Succession in German Mission Leadership during World War II

Roger P. Minert

Roger P. Minert, “Succession in German Mission Leadership during World War II,” in A Firm Foundation: Church Organization and Administration, ed. David J. Whittaker and Arnold K. Garr (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 553–71.

Roger P. Minert is an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University.

One of the principal tenets of the restored Church of Jesus Christ is that “a man must be called of God by prophecy and by the laying on of hands by those in authority to preach the gospel and administer in the ordinances thereof” (Articles of Faith 1:5). One application of this principle is seen in the bestowal and transfer of authority for specific callings within the Church’s administrative structure. Since the early days of the Church in Kirtland, Ohio, that structure has been developed, standardized, and codified to the point that essentially no officer of the Church today is without a leader to whom he or she reports the conduct of his or her stewardship. Leaders of the Church are called with not only a specific position of service but also usually with a tenure that eventually will be terminated by release, resignation, or death. The lines of priesthood and leadership authority are now clear and almost universally observed. However, the implementation of these standards has not always been possible, as is evident from the history of the two Latter-day Saint missions in Germany during World War II. How the leaders of those missions were selected without contact with Church leaders in Salt Lake City for three and one-half years is a fascinating story.

In August 1939, with war in Europe seemingly imminent, the First Presidency in issued instructions that all expatriate Latter-day Saint missionaries were to be withdrawn immediately from the East and West German Missions to Amsterdam or Copenhagen. The evacuation began on August 25, 1939, but most of those involved expected that they would return shortly, which is precisely what had happened in September and October 1938. Departing missionaries were instructed to appoint “temporary branch leaders” to serve until the missionaries could return. However, Joseph Fielding Smith, who had been traveling in Germany in his calling as an Apostle, arrived in Copenhagen on August 26. He announced in the first week of September that the missionaries would not be returning to Germany but rather to the United States. Germany had invaded Poland on September 1, and declarations of war had been issued by France, Great Britain, Poland, and Germany two days later. Back in Germany, several Church leadership positions remained unoccupied.

The two mission presidents in Germany had departed the country at the same time—M. Douglas Wood of the West German Mission from Frankfurt to Copenhagen and Thomas E. McKay of the East German Mission from Berlin to Basel, Switzerland, where he was also still serving as the president of the Swiss Mission. Each carried on correspondence with the respective mission office for some time. President McKay sent a letter dated September 8, 1939, to be read throughout the West German Mission and presumably the East German Mission as well. The conclusion of that letter reads as follows:

All who will receive this letter, must not only take care of their own responsibilities but also of those officers, teachers and members who have been called to serve their country. We pray sincerely to our Heavenly Father, that He might protect and bless those that have been called to arms and that He might strengthen those who have remained at home for the additional responsibilities that rest upon your shoulders. . . .

Thomas E. McKay, Mission President [1]

In late September, M. Douglas Wood and his family boarded a ship to return home to the United States. Joseph Fielding Smith likewise left Copenhagen for home. [2] With their departure, decisions regarding the administration of the two German missions needed to be made without delay. How, when, and by whom those decisions were made and who was asked to lead the two missions for the next six years is a complex story that reflects the talents and dedication of the men involved. The details are provided as follows for each mission.

The East German Mission Leadership in World War II

Before departing Berlin in August 1939, Thomas E. McKay asked Herbert Klopfer to serve as the administrator of the East German Mission. No record exists stating that Elder Klopfer was set apart by President McKay, who likely hoped to return soon. Several eyewitnesses stated in interviews conducted in 2006 that they had neither seen nor heard of any official transfer of authority. The letter of September 8 did not name a successor; thus Herbert Klopfer served more as an office manager than mission leader for the next several months.

When it became clear that President McKay would not be able to resume his work in Berlin, he clarified Elder Klopfer’s title and duties in a letter written from Basel on February 13, 1940. The salient message was as follows: “All communications to the Presiding brethren and saints in the mission should go out over your name as mission supervisor.” [3] (The German term was Missionsleiter.) He was to be paid a full-time salary, select two assistants, advise President McKay of major decisions, maintain contact with the leaders of the West German and Swiss Missions, and send a weekly letter to President McKay.

To underscore Brother Klopfer’s appointment as the mission supervisor, President McKay appended a statement to be sent to the Saints in each branch of the mission “to notify them of your call, your responsibility, and your authority. They will then know that you are acting in complete co-ordination with the authorities here [in Basel] and that what you do and say is official.” [4]

This assignment of authority over the East German Mission may have come as a surprise to the Saints in that area—the largest mission of the Church (by population) outside of the United States. Only during the Great War had the territory ever been supervised by a local priesthood leader.

The new supervisor of the East German Mission, Herbert Klopfer, was born in Werdau, Saxony, in 1911. He had served as a full-time missionary in the Austrian-German Mission and was barely twenty-eight years old when called to lead the mission. A faithful servant of the Lord, he had been a full-time employee of the Church since 1933—responsible for foreign language correspondence and translation. During his transition from part-time to full-time employment, he had moved his family from his hometown to Berlin. [5]

When Brother Klopfer received the charge to serve as mission supervisor, he was living with his wife and their two sons in an apartment adjacent to the mission office in a villa at Händelallee 6 in northwest Berlin. He chose as his counselors Richard Ranglack, a hotel employee and then president of the Berlin District; and Paul Langheinrich, a genealogist employed by the German government and a former leader in the Chemnitz District of that mission. There is no record of an official bestowal of authority upon those counselors, nor is there any surviving correspondence or autobiographical literature indicating that either of the counselors was set apart for his calling.

Fig. 1. The leaders of the East German Mission at Händelallee 6 in Berlin in 1940. First row from left: Missionaries Erika Fassmann, Johanna Berger, Ilse Reimer. Second row from left: first counselor Richard Ranglack, supervisor Herbert Klopfer, second counselor Paul Langheinrich. (Sonntagsgruss, September 22, 1940, NR. 34 N. P.)

Beginning in August 1939, Herbert Klopfer directed mission administrative affairs from the office in Berlin with the assistance of full-time sister missionaries. Elder Ranglack and Elder Langheinrich came by in the evenings and on weekends to assist. All of those brethren and sisters were able to travel to district conferences held in cities near and far.

President Klopfer’s leadership functions were hampered substantially when he was drafted into the German army in late 1940. However, he was very fortunate to be stationed in Fürstenwalde, just forty miles east of Berlin, where he served as a paymaster. From his office, he was authorized to use the telephone and the mail services to contact the mission office in Berlin as well as district and branch leaders throughout the mission. On several occasions, his counselors traveled to Fürstenwalde to report on matters requiring the supervisor’s decisions and to receive instructions at his hand.

President Klopfer’s wife, Erna, continued to live with their two sons in the apartment adjacent to the mission office. She also took short messages from her husband that formed the basis for detailed reports she typed and sent to Thomas E. McKay in Salt Lake City. Of course, the letters that crossed the Atlantic Ocean between Salt Lake City and Berlin were interrupted when the United States and Germany exchanged declarations of war in December 1941. There would be no communication of any kind between those offices for the next forty-two months. The leaders of the East German Mission were now on their own to keep the Church alive and functioning properly for a term they could not predict and under circumstances that would become increasingly challenging.

One significant action taken by Presidents Ranglack and Langheinrich in the absence of the mission supervisor was a visit of some ten days to the Saints in occupied Czechoslovakia. They met with members of the Church in the two branches of that country—Prag and Brünn (now Brno)—gave instruction, and ordained several men to priesthood offices. It is not clear whether the ordinations were done in response to instructions from President Klopfer or if the counselors acted on their own volition. Back in Berlin, they continued to attend district conferences in all thirteen districts and were accompanied on those occasions by several sister missionaries from the office staff.

In February 1943, Herbert Klopfer wrote a letter to his brethren in the mission leadership that formally detailed their responsibilities in his absence. The letter was written from the mission office and began thus: “During the period of my prolonged absence and due to the hindrances caused thereby for the leadership of the mission, I would ask that my elders called to serve as mission leaders [Ranglack and Langheinrich] observe the following directives.” [6] He then provided instructions in twelve specific topics, such as historical reports, communications with district and branch leaders, publications, finances, and the relationship between the two German missions. It is not impossible that Elder Klopfer had a premonition that he would soon be unable to carry out his duties as mission supervisor.

The work of the East German Mission leadership and the office staff appears from all reports to have been friendly and cooperative, but the convenience of leading the mission from Fürstenwalde ended for Herbert Klopfer when he was transferred to France in early 1943. He was no longer able to visit any Church units and no longer had access to military telephone and postal services. His counselors took over all of his functions, but their titles remained as before.

Perhaps the last time Presidents Klopfer, Ranglack, and Langheinrich were together was to observe a very sad occasion: the aftermath of the destruction of the mission office at Händelallee 6 on November 23, 1943. During the previous two nights, the neighborhood had been hit by devastating air raids by the British Royal Air Force, and all structures in the vicinity were destroyed. Fortunately, the mission staff had removed most of the important mission office property during the day on November 22, storing it in the apartment house in which the Langheinrich family lived at Rathenowerstrasse 52, about one mile to the north. The affairs of the mission were administered from that location for the next nineteen months.

In October 1944, Erna Klopfer received the letter feared by all German families—the one indicating that her husband was missing in action. His whereabouts had been unknown since July 22 and would remain so for the duration of the war.

Shortly after the arrival of the sad message that Herbert Klopfer was missing, Richard Ranglack assumed the leadership of the East German Mission, apparently in agreement with Paul Langheinrich, who became the first counselor. Again, eyewitness testimony and surviving literature support the conclusion that they were not set apart for the callings, had no authorization from Salt Lake City, and were not formally sustained in their callings by the general membership of the mission. Max Jeske of Berlin was asked to serve as the second counselor.

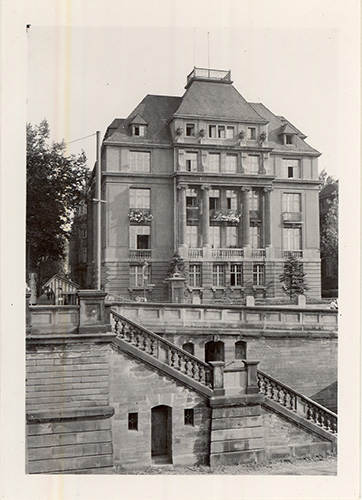

Fig. 2. The apartment house at Rathenowerstrasse 52 in Berlin. The mission office was established in rooms on the fourth floor in November 1943 and remained there until the summer of 1945. (Courtesy of Roger P. Minert, 2008.)

Although President Ranglack was not officially authorized by higher officers to lead the East German Mission, it appears that the district presidents, the branch presidents, and the general membership had no objection to the new administration. Reports were continually submitted to the mission office at Rathenowerstrasse 52 by branch and district leaders and the mission leaders with their office staff continued to accept invitations to attend district conferences. The last of those wartime events took place in Dresden on May 6, 1945, while the thunder of Soviet artillery was heard all day long just east of the city.

When the Soviet Red Army conquered Berlin on April 30, 1945, several dozen Latter-day Saint refugees were living in the apartment building at Rathenowerstrasse 52, including mission supervisor Richard Ranglack, whose apartment had been destroyed three months earlier. The Saints in that apartment house braved several harrowing experiences at the hands of the invaders, but survived the last days of the war and its aftermath in good order.

With the war over by the summer of 1945, the American occupation forces in western Berlin granted the Church the use of a fine villa in the southwest Berlin suburb of Dahlem. Several months later, Elder Ezra Taft Benson formally authorized Richard Ranglack to serve as the president of the East German Mission. The call was extended in a letter, and again there was no setting apart. President Ranglack served until 1947, when he was replaced by Walter Stover of Salt Lake City, the first American mission president in Europe after the war.

In 1948, an emaciated German POW knocked on Erna Klopfer’s door in Werdau and informed her that he had been with Herbert Klopfer when the latter passed away in a squalid Russian prison camp on March 19, 1945. The veteran had promised Elder Klopfer that he would visit Erna if he survived the war. Had this promise not been fulfilled, the world would still not know the fate of the former mission supervisor.

The West German Mission Leadership in World War II

After West German Mission president M. Douglas Wood arrived in Copenhagen in August 1939, he immediately initiated an extensive correspondence campaign with his staff back in Frankfurt. He made assignments regarding stewardships and sent copious instructions for the conduct of mission affairs. When it was announced that President Wood could not return to Frankfurt, he designated Friedrich Ludwig Biehl of Essen to serve as the mission supervisor and instructed him to report to President McKay in Basel until further notice. Five women who were originally called as missionaries were authorized to continue to live and work in the mission home at Schaumainkai 41 on the south bank of the Main River in Frankfurt. President Wood offered each woman a monthly salary of fifty to seventy-five Reichsmark in order to give her official status as an employee and thereby prevent the government from compelling her to take other employment. Within days, each of the women responded affirmatively to her assignment.

Neither the mission supervisor nor the office staff members were set apart in a specific ceremony. Following the departure of President Wood from Copenhagen, Friedrich Biehl traveled from his home in Essen to Frankfurt each weekend (a distance of one hundred and fifty miles) to conduct mission business. Born in Essen in 1913, he was a veteran of the Swiss-German Mission, spoke excellent English, and understood thoroughly the doctrines and practices of the Church. Although only twenty-six years of age at the time, he possessed the qualities considered by President Wood crucial for the execution of his calling. In naming Friedrich Biehl in a letter, President Wood had requested that all of the Saints in the mission “support Brother Biehl in his work with all of your energies.” [7]

Fig. 3. Friedrich Ludwig Biehl (1913–43) served as the supervisor of the West German Mission from September to December 1939. (Courtesy of Margaret Biehl Haurand.)

The weekend travel between Essen and Frankfurt soon became inconvenient and inefficient, so Elder Biehl quit his job at a dental firm in Essen and moved into the mission office. Unfortunately, this meant that he was officially unemployed and by December, the German army called him into active military duty. His counselors, Christian Heck and Anton Huck (both older men and members of the Frankfurt Branch) carried out his duties for several months.

In February 1940, President McKay officially designated Christian Heck (born 1902) as the new supervisor of the West German Mission. Because President McKay could not travel to Germany, he made the appointment in a letter. President Heck asked Anton Huck (born 1872) to serve as his counselor with no second counselor appointed at the time. In distant Russia, Friedrich Biehl was killed in an accidental fire on March 3, 1943.

Fig. 4. Christian Heck (1902–45, first row, left) served as the supervisor of the West German Mission from 1940 to 1943. (Courtesy of Otto Foerster.)

The new leaders of the West German Mission were enthusiastic and dedicated men who logged thousands of miles of travel to all points of the mission. From Denmark in the north to Austria in the south, they attended branch and district meetings and assisted local leaders in their functions all over the western half of Hitler’s empire. At the time of his call, Christian Heck was unemployed but soon thereafter was hired again as a traveling salesman. He constantly combined business travel with visits to local Church units. Anton Huck was a retired streetcar operator and, as such, was free to travel as often as he wished.

A curious document is found among the papers of Erwin Ruf, the president of the Stuttgart District. Entitled “Ruling” (Beschluß), the one-page statement is dated January 31, 1942, and appears to have been issued to dispel any doubt regarding Christian Heck’s authority to function as the mission supervisor. The translation of the text reads as follows:

A council convened today consisting of the following brethren: Johann Thaller, president of the Munich District; Hermann Walther Pohlsander of Celle [representing the Hannover District], and Erwin Ruf, president of the Stuttgart District. The council arrived at the following decision:

We hereby recognize Elder Christian Heck of Frankfurt as the current supervisor of the West German Mission until such time as he is released from this office by Church authorities.

It has also been decided that the mission leadership be expanded to include a second counselor. Brother Johannes Thaller was nominated.

[signed] Joh. Thaller

H. W. Pohlsander

Erwin Ruf

The following brethren accept the above decision:

[signed] Anton Huck Christian Heck

As a witness, representing the East German Mission:

[signed] Paul Langheinrich [8]

Because there is no evidence that members of the Church questioned the assignment of Elder Heck, who by then had been serving in that calling for fully two years, the document was likely produced in order to confirm the position of Elder Heck as the spokesman of the Church in the eyes of the government. The statement may also have substantiated to the government the claim made by Elder Heck that he needed to travel by rail to points all over western Germany to administer the affairs of the Church. As with the leaders of the East German Mission, there is reason to believe that no setting apart or “physical” transfer of authority took place in the cases of Elders Heck and Huck.

Fig. 5. The West German Mission office was housed in this building at Schaumainkai 41 in Frankfurt from 1938 to 1952. The president’s office window is on the ground floor on the far left. The entrance was on the west (right) side. (Courtesy of George Blake.)

Despite his age, Christian Heck was drafted into the German army on May 17, 1943. While serving on the Eastern Front, he was totally isolated from the Church and thus incapable of carrying out the duties of his office. Under those circumstances, there ensued a bit of a conflict regarding the leadership of the West German Mission. Thus it happened that Anton Huck convened a council of the district presidents (fourteen in number at the time) in the mission office at Schaumainkai 41. On that occasion, he proposed that Christian Heck be released as mission supervisor and that another man be chosen in his stead. Only two district presidents, Hermann Walter Pohlsander of Hanover and Otto Berndt of Hamburg, opposed the motion, insisting that Church leaders had no authority to release higher-level leaders without cause. When the motion passed with those two dissenting votes, the two men expressed their willingness to accept the decision of the majority in order to prevent a schism in the mission. Anton Huck was then selected as mission supervisor.

Several months after the war’s conclusion, it was learned that Christian Heck had been wounded in combat against the Allies and had died of his wounds in a Catholic hospital in southern Germany on April 19, 1945—just three weeks before the end of the war. He lies buried in the city cemetery in Bad Imnau.

Fig. 7. Christian Heck (middle of front row) represented the West German Mission at a conference of the East German Mission in Berlin in 1941. To his left is East German Mission supervisor Herbert Klopfer.

As the third wartime supervisor of the mission, Anton Huck was not set apart to this calling nor named to it in a letter. Church leaders in Salt Lake City had no knowledge of the situation in Frankfurt and no way to influence decisions made in Germany. From the statements and writings of eyewitnesses, there is no reason to believe that Anton Huck sought power but rather wished only to see the work of the mission continue. In the absence of Christian Heck, there was a great deal of work to be done among the Saints. As the war progressed, more and more members lost their homes and branches, lost their meeting places. However, while a dedicated Church leader, Elder Huck was also a known member and supporter of the National Socialist (Nazi) Party, a man who did not hesitate to extol the virtues of the Third Reich. However, he apparently restricted his political comments to settings outside of Church meetings.

President Huck asked Johannes Thaller to serve as his first counselor while continuing as president of the Munich District. Elder Thaller had both an automobile and a small truck; as a distribution manager for two different food producers in southeast Germany, he was constantly on the road. Kurt Schneider became the second counselor in the mission leadership. As the director of the Strasbourg branch of the Rheinmetall Company, he had not only a very nice automobile but also a chauffeur to drive it. President Schneider retained his calling as the president of the Strasbourg District. He was a dynamic leader and frequently traveled to the homes of individual members who lived far from branch meeting places. His wife, Charlotte Bodon Schneider, recorded many of those visits in her diaries during the war years.

In the summer of 1943, Anton Huck was summoned to the Gestapo headquarters in Frankfurt and required to answer a number of questions regarding the status of the Church in Frankfurt and in Germany. This he did without further complication at a time when dealings with the dreaded secret state police were avoided wherever possible. In October, the Huck family apartment in Frankfurt was destroyed in an air raid, and President Huck moved with his family into rooms in the mission home. They were there until after the war.

The year 1944 brought ever greater challenges for mission supervisor Anton Huck. One by one, branches were losing priesthood leaders and meeting rooms. Members were scattered far from home as soldiers, evacuees, or refugees, and several branches were meeting in the homes of members. Some branches had no priesthood support and held only Sunday School meetings and prayer circles. Elder Huck was no longer able to travel as freely as before. By early 1945, his counselors were severely hampered in their Church work: Johannes Thaller lost his automobile and Kurt Schneider was forced to evacuate Strasbourg to an isolated town high in the Black Forest. As the war neared its conclusion, Elder Huck no longer received reports from distant district presidents, and tithing remissions essentially halted.

By the time the American army entered Frankfurt on March 26, 1945, the mission office at Schaumainkai 41 housed several refugee Latter-day Saint families in addition to the Huck family and office staff members. The building escaped the many air raids with minimal damage. Anton Huck remained the mission supervisor until June 1945. He was then relieved by Max Zimmer, a leader of the Swiss Mission who had been authorized by the leadership of the Church in Salt Lake City to go to Frankfurt as soon as practicable. Elder Zimmer established communications with the Saints who had lived without such connections for forty-two months.

Conclusion

In both missions of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in war-torn Germany, worthy priesthood holders were called to replace the American expatriate mission presidents. In both missions, the first supervisor called (Herbert Klopfer for the East and Friedrich Biehl for the West) was drafted into the German army and eventually died in the service of his country. In the West German Mission, this happened a second time—to Christian Heck. In all three cases where a German member of the Church succeeded another German, it was done without any formal call from a higher authority, either in person or in writing.

In all cases, the administrative services of the mission offices were not interrupted for more than a day or two. [9] It has been reliably reported that all five mission supervisors carried out their stewardships with dedication and integrity and were instrumental in sustaining the existence of the Church in Germany for five years and nine months of war and during the initial postwar era. Perhaps Richard Ranglack spoke for the other four in suggesting the formula for success for mission leaders who did not enjoy the benefit of a formal setting apart: “When I look back on those years, I have to say that I could never have found the energy to do those things without the help of my [German] brethren.” [10]

Perhaps a crucial element in the acceptance of these mission leaders by the general membership is the fact that they were well known in their respective missions. The names of supervisors and counselors alike are seen on the programs of essentially all district conferences during the war, as well as in the minutes of meetings held in even the smallest branches. [11] The typical branch in those days had about a hundred registered members and an average attendance at Sunday School of about forty people. With such small groups, everybody in attendance knew everybody else. When visitors came, they were introduced and (if qualified) were asked to speak. When mission leaders came for branch or district conferences, they usually stayed with local families, not in fine hotels.

Mission and district leaders were also involved in personal events among the general membership. Branch and personal records indicated that those leaders were often asked to officiate at baptisms and priesthood ordinations when they came to town and to give healing blessings to local members. Many eyewitnesses recalled that those leaders were asked to preside at the traditional wedding ceremonies conducted in the branch rooms. [12] With such events common throughout both German missions, it can come as no surprise that no protests against the selection of specific mission or district leaders have been found in the existing literature. [13]

It is the author’s opinion that no individual selected for mission leadership in Germany during World War II was unqualified or unworthy to serve. These were the right men who were in the right place at the right time. All served with dedication and distinction and their combined efforts kept the Church alive and functioning in isolation from the rest of the Church and under the worst of circumstances.

Notes

[1] East German Mission History, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, CHL CR 27140.

[2] It may be that before he left Copenhagen, Elder Smith authorized Thomas E. McKay to function as the European Mission president. The author has not found any record of such a transaction. Perhaps Elder McKay did not receive his charge until he arrived in Salt Lake City.

[3] East German Mission History, CHL CR 27140.

[4] East German Mission History, CHL CR 27140.

[5] With excellent skills in English (a result of nearly a decade of living and working with American missionaries), Klopfer had interpreted for visiting General Authorities of the Church such as Heber J. Grant and J. Reuben Clark Jr. (Wolfgang Herbert Klopfer, interview by Roger P. Minert, Salt Lake City, November 3, 2006.)

[6] Herbert Klopfer to mission leaders [Richard Ranglack, Paul Langheinrich, Friedrich Fischer], February 20, 1943. East German Mission History, CHL CR 27140.

[7] M. Douglas Wood, papers, CHL MS 10817.

[8] Stuttgart District history, CHL CR 16982/

[9] This was true even when the Gestapo shut down the West German Mission offices for two days in 1943 and when the East German Mission home was destroyed on November 22–23, 1943.

[10] Richard Ranglack, autobiography (unpublished), private collection.

[11] A stellar example of this is the branch in Bühl in southwestern Germany. The minutes indicate that on a Monday evening, Christian Heck visited the branch along with two friends from the East German Mission: counselors Richard Ranglack and Paul Langheinrich. No branch was farther from Berlin at that time.

[12] Since 1876, only weddings conducted by the local civil registrar (Standesbeamter) have been valid under German law. When Latter-day Saint couples married during the war (as before and since), they did so first at the city hall. The ceremony held later that day in the Church rooms (and rarely in a home) was of ceremonial importance only. With the nearest temple in Utah, temple marriages among German Latter-day Saints before the war were rare (only one is known in the East German Mission and none in the West German Mission).

[13] The question raised by Elders Pohlsander and Berndt during the discussion about the release of Christian Heck in 1943 was apparently not intended to oppose the candidacy of any potential successor but to question the validity of the process.