To Whom Is the Arm of the Lord Revealed?” Part 1

Aaron P. Schade and Matthew L. Bowen

Aaron P. Schade and Matthew L. Bowen, "'To Whom Is the Arm of the Lord Revealed?' Part 1," Religious Educator 16, no. 2 (2015): 90–111.

Aaron P. Schade (aaron_schade@byu.edu) is a professor of ancient scripture at BYU.

Matthew L. Bowen (matthew.bowen@byuh.edu) is an assistant professor in Religious Education at BYU–Hawaii.

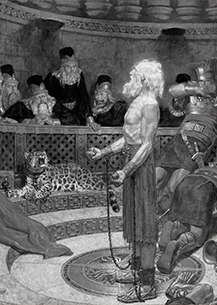

In King Noah's court, Abinadi quotes Isaiah's great poem on the Suffering Servant (Isaiah 53) as evidence that "God himself" would indeed "come down among the children of men and...redeem his people."

In King Noah's court, Abinadi quotes Isaiah's great poem on the Suffering Servant (Isaiah 53) as evidence that "God himself" would indeed "come down among the children of men and...redeem his people."

Perhaps the most important of the texts that Alma the Elder heard Abinadi quote in King Noah’s court was Isaiah’s great poem on the Suffering Servant (Isaiah 53) as evidence that “God himself” would indeed “come down among the children of men and . . . redeem his people” (Mosiah 15:1; italics throughout indicate authors’ emphasis). Abinadi begins his citation thus: “Yea, even doth not Isaiah say: Who hath believed our report, and to whom is the arm of the Lord revealed?” (Mosiah 14:1; see also Isaiah 53:1). Of all the priests and other observers in King Noah’s court, only Alma believed Abinadi’s report, or testimony (Mosiah 17:2; 26:15). Alma’s faith in Abinadi’s words led to his becoming a prophet—one who would become the Savior’s “seed” and “declare [the Savior’s] generation (Mosiah 15:10–13)—as Alma himself would go forth and proclaim the hallowed message of Isaiah in efforts to prick the hearts of listeners (Mosiah 18:1–3).

Among all of Isaiah’s prophetic reports, Isaiah 53 has particularly proven to be the source of conversion for individuals seeking truth, the medium through which faith in Christ is instilled within them by the power of its message.[1] Alma, Alma the Younger, and their audiences become additional witnesses to the power of Isaiah’s message, as they continue to use the text of Isaiah 53 (and 52:7ff) in their sermons and teachings.[2] The significance of Abinadi’s usage of Isaiah, and the role it plays in the conversion of Alma, as well as for his son Alma the Younger, is evident as it becomes the catalyst for numerous later conversions.

Our paper will discuss Isaiah’s prophecies that were used by the prophet Abinadi, as he warned the priests of Noah that they were not saved by the law of Moses alone, but by the one to whom the law pointed and represented,[3] the one who has the ability to make us his “seed” (Isaiah 53:10; Mosiah 14:10; 15:10–13). In this paper we particularly examine the implications of Abinadi’s use of Isaiah 53:1 and 53:10 as an exegetical response to Isaiah 52:7–10 for Alma personally, whom we believe is the unnamed priest posing the questions surrounding these Isaiah passages, and to whom these Hebrew verses poignantly speak, resulting in the revelation which would cause Alma to believe and then become the proclaimer of this message to his later converts who would be blessed by Isaiah’s message of redemption, a process started by Abinadi’s recitation of Isaiah’s testimony of Christ.

“One of Them”

It is both inspiring and instructive how Abinadi uses Isaiah 53 to answer the exegetical question raised by one of Noah’s priests about Isaiah 52:7–10 (see Mosiah 12:20–24). The exchange between Noah’s priests and Abinadi over Isaiah’s words began when an unnamed priest quoted these Isaiah passages (see Mosiah 12:24–27). “One of them” had asked for the interpretation (Mosiah 12:21–24), the theme of which revolves around publishing “peace” and “salvation.” If the phrase “one of them” (Mosiah 12:20) corresponds to the phrases “one among them, whose name was Alma” (Mosiah 17:2) and “Amulon knew Alma, that he had been one of the king’s priests, and that it was he that believed the words of Abinadi” (Mosiah 24:9), we have several strong narratalogical suggestions that Alma was the “one” asking the question, just as he is the only one who ends up listening and eventually “believing.”[4] What may further lead us to the conclusion that Alma is the one asking the question is that all of the priests declare, after Abinadi accuses them of wickedness, that they are “guiltless” (Mosiah 12:14); however, they are all astonished when “one” seems to inquire about a message of hope, not the destruction that accompanies unrighteous behavior. Abinadi’s words cut them to their hearts (Mosiah 13:7) and they are all filled with “wonder and amazement, and with anger” (Mosiah 13:8). However, through all of this it is “one among them whose name was Alma” who will know “concerning the iniquity which Abinadi had testified against them” (Mosiah 17:2), and believes and seeks to spare Abinadi’s life. Alma must then flee and hide himself from Noah and the priests, and he will “write all the words which Abinadi had spoken” (Mosiah 17:4).

Perhaps Alma’s heart was beginning to be softened and pricked by Abinadi’s message detailing the consequences of sin and the hope of repentance, even as the priests’ efforts to ensnare Abinadi began. While it is possible that the questions raised in and by the citation of Isaiah 52:7–10 (Mosiah 12:20–24) represent a continuation of the ensnaring efforts of Noah’s priests (Mosiah 12:19), it is also possible that they constitute a sincere desire for an answer from a “young man” (Mosiah 17:2) with a troubled soul, who would later preach “the redemption of the people, which was to be brought to pass through the power, and sufferings, and death of Christ, and his resurrection and ascension into heaven” (Mosiah 18:2). The identification of the unnamed priest as Alma is thus crucial in understanding how and why Alma so frequently turns to these passages as he describes not only his own conversion, but how he uses these principles to lead others to repentance and peace.[5] Ironically, because Noah, his priests, and his people refuse to repent and instead assent to Abinadi’s death, they will instead suffer what the Suffering Servant will suffer (Isaiah 53; see also especially D&C 19:16–17, 20). Contrary to what they believed, the blessings described in Isaiah 52:7–10 and 53, including “see[ing] eye to eye”, are predicated[6] upon individuals adjusting their vision to see through revelation the benefits of Christ’s Atonement (Isaiah 53) and applying it, rather than God redirecting his vision to tolerate their sins. They will suffer on account of their spiritual stubbornness and self-presumed innocence and strength (Mosiah 12:14–15, “we are strong, we shall not come into bondage”), in contrast to the power of the arm of God.[7]

In conjunction with Isaiah’s message of deliverance based on the merits of the Atonement, Abinadi prophesies that King Noah, his priests, and his people, rather than enjoying peace in Christ, the Suffering “Servant” (the ʿebed of Isaiah 53), will suffer and be brought into “bondage” (Hebrew ʿăbōdâ, i.e., “servitude,” another wordplay recalling the one who could have helped them avert this). This will happen as a result of their refusal to repent of their sins (Mosiah 11:20–26; 12:2–8)—sins which will eventually include rejecting the Lord’s servant Abinadi and the Lord himself (the “Suffering Servant”). Because of Abinadi’s martyrdom, eventually even Alma and those who “believe” his words will, in the process of becoming the Lord’s servants, come to know suffering and bondage themselves at the hand of Amulon. But their suffering and burdens will be made light (Mosiah 24:15) and they will eventually be delivered from bondage through the grace of Christ and his Atonement because of their repentance and faith in him (Mosiah 24:16, cf. Isaiah 14:3). In a telling turn of events, Amulon and his brethren, who are heaping these burdens upon Alma and the believers, teach their followers nothing concerning Alma’s “God, neither the law of Moses; nor did they teach them the words of Abinadi” (Mosiah 24:5).

If we look at the big picture of these episodes—assuming Alma is indeed the one asking the question leading to Abinadi’s exposé on Isaiah 53—what follows becomes even more significant within the context of Abinadi’s sermons, as he uses the Hebrew text to highlight the redemptive power of Jesus. Abinadi makes clear that the “peace” and “salvation” mentioned in Isaiah 52:7–10 (Mosiah 12:20–24) are not obtained through wickedness,[8] or even by outward obedience to the law (Mosiah 13 passim, especially vv. 27–28), but only through the “salvation” (yĕšûʿâ)[9] and redemption of Jesus (yēšûaʿ)—a play on the Savior’s name. As John W. Welch has observed concerning the efforts of Noah’s priests to justify their wickedness and their efforts to convict and discredit Abinadi, “Abinadi's rebuttal was an extensive and brilliant explanation of the true essence of redemption and how it brings good tidings to those who accept Christ (see Mosiah 12:29–37 and chapters 13–16). . . . The priests had taken Isaiah 52:7–10 out of context in accusing Abinadi; he averted their attack by putting that passage of scripture back into its surrounding context.”[10] Abinadi used Isaiah 53 to describe a different kind of “peace” (“the chastisement of our peace was upon him,” 53:5) and to identify the one “publish[ing] peace” as “the founder of peace” (Mosiah 15:18), Jesus Christ.[11] He also uses this text to identify Christ’s other servants, as his seed, especially the prophets and saints who preach the “good tidings.”

Alma Believes Abinadi’s Report (Mosiah 17:2)

Alma’s miraculous conversion, and the backdrop of Abinadi’s usage of Isaiah, begins when, two years after having been driven out by King Noah and his people for prophesying of their wickedness and resulting bondage (Mosiah 12:1), and having given them ample time to repent, Abinadi returns among the unrepentant people. After citing Isaiah, Abinadi begins the explanation of his message with an uplifted hand (Mosiah 16:1). David M. Calabro notes one important aspect of the gesture’s significance:

Here Abinadi switches from referring to the Lord in the third person to speaking on behalf of the Lord. Since this introduces God as the speaker, the speech following the outreached-hand gesture both proclaims the identity of the new participant (“the Lord”) and includes a prediction about the future (“It shall come to pass that this generation . . . shall be brought into bondage”). . . . It seems likely that there is an intended connection between Abinadi’s stretched-forth hands (v.1) and the Lord’s extended arms (v.12). It is as if Abinadi, through his own intensifying and pleading gesture of stretching forth the hands, is providing an illustration of the Lord’s extended arms of mercy.[12]

With this poignant gesture Abinadi prophesies that the Lord would “visit” Noah and his people “in their iniquities.”[13] Abinadi’s hand gesture is emblematic of the Lord’s hand being stretched out in judgment against Israel, as seen repeatedly in Isaiah: “for all this his anger is not turned away, but his hand is stretched out still.”[14] Abinadi has “prophesied evil” against Noah and his people (Mosiah 12:9, 29) for failing to repent and rely on the “arm of the Lord” to save.[15]

Abinadi’s quotation of Isaiah’s Suffering Servant poem begins with Isaiah 53:1.[16] Abinadi seems to have started here for strategic reasons.[17] For instance, Isaiah 53:1 invokes an important terminological connection with “report” and 52:7, namely the root *šmʿ is used in both. The “report” (šemûaʿ) alludes to the “reporter” or “proclaimer of peace” (mašmîaʿ šālôm) and the “reporter” or “proclaimer of salvation” (mašmîaʿ yěšûʿâ). By using Isaiah’s own language to recall the priest’s original question regarding Isaiah 52:7–10, Abinadi, in effect, garnered the attention of that very priest! The “peace” that Abinadi was reporting or proclaiming was the glad tidings of the Atonement, and the “salvation” (yěšûʿâ) that Abinadi was reporting was Jesus—Yēšûaʿ. Contrary to what Noah and his priests—including Alma at first—believed, “peace” (Isaiah 52:7; Mosiah 12:21) was not a covenant entitlement, but a covenant blessing predicated upon the law of covenant obedience (D&C 82:10; 130:18–21), i.e., “hearing” or hearkening (Deuteronomy 6:4).

When Abinadi turned to the text we know as Isaiah 53 he hoped to convince and touch the hearts of his audience and prove to them the truthfulness of his words and the reality of the Savior. He poignantly asked, “Who hath believed our report? And to whom is the arm of the Lord revealed?” (53:1; Mosiah 14:1). Abinadi clarified that Isaiah had posed this as a question to his audience, this evidently in connection to the content of Isaiah 52:7–15.[18] When King Noah and his priests attempted to get Abinadi to contradict himself and give them a pretext on which to get rid of him, Abinadi “answered them boldly, and withstood all their questions, yea, to their astonishment; for he did withstand them in all their questions, and did confound them in all their words” (Mosiah 12:19). In fact, Abinadi’s message filled Noah and his priests “with wonder and amazement, and with anger” (Mosiah 13:8), especially when Abinadi’s “face” or visage “shown with exceeding luster, even as Moses’ did while speaking in the mount of Sinai, while speaking with the Lord” (13:5). The Lord’s “arm” was truly being revealed “upon” Abinadi! At one point, “king Noah was about to release him, for he feared his word; for he feared that the judgments of God would come upon him” (17:11).

The “astonished,” “amazed,” and angry response echoes the description of the Suffering Servant that prefaces the poem of Isaiah 53 but is not directly quoted by Abinadi:

Behold, my servant shall deal prudently, he shall be exalted and extolled, and be very high. As many were astoni[shed] at thee; his visage was so marred more than any man, and his form more than the sons of men: So shall he sprinkle [JST, gather] many nations; the kings shall shut their mouths at him: for that which had not been told them shall they see; and that which they had not heard shall they consider. (Isaiah 52:13–15).[19]

But Abinadi and his visage were, in the end, also “marred” (cf. Mosiah 17:13–20). This suggests that the narrator (Mormon or his source) is depicting Abinadi as a type of “lesser” Suffering Servant— not one who dies to remit sins as the Savior does, but a prophet proclaiming the “peace” and “salvation” offered by the Lord Jesus Christ, “founder of peace”—rather than the “comfort” offered by Noah and his priests—who must suffer, like the greater Suffering Servant, and ultimately die for his message and testimony (see especially Mosiah 18:9 in light of Mosiah 12:20–24). In the end Abinadi, like the Savior Jesus Christ, was “exalted” and “very high” (Isaiah 52:13; 3 Nephi 20:43).[20] Although only one man, Alma, fully saw the Lord’s arm revealed and believed Abinadi’s “report,” that report would eventually “startle,”[21] “purify” (i.e., atone for?), or “gather” many nations, as it does today (see Isaiah 52:15; 3 Nephi 20:45).

The Making Bare of the Lord’s Arm

The image of the Lord’s “arm” being “made bare” (Isaiah 52:10; Mosiah 12:24), i.e., “revealed” (Isaiah 53:1; Mosiah 14:1), to which the inquiring priest alluded in Mosiah 12:20–24, is Abinadi’s scriptural proof that “salvation” did not come from the law, but that the “salvation of . . . God” or the “redemption of God” would be “seen” by all nations, and this in a person, not just the law. If this priest is Alma, we can begin to see why he draws so heavily upon these Isaian images in his later preaching and calls to repentance, as they had made such an impact on himself. Abinadi, after quoting Isaiah 53 in its entirety, would bring the discussion back to Isaiah 52:8–10 and the idea of “salvation” in 52:10, particularly in Mosiah 15:28–31 and 16:1, focusing on declaring and baring the arm of the Lord, and revealing his arm and salvation to the people.

The emergent symbol of the “arm” of the Lord that is “made bare” or “revealed” in Isaiah 52:10 (Mosiah 12:10); 53:1 (Mosiah 14:1) and Mosiah 15:31 (cf. 12:1; 16:1) is that of “salvation” by means of divine intervention. From the period of Israel’s exodus from Egypt, the “strong arm” became a symbol of the Lord’s “strength” and “salvation” (Exodus 15; Isaiah 12). The arm of the Lord to be revealed “is a metaphor of military power; it pictures the Lord as a warrior who bares his arm, takes up his weapon, and crushes his enemies (cf. 51:9–10; 63:5–6). But Israel had not seen the Lord’s military power at work in the servant.”[22] The implication here is that the “arm” to be revealed pertains to the Lord’s power to redeem, and in this case, crush his enemy, the adversary, and extend salvation to the repentant.[23] The phrase “arm of the Lord” (zĕrôaʿ Yhwh) seems to constitute a homonymous play on the word for seed (zeraʿ) mentioned in verse 10 and symbolizes the power of the Atonement to enable us to become the seed of Christ.[24] Along with the revelation that makes bare the arm of the Lord, the repentant sinner could also have their sins “covered” (atoned for) thanks to the sacrifice of the lamb.[25]

“Who Shall His Seed Be?”

Abinadi, by quoting the entirety of Isaiah 53:1 as a testimony of Christ and his redemption, implicitly includes himself among the “we” or “our” in “who hath believed our report?” But here we note another very intriguing aspect of the text. As implied above, the term “believed” (Mosiah 17:2) recalls the question, “who hath believed our report?” and “to whom has the arm of the Lord been revealed?” (mî heʾĕmîn lišmûʿâtēnû ûzĕrôaʿ Yhwh ʿal-mî niglâtâ? Isaiah 53:1 [Mosiah 14:1]). The phrase “to whom” in the Hebrew is ʿal-mî. This may be a significant datum in the context of Alma’s biography: he was the only one to “believe” Abinadi’s “report” about Christ and it was to him alone that the arm of the Lord was revealed at that time (see Mosiah 17:2; 26:15). The evident homophony between “Alma” and ʿal-mî might seem an astounding coincidence to some, but we suggest that its occurrence in this narrative context may instead be astoundingly deliberate on the part of Abinadi, for whom the recitation of this phrase would have been an opportune moment to turn his glance upon Alma (and perhaps also a deliberate inclusion on the part of a narrator who recognized the irony). Abinadi speaking directly to him a Hebrew phrase from Isaiah that sounds so close to the pronunciation of his own name may have pierced the soul of Alma as he heard both Isaiah’s and Abinadi’s “report.”[26] In the context of Abinadi’s prophetic testimony regarding the Redeemer, Alma comprehends a message that is not simply, “to whom is the arm of the Lord revealed?” (Isaiah 53:1; Mosiah 14:1) but also “The arm of the Lord, my (dear) Alma [ʿal-mî], has been revealed,” i.e., “the arm of the Lord has been revealed to—or upon—you!”[27] Alma was, by then, feeling the truth of Abinadi’s words and he “knew concerning [cf. Hebrew ʿal] the iniquity which Abinadi had testified against them [ʿalêhem]” (Mosiah 17:2). This was part of the revelatory process: having the “arm” or “salvation” of the Lord revealed to him as he “believed” in the words of Abinadi and was redeemed from his iniquity.

Thus in Abinadi’s quotation of Isaiah, Alma comprehends a message directed to him personally. In Isaiah 53:1 (Mosiah 14:1) we see potential lexical clues that perhaps suggest that the Lord was reaching out to him personally—extending the arm of his mercy and “salvation” toward and upon Alma. With the Lord’s “arm” (zĕrôaʿ) extended upon Alma (cf. Mosiah 16:1), Alma was being invited to “become” the Lord’s “seed” (zeraʿ) spoken of by Isaiah (Isaiah 53:10) and Abinadi (Mosiah 14–15), or one who “believed that the Lord would redeem his people” (Mosiah 15:10). Perhaps Abinadi knew Alma had been touched and sensed some sincerity in his earlier questions. Whatever the case, after hearing the content of Isaiah 53, as well as Abinadi’s expounding of it, we read of the result that Alma “believed” (Mosiah 17:2).

Abinadi fully understood the exegetical implications of the “righteous servant” having “seed”: he was a “father,” but because he was a “tender plant,” a “root out of dry ground” and a “man of sorrows” (Isaiah 53:2 [Mosiah 14:2]), he was also a scion, or a “son.” [28] In other words, he was both divine “Father” and “Son”: “because he dwelleth in flesh he shall be called the Son of God, and having subjected the flesh to the will of the Father, being the Father and the Son— The Father, because he was conceived by the power of God; and the Son, because of the flesh; thus becoming the Father and Son (Mosiah 15:2–3).[29] But Abinadi also understood the exegetical implications for the “seed,” namely that one—through the servant’s redemptive suffering—could become the “seed” of the one who became “the Father and the Son” (i.e. a giver of life and salvation). Abinadi further explains the concept of becoming the “seed” of Christ mentioned in Isaiah 53:10 (Mosiah 15:7–12), a process that eventuates from Christ’s intercessory offering of himself as a “guilt offering”:

And now I say unto you, who shall declare his generation? Behold, I say unto you, that when his soul has been made an offering for sin he shall see his seed. And now what say ye? And who shall be his seed? Behold I say unto you, that whosoever has heard the words of the prophets [i.e., their “report”], yea, all the holy prophets who have prophesied concerning the coming of the Lord—I say unto you, that all those who have hearkened unto their words, and believed that the Lord would redeem his people, and have looked forward to that day for a remission of their sins, I say unto you, that these are his seed, or they are the heirs of the kingdom of God. For these are they whose sins he has borne; these are they for whom he has died, to redeem them from their transgressions. And now, are they not his seed?

Through this process we are not directly subjected to the demands of justice if we will repent (D&C 19:15–20), but have an advocate with the Father who can stand betwixt us and justice, offering mercy as “with his stripes [ûbaḥăburātô, or, by his embrace/

All of this brings us back to the issue surrounding the performance of the law of Moses in Mosiah 13. The temple and the sacrificial system was a major component of that law, and represented the efforts of the repentant (or one wishing to make a vow with God), to bring forth an offering in similitude of the sacrifice of the Only Begotten Son of God. The pattern of the temple thus represented how one was enabled to live divine law, relying upon the merits of Christ,[32] and thus become worthy to enter into God’s presence. Moreover, all of this underscores the meaning and importance of becoming the “seed” of Christ, as he becomes the father of our salvation and reclaims us, and returns the repentant back to our Heavenly Father’s presence.[33]

Like natural progeneration, the preaching of the message of becoming the Lord’s seed perpetuates the process of others becoming the Lord’s seed, who then preach the same message.[34] Through Abinadi’s testimony-sealing death, another servant will have a testimony “sealed” upon him: Alma will experience a “mighty change of heart” and thus receive “the image of God engraven upon [his] countenance” (Alma 5:11–14). He will then continue to preach this same message of salvation through Christ, baptize and teach others of these truths (Mosiah 18:7–10), and eventually set up the Church of Christ, thus uniting the people and helping them become the seed of their Redeemer (Mosiah 18:16–21). When all is said and done, Abinadi preaches a masterful discourse that costs him his life, but saves countless others in the process. As with the Savior and his disciples, Abinadi’s legacy would live on after his death, beginning with Alma. Abinadi was a true disciple who had “become” the seed of Christ by becoming a Suffering Servant himself for the word (see below), with Alma and others soon following in his footsteps.[35]

Abinadi Following Christ as the Suffering Servant

After a full description of the life and suffering of our Savior, Jesus Christ, including his life as a tender plant arising out of dry ground, being despised and rejected, a man of sorrows, bearing our grief, bruised for our iniquities, stricken for our sins, Mosiah 14:10/

Since the Hebrew text uses Jehovah as the initial subject of the sentence (and this seems to be Abinadi’s own primary exegetical approach), we can view the passage in light of it as the will of Jehovah— or the will of Christ’s divine nature in pre-mortality—that he himself undergo the “crushing” and “grief” of Gethsemane, in order that he might come to know experientially[37] what he already knew cognitively.[38] From another perspective (and it should be noted that Abinadi himself does not completely exclude God our Heavenly Father from his interpretive picture),[39] if the reference has some bearing on God the Father, of course, it did not “please” our Heavenly Father to watch his Only-Begotten be beaten and scourged; it did not please him to watch his son faint under the load of carrying his cross to his crucifixion; and it certainly did not please him to watch his beloved son nailed to a cross.[40] The meaning of the word ḥāpēṣ/ḥēpeṣ (translated “pleased”) rather reflects that this was the “purpose” or “will” of Jehovah himself and his Father, so that they could bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of the children of our Heavenly Father by offering the blessing of the Atonement to be performed by his son, Jesus Christ. In fact, the text tells us the Savior will make a “guilt offering” or “trespass offering” on our behalf.[41] By claiming the blessings of that offering our guilt is taken away, transferred to Christ who heals us by extending the blessed, desired forgiveness, whereby we obtain peace—peace only available to the righteous through him.

It seems clear that Christ is the focus of Isaiah 53. It is possible, however, in light of Abinadi’s explanation of the chapter, that He also may have seen a reference to the Father, as well as the Son, in 53:10. Abinadi will immediately proclaim following his citation of Isaiah 53:

I would that ye should understand that God himself shall come down among the children of men, and shall redeem his people. And because he dwelleth in flesh he shall be called the Son of God, and having subjected the flesh to the will of the Father, being the Father and the Son—The Father, because he was conceived by the power of God; and the Son, because of the flesh; thus becoming the Father and Son—And they are one God, yea, the very Eternal Father of heaven and of earth. (Mosiah 15:1–14)

Abinadi evidently sees Christ as “the Father,” the Only-begotten of the Father who became our Redeemer through the mortal life, Atonement, death, and Resurrection he experienced—“the baptism with which [he] was baptized,” as the evangelist Mark quotes the Savior as saying (Mark 10:38; cf. Luke 12:50). Abinadi thus defines how Christ became like the Father and how we can become like him through repentance and emulating him. He was sent here by his Father, to do his will, and make us all “heirs of the kingdom of God” (Mosiah 15:11). It was thanks to Christ, who foresaw and knew what would be required of him to make us “his seed” that the will of the Father came to fruition as Christ became the Suffering Servant.[42] Once Alma was convinced by Abinadi’s testimony that Jesus was the “founder of peace, yea, even the Lord who has redeemed his people, yea, him who has granted salvation unto his people” (Mosiah 15:18), he not only “believed” (17:2; cf. especially 15:11), but he began to plead with King Noah that Abinadi “might depart in peace.” He himself became the messenger of “peace” that Abinadi had been, and that Jesus would be.

Pragmatics and Conclusion

Regarding Isaiah’s words in Isaiah 53:1 (Mosiah 14:1), Elder Bruce R. McConkie declared the following:

Some who are true and faithful will perish along with the wicked and ungodly in the days ahead. But what does it matter whether we live or die once we have found Christ and he has sealed us his? If we lay down our lives in the cause of truth and righteousness or in defense of our religion, our families, and our free institutions, why should we worry? We are not hanging on to life with greedy hands, fearful of the future. Once we have accepted the gospel and been reconciled to God through the mediation of Christ, what matters it if we are called to the realms of peace, there to await an inheritance in the resurrection of the just? Having a hope in Christ, we know we shall rise in glorious immortality and find place or “sit down with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the kingdom of God, to go no more out [Helaman 3:29]. Now, as Isaiah expressed it, “Who hath believed our report? and to whom is the arm of the Lord revealed?” (Isa. 53:1) Who will believe our words, and who will hear our message? Who will honor the name of Joseph Smith and accept the gospel restored through his instrumentality? We answer: the same people who would have believed the words of the Lord Jesus and the ancient Apostles and prophets had they lived in their day.[43]

Those who “believe” in the “salvation of the Lord,” i.e., the “secret” or “plan” (Hebrew sôd) of salvation as declared through the Lord’s servants the prophets (cf. Amos 3:7), can count on seeing the arm of the Lord revealed to them, whether in life or in death. If the saints are called to die, and they “die in the Lord” (D&C 63:49), “they shall not taste of death, for it shall be sweet unto them” (D&C 42:46). They shall at that time see the salvation of God. The themes of Isaiah 53 may have been preparing Abinadi for the fate which awaited him, and given him the courage to declare (when death was decreed upon him): “I will not recall the words which I have spoken… . . Yea, and I will suffer even until death, and I will not recall my words, and they shall stand as a testimony against you” (Mosiah 17:9–10).

Elder Dennis B. Neuenschwander offered the following reflection on Isaiah 53 to which Abinadi bore witness, and which is reflected in the life of Alma—the “one”:

Who better than the Savior can reach, support, and ultimately rescue the one among the crowd? He understands what it is to persevere among a disrespectful crowd and still remain true. The worldly crowds do not recognize Him, saying that “he hath no form nor comeliness” and that “there is no beauty that we should desire him.” King Benjamin says that the world “shall consider him a man.” Isaiah further describes Christ’s place among the crowds of the world with these words:

“He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief …; he was despised, and we esteemed him not.

“Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows: yet we did esteem him stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted.”

“Nephi writes that “the world, because of their iniquity, shall judge him to be a thing of naught.”

Yet ultimately this Firstborn Son of God, who is so often misjudged and misunderstood, will emerge from being one among the crowd as the Anointed One, the Savior and Redeemer of the world. This emergence is humbly predicted in the Savior’s own statement to certain chief priests and elders that “the stone which the builders rejected, the same is become the head of the corner.”[44]

Alma emerged from being “one among the crowd” and became a proclaimer of “peace” when he pled with Noah and his priests that Abinadi be allowed to “depart in peace” (Mosiah 17:2). But Alma also believed Abinadi’s message, and in consequence of this belief, the Lord’s Church would be established.[45] Alma’s response to Abinadi’s message demonstrates the power of Isaiah’s message. [46]

If we, like Alma, believe Abinadi, then Isaiah 53 is unquestionably about Christ, and his seed are those who take up their crosses and become justified and forgiven. And yet, Abinadi’s story shows that Isaiah 53 is also a kind of martyrs’ template for following Christ. Abinadi shows that to take up one’s cross and follow Christ is not merely a rhetorical platitude, and Abinadi, as Christ’s servant, would suffer and die like Christ, the Suffering Servant. John Welch writes:

Abinadi’s words and his blood stand as a testimony of this crucial declaration, for which Abinadi too went like a lamb to the slaughter. He also was innocent—another servant of the Lord who suffered death and was cut off from the land of the living. The Book of Mormon says nothing about Abinadi’s children or posterity, but his legacy or prophetic seed lived on in Alma and his converts. Abinadi was more than a witness in word alone; his life and death show that he also knew that meaning of Isaiah 53 from the inner workings of personal suffering and testing to the extreme.[47]

Alma too, as the Lord’s servant (Mosiah 26:20–24), will have to suffer as will those who believe his words (see Mosiah 18:3–11 and chapters 23–24).

To become the seed of Christ, is, in some measure, to become a Christlike figure and this will, of necessity, include suffering of some kind—an Abrahamic trial which requires one to “offer sacrifice in the similitude of the great sacrifice of the Son of God” and suffer “tribulation in the Redeemer’s name” (D&C 138:13). This is what Paul means when he refers to “the fellowship of [Christ’s] sufferings.”[48] And this is, in part, what it means to take upon us the name of Christ. Perhaps even in death, however, Abinadi took solace in the Lord’s words to Isaiah: “As for me, this is my covenant with them, saith the Lord; My spirit that is upon thee, and my words which I have put in thy mouth, shall not depart out of thy mouth, nor out of the mouth of thy seed, nor out of the mouth of thy seed’s seed, saith the Lord, from henceforth and forever” (Isaiah 59:21). We become the “children of the prophets” (Acts 3:25; 3 Nephi 20:25) or their “seed” and children of the covenant, when we hear and obey their words. Just as the Lord’s words were in Isaiah’s mouth, Isaiah’s words were in Abinadi’s mouth, Abinadi’s words were in Alma’s mouth, and Alma’s words were eventually in the mouths of his son and many others.

Thus, what began with Alma’s response to Abinadi’s use of Isaiah continued for many generations amongst the Nephites and Lamanites, and continues today as a discourse on the reality of the living Christ, and leads people to his redemptive power through the atonement. It teaches not only of his love, but of his power to claim us in his Father’s kingdom. If we too will believe the report, these Isaiah passages can inspire change and facilitate the transformation of soul that can enable us to become the seed of Christ, bask in the joy of that message, and declare the report to others as the message of the Suffering Servant evokes the atoning power of Christ to save us from sin and death. Truly, “how beautiful upon the mountains” this message and the feet of its messengers have become. “To whom” or “upon whom” (ʿal-mî) was “the arm of the Lord revealed?” Upon Alma! May we too believe the Lord’s servants so that the power of Christ may be revealed to us, and so that—in very real terms—the power of the Lord’s arm may be mercifully placed upon us, as he assists us in becoming his seed.

Notes

[1] Bruce R. McConkie has stated, “As our New Testament now stands, we find Matthew (Matt. 8:17), Philip (Acts 8:27–35), Paul (Rom. 4:25), and Peter (1 Pet. 2:24–25) all quoting, paraphrasing, enlarging upon, and applying to the Lord Jesus various of the verses in this great 53rd chapter of Isaiah. How many sermons have been preached, how many lessons have been taught, how many testimonies have been borne—both in ancient Israel and in the meridian of time—using the utterances of this chapter as the text, we can scarcely imagine.” Bruce R. McConkie, The Promised Messiah: The First Coming of Christ (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1978), 235.

[2] The intricacy with which the prophets wove Isaiah into these conversions consistently includes Isaiah 52:7ff and chapter 53. See, e.g., Alma the Younger’s story of repentance which echoes many of Isaiah’s themes (Alma 36:15–28). Additionally, John W. Welch believes that earlier Book of Mormon prophets such as Nephi and Jacob may also have drawn upon Isaiah 53 in their teaching. John W. Welch, “Isaiah 53, Mosiah 14, and the Book of Mormon,” in Isaiah in the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 305–6. The magnitude of these verses in the grand scheme of things cannot be overstated.

[3] Mosiah 13:33–35.

[4] The only two priests from the story ever mentioned by name are Alma and Amulon. Another example of this ambiguity followed by an explanatory reference occurs in Mosiah 10:22 where Zeniff conferred his kingdom “upon one of my sons,” and Mosiah 11:1, where we learn that the conferral was upon, “Noah, one of his sons.”

[5] See Mosiah 12:21; 18:30; and 27:36–37 for some of the language of Isaiah reflected in conversion stories.

[6] See D&C 130:20–21.

[7] To highlight the concept that Christ could have removed the suffering from the people if they would have listened and repented, it is probably not a coincidence that Mosiah 12 uses language that echoes Isaiah 53 as to how the Redeemer takes burdens upon himself in order to free and liberate us. Mosiah 12:2 describes the people who will be “smitten” (cf. Mosiah 14:4) and slain (Mosiah 14:8; see also 12:8), which Christ’s Atonement would require him to submit to; Mosiah 12:5 describes the people who would have burdens upon their backs (cf. Mosiah 14:4), which Christ again can help remove from the repentant soul; in Mosiah 12:8 we read that their abominations would be discovered (the arm of the Lord revealed /

[8] Cf. Isaiah 48:22 (1 Nephi 20:22); 57:21.

[9] Another key term in the exchange that follows is the word “salvation” (Hebrew yĕšûʿâ in the phrase yĕšûʿat ʾĕlōhēnû, 52:7,10) as connected with the Lord’s “arm”—an important theme throughout Isaiah (See especially Isaiah 33:2; 51:5; 52:10; 59:16; 63:5; cf. further the use of this theme in restoration scripture: Enos 1:13; Mosiah 12:24; 15:31; 3 Nephi 16:20; 20:35; D&C 90:10; 123:17; 133:3), and one to which Abinadi himself will return repeatedly (see, e.g., Mosiah 15:31; 16:12). King Noah, his priests, and his people will live to see Abinadi’s words “justified” or vindicated (cf. Isaiah 50:8 [2 Nephi 7:8]; Isaiah 53:11 [Mosiah 14:11]).

[10] Welch, “Isaiah 53, Mosiah 14 and the Book of Mormon,” 294, 299.

[11] See Dana M. Pike, “‘How Beautiful upon the Mountains’: The Imagery of Isaiah 52:7–10 and Its Occurrences in the Book of Mormon,” in Isaiah in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 264. Abinadi asserts that Christ is primarily to be understood as the deliverer of the message of good tidings.

[12] David M. Calabro, “‘Stretch Forth Thy Hand and Prophesy,’” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 21, no. 1 (2012): 48–49, 54.

[13] In the OT when the Lord “visits” his people it is often within the context of describing horrible consequences associated with sinners bringing upon themselves war (the sword), plagues, and the unpleasant circumstances that could have been averted had the people kept the commandments, repented, and followed God’s instruction. This is an interesting segue into the image of the “arm of the Lord”—a representation of his power; either in the form of judgment, or in the form of forgiveness.

[14] Isaiah 5:25; 9:12, 17, 21; 10:4 (2 Nephi 15:25; 19:12, 17, 21; 20:4).

[15] Compare Michaiah in the court of Ahab of Israel (1 Kings 22). Ahab’s chief complaint against Michaiah is that he will not rubberstamp Ahab’s evil acts and policies like the other prophets attached to the royal court, i.e., he will not tell Ahab what he wants to hear: “I hate him; for he doth not prophesy good concerning me, but evil” (v. 8); “And the king of Israel said unto Jehoshaphat, Did I not tell thee that he would prophesy no good concerning me, but evil?” (v. 18). See also Jeremiah 38, and the exchange between Jeremiah and Zedekiah’s court.

[16] For a discussion on the beginning of the text here versus Isaiah 52:13, see Welch, “Isaiah 53, Mosiah 14 and the Book of Mormon,” 295.

[17] Joseph M. Blenkinsopp writes: “The contextual isolation of 52:13–53:12 is also emphasized by the apostrophe to Zion that precedes and follows it (52: 1–2, 7–10; 54:1–17). If this arrangement is intentional, it may have had the purpose of relating the fate of the Servant to some of the major themes that permeate these chapters. The passage begins and concludes with an asseveration of Yahveh that the Servant, once humiliated and abused, will be exalted; once counted among criminals, will be in the company of the great and powerful (52:13–14a, 15; 53:11b–12). This statement encloses the body of the poem (53:1–11a), in which a co-religionist who had come to believe in the Servant’s mission and message, one who in all probability was a disciple, speaks about the origin and appearance of the Servant, the sufferings he endured, and his heroic and silent submission to death.” Joseph M. Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 40–55: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, AB 19A (New York: Doubleday, 2002), 349. As Victor L. Ludlow observes, “The servant to be revealed by the Lord’s power is not named, but both the prophet Abinadi and the evangelist Philip identify him as Jesus Christ (Mosiah 15; Acts 8:26–35) Additionally, Matthew, Peter, and Paul apply various verses of Isaiah 53 to Christ (Matt. 8:17; 1 Pet. 2:24–25; Romans 4:25). Modern apostles, such as James E. Talmage, Joseph Fielding Smith, and Bruce R. McConkie, have also stated that Jesus is the subject of Isaiah 53 (Jesus the Christ, p. 47; Doctrines of Salvation, 1:23–24; Premortal Messiah, pp. 234–35).” Victor L. Ludlow, Isaiah: Prophet, Seer, and Poet (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1982), 448. “The report is most naturally taken as the announcement that has just been made in 52:13–15.” The NET Bible First Edition Notes (Biblical Studies Press, 2006), entry for Isaiah 53:1.

[18] See Pike’s discussion of the Septuagint’s interpretive interpolations which describe the Messiah as the deliverer of the message. Pike, “‘How Beautiful upon the Mountains,’” 276.

[19] For a distribution of these passages in the Book of Mormon and other sources, see Pike, “‘How Beautiful upon the Mountains,” 249–91.

[20] “LXX has a stronger expression, ‘he will be greatly glorified,’ doxasthēsetai sphodra” Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 40–55, 346. δοξασθήσεται σφόδρα implies he will be gloried to the highest degree. “This piling up of synonyms emphasizes the degree of the servant’s coming exaltation.” The NET Bible First Edition Notes, entry for Isaiah 52:13.

[21] “Traditionally the verb יַזֶּה (yazzeh, a Hiphil stem) has been understood as a causative of נָזָה (nazah, “spurt, spatter”) and translated “sprinkle.” In this case the passage pictures the servant as a priest who “sprinkles” (or spiritually cleanses) the nations. Though the verb נָזָה does occur in the Hiphil with the meaning “sprinkle,” the usual interpretation is problematic. In all other instances where the object or person sprinkled is indicated, the verb is combined with a preposition. This is not the case in Isaiah 52:15, unless one takes the following עָלָיו (’alayv, “on him”) with the preceding line. But then one would have to emend the verb to a plural, make the nations the subject of the verb “sprinkle,” and take the servant as the object. Consequently some interpreters doubt the cultic idea of “sprinkling” is present here. Some emend the text; others propose a homonymic root meaning “spring, leap,” which in the Hiphil could mean “cause to leap, startle” and would fit the parallelism of the verse nicely.” The NET Bible First Edition Notes. The Joseph Smith Translation has “gather.”

[22] The NET Bible First Edition Notes, entry for Isaiah 52:15–53:1.

[23] All of these expressions draw on the ancient Israelite conception of Yahweh’s arm (zĕrôaʿ זְרוֹעַ) as an instrument of deliverance and judgment (a theme found throughout Deuteronomy, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and the Psalms). Isaiah’s use of the verb “reveal” *gly, which in the Niphal stem here denotes to “be made bare, revealed, uncovered,” constitutes a vivid example of the “revealing” or “unveiling” of the arm or hand of the Lord—the word “revelation” (revelatio, revelare < re + velum) literally means to draw back the veil (Psalm 44:3; 60:5; 108:6; 109:31; 138:7; see also especially Exodus 15:6, 9, 12, 17). Similarly, the saving “right hand” or “arm” is prominently featured in Israel’s temple hymns—the Psalms—making it a key motif in Israel’s temple worship. The revelation of the Lord’s hand or arm is emblematic of uncovering the knowledge of him who has power to kpr (“atone,” “cover” sins). In Mosiah 12:8 the unrepentant people are told after two years of ignoring Abinadi that their abominations will now be “discovered.” This did not have to be and Alma is now heading down a road of repentance, having his sins remitted by the healing power of the Suffering Servant of Christ, thanks to the preaching of his servant Abinadi. Alma will then become the preacher of truth following Abinadi’s martyrdom and will proclaim the same message of peace through the atonement as we find in Isaiah 53.

[24] It is noteworthy that in Mosiah 16:1, immediately after paraphrasing, quoting, then again paraphrasing Isaiah 52:10 (cf. Mosiah 12:24), that Abinadi stretches forth his hand(s) as a prophetic gesture. The Lord was “making bare” or “revealing” his “arm,” i.e., “declaring” his “salvation” through his authorized “servant” (see further below). But Abinadi has a further and perhaps more important point to make regarding the saving “arm” of the Lord. The “carnal and devilish” (Mosiah 16:3), he declares, have “gone according to their own carnal wills and desires; having never called upon the Lord while the arms of mercy were extended towards them, and they would not [i.e., they were unwilling to come to Christ]; they being warned of their iniquities and yet they would not depart from them [i.e., they were unwilling to depart from them] and they were commanded to repent and yet they would not repent” (Mosiah 16:12). The same arms or hands that are “extended” or “stretched out” in judgment (“for all this his anger is not turned away, but his hand is outstretched still”) are “spread out all the daylong” (Isaiah 65:3), i.e., or “he stretches forth his hands unto them all the day long” (Jacob 6:4). The language of the “outstretched” arm or hand of power is especially prominent in Deuteronomy (see Deuteronomy 4:34); 5:15; 7:19; 9:29; 11:2; 26:8; cf. 2 Chronicles 6:32). In Isaiah 53:1 (Mosiah 14:1), the Exodus image of the “arm” (zĕrôaʿ) becomes a symbol of the power of the atonement which makes us the “seed” of Christ (zeraʿ, Isaiah 53:10), “his sons and his daughters.” In other words, the aforementioned wordplay in Mosiah 14–17 that turns on the homophony of zĕrôaʿ (“arm”) and zeraʿ (“seed,” “posterity”) emphasizes that it is Christ’s “arms of mercy” that make us his “seed” or “posterity” on whom “power” (sometimes associated with priesthood and authorized servants and service) can rest eternally (cf. 2 Corinthians 12:9; D&C 39:12; 113:4). The image of the Lord’s extended arms in Mosiah 16:12 is a representation of the “divine embrace” that “consummates the final escape from death.” Hugh Nibley, “The Meaning of the Atonement,” in Approaching Zion, ed. Don E Norton, CWHN 9 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1989), 559–60. See also 2 Nephi 1:15; 2 Nephi 4:33–34 [quoting Jeremiah 17:5]; Jacob 6:5–6; Alma 5:33; 34:16; 3 Nephi 9:14; Mormon 1:15.

[25] The arm of the Lord (cf. Isaiah 51:9; 2 Nephi 8:9) can not only be equated with being encircled in the arms of his love (see previous note), but also serves as an instrument of deliverance and judgment. See for example, Deuteronomy 26:8; Psalm 79:11. The arm is salvation and does the work of saving or atoning (D&C 27:1–2). Thus, the “making bare” or “revelation” of the Lord’s arm, in an important sense, is having “salvation” declared, and received and understood through revelation.

[26] When all is said and done we do not have the original text, or even know with certainty what the dialect of Abinadi would have sounded like. We are taking Isaiah 53 as it occurs in the Hebrew Bible, working under the assumption that Abinadi’s recounting of the passage may have sounded similar enough so as to attract Alma’s attention.

[27] The preposition ʿal (עַל) properly denotes “upon” or “concerning” as opposed to simply “unto” (although it can take this meaning).

[28] Cf. the concept of the Davidic “scion” or “branch” in Isaiah 4:2 [2 Nephi 14:2]; Isaiah 11:1–9 [2 Nephi 21:1–9]; Jeremiah 23:5–6; Zechariah 3:8; 6:12.

[29] “How can Jesus Christ be both the Father and the Son? It really isn’t as complicated as it sounds. Though He is the Son of God, He is the head of the Church, which is the family of believers. When we are spiritually born again, we are adopted into His family. He becomes our Father or leader. . . . In no way does this doctrine denigrate the role of God the Father. Rather, we believe it enhances our understanding of the role of God the Son, our Savior, Jesus Christ. God our Heavenly Father is the Father of our spirits; we speak of God the Son as the Father of the righteous. He is regarded as the ‘Father’ because of the relationship between Him and those who accept His gospel, thereby becoming heirs of eternal life.” M. Russell Ballard, “Building Bridges of Understanding,” Ensign, June 1998, 66–67. For further explanation of how Christ is both the Father and the Son in these passages, see Joseph Fielding Smith, “The Fatherhood of Christ,” address to seminary and institute of religion personnel, Brigham Young University, July 17, 1962, 5–6; Paul Y. Hoskisson, “The Role of Christ as the Father in the Atonement,” in By Study and by Faith: Selections from the Religious Educator, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2009), 91–98; Jared T. Parker, “Abinadi on the Father and the Son: Interpretation and Application,” in Living the Book of Mormon: Abiding by Its Precepts, ed. Gaye Strathearn and Charles Swift (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2007), 136–50; and Robert L. Millet, “Jesus Christ, Fatherhood and Sonship of,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel Ludlow. (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 2:739–40.

[30] Cf. Margaret Barker, Risen Lord: The Jesus of History as the Christ of Faith (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1996), 128.

[31] See John 1:12; 1 John 1:3; Moroni 7:48; D&C 39:4; 45:8; 76:58.

[32] See especially 2 Nephi 2:8; 31:19; Alma 22:14; Helaman 14:13; Moroni 6:4.

[33] For a description of the relationship of Jesus as high priestly “servant” and sacrifice—which come together in Isaiah 53—in the Mosaic sacrificial system, see Hebrews 9:11–14, 24–26. Jesus became the great High Priest and entered into the holy place not made with hands, but into heaven (i.e. he fulfilled the law and everything it symbolized and pointed to). He is salvation in every sense of the word, and no man cometh unto the Father but by him (John 14:6). “For were it not for the redemption which he hath made for his people, which was prepared from the foundation of the world, I say unto you, were it not for this, all mankind must have perished. But behold, the bands of death shall be broken, and the Son reigneth, and hath power over the dead [i.e., his hand or arm over the dead]; therefore, he bringeth to pass the resurrection of the dead” (Mosiah 15:19–20, emphasis added). Because of his sacrifice, and the sacrificial system which pointed to him and the return of all of us to his father, this great type became a reality through his Atonement. “The seed of Christ are those who are adopted into his family, who by faith have become his sons and his daughters. (Mosiah 5:7.) They are the children of Christ in that they are his followers and disciples and keep his commandments (4 Nephi 1:7; Mormon 9:26; Moroni 7:19).” Bruce R. McConkie, Mormon Doctrine, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1966), 700. The divine destiny of the “seed” of Christ is to “become his sons and daughters” (Mosiah 5:7), “found at the right hand of God” (Mosiah 5:9), and “seal[ed] … his” (5:15). See Matthew L. Bowen, “Becoming Sons and Daughters at God's Right Hand: King Benjamin’s Rhetorical Wordplay on His Own Name,” Journal of Book of Mormon and Restoration Scripture 21, no. 2 (2012): 2–13. On Benjamin’s use of the expression “seal you his,” see further John Gee, “Book of Mormon Word Usage: ‘Seal You His,’” Insights 22, no. 1 (2002): 4.

[34] Blenkinsopp (Isaiah 40–55, 355) writes: “The Servant has died, or rather has been put to death, there is no doubt about that, yet we are now told that he will have descendants (zera’, literally, “seed”), his life span will be extended, he will see light and attain satisfaction, and (to return to the beginning of the passage) the undertaking in which he is involved will ultimately succeed. The most natural meaning is that the Servant’s project will be continued and carried to fruition through his disciples. Thus, Isa 59:21 is addressed to an individual possessed of Yahveh’s spirit and in whose mouth Yahveh’s words have been placed. He is a prophetic individual, in other words, who is assured that the spirit of prophecy will remain with him and with his “seed” (zera’) into the distant future.”

[35] Blenkinsopp (Isaiah 40–55, 356–57) further observes: “The usage therefore expresses a crucial duality between the people as the instrument of God’s purpose and a prophetic minority (the servants of Yahveh) owing allegiance to its martyred leader (the Servant) and his teachings. These disciples take over from the community the responsibility and the suffering inseparable from servanthood or instrumentality and, if this view of the matter is accepted, it is to one of these that we owe the tribute in 52:13–53:12.”

[36] This portion of the Hebrew text is extremely problematic, and it carries enormous theological ramifications that are, unfortunately, still unresolved from a scholarly perspective. The interpretative issues at hand revolve around the verb describing putting to “grief.” The word is a causative form and it seems that a direct object, which is missing, would be attached to the verb, and such is the case with the preceding verbal form which includes the object. Many scholars see the reading here as uncertain, or opine that an emendation is necessary. In the Dead Sea Scrolls, the scribe who transmitted this Isaiah passage did indeed supply the text with a direct object in efforts to try and explain who was doing what to whom in this verbal construction: 1QIsaa ויחללהו (“he pierced him”) in contrast to the Masoretic Text החלי (“he brought sicknesses [upon him],” “he made [him] suffer”). On the latter two readings, see Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 40–55, 346, 348 and Donald W. Parry, Harmonizing Isaiah: Combining Ancient Sources (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2001), 212, 280. The grammatical difficulties which arise here thus call for caution in attempting to limit the meaning of the subject and object in this portion of the verse.

[37] See Neal A. Maxwell, “Willing to Submit” in Conference Report, April 1985, 92; or Ensign, May 1985, 72–73.

[38] Isaiah 53:11 can be translated in several different ways. One possibility may highlight that it was Christ’s experience in Gethsemane that makes him the subject (and object) of verse 10 as the one who was grieved. 11 may be translated as something along the lines of, “out of the toil of his soul, he shall see; by means of his knowledge (presumably the knowledge he gained from Gethsemane), he shall be satisfied” (filled full—the will of the Father will be completed). The next phrase in the text calls him “righteous,” the result of this process. Orson Hyde said of Isaiah 53 that, “This particular prophecy speaks of Christ all the way through.” Orson Hyde, “The Marriage Relations,” in Journal of Discourses (Liverpool: Latter-day Saints' Book Depot, 1854–86), 2:75–87, October 6, 1854.). Todd B. Parker (“Abinadi: The Man and the Message (Part 1) and The Message and the Martyr (Part 2) [Transcript], FARMS Preliminary Reports (1996), 1–22, 1–22),argues in favor of viewing the subject of the verbs and doer of the action as Christ. See also Hoskisson, “The Role of Christ as the Father in the Atonement,” 91–98; Parker, “Abinadi on the Father and the Son,” 136–50; Millet, “Jesus Christ, Fatherhood and Sonship of,” 2:739–40.

[39] Abinadi’s statement that Christ can be called and was “the Father, because he was conceived by the power of God; and the Son, because of the flesh; thus becoming the Father and Son” is a theologically rich declaration. The term God in the phrase “power of God” can only refer to God the Father. Thus, Abinadi does not exclude God the Father from his exegesis of Isaiah 53. Clearly Jesus was not self-conceived. Even though Jesus was already in a sense “the Father” because he was in all things like God the Father in pre-mortality excepting mortal experience (i.e., the same level of experiential knowledge), it was still necessary for him to become the Father. This involved Jesus also becoming the Son with respect to the flesh. Through Jesus and his Atonement, we are offered the same opportunity: to become.

[40] Ludlow describes the Father in this verse who is not pleased to see his Son experience such things. Ludlow, Isaiah: Prophet, Seer, and Poet, 456. The grammatical issue discussed in note 36 thus becomes extremely significant in all of its theological ramifications.

[41] אָשָׁם [ʾāšām] means offense, guilt, or trespass-offering. The Messianic servant offers himself as an אשׁם in compensation for the sins of the people, interposing for them as their substitute Is 53:10. (Brown, F., Driver, S. R., & Briggs, C. A. (2000). Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon. Oak Harbor, WA: Logos Research Systems). Le 19:22 “And the priest shall make atonement for him with the ram of the guilt offering before the Lord for his sin that he has committed, and he shall be forgiven for the sin that he has committed.”

[42] Abinadi seems to further explain this conception of the will of the Father, and the Son’s submission to it, in Mosiah 15:1–8. The flesh becomes subject to the Spirit, or the Son to the Father, being one God, he suffereth himself to be mocked, scourged, and crucified, all as “the will of the Son being swallowed up in the will of the Father” (recalling that in Luke 22:42 the Savior cries out in Gethsemane for God, if he be willing, to remove the cup from him). If any human being ever had merited an answer to a prayer according to one’s own will (“the will of the Son,” human will, or the will of the child), it was the Savior on this occasion. However, divine will (“the will of the Father”) prevailed so that “God [could] break the bands of death, having gained victory over death; giving the Son power to make intercession for the children of men” (Mosiah 15:8). Thus, Christ, the literal Son of God in the flesh, became the giver of life, and became the Father of our salvation, and received all that the Father has (D&C 93:4). See also 3 Nephi 1:14, where just prior to his birth, Jesus explains this delicate relationship of the will of the Father and the Son which would be manifested at his birth and through his ministry.

[43] Bruce R. McConkie, “Who Hath Believed Our Report?,” Ensign, November 1981, 48.

[44] See Dennis B. Neuenschwander, “One Among the Crowd,” Ensign, May 2008, 101–3.

[45] Mosiah 25:19; 26:17; 27:13; Alma 1:28; 4:4; 5:2–3, 5; 6:1, 4, 8; Alma 8:1, 11; 15:13, 17; 16:15, 21; 19:35; 20:1; 23:4; 28:1; 29:11, 13; 45:22; 62:42; Helaman 6:3; 3 Nephi 5:12; cf. 3 Nephi 21:2.

[46] Blenkinsopp (Isaiah 40–55, 344) writes: “Isaiah 52:7–10 provides one of the best illustrations of the power of a canonical text to shape the identity of the community that accepts it. From this text early Christians derived both the unique form in which to tell the story of their founder—euaggelion, "good tidings, gospel" - and the essence of his message-the coming of the kingdom of God. Both come together in the first statement attributed to Jesus in Mark’s Gospel: “The time is fulfilled and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the [good tidings]” (Mark 1:15; cf. Matt 10:7–8 with echoes of Isa 52:3, and Luke 4:16-21 referring also to Isa 61:1–2). The messenger and the message in the Isaian text provided both paradigm and warranty for Christian preachers, as we see from the tendency to refer to it wherever the preaching of the gospel is the issue (e.g. Rom 10:15; Eph 6:15).”

[47] Welch, “Isaiah 53, Mosiah 14, and the Book of Mormon,” 310–11.

[48] See Philippians 3:10; see also 1 Corinthians 1:9; 10:16–17 (cf. 10:20); 2 Corinthians 8:4; 13:14; Ephesians 3:9 (cf. 5:11); Philippians 2:1.