Forming A Collective Memory of the First Vision

Elise Petersen and Steven C. Harper

Elise Petersen and Steven C. Harper, “Using Art and Film to Form and Reform a Collective Memory of the First Vision,” in An Eye of Faith: Essays in Honor of Richard O. Cowan, ed. Kenneth L. Alford and Richard E. Bennett (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City, 2015), 257–75.

Elise Petersen was an undergraduate student majoring in history at Brigham Young University when this article was written.

Steven C. Harper was a historian at the Church History Department in Salt Lake City when this article was written.

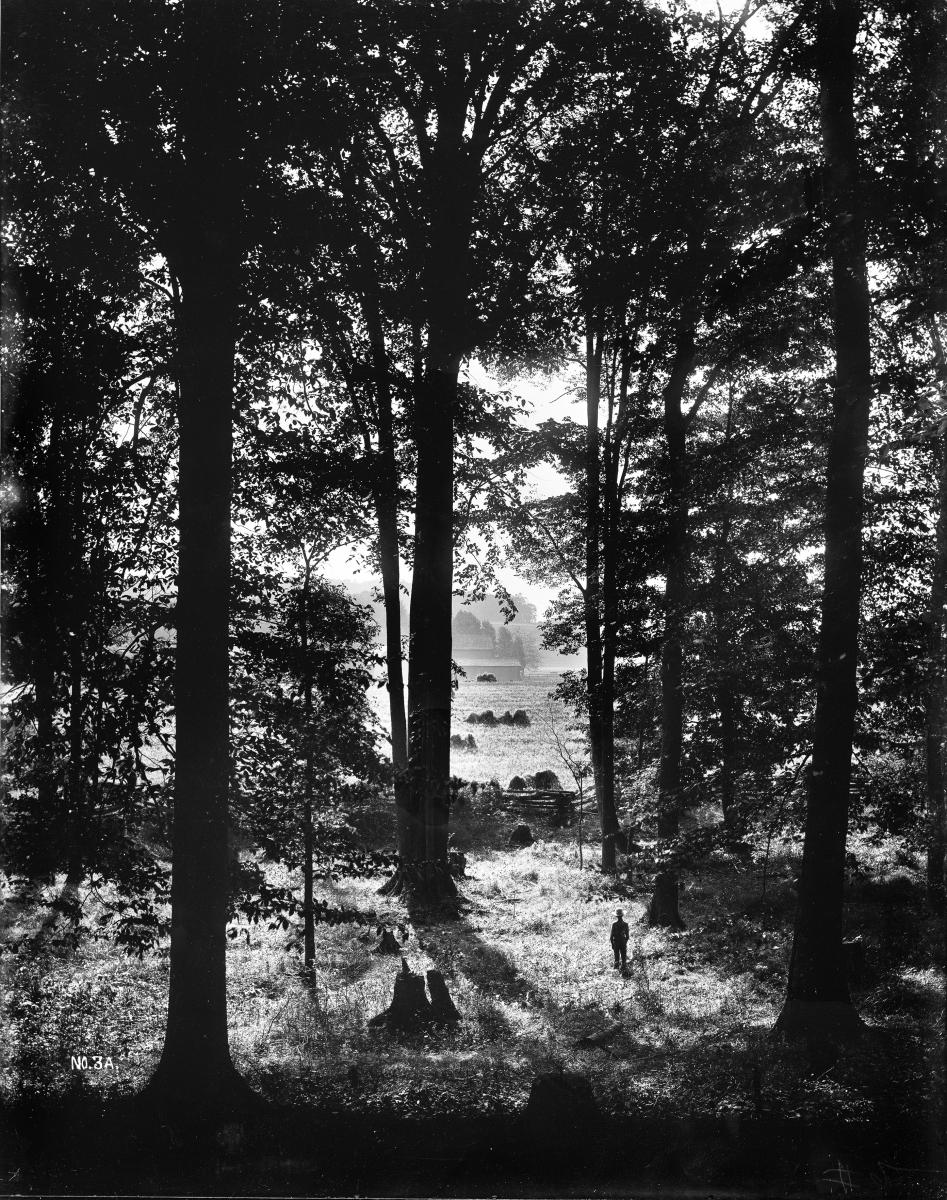

The Sacred Grove in Manchester, New York, where Joseph Smith spoke with God the Father and his Son Jesus Christ. (Photo by George E. Anderson, Church History Library.)

The Sacred Grove in Manchester, New York, where Joseph Smith spoke with God the Father and his Son Jesus Christ. (Photo by George E. Anderson, Church History Library.)

When I (Steve) joined the faculty of BYU’s Department of Church History and Doctrine in 2002, Richard Cowan became my mentor. I could not have had a better one. Richard treated me with kindness and generosity, always interested in my ideas and projects. Without quenching my passion, Richard had a moderating influence on some of my misguided zeal. He is so wise. He is so willing to share his wisdom. He is a first-rate scholar who is also an involved and gentle mentor. That is an uncommon combination that multiplies his contribution to the world. Richard has not only taught tens of thousands of students, but he has also mentored many like me who have taught thousands of others. I am grateful to the editors of this volume for inviting me to contribute to it. When I saw the invitation, I had a great desire to produce some work that would reflect Richard’s values and his influence on me. I’m very pleased to acknowledge Elise Petersen as a coauthor, and I trust that Richard’s mentoring influence continues to be manifest in our collaboration on this chapter.

Galilee Baptist Church sits beside Forty-Eighth Street in the relatively quiet Los Angeles neighborhood between downtown and the coast.[1] It’s a homely building, architecturally speaking, but it used to house a soothing mural depicting a tranquil sylvan setting, painted on the wall behind the pulpit for parishioners to ponder as they worship. Unfortunately, the mural was burned recently, a sad loss for the Galilee Baptists and for Latter-day Saints like Richard Cowan who used to worship in that building when it housed the Arlington Ward. Many who worshipped in this church remember when artist Martella Lane was hired to paint the scene on the empty wall space shortly after World War II.[2] Richard remembers that at one point the painting had a caption written across the top in gold: “The Sacred Grove wherein Joseph Smith had his first vision.” When the Baptists acquired the building they didn’t keep the caption, for obvious reasons. To them, presumably, the mural represented the peace and majesty of God’s creation, while to Latter-day Saints it represented the seminal event of their shared story.

With the story of this mural as a backdrop, this essay analyzes when, how, and why Latter-day Saints developed a shared meaning of the First Vision. It did not happen overnight, or even in the first decade of Church history. The analysis will show not only how, when, and why the Saints developed a collective memory of Joseph Smith’s First Vision, but how that memory has been and continues to be represented and transmitted from generation to generation through powerful and problematic artistic representations.

A Collective Memory of Joseph's Vision

It may seem odd to Latter-day Saints today to think that there was a time when their forebears in the faith did not have the same shared memory of the First Vision that they do, but such is the case. Memory is more mysterious, complex, and meaningful than we may think. In fact, memory is not even a single thing but “an umbrella term under which congregate myriad phenomena.”[3] This essay is not about memory per se, but about the formation and reformation of a particular shared or collective memory among Latter-day Saints.

The preferred term to describe this ongoing process is consolidation, which, most simply put, is the process of making enduring memories. Memory consolidation does not explain the First Vision itself, but it has created the meanings and memories of Joseph Smith’s vision that Latter-day Saints generally share—the set of ideas suggested to Latter-day Saints when they see something like Martella Lane’s painting of the grove. The Galilee Baptists could appreciate the same painting and not share the collective memory it evokes in Latter-day Saints.

Understanding the psychological process of memory consolidation provides an avenue for examining the role of the First Vision and visual representations of it in the doctrine and culture of the Church today. If the discussion of memory formation and reformation may be new—and perhaps uncomfortable—to some Latter-day Saints, they should note that it does not undermine Joseph Smith’s First Vision. All memories undergo a formation process and represent past events. The memories are not the event itself.

When individuals consolidate memory, they hold in their minds stable (already consolidated) and labile (not yet consolidated) components, and they combine these to construct more memory. Making choices, however subtle or subconscious, about how to attend to these components enables the person to identify and manage relationships between them. Collective memories consolidate when stable memory items—like one or more of Joseph Smith’s written accounts of his vision—are selected by a group and related meaningfully to their existing knowledge and identity, further shaping each. In individuals, the function of relating happens in the brain. Collective memories consolidate, by analogy, via the role of a person or persons memory scholars describe as a “selector or relater.”[4]

As group members pay attention and relate emotionally to the choices made by the selector and relator, stable narratives form out of the variable parts of the social working memory. In this process, these narratives become both generalized and specific. That is, in time, much of the narrative becomes common knowledge unattributed to any particular source, while, at the same time, some of it becomes specific, attributed detail. Once consolidated, the generalized knowledge can be efficiently and quickly accessed by the remembering group. Because selectors and relators from Joseph Smith to their parents and teachers have emphasized the vision and related it meaningfully, a group can quickly remember the basics of Joseph Smith’s First Vision and relate some general elements, including religious confusion, Joseph’s prayer in a grove to know which church to join, and the answer of the revelation that he should join none of them. These elements of the First Vision is generalized, unattributed knowledge. The group could also remember some specific elements from their memory, including “I saw two personages,” James 1:5, and “this is my Beloved Son.”

Joseph Smith’s recorded memories of his vision, especially the one in his 1839 Manuscript History (excerpted and canonized in the Pearl of Great Price), is the most significant influence on how Latter-day Saints have formed a collective memory of his vision, but even after this, several key players have functioned as selectors and relaters, especially Apostles Franklin D. Richards (who selected this vision account for inclusion in the Pearl of Great Price) and Orson Pratt (who emphasized and taught about the vision more than anyone else in the formative period when the Latter-day Saints consolidated a collective memory of it).[5] These and other selectors or relaters made choices that determined which memory items were available to the Saints to consolidate a new memory, decided how to relate those components together, and then rehearsed the memory among the Saints often enough for it to become general knowledge.

This photograph of the Sacred Grove gives a good idea of how Latter-day Saints envision the environment of the First Vision. (Photo by Brent R. Nordgren.)

This photograph of the Sacred Grove gives a good idea of how Latter-day Saints envision the environment of the First Vision. (Photo by Brent R. Nordgren.)

1839 Manuscript History Becomes Generalized Knowledge

It is becoming better known that Joseph Smith recorded more than one account of what was later coined his First Vision. Some criticize the differences in detail among the accounts, discounting the event because of the discrepancies, overstating differences and understating the consistency in Joseph’s accounts. The Church has published and publicized the several accounts repeatedly over half a century, but consolidation of the Saints’ collective memory does not happen even that quickly. And once it is formed, it is difficult but still possible to integrate new information into the shared memory of the Saints, or the ideas that most Latter-day Saints would consider common knowledge.

It was not a forgone conclusion that the Saints would form a shared memory of Joseph’s First Vision, nor inevitable that the one that formed was the only alternative that could have formed in the minds of most Latter-day Saints. Though Joseph left lots of evidence of his vision, there is no record of him calling it his First Vision or using the term “Sacred Grove,” yet those very shorthand terms written across the top of the painting in Richard Cowan’s boyhood chapel were common knowledge to him and everyone else who worshipped there. It’s worth asking, then, in the Latter-day Saint collective memory, how, when, and why were the common-knowledge details of the event selected and related?

Several historical markers display the process of the Latter-day Saints’ consolidating a shared memory of Joseph Smith’s First Vision. These include the composition of the account in his Manuscript History by 1839 and Orson Pratt’s 1849 publication “Are the Father and the Son Two Distinct Persons?” This article was published in the Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, and it was here that the term “first vision” first appears in the historical record. Pratt drew from the Manuscript History’s description of two divine personages—one the Father, the other his Beloved Son—as evidence for the Latter-day Saint conception of the Godhead.[6] The next marker is the 1851 publication of the Pearl of Great Price, including the excerpted Manuscript History story of the First Vision.[7] Finally, in 1880, the Saints canonized the Pearl of Great Price, making Joseph’s First Vision as told in his Manuscript History into scripture.

The 1880 canonization of the Pearl of Great Price is a historical marker in the process of consolidating the Saints’ shared memory. It took some sixty years from the vision itself for Latter-day Saints to consolidate the collective vision memory that is so widely shared today. That does not mean that the vision did not happen as Joseph remembered it, only that it takes groups some time to form their shared memories. Consolidating collective memory is a process that takes place over decades, not an event like the vision itself. Leading up to the canonization of Joseph’s account, President John Taylor preached multiple sermons by 1879 in which the solidifying collective memory played an important role.[8]

In summary, most Latter-day Saints seem to have a shared understanding of the First Vision by about 1880. That understanding came from the selection and relation of many elements, including the story as it was told by Joseph in 1839, published in 1842, excerpted in the Pearl of Great Price in 1851, and finally canonized by the Saints in 1880. During this time, the memory, which originally had varying possible versions and meanings, was interpreted and repeated over and over, especially by Orson Pratt and finally by John Taylor. At the outset, no visible force blatantly demanded which version of Joseph Smith’s vision would consolidate in the minds of the Saints and eventually canonize into their scripture, but Latter-day Saints would likely find it easy to believe in retrospect that the creation of this mutual memory was guided by inspiration.

Visual Representations

Canonization of the Pearl of Great Price in the October 1880 general conference elevated Joseph’s 1839 narrative to scriptural status and signified that it embodied, or ought to, the general knowledge of the Latter-day Saints regarding the First Vision. The process of having that text and therefore memory consolidated as the collective memory of the Latter-day Saints, and then transmitting that memory from one generation of Saints to the next, depended on another process known as recursion, in which groups use consolidated memories to form new memories. In this case, the consolidated memory is Joseph’s Manuscript History, excerpted in the Pearl of Great Price and rehearsed by leaders like Orson Pratt and John Taylor, and the new memories are ones that the rising generations of Latter-day Saints have formed. This kind of recursion perpetuates a shared memory, enabling others to connect powerfully and unforgettably with that memory, even though their contact with the actual events and people are greatly limited.

One way to see recursion occurring is to notice when visual representations of the vision began to appear and be used late in the nineteenth century, about the time the Saints’ collective memory consolidated and the 1839 account became scripture. These visual representations of the vision are potent, subtle factors in the process of memory consolidation and recursion. James B. Allen, a leading scholar of Joseph Smith’s First Vision, observed that it was half a century after the sacred experience before it “found its way into artistic media, but it was largely through these media that it eventually found its way into the hearts and minds of the Saints.”[9]

For many, many Saints, visual representations, such as the mural in the Arlington Ward chapel, have acted as agents of transmission of that collective memory from one generation to the next. Moreover, the representations themselves—ranging from woodcuts and murals to films and coloring-book pages—reflect the extent of the 1839 narrative’s consolidation within the Saints’ collective memory. Since 1873, when the earliest known image of the vision was circulated, artists and filmmakers have transmitted and retransmitted versions of Joseph’s First Vision to the Saints, reinforcing the important memory.[10]

Woodcut by J. Hoey

The earliest known image of Joseph Smith’s First Vision was published in 1873 in T. B. H. Stenhouse’s influential book Rocky Mountain Saints.[11] The image, a woodcut by a J. Hoey, depicts a young Joseph at the moment the Father and Son reveal themselves to him. Joseph, with his hands in the air in a gesture of surprise and his back turned to viewers, effectively allows the viewer to experience the sudden and overwhelming experience of seeing both the Father and the Son, complete with their “brightness and glory defy[ing] all description, standing above [him] in the air.” Published alongside Stenhouse’s rehearsal of that 1839 narrative, the woodcut helped readers visually rehearse the story, reinforcing Stenhouse’s written one.

Five years after the publication of Rocky Mountain Saints, another artist—a devoted Mormon convert concerned about transmitting the Saints’ founding story to a generation that had not known Joseph Smith—began painting the first comprehensive visual history of the early Saints, initially advertised as the “Grand Historical Exhibition” and eventually known as his “Mormon Panorama.”[12] The paintings by Carl Christian Anton (C. C. A.) Christensen were not viewed in a gallery setting, but were sewn together, rolled on a large scroll, then unrolled and shown one by one as a narrator read historical details of each pictured event from an informative script, authored by Christensen himself.[13] Unfortunately, though twenty-two of the twenty-three original paintings survive today, the panorama’s first painting—Christensen’s First Vision—has not survived. Even though this painting has been lost, Christensen’s script at least enables us to imagine how the painting visually represented Joseph’s experience as he told it in his 1839 Manuscript History. Following that account closely, Christensen’s script notes Joseph’s reading of James 1:5 and his subsequent decision to pray in the woods; his experience with an unseen, evil power; his deliverance from that power by “a glorious light”; and his interaction with “two glorious personages,” identified as the Father and the Son.[14]

As with the woodcut in Rocky Mountain Saints, Christensen’s visual representation, in combination with his verbal rehearsal (this time via lecture rather than written publication), is a manifestation of memory recursion. Christensen’s collection of twenty-three Mormon history paintings deliberately aimed to educate Latter-day Saints on the Church’s early history. The advertisement for “Christensen’s Grand Historical Exhibition” speaks especially to the Church’s youth: “This entertainment should be seen by all,” it says, “but especially by young Latter-day Saints, as these artistically executed pictures will impress indelibly upon their minds the trying ordeals through which the Church had passed before it found a resting place in the valleys of the mountains.”[15] These words indicate that Christensen was keenly aware of how visuals like his could play an important role in perpetuating memories of the events represented.

California meetinghouse art

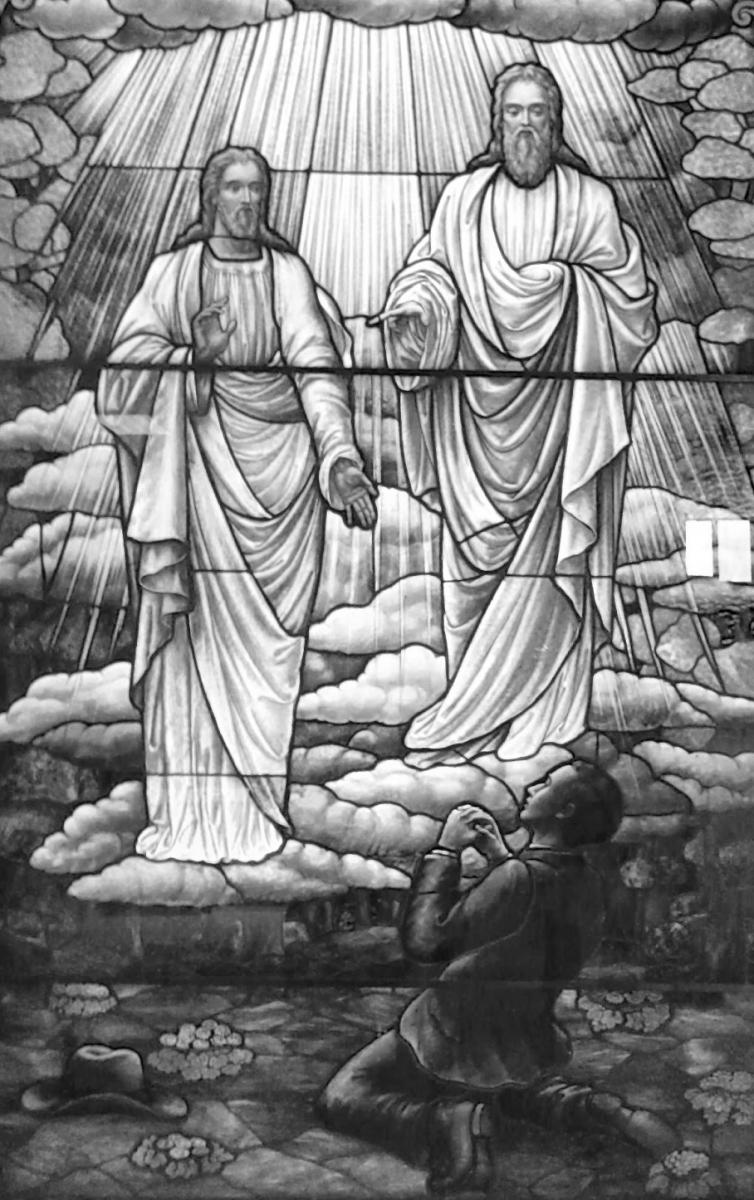

The beginning decades of the twentieth century saw the rise of Mormon architecture west of Salt Lake City as Saints in California began to construct the state’s first permanent meetinghouses. The first of these to be completed, eventually known as the “Adams Chapel” in Richard Cowan’s native Los Angeles, featured the consolidated First Vision story in an ornate stained-glass window. Reminiscent of the woodcut from Rocky Mountain Saints, the Adams Ward window presented the Saints with a weekly memento of Joseph’s interaction with the Father and the Son, captioned by the phrase “This is my Beloved Son. Hear him!”[16]

In California Saints, a 1996 history of the Saints in the Golden State, Richard Cowan himself contributed to the processes of consolidation and recursion when he referred to the Adams Ward window. He acted as a selector by choosing to begin his book with the story of Joseph’s vision as told in the Pearl of Great Price and by illustrating with the Adams Ward stained-glass window, and he acted as a relater by linking the vision to the story of Saints in California, showing that it was their genesis story, the seminal event of their faith. Richard perfectly restated the Saints’ generalized knowledge of the vision, saying of Joseph, “He recorded that as he knelt in a grove of trees, God the Father and his Son, Jesus Christ, appeared to him in a glorious vision.”[17] Richard’s book illustrates both the consolidated memory the Saints share of Joseph’s vision and some of the means employed to continue the process of consolidating that memory further, both in terms of reinforcing it by repetition for those who already share it and by rehearsing it for those who don’t.

The Adams Ward window illustrates how the Saints have relied on visual representations in these processes of sharing memory. Indeed, the window was eventually moved from Los Angeles to Salt Lake City to serve as the centerpiece in the original Church History Museum installation, where it has both reflected and shaped the memory of the thousands upon thousands who have visited there and felt inspired by its message.

First Vision film

The capacity of twentieth-century technology to rehearse a shared memory dwarfs the window’s reach. In 1976 the Church introduced a short film adaptation of the First Vision, starring fifteen-year-old Stewart Petersen (who also appeared in Where the Red Fern Grows, 1974; Against a Crooked Sky, 1975; and Pony Express Rider, 1976).[18] In two senses, director and producer David Jacobs clearly shared the Saints’ general memory. First, he was among the many who knew the vision primarily as Joseph related it in his Manuscript History, canonized in the Pearl of Great Price. Second, by depicting the Saints’ shared memory of the vision in film, Jacobs expanded the audience and harnessed the power of a medium with enormous potential to facilitate memory consolidation and recursion.

Like C. C. A. Christensen’s painting and narration in the Mormon Panorama, the 1976 film shows Joseph wrestling with religious confusion, reading James 1:5, secluding himself in the woods, kneeling to pray, and experiencing the vision of two heavenly personages. But unlike Christensen’s comparatively primitive motion picture, the film combined sound and scenes more powerfully than ever before. A narrator read from Joseph’s history as the camera and Petersen worked together to portray Joseph’s anxiety and alarm and subsequent rescue by “a pillar of light, which descended gradually until it fell upon [him].” As the narrator rehearses the appearance of the two heavenly beings and identifies them as the Father and Son, the camera pans out to show the two figures, standing in the air above Joseph’s head.[19]

The 1976 film was, and to a degree remains, a powerful catalyst of consolidation, since that process depends largely on rehearsal modulated by emotion, the replaying of the memory over and over in connection with strong feelings. The film has reached hundreds of thousands of twentieth- and twenty-first-century Saints via teachers, parents, friends, and missionaries across the globe. Until 2005, when the Church sponsored a new big-screen adaptation (again drawing upon the 1839 Manuscript History/

Originally located in the Adams Ward Chapel in Los Angeles, this stained glass window presents Joseph's First Vision along with a key phrase from the canonized account: "This is My Beloved Son, Hear Him!" The window has since been relocated to the Museum of Church History and Art in Salt Lake City. (Courtesy of Wikicommons.)

Originally located in the Adams Ward Chapel in Los Angeles, this stained glass window presents Joseph's First Vision along with a key phrase from the canonized account: "This is My Beloved Son, Hear Him!" The window has since been relocated to the Museum of Church History and Art in Salt Lake City. (Courtesy of Wikicommons.)

Statue of The Vision

Another work of art that serves to further the collective memory of the Saints is a sculpture that stands in the atrium of the Joseph Smith Building on the campus of Brigham Young University. It movingly conveys the Saints’ collective memory of the vision. Avard T. Fairbanks sculpted a cast bronze of young Joseph on his knees, leaning back and looking heavenward. Titled The Vision, the sculpture was commissioned by the BYU classes of 1945, 1947, 1955, and 1957. Fittingly, the University decided to place the statue in the atrium of the new Joseph Smith Building. The atrium that surrounds The Vision effectively makes the building named for the Prophet a frame around the Saints’ shared memory of his First Vision. Like the Galilee Baptists in the chapel on Los Angeles’s Forty-Eighth Street, visitors who don’t share the Saints’ collective memory of the vision may admire or even be moved by the sculpture and its setting without understanding its intended message. Those who share the collective memory can sit in the atrium modeled after the Sacred Grove and automatically retrieve both the general and specific knowledge they share of the First Vision. When President Henry B. Eyring unveiled The Vision in 1997, he expressed his desire that visitors to the atrium would indeed use this piece of art to draw upon the collective memory: he paid tribute to Fairbanks “for what he didn’t show” and expressed his hope that the piece would cause all who viewed it to “imagine with an eye of faith” the “other figures not sculpted here.” President Eyring testified, “God the Eternal Father and his Beloved Son Jesus Christ appeared to open this dispensation.”[21] Because of the effective way the Saints’ memory of the First Vision has been consolidated and rehearsed, most Latter-day Saints who see the sculpture could indeed imagine Joseph envisioning two personages, Father and Son, glorious beyond description.

Recent art of the First Vision

Visual art depicting Joseph Smith’s vision has multiplied rapidly over the past three decades. Some pieces are iconic, like Del Parson’s 1987 portrayal that graces many Latter-day Saint chapels, meeting programs, and missionary pass-along cards. Others are lesser known, like Richard Linford’s intriguing contemporary piece, Joseph Smith’s First Vision, completed in 2010. But they all reflect and further shape the consolidated memory Latter-day Saints share—the generalized story, including a few specific elements, of Joseph Smith’s 1839 vision narrative.[22] These renditions of the vision have played important roles in the recursion of the First Vision memory. The cinematic and visual arts are memorable and expressive; they appeal to the senses, and they reinforce Joseph Smith’s memory by presenting his story in a way that helps more people connect to it and create their own related, personal memories, thus ensuring that each new generation inherits essentially the same collective memory. It is not the purpose of this essay to review every piece, but rather to reflect on how, in general, such art has shaped the Saints’ memory.

A Problem with Recursion via Visual Arts

It might seem like there could be no downside to using visual arts as agents of collective-memory recursion. They convey large amounts of information efficiently and often with the emotion needed to forge meaningful, enduring memories. They can convey meaning across cultures and language barriers. President Dieter F. Uchtdorf, for example, fondly recalled the little meetinghouse in Zwickau, East Germany, where he worshipped as a boy, “with its stained-glass window that showed Joseph Smith kneeling in the Sacred Grove.”[23] But the very power of the visual arts to convey meaning is complicated by the nature of memory. Generally, human memory is good, as neuroscientist Larry Squire put it, “for inference, approximation, concept formation, and classification—not for the literal retention of the individual exemplars that lead to and support general knowledge.”[24] Put another way, we’re good at remembering what we know, not how we know.

Remembering what we know but forgetting how we know is called source amnesia. As noted above, Latter-day Saints widely share general knowledge of Joseph’s First Vision—religious confusion, James 1:5, Sacred Grove, prayer, two personages whose brightness and glory defied description—but have little or no knowledge of how they know this information. Many, it’s true, would cite Joseph’s history excerpted in the Pearl of Great Price, but few know where that text came from, or how, when, or why it was composed. Further, few can identify which elements in a visual depiction are actually from Joseph Smith’s written version and which arise out of artistic license.

Generally the Saints’ shared memory serves them just fine. The ability to recall the general knowledge of the First Vision, with its few specific elements, is usually enough to sustain the faith of Latter-day Saints. But problems occur because memory is “imperfect, subject to error and reconstruction, distortion, and dissociations.”[25] The more source amnesia the Saints experience—or the further downstream and detached they get from Joseph’s own memories—the more their collective memory of the First Vision will distort, blur, and inaccurately reflect his.

When the Saints rely too heavily on visual or cinematic arts as the catalysts of their memory, the problem of source amnesia can be compounded, largely because of suggestibility. Researchers have found that suggesting to people that they remember or imagine an event in a certain way dramatically increases distortion. Artistic and cinematic representations of Joseph’s vision, by their nature, suggest to viewers how Joseph experienced the vision.[26]

It is common to hear Latter-day Saints talk about, even testify of, elements of the vision that are suggested by artistic or cinematic representations rather than reported in Joseph’s memories. Distortion can begin at a young age in the most impressionable minds. Take, for example, a five-year-old who recites the First Vision story, making special mention of the rabbit that came out of hiding in a log when Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ appeared, as seen in the Living Scriptures video Joseph Smith’s First Vision. The child has made the rabbit a concrete part of the story, not realizing that it was simply an artistic addition to the scene in the film.[27]

Similarly, adult Latter-day Saints have adopted some details of the First Vision from film and art that are not necessarily congruent with historical accounts. Many cinematic representations have encouraged Latter-day Saints to assume that Joseph Smith went home and told his parents about his vision immediately after it occurred. Even though this idea originates in artistic license and not out of any of Joseph’s accounts, some films and pageants suggest that this happened, and many Saints never second-guess that it did indeed occur.

In a similar vein, George Manwaring composed the hymn “Joseph Smith’s First Prayer” after being inspired by C. C. A. Christensen’s painting in the Mormon Panorama. The inspiration for the hymn, then, is founded in Christensen’s representation of Joseph’s Manuscript History, with elements of distortion or artistic license necessarily taken at each remove from the Manuscript History.[28] There is nothing wrong with being inspired by artistic representations of the First Vision; indeed, the inspiration they provide is one of their most honorable purposes. But reliance on these interpretative sources is a double-edged sword: if viewers are not careful, they easily adopt suggested occurrences and remember them as actual events. Suggested memories are common and usually harmless, but since Joseph’s First Vision is so foundational to the Saints’ faith, it is attacked from every angle, and some whose suggested memories have been shown to be based in unhistorical sources have lost their faith in the Restoration story as a result.

Avard T. Fairbanks's sculpture "The Vision," pictured here, is located in the courtyard of the Joseph Smith Building at Brigham Young University. When Elder Henry B. Eyring unveiled the sculpture in 1997, he paid tribute to the sculpture "for what he didn't show," referring to the implied presence of the Father and the Son. (Photo by Brent R. Nordgren.)

Avard T. Fairbanks's sculpture "The Vision," pictured here, is located in the courtyard of the Joseph Smith Building at Brigham Young University. When Elder Henry B. Eyring unveiled the sculpture in 1997, he paid tribute to the sculpture "for what he didn't show," referring to the implied presence of the Father and the Son. (Photo by Brent R. Nordgren.)

Conclusion

Beginning with Joseph Smith but requiring a process that lasted until about 1880, the Latter-day Saints consolidated and shared a collective memory of Joseph’s vision. It was no sooner consolidated than the Saints put it to work in the recursion process, sharing it from generation to generation, using the most powerful visual and cinematic arts available, along with the historical records to rehearse the story vividly and with the emotion necessary for the memory to form and reform in successive generations. The paintings, stained-glass windows, sculptures, and films that represent and tell the story of Joseph Smith’s First Vision are models of memory recursion, the use of consolidated memory to forge new memory. They convey the vision powerfully, rehearsing it with the strong emotions that help create the memory and cause it to endure. They helped create a connected network of memory, remarkably aiding millions of individuals in remembering a pivotal event that occurred nearly two hundred years ago.

These memory-recursion models remain important agents for remembering from generation to generation. But they also contribute to source amnesia and in suggestive ways increase memory distortion. Because Joseph Smith’s First Vision is the Saints’ genesis story, the seminal event of our faith, it is important, even vital, to the integrity of our faith that we not rely solely on artistic representations of the First Vision to form our memory of it but that we return often to Joseph’s records of the experience. Joseph Smith had a remarkable vision, and through the processes of consolidation and recursion his story has become ours. We ought to represent and share it in every appropriate way we can, but we also should work to maintain the integrity of the Saints’ shared memory of Joseph Smith’s First Vision.

Notes

[1] See photograph from Forty-Eighth Street, PH 211, box 4, folder 26, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[2] Richard O. Cowan, interview by Steven C. Harper.

[3] Thomas J. Anastasio et al., Individual and Collective Memory Consolidation: Analogous Processes on Different Levels (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 3–4.

[4] Anastasio et al., Individual and Collective Memory Consolidation, 105.

[5] Joseph Smith authored four distinct accounts of his First Vision; the 1839 Manuscript History, excerpted in the Pearl of Great Price, is one of those four. All accounts may be accessed online via The Joseph Smith Papers, http://

[6] Orson Pratt, “Are the Father and the Son Two Distinct Persons?,” Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, October 15, 1849, 310. The 1839 Manuscript History is the only vision account wherein Joseph Smith recalls the presence of two heavenly beings and identifies them as the Father and Son. None of the other accounts—written in 1832, 1835, and 1842—contain both of these details.

[7] The Pearl of Great Price, though published in 1851, was canonized in 1880. A collection of documents gathered by Franklin D. Richards, then a member of the Council of the Twelve Apostles and the president of the British Mission, the Pearl of Great Price was intended to increase the accessibility of the important documents therein for Saints in Europe and across America. The decision was made to publish this narrative, without inclusion or even mention of other accounts. Thus this account became the dominant shaper of the Saints’ collective memory of the First Vision.

[8] See John Taylor, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1881), 21:155–67. Less than a month later, John Taylor preached Joseph Smith’s First Vision again, with unmistakable emphasis on the appearance of both Father and Son to Joseph Smith as commencement of the last dispensation. Drawing on the now widely shared memory of Smith’s 1839 story, President Taylor told the story yet again: “The Father pointing to the Son said, ‘This is My Beloved Son in whom I am well pleased, Hear ye Him!’ Here, then, was a communication from the heavens made known unto man on the earth, and he at that time came into possession of a fact that no man knew in the world but he, and that is that God lived, for he had seen him, and that his Son Jesus Christ lived, for he also had seen him.” John Taylor, in Journal of Discourses (Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1881), 21:65.

[9] James B. Allen, “Emergence of a Fundamental: The Expanding Role of Joseph Smith’s First Vision in Mormon Thought,” in Exploring the First Vision, ed. Samuel Alonzo Dodge and Steven C. Harper (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2012), 241.

[10] Samuel Ross Palfreyman identified the 1873 woodcut as the earliest vision image in “Mormon Roots in the American Forest: God, the Devil, and Angels in the Nineteenth-Century Hemlock-Hardwood Forest of New York” (student paper, Boston University, May 2012), 15–16; T. B. H. Stenhouse, The Rocky Mountain Saints: A Full and Complete History of the Mormons (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1873), illustration prior to page 1.

[11] Palfreyman, “Mormon Roots in the American Forest,” 15–16. Palfreyman identifies the woodcut in Rocky Mountain Saints as the earliest surviving First Vision image; Stenhouse, Rocky Mountain Saints, illustration prior to page 1.

[12] Richard L. Jensen and Richard G. Oman, C. C. A. Christensen, 1831–1912: Mormon Immigrant Artist, essay and catalog (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1984), 91.

[13] See C. C. A. Christensen, “Lectures as written by C. C. A. Christensen,” L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[14] Christensen, “Lectures”; emphasis added.

[15]“Christensen’s Grand Historical Exhibition,” L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[16] Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1996), 2, 256.

[17] Cowan and Homer, California Saints, 3.

[18] Stewart Petersen, November 25, 2013, telephone interview by Elise Petersen.

[19] The First Vision: The Visitation of the Father and the Son to Joseph Smith, directed by David Jacobs (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1976), videocassette.

[20] See Joseph Smith: Prophet of the Restoration (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2005), DVD.

[21] Henry B. Eyring, “Remarks Given at the Unveiling Ceremony of ‘The Vision,’” Religious Education History, Brigham Young University, 66–68.

[22] Del Parson, The First Vision, painting, 1987; Richard Linford, Joseph Smith’s First Vision, painting—acrylic on canvas, 19 x 24 inches, October 4, 2010.

[23] Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “Seeing Beyond the Leaf,” Religious Educator 15, no. 3 (2014): 3.

[24] Larry R. Squire, “Biological Foundations of Accuracy and Inaccuracy in Memory,” in Memory Distortion: How Minds, Brains, and Societies Reconstruct the Past, ed. Daniel L. Schacter (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), 220.

[25] Squire, “Biological Foundations,” 220.

[26] See Daniel L. Schacter, “The Sin of Suggestibility,” in The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2002), 112–37.

[27] Joseph Smith’s First Vision (Ogden, UT: Living Scriptures, 2005), DVD. In 1999, then five-year-old Nicole Crandall Siegel was asked by her father to tell the First Vision story to the missionaries who were visiting. She remembered that Joseph went into the woods, started to pray, was overcome with darkness, and that the darkness dispersed with the appearance of Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ. “Then the bunny came out of the log,” she reported. Her parents were surprised and found humor in this comment; they later realized it came from the Joseph Smith’s First Vision Living Scriptures video. Linda Crandall, personal interview by Kendra Williamson.

[28] See Karen Lynn Davidson, Our Latter-day Hymns: The Stories and the Messages (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1988), 54–55.

We wish to thank Kendra Crandall Williamson for substantially editing and greatly improving this essay, and we also thank the editors and reviewers of this important volume for helping us refine this chapter.