“As Far as It Is Translated Correctly”: Bible Translation and the Church

Daniel O. McClellan

Daniel O. McClellan, "'As Far as It Is Translated Correctly': Bible Translation and the Church," Religious Educator 20, no. 2 (2019): 52–83.

Daniel O. McClellan (dan.mcclellan@gmail.com) was a scripture translation supervisor for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and a doctoral candidate in theology and religion at the University of Exeter when this was written.

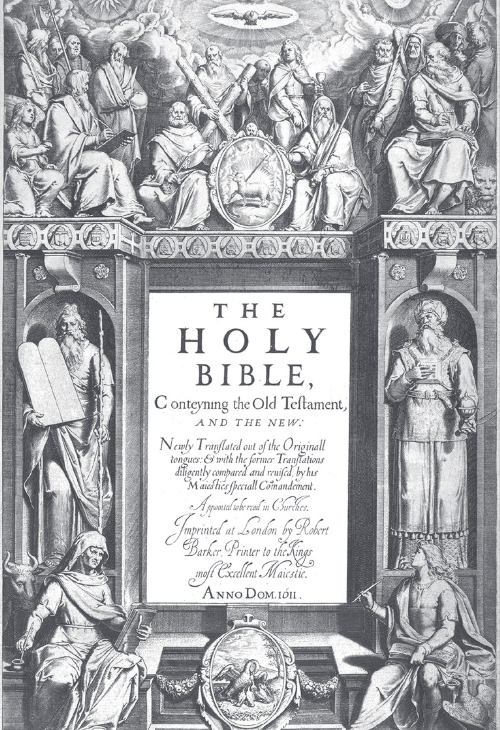

The title page explains how the King James Version was to be used: “Appointed to be read in Churches.” This meant it was intended to be read out loud from the pulpit by educated and experienced readers.

The title page explains how the King James Version was to be used: “Appointed to be read in Churches.” This meant it was intended to be read out loud from the pulpit by educated and experienced readers.

The publication of Thomas A. Wayment’s The New Testament: A Translation for Latter-day Saints is a significant event that occasions not only a close examination of his work but also a discussion of how it fits into the complex relationship The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has long shared with Bible translation.[1] If the Book of Mormon is the keystone of our religion, the King James Version of the Bible is certainly its linguistic cornerstone. The scripture and other revelations that flowed from the Prophet Joseph Smith and his successors in the early days of the Church were consistently couched in an archaizing English that resonated with the King James Version (hereafter KJV) and frequently drew from its lexical and conceptual frameworks. While the Prophet and early Church leaders and members felt no particular obligation to the KJV as a translation, its role in framing the Restoration wove it deeply into the very fabric of Latter-day Saint ideology, which granted it de facto priority of place. That place has motivated a variety of defenses of the position of the King James Version that have since granted it a quasi-canonical status, but as the Church continues to grow around the world and to transition into a truly global organization, its commitment to the KJV does not come without significant complications that have largely escaped scrutiny. The goal of this review article is to examine some of the more salient of those complications and then address Wayment’s volume and the way it bears on them.

Goals in Bible Translation

Bible translation involves navigating a complex spectrum of linguistic, textual, literary, historical, rhetorical, traditional, semantic, and other tensions.[2] Before any of these tensions can be resolved, though, they have to be prioritized based on the particular goals of the translation. One of the most prominent contemporary theories of translation, Skopos theory, observes that translation is a purposeful activity and that quality must be measured against a translation’s purpose, or its intended functions within a target audience.[3] Ideally, these functions are described in a translation brief, which may be created by the translator(s) or by those commissioning the translation. The translation succeeds to the degree it executes the functions described in the brief, and the more detail contained in the brief, the easier the decisions facing the translator become and the easier assessment of quality becomes. Because a Bible (or portions of it available in translation) may serve a wide variety of functions, there are a number of different ways to approach its translation. This section considers three such approaches.

For some, a Bible translation may be intended to function primarily as a missionary tool. In such cases, a translator will want to use more generic terminology, avoid in-group jargon, and usually aim for maximum accessibility (although considerations regarding the target audience will indicate the optimal degree of accessibility). Proselytizing among underprivileged segments of a society or among second-language speakers of a language of wider communication will demand far more accessibility than it would among educated first-language speakers. The United Bible Societies have moved in this direction since the 1960s, prioritizing naturalness and clarity so that readability is optimized. This approach demands more decisiveness in interpretation, and such translations run the risk of misinterpreting passages or losing semantic content as the source text is accommodated to the target culture.[4] A central concern with such translations is finding the sweet spot between bringing the meaning of the source text to the readership where it is and forcing the readership to expend the time and cognitive effort to approximate the meaning of the source text. Concerns for reception become key here. Will the target audience be unwilling or unable to do the work, or will they reject a translation that does all the work for them, and perhaps in a way they do not like? Many readers feel the challenge of excavating meaning from a difficult text is precisely what leads to more and deeper insights.

For some, a Bible translation may be intended to serve primarily institutional functions, such as administration, education, managing reputation, or any one of a number of other functions. In-group jargon might be necessary for such a translation, as well as avoiding certain terminology that might overlap with competing groups or conflict with the goals of the institution. The specific source texts used for the translation and the rendering of specific passages may be more important to the interests of the institution, particularly if intended for the classroom or the pulpit.[5] The first edition of the KJV is a handy illustration of precisely this kind of translation. While there were a variety of reasons for the project,[6] the title page explains how the King James Version was to be used: “Appointed to be read in Churches.” This meant it was intended to be read out loud from the pulpit by educated and experienced readers.[7] Its large size (11 × 16 inches), high cost, archaizing black-letter type, cadences, formal and outdated language, even its overwrought punctuation, signaled the translation’s institutional function and limited the accessibility that its immediate predecessors had worked to expand.[8] This was not a Bible for the home or the mission field; it was a Bible for the pulpit (and was frequently chained to it).[9]

The conceptual framework of “hospitality” is sometimes employed to help understand and critique how institutionally oriented translations function. As a postcolonial metaphor, hospitality relates to the way a “host” and a “guest” play their respective roles to meet social expectations as well as to further their own agendas. For example, Bible translation agencies often explain their presence in developing countries as a response to an invitation, framing themselves as guests and the target language group as host. These guests have agendas of their own, of course, as do the hosts, and unless those agendas are openly acknowledged, the two sides will play their roles in whatever ways they feel necessary to best serve their interests.

Page from a 1602 Bishops Bible with marginal notes showing a King James translator’s revisions.

Page from a 1602 Bishops Bible with marginal notes showing a King James translator’s revisions.

An example from an outdated but influential Setswana translation of the Bible called the Wookey Bible (1908) illustrates these dynamics.[10] The translation renders the Greek δαιμόνιον (daimonion), “demon,” with Badimo, which is a Setswana word that refers to sacred ancestral spirits commonly involved in divination and healing. With this rendering, Alfred Wookey took rhetorical aim at a central symbol of Batswana culture, no doubt viewed as antithetical to the Christian gospel.[11] The guest thus sought to use the host’s own language to alter the host culture. The host’s own interests were not entirely undermined, however. Despite the denigration of the sacred ancestral spirits, the translation became deeply embedded in the culture by being employed precisely as a tool of divination and faith healing. Batswana use random passages from the Bible to divine spiritual health and means of healing, appealing to both Jesus and the Badimo in the process.[12] While the majority of Christians live in the global south, the vast majority of resources employed by Christian groups is concentrated in the global north, meaning institutionally oriented translations of the Bible will continue to reify host-guest relationships that will best be served through open acknowledgement of institutional agendas. Similar power dynamics have long been at play in the Church’s own scripture translation processes.

A Bible translation may also be a prestige project for the translator, or aimed at primarily academic or literary goals. Accessibility is usually not the goal here, but rather displaying the beauty of the text and often even subverting institutional terminology or hermeneutics. Two recent examples are David Bentley Hart’s translation of the New Testament and Robert Alter’s translation of the Old Testament.[13] Both translations attempt to dislodge the text from the strictures of tradition and more faithfully reflect its linguistic idiosyncrasies. Hart’s New Testament aims to reproduce the experience of the original Greek readers, rendering polished Greek in polished English and clumsy or stilted Greek in clumsy or stilted English.[14] Traditional terminology and readability are sidestepped in favor of hyperliteralism and eclecticism. Similarly, Alter aims to capture the beauty and simplicity of the poetry and prose of the Hebrew Bible, and he is willing to sacrifice readability in order to force the English into a more compact Hebrew mold.[15] In a sense, both translations make the text more alien in order to tease out a more concerted and focused effort at comprehension and appreciation, which can certainly facilitate a closer approximation to the intended meaning but also renders that meaning less accessible to those without the requisite skills, resources, or motivations. Because both translations are primarily oriented toward academic goals, they avoid concerns for devotional or liturgical use, as well as their accessibility to less-educated or second-language speakers of English.

In sum, a translation’s quality is primarily contingent on what, precisely, it is intended to do, and translations can do many different things. One effect this consideration has had on Bible translation over the last several decades is to compel institutions and translators to commit more attention to the ways the Bible functions and which functions they want to prioritize.[16] The Church’s relationship with the KJV and with non-English Bible translations, however, has not been characterized by particularly thorough consideration of these dynamics, although there is a consistent and de facto prioritization of institutional functions and goals that not infrequently conflicts with the different ways and reasons Latter-day Saints engage with the Bible.[17] While most English-speaking Latter-day Saints are content to read the KJV without concern for institutional versus individual functions and goals, there are complications that can and do bubble to the surface.

The KJV and the Church

The KJV is not, strictly speaking, a translation, but a revision of the 1602 edition of the Bishops’ Bible, itself a revision of other revisions going back to the translations of William Tyndale and Miles Coverdale from the 1520s and 1530s.[18] According to the translators, rather than make a bad translation good, the goal was to “make a good one better.”[19] In what sense it was intended to be “better” is up for debate, but it did not stray far from its base translations. One study estimates 84 percent of the KJV’s New Testament preserves Tyndale’s words exactly.[20] The note to the reader states that the translation was intended to be understood by “even the very vulgar,”[21] but if democratizing the text was actually a goal, they were not particularly successful. Two linguistic factors worked directly against democratization: (1) they were revising an almost century-old translation already considered unrepresentative of then-contemporary English,[22] and (2) the particular translation philosophy compelled an atomistic and overly literal translation that frequently resulted in awkward diction.[23]

Paradoxically, these two factors significantly increased the interpretive flexibility and dynamism of the Bible. Similar to the way a more alien text compels a more concerted effort at comprehension, outdated language and foreign syntax mitigate clarity and inject a great deal of ambiguity into the text, which allows motivated readers to arrive at a variety of different readings. Many critical readers will clutch their pearls at such a notion, but for those who take a more “Liahona” approach to the scriptures and engage them to find guidance and answers to their own personal pursuits and struggles, this makes for a much more dynamic fount of inspiration and revelation. This has a great deal of salience for many English-speaking Latter-day Saints,[24] although in the evolution of translation goals and philosophies it might be characterized as more of a spandrel or exaptation than an adaptation.[25]

The KJV was not particularly well received upon publication in 1611, but by the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, it became authoritative within the Church. This gave it liturgical and literary purchase that put it front and center when, a century later, a surge in antiquarian tastes entrenched a view of the Bible as the standard for learning and teaching the English language.[26] While changes had been made in each printing of the KJV, three influential revisions were published around the 1760s, with Benjamin Blayney’s 1769 edition—which is the base text for Latter-day Saint editions of the Bible in English—achieving preeminence. A similar process would be repeated a century later when writers, “seeking the patina of biblical authority,” brought some of the outdated language of the KJV back into vogue.[27] As Gordon Campbell notes, “It was in this period that readers began to speak of the ‘majesty’ of the KJV, and of its cadences.”[28] These accidents of history have embedded the language of the KJV deep within modern English’s linguistic foundation, which has obscured much of its outdated language and linguistic shortcomings and given rise among certain groups to the perception of its unique elegance and beauty.[29]

Throughout the nineteenth century, the Church’s use of the KJV might be characterized as more circumstantial than prescriptive.[30] Many early Latter-day Saint leaders, including the Prophet Joseph Smith, felt no particular obligation or commitment to the KJV. They would refer generically to concern for careful translation but almost never to the particular qualities of the KJV itself. This early ambivalence is also evinced in the eighth article of faith (“We believe the Bible to be the word of God as far as it is translated correctly”), as well as the Prophet’s own revision of the text, which introduced thousands of changes. Institutional devotion to the KJV was an incremental process that began with the Reorganized Church’s publication of an edition of the KJV called The Holy Scriptures (1867) that incorporated all the Prophet’s revisions.[31] Many Latter-day Saints distrusted the new edition, believing it had been significantly altered to serve the Reorganized Church’s interests, which incentivized the explicit assertion of the KJV as Latter-day Saints’ preferred Bible translation.[32] The conservative and overwhelmingly Protestant background of most Church members only further entrenched this preference in response to late nineteenth century Catholic criticisms of the KJV and early twentieth century criticisms rooted in modern biblical scholarship and the Bible revisions it was producing. As Armand L. Mauss has observed, the Church’s relationship to the KJV was a means of differentiation in the nineteenth century, but a means of assimilation in the early twentieth.[33]

The clearest turning point toward articulation of a formal preference for the KJV came with President J. Reuben Clark’s 1956 book, Why the King James Version? President Clark’s book marshaled some of the most authoritative conservative biblical scholarship of the day to fiercely defend the KJV’s New Testament against critical scholarship and more recently published translations of the Bible, most notably the 1952 Revised Standard Version (RSV).[34] Philip Barlow distilled President Clark’s case down to five main arguments. For President Clark, the KJV (Authorized Version) was “(1) doctrinally more acceptable, (2) verified by the work of Joseph Smith, (3) based on a better Greek text, (4) literarily superior, (5) the version of Latter-day Saint tradition, and (6) produced by faithful, prayerful churchmen who were amenable to the Holy Spirit rather than by a mixture of believing and unbelieving, or orthodox and heterodox, scholars.”[35]

The majority of the volume is dedicated to defending the KJV’s source text and translation decisions, but prophetic authority was marshaled through the comparison of different translations of New Testament passages with the KJV and with the Prophet Joseph Smith’s inspired revision.[36] Overwhelmingly—and, as a revision, unsurprisingly—the KJV hewed more closely to the Prophet’s revision than to any other translation. This line of argumentation, in contrast to others, began to arrogate a degree of inspiration to the KJV. Elder Mark E. Petersen made the case more explicitly regarding the Book of Mormon’s relationship to the KJV in his 1966 book, As Translated Correctly:

Quotations from ancient Jewish prophets appearing in the Book of Mormon are the most correct Old Testament passages in existence today. They were copied onto the gold plates directly from the plates of brass, and translated by the gift and power of God as a part of the Book of Mormon. And yet—these passages resemble the King James translation more than any other Bible version. This gives reason to believe that indeed the Lord did have a hand in the translation of the King James version. . . . Not one of the modern versions can match the language of the brass plates quotations as the King James version does.[37]

The KJV’s literary superiority was one feature of President Clark’s argument that continues to be employed today. He heavily criticized scholars who promoted the idea that the Greek of the Gospels and the rest of the New Testament was a common, everyday Greek (an idea Wayment promotes in his “Note to the Reader”). After listing several of the miraculous works of the Savior, President Clark comments, “All are not worthy, the Extreme Textualists tell us, to be told in the magnificent language and poetry of the Old Testament. They say an ‘elaborate, elegant style’ is unsuited for the account of these mighty works and teachings, ‘and in proportion as it is rendered in a conscious literary style, it is misrepresented to the modern reader.’ All this they tell us. . . . The whole effect of the work of these Revisers seems to be to break down Christ, take away his divinity, make him just man, though an exceptional one.”[38] This argument does not so much address the legitimacy of the case being made by these scholars as it suggests that the prose of the KJV appropriately honors and glorifies the Savior’s words and deeds by articulating them in a higher literary register. To appeal to more common language is to hold back that honor, effectively lowering Christ and his divinity.[39]

The contemporary Church’s position is best represented by the First Presidency’s 1992 statement regarding the KJV as a translation, which suggests that the KJV’s integration into the linguistic and doctrinal foundations of the Restoration is the primary consideration: “The Lord has revealed clearly the doctrines of the gospel in these latter-days. The most reliable way to measure the accuracy of any biblical passage is not by comparing different texts, but by comparison with the Book of Mormon and modern-day revelations. While other Bible versions may be easier to read than the King James Version, in doctrinal matters latter-day revelation supports the King James Version in preference to other English translations.”[40]

Among other things, this statement demonstrates the primarily institutional orientation of the Bible’s function, as well as its subordinate status to Restoration scripture. It is not so much what the KJV teaches or how clearly it does so that makes it preferable but how it reinforces and integrates Restoration scripture and modern-day revelation. Because of that role, the KJV is really under no serious threat of displacement, but the practical implications of this priority merit discussion.

The KJV and the Church’s Messaging

No living person speaks the English of the KJV, though we commonly approach it as if we did. This is a source of one of the main complications of our commitment to it: we frequently misunderstand it. Now, to the degree we understand scripture to function as a facilitator of the Spirit or as a personal catalyst for inspiration, creative and dynamic interpretation can be an asset (and our lack of facility with KJV English certainly stimulates this). However, for a global Church that publishes Bible-interpreting material in almost two hundred languages, prioritizing creative interpretation can complicate things.

A recent example of how misunderstanding can complicate the Church’s international messaging comes from a “Ministering Principles” article from July 2018 entitled “Reach Out in Compassion.”[41] The subtitle reads “As you follow the Savior’s example of compassion, you will find that you can make a difference in others’ lives.” This is a reference to Jude 1:22, which is partially quoted in the first paragraph: “An assignment to watch over others is an opportunity to minister as the Lord would: with ‘compassion, making a difference’ (Jude 1:22).”[42] This reading interprets “making a difference” as exercising some kind of positive influence, which is a wonderful message, but it misunderstands the archaic English of the passage. The KJV translators were rendering a Greek verb, διακρίνω (diakrinō), which usually means “differentiate” or “separate,” and those translators interpreted the participle as an adverbial phrase. They used the phrase “making a difference” to suggest we should exercise discernment regarding to whom we show compassion.[43] The incidental overlap with a contemporary English idiom, however, facilitated an entirely novel reading.

The difficulties did not end there, however, as a result of another complication of our commitment to the KJV: its widening divergence from contemporary translations and scholarship. The “Ministering Principles” article was sent out for translation to over seventy different translators who promptly opened their Church-preferred non-English Bible translations—including the Church-published Spanish and Portuguese editions—and found yet another rendering with no relevance to the article’s message: “have compassion on those who doubt.” There is a reason for this. Most contemporary Bible translations are based on more ancient and reliable manuscripts of the Greek New Testament than those available to the translators of the KJV.[44] In these more reliable manuscripts, the participle is in the accusative case, meaning it is the object of the verb, not an adverbial phrase. Additionally, many scholars believe the verb διακρίνω could be used in the New Testament to mean “waver” or “doubt.”[45] Most contemporary translations thus interpret the text to be commanding compassion toward those who are wavering or torn between allegiances.[46] The translators of the “Ministering Principles” article had to decide on their own how to resolve the disparity, and the majority of them simply translated and cited the English KJV. This solves their problem but leaves members of the Church who do not speak English wondering about the discrepancy, often assuming their Bibles are inferior.[47] This is a common occurrence in the translation of our magazines, lesson manuals, and general conference addresses. The consistent deference to the English KJV over and against the Bibles recommended to non-English-speaking members reinforces for many a view of the KJV as superior, a view of the Church as a staunchly American institution, and a view of other translations as flawed.

This last concern highlights a further complication of the divergence from other translations. As contemporary Bible translations deviate more and more from the source texts and the translation philosophies of the KJV, fewer and fewer translations that reflect the KJV’s textual and translation profile are available for the Church to recommend and source for its non-English-speaking membership. As a result, contemporary Bible translations with little relationship to the KJV tradition are more commonly being preferred, and this discrepancy sometimes draws concern from members and leaders of the Church. For instance, the Church’s preferred German translation, the Einheitsübersetzung, renders Job 19:26b—as do many others—as “without my flesh, I shall see God” (ohne mein Fleisch werde ich Gott schauen). The familiar “yet in my flesh I shall see God” has been turned on its head, but it is a perfectly legitimate rendering of the Hebrew, it makes better contextual sense, and it is not doctrinally inaccurate (cf. Alma 40:11–12; Ecclesiastes 12:7). It also, however, deprives us of an important Old Testament witness to the Resurrection and creates issues for German-speaking members when, say, a lesson manual discussing the Resurrection directs them to this passage. Although there are no easy resolutions to these issues, it is crucial that those writing material for the Church be aware of them. While internationalization and localization are beginning to receive more attention, they continue to be subordinated to English content creation.

Another feature of some contemporary translations that frequently causes concern is the omission of passages from the New Testament. I heavily criticized this practice myself as a missionary in the Uruguay Montevideo Mission. In my view, this could represent only the active and willful excision of the plain and precious truths of the gospel.[48] The reality of the situation is quite a bit different, though. The passages that are removed do not appear in the earliest and most reliable manuscripts (which can predate the manuscripts underlying the KJV by a thousand years), and in some cases we can even document their origin in marginal notes that would later be transposed into the scriptural text itself.[49] This raises a question with which Bible translators frequently grapple: should a verse a translator knows to be a late interpolation be removed if it is a well-known and important part of a faith community’s discourse? Put more broadly, should concerns for reception and the target audience’s expectations take priority, or should the translator try to approximate as faithfully as possible the inspired author’s original message?

This is not a merely academic concern: our preferred Bible translations, and even the Bible translations we publish, come down on different sides of this question. For example, the Church’s preferred Italian translation, the Riveduta, omits a number of verses from the New Testament.[50] As just one example, in the story from John 5 of the man healed at the pool of Bethesda, the Riveduta skips directly from verse 3 to verse 5, relegating verse 4—which explains the angel’s role in disturbing the water—to a footnote. The note explains that the verse is missing from the earliest manuscripts and was most likely inserted later to explain the comment in verse 7 about the water being disturbed.[51] (Wayment omits the entire verse as well, stating in the footnote it is “confidently not original to the Gospel of John.”)

In preparing the New Testament text for the Latter-day Saint edition of the Bible in Portuguese, a different approach was taken. Although revising a translation of the New Testament that was based on more modern “critical text” manuscripts, the decision was made to defer to the Textus Receptus, for the sake of reception, except where a demonstrable error occurred.[52] (After all, we want members to read the translation.) Such cases of demonstrable error were rare, but an example is Luke 6:1, which the KJV renders “And it came to pass on the second sabbath after the first.” This is an attempt to make sense of the nonsensical compound Greek word δευτεροπρώτῳ (deuteroprōto), “secondfirst,” which is most likely the work of a copyist who came across two different readings and decided to punt by just combining them.[53] The Portuguese translation reads num sábado, “on a sabbath,” in agreement with the critical text.[54]

This is not a groundbreaking variant, but with the publication so far of two non-English Latter-day Saint editions of the Bible and many preferred Bibles that side with modern scholarship, the Church is putting significant institutional support behind translations that deviate in many and sometimes significant ways from the KJV.[55] This is significant and in no small part because it brings the nature of the KJV and our (sometimes dogmatic) commitment to it further into public focus, which will reverberate in as-yet-unknown ways throughout the worldwide Church. Wayment’s New Testament represents one such reverberation.

A translation's quality is primarily contingent on what, precisely, it is intended to do, and translations can do many different things.

A translation's quality is primarily contingent on what, precisely, it is intended to do, and translations can do many different things.

Thomas A. Wayment’s The New Testament: A Translation for Latter-day Saints

To assess Wayment’s volume, we should have a good idea of what it is trying to do. There is no systematic presentation of the intended function and target audience, but in his “Note to the Reader,” Wayment offers some clues. He states in the first paragraph that he is not intending the replace the KJV but to supplement it as “an invitation to engage again the meaning of the text for a new and more diverse English readership.” He hopes “it can become a study tool, an aid to inviting readers into the text so that new meaning can be discovered, and new inspiration can be found” (vii). In this way (and no doubt other unstated ways), Wayment’s volume acknowledges and ultimately defers to the institutional translation and institutional concerns. To whatever degree it does function as a supplement, it would serve to point the reader in new directions and new possibilities and equip them for a more informed and dynamic engagement with the text of the KJV.[56]

Before examining ways the volume sets out to accomplish this goal, I would like to highlight Wayment’s reference to “a new and more diverse English readership.” This statement may (subtly) make reference to the fact that a growing proportion of the membership of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that engages the scriptures in English comes to the text lacking significant exposure to KJV English. This may be because they are converts to the Church, because they are not first-language speakers of English, or because they are both. In some parts of the world, such as portions of Africa or Papua New Guinea, vernacular translations of Restoration scripture are not available, and English functions as a language of wider communication (LWC). In such areas, if the Church’s introductory materials are not available in a local language, there will be no preferred translation of the Bible, and members will primarily use the KJV.[57] In other places, such as the Philippines or parts of Europe, the Church has designated preferred Bible translations, but because English is relatively widespread, members often prefer to read the scriptures in English (even if they struggle with comprehension).[58] This preference is reinforced when they see the frequent deference to the English KJV that appears in Church publications translated from English.[59] If these groups are indeed in view, Wayment’s volume would be shouldering an enormous responsibility.

There are two vehicles for the accomplishment of Wayment’s goals for his volume: the translation itself and the study aids. The translation is conservatively executed in more contemporary, though by no means informal, English, which does clarify a number of passages and increases the accessibility of the translation.[60] A portion of the parable of the sheep and the goats should help illustrate the improved naturalness of the rendering (here, Matthew 25:31–40):

When the Son of Man comes in his glory and all the angels with him, then he will sit upon his throne of glory. And he will gather before him all the nations, and he will separate them one from another, just as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. And he will place the sheep on his right and the goats on his left. Then the king will say to those on his right, “Come, blessed of my Father and inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world. I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me a drink, a stranger and you took me in, naked and you gave me clothing, sick and you looked after me, in prison and you came to me.” Then the righteous will answer him, “Lord, when did we see you hungry and give you food, or when did we see you thirsty and give you a drink? When did we see you a stranger and take you in, or naked and clothe you? When did we see you sick or thrown in prison and come to you?” And the king answered them, “Truly I say to you, as you have done this to one of the least of my brothers or sisters, you have done it to me.”

This passage could be easily read out loud by an average reader without the usual fumbling over awkward word order and diction.

Where the KJV is not unusually awkward, Wayment’s translation tends to reflect its familiar prose. There seems to be a general and perhaps intentional resonance with the KJV, either to signal its supplementary status or to make the translation more palatable to those accustomed to KJV prose (or both). Matthew 1:19 is a handy example:

Textus Receptus:

Ἰωσὴφ δὲ ὁ ἀνὴρ αὐτῆς, δἰκαιος ὢν καὶ μὴ θἐλων αὐτήν παραδειγματίσαι, ἐβουλήθη λάθρα ἀπολῦσαι αὐτήν.

Wayment:

And her husband Joseph, being a righteous man and not wanting to make a public example of her, wanted to send her away privately.

2013 Latter-day Saint KJV:

Then Joseph her husband, being a just man, and not willing to make her a publick example, was minded to put her away privily.

NRSV:

Her husband Joseph, being a righteous man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace, planned to dismiss her quietly.

The word order and terminology are largely preserved in more contemporaneous English, and the choice of “privately” for λάθρα (instead of “quietly,” or “secretly”) stays with a cognate for the KJV’s “privily.” This will resonate with those familiar with the KJV while also sounding less foreign to those approaching the text without that familiarity.[61]

Whether as a result of this resonance with the KJV or out of concern for faithfulness to the source text, the text often hews closely to Greek word order, so one might challenge the consistency with which Wayment has “given preference to readability in place of reflecting a foreign language word order” (viii). This holds generally throughout the narrative portions of the translation (where that word order does not significantly affect comprehensibility in English). Here is John 11:1:

Textus Receptus:

Ἦν δέ τις ἀσθενῶν Λάζαρος ἀπὸ Βηθανίας ἐκ τῆς κώμης Μαρίας καὶ Μάρθας τῆς ἀδελφῆς αὐτῆς.

Wayment:

A certain man was ill, Lazarus from Bethany, from the village of Mary and Martha, her sister.

2013 Latter-day Saint KJV:

Now a certain man was sick, named Lazarus, of Bethany, the town of Mary and her sister Martha.

NRSV:

Now a certain man was ill, Lazarus of Bethany, the village of Mary and her sister Martha.

Wayment actually more directly reflects the word order of the Greek than does the KJV. The repetition of “from” in the appositional phrase in reference to Bethany (despite different Greek prepositions) is peculiar, and unlike the KJV and the NRSV, Wayment maintains the final position of “her sister,” which will strike some readers as awkward.[62]

Wayment tends to retain longer readings from the Textus Receptus that are omitted in the critical text, as with the story of the woman taken in adultery in John 7:53–8:11, although he does place them in double brackets and comments on the text-critical situation in the footnotes.[63] For smaller differences, some Textus Receptus variants are maintained without comment, as in John 17:1, where “Glorify your Son so that your Son may glorify you” includes the possessive pronoun in “your Son” where the critical texts have generally omitted it in favor of the definite article. In other places, however, Textus Receptus variants are omitted, and sometimes without comment, as in Mark 3:14, where Wayment describes the Apostles being given power to cast out demons but omits the reference to healing sicknesses (in agreement with the critical texts). The footnotes make no note of this omission.

Some of the problematic translation choices from the KJV are also remedied in Wayment’s translation, though most of these are easy corrections. For instance, the occurrences of “testament” for διαθήκη in Luke 22:20 and Hebrews 7:22 and 9:15 are changed to “covenant” by Wayment. In Romans 5:11, the KJV has “atonement” (the only New Testament occurrence) for καταλλαγὴν (katallagēn), which is a stretch.[64] Wayment joins most other contemporary translations in correcting it to “reconciliation.” The KJV renders “propitiation” (which refers to the appeasement of a deity) for ἱλαστήριον (hilastērion) in Romans 3:25. Classical/

There are some places where I still prefer the KJV’s renderings, either for aesthetic or interpretive reasons, but I would say these are in the minority. One example is an interpretive toss-up in Ephesians 4:8, where the KJV has “Wherefore he saith, When he ascended up on high, he led captivity captive, and gave gifts unto men.” Wayment renders, “Therefore, it says, ‘When he ascended on high he captured those who were captive; he gave gifts to men and women.’” My concern is the captives. As Wayment explains in his footnote, the passage quotes the Greek translation of Psalm 68:18, where αἰχμαλωσίαν (aichmalōsian), a feminine singular noun, could be understood as “captivity” or as an abstract reference to prisoners of war. Wayment prefers the latter, and that may very well be correct, but I find more depth and significance in the former.

The features of Wayment’s volume that may be considered “study aids” are legion. Among the more conspicuous is the formatting. Wayment’s volume sets the type in paragraphs (with different typesetting for the poetry), superscripts the verse numbers so they are largely out of the way, and includes quotations marks for dialogue. This all constitutes a significant departure from the division into separate indented verses familiar from all other Latter-day Saint editions of the scriptures. While subtle, this signals a different conceptualization of the function of the volume.[66] Divisions into verses makes it easier to scan a page and find a desired verse, which primarily facilitates the use of scripture as a reference tool, and particularly in public reading.[67] While this is frequently an important function of scripture, it is not the only way to engage the scriptures and certainly not a familiar one for newcomers to the scriptures.

The Bible and the Book of Mormon both constitute collections of a variety of different literary genres for which the text’s form is frequently endowed with rhetorical functions of its own. This is most conspicuous for poetry, where division into verses can help signal a variety of relationships that contribute to the broader semantic load conveyed by a text, but even paragraph or section divisions within narrative can help compartmentalize the text in ways that influence interpretation.[68] Section headings also aid in the division of sense units, and the inclusion in the headings of references to parallel passages of scripture is a much more convenient and efficient tool than a gospel harmony in the back of the volume. Wayment’s volume is more conducive to study of literary units as such, which (1) facilitates a much more reader-friendly approach (without being a formal Reader’s Edition), (2) provides an alternative to the atomism of the Latter-day Saint KJV, and (3) can hopefully help mitigate the slow creep of proof texting.[69]

One of the most informative features of the formatting is the italicizing of quoted scripture (with references in the footnotes).[70] Latter-day Saint editions of the Bible are notoriously stingy with their footnotes, and New Testament quotations of the Old Testament are not consistently or particularly thoroughly identified.[71] This has long deprived Latter-day Saints of much of the rich intertextuality with the Old Testament that was so critical to the New Testament authors’ conceptualizations and presentations of the identity and mission of Jesus Christ.[72] The most motivated students of scripture will ultimately tease many of these out, but little is lost by saving them the effort, as Wayment’s volume does.[73] Some noncanonical texts, like 1 Enoch, are even referenced where they are quoted (as in Jude 1:14), although 2 Maccabees 7, which is alluded to in Hebrews 11:35, is not referenced. Importantly, the notes also indicate intertextual relationships with the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants (although I note that the Book of Mormon is always alluding to New Testament passages and never quoting them). The inclusion and discussion of variants from Joseph Smith’s revision of the Bible will also be very helpful for more thorough study of the relationship between the two.[74]

Three other important study aids are the introductions before each book, the maps, and the explanatory notes. For the Gospels, the introductory sections discuss the author, the manuscripts, and the structure and organization of the book. These provide helpful context and orient the reader to the main themes of each Gospel, but I would have liked to have seen more detail, particularly for the discussions of structure and organization, which can be one of the most helpful interpretive keys for the nonspecialist reader. For the rest of the New Testament, the introductory sections address the author, their purpose for writing, and any salient connections to Latter-day Saint belief. The latter sections should help Latter-day Saints approach the texts with more enthusiasm and ultimately come to appreciate many of the more neglected books of the New Testament. The maps provide helpful orientation within the context of the narratives, rather than deep in the back of the book where they tend to be consulted independent of actual engagement with the texts. More could have been provided, but obviously space is a concern.[75]

Perhaps the most insight in the study aids is found in the explanatory notes. Rather than clutter up the text with superscripted footnote references (the verse numbers already occupy that space, anyway), the reader can simply look for the verse references in the footnotes to see what issues are discussed. In addition to the quotations, paraphrases, and allusions discussed above, these notes give more detail and background on literary, historical, and geographical contexts; comment on text-critical considerations; describe relationships with other texts from the Old and New Testaments; explain translation choices; and show where meaning is ambiguous or unclear. Rather than assert an answer for every potential concern, Wayment offers facts and observations and frequently leaves the decision to the reader. This open-endedness is where the reader will find some of the most help in applying more informed and dynamic interpretive lenses to their reading of the New Testament, both in Wayment’s volume and in the KJV. A simple example from Matthew 6:11–13 demonstrates how much additional information is available. This is the second half of the Lord’s Prayer:

Textus Receptus:

11 τὸν ἄρτον ἡμῶν τὸν ἐπιούσιον δὸς ἡμῖν σήμερον

12 καὶ ἄφες ἡμῖν τὰ ὀφειλήματα ἡμῶν ὡς καὶ ἡμεῖς ἀφίεμεν τοῖς ὀφειλέταις ἡμῶν

13 καὶ μὴ εἰσενέγκῃς ἡμᾶς εἰς πειρασμὸν ἀλλὰ ῥῦσαι ἡμᾶς ἀπὸ τοῦ πονηροῦ ὅτι σοῦ ἐστιν ἡ βασιλεία καὶ ἡ δύναμις καὶ ἡ δόξα εἰς τοῦς αἰῶνας ἀμήν

Wayment:

11 Give us enough bread for today,

12 and take away our debts, to the extent we have forgiven our debtors,

13 and do not lead us toward temptation, but save us from evil.

2013 Latter-day Saint KJV:

11 Give us this day our daily bread.

12 And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.

13 And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil: For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever. Amen.

NRSV:

11 Give us this day our daily bread.

12 And forgive us our debts,as we also have forgiven our debtors.

13 And do not bring us to the time of trial,but rescue us from the evil one.

Wayment’s notes on these three short verses explain:

6:11 The idea of bread for today, also rendered as daily bread, contains a subtle critique of amassing wealth for future needs. The teaching echoes Deuteronomy 8:3. Jesus may have been commenting on the Roman acceptance of amassing wealth. Luke’s translation of the saying (Luke 11:3) is more forceful in its teaching: give us our daily bread day by day. The word translated as daily appears nowhere else in the New Testament. Matthew avoids the typical Greek word for daily. Daily is translated as supersubstantialem in the Vulgate of Matthew 6:11 and means life-sustaining. Matthew’s wording equates financial debt with spiritual sin. 6:12 Matthew here prefers debts (also trespasses) to Luke’s sins (Luke 11:4). Matthew may have intended the idea of debts to represent the weight or impact of sin. Origen (died ca. 254 CE), an early patristic father who quoted the Lord’s Prayer, translated it as trespasses, using a different word than Matthew or Luke did. 6:13 Later manuscripts add the final sentence of the Lord’s Prayer, known as the doxology, that is familiar from other translations: For yours is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen. The manuscripts are not very reliable that support this reading, but a version of it is recorded in the Didache and 3 Nephi 13:13. A similar petition by David is found in Psalm 141:4. James 1:13 treats the theme of temptation, but in this verse it can also mean trial. Amen is a Hebrew word signifying agreement to something that is true and firmly agreed upon, although this prayer does not end with Amen unless the doxology is original.

Several lines of inquiry could be chased down just from these three footnotes, which not only explain the meaning of technical terms but reveal a number of contextual details that help us to better understand the doctrine being taught. This will enrich our engagement with not only the biblical texts but also the Book of Mormon and other Restoration scripture.

By way of critique, the absence of any discussion in the notes regarding the final clause of John 1:1 (“and the Word was God”) might be called a glaring omission. There is also a rather significant error is found in the note for Matthew 9:34, which mentions the rhetorical editorializing of the name Beelzebul. The note states that Beelzebub is the original name, meaning “Prince Baal,” and that Beelzebul is the revised name that means “lord of the flies.” This has it backwards, though. Zebub means “fly” in Hebrew and zebul comes from a Northwest Semitic word for “prince.”[76] The form occurring in the Old Testament (Beelzebub) is the editorialized name meaning “lord of the flies,” while the New Testament preserves the more original Beelzebul, “Prince Baal.” Some few inevitable infelicities aside, the notes will prove to make one of the most valuable contributions of the volume to a more intensive study of the New Testament.

Conclusion

Overall, despite my few very small quibbles, I consider Wayment’s New Testament a landmark publication that should be on the shelf of any English-speaking Latter-day Saint student of the scriptures. The translation is a more natural and up-to-date rendering of the text of the New Testament that displays clear resonances with the KJV while consistently incorporating advances in the scholarship. The study aids will be an invaluable supplement to the study of the New Testament. This will help escort the reader into a deeper and more dynamic understanding of the identity and mission of the Savior, as well as a fuller understanding and appreciation of the goals and methodologies of the inspired authors of the New Testament. The degree to which it will democratize the text of the New Testament for an audience to whom the KJV speaks in an alien language or for whom English may not be a first language remains to be seen, but it is a laudable effort nonetheless.

Some will challenge the need for and the value of this volume, but that will be more about protecting the past and its traditions than about serving the needs of the global Church now and into the future. In a fairly well-known quote, Brigham Young said the following about Bible translation: “Take the Bible just as it reads; and if it be translated incorrectly and there is a scholar on the earth who professes to be a Christian, and he can translate it any better than King James's translators did it, he is under obligation to do so.”[77]

This obligation has only grown as contemporary biblical scholarship has become more popularized and more accessible to members of the Church around the world. Church history has experienced a paradigm shift over the last few decades as the internet has democratized information in a way that has catalyzed a more candid and open curation of our past. The Joseph Smith Papers Project and the many publications that have sprung from it are just some examples of the fruit born of critical conversations about Church history. With two new Latter-day Saint editions of the Bible published in the last decade, new seminary and institute manuals, a BYU New Testament Commentary series, a redesigned, home-centered and Church-supported New Testament curriculum, and now an additional translation of the New Testament, perhaps the time has come for similar conversations regarding the Bible.

The scriptures function in a variety of different ways, depending on who is using them, in what contexts, with what methods, and for what purposes. (Unfortunately, as a community, we tend not to consider these dynamics.) Different translations, different formats, and different circumstances will serve these goals and methodologies in different ways. Strict adherence to a single translation in the service of institutional concerns constrains the degree to which scripture can meet these needs. There are no easy answers to these complexities, of course. Wayment’s volume certainly cannot resolve them all, but it can deepen the serious student’s capacity and understanding, and it can expand the text’s accessibility. No less significantly, it can help us begin those critical conversations about the nature of the Bible and the nature of our engagement with it.

Notes

[1] Thomas A. Wayment, The New Testament: A Translation for Latter-day Saints (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019).

[2] For an excellent discussion of some of these dynamics from a Latter-day Saint perspective, see Ben Spackman, “Why Bible Translations Differ: A Guide for the Perplexed,” Religious Educator 15, no. 1 (2014): 14–66. For perspectives from mainstream Bible translators, see the essays in Glen G. Scorgie, Mark L. Strauss, and Steven M. Voth, eds., The Challenge of Bible Translation: Communicating God’s Word to the World (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2003). On some of the complexities of resolving these tensions in translation, see Sarah Ruden, The Face of Water: A Translator on Beauty and Meaning in the Bible (New York: Pantheon Books, 2017), 39: “But the universal problem of ancient vocabulary is that it’s just a different animal, with a different set of habits. In modern English, as a rule, you make sharply conscious, committed choices in wording, assisted by that massive vocabulary; you can be quite exact in getting your point across, but the loss is that you pick one meaning and ditch others. That’s unless you’re being clever and ludic, making your readers puzzle and work and risking their irritation. . . . But in a typical important word in Hebrew or Greek Scripture, it’s all there at once, effortlessly: the obvious meaning on the surface, and some other, altogether different meaning that nevertheless resonates in the context.”

[3] See Hans Vermeer and Katharina Reiß, Grundlegung einer allgemeinen Translationstheorie (Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1984); Christian Nord, Translating as a Purposeful Activity: Functionalist Approaches Explained (Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing, 1997); Andy Cheung, “Functionalism and Foreignisation: Applying Skopos Theory to Bible Translation” (PhD diss., University of Birmingham, 2012).

[4] For example, the Mossi people of Burkina Faso have no interactions with ships and anchors, so Hebrews 6:19’s “sure and steadfast anchor of the soul” was accommodated to their culture as “strong and steadfast picketing-peg for the soul,” which worked wonderfully. See Lamin Sanneh, Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture, 2nd ed. (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2009), 231. Then there is the Inuktitut translation of “lamb,” which is a central metaphor in the New Testament. Sir Edward Evans-Pritchard famously reported that in order to make the concept understandable, they needed to find some kind of familiar conceptual equivalent and thus settled on “seal.” Seals are hunted animals, not domesticated, though, so this significantly alters the conceptualization of Christ as the “lamb of God” and of his followers as his sheep. See Edward E. Evans-Pritchard, Theories of Primitive Religion (London: Oxford University Press, 1965), 13–14.

[5] If the institution is engaged itself in missionary work, there will be overlap and tension between these approaches.

[6] A primary institutional goal was to replace the Bishops’ Bible (1568) as the official Bible of the Church of England and the Geneva Bible (1560) as the most popular translation. It was commissioned by King James in response to objections to the accuracy of the Great Bible (1539–40) and to his own concerns for the antimonarchist tenor of marginal notes of the Geneva Bible. For some details on those notes, which King James described as “very partiall, untrue, seditious, and savouring too much of dangerous and traitorous conceits,” see F. F. Bruce, The Books and the Parchments: Some Chapters on the Transmission of the Bible, rev. ed. (Westwood, NJ: Fleming H. Revell, 1963), 227–28. The king was also concerned for theological and ecclesiastical unity, and a new translation would be one to which the whole church could be bound. David Norton, A Textual History of the King James Bible (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 5–6.

[7] “The KJV was written to be read aloud in churches and homes, and so has rhythms appropriate to that mode of reading; that is why, to a modern ear (and a nineteenth-century ear), it sounds more like poetry than like the prose of a novel.” Gordon Campbell, Bible: The Story of the King James Version, 1611–2011 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 170. For a discussion of the importance of the text’s auditory consumption, see John S. Tanner, “‘Appointed to Be Read in Churches,’” in The King James Bible and the Restoration, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 118–37.

[8] “Readers sometimes find themselves tripping over its many tiny clauses that interrupt the flow of the text and occasionally make the meaning less clear. . . . When the translation was originally published and ‘Appointed to be read in Churches’ (1611 title page), its creators filled it with punctuation, believing that the congregational reading for which it was primarily intended would be enhanced by the short clauses, each set apart by a pause. Had they known that the Bible’s greatest use would eventually be with families in private homes, rather than in churches, perhaps they would have done otherwise.” Kent P. Jackson, Frank F. Judd Jr., and David Rolph Seely, “Chapters, Verses, Punctuation, Spelling, and Italics,” in Jackson, King James Bible and the Restoration, 106. See also Kent P. Jackson, “The English Bible: A Very Short History,” in Jackson, King James Bible and the Restoration, 11–23.

[9] Church curriculum’s transition to a “home-centered, Church supported” structure makes even more salient the concerns with an explicitly institutional translation of the Bible.

[10] This example is drawn from Musa W. Dube, “Consuming a Colonial Cultural Bomb: Translating Badimo into ‘Demons’ in the Setswana Bible (Matthew 8.28–34; 15.22; 10.8),” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 73 (1999): 33–59, cited by James Maxey, “Bible Translation as Hospitality and Counterinsurgency: Hostile Hosts and Unruly Guests” (paper presented at the Bible Translation Conference, 15 October 2013).

[11] The Church’s currently preferred Setswana Bible translation is a 1992 revision of the Wookey translation called the Baebele e e Boitshepo, executed by Batswana and published by the Bible Society of South Africa. There the word “demons” is rendered with mewa e e maswe, or “evil spirits.” There is, of course, an argument to be made for wanting a translation to correct false doctrine, but the Book of Mormon story of Aaron before the father of King Lamoni demonstrates an alternative approach. Rather than denounce his understanding of a “Great Spirit,” Aaron accommodated his beliefs and then built on them. Similarly, an idea of ancestral spirits being present in this world would not be alien to Latter-day Saints, even if there would be differences to resolve.

[12] Dube concludes, “In short, while colonial missionaries took control of the written ‘Setswana,’ they could not take control of the unwritten Setswana from the memories of Batswana readers and hearers. In this way, the Batswana AICs [African Independent Churches] readers resurrected Badimo from the colonial grave site where they were buried; they detonated the minefields planted in their world views and reclaimed their cultural worlds as life-affirming spaces.” Dube, “Consuming a Colonial Cultural Bomb,” 57.

[13] David Bentley Hart, The New Testament: A Translation (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017); Robert Alter, The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018).

[14] An example of the latter is Hart’s rendering of Revelation 1:3: “How blissful both that lector of and those listeners to the prophecy who also abide by the things written therein; for the time is near.” The main clause does not even have a verb. The KJV renders the Greek much less awkwardly: “Blessed is he that readeth, and they that hear the words of this prophecy, and keep those things which are written therein: for the time is at hand.” Wayment renders it “Blessed is the one who reads aloud, and blessed are those who listen to the words of this prophecy and who obey what is written in it, for the time is near.”

[15] Indeed, Alter believes “the pursuit of perfect clarity” constitutes “one of the great fallacies of modern translators of the Bible.” Robert Alter, “The Question of Eloquence in the King James Version,” in The King James Version at 400: Assessing Its Genius as Bible Translation and Its Literary Influence, ed. David G. Burke, John F. Kutsko, and Philip H. Towner (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013), 332–33. See also Robert Alter, The Art of Bible Translation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), in which Alter argues that “the Bible itself does not generally exhibit the clarity to which its modern translators aspire” (10; compare with Sarah Ruden’s comments in note 2) and that the King James Bible casts such an imposing shadow that “for an English translation to make literary sense it somehow has to register the stylistic authority of the 1611 version” (10).

[16] Just one example of how this leads to new ideas about Bible translation is Daniel Rodriguez, “Reframing Hospitality: Cognition, Social Bonding, and Mimetic Criticism,” Bible Translator 69, no. 1 (2018): 103–14. Among other things, Rodriguez highlights frameworks within evolutionary theory that hold that human language developed not as a means of transmitting information but as a means of facilitating social bonding and cohesion. This insight, combined with the conceptual framework of “hospitality,” may help tease out better methodologies and approaches for Bible translation organizations and teams.

[17] The Church’s internal policies related to the translation of Restoration scripture do more directly and carefully address the individual’s engagement with the scriptures. However, those policies do not directly bear on the Church’s approach to evaluating non-English Bibles or to preparing Latter-day Saint editions of the Bible in languages other than English. The latter are revisions of public domain editions of our preferred Bible translations. The policies guiding those revisions are distinct and are oriented in large part toward avoiding the perception of “Mormonizing” the Bible.

[18] Fifteen rules of translation were drafted, with the very first requiring that the Bishops’ Bible (which many disliked) “be followed, and as little altered as the truth of the original will permit.” For these rules, see Norton, Textual History of the King James Bible, 7–8. For a discussion of the Greek text used for the KJV New Testament, see Lincoln H. Blumell, “The New Testament Text of the King James Bible,” in Jackson, King James Bible and the Restoration, 61–74.

[19] Miles Smith, “The translators to the reader,” in The Holy Bible (London: Robert Barker, 1611), fol. ixr.

[20] There have been several such estimates, but for this number, see Jon Nielson and Royal Skousen, “How Much of the King James Bible is William Tyndale’s? An Estimation Based on Sampling,” Reformation 3, no. 1 (1998): 49–74.

[21] Miles Smith, “The translators to the reader,” 11.

[22] See Campbell, Bible, 73–79. Seth Lerer identifies the -th suffix on third person singular verbs (e.g., “taketh,” “becometh,” “proceedeth”) as just one element of the English language that was already absent from common usage in 1611. Seth Lerer, “The KJV and the Rapid Growth of English in the Elizabethan-Jacobean Era,” in Burke, Kutsko, and Towner, The King James Version at 400, 43–44.

[23] Regarding the prose of the KJV, Robert Alter comments, “The committees convened by King James adopted a translation strategy, adumbrated by Tyndale a century earlier, meant to create close equivalents for the Hebrew diction and syntax, and that resulted in a particular kind of forceful effect that was new in English.” Alter, “Question of Eloquence in the King James Version,” 331–32. For a discussion of the transmission of the text from Tyndale to the KJV, see David Norton, The King James Bible: A Short History from Tyndale to Today (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 33–53. Luther was much more successful at rendering the Bible into the common language of the day, largely because he was not revising an existing translation, because of his independence from institutional concerns and because of adherence to translation principles developed within humanism and the antimonarchal segments of the Reformation. On this, see Jeremy Munday, Introducing Translation Studies: Theories and Applications, 4th ed. (London: Routledge, 2016), 38–40.

[24] It is also one of the central principles of the contemporary translation of Restoration scripture. Principles of mainstream Bible translation call for the preservation of intentional ambiguities and the clarification of incidental ones, but for the Church, ambiguity is to be maintained wherever possible.

[25] “Spandrel” and “exaptation” are ways to refer to evolutionary byproducts or side effects of a given adaptation that increase fitness in a separate and “unintended” way. On these terms, see David M. Buss et al., “Adaptations, Exaptations, and Spandrels,” American Psychologist 53, no. 5 (1998): 533–48.

[26] On this process, see Norton, The King James Bible, 185–98. Already Bible translations were being produced to remedy the obsolete and outdated language of the KJV. The 1764 Quaker Bible included a list of such terms from the KJV. Even the famous American lexicographer, Noah Webster, published his own revision of the KJV in 1833 because he felt its outdated grammar and terminology made it difficult to understand. Updating the language of scripture was common even anciently. The Dead Sea Scrolls’ Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa), which dates to just before the time of Christ, represents a systematic updating of the syntax, orthography, morphology, and vocabulary of the much older book of Isaiah. Ronald Hendel and Jan Joosten, How Old Is the Hebrew Bible? A Linguistic, Textual, and Historical Study (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018), 54–55.

[27] The quote is from Lerer, who lists several words dismissed as obsolete in the eighteenth century that were revived in the nineteenth: “avenge, eschewed, laden, ponder, unwittingly, and warfare.” Lerer, “The KJV and the Rapid Growth of English in the Elizabethan-Jacobean Era,” 44, emphasis in original. See also David Norton, “The Bible as a Reviver of Words: The Evidence of Anthony Purver, a Mid-Eighteenth-Century Critic of the English of the King James Bible,” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 86, no. 4 (1985): 515–33. The revival of outdated words is also found in ancient Hebrew. For example, the particles טרם (“before”), פן (“lest”), and לקראת (“toward”) are common to Classical Biblical Hebrew, are mostly or entirely absent from Late Biblical Hebrew, and then are revived as archaisms in postbiblical texts like Ben Sira and the Dead Sea Scrolls. See Hendel and Joosten, How Old Is the Hebrew Bible?, 68–69.

[28] Campbell, Bible, 170.

[29] See, for example, David Daniell, The Bible in English: Its History and Influence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003); David Crystal, Begat: The King James Bible and the English Language (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); Robert Alter, Pen of Iron: American Prose and the King James Bible (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010). We even think of “thee” and “thou” as reflecting a more respectful tone although they were, in fact, the informal register when they were in use in the sixteenth century (see note 39). The use of these pronouns in the 1611 KJV was already outdated. Campbell, Bible, 73–75. Intentionally using outdated language to reflect the authority, beauty, or antiquity of older literature is sometimes called “pseudoclassicism.” On pseudoclassicism in ancient Hebrew, see Hendel and Joosten, How Old Is the Hebrew Bible?, 85–97.

[30] Perhaps the best discussion of this period is Philip L. Barlow, Mormons and the Bible: The Place of the Latter-day Saints in American Religion, updated edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 162–73.

[31] Barlow, Mormons and the Bible, 167–68.

[32] Barlow notes, “When copies of the published work, The Holy Scriptures, began to proliferate in Utah, various leaders at the School of the Prophets in Provo voiced the Church’s stand against the new revision: ‘the world does not want this [new Bible] . . . they are satisfied with the King James translation’; ‘The King James translation is good enough. . . . I feel to support the old Bible until we can get a better one.’” Barlow, Mormons and the Bible, 168, quoting the testimonies of G. G. Bywater and J. W. Fleming, recorded in the “Minutes of the School of the Prophets,” 6 July 1868, cited in Reed C. Durham Jr., “A History of Joseph Smith’s Revision of the Bible” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1965), 245–75. On Church members’ general opposition to the published version of the Prophet’s revision and the overturning of that opposition, see Thomas E. Sherry, “Robert J. Matthews and the RLDS Church’s Inspired Version of the Bible,” BYU Studies 49, no. 2 (2010): 93–119.

[33] “During the nineteenth century, the KJV provided a vehicle . . . for asserting the distinctiveness of the Mormons. . . . The KJV was there to be explored, to be compared with the new scriptures coming through the modern Mormon prophets, to be questioned, and to be revised, as necessary, no matter what the rest of the world might think. By contrast, during the first half of the twentieth century, the KJV served as a vehicle for Mormon assimilation. It provided the common scriptural ground for Mormons with the rest of the country (or, at least, with the Protestant establishment, which largely controlled the Mormon public image).” Armand L. Mauss, The Angel and the Beehive: The Mormon Struggle with Assimilation (Urbana, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 106.

[34] Not everyone was in agreement with this position. Note, for instance, Sidney B. Sperry’s comments from 1945: “We admit at the outset that for literary quality, for nobility, beauty, rhythm, and cadence, simplicity and melody, the King James Bible is, and will probably ever remain, supreme among English translations. On the other hand, the Authorized Version definitely lacks the accuracy of most modern translations, and suffers heavily from the fact that many of its words are so antiquated as not to be understood in the manner originally intended.” Sidney B. Sperry, “Modern Translations of the Bible,” Instructor, February 1945, 70.

[35] Barlow, Mormons and the Bible, 176.

[36] See J. Reuben Clark, Jr., Why the King James Version? (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1956), 315–417.

[37] Mark E. Petersen, As Translated Correctly (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1966), 49–50.

[38] Clark, Why the King James Version?, 381, quoting Edgar J. Goodspeed, An Introduction to the Revised Standard Version of the New Testament, ed. Luther A. Weigle (Chicago: International Council of Religious Education, 1946), 33.

[39] A similar notion is in circulation today regarding using “thee” and “thou” in prayers in order to show appropriate respect to God. These pronouns were part of the informal and intimate register, but they were preserved in the conservatism of religious discourse after falling out of use in other discourse, endowing them with a sense of reverence and respect, which is how Church leaders now instruct they should be used. Dallin H. Oaks, “The Language of Prayer,” Ensign, May 1993, 16–17. Institutionally, as with use of the KJV, the incidental has become prescriptive. For a larger discussion, see Roger Terry, “What Shall We Do with Thou? Modern Mormonism’s Unruly Usage of Archaic English Pronouns,” Dialogue 47, no. 2 (2014): 1–35.

[40] Ezra Taft Benson, Gordon B. Hinckley, and Thomas S. Monson, “First Presidency Statement on the King James Version of the Bible,” Ensign, August 1992, 80.

[41] “Ministering Principles: Reach Out in Compassion,” Ensign, July 2018, 6–8.

[42] The full passage in context reads “And of some have compassion, making a difference: and others save with fear, pulling them out of the fire; hating even the garment spotted by the flesh.”

[43] Compare Leviticus 11:46–57: “This is the law of the beasts, and of the fowl, and of every living creature that moveth in the waters, and of every creature that creepeth upon the earth: to make a difference between the unclean and the clean, and between the beast that may be eaten and the beast that may not be eaten” (emphasis added).

[44] The New Testament of the KJV is broadly based on the Textus Receptus (“Received Text”) manuscript family, which begins with Desiderius Erasmus’s first edition, published in 1516. For that edition, Erasmus had access to only a handful of New Testament manuscripts of the Byzantine type, dating to the twelfth century and later, so the Textus Receptus represents a fairly late witness to the New Testament (subsequent editions added an eleventh-century manuscript). The New Testament of the 1769 KJV (edited by Benjamin Blayney at Oxford) appears to have been revised based on a 1550 edition of the Textus Receptus, edited by Robert Estienne (also known as Robertus Stephanus). Blayney seems to have assumed that the original KJV translators relied on that edition, so he altered a number of passages to align with it, but they had actually used the 1598 edition of Theodore Beza. For the history of these manuscripts, see Bruce Metzger and Bart D. Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 4th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 137–64. Interestingly enough, Blayney’s edition perpetuated some errors from the 1611 KJV (such as “strain at a gnat” in Matthew 23:24, where it should read “strain out a gnat”) but also introduced some printing errors of its own that remain even today in our Latter-day Saint editions. Joshua 19:2, for instance, reads, “They had in their inheritance Beer-sheba, or Sheba, and Moladah.” This reads “Sheba” appositionally but, according to the Hebrew, it is just another city on the list: “Beer-sheba, and Sheba, and Moladah.” In Judges 11:19, the Hebrew reads “unto my place,” but Blayney’s text incorrectly printed “into my place.”

[45] This position is not without problems, though. See Peter Spitaler, “Διακρίνεσθαι in Mt 21:21, Mk 11:23, Acts 10:20, Rom. 4:20, 14:23, Jas. 1:6, and Jude 22—the ‘Semantic Shift’ That Went Unnoticed by Patristic Authors,” Novum Testamentum 49, no. 1 (2007): 1–39.

[46] Wayment renders this “have mercy on those who separate themselves,” which avoids the more common contemporary reading without siding entirely with Tyndale’s “have compassion on some/

[47] The Spanish is representative: . . . con “compasión, marcando una diferencia,” según la versión en inglés de Judas 1:22 (“. . . with ‘compassion, making a difference,’ according to the English version of Jude 1:22”). Without guidance from headquarters, a variety of solutions were found. The German translator translated the English literally, but removed the quotation marks and simply referred the reader to Jude 1:22: . . . mit Erbarmen (siehe Judas 1:22) (“. . . with compassion [see Jude 1:22]”). The Bislama translator similarly directed the reader to “see Jude 1:22,” but also bracketed off the differences from their preferred Bible translation: “[wetem lav] mo sore, [we i mekem jenis long laef]” (luk long Jud 1:22) (“‘[with com]passion, [which changes one’s life]’ [see Jude 1:22]”). The Indonesian translator simply included the passage unrevised from their preferred translation, which refers to “those who doubt”: . . . dengan “belas kasihan kepada mereka yang ragu-ragu” (Yudas 1:22) (“. . . with ‘mercy on those who doubt’ [Jude 1:22]”). The Greek translator directly quoted their preferred translation, which accurately reflects the intended meaning of the KJV: «Ελεείτε, κάνοντας διάκριση» (Ιούδα 1:22) (“Eleeite, kanontas diakrisē” [Iouda 1:22], “‘have compassion, exercising discernment’ [Jude 1:33]”).

[48] President Clark refers to “the injuries the Extreme Textualists have inflicted upon the people” by their “eliminations.” Clark, Why the King James Bible?, 119.

[49] On this phenomenon, see Metzger and Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament, 258–59, but see also Lincoln H. Blumell, “A Text-Critical Comparison of the King James New Testament with Certain Modern Translations,” Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 3 (2011): 67–126.

[50] The Riveduta also renders Job 19:26 in agreement with the German Einheitsübersetzung.

[51] Note that Elder Bruce R. McConkie called the notion that an angel came down and troubled the waters “pure superstition,” continuing that, “If we had the account as John originally wrote it, it would probably contain an explanation that the part supposedly played by an angel was merely a superstitious legend.” Doctrinal New Testament Commentary, vol. 1, The Gospels (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1973), 188. Elder McConkie thus acknowledged the potential for textual corruption but did not consider the possibility that the verse is an interpolation.

[52] The phrase “critical text” is used to refer to manuscripts of the New Testament published since the mid-nineteenth century that are based on more recently discovered manuscripts and more disciplined text-critical approaches.

[53] See George Wesley Buchanan and Charles Wolfe, “The ‘Second-First Sabbath’ (Luke 6:1),” Journal of Biblical Literature 97, no. 2 (1978): 259–62. Wayment translates according to the critical text, but his footnote states, “Some manuscripts read on the second Sabbath after the first.” I am unaware of any manuscripts that contain such a variant, but the note may just be a way to simply describe the more complex textual situation underlying the KJV’s rendering.

[54] The Latter-day Saint edition of the Bible in Spanish sought to make sense of the Textus Receptus as it stood, adding a footnote that suggests the “second sabbath after the first” must refer to the second sabbath after Easter.

[55] In Brazil, the comment was made that the Portuguese rendering of Daniel 3:25b affected our understanding of an event that is depicted in paintings hanging in meetinghouses all over the world. In that verse, the KJV reads, “and the form of the fourth is like the Son of God,” while the Portuguese edition has, e o aspecto do quarto é semelhante ao filho dos deuses, “and the form of the fourth is like a son of the gods.” The Portuguese is a more accurate rendering of the Aramaic, although out of an abundance of caution, a footnote was added providing an alternative rendering that aligned with the KJV.