They Ministered Unto Him of Their Substance: Women and the Savior

Camille Fronk Olson

Camille Fronk Olson, “They Ministered unto Him of Their Substance: Women and the Savior,” in To Save the Lost, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 61–80.

Camille Fronk Olson was an associate professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University when this was published.

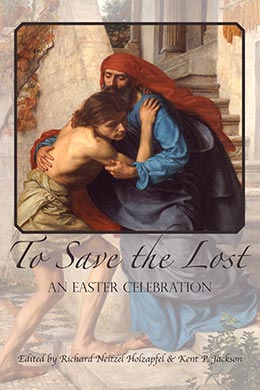

Minerva K. Teichert, Jesus at the Home of Mary & Martha, Brigham Young University Museum of Art.

Minerva K. Teichert, Jesus at the Home of Mary & Martha, Brigham Young University Museum of Art.

Various images symbolize and typify Jesus Christ in scripture. He is Alpha and Omega (see Revelation 1:8; D&C 19:1; 35:1) and the author and finisher of our faith (see Hebrews 12:2). He personifies the love of God in the tree of life (see 1 Nephi 11:7; 15:36) and the Bread of Life in the manna in the wilderness (see John 6:31–35). Often, the typology of Christ conveys male imagery; for example, the Savior is the male lamb without blemish that is sacrificed for sin (see Exodus 12:5), the mighty man of war who conquers every enemy (see Isaiah 42:13), and the Good Shepherd, who gives his life for his sheep (see Isaiah 40:11; Hebrews 13:20; Helaman 7:18).

Other scriptural metaphors of Christ express female imagery. He is as the pained woman in childbirth, crying in anguish as she brings forth life (see Isaiah 42:14); the mother who caresses and comforts her troubled child (see Isaiah 66:13; Psalm 131:2); and the mother hen who gathers her chicks under her wings (see 3 Nephi 10:4–6; D&C 10:65; Luke 13:34). The Savior’s merciful mission of salvation is further linked to the pains and unselfishness of motherhood by the same Hebrew root (rhm) that produces the word for Christ’s compassion and a mother’s womb.

In spite of such ways that the Messiah was likened to women, Jewish society at the time of Christ did not acknowledge the value of women or consider ways that women could contribute to their religious worship. On the contrary, men in first-century Palestine frequently marginalized women and distrusted their witness. For example, on that first Easter morning, the disciples questioned the women’s report of the empty tomb, concluding that their words were merely “idle tales” (Luke 24:11). Even today these New Testament women and their testimonies are easily overlooked which obscures their potential to apply to us. This chapter will consider the Savior’s sacrifice and victory over death from the perspective of these women with the hope that they may lead us to a renewed appreciation for his enabling power and promises.

A couple of general observations will be helpful in establishing the larger context for this paper.

First, a comparison of the testimonies of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John reflects some conflicting details surrounding the witnesses of Christ’s Resurrection. Attempts to perfectly harmonize the various accounts have proved disappointing except to conclude that an unspecified number of men and women in Palestine had a personal encounter with the resurrected Lord. Who saw him first and where and when must remain somewhat nebulous.

The Nephites’ witness of the resurrected Christ provides a parallel scenario in that the specific order in which they approached their Savior seems irrelevant. From the Book of Mormon we simply know that 2,500 men, women, and children came forward “one by one” to see with their eyes and feel with their hands the prints of the nails in their Redeemer’s resurrected body. Each of them could thereafter bear record that he was unquestionably Jesus Christ, whom the prophets had testified would be slain for the sins of the world (3 Nephi 11:10–15).

My second general observation: the purpose of scripture is to testify of the Savior’s victory over sin and the grave. Holy writ proclaims that none is like Jesus Christ; he alone is Redeemer and Savior. Therefore, the focus of the Gospel narratives is not to communicate that any of the disciples was more deserving, more loved, or more righteous than the other followers of Jesus. They were not written to indicate that God views an Apostle’s witness with greater merit than one professed by other disciples or that a man’s testimony is more valuable than a woman’s. Furthermore, the scriptures do not teach that women are innately more spiritual or receptive to revelation than men, or that either men or women have less need of Christ’s enabling power than the other. Rather, the scriptures jointly testify that each of us is lost and in desperate need of a Redeemer. In this way, every man, woman, and child who encountered the resurrected Lord in the meridian of time is a type of each of us. Through their individual and combined experiences, we are led to discover and proclaim our own personal witness of Jesus Christ.

The Women’s Identity

Who were the women near the cross and at the empty tomb? Collectively, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John name several women in the Passion narratives, noting that they all came from Galilee.

- Mary, the mother of Jesus (see John 19:25)

- Mary Magdalene, the only woman named in all four Gospels (see Matthew 27:56; 28:1; Mark 15:40; 16:1, 9; Luke 24:10; John 19:25; 20:1, 11–18)

- Mary, the mother of James and Joses (see Matthew 27:56; 28:1; Mark 15:40; 16:1; Luke 24:10)

- The mother of Zebedee’s children (perhaps the same as number 5) (see Matthew 27:56)

- Salome (perhaps the same person as “the mother of Zebedee’s children” because they appear in nearly identical lists of women in two of the Gospels) (see Mark 15:40; 16:1)

- Joanna, the wife of Chuza, Herod’s steward (see Luke 24:10)

- The sister of Jesus’s mother (see John 19:25)

- Mary, the wife of Cleophas (see John 19:25)

- “And many other women which came up with him [from Galilee] unto Jerusalem” (Mark 15:41; see also Luke 23:49, 55–56)

Of all the Gospel writers, only Luke introduces us to these “Galilean women” before the death and Resurrection of Christ. Because Luke records few of their names in his earlier narrative, we cannot definitively conclude that the women were those at the cross. We can, however, glean general insights into those women who attended the Savior at his death and burial from a study of these women who became disciples in Galilee.

In Luke 8:1–3, we learn that in addition to Mary Magdalene and Joanna, a woman named Susanna and “many others [women]” in Galilee, received the Savior’s healing from “evil spirits and infirmities.” With their lives transformed, these women formed an important core to the Savior’s unofficial entourage as he and the Twelve traveled “throughout every city and village” (v. 1). They were not, however, merely tagging along. Jesus and his itinerant company depended on the goodness of others to provide daily nourishment and a place to sleep. Apparently these good women assisted in the Lord’s sustenance because they “ministered unto him of their substance” (v. 3), meaning they gave to him from their own resources.

The implication here is that these women had access to ample means and the freedom to divest of it in the way they deemed pertinent. They also appear to have had the support and blessing of husbands or families to be relieved of traditional domestic duties in order to serve the Savior in this way. At least one of the women, Joanna, was married. Others may have been widowed or single. One wonders at the social ramifications for a group of women who traveled around the country with Jesus and his Apostles. Did they attend the entourage during the day and return to their own homes at night? Were any of them related to one of the male disciples? Did their children ever accompany them, or had they already reared their children? Whatever the circumstance, their commitment to the Savior was not episodic; these women still followed him in Jerusalem—to his Crucifixion, his burial, and his Resurrection.

In Luke 7–8, in verses surrounding Luke’s brief description of these generous women from Galilee, he recounts the stories of specific women whose lives were forever changed through encounters with the Savior. Notably, we read of the widow of Nain (see Luke 7:11–15), the woman who loved the Savior so much that she washed his feet with her tears (see Luke 7:36–50), the mother of Jesus (see Luke 8:19–21), the daughter of Jairus (Luke 8:41–42, 49–56); and the woman who was healed of a serious illness by touching the hem of the Savior’s clothing (see Luke 8:43–48).

Were these women among the Galilean ensemble that shared their resources along with Mary Magdalene, Joanna, and Susanna? Although no conclusive answer to these questions is possible, except in the case of the mother of Jesus, we can at least think of these women as representative of the faithful Galilean women who attended the Savior in the Passion narratives. More importantly, they can teach us about coming to Christ and laying hold on his Atonement.

Widow of Nain

Upon his arrival in Nain, Jesus encountered a funeral procession just exiting the village. Jesus immediately identified the mother of the dead man, knowing that she was a widow and that the dead was her only son. The small village of Nain is located about seven miles southeast of Nazareth, the village where the Savior grew to manhood. One wonders, was Jesus previously acquainted with the widow’s family?

We better appreciate the Lord’s instinctive compassion for the widow when we realize that at her husband’s death, his estate would have first gone to their son, then after the son’s death, to the closest male relative.[1] Without her son, the widow had no means of support and would be left a vulnerable target for exploitation in her society.

Into this poignant funeral scene walked Jesus. He approached the mourning mother and uttered a seemingly impossible command, “Weep not” (Luke 7:13). As the only one with power to give hope and joy in the face of loss, the Savior brings life even when we have not asked. With a touch of his hand and the power of his word, the young man arose, and Christ “delivered him to his mother” (vv. 14–15). Through his atoning sacrifice, the Savior heals broken hearts, restores families, and gives life, even eternal life.

The Woman Who Loved Much

While a Pharisee named Simon hosted Jesus for dinner, a Galilean woman entered his house carrying an alabaster vial filled with expensive ointment. The scriptures introduce her simply as “a woman in the city, which was a sinner” (Luke 7:37). The Greek verb here is in the imperfect tense, suggesting that she was known from the town and had been a sinner but was a sinner no longer.[2]

We do not know her specific sins, only that they were “many” (v. 47). The most common assumption is that she was a prostitute—because she was a woman of means, indicated by her possession of an expensive vial of ointment, and had committed publicly known sins. Just as plausible, however, was that she openly interacted with Gentiles or others considered “unclean.” Simon knew her sin because he belonged to the town but expected Jesus to know it by inspiration, if he really were the Prophet,[3] leading us to conclude that one could not deduce her sinful life by her outward appearance.

By teasing out the scriptural text, we may conclude that the woman must have already repented of her sins after a previous encounter with the message of salvation. When she knew that Jesus was at Simon’s house, she made preparations to demonstrate her gratitude to him by anointing his feet with the ointment.

Actually being in the presence of Jesus after her repentance may have been even more emotional for the woman than she anticipated. She began to weep when she saw him, and her tears flowed with the ointment. Wiping his feet with her hair rather than a cloth may suggest that her tears were spontaneous and she had no other means to wipe them.[4] Repentant and profoundly humble, she fell at her Savior’s feet and kissed them with overwhelming reverence.

By contrast, Simon’s self-righteousness bore unspoken witness that he felt that he needed no Redeemer. While the woman wept in humble adoration, Simon silently rebuffed Jesus for allowing a sinner to touch him thus, concluding this was evidence that Jesus was no prophet. Knowing Simon’s thoughts, Jesus told him the parable of two debtors, who were both subsequently forgiven by their creditor: “There was a certain creditor which had two debtors: the one owed five hundred pence, and the other fifty. And when they had nothing to pay, he frankly forgave them both. Tell me therefore, which of them will love him most?” (Luke 7:41–42)

In a question pointed to Simon but also meant to be heard by the woman, Jesus asked, “Tell me therefore, which of them will love [the creditor] most?” Simon logically and accurately answered, “I suppose he, to whom he forgave most” (Luke 7:42–43).

Who does love the Savior most? In reality, is it not all those who recognize they have sinned, fallen short, and are forever lost without the atoning blood of Jesus Christ? Bankrupt in spirit and burdened by sin, we come to Christ as unprofitable servants. In such a helpless plight, none of us claims that our sin is merely a fifty-pence problem. Our debt is greater than we can ever repay, time immemorial.

Christ acknowledged the woman’s soul-felt repentance by telling Simon, “Her sins, which are many, are forgiven; for she loved much: but to whom little is forgiven, the same loveth little.” Then turning directly to the woman, Jesus proclaimed, “Thy sins are forgiven. . . . Thy faith hath saved thee; go in peace” (7:47–50). The Savior’s forgiveness of the woman was not a consequence of her love for him at that moment, or of her tears and expensive ointment. Her love for the Savior was a product of his cleansing gift to her. The Apostle John taught, “We love him, because he first loved us” (1 John 4:19). Through her sincere acceptance of the Lord’s Atonement, the Galilean woman who loved much teaches us to reverence our Redeemer because of his gift of forgiveness. How can we not, therefore, fall at his feet and manifest our profound love and gratitude to him?

The Mother of Jesus

Luke next identifies the mother of Jesus among the Galilean women. Presumably still a resident of Nazareth, Jesus’ mother appears not to have preferential treatment when her Son came to town. How rarely did she get to talk with him alone or care for him as his mother? Because of the “press” of the crowd, she was often denied such a blessing (Luke 8:19). With his mother near the back of the crowd, Jesus explains that his family expanded beyond his natural family to include all those who “hear the word of God, and do it” (v. 21). A relationship with Christ is not based on lineal descent but rather a willing acceptance of his teachings.

Mary exemplified what the Lord meant by hearing the word of God and doing it from the time the angel appeared to her to announce that she would bear the Son of God. She responded with faith, “Be it unto me according to thy word” (Luke 1:38), not knowing what hardships her discipleship would require of her. Her conviction to do whatever God required echoes the greater words of passion and assurance that her Son cried in the Garden of Gethsemane, “Father, if thou be willing, remove this cup from me: nevertheless not my will, but thine, be done” (Luke 22:42).

When Mary and Joseph took the infant Jesus to the temple to offer a sacrifice according to the law (see Leviticus 12:6–8; Numbers 18:15), the Holy Spirit taught an elderly man named Simeon that this baby was the long-awaited Messiah. When Simeon spoke, however, he did not say that he saw the Messiah but that his eyes were looking upon God’s salvation. By revelation, he knew that embodied in this tiny babe were all our hopes and promises for eternity.

Speaking prophetically, Simeon then soberly declared, “This child is set for the fall and rising again of many in Israel; and for a sign which shall be spoken against” (Luke 2:34). Turning to Mary he continued, “a sword shall pierce through thy own soul also that the thoughts of many hearts may be revealed” (v. 35). In other words, because of this child’s future mission, many in Israel would be faced with a decision that would lead them either to destruction or to the highest heights. That option for Israel, however, would come at a tremendous cost to Jesus through their rejection of his teachings and Atonement and through his humiliating death on the cross.

Furthermore, this clash of reactions to the Savior would not leave his mother unscathed. Mary’s soul would also be wounded during her Son’s ministry through divisions within her own family. [5] Discipleship with Jesus Christ transcends family ties. When we are born again, when we “hear the word of God, and do it” (Luke 8:21), Jesus Christ becomes our Father and we become his daughters and his sons. As Mary waited to see Jesus from the back of the Galilean crowd, was her heart pierced when she realized that her Son was not hers alone, but only hers to give to the world?

As a model of discipleship, Mary demonstrates another principle for us. The fact that she was his mother did not reduce her need to “hear the word of God, and do it” any less than us. Mary reminds us that blood lineage is no substitute for the enabling blood of the Atonement. Every one of us, whatever our particular circumstance or family background, is lost without Christ’s gift of salvation.

The Daughter of Jairus and the Woman Who Touched the Hem of His Garment

The stories of Jesus raising the daughter of Jairus from the dead and healing the woman with the issue of blood are intertwined in the Luke 8 account. They are therefore most meaningful when viewed together.

Jairus’ only daughter, probably his only descendant,[6] was dying at the age of twelve, just as she was coming of age as an adult in her society. Jairus, a ruler of the local synagogue, was forthright and confident yet humbly knelt at Jesus’ feet to petition his help. The Lord had more to teach Jairus, however, before going to his home. The girl had died when they finally arrived, perhaps because Jairus needed greater faith in the Savior’s power than he possessed at his first petition to Christ. On the way to his home, Jairus saw such faith exemplified in the form of a woman who had been ill for as long as his daughter had lived.

The woman, simply known by her disease, was not dead but was just as good as dead, considering her hopeless circumstance that isolated her from society. The scriptures do not specify the cause of her bleeding, but it is generally considered to have been gynecological in nature. According to the law of Moses, such an illness rendered the woman ritually unclean and anything or anyone that she touched was subsequently unclean (see Leviticus 15:25–31). Her bed, eating utensils, and food she prepared were tainted. Most likely, her family members no longer touched her, and her friends abandoned her long ago.

Luke reports that the woman “spent all her living upon physicians” without a positive resolution (Luke 8:43). This description suggests that she was a wealthy woman at one time—but no more. The woman therefore represents depletion in nearly every way—physically, socially, financially, and emotionally—but not spiritually.[7] In the midst of all her distress, buried in the impossibility of her circumstance, she had one shining hope. With a boldness and determination that must have stretched her weakened body to its limits, the woman crafted a means to access her Savior without anyone’s notice. Accustomed to being invisible to society and likely reduced to living near the ground, the woman reached out to touch the border of the Savior’s robe as he passed by.

Luke tells us that “immediately” the woman knew she was healed physically (v. 44). The Savior’s Atonement, however, extends beyond mending physical pain. He heals broken hearts and sick souls. He makes us whole, spirit and body. At that very moment she knew her body was healed, and Jesus turned to ask, “Who touched me?” (v. 45) The surrounding crowd was oblivious to what was happening. This was between the woman and the Lord. Jesus had a further gift to offer to this woman—but it would require even greater faith on her part. By touching merely the hem of his garment, the woman may have believed that she could be healed without rendering the Savior unclean and without calling down further denunciation and disgust from her neighbors. Now she must stretch her faith to publicly acknowledge what she had done.

After confessing before the townspeople, including a leader of the synagogue, that she was the one who touched him, the Savior called her “daughter” (v. 48). Because of her exceeding faith in him, Jesus openly numbered her among his family and pronounced her whole. She was healed both inwardly and outwardly.

As one of the awestruck bystanders who witnessed this miracle, Jairus suddenly received word, “Thy daughter is dead; trouble not the Master” (v. 49). To him, Jesus said, “Fear not: believe only, and she shall be made whole” (v. 50). How different did these words of assurance sound to Jairus after witnessing this woman’s great faith? Was anything too hard for the Lord? When we wholeheartedly come to Christ in our distress, knowing that he is our only hope, he renews, enlarges, and enhances the quality of our lives through his atoning blood.

Mary Magdalene

In all but one of the twelve times that Mary Magdalene is mentioned in the four Gospels, she is alone or the first of a list of women. The sole exception is in John’s account of the women at the Crucifixion, when the mother of Jesus is identified first (see John 19:25). The primacy of her name in these lists and the frequency of her mention suggest that Mary Magdalene was a leader among the women. Perhaps that is one reason that Luke specifically named her as one of the Galilean women who ministered to Jesus in his travels and the one out of whom Jesus cast “seven devils” (Luke 8:2).

Mary’s ailment involving seven devils may say more about the magnitude of Christ’s power to heal than her previous spiritual, emotional, or moral health. The number seven in scripture often connotes completeness and wholeness. In announcing Mary’s cure, Luke may simply be confirming that through the power of Christ, Mary was completely healed, she was made whole, or that she was completely liberated from her illness.[8]

In all four Gospels, Mary Magdalene and other Galilean women followed Jesus to Jerusalem where they became active witnesses of his Crucifixion.[9] As sheep without their shepherd, they joined the burial procession to observe where the body was buried and perhaps to observe which burial procedures were completed. Scripture implies that time did not allow for the customary sprinkling of spices and perfumed ointment on the strips of cloth used to wrap around the body prior to burial.[10] Because women were typically the ones who prepared and applied the fragrances, the women of Galilee may have concluded the need to return after the Sabbath for this purpose.

The Gospel narratives as well as traditions that preceded their writing imply that Mary Magdalene and other women from Galilee were the first to discover the empty tomb early on that first Easter morning.[11] Shortly afterward, other disciples witnessed the empty tomb and departed again, filled with their own questions and desires to understand what had occurred, leaving Mary Magdalene alone at the scene. The Gospel of John directs us to follow her quest and subsequent revelation, but no doubt other disciples could testify of their own parallel experience. Mary remained stationed at the empty tomb, seemingly determined not to depart until she learned what had happened to the body of Jesus.

Mary Magdalene did not recognize the Savior when he first appeared and spoke to her, calling her by a nonspecific term, “Woman” (John 20:13). She assumed that he was the gardener. Was her eyesight sufficiently blurred because of her tears, or had Jesus’ physical appearance changed to obstruct recognition? Importantly, Mary did not comprehend the Savior’s Resurrection when she discovered the empty tomb or even when she saw the resurrected Christ with her natural eyes. Perhaps the risen Lord wanted her to first know him through her spiritual eyes and ears. In a similar way, the two disciples on the road to Emmaus could not recognize the resurrected Christ because their “eyes were holden” (Luke 24:16). Perhaps the Lord’s use of the generic term “woman” can allow each of us, whether man or woman, to put ourselves in Mary’s place. Does Mary Magdalene exemplify the Lord’s desire for each of us to know him first by the witness of the Spirit?

When the Lord said her name, “Mary,” something clicked in her, and her spiritual eyes were opened (John 20:16). Suddenly her encounter with the resurrected Lord had become very personal. In an example of what Jesus taught by way of metaphor in John 10, Mary heard the voice of the Good Shepherd when “he calleth his own sheep by name, and leadeth them out” (John 10:3).

Addressing him as her Master, Mary must have instinctively reached out to him and touched him in some way because the Lord’s response, “Touch me not,” directed her to discontinue whatever it was that she was doing (John 20:17).[12] Other translations of the Savior’s directive are, “Don’t cling to me” or “Don’t hold me back,” which is reflected in the Joseph Smith Translation, “Hold me not.” Perhaps Mary anticipated that Jesus had returned to remain with his followers forever and resume their association. In her anxious desire not to lose him again, she wanted to cling to him to keep him there.

He had to leave again, because he had not yet ascended to his Father. One final event in his great victory—returning to the presence of his Father—remained to be accomplished. As he has promised each of us if we come in faith to him and apply his atoning sacrifice in our lives, he will bring us to be “at one” with the Father again.

Many have asked why Mary Magdalene received this remarkable experience. We could just as easily ask, why not? We do not need a unique calling, title, or relationship with the Savior different from any other disciple to receive a spiritual witness. We need a broken heart, faith in him, and an opportunity for him to teach us. If for no other reason, she may have received this blessing simply because she lingered in a quiet spot rather than running off to talk with others. Some of our Church leaders have observed that we would have more spiritual experiences if we didn’t talk so much about them.[13] Mary Magdalene teaches us to be still and learn that he is God (see Psalm 46:10; D&C 101:16).

Conclusion

In large measure, the women of Galilee remain anonymous, thereby putting the focus and importance where it should be—on Jesus Christ. In a personal and very palpable way, each of those women was a recipient and eyewitness of the Savior’s sacrifice not only at the end but during his mortal ministry. The Atonement was efficacious in their daily lives in Galilee. The enduring discipleship in each of these women bears witness to the retroactive and infinite power of the Atonement.

The women of Galilee also remind us that God loves all his children and is no respecter of persons, that men and women are alike unto him, and that lack of a title or position of authority does not exclude someone from a remarkable spiritual witness. Through the power of the Atonement in experiences that prefigured the Savior’s own death and Resurrection, a woman—the widow of Nain—received her only son back to life, and a man—Jairus—witnessed his only daughter die and then live again. And while pondering the meaning of the empty tomb, Mary Magdalene received the visit of the Lord, as did his chosen Apostles.

Finally, the women of Galilee prod us to use our agency wisely to come to him, no matter how hopeless our circumstance or how marginalized we may feel in society. Without fanfare or many words, they reinforce the poignant principle that it is by hearing the Lord’s teachings and doing them that we join his family, rather than claiming privilege through notable acquaintance or family ties.

During the weeks following the Savior’s Resurrection, “the women and Mary the mother of Jesus” were numbered among the 120 faithful disciples of Christ (Acts 1:14). When these disciples bore witness “in other tongues” (Acts 2:4) of the “wonderful works of God” (v. 11) on the day of Pentecost, the Apostle Peter explained the phenomenon by citing an ancient prophecy: “And it shall come to pass in the last days, saith God, I will pour out of my Spirit upon all flesh: and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, . . . and on my servants and on my handmaidens I will pour out in those days of my Spirit; and they shall prophecy” (vv. 16–18; see also Joel 2:28–29).

In the meridian of time, the Church of Jesus Christ commenced after multitudes heard both men and women bear witness of their Redeemer. Our recognition of the breadth of the Savior’s power will likewise increase when we hear and appreciate the testimonies of all those who know the Lord—even those whose perspective may be different from our own. When both men and women fervently testify of the stunning reality of the Atonement in their lives, we are all blessed.

Notes

[1] Vasiliki Limberis, “Widow of Nain,” in Women in Scripture, ed. Carol Meyers (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2000), 439–40.

[2] Barbara Reid, Choosing the Better Part? Women in the Gospel of Luke (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1996), 113.

[3] Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Gospel According to Luke I–IX, Anchor Bible, vol. 28 (New York: Doubleday, 1981), 689.

[4] I. Howard Marshall, Commentary on Luke, New International Greek Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1978), 308–9.

[5] Kenneth L. Barker and John R. Kohlengerger III, The Expositor’s Bible Commentary—Abridged Edition: New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1994), 219–20; Raymond E. Brown, Karl P. Donfried, Joseph A. Fitzmyer, and John Reumann, Mary in the New Testament (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1978), 154–57; Fitzmyer, The Gospel According to Luke, 429–30.

[6] Fitzmyer, The Gospel According to Luke, 745.

[7] Reid, Choosing the Better Part? 139.

[8] Reid, Choosing the Better Part? 126.

[9] Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Gospel According to Luke X–XXIV, Anchor Bible, vol. 28A (New York: Doubleday, 1985), 1521.

[10] F. F. Bruce, The Gospel of John (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1983), 379.

[11] See Matthew 28:1–6; Mark 16:1–6; Luke 23:55–24:10. In John 20:1, Mary Magdalene alone discovers the empty tomb. In her report to the Apostles in the following verse, however, she states, “we” do not know where he is, implying that others accompanied her in making this initial discovery, as the synoptic Gospels report; see also Raymond E. Brown, The Gospel According to John XIII–XXI, Anchor Bible, vol. 29A (New York: Doubleday, 1970), 977–78, 1001. Rather than suggesting that the women returned to anoint the body with fragrances, the Gospel of Peter posits that they came to appropriately “weep and lament” for the loss of a loved one, as “women are wont to do for those beloved of them who die” (vv. 50–52; in W. Schneemelcher, ed., Robert McL. Wilson, trans., New Testament Apocrypha [Louisville, KY: John Knox, 1991], 1:225).

[12] Brown, The Gospel According to John XIII–XXI, 992; Bruce, The Gospel of John, 389–90.

[13] Neal A. Maxwell, quoting Marion G. Romney, in “Called to Serve,” BYU 1993–94 Devotional and Fireside Speeches (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1994), 137.