Three Stories

Charles Swift

Charles Swift, “Three Stories,” in My Redeemer Lives! ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011).

Charles Swift was an associate professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University when this article was published.

Ever since I was a small child, I have been in awe of stories. I am amazed by the power they have to ignite our imaginations, teach us truths, and help us feel. When I was asked to participate in this wonderful Easter Conference, I knew that I had to speak about something to do with the story of Jesus. Often when we study the scriptures, we focus on teachings that are directly conveyed by the Savior in sermons or in conversations with disciples and others. There is nothing wrong with carefully studying such passages, of course; we can learn much that is important when the Savior preaches directly to his listeners or indirectly to us readers, such as in the Sermon on the Mount. When we read “Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy” (Matthew 5:7), we clearly understand the importance of mercy and realize that if we wish to have mercy extended to us, we need to extend it to others. However, we do not need to concentrate on the declarative in scripture at the expense of the narrative. While declarative statements in the scriptures certainly teach truth, we must remember that the stories teach truth as well. Such passages as the Sermon on the Mount are few and far between in the Gospels; most of what we are given is story. We can often learn more about mercy, for example, from experiencing a story of it in the Gospels than by reading statements about it.

The story of the Savior, as told in the Gospels, is not just any story. It is not a story created by people, though there is the element of humanity in the telling of it. It is a true story, not fabricated. But it is not just any true story. It is important to understand that it is a story with a transcendent purpose; it is not told simply for the sake of telling it. The story of Jesus is not meant to entertain or even to merely enlighten: the story of Jesus bears witness. This unique story bears witness of Jesus as the Christ, the Savior of all humanity. It is a story, a true story, the True Story.

I have decided to choose one chapter in one of the Gospels and take a close look at the stories there. Matthew 14 tells us three stories—two that are very well known, the feeding of the five thousand and the Savior and Peter walking on water, and one that is not as frequently discussed, in which many are healed by touching the Savior’s garment. The chapter begins with an account of the Lord being told about the death of John the Baptist, but I will not discuss that account because the Savior is not the central figure.

Before I discuss these three stories, I believe it would be helpful to briefly explain what approach I am taking. First, I am staying with the King James Version of the Bible. Rather than being concerned about such issues as original authorship or the original meaning of the Greek, I am focusing on how a careful reader might understand the King James Version of these three stories without outside sources. I am looking at the text as given in the King James English, concentrating not on what the writer may or may not have intended but on what the reader can reasonably perceive. This approach is in harmony with the reader-response theory in literature with its focus on the thoughts of the reader when encountering the text. [1] That leads me to my second point: this paper is not an analysis of what scholars or other thinkers have said about these stories. Instead, I will be doing what is often called a close reading, in which the reader carefully explores what the text is saying by studying the text itself very closely. [2]

Discussing this approach in literary terms may seem foreign to many, but this approach shares common ground with what we often do in studying the scriptures. While we care about what the scriptures say, we also recognize that the reader can find meaning in them that may not have necessarily been intended by the original author. As Elder Dallin H. Oaks teaches, “The idea that scripture reading can lead to inspiration and revelation opens the door to the truth that a scripture is not limited to what it meant when it was written but may also include what that scripture means to a reader today. Even more, scripture reading may also lead to current revelation on whatever else the Lord wishes to communicate to the reader at that time. We do not overstate the point when we say that the scriptures can be a Urim and Thummim to assist each of us to receive personal revelation.” [3]

This is a wonderful insight that can prove to be very fruitful in studying the scriptures. While we are interested in what the writer originally intended, we are not limited to that, and we must admit that we often cannot fully determine what the writer was thinking either. However, we can know what we are experiencing as we carefully study the text and respond to it. This approach does not open the door to any and all interpretations that a reader might imagine; the text needs to reasonably support the reader’s understanding of it. But this approach does open the door to a much broader understanding of the scriptures that helps us to see them as living texts.

Now, let us turn our attention to the first of the three stories in Matthew 14.

Feeding the Five Thousand

After the disciples bury the body of John the Baptist and tell the Lord about his death, Matthew tells us that Jesus “departed thence by ship into a desert place apart” (Matthew 14:13; unless otherwise noted, all references are to Matthew 14, so hereafter only the verse will be cited). Notice how sparing the description of the action is. The writer leaves it to us to wonder what was going through the Lord’s mind and heart, the grief he was experiencing. So often the mark of powerful literature is not so much what is said but what is not said. The good writer knows the power of imagination and often writes just enough to engage our thoughts and let us imagine what is happening and why it is happening. When the people hear that he has gone to a desert place, presumably to be alone and most likely to pray and commune with his Father over the death of John, “they followed him on foot out of the cities. And Jesus went forth, and saw a great multitude, and was moved with compassion toward them, and he healed their sick” (vv. 13–14). I am struck by the Savior’s selflessness in this terrible situation. He has heard of his cousin’s death, of the death of the prophet who prepared the way for the Lord’s own ministry, of whom the Lord said, “Among them that are born of women there hath not risen a greater than John the Baptist” (Matthew 11:11). This news has apparently caused Jesus to want to be alone and contemplate what has occurred. Yet, when all these people follow him, he does not send them away, nor does he simply tolerate their presence, but he has compassion toward them and heals their sick.

Again, Matthew does not offer us the details. He does not tell us how the Lord heals the sick or how long it takes him to do so, but “when it was evening,” his disciples go to him and say, “This is a desert place, and the time is now past; send the multitude away that they may go into the villages, and buy themselves victuals” (v. 15). This is quite reasonable counsel. They are in an uninhabited place, it is late, and they do not have enough food to feed the thousands of people there, so it makes sense to send them to the villages so they can eat. There is nothing in the text to indicate that the people expect to be fed. And they have just experienced the wondrous miracle of the Lord healing their sick. Surely they can return to their homes now, content that the Lord has treated them with the greatest of kindness and generosity.

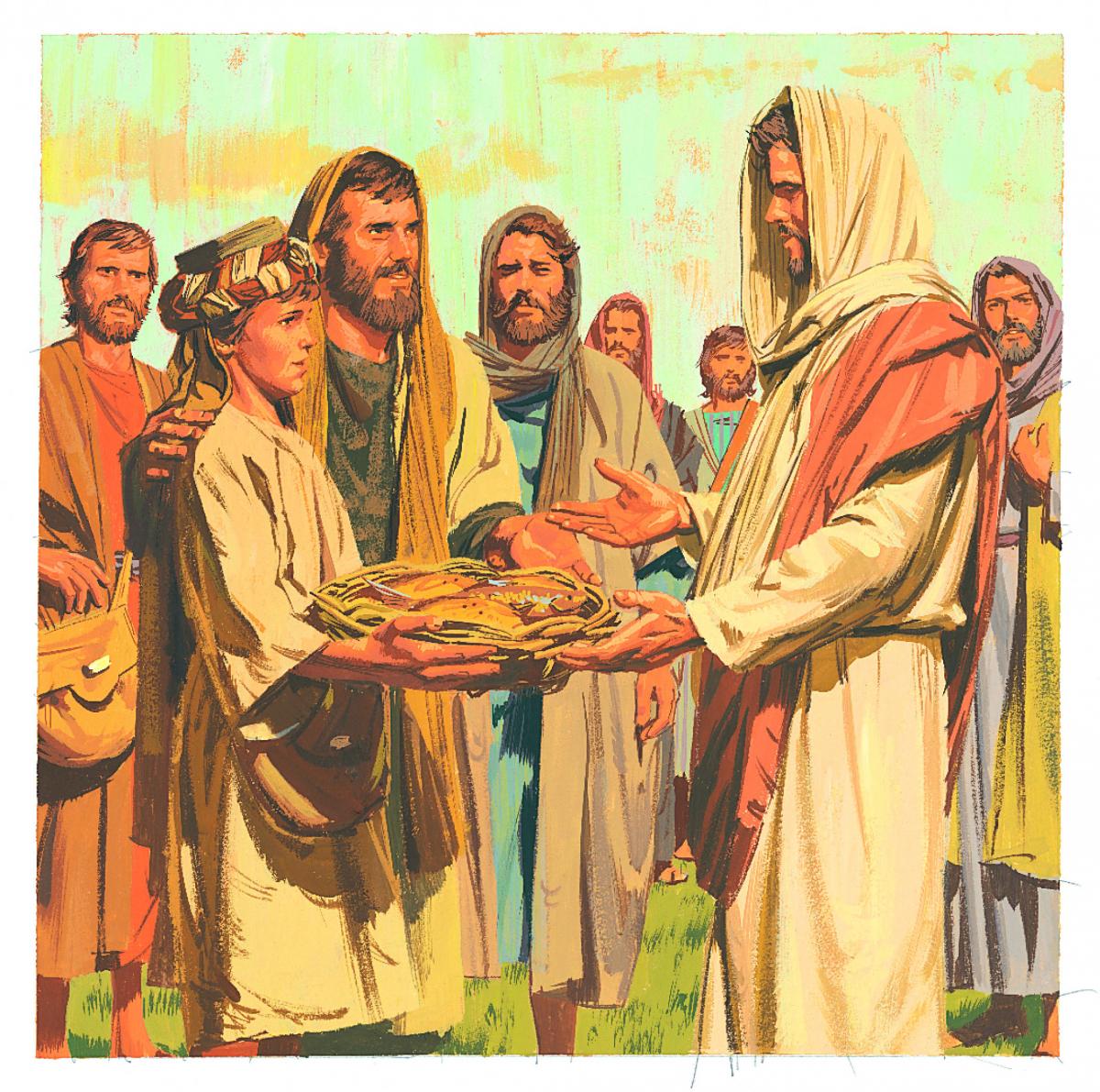

But Jesus tells the disciples, “They need not depart; give ye them to eat” (v. 16). It is easy to overlook this simple direction from the Lord. If we are not careful, we may see it as nothing more than a bit of dialogue in the middle of the story of a miracle. We may think that the purpose of the story is simply to teach us that Jesus could perform miracles by giving us an example of one. However, while Matthew leaves out details that we may think could be important, such as what exactly the Savior was going to do when he went to the “desert place,” we need to approach the text as though any detail Matthew does include is important. What might this line of dialogue tell us about the Savior, beyond the fact that he did not want the people to leave but to feed them instead? How often, for example, do modern disciples of Christ, weary from a long Sabbath day of service, have yet one more person come to them in need? It may be a member of the ward, someone not of our faith, or perhaps even a spouse or a child. It may be that the Spirit will whisper to that disciple, “Do not send them away, but feed them.”

Jesus tells the disciples, "They need not depart; give ye them to eat." (Paul Mann, © 1991 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.)

Jesus tells the disciples, "They need not depart; give ye them to eat." (Paul Mann, © 1991 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.)

“We have here but five loaves, and two fishes,” his disciples say. “Bring them hither to me,” he responds (vv. 17–18). It is as though he is saying to you and me through this story, “Bring to me what you have. It does not matter what you have, nor does it matter how much you have. Just bring it to me. But bring it all to me, without holding anything back.” I sense from this story that if the disciples had had only two loaves and one fish, it would not have mattered. I imagine the Lord would have been able to perform the miracle of feeding thousands of people if there were less than five loaves and two fishes. Likewise, if the disciples had had ten loaves and five fishes, I do not imagine he would have told them only to bring five and two. The significance is not how much the disciples had but that they were willing to give all that they had.

“And he commanded the multitude to sit down on the grass, and took the five loaves, and the two fishes, and looking up to heaven, he blessed, and brake, and gave the loaves to his disciples, and the disciples to the multitude” (v. 19). What can we learn from the action of this story? When we bring all that we have to the Lord, he draws down the powers of heaven and blesses what we have given. He uses what we have presented to him not only to bless us but to bless others as well. I also think it is significant that he used his disciples to give the bread and fish to the thousands of people rather than doing it himself. He could have distributed the food himself, of course. But he unselfishly gave his followers the chance to receive the blessings of serving others. He teaches his disciples, the multitude, and us readers that denying someone else the blessings of service is not his way, even if a person might be able to get more done without including others. His is not a gospel of efficiency.

Another significant lesson we can learn from closely reading this text is how the Savior teaches those in the multitude who receive the food that receiving it from his servants is the same as receiving it from him. Whether the bread of life is given us directly by the Savior or by one of his servants, we are still nourished.

There is another aspect to this lesson, however. Servants are obligated to take what the Lord has given them and pass that—nothing more, nothing less—to the people. The Lord gave his disciples fish and bread to give the multitude; if they had put the fish and bread aside and given the people stones, then we cannot say that it is the same as if the Lord had given the stones to them. We must be sure that what we give others in the name of the Lord is what the Lord has given us to offer them. For example, we often quote part of a verse from the Doctrine and Covenants: “whether by mine own voice or by the voice of my servants, it is the same” (D&C 1:38). Quoting the verse in this way leaves the impression that if a person is a servant of the Lord and tells people something, it is the same as if the Lord had spoken to them, regardless of what the servant is saying. This is not the most careful of readings; we should all be servants of the Lord, but we are far from infallible, so it is not wise for anyone to think that they can take whatever we say as coming from the Lord simply because we are saying it.

It is imperative to read the entire verse: “What I the Lord have spoken, I have spoken, and I excuse not myself; and though the heavens and the earth pass away, my word shall not pass away, but shall all be fulfilled, whether by my mine own voice or by the voice of my servants, it is the same” (D&C 1:38). The full verse focuses on the Lord’s word: “though the heavens and the earth pass away, my word shall not pass away, but shall all be fulfilled.” If the Lord’s word is being spoken, it does not matter whether it is the Lord speaking or his servants speaking, it is still his word. It is the same. But it must be the Lord’s word that is being spoken in order for it to be the same. Just as the Lord gave his disciples bread and fish and they were responsible to pass what he gave them on to the people, so must all of us members of the Church, since we are all his servants, be sure we receive his word from him and pass that on to our listeners.

“And they did all eat, and were filled: and they took up of the fragments that remained twelve baskets full. And they that had eaten were about five thousand men, beside women and children” (vv. 20–21). Note that everyone ate. It was not that some ate while others remained hungry, but they all ate, and they were all filled. If we come to him and humbly, willingly receive what he has for us, he will not leave us wanting. No one who comes to him will be left without. But here is an even greater miracle: if we come to him with all that we have, we will leave with more than we came with originally. Note that the disciples came with five loaves of bread and two fishes but ended up with twelve baskets full of bread and fishes. And the multitude came with no food but were filled with food and left with more than they came with. It is clear from the story that some brought little and some brought nothing, but none was turned away, and all were filled and had even more left over. We do not have to bring the same thing to the Lord, nor do we have to bring the same amount; we just need to try to make sure it is all we have.

Walking on Water

The next story comes immediately after the miraculous feeding of those thousands of people. The Lord sends the people away and goes up a mountain by himself to pray. His disciples are on a ship that is being tossed about by the waves. Jesus comes to his disciples, walking on the sea. It is not just that this is an account of another miracle, though that is very important, but the specific act in itself is significant. The Savior is willing to enter troubled waters for his disciples. He does not stand on the shore, shouting directions or simply watching them deal with their troubles under the popular excuse that it will build their character. He comes to them.

“And when the disciples saw him walking on the sea, they were troubled, saying, It is a spirit; and they cried out for fear” (v. 26). They are disciples of Christ. They are close to him, they love him, they strive to follow him, yet they mistake who he is and what he is doing for them. He is reaching out to them, yet they are responding in fear.

“But straightway Jesus spake unto them, saying, Be of good cheer; it is I; be not afraid” (v. 27). The Lord counsels them to see him for who he is and find joy rather than fear. His coming to them, even across troubled waters and in a way they never expected, should be received with happiness and without fear.

“And Peter answered him and said, Lord, if it be thou, bid me come unto thee on the water. And he said, Come. And when Peter was come down out of the ship, he walked on the water, to go to Jesus” (vv. 28–29). This is a fascinating piece of the story. There are at least two possible interpretations regarding Peter’s comment, “Lord, if it be thou.” First, he could be saying this as a kind of test—not of the Lord, necessarily, but of the still-unknown spirit that is walking on the water. The disciples are afraid, thinking that the entity on the water is a spirit or ghost. The entity claims to be the Lord, but perhaps the disciples are still not certain. Peter may be saying, in effect, “If you truly are Jesus, then you should be able to command me to walk on water and, because of your power, I would be able to do so.” I do not think this interpretation requires that we readers think Peter is lacking in faith in the Lord but rather that he is not yet certain that the being on the water is who he claims to be.

A second possible interpretation is that Peter is saying, in effect, “Lord, because it is you, bid me come unto thee on the water.” This interpretation assumes that Peter accepts what the person on the water has said, that he is Jesus and that Peter wants to come to his Savior but feels he cannot without the Lord giving him power to do so by bidding him to come.

Regardless of the interpretation we choose for Peter’s comment, the Lord’s response is clear: “Come.” It is simple, concise, and direct. For me as a reader, it is also powerful, conveying a sense that the speaker can indeed make things happen by simply speaking. There is no uncertainty in that response. Jesus does not say, “Well, if you have enough faith, you can walk on water,” or, “If you have sufficiently prepared yourself, you can come to me on the water,” or, “If you are worthy, then it will work.” Each of those responses would sow doubt in the heart of Peter. Also, each of those responses would reflect doubt in the heart of the speaker, implying that he does not know if Peter has enough faith, or is prepared, or is worthy. They are the kinds of things someone would say who does not have power and authority, who is not sure if Peter really can walk on water even if he is called to do so. As this part of the story communicates so well, Jesus is not that kind of person. When he says the simplest of words, there is sufficient power for the most miraculous events to occur.

It is also significant that Peter speaks to Jesus about bidding him to come to him and that Jesus responds by telling him to come. Peter could have said, “Lord, if it be thou, tell me I can also walk on water.” And Jesus could have responded, “You can walk on water.” But then the dialogue would be about whether Peter can actually walk on water. The actual words that Jesus and Peter say, however, work together metaphorically to offer an important understanding of a disciple’s relationship to the Lord. Our desire should be to come unto Christ; if that is what we truly want, he will respond by inviting us to come.

There is an important phrase in this verse that is easy to overlook. When the text says that Peter is walking on the water, it includes the phrase “to go to Jesus.” It seems that it is an unnecessary phrase. Peter asked the Lord to bid him to come to him, and because the Lord responded by telling him to do so, so why include this phrase? Of course Peter is going to go to Jesus—that is the sole purpose of his stepping onto the water. And that is the point: using an unnecessary phrase is a flag to the reader to ask why the phrase was used, and, in the asking, the reader discovers another important truth conveyed in this brief story. What is the purpose of this miracle of Peter walking on the water? The same purpose as any other miracle: “to go to Jesus.” Whether the miracle be the healing of the sick or the raising of the dead or divine guidance in a time of adversity, ultimately the miracle is to bring us to the Lord. And, like Peter, we should not hesitate to go to the Lord right away. That should be the focus that guides our efforts.

The purpose of the miracle of Peter walking on the water is the same as any other miracle: "to go to Jesus." (Robert T. Barrett, © 1996 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.)

The purpose of the miracle of Peter walking on the water is the same as any other miracle: "to go to Jesus." (Robert T. Barrett, © 1996 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.)

“But when [Peter] saw the wind boisterous, he was afraid; and beginning to sink, he cried, saying, Lord, save me” (v. 30). Of course, Peter does not see the wind, but he sees the violent effects of the wind upon the water. He is actually walking on water at this point, but there are big waves and he becomes afraid. Note that he does not begin to sink and then become afraid; he fears, and then he begins to sink. Neither the winds nor the waves are sinking him: his fear is. Peter does not do what most people do when confronted with a difficult, perhaps even life-threatening problem: he does not start swimming. He does not turn to himself first, relying on his own abilities, strength, and knowledge. Instead, he immediately turns to the Lord for help—and not just for help, but to be saved. “Lord, save me” is the cry of every disciple in troubling times and one that can pertain to anything from immediate needs—physical, emotional, mental, or spiritual—to salvation and eternal life.

“And immediately Jesus stretched forth his hand, and caught him, and said unto him, O thou of little faith, wherefore didst thou doubt? And when they were come into the ship, the wind ceased” (vv. 31–32). There are several important details here worth looking at closely. Jesus did not hesitate to help Peter; he did not lecture him, try to teach him a lesson, or wait for him to take responsibility for his actions. He did not say, “If I help you, then I will have to help everyone.” He just helped him, saving him from his sinking fears. And he helped him immediately. Jesus stretched forth his hand to Peter; he did not require Peter to reach up to him. It is important that the text mentions only the Lord stretching forth his hand and catching Peter.

There is one element of these last two verses that is much more than a detail, however, and lends itself to important doctrinal insights. The Lord asks Peter, “O thou of little faith, wherefore didst thou doubt?” This is the first time the word doubt is used in this story. Matthew does not say that when Peter saw the “wind boisterous” he doubted; he said Peter “was afraid.” So which is it? Was Peter afraid or doubtful? I believe the answer lies in this basic reality of our lives: fear can lead to doubt. Peter feared the waves on the water, most likely fearing that he might drown, and this fear led to his doubting whether he could actually walk on water rather than sink. This is a fairly natural, common relationship in life. A clarinet student fears she will forget her music, so she doubts she will perform well during her recital. A young man fears that the girl he wants to ask out will refuse, so he doubts himself and decides to give up.

There is also a spiritual dimension to this relationship between fear and doubt. People can have doubts about Heavenly Father that actually have their roots in fear. And often in such cases it is helpful to ask oneself when confronted with a doubt, “What am I afraid of?” More than once, when I was a bishop of a freshman ward at BYU, a young man would tell me in an interview that he did not believe in the Book of Mormon or in Joseph Smith or even in the Savior. Of course, each young man was unique, each situation was different, and I tried my best to seek the guidance of the Holy Spirit in helping them. There were a few times, however, when there seemed to be a pattern in their thinking that led me to ask them how they would feel if the Church no longer allowed young people to serve missions. In such instances, the young man I would be interviewing would realize that he had mistaken fearing going on a mission with doubting that the restored gospel is true. Once we identified what the real issue was and he understood that he indeed had a testimony of the gospel, then we could discuss his concerns about going on a mission.

The Lectures on Faith teach that “those who know their weakness and liability to sin would be in constant doubt of salvation if it were not for the idea which they have of the excellency of God, that he is slow to anger and long-suffering, and of a forgiving disposition, and does forgive iniquity, transgression, and sin. An idea of these facts does away doubt, and makes faith exceedingly strong.” [4] Too many of us fear that we are weak and liable to sin, so we doubt that we can be saved. But we should quit focusing on our weaknesses and instead focus on the Savior’s strength. We will not be saved because we are so good; we will be saved because he is so good—so good that he performed the Atonement for our sakes. That truth does not give us license to stop keeping the commandments, but it reminds us that one of the commandments is repentance; in other words, the Lord has prepared a way for us despite our “weakness and liability to sin.” If Peter had concentrated on how the Lord could give him the power to even walk on water, instead of focusing on his fear that the waves could make him sink, he would probably have been able to walk across the water and into the Savior’s embrace without a problem.

“And when they were come into the ship, the wind ceased. Then they that were in the ship came and worshipped him, saying; Of a truth thou art the Son of God” (vv. 32–33). I love this closing statement of the story. The disciples on the ship worship Jesus, and, for the first time in Matthew, the disciples call him the Son of God. Matthew does not make clear why they worship him and proclaim him to be the Son of God at this particular point, however. Perhaps most readers assume they do so because they have just witnessed this amazing miracle: Jesus walking on the water. But I believe it is just as likely that they worship him and proclaim his divinity because of what they witnessed between him and Peter—the way Jesus reached out and saved him and brought him safely back to the ship. Walking on water is certainly a miracle to behold, but so is the Savior’s love.

Healing

The third story I would like to reflect on is the shortest. In fact, the other two miracles told about in this chapter are so significant and related in such relatively detailed stories that they tend to overshadow this brief account of an amazing event. After the ship arrives, Jesus and his disciples come to a land, “and when the men of that place had knowledge of him, they sent out into all that country round about, and brought unto him all that were diseased; and besought him that they might only touch the hem of his garment; and as many as touched were made perfectly whole” (vv. 35–36). It is easy for the reader to respect, even love the men of this land, so unselfish and generous as to want to be sure to bring the ill to the Lord so they could be healed. They could have gathered around Jesus to listen to his beautiful teachings as others had listened or to be miraculously fed as others had been fed, but their first concern was for the neediest among them. In fact, those needy were not even among them—the men had to seek them out. I like to picture them talking to Jesus, asking that their families and friends could simply touch the hem of his garment, as though they are careful to bother him as little as possible. The fact that all who touch his garment are healed speaks much about the power of the Savior and about the faith of those people.

This story reminds me of a story of my own from the week I was supposed to be baptized. After receiving several lessons, I told the missionaries I wanted to be baptized as soon as possible, and I met with the appropriate authority for my baptismal interview. The next day I became very ill. I was ill for the next few days, losing several pounds and not being able to keep any nourishment. I was only eighteen years old at the time, and my parents were very concerned. When they took me to the doctor, he told me that I could not be baptized that weekend, and my parents agreed. They thought I was just too ill to receive that ordinance. I was discouraged when I returned home, lying on the couch in our small living room and wondering what I could possibly do when everyone around me thought I should not be baptized. I did not want to postpone that all-important date, but I also knew that I was so ill that I had a hard time sitting up, let alone entering into a font. I was weak from not being able to eat or drink, but I could not rest knowing that I might not be able to get baptized on the following Saturday.

Then it occurred to me that there was something I might be able to do. I had heard something about priesthood blessings. I had never seen one given, I was not sure what they were, and I was not really sure who could give them or who could receive them; I just had a faint knowledge that such a thing existed. I called up my good friend who was going to baptize me on Saturday and asked if his father, a Melchizedek Priesthood holder, would be willing to give me a blessing even though I was not yet a member of the Church. I now know that not being a member of the Church would not present a problem to having a priesthood blessing, but at the time I had no idea. My friend did not know either, and he said that he would ask his father and call me back later.

I returned to the couch and prayed as I lay there. I did not know what to expect, but I felt that all my options were gone and that the only hope I had left was this thing called a priesthood blessing. I do not remember how much time passed, but the phone finally rang. It was my friend, telling me that his father would indeed be happy to give me a priesthood blessing and asking me when he and a companion should come over. At that moment something happened that to this day I cannot explain. It makes no sense, especially given how badly I wanted to receive a blessing and hopefully be healed, or at least get sufficiently better that I could be baptized. As soon as my friend said that I could have a blessing, I told him not to worry about it and that I no longer needed one. He was confused, of course, and asked me why I did not need one.

“I just needed to know that your father was willing to give me a priesthood blessing,” I told him. “That’s enough for me. I’ll be fine now.”

I hung up the phone and walked back to my couch, confused myself as to why I no longer felt the need for his father to come and give me a priesthood blessing. All I knew was that the second I found out that the Lord’s servant was willing to come to me and bless me in his name, I sensed that the blessing, in some way I did not understand, had just been given me by the Lord himself. Now, I have given many priesthood blessings since and have also received many; I am certainly not implying that priesthood blessings should not be given. But something was different that evening in a way that I still do not fully understand. It was as though all I had to do was simply touch the hem of his garment, and I would be made whole. From that moment on, I did get better, and I was able to baptized the following Saturday, Christmas morning.

I bear my witness that the story of the Savior is the greatest story ever told. It is a story that has power to change our lives forever, and for good. And it has that power because it is a true story.

Notes

[1] “Reader-response critics turn from the traditional conception that a text embodies an achieved set of meanings, and focus instead on the ongoing mental operations and responses of readers as their eyes follow a text on the page before them.” M. H. Abrams and Geoffrey Galt Harpham, A Glossary of Literary Terms, 9th ed. (Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2009), 299. Reader-response theory is a broad approach to literature with a wide spectrum of views regarding how much latitude the reader actually has.

[2] Abrams and Harpham, Glossary of Literary Terms, 217.

[3] Dallin H. Oaks, “Scripture Reading and Revelation,” Ensign, January 1995, 8.

[4] Joseph Smith, comp., Lectures on Faith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1985), 42.