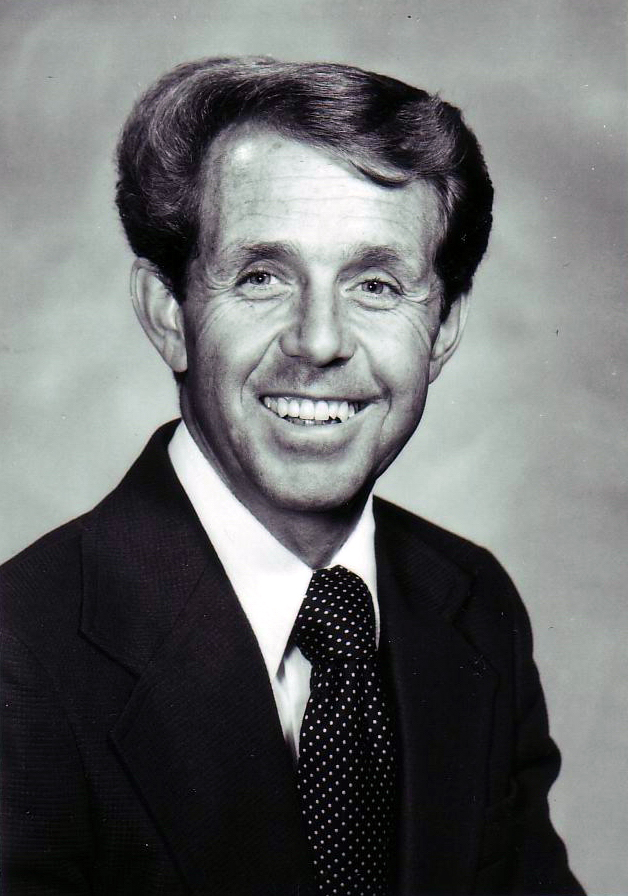

Kenneth W. Godfrey

Matthew C. Godfrey and Kenneth W. Godfrey

Kenneth W. Godrey and Matthew C. Godfrey, “Kenneth W. Godfrey,” in Conversations with Mormon Historians (Provo: Brigham Young University, Religious Studies Center, 2015), 233–74.

Kenneth W. Godfrey retired after thirty-seven years as an administrator and teacher in the LDS Church Educational System. His research and writing has focused on Mormon history and Cache Valley, Utah, history. He has published a number of books, including Women’s Voices: An Untold History of the Latter-day Saints; The Diaries of Charles Ora Card, The Utah Years, 1871–1886; Blue Ribbon Lives: The Junior and Norma Miller Story; and Logan, Utah: A One Hundred Fifty Year History. He is also the author of numerous articles and essays and has served as the president of the Mormon History Association.

Matthew C. Godfrey, historian and volume editor with the Joseph Smith Papers Project in the LDS Church History Department, has written extensively on the Church’s involvement in the beet sugar industry of the Intermountain West. Godfrey has a PhD in history from Washington State University and is the author of Religion, Politics, and Sugar: The Mormon Church, the Federal Government, and the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company, 1907–1921. Before his employment with the Church, Godfrey worked for eight and a half years as a historical consultant, serving as president of Historical Research Associates Inc. in Missoula, Montana.

The Interview

M. Godfrey: I thought maybe you could just start off by talking a little bit about your youth, especially such things as your family, school, teachers, the Church, or whatever else that may have influenced you to pursue Mormon history or teaching.

K. Godfrey: I grew up on a small farm in northern Utah. There were long winter evenings after the chores were done, and our home had only radio contact with the outside world. We didn’t have a telephone; there was no television in those days. Early on in my life, I developed a great love for reading. I remember that my mother read to me when I was a little boy, and then after I could read myself, I would sometimes spend those winter evenings reading books. I went through most of Jack London’s series, beginning with Call of the Wild, and I read Drums along the Mohawk, Northwest Passage, Last of the Mohicans, Leatherstocking Tales, and books like that. So I think that helped me become interested in the study of history. When friends and relatives came—many of whom were extremely gifted storytellers—I liked just sitting and listening to them tell stories about family, experiences they had on the farm, and experiences they had with each other. One of the great attributes of really good historians is that they are good storytellers. I picked up some of those qualities from listening to the good storytellers in my family relate those experiences.

When I enrolled in grade school, one of my favorite classes was a Utah history class. My teacher told me I was really good in that area, and on my exams, she always praised me and just gave me encouragement. I also liked world history in high school as taught by my teacher C. B. Johnson, so I guess there were things like that that sparked my interest in history, although I never thought at that point that I would major in history. I was still thinking about being a farmer, but I was not absolutely certain as to what I wanted to be. I knew I liked reading history even as a young boy, although I haven’t mentioned very many history books in that litany, but Northwest Passage was sort of a history book, as was Last of the Mohicans. At least they gave readers some kind of a feel for early American history.

M. Godfrey: What was it about history that you liked so much?

K. Godfrey: I think it was Carlyle who first said that all history is biography. I liked reading about people and what they had accomplished. I liked reading about famous people—presidents of the United States especially and Napoleon and some European greats like Catherine the Great of Russia, Peter the Great, and some of the English kings. I guess I liked the biographical aspects of history more than its other aspects. There were parts of history that I didn’t really like. I was never overly keen on discussions of waterways and industrial history and things like that. I was more interested in people than I was in events, I guess, or in theoretical history.

M. Godfrey: Will you talk a little bit about the educational background of your family when you were growing up?

K. Godfrey: My mother was a good student. She was the valedictorian of her class in the Clarkston School, which was a combination of a grammar school and a junior high and which even offered one year of high school. She was very good in spelling. My father was not a good student. He attributes that to the death of his mother when he was two years old. He felt somewhat isolated from the family and from his stepmother. My own mother helped him out in school. He became a better student after he was held back one year and was in the same grade as my mother. But Dad was interested in the study of the gospel. When he went on his mission, his first companion was the district president, which, at that time, meant that my father spent quite a bit of time alone while the president was away on district business. President Steed always left him with an assignment. For example, he told him to memorize the first section of the Doctrine and Covenants and also to memorize other scriptures. Then, my father studied the principles of the gospel. So in our family as we were growing up, we talked frequently about gospel principles while we were working in the hay or milking cows. In that sense, he influenced me, even though neither my father nor my mother graduated from high school, nor had their parents. I was the first one in our family to graduate from high school.

M. Godfrey: What motivated you to go to college?

K. Godfrey: I have often thought about that. I think following World War II and the introduction of the GI Bill, which enabled many young people to go to college, along with the technological advances that World War II seemed to cause, a college education became even more valuable if one wanted to succeed in life. As a result of those things, most of the young people in my hometown started to go to universities. There had been a group of boys, just before my own peer group came along, in which only one or two graduated from high school, but now there was my group, where almost everyone started college, and I think I was sort of swept up with that group. So without any real thought or real motivation, I decided I would go to college. I had saved a little bit of money—I owned a cow, my father allowed me to keep the milk check, and I had saved enough money to put me through a year of college. So I just ended up at Utah State, which was close to where I lived. My parents gave me food—when I would hitchhike home at the end of the week, Mom baked a chicken or made some soup and other food. Then, I would take that food back to my apartment, where I cooked for myself, and lived on that during the week. I was able to make it through school on around eight hundred dollars that first year. I didn’t like school that much my freshman year, so I didn’t go the next fall quarter. Then, I decided to go to Ricks College with my cousin, and I really learned to like college there. I enrolled in a political science class that I really enjoyed. I was around educated people on my mission and could see the value of education. By the time I had finished my mission, I was pretty well set on going back to the university.

M. Godfrey: What was the first year that you went to Utah State?

K. Godfrey: I started in 1951; so it was the school year of 1951–52.

M. Godfrey: Then you went to Ricks in the fall of 1952?

K. Godfrey: Ricks College was a little different from some other colleges at that time. They started their winter quarter in December, but most colleges started winter quarter in January, so with that early start, I enrolled around December 5, 1952.

M. Godfrey: You touched on this a little bit, but what was it about Ricks that got you more interested in school?

K. Godfrey: I was living with my cousin, whom I really liked, and then we met another cousin team that was living together—Tom Hatch and Herman Hatch, who were from Bancroft and Chesterfield, Idaho. Herman came from a family whose mother made sure they all knew how to play the piano and another musical instrument, and they lived on a rather large farm. His father had been the bishop for about fifteen years in Chesterfield, so they were a cultured family, and Herm and I developed a really close relationship. We both liked baseball and the same kind of music, and I think it was the friends I had when I was at Ricks that helped me really like school. I also had teachers who were really good. One was Keith Melville, who later became a political scientist at Brigham Young University and ran for Congress. He was an exceptional teacher—very demanding. But I just liked the classes, and the social life was extraordinary. So all of those things culminated in my being able to see what school was really like. My grades picked up as a result of my being happy. I guess I had learned how to study a little bit better by this time, so my grades were better.

M. Godfrey: At this point, before you went on your mission, what were your career goals, or did you have any at that point?

K. Godfrey: Sometimes I didn’t think I did, but I recently read the letters I wrote home to my parents and to my brother and my sister while I was on my mission, and I still thought I was going to be a farmer. I did have a minor in agriculture by the time I went on my mission. But then I met this lawyer in St. Petersburg—he was the branch president, so we were with him a lot. He gave me some law books, and I concluded by the time I had completed my mission that I would be a lawyer.

M. Godfrey: When did you leave on your mission?

K. Godfrey: I left on my mission in November 1953.

M. Godfrey: And it was the Southern States Mission?

K. Godfrey: Yes, that comprised five states at that time—South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, and Alabama. My mission had a great influence on me academically and also in many other ways. I learned on my mission that I could teach fairly well. I also learned that I could lead other missionaries, and I became a fairly good speaker, which was rather remarkable because I had suffered from stuttering when I was a boy. I think in some ways my stuttering may have made me a better listener, as I didn’t participate in conversations quite as much, but by the time I arrived in the mission field, I had pretty much conquered my stuttering problem and felt some satisfaction in being able to have audiences respond to what I was saying and in being able to tell that they were responding. That influenced my life profoundly.

M. Godfrey: What were some of the classes you taught when you were on your mission?

K. Godfrey: I taught some classes in the Mutual Improvement Association in some of the small branches, and then we frequently held cottage meetings. We invited non-Mormons in the neighborhood, and we would have fifteen or twenty in those meetings. I taught one of the discussions on the Godhead or the Apostasy or the Restoration, or something like that. And then I sometimes taught missionaries. After I became the supervising elder, I had sixteen missionaries under my direction. We had monthly meetings in which I provided in-service training. Then, I also started a district newsletter at that time, which I wrote articles for, edited, and sent to all the missionaries in the area where I presided.

M. Godfrey: Did you have any teaching experience before your mission?

K. Godfrey: Well, when I was a teacher in the Aaronic Priesthood, not only was I the president of the teachers for one year, but I also taught the lessons to the other teachers. That was my only teaching experience up to that point.

M. Godfrey: Was that unusual to have a member of the quorum actually teach the lessons?

K. Godfrey: That’s the only time I can ever remember it happening in our ward—or anywhere else.

M. Godfrey: Why did they have you teach for a year?

K. Godfrey: I have no idea what the bishop had in mind when that happened. He knew I was there every Sunday. I can’t imagine that I did a very good job, but the leaders stuck with me, so I did the teaching. We had a fine manual, and I didn’t stray much beyond it. At that age I didn’t do a lot of research before teaching.

M. Godfrey: So your mission went from 1953 until . . .

K. Godfrey: 1955. I got home in November 1955.

M. Godfrey: What did you do after you got home?

K. Godfrey: As soon as I returned from my mission, I got a job with the JC Penney Company working as a stock boy. I was able to earn a little money doing that. Then, when school started, I enrolled in winter quarter of 1956, and I got a job unloading cars of coal for the Yeates Coal Company in Logan. I also took a class that prepared me to be a custodian at the university, and then I was hired as a janitor. I worked as a custodian part-time the rest of my time at Utah State. I was able to make enough money to pay for tuition and books and rent and all of those things, and that allowed me to finish school. So actually I supported myself from 1956 on. My grades were not good enough for a scholarship. Actually, I never applied for one either, so I pretty much paid the cost of acquiring an education.

M. Godfrey: What made you decide to go back to Utah State rather than to Ricks again when you got home from your mission?

K. Godfrey: Well, when I was going to Ricks the first time, it was a four-year school that gave bachelor’s degrees, and as I mentioned before, I had already been to Utah State for a year before I went to Ricks. I had two quarters at Ricks, which meant that I was almost ready for my junior year in college. When I returned from my mission, Ricks had gone back to a two-year school, so there really wasn’t much enticement for me to return to Ricks for just one quarter. Also, it was less expensive if I went to Utah State, because spring quarter I lived at home and drove back and forth to school with some other people who lived in Cornish, and I was able to avoid paying rent. Those were the two reasons I came back to Utah State.

M. Godfrey: Then you were at Utah State from winter quarter of 1956 until . . . When did you graduate?

K. Godfrey: I stayed and finished a master’s degree at the end of the summer of 1958, so I was there from 1956 to 1958. But I went year-round. I went every summer except the summer of 1956. After Audrey and I were married in the fall of 1956, however, I went year-round, and that is why I was able to finish a bachelor’s and a master’s in three years as well as certify as a teacher.

M. Godfrey: Was there a teacher or a class that particularly influenced you during these years at Utah State as far as your future career path goes?

K. Godfrey: Yes. Spring quarter of 1956 I took a contemporary politics class from Milton R. Merrill, who was the dean of the College of Business and Social Sciences. I had never had a class that motivated me like that class did. As much as I liked Keith Melville at Ricks, Milt Merrill was much better as a teacher. After taking that class, I decided to major in political science. So I took every class that Milt Merrill offered after that time, and he gave me lots of encouragement. I used to clean his office, and he would talk to me as I cleaned. He told me that I could succeed academically and that I was a good student. He had his doctorate from Columbia University, and I just can’t overemphasize the influence he had on my life academically.

M. Godfrey: Was he actually encouraging you to go on and get a PhD at that point? What was he encouraging you to do?

K. Godfrey: He encouraged me to get a master’s degree, and then he also encouraged me to go on and get a PhD. When I took the Graduate Record Exam, he said that I achieved the highest score on the social science part of that exam that anybody at Utah State had received up to that point. So that gave me a lot of confidence. Then, he later wrote a really fine letter for me when I enrolled in a PhD program at the University of Southern California.

M. Godfrey: At that point, when you switched your major to political science, what were you thinking you were going to do in your career?

K. Godfrey: I had a couple of options. One, I was still thinking of going on to law school. I was also considering going into the diplomatic corps and becoming a diplomat. There was also the possibility of working for the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Then there was the possibility of teaching. When I returned from my mission, they called me as the Gospel Doctrine teacher in my home ward. We were studying the New Testament. A lot of the class members gave me some positive reinforcement and told me I was a good teacher. I found out that I really liked teaching.

Then, my wife and I found out in the spring of 1957 that we were going to have our first child. I ought to mention that my wife, Audrey, was a really good student. She had a great influence on me because she was able to help me with the papers I was required to write for classes. She was very good in English and knew how to put the punctuation in the right places and knew how to spell extremely well. As a result of her editing of those papers, my grades picked up in those classes. What I was producing was better quality than what I had been able to produce alone. Audrey was much like I was in terms of her background. She was putting herself through school. Not only did she work part time, but she also had scholarships. When we got married, we both supported each other in our academic pursuits.

When we found out that we were going to have a baby, since we were both putting ourselves through school, we realized that I was going to have to find a way to make more money. So I stopped pursuing a master’s degree in political science for one quarter and took all of my education classes to become a certified schoolteacher. In the process, because I had loved teaching the Gospel Doctrine class so much, I also pursued the possibility of becoming a seminary teacher. When I did my student teaching, I received very high marks from my supervisors and my cooperating teacher. I had a cooperating teacher who was quite old, and 1958 just was not his most effective year. He had some very challenging classes, and because I was young I seemed to relate better to the students. I told jokes, and they laughed. They gave me very high marks on the student evaluations. Then Church leaders offered me a job, and that is how we decided we would not go on to school at this point because we had to make a living. I began to teach seminary in 1958.

M. Godfrey: Where did you do your student teaching?

K. Godfrey: At Logan High School. I taught one political science class for Leo Johnson, who was a fine high school civics teacher and a fine historian himself. Then my other class—I had to teach two—was a seminary class.

M. Godfrey: Your first job, then, as a seminary teacher—when did you get that and where was it? Maybe you could talk a little bit more about becoming a seminary teacher as well.

K. Godfrey: When I started to explore the possibility of teaching seminary, in my first interview the interviewer said to me, “What are your long-range goals?” I said to him, “Eventually I want to get a doctorate.” He said, “We don’t need people with doctorates in the seminary system. It’s a hindrance to them instead of a blessing.” He made me so angry that I decided I would do such a good job student teaching that he would have to hire me. So when I got all of those good evaluations in and when my cooperating teacher gave me such a good recommendation, I was interviewed by Elder A. Theodore Tuttle, who had just been made one of the seven Presidents of the Seventy and who was a General Authority. He was also a supervisor in the seminary system. He came and interviewed me, and he said, “What are your long-range goals?” I swallowed and looked him in the eye and said, “Eventually I want to get a doctorate.” He said, “We love to have our seminary teachers with doctorates. We will do everything we can to help you get one.” So that really gave me some encouragement.

Anyway, I was hired. In August 1958, I started to teach seminary in Firth High School in Firth, Idaho. I was principal of the seminary, but I was principal over no one but myself. At that time, seminary teachers taught Old Testament, New Testament, and Church history in the same year. So I started to teach those courses, and I had challenges that almost every teacher has. But the students seemed to respond, and I had quite a large increase in enrollment the second year. This impressed my supervisor, and he gave me extremely high marks. I told him of my desire to get a doctorate, and I received a call in February 1960 after I had been in Firth for two years. Elder Packer was on the phone, and he asked me if I would serve as an assistant coordinator of seminaries in the Southern California area. My office would be next to the University of Southern California, and that way I could start work on a doctorate. So he followed through on what Elder Tuttle had told me, and they moved me where it would be easy for me to take a class or two each quarter and pursue a doctorate.

M. Godfrey: Was that something that was fairly unusual—to move someone who had been in the system for only a couple of years into an administrative position? Or was that fairly standard back then?

K. Godfrey: The Church Educational System was growing rapidly at this time. The early-morning seminary program was not very many years old—I believe it started in 1956, if I remember right. So it was a little bit unusual. When I went to Los Angeles that year, I went with Marvin Higbee, who had been in the system about the same number of years as I had been. He was going to teach institute. And I went with George Horton, and he had been in seven or eight years. I guess I was still perhaps the youngest one of the group that went to Los Angeles. I think it was because of Lester Peterson’s high recommendation of me as a teacher that allowed me to secure that job at that early point in my career.

M. Godfrey: Who was he again?

K. Godfrey: He was the coordinator, as we called them back in those days, headquartered in Rexburg. He was a wonderful man to whom I felt very close. He was very good to me.

M. Godfrey: Why did you decide to get your PhD in history rather than political science? Or, at this time were you planning on getting your PhD in political science?

K. Godfrey: Yes, I was still studying political science. I still liked political science. After two years in Los Angeles, they moved me to San Francisco, and I became the coordinator of seminaries and part-time institutes in San Francisco. Then, I applied for and received a sabbatical leave and was admitted to the University of Utah to work on a PhD in political science. I began to study languages; in fact, I passed the French exam. As I pursued political science, I came to the conclusion that I could not use very much of what I was learning in the seminary or institute classroom. By this time, I had taught institute in Northern California for a whole year. I guess that is another story. So Audrey and I talked, and I came to the conclusion that if I was going to stay with the Church Educational System—by this time, I had decided that I would stay with the Church Educational System—it would be to my advantage and to the students’ advantage if I really knew what I was talking about. At this point, Brigham Young University was offering a doctorate in the history of religion, and Church history was one of the major fields of emphasis. Another field was world religions, and yet another field was Christian history. They also allowed me to use political theory as my fourth field of study. So I transferred to Brigham Young University and began to study those four fields extensively. I found that out of the four, although I’ve taught classes in each of those areas, that the Church history part of it appealed to me more than did the other three academic areas in which I became proficient.

M. Godfrey: When was this that you went to BYU to study?

K. Godfrey: I went to the University of Utah and began in the summer of 1964. After fall quarter ended, I enrolled at BYU. BYU was on semesters by then, and their spring semester began about the middle of January. So I started there in 1965 in the middle of January. We moved to a fourplex in Orem. They asked me to teach part-time at Brigham Young University. I taught Book of Mormon, and then I taught Church history, all while I was working on my doctorate.

M. Godfrey: Was this the first time that you had really studied Mormon history in depth?

K. Godfrey: When I first went to the University of Southern California, the assistant dean of the College of Public Administration was a Mormon from Logan, Desmond Anderson. He had been the student body president at Utah State University and then went on and got a doctorate. He hired me as his administrative assistant, and my major responsibility was reading the Journal of Discourses—all twenty-six volumes—and picking out everything that our Church leaders had said in those volumes that pertained to politics or civic affairs. So, in a sense, that was my first in-depth study of what our Church leaders had said and talked about. And there is a lot of history in the Journal of Discourses. But by this time, too, I had read a number of Church history books. I was also around some very bright people in Los Angeles who were always talking about the Church and its history and its doctrine and what had gone on, which highly motivated me to learn more. Also, at the University of Utah I had studied religious philosophy. I had one course in the history of philosophy, which was a history course even though it was taught by a philosopher; he was a philosopher of history. So I had had some in-depth study in the areas that I’ve mentioned. But it really was at BYU where I first got into primary sources and where I researched things that other people had not studied.

M. Godfrey: Was there a particular class or teacher at BYU that had an influence on your later career as a Mormon historian?

K. Godfrey: I think I would have to say that Gustive O. Larsen had an influence on me. He was not the greatest teacher I have ever had, but he was a fine researcher and a good writer and published a number of books. He was very kind and thoughtful with me. He made demands on me that he did not make on his other students, and at the same time he gave me encouragement and taught me how to write good historical papers. In that sense, he was a great influence on me. Just before he died, he told me I was the best student he had ever had, so perhaps he liked me as well as I liked him. Maybe those are the reasons he was able to influence me.

M. Godfrey: Why do you think he made more demands on you than on other students?

K. Godfrey: I think he believed that I would research more deeply, and he, selfishly in a way, wanted to read what I would come up with. For example, in one graduate seminar that I took from him in the summer, he said to the rest of the class, “Now the bulk of your grade is going to be determined on the paper you write. You can pick your subject, but it’s got to be approved by me. You’ll all be able to pick your subject—except for you, Godfrey. You can’t. I want to see you after class.” So after class I went up to him and asked him what he wanted, and he said, “I want you to write a paper on the history of black members of the Church and the priesthood. If you want to get a grade out of this class, that’s what you will write on.” So it was that kind of experience that I had with him. That was a significant experience because, even though we only had four or five weeks in the class, I was able to produce a fairly good graduate paper. Later, Lester Bush told me that he had seen that paper in the BYU Library, and it motivated him to write his famous treatment of blacks and the priesthood that appeared in Dialogue and won an award. I was part of the motivation for his writing that excellent piece, and he used some of the same format that I had used as he wrote. But, of course, he had years to research, so he did a far better job than I was able to do in the short period of time I had.

I also ought to say that I had four teachers who really influenced me. I’ve already mentioned Milt Merrill. Then there was Dr. Rhodee at the University of Southern California, and then there was Waldemar Reed at the University of Utah, who taught me the history of philosophy. One thing that all three of those men had in common was that they really knew the field in which they were teaching. They just knew everything about it, it seemed to me. I decided that that was the kind of teacher I wanted to be—someone who really knew what he was talking about. That is another reason I changed and went to BYU—so I could learn the field of Church history and really know what I was talking about. Then, the fourth teacher was a teacher at BYU, and that was Louis Midgley, who was a political scientist. His interest in me and his encouragement and the way he was able to look at scholarship and Church doctrines influenced me. One quarter he and I actually took a class from Hugh Nibley together and sat by each other. Midgley had an enormous academic influence over me, as well as those other three men.

M. Godfrey: Maybe you could talk for a little bit about your dissertation topic and how you came to write on what you did.

K. Godfrey: Well, as I got toward the end of my PhD studies, I had written a number of papers about politics in Utah. I had written one paper for Thomas Alexander on Frank J. Cannon. I was really interested in the coming of the two-party system to Utah and had tentatively thought that that’s what I would focus on in my dissertation. As I was talking to my major professor, who was Milton V. Backman, he reminded me that Max Parkin had received a master’s degree writing a thesis on the causes of conflict in Kirtland, Ohio, between Mormons and their non-Mormon neighbors and that Leland Gentry was finishing a dissertation on Missouri. He said, “But no one’s done Nauvoo. So why don’t you consider writing a dissertation on why Latter-day Saints did not get along with their neighbors in Hancock County.” I realized at this point that it was easier getting your doctorate if your major professor liked the topic of your dissertation rather than pursuing a topic that he was not overly enthused about. I also thought the topic sounded interesting. Little did I know what lay ahead, but that’s how I got into my topic. It was with the encouragement of Dr. Backman, who, by the way, was as fine a major professor as one could ask for. He had earned a PhD at the University of Pennsylvania and demanded high-quality work. He was also kind, thoughtful, and insightful. I could not have had a better critic and guide in writing my dissertation.

At that time at BYU, all dissertation topics in the field of religion had to be approved by the Church Board of Education. So after I had done some of the research and had written a chapter or two, one day the head of the Church History Department—Chauncey Riddle—invited me into his office and told me that the Board of Education had turned down my topic, saying I could not write on the causes of Mormon/

M. Godfrey: That is interesting. So once you finished your PhD, where did your career go after that?

K. Godfrey: When I finished my doctorate, I was appointed the director of the Stanford Institute of Religion at Palo Alto. It was the same year that Dialogue was getting underway, which was published by Eugene England and Wesley Johnson. Wesley was a professor at Stanford, and Eugene was finishing his doctorate in English there. Eugene was also a part-time instructor at the institute working with me. By this time BYU Studies, which was then edited by Charles Tate, had accepted an article I had written that was entitled “The Road to Carthage Led West,” in which I argued that the same factors that had caused the death of Joseph and Hyrum Smith also led the people of Hancock County to expel the Mormons and caused them to come west to Utah. It was well known that Carthage is east of Nauvoo. In fact, one of the reviewers of the article, Richard L. Anderson, wrote a little note, and he said, “I don’t completely understand this title.” But that’s what I had in mind—that even though Carthage was east, it led the Mormons west. Anyway, that article was published while I was at Stanford, and I got a handwritten letter from Juanita Brooks saying it was the best article that she had ever read on the subject, and she was astonished that a member of the Church Educational System would have been allowed to write an article like that. T. Edgar Lyon also went to Chuck Tate and said, “How were you able to publish that article? That’s the kind of article I’ve been wanting to write but thought I would be fired if I were to write it.” So I got quite uneasy with that kind of talk. But I was flattered that Juanita Brooks had liked it because I was wondering what the reaction was going to be. Charles Tate told T. Edgar that he liked the article and that he didn’t ask anybody—he just went ahead and printed it. That article sounds tame now, but at that time, apparently, it was quite bold; but it was accurate. I was never visited with about it, so my history-publishing career was launched. The article came out while I was at Stanford, as did another article published in Dialogue on the great German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

M. Godfrey: Did you have any involvement with the founding of Dialogue or anything to do with its early years at that time?

K. Godfrey: Eugene England had taught early-morning seminary in Victorville, California, while he was in the air force, and that was part of the area I supervised. I had been given the Victorville Stake specifically as one of my responsibilities when I worked as an assistant coordinator, so I first met Eugene then. I would visit his class from time to time, and we would sometimes talk about how it would be nice if there were a more scholarly journal that people in the Church who were interested in intellectual issues and intellectual ideas could publish in that had more rigorous scholastic demands than did the official Church publications. So, just as I was finishing my doctorate degree, I got a letter from him one day in which he invited me to become a member of the original board of editors of Dialogue. It was a nice letter in which he said, “We’re going ahead with some of the things we talked about a few years ago.” So I was invited to be on the first board of editors, and they actually prepared a flyer that they sent out to prospective subscribers with my name on it.

Right after the flyer appeared, I got a call from President William E. Berrett, and he invited me to come to his office. He said, “I understand you’re going to be on the board of editors of Dialogue.” I said, “Yes, isn’t that wonderful? I’m really excited.” He said, “Let me tell you a story.” So he told me a story about how when he was in the Church Educational System in the 1930s, he and Sterling McMurrin were put in charge of a magazine for the Church Education teachers, and they had published only one or two issues when the President of the Church had stopped its publication. Then, President Berrett said, “It’s really dangerous to publish a journal, and it upsets a lot of people if the articles aren’t just right.” He said, “It might have been nice if you had talked to me before you accepted.” I said, “Oh, President, I’m really sorry. I had no idea that I should have done that. I’m sorry that I wasn’t bright enough to realize that I should have asked for permission. If you don’t me want me on the board, I’ll resign right now.” He said, “No, I think it will be okay; you go ahead.”

Shortly after that, I learned that President Berrett’s first assistant, who was Alma P. Burton, was concerned because earlier I had gone into his office and had said something about Dialogue being organized and how good I felt about it. I could tell he did not have the same enthusiasm for it that I did, but he didn’t say anything, so I left his office. Later, after my encounter with President Berrett, I learned that Alma Burton, who was also my stake president, had said to someone that I had disregarded his counsel and had gone ahead with being on the board of directors. He only lived about four or five houses from where we did in Orem, so I called him because I didn’t want my stake president to think that I wouldn’t honor his counsel. I didn’t want him angry with me. I went over to his home, and we sat down and had a long talk. He told me that I shouldn’t be on the editorial board of Dialogue because if I did, I would never become a General Authority. I told him that I had never aspired to that office and didn’t think I’d be a General Authority anyway—or something like that. We continued to talk. He must have spent an hour or an hour and a half with me. But he didn’t tell me absolutely not to be on the board of editors. I guess it was because he already knew that President Berrett had given his approval to go ahead.

As I came home, I really didn’t feel very good. I talked to Audrey, and we talked quite a long time about my feelings. We finally came to the conclusion that even if your stake president’s counsel was not based on good reasons that there was something sacred, in a sense, about his counsel. I had taught in my classes that there was something special about the counsel and advice of our Church leaders, and if I really believed that, this might be a good time to honor what I was teaching. So we decided I would not serve on the board of editors. I sent in a letter explaining to Eugene what had happened. Immediately after he received the letter, he called me on the telephone and told me that he was very disappointed and that he was going to go to President Tanner because I had indicated in the letter that I was following the advice of my stake president. I didn’t want to become the chief topic of discussion between the first counselor in the First Presidency and the editor of Dialogue, so I told him, “No, Eugene, don’t do that. This is my own decision.” So that’s part of my association with the beginnings of Dialogue. I never did serve on the board of editors, but I have published two or three articles in Dialogue over the years.

M. Godfrey: When was this happening?

K. Godfrey: This was 1967 and 1968—the same time they discovered the papyrus back in New York. I had one other involvement. I don’t know whether this is interesting or not. I was acquainted with Paul Cheesman at BYU because I had met him on my mission in Miami, Florida. He was first counselor in the district presidency down there and was doing quite well as a photographer. Then he decided that he would give up the photography business and come to BYU and become a religion teacher. When he was in the district presidency, he had become good friends with President Harold B. Lee. So when he was writing his master’s thesis, President Lee allowed him to look at the various accounts of the First Vision found in the Church Archives, some of which no scholar up to this point had seen. So Paul did his master’s thesis comparing those different accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision and the implications thereof. Jim Allen was preparing an article for the Ensign (or perhaps the Improvement Era) on the different accounts of the First Vision after Paul had written his thesis, and they allowed Jim to look at the different accounts as well. Paul discovered another original account as Jim was finishing up his article. I met Jim on campus at BYU one day, and I said, “Have you seen this new account of the First Vision that Paul Cheesman has just discovered?” Jim had not, but he soon examined it and was able to include it in his article. When I was at Stanford, Wesley P. Walters, who was a Presbyterian minister in the Midwest, sent an article on Mormon origins for publication in Dialogue. Eugene England brought that article to my office and asked me to look at it and to recommend whether they should publish it. I told him after I’d read it that I didn’t think they should publish it unless they also published a response. He said, “Well, who can respond to this?” I said, “Paul Cheesman and Jim Allen at BYU have worked in this area. Why don’t you send it to them and see what they say?” So they sent the manuscript to BYU. It created quite a stir. Truman Madsen and Brother Cheesman, if I remember right, went to Salt Lake City, and the Church appointed a special committee of scholars to go back east and mine all of the records they could find about Mormonism. That is when Larry Porter went back and lived in Martin Harris’s home and did all of his research and when Milt Backman went back and did a lot of research in the Kirtland area and in New York as well. Then Eugene England had Richard Bushman write a response to Wesley P. Walter’s article when they published it in Dialogue, so that is a little bit of the background regarding that article.

M. Godfrey: So when were you at Stanford?

K. Godfrey: From 1967 to 1968.

M. Godfrey: And then from there . . .

K. Godfrey: The CES leaders changed the organization of the Church Educational System and began to appoint a new level of leadership they called division coordinators. I was asked to become the division coordinator of seminaries and institutes in Arizona and New Mexico, and we moved to Tempe. Just after we moved to Tempe, my second academic article appeared in the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. That was an article on Joseph Smith and the Masons. So that was my first article published in a journal other than a Mormon journal. While we were there in Tempe, Audrey and I also wrote quite a long article that appeared in the Ensign on pioneer women crossing the plains. Between the time I had finished my PhD and the time we went to Stanford, President Berrett hired me to go through all of the Church periodicals and Xerox every article that pertained to some aspect of Mormon history for use in the curriculum department of the Church Education System. So I had amassed a huge reservoir of articles that had appeared in the Millennial Star and in the Messenger and Advocate and those old journals, and Audrey and I then wrote this article based on some of the research we had done.

M. Godfrey: What made you decide to focus on pioneer women for that article?

K. Godfrey: We decided as we were talking that there were a number of stories I had uncovered that no one had published before and that women were not often the focus in Mormon literature, and it was time perhaps that their story be told.

M. Godfrey: Was it around this same time in the late 1960s that you first became involved in the Mormon History Association?

K. Godfrey: Yes. As I was finishing my doctorate in 1967, the Utah Council of Humanities (I’m not sure I’ve got that title correct) had its meetings at Utah State University, and the Mormon History Association sponsored a session at those meetings. Leland Gentry and I were invited to come and give papers at those meetings. He spoke on Missouri; I spoke on Nauvoo. George Ellsworth, a history professor at Utah State, commented on those papers, and that was my first experience with the Mormon History Association. When I was at Stanford, the Western History Association met in San Francisco, and the Mormon History Association sponsored an evening meeting at Stanford. I was asked to comment on a paper that John Sorensen gave. Then, when we lived in Arizona, the Western History Association met in Tucson, and I was asked to participate on a panel with some historians evaluating where the study of Mormon history was and where it would be going. So, by 1970, very early in its history (it was organized in 1965) I had already participated in three meetings.

M. Godfrey: Could you talk a little bit about that organization’s initial years and what it was like to be involved in the Mormon History Association at that time?

K. Godfrey: For young historians, it was a wonderful time. The organization was not large. For the first meeting away from the Wasatch Front, we decided to try something new, and we went to Independence, Missouri, in 1972 and had sessions as well as site papers. When we attended these meetings, we were all pretty much in the same motel, and we all congregated in somebody’s room and talked until one or two o’clock in the morning. We all got acquainted with each other. That’s where I first became acquainted with Davis Bitton, Leonard Arrington (who was my economics teacher in 1951 at Utah State University), Robert Flanders (the RLDS historian), Dean Jessee, Paul Edwards, and Richard Howard. Anybody who was writing in the field of Mormon history was there. It was really wonderful to put faces and personalities with these people whose writings I was reading. Those after-hour bull sessions were just wonderful. Several times Reed Durham and I stayed together, and everyone would come to our room. It was a wonderful way for us to exchange ideas and find out what we were researching. It was just a wonderful time in my life.

M. Godfrey: Did you serve in any position on the board of the association or anything like that in these early years?

K. Godfrey: Yes. In the early 1970s I was asked to become the secretary and treasurer of the Mormon History Association, and I served in that position for maybe four years. While I was serving as secretary/

M. Godfrey: For how long?

K. Godfrey: I was released when I was called as a mission president. That was 1975.

M. Godfrey: How did you come to write the book Women’s Voices? I know that wasn’t published until the 1980s, but it seems that its history dates back into the 1970s.

K. Godfrey: Yes, it does. It starts way back then. There were three factors that led to our being asked to write it. One, as I have indicated, Audrey and I had written an article on pioneer women. Not too many months after that appeared, I published another article in the Ensign that was titled “Feminine-Flavored Church History.” It was in a section sponsored by the Church Educational System, and I argued that in our teaching in the Church Educational System we should not forget women and their contributions. Then, I won an opportunity to participate in the Sidney B. Sperry Symposium. In the early days of the Sidney Sperry Symposium, you submitted a proposal, and they selected only three individuals to actually come to BYU and deliver a paper. I was selected to deliver a paper I titled “The Gentle Tamers.” It was on women’s contributions to Latter-day Saint history. So I published those two articles alone and then the one with Audrey. One day I received a letter from Leonard Arrington. It was shortly after they had announced that there was going to be a twenty-volume history produced for the Church’s sesquicentennial, and the authors had been appointed to write these histories. Also, they were going to do a series of books that were publications of original documents. Leonard asked that I write one on Mormon women.

M. Godfrey: What year was this?

K. Godfrey: Let’s see. This must have been about 1973.

M. Godfrey: So it was after he was appointed as Church historian.

K. Godfrey: Yes, after he was Church historian. He also indicated that Audrey should be involved as well. So we wrote back an enthusiastic acceptance. Then, I was granted a sabbatical leave for half a year, and I commuted from South Ogden to the Church Archives in Salt Lake every day.

M. Godfrey: For clarification—you had been in Arizona in that position until when?

K. Godfrey: I was in Arizona for three years, and then they asked if I would come to Ogden and serve as the division coordinator in the Ogden/

M. Godfrey: And that was what year?

K. Godfrey: 1971–75.

M. Godfrey: So you were saying that you would commute, then, on your sabbatical from South Ogden to the Church Archives?

K. Godfrey: Right. And I would make Xerox copies of women’s diaries, bring them home, and Audrey would read them. Then, when we had collected this mass of material, we started to edit those diaries for publication in a book. We had the manuscript quite a ways along when I was called as a mission president, so we talked with the editor of the Church Historical Department, Maureen Ursenbach Beecher at that time, and it was decided that, as much as we were going to be gone, Jill Derr would become involved in the project and would work on it. When we returned from the mission field and looked at the manuscript, we could tell that Jill had done a lot of work—probably as much as we had. So we made the decision to include her as a coauthor. Then it came out in, I believe, 1982. It’s been published since that time. There have been three different covers, and the book sold really quite well. Leonard Arrington mentions in his autobiography that it was one of those books that didn’t cause any flak when it appeared. It got a good review in the Nebraska Historical Quarterly by Professor Anne Butler, who later came to Utah State University and edited the Western Historical Quarterly. So it got good reviews. It’s been a good, substantial book.

M. Godfrey: What contribution do you think it made to the field of Mormon history at the time it was published?

K. Godfrey: Well, I think it was among the first books to be published that emphasized the role of women in Latter-day Saint history. There have been some that have said it was the first. It was definitely the first in terms of Mormon Studies. That was a field that had been long overlooked and still probably does not receive the attention it should.

M. Godfrey: You had talked about how, prior to being called as mission president, you would do research in the Church Archives. This—the period when Arrington was Church historian—is often thought of as “Camelot,” the era when there was so much in the Church Archives that was open for research. Could you talk a little bit more about researching in the archives and maybe about some of the most significant or exciting documents you were able to look at as you researched there?

K. Godfrey: Let’s go back earlier. In the 1960s, when I began serious research on my doctoral dissertation, I worked in the Church Archives. In those days, when you went to Salt Lake and did research, they checked you in. You had to meet A. William Lund, who was the assistant Church historian in charge of the archives, and he gave permission, or did not give permission, to look at the documents. Then, at the end of each day, you had to show him what you had typed. You couldn’t make copies of anything during that period of time, but you could make typed copies. They furnished the typewriters. He would go through what you had copied on your typewriter, and if he thought it should not be made public, he would deny you the right to take it out. Sometimes he would tear it up right in front of you and say that you couldn’t have it. It was quite an experience to do research without knowing what you could leave with each day.

One day I had noticed a large wall of material all in the same boxes that said something about letters from Nauvoo. So I went to Brother Lund and I asked him what those were. He said, “That’s what we call the unclassified letter file. Those are letters that were written while the Latter-day Saints resided in Nauvoo, either from those who were living there or to those who had relatives living there.” I said, “May I look at those?” He said, “No.” I said, “Why not?” He said, “Well, we have nobody from our department who has been through those letters. We don’t know what’s in them.” He said (and I think he had a twinkle in his eye when he said this), “And you might just find out the Church isn’t true.” So we laughed, and I said, “If I can do that by looking at a batch of letters, it would save us a lot of time and attendance at a lot of meetings.” Then I said, “It really would help my dissertation if I could go through all of those. These are prime sources.” He said, “Well, I’m sorry, you can’t, because as I said we haven’t been through them ourselves.” So I drove back to Provo and went to my office. I happened to be sharing an office that year with Hoyt Brewster, who was working on a master’s degree at BYU, and he was Joseph Fielding Smith’s grandson. So I began to tell him about what had happened and how much better my dissertation would be if I could look at those letters. He said, “Well, let’s write a letter to Grandpa.” I was quite reluctant to do that. He said, “No, Grandpa’s a good man, and he’s kind.” He said, “You write a letter as to why you need those letters, and I’ll write a cover letter to Grandpa, and let’s see what happens.” So I went home and wrote quite a letter. I’ve laughingly said sometimes that it ranks right up there with Romans and First and Second Corinthians.

Within two days, President Smith sent me a letter back and said that I could have access to all of those letters; I could do research using them. So I went to Salt Lake right after that with that letter in my hand, and I had a very difficult time being humble as I was driving north from Provo. I went into Brother Lund, and I said, “I would like to look at the letters in the unclassified letter file.” He said, “Well, I’ve already told you that you can’t.” I said, “Would this letter make any difference?” and I handed him the one that I had from President Smith granting me authorization. He did not look at all happy. Then, he said to me, “Well, I don’t agree with the decision, but he’s the boss, and if he told you that you could, then you can.” So I began to go through all of those letters. While I was going through them, I found a document that pertained to the Council of Fifty, which I knew that no one had ever written about before, because I knew most of the published literature regarding the Council of Fifty. I also knew there was a possibility he might not let me take my copy of it out. So I put my typed copy of the document in the middle of the pile of materials that I had gleaned that day. I had learned earlier that if you asked him about the years he was mission president in England, he would talk about his experiences there and would not look quite as closely at the materials that you had handed him. So, I went in and I asked him how he had enjoyed his mission in England, and he began to talk and thumb through the papers. My heart was pounding. It did not register with him the significance of this one document, and he passed it by, and I got to use it. So, that was one document that I found exciting.

Later, when I did research while on the sabbatical you asked about, it was a different experience. Once you had received approval to work in the archives, then they gave you access to those things that you requested. While I was working on women’s diaries, I also read the diaries of Amasa Lyman and Franklin D. Richards and a lot of material on Heber J. Grant and George A. Smith and other diaries. Had I known what was going to happen later, I probably would have taken even more notes than I did at that time. You asked me about some significant documents, is that correct?

M. Godfrey: Yes, or exciting things you were able to research.

K. Godfrey: I had one other exciting experience with an original document. I was back at the Illinois State Historical Library doing research, and at the time I was doing this research there was a talk circulating among Latter-day Saints called “Joseph Smith’s Little-Known Discourse on Adultery and Fornication.” It was the kind of talk that was demeaning to women and indicated that they were the property of the man, that the man could divorce a woman if she had an alienation of affection, and that no questions could be asked, and these kinds of things. As I was reading in the Mormon collection in Springfield, Illinois, in their archives, I came across a document that Udney H. Jacobs had written. It was in his own handwriting to President Martin Van Buren in which he talked about this pamphlet he had written and its content and how it was going to revolutionize the world and so forth. I could tell that he was talking about this little-known discourse of Joseph Smith on adultery and fornication. This letter was written in 1839, which was long before this little-known discourse of Joseph Smith was supposed to have been written. I realized that I would be able to demonstrate based on this letter that Joseph Smith was not the author of the other document. When I came back, I shared this information with Richard Anderson, who was working with BYU Studies, and he published my article in BYU Studies. In fact, when people write in about this little-known discourse, they give them a copy of my article. So that was an exciting document to discover.

M. Godfrey: From 1975 to 1978, you were the mission president of the Pennsylvania Pittsburgh Mission. Was there anything that happened during those three years that influenced either your career as a Mormon historian or your career as a teacher in the Church Educational System?

K. Godfrey: Those were the years that saw the appearance of The Story of the Latter-day Saints, which was, I believe, the first book that represented what some have called the New Mormon History—a new, more open Mormon history. I learned that that book at first had not received unanimous praise at all levels of the Church. That fact causes one to wonder just what kinds of history an employee of the Church Educational System could write and stay out of trouble.

I also had an experience there with a great-granddaughter of Sidney Rigdon, who, it was thought by one mission president whose place I had taken, might have the 116 pages of the lost manuscript of the Book of Lehi. So I had an experience with her and later realized that when I was talking with her, I was within just a few feet of two first editions of the Book of Commandments. I wish I had known at the time so I could have just held them because they, as you know, now sell for thousands and thousands of dollars. Pittsburgh was also the area where Solomon Spaulding died, and we lived in the same part of the greater Pittsburgh area where Sidney Rigdon had lived.

While I was still mission president, I received a call from a man one day who said he had a first edition of the Book of Mormon and wondered how much it was worth. I told him it depended on its condition and where it came from. He asked that I come to his home and he would show me the copy. I did so, and in the front of the book I read the words, “Martin Harris the Mormonite. Martin Harris.” The book was in very good condition, but I said if this was Martin Harris’s copy and if that is his signature, then it would be worth more. He said, “Is it Martin’s handwriting?” I replied, “I do not know, but I can find out.” We made a copy of the page on which the writing appeared, and I sent it to Richard L. Anderson and asked him if it was Martin’s handwriting. A few days passed, and he wrote back and said he had shown Dean Jessee the writing, but there was so little in Martin’s own hand that they did not know whether it was or wasn’t his signature. I told the man we were not sure, and he decided to keep the book in his bank safety deposit box. Later, at a Mormon History Association meeting, I saw a copy of the paper I had sent to Provo used as an example of Martin Harris’s handwriting. I also told this story to Mark Hoffman, and he tried to see this copy of the Book of Mormon, but he was unsuccessful.

Also, a number of Mormon missionaries had served in that region in the early days of the Church, and I talked quite often about history to my missionaries and also continued to read a lot while I was there. In that sense, I kept up on what was happening in Mormon history and tried to stay on the cutting edge.

M. Godfrey: I take it, then, that the great-granddaughter of Sidney Rigdon did not have the 116 pages?

K. Godfrey: No, and that would have been devastating to the Church had she had that lost manuscript, because that would have given critics an opportunity to say that Sidney Rigdon was behind the Book of Mormon, which is something they have tried to prove for a hundred years. But she did have a number of Sidney Rigdon’s items, and I was able to follow through with a man who became a good friend of hers. She donated some of those things to him, and they are now housed in the Special Collections and Archives at Utah State.

M. Godfrey: Then, after your term as mission president, what did you do?

K. Godfrey: Well, when I got ready to be released, I was offered a job in the College of Religion at Brigham Young University by Larry Porter, who was the chair of the Church History and Doctrine Department. At the same time, I was offered a division coordinator job over all of the Church’s seminaries and institutes from north of Salt Lake into southern Idaho and Wyoming. Joe Christensen was the person who invited me to accept that position. After considerable thought and some prayer, we decided to take Joe’s offer. After I was released, we moved to Logan, and I had an office at the Institute of Religion at Utah State University.

M. Godfrey: Please talk a little bit about some of your significant accomplishments in Mormon history during the 1980s.

K. Godfrey: In the 1980s, after I’d returned to Utah State University, I served on the board of the Mormon History Association again. I began to resume my studies. Doug Alder, who was a history professor at Utah State and head of the honors program, representing the Utah Council for the Humanities, asked me if I would give a lecture on the Moses Thatcher case. I’d given some “Know Your Religion” talks on the coming of the two-party system in Utah, and he knew I’d done something with Moses Thatcher. He said, “You’ll give this lecture at several locations and then we’ll invite Tom Alexander and Leo Lyman (who had published a book on the coming of the two-party system to Utah) to comment on your talk.” I took six to eight months researching the topic, and I presented the paper. It was called, “There Was More to the Moses Thatcher Case Than Politics.” I delivered it in Ogden and Logan and maybe one other place—I can’t remember right now—and there were comments on it. So that got me started again on some original research. By then, Women’s Voices was published—that was in 1982. Then I was asked to serve as president of the Mormon History Association, and I spent a lot of work on my presidential address, which was on writing a different kind of history of Nauvoo that emphasized what the common people were doing and not just on seeing the history of Nauvoo through the eyes of Joseph Smith and other Church leaders.

M. Godfrey: How did your appointment as president of the Mormon History Association come about?

K. Godfrey: Doug Alder was a member of the nominating committee, and he just called me one day and asked me if I would be willing to serve as the president. By this time, the Mormon History Association was not seen in an altogether favorable light by everyone who held authority in the highest levels of the Church, so I said to him, “Doug, I don’t think I can tell you yes or no unless I check with the commissioner of Church Education. I’ll have to check with Brother Eyring and see how the Church Educational System feels about this because it’s a fairly visible position to hold.” So I called Brother Eyring and visited with him about it, and he told me to go ahead and do it. He thought it would be a good thing. So I responded to Doug and told him I’d be happy to serve. That’s how it came about.

M. Godfrey: What do you think was your most significant accomplishment as president of the Mormon History Association?

K. Godfrey: I suspect it was delivering the presidential address and the work that went into that. The address was published in the Journal of Mormon History and then was republished in a book that was supposedly a compilation of some of the best articles that had been written about Nauvoo. Another accomplishment, I guess, was being calm in the face of some storms. Just before we held our annual meeting in 1984 on the campus of Brigham Young University, rumors started to circulate that the program committee—which involved me because the president serves on that committee—was not willing to have papers presented by members of the RLDS Church. So I got a letter from Sterling McMurrin protesting such a narrow-minded attitude. In actuality, when we had sent out our call for papers, apparently Provo was far enough away from where most members of the RLDS Church were living that none had responded. So we had to do some calling and make a special effort to include them. We got that little fire out. Then, when it came to considering some of the awards, one that some thought should receive the best article award, other members of the council believed the author plagiarized the work of one council member. So we had to put that fire out. Then, in the conference itself, some of the papers attacked the Book of Mormon and its historicity. There was a lot of publicity about these sessions. It was quite an eventful year in lots of ways. I was glad we were able to successfully steer the Mormon History Association through some of those challenges that year.

M. Godfrey: How much of that controversy over the program of the conference, do you think, had to do with the fact that you were someone in the Church Educational System serving as president?

K. Godfrey: I think there were some that wondered if an employee of the Church Educational System could be inclusive of others. Also, the fact that it was held on the campus of BYU gave some cause for concern. In fact, Don Cannon was the program chair that year. He and I had both talked about this very issue and the fact that we thought we had to be a little careful and have some respect for the campus of BYU and what Brigham Young University represented. Maybe it would not be appropriate in that setting to give approval for Walter Martin or some other known anti-Mormon to present a paper at Brigham Young University—not only Walter Martin, but, say, someone like Wesley P. Walters, who was known as a vigorous opponent of the Church. There were people who thought that whoever wanted to present a paper should be allowed to do so no matter where we were holding it. But over the years that hasn’t always been the case. The program committee has always tried to look at the quality of the proposals they were receiving, and there have been a variety of reasons for not giving approval for someone to present a paper on this or that.

M. Godfrey: What are some of your articles or publications that you consider to be the most significant for Mormon history and why?

K. Godfrey: One that had a fairly good impact was a paper I delivered in Nauvoo at the home of Lucy Mack Smith called “Some Thoughts Regarding an Unwritten History of Nauvoo,” which was a call for some social histories of Nauvoo to be written. A few years ago, while I was delivering another paper in Nauvoo at the John Whitmer Association meetings, Richard P. Howard, the retired historian of the Community of Christ, who introduced me, said in his introduction that “Some Thoughts” was a talk that had influenced him and one that he thought had influenced a lot of other historians to look at the history of Nauvoo through different eyes. After I had given this talk, it was published in BYU Studies under the title that I just mentioned. That was one that was fairly significant, I think. I also feel good about an article I did on Frank Cannon and his political and anti-Mormon career, which appeared in a book published by the University of Illinois. That was a good article.

M. Godfrey: What was significant about that in your eyes?

K. Godfrey: Well, I don’t think anybody up to that point had ever dealt especially with the career of Frank Cannon after he left the Church, the background of his anti-Mormon book Under the Prophet in Utah, and some of the reasons, perhaps, for his leaving the Church and becoming the editor of the Salt Lake Tribune—some of those aspects of his life. I don’t think anybody had talked about his alcoholism and his immoral activities in houses of prostitution. In fact, I was accused by one historian of making some of that up. But I was able to share with her accounts from his own brother’s diary. His brother was an Apostle and was writing at the time, and so it seemed to me that it was the kind of evidence that you’d have to believe. The number of times it occurred seemed significant, it seems to me, in terms of understanding the man and his weaknesses.

M. Godfrey: As far as rounding out your career in the Church Educational System, maybe you could talk for a second about what you did after you came to Logan and how you became director of the institute at Utah State.

K. Godfrey: After twelve years as the area director of the Utah North Area, there were some of us in the Church Educational System who had been in administrative positions for long periods of time—if you put all of my area directoring together, I’d been one for close to twenty-five years. It was thought appropriate that perhaps those jobs be rotated and new people be given the chance. I told them I’d be happy to do anything they wanted me to do. I was expecting to go back in the classroom full-time, but much to my surprise, they asked me to be the director of the Logan Institute, which meant that I’d only get to teach half-time. So I spent the last five years of my career in the Church Educational System doing that.

M. Godfrey: Then you retired in 1995?

K. Godfrey: Yes.

M. Godfrey: What do you think has been your most significant accomplishment as a teacher of Church history?

K. Godfrey: As I get older, the better I get as a teacher because I’m getting further and further away from it. I think I was fairly competent in the classroom. I also think that when I taught Church history I tried to deal with most of the issues that are embedded in the study of the history of the Church. Then, I’ve had some degree of success in a course I taught outside of the normal curriculum, which was called “Answers to Difficult Issues in Mormon History.” That title may not have been the best title; maybe I should have called it “Responses to Difficult Issues in Mormon History” because it’s a little presumptuous to assume you have the answers. I would allow the class to determine what we were going to talk about each semester by turning in sheets of paper with questions that they were dealing with in terms of Mormon history. I’ve had more than the usual amount of testimonials that that class was helpful and kept people tied to the faith, so there’s some comfort in having been willing to deal in an academic setting with issues like the Adam–God theory, blood atonement, plural marriage, politics, and even apostate Mormons. I guess I would take some encouragement from that class and from some of the things the students said about it.

M. Godfrey: Do you think that a difference exists between Mormon history as it is taught in the Church Educational System and Mormon history that you’d hear at a conference of the Mormon History Association?

K. Godfrey: I think there have been some historians who have mainly taught (in the university setting) subjects other than Mormon history, who have sometimes believed that they were more competent in the field of Mormon history than were some seminary and institute people. It was a little bit surprising to me that, when a very controversial presidential address was given in the early 1970s, the bulk of those who were most concerned about what they were hearing were these kinds of teachers—those who were teaching in various universities across the land. There was one full busload of seminary and institute teachers who was not very concerned at all, because they had already learned much of what the speaker was talking about in their in-service training. In that sense, I think that some institute teachers especially were able to treat issues in a more sophisticated way than some of these more famous historians because they knew more of the material and had been in the primary sources more than had some of these other teachers. So in that sense, you might get a better grasp of Mormon history in the institute than you would from a professor who was teaching it at a secular university.

Now, after having said that, if you teach in the Church Educational System there is also a certain amount of loyalty that you owe to the Church—your employer. In that sense, you were charged, when you signed your contract, with teaching those things which you perceive will grow faith in your students. The problem comes because you are not always sure what will grow faith and what will not. For some people, faith improves if they believe that they’re getting everything in the history of the Church, while some don’t believe they’re able to handle all of that. It’s an ongoing challenge, but I don’t see that teaching a course of Church history in the institute is significantly different than the way it is taught at a university if the teacher is well acquainted with Latter-day Saint history. If all they’re acquainted with is anti-Mormon sources, then it would be really different, but if they’re actually down into the primary sources and base their lessons on those kinds of documents, then I think there shouldn’t be a significant difference.

M. Godfrey: Could you talk just for a minute about some of the historical works that you have produced for a more general Church audience rather than for an academic audience, and about some of the different approaches you use in writing for a more general audience?

K. Godfrey: If you write for a general audience, you have to be a little more concerned about context and how what you’re writing relates to the broader world. You also have to be a little more concerned about the language you use and not use terms that would have no meaning for a general audience because the terms are so peculiarly Mormon. In that sense, you should be a little more careful and make sure that the general reader without a Latter-day Saint background will be able to understand what you’ve written and perhaps its significance. The bulk of my writing has not been for general audiences. I’ve had one article published in the John Whitmer Historical Association Journal regarding non-Mormon accounts of the martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, but that was written about the same way as other articles were except I relied on non-Mormon sources, thinking that ought to be clear to outsiders without a whole lot of explanation as to what they were talking about.

M. Godfrey: What about writing for a general Church audience rather than for the academic community, such as articles in the Ensign or in curriculum manuals?

K. Godfrey: I think for a general Church audience, when your byline is that you’re a CES employee or the director of an institute, then somewhere in those articles, your own faith in the Church and in its leaders should be apparent to the reader. The articles should be written in a context of faith, especially those that appear in the Ensign. If you don’t do that, they won’t appear in the Ensign.

M. Godfrey: What do you think about the state of Mormon history today and the state of the Mormon History Association?

K. Godfrey: I’m consistently amazed and impressed with the amount of research and writing that is going on. When I first came into the Church Educational System, I could read everything that was written about the Mormons, including their history, and stay on top of everything with only a minimum amount of effort. Now, it’s difficult to stay abreast of just what is written about Nauvoo or what is written about Missouri. The quality of the articles overall, I think, has improved over the years. It’s just quite thrilling to see all of the things that people are finding to write about. Now, there are some who will criticize and say we’ve written about everything that’s important and now we’re only writing about things that aren’t important, but I don’t think that’s really the case. In that sense, it’s very healthy. The last few years there have been more things to be encouraged about. This project of publishing all of Joseph Smith’s papers and his writings—you would never have thought such a project would have happened thirty years ago. That should be a great boon for historians, and the fact that Church leaders are willing to publish everything about Joseph Smith in the Church Archives should also be an indication of the faith the leaders have in him. I think there is reason to be very optimistic. I think the Mormon History Association itself has turned a little bit of a corner in the last five or six years in that there have been more young historians willing to participate in and do research in the field of Mormon studies. We used to call it the graying of the Mormon History Association, and some wondered if it would be able to endure. But now there is a plethora of young scholars like yourself who are doing some things in Mormon history—and some of them exclusively. They’re very good and very thoughtful and are producing outstanding books and articles.

M. Godfrey: Where would you like to see Mormon history go from here? What themes do you think still need to be addressed?

K. Godfrey: This isn’t very original, but there is a great need for the emergence of Mormon history that is based on the experiences of “average” Latter-day Saints in South America, Central America, Mexico, Japan, Korea, Europe. We’ve had some histories written of these countries, but it’s usually been through the eyes of the missionaries who carried the gospel to those countries. I think now we’ve got to have some historians working with documents and with the Latter-day Saints in those countries to explicate their experiences with the Church.

M. Godfrey: Finally, just as kind of a retrospective—when scholars in twenty years or fifty years look back at the career of Kenneth Godfrey as a Mormon historian, what do you hope they will say about your career?