In the Footsteps of Peter and Paul: Modern Pioneers in Italy

Mauro Properzi

Mauro Properzi, "In the Footsteps of Peter and Paul: Modern Pioneers in Italy," Religious Educator 17, no. 2 (2016): 138–61.

Mauro Properzi (mauro_properzi@byu.edu) was an assistant professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this article was published.

St. Peter's Basilica at night.

St. Peter's Basilica at night.

Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary defines pioneer in two ways: (1) A person or group that originates or helps open up a new line of thought or activity, and (2) One of the first to settle in a territory.[1] The emphasis is different, but the two meanings share a common core: they both involve newness, either in thought or location, and movement, both with and toward this very newness. Since the “new” is often resisted and even opposed, the associated implication is that challenges, courage, and determination will often accompany the pursuit of the thought or location in question. These obstacles give rise to the need for strong communities that share the same pioneering goal and the need for wise leaders in these same communities, leaders who act as beacons through these challenging pursuits. In short, pioneering efforts can be exhilarating and highly rewarding, but they require constant exertion, endurance, and willful cooperation.

The first part of this definition fully applies to members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Italy, both in the past and in the present. Although more than 165 years have passed since the first Mormon missionary set foot on the Italian peninsula, Mormonism has not ceased to be new in the Bel Paese (Italian for beautiful country). The courage and determination which typically is required of religious minorities, especially demanding ones, continue to characterize the daily lives of Italian Mormons, as well as of European Saints more generally.[2] The second part of this definition, which involves the settling of a new territory, does not broadly apply to Italian Latter-day Saints, although early Waldensian converts clearly represent an exception. They came to Utah from the valleys of Piedmont in the nineteenth century and contributed to the settling of the Utah desert and its emerging pioneer communities. Most other Italian Mormons, however, are or have been pioneers in the other, broader sense, being called to follow in the footsteps of great teachers and leaders, to commit to something difficult though rewarding, and to encounter challenges and tensions that are stretching and uplifting at the same time.

The primary purpose of this essay is to sketch the pioneering trajectory of Mormonism in Italy in light of my personal history and the collective history of Italian Latter-day Saints. In so doing, I also aim to shed light on some aspects of Mormon missiology and ecclesiology that emerge from this story, and which I have experienced and observed directly. These reflections certainly deserve further analysis than what can be provided in the present context, but at least I can set some markers for further study and conversation. As a product of this history, I begin by highlighting a few key pioneer figures in my life, who, as it were, showed me the way after others had showed it to them. In so doing, I step out of historical order and start the journey by focusing on recent decades and on a specific location as a way to set a foundation for the broader ecclesiastical history that will follow. To be sure, mine is only one story among many, and it cannot be viewed as representative of all Italian Latter-day Saints. At the same time, it will likely be a useful illustration of what it means to be a Mormon in Italy.[3]

The Restored Gospel Comes to My Home

My parents joined the Church in December 1976. At the time, we lived in the town of Gorizia, a community of thirty thousand people, located on the border of Slovenia and less than a two-hour drive from Austria.[4] I was born in Gorizia and grew up there, but it is not the birthplace of my parents. My father was born and raised in Rome, and his parents had moved to the Italian capital from different parts of the country prior to his birth. Indeed, it is interesting to note that at least three generations in my family, including my four grandparents, my parents, and myself, are made up of individuals who were all born in different parts of the country. This is not common in Italy, and it underlies one of the classic dimensions of pioneering, new beginnings in new places.

My mother’s background is particularly interesting in this regard. At the young age of seven she experienced an actual exodus when she and her parents left her hometown of Pola (present-day Pula in Croatia). About three-hundred thousand Italians took part in this exodus from the peninsula of Istria, a corner of Italy that was occupied at the end of World War II by Yugoslav forces under the leadership of Tito. Locals had been given the “choice” to remain, with the likelihood of suffering under a communist regime, or to relocate beyond the newly created Italian borders, leaving their homes and lands behind. As a result, whole towns, homes, and lands were abandoned: a painful departure for most. The exodus was first by ship and then by train. My grandparents and mother, as well as a good number of Istriani (Italians from the Istria peninsula now absorbed into Yugoslavia), decided to settle in Gorizia, in the relative vicinity of the new borders, hoping for an eventual return to their homes in the unlikely event that preexistent borders would be reestablished. But that was not to be, and the new borders became permanent.[5]

Latter-day Saint missionaries came to Gorizia in 1975 and established a branch with a handful of members. I was only four when missionaries began to visit my home, and I can vaguely remember some of those early encounters. At the time, I obviously could not even remotely imagine how these visits would change my family and the rest of my life. My mother admits that when she first opened the door to the missionaries, she looked for an excuse to send them away. She told them to come back on a Sunday afternoon, when my father would be home, but the truth was that we were not usually home on Sunday afternoons—except for the Sunday when the missionaries returned. Several factors influenced the situation. My dad had been searching for answers to his existential questions and was not fully satisfied with his religious life. In addition, we had survived a major earthquake a few months earlier. All of this probably prepared my father’s heart for the message of the restored gospel. He was baptized within a month, and my mother followed suit a couple of weeks later—initially just to follow him in his decision, but soon acquiring her own testimony and love for the Church. They were “golden” investigators to be sure!

How common was this conversion experience for Italians who came into the Church in the mid-to late seventies? Every story is unique, and every person has his or her own timing, but being contacted and taught as a result of door-to-door approaches was very common at that time. Indeed, the seventies and early eighties still represent in many ways “the golden age” of missionary work in Italy, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Many joined the Church then, and as a result, two more missions were added to the two already in existence; moreover, several members and families who are pillars of the Church in Italy today joined during this time. Among these pillars is Renzo Tomasetti, who was baptized in Gorizia in 1975, the year before my parents. Renzo was my branch president when I was a teenager, and he still is the Gorizia branch president today; he has been serving in that calling for about twenty of the last twenty-five years. A man of great faith and a leader who has always cared for his little flock, Renzo’s untiring service typifies what often is required of members of the Church in Italy.

My parents have also served in many capacities in the Church, which is to say that they have been “active” in the full sense of the term. Our small branch, whose average Sunday attendance still hovers around forty, has benefited continuously from the members faith, example, and willingness to serve. These characteristics have also propelled me in my own commitments and spiritual decisions. In other words, when my father and mother accepted the message of two American missionaries—Elder Skousen from Arizona and Elder Horner from Utah—my parents became pioneers of the Church in Italy and pioneers for their son. These missionaries, in turn, acted as the connecting link between the Mormon pioneers of the West and the Mormon pioneers in Italy.

Indeed, when one chooses to become a Latter-day Saint in Italy, and when one is serious about the decision, the position and responsibility of being a pioneer cannot be shirked. Those who are not willing to take its charge tend to become inactive and lose their connection to the Church. Overall, Church membership is demanding, but it is even more so in those contexts where much needs to be done and the laborers are few, because on the opposite side, where there is strength in numbers, it seems that lukewarm commitments can be integrated and accommodated more easily.[6] Although the Italian Latter-day Saint community is now a little larger than it was in my teenage years, I know several Mormon youth who still experience what I experienced then: being the only Latter-day Saint of a certain age in a school and neighborhood, or for some, being the only Mormon young man or woman in a branch or city. This is also true of many other countries and even of parts of the United States. These are settings that function as natural laboratories for courage—settings which are certainly challenging, but also deeply refining.

Early Christianity: Peter and Paul as the First Pioneers

While these challenges are real, especially for youth who may feel lonely and even isolated, the great news is that many who have come before have shown the way forward. These models of courage and devotion in Italy can be found throughout the story and certainly at its beginning, almost two thousand years ago, in the first days of Christianity. Indeed, two of the most significant figures of the early Christian church, Peter and Paul, lived in Rome and found their deaths there as martyrs of the new faith. Paul’s Italian experience also included stops in Sicily, Calabria, and Naples on his final journey to the “Eternal City.”[7] Peter and Paul’s significance as Christian pioneers is recognized internationally by every Latter-day Saint, but Mormons in Italy, as well as other Italian Christians, can connect with them for a unique reason: these early Christian heroes walked and taught in the streets of our capital.

For Italian Latter-day Saints this recognition can be particularly significant because a shared history is central to the development of a stable and cohesive identity as a group. As Italian Mormons realize that they are surrounded by their own religious history, and that their history is not only to be found across the Atlantic in Palmyra, Nauvoo, or Independence, their identity as Italians, as Christians, and as Latter-day Saints will be validated.[8] Peter and Paul, as early Christian pioneers and, as it were, forerunners of a Mormon Christianity that would emerge much later, cannot be forgotten, especially in Italy, where they lived, taught, and died.

As an aside, perhaps something similar could be said about other Christians who came soon after these early apostles, Christians who either were Italians or lived in Italy for part of their lives. Some were intellectual pioneers, others were beacons of spirituality, and many were simply men and women of faith who did the best they could, often in contexts of great personal and social challenges. Yes, they lived in times that we consider problematic from a doctrinal perspective, but “the Great Apostasy” does not describe complete absence of light, truth, and inspiration. While there was loss of priesthood authority and partial corruption of truth, the faith and acumen of some of these martyrs, saints, and theologians can be truly inspiring, notwithstanding their imperfections and gaps of knowledge, which in any case characterize all human beings.[9] Thus, although Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Catherine of Siena, or Francis of Assisi, to name only a few, are not usually included in Latter-day Saint history, they could at least be added as an appendix or footnote, particularly in Italy.[10] In other words, in recounting the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Italy, I recognize that preparations, anticipations, inspirations, and confirmations, as well as the errors of prior centuries, fill the background of the broader picture.

The Nineteenth-Century Waldensian Harvest

Mormon missionaries in nineteenth-century Italy did not focus on the large Catholic population spread throughout the peninsula, but limited their efforts to a small geographical area in Piedmont populated by a Protestant minority that took the name of the Waldensians. The Waldensians originated in Lyon (southern France) in the twelfth century, where a man by the name of Valdès (or Waldo in English) distinguished himself by preaching a purer form of Christianity, in the form of strict adherence to the Bible and voluntary poverty.[11] He was soon declared heretical by Catholic authorities, and Waldo and his “Waldensian” followers had to relocate to the Piedmont valleys of northwestern Italy to escape persecution. Aided by the isolation provided by their alpine environment, the movement managed to survive and set roots notwithstanding ongoing opposition, including a 1487 order of extermination issued against them.[12] As a result of the Protestant Reformation, the Waldensian Church joined the Swiss Reformed tradition of John Calvin, thus becoming a Protestant denomination in the full sense of the term. The year 1848 was historic for the Waldensians, because liberty of conscience and civil rights were extended to them for the very first time through an edict of Charles Albert, the ruler of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia.[13] Two years later, the first Mormon missionaries arrived in the Waldensian valleys and began evangelizing Italy.

The favorable legal setting brought about by Charles Albert certainly contributed to the Latter-day Saint decision to proselytize among the Waldensians, but there is also more. Lorenzo Snow, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and one of the first Latter-day Saint missionaries to Italy, was fascinated by the Waldensians and their history; indeed, he thought of them as “the rose in the wilderness or the bow in the cloud.” When he visited a public library in Liverpool to learn more about the Waldensians, he read that they were a remnant of the original Christian Church and that they “had been the means of preserving the doctrines of the gospel in their primitive simplicity.”[14] Moreover, he saw visible parallels between the persecutions endured by the Latter-day Saints and the Waldensians. Sidney Rigdon, Brigham Young, and John Taylor also recognized these parallels.[15] Snow most likely felt that the doctrinal parallels between the two faiths—including an aspiration to Christian primitivism, the claim that apostasy had corrupted traditional Christianity, and a strong belief in spiritual gifts—would increase the Waldensians’ receptivity to the Mormon message. For these reasons, the first phase of missionary work in Italy between 1850 and 1865 centered almost exclusively in the four Waldensian valleys of Piedmont: Val Pellice, Val Angrogna, Val Chisone, and Val Germanasca.[16]

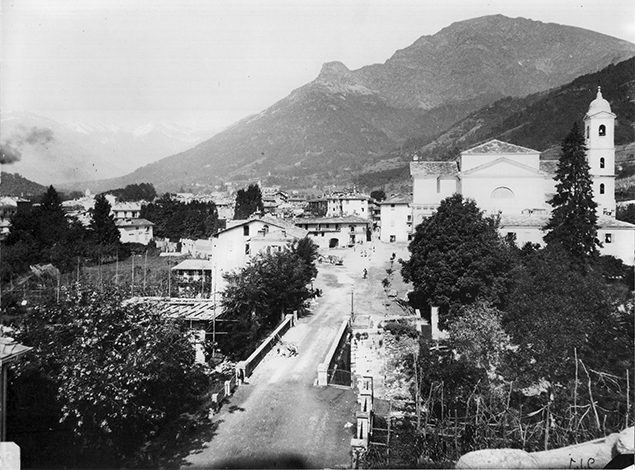

A photo of Torre Pellice in the 1880s. In the background are Monte Vandalino and the rock protrusion called Monte Castelluzzo on its left slope.

A photo of Torre Pellice in the 1880s. In the background are Monte Vandalino and the rock protrusion called Monte Castelluzzo on its left slope.

While facing numerous obstacles that included language barriers (most people spoke a dialect that mixed French and Italian), political and social problems, travel difficulties on challenging alpine terrain, ministers’ opposition, extreme poverty, discouragement, isolation, and conflicts internal to the Church, Mormon missionaries were able to obtain a degree of success in these early years.[17] Among them were Lorenzo Snow, Joseph Toronto (who was the first native Italian to join the Church in America), Thomas (TBH) Stenhouse, and Jabez Woodard. A total of twelve missionaries served in Italy between 1850 and 1865. On Mount Vandalino, in the vicinity of Torre Pellice, Snow dedicated the land of Italy to the preaching of the gospel, and in October 1850, Jean Antoine Bose was the first Waldensian baptized into the new faith. The following year would bring two prominent families into the Church: the Malans and the Cardons, numbering a total of about thirty individuals. At a time of very limited resources, their houses functioned both as meetinghouses and mission homes.[18]

Sixteen-year-old Marie Cardon had a remarkable dream at the age of six that was instrumental in leading her family to the missionaries. Several decades later she described that experience in these terms:

I saw three strangers dressed in black but [with] white shirts on. I looked up at them but did not speak. . . . They then spoke to me, saying fear not, we are the servants of God and have come to preach the everlasting Gospel of Jesus Christ. . . . Again, these three men or two of them put their hands in their pockets and took out a small book which contained articles of the everlasting Gospel. One of the books had a pale blue cover while the other had pale green cover. They handed their books to me to read; then they said the day would come when my parents and family would embrace this Gospel and others of the house of Israel would also embrace this Gospel and the day was not far when we would repent and be baptized in the name of the Father and the son and holy ghost and would be called to Zion. They spoke of our journey on the desert plains and many a thing which pertained to our future.[19]

Marie’s father, Philippe, would never forget this vision, and when he heard of American preachers who had come to teach a different form of Christianity, he was motivated to listen to them, to see whether Marie’s earlier dream could be fulfilled in his encounter with them. He came to the conclusion that it was indeed so.

Baptism of Ada Properzi in Gorizia (December 1976). Also present: Roberto Properzi (left), Elder Steven Horner (right), and Mauro Properzi (below).

Baptism of Ada Properzi in Gorizia (December 1976). Also present: Roberto Properzi (left), Elder Steven Horner (right), and Mauro Properzi (below).

Gorizia Branch (February 1987).

Gorizia Branch (February 1987).

About 180 Waldensians converted to Mormonism during the fifteen years of the first mission, most having joined in the first five years of missionary activities. Three branches of the Church were established in the valleys, but three major emigrations in 1854 and 1855 led about a third of all converts to Utah.[20] The remaining converts from these early mission years either incurred excommunication, returned to the Waldensian Church, or are unaccounted for.[21] Missionaries did attempt to spread the Mormon message into Catholic Italy through brief forays into the cities of Genova and Turin, but these efforts were largely unsuccessful. Records only point to one baptism in Genova in 1853: a nineteen-year-old young man by the name of Giovanni Battista Paganini. This stark lack of success resulted in much discouragement among the missionaries.

In the meantime, a major conflict arose in the valleys that did not lift any spirits. A missionary, Samuel Francis, and the local branch president, Elder Ruban, fell in love with the same school teacher, Miss Weisbrodt, who had been baptized by Ruban but later married Francis. Her baptism raised the ire of her father, a German diplomat at the embassy in Turin, which further increased opposition to Mormon missionary activities. In addition to these conflicts, Waldensian pastors did not sit idly by while witnessing parts of their flocks being lured into a different religion, and consequently fought back against the spread of Mormonism. All in all, many things—external obstacles, migration, internal conflict, and poverty, as well as the dwindling number of missionaries being called to serve in Europe given the growing trouble between the Church and the US government—contributed to the waning presence of Mormonism in Italy. When the mission was closed at the end of 1867, only one family of six individuals was the remaining Latter-day Saint presence.[22]

An addition of less than two hundred converts may appear meager, especially in light of the fact that permanent conversions only ranged between seventy and eighty individuals. However, it should be remembered that the Waldensian population in the valleys did not exceed twenty thousand individuals, a number that kept decreasing because of emigration. Hence, despite seeming small, a 1-percent conversion rate was not utterly inconsequential, and the opposition that missionaries attracted points to the fact that their presence and activities were not unbeknown to most. In short, Mormonism left a mark, minor as it may be, in Waldensian history. A Waldensian politician, whom I interviewed in 2014, confirmed this conclusion by telling me that he had always known that nineteenth-century Mormons had renamed Mount Vandalino “Mount Brigham.” He had heard it as a child when living in the vicinity of Torre Pellice at the footsteps of that very mountain.[23]

Parenthetically, this Italian senator, Lucio Malan, is an important connecting link between Mormonism in twenty-first-century Italy and its brief nineteenth-century appearance among the Waldensians. Malan, as well as other Waldensian politicians, academics, and individuals of Catholic persuasion, were strong supporters of the Church’s application for intesa status (or agreement) with the Italian government. This agreement, approved in 2012, recognizes the Church as a partner of the state and gives it every right and privilege enjoyed by all other major religions in the country. In other words, through an act of Parliament, the Church is now fully recognized and legally accepted into Italian society. Thus, Mormons and Waldensians in Italy have seen a change in their relationship, from conflict in the nineteenth century to collaboration in the twenty-first, a topic on which I have written more extensively elsewhere.[24]

The author (left) with Waldensian senator Lucio Malan (right) at the Italian Senate in Rome (May 2014).

The author (left) with Waldensian senator Lucio Malan (right) at the Italian Senate in Rome (May 2014).

In returning to 1867 it should be remembered that missiology in nineteenth-century Mormonism differed broadly when compared to the present, both in perspective and objective. Nineteenth-century Mormonism was strongly millenarian because the Saints anticipated an imminent return of the Savior to the earth. Missionaries’ efforts were focused on several things: first, on finding the “blood of Israel” that had been scattered throughout the nations; second, on teaching the restored gospel to these elects; and third, on gathering them to the American Zion in preparation for the Second Coming of the Lord. When the stalwart Waldensian members had emigrated and the number of baptisms continued to dwindle, the use of missionary resources in that part of the world was viewed as unjustified. It was easy to conclude that the harvest was complete and that the elects, although few in numbers, had been found and gathered.[25]

A Second Mission in Twentieth-Century Italy

The Latter-day Saint Church would not officially return to Italy for another century, an early departure and a belated return that is crucial “to explaining the Church’s relative lack of success, compared to other denominations, in more recent decades.”[26] In fact, with several Protestant denominations evangelizing Italy in the second half of the nineteenth century, census records indicate that by 1911, over 120,000 Italians identified themselves as Protestant. What, then, are the reasons for the prolonged Mormon absence? They can be traced both to factors internal to the Church and to historical events that affected Italy’s “openness” to the Mormon message.

In regard to the former, Mormon attitudes toward Italy and Italians were influenced by American views about the same, including a romantic perspective of the country on the one hand, and a negative profiling of its people on the other.[27] Italians were generally viewed as uneducated and immoral, and the fact that they were Catholic only made things worse. Pragmatically, since early Mormon missionary successes came from Protestant countries, missionary resources tended to be allocated to those countries and not to Catholic ones.

As to Italy’s receptivity to the Mormon message, the extensive presence and influence of the Catholic Church obviously functioned as an obstacle. However, the Second Vatican Council, extending from 1962 to 1965, led to greater openness and opportunities for other religions. This ecumenical council led to an aggiornamento, or updating, of the Catholic Church’s approach to the modern world, which, among other things, brought about significant changes in the direction of greater openness toward other religions. For example, the council unequivocally affirmed, through the declaration Dignitatis Humanae, that every human being possesses an inherent right to religious liberty.[28]

Vincenzo Di Francesca lived in this interim period, between the “first” and “second” Italian missions. He received churchwide recognition as a pioneer of Mormonism in Italy through a 1987 Church video entitled How Rare a Possession. I cannot do justice to his remarkable life in this setting but can only highlight the fact that he first read the Book of Mormon in 1910, was baptized in 1951, and traveled to the newly dedicated Swiss Temple in 1956. He died in 1966, the year the Italian mission was reopened, having spent his whole life in almost complete isolation from the Church, but remaining faithful to its teachings.[29] Although Di Francesca is the best-known Mormon pioneer in twentieth-century Italy, the social isolation and opposition that he experienced were not foreign to other Italian members, both before and after the mission’s reopening.[30]

Vincenzo di Francesca at the Swiss Temple with President and Sister Erickson.

Vincenzo di Francesca at the Swiss Temple with President and Sister Erickson.

The second phase of missionary work in Italy owes its existence to the internationalization of the Church under the administration of President David O. McKay. Evidence points to discussions of and explorations into the possibility of reopening Italy to missionary work as early as the 1950s. In 1965, just a few months before the conclusion of the Second Vatican Council, the Italian zone of the Swiss mission was formed, and missionaries were sent to seven Italian cities, mostly in the north. This is where Latter-day Saint American servicemen resided, as well as a handful of Italian members who had converted in Switzerland, France, or Germany prior to returning to their homeland. Missionaries who had been reassigned to Italy from Switzerland or Germany generally commented that work in Italy was easier than in Germany because people were more welcoming. One missionary described Italy as “heaven,” and another described it as “the celestial kingdom.” The number of baptisms matched this enthusiasm, and the branches in two cities, Brescia and Palermo, were entirely made up of Italians.[31]

In August 1966, and with only forty-two members in the whole country, Elder Ezra Taft Benson opened a separate Italian mission (to be presided over by John Duns) in Florence. A few months later, Benson also rededicated Italy to the preaching of the gospel during a small private service in the vicinity of Torre Pellice, in Piedmont, where President Lorenzo Snow had first dedicated the land to missionary work.[32] Thirty-five cities were opened to missionary activities before the end of the year, and the hard work of building the Church from the ground up began in earnest. Efforts were aimed at improving the image of the Church at the macro level and at contacting and teaching individuals at the micro one. The mission experimented with several creative ways to bring the Church out of obscurity, including music performances by missionary singers, sporting events with a mission basketball team, and public showings of Church movies, especially Man’s Search for Happiness. Membership grew slowly but steadily, notwithstanding the challenge of needing to train inexperienced native leaders, the limited number of physical facilities and of Church materials in Italian, difficulties in public relations, and other obstacles that are typical of an emergent-church setting.[33]

Group at the dedicatory prayer service near Torre Pellice, Italy, Elder Ezra Taft Benson is in the middle of the group.

Group at the dedicatory prayer service near Torre Pellice, Italy, Elder Ezra Taft Benson is in the middle of the group.

A second Italian mission was created in 1971, and statistics point to the presence of almost 1,500 members organized into twenty-five Italian branches and four servicemen’s groups. In the late ’70s, “the golden age” of missionary work in Italy, two additional missions were created, bringing the total number to four (but later consolidated back to two). At this time, members were strengthened and encouraged by the visits of two Church Presidents, Harold B. Lee and Spencer W. Kimball, who brought added media exposure to the Church. As previously indicated, my family joined during this decade, as did many others.[34]

Parenthetically, this was a challenging time for Italy and its people as the country experienced a period of economic recession, social change, and unprecedented political violence. Murders and massacres by both right- and left-wing terrorist groups swept the country and left hundreds dead. These were gli anni di piombo, or “the years of lead,” and perhaps the general climate of anxiety and the need for answers about the meaning of life led some to open their hearts to the message of the missionaries.[35] For our family, one such humbling experience was the May 1976 terremoto del Friuli, one of the deadliest earthquakes in the history of Italy, with one thousand fatalities and damages worth billions of dollars.[36] Thankfully, my family emerged unscathed, but we lost our home, which was located only about seven miles from the earthquake’s epicenter. A few months later, after our move to Gorizia, the missionaries knocked at our door.

Accelerated conversion rates in the seventies and early eighties led to the construction of the first chapel in Pisa (1979) and to the formation of the first two Italian stakes in Milan (1981) and Venice (1985). I vividly remember this latter meeting, presided by Elder David B. Haight, and the great enthusiasm that accompanied it. Becoming a stake felt like “coming of age” for the Church in my area.

After this “golden age” of missionary work came three decades of slower growth, characterized by difficulties in retaining new members and by heavy burdens of responsibility for local leaders.[37] When I served my mission in southern Italy between 1993 and 1995, the Italy Catania Mission had no stakes within its boundaries. The number of stakes has increased significantly only in the last ten years, with part of the growth being due to the influx of Latter-day Saint immigrants, especially from South America. Indeed, it is estimated that at least 20 percent of the membership of the Church in Italy is now composed of immigrants. At present, ten Church stakes are functioning in the country, and evidence of maturation in local leadership can “be found in the calling of many Italians to senior positions in the church hierarchy: seven mission presidents . . . a Swiss Temple president . . . and numerous regional representatives, area seventies, and stake presidents.”[38] A milestone was reached in April 2016 with the calling of Elder Massimo De Feo as the first Italian General Authority.

The slow but steady trajectory of growth and public visibility was punctuated by some landmark events. Among these is the Mormon Tabernacle Choir’s visit to Italy during its 1998 European tour.[39] This event’s coverage by the Italian media contributed to a very positive meeting between Elder Uchtdorf from the Church’s Europe West Area leadership and Oscar Luigi Scalfaro, president of the Italian Republic.[40] An even more significant development took place in 2008 with President Monson’s historic announcement of the Church’s plans to construct a temple in Rome. Also momentous was the 2012 signing of the previously mentioned intesa (or agreement) between the Church and the Italian government, the contract between FamilySearch and the Italian National Archives that allowed FamilySearch to fully digitize the archives’ historical records, and the increased publicity of the Church that resulted from Mitt Romney’s campaign for the US presidency.[41] The next milestone of the Church’s visibility in Italy will be the temple’s completion and dedication.

Rendition of the Rome Italy Temple.

Rendition of the Rome Italy Temple.

While these major events have given and will continue to give greater visibility and exposure to the Church, these milestones can only do so much in bringing the Church out of obscurity. Ultimately, it is the sustained effort of Italian Latter-day Saints at the local and national level that will change the hearts and minds of those who observe and describe us. In recent years, the Italian media’s most positive articles on the Church have been those that announced or reported community service, cultural activities, and interfaith/

Being a Mormon in Italy

I have often been asked, “What was it like to grow up as a Mormon in Italy?” After the usual “Where do you want me to start?” counter question, I generally introduce my response with what must appear like a contradictory statement, “It was both wonderful and very hard.”

Terryl Givens, a noted Latter-day Saint scholar of Mormonism, echoes this message in his book People of Paradox, in which he outlines some key tensions and paradoxes that are inherent to the world of Mormonism. These tensions are not problematic in themselves because they do not represent contradictions that need to be resolved; while they do point to an apparent paradox between principles, the principles are ultimately complementary when kept in the proper balance. Hence, such tensions are necessary to Mormonism’s vitality, although the ideal balance is elusive and difficult to achieve. Givens lists four tensions or paradoxes that broadly characterize Mormon culture, including authority versus freedom, searching versus certainty, the sacred versus the banal, and uniqueness versus assimilation.[43] My experience as a member of the Church in Italy distinctively manifests some of these tensions, which is one of the reasons why I can describe it as being both wonderful and difficult.

Space allows me to only offer a couple of illustrations. When I recently became a citizen of the United States, I recognized that what I have felt in my soul for most of my life is now also true on paper: I am a citizen of Italy and of the United States. I am a bicultural being, a person with two homes, and I am someone who is always going to find himself caught, to some degree, between two worlds. When I think of my religious identity, I cannot help but realize that this tension is also deeply embedded in my commitment and loyalty to Mormonism. On the one hand, in Italy I dreamed of the day when I could attend BYU, visit Temple Square, and perhaps see one of the apostles and prophets whose words I read on paper, but whose presence I didn’t experience (the internet was not yet around). I wanted, so to speak, to be fully immersed in the Church I loved, and I thought that such immersion could only happen in its center, in my spiritual promised land. In short, I felt I needed to be here in order to fulfill my identity as a Mormon. At the same time, I felt that the Church needed all the strength it could use in Italy, and I wanted to dedicate all that I had in its service. I felt how much my own faith and commitment were owed to my parents and leaders, and recognized that Italian Latter-day Saints were brothers and sisters with whom I shared a unique connection. To put it differently, without my Italian experience of Mormonism I now struggle to even imagine what my faith would be like.

While most Italian Mormons are not so torn between these two worlds, some may experience a degree of paradox in relation to the nationality of our faith. The messy Italian-American nature of our religious life may at times be difficult to deal with and may raise questions about our spiritual identity. As a young man I often failed to distinguish between Mormon culture, language, practices, and organization and the restored gospel of Jesus Christ—partly because the full package of Mormonism and the eternal reality of the gospel were often presented, whether consciously or unconsciously, as conflated. Hence, one of the challenges of this century, as the Church moves increasingly into a world that is global and multicultural, is to root conversion in Christ through the needed instrumentality of the Church and not the other way around. The challenge is then to distinguish between the essentials of the gospel, which must remain solid and non-negotiable, and the distinct cultural manifestations of its principles in action, which can coexist in diverse localized expressions.

Givens’s binary of uniqueness versus assimilation is also particularly visible in the Church in Italy, specifically in the tension that exists between a Latter-day Saint identity that is exclusive and a Christian identity that is broader and more inclusive. Growing up in Italy I probably did not experience this tension as much as I should have. As a member of a small religious minority, and one that was mostly unknown, misunderstood, or caricatured in public perception, I often lived my faith with a siege mentality, mainly looking at the world that surrounded me with suspicion. I learned to defend my faith by giving it full loyalty in the face of opposition, but I did not learn how to work with people of different faiths to bring about good in the world. Although no specific experiences led me to feel this way, I often felt that other churches, and especially the majority Catholic Church, were the enemy. All that mattered was Mormonism, and all truth was to be found within the boundaries of Mormonism: I was always first and foremost a Latter-day Saint, who also happened to be a Christian. In short, I had quite a provincial view on how God operates in the world.

The Church did not explicitly point me in this direction. Yet, a certain isolationism, both brought in from the outside and reinforced from the inside, may often emerge as one of the less ideal characteristics of small religious minorities. No doubt, few who knew me then would have expected that years later I would end up studying for a year at a Vatican university, begin to interact and cooperate with Catholic priests and bishops, and become the go-to person for some of my colleagues at BYU on questions about Catholicism. Indeed, I now enjoy studying the Catholic intellectual tradition and often find inspiration in various forms of its rich spirituality. And when I see the great work of public relations, cooperation, and civic engagement that the Latter-day Saint Church has recently carried out in Italy, I sort of feel that the Church and I have grown up together, that we have found a better balance. In other words, we can continue to love and treasure our unique truths without ignoring or discounting God’s hand among our brothers and sisters of different faiths.

If uniqueness was emphasized a little too much in my experience as a young Italian Mormon, the other side of the coin is that this emphasis protected me from the opposite danger of assimilation. The courage to be different was inculcated in me as it was in many other Italian Latter-day Saints, who experienced that difference on a daily basis. Thus, when social and cultural pressures pushed against gospel truths, the choice was at least clear, although not necessarily easy. Some things were, and continue to be, either right or wrong, and whether or not I had the courage to stand up for truth, truth did not change. The call to be enlisted in the Lord’s cause seemed to echo without pause every week and every day, and the need for a testimony could not be postponed or ignored. Circumstances of this kind can be tiring, even lonely, especially for youth, but they can also lead to great unity in purpose and to a strong sense of identity as a people who are united in this struggle.

Tensions of this kind have deeply shaped who I am and continue to inform my role as a teacher of Latter-day Saint university students, who live in an increasingly difficult world. In this capacity, one of my biggest challenges and responsibilities is to help our youth achieve a balance between openness and conviction, or, to use Givens’s terms, between searching and certainty. Humility in knowledge leads to the pursuit of all goodness that can be found in the world, whereas firmness in one’s faith and the associated courage to face opposition or mockery of one’s beliefs and values lead to deep commitments and character development. The quest for this balance is never-ending, but many Italian Saints have shown me the way as they have inspired, loved, and taught me to be much of what I am. Whatever successes I have obtained, in my family and career, are also their successes, and their story is also my story. I echo President Benson’s words from his 1966 rededicatory prayer of Italy, “We know, Heavenly Father, that Thou dost love Thy children and we have in our hearts a love for the Italian people as we assemble here today, and, Holy Father, we pray Thee that Thy blessings may be showered upon them.”[44]

Notes

[1] Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary, 11th ed., s.v. “pioneer.”

[2] An insightful sociological analysis of Mormonism in Europe is Armand L. Mauss, “Can There be a ‘Second Harvest’? Controlling the Costs of Latter-day Saint Membership in Europe,” International Journal of Mormon Studies 1 (2008): 1–59. For the complex reality of religion in twenty-first-century Europe, see Grace Davie, “Religion in Europe in the 21st Century: The Factors to Take into Account,” European Journal of Sociology 47, no. 2 (August 2006): 271–96.

[3] A forthcoming publication, which I have consulted extensively, will undoubtedly be the latest comprehensive reference on the history of the Church in Italy. James A. Toronto, Eric R. Dursteler, and Michael W. Homer, Mormons in the Piazza: The History of the Latter-day Saints in Italy (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, forthcoming).

[4]“Map of Gorizia,” Google Maps, https://

[5] Wikipedia, s.v. “Istrian Exodus,” https://

[6] An interesting sociological comparison between a Utah and a New Jersey ward that highlights some of these dynamics is found in Rick Phillips, Saints in Zion, Saints in Babylon: Religious Pluralism and the Transformation of Mormon Culture (n.p.: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014).

[7] Acts 28:12–13.

[8] Stuart Hall, “Cultural Identity and Diaspora,” in Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, ed. J. Rutherford (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1990), 222–37. Cultural identity is based on “one shared culture, a sort of collective ‘one true self,’ hiding inside the many other, more superficial or artificially imposed ‘selves,’ which people with a shared history and ancestry hold in common” (p. 223).

[9] Miranda Wilcox and John D. Young, eds., Standing Apart: Mormon Historical Consciousness and the Concept of Apostasy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[10] Henry Chadwick, Augustine: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001); Francis Selman, Aquinas 101: A Basic Introduction to the Thought of Saint Thomas Aquinas (Notre Dame, IN: Christian Classics, 2007); Mary O’Driscoll, ed., Catherine of Siena: Passion for the Truth—Compassion for Humanity (New York: New City Press, 2005); G. K. Chesterton, Saint Francis of Assisi (n.p.: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013).

[11] The preferred phonetic spelling of the founder’s name is Valdès, although he has also been referred to as Vaudès, Waldo, and even Peter Waldo. See Gabriel Audisio, Preachers by Night: The Waldensian Barbes (15th—16th Centuries) (Leiden: Brill, 2011); also Giorgio Tourn, Giorgio Bouchard, Roger Geymonat, and Giorgio Spini, You Are My Witnesses: The Waldensians across 800 Years (Turin: Claudiana, 1989), 309. Other excellent general sources on the origins of the Waldensians and their establishment in northern Italy are Giorgio Tourn, I Valdesi: La Singolare Vicenda di un Popolo-Chiesa (Torino: Claudiana, 1977); Giorgio Spini, Risorgimento e Protestanti (Torino: Claudiana, 1998); and Augusto Armand Hugon, Torre Pellice: Dieci Secoli di Storia e di Vicende (Torre Pellice: Società di Studi Valdesi, 1980).

[12] See Euan Cameron, The Reformation of the Heretics: The Waldensians of the Alps, 1480–1580 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984); and Gabriel Audisio, The Waldensian Dissent, Persecution and Survival, c. 1170–c. 1570 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

[13] American Waldensian Society, “History,” http://

[14] Lorenzo Snow, Italian Mission (London: W. Aubrey, 1851), 10–11. Numerous Protestant publications in the nineteenth century promulgated this thesis of the Waldensians’ ancient origins. See, for example, Alexis Muston, Histoire des Vaudois (Paris: F. G. Levrault, 1834); William Fison, The Evangelists of Italy: Or the Mission of the Apostolic Waldensian Church (London: Werthein & Macintosh, 1855); and J. A. Wylie, The History of Protestantism, 3 vols. (London: Cassell & Company, 1878). For details of this historical controversy, see Homer, “The Waldensian Valleys.”

[15] “Faith of the Church of Christ in These Last Days, No. IV,” The Evening and the Morning Star 2 (June 1834): 162; Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool: F. D. Richards, 1855–86), 5:342; and Journal of Discourses, 24:352.

[16] Concerning the Italian mission, see Michael W. Homer, “‘Like the Rose in the Wilderness’: The Mormon Mission in the Kingdom of Sardinia,” Mormon Historical Studies 1, no. 2 (Fall 2000): 25–62; Homer, “The Italian Mission, 1850–1867,” Sunstone 7 (May–June 1982): 16–21; James A. Toronto, “‘A Continual War, Not of Arguments, but of Bread and Cheese’: Opening the First LDS Mission in Italy, 1849–1867,” Journal of Mormon History 31, no. 2 (Summer 2005): 188–23; Diane Stokoe, “The Mormon Waldensians” (Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1985); and Flora Ferrero, “L’emigrazione valdese nello Utah nella seconda metà dell’800” (Tesi di Laurea: Università di Torino, 1999). Also see Toronto, Dursteler, and Homer, Mormons in the Piazza, chap. 1.

[17] Homer, “‘Like the Rose in the Wilderness,’” and Toronto, “‘A Continual War.’”

[18] Toronto, Dursteler, and Homer, Mormons in the Piazza, chap. 2.

[19] Marie Madeleine Cardon Guild, letter, January 12, 1903, Correspondence 1898–1903, MS 894, LDS Church Archives. Some slight spelling revisions and punctuation have been added to facilitate reading.

[20] Toronto, Dursteler, and Homer, Mormons in the Piazza, chap. 3.

[21] See “Record of the Italian Mission,” in Richards, Scriptural Allegory, 301; also Italian Mission Manuscript History and Historical Reports, 1849–1854, LR 4140 2, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[22] Samuel Francis, journal, December 11, 1856, Church History Library, Salt Lake City; and Toronto, Dursteler, and Homer, Mormons in the Piazza, chap. 4.

[23] Senator Lucio Malan, interview with the author on May 28, 2014.

[24] Mauro Properzi and James A. Toronto, “From Conflict to Collaboration: Mormons and Waldensians in Italy,” in The Worldwide Church: Mormonism as a Global Religion, eds. Michael A. Goodman and Mauro Properzi (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2016), 263–287; Toronto, Dursteler, and Homer, Mormons in the Piazza, chap. 14.

[25] Toronto, Dursteler, and Homer, Mormons in the Piazza, chap. 6.

[26] Toronto, Dursteler, and Homer, Mormons in the Piazza, chap. 6. Also see Eric R. Dursteler, “One Hundred Years of Solitude: Mormonism in Italy, 1867–1964,” International Journal of Mormon Studies 4 (2011): 119–48.

[27] Alexander DeConde, “Endearment or Antipathy? Nineteenth-Century American Attitudes toward Italians,” Ethnic Groups 4 (1982): 132–33.

[28] John W. O’Malley, What Happened at Vatican II (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2010). “Declaration on Religious Freedom, Dignitatis Humanae,” http://

[29] Di Francesca, Don Vincenzo. Burn the Book (n.d.), MS 12191, Church History Library, Salt Lake City; MS 13163, Duns, John. Vincenzo di Francesca Collection; MS 9290, 12 March, 1966, Vincenzo di Francesca to Ortho Fairbanks; MS 12237, Neil, John Martin, 1945—Reminiscences about Vincenzo di Francesca. Also MS 13413; “Pres. Bringhurst Baptizes First Convert in Sicily,” Deseret News, 28 February, 1951, 12–3; LR 8884-2, Swiss-Austrian Mission Manuscript History and Historical Reports, vol. 12, 28 April, 1956–2 May, 1956.

[30] Toronto, Dursteler, and Homer, Mormons in the Piazza, chap. 7.

[31] Bruno Vassel, interview with Jim Toronto, July 27, 2006, Salt Lake City, UT, and Lloyd Baird, interview with Jim Toronto, August 23, 2005, Provo, UT. Also see James A. Toronto, “The ‘Wild West’ of Missionary Work: Reopening the Italian Mission, 1965–71,” Journal of Mormon History 40, no. 4 (Fall 2014): 1–72.

[32] James A. Toronto and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, “The LDS Church in Italy: The 1966 Rededication by Elder Ezra Taft Benson,” BYU Studies Quarterly 51, no. 3 (2012): 83–100.

[33] Toronto, Dursteler, and Homer, Mormons in the Piazza, chap. 8–9.

[34] Toronto, Dursteler, and Homer, Mormons in the Piazza, chap. 10.

[35] “Years of Lead (Italy),” Wikipedia, https://

[36] “1976 Friuli Earthquake,” Wikipedia, https://

[37] Toronto, Dursteler, and Homer, Mormons in the Piazza, chaps. 11–13.

[38] Toronto, Dursteler, and Homer, Mormons in the Piazza, chaps. 11–13.

[39] Mya Tannenbaum, “L’America dei coristi mormoni,” Corriere della Sera, June 24, 1998; Luca Della Libera, “Il Coro dei Mormoni, lezione di cultura a Santa Cecilia,” Il Messagero, June 24, 1998, 35; Giorgia Caruso, “La musicalità liturgica si fa a stelle e strisce,” Secolo d’Italia, June 25, 1998, 18; and Enrico Cavallotti, “Il Coro dei Mormoni: meraviglia americana,” Il Tempo June 24, 1998.

[40] “Italian President Greets Leaders: Reiterates Support of Families, Prayer,” Church News, January 9, 1999.

[41] “Italian Ancestors,” FamilySearch, https://

[42] Mauro Properzi, “Mitt Romney and ‘I Mormoni’: A 2012 Analysis of Italy’s Print Media,” BYU Studies Quarterly, 53, no. 1 (2014): 75–105.

[43] Terryl L. Givens, People of Paradox: A History of Mormon Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 3–62.

[44] Sheri L. Dew, Ezra Taft Benson: A Biography (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1987), 390–91.