The Fijian Islands, July 1895–August 1895

Reid L. Neilson and Riley M. Moffat, eds., Tales from the World Tour: The 1895–1897 Travel Writings of Mormon Historian Andrew Jenson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 89–111.

My first impression on meeting the Fijians when the Miowera arrived in the Suva Harbor was rather an unfavorable one. Their appearance seemed to indicate partly African origin very plainly, and this idea still obtains with me; though their intermarriage with their Polynesian neighbors on the east entitles them to some of the blessings vouchsafed unto the promised seed—the house of Israel. I should be very pleased to see a mission established here by the Latter-day Saint elders, though I have reason to believe it would require an extraordinary effort to make it a success. The Fijian language is not hard to learn, a young intelligent elder, assisted by the Spirit of God, would be able to acquire it in a few months; and this would certainly be the first step to be taken for reaching the natives successfully.

—Andrew Jenson

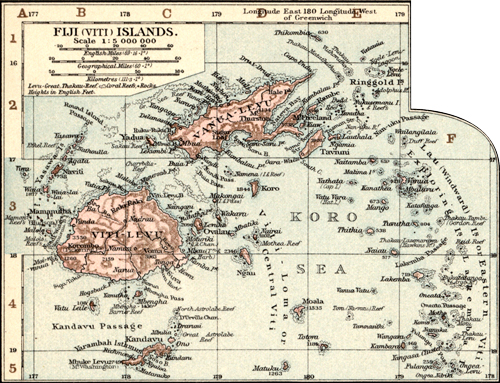

Fiji, The Times Atlas (London: Times, 1895), 113

Fiji, The Times Atlas (London: Times, 1895), 113

“Jenson’s Travels,” August 8, 1895 [1]

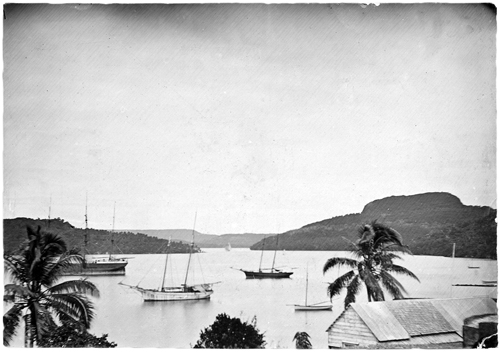

Suva, Viti Levu, Fiji Islands

Friday, July 26. At 2:00 in the morning one of our members, a Chinese brother, called at the mission house at Honolulu and announced the arrival of the Miowera, but we soon learned that Brother Noall’s successor was not along. There were, however, four other elders onboard bound for the Australasian Mission, namely, James Clayson of Payson, Utah; David Lindsay of Bennington, Bear Lake County, Idaho; and Wallace C. Castleton and Horace W. Barton of the Twenty-first Ward, Salt Lake City. These brethren visited the mission house at Honolulu early in the day, after Elder Dibble and myself had paid them a visit onboard. Early in the forenoon, the native Saints began to call to say goodbye, and at 10:30 a.m. I left the mission house in Sister Makanoe’s carriage and went onboard an hour later. Quite a number of the Saints came down to see me off, among whom was Sister Makanoe, who decorated me with a very liberal supply of flowers, lace, and greens—a token of esteem and love with the Hawaiian people. After taking a most affectionate leave of Brother and Sister Noall, Brothers Edwin C. Dibble, and George H. Birdno (the latter having come with a team from Laie), and the native Saints, I bid farewell to the shores of Hawaii and steamed out of Honolulu Harbor at 12:30 p.m., bound for Fiji. Some of the Saints remained on the wharf waving their handkerchiefs as long as we could see each other. I shall never forget the native Saints of Hawaii. God grant that the promises made to their forefathers long ago may speedily be fulfilled. I watched the shores of Oahu vanish out of sight with a somewhat heavy heart, then conversed with my missionary companions till a late hour and retired to my stateroom, enjoying a good night’s rest.

Saturday, July 27. Though the weather was fine and the Miowera glided smoothly over the waters of the great Pacific, I am not well all day, the motion of the vessel causing a feeling which, had I yielded to it, would have meant seasickness. At noon when the observations were taken, we found ourselves in latitude 17˚8´30˝ N, longitude 160˚33´30˝ W. Distance from Honolulu 292.5, and to Suva 2,509.5 knots or nautical miles.

Sunday, July 28. All the missionaries attended Church of England services, conducted by the captain, in the forenoon; and in the evening commencing at 8:00 p.m., we held meeting in the social hall; nearly all the passengers were in attendance and paid good attention throughout. I spoke nearly one and a half hours on the history of the Mormon people and the principles of the gospel. Brother Castleton led the singing and performed on the piano. We conducted our meeting in the usual way. At noon the ship’s log read: latitude 12˚43´00˝ N, longitude 163˚12´00˝ W; distance made (since yesterday) 307 knots; distance from Honolulu 599.5; to Suva 2,202.5 knots.

Monday, July 29. I spent the day writing and conversing with the passengers about religion and the Bible, a Dr. Collingwood of Sydney, Australia, taking issue against me in most every point. The day was very warm. At noon the log extract read: latitude 8˚25´45˝ N, longitude 165˚40´15˝ W. Distance sailed during the last twenty-four hours, 295.4 knots. Distance to Suva 1,907.1; from Honolulu, 894.9 knots.

Tuesday, July 30. A seabird called by the sailors a mollymawk flew about the forecastle of the vessel for a long time and occasionally came so near that we could have perhaps grabbed it with our hands, while a number of us stood watching it with considerable interest. Anything to kill the monotony of a sea voyage! A flying fish also jumped onboard and was caught by Elder Clayson. At noon we were in latitude 3˚45´10˝ N, longitude 167˚53´45˝ W. Distance sailed since yesterday at noon, 310.1 knots; distance from Honolulu, 1,209; to Suva, 1,599 knots. Tonight I witnessed one of the most beautiful sunsets I have ever seen. All the natural colors known to humanity were exhibited in their supreme grandeur and beauty upon the overhanging clouds and upon the bosom of the ocean. A cool, soothing breeze made the evening very pleasant, and I enjoyed it immensely while I spent the time in conversing with my fellow missionaries and the passengers. Though we are so near the equator, it is not very hot.

Wednesday, July 31. About 8:00 in the morning we crossed the imaginary line known in our geographies as the equator, though the sun had appeared to us north of the zenith at noon for several days, this being northern summer and southern winter. Thus, for the first time in their lives, five elders from the headquarters of the Church passed from the northern to the southern half of the world. At noon the log read: latitude 0˚50´00˝ S, longitude 170˚37´45˝ W. Distance during the past twenty-four hours, 319.7 knots; distance from Honolulu, 1,525.7; and to Suva, 1,276.3 knots. At about 11:00 p.m. we passed within a short distance of the little coral island known upon the maps as Mary’s Island—one of the Phoenix group. It is not inhabited.

Thursday, August 1. About 7:00 this morning we passed Hull Island, another coral island belonging to the Phoenix group; it is at present inhabited by a number of Guiana gatherers, and like Mary’s Island it belongs to the Phoenix Guiana Company. Hull Island, which is about four by five miles in size, is 112 miles from Mary’s Island and 1,767 from Honolulu. We passed it on our starboard side, distance about two miles. At noon when the usual observations were taken, we were in latitude 5˚30´30˝ S, longitude 172˚44´45˝ W. Distance sailed since yesterday at noon, 313.4; distance to Suva, 963; and from Honolulu 1,893.1, knots.

Friday, August 2. I spent most of the day writing letters, reading, and conversing with the passengers. At noon the ship’s log showed: latitude 10˚2´15˝ S; longitude 175˚28´30˝ W. Distance since yesterday, 316.1; distance to Suva, 646.9; and from Honolulu, 2,155.2 knots.

Saturday, August 3. Early in the morning the outlines of two mountainous islands, Alofi and Futuna, which are known upon the charts as Hoorn Islands, [2] could be seen very plainly on our starboard side, and about 11:00 a.m. we were sailing opposite Alofi, though at a distance of fifteen miles. Alofi is about six miles long by about three miles wide, and its highest point is 1,200 feet. Futuna is eight miles long by five in breadth, and its highest mountain peak has an elevation of about 2,500 feet above sea level. Both islands are inhabited. At noon we were in latitude 14˚41´15˝ S; longitude 177˚47´00˝ W. We had sailed 309.8 knots since yesterday at noon, and we were now only 337.1 nautical miles or knots from Suva but 2,465 from Honolulu. At 11:00 p.m. we passed the Wailagi Lala lighthouse on our left, which is the first point of the Fijian group; it is 174 nautical miles from Suva. During the night we passed through the Nanuku Passage, with islands on the eastern group of the Fiji Islands on both our right and left. On arising the next morning, we were informed that there would be no Sunday onboard the Miowera this week, as we had crossed the 180th meridian of western and eastern longitude during the night. This always meant the losing of a day in sailing west and the gaining of one going east. Thus instead of Sunday we were told that it was Monday.

Monday, August 5. Very well. At 8:00 a.m. we were sailing close to the shores of the island of Batiki, on our starboard side, while on the opposite side the heights of the islands of Gau and Nairai, some distance away, added fresh beauty to the scenery. Other islands were in sight, among which Viti Levu, the largest island of the group, the outlines of a portion of which appear directly ahead. Batiki is 56 miles from Suva. At 12:45 p.m. the Miowera cast anchor off the Suva wharf, and at 1:50 p.m. I landed with Mr. Joske, agent for the Canadian-Australian Steam Ship Company at Suva. He introduced me at once to Mr. A. M. T. Duncan, the Union Steam Ship Company’s agent, who offered me a free passage to New Zealand via Samoa and Tonga if I stopped over to go with their ships. The first steamer would leave for Tonga about the 15th and another for Samoa about the 28th of the present month. Though this delay was not on my original traveling program, I decided to stop and endeavor to spend a short time at Fiji to the best possible advantage. Most of the passengers of the Miowera landed for a few hours at Suva, among whom were Elders Clayson, Lindsay, Castleton, and Barton. About 4:15 p.m. I bid these brethren goodbye as they returned to the ship to continue their voyage; and I was thus left alone among the strange and mixed population of Fiji; after watching the Miowera pass out of the harbor and disappear beyond the coral reef, I began to make inquiries about lodgings. I rented a room at the rate of seven shillings per week from a Mrs. Johnson, on Gordon Street, near the center of the town, and moved my effects there at once. After taking an evening ramble and conversing with a number of the white inhabitants, I retired to my room and spent my first night in Fiji in comfortable sleep.

Tuesday, August 6. (Map of Fiji from Times atlas, 1895, p. 113) I spent most of the day making acquaintances in the town of Suva. Thus I introduced myself to the proprietor and editor of the Suva Times, Mr. G. L. Griffiths, who subsequently showed me several small favors. James Stewart, colonial secretary, who sent me a package of government literature to my room, Mr. G. Gardner, who gave me access to the only library in the town, and a number of others. I also spent some time reading and copying in the library and in the evening attended a debate in the library on the question, “Is war ever justifiable?” on which all concerned took the affirmative.

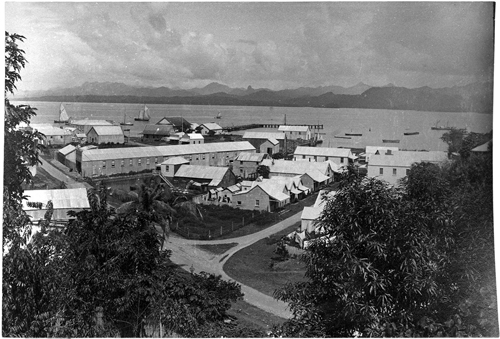

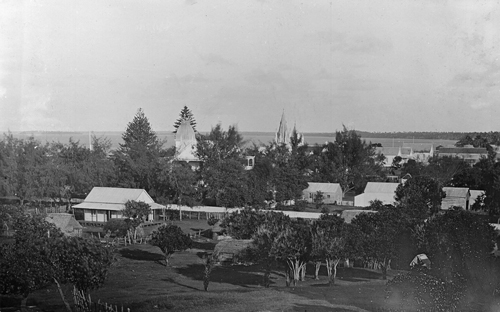

The town of Suva, the capital of Fiji, is pleasantly situated on the Suva Bay, on the south coast of Viti Levu. The principal street, called Victoria Parade, faces the harbor and contains nearly all the business houses, while the resident part of the city occupies the rolling hillside which slopes westward to the bay.

The inhabitants consist of government officials, merchants, and other businessmen, but the majority are Fijians. There are also some Indians, or coolies, imported as contract laborers, and some natives of the Solomon Islands, the Carolines, and other groups; there is also a sprinkling of Samoans and Tongans. Nobody could tell me the exact number of inhabitants of Suva, but it appears not to exceed 2,500, of which about 800 are whites. Suva is distant from Sydney, Australia, about 1,700 miles; from Auckland, New Zealand, 1,200 miles; from Honolulu, Hawaii, 2,700; and from New Caledonia, about 650.

The Fiji group consists of two large islands, Viti Levu (Large Viti) and Vanua Levu (Large Land), and upwards of 250 smaller ones, ranging in size from over 200 square miles (Taveuni) down to islets consisting of an acre or less of barren rock. All the islands make up an area of 7,451 miles, of which 4,112 miles belong to the Viti Levu, the largest island of all. This island is about 97 miles long from east to west and 67 miles across from north to south at its broadest part and is oval in shape. Its climate varies very considerably in different parts; generally speaking, the southern and eastern districts and greater parts of the interior receive plenty of rain, while the northern and western parts, especially the coastlands, are considerably drier. The mountain ranges are highest in the interior, where they attain a mean height of about 3,000 feet. The southeast trade wind prevails for about two-thirds of the year; it comes from the ocean, laden with moisture. The average yearly rainfall at Suva is about 105 inches; farther inland and closer to the mountains it is 145 inches. The Sigatoka is the most important river in the middle and southern parts, and Rewa in the eastern half of the island. There are other rivers of less importance. The Rewa is by far the largest of all the rivers in the group. In the northeastern part of the mountain ranges on Viti Levu lie the sources of numerous water courses, most of which make direct for the north coast and from either the Wainibuka or the Wainimala rivers. These after very tortuous courses of some thirty miles meet to form the Rewa. The length of this river is about fifty miles, and its general direction is toward the southeast; it drains about one-fourth of the entire island of Viti Levu. Vanua Levu, the second largest island in the Fijian group, contains an area of 2,432 square miles; the third in size is Taveuni with an area of 217 square miles. Both Viti Levu and Vanua Levu are very mountainous, the latter having peaks which rise to about 5,000 feet above sea level. They are, like the Hawaiian Islands, of volcanic origin, well wooded and extremely fertile. The east, or weather, side is the most luxuriant and teems with a dense mass of vegetation, huge trees, innumerable creepers, and epiphytal plants. No break occurs in the green mantle spread over hill and dale except where such is affected by man. On the lee side the aspect is very different. Here one meets with a fine grassy country which here and there is dotted with screw pines. The dense vegetation is thoroughly tropical in aspect. On the mountains at an elevation of about two thousand feet are found hollies and many other kinds of trees, with bright-colored orchids and delicate ferns and mosses. There are many perfumed barks and woods, but sandalwood is confined to the southwestern parts of Vanua Levu, where it has been scarce for many years. Rats are plentiful in Fiji and were probably introduced by Europeans, and the dog, pig, and fowl were domesticated when the islands were first visited by the whites. Birds are tolerably numerous and resemble those of the Tonga and Samoa group. Lizards are comparatively abundant and varied, but there are only two kinds of snakes, where there are several kinds of tree frogs.

The Fiji Archipelago lies east of the New Hebrides, between 16˚ and 20˚ S latitude and 177˚ E longitude and 178˚ W of Greenwich. The 180th meridian passes through the group and nearly through the center of the island of Taveuni; but all the inhabitants keep the same time for convenience sake, the eastern group conforming to that which obtains on the main islands, which are west of the meridian named. Fiji has many good natural harbors. Each one is surrounded with a barrier reef through which numerous openings lead to safe anchorage, protected by a natural breakwater.

Fiji is one of Great Britain’s Crown colonies, the affairs of which are administered by a governor, appointed by the Crown and Executive Council. There is also a legislative council under the presidency of the governor, composed of the chief justice and other heads of departments as official members, and an equal number of unofficial members. The present governor, Sir John B. Thurston, is an old resident of Fiji, but new as to title. He is well liked by some and hated by others; but as His Excellency is absent from the islands at present, I have been unable to see him and thus form an opinion from his personal acquaintance.

The population of the colony according to the official census taken April 5, 1891, was 121,180. Of these 2,036 were Europeans; 1,076, half-castes; 6,469, Indians; 2,267, Polynesians (mostly from the Solomon Islands and Caroline group); 105,800, Fijians; 2,219, Rotumans; and 314 others. According to a census taken in 1881, the native population then numbered 114,748. This shows a decrease in ten years of 8,948; but it is claimed that the census of 1891 is not correct, that there are more natives than the returns showed. “The decrease,” according to a statement made in a handbook to Fiji published by the government in 1892, “is due almost entirely to the high mortality among the infants, the precise cause of which it is difficult to specify. Among other reasons advanced are the comparatively weak maternal feeling of Fijian women; the introduction of new diseases, such as measles, whooping cough, influenza, etc., with which the natives cannot cope; and the disappearance of many of their old necessities and social customs which tended to ensure the close care of infant children.

“The Fijians are a well-made, stalwart race, differing in color according to the location in which they live. The mountaineers show the frizzed hair and dark color of the Melanesian, while their neighbors on the coast betray a strong mixture of Malayo-Polynesian blood.

“In character they have been described as full of contradictions, but perhaps the unfavorable opinion of them is due to the fact that they are incapable of feeling any enduring gratitude or lasting attachment. On the other hand, they are very tractable, docile, and hospitable; and in war, when following their chiefs or European leaders, they have shown themselves brave and loyal.

“They have now all embraced the outward observances of Christianity. Having few wants and blessed by nature with the means of supplying them, they are not spurred on to exertion by the want of money, and they dislike prolonged and sustained work; but in their own fashion they are industrious.

“They are by nature intensely conservative and slow to discard their own customs in favor of those of civilized peoples; but the gradual use of European articles for which money must be procured has of late years led many of them to seek work on the plantations, and the supply of native labor is at all times equal to the demand. For clearing new ground or shipping cargo, they are by some settlers preferred to coolie (Indian) or Polynesian laborers.

“The government has aimed at disturbing their social and political organization as little as possible and has hitherto most successfully controlled the people through their chiefs. The native laws are administered by native agents under supervision of European officers, and, although native officials make mistakes, the people on the whole have shown themselves worthy of being allowed a share in their own government. It would be impossible, without incurring enormous expense, to replace the chiefs by white officials, and the experiment would be unsuccessful. The nonrecognition by the government of the leading chiefs would not abate their influence in the least, and, in place of the loyal assistance they now render to the government, they might become the foci for discontent and opposition.

“At the present time there is not a more law-abiding community in the world than these former savages; and, with greater attention to sanitary matters and the attainment of a higher moral standard, it is hoped and believed that the Fijians will be an exception to the alleged rule—that before the white race the dark must decay and disappear.

“Certain changes in the habits and in the food of the people must however be effected, and every attention is given by the government to this end.” [3]

Another authority speaks of the Fijians as follows:

“The Fijians are a dark-colored, frizzy-haired, bearded race with tall and muscular bodies, much superior to the Papuan race inhabiting the islands westward, both in regularity of feature and in degree of civilization. They exhibit, however, a considerable amount of intermixture with the Crown Polynesians of Tonga and Samoa, who have long ago established colonies in the Fiji Islands, and have to some extent modified both the customs and the language of the Fijians. Yet they are generally believed to belong to the Melanesian race, and differ from their Polynesian neighbors not only in their scanty dress, but in using the bow and arrow and in making pottery—both arts being foreign to the true Polynesians.”

My first impression on meeting the Fijians when the Miowera arrived in the Suva Harbor was rather an unfavorable one. Their appearance seemed to indicate partly African origin very plainly, and this idea still obtains with me; though their intermarriage with their Polynesian neighbors on the east entitles them to some of the blessings vouchsafed unto the promised seed—the house of Israel. I should be very pleased to see a mission established here by the Latter-day Saint elders, though I have reason to believe it would require an extraordinary effort to make it a success. The Fijian language is not hard to learn, a young intelligent elder, assisted by the Spirit of God, would be able to acquire it in a few months; and this would certainly be the first step to be taken for reaching the natives successfully. [4]

The Wesleyan Methodists were the first to introduce their form of Christianity to Fiji. This was done in 1835 by the Reverend David Cargill and the Reverend William Cross. They now have churches or meetinghouses in nearly every village in the group. According to the official report of the Australian Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society for the year ending March 1894, they had in Fiji at that time 846 churches; 475 other preaching places; 11 missionaries; 69 native ministers; 52 catechists; 1,117 teachers; 2,325 schoolteachers; 2,064 local preachers; 3,680 class leaders; 21 English members; 30,583 native members; 5,299 native members on trial; 1,671 Sabbath schools; 2,377 Sabbath schoolteachers; 36,675 Sabbath scholars; 1,671 day schools; 36,907 day scholars; altogether 99,031 adherents or attendants in public worship. Besides the Bible and a grammar and dictionary, the missionary society has published seven or eight books in Fijian, and they are now (1895) also publishing a small periodical at Bayedeted by the Reverend A. J. Small.

The Roman Catholics founded a mission in Fiji in 1844, and they have now about nine thousand adherents. The missionaries—fourteen in number in 1892—are of French nationality. The mission supports an orphanage for the children of Roman Catholic parents and has established schools for European children both at Suva and Levuka.

The Church of England commenced operation in Fiji in 1870 and now has churches in both Suva and Levuka. There is also a Presbyterian church at Suva; and there is plenty of element out of which to make converts for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints.

“Jenson’s Travels,” August 9, 1895 [5]

Suva, Viti Levu, Fiji

Wednesday, August 7. I started out from my lodgings in Suva, Fiji, for a morning walk along the bay, and the day being cool and pleasant I continued on past the colonial prison and the Suva graveyard, the latter being situated about two miles north of the center of Suva, near the point where the Tamavua River puts into the bay. The stream looking so clear and beautiful, I yielded to the temptation of taking a bath, but found the water rather cold, which is no wonder, as this is Fijian winter. The Tamavua River is quite wide at its mouth, but is not very long. From that stream the Suva waterworks obtains its supply of water.

Suva, Fiji. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Suva, Fiji. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Through the courtesy of Henry Millen, Esq., the superintendent of all the government prisons of the Fijian group, I was shown through the entire prison premises by the jailor, Mr. Fred Sabbin. The ground covers several acres, and there are at present 175 male and 9 female offenders incarcerated. Of the male convicts, three are whites and one is a half-caste; the rest are Fijians and coolies (natives of Hindustan and the East Indies). Only eight are imprisoned for life; most of the others are in for short terms, and about half of them are sexual offenders—people who have been convicted of adultery and fornication against which offences there are very stringent laws. Formerly, when a man seduced his neighbor’s wife or daughter, the husband or father of the woman thus wronged would watch for an opportunity to club the offender to death, this being the custom of the country; but since the English fairly got control of the government this custom has been abolished by law, and imprisonment, varying in length from one to twelve months, substituted in lieu thereof. Unfortunately, this law is inoperative so far as the whites are concerned. Mr. Sabbin was of the opinion that white offenders, of which there undoubtedly are many, had succeeded so far in clearing themselves by paying certain amounts of money, as none of them had as yet been convicted or sent to jail for sexual crimes. The officers of the prison—there are at present a large number of native sub-officers, two of whom are women—sometimes have to resort to stringent measures in order to preserve peace in the household. Thus I was shown a regular flogging post to which offenders occasionally are bound, while their backs are being lashed with a nine-forked prison thong. The number of lashes inflicted varies all the way from two to twenty and are administered by a powerful native guard while the victim is securely tied to the post by the wrists and ankles, his body leaning forward at an angle of about forty-five degrees. I only saw one prisoner in chains; he was a desperate Indian, or coolie, who tried to escape from the jail a short time ago. The great majority of the prisoners sleep in a roomy and well-ventilated bunkhouse, while the worst criminals are locked up at nights in separate cells, which are prepared in a small adjacent concrete building. The women prisoners occupy a small house by themselves; and the Europeans also occupy separate quarters. All able-bodied prisoners have to work on the outside about eight hours a day. They are mostly employed in making roads and around working in the government buildings and in the harbor.

While strolling along in the neighborhood of the graveyard, I suddenly came upon a small party of natives armed with long, sharp-bladed knives. For a moment all the horrors of cannibalism rushed to my mind; but as they simply smiled and shook their heads as I addressed them in English and made no move toward seizing me, I soon breathed more freely and also discovered that their long knives were intended for cutting grass instead of human beings. As they could understand neither English nor Danish, neither my very limited stock of Hawaiian words—and their sounds failing to make me either wiser or better—we parted with smiles all around, and after walking a short distance I sat down by the road side and read the following from Stanford’s Compendium and Geography of Travel: [6]

“The manners and morals of the Fijians are in many respects those of a civilized people; yet perhaps nowhere in the world has human life been so recklessly destroyed or cannibalism been reduced to such a system as here. Human flesh was . . . the Fijian’s greatest luxury, and not only enemies or slaves, but sometimes even wives, children, and friends, were sacrificed to gratify it. At great feasts it was not uncommon to see twenty human bodies cooked at a time, and on the demand of a chief for ‘long pig,’ which is their euphemism for a human body, his attendants would rush out and kill the first person they met rather than fail to gratify him. No less horrible were the human sacrifices which attended most of their ceremonies. When a chief died, a whole hecatomb of wives and slaves had to be buried alive with him. When a chief’s house was built, the hole for each post must have a slave to hold it up and be buried with it. When a great war canoe was to be launched or to be brought home, it must be dragged to or from the water over living human beings tied between to plantain stems to serve as rollers. Stranger still and altogether incredible, were it not vouched for by independent testimony of the most satisfactory character, these people scrupled not to offer themselves to a horrible death to satisfy the demands of customs or to avoid the finger of scorn. So firm was their belief in a future state in which the actual condition of the dying person was perpetuated, that on the first symptoms of old age and weakness, parents with their own free consent were buried by their children. A missionary was actually invited by a young man to attend the funeral of his mother, who herself walked cheerfully to the grave and was there buried; while a young man who was unwell and not able to eat was voluntarily buried alive because, as he himself said, if he could not eat he should get thin and weak, and the girls would call him a skeleton and laugh at him. He was buried by his own father; and when he asked to be strangled first, he was scolded and told to be quiet and be buried like other people and give them no more trouble; and he was buried accordingly.”

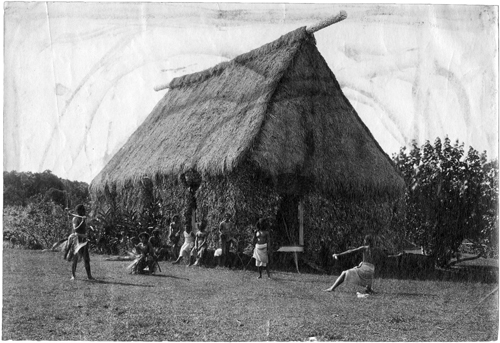

Thursday, August 8. I took a long walk along the beach and around the peninsula on which Suva is situated, visiting on my way the large and commodious native government building erected for the accommodation of those Fijians who are in the employ of the government. There are quite a number of these buildings, and nearly all the male occupants have the title Ratu (chief) prefixed to their names, some of them being members of the royal family. As most of them could speak English, I had no trouble to introduce myself to some of the leading men who in turn introduced me to others. Thus I became acquainted with Kadavu Levu, a grandson of Cakobau (pronounced “Teakombat”) the former king of Fiji, and his two lady cousins, also grandchildren of the late king, who were there on a visit. The oldest of these girls, whose name is Letio (Lydia) Cakobau, ranks as one of the prettiest women among the Fijians; she is nineteen years old and about to be married to a young chief at Rewa. Her sister, Teimumu Vuikaba, seventeen years old, is also a handsome woman for a Fijian. Both rank as princesses. Through the courtesy of Kadavu Levu, Mataitinu, the doctor, and other leading natives, I was taken into several houses and introduced to a number of families, who all seemed very comfortable and everything about their dwellings are tidy and clean. Some of the houses are 40 feet long by 25 feet wide and very strongly built. The interior is all one room, but often as many as half a dozen doors open to the outside. The floors are all covered with mats, and that part which constitutes the bed is generally raised a foot or so above the rest of the floor.

Native Fijian house. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Native Fijian house. Courtesy of Church History Library.

In my walk I passed a large gang of prisoners working on the road, for which some were quarrying rock and others were packing these rocks on their heads from the quarry or end of tramway to such parts of the road as needed them. It was a strange sight to see this long string of almost naked men walking in single file with their heavy burdens; and it reminded me very much of the pictures I have seen representing the children of Israel in bondage in Egypt. Most of the prisoners were Indians, but there were also quite a number of Fijians.

Further on I came to an Indian village containing about two hundred families, who live in small, inconvenient, and dirty huts. They are people who were brought into the country as contract, or indentured, laborers and who, after serving their five years as such, are trying to raise rice or do something for a living till another five years have passed, when they are entitled to a free passage back to India. I was told that most of them avail themselves of this opportunity, not being pleased enough with Fiji to make it their permanent home. Finding a young fellow who could talk a little English, I was piloted by him into several houses, where I had an opportunity of studying for myself the interior arrangements of the houses of these unfortunate people. In going through the village, I seemed to arouse considerable curiosity, as people were peeping out from almost every door; but I was not molested by anyone. I heard considerable boisterous language used in different places, and my guide informed me that a general quarrel was taking place and that it was an almost everyday occurrence, the Indians being a very quarrelsome race. One little man who came running through the village at full speed seemed to be at war with all the rest, as he “jawed” right and left and shook his fist vehemently at some women who seemed to make sport of him. The Indians are a very small race of people being in this respect opposite to the Fijians, who are a tall and strongly built specimen of humanity. The Indian women are great hands for ornamenting their persons. They decorate their ears, noses, necks, arms, waists, fingers, ankles, toes, etc., with all sorts of bracelets, chains, and rings. These are sometimes made of gold and silver, and in other instances of brass and other cheap materials. One woman, whose curiosity led her to come up close to me when I had sat down to rest on the beach, was almost covered with English silver money through which holes had been bored and then tied to cords of various lengths to suit different parts of the limbs and the neck. After visiting the Indian village, which is situated on the opposite side of the peninsula from Suva, I walked across the intervening hills to the latter place, a distance of about two and a half miles, being quite tired after my day’s ramble, though I had only walked about eight miles; but the day was hot and sultry, and a man can’t walk in a tropical country the same as he can in a colder climate.

“Jenson’s Travels,” August 11, 1895 [7]

Bau, near Viti Levu, Fiji Islands

Friday, August 9. The most important part of the island of Viti Levu is perhaps the region of country lying on and adjacent to the Rewa River, as it abounds with large sugar plantations and flourishing native villages. Hence I decided to pay a visit to that part of the island, and with this view boarded a steam launch, on which Messrs. Brown and Joske kindly gave me free transportation. We sailed from Suva about 3:30 p.m., and after rounding the Suva Point, we made direct for the Union Steam Ship Company steamer Taupo, which lay at anchor in the Laucala Bay, six miles from Suva, loading sugar from the Nausori Mill to take to New Zealand. We lay to and waited for the east [last?] sugar to go onboard, as the launch was to take the three lighters which had brought the sugar to the steamer back to the mill at Nausori. When the job was finished it was dark; but our Fiji captain thought he could find his way in the darkness over the sandbar and up the river, so he hitched onto the three lighters, or flat boats, and started for Nausori; but he had not gone very far till he found his little craft aground, and it took nearly two hours to get afloat again, when it was decided to return to the Taupo, and tie to for the night. This was accordingly done, and I, together with a few other passengers who were going up in the launch, slept onboard the Taupo all night.

Saturday, August 10. Bright and early the Taupo lifted her anchor and started for Suva, leaving our little launch with her three lighters adrift without steam, the native crew having overslept themselves, so that the fireman had neglected to fire up his engine in proper time. However, sufficient steam was soon gotten up to keep in course; and we proceeded on our way to the Laucala mouth of the Rewa River, through which we entered and were then sailing between the wooded banks of that remarkable stream. The Rewa River reaches the ocean through several channels, a delta having been formed at its mouth in ages past; but the most important, though not the largest of its mouths is the Laucala branch, owing to its being the shortest waterway between Suva and the Rewa District, the most populous and best cultivated part of Fiji. The place where this branch breaks away from the main river is called Hellsgate, which is a difficult narrow to pass through without running aground. A little further on we passed (on our right) the town of Rewa, which is the largest native town in Fiji; it has a Roman Catholic chapel and also a Wesleyan Church. The native men are known as good canoe builders, and the women make some of the best crockery ware in the whole group. Opposite this town the river is about 400 yards wide, and it reminded me of the Mississippi, in America. It was certainly strange to find oneself sailing on a river of such a size on an island less than one hundred miles across. Continuing our course up the Rewa, the land on both sides of the river continued flat, and is cultivated by Europeans or natives nearly all the way up to Nausori, where the first hills are met with.

One of these standing on our left as we went up was pointed out to me as Baker’s Hill, it being the place where a Wesleyan missionary of that name resided with his family, where he on a trip to the mountains was killed and eaten by the natives.

We arrived at the Nausori Sugar Mills, twenty-four miles by water from Suva, at 10:00 a.m. Here I was introduced to E. W. Tenner, Esquire, general manager of the Colonial Sugar Refining Company’s interests in Fiji, and H. H. Thiele, head accountant for the company at Fiji, to whom I had a letter of introduction from Suva. I was well received, and a room in the house occupied by Mr. Thiele and Mr. William Wilson, the chief engineer of the Nausori Mill, was placed at my disposal. Mr. Thiele is a Dane by birth and speaks his native language fluently. He also being a man of education and literary ability rendered me efficient service during my pleasant temporary stay at Nausori, and from articles written by him to different periodicals I have culled a number of items used in my correspondence to the News in Fiji affairs.

The Nausori Sugar Mills are located in the left bank or east side of the Rewa River, about one-fourth miles above the native village of Nausori. It is one of four mills in Fiji owned by the Colonial Sugar Refining Company, whose headquarters are at Sydney, Australia. Besides the four mills in Fiji (three at Viti Levu and one on Vanua Levu), the same company owns seven mills and four refineries in Australia and one refinery in New Zealand. E. W. Tenner is general superintendent of all the company’s property on Fiji, assisted by William Berry as general manager on the Rewa River. At Nausori, Mr. Henry T. Moltke, a native of Køge, Denmark, is the general manager of the plantation, and has charge of something like 850 laborers, including both sexes, mostly Indians or natives of Hindustan, who have been imported under contract for working under [sic] the plantation. These Indians live in quarters built for their accommodation adjacent to the mill, and in other parts of the plantation. The large number of laborers are divided up into convenient working companies, which are placed in change of sirdars (Indian name for foreman), for plowing, harrowing, planting, weeding, stripping, cutting, packing, loading, and hauling, etc.

The women and weaker men do the lighter work, such as weeding and stripping. The company works about fifteen hundred acres of land at Nausori, from which about one-fifth of the cane used at the mill is obtained; the other four-fifths are raised on other plantations owned by the company at different points up and down the river and by private planters. Among the latter are a number of Indians, who have served their five years’ term and are thus free to do for themselves. They lease land from the company on which they raise their cane. The wages paid the average male contract laborer is one shilling per day or per task, which is equal to a day’s work. Women only receive nine pence per day. On this they board themselves; but house, room, wood, etc., is furnished them free. How in the world these poor creatures can save money on such allowances at that mill perhaps will always remain a puzzle—to an American at least—but the facts are that thousands of pounds are annually shipped to India by these same contract laborers, who are working for a shilling or less per day. Certainly their wants are few; their food is cheap, and their clothing, too, their apparel consisting merely of sufficient linen to cover their bodies; they always go barefooted.

At the mill Paul Seelinger, a young intelligent German, is the manager and head chemist. He has charge of the sugar making, while Mr. Wilson, the chief reengineer, is responsible for the machinery. Under them are a number of white assistants, including mechanics and firemen, and nearly 150 Indian laborers. Until recently when part of the machinery was removed to another place, the Nausori Mills was the largest sugar-mill establishment in the southern part of the world. At the present time from 4,600 to 4,800 tone [sic] of cane are ground up per week, which produces from 400 to 500 tons of brown sugar. It has to be sent to refineries for final treatment. In 1894 about 118,000 tons of cane were used at the Nausori Mills. Three crops of cane are obtained after one planting; the first crop matures in fourteen months, the second and third in twelve months each. About twenty-five tons to the acre is an average yield to a crop, which is only about one-half of what can be raised in the Hawaiian Islands. But, then, there is no irrigation at Nausori.

Mr. Seelinger and Mr. Wilson conducted me though the mill and took great pains to explain to me the scientific and practical work of sugar making in Fiji; but as the process is the same as in other parts of the world, I shall forego a technical description.

Mr. Wilson also conducted me through the Indian laborers’ quarters near the mill. There are twenty-two long, lumber, windowless houses, with iron roofs, divided into apartments of 10x12 feet. One of these rooms is assigned to a family, or in case of single men, three of these to a room. Quarrels and contentions are very frequent in these quarters. The greatest difficulties seem to arise from the fact that the men don’t know their own wives; at least they don’t always act as though they did. Only about three months ago a man actually beheaded his wife who had been untrue to him. He was arrested, tried, and sentenced to be hung, but his sentence was subsequently commuted to imprisonment for life, and he is now an inmate of the colonial jail at Suva.

The success of most industries in Fiji depends materially on the possibility of getting cheap labor. There are three classes of colored laborers, viz., Fijians, Polynesians, and coolies. White men rarely work in the field; they are mostly employed as overseers, mechanics, mill hands, etc. In order to obtain Fijian laborers the planters have to enter into a special contract with the chiefs or magistrates of the various villagers from which the laborers are wanted. The planter has to pay twenty-six shillings in taxes to the government for each man a year and about ₤8 per annum in wages, besides providing him with food, house, clothes, medical attendance, and medicines. The employer has also to pay for the transport of the laborer to the plantation; and after completion of contract for his return passage home, the natives are not permitted to leave their native villages for any length of time except by permission from the village chief or magistrate.

The term “Polynesian,” as used in Fiji, applies to the inhabitants of nearly all the South Sea Islands, Solomon Islands, and the New Hebrides, supply probably the largest number of that class of laborers which are known as Polynesians to Fiji. [8] They do not as a rule give satisfaction as plantation laborers, but some of them make good household servants in private families. The contract for Polynesian laborers is generally binding for five years, during which time the planter pays £3 per annum for an adult male. Women and children are paid less in proportion to their working abilities; but all monies earned by them are deposited in the government offices and are never paid to the men themselves. They all get free house, free clothes, medical attendance, etc., and after completion of contract are sent back to their native island at the expense of the original employer, who also pays all expenses connected with the importation. When using the term “clothes,” it must be understood to mean a few cheap articles only, the value of which does not exceed nine shillings ($2.25) per head per annum. At the expiration of contract, the government hands each man his wages in cash or gives him an order on some tradesman, to supply the bearer with goods up to the value of the amount due him. These so-called Polynesians are, on an average, considerably smaller men in stature than the Fijians and are not so strong, either; but they are a good-tempered, merry lot of people who never give much trouble.

The third class of colored laborers, who by far are the most numerous in Fiji, are the Indians, or coolies, imported from Hindustan or the East Indies. From an interesting article written by H. H. Thiele, Esq., I cull the following in regard to coolie labor: “The coolies, or Indians, were first introduced to Fiji from Calcutta in 1879, when some 480 arrived. It is, however, only since 1883 that the immigration has been regular or of importance. There are now about 10,000 coolies in Fiji, of who about 6,000 are working for the Colonial Sugar Refining Company. The cost of introduction has, on an average, been about £20 ($100) for each individual over ten years of age, the percentage of women in proportion to men being about thirty-five. There are proportionately a large number of immoral characters among the women, who as a rule take very little care of their children and consequently lose them. The indenture is for five years from time of arrival, at the expiration of which time the coolie becomes “free,” and after a further period of five years’ residence, he and his children are entitled to a free return passage to India by the first subsequent opportunity. Under special circumstances coolies can buy their freedom before the expiration of the five years stipulated. The Indian immigration ordinance states that a coolie can be employed on either time work or task work. In the former case he is required to work nine hours on each of the first five days in the week, and five hours on Saturdays. A task means the quantity of work an able-bodied man can perform by working continuously and diligently for six hours; five tasks and a half constitute a week’s work. No man is compelled to do more than one task per diem. For field work men are paid about one shilling per term a task and women nine pence. The district medical officer has the power to reduce the labor to be exacted from any coolie, if the condition of the man’s health requires it. Many good workers can earn nine or ten shillings per week on the same task on which others can hardly earn their food. All coolies working on an estate are supplied with free house, firewood, medical attendance, medicine, and hospital treatment. Taking them as a whole, the coolies are a sharp, low, and immoral lot; but there is no doubt about their being the cheapest laborers in Fiji, although they actually earn three or four times as much as they could do in their own country. Some of the laborers manage to save and place at deposit a considerable portion of their wages; others save and then lend the money to rogues of their own color, who cheat them; others, again, gamble and lose all their earnings to professional card sharpers, of whom there are many among them. Some of them are so innately lazy that they will seriously injure themselves bodily in order to plead the excuse of being unfit for work. The coolies will tell falsehoods to an unlimited extent, and it is therefore in many cases difficult to get convictions against them in the police courts. The usual punishment is a fine and, in default of payment, a period of imprisonment with labor. The time of absence from plantation work, on this account, is added to the time of indenture and called “estention [sic] of time.” Nearly all the laborers employed on the Nausori Plantation are coolies, there being only a few Fijians or Polynesians.

By far the most important industry on the Fijian Islands is the growing of sugarcane and the manufacture of raw sugar, though this industry was not commenced here till about fourteen years ago. The cane raised in Fiji is grown from imported cane tops, principally of a variety originally obtained from the Hawaiian Islands. Lands just cleared and broken up for cultivation gave at first a very abundant harvest, but experience has already shown that it does not continue to do so in Fiji, but that fertilizing is necessary; hence a crop of beans is started about every three years, which is plowed under green for fertilizing purposes; at least this is the plan adopted on the Nausori Plantation.

After visiting the Indian quarters, Mr. Wilson accompanied me to the native village called Nausori; it consists of something like twenty-five native houses, most of which are well built and roomy. The one we entered was also scrupulously clean in the inside and was not without a certain degree of comfort. The little Western church, provided with a pulpit but no seats of any description, was an object of considerable interest to me. During services the natives squat down on the mats. Most of the people (of both sexes) in the village were simply clad in their ordinary sulus.

By invitation, Mr. Thiele and myself dined with Superintendent Tenner, whose fine residence is perched on the top of a hill overlooking the river for several miles up and down. Mr. Tenner has a nice little family, and we spent a pleasant evening conversing about Utah and its people. Mr. Tenner has visited our territory, being employed as an engineer on the Denver and Rio Grande Railway at the time that road was being built through Utah.

“Jenson’s Travels,” August 12, 1895 [9]

Nausori, Island of Viti Levu, Fiji

Sunday, August 11. After breakfast Mr. William Wilson, the chief engineer of the Nausori Sugar Mill, placed me on a cane truck and called on two Indians to act as propeller; and off we started for Na Korociriciri, two and three-fourth miles distant. The poor fellows ran their best, at least a part of the way, endeavoring to give me a good ride, which was pleasant throughout for me. The roadbed built to conduct the sugarcane from the vast plantation fields to the mill, passing through the central part of the fields. Na Korociriciri consists of a cluster of houses (located on a hill) which serves as quarters for one of the plantation overseers and a large number of coolies and Indians. At this place I met, according to appointment made the previous evening, Mr. Eardley J. Mare, one of the plantation overseers, and Charles J. Morey, a man who has spent twenty-five years in Fiji and understands the native language almost to perfection. With these two gentlemen I started out on a four-mile walk through a hilly country covered with a dense tropical forest, in the direction of Bau, the old native capital of Fiji. On the road we passed a point where a pitched battle was fought many years ago between two tribes, or nations, of Fijians, in which the side commanded by the king of Bau were victorious and killed about eight of their enemies, whose bodies they took with them to the island of Bau, where they cooked and devoured them in regular cannibal style.

At the end of our walk, we found ourselves in the native village of Namata, which is pleasantly situated on the bank of a river, or very wide creek, called Wai Namata. Here we were well received and treated to luncheon in the house of Ratu Marika, who was once a great chief and also a judge under the colonial government. He is a stout, well-built man, with a dignified bearing and a very intelligent look for a Fijian; he also occupies the largest house in the village and has an interesting family. He could not tell us how old he was but said that he had a beard when the missionaries first arrived in the islands (in 1835). He and his people seemed to feel quite proud of their little new church, which had recently been built upon the hilltop immediately behind the village, upon which I showed him a picture of the Salt Lake City Temple and a sample of the rock of which it is built and had Mr. Morey explain the nature and size of the building to him. He seemed astonished, as if he had never known before that buildings of such dimensions existed in the world. He also, for the first time in his life, heard the name of Utah and the Mormons mentioned and wanted to know if I and my people were Christians. Our interpreter explained to him that I also cater Christianity in its primeval purity and preached the gospel exactly the same as it had been preached by Christ and his Apostles in ancient days. This seemed [to?] please him very much; and I only wished that I had possessed a knowledge [of?] his language so that I might have given him further explanations. At the chief’s house we also met Ratu Tuisevura, the district doctor, who is a grandson of old King Cakobau. He decided to accompany us to Bau, where his father, the head chief of Fiji, still resides.

We next hired a boat with four stout young fellows to row it, and down the river, down the river it went merrily, for the rowers seemed to be in the best of humor and broke out into hearty peals of laughter whenever they noticed anything in the movements of their passengers or surroundings which pleased them. At length, after rounding several points and bends in the river, we reached the ocean, when our jolly oarsmen pulled straight for the island of Bau, which we reached about 2:00 p.m., about three miles from where we got into the boat. We were met at the landing by quite a number of natives, whose curiosity had been somewhat aroused at seeing three white men nearing their island town.

Soon after landing we met Mr. A. J. Small, the Wesleyan Methodist minister residing here, and his wife. They were going off to fill an appointment on a neighboring island. I had a hurried and quite interesting conversation with Mr. Small, who told me that the Wesleyan Methodists had 99,000 adherents on the group, to whom nine white missionaries and a large number of natives were “discoursing the word of God” every Sabbath. Ten white missionaries were the number allotted to the group, but one of their number had died quite recently. So thorough has been the labors of the Wesleyans on Fiji that there is not a village on the whole group which is not included in their field of operation. The headquarters of the Wesleyan mission are at the native town of Navoloa, situated at the mouth of one of the outlets of the Rewa River, about eight miles from Bau. Mr. Small expressed his dislike for the Catholics, who were a continued menace to the labors of the Wesleyans, as they were following in their track nearly everywhere, sowing the seed of discord and dispute, as he said, among the natives.

Bau is a little island with an area of about twenty-five acres lying less than half a mile off the east coast of Viti Levu. It consists of a small round-topped hill with a rim of flat land three-parts around it—a very narrow rim at the side but running out like the peak of a cap into a good building level on the northeast. The mission premises occupy the hilltop; the native houses of the town with their tiny gardens, (Photo of native house) trees, and small water holes are all on the flat. The Wesleyan Methodist church, a rock building with an iron roof, is also situated on the flat, but right at the foot of the hill. The flat portion of the island is artificial; the natives (perhaps centuries ago) having brought the soil from the mainland. The hill rises to a height of about fifty feet above the sea level. There is nothing on the hill except the missionary buildings and the grave of King Cakobau (pronounced “Thakombau”). The village on the flat consists of nearly fifty native houses built very irregularly with narrow alleyways between them, and surrounding the raised square on which formerly stood the heathen temple, before the portals of which so many poor Fijians in bygone years ended an inglorious existence by having their brains dashed out upon a large stone which still occupies a prominent position at the foot of the great pedestal. After being killed they were eaten by their countrymen. Bau sustains the proud distinction of being the scene of more cannibalism than any other spot on the Fijian Islands. Tradition says that on one occasion, when the king of Bau returned from a victorious warfare against the tribes in the mountain regions of Viti Levu, the dead bodies of their enemies were piled up in a long row about six feet high, and the whole nation who obeyed the king of Bau were invited to a grand cannibal feast on the island.

We spent about three hours on the island of Bau, during which we visited all the points of interest, among which the old heathen temple site was one of the most important. The pedestal on which the temple once stood is well preserved and stands about ten feet above the level of the ground surrounding it. The historic stone on which so many heads were crushed in times past is still there; and Mr. John Acraman, a native of England and the only merchant of Bau, who was with us, related some extravagant stories about old Fijian cannibal times, associated with Bau and the heathen temple. These, however, I do not feel disposed to give to the readers of the News at present; but will merely say that the last cannibal tragedy enacted on Bau according to the best memory, was associated with a visit of some very high native dignitaries to the court of Bau. The king, who desired to show extra honors to his distinguished guests, sent his men out to secure “long pig” for the occasion; and these men, seeing a number of women fishing on the island a short distance, went and captured eight of them, forced them up to the temple front, killed them on the rock above mentioned, and then delivered their bodies to the cooks, who prepared them for the great cannibal feast which follows. (Photo of cannibals)

We also called on the old chief, Ratu Epeli Nailatikau, who is the eldest living son of King Cakobau. He is a very stout and muscular-built man, unusually dark skinned for a Fijian, wears a heavy mustache and side whiskers, and looked at first cross enough to eat a man, even at this late day. I induced him to give me his autograph, but he seemed too tired to get the ink, so he wrote it with a lead pencil on one of my business cards. He became quite interested when I showed him my Salt Lake views and wanted to know if the navigation was very extensive on that great American inland sea. By way of reciprocating he showed us a horrid picture of a cannibal feast, which took place at Bau in 1849. It was painted from nature by some English sailors who were visiting the island at the time.

We also visited King Cakobau’s daughter-in-law, a Tongan woman of rank and the relict of the late Ratu Timoci (Timothy) and mother of the so-called princesses, to whom I was introduced in the native village near Suva. By request she gave me her autograph as Ane Tubou and said she was thirty-eight years old, though she might pass for twenty-five. She felt highly pleased when we referred to her youthful appearance and that she was as good-looking as her daughter, the Princess Litia Cakobau, who was about to get married. The old king had three sons and three daughters, of whom only this one daughter and one son of the old chief whom we visited are now alive.

Having now become thoroughly introduced to the royal family of Fiji, it was but natural that I should desire to see the grave of the old king himself. Consequently we ascended the hill and soon found ourselves within the royal cemetery, which encloses a space about 35x40 feet surrounded by a low ornamental wall. Within the enclosure grows two young sandalwood trees and a number of bushes peculiar to the tropics, while a beautiful carpet of grass covers the remainder of the ground. In the center of the enclosure stands a massive pedestal of rockwork, 12x9 feet, on which the monument proper is raised. It consists of a square cement obelisk of respectable dimensions inlaid with marble, on one side of which I read the following: “Ai vakananumi kei Ratu Seru Cakobau, sa bale e nai ka dua ni siga ni vulu ko Feperneri e na yahaki ni noda turaga e 1883.” (“This is in memory of Chief Seru Cakobau who passed away on the 1st day of February in the year of our Lord 1883.”) Cakobau’s original name was Ratu Seru; but when he returned from one of his eventful war trips, the women cried out “Cakobau,” free translation, “Evil has overtaken Bau.” “The appellations suits me,” said the chief, “from henceforth my name shall be Cakobau,” and with that suggestive name he was subsequently crowned king of Fiji.

Cakobau was made king of Fiji in 1871. Before that he had only been a king in Fiji. But he had reigned but three years when his offer of the Fijian kingdom to the British was accepted by Queen Victoria and her cabinet. The king, with his chief, stood by the flagstaff at Nasova, a native village, on October 10, 1874, and saw his national flag hauled down and the royal standard of England ascend majestically in its place, amid the salvos of artillery and ringing British cheers. Though he was recognized by the English as king of the entire Fijian groups, he had never subdued the other chiefs of the islands to the same extent as the Great Kamehameha had the Hawaiian Islands. Cakobau was continually troubled with revolts and uprisings on the part of the mountain chiefs; this, together with certain claims on the part of the United States, so annoyed him that he decided to lay down his scepter and let the ship of state be manned by a nation who had power and means to do so. After his abdication, the ex-king lived a somewhat private life at his homestead at Bau; but his advice and counsel was often sought by the colonial government. Finally, a carbuncle formed in his back, and this became the direct cause of his death, which occurred at Bau, February 1, 1883. Though at first bitterly opposed to the missionaries, King Cakobau finally became a warm supporter of Christianity and died as a member of the Wesleyan persuasion.

From the top of the hill where the remains of King Cakobau rests, a fine view is obtained of the surroundings. Close by is the coast of Viti Levu, where the Bauans get their food; and a large area of level country quite thickly populated, stretches away to the south, ending at Rewa. To the northeast stands the island of Ovalau twenty miles away, where Levuka, the old colonial capital is situated, and other smaller islands, among which are Vuva and Moturiki. In the far background the blue outlines of other islands are seen against the sky. A mass of reefs and long guardian flats, covered at high water, protected Bau from all except skilled navigators in those puzzling waters, in the “great old days” when Cakobau and his ancestors reigned with the hand of tyranny, blood, and cannibalism on Fiji.

The present population on Bau is about 300. They rank as the Fijian aristocracy. Like the old Romans, it is considered as great an honor to be a common citizen of Bau as to be a chief of any other part of the country. The native houses of the island are large and strong, and though the outside appearance is somewhat uninviting, the interior is made very rich, clean, and comfortable, mats with soft underlying material covering the floor. While that portion thereof which is used for beds is generally raised a few inches to a foot above the rest of the floor. It is not at all an uncommon thing to see six doors leading into the same room from the outside, which means good ventilation. The only white residents on the island are the Wesleyan minister, Mr. Small, and Mr. Acraman, with their respective families. Mr. Acraman is a native of England and has resided in Fiji upwards of twenty years; his wife is a half-caste. The minister is a native of London, England, and has spent sixteen years of his life in Fiji.

As the sun was sinking quite low in the west, we reembarked in our little craft and returned to the main island but landed some distance farther up the Wai Namata Creek than where we chartered the boat earlier in the day. Walking through the forest at a rapid rate, we soon reached the quarters of Mr. Mare, where we took supper, after which an Indian pushed a truck having me onboard back to Nausori; and I arrived at my lodging at 10:00 p.m., well pleased with my hurried visit to one of the most historic places in the South Seas.

“Jenson’s Travels,” August 22, 1895 [10]

Mu‘a, Tongatapu, Tonga

Monday, August 12. I accompanied Mr. Henry T. Moltke, the manager of the Nausori Plantation, on a horseback ride through the sugar cane fields, by which means I obtained a better knowledge of cane raising than I ever had before. Hundreds of people were at work doing the various kinds of labor associated with the cane culture. Several small incidents occurred. One man was slapped by the manager for not doing his work properly. A woman laborer, who claimed to be sick and unable to work, was ordered sent to the hospital; and another one, who claimed to have been insulted by the foreman and came running after the manager crying and telling a strange tale of woe, was ordered back to work as her story was not believed. Mr. Moltke told me that incidents of that kind happened more frequently on Mondays than any other day of the week, as many of the people, after having rested on the Sunday, were loath to return to their work again. Well, taking everything into consideration I cannot say that I admire contract labor. The question naturally arises, what are these people but slaves during the five years of their indenture? Their bodies are certainly not their own during that length of time. They are also subjected to harsh treatment, the only excuse given for which is that they could not be controlled without it, that they are incapable of appreciating kindness, and would become absolutely useless as laborers on plantation if they were treated with that consideration which is generally extended to white people. Their intelligence, I was informed, could not be appealed to successfully, as all they feared was corporal punishment, which, by the way, is not allowed by law. I took dinner with Mr. Moltke, whose wife is a New Zealand colonist, born of English parents.

Tuesday, August 13. I spent the day writing and conversing with my friends at the Nausori Mills about Utah and the “Mormons.” Both Mr. Thiele and Mr. Wilson, whose guest I was during my sojourn on the Rewa River, are both intelligent men. Mr. Thiele’s family is in Sydney, and Mr. Wilson is unmarried.

Wednesday, August 14. I felt weak from a violent bilious attack from which I had suffered during the night, in consequence of which I gave up a walk of twelve miles which I had contemplated across the country from the mills to Suva; and I hired a boat instead to take me by water. We tied the boat to a steam launch, which sailed ten miles down to the Laucala Bay, from where my hired Indian rowed me two miles across the bay to the peninsula upon which Suva is situated, leaving me to walk about three miles to the town. On my arrival at Suva I was disappointed at finding that a circus had just arrived, which had broken into an arrangement made for me to lecture that evening at the Mechanics Hall.

Thursday, August 15. The steamer Ovalau, one of the Union Steam Ship Company’s boats, arrived at Suva from Samoa en route for New Zealand via Tonga. As a number of our elders are laboring on the Tongan group at the present time, I decided to take a passage for New Zealand via Tonga and Samoa, instead of going to Samoa first, which would have been a more direct route. I spent most of the day perusing literature on Fiji and writing. I also paid another visit to the Fijian quarters occupied by native officers and employees of the government, where I had been once before and renewed my acquaintance with some of the leading chiefs and prominent men to whom I briefly explained the principles of the gospel as we believed them. I especially interested myself in Kadavu Levu, the grandson of King Cakobau, previously mentioned, who promised me that if any of our elders should be sent to Fiji, he would be kind to them and endeavor to pave the way for them to the native population. The white inhabitants in Suva as a rule are not religiously inclined like the whites in Honolulu; their sole object in life seems to be wealth of this world; nor can I give them credit for much hospitality.

In perusing a “Handbook on Fiji,” published by the government, I find that the Fijian Archipelago was discovered on March 5, 1643, by Abel Jansen Tasman, who, however, does not appear to have found anchorage. More than a century later, Captain Cook sighted the southeastern part of the group. He was followed by Captain Bligh, who passed through the group in the Bounty’s launch (1789), and Captain Wilson, of the Duff, in 1797.

It is possible that some of the navigators of the seventeenth century, who sailed from South America and were never heard of again, may have visited the group, and during the eighteenth century there must have been occasional intercourse between the natives and the Spanish; but the islands remained practically unknown until 1804, when a party of escaped convicts from New South Wales settled down among the natives. These were followed by traders. In 1835, a small settlement of whites was established at Levuka on the island of Ovalau; and others settled down among the natives in various parts of the group. In 1855, the American government having passed a claim for £9,000 against the chief Cakobau (Thakombau), which he was quite unable to meet and the justice of which he never admitted, the leading chiefs, offered to cede the islands to England, on condition that the claim should be satisfied. The commissioners reported unfavorably, and the offer was refused (1861). In 1871 a constitutional government was established by the Europeans for the “Kingdom of Fiji” under Cakobau as king, but it broke down in 1873, owing to the opposition of the settlers in outlying districts; and in 1874 the chiefs formally offered to cede the islands to Great Britain, and sovereignty was proclaimed by Sir Hercules Robinson, G.C.M.G., governor of New South Wales, on September 23, 1874. A year later the administration was assumed by Sir Arthur Gordon, the first governor.

Under letters patent, dated December 17, 1880, the island of Rotuma, lying between 12˚ and 15˚ S latitude, was, on the petition of the chiefs, annexed to the colony of Fiji. [11]

Friday, August 16. The Ovalau did not sail today but will leave tomorrow. Mr. A. M. T. Duncan, agent of the Union Steam Ship Company, kindly presented me with a free first-class passage from Suva, via Tonga and Samoa, to Auckland, New Zealand.

Saturday, August 17. I boarded the steamer Ovalau, and sailed from Suva, Fiji, at 11:45 a.m. The ship taking a southeasterly course, we were soon out of sight of land. The wind blowed [sic] hard and directly against us, and the sea rolled high, hence the unpleasant sensation which to me meant the next thing to seasickness. There were a large number of passengers onboard, most of whom were excursionists from New Zealand on a pleasure trip to the tropics. During the night we passed the island of Matuku on our right and Totoya on our left, both belonging to the Fijian group.

Sunday, August 18. I arose from a somewhat disturbed night’s rest at 7:30 a.m., just as we were passing the island of Kabara on our left or larboard side. At 11:00 a.m. we were sailing opposite the island of Fulaga; and a little later we passed the islands of Ogea Levu and Ogea Driki, all on our left, which were the last of the Fiji Islands we saw on this voyage. At noon the ship’s log, read as follows: latitude 19˚00˝ S, longitude 178˚28´00˝ E. Distance from Suva 200 and to Vava‘u 260 nautical miles. The wind blowed [sic] heavily against us all day, and most of the passengers failed to show up on deck.

Monday, August 19. During the day I made the acquaintance of the captain and several of the ship’s officers, as well as a number of the passengers, with whom I conversed freely about the “Saints and their doctrines.” At 11:00 a.m. we could see land ahead which proved to be the well-known volcano island Late, which on account of its height (1,790 feet) is a noted landmark for navigators. The island is about ten miles in circumference, and the mountainsides are clad in a beautiful green, the tropical forest covering the slopes from the steep and rocky coast to the summit of the crater. The island is situated in latitude 18˚35´ S; and longitude 175˚16´ E. Early in 1854 a new volcano suddenly broke out with great violence on this island. On the night of the eruption the loud roaring was heard by the people at Lifuka, sixty miles distant. From the shores of Vava‘u, thirty miles away, an immense pillar of smoke was seen during the day; and at night the fire of the volcano was distinctly visible. The fall of dust and ashes was so immense that the light of the sun was thoroughly obscured for several days. The fine dust penetrated even into the closed houses which were from thirty to forty miles away to such an extent as to spoil the meals that the people were eating. Although frequented often by natives, who go there to gather coconuts, there were no people on the island at the time of the eruption; hence no lives were lost.

We passed Late at 10:00 p.m., and even afterwards the outlines of the islands known as the Vava‘u group could be seen toward the eastern horizon. At 5:00 p.m. we entered the channel leading to the harbor of Neiafu, passing between two precipitous rocky islets that seem to stand as sentinels over the sea gates. We skirted the Vava‘u coast, having the towering cliffs of Mounga Lafa on our left, and the island of Hunga on our right. Upon doubling the headland of the former, the natural formation and exquisite beauty of the harbor began to unfold to our view. I have seldom, if ever, seen a more beautiful coast than this one. Behind lay the small islands of Hunga and Niuababa, or Nuapapu, shutting out from sight the distant and lofty peak of Late, while at the same time effectually protecting the harbor from the heavy swell of the sea from the west and southwest. On the right lay the bay of Nuapapu, formed by the eastern shore of that island and the western side of Falevai, or Kapa. Several small islands lie in the bay, and its southern extremity is bounded by a shoal reef, extending across the strait between the two islands just named. The northern extremities of Niuababa and Falevai consist of high and perpendicular cliffs, crowned by thick woods and groves of cocoa palms. The sloping highlands of Hihifo, on the main island (Vava‘u) on the left are also covered with dense and rich vegetation to within a few feet of the sea. Leaving Nuapapu and Falevai behind, the channel becomes narrower and seems to be terminated by the high hill of Talau (perhaps 600 feet high). But after passing the beautiful sandy shores of the island of Utugaki, the bay of Talau opens out to view on the left. Passing on, the steamer sails through a narrow but deep channel lying between the hill Talau on the left and the sandy point of Utulei on the right, into the beautiful harbor, and at 5:30 p.m. we were lying at the wharf at Neiafu, the principal town of the Vava‘u group. Soon afterwards the wharf and deck of the steamer swarmed with natives of both sexes, who chattered and laughed as if they had never known anything but pleasure. I was the first of the passengers to land and soon found myself in the center of the town and in the midst of beautiful coconut and orange groves. I ate a liberal supply of the latter; I also peeped into a native church, where a number of the people were assembled for evening prayer, and called at the post office to be informed that there were none of our missionaries at Vava‘u but that I would find some on the other two main groups of the Tongan Archipelago, namely, Tongatapu and Ha‘apai. Neiafu contains about 200 inhabitants, of whom thirty are whites, mostly German traders.

Tuesday, August 20. The ship having laid by the wharf all night, I arose early in the morning and took a long walk all alone to the hill Talau, from the top of which (two miles distant from the town of Neiafu) (Photo of Neiafu harbor) I obtained a magnificent view of the harbor, bays, straits, and the different islands of the Vava‘u group. Finding myself in so solitary and lonely a place, I also sought the Lord in secret and earnest prayer, and returned to the ship happy and glad, but somewhat tired and hungry, as I had started off without breakfast. After eating oranges to my heart’s content and chatting with some of the natives who could talk a little English, I once more boarded the Ovalau, which (after taking onboard a cargo of oranges, copra, etc., and a large number of native passengers bound for Tongatapu) steamed off from Neiafu at 12:00 noon. We had stopped at the Neiafu wharf about eighteen hours. We left the Vava‘u group the same way that we had come in; but having reached the open ocean we stood off to the south and had a fine voyage, the sea being smooth and the wind easy. In the evening we passed on our right the two mountainous islands of Kao and Tofua, of the Ha‘apai group. Kao is 5,000 feet and Tofua 2,800 feet high. The latter is the island on which John Norton, one of Captain Bligh’s men, was killed by natives in 1789. The readers of the News will no doubt remember the sad circumstance connected with the meeting onboard the British ship, Bounty, Captain Bligh; how the captain and some of his men were forced into a small boat by the mutineers, and after a most extraordinary and perilous voyage reached the Dutch settlements in New Guinea, after losing one of their numbers (Mr. Norton) on the Friendly Islands; and how the mutineers headed by Fletcher Christian afterwards settled on Pitcairn’s Island where a number of their descendents still reside.

Neiafu harbor. Courtesy of Church History Library