Finding Doctrine and Meaning in Book of Mormon Isaiah

RoseAnn Benson and Shon D. Hopkin

RoseAnn Benson and Shon D. Hopkin, “Finding Doctrine and Meaning in Book of Mormon Isaiah,” Religious Educator 15, no. 1 (2014): 95–122.

RoseAnn Benson (rabenson@byu.edu) was an adjunct professor of ancient scripture at BYU when this article was published.

Shon D. Hopkin (shon_hopkin@byu.edu) was an assistant professor of ancient scripture at BYU when this article was published.

The plain and more accessible writings of Nephi, Jacob, Abinadi, and Christ act as keys to illuminate Isaiah, and the writings of Isaiah in turn act as a key to fully unlock the profound nature of Book of Mormon prophetic thought. Ted Henniger, Isaiah, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

The plain and more accessible writings of Nephi, Jacob, Abinadi, and Christ act as keys to illuminate Isaiah, and the writings of Isaiah in turn act as a key to fully unlock the profound nature of Book of Mormon prophetic thought. Ted Henniger, Isaiah, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

(The plain and more accessible writings of Nephi, Jacob, Abinadi, and Christ act as keys to illuminate Isaiah, and the writings of Isaiah in turn act as a key to fully unlock the profound nature of Book of Mormon prophetic thought.)

For many readers of the Book of Mormon, the Isaiah passages quoted in 1 and 2 Nephi, Mosiah, and 3 Nephi present an almost insurmountable obstacle made up of Hebrew poetry and imagery. Particularly daunting is the sudden change of style from historical narrative and the sermons and teachings of Nephi, Lehi, and Jacob to the more literary and symbolic style of the Isaiah passages. President Boyd K. Packer observed: “Just as you settle in to move comfortably along, you will meet a barrier. The style of the language changes to Old Testament prophecy style. For, interspersed in the narrative, are chapters reciting the prophecies of the Old Testament prophet Isaiah. They loom as a barrier, like a roadblock or a checkpoint beyond which the casual reader, one with idle curiosity, generally will not go.” [1]

Since Nephi clearly states that he loves “plainness” (2 Nephi 25:4), many readers are somewhat perplexed by the inclusion of the Isaiah chapters in his writings. What these readers fail to understand is that Nephi included the writings of Isaiah not as a test or advanced course for scripture readers but because they formed the foundation of his own scriptural understanding, which he then communicated in plainness in his writings. [2] In other words, the simplicity in Nephi’s writings reflects a depth of understanding that can only be grasped after fully absorbing the meaning of Isaiah’s words. Therefore, the reader who absorbs and plumbs the depths of Isaiah’s writings, as Nephi did, will more fully understand the profound insights contained in the clarity of Nephi’s words. The plain and more accessible writings of Nephi, Abinadi, Christ, Mormon, and Moroni act as keys to illuminate Isaiah, and the writings of Isaiah in turn act as a key to fully unlock the profound nature of Book of Mormon prophetic thought.

Twice the Savior urged the Nephites to study the words of Isaiah. First, after declaring that they would be fulfilled, Jesus commanded, “Behold they are written, ye have them before you, therefore search them” (3 Nephi 20:11). Second, after quoting Isaiah 54 and numerous other passages, the Savior admonished the Nephites: “Ye ought to search these things. Yea, a commandment I give unto you that ye search these things diligently; for great are the words of Isaiah. For surely he spake as touching all things concerning my people which are of the house of Israel; therefore it must needs be that he must speak also to the Gentiles” (3 Nephi 23:1–2).

In response to this commandment, this article’s chief purpose and contribution to existing Isaiah scholarship is to show how the main doctrines and purposes of the Book of Mormon, found on the title page and in the writings of Book of Mormon prophets, mirror and follow the central focus of the Isaiah chapters. [3] Specifically, we will show how the scattering and gathering of the house of Israel, due to their acceptance or rejection of the covenant of Christ, illustrate the doctrines of justice and mercy as taught in the Book of Mormon. While in one sense this article simplifies the message of Isaiah by pointing to overarching themes recognized by the Book of Mormon prophets, we do not intend to obfuscate the complexity of Isaiah’s teachings, the nuance of his literary skills, or his multilayered approach that emphasizes numerous concepts not mentioned in this article. In this article we intend to focus on one way of teaching Isaiah that will help students synthesize the overarching themes of his messages, rather than to minimize other important concepts he taught that have been discussed by other scholars. [4]

To create a foundation for this discussion, we will first briefly describe Isaiah’s writing style and historical context. Next, we will propose new possibilities for how Nephi and Jacob used Isaiah’s teachings as they applied his writings to their own situation, which will be followed by a discussion of Nephi, Abinadi, and Christ’s extensive quotations of Isaiah. Finally, illustrations of the connections between the major purposes of the Book of Mormon and the writings of Isaiah will illustrate the meaning and relevance of many of Isaiah’s statements and demonstrate why Nephite prophets and the Savior found it so important to quote the writings of Isaiah.

Writing Style

President Packer’s observation regarding the barrier of the Isaiah chapters raises several questions: Why is Isaiah so difficult? Is he deliberately challenging? Why does he use poetic parallelism rather than employ a more straightforward style like Nephi, who writes “mine own prophecy, according to my plainness; in the which I know that no man can err” (2 Nephi 25:7)?

In Isaiah’s call to be a prophet, known as his “throne theophany,” [5] he was given this instruction: “Go and tell this people—hear ye indeed, but they understood not; and see ye indeed, but they perceived not. [6] Make the heart of this people fat, and make their ears heavy, and shut their eyes—lest they see with their eyes, and hear with their ears, and understand with their heart, and be converted and be healed” (2 Nephi 16:9–10; compare Isaiah 6:9–10). The New Testament references this Isaiah passage several times (see Matthew 13:10–15; Mark 4:12; John 12:37–41; Acts 28:25–28) and makes the statement one of consequence—they did not understand or perceive because they hardened their hearts and blinded their minds. Nephi makes a similar claim in the Book of Mormon, that by “looking beyond the mark” the Jews dulled their spiritual capabilities. Jacob explained, “They despised the words of plainness, and killed the prophets, and sought for things that they could not understand; . . . [therefore] God hath taken away his plainness from them, and delivered unto them many things which they cannot understand, because they desired it” (Jacob 4:14). [7] In other words, both Nephi and Jacob connected Isaiah’s style of prophecy with the cultural background of the Israelites, created as a result of their desires, and called by Nephi “the manner of prophesying among the Jews” (2 Nephi 25:1). [8] Nephi and Jacob did not emulate certain features of that manner of teaching in their own prophecies; nevertheless, they valued Isaiah’s prophecies highly and testified that they came from the Lord.

Isaiah’s poetic language does reveal great truths in profound ways to those willing to invest time, humility, and faith, even as it hides those truths from the spiritually immature. [9] As an additional challenge to the Nephites and to latter-day readers, Isaiah’s similes and metaphors were often based in agricultural and geographical details that were no longer familiar to the Nephites and are not part of a modern understanding.

Isaiah’s major poetic technique is the use of parallelisms—the repetition of a thought, idea, grammar pattern, or key word. [10] His writing is further characterized by its potential for multiple applications. This means that many of his prophecies had a historical fulfillment in his day, and others were fulfilled in future times—such as among the Nephites, and at the time of Jesus Christ—and some even have yet to be fulfilled, such as in the latter days at Christ’s Second Coming. [11] For example, after Nephi’s extended quotation of the words of Isaiah in 2 Nephi 12–24, he proceeded to interpret and apply these words first to the Jews (2 Nephi 25:9–20), then to the descendants of Lehi (25:21–26:11), and then to the Gentiles in the latter days (26:12–30:18). Although it may be helpful to understand each poetic device and each potential level of application for the Isaiah passages in the Book of Mormon, readers need not comprehend every simile, metaphor, allegory, poetic meaning, or application to find overarching themes and doctrines.

Isaiah’s Original Historical Context

As a prophet who was given access to the kingly court of Judah, Isaiah regularly prophesied of the consequences of sin for Judah and other kingdoms and attempted to persuade those who would listen to return to faithful worship of the Lord. Isaiah’s era included strife between the kingdoms of Israel (the northern kingdom) and Judah (the southern kingdom) during the reign of King Ahaz (c. 734 BC; see 2 Kings 16:5), King Hezekiah’s religious and temple reform (c. 728 BC; see 2 Kings 18:4), the deportation of the northern kingdom of Israel by Assyria (c. 721 BC; see 2 Kings 17:23), and the siege of Jerusalem by the Assyrian King Sennacherib during the reign of King Hezekiah (701 BC; see 2 Kings 18:17). For example, Isaiah 7 (2 Nephi 17) mentions the plotting of the king of Israel and the king of Syria to replace King Ahaz of Judah with a puppet king who would join together with them against the Assyrian Empire (see 2 Kings 16; 2 Chronicles 28). The account assumes the reader is aware of the geopolitical crisis that led to this attempt and that Ahaz was a wicked king who wearied both Isaiah and the Lord with his refusal to seek a sign from God, as Isaiah instructed him to do. Because Ahaz would not follow Isaiah’s counsel, the Lord provided his own sign; Isaiah prophesied of the birth of a child called Immanuel, literally “with us is God,” indicating divine help (see Isaiah 7:14; 2 Nephi 17:14).

Appreciating the historical, literary, and doctrinal background of Isaiah is useful in gaining deeper spiritual insights that then help us liken the scriptures to ourselves appropriately. [12] Isaiah’s words had meaning for the people of his day as well as for those of future time periods. For example, Isaiah likened Jerusalem to ancient Old Testament cities and “address[ed] them directly by name as actually being Sodom and Gomorrah.” [13] Nephi and Jacob, who understood the historical, literary, and doctrinal background of Isaiah’s writings, could properly liken Isaiah’s prophecies to their own people, thus providing an additional level of prophetic application. This background knowledge will help today’s readers better understand the original purposes of ancient prophecies before they endeavor to apply them further. [14]

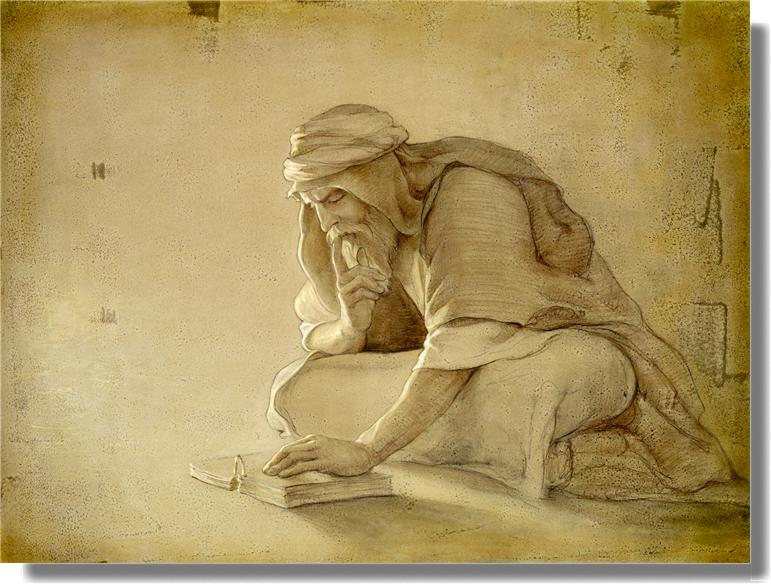

Lehi and his family had access to the words of Isaiah on the plates of brass. Nephi declared that the words of Isaiah "shall be of great worth unto them in the last days; for in that day shall they understand them" (2 Nephi 25:8). Joseph F. Brickey, Lehi Studying the Brass Plates. Used by permission. www.josephbrickey.com

Lehi and his family had access to the words of Isaiah on the plates of brass. Nephi declared that the words of Isaiah "shall be of great worth unto them in the last days; for in that day shall they understand them" (2 Nephi 25:8). Joseph F. Brickey, Lehi Studying the Brass Plates. Used by permission. www.josephbrickey.com

Nephi’s and Jacob’s Introductory Context of Isaiah

Nephi stated that he delighted in plainness and subsequently restated Isaiah’s words in his own straightforward style, so why did he not simply move directly to his own clearly stated message? There appear to be at least three reasons for quoting Isaiah:

- Because Lehi’s descendants were a branch of Israel broken off and led away, Nephi saw Isaiah as their prophetic connection back to their homeland. Isaiah was their reassurance that they were natural branches of the “olive tree,” the house of Israel—that they had not been forgotten—and that in the latter days they would be re-grafted into that original tree (see 1 Nephi 15:12–18; 21).

- Nephi was following the time-honored prophetic pattern of ancient Israel, continued later in the New Testament and still today, of quoting an earlier prophet as an additional authority. [15]

- Nephi was showing later readers the scriptural context that provided his own clear understanding of true principles in order to enable them to gain the depth of understanding that he possessed. [16]

Nephi set the stage for his first quotation of Isaiah by citing clear prophecies about the “God of our fathers, . . . the God of Abraham, and of Isaac, and the God of Jacob” from the brass plates and by then explaining that Isaiah was writing to all the house of Israel (1 Nephi 19:10–21). After explaining his reason for teaching from Isaiah (22–24), he quoted Isaiah 48–49. Nephi’s choice to start with two chapters from the end of Isaiah’s writings is instructive; Isaiah’s later teachings include more descriptions of God’s mercy and long-suffering love toward the house of Israel than his earlier teachings do. These two chapters provided a hopeful final outlook for Nephi’s people while describing their challenging departure from their homeland. [17] Subsequent to reading these prophecies concerning God’s love for Israel and the servant who would gather his people, Nephi interpreted his quotation of Isaiah with an extended exposition on the destruction of the wicked, the preservation of the righteous, and how the Holy One of Israel would gather his people in the last days (see 1 Nephi 22:1–28). Nephi underscored his exposition on mercy by citing a familiar Mosaic passage:

A prophet shall the Lord your God raise up unto you, like unto me; him shall ye hear in all things whatsoever he shall say unto you. And it shall come to pass that all those who will not hear that prophet shall be cut off from among the people.

And now I, Nephi, declare unto you, that this prophet of whom Moses spake was the Holy One of Israel. (1 Nephi 22:20–21; emphasis added; see also Deuteronomy 18:15)

In commenting on Nephi’s inclusion of Isaiah’s writings in 1 Nephi 20–21, S. Kent Brown notes that the prophecies coincide with the difficulties that Lehi’s family encountered in their wilderness experience. For example, passages from Isaiah mirror the description of their journey: they were “broken off and [were] driven out because of the wickedness of the pastors of my people” (1 Nephi 21:1; Isaiah 48:1) and “they thirsted not; he led them through the deserts; he caused the waters to flow out of the rock for them” (1 Nephi 20:21; Isaiah 49:21). From Nephi’s point of view, Isaiah was speaking about him and his people. [18] It appears that Nephi sees in each of his quotations of Isaiah a direct application to his family’s experiences: Lehi’s throne theophany (see 1 Nephi 1:8; compare with 2 Nephi 16:1); the law and the word of God contained in the brass plates (see 1 Nephi 5:11–16; compare with 2 Nephi 18:20); the journey through the desert wilderness, which included famine, thirst, and fatigue that was mitigated by God (see 1 Nephi 16:35; 17:1–3; compare with 1 Nephi 20:20–21); his apocalyptic vision of Nephite apostasy, destruction of the wicked, and visitation by Christ (see 1 Nephi 12–14; compare with 2 Nephi 13–14); questions about God’s vineyard and the re-grafting of Israel into the olive tree (see 1 Nephi 15:7; compare with 2 Nephi 15:1–4, 26); and the separation of the family into two warring clans (see 2 Nephi 5:5; compare with 2 Nephi 17:1, 6). These examples from the story of Lehi’s family align with prophecies of Isaiah that Nephi quoted.

Jacob introduced his quotation of Isaiah in 2 Nephi 7–8 by explaining that he would quote from Isaiah because Isaiah’s words speak of “things which are, and which are to come . . . concerning all the house of Israel” (2 Nephi 6:4–5). According to Jacob, the future scattering and gathering of the house of Israel would be dependent upon their response to a “knowledge of their Redeemer” (2 Nephi 6:11), just as it had been anciently. [19] Following the death of Lehi and the separation of his descendants into two factions, Jacob quoted from Isaiah 50 regarding an unrepentant people and a willing servant (see 2 Nephi 7); from Isaiah 51, urging the Nephites to look back to the righteous progenitors of the covenant, Abraham and Sarah (see 2 Nephi 8:1–23); and from Isaiah 52:1–2, bidding Zion to rejoice in her future redemption (see 2 Nephi 8:24–25). Jacob applied Isaiah’s teachings first to the Nephites, as warnings and prophecies for them specifically, then to the Jews generally, and then to all the house of Israel.

It appears that Jacob understood that the Nephites were following the same tragic pattern as the Israelites in the Holy Land. The death of Solomon precipitated the breakup of the united kingdom of Israel into northern and southern polities, just as the death of Lehi brought about the separation of the family into Nephites and Lamanites. The unrepentant people could be likened to those of the northern kingdom (see 1 Kings 12:20, 25–28) and the Lamanites (see 2 Nephi 5:5–8, 20–25). The willing servant most likely symbolizes Christ and his prophets but could also have initially symbolized the people in the southern kingdom and the Nephites (2 Nephi 7:1–9). [20] The historical devastation of the northern kingdom by Assyria and the prophetic pronouncement regarding the demise of the southern kingdom by Babylon (2 Nephi 6:8) were part of Jacob’s cultural inheritance. He therefore taught Isaiah’s words to prevent the same captivity and destruction from occurring to his people. Jacob also knew from Nephi’s apocalyptic vision (see 1 Nephi 12) about the eventual apostasy and destruction of the two nations springing from Lehi. At about the time the southern kingdom of Judah was taken into captivity and scattered, Lehi’s family had been led away to a new promised land. [21] The two Israelite kingdoms had become deaf to the messages taught by their prophets and did not understand the promise of a Savior, just as both the Lamanites and the Nephites would eventually become deaf to the message of the gospel.

By quoting Zenos’s allegory of the olive tree, Jacob answered a question of supreme importance to both the house of Israel in general and to him and his future posterity specifically, as a branch of that house: “How is it possible that these, after having rejected the sure foundation, can ever build upon it, that it may become the head of their corner?” (Jacob 4:17). As phrased by Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, the central theme of this allegory and the answer to Jacob’s question is the at-one-ment: returning, repenting, and reuniting. [22] Jacob used the cultural and historical heritage found in Isaiah’s prophecies and Zenos’s allegory to give context to his people’s current situation, to call them to repentance, and to reassure them that God’s plan provided for their future redemption.

Nephi’s Large Quotation of Isaiah: Covenants, the House of Israel, and Christ

One explanation for the whole chapters and passages of Isaiah interspersed throughout certain parts of the Book of Mormon is that Isaiah’s messages resonated with the Nephites as they likened his words to themselves and looked forward to the prophecies’ further fulfillment in the latter days. Moroni clearly states that the Book of Mormon “is to show unto the remnant of the house of Israel what great things the Lord hath done for their fathers; and that they may know the covenants of the Lord, that they are not cast off forever—And also to the convincing of the Jew and Gentile that Jesus is the Christ, the Eternal God, manifesting himself unto all nations” (Book of Mormon title page, emphasis added). [23] In accordance with this declaration, the Lord focused the authors and compilers of the Book of Mormon on two fundamental themes: (1) the house of Israel, and (2) the covenant of Christ, often referred to as the Abrahamic covenant. [24]

Nephi’s introduction of his long quotation from Isaiah in 2 Nephi 11 identifies that these themes—types and shadows of Christ and the covenants of the Lord with the house of Israel—are important to him. It also underscores the overall themes of the Book of Mormon (see 2 Nephi 11:4–5). Nephi deliberately chose to quote passages from Isaiah that would focus on the house of Israel and the Abrahamic covenant. [25]

We have found that if a teacher identifies the main focus of the passages quoted by Nephi and Jacob, Isaiah becomes a more readable and understandable text for students. Jacob’s introductory quotation of Isaiah early on sets the stage: “Hearken unto me, ye that follow after righteousness. Look unto the rock from whence ye are hewn, and to the hole of the pit from whence ye are digged. Look unto Abraham, your father, and unto Sarah, she that bare you; for I called him alone, and blessed him” (2 Nephi 8:1–2). Almost all of the quotations from Isaiah can be understood as flowing from the covenant made with Abraham and Sarah, focusing on the consequences of obedience or disobedience to that covenant. Obedience brings gathering and illustrations of the doctrine of mercy, whereas disobedience brings scattering and the doctrine of justice. Isaiah’s metaphors and similes emphasize and repeat these themes. [26]

The importance of understanding the central themes in Nephi’s use of Isaiah cannot be overstated. Modern readers are typically comfortable with the concepts of justice and mercy, especially when understood as a loss or addition of spiritual blessings, but are often less familiar with the powerful concepts of punishment, destruction, or the scattering and gathering of Israel. When Isaiah warns of punishment, destruction, and scattering, he is teaching what modern readers understand as justice, or the idea that sins cause a loss of both spiritual and temporal blessings. When he speaks of gathering, he is referring to what modern readers understand as mercy, or the spiritual and physical blessings that come through repentance and obedience because of the Atonement of Jesus Christ. In accordance with this ideology, the Book of Mormon repeats the phrase “prospering” to denote mercy, or blessings from God. The most important warning in the Book of Mormon is against being “cut off” from the Spirit and left to one’s own strength, denoting justice and punishment (see 2 Nephi 1:20, 4:4; Alma 9:13, 36:30, 37:13, 38:1; Ether 2:15). Thus the following terms are generally linked together: scattering, punishment, being cut off, justice; and gathering, blessings, prospering, mercy. [27] In the writings of Isaiah and Nephi, these principles and doctrines have meaning through a covenant relationship, and have power because of the Atonement of Jesus Christ. A similar focus on the power of covenants centered in Christ continues later in the Book of Mormon through the teachings of Abinadi and Christ.

Abinadi’s Use of Isaiah’s Words

Abinadi also used Isaiah’s words to preach of Christ and covenants. He was called two times to cry repentance to apostate Nephites living in the land originally settled by Lehi’s son Nephi. Interestingly, the wicked priests of King Noah began to cross-examine Abinadi by quoting a passage of Isaiah (see Mosiah 12:21–24; Isaiah 52:7–10). They ask, “What meaneth the words which are written, . . . How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings; that publisheth peace?” (Mosiah 12:20–21). Some of the implications of Nephite history and this question are their view that

- The priests have the scriptures with them and are aware of Isaiah’s teachings (see Mosiah 12:20–21).

- They believe they are living in the “promised land” settled by Nephi (see Omni 1:27; Mosiah 9:3).

- They believe they are worshipping in a temple that is even more beautiful than when Nephi originally built it (see Mosiah 11:10–11).

From their point of view, Abinadi’s message to them should have been glad tidings rather than a condemnation of their king, a call to repentance, and a prophetic warning of bondage and destruction (see Mosiah 12:21–24). [28] Abinadi responded to their interrogation by teaching the Ten Commandments and quoting Isaiah’s messianic promise before finally addressing their initial question (see Mosiah 15:10–18). [29] Abinadi’s quotation of Isaiah’s “Song of the Suffering Servant” (Mosiah 14; Isaiah 53) and explanation of the “how beautiful upon the mountains” passage both reflected the promise of gathering and great blessings to those who would come to Christ and testify of him—they “declare his generation” and become “his seed” (see Mosiah 14, 12:21; 15:10–18; Isaiah 53). Noah’s priests, with the exception of Alma, did not fit this designation.

Christ’s Use of Isaiah’s Words

The risen Christ promised the Nephites that the words of Isaiah would be fulfilled, associating them with the fulfilling of the covenant—meaning the Abrahamic covenant—which promises both a spiritual gathering through knowledge of Christ and a temporal gathering to a promised land (see 3 Nephi 20:11–14). Christ encouraged the Nephites to put on the power and authority of the priesthood (see 3 Nephi 20:36; D&C 113:8) and promised redemption to those who would make covenants by his authority and testify of him (see 3 Nephi 20:36–40). Christ promised a sign in the latter days that would indicate the beginning of the fulfillment of Isaiah’s words and the fulfilling of the covenant. The sign prophesied was the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, “a great and a marvelous work” (see 3 Nephi 21:9; Isaiah 29:14), accomplished by a servant of God—interpreted in latter days as Joseph Smith—whose reputation and life would be marred for his efforts (see 3 Nephi 21:10; Isaiah 52:14). Christ called the writings of the Book of Mormon his words and warned that all who rejected them would be cut off from the covenant family (see 3 Nephi 21:11; emphasis added). Christ concluded his quotation of Isaiah with an entire chapter promising phenomenal growth in the latter days and requiring that the “gospel tent” of Zion be enlarged (see 3 Nephi 22:1–3; Isaiah 54:1–3)—he also included Isaiah’s prophecies that righteousness would be established as the norm and that Christ’s children would prosper against their enemies (see 3 Nephi 22:13–17; Isaiah 54:13–17).

Illustrating Isaiah

The four illustrations provided below are designed to assist students in better understanding the Isaiah chapters by:

- Presenting general themes of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon;

- Connecting themes of the Book of Mormon as a whole to central names in Isaiah’s writings; [30]

- Demonstrating how the concepts of scattering and gathering, based on the Abrahamic covenant and centered in Christ, are central to the Isaiah chapters;

- Providing detailed examples from the Isaiah chapters in order to demonstrate how specific phrases from the Isaiah chapters can be understood when they are placed in a context of the main themes of the Book of Mormon. The fourth illustration should provide sufficient examples for students of the Isaiah chapters, enabling them to view those passages within this framework.

Themes

Covenants of the Lord

The Holy One of Israel/

|

Path of rejection |

Path of Acceptance |

|

Sin ↓ |

Obedience/ ↓ |

|

Judgments/ ↓ |

Cleansing/ ↓ |

|

Scattering ↓ |

Gathering ↓ |

|

Cut off from the Lord |

Prosper in the land |

Fig. 1: General Themes of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon.

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows that the Book of Mormon’s basic message, according to the title page, centers on the covenant of the Lord. Latter-day Saint students recognize this as the gospel covenant that was given to those who sustained Heavenly Father’s plan in the council in heaven. [31] The Book of Mormon teaches that the covenants promise the raising up of one who is like unto Moses and who was identified by Nephi as the Holy One of Israel (see 1 Nephi 22:20–21). The consequences of individual acceptance or rejection of Jesus Christ and his covenant are exemplified in the principles of scattering and gathering and in the doctrines of justice and mercy. Scattering is the consequence of sin, and its results are judgment and justice, or being cut off from the Spirit. Gathering is the result of obedience or repentance and brings forth cleansing and mercy, or as the Book of Mormon explains it, “prospering.” See 1 Nephi 2:20 for the first of many examples of this term or see 1 Nephi 13:20 for the phrase “prosper in the land.”

Names and Terms

Isaiah [means “Jehovah is salvation”]

Abraham and Sarah [recalls the Abrahamic covenant]

Immanuel [means “God with us”]

|

Path of rejection |

Path of acceptance |

|

Justice ↓ |

Mercy ↓ |

|

Scattering ↓ |

Gathering |

|

Maher-shalal-hash-baz [means “speed, spoil, hasten, plunder”] ↓ |

Shearjashub [means “a remnant shall return”] ↓ |

|

Judgments ↓ |

Repentance, cleansing ↓ |

|

Cut off ↓ |

Prosper ↓ |

|

BABYLON |

ZION |

Fig. 2: Isaiah’s Names and Terms Highlighting Book of Mormon Themes.

Figure 2

Figure 2 displays the main themes of both the Book of Mormon in general and of the Isaiah chapters specifically. Isaiah declared, “Behold, I and the children whom the Lord hath given me are for signs and for wonders in Israel from the Lord of Hosts, which dwelleth in Mount Zion” (2 Nephi 18:18). Isaiah’s name—meaning “Jehovah is salvation”—reflects the covenant of salvation made with the house of Israel, given to their progenitors Abraham and Sarah, and called the Abrahamic covenant. Isaiah’s name serves as a reminder to all people that the covenant provides for the salvation of mankind as a result of the coming of Immanuel (meaning “God with us”)—or the Holy One of Israel, referring to the condescension of the Son of God.

The principles of scattering and gathering illustrate the doctrines of justice and mercy that are denoted in the prophetic naming of Isaiah’s two sons, Maher-shalal-hash-baz—literally meaning “speed, spoil, hasten, plunder,” or that destruction is imminent—and Shearjashub—meaning “a remnant shall return.” Maher-shalal-hash-baz’s name foreshadowed the coming of conquerors to take captive and scatter the northern and southern kingdoms because they had rejected the covenant as it was manifested through the rituals of the law of Moses and taught by the prophets. Shearjashub’s name, seen on the opposite side of the illustration, prophesied that those who repented and returned to the covenant would be preserved and would receive the joy, comfort, and security of Zion. Since Isaiah knew that most of the house of Israel would reject the covenant, he prophesied that the wickedness of his era would result in the scattering of Israel and captivity to Assyria and Babylon—symbols of Satan’s kingdom. The prophecy of the return of Israel inherent in Shearjashub’s name was partially fulfilled when a portion of the Israelites were allowed to return to Jerusalem seventy years after being deported to Babylon. Nephite prophets interpreted Isaiah’s words to mean that another “return” or gathering would occur in the last days, when the house of Israel would be prepared to accept the covenant provided by Christ and thus enjoy the blessings of Zion, the kingdom of God (see 2 Nephi 25:16–17).

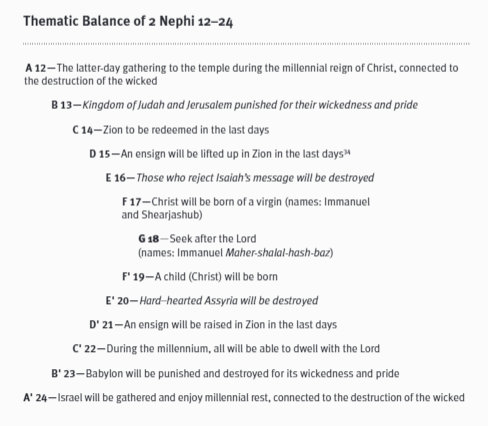

The themes of justice and mercy support the purposes of the Book of Mormon as demonstrated by their centrality in the passages of Isaiah that are quoted in 2 Nephi. Following Hebraic literary form, the meaning of Isaiah’s poetic writings can be found in the balance of these two themes. Thus the central principles found in Nephi’s large quotation of Isaiah are not located at the beginning or end of that section, as modern readers might anticipate. Rather, the cardinal principles are found in the center point of 2 Nephi 12–24, in 2 Nephi 18, and supporting concepts are found at the beginning and end. These supporting concepts expand outward from the essential, central concept—the acceptance or rejection of the covenant with Christ—leading to mercy or justice.

This centrality and balance is demonstrated in the following illustration of the thematic structure of 2 Nephi 12–24. [32] It should be noted, however, that there are too many blocks of material in these chapters that do not fit the chiastic structure illustrated below to be defined as a true chiasm. They are shown here in this form primarily to serve as a modern teaching tool, rather than to indicate how they would have been viewed anciently.

Fig. 3: Thematic Balance of 2 Nephi 12–24. [33] [34]

Fig. 3: Thematic Balance of 2 Nephi 12–24. [33] [34]

Figure 3

As can be seen above, the promise of Christ is the message at the center of the Isaiah chapters, found in 2 Nephi 18 (letter G). Israel’s scattering hinged on its rejection of Christ, or Immanuel, [35] and was prophesied in the divinely mandated name Maher-shalal-hash-baz (see 2 Nephi 18:3). This is the most important warning found in the Book of Mormon: rejecting Christ brings the penalty of being cut off spiritually from the Lord (in italics in Figure 3). The principle found immediately next to that of scattering—in chapters 17 and 19 (letters F and F′)—is mercy, that all who believe in Christ (Immanuel) will be gathered. This concept is represented by the name Shearjashub (in regular font in Figure 3). Isaiah’s writings about scattering and gathering, or justice and mercy, ripple out from the center point of Nephi’s large quotation, demonstrating the beautiful balance of Isaiah’s writing.

Figure 4

Comprehending the overarching themes in this block helps the student find meaning in the details of Isaiah’s poetic voice. Figure 4 illustrates brief quotations from each of the Isaiah chapters provided by Nephite prophets and Christ. These passages demonstrate how the themes of (1) Christ/

To students, what may at first appear in the Isaiah chapters to be a bewildering mix of disconnected detail in reality works together thematically to testify of the importance of the Abrahamic covenant that leads to a Zion-like state of joy. Each of the causes and results in the references listed under scattering and gathering (in the illustration above) is taken directly from the teachings of Isaiah quoted in the Book of Mormon. For example, phrases using words such as divorce, orphaning, apostasy, and captivity fall under scattering; and concepts such as marriage, status as a child, liberation, and return or restoration fall under gathering. Isaiah’s use of names and entities such as Babylon and Assyria symbolize the worldly kingdom of Satan. In contrast, Zion symbolizes God’s kingdom. These polar opposites portray the dichotomy between misery and joy that Book of Mormon prophets teach with plainness and simplicity. Isaiah describes both the consequences of abominable behaviors and the promised blessings of righteousness, under the Abrahamic covenant. Although many of the warnings of Isaiah may appear harsh to the modern student, they are necessarily strong in order to sufficiently warn the wicked, as well as to prepare the reader for the sublime description of the blessings that come to the righteous. The punishments of the wicked are as one side of a coin, balanced by the blessings of the righteous on the other side of the coin. The promised blessings lack power without the balancing strength of the punishments.

Sin, Scattering, Cutting Off, and Justice

- O that thou hadst hearkened to my commandments—then had thy peace been as a river, and thy righteousness as the waves of the sea. Thy seed also had been as the sand; . . . his name should not have been cut off nor destroyed from before me. (1 Nephi 20:18–19)

- For your iniquities have ye sold yourselves. . . . [Ye] walk in the light of your fire and in the sparks which ye have kindled. This shall ye have of mine hand—ye shall lie down in sorrow. (2 Nephi 7:1, 11)

- Awake, awake, stand up, O Jerusalem, which hast drunk at the hand of the Lord the cup of his fury—thou hast drunken the dregs of the cup of trembling wrung out. (2 Nephi 8:17)

- Their land is also full of idols; they worship the work of their own hands. . . . And the mean man boweth not down, and the great man humbleth himself not, therefore, forgive him not. O ye wicked ones, enter into the rock, and hide thee in the dust, for the fear of the Lord and the glory of his majesty shall smite thee. (2 Nephi 12:8–10)

- For Jerusalem is ruined, and Judah is fallen, because their tongues and their doings have been against the Lord, to provoke the eyes of his glory. The show of their countenance doth witness against them, and doth declare their sin to be even as Sodom. . . . Wo unto their souls, for they have rewarded evil unto themselves! . . . They shall eat the fruit of their doings. (2 Nephi 13:8–10)

- They understood not; . . . they perceived not. . . . [therefore] cities be wasted without inhabitant, and the houses without man, and the land be utterly desolate; . . . there shall be a great forsaking in the midst of the land. (2 Nephi 16:9, 11–12)

- There is no light in them. . . . They shall look unto the earth and behold trouble, and darkness. (2 Nephi 18:20, 22)

- The people turneth not unto him. . . . Therefore will the Lord cut [them] off. . . . Every one of them is a hypocrite and an evildoer. (2 Nephi 19:13–14, 17)

- Every one that is proud shall be thrust through; yea, and every one that is joined to the wicked shall fall by the sword. Their children also shall be dashed to pieces; . . . their houses shall be spoiled and their wives ravished. . . . And Babylon . . . shall be as when God overthrew Sodom and Gomorrah. It shall never be inhabited, neither shall it be dwelt in from generation to generation: . . . For I will destroy her speedily. . . . The wicked shall perish. (2 Nephi 23:15–16, 19–20, 22)

- They will be drunken with iniquity and all manner of abominations—and when that day shall come they shall be visited of the Lord of Hosts, with thunder and with earthquake, and with a great noise, and with storm, and with tempest, and with the flame of devouring fire. . . . For behold, the Lord hath poured out upon you the spirit of deep sleep. For behold, ye have closed your eyes, and ye have rejected the prophets; and your rulers, and the seers hath he covered because of your iniquity. . . . The learned shall not read them [words of the Book of Mormon], for they have rejected them. (2 Nephi 27:1, 2, 5, 20)

Obedience, Gathering, Prospering, and Mercy

- Nevertheless, for my name’s sake will I defer mine anger, and for my praise will I refrain from thee, that I cut thee not off. For, behold, I have refined thee, I have chosen thee in the furnace of affliction. . . . Come ye near unto me. . . . Go ye forth of Babylon. (1 Nephi 20:9–10, 16, 20)

- Thou art my servant, O Israel, in whom I will be glorified. . . . I will preserve thee, and give thee my servant for a covenant of the people, to establish the earth, to cause to inherit the desolate heritages . . . They shall not hunger nor thirst, neither shall the heat nor the sun smite them; for he that hath mercy on them shall lead them, even by the springs of water shall he guide them. . . . I will lift up mine hand to the Gentiles, and set up my standard. . . . And I will save thy children. (1 Nephi 21:3, 8, 10, 22, 25)

- And the Lord is near, and he justifieth me. Who will contend with me? Let us stand together. . . . For the Lord God will help me. (2 Nephi 7:8–9)

- Look unto the rock from whence ye are hewn. . . . Look unto Abraham . . . and unto Sarah. . . . For the Lord shall comfort Zion, he will comfort all her waste places; and he will make her wilderness like Eden, and her desert like the garden of the Lord. Joy and gladness shall be found therein, thanksgiving and the voice of melody. . . . The redeemed of the Lord shall return, and come with singing unto Zion; and everlasting joy and holiness shall be upon their heads; and they shall obtain gladness and joy; sorrow and mourning shall flee away. (2 Nephi 8:1–3, 11)

- And it shall come to pass in the last days, when the mountain of the Lord’s house shall be established in the top of the mountains, and shall be exalted above the hills, and all nations shall flow unto it. And many people shall go and say, Come ye, and let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, to the house of the God of Jacob; and he will teach us of his ways, and we will walk in his paths; for out of Zion shall go forth the law, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. (2 Nephi 12:2–3)

- In that day shall the branch of the Lord be beautiful and glorious; the fruit of the earth excellent and comely to them that are escaped of Israel. . . . They that are left in Zion and remain in Jerusalem shall be called holy. . . . And the Lord will create upon every dwelling-place of mount Zion . . . a cloud and smoke by day and the shining of a flaming fire by night; for upon all the glory of Zion shall be a defence. And there shall be a tabernacle for a shadow in the daytime from the heat, and for a place of refuge, and a covert from storm and from rain. (2 Nephi 14:2–3, 5–6)

- There shall be a tenth, and they shall return. (2 Nephi 16:13)

- A virgin shall conceive, and shall bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel. (2 Nephi 17:14)

- For God is with us. . . . Neither fear . . . nor be afraid. . . . Sanctify the Lord of Hosts himself, and let him be your fear, and let him be your dread. And he shall be for a sanctuary. (2 Nephi 18:10, 12–14)

- The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light. . . . Thou hast multiplied the nation, and increased the joy. . . . For thou hast broken the yoke of his burden. . . . For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given; and the government shall be upon his shoulder; and his name shall be called, Wonderful, Counselor, The Mighty God, The Everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace. Of the increase of government and peace there is no end. (2 Nephi 19:2–3, 6–7)

- O my people that dwellest in Zion, be not afraid. (2 Nephi 20:24)

- And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse. . . . And the Spirit of the Lord shall rest upon him, the spirit of wisdom and understanding, the spirit of counsel and might, the spirit of knowledge and of the fear of the Lord. . . . With righteousness shall he judge the poor. . . . They shall not hurt nor destroy in all my holy mountain, for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord. . . . And it shall come to pass in that day that the Lord shall set his hand again the second time to recover the remnant of his people which shall be left. . . . And he shall set up an ensign. . . . There shall be a highway for the remnant. (2 Nephi 21:1–4, 9, 11–12, 16)

- God is my salvation. . . . Jehovah is my strength. . . . With joy shall ye draw water out of the wells of salvation. (2 Nephi 22:2–3)

- For I will be merciful unto my people. (2 Nephi 23:22)

- For the Lord will have mercy on Jacob, and will yet choose Israel, and set them in their own land. . . . And it shall come to pass in that day that the Lord shall give thee rest, from thy sorrow, and from thy fear, and from the hard bondage wherein thou wast made to serve. . . . The Lord hath founded Zion. (2 Nephi 24:1, 3, 32)

- The Lord God shall bring forth unto you the words of a book. . . . And in the book shall be a revelation from God, from the beginning of the world to the ending thereof. . . . I am a God of miracles. . . . I will proceed to do a marvelous work among this people, yea, a marvelous work and a wonder. . . . The deaf hear the words of the book, and the eyes of the blind shall see out of obscurity and out of darkness. And the meek also shall increase, and their joy shall be in the Lord, and the poor . . . shall rejoice in the Holy One of Israel. (2 Nephi 27:6–7, 23, 26, 29–30)

- Surely he has borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows. . . . But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities; the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed. . . . By his knowledge shall my righteous servant justify many; for he shall bear their iniquities. . . . He shall divide the spoil with the strong; . . . and he bore the sins of many, and made intercession for the transgressors. (Mosiah 14:4–5, 11–12)

- For O how beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings, that is the founder of peace, yea, even the Lord, who has redeemed his people; yea, him who has granted salvation unto his people. (Mosiah 15:18)

- Then shall their watchmen lift up their voice, . . . for they shall see eye to eye. . . . Then will the Father gather them together again. . . . Then shall they break forth into joy. . . . The Father hath made bare his holy arm, . . . and all the ends of the earth shall see the salvation of the Father. . . . Awake, awake again, and put on thy strength, O Zion; put on thy beautiful garments. . . . And ye shall be redeemed without money. (3 Nephi 20:32–36, 38)

- I give unto you a sign. . . . A great and a marvelous work. . . . And they shall go out from all nations; and they shall not go out in haste, nor go by flight, for I will go before them, saith the Father, and I will be their rearward. (3 Nephi 21:1, 9, 29)

- Enlarge the place of thy tent, and let them stretch forth the curtains of thy habitations; spare not, lengthen thy cords and strengthen thy stakes. . . . And all thy children shall be taught of the Lord; and great shall be the peace of thy children. . . . In righteousness shalt thou be established. . . . Whosoever shall gather together against thee shall fall for thy sake. (3 Nephi 22:2, 13–15)

Conclusion

Some students wonder why Nephi, Jacob, Abinadi, and finally Christ emphasized the words of Isaiah. Apparently, these prophets did so because the central messages of Isaiah support, enhance, and give depth to the central messages of the Book of Mormon. From Nephi’s teachings to Moroni’s final message—contained in Moroni 10 and on the title page—the authors of the Book of Mormon indicated that their purpose was “to the convincing of the Jew and Gentile that Jesus is the Christ” and that the house of Israel might know the “covenants of the Lord” (Book of Mormon title page). Nephi was the first prophet to provide the promise repeated often by subsequent Book of Mormon prophets: “Inasmuch as ye shall keep my commandments, ye shall prosper,” but “inasmuch as [ye] shall rebel . . . [ye] shall be cut off from the presence of the Lord” (1 Nephi 2:20–21). Later, Lehi made it clear that the promise to prosper meant that those who were obedient would prosper “in the land” (2 Nephi 1:20), referring at times to physical blessings, but most importantly to the spiritual ones. The promise of prospering “in the land” is related to scattering and gathering; it mirrors the biblical understanding of covenants connected to the promised land found in Deuteronomy 27–28. Thus, just as in Isaiah, Book of Mormon prophets saw Christ as the key that unlocked the power of the covenant. Israel’s acceptance or rejection of Christ and his covenant determined whether they would be scattered or gathered or whether they would be connected to or separated from the Lord. Isaiah’s use of the concepts of scattering and gathering undergird the doctrines of justice and mercy taught by Lehi, Jacob, Mosiah, Abinadi, Alma, Samuel, Mormon, Moroni, and Christ himself.

The writings of Isaiah are not included in the Book of Mormon as a test for beginning readers, as prophetic filler to increase book length, or as a challenge for those at an advanced level of scriptural understanding. They exist in the Book of Mormon because they support its main messages in beautiful and poetically profound ways. Indeed, it could be argued that the early authors of the Book of Mormon understood the themes of scattering and gathering—meaning the doctrines of justice and mercy—so well because they had first absorbed the central messages in the writings of Isaiah. This deep understanding of Isaiah allowed them to focus on the most important concepts in God’s plan for his people and to teach them in plainness and simplicity. An understanding of the writings of Isaiah solidifies, deepens, and focuses students’ testimonies of the Book of Mormon, allowing them to “rejoice in Christ” (2 Nephi 25:26) and in the blessings provided for those who make and keep covenants with him.

Notes

[1] Boyd K. Packer, “The Things of My Soul,” Ensign, May 1986, 59. Mark Twain once infamously called the Book of Mormon “chloroform in print.” Twain’s comment is likely a pun on the Book of Ether. Nevertheless, as the full quote indicates, he was referring to the entire Book of Mormon. “The book is a curiosity to me, it is such a pretentious affair, and yet so ‘slow,’ so sleepy; such an insipid mess of inspiration. It is chloroform in print. If Joseph Smith composed this book, the act was a miracle—keeping awake while he did it was, at any rate.” Mark Twain, Roughing It (NY: Harper & Brothers, 1904), chapter 16. The drama of leaving Jerusalem and the adventures of retrieving the brass plates, finding wives, surviving in the wilderness for eight years, building a ship, and sailing across the sea could not be what he found so soporific; the Isaiah chapters are perhaps a better candidate for his lack of interest. On the other hand, the challenge of reading Isaiah may not have been as significant in the early years of the restoration of the Church. As demonstrated by the Puritans, early American settlers knew the Old Testament and desired to form covenant “new Israel” communities. Early Latter-day Saint convert Parley P. Pratt mentions reading the entire Book of Mormon from beginning to end without stopping. Elder Pratt was a preacher for the “Campbellite” or Disciples of Christ movement and was well-acquainted with Old Testament prophetic passages. During the nineteenth century, Old Testament reading decreased as more emphasis was placed on the New Testament, creating an increasingly large barrier to understanding Isaiah for many.

[2] Karel Van Der Toon has suggested that the study of Isaiah was an important text in Judah’s scribal school, which could help explain Nephi’s familiarity with the text and his propensity for citing Isaiah’s writings so frequently as the basis of his own writings. Nephi’s considerable writing abilities are demonstrated in the way he uses this external source as a springboard for his own ideas. See Karel Van der Toorn, Scribal Culture and the Making of the Hebrew Bible (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007), 101–2, as discussed in Brandt A. Gardner, “Musings on the Making of Mormon’s Book: Preliminary, Nephi As Author,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture; http://

[3] Victor L. Ludlow, Unlocking Isaiah in the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 13–15; see also Victor L. Ludlow, “God’s Covenants and Promises to the House of Israel,” in Book of Mormon Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 342.

[4] For example, other important Latter-day Saint studies include, but are not limited to, Victor L. Ludlow, Isaiah: Prophet, Seer, and Poet (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1982); Unlocking Isaiah in the Book of Mormon; Donald W. Parry, Jay A. Parry, and Tina M. Peterson, Understanding Isaiah (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1998); Donald W. Parry and John W. Welch, Isaiah in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998); Donald W. Parry, Harmonizing Isaiah: Combining Ancient Sources (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2001); David R. Seely, “Nephi’s Use of Isaiah 2–14 in 2 Nephi 12–30,” Isaiah in the Book of Mormon, 151–71; Avraham Gileadi, The Book of Isaiah: A New Translation with Interpretive Keys from the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1988); Ann N. Madsen, “What Meaneth the Words That Are Written? Abinadi Interprets Isaiah,” Journal of Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 10, no. 1 (2001): 4–14; Monte S. Nyman, Great Are the Words of Isaiah (Springville, UT: Horizon Publishers, 2009); David J. Ridges, Isaiah Made Easier: In the Bible and the Book of Mormon (Springville, UT: Bonneville Books, 2002); John Bytheway, Isaiah for Airheads (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006); Philip J. Schlesinger, Isaiah and the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: P. J. Schlesinger, 1990); Mark Swint, Compare Isaiah: Understanding Biblical Scriptures in the Book of Mormon (Springville, Utah: Horizon, 2009); H. Clay Gorton, The Legacy of the Brass Plates of Laban: A Comparison of Biblical & Book of Mormon Isaiah Texts (Bountiful, UT: Horizon Publishers, 1994); Sidney Sperry, “The Isaiah Problem in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 4, no. 1 (1995): 129–52. While all of these studies have unique views of the Isaiah texts in the Book of Mormon, and contribute to an LDS understanding of these sections, of special mention are works by Victor Ludlow for their strong attention to historical context; works by Donald Parry, with their careful focus on intertextuality and other comparative textual considerations; the chapter by David Seely for its thematic linking of 2 Nephi 12–24; and the work of Avraham Gileadi, which is a new translation of Isaiah into modern English that relies on the Book of Mormon’s use of Isaiah.

[5] This is a revelation of God before his throne and sometimes accompanies the calling of a prophet. For further discussion, see Daniel C. Peterson and Steven D. Ricks, “The Throne Theophany/

[6] The Book of Mormon and KJV differ slightly in verse 9. The KJV is written in the present tense without pronouns; however, the Book of Mormon passage is in the past tense with pronouns that identify who is at fault— “they,” meaning the people, not Isaiah or God (2 Nephi 16:9; Isaiah 6:9).

[7] Nevertheless, Nephi prophesied that after the marvelous work and a wonder comes forth that “the deaf hear the words of the book, and the eyes of the blind shall see out of obscurity and out of darkness” (2 Nephi 27:29), a reversal of the curse upon the hard-hearted.

[8] It is evident throughout the scriptures that prophets were often considered outsiders belonging to a minority group deemed heretics (see 3 Nephi 10:15–16). Nephi preceded his quoting of Isaiah’s symbolic prophecies by first reciting the clearly-worded predictions about the “very God of Israel” by the prophets Zenock, Neum, and Zenos (1 Nephi 19:7). He would be “lifted up,” “crucified,” and “buried in a sepulchre” with signs in the heavens and earth at his death (1 Nephi 19:10–12). Lehi was mocked and almost killed by the people in Jerusalem for his teachings—not only did he testify of their wickedness and abominations, he also “manifested plainly of the coming of a Messiah” (1 Nephi 1:19–20), suggesting that clearly teaching about the anointed one could arouse murderous opposition. Just as Lehi’s plain testimony enraged the Jews of his day (see 1 Nephi 1:20), their plain and bold testimonies had earlier caused Zenock to be stoned and Zenos to be killed (see Alma 33:17; Helaman 8:19; 3 Nephi 10:15–16). Interestingly, the only portions of the writings by Zenock, Neum, and Zenos that have survived are those quoted by Nephi and other Book of Mormon prophets (see, in addition to the above, Jacob 5; Alma 33:3–17). Their prophecies were taken from the original record of the Jews (see 1 Nephi 13:24–29; Jacob 4:14, emphasis added) and will only come forth in their entirety when the brass plates or other sacred writings become available (see 1 Nephi 5:17–18; 13:39).

[9] Interestingly, in Matthew 13:14–15, Jesus refers to the same verses of Isaiah as those quoted by Nephi and alluded to by Jacob (see previous paragraph in paper). Jesus uses this section of Isaiah to explain why he is speaking in parables, so that only the spiritually mature will hear and understand. Jesus’s understanding of the purpose of parables, then, forms a helpful parallel to Nephi and Jacob’s understanding and use of Isaiah.

[10] Victor L. Ludlow, Isaiah: Prophet, Seer, and Poet (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1982), 32.

[11] Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, writing of Isaiah’s manner of prophesying, stated: “These parallel prophecies with application in more than one age create much of the complexity in Isaiah, but they also provide so much of the significance and meaning that his writings contain.” Jeffrey R. Holland, Christ and the New Covenant (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1997), 78.

[12] Exegesis is the process of “reading out of” a text the original meaning; whereas eisegesis is “reading in” to the text one’s own preconceived notions and is not the same as “likening.” Understanding how a principle applies to “them, there, then” helps correctly apply to “us, here, now.” See Eric D. Huntsman, “Teaching through Exegesis: Helping Students Ask Questions of the Text,” Religious Educator 6, no. 1 (2005): 108–10.

[13] Nibley, “Great Are the Words of Isaiah,” 224.

[14] Students frequently hurry to make modern application of Isaiah; however, latter-day prophets have elucidated both ancient and modern meanings of passages of Isaiah that support the process of first understanding their original meanings and then seeing how other prophets have applied them. For example, Jeffrey R. Holland explained in his October 2000 general conference address the ancient meanings of the Lord’s admonition “be ye clean, that bear the vessels of the Lord” (Isaiah 52:11) and then made application to latter-day priesthood bearers. In this talk, Elder Holland explained that this scripture referred to “the recovery and return to Jerusalem of various temple implements that had been carried into Babylon by King Nebuchadnezzar. In physically handling the return of these items, the Lord reminded those early brethren of the sanctity of anything related to the temple. . . . They themselves were to be as clean as the ceremonial instruments they bore.” He also quoted the Apostle Paul, writing to Timothy, “If a man . . . purge himself [of unworthiness], he shall be a vessel . . . sanctified, and meet for the master’s use, and prepared unto every good work.” Therefore, Paul says, “Flee . . . youthful lusts: but follow righteousness . . . with them that call on the Lord out of a pure heart” (2 Timothy 2:21–22). Following the explanation of Old Testament and New Testament usages of the phrase, Elder Holland applied the scripture to latter-day priesthood bearers: “In both of these biblical accounts the message is that as priesthood bearers not only are we to handle sacred vessels and emblems of God’s power—think of preparing, blessing, and passing the sacrament, for example—but we are also to be a sanctified instrument as well. Partly because of what we are to do but more importantly because of what we are to be: . . . clean.” Jeffrey R. Holland, “Sanctify Yourselves,” Ensign, November 2000, 38–39.

[15] See, for example, Matthew 1:22–23; 2:13; and 2:17–18. For modern examples almost any talk from general conference will show numerous examples of a modern message built upon the doctrines and principles provided in the scriptures by ancient prophets. Although prophets are not obligated to support their statements from the writings of other prophets, this process of connecting the prophetic voice over generations demonstrates that the doctrines of the gospel do not change.

[16] To help make clear the central messages of each Isaiah passage, Book of Mormon prophets consistently employed a “formula quotation pattern” when quoting Isaiah’s prophecies. John Gee calls this pattern a “verbal paradigm.” Gee, “‘Choose the Things That Please Me’: On the Selection of the Isaiah Passages in the Book of Mormon,” in Isaiah in the Book of Mormon, 77. This pattern begins with an introduction in which the prophet clearly teaches principles regarding the gathering and scattering of the house of Israel, the blessings associated with keeping covenants and the importance of turning to the Messiah, the Holy One of Israel, who is later explicitly identified as Jesus Christ, the Son of God (see 2 Nephi 10:3; 25:19). Then, after quoting an extended passage of Isaiah, the Book of Mormon prophet explained the passage, prophetically likening it to his people, both in his own time and in the latter days. Nephi specifically identified this interpretive and authoritative explanation as a form of prophecy (see 2 Nephi 31:1).

[17] The stronger warnings against wickedness provided in earlier chapters of Isaiah were saved for inclusion in Nephi’s recording of Nephite life after arriving in the promised land.

[18] S. Kent Brown, From Jerusalem to Zarahemla (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1998), 10.

[19] When the house of Israel came into the promised land, Joshua directed the ceremony prescribed by Moses. From Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal the blessings promised in the law and the curses that would be Israel’s if she were not true to her covenants were reenacted in dramatic fashion. Scattering “among all people, from the one end of the earth even unto the other” was one of the warnings (Deuteronomy 28:64).

[20] Ludlow, Isaiah: Prophet, Seer, and Poet, 422.

[21] Nephi and Jacob incorporated the words of Isaiah for both public and private reasons. While they both attempted to increase the people’s faith in the Holy One of Israel, the prophecies also comforted them in the knowledge that eventually their nation, Judah, would be destroyed. (Brown, From Jerusalem to Zarahemla, 9). For a different interpretation, see John Gee and Matthew Roper, “‘I Did Liken All Scriptures unto Us’: Early Nephite Understandings of Isaiah and Implications for ‘Others’ in the Land,” in Fullness of the Gospel: Foundational Teachings of the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2003), 51–65.

[22] Holland, Christ and the New Covenant, 165.

[23] These are similar to the three purposes Ludlow identified as reasons Book of Mormon prophets quoted Isaiah. (Ludlow, Unlocking Isaiah in the Book of Mormon, 13).

[24] It should be acknowledged that the title page refers to the “covenants of the Lord,” and does not specifically name the Abrahamic covenant. However, the Book of Mormon prophets came from a biblical context in which the covenant was initiated with Abraham (see Genesis 17:3–8), renewed with Jacob or Israel (see Genesis 35:9–15), and renewed again with Moses and the children of Israel under the law of Moses (see Exodus 19:5–6; Deuteronomy 28:1–2), providing the Israelites with consistent demonstrations that God had chosen them forever for specific purposes, and would thus continue to fulfill his purposes through the house of Israel in the future. The book of Deuteronomy (specifically Deuteronomy 26–30) records Moses’ further development of this covenant to specify the theme of scattering due to disobedience and future gathering due to forgiveness. The expression of this covenantal theme in the title page of the Book of Mormon states that the children of Israel “are not cast off forever.” When this paper refers to the Abrahamic covenant, it does so from a modern Latter-day Saint viewpoint that includes all of God’s biblical covenants with Israel as his chosen people. This viewpoint is consistent with the message of the books of Moses—Genesis through Deuteronomy—and is consistent with the biblical understanding that would have been inherited by the Nephites, even if they did not always refer to the covenants of the Lord as the Abrahamic covenant, as is typically done today. Salvation as the fruit of sacred covenants has its earliest roots in the Garden of Eden. Adam and Eve were expelled from Eden after they had entered into covenant with God and were clothed in garments that symbolized the promise of redemption. In the broadest sense, however, the covenant of salvation reaches back to premortality and is called the new and everlasting covenant, entered into anew in mortality, and restored anew in each dispensation. Doctrine and Covenants 132:11 declares that it was a law “ordained unto you, before the world was.” Robert L. Millet and Joseph Fielding McConkie, Our Destiny: The Call and Election of the House of Israel (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1993), 13–14.

[25] See John Gee, “‘Choose the Things That Please Me’: On the Selection of the Isaiah Passages in the Book of Mormon,” in Isaiah in the Book of Mormon, 73, 86: “The Isaiah sections are not simple filler, but an integral part of Nephi’s, Jacob’s, Abinadi’s, and Christ’s discourses, which all serve to fulfill the Book of Mormon’s stated purpose.” See also Gee and Roper, “‘I Did Liken All Scriptures unto Us,’” 51–65.

[26] Elder Bruce R. McConkie made this comment regarding scattering: “They [Israel] were scattered because they forsook the Abrahamic covenant, trampled under their feet the holy ordinances, and rejected the Lord Jehovah, who is the Lord Jesus, of whom all the prophets testified. Israel was scattered for apostasy.” A New Witness for the Articles of Faith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1985), 515.

[27] One could further liken this dichotomy to natural man and redeemed man, following the central gospel principles of the Fall and Atonement (2 Nephi 2:4, 10).

[28] Robert J. Matthews, “Abinadi: the Prophet and Martyr,” in The Book of Mormon: Mosiah, Salvation Only Through Christ, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1991), 91–111.

[29] John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 139–210.

[30] “Behold, I and the children whom the Lord hath given me are for signs and for wonders in Israel from the Lord of hosts, which dwelleth in mount Zion” (Isaiah 8:18).

[31] Joseph Smith declared that the “everlasting covenant was made . . . before the organization of this earth and relates to their dispensation of things to men on the earth.” Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saint, 2007), 42. Additionally, the Doctrine and Covenants states: “Behold, here is the agency of man, and here is the condemnation of man; because that which was from the beginning is plainly manifest unto them, and they receive not the light” (D&C 93:31) and “Even before they were born, they, with many others, received their first lessons in the world of spirits and were prepared to come forth in the due time of the Lord to labor in his vineyard for the salvation of the souls of men” (D&C 138:56). Joseph McConkie clarified, “No one in this mortal sphere will ever be taught any principle of truth that was not first known to him or her in the premortal estate.” Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler, Revelations of the Restoration (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 680; see also n. 23.

[32] Although we have not called this a chiasmus, for a discussion of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon, see John W. Welch, “The Discovery of Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon: Forty Years Later,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 16, no. 2 (2007): 74–87. In Illustration 3, the “chiastic” pattern shown is not necessarily intended to portray a purposeful creation of a chiasmus by Isaiah, since it is not clear what form these texts originally took or precisely when the chapters came to hold their current place and order in the book of Isaiah. However, these chapters as used by Nephi in the Book of Mormon do exhibit a balance that effectively demonstrates the related concepts of scattering and gathering. While an awareness of this balance can be a helpful learning tool for modern students, and may have been intended as a teaching tool by Nephi, there is no way of knowing whether Nephi would have necessarily seen the text in this way, as has been stated in the paper. Nor should this balance be taken as an additional evidence of the ancient Near Eastern context of the Book of Mormon, as may appropriately be done with clearer evidences of chiasmus elsewhere in the Book of Mormon text. For a discussion of the appropriate identification of chiasmus, see John W. Welch, “Criteria for Identifying and Evaluating the Presence of Chiasmus,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 4, no. 2 (1995): 1–14. He states, “Some texts are strongly and precisely chiastic, while in other cases it may only be possible to speak of a general presence of balance or framing. From these studies it is apparent that all possible chiasms were not created equal and that in order to be clear in discussing chiasmus it is necessary for commentators to recognize that ‘degrees of chiasticity’ exist from one text to the next” (p. 1).

[33] As demonstrated in the illustration, chapters 15 and 21 balance each other (shown as lines D and D'), both discussing an ensign that would be lifted up. Although the ensign is clearly positive in chapter 21, the interpretation is not so clear in chapter 15. Some modern LDS commentary (including the chapter heading provided in the Book of Mormon for 2 Nephi 15) identify the ensign as one that will gather Israel in the last days, but Isaiah’s own audience in his day probably understood this as the ensign of a conquering army, coming to destroy the wicked of the Israelites and carry them away into captivity in another land.

[34] Although this view of 2 Nephi 12–24 is an original contribution in this article, we would also like to acknowledge an unpublished paper by J. David Gowdy, “The Isaiah Chapters in the Book of Mormon (2 Nephi 12–24): A Chiasmus.” We were introduced to Gowdy’s paper after having submitted this article for publication. It is also interesting to note that the structure of Isaiah chapters 2–12 is clear enough to have caused at least one non-LDS scholar to approach it as a unit, which he calls “The Book around Immanuel.” See Andrew H. Bartelt, The Book around Immanuel, in Biblical and Judaic Studies 4 (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1996).

[35] The promise of Immanuel is an instance of dual prophecy, in which Isaiah apparently referred to one of his own children to be born of his wife while also prophesying of a future child to miraculously be born. Elder Jeffrey R. Holland has stated: “The dual or parallel fulfillment of this prophecy comes in the realization that Isaiah’s wife, a pure and good young woman—symbolically representing another pure young woman—did bring forth a son. This boy’s birth was a type and shadow of the greater and later fulfillment of that prophecy, the virgin birth of the Lord Jesus Christ. The dual fulfillment here is particularly interesting in light of the fact that Isaiah’s wife apparently was of royal blood, and therefore her son was of the royal line of David. Isaiah’s son is thus the type, the prefiguring, of the greater Immanuel Jesus Christ, the ultimate King who would be born of a literal virgin.” Jeffrey R. Holland, “‘More Fully Persuaded’: Isaiah’s Witness of Christ’s Ministry,” in Isaiah in the Book of Mormon, 6.