The Book of Mormon in American Missions at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

John C. Thomas

John C. Thomas, "The Book of Mormon in American Missions at the Turn of the Twentieth Century," Religious Educator 19, no. 1 (2018): 29–57.

John C. Thomas (thomasj@byui.edu) is a professor of religious education at Brigham Young University–Idaho.

German Ellsworth intensified his call to share the Book of Mormon. "We felt very much impressed to have the Elders push the sale of Books of Mormon, because we find where-ever that book has been placed it has worked marvelous changes in the hearts of the people."

German Ellsworth intensified his call to share the Book of Mormon. "We felt very much impressed to have the Elders push the sale of Books of Mormon, because we find where-ever that book has been placed it has worked marvelous changes in the hearts of the people."

Historians describe the opening decades of the twentieth century as a challenging time of transition for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Manifesto on plural marriage in 1890 and the successful bid for Utah’s statehood in 1896 pointed toward rapprochement with American culture. But in an era of potential assimilation, tensions lingered as Mormons labored to “translate the things America demanded of them into the language and imperatives of their own faith.” Thomas G. Alexander observed that ongoing controversy in the era prompted Church leaders to search for “a new paradigm that would save essential characteristics of their religious tradition, provide sufficient political stability to preserve the interests of the church, and allow them to live in peace with other Americans.”[1]

Meanwhile, the imperative to share the gospel remained intact, but missionary work was “extremely difficult” in the first decades of the century. One reason, Kathleen Flake observed, was that the “Manifesto had not changed the world’s opinion of Mormonism,” and missionaries faced considerable hostility, scorn, and suspicion. For many, the label “‘Mormon’ retained its extremely pejorative connotation,” even symbolizing “what America was not and should not be.” When Joseph F. Smith became Church President in 1901, he worried out loud about the multitudes of “innocent people” whose minds were “darkened by . . . slanderous reports.” The opening years of his tenure probably worsened the situation, as sectarian rivals, muckraking journalists, and politicians revived doubts about the Church’s place in American society. Few people seemed willing to hear the Restoration message, and if “it could not make itself heard, the church had no reason for being.”[2]

How would the Church navigate such straits? It might pursue “national respectability” by forging a new Mormon image that centered on happy families, loyal citizens, and industrious workers. Richard Bushman saw evidence for that approach: “Rather than emphasizing doctrine, the church drew attention to Mormon culture and society.” Kathleen Flake perceived a different course. After his own discomfiting experience at Senate hearings about Reed Smoot’s fitness for federal office, President Smith came to see the centennial celebration in 1905 of Joseph Smith’s birth as an opportune time to reorient the Church’s relationship with critics and potential investigators. He and others chose to emphasize, as Flake described it, Joseph’s Smith’s “first revelation” instead of his “last.” By highlighting the earliest visions and blessings of the Restoration, Church leaders advanced a “nonnegotiable core” of doctrine: “restoration of Christ’s church from apostasy, a base of continuing revelation from heaven, and an assertion of Joseph Smith’s revelatory power and divine authority bestowed to those who followed.”[3]

What role did the Book of Mormon play as the Church tried to make itself heard? Neither Alexander, Bushman, nor Flake engaged that question, though one would expect the book to play a conspicuous role in Flake’s “nonnegotiable core.” Noel B. Reynolds, however, suggested a scenario closer to Bushman’s view of the era: “Any small gains . . . in Book of Mormon usage during the late pioneer period in Utah were probably set aside during the early years of the twentieth century, when the Church was working . . . to become more a part of American life than . . . in its earlier period of geographical isolation from and political conflict with mainstream American culture.”[4]

Reynolds recognized variety across missions but highlighted “two general approaches” in the early years of the century. One approach, attributed to Ben E. Rich, “promoted a Mormon slant on religious questions while only briefly mentioning the Book of Mormon,” relying instead on the Bible to reason “against standard Protestant views.” Another, personified by German E. Ellsworth, “used the book endlessly as a primary tool in missionary work.” Reynolds acknowledged Ellsworth’s foresight and cooperation from other mission presidents to publish the book in “large quantities” but concluded that Ellsworth influenced practice little beyond the Northern States Mission.[5]

A closer look at mission practice suggests a different conclusion. Significant efforts to raise the Book of Mormon’s profile in missionary work began even before Ellsworth’s ambitious plans took shape. These initiatives emerged in the field instead of at Church headquarters, motivated by local inspiration rather than prophetic mandate. Presiding councils supported innovation, but, typically, they did so after persuasive appeals from mission leaders, who relied on collaboration to compensate for scarce resources.

The structure of the Church’s missionary system aided that process. In 1904 only seven large missions covered all of the United States and Canada, and another encompassed Mexico.[6] Instead of a three-year tenure, most mission presidents spent much longer in the field, where they supervised missionaries and local congregations; Rich and Ellsworth both served fifteen years. During Ellsworth’s service from 1904 to 1919, no North American mission had more than two presidents. (See table 1 for an overview of the situation from 1898 to 1919.) [7] Joseph F. Smith referred to relatively young mission leaders as his “boys” and left some at their stations for much of his term as Church President.[8]

Church leaders provided comparatively modest direction and financial support to the missions. This allowed mission presidents to innovate, even as it obliged them to cooperate to bring ambitious plans to fruition. Mission presidents corresponded about their plans and gathered regularly for the Church’s general conference in April and October. There they consulted with peers as well as leaders. They also spoke in conference sessions, publicizing their plans for the Book of Mormon in their work. With small numbers and long tenures to build relationships, along with regular occasions to confer and persuade, innovations could diffuse across the continent. During these years, the missions collaborated to publish multiple editions of the Book of Mormon and a multimission periodical far from Salt Lake City. Ellsworth’s initiatives look even more remarkable upon closer inspection, but other leaders, including Rich, took significant steps to reintroduce a skeptical nation to Mormonism’s namesake scripture.[9]

Early Steps in Jackson County, Missouri

The first significant Book of Mormon initiative emerged in Jackson County, Missouri, as the century dawned. President James G. Duffin “began the process of decentralizing U.S. mission publishing” and encouraged other mission presidents to step up efforts to distribute the Book of Mormon. In the fall of 1899, Duffin left his home in Toquerville, Utah, to serve in the Southwestern States Mission, headquartered in Saint John, Kansas. Assigned to South Texas, he spoke of the Book of Mormon soon after his arrival. Five months into the mission, Duffin learned by letter that he would succeed William T. Jack as president. In October 1900 he went to Utah for general conference, where mission leaders and General Authorities discussed options to reduce printing costs for missionary tracts and books. By year’s end he moved the mission home to Kansas City, Missouri, and negotiated contracts there with printers to supply him tracts and books, including ten thousand copies of the Book of Mormon.[10]

With approval of the First Presidency, Duffin entered a contract with Burd & Fletcher printers of Kansas City in November 1901. They would produce ten thousand copies of the Book of Mormon for $2,200 (635 pages each). Of this fee, $1,200 would be supplied by the elders of the mission, with the balance supplied from Church headquarters. Duffin described the “happy Kansas City day” in February 1902 when he began reviewing proofs. Sisters Amelia Carling and Sarah Giles (his only female missionaries) assisted him in proofreading, which continued for most of February and March.[11]

When he went to general conference in April 1902, Duffin found Church leaders pleased at the mission’s publication efforts. They called on him to speak at the Sunday morning session in the Tabernacle, where he told of the initiative and praised his missionaries for bearing half the expense of the venture. “Your sons have been led,” he said (omitting mention of the proofreading sisters), “to contribute of their means to that work, knowing that . . . God would bless them.” He emphasized that missionaries should study “the revelations of God given today” and teach “the people that word of God in its purity, to let [them] know that God is doing a work today, and not be forever dwelling on the past centuries.” Six months later he spoke again in conference, reporting that since May the missionaries had distributed “nearly seven thousand copies” of the Book of Mormon “to various missions and throughout the country.” The book now went “out by the thousands where formerly it was distributed by the hundreds,” in part because it was “down to a price that can be reached by the people.”[12]

Joseph Robinson of the California Mission and Joseph McRae of the Colorado Mission collaborated with Duffin in some of his Kansas City printing contracts. These pioneering efforts in the field reverberated in Utah, even as they paved the way for further initiatives in the missions.[13] Soon other mission presidents acted in concert to spread the word in print: by supporting Ellsworth’s Chicago editions of the Book of Mormon; by distributing a multimission magazine, Liahona, the Elders’ Journal; and by incorporating Zion’s Printing and Publishing Company, which after 1915 printed most missionary materials from its plant in Independence.[14]

German Ellsworth’s Remarkable Initiatives

In his memoirs, German Ellsworth said he first learned the value of the Book of Mormon as a boy in Utah when his uncle Amasa Potter told a Sunday School class that they would “never want for words” if they taught from it. In California on his first mission, from 1896 to 1898, Ellsworth carried copies with him “for sale and loaning purposes.”[15] Soon after his return, he married Mary Rachel Smith, and after a few years together in Riverton and Lehi, Utah, he was called back into the mission field.[16]

Sent to the Northern States Mission in 1903, he worked in the office in Chicago as mission secretary. Examining the stock of literature one day, he found no copies of the Book of Mormon on hand for 175 elders and sisters, so he ordered three dozen copies from Deseret News Press for thirty-seven and a half cents each, though President Asahel Woodruff said his order would last “the next six months.” Soon after receiving the call (by wire) to succeed Woodruff in the summer of 1904, Ellsworth asked Joseph F. Smith for permission to contract with Chicago printer Henry C. Etten & Co. for ten thousand copies of the book. As Ellsworth later recalled, President Smith expressed reservations: “You are only a boy, and I am afraid you will overdo it.” But the young president persistently advocated the book’s inherent “value . . . as a missionary” until he received the prophet’s blessing. [17]

The first “Chicago edition” of the Book of Mormon appeared by August 1905. Ellsworth said that “missions in the United States combined” to finance the contract, and impressions still exist for Duffin’s Central States Mission, Rich’s Southern States Mission, and the Bureau of Information in Salt Lake City. Other missions may have participated as well. The Northern States Mission retained about one-third of the books. This edition cost twenty-seven cents per copy, “including the making of plates,” and the cost would drop in subsequent Chicago printings.[18]

By the spring of 1906, Ellsworth intensified his call to share the Book of Mormon. “During the early part of May we felt very much impressed to have the Elders push the sale of Books of Mormon, because we find where-ever that book has been placed it has worked marvelous changes in the hearts of the people.” In June, his missionaries sold 1,232 copies of the book, twice the number he had anticipated.[19]

In letters to mission leaders, Ellsworth reviewed their efforts and explained his thinking. Missionaries in the Wisconsin conference sold 461 copies in June 1906, while eight elders in Manitoba sold 305 copies—an average of over 38 per missionary. Ellsworth told a conference president in Indiana that once the printer completed another run of 10,000 copies in August, he “hope[d] . . . to have the weakest Elder in this mission sell at least one Book of Mormon every week while those favored of the Lord reach many times that number.”[20]

Where missionaries distributed the book most actively, he wrote, “It is marvelous to notice the change in feeling.” Containing “the fullness of the everlasting Gospel,” the book’s “spirit . . . comes over the reader [and] cannot be resisted.” As he told a conference president in Michigan, “It is the first missionary book in this generation. It is the book used by the first Elders. It is the book for us to use, according to inspiration received.”[21]

When Ellsworth attended general conference in October 1906, Church leaders evidently commended his missionaries’ work. “The Authorities were especially pleased with the Book of Mormon sales,” wrote a member of his office staff. “They think we have struck the key note of success when we push this Divine Book.” The secretary expected that “other missions will be asked to sell Books of Mormon” and that the Northern States “must remain where [they] are, that is leaders.”[22]

Speaking at an overflow session of general conference, Ellsworth described recent efforts and the motives behind them. He had been “very much impressed” to distribute the book more widely, feeling “very keenly” the responsibility to share it as a second witness of the Savior. The mission had “endeavored with all the means that God has given us to put [it] in the hands of the people, trusting that the Spirit of the Lord may move upon them . . . [to] read and learn wisdom.” By the end of June, they ran out of copies, prompting his order for ten thousand more by August. Promoting the Book of Mormon had not detracted from any other aspect of the mission’s work, he said, but brought “additional testimony” through God’s spirit to “the hearts of the Elders and the people.”[23]

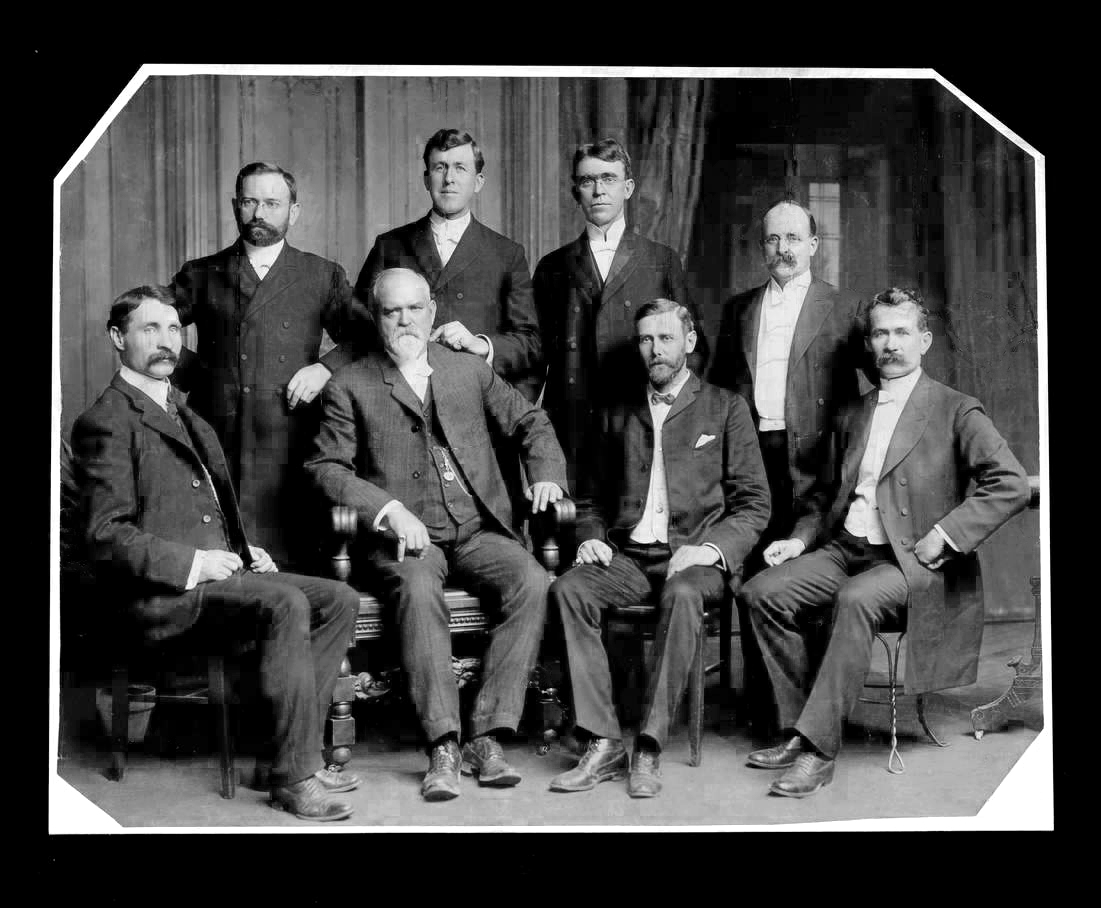

US mission presidents, ca. 1904. Front row, left to right: John G. McQuarrie (Eastern States Mission), Nephi Pratt (Northwestern States Mission), Ben E. Rich (Southern States Mission), James C. Duffin (Central States Mission). Back row, left to right: Asahel H. Woodruff (Northern States Mission), Joseph E. Robinson (California Mission), Joseph A. McRae (Colorado Mission), Benjamin Goddard (Temple Block Mission).

US mission presidents, ca. 1904. Front row, left to right: John G. McQuarrie (Eastern States Mission), Nephi Pratt (Northwestern States Mission), Ben E. Rich (Southern States Mission), James C. Duffin (Central States Mission). Back row, left to right: Asahel H. Woodruff (Northern States Mission), Joseph E. Robinson (California Mission), Joseph A. McRae (Colorado Mission), Benjamin Goddard (Temple Block Mission).

Throughout his tenure, Ellsworth remembered those early intimations after the call to preside. When his service ended in 1919, he spoke again about a strong “impression . . . that the Book of Mormon had been given of the Lord as a witness to this generation and that if we would remember it,” the Church would “come out from under the condemnation . . . that . . . rested upon Zion” (a clear allusion to D&C 84:54–58). As he said in April 1908, the Lord “chided [early elders] because they had neglected the things they had received,” especially the book which had been given to “this generation.” This idea spurred him to enter contracts to print ten thousand copies of the book in 1905 and ten or twelve thousand more in 1906. It may also have prompted his efforts to create a new periodical for North American missions (as discussed below). [24]

Renewed Urgency after Cumorah

In January 1907, Ellsworth wrote George Albert Smith of the Quorum of the Twelve, reflecting on the past year. Missionaries had been “diligent and faithful” and had made “a special effort” to bear testimony of the Book of Mormon. In 1906 they were “enabled to dispose of between five and six thousand copies,” along with some sixteen thousand copies of other works like “Cowley’s talks, Voice of Warnings, and Durants”—altogether “a very splendid record in the book line.”[25] But this was only a beginning.

Weeks later, Ellsworth wrote Joseph McRae of the Western States Mission that the Northern States had sold less than two thousand copies of the book in 1905 but six thousand in 1906. He hoped for eighteen thousand in 1907, based on two books per week per missionary, and “if we do not reach it we shall be the better for having made the trial.” He praised McRae’s “success” and thought he might distribute eight or even ten thousand books in his smaller mission that year. He offered to share freight expenses for the twenty-two-cent books and suggested purchase of James E. Talmage’s “lecture” on the Book of Mormon, excerpted from his Articles of Faith. Ellsworth’s office sent a copy of the pamphlet “with every Book of Mormon sold to the Elder.”[26]

In June 1907, George Albert Smith invited Ellsworth to join him on a journey to Palmyra, New York, and to other historic locations. This tour is best remembered for Elder Smith’s successful negotiations to purchase land on which the Joseph Smith farm had stood. Ellsworth walked the sites repeatedly during their stay. One morning at the Hill Cumorah, he had a revelatory experience so impressive that he chose to memorialize it on his gravestone more than half a century later. “I heard a voice, clear and distinct,” he recounted. The voice said, “Push the distribution of the record taken from this hill. It will help bring the world to Christ.”[27]

This experience spurred Ellsworth to negotiate printing twenty-five thousand more copies of the book. He sent postcards of Cumorah to all his missionaries with the message he had received, and his staff wrote that if the cards continued to stoke demand, they would need fifty thousand. By July 1907, Ellsworth had determined to place an unprecedented order of one hundred thousand books for 1908. George Edward Anderson wrote that he “expected to put out one hundred thousand copies of the Book of Mormon and then commence to baptize the people.” Such an effort required cooperation, and “all [US] missions participated equal[ly],” with impressions struck for specific missions across the continent. At a time when there were fewer than two thousand missionaries in all the world, this was an audacious move.[28] While recognizing this remarkable epiphany and its substantial effects, one should remember that Ellsworth had already launched significant initiatives based upon impressions in Chicago. The revelation at Cumorah simply renewed his urgency.

When Ellsworth addressed Eastern States missionaries in New York, Elder Smith asked him to say more about his mission’s use of the Book of Mormon. The Apostle then “endorsed our remarks and added what we have said many times here, that it [the Book of Mormon] was the first great Missionary in the Church” and that “it was a matter of considerable interest [to the First Presidency and Twelve], to know that the Book of Mormon had taken its place as a Missionary.” During Ellsworth’s absence, President McRae had repeatedly telegraphed the mission office for more copies, but nervous staff members had been reluctant to share from their dwindling stock. Upon his return, Ellsworth wrote to promise him 240 copies by fast freight, with more to come as soon as Etten & Co. finished printing. He also conveyed Elder Smith’s sense that increased distribution of the book would be “one of the greatest works that has ever been done in the Missionary Field.”[29]

Accentuating the Book of Mormon did not diminish distribution of other mission literature. At general conference in 1908, Ellsworth said that efforts to share it had “more than doubled the distribution of other books and tracts.” He thought the book simply “opened the door” for further discussion and inquiry. That said, he told missionaries that the book was “a seed that cannot be destroyed” and was “the thing [that is, the seed] itself, not a description of it.” He observed that “tracts rot in the gutter or make kindling for the housewife’s fire, but the Book of Mormon will always be preserved until it finds an honest heart that has been wrought upon by the Spirit of the Lord.” “Nothing was as good as the real thing,” he wrote another elder, “and it was his [Ellsworth’s] determination, as his record will show, to give the people this great testimony for Christ.”[30]

Sharing the book boosted missionaries’ confidence: “The Lord has been with them and has magnified them in their labors. They feel that in taking the Book of Mormon . . . they have something important enough to take to the biggest men of the nation.” He found it “remarkable” that a missionary could “open it any place, and the Spirit of the Lord, which accompanies the book, comes upon the people, and they are at once interested.” His words moved Elder Heber J. Grant of the Twelve, who closed a conference session by affirming the book’s “wonderful spirit” and its power as a missionary tool. Grant invited listeners to study Alma 29 and 36 if they wanted to see its “mark of divinity.”[31]

Ellsworth worked to help people open the book and open their minds. To prepare the way for a wave of missionary meetings and door-to-door contacts, he would send letters to prominent citizens of a town or city. One of these started by stating that “American people think for themselves.” Rather than hear only “one side of the question” on Mormonism, real Americans would “look for themselves.” Missionaries had made a “special sacrifice to place the Book of Mormon in the hands of every honest soul in our fair land.” Why would someone “stand on hearsay” when the “only rational thing [to do] . . . is read for yourself.” He wrote of a “highly civilized” people in ancient America and God’s “rational” revelation to them. Any “honest person” who read the book with a “prayerful heart” would know it had “come forth in this day to assist in spreading the beautiful doctrines of Jesus Christ.” A postscript suggested specific pages to read.[32]

To further facilitate sales of the book, Ellsworth (or his helpers) published a small pamphlet or “folder” to introduce the book. The title was direct: Wanted! One Hundred Thousand Men and Women to Read the American Volume of Scripture. The pamphlet included a description of the book, testimonials, and several quotations to illustrate “A Few of the Book of Mormon Truths.” It offered the book for $0.50 in cloth or $1.75 in Morocco leather.[33]

At general conference in October 1908, Ellsworth reported that his mission had dispensed twelve thousand copies of the book that year, a stark contrast to one hundred copies distributed just five years earlier. There were “calls for it on every hand,” by mail and in person. People who had received the book became friends (though not necessarily converts). The “best men in the community” welcomed missionaries into their homes. Some people told of sharing the book with their neighbors, who praised its “wonderful examples of faith in the Lord Jesus” and marveled that they had previously ignored it, thinking it was “peculiar to your people, and not for general distribution.”[34]

A later conference address suggested how missionaries might use the book in teaching. In April 1916 he observed that no other book contained “more beautiful stories of blessings following faith in God” or “clearer explanation of the plan of salvation.” He urged parents to teach their children the “beautiful and faith-promoting” stories of the book and its “wonderful doctrines of salvation.” His missionaries would point out “one or two good things” on the first visit and then continue to “turn down a few other corners of the leaves” till they had marked two dozen passages or more. He wondered how many members had marked “the gems” that would “bring comfort and consolation” and “inspire [them] to . . . proclaim the gospel” and “prepare” for coming responsibilities.[35]

A New Mission Magazine to “Magnify” the Book of Mormon

At the same time that his Book of Mormon efforts accelerated, Ellsworth pushed for a new multimission periodical. With other publishing demands, he felt that he could not “go alone,” and so he invited other mission presidents to a special meeting in Nauvoo, Illinois, in June 1906 to make plans. Not all could attend, but James Duffin and Ben Rich did, and “if we three can come to terms the battle is practically won.”[36]

Plans moved more slowly than Ellsworth may have liked. Mission leaders deliberated by letter and in person through November 1906, when Ellsworth wrote the First Presidency, admitting that he might be “over zealous” about the venture but that he appreciated their “confidence.” He also acknowledged that the periodical would require some financial assistance from Church headquarters before it became “self-sustaining.” After meeting with Presidents Joseph McRae and Samuel Bennion (Duffin’s successor) in Kansas City that month, Ellsworth wrote the First Presidency to report their estimate of expenses for the “missionary paper.” He thought they would need a subsidy beyond subscriptions for a few months but advocated the project’s value. “We anticipate that this paper will take the place of the tracts now being distributed by the various missions and instead of a dead issue it will come before the people as living matter and be more effective in warning this nation.”[37]

Ellsworth planned to publish the magazine in Chicago and recruited Benjamin Cummings as editor. He was surprised by the decision to base the periodical in Independence, Missouri, home of the Central States Mission, but “concede[d]” President Bennion’s “inspiration” in the matter. By the time the Liahona first appeared in April 1907, its advisory board included all US mission presidents except Ben E. Rich, whose Southern States periodical, the Elders’ Journal, had been growing in circulation for four years. Recognizing that the publications competed for subscribers, Rich soon proposed that his magazine move to Jackson County and become the voice of all American missions. When mission presidents gathered in Utah for general conference in April 1907, a committee of Church leaders chose to consolidate the two magazines under the roof and editorial staff of the Liahona. Rich was disappointed that “a new paper [should] swallow up his long-established magazine” and disliked the awkward new name, Liahona, the Elders’ Journal, but he joined the rest of the mission presidents on its board.[38]

From the start, a “chief purpose” of the Liahona was to “magnify” the Book of Mormon and “make [it] better known to the American people.” Its title was intended as a conversation starter, and each number featured an excerpt from the book (usually a chapter) “accompanied by explanatory comments.” Ellsworth corresponded with George Reynolds about the prospect of “publishing extracts from that valuable record” as early as November 1906. He said there were “chapters and paragraphs” in the book “that would fit exactly the life and condition today if properly introduced to the reader.” This idea grew into a regular feature for the first two years of the magazine.[39]

After Elder David Henry Fowler transferred from the Northern States Mission to help edit the consolidated magazine, he wrote “Ancient American Prophets,” sampling chapters through Alma 38 before his mission ended in the summer of 1909. Fowler’s remarks ranged from analytical to homiletic, and some were more timeless than others. But members and missionaries who read the column saw a model of how to learn and teach from the book, and investigators were given guided access to the scriptural text. An October 1907 editorial called “this weekly extract . . . one of the most valuable features of our magazine.” At its birth, the periodical had no more than twelve thousand subscribers, but twenty thousand copies were printed. Thus, missionaries regularly distributed thousands of copies of the magazine in lieu of tracts—and each contained a chapter of the Book of Mormon with accompanying comments.[40]

Liahona, the Elders’ Journal ran for thirty-eight years, and more remains to be learned about missionary work from studying its pages, including experiences with the Book of Mormon in the first half of the twentieth century. The magazine’s editorials, articles, correspondence, and reports open a window to the role the book played in the lives of missionaries, members, and even readers who had not joined the Church.[41] For the purposes of this article, it suffices to show how innovations spread as the mission presidents collaborated. Cooperation on the magazine reinforced other joint-publication efforts and paved the way for the incorporation of Zion’s Printing and Publishing Company, under the presidents’ direction. After 1915 the plant in Independence became the primary printer of missionary materials in North America and issued several editions of the Book of Mormon.[42]

Ben E. Rich and the Book of Mormon

Ben E. Rich became a mission president six years before German Ellsworth and died in the field six years before Ellsworth’s release. As we have seen, he collaborated on Ellsworth’s principal initiatives, even when it hurt a little (in the case of his magazine). But he has been portrayed as forging a different path for missionary work that sought to “mainstream” Mormonism in American society by downplaying the Book of Mormon. Is that an accurate portrait?

The son of an Apostle, Rich served a mission in Britain in the 1880s, edited a newspaper in Idaho, and became active in the Republican Party in the 1890s, forging friendships with business and political elites. Rich went to preside over the Southern States Mission in 1898 and saw the tumult that accompanied B. H. Roberts’s failed effort to secure a seat in the House of Representatives and Reed Smoot’s tortuous but successful quest to retain his place in the Senate. In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt went out of his way to acknowledge Rich in Chattanooga, Tennessee, hoping that the gesture would buttress his standing in the area; some believed their friendship helped save Senator Smoot.[43] If soft-pedaling the Book of Mormon would forge better bonds with neighbors, Rich was well situated to sense it during ten years in the Southern States and five more in the Eastern States.

Paul Gutjahr surveyed Noel Reynolds’s research and concluded that Rich’s time in the Bible Belt conditioned him to engage “non-Mormons with a sacred text they knew before moving on to a sacred text they did not,” using Bible passages to challenge “standard Protestant views of suspended inspiration and a closed canon.” Gutjahr believed that his approach set the standard for other missions’ “initial conversations with converts” and even influenced “missionary training guides until the 1960s.”[44]

This version of the story goes too far and relies too heavily on a single document—Mr. Durant of Salt Lake City, That ‘Mormon’—which Rich published in 1893, before he became a mission president.[45] Mr. Durant narrated at length (over three hundred pages in some editions) a series of discussions on matters of faith among a group of people at a guesthouse in Tennessee. The hero was an affable and articulate Mormon. Though set in the South, the booklet evidently sprang from experiences on Rich’s first mission in Britain. Rich’s son recalled that the depression of 1893 dampened sales enough that Rich sold the copyright to George Q. Cannon & Sons, eliminating his stake in the hundreds of thousands of copies missionaries sold in the succeeding decades, including the editions his mission published. When Rich visited Utah in 1906 or 1907, he was burdened by debts. Joseph F. Smith wrote a check to settle them, apparently assuring Rich that royalties from the work justified such intervention.[46]

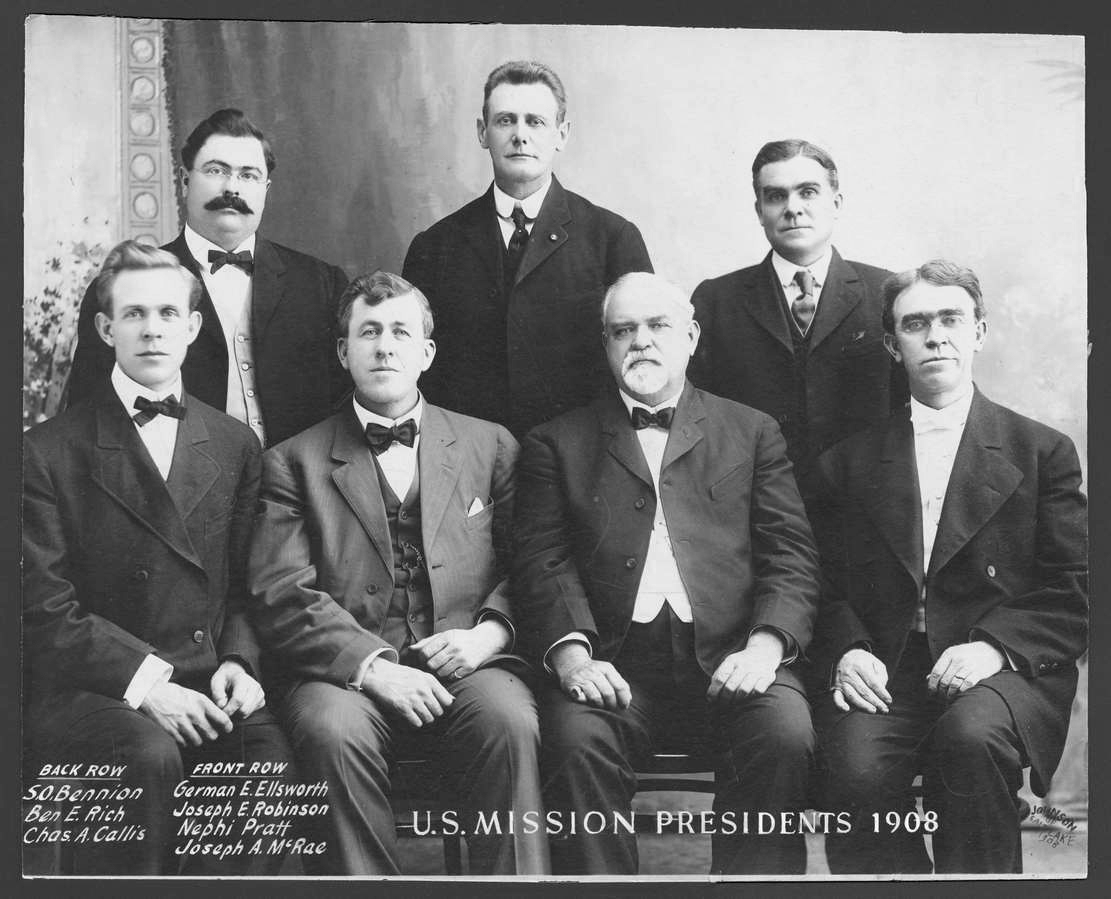

US mission presidents, ca. October 1908. Back row, left to right: Samuel O. Bennion (Central States Mission), Ben E. Rich (Southern States Mission), Charles A. Callis (Southern States Mission), German E. Ellsworth (Northern States Mission). Front row, left to right: Joseph E. Robinson (California Mission), Nephi Pratt (Northwestern States Mission), Joseph A. McRae (Colorado Mission).

US mission presidents, ca. October 1908. Back row, left to right: Samuel O. Bennion (Central States Mission), Ben E. Rich (Southern States Mission), Charles A. Callis (Southern States Mission), German E. Ellsworth (Northern States Mission). Front row, left to right: Joseph E. Robinson (California Mission), Nephi Pratt (Northwestern States Mission), Joseph A. McRae (Colorado Mission).

In 1899, Rich condensed Mr. Durant into A Friendly Discussion on Religious Subjects, and the thirty-page pamphlet was widely used across the missions. Both the book and the pamphlet relied on the Bible to build a case for Mormon claims, which is the basis for Gutjahr’s conclusion. Although it is true that Rich never published a work that expounded Book of Mormon texts to teach “the fullness of the gospel” (see D&C 42:12), it would be a mistake to infer that Mr. Durant or A Friendly Discussion displaced the Book of Mormon in the Southern States.[47]

Rich developed a diverse portfolio of print media to spread the word, including two mission periodicals, and he responded favorably when other mission presidents launched efforts to increase distribution of the Book of Mormon. Events early and late in his service prompted him to advocate its importance to the work, in the field and in his reports to members at general conference. In fact, even before innovators like James Duffin or German Ellsworth commenced their service, Ben Rich himself urged greater use of the Book of Mormon.

The same year he published A Friendly Discussion, Rich described plans for the Book of Mormon in his mission. An 1899 editorial in the Southern Star, “Pushing the Book of Mormon,” counseled missionaries to carry a copy to share in any setting. Rich rebutted charges that elders tried to hide the book from investigators. Instead, he urged them to “adopt every feasible means to show the world we want the people to read the Book of Mormon and the books and literature we publish.”[48]

In 1903, Rich and his conference presidents agreed that elders should “specially endeavor to sell as many copies of the Book of Mormon as possible and ought never to be without one for sale.” This rule was printed in the mission’s handbook in 1906 and remained a standard thereafter. In 1904, Rich adjusted the prescribed program of scripture study for his missionaries. An article in the Elders’ Journal (his second periodical) observed that elders already devoted more than an hour daily “to the study of the Bible alone.” They should continue Bible study but “also . . . devote as much time as possible” to studying other standard works of the Church. “[We] desire especially that the Elders shall set apart one hour each day for a close study of the Book of Mormon,” eventually adding other latter-day scripture to the mix. Missionaries should “quote from these books as well as the Bible,” specifying the source to inspire listeners to “read the books for themselves.” Those who did so would grow in testimony and find themselves “in closer touch with the comforter.”[49]

Clearly, Rich taught missionaries to study and share the Book of Mormon. How did he and his missionaries use it? In March 1899, Rich went to Atlanta for a conference, where the Atlanta Constitution interviewed him at length about “Mormonism from a Mormon standpoint.” The Millennial Star republished the Constitution’s report of the interview within months, and later that year the mission published it as a pamphlet. Years later, Rich preserved the interview, along with A Friendly Discussion and many other pamphlets, in his two-volume Scrapbook of Mormon Literature.[50]

A 1904 version of the pamphlet advertised mission literature, including the Book of Mormon, a “remarkable” book containing a “sacred history of America’s ancient inhabitants” and the risen Christ’s teachings to them. It urged readers to proceed “prayerfully, and with a desire to know” its truth, quoting Moroni 10:4. The interview itself commenced with questions that elicited Rich’s comments on the book. Asked first about the name of the Church, Rich gave its proper title and traced the nickname to Mormon, an ancient American prophet who had assembled records translated by Joseph Smith. Asked about the “Mormon Bible,” he referred to the King James Version, explaining that the Book of Mormon was a distinct record of the Western Hemisphere but that the books “run together and harmonize, being inspired with the same spirit.”

When asked if additional scripture violated Revelation 22, Rich explained the passage’s proper application. What need was there for more revelation or churches? Rich replied that the multiplicity of churches indicated a problem, and new scripture was the solution. “Something more is needed,” he said, “to set mankind right on the doctrine of Christ and make the word of God plain to the common understanding.” Would the Book of Mormon “set these matters right and clear up all that is obscure in the Bible”? Rich affirmed that it cast valuable “light” on Bible passages and confirmed its witness of the “doctrines, ordinances, gifts and blessings” given to Israel. It was also “very much plainer” and more “definite” about matters vital to a reader’s “understanding of Christian truth.” Yet he added that Mormons “do not depend on any book for the gospel we preach or the order of the church.” Neither book, he said, was the source of Church doctrine or authority—which came “directly from heaven” by revelation to prophets.[51]

About twenty more questions and answers followed; despite his opening statements, Rich relied on Bible texts to substantiate his points (with one uncited quotation of the Doctrine and Covenants). On the one hand, Rich made a forceful case for the purpose and value of the book. On the other hand, he highlighted modern revelation as the central source of the Church’s message and authority, and neglected to model how Book of Mormon teachings improved understanding of the issues raised by the reporter, relying on Bible passages. Thus, the interview showed both Rich’s possibilities and limits as a Book of Mormon advocate.

In April 1900, his son Ben L. Rich, a twenty-year-old elder, gave a lecture on the Book of Mormon to the Ohio Liberal Society in Cincinnati. Subsequently published in the Elders’ Journal, his presentation probably derived in part from James E. Talmage’s 1899 pamphlet, The Book of Mormon: An Account of Its Origin, with Evidences of Its Genuineness and Authenticity. Elder Rich did little to exposit the contents of the book, hewing closer to its origin, significance, and plausibility. He concluded by praising the “simple, logical and harmonious” structure of the book and giving witness that “the spirit which permeates its pages feeds the soul. To read it is to be a better man, to feel purer and happier.” The book itself, he thought, served as “an argument able to satisfy its claims in its evidence of prophesy [sic] and consistency.” “Is it not reasonable?” he asked. “Does it not deserve careful and serious investigation?”[52]

Ben L. Rich recalled that some were not receptive to his message. When he concluded, several people challenged his assertions or raised skeptical questions or critiques. At that point his father, who had sat anonymous in the hall, asked permission to address the assembly. President Rich took the stand and rebutted the critics at some length. Only when he concluded did he reveal his identity, to the surprise of the moderator. We can only guess how he used the Book of Mormon in his extemporaneous remarks.[53]

Years later, near the end of his life, Rich engaged Rev. A. A. Bunner in a public debate in New York. For five nights, they made their case to affirm or contest the proposition that no prophets had been called since Christ and that the Bible “is sufficient to guide men and women to salvation from sin.” Bunner was first to treat the Book of Mormon, making a few critical comments on the second night. Not till night three did Rich address it, saying he prized the book for showing God’s justice in sending Christ to another “half” of the world to teach them the way to be saved. On night four, Bunner (somewhat cleverly) argued that the proposition was sustained, since Rich had used only Bible texts to make his points about the way to salvation. Did Rich recognize that his opponent had found a flaw in his tactics? He didn’t say. Instead, he pointed out the Church’s efforts to share the Book of Mormon worldwide as a record of the “everlasting Gospel” and a companion to the Bible. US missions had recently printed one hundred thousand English copies (for the second time). “What do we do with it if we do not use it?” Rich asked in exasperation. “Do we use it for kindling wood?”[54]

Rich’s remarks at general conference in Salt Lake City indicate substantial efforts to disseminate the book, even as they raise new questions. In April 1902, he estimated that his missionaries had distributed some 7,000 copies of the Book of Mormon during the past four years. (In that time they had shared 70,000 copies of Parley Pratt’s A Voice of Warning and 55,000 copies of Mr. Durant.)[55] Six years later, Rich reviewed a decade’s labor in the Southern States at general conference. He began by reporting that some 25,000 copies of the Book of Mormon had been “distributed among the people” during his tenure. Missionaries had also sold 150,000 copies of Mr. Durant, “a work upon the principles of the Gospel,” and a similar number of copies of Voice of Warning.[56]

After October 1903, the Southern States Mission published statistical reports in its magazine (acknowledging that “perhaps the greatest good often cannot be recorded on earthly paper”). The reports relied on a form in use for some years. Columns tracked numerous aspects of missionary work, such as visits, gospel conversations, and appointed meetings, as well as the dissemination of various print media. Separate columns tallied tracts, subscriptions, book sales, Book of Mormon sales, and “books otherwise distributed.”[57]

Book of Mormon sales varied widely across conferences and months and trailed other sales. In October 1903, for instance, 194 missionaries reported selling 60 copies of the scripture, but over 1,200 books. They “otherwise distributed” 864 books, leaving researchers to guess how many of those included loans or free gifts of the Book of Mormon. In October 1904 the ratios were similar: 177 missionaries sold 1,104 books that month but only 77 copies of the Book of Mormon; they “otherwise” shared 745 unspecified books. On more than one occasion, individual conferences reported zero sales of the book for a two-week period, and there is no clear pattern over time or across conferences, except for the high ratio of general book sales to scripture. Did these numbers and ratios match the aims Rich had stated previously?[58]

In the summer of 1906, the Elders’ Journal summarized eight years of work under Rich in figures. Missionaries had distributed 15,000 copies of the Book of Mormon, 40,000 copies of Cowley’s Talks on Doctrine, a similar number of hymnbooks, tens of thousands of copies of works by both Pratt brothers, and 120,000 copies of Mr. Durant, plus some 3,000,000 tracts. The mission itself published almost all literature except for the Book of Mormon. Elders’ Journal boasted nearly 5,000 subscribers, including most Mormon households in the South, missionaries in every mission worldwide, and a “vast number of friends.” Stokes estimated about 5,000 baptisms over eight years. [59]

When the mission magazine reported tallies for all of 1905 and 1906, it showed that the Book of Mormon lagged far behind other books in sales: 728 in 1905 (versus 11,977 others) and 749 in 1906 (versus 15,281 others). If those two years were typical, missionaries could not have sold some 25,000 copies of Nephite scripture in the decade up to 1908. But Rich had not claimed that many sales at conference; he used the word “distributed.” In 1905–6, over 12,000 books had been “otherwise distributed.” Did copies of the Book of Mormon compose some share of that total? If one-third of the 25,000 copies he mentioned in 1908 were sold, could the balance have been “otherwise distributed”? I conclude that he knew or guessed that missionaries shared the book in other ways. Contemporary reports are unavailable, but missionaries before and after loaned the book, selling it to readers who showed sufficient interest. Missionaries might well prefer loaning books to selling them or giving them away if a loan promised future contact.[60]

Questions linger about how his missionaries distributed the book, but it is clear that Rich continued to advocate its value as an instrument of personal testimony and spiritual growth. At general conference in April 1906, he told of a friend who questioned why God did not speak more often to his people. He asked if the man had read the Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, or Pearl of Great Price. When the friend said he had not, Rich replied, “If I was the Almighty I would not say another word to you until you made yourself acquainted with what I had already said.” In 1909 he affirmed that a testimony came by living gospel principles and by studying prayerfully the Book of Mormon.[61]

In April 1910, having presided over the Eastern States Mission for eighteen months, Rich again assessed the book’s place in his service. He quoted three hymns of the Restoration—two of which invoked Cumorah—and asked the Saints to consider their significance. “I wonder if we fully appreciate the responsibility that rests upon us,” he asked, “when we sing these hymns, and when our eyes rest upon this record, the Book of Mormon, which contains the fulness of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.” Having been “warned,” they were responsible to “warn their neighbors.” He said that “every individual should have an ambition to do something towards the spread of the information contained in this book, to [those] . . . in ignorance of the precious truths contained within [its] lids.” Rich then reviewed what had been done in the Southern States and said he looked forward to “even greater” efforts and results in his current assignment.[62]

That year, Liahona the Elders’ Journal published some statistical reports from its sponsoring missions. German Ellsworth’s Northern States missionaries reported selling 8,127 copies of the Book of Mormon; Charles Callis’s Southern States Mission reported 3,528 such sales. When it came to Rich’s Eastern States Mission, no such column existed. Instead, his chart reported 3,357 “standard church works distributed.” The Central States Mission reported similarly: 4,947 “standard Church works dist[ributed].” All these reports suggest substantial emphasis upon the Book of Mormon, but some ambiguity persists about the scale and methods of distribution.[63]

Ripples across the Missions, and the Response from Church Headquarters

We are fortunate to have the words of mission presidents (and other second-tier Church leaders) in the conference reports of the era. James Duffin discussed his plans for the Book of Mormon there in 1902 and concluded his service in 1906 by stating that only 200 books remained of 11,500 published during his tenure. His early words and deeds had set a precedent, and Ellsworth’s reports elicited occasional comment when other mission leaders spoke at conference. Some of Rich’s remarks probably emerged in response to Ellsworth’s energetic exposition. Here we briefly note what other mission presidents—and the First Presidency—said about their endeavors.[64]

In April 1907, Joseph McRae of the Western States Mission asked God to bless Ellsworth for the results of his visit to Chicago. He had been taken aback when Ellsworth asked that he purchase 1,500 copies of the book for his mission. He sent some on to Joseph Robinson in California and stored the rest. But soon “an inspiration came” to him: he sent six copies to each elder. When some asked what to do with them, he told them to decide but promised that six more would arrive soon. In the next four months they sold more copies (800) than they had in the previous two years. McRae wondered if the Saints understood the significance of the book and the “obligations” they had to distribute it. He had asked his missionary force to sell 5,000 copies of the book that year. “We do not feel like book agents,” he concluded, but messengers “filled with the power of the Lord” and “responsible to God” to deliver the book as “a message this generation.”[65]

In October 1907, John McQuarrie of the Eastern States Mission said that “the wave of interest” manifest among people in McRae’s and Ellsworth’s missions had yet to wash over his area. But he reported “marked improvement” in distributing the Book of Mormon, “this new witness for God that has come forth in this day . . . to be joined with the stick of Judah.” Joseph Robinson of California complained that the promise of eternal rewards was not enough to persuade most people in his field to read a book—“California is a good enough heaven for them.” But some elders had made strides in distributing the Book of Mormon, striving to “emulate the example of our more successful brethren” eastward. Nephi Pratt of the Northwestern States told of a woman who initially shrank from Mormonism’s reputation but took the book and found herself “all lit up” by its study, weeping with a friend as she read 3 Nephi. Such stories were “rare,” he said, but showed “the work of the elders and the influence of the Book of Mormon.” Six months later, Pratt noted Ellsworth’s move toward “better systematized” methods. He shared no statistics but attested, “There are more men reading the Book of Mormon in our field than ever before.”[66]

In the closing session of conference in October 1908, President Anthon H. Lund took note of the massive “latest edition” contracted in Chicago. He praised efforts to put the book in every home, reminding listeners that the 1830 edition predated any tracts and persuaded “strong men” to “accept the truth.” “There was a time,” he said, “when we thought” to introduce the message with “argumentative works,” but the book itself had “convincing power.” He hoped it would reach the homes of all people so that they could read its principles and make an informed choice. [67]

Lund’s remarks presaged further comment from the First Presidency in a year-end letter to the Church. They commended missionaries for sharing so many copies of the Book of Mormon and prayed the effort would continue, for the book had awakened “lively interest” in the Church’s message. Its “general use” among the missions “as a means of spreading . . . the gospel and . . . converting men” was “certain to be followed with gratifying results.” “This use of the Book of Mormon,” they observed, “is merely a return to conditions that prevailed in the early days of the Church,” when “some of the first and staunchest members were converted” as they read it.[68]

Conclusion

At a time when all of the United States and Canada fit into seven missions, it should not be surprising that energetic efforts by a few should ripple across a continent. Nor would such efforts elude the attention of presiding councils. In the opening decade of the twentieth century, innovations in Kansas City and Chicago elicited support from other mission presidents and from members of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve. Such developments tend to refute the assertion that this time of transition saw receding use of the Book of Mormon.

In a time of relative scarcity and substantial controversy over “Mormonism,” leaders like James G. Duffin and German E. Ellsworth chose to present “the thing itself” to guarded readers to testify of a living God. They found printers who could produce the book in volume at reduced expense, easing missionaries’ ability to buy and sell the book. They also found colleagues willing to collaborate on extensive publication efforts, including a continental mission periodical inspired by Book of Mormon imagery.

Like Duffin and Ellsworth, leaders such as Ben E. Rich, Joseph A. McRae, and Samuel O. Bennion trusted that the spirit of the book would cut its own way into the hearts of willing seekers. None surpassed Ellsworth’s devotion to sharing the Book of Mormon’s witness of Christ, but these and other men and women cooperated to raise the scripture’s national profile. As they did so, they advanced a “non-negotiable core” based on Joseph Smith’s first published revelation. Rather than downplay their faith’s distinctive scripture, they advocated its use, affirmed its wholesome spirit, and urged attention to its redemptive message. None seemed to see the book as an obstacle to engaging the world in upright and peaceable conversations.

Perhaps what they did was not so new, and perhaps all found that their reach exceeded their grasp. But what they did merits remembrance. And as they left their field of labor, Church leaders prepared a new edition of the Book of Mormon, designed for closer study and wider discussion, even as they anticipated centennial celebrations of its discovery, translation, and publication.[69] It may be that any era, decade, or year we inspect more closely will yield inspiring surprises about the “coming forth” of the book. What Elder Neal A. Maxwell said about the study of its text may also apply to the study of its use and meaning in Mormon history:

The Book of Mormon will be with us “as long as the earth shall stand.” We need all that time to explore it, . . . like a vast mansion with gardens, towers, courtyards, and wings. There are rooms yet to be entered, with flaming fireplaces waiting to warm us. The rooms glimpsed so far contain further furnishings and rich detail yet to be savored. . . . Yet we . . . sometimes behave like hurried tourists, scarcely venturing beyond the entry hall.[70]

Table 1: Turn-of-the-Century Missions and Leadership in the US and Canada

| Mission (headquarters) | President, Tenure, Age at Call (italics: serving in mission when called to preside) |

| Eastern States (Brooklyn) | Edward H. Snow, 1900–1901, 35 John G. McQuarrie, 1901–1908, 32 Benjamin E. Rich, 1908–1913, 53 Walter P. Monson, 1913–1919, 38 |

| Northern States (Chicago) | Louis A. Kelsch, 1896–1901, 40 Walter C. Lyman, 1901–1902, 38 Asahel Woodruff, 1902–1904, 39 German E. Ellsworth, 1904–1919, 32 |

| Southern States (Chattanooga)[71] | Benjamin E. Rich, 1898–1908, 43 Charles A. Callis, 1908–1933, 43 |

| Central States* (Kansas City, Independence) | James G. Duffin, 1900–1906, 40 Samuel O. Bennion, 1906–1933, 32 |

| Western States** (Denver) | John W. Taylor, 1896–1901, 38 Joseph A. McRae, 1901–1908, 36 John L. Herrick, 1908–1919, 40 |

| Northwestern States (Portland) | Franklin S. Bramwell, 1898–1902, 38 Nephi Pratt, 1902–1909, 56 Melvin J. Ballard, 1909–1919, 36 |

| California (San Francisco, Los Angeles) | Ephraim H. Nye, 1896–1901, 51 Joseph E. Robinson, 1901–1919, 34 |

*Southwestern States till 1904 ** Colorado till 1907

Based on information in Andrew Jenson, LDS Biographical Encyclopedia, vols. 1–4 (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jenson History Company, 1901–1936). See also Early Mormon Missionaries database, https://

Notes

[1] Matthew Bowman, The Mormon People: The Making of An American Faith (New York: Random House, 2012), 153; Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890–1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 14.

[2] Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 212–13; he thought that “missionaries began to experience a more favorable reception” around 1923–1930, aided by the “enlightened leadership” of mission presidents. Kathleen Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 4, 31, 33.

[3] Richard L. Bushman, Mormonism: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 103–4; Flake, Politics of American Religious Identity, 115–17, 128. Flake argues that this core message moved to center stage while “theocratic and familial kingdom-building” (which had been tied to social conflict in Missouri, Illinois, and Utah) receded from memory; 128–30.

[4] Alexander noticed little if any change in missionary methods in the opening decades. Mormonism In Transition, 15. Flake focused attention on uses of Joseph Smith’s First Vision, primarily within the Church. Politics of American Religious Identity, 118–24. Noel B. Reynolds, “The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon in the Twentieth Century,” BYU Studies 38, no. 2 (1999): 8–9.

[5] Reynolds, “Coming Forth,” 11–13. Reynolds devotes only a few pages to missionary uses of the book, so his treatment is necessarily abbreviated. Subsequent writers may have inferred more from his brief description of the era than he intended.

[6] The Bureau of Information on Temple Square in Salt Lake City could be considered an eighth American mission.

[7] See chapter 11 of Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, for useful background.

[8] German E. Ellsworth, “Sense and Nonsense Handed Down from Your Father’s Memoirs this Christmas Day of 1953,” 14, typescript, Church History Library (CHL), MS 3874.

[9] Note that Reynolds credited Ellsworth as the first twentieth-century speaker to “directly invoke Doctrine and Covenants 84:54–57 in urging people to remember the Book of Mormon,” at the April 1908 conference (long before Ezra Taft Benson cited the same reproof in a 1975 address). Reynolds, “Coming Forth,” 9.

[10] Hugh G. Stocks, “The Book of Mormon in English, 1870–1920: A Publishing History and Analytical Bibliography” (PhD dissertation, UCLA, 1986), 98. James G. Duffin, diary; vol. 1: 14–15 October 1899, 5 November 1899, 16 April 1900, 8 October 1900; vol. 2: 1 January 1901, 6 February 1901; Mormon Missionary Diaries, BYU Harold B. Lee Library Digital Collections. The contracts also included large runs of Ben Rich’s pamphlet A Friendly Discussion, two pamphlets by John Morgan (Duffin’s first mission president), and Parley P. Pratt’s Voice of Warning.

[11] Stocks, “The Book of Mormon in English,” 77, 98–99, 114–17. Stocks described the Kansas City edition using the Journal History, without reference to Duffin’s diaries. Compare Duffin, diary, vol. 2, 9 and 13 November 1901, 11 and 16 December 1901, 3 February 1902, 26 March 1902, 7 April 1902.

[12] James Duffin, in Conference Report, April 1902, 62; James Duffin, in Conference Report, October 1902, 15. Duffin’s diary indicates that fifty cents was standard for a cloth-bound missionary edition. I have not found the price missionaries paid for the books, nor is it possible to be sure how often they gave the book without charge. Duffin said it would be wrong to “speculate” on sales of the Book of Mormon, since Moroni had warned against “getting gain” from the record. He felt his missionaries had shown the right motive in donating “their means” to secure an economical printing. He recorded that 8,800 cloth bound copies were printed at a cost of twenty-two cents each, which suggests a comfortable margin on a fifty-cent book. (Another 1,200 copies were bound in various grades of leather.) But given the realities of mission life at the turn of the century, the $1,200 donated by his missionaries almost certainly amounted to a conscientious sacrifice rather than a financial investment. James Duffin, in Conference Report, October 1902, 15; Duffin, diary, vol. 2, 26 March 1902, 24 April 1902.

[13] When Deseret News Press offered a new edition in Utah that summer for fifty cents, it said the price was “half the lowest . . . for which it was ever published in this city.” The press attributed its lower price to improved “facilities for book work” and growing “interest” in Mormon literature. I wonder if competition with a cheaper missionary edition played a role. Stocks reported that the cost of ensuing mission editions dropped over time due to “repeated printings from the same plates.” He concluded that “official selling prices . . . were always set by the First Presidency, . . . [who] were motivated by other than purely economic concerns.” Stocks, “Book of Mormon in English,” 114–17.

[14] Duffin, diary, vol. 2, 3 February 1902, 24 April 1902. It appears that Robinson and McRae joined a contract for only tracts at this time. For more on the periodical and the corporation, see Arnold K. Garr, “Liahona the Elders’ Journal,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint History: Missouri, ed. Arnold K. Garr and Clark V. Johnson (Provo, UT: BYU Department of Church History and Doctrine, 1994), 173–80; and Stocks, “Book of Mormon in English,” 78–79.

[15] Ellsworth, “Sense and Nonsense,” 13.

[16] See Jaynann Morgan Payne, “Mary Smith Ellsworth: Example of Obedience,” Ensign, April 1973.

[17] German E. Ellsworth to David O. McKay and counselors, 28 October 1960, CHL, MS 3910. In another reminiscence, Ellsworth said Woodruff estimated that the books would last a year; see “Sense and Nonsense,”13. The letter indicates a price of twenty-seven and a half cents per book for the first order, which dropped as low as twelve and a half cents by the time he ordered 100,000 copies in 1908 or 1912.

[18] German Ellsworth, in Conference Report, October 1906, 86; Stocks, “The Book of Mormon in English,” 261–64; Ellsworth, “Sense and Nonsense,” 13.

[19] German Ellsworth to First Presidency, 13 July 1906, Northern States Mission letterpress copybooks, CHL, LR 6227 22.

[20] German Ellsworth to President Thomas H. Wilde, 10 July 1906, Northern States Mission letterpress copybooks.

[21] Ellsworth to Wilde, 10 July 1906; German Ellsworth to President Abraham Anderson, 10 July 1906, Northern States Mission letterpress copybooks.

[22] George N. Curtis to William Bywater, 12 October 1906, Northern States Mission letterpress copybooks (signature is obscured, but Curtis is the most likely sender.)

[23] German Ellsworth, in Conference Report, October 1906, 86–87. Ellsworth assured listeners that the effort had not brought a decline in baptisms or tithes (and had increased sales of other literature). How much difference his effort made in conversion or retention is difficult to say and beyond the scope of this essay. In 1912, Ellsworth called 175,000 copies distributed in recent years “good seed” sowed, with friends or friendlier feelings in “almost every home” that took one. In 1916 remarks that foreshadowed the teachings of President Ezra Taft Benson, he said, “I have found that people who are converted through reading the Book of Mormon are solid in the faith, their faith seems to be planted firmly upon the rock of revelation.” German Ellsworth, in Conference Report, April 1912, 91–92; Conference Report, April 1916, 80–81.

[24] German Ellsworth, in Conference Report, June 1919, 95; German Ellsworth, in Conference Report, April 1908, 41; Ellsworth, “Sense and Nonsense,” 13.

[25] German Ellsworth to George Albert Smith, 28 January 1907, Northern States Mission letterpress copybooks.

[26] Ellsworth to Joseph A. McRae, 16 March 1907, Northern States Mission letterpress copybooks. See more about Talmage’s writing below.

[27] Ellsworth, “Sense and Nonsense,” 14. Compare German Ellsworth, in Conference Report, June 1919, 95–96. The engraving on his marker is evocative. “Of all my works I leave this testimony: On June 6, 1907, at the Hill Cumorah in New York State, a voice declared to me, ‘Push the distribution of the record taken from this hill. It will help bring the world to Christ.’ German E. Ellsworth.” Smith’s diary indicates that he and Ellsworth were in Palmyra from 4 to 12 June 1907, before proceeding to other sites in New York and other eastern states, including Vermont and Virginia. In all, Ellsworth was gone from Chicago from 3 to 28 June. George A. Smith, diary, CHL, MS 8266.

[28] Ellsworth, “Sense and Nonsense,” 13; Ellsworth to McKay, 28 October 1960; G. N. Curtis to German Ellsworth, 11 June 1907, Northern States Mission letterpress copybooks; George Edward Anderson, diary, 12 July 1907, in Church History in Black and White: George Edward Anderson’s Photographic Mission to Latter-day Saint Historical Sites, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, T. Jeffery Cottle, and Ted D. Stoddard (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1995), 131. Stocks, “Book of Mormon in English,” 99–102. Stocks points out that other Chicago printings probably followed, including a large-type edition, and that the Chicago plates were used when the printing was transferred to Independence in 1915, with another 115,000 copies printed there in the next five years.

[29] German Ellsworth to President Fletcher B. Hammond, 1 July 1907; German Ellsworth to Joseph A. McRae, 1 July 1907, Northern States Mission letterpress copybooks.

[30] German Ellsworth, in Conference Report, April 1908, 41–43; German Ellsworth to President Fletcher B. Hammond, 12 July 1907; German Ellsworth to John Russon, 12 July 1907; German Ellsworth to President O. P. Olson, 12 July 1907, Northern States Mission letterpress copybooks.

[31] Heber J. Grant, in Conference Report, April 1908, 41–43, 57–59.

[32] Northern States Mission circular letter, 8 February 1908, CHL, LR 6227 32.

[33] Northern States Mission, Wanted! One Hundred Thousand Men and Women to Read the American Volume of Scripture (Chicago: n. p., 1907), CHL, M222 N878w. See also “Folder on the Book of Mormon,” Liahona, the Elders’ Journal, 4 July 1908, 60–62.

[34] German Ellsworth, in Conference Report, October 1908, 15, 18.

[35] German Ellsworth, in Conference Report, April 1916, 81–83; German Ellsworth, in Conference Report, October 1916, 134.

[36] German Ellsworth to Benjamin F. Cummings, May 1906, Northern States Mission letterpress copybooks; see also letters to John G. McQuarrie, 19 May 1906, Ben E. Rich, 29 May 1906, and Joseph A. McRae, 3 July 1906 in the same collection.

[37] German Ellsworth to First Presidency, 5 December 1906, Northern States Mission letterpress copybooks. Prospective editor Benjamin F. Cummings also participated.

[38]“Consolidation of the Liahona and the Elders’ Journal,” Liahona, 27 April 1907, 40–41; Garr, “Liahona the Elders Journal,” 175–80; Ellsworth, “Sense and Nonsense,” 11–12.

[39]“Our Name,” Liahona, April 1907, 9–10; “To Agents and Subscribers,” Liahona, the Elders’ Journal, 22 June 1907, 6–7; German Ellsworth to George Reynolds, 13 November 1906, Northern States Mission letterpress copybook.

[40]“Our Name,” Liahona, April 1907, 9–10; “To Agents and Subscribers,” Liahona, the Elders’ Journal, 22 June 1907, 6–7; “The New Paper,” Elders’ Journal, 1 April 1907, 445–46; “Read the Book of Mormon,” Liahona, the Elders’ Journal, 12 October 1907, 454–55; “Another Worker Gone,” Liahona, the Elders’ Journal, 24 July 1909, 77, identified Fowler as the series’ author. When Nephi Anderson replaced Cummings as editor, the series ceased.

[41] In addition to “Ancient American Prophets,” volume 6 published a series of “Testimonies” that includes frequent references to the book by members, and “Mission News” (variously titled) described various uses of the book by elders and sisters. As a tiny sample of relevant content, see “Book of Mormon Impressions,” 18 July 1908, 101–6; “A Sign of the Nativity: A Story from the Book of Mormon” (illustrated) and “A Fresh Significance of Christmas” (drawing on 3 Nephi 11–15), 25 December 1908, 657–60, 672–74; “Farewell,” 19 June 1909, 1272–73. For examples of the book’s impact on non-Mormons readers, see “Effect of the Tidings upon a Truth-Seeker,” 26 June 1909; and “The Book of Mormon as Good Reading,” 19 February 1910, 561–62.

[42] Stocks, “Book of Mormon in English,” 78–79, 188–80.

[43] Ben L. Rich, Ben E. Rich: An Appreciation by His Son (Salt Lake City, n.p., 1950), 23–28.

[44] Paul C. Gutjahr, The Book of Mormon: A Biography (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 100–101. “One can even detect in this period a de-emphasis on the Book of Mormon in certain missionary endeavors, activities where the book had stood as an unrivaled evangelistic tool since the Church’s founding. The Saints had long pointed to the book as a distinctive guide for their brand of Christianity and as a vivid sign that God still wished to be intimately involved with his creation. Such an emphasis receded in certain mission efforts in the opening decades of the twentieth century when Ben E. Rich, the president of the Southern States and Eastern States Missions, developed a program that emphasized the Bible over the Book of Mormon in early discussions with potential converts”; compare Reynolds, “Coming Forth,” 20–22. For a similar characterization dependent on Reynolds, see Casey Paul Griffiths, “The Book of Mormon among the Saints: Evolving Use of the Keystone Scripture,” in The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon: A Marvelous Work and a Wonder, ed. Dennis L. Largey, Andrew H. Hedges, John Hilton III, and Kerry Hull (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 209–11.

[45] Gutjahr, Book of Mormon, 100–101; Allison D. Clark, “FARMS Preliminary Report on the Development of Missionary Plans,” in Noel C. Reynolds, “Research on Book of Mormon Use,” MSS 2164 (L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University), folder 5. Folders 5, 7, and 8 of this collection are of most significance for my project. Just as Clark omitted some materials, her interviews with missionaries who served in the 1940s and 1950s relied on inaccurate hearsay about the work before their time.

[46] Rich, An Appreciation, 18–20. Those profits had funneled to the Church when it acquired Cannon’s firm.

[47] Kenneth L. Alford says it “became the most popular missionary pamphlet in the history of the Church.” “Ben E. Rich: Sharing the Gospel Creatively,” in Go Ye into All the World: The Growth and Development of Mormon Missionary Work, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Fred E. Woods (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 348.

[48]“Pushing the Book of Mormon,” Latter-day Saints Southern Star, 10 June 1899, 220.

[49]“Rules and Regulations,” Elders’ Journal, September 1903, 2; “The Elders’ Reference, Southern States Mission,” 19; “Study the Church Works,” Elders’ Journal, 1 September 1904, 9. Later that year the magazine announced publication of George Reynolds’ concordance of the book, recommended as a “valuable aid” to students; “A Complete Concordance,” 15 November 1904, 94. William A. Morton had earlier compiled Book of Mormon Ready References, For the Use of Students and Missionaries, of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (Geo. Q. Cannon & Sons, 1898). There is more to learn about the impact these study tools had on missionary work of the era.

[50] Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, 1 June, 337–42, 8 June, 353–57 and 15 June 1899, 369–75; “Mormon Bibliography” indicates it was published as a pamphlet by the Southern States mission in 1899, 1904 and 1909, with another edition by the Eastern States mission in 1910. See also Scrapbook of Mormon Literature, Vol. 2: Religious Tracts (Henry C. Etten Co. for Ben E. Rich, 1911), 103–121. Note the Chicago publisher.

[51]“Interview on Mormon Faith by Elder Ben E. Rich in Atlanta Constitution.” Pamphlet (CHL, M 230 R498g 1904 no. 2.) The opening questions and answers appear on pages 2–5 of the 32-page pamphlet.

[52]“The Book of Mormon,” Elders’ Journal, 1 November 1904, 65–70; 15 November 1904, 89–94; 1 December 1904, 108–110. Doubtless Elder Rich drew on other sources, including his own father. Excerpted from his Articles of Faith, Talmage’s pamphlet quoted many Book of Mormon passages omitted from Rich’s presentation. Ellsworth recommended distributing it with the book. Note that Articles of Faith may be the first systematic effort to integrate Nephite scripture into a discussion of central issues like fall and atonement, resurrection and millennium, scattering and gathering of Israel, first principles, and patterns of worship.

[53] Rich, An Appreciation, 15–16.

[54] The Bunner-Rich Debate (Henry C. Etten & Co. for Ben E. Rich, 1912), 53, 82, 87, 94, 106–108. The same Chicago printer published one hundred thousand copies of the Book of Mormon and proceedings of the debate.

[55] Conference Report, April 1902, 61.

[56] Conference Report, October 1908, 39. See the online version of A Mormon Bibliography, 1830–1930, for publication details on the book and the pamphlet.

[57]“Monthly Review,” Elders’ Journal, October 1903, 18. I don’t know where the form originated or how widely it was used, but Rich appears to be the first to publish aggregate statistics.

[58] Elders’ Journal, October 1903, 24; 15 Oct. 1904, 64; 1 Nov. 1904, 80 for the tables.

[59]“Brief Review of the Work Accomplished,” Elders Journal, 1 July 1906, 390. The article reports fifteen thousand copies of Voice of Warning, but sequence suggests that is a misprint of a higher figure.

[60]“Annual and Semi-Annual Report of the Mission for 1906,” Elders’ Journal, 15 January 1907, 191. Reports for February 1907 indicate Book of Mormon sales had risen to 115 that month. That would extrapolate to over 1300 for the year. See Elders’ Journal, 1 March 1907, 272; 15 March 1907, 288. It would help to know what role book charges played in a missionary’s living expenses. It would also be helpful to assess how comfortable missionaries felt about selling scripture in relation to other literature.

[61] Conference Report, April 1906, 44; April 1909, 47. Note that in October 1908 he twice mentioned that Nephi’s vision (1 Ne. 13–14) settled questions about Mormon loyalty to America and its constitutional system, since it showed God’s hand in its establishment; Conference Report, October 1908, 40, 102.

[62] In Conference Report, April 1910, 89–92.

[63] Liahona, the Elders’ Journal, 22 January 1910, 501; 5 February 1910, 535; 12 February 1910, 550; 5 March 1910, 599. The Central States mission conveyed the report without a table. Rich’s mission reported 2890 “Book of Mormon Lectures,” which merit further study, as do other features in this long-running periodical. Unfortunately, summary statistics appeared only irregularly across years and missions.

[64] In Conference Report, October 1902, 2; Conference Report, October 1906, 81.

[65] In Conference Report, April 1907, 84–86. As noted above, McRae’s interest grew during the year.

[66] In Conference Report, October 1907, 83, 69, 89–91; Conference Report, April 1908, 44–45.

[67] In Conference Report, October 1908, 116–17.

[68]“An Address to the Church by the First Presidency,” Liahona, the Elders’ Journal, 9 January 1909, 705–6.

[69] In light of the Church’s 1920 edition and centennials in 1923, 1927, and 1930, as well as other initiatives of the decade, I question the idea that “use of the Book of Mormon in missionary work reduced considerably” after Ellsworth’s release. Clark, “FARMS Preliminary Report,” 2.

[70] Neal A. Maxwell, Not My Will, but Thine (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1988), 33.

[71] The Southern States mission was briefly divided from July 1902 to May 1903, with Ephraim Nye presiding in the Southern States from Atlanta and Rich presiding in the new Middle States mission from Cincinnati. When Nye died in May 1903, the mission was consolidated and Rich returned mission headquarters to Chattanooga. See Andrew Jenson, Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Deseret News Publishing, 1941), 820–22; and Garr, “Liahona, the Elders’ Journal,” 176.