. The Free Church meets in a native house but is about to build a church. The Catholic priest is a white man—French; the other ministers are all natives. The island of Tongatapu contains about sixty native villages altogether, all of which have been visited repeatedly by our elders, and meetings have been held in most of them. In September last Elders Alonzo D. Merrill and Alfred M. Durham also visited the neighboring island of ‘Eua and preached the gospel there. That island has five villages and over three hundred inhabitants. The brethren named, during their visit, held one meeting and bore testimonies in every village.

The Tongan, or Friendly, Islands, lie about five hundred miles southeast of the Fiji Islands and about the same distance south of Samoa. The distance from Nuku‘alofa, the capital, to Auckland, New Zealand, is about one thousand miles, and to Sydney, Australia, seventeen hundred miles. The islands are divided into three subgroups by two wide channels. In the southern cluster lies Tongatapu, the largest island of the archipelago. They are surrounded by dangerous reefs. The natives belonging to the fair Polynesian race compare favorably with other South Sea Islanders in mental development; in the structure of their dwellings; and in the preparation of their implements, weapons, dress, etc., betraying considerable skill and dexterity. The islands are all low, consisting either of raised coral or volcanic deposits, and there are still several active volcanoes among them. Tofoa, to the west of Ha‘apai, is always smoking; Late, southwest of Vava‘u, is also active occasionally, as is Fonualei, to the northwest; and there are several other extinct cones.

The Tongan dialect is harsher than the Samoan and is supposed to have been influenced by contact and intermixture with the Fijians. The people have all been converted to some sort of Christianity many years ago, but, as in almost every other instance, they are diminishing in numbers. In 1847 the population was estimated by the missionaries at 40,000 or 50,000, which has now diminished to less than 20,000. The chief exports are coconuts, oranges, bananas, and pineapples, while ships obtain ample supplies of other vegetables. The people rank as first-class boatbuilders and sailors, visiting in times past all the adjacent groups in their fine canoes.

The foregoing is taken from an old geographical work; and the following is culled from the Reverend Thomas West’s Ten Years in South-Central Polynesia, an excellent work of 500 pages, published in London, England, in 1865. This and William Mariner’s Tonga, written by John Martin and published in London in 1818, [2] appear to be the best works ever published on the Friendly Islands. Nothing important has been issued from the press in regard to Tonga of late years, except some letters written by “The Vagabond” for the Melbourne Leader, which subsequently appeared in pamphlet form, billed “Holy Tonga,” but is said to be unreliable.

The Tongan Islands comprehend three principal and well-defined groups. (Map of Tonga from Times atlas, 1895, p.6) Fifteen of the islands rise to a considerable height; thirty-five are moderately elevated; and the rest are low. The three divisions are known as the Tongatapu, the Ha‘apai, and the Vava‘u islands. The Tongatapu group contains Tonga, the chief and largest island, from which the group is named and which by way of distinction and eminence is most generally called Tongatapu, which means “Tonga the Sacred.” This island is about forty-five miles long and from seven to eight miles wide. It is situated between latitude 21˚ and 21˚20´ S and longitude 175˚ and 175˚20´ W and contains Nuku‘alofa, the capital of the kingdom of Tonga. Next in importance is ‘Eua, situated about eleven miles southeast of Tongatapu. It is thirteen miles long by about six miles in breadth and attains an elevation in some places of nearly six hundred feet. There are also about twenty small islands surrounding the two above named, of which ‘Eueiki, Pangaimotu, ‘Atata, and Fafa are the largest. With the single exception of ‘Eua, none of the Tongatapu group reach any considerable elevation.

The Ha‘apai Islands are separated from the Tongatapu group by about thirty miles of clear sea at their nearest point, from whence they extend northward over a distance of seventy miles. The whole group is composed of fifty-seven islands, most of which are small, lying between latitude 19˚35´ and 20˚45´ S and between longitude 174˚10´ and 175˚10´ W. A few only are inhabited. The whole group is intersected by alternate reefs and deep sea channels, which make the navigation both intricate and dangerous to strangers. The islands are all of low elevation with the exception of the volcanic islands of Tofua and Kao. In addition to the two islands named, Lifuka, Ha‘ano, Foa, Lofaga, Mo‘unga‘one, ‘Uiha, Fonualoa, Uoleva, Otu-Tolu, Nomuka, Ha‘afeva, Tungua, and Fotuha‘a are the principal islands in the Ha‘apai group. Between Tonga and Ha‘apai there are also two high islands called Hunga Tonga and Hunga Ha‘apai. They lie about twenty miles to the westward of the usual course from the one group to the other, and they are separated from each other by a deep sea channel of about one and a half miles wide. They give clear evidences of volcanic origin and are haunted by innumerable flocks of sea birds.

The Vava‘u group (also sometimes called Ha‘afuluhao) is the most variegated and beautiful of the Tongan or Friendly Archipelago. Of the islands that compose it, Vava‘u, embracing about one hundred and fifty square miles of land, is by far the most important, and contains nearly all the inhabitants. Grouped closely around the large one are about one hundred small islands, of which the most important are Pangaimotu, Falevai, Nuapapa, Hunga, Koloa, Kapa, Ofu, and Ovaka. The others are mere islets, chiefly lying to the southward, in close proximity to each other. The location of the Vava‘u group is between latitude 19˚ and 19˚30´ S and longitude 173˚50´ and 174˚10´ W.

West of Vava‘u is the volcanic island of Kau, and northward and eastward lies the islands of Tofua; Fonualei, or Amargura; Boscawen’s Island; Niuatoputapu; and Niuafo‘ou. The last-named island is situated in latitude 15˚30´ S and longitude 175˚45´ W. The neighboring island Niuatoputapu lies in latitude 16˚ S and 174˚ W. Both belong to the Tongan Kingdom, though their geographical position (lying as they do between Vava‘u and Samoa) places them very far away from the seat of government. Amargura lies in latitude 18˚ S and longitude 174˚20´ W. Prior to 1846, that island was inhabited and covered with verdure and fruit trees. But in the year named it blew up with an explosion, which was heard 130 miles off, and was reduced to a huge mass of lava and burnt sand, without one leaf or blade of any kind. The people had all escaped, warned by violent earthquakes which preceded the eruption. The sea was covered with ashes for more than sixty miles, and the trees and crops at Vava‘u forty-five miles away were seriously damaged. At the time of the catastrophe, an American whaling ship commanded by Captain Samson en route for Vava‘u fell in with and passed through a thick and heavy shower of ashes and pumice stone. He reported the experience as follows:

“At the time we saw the cloud it was a double-reefed topsail breeze from the northeast; but it was a beautiful clear starlight night. As we approached, it appeared like a squall; and as soon as we entered, the eyes of the men on watch were blinded with fine dust. Captain Samson put the ship about, but being convinced that there was no land near he again kept his course. When the sun arose, the dust appeared of a dark red color, rolling over like great volumes of smoke and presented an appalling appearance. At 8:00 a.m. it became so dark that candles had to be lighted in the cabin. At 11:00 a.m. the atmosphere began to clear a little, and the sun was occasionally seen. By noon we were clear out of the cloud, being then in 170˚45´ W longitude and 21˚02´ S latitude, having sailed through the shower of ashes at least forty miles.” Captain Cash, of the ship Massachusetts, got into the shower about the same time, though his course lay in the vicinity of Savage Island, probably sixty miles to the eastward of Captain Samson’s position.

The absence of running streams or rivers is one of the characteristics of the Friendly Islands. There are only two very insignificant exceptions throughout the whole group. These occur at Vava‘u and ‘Eua. That at Vava‘u is an underground stream and is reached with difficulty by descending a considerable depth into a natural cavern that can only be explored by the aid of torches. The streams on ‘Eua are very small. For soft water the inhabitants depend entirely upon what is collected from the clouds, either in tanks or day pits, called by the natives lepas. The rainy months are December, January, and February. The average temperature during the entire year is 76˚ F. During the hot months, from December to March, the thermometer frequently rages at 90˚ and even 96˚ in the shade. The islands are subject to hurricanes, which seem to occur with periodical regularity and always in the rainy season from December to March. “The full force of the cyclone falls upon one or other of the three groups at intervals of about seven years,” writes the Reverend Thomas West. “The hurricane gives but few indications of its approach. The wind rises suddenly, accompanied by heavy rain, and its duration, strength, and progress, in any given locality, depends upon its being nearer to, or more remote from, the center of the wind circle. No tongue or pen can possibly convey an adequate idea of these visitations. Heaven and earth appear to be on the move; and, as for the sea, its grandeur is altogether indescribable. The rush of the irresistible tempest; the cracking and fall of trees on all sides; branches hurled through the air; coconuts torn from the trees and flung in all directions with the velocity of cannonballs; a deluge of rain; unusual darkness; and the crash of falling houses—all these attendants upon a hurricane make up one of the most dismal and terrific pictures in natural phenomena. The destruction of dwelling houses and other buildings usually attended upon these visitations must, however, be attributed not merely to the force of the wind but also in great measure to the torrent of rain. The fact is the heavy rain soon saps the foundation of the large posts upon which the security of the building depends. Gradually the wind sways the superstructure to and fro, and at every gust opens and widens the earth around the sockets of the posts, until the entire fabric loses its equilibrium, and coming down with a crash, all its posts and beams, however tough and thick, are snapped like so many carrots.” [3] During a hurricane in Vava‘u many years ago, thirty-four out of thirty-nine Wesleyan chapels were blown down, though these buildings were the very best and strongest constructed by the people.

All the islands are subject to earthquakes, which are both frequent and violent. The brethren who are laboring here now have experienced the peculiar sensation of being violently shaken by Mother Earth a number of times, but the occurrence of earthquakes produces but very little alarm among the natives whose houses cannot be shaken down by them.

Like many of the Polynesian groups, the Friendly Islands are entirely free from noxious snakes and serpents, nor are there any frogs or toads. It seems hard to determine what were the indigenous animals of the islands. Captain Cook, when visiting the islands in 1777, found hogs and dogs; but it is supposed by some that these were left by the Dutch navigator Tasman, nearly a century before. Horses and cattle were reintroduced by the missionaries about 1860. They were first left by Captain Cook but became distinct [extinct?] during the long series of wars that succeeded the period of his visit. Sheep also were added by the missionaries to the stock of fine goats that had been introduced at an earlier date. The common domestic fowl, the moa of Polynesia (a chicken) is plentiful, both in the apis (home) of the natives and in all parts of the “bush.” The pato, or Muscovy duck, also abounds, and there are some turkeys. Geese and English ducks have been introduced, but they do not seem to thrive. The sea birds comprehend several varieties of gulls, bitterns, and herons. In Tonga, as in all tropical countries, insect life swarms and luxuriates, as much as the vegetation. Ants, black and red, swarm everywhere, and so do lizards and beetles of all kinds. The ants became so troublesome at the mission home at Mu‘a that Elder Atkinson, who ranks as the inventor of the little family of elders, had to fall back upon his genius in order to secure the scanty supply of sugar kept in the house from the extraordinary appetites of the ants. That the sugar bucket was suspended on a long string from the ceiling of the kitchen was to no effect; the little pests would climb to the roof and then march down in single file to the bucket, and there feast; hence, an original contrivance was thought of and adopted. But as it is not patented yet, I don’t feel at liberty to describe it here. It seems that a well-fitting lid might have had the same effect. The mosquitoes are also plentiful and troublesome on the islands.

According to a census taken in 1891, the total native inhabitants of the Tongan Kingdom consisted of 19,186, distributed upon the different groups and islands as follows: Tongatapu, 6,675; ‘Eua, 353; Ha‘apai (groups), 5,404; Vava‘u (groups), 5,084; Niuatoputapu, or Keppel Island, 667; and Niuafo‘ou, 993. The number of whites on the whole group is 353, which, added to the native population of 19,186, gives a grand total of 19,539 for the whole kingdom. There are only five post offices in the kingdom, namely, Nuku‘alofa, the capital (on Tongatapu); Neiafu (on Vava‘u); Lifuka (on Ha‘apai); Niuafo‘ou; and Niuatoputapu. The natives are nearly all more or less educated; nearly every person over ten or twelve years of age can read and write the native language; but only a very few of them can speak English.

“Jenson’s Travels,” August 26, 1895 [4]

Mu‘a, Tongatapu, Tonga

Friday, August 23. I continued my labors at the mission house at Mu‘a, and was also introduced to several natives who came to visit us. I also began to feel reconciled to the Tongan vegetable diet, which at first did not seem to have just the right flavor. The chief article of vegetable diet raised and eaten by the Tongans is the yam, or native ufi (Diosorea alata is its Latin name). This, in fact, is the most valuable of the edible roots of the tropics; and it is perhaps not cultivated in any other part of the world to such high perfection or in such quantity as in Tonga. The Tongans do not believe at all in the Fijian practice of putting yam settings into hard and unprepared soil. The plan adopted in Tonga involves great care and labor but is rewarded by large crops of the most valuable esculent root to be found in the world. After the surface of the ground has been thoroughly cleaned of bush and weeds, the first part of the operation is that of digging the yam pits, or puke. These are dug at a diameter of from two to four feet and are from three to seven feet in depth, according to the kind of yam planted. The earth is dug completely out of these pits, by the aid of small iron huos, or narrow lance shaped spades, attached to a long wooden handle; and when the required depth has been reached, the loosened and pulverized earth is returned to the pit. This is done to permit the easy and rapid growth and expansion of the yam roots, which shoot downward like huge carrots. The pits are placed at equal distances from each other of about two or three feet, arranged in rows, and in the alternating order of the squares of a chess board. Meantime, the settings have been prepared by slicing ripe old yams into pieces, varying from two to four inches in thickness. These are buried for a few weeks, until the vital portions of the yam have begun to sprout. This plan is necessary because there are no eves, or bud-marks, on the skin of the yam, such as are found in potatoes and other edible roots. Having sprouted, the good and vigorous settings are taken to be placed in the top of the yam pits, at a depth of about three or four inches. When the vine has sprung up and begins to spread, it must be very carefully and constantly cleared of weeds and must also be protected as much as possible from the effects of high winds. If the vine be damaged, the yam root suffers in proportion; and should it be destroyed by being chocked with weeds, withered by the sun, or torn by the wind, the root beneath speedily perishes. The operation of ututa‘u (the Tonga harvest), or raising the yams when fully ripe, is even more laborious and difficult than that of the first preparation of the pits. To get them out of the ground, these must be carefully opened, and the earth be removed from around each individual root. Thus, when these have shot down to a depth of five or six feet, as is the case with the larger sorts, the toil in lifting them safely out of the ground becomes very considerable. Owing also to the fact that any cut or abrasion of the skin of the yam soon causes it to rot, all the more care and skill become necessary in removing the roots from the soil. The setting very rarely produces more than three roots in each pit. Therefore, in order to raise the large quantity of yams necessary for the consumption of the people, as well as the supply of foreign vessels, very extensive tracts of country are put under cultivation. The visitor, in passing through the country, will observe on every hand the fruits in native industry in the well-kept and large yam plantations, of which they are justly proud. There are many varieties of yam, but the Tongans are remarkably clever in rejecting inferior sorts. Single yams vary greatly in size and in weight, ranging from seven to eight pounds, according to species. Yams of from sixty to eighty pounds’ weight are by no means uncommon. Elder Durham has seen them as long as six feet.

Other edible roots that are greatly like the yam and are cultivated in the Society Islands, and elsewhere in the Pacific, are but slightly regarded by the Tongans. Among these may be reckoned the kumala, or sweet potato, and the talo, or kalo, as it is called on the Hawaiian Islands. Both are grown in Tonga, but the former is considered to be a very poor substitute for the yam, while the latter requires such marshy land for its perfect success that only a very few spots are found suitable for it in the Tongan Islands.

The coconut tree deserves special mention, as this tree and its fruit are very unquestionably the most abundant and characteristic of the country. Whole forests of these beautiful palms flourish in nearly all the islands of the Tongan Archipelago. In those islands that are of moderately high elevation, they crown the hilltops and sides, while in every quarter to which the eye may be turned the land appears clad with their graceful foliage, down even to within a few feet of the sea itself. Proximity to the ocean, and a sandy soil, appear rather to favor than to hinder the rapid and healthy growth of the tree. Some of the finest and tallest specimens are met with on the shores of the lowest islands. In such situations they attain an elevation of eighty and even ninety feet. Hence an approaching voyager often discovers the tufted heads of the palms in the distance long before the land itself upon which they grow becomes visible. This was also my experience in nearing some of the islands, and on one or two occasions I was led to ask my fellow travelers if the trees grew out of the bottom of the ocean, as there appeared to be no land where the trees were plainly seen. The natives of Tonga reckon at least nine different kinds of coconut trees, for all of which they have distinctive names. All these are known and included under the generic name of Niu. In addition to the multifarious uses to which every portion of this tree has been devoted from time memorial, the natives have for many years past derived from it large revenues of wealth by the exportation of the copra (the dried coconut meat) to the markets of the world to be manufactured into oil, soap, etc. The exports of copra in 1889 alone were 7,957 tons, valued at $366,676. The other principal exports from the islands are green fruit (mostly oranges, bananas, and pineapples), fungus, kava, and whale oil. The estimated produce of a full-bearing coconut tree is from ninety to one hundred nuts per annum. Nearly every particle of the tree can be utilized. The natives eat its meat, drink its milk, make ropes of the fibers of the husks, use the leaves to thatch their houses with, the stems of the leaves for brooms or sweeping purposes, the timber for building their houses, and those parts of the husks of the nut which they do not use for making rope and strings, they utilize for fuel. It only takes a few coconut trees to sustain a family. The natives use the bark of the so-called Chinese mulberry (called hiapo in native) for the manufacture of cloth.

The breadfruit grows on a tree of about the size of a common oak, which towards the top divides into large and spreading branches. The leaves are of a very deep green. The breadfruit springs from twigs to the size of a five-cent loaf. It has a thick rind, and before becoming ripe it is gathered and baked in an oven. The inner part is like the crumb of wheaten bread and found to be very nutritive. It has neither seed nor stone in the inside, but all is of pure substance like bread. It must be eaten new; for if it is kept above twenty-four hours it grows harsh and choky. The fruit lasts in season from five to eight months in the year according to the locality. There are said to be at least fifty varieties of the breadfruit tree. Those common to Tonga are known by the generic name of mei with distinctive appellatives attached to the word descriptive of the different kinds. The brethren, and the Europeans generally, simply pick the fruit when it is ripe, then either boil or bake it, and eat it with sauce or other seasoning the same as they do potatoes or the ufi. But the natives, in addition to preparing and eating it in a somewhat similar way, also make it into so-called ma, or bread. In that instance the fruit is beaten up and incorporated with the sweet banana and scraped coconut. It is then divided into small balls, or portions, which are buried in a large mass underground, there to undergo fermentation. The ma is left buried for several months, after which it is fit for food and will keep if not exposed to the air for a long time. When the ma pit is opened a very strong and disagreeable odor gives intimation of the fact to a considerable distance, while the bread itself, to a British or American palate, is even less acceptable than the black bread of Russia. In taste it is said to resemble what a mixture of barley bread and rotten cheese might be supposed to be. It is nevertheless very nutritive, and it would be a good resource in season of famine.

One of the most distinctive tropical sights is perhaps an extensive banana plantation. In the Tongan Islands all the varieties of the trees flourish in highest perfection. The fruit hangs in single bunches upon a strong stem issuing from among the leaves. Each bunch will weigh from thirty to even eighty pounds. The fruit is of various colors, and of great diversity of form, according to the description of tree planted. It is usually long and narrow of a pale yellow or dark red color, with a yellow or slightly pink farinaceous flesh. The best sorts surpass the finest pear in excellence of flavor, according to the taste of some. They are eaten raw, or may be baked, stewed or boiled according to fancy. The leaves of the banana are put to various uses by the natives. One leaf can in a few minutes readily fashioned into at least half a dozen drinking cups; while by gently heating an entire leaf over a slow fire, through which it is rendered at once pliable and tough, wrappers can be made to bake fowls so as to retain their gravy, or in which even fish soups can be cooked without any loss of the liquid.

The Reverend Thomas West writes that he frequently saw a banana leaf bag, containing a gallon or more of coconut oil that had been carried safely for many miles. Portions of the juicy stem of the tree are generally brought, at the conclusion of a meal to be used by the guests, instead of soap and water, in cleaning their fingers, after these have performed the duties of knife and fork. It does this very effectively when well shredded, by rubbing between the hands. In the Hawaiian Islands, where water is more plentiful, the natives pass around a bowl or pan of water in which they wash their hands both before and after meals.

The soil of the low islands of the Tongan Archipelago is composed of a rich black mould with more or less of admixture which sand, according to the distance from the sea. Such is the natural fertility of the land, and such the rapidity with which vegetation grows and decays, under these tropical skies, that the natives never think of employing artificial means to improve the soil. All the land is owned by the king or chiefs and is never sold to either natives or whites. The whites lease their lands from the government; and every male native, after reaching the age of 14 years, can obtain land for cultivation and use it as long as he likes free of charge but he pays his taxes. He cannot become the owner. If a man, either single or married, desires to move to another locality, he can, upon application to the pulekolo, or local official, obtain land for his use in such locality. Thus there can be no speculation in lands in Tonga; and this is therefore no field of operation for American real-estate boomers. Though a law thus prohibiting the permanent alienation of land from the government would be extremely obnoxious in a white man’s country, it seems to operate well in Tonga. The lands are preserved and retained for the benefit if the natives as the original owners, and does not, as in the case of Samoa and Hawaii, pass into the hands of white speculators.

All the best islands belonging to the Tongan kingdom contain trees which yield good timber for building purposes, especially native houses; but both in variety and quantity the supply is limited. The natives seem to take no pains to increase the stock of timber yielding trees. The best and largest trees are used in the construction of canoes. Popao, the smallest class of paddling canoes, are always cut out of single trees. Talaaas, the beautiful and swift canoes that are used in fishing, and also the hamateluas, or sailing canoes, having only a single hull and large outrigger are all built of planking in the same style as the large kalias. These two classes of canoes involve great waste of valuable wood, as only two or three planks can be obtained from a single tree. Timbers for the erection of such frame dwellings as the whites occupy are imported from New Zealand.

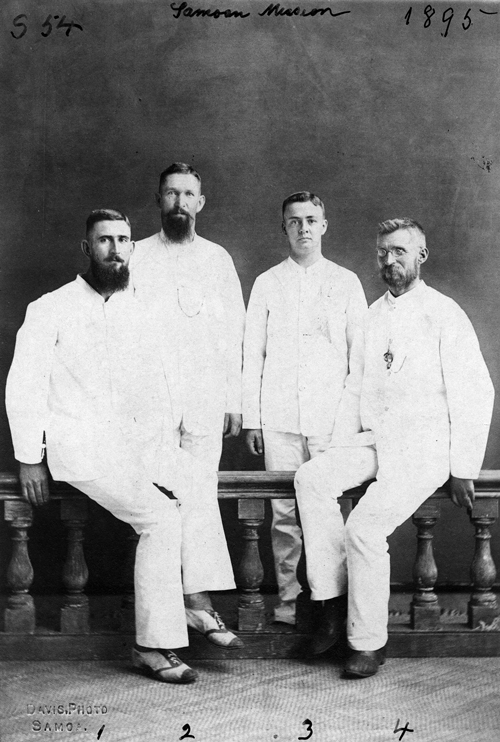

A Tongan house suits the few necessities and easy habits of the people that have none of the comforts considered assented to a higher type of civilization. (Photo of native house) With the exception of the dwellings of the chiefs of higher rank and the public native buildings, their dimensions are small, and they contain but one or two apartments. They are, however, constructed with an eye to neatness and great strength. Many when elaborately finished in the best native style, their interior appearance is by no means to be despised. But they are much smaller than the houses of the Fijians. The walls range from four to eight feet in height, and are formed either of a single or double fencing of reeds, which when interlaced and bound by sennet to the tokotu‘us, or stakes and posts, planted all around the eaves of the building, resembles very much strong basket work. These walls are sometimes made more wind and water tight by the addition of a lining of plaited coconut leaves; but at the best, they afford a sorry resistance to strong winds or heavy rains. On the other hand there is capital ventilation. To compensate for the lowness of the walls the roof of a Tongan house carried to a considerable height. The rafters are closely set, and are generally made of the outer wood of the coconut tree, or the breadfruit tree, the latter of which has much the appearance of cedar wood and has a very pleasing and beautiful effect when nicely finished. The large beams to which the rafters are attached are laid along the grooved tops of high and durable posts which reach about half way up the entire height of roof. The inner ridge pole is usually ornamented by a profusion of sennet wrappers of varied colors and geometrically interlaced. The roof itself is covered with a thick thatch made from the leaves of coconut tree, the sugar cane or of the bamboo, and is perfectly watertight. A well built house will last a good many years, but the thatching requires to be renewed, under the most favorable circumstances, about once in five years. The floor is laid with a profusion of dried leaves which are in turn covered over with numbers of mats made from the coconut leaf, upon which again the finer sitting and sleeping mats are placed. No provision is made in the interior of either native or white man’s house for cooking conveniences. A separate building contains the kitchen requisites, and the heat of the climate renders a fireplace in the dwelling house unnecessary. The length of an average native dwelling house is 20 feet by 10 feet in width. The ends of the houses are always circular in form. Even the more modern houses built of imported lumber are built with rounded ends. Some of the modern houses are supplied with windows which are lacking in the older dwellings.

Native houses in Tonga. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Native houses in Tonga. Courtesy of Church History Library.

“Jenson’s Travels,” September 1895 [5]

Pangai, Lifuka, Ha‘apai, Tonga

Saturday, August 24. In company with Elders Alfred M. Durham and Charles E. Jensen, I left the mission house at Mu‘a and went by boat and on foot to the capital, Nuku‘alofa, distant six miles, where we called on the Reverend James B. Watkin, who stands at the head of the “Free Church of Tonga.” He received us kindly and gave us some important information in regard to the Wesleyan missionary operations on the Tongan Islands and the origin of the “Free Church.” He also showed us through the king’s palace and the royal church edifice which lies adjacent to the palace and Mr. Watkin’s own fine two-story residence. Mr. Watkin has befriended the elders on difference occasions and has made them a present of several Bibles in the Tongan language. From him and other reliable sources, I have gleaned the following:

The Tongan Islands were first discovered in 1643 by the great Dutch explorer Jansen Tasman, who gave the principal islands Dutch names. Thus he named Tongatapu, the principal island, Amsterdam Island. Captain James Cook visited the islands in 1777; and he was so pleased with the treatment he received at the hands of the natives that he named the group the “Friendly Islands,” which, however, subsequent events showed to be an inappropriate title, as the Tongans proved anything but friendly to the whites; and it was learned that they had even planned the massacre of Captain Cook and all his men for the sake of spoil; but he sailed away before the time set for his execution arrived. The first permanent white man who located at Tonga was an escaped Sydney convict named Morgan, who lived happily with and was respected by the natives till the mission vessel the Duff arrived from Tahiti with ten missionaries of the London Missionary Society. These first missionaries to Tongatapu had a hard time of it, and during the civil war which raged at that period on the islands, three of these were murdered; and the others, after being plundered of their property, saved themselves by flight to the western district of the island, from whence they were at length (in 1800) removed to Australia by the captain of a merchant man, who touched at Tonga on his voyage from the Society Islands to Port Jackson. Nothing further was attempted by way of Christianizing the Tongans until 1822, when the first Wesleyan missionaries, the Reverend Walter Lawry arrived at Tongatapu. He landed August 16, 1822, together with his family; but domestic circumstances necessitated his removal in the latter part of 1823. During his short sojourn he had received much kindness from the chiefs of Mu‘a, where he had located himself, but made no converts. Two years later two Christian natives from the island of Tahiti landed in Tonga and located at Nuku‘alofa, where they immediately commenced preaching; a place of worship was soon erected at which about three hundred people assemble to take part in Christian services on the Sabbath. The king, Tupou, gave his personal support to the work. In June 1836 two other Wesleyan missionaries arrived from England and located at Hihifo, on Tongatapu, where they built a wooden house and commenced to study the language and teach the people, working entirely independent of the Tahitian teachers. The names of the two missionaries were John Thomas and John Hutchinson. Two other Wesleyan missionaries came in 1828 who worked in unison with the Tahitian natives, and from this united effort the cause proved a success. The staff of missionaries was further increased in 1829, when the Wesleyans had thirty-one regular Church members on the islands, which in 1834 had increased to 7,451, including the membership on the Ha‘apai and Vava‘u islands, where a successful mission had been opened in 1830, and in the Vava‘u groups, where the first native Christians commenced operations in 1831; white missionaries came later. The first French Catholic missionaries arrived at Tongatapu in 1842 and located at the heathen fortress of Bea, from whence they extended their operations to Mu‘a, which is still a Catholic stronghold. The Wesleyans accused the Catholics of making common cause with the heathen part of the Tongan population and of other crooked work; and the consequence was a bitter feeling between the Romans and the Protestants, which still exists. But the Wesleyans kept the upper hand, and in 1865 there were 169 Protestant places of worship in the Tongan kingdom connected with which were 24 European and native ministers, and a total membership of 9,822. The late King George, who (as the former king of Ha‘apai and Vava‘u) became king of all the Friendly Islands in 1845 and reigned until his demise in 1893, was the great patron of the Wesleyan cause. By his aid Tonga was Christianized; he gave the Wesleyans land and privileges and made his people follow the faith of the Methodists. Among the Wesleyan ministers who gained great influence among the natives was a Mr. Shirley W. Baker. He arrived on the islands in 1860 and subsequently became the presiding Wesleyan there. The mission being in a flourishing condition, and the natives contributing very liberally toward supporting the church, a petition was drawn up asking the New South Wales and Queensland (Wesleyan) conference that Tonga be given a more independent position or a separate conference organization; but instead of granting the petition, the conference recalled Mr. Baker as the head of the Tongan mission, and he consequently left the islands in 1880. This action, which was considered unjust, displeased King George and his people very much; and the king advised his subjects to cease contributing of their means toward the Wesleyan Church; and he also offered the premiership of the kingdom to Mr. Baker, if he would return to the islands. Mr. Baker responded, resigned his position as a Wesleyan missionary, and returned to Tonga in 1881 to enter upon his new duties as premier. In his calling, as such during the following ten years, he was eminently successful; and the laws which he issued to be enacted and the improvements which were made under his advice and direction will ever make him live in history as one of the most remarkable and influential men who ever figured in the affairs of the South Pacific Islands. Under his protection and influence, also, the Wesleyans of Tonga broke entirely off from the parent church and established themselves as the “Free Church of Tonga,” with the Reverend James B. Watkin, formerly a regular Wesleyan minister, at its head. This was done in 1885. But as the old church held leases to the church edifices and refused to give them up, the Free Church found itself obliged to erect new meetinghouses and chapels all over the islands; and thus we find today duplicate Protestant houses of worship in all important villages and towns in the kingdom, even in places where there are not church-going members enough to half fill one. Mr. Watkin claims that seven-eighths of the inhabitants of the islands are members of the Free Church, leaving only between two and three thousand for the Catholic and regular Wesleyan membership. He also told us that since the secession in 1885 the Free Church had built 130 houses of worship on the islands without the least assistance from any outside source. To the Wesleyans of the old school belong the credit of translating the Bible into the Tongan language, it was printed at London, England, and several editions have already been published. The Wesleyans have also published several schoolbooks in the Tongan language and introduced a splendid school system throughout the kingdom. The Free Church is now publishing a periodical in native, entitled Koe Siasi Tau‘ataina (The Free Church), edited by the Reverend James B. Watkin. It is printed in Auckland, New Zealand, as there is no printing office in Tonga.

As might be supposed, the secession of the Tongan disciples from the regular Wesleyan Church has called forth much comment; and the Wesleyan ministers especially have been very outspoken in their unqualified condemnation of the actions of Mr. Baker and Mr. Watkin. On the other hand, the members of the Free Church feel perfectly justified in what they have. Mr. Baker, in defining his position in the matter to a newspaper correspondent seven years ago, said: “The Wesleyan Church has attempted to usurp as much authority as the Church of Rome did in the old days and has been as dangerous to individual liberty; I would not attempt to compare myself to the Protestant Reformers, but in establishing the Free Church of Tonga, I and Mr. Watkin have but done what John Wesley himself did in Great Britain. And King George has but done what Henry VIII did for Protestant England, but from far different motives. The king, for the sake of his people, would not submit to the dictation of an outside body like the New South Wales Conference. No one can defeat the sending away of such large sums of money to Australia.” [6] Mr. Baker, being a British subject, was exiled from Tonga about 1891 through the influence of his enemies, and since that time natives have filled the position of premier; but they have not come up to Mr. Baker’s standard. And there is now an almost universal desire in favor of Mr. Baker’s return. Mr. Watkin, as the head of the Free Church of Tonga, is not responsible to any ecclesiastical authority above him on the earth. This, so far as his church is concerned, makes him equal to the pope of Rome. The question might now naturally arise, where did he get his priestly calling from? By virtue of what authority does he preside?

While at Nuku‘alofa we also visited the grave of the late King George, over whom a fine monument was erected in 1894. The monument is placed upon a raised square built on rising ground in the outskirts of the town. The base consists of three terraces of which the lower one is 80 feet square and 4 feet high. The next one is 60 feet square and 2½ feet high, and the upper one 40 feet square and 2 ½ feet high, making the upper square 9 feet above the ground. The walls of the terrace are built of concrete or cement, while the center, or body, is filled up with dirt and gravel; twenty-seven easy and broad steps lead from the ground to the top of the terrace, on the top of which stands the monument proper. This consists of a large marble-plaited shaft resting upon a pedestal of cement with inscriptions of different kinds of its sides. The main epitaph reads in Tongan as follows: “Koe maka fakamanatu eni o Ene Afio Ko Jioaji Tubou I, Koe Tu ‘oe ‘otu Toga; na‘e ‘alo‘i ia ‘i h. 1797 ‘oe Ta‘u; bea na‘e takanofo ia koe Tu‘ikanokubolu ‘i h. 4 Tisema 1845; bea ne hala i h. 18 Febueli 1893.” Translated into English it reads: “This rock is in memory of His Majesty George Tubou I, king of Tonga, who was born in the year 1797, appointed king December 4, 1845, and died February 18, 1893.” From this it will be seen that the king was 96 years old when he died. For many years before his demise, he ranked as the oldest man among all the crowned heads of the world. In his palace we noticed a very fine oil painting of Emperor Wilhelm I of Germany, on horseback, which Mr. Watkin informed us had been presented to the old king as a present from the German monarch. A beautiful portrait of Queen Victoria of England also graced the walls of the reception room of the palace. It must be remembered that nearly all the white inhabitants in the Tongan Kingdom are English and German citizens. Hence Britain and Germany are the only two nations which are represented by consulates at Nuku‘alofa.

As we toward evening made our way through the forest to where the mission boat was anchored in the lagoon, Elder Durham prevailed upon one of the natives whom we met to climb a tall tree and get us some young coconuts. The milk of these, which we drank in connection with eating some cake that we had purchased at a baker shop at Nuku‘alofa, made us a most excellent meal, for we were quite hungry. This was the first time in my life that I ate coconut meat and drank coconut milk to satisfy my appetite. The wind being contrary we had to row all the way from our anchorage to Mu‘a, a distance of four miles, and it was quite dark when we found ourselves safely back at mission headquarters.

“Jenson’s Travels,” September 9, 1895 [7]

Neiafu, Vava‘u, Tonga

Sunday, August 25, 1895. A meeting was held at the mission house at Mu‘a at 9:00 a.m. Our congregation consisted of only six adult natives and some children. Elder Durham and myself were the speakers, he also translating for me. Our subjects were the Book of Mormon, the supposed origin of the Polynesian race, the Restoration of the gospel, and its first principles. All seemed pleased. Among those present were Alipate, our only member on Tongatapu and another baptized member from Ha‘apai, also a particular friend who answers to the modest appellation of Charley but whose real native name is Salesi Tonagamolofiaivailahi. Salesi is the Tongan for Charley. This is an intelligent man and a preacher in the Pui Church. He has been kind to the elders from the beginning and says he assisted Elder Brigham Smoot in his preparation of the only tract published by our people in the Tongan language. He expressed himself as a firm believer in our doctrines and said that he expects to become a member of the Church at some future day. He suggested that our elders here would find it to their advantage to pay particular attention to the chiefs or leading men and officials in the different villages, as the Tongans were a great people to follow their chiefs. If once the chiefs were converted to “Mormonism,” the majority of the people would in his opinion soon follow; but it was something unusual with the natives to take an independent individual stand in anything of importance and especially in departing from the religion of their chiefs or what is the popular religion of the land. We held another meeting in the afternoon, after which some of us elders attended services at the regular Wesleyan village church in Mu‘a, which he took from the 3rd chapter of Genesis, and he grew quite eloquent in his delivery before he got through. The singing was noisy enough but by no means sweet or harmonious. Most of the congregation sat on mats on the floor. After the meeting, the ministers and others came forward and shook hands with us warmly; but they made no overtures to religious conversations. The brethren tell me that the native Wesleyan ministers will hardly ever argue with them on doctrinal points. In the evening the usual testimony meeting was held in the mission house at Mu‘a, at which all the elders present (seven of us) spoke briefly.

In perusing literature on the Polynesian race, I find that several authors refer to the apparent similarity between some of the characteristics, religious ceremonies, etc., of the Polynesians and the ancient Jews, or Israelites. They also generally favor the theory of a common origin and close relationship between all the brown-colored inhabitants of Polynesia, including those of the Hawaiian Islands, Samoa, Tonga, New Zealand, the Society Islands, the Tuamotu Archipelago, and other groups lying between New Zealand and America. Though most whites try to advance the cries for an eastward emigration from Asia and the East Indies, they all have to acknowledge that the proofs are lacking to sustain the same.

Commenting upon the origin and prehistoric immigration of the Polynesian race, the Reverend Thomas West, in his Ten Years in South-Central Polynesia, writes: “There can be no doubt that the Tonganese religion bore in several particulars a striking resemblance to the ritual and economy of the Jewish ceremonial law. Indeed, this similarity prevails more or less in the various groups of Polynesia. Nor can it be denied that many of the inhabitants have strongly marked Jewish features. But it requires further research, and more proof, before we can adopt the conclusion some have come to that any portion of the people are of Israelitish extraction. A few of these points of resemblance may here be specified as a matter of interest:

“1. There obtained among the Tonganese a regular division of time into months and years, these divisions being worked by the recurrence of sacred seasons and public feasts, which were observed with religious ceremony and were under the sanction of the most rigorous laws. It is also remarkable that the Tonganese have some knowledge of an intercalary month, the use and disuse of which have led to many discussions among themselves.

“2. The entire system of Tapu, by which times, persons, and places, or things were made sacred, and the many religious restrictions and prohibitions connected therewith, may be easily interpreted as a relic much which changed and corrupted from the ceremonial observances of the Jews.

“3. The great fest of the Inaji, or offering of firstfruits to the gods every year, seems a custom of religious ceremony of purely Jewish origin.

“4. The same may be said of the right of circumcision which was regularly practiced by them. An uncircumcised person was considered mean and despicable, and the custom has only disappeared in recent years.

“5. Every person and thing that touched a dead body was considered unclean, and remained so until after the elapse of a certain number of days. During that allotted time those whose duties compelled them to do the rites of burial were not allowed to feed themselves or to touch the food prepared by others. They were, therefore, carefully fed by attendants.

“6. Females after childbirth, and after other periods of infirmity, were enjoined strict separation and were subjected to ceremonial purifications.

“7. Tonganese had cities of refuge corresponding to those instituted among the Jews; the uses and functions resembled, in some of their features, those of the Mosaic law. The Taula, or priest, was supposed to become inspired by the god as his shrine, or representative, while receiving and answering the prayers and sacrifices of the worshippers. These were offered through the Feao, or attendant upon the Taula, and it was also his duty to maintain the god house, or temple, in due repair and order.” [8]

Monday, August 26. I spent the day at the mission house attending to my duties as historian and also conversed with some of the natives who came to see us, through the aid of the other brethren.

Tuesday, August 27. After attending to the usual routine of work at the mission house, we held a council meeting in the evening, at which it was decided by unanimous vote that Elder James R. Welker and Charles E. Jensen should accompany me on my way toward Samoa as far as the Vava‘u group of islands distant 180 miles from Tongatapu and these open up the gospel door of endeavor to establish a new field of missionary labor among the inhabitants which comprise almost five thousand, or more than one-fourth of all the natives of the Tongan Kingdom. With the departure of the two elders named, only four missionaries will be left to “hold the fort” on Tongatapu; but this is also considered quite ample under the present circumstances.

Wednesday, August 28. After the day’s work at the mission house at Mu‘a, I took a stroll out through the town and adjoining “bush,” together with Elder Alfred M. Durham. On our walk we visited some peculiar ancient works in the shape of raised squares, which the natives say are old native burying grounds. One of these squares, which is regularly terraced, measures 120 feet in length by about 90 in breadth. The terraces are three in number, built on the same principle as the square raised over the remains of the late King George at Nuku‘alofa. At first, one was led to believe that the face of the terraces were built of huge rock, one of which measured 21 feet in length by about 6 feet in width and breadth; but on closer observation, I was inclined to the belief that, though hard as rock, it is a sort of concrete or cement compound, which, as the centuries rolled by, became hardened. There are nearly a score of similar squares, though smaller than the one described, in the same neighborhood. We also visited two of the village graveyards. The natives, after making the proper excavation for the reception of a dead body, never return the dirt thrown out to the grave; but, after lowering the remains of the dead, they fill up the grave with clean white sand obtained from the seashore. This accounts for the high ground which distinguishes all native burying grounds in Tonga.

Thursday, August 29. In reading William Mariner’s Tonga Islands today, I was struck forcibly with the apparent similarity between many of the characteristics, customs, and habits of the Tongans and the American Indians, which goes far to prove that their origin is the same, that they all belong to the same branch of the human family. The old heathen religion of the Tongan was based upon plurality of gods representing both good and evil and some of which they conceived of as eternal gods and others as more temporal deities. In many respects the Tongan religion was much akin to the Scandinavian mythology, comprehending Odin as the chief temporal god and a number of other gods representing war, peace, love, etc. There is a certain rock on the island of Hunga, which is still pointed out by the natives as the immediate cause of the origin of the Tongan Islands. “It happened once, before these islands were in existence,” says Mr. Mariner, “that one of their gods (Tangaloa) went out fishing with line and hook; it chanced, however, that the hook got fixed in a rock at the bottom of the sea, and in consequence of the god pulling the line, he drew up all the Tongan Islands, which they say would have formed one great land, but the line, accidentally breaking, the act was incomplete, and matters were left as they now are. They show a hole in the rock about two feet in diameter, which quite perforates it and in which Tangaloa’s hook got fixed.” [9]

Friday, August 30. At 3:00 p.m., Elders Durham, Welker, Jensen, Atkinson, Shill, Leonard, and myself boarded the little mission boat, which has been christened Hilatali, and sailed for the Nuku‘alofa side of the lagoon. We were going in to hold a meeting which had been appointed in the capital for the evening. The wind being favorable, we had a most pleasant sail across the lagoon, lasting a little over one hour. As the boat glided swiftly over the face of the water, the air was made to resound with the sweet songs of Zion, a number of the brethren being good singers and members of choirs when at home. We also enjoyed the usual two-mile walk through the tropical forest, or “bush,” and coconut groves and arrived at Nuku‘alofa at 5:00 p.m. We at once set to work preparing the falekai, or large dining hall, which the premier of the Kingdom of Tonga had granted us the use for the occasion. At 7:30 p.m., the appointed hour for the lecture, about sixty people, including most of the white inhabitants of Nuku‘alofa and a few from other places, had assembled, and we commenced the first Latter-day Saints meeting ever held in the Tongan capital for white people by singing, “Arise, O Glorious Zion,” etc., after which Elder James R. Welker offered a short prayer, and then the hymn “Redeemer of Israel,” etc., was sung. Next followed the lecture, as advertised, by Elder Andrew Jenson of Salt Lake City, who spoke an hour and ten minutes on the history, religion, general characteristics, etc., of the Latter-day Saints. He was listened to with very close attention and apparent deep interest throughout. “The Gospel Standard High Is Raised,” etc., was sung and benediction offered by Elder Alfred M. Durham. Among those present who expressed themselves highly pleased with the meeting was William Freskow, the German consul through whose influence partly we had obtained the hall in which to give the lecture. After the meeting, all we elders wended our way back through the “bush,” the bright tropical moon beaming beautifully upon us and lighting up our way. At 10:00 p.m., we again boarded our trusty little boat and pulled out for Mu‘a four miles away. As the wind blowed [sic] hard against us, we had to row all the way; but we enjoyed it, for we were a happy little crowd who felt truly thankful to the Lord for having heard our prayers and granted us a good meeting. After two hours of hard rowing against wind and wave, we reached the Mu‘a shore and cast anchor off the rear of the mission premises. We waded ashore, the tide being out and the water consequently too shallow for the boat to float into the little harbor, or inlet. The still hour of midnight found us once more entering the “portals” of our peaceful little mission home at Mu‘a.

Saturday, August 31. After working at historical labor part of the day, I set out for a walk through the “bush” in the afternoon, accompanied by Elders Atkinson, Shill, and Leonard. After traveling about three hours in the midst of a drenching rainstorm (against which our umbrellas afforded only partial protection), we reached the ocean on the opposite side of the island, where we obtained a good view of the neighboring island of ‘Eua, situated about eleven miles out from the southeast shore of Tongatapu. We now entered a great cave (the main object of our ramble), [10] the entrance to which is quite small and so low that one has to crawl on all fours to get in but which opens out to most magnificent grottos and chambers further in. We explored several very large rooms in which abounded curious and fantastic water formations of all sorts but whose broken and uneven floors made progress slow and difficult. An extensive lake system, containing numerous arms and strange connections, covered the lower side of several large rooms. We went in, I should judge, about five hundred feet and would have gone farther, had we possessed more lanterns. The natives claim that the cave is several miles long and relate a story of a woman who, many years ago, got lost in there but who finally succeeded in reaching the top of the ground through an opening near Mu‘a, three miles away. This is undoubtedly an exaggeration, but it is nevertheless a very interesting and extensive underground system—by far the largest cave I have ever seen. If such a cave were situated in a thickly populated country, or on a regular route of travel, it would be visited by tens of thousands of people. On our return to Mu‘a, we took another more roundabout road, in order to avoid the wet grass in the “bush,” and thus passed through the village of Havelu. Being hungry, we also helped ourselves to a niu, the native name for a coconut, and a papau, or pummy apple, called by the natives olesi, which in taste and size resembles American mush melon. We drank the milk of the coconut and ate its flesh with much relish. There is a law in Tonga which authorizes traveling people who are hungry to enter anybody’s premises and help themselves to all the fruit they can eat; but they are not at liberty to waste any or to carry any away. If Tonga lay on the way of the genuine American tramp, I am afraid that that law would be very much allured; but there are no real tramps in Tonga.

Sunday, September 1. Two general meetings were held at the mission house at Mu‘a. Only a few children attended the forenoon meeting, while a nice little congregation of adult natives attended the afternoon services and listened attentively to a discourse on the first principles of the gospel and the Book of Mormon by Elder Durham. This being the first Sunday of the month it was observed as fast day, and, in the evening at our little testimony meeting, the sacrament was administered, and all the brethren spoke. It was observed that we seven elders who had spent nearly two weeks in pleasant association together would most likely never meet again in the same place, three of us being about to depart for other fields of labor. Late in the afternoon, in company with Elder Durham, I visited the neighboring village of Alaki, situated about one-half mile southwest of the mission house. At this village stands a very large banyan tree (native name ovava), the combined trunk roots of which measure about one hundred feet in circumference. It grows partly out of the water of the lagoon and partly from the steep bank and is by far the largest tree on the island of Tongatapu.

“Jenson’s Travels,” September 13, 1895 [11]

Fagali‘i, Upolu, Samoa

Monday and Tuesday, September 2 and 3, 1895, were spent by your correspondent at the mission house at Mu‘a, Tongatapu, in writing and reading and conversing with a few natives who visited us. The Tongans are a very proud and haughty race, many of whom think themselves superior to white people. They are very sensitive to blame and great lovers of praise; and it is said that both the earlier and later sectarian missionaries learned how to take advantage of this when they wanted a liberal donation from them. Such was generally raised in special meetings called si pa‘aga, in which the solicitor, after having received money from some native, would get up and declare the fact to the whole congregation and praise the donor in the highest terms. This naturally would induce others who loved to be praised to donate liberally also and even to excel the previous giver; and this would go on till sometimes the assembly would grow wild with excitement, and many, acting from the impulse of the moment, would give away nearly all they possessed. These si pa‘aga meetings are still held and with almost the same success as formerly.

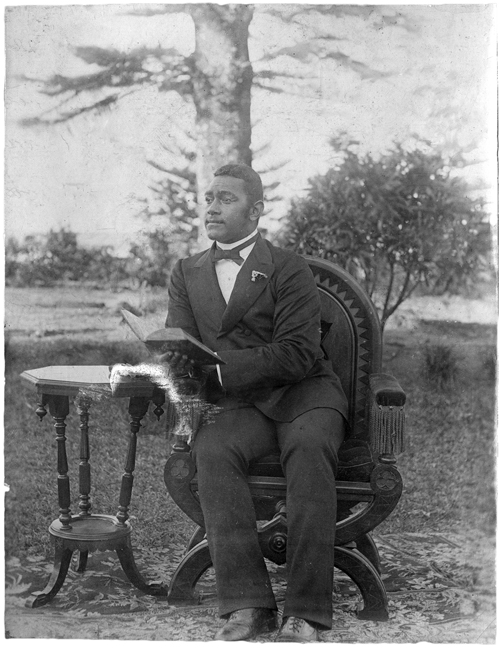

Wednesday, September 4. Elders James R. Welker and Charles E. Jensen, bound for Vava‘u, and myself bound for Samoa—accompanied as far as Nuku‘alofa by Elders Durham and Atkinson—left Mu‘a early in the morning; and, being favored with a southeasterly wind, we crossed the lagoon in about an hour. Leaving the boat at the usual place of anchorage, we walked to the capital, from whence we sent a vehicle back for our luggage. On our nearing the wharf, we noticed a great gathering of people there, and we were informed that the young king of Tonga was about to pay a visit onboard the British man-of-war Penguin, which was lying at anchor off the wharf. This gave us an excellent opportunity of witnessing quite an impressive display of royalty on a small scale. Strung along the grassy road, passing the palace, and along the jetty leading out to the pier were about one hundred men dressed in white coats and pantaloons who did service as a guard of honor for the occasion. In front of the custom house sheds, about halfway between the palace and the pier, twenty armed soldiers were stationed. They were dressed in red coats and blue pants and had dark-colored caps with a gold-colored band around them for head covering. Their leather belts with brass fastenings, together with their brass coat buttons and the brass ornaments fastened to the front of their caps, gave them quite an imposing appearance. Then there was the royal band, consisting on that occasion of eighteen members and that many instruments including the drums, which discoursed music that in sweetness and harmony could compare favorably with some American bands that I am acquainted with. After waiting a short time, the king was seen leaving the palace accompanied by five others, who walked in double file between the lines. The king, who is rather a good-looking young man (only twenty-one years old, but weighing nearly 275 pounds and measuring 6 feet 2½ inches in height), was dressed in a tight-fitting suit of navy blue, and on his head he wore a light-colored helmet, while his shoulder and breast were properly decorated as becomes genuine royalty. (Photo of King George Tupou II) He walked with a regular and firm step, carrying himself in strict military style. By his side walked Mr. Leefe, the British consul at Tonga. Immediately behind them walked Mr. James B. Watkin, the king’s special adviser and the head of the Tongan Free Church, and Tukuaho, governor of Vava‘u, while George Finau (a very stout native) and the crown prince of the kingdom, but at present the governor of Keppel Island [12], and another native chief, made up the rear. Due honor was paid His Majesty as he passed along the lines; and among others, the “Mormon” elders present on the occasion lifted their hats respectfully to the “greatest Tongan alive.” The distance from the palace to the outer end of the jetty is about a quarter of a mile, and having reached the wharf his royal highness and escort boarded the royal boat, which was waiting for them and which was manned by ten royal oarsmen and a helmsman. Just before the king stepped onboard, the ten oarsmen arose to their feet and raised their oars to the perpendicular, remaining in that position till the six distinguished passengers were seated. Then, at a given signal of the helmsman, or boat commander, the ten men as with one accord dropped their oars into their proper positions on the sides of the boat and then taking their seats commenced their very artistic and graceful rowing toward the British man-of-war, which in honor of the occasion had ordered its crew up in the yardarms, where they stood erect like so many statutes till the king and escorts had boarded the vessel. The king’s party only remained onboard the man-of-war about half an hour, when he returned in the same boat that had brought him out. I have never seen finer and more perfect rowing than that executed on this occasion by these Tongan natives. The sight was truly pleasing to the eye, and the long, white boat, flying the royal standard ahead and the Tongan flag on the mast, looked beautiful as it was propelled so systematically over the water. The party marched back the way it came, the band, the soldiers, and the guard of honor occupying the same positions as when the party went out and going through the same performance.

As the steamer Ovalau, which was due from New Zealand, had not arrived yet, we returned to Mu‘a in the evening, rowing all the way across the lagoon. In the evening Elder Durham and myself visited Mr. Lombard, one of the white merchants of Mu‘a, and an old resident of the place. We also witnessed a most beautiful total eclipse of the moon.

Thursday, September 5. Once more Elders Welker, Jensen, and myself left Mu‘a, accompanied by Elders Alfred M. Durham (who presides over the Tongan Mission) and Amos A. Atkinson, after taking final leave of Elders George W. Shill and George M. Leonard. The usual sailing and walking brought us safely to Nuku‘alofa, where we found the Ovalau lying at the wharf. After giving the parting hand to Elders Durham and Atkinson, who returned to Mu‘a, we boarded the steamer and spent the night onboard. On our arrival at Nuku‘alofa today, we saw a shark measuring eleven feet in length and weighing about five hundred pounds, which had been caught the night before. We also conversed with a native of Pitcairn Island by the name of Young, who is a great-grandson of the original Edward Young—one of the mutineers of the ship Bounty who first settled Pitcairn Island over nine [one] hundred years ago. This man, together with two companions, had just arrived at Nuku‘alofa in an American Seventh-day Adventist missionary vessel. The present population of Pitcairn Island is about 130 in number; all are adherents of the Seventh-day Adventists, though they were formerly members of the Church of England.

King George Tupou II. Courtesy of Brigham Young University- Hawaii

King George Tupou II. Courtesy of Brigham Young University- Hawaii

Friday, September 6. According to previous appointment, Elders Welker, Jensen, and myself landed and had a pleasant interview with King George (Sioasi Tupou II) at the royal palace in Nuku‘alofa, being introduced by Mr. Watkin. I conversed with the king about fifteen minutes, partly direct and partly through Mr. Watkin as interpreter. The king understands a little English but spoke it very imperfectly. I endeavored to convey to him a correct idea of Utah and her people, explained briefly our method of preaching the gospel throughout the whole world, and also told him that ten of our elders were now laboring in his kingdom. I also showed him some Salt Lake City views and a specimen of the rock of which the Salt Lake City Temple is built, all of which seemed to please him very much. After an interview with the king, we watched the preparations going on for a great native feast near the palace. The occasion was a visit of a number of singers and their friends from Ha‘apai who had just landed with their food and mats and who were now busily engaged in carrying roasted pigs, cooked ufi, kava roots, and other food from the landing to their camping ground behind the palace. The smaller hogs and lighter parcels two men would carry on poles between them, but the large hogs and the heavier articles they had mounted on a number of “sleds” consisting of forked logs or trees to which they had attached very long roots in lieu of ropes; and the men, marching in double file pulling at these natural ropes, would drag the sled over the green, grassy lawn, while they were shouting and singing their native songs in full chorus, keeping time with their feet. In this manner the men marched backward and forward between the landing and place of encampment until all the food was brought up. Every time the long double file of stalwart fellows arrived at the camping ground they were greeted and praised by the local chiefs, who had taken their position for that purpose, sitting in a long line with crossed legs near the temporary sheds which had been built for the accommodation of the visitors. The sight was truly interesting. While some of the men were only covered with their usual scanty clothing—a shirt and a waistcloth—others were loaded down with native cloth and costly mats, which they had wrapped around them until their arms would almost extend straight out from their bodies and some of the cloth drag behind them several feet. It is customary on great feast occasions for the natives to wear about their persons all the mats and cloth they own; it is an exhibition of wealth and always calls forth admiration and praise from their fellows. The women are on the lead in this regard, and we saw some of them who could hardly walk because of the immense weight of their wraps. To a people who generally prefer to go nearly naked, such a superabundance of unnecessary and awkward clothing in as hot a day as this was must have been very uncomfortable indeed. Some of the women had also anointed their heads, necks, and shoulders with coconut oil until their skin actually shone like “Rising Sun Stove Polish.” While the Ha‘apai visitors were engaged in gathering their food in the manner described, the local natives were similarly engaged in gathering hogs, kava, etc., in an adjoining lot. We counted seventy-five cooked hogs and pigs in one place alone, and it would seem that nearly all the pigs on the island of Tongatapu had been slaughtered to do justice to the occasion. This particular feast is supposed to last for a week or more, a vocal music contest between the singers of Ha‘apai and those of Tongatapu being a part of the program. But the Tongan people care more for eating and drinking than for singing. Hence the pigs and other good food form the center of attraction. It is characteristic also of the Tongans that they hardly ever kill pigs for family consumption but raise them exclusively for use at feasts.

By invitation of Captain Graham, commander of the Seventh-day Adventist brigantine Pitcairn, which was lying off the wharf, we boarded that vessel, which hails from San Francisco and is bound for the Fiji group. We remained onboard for some time conversing with the captain, who gave me some literature and informed us that the numerical strength of the Seventh-day Adventists throughout the world is about 35,000, with headquarters at Battle Creek, Michigan. The Pitcairn, which is the only vessel owned by the society, was built in America in 1890 and named in honor of the island whose name it bears. We also boarded the Norwegian brig, Nebo of Tinstad, and had an interesting conversation with the captain, Jens Johannesen. In telling him that we lived in Utah, he exclaimed instinctively, “Men det er jo hvor Mormonerne bo.” “Yes,” was our reply, “and we are Mormon elders.” “Ja, sa,” he said good-naturedly enough but with an expression that suggested that though he was pleased to meet two of his Scandinavian cousins far away in the tropics, he would have been better pleased if we had not been Mormons.

At 4:00 p.m., Elders Welker, Jensen, and myself, again boarded the steamer Ovalau, and a few minutes later we were under way, sailing for Ha‘apai about one hundred miles away. After passing several small islands, one of which was Malinoa, where a number of natives were executed a few years ago for making an attempt to assassinate Premier Baker, we found ourselves in the open ocean, with a smooth sea and a pleasant ocean breeze flowing from the southeast.