The Impact of Centro Escolar Benemérito de las Americas, a Church School in Mexico

Barbara Morgan Gardner

Barbara E. Morgan, “The Impact of Centro Escolar Benemérito de las Americas, a Church School in Mexico,” Religious Educator 15, no. 1 (2014): 145–67.

Barbara E. Morgan (barbara_morgan@byu.edu) was an assistant professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this article was published.

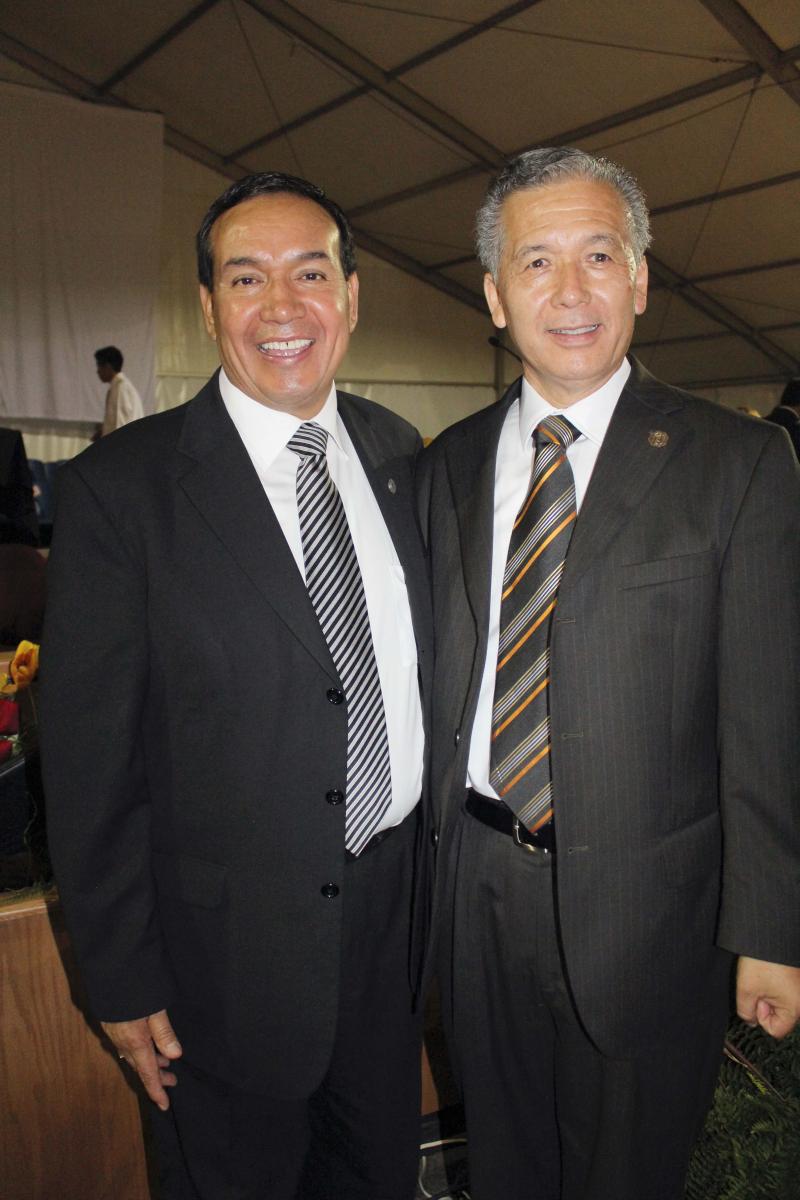

Photo courtesy of Barbara E. Morgan (Abraham Martinez (Seminaries and Institutes area director of Mexico and Area Seventy) and Alfredo Mirón (final director of Benemérito and Area Authority) following the final graduation ceremony at Benemérito. Both were students at Benemérito as youth.)

Photo courtesy of Barbara E. Morgan (Abraham Martinez (Seminaries and Institutes area director of Mexico and Area Seventy) and Alfredo Mirón (final director of Benemérito and Area Authority) following the final graduation ceremony at Benemérito. Both were students at Benemérito as youth.)

On January 29, 2013, Church leaders and administrators arrived at Benemérito de las Americas, the Church high school in Mexico City. These leaders included Elders Russell M. Nelson and Jeffrey R. Holland of the Quorum of the Twelve; Elder Paul V. Johnson, Commissioner of the Church Educational System and member of the First Quorum of the Seventy; Elder David F. Evans, Executive Director of the Missionary Department and member of the First Quorum of the Seventy; Bishop Gerald Caussé, first counselor in the Presiding Bishopric and member of the Missionary Executive Committee; Chad H. Webb, administrator of Seminaries and Institutes; Kelly I. Mills, director of international missionary training centers; and Carl B. Pratt, the newly called mission president of the Mexico Missionary Training Center, and his wife, Karen. There they met with the Mexico Area Presidency—Elder Daniel Johnson, Elder Benjamín de Hoyos, and Elder Jose Luis Alonso—along with Abraham Martinez, the CES area director, and Alfredo Mirón, the school’s director, all five being natives of Mexico. Faculty, parents, more than 2,000 high school students on campus, and thousands of alumni throughout Mexico viewed this historic event via satellite. The purpose of this momentous meeting was to announce the closure of Benemérito de las Americas as a high school—and the transitioning of the campus for the opening of a Missionary Training Center at the end of the 2013 school year.

School motto at the entrance of the Benemérito campus with the "B" painted on the hill in the background. The sign read "Intelligence, power, light and truth." The sign now reads "Centro de Capacitación Misional, Mexico" (Missionary Training Center, Mexico). Photo courtesy of Barbara E. Morgan

School motto at the entrance of the Benemérito campus with the "B" painted on the hill in the background. The sign read "Intelligence, power, light and truth." The sign now reads "Centro de Capacitación Misional, Mexico" (Missionary Training Center, Mexico). Photo courtesy of Barbara E. Morgan

The result? Most members of the Church in the United States and other parts of the world now knew that the Church owned a high school in Mexico. Benemérito, a major high school in Mexico City that operated for over forty-nine years with a total enrollment of nearly 23,000 students, would graduate its last senior class of approximately 650 students. The nearly 1,600 students not graduating would return home to find and enroll in a high school near their own homes throughout Mexico, giving their seat up, as Elder Holland taught them, “so that a missionary could take it and help in the conversion of thousands.” [1] This announcement raised many questions. Why did the Church have a school in Mexico? Who were the faculty and students involved in this school? What was life on campus like? What has been its impact on individuals, families, the Church, and Mexico? A review of historical documents and interviews with participants help to answer these questions.

Why Church Schools in Mexico?

Following World War II, the Church expanded dramatically in a number of important ways. In fact, during the nineteen-year tenure of President David O. McKay, from 1951 to 1970, total membership of the Church went from 1.1 to 2.9 million. In 1950, 87 percent of the total membership of the Church lived in North America. As the Church expanded worldwide, educational needs—especially those in the international areas—became more pronounced. No prophet in this dispensation up to that time had more experience with the international Church and education than did President McKay. In 1921, Elder McKay took a yearlong world tour of the Church’s missions, which took him to more locations and made him the most traveled Church leader up to that time. [2] Professionally, he was an educator, which carried into his ecclesiastical assignments, including general Sunday School superintendent and Commissioner of Education for Church Schools. [3] For President McKay, the international growth of the Church meant international focus on Church education. The worldwide growth of the seminary and institute programs, which enabled thousands more students to be reached primarily through early morning and home-school programs, was among his top priorities. In addition, areas of substantial Church growth where public education was inadequate, such as the Pacific islands and Latin America, also received major attention. At the beginning of his tenure, the Church opened the Church College of Hawaii as well as high schools and several elementary schools in the Pacific. The expansion of Church schools in Latin America, focused primarily in Mexico, also came as a result of the growth of the Church and lack of educational resources there. [4]

During President McKay’s tenure as prophet, Church membership in Mexico grew from less than 8,000 in 1950 to over 60,000 in 1970. [5] Although the Church in Mexico was first established in 1885 as a place of refuge for the early Saints to practice plural marriage, it was more than a half century later before the Church began its dramatic growth in membership. Although the Mormon colonies of northern Mexico had a small system of schools, the first Church school for native Mexicans started further south, in the village of San Marcos, just north of Mexico City. [6] As early as 1915, local members and leaders began requesting Salt Lake to fund Church schools to meet the needs of the growing membership. By the 1930s faithful Hispanic LDS teachers were hired by local members to teach their children. In 1944, a formal application to the Church leaders was made by Mexican ecclesiastical leaders to incorporate the school at San Marcos into the Church’s education system. By the 1950s students living throughout Mexico who were unable to receive adequate education in their home town, were sent to the LDS colonies for educational opportunities available there. [7]

With the growth of the Church in Mexico and continued requests for educational assistance from members and leaders in Mexico, President McKay formed a committee in 1957 to assess the educational situation in Mexico and provide recommendations for action. He named Elder Marion G. Romney of the Quorum of the Twelve as director of the committee, with Joseph T. Bentley, president of the Northern Mexican Mission, and Claudius Bowman as members. [8] After completing a two year extensive assessment, the committee reported that the “Mexican government was having difficulty providing education facilities for its people.” They continued, “In 1950 some nine million Mexicans over six years of age could neither read nor write.” They found that the illiteracy rate was rising, “because the increase in population is greater than the advances in education.” They further explained, “The Federal Department of Education indicated that it was in desperate need of more schools, particularly in the urban areas. Private schools are encouraged, especially on the elementary school level.” [9]

As a result, in 1959, the committee recommended building twelve to fifteen elementary schools, taught by members of the Church and establishing an educational and cultural center just north of Mexico City that would include a primaria (elementary), secundaria (junior high), preparatoria (high school), and a normal (teacher preparation) school. They indicated that “this could well form the nucleus of a center not only for Mexico, but for all the Latin American missions.” They continued: “We have a great work yet to do in these lands . . . developing programs around the native cultures. Stories and illustrations for Mexico should be taken from Mexican history and from the lives of Mexican heroes such as Benito Juárez and Miguel Hidalgo. Our M.I.A. [Mutual Improvement Association] activities should feature Indian and Mexican dances, folklore, and music.” [10]

Students in the library at Benemérito. This library now serves as the welcoming center for the new Missionary Training Center in Mexico City. Photo courtesy of Esli Hernandez.

Students in the library at Benemérito. This library now serves as the welcoming center for the new Missionary Training Center in Mexico City. Photo courtesy of Esli Hernandez.

Within one year of the report, the Church opened thirteen elementary schools, with at least fourteen more in the planning stage. By 1962, as these elementary students reached eligibility for graduation, the need for secondary schools became evident. Not only was the Church Educational System lacking secondary schools, with three being planned and only one in existence in the colonies, but the entire country of Mexico had a major shortage of secondary schools. In fact, on September 1, 1962, Adolfo Lopez Mateo, president of Mexico, stressed the need for secondary schools in his message to the nation and called on anyone who could offer a solution to help. “The educational effort does not fall exclusively upon the State,” he pled in his speech to the nation. “Within the means of your possibilities, the patriotism of all citizens should participate in this great work.” [11] Using this statement by Mexico’s president along with his needs assessment, Daniel Taylor, the superintendent of Church education in Mexico, requested the immediate building of secondary schools in Mexico. [12]

Launching the New School: Hiring Teachers and Enrolling Students

Less than a year after this request, Church leaders created a master building plan based on the projection of three thousand students in four different schools: an elementary school for children living nearby, and secondary, preparatory, and normal schools with boarding facilities available for students living a distance from the school. By August 1963, a 247-acre lot in Mexico City known as “Rancho El Arbolillo” was found and purchased, with 60 acres set aside immediately for educational facilities. In November of that same year, the groundbreaking ceremony was held. In the groundbreaking ceremony, “Benemérito de las Americas [13]” was announced as the school name, giving homage to Benito Juárez, the Abraham Lincoln of Latin America. In his groundbreaking talk, Elder Romney emphasized the love he had for his native Mexico and prophesied that the school would become a “great Spanish-speaking cultural center.” He added, “Its influence will reach far beyond the valley of Mexico. . . . It will be felt in all of Latin America, including South America. Hundreds of thousands of people will come here.” He prophesied, “Going out from here, they will help the Nation build up its education, its culture and its spirituality. This school will prepare men for a better future here on the earth, and for eternal life in the world to come.” [14]

With only four months between the groundbreaking and school starting, major work still needed to be done. Buildings needed to be built, curriculum needed to be determined, students needed to be invited, and, of great urgency, teachers needed to be hired. When planning the schools, President McKay was asked where he was going to find an adequate number of qualified teachers. After a short pause he replied, “You go ahead and organize the schools and the Lord will provide the teachers.” [15]

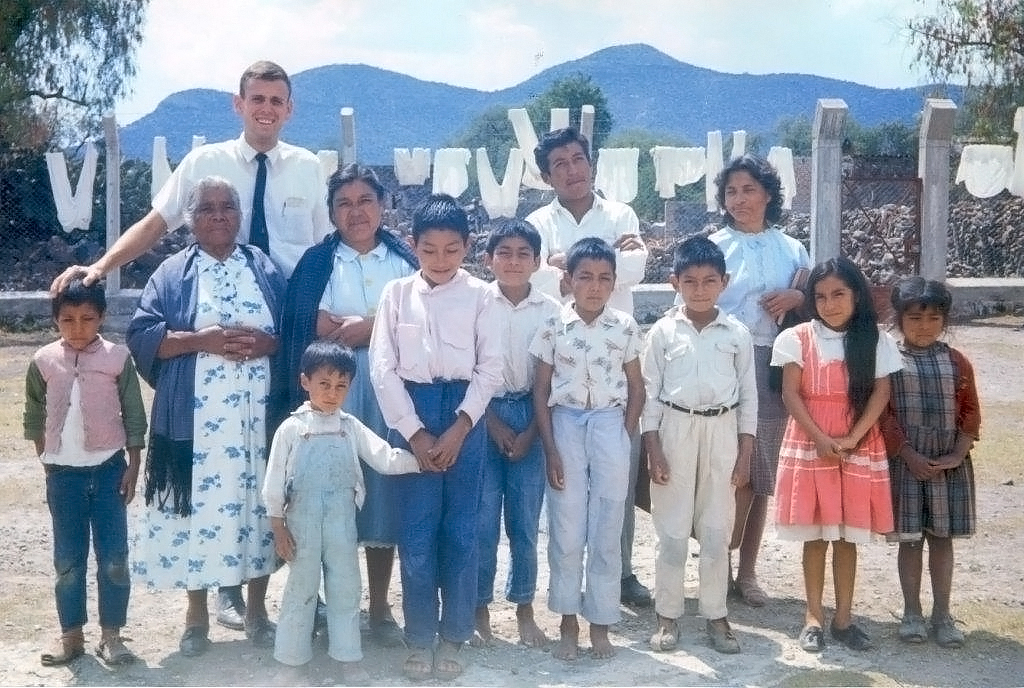

Baptism of Abraham Martinez and his family in the late 1960s. Martinez was raised by his grandmother and sent to Benemérito shortly after his baptism. There he had his first hot shower and three meals a day. Abraham Martinez would later serve as a bishop, stake president , mission president, and Area Seventy. He also later taught at Benemérito. Used by permission of Abraham Martinez

Baptism of Abraham Martinez and his family in the late 1960s. Martinez was raised by his grandmother and sent to Benemérito shortly after his baptism. There he had his first hot shower and three meals a day. Abraham Martinez would later serve as a bishop, stake president , mission president, and Area Seventy. He also later taught at Benemérito. Used by permission of Abraham Martinez

About this time, Efrain Villalobos, a Brigham Young University agronomy student, returned to his home in San Marcos for Christmas vacation. He heard about the Church school being constructed only a half hour from his home and, being curious, went with his brother to see what was going on. After looking around for a while, they were leaving when a man waved them down and told Efrain that Professor Wagner, the director of the school whom he had met briefly in the colonies a few years previously, urgently wanted to see him. Without hesitation Wagner announced, “Efrain, I want you to be in charge of teacher education at this secondary school. We start classes this February [1964].” This caught Efrain totally by surprise. “No, Brother Wagner,” he cried, “do not ask this favor of me. There are three things that I never want to be in my life: a chef, a stake president, and a schoolteacher.” With a look of concern on his face, Kenyon Wagner replied firmly, “I have a serious problem. I have not been able to obtain the necessary teachers that are required in order for us to run this school. It is a blessing that you accepted the invitation to come to my house today. Look, Efrain,” he continued, “you have in front of you an exceptional opportunity to serve the youth of the Church, and I invite you to be a part of this grand experience.”

For a moment Efrain was unable to speak. After asking the director when he needed to know, Wagner replied, “Right now.” Efrain replied that he could only commit for one year. Wagner assured him that would be fine, and they would await his return. [16] In February Efrain returned to Mexico City, where he was immediately assigned to be the first “dorm parent” with his wife, Olivia, as the school’s first teacher of agronomy, and he was appointed administrative assistant over teacher development. Efrain would be at the school for over four decades.

Another potential teacher, Jorge Rojas, a good friend of Kenyon Wagner’s from the Mormon colonies, was studying at New Mexico State University when he received a phone call. “Jorge,” Wagner said, “the Church is opening up a new school in Mexico City, and I need your help to teach English and physical education.” Jorge responded that he would love to as soon as he finished his last year of college and served a full-time mission. Wagner quickly retorted, “You stay where you are, and in fifteen minutes I’ll call you back.” This time President Ara Call, the president of the northern Mexican Mission, called Jorge fifteen minutes later. “I’m calling you on a mission for the Church at Benemérito,” he proclaimed. “It is opening in six months, and that is when your mission will start.” Jorge finished off the semester and in February commenced teaching English and coaching basketball as a full-time set-apart missionary.

Irma Soto had been studying biology at a local university when she met the Mormon missionaries and was converted. Knowing that her parents were staunch Catholics, she decided to wait until after she was baptized to tell her parents. Upon learning that Irma was baptized, her mother, enraged, drenched her with a pail of pig slop and yelled, “Now you have not only been baptized by the Mormons, but by your own mother,” and then demanded that she leave their home. Only a few days later, and just a few weeks after her baptism, Kenyon Wagner invited Irma to be the first biology teacher at Benemérito, a position she gratefully accepted.

Efrain, Jorge, and Irma’s experiences were similar to that of many other teachers, employees, and students who attended Benemérito. Reflecting on those first teachers, employees, and students in his personal journal, Kenyon Wagner, the first director of the school, compared them to the first pioneers of the Church. “I have the firm conviction that God chose this first generation of teachers, the employees, and the students, to play an integral role in the beginning of this school. Through everyone’s great strengths,” he continued, “we will overcome and be capable of resolving major problems. The faith that I have seen among them is very impressive.” [17] During the next few years, major problems were encountered and resolved, including handling the first death of a student, receiving unprecedented government permission to run a normal school, and obtaining water rights for the campus after much fasting and prayer.

Before school started, Efrain, Jorge, and Irma, with twelve other teachers who had little or no experience in adolescent psychology or pedagogy, and some of whom had recently joined the Church, received their first official training as teachers. Daniel Taylor, the superintendent of Church Schools for Mexico, enumerated the goals of the school. He expressed his desire that Benemérito would give the students a better education than any other school, that the students would consider their opportunity to work as a privilege to learn, that all students would be equal, that the teachers and home supervisors should consider the students as younger brothers and sisters, that both scholastic and religious education were important and time and effort should be given to each, and finally, and that all who studied or worked there “should at all times live as faithful members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.” [18] Even though they were trying to become expert in their own fields, these teachers recognized that “the most important area of competence was that of being an authentic disciple of Jesus Christ.” Efrain soon recognized that “in the process of trying to reach this goal myself, I was more capable of inspiring my students both academically as well as spiritually.” [19]

With the first generation of faculty and employees hired, teachers and leaders welcomed the first 125 secondary students from all over Mexico on February 17, 1964. One large room was used for the dual purpose of a classroom for all the students and sleeping quarters for the young men. The young women all shared one small cottage for the first week, with another cottage being built each week for seven weeks. Although the living standards were Spartan, with no running water, it was better than the majority of the students had experienced up to this point in their lives. Wagner estimated that “ninety percent of the students came from poor families and only ten percent came from homes which would be considered middle class.” [20] Many of these students who came to the school had never previously slept in a bed, or owned a pair of pajamas, and some showed signs of malnutrition.

Abraham Martinez, for example, having been abandoned by his mother, planned on dropping out of school and working after completing elementary school because there was no secondary school to attend in his area. “Fortunately, my grandmother, who raised me, made many sacrifices and helped me be able to attend Benemérito.” Abraham lived on campus, where, for the first time, he “took a shower every day and ate three meals.” [21] One student’s clothes were so ragged his bare skin could be seen. He had no underwear and no change of clothing when he arrived. [22] Another student, Miguel Velez Adame, admitted that he and his friends “were baptized just to take advantage of this unique opportunity, the only opportunity we had to receive an education.” [23] Alfredo Mirón, one of the first students to enroll, had watched his father get drunk and abuse his mother and siblings and was raised in complete poverty for years. He decided that he would raise a family very different than his own. After meeting the Mormon missionaries, he joined the Church and, with his mother, embarked on an overnight bus trip to Benemérito. After sleeping there for a night, his mother woke him up and said as she left, “Son, here you will stay. Everything in your future now depends on you.” For the next three years, Alfredo worked in various jobs at the school, returning home only once a year to visit his family. [24]

Student Life

At the school’s inception, Church leaders were anxious to educate these young, mostly poor members, but did not desire to hand out a dole, thus making them dependent on the Church. “We firmly believe,” they stated, “that these young men and women should earn their own way as far as possible so that they do not get the idea of having everything given to them.” [25] In fact, one of the key positive factors in buying the land for the school was the fact that there was a farm on the property. Daniel Taylor wrote in his explanation for the proposed purchase of the land to the Church Board of Education, “My attraction is based principally upon my awareness of the fact that our members are very poor.” He continued, “If they are to attend our high school and junior college they will need to have projects on which they can work in order to earn their way. Simultaneously it would provide the dormitories with much that they would need in order to feed the students.” [26] When Benemérito first started, all students were required to work and were given a variety of assignments. These students worked on the farm, in the physical plant, in the cafeteria, and in janitorial positions. They worked as secretaries, gardeners, phone operators, assistant coaches, and a variety of other jobs. For most students work was necessary for them to be able to afford schooling. These jobs also gave these students a great work ethic and provided many other skills that they could use to become self-reliant in their later lives.

Jesus Flores, for example, was the oldest of five. Because of the poverty of his family, education was not a possibility for Jesus until he became aware of Benemérito. With no extra money beyond the bus fare, Jesus, at age twelve, left his family and enrolled at Benemérito. He explained with great emotion, “Here, I learned how to use a fork, slept in a bed for the first time, and learned how to flush a toilet.” Jesus was immediately given a job. “I worked all year for six years, in the garden, in the classroom, but primarily on the farm. With the money I earned I paid for my own schooling, my own clothes, and was able to earn enough money to go home [only] during the long vacation.” Many times when other students were going home, Jesus stayed and worked. “This allowed me to save enough money to pay for my sister to come here so that she could work and go to school.” Before he left for his mission, Jesus was able to bring all of his siblings to Benemérito. “The Church never gave me money; the Church gave me opportunity,” he reflected. “The Church didn’t just help us; they did something much better; they gave us the ability to help ourselves; they gave us the opportunity to work, to become self-reliant.” [27]

Over the years the opportunity to work at Benemérito was reduced. When the school first started, all students were required to work on campus, and there was plenty of work as the students helped with constructing the new buildings, working on the farm, planting trees, and so forth. With fewer needs and hired workers doing more tasks on campus, in later years only about 25 percent of students could be employed. Thus, unlike earlier years, some students could not afford to attend Benemérito because there were not enough jobs to enable them to pay their own way.

Although fewer students were working on campus, they became involved in other ways. The Mexican government required all students to be involved in some type of extracurricular activity, so a variety of activities were made available to these students throughout the years. [28] Some of these clubs and activities include drama, carpentry, glass etching, electrical repair, driving lessons, making electrical and stuffed toys, wood burning, conversational English, embroidery and crochet, art, chorus, dancing, journalism, piano, orchestra, band, as well as sports teams including basketball, football, soccer, and track and field. The school also held other activities, including painting the B annually on a nearby mountainside, school dances, anniversary programs, Model United Nations, missionary week, culture week, student leadership, seminary activities, and graduation. Benemérito’s dance and sports teams were known throughout Mexico and were recognized by other government and private schools in the area for their talent. In fact, other schools decided not to play sports on Sunday so that Benemérito could participate, regarding the school’s involvement as essential to the quality of their league. [29]

Participation in extracurricular activities was a new experience for many of these students, especially those raised in poverty where athletics and culture were luxuries could not be afforded. “Because I didn’t have time to participate in activities as a child,” one student observed, “when I got to school I didn’t know how to play sports.” Speaking of the influence of his coach he continued, “I learned much about football, but more about life.” [30]

One young woman, Marcela Burgos, reflected what she gained from participation in sports. “We had an incredible coach who woke us up and had us practicing by 6:00 am. . . . I learned that success was not free, but only came after much sacrifice. Strict discipline governed everything. Punctuality was critical, we needed to practice to the limit of our strength, and never accept mediocrity.” These extracurricular activities not only benefited the individual, she continued, but also brought great “fame, respect, and trust to the Church.” [31]

Perhaps one of the most widely known extracurricular activities since it officially began in 1972 was the folk dance group, which performed throughout Mexico and the United States, becoming ambassadors for the school and Church. At the conclusion of the program as the performers sang “I Am a Child of God” and “We’ll Bring the World His Truth,” audiences often felt a special spirit and inquired about the school and its sponsoring Church. “The youth understood that they were missionaries,” explained Guadalupe Lopez Duran, who taught dance at Benemérito for nearly forty years. “They carry a message through dance, art and music. We testify of the Church as we perform.” [32] Over the decades, it has become more common for schools in Mexico to provide better and wider variety of extracurricular activities. Benemérito, however, is still remembered for its expansive and excellent extracurricular activities. In fact, for many students, participation in these activities drew them to Benemérito.

The school fulfilled curriculum requirements specified by the Mexican government. For the secondary level, all students were required to take Spanish, math, physics, chemistry, English, geography, world history, Mexican history, and biology for all three years. In addition, art, physical education, technology, and contemporary history were required at some point during their schooling. At Benemérito, an additional course was also required: seminary. These two entities with their specific curriculum formed the vision statement of the school: “To be a model of spiritual strength and educational excellence.” [33] Since the school’s inception, seminary and Church attendance were mandatory. Two years following the opening of the school, a seminary building and a chapel were built on campus. Due to Mexican law, which forbade “holding classes in religion or religious meetings of any kind, in buildings used for school purposes,” a concrete wall separated the seminary building from the rest of campus. This wall was recently been removed, however, because of the increased flexibility of Mexican laws. [34]

As enrollment on campus increased, student wards were created under the direction of local bishops, many of whom were teachers, “dorm fathers,” or employees of Benemérito. These student wards eventually formed a campus stake, the Zarahemla Stake. Auxiliary leaders were also drawn from Benemérito employees, but the students themselves held the majority of the callings, performed the ordinances, gave the talks, offered the prayers and taught the classes. This stake and these wards were unique in all the Church because they served high school rather than college students.

Many students credit seminary and Church activity as the most beneficial experiences in their schooling years. Miguel Velez Adame, the student previously mentioned who joined the Church in order to have the opportunity to receive an education explained, “When I left I was scared, had many doubts, and was so homesick. I had never left my pueblo. I don’t know how often I cried and how many tears I shed as I began this major change in my life.” His spiritual conversion began when he found a new spiritual home on campus. “I will never forget the peace I felt as I walked into sacrament meeting and the congregation was singing ‘Oh hablemos con tiernos ascentos’ [Let us oft speak kind words to each other]. In this moment I felt an indescribable peace. Then they sang ‘Asombro me da’ [I stand all amazed], I felt a sensation in my chest that is difficult to explain. The next morning I woke up for family prayer and scripture study, I attended seminary, and that night, we had family home evening.” He continued, “I remember the lessons from my seminary teachers, but more important was their example, their spirituality, and their testimonies.” [35]

In addition to the influence of the seminary and ecclesiastical leaders, many students at Benemérito attributed their spiritual growth to their “foster parents and families.” Due to the young, impressionable age and circumstances of these students, Church school administrators suggested the construction of small cottages, in which the students would live in a family type environment where “foster parents” would watch over, train, and provide an example of righteous LDS living. [36] For many, Benemérito was more than a boarding school; it was their home; it literally offered them the only family they had. In fact, of the first generation of students, the director reported that 60 percent were “abandoned by their parents, or by one parent; or come from homes broken by divorce.” [37]

Having lost his mother to death and being abandoned by his father, Jesus Gordillo became the provider of his family at the age of eleven. One day, as he was walking the streets as a “young vagabond” in Mexico City, a bus drove by him with a sign that read “Sociedad Educativa Y Cultural.” “I saw the students and noted how clean they were. I couldn’t imagine ever having the opportunity to go there.” Jesus and his brothers eventually ended up in an orphanage where he was invited to stay until he turned fifteen. Just prior to his fifteenth birthday, the director of the orphanage introduced him to the Lopez family. She explained that this family was interested in taking him home, where they would provide him with an education. Having no other family and no other plans, Jesus accepted the invitation, and was taken to their home where they were “foster parents” of one of the cottages. There he would live until he graduated from high school. “In the school song there is a line, ‘en la escuela un hogar encontré’ (in the school I found a home). It seemed as though this line was written just for me.” [38]

The impact of Benemérito on future families is a common theme. They saw ideal family life modeled by their cottage supervisors, were taught the importance of creating eternal families, and many of them even met their future spouses on campus. While playing soccer in the field close to Benemérito, Arturo Limon was asked by Kenyon Wagner where he was attending school. When Arturo replied that he was not going to school, Kenyon said that he had the perfect school for him, and if Arturo desired, he would help him get in. A few years after attending Benemérito, Arturo was baptized. “I was introduced to a new lifestyle. I gained a new identity. I was taught to be a leader and learned what a family could be like.” Arturo’s future wife also attended Benemérito. After both returned home from their missions, they started dating seriously and traveled to Provo, Utah, where they were married in the temple. “We now have four children, two of whom have served missions,” he enthusiastically shared. “We were able to teach our own children, as parents who had been taught at Benemérito. It’s a great sequence. What we learned from Benemérito we used to raise our own family as pioneers in Mexico!” [39] Kenyon Wagner, speaking of the first generation of students and teachers, wrote simply in his journal, “They have become members of my own family and I love them as such.” [40]

When the school first started, about 25 percent of the students were not Latter-day Saints. As the school became more prestigious in academics and extracurricular activities, many government officials started sending their children there. With the increased acclaim of the school, came positive advertising for the Church. One graduate from a Mexico City suburb insisted, “The missionaries were very important in my home town of Chalco, but the greatest missionary tool was Benemérito. People in my town heard about this great school, with clean kids, and good teachers.” She reflected, “When I was a child, my town had only a branch. Now the same town has three stakes. It is commonly understood among us that this happened because of the influence of Benemérito.” [41]

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland and a translator speaking at the meeting held on January 29, 2013, announcing the conversion of Centro Escolar Benemérito de las Americas into the second-largest missionary training center in the world. Photo by Esli Hernandez

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland and a translator speaking at the meeting held on January 29, 2013, announcing the conversion of Centro Escolar Benemérito de las Americas into the second-largest missionary training center in the world. Photo by Esli Hernandez

Leona Wagner, wife of the director, knew the importance of sharing the gospel and held many missionaries discussions in her home. Many students recalled that if they were not faithful worthy members of the Church, she worked with them until they were. This emphasis on missionary work spread across campus. Every year, through the seminary program, students participated in missionary week, where they dressed up and acted like full-time missionaries. During this week they would receive missionary training, role-play by giving missionary discussions to other students, and attend missionary firesides conducted by a stake president or area leaders.

One of the common occurrences at graduation is for the leading authority to have the students raise their hand to indicate the number who have turned their mission papers in or who had received their mission calls. The response from the students is electrifying as so many have already received calls and so many are anticipating calls in the near future. In January 1999, Church leaders approved eighteen-year-olds, who had graduated from high school in Mexico, to be called as full-time missionaries. Over five hundred eighteen-year-old young men have been called to serve from Mexico each year since. [42] During the last ten years, approximately 85 percent of all male Benemérito graduates have served full time missions. [43] Elder Nelson, who chairs both the Board of Education and the Missionary Executive Committee, acknowledged that it was the success of these younger Mexican missionaries that led to the lowering of the missionary age for elders and sisters throughout the whole Church. “Thanks to these Mexican elders, they helped pioneer this change in age.” [44]

By Their Fruits: Impact

Elder Romney told the first graduating class that they should be the great pioneers of a great movement, “not only in secular education, but to bring the light of the gospel to the people of this great country.” He encouraged them to reach for the highest peaks and promised them the blessings of the Lord as they worked towards their goals. He invited them to give service to themselves, their families and their country, and especially to God. [45] “What marvelous strength you could be to this nation: doctors, lawyers, teachers, businessmen, government leaders. Arise and shine forth your light! Be Latter-day Saints,” he admonished. Employ your time doing the things that the Lord has said are of the greatest value that a person can do: help to bring souls unto Christ. . . . I see in this institution of learning that the Church has brought to pass in this nation one of the greatest movements of the world to bring to pass the salvation of the people of this nation. It is impossible to measure the contribution that each of you will make.” [46]

Although it is perhaps impossible to measure the impact of these Benemérito alumni and faculty, a few statistics and personal experiences paint a more vivid picture. Although there are other factors influencing the growth of the Church in Mexico, we note that at the commencement of the school there were approximately eight thousand members of the Church in Mexico, many of whom lived in the Mormon colonies. Today there are over one million, making it the largest country of Church membership outside of the United States. Approximately twenty-three thousand of them are graduates of Benemérito who have produced a large posterity grounded in the gospel of Jesus Christ. A report of Benemérito alumni of students who graduated during the school’s first decade lists one General Authority, four Area Seventies, twelve regional representatives, twenty-six mission presidents, and forty-three stake presidents. [47] According to a recent study, of the current stake presidents serving in Mexico, 25 percent are alumni of Benemérito. [48]

Efrain Villalobos, the first teacher mentioned, was one who gave back. Although he declared that he did not want to be a chef, a stake president or a teacher, he ended up becoming all three as he prepared and served food to not only the students who lived in his home, to his own children, but also to the missionaries who were under his leadership as a mission president. [49]

Magdalena Soto, who watched her older sister, Irma, get splattered with pig food by her mother, also gave back. Upon graduation from Benemérito, Magdalena received a degree in biology and psychology and joined her older sister as a teacher at Benemérito. She would later marry, becoming the wife of a stake president at age twenty-four. They would raise seven active children. All except one daughter have served full-time missions, and all are sealed in the temple. One of her daughters is a graduate from the J. Reuben Clark Law School at BYU and practices immigration law in Utah. Their mother joined the Church shortly before her death. [50]

Abraham Martinez, whose grandmother sacrificed to help him attend Benemérito, where he ate his first three meals in a day and took his first real shower, explained that he served a mission after he graduated from secundaria and normal school at Benemérito. Upon his return he taught in the Church Educational System in the elementary schools, as a seminary and institute teacher, as an institute director, as an area coordinator, and most recently as the CES area director of Mexico. In addition, he has served as a bishop, a stake president, and a mission president and now serves as an Area Seventy. Following his release as a mission president, Martinez returned to his employment at Benemérito. Choosing a different young men’s cottage every week, Martinez conducted missionary training every morning at five thirty. One of the highlights of his life was receiving a letter from a missionary stating that they had found Abraham Martinez’s mother and baptized her. “The impact of Benemérito in my life is large,” he reminisced. “As a student and a leader I have lived on this campus for over twenty years. I found my eternal companion, and all three of my children were born here. The young men I taught here baptized my mother. There are no words to express the gratitude I have for this school.” [51]

The impact of Benemérito, however, reaches beyond the family and expands throughout the Church and Mexico. “Many of the alumni are stake presidents, own companies, are doctors and attorneys. Whatever their occupation, they use the principles of the gospel that they learned as students here at Benemérito.” Martinez shared. Speaking of the impact of the community and country Martinez explained that many alumni have gone into politics, including some who have become members of the Mexican senate and one who became administrator of health for his state. When asked how Benemérito students compared with other students in Mexico City, the chief of police responded, “If all students could be like the students who have and are now attending Benemérito, this city would be a different place. We would have little or no crime, there would be a much greater level of honesty and respect. It would be a much safer and better place to live. We never have a problem with students from this school.” [52] When asked his thoughts on the closing of Benemérito, Cesar, the public relations and recruiting director for the Universidad del Valle de Mexico, the largest university in Mexico, responded: “I think it’s horrible. Mexico needs more schools like Benemérito. Not less. The students who graduate from here have a higher moral standard. We need more schools like this not less.” [53] When asked how Benemérito compares to other schools, he replied: “I am personally over nearly two hundred preparatory schools. There is no other school like Benemérito. Benemérito focuses on the whole person. They take students from all over Mexico, wealthy and poor and focus on helping them learn principles and live the values of a good person in alignment with the Mormon Church. . . . Benemérito students stand out. They are confident and able. Rather than focusing on themselves, they have reached a level where they desire and are able to focus on building others.”

Alfredo Mirón, when asked how the school affected his life, responded, “Benemérito gave me a vision to change my life. I married in the temple and have four children, 3 of whom attended Benemérito, who strive to be faithful members of the Church and have professions. I worked for the Church Educational System for years, have served as a bishop, a stake president, a mission president, and the director of Benemérito. All of this is possible because of Benemérito.” [54] Alfredo Mirón was sustained as an Area Seventy in the April 2013 general conference. The foundational experiences he gained as a student have and will continue to impact generations of people in and out of the Church, especially in Mexico.

Jesus Flores, who worked at Benemérito to pay for his own education and was able to save up enough money to bring all of his siblings there, also was greatly impacted by Benemérito. As a result of his hard work, he was offered a scholarship to BYU where he studied English. After leaving BYU, he returned to Mexico, where he received a job teaching English as a second language for the government. In this position he has been influential in educational policies throughout Mexico. “Because the Church gave me such incredible opportunities,” he stated, “I was able to not only pay for myself and my siblings then, but I was able to raise my standard of living and be able to provide for my own family and educate my own children, and hopefully make a small difference in the world.” [55]

Marcela Burgos de Rojas, the young basketball player and normal school student, met Jorge Rojas, the one who served as a teacher and basketball coach as a full-time missionary. With the permission of both of their parents, the urging and unheard-of approval of Director Wagner, they dated and were married the day after graduation. “I did not want to marry him until I graduated,” she admitted. “So I got dressed up for graduation and graduated one night, and the next day I wore the same dress and married Jorge.” Together, they have raised a wonderful family and have been a great benefit to the Church throughout the world. With the support of his wife, Brother Rojas has fulfilled many callings, including mission president of the Mexico Guadalajara Mission, stake president twice, and regional representative twice. He became a member of the Second Quorum of the Seventy in 1991. In 2004 he was called as an Area Seventy and was most recently called as the temple president of the Guayaquil Ecuador Temple. “Benemérito has been the key to opportunity for thousands of youth like myself,” Rojas reflected. [56]

After leaving his pueblo for the first time and being touched by the songs in sacrament meeting, Miguel Velez Adame continued his education through normal school at Benemérito, where he met his future wife and married her in the Mesa Arizona Temple. They both used their degrees to teach in the Church schools and eventually opened their own elementary school in their home town, “applying all that they were taught at Benemérito.” Reflecting on his experience as a young boy he explained, “If I had to live my life again, without thinking for a minute, I would return to Benemérito.” [57]

Conclusion

On November 13, 1947, Elder Spencer W. Kimball, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, described his vision of what these people might become. “I had a dream of your progress and development,” he stated.

I saw you as the owners of many farms and gardens. . . . I saw you as the employer, the owner of banks and businesses, . . . as engineers and builders. . . . I saw you in great political positions and functioning as administrators of the land. I saw you as heads of government . . . and in legislative positions. . . . I saw many of your sons become attorneys. I saw doctors, . . . owners of industries and factories. I saw you as owners of newspapers with great influence in public affairs. I saw great artists among you. . . . Many of you I saw writing books and magazines and articles and having a powerful influence on the thoughts of the people of the country. . . . I saw the Church growing in rapid strides and I saw wards and stakes organized. . . . I saw a temple. . . . I saw your boys and some girls on missions, not only hundreds but thousands. [58]

Without any question, Benemérito de las Americas has played a key role in seeing Elder Kimball’s vision come to fruition. Without exception, every element of his vision has been fulfilled by alumni of this school.

One month after the announcement, over fifteen thousand alumni, from all over Mexico and parts of the world, joined together on Benemérito campus to reunite and express appreciation for the opportunity they had been given to attend such a school. Sentiments of joy, humility, faith and gratitude were expressed freely in song, dance, firesides, discussions, and meetings. Although it was difficult and emotional for many of those involved to see this era come to an end, they expressed gratitude for the trust the Lord had in the people of Mexico to open a new missionary training center. When asked what the fruits of Benemérito are, Alfredo Mirón, the school’s last director, gestured with his hands to include all the gathered crowd, and answered simply, “Look and see.”

Notes

[1] Jeffrey R. Holland, remarks at announcement of Benemerito’s transition to a Missionary Training Center, January 29, 2013, transcript in author’s possession; emphasis added; https://

[2] Richard O. Cowan, The Latter-day Saint Century (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1999), 160–61.

[3] Cowan, Latter-day Saint Century, 160–61.

[4] Casey P. Griffiths, “The Globalization of Latter-day Saint Education” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 2012), 86.

[5] Harvey L. Taylor, “The Story of L.D.S. Church Schools” (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1971), 2:6.

[6] See F. LaMond Tullis, Mormons in Mexico: The Dynamics of Faith and Culture (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1987), for a more comprehensive contextual studies of the history of the Church in Mexico.

[7] Griffiths, “Globalization of Latter-day Saint Education,” 105–97.

[8] Marion G. Romney and Joseph T. Bentley to the First Presidency, December 9, 1959, Joseph T. Bentley papers, container 3, file 5, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University. “Under date of October 11, 1957 you wrote a letter to us and the late President Claudius Bowman of the Mexican Mission in which you said: ‘For some time past we have given consideration to the advisability of establishing a school in Mexico for the accommodation of our youth in that area. Thus far, however, no definite decision has been reached as to where such a school should be located, what the character of the school would be, and who would be expected to attend it. We would be pleased to have you brethren serve as a committee, with Brother Romney as chairman, to make a careful survey and study of the situation and submit to us your recommendations relative thereto.’” Prior to and following his call, Joseph T. Bentley served as the comptroller of the Church’s Unified School System.

[9] Taylor, “Story of L.D.S. Church Schools,” 2:8.

[10] Elder Marion G. Romney and Joseph T. Bentley to the First Presidency, August 1959, President Claudius Bowman was also appointed to this committee but he died in an automobile accident preceding this letter.

[11] Memorandum from Daniel Taylor in 1962, Bentley Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[12] For a more comprehensive explanation of the founding of Benémerito de las Americas, see Barbara E. Morgan, “Benemérito de las Américas: The Beginning of a Unique Church School in Mexico,” BYU Studies Quarterly 52, no. 4 (2013): 89–116.

[13] The Church’s Board of Education in Mexico had determined that the school would be named after “outstanding Mexican civil servants independent of religious influence.” The board suggested Benito Juárez, one of the great Mexican revolutionaries, for the Church’s main center, but this name was previously used for the primary school in Juárez City and for many other schools throughout Mexico. To set them apart, Benemerito de las Américas (Benefactor of the Americas) was an honorific title originally given to Juárez by the government of the Republic of Columbia on May 1, 1865. See Robert Ryal Miller, “Matias Romero: Mexican Minister to the United States during the Juarez-Maximilian Era,” Hispanic American Historical Review 45, no. 2 (May 1965): 228–45, and the title eventually caught on in all of Latin America as an honor they owed the native president of Mexico who instituted a constitution very similar to the United States Constitution. Naming the school thus would not only show honor to this great Mexican leader, but it would encompass the sentiments of all of Latin America, and set it apart from the Catholic schools. For more on Benito Juárez, see Ulick Ralph Burke, A Life of Benito Juarez: Constitutional President of Mexico (London: Remington, 1894.)

[14] Marion G. Romney, remarks at groundbreaking ceremony, November 4, 1963, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[15] Taylor, “Story of L.D.S. Church Schools,” 2:12.

[16] Efrain Villalobos, oral history, interview by Barbara Morgan, February 20, 2013, Mexico City, in author’s possession.

[17] A. Kenyon Wagner and Leona F. Wagner, Historia del Centro Escolar Benemerito de las Americas (n.p., Mexico, D. F.), 15.

[18] Taylor, “Story of L.D.S. Church Schools,” 2:18.

[19] G. Arturo Limon D., La Gratitud Es (n.p. n.d.), 91.

[20] Wagner and Wagner, Historia, 25.

[21] Abraham Martinez, oral history, interview by Barbara Morgan, February 22, 2013, Mexico City.

[22] Clark V. Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico: The Rise of the Sociedad Educativa y Cultural” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1976), 166.

[23] Limon, La Gratitud Es, 145.

[24] Alfredo Mirón M., autobiografía (n.p., n.d.), in author’s possession.

[25] Harvey L. Taylor and Joseph T. Bentley to Ernest L. Wilkinson, memorandum, December 30, Joseph T. Bentley papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, C-5, F-3 Johnson 124.

[26] Daniel P. Taylor to Joseph T. Bentley, September 20, 1960, Joseph T. Bentley papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, C-5, F-3.

[27] Jesus Flores, oral history, interview by Barbara Morgan, February 18, 2013, Mexico City, in author’s possession.

[28] Taylor, “Story of L.D.S. Church Schools,” 2:36.

[29] For a greater contextual understanding of education in Mexico, see Lucrecia Santibanez, Georges Vernez, and Paula Razquin, Education in Mexico: Challenges and Opportunities (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2005).

[30] Limon, La Gratitude Es, 143–50.

[31] Limon, La Gratitude Es, 123.

[32] Guadalupe Lopez Duran, oral history, interview by Barbara Morgan, February 20, 2013, Mexico City, transcript in author’s possession.

[33] Carlos Zepeda, Plan Estrategico B de A 2003–2008, in author’s possession.

[34] See Taylor, “Story of L.D.S. Church Schools,” and Johnson, “Mormon Education in Mexico,” 183. The wall does not exist anymore, and the students are able to walk freely between the buildings on campus.

[35] Limon, La Gratitude Es, 143–50.

[36] Taylor, “Story of L.D.S. Church Schools,” 2:18.

[37] Taylor, “Story of L.D.S. Church Schools,” 2:30.

[38] Limon, La Gratitude Es, 137–42.

[39] Arturo Limon, interview by Barbara Morgan in Mexico City on February 17, 2013. Transcript in author’s possession.

[40] Wagner and Wagner, Historia, 15.

[41] Woman from Chalco, oral history, interview by Barbara Morgan, February 2013, Mexico City, in author’s possession.

[42] Russell M. Nelson, address at Benemerito de las Americas, January 29, 2013, transcription in author’s possession. https://

[43] Abraham Lozano, statistical report for Benemerito, February 21, 2013, in author’s possession.

[44] Russell M. Nelson, address at Benemerito de las Americas, January 29, 2013, transcription in author’s possession.

[45] Elder Marion G. Romney, Antorcha de Chiquihuite, 1964–1966, graduation ceremonies, October 26, 1966.

[46] Elder Marion G. Romney, Antorcha de Chiquihuite, graduation ceremonies, October 26, 1966.

[47] Wagner and Wagner, Historia, 143–45.

[48] Abraham Lopez (assistant director at Benemérito, 2012–13), e-mail message to Barbara E. Morgan, February 20, 2013.

[49] Efrain Villalobos, interview by Barbara Morgan.

[50] Magdalena Soto, oral history, interview by Barbara Morgan, June 6, 2013, Provo, UT.

[51] Abraham Martinez, oral history, interview by Barbara Morgan, June 12, 2013, Mexico City, transcript in author’s possession.

[52] Chief of Police, Mexico City, interview by Barbara Morgan, February 21, 2013, Mexico City, transcript in author’s possession.

[53] Cesar Munos Vega, oral history, interview by Barbara Morgan, June 20, 2013, Mexico City, transcript in author’s possession.

[54] Alfredo Mirón, interview with Barbara Morgan, February 18, 2013, transcript in author’s possession.

[55] Jesus Flores, interview by Barbara Morgan.

[56] Jorge and Marcela Rojas, oral history, interview by Barbara Morgan, June 12, 2013, Mexico City, interview in possession of author.

[57] Limon, La Gratitude Es, 151.

[58] Dell Van Orden, “Emotional Farewell in Mexico,” Church News, February 19, 1977, 3. See also Eduardo Balderas, “Great Hopes for Future Held Out to Lamanites in Third Conference,” Church News, November 15, 1947, 1, 12.