Charles S. Peterson

John A. Peterson and Charles S. Peterson

Charles S. Peterson and John A. Peterson, “Charles S. Peterson,” in Conversations with Mormon Historians (Provo: Brigham Young University, Religious Studies Center, 2015), 449–92.

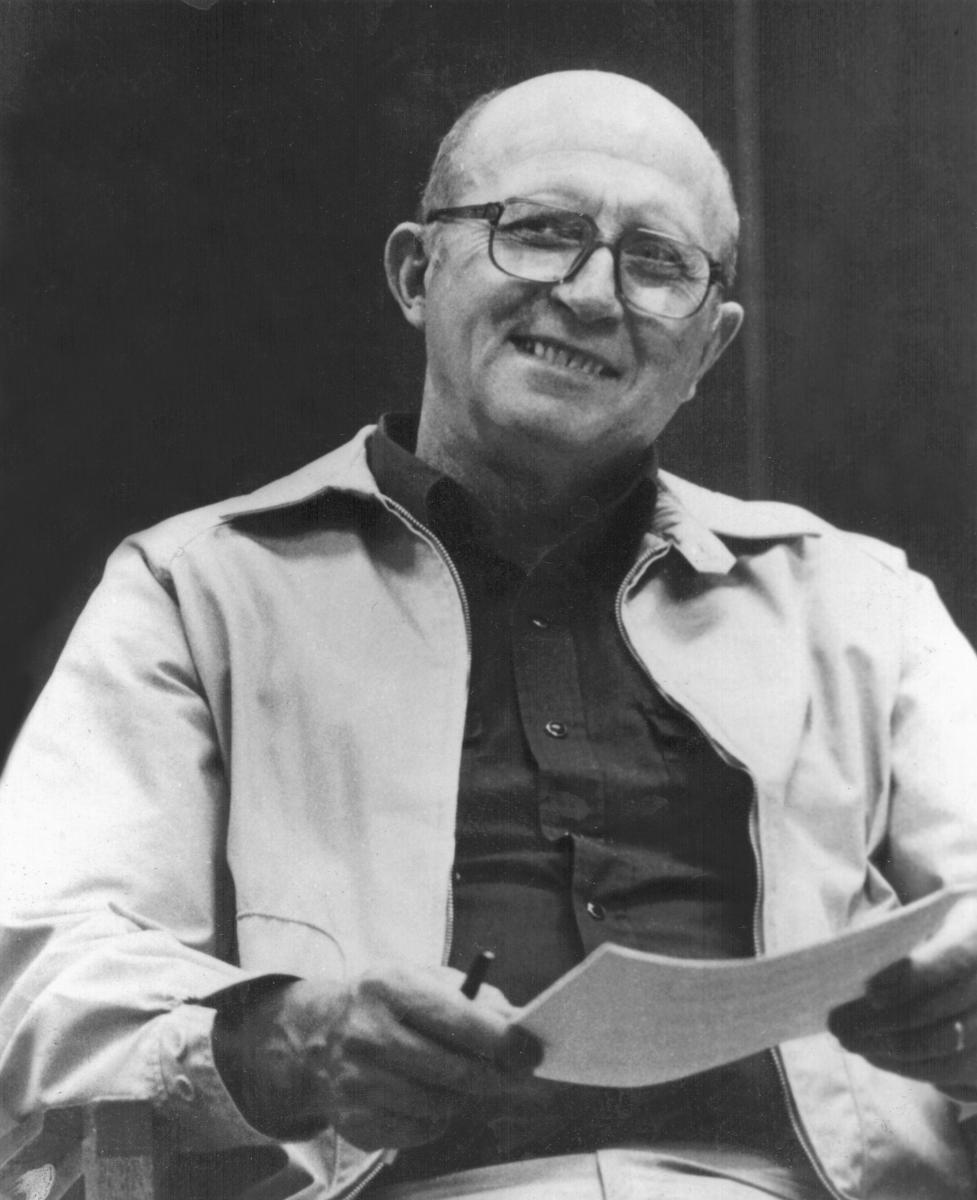

Charles S. Peterson, affectionately known as “Chas,” was professor emeritus of history at Utah State University when this written. He earned BA and MA degrees from Brigham Young University and a PhD from the University of Utah. He is a historian of the American West with areas of special interest in Mormon and Resource Management Studies. He taught at four Utah universities and colleges. He was director of the Utah Historical Society and the Man and His Bread Museum, as well as editor of the Utah Historical Quarterly, the Western Historical Quarterly, and a University of Utah Press series on Utah history. He was the recipient of grants and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association for State and Local History, and the Huntington Library.

John A. Peterson, a son of Charles Peterson, received a BA in history from Utah State University, an MA in history from Brigham Young University, and a PhD in American history from Arizona State University. He has taught in the Church Educational System for thirty-two years, including twenty years at the Institute adjacent to the University of Utah. He also worked for several years in the Church Historical Department and is the author of the award-winning book Utah’s Blackhawk War.

The Interview

J. Peterson: Let’s start with your youth in Snowflake, Arizona—your family background and your parents. Focus on how your parents and related factors might have influenced you to become a western historian and on how being Mormon featured as well.

C. Peterson: I was born into an established Latter-day Saint family. Both my father, Joseph Peterson, and my mother, Lydia Savage Peterson, had previous marriages. Between them, they had eight children when they were married in 1924. Father had four boys and two girls. Mother had two daughters. I was the second child born to them, and three sons followed, making a total of thirteen. So counting his, hers, and theirs, it was a big family.

Teaching was a factor in both families. My dad taught during much of his life, my mother was a teacher during parts of hers, and her parents had both taught at one time or another. So education came rather easily to mind as an occupational outlet for the entire clan.

I was born in 1927 at an outlying Mormon community—Snowflake, Arizona—which at the time consisted of about a thousand people. Ninety-five percent of us were Latter-day Saints. A group of Mormon towns was situated around Snowflake, making possibly thirty-five hundred or four thousand Mormons in Navajo County. The upper part of the county coincided very closely to the Snowflake Stake.

Dad taught at what had become Snowflake Union High School after 1924. He was still a revered figure. He had a lot of hair—unlike some of his descendants. It was absolutely white. He had great dignity, and even though the school was just a high school, he was always called “Professor Peterson.” He had left the Church academy to get into politics, serving first in the territorial legislature and becoming county school superintendent and county supervisor during the first decades of statehood, before returning to the classroom. He was well known both among the Gentiles and the Latter-day Saint community of the county. In the most literal sense, he was one of the builders of the county and also one of the founders of Lakeside, all of which had a lot to do with how I regarded myself.

Giving my early life a particularly Mormon quality was my grandfather Levi Mathers Savage, who had pioneered in northern Arizona for forty years before returning to Salt Lake City in 1922. Much later, I learned that “Bishop Savage yarns” had delighted boys of the Forest Dale Ward of the Salt Lake Stake—maybe it was the Granite Stake by that time. One of those boys, Wayland Hand, a renowned folklorist, remembered him as a colorful figure there in the Forestdale Ward about Twenty-First South and Eighth East. Levi Mathers [L. M.] was a fifth-generation pioneer. John Savage, the family’s first American, had been with Wolf at the Plains of Abraham in the French and Indian War. Later, he and his son Daniel pioneered progressively West from Massachusetts to Ohio. L. M.’s grandfather Levi Sr. had been involved in the Mormon drivings, including the exodus. His father, Levi Jr., had marched with the Mormon Battalion, had circumnavigated the globe as a missionary, and had voted against heading to the West with the Willie Handcart Company. One of the last of the frontier breed, L. M. had himself pioneered at Cottonwood, Camp Floyd, Scipio, and Kanab Creek before he paused long enough to learn to read when he was thirteen. When I was seven, I sat enthralled as he told of early Utah, including running from Indians and retreating to the relative safety of Toquerville during the Black Hawk War.

So pioneer times were not very far away in my life. I thought of them often, and I quickly acquired a taste for Zane Gray novels and Western movies. I began to think of myself as “Western” at a very early age and represented myself as something of a redneck in the military, on my mission to Sweden, and during my first sojourn at Brigham Young University. Dad had a bookcase with glass covers over it—the kind that lawyers use—in which he had quite a number of Western books, and I began reading them early. The Log of a Cowboy by Andy Adams was one. Another was Earl Forrest’s great account of nearby range wars, Arizona’s Dark and Bloody Ground. My fourth-grade teacher made a big deal about history but was always sore at me for sneaking that book into my desk and lifting the lid a little and trying to read it during math. Knowing about Stott, Scott, and Wilson—rustlers hanged by vigilantes—and about sheriff Commodore Perry Owens’s shootout with the Blevins brothers in neighboring Holbrook filled me with pride instead of awakening any sense of the country’s backwardness or fears of damnation and hellfire.

I was a product of the Wild West and thought myself to possess sterling qualities because of it. Particularly, I was a cut above the city slicks of California, even if they were farther west. Yet, unlike my brother Roald, I was no rodeo jock. I wore clodhopper shoes and shapeless “Monkey Ward” denim shirts, and although I had a horse and rode it often, I saw myself as a farmer and cherished the conviction that tillers of the soil were not merely the backbone of country life but of the nation as well. Such notions and feelings began to put place, people, and perception together with values and self-image in my mind. I still harbor these feelings and treasure the sense that Mormon Country is the real West, a place that somehow gives me a unique identity.

I was both bored with Snowflake and in love with it profoundly. I loved the agricultural facets of it. I loved making our own way, milking our own cows, raising our own beef, and killing our own hogs. My mother made cottage cheese and in the summer, when milk was in surplus, made two or three cheeses a week. She also canned everything you can imagine. “Mormon self-sufficiency” came pretty close to being a reality. Dad’s schoolteacher salary during the Depression was stretched between two families who were struggling to get started—young married adults who had new children and needed loans and help with their schooling and then four little sons of his own to raise. It was recognizably like Mormon pioneering, even in the 1930s.

Yet I worked the country western aspect of life into this bored but loving relationship. Highway 66, over which “dust bowlers” poured, was less than thirty miles’ distance. Okies stopped in the vacant lot that butted on our place, grabbing a day’s rest and overhauling their jitneys, as engine parts rusting in the dust attested for decades. The “Tri-weekly,” or Apache Railway, ran through town three times a week bringing lumber goods and Apache-raised Herefords out of the White Mountains and importing Arkie and black lumberjacks and mill hands. Section gangs, sheep herds, and settlements dating well before the Mormon advent brought Mexicans. Teenage dudes from New York’s Jewish communities returned summer after summer. Life made Mormon kids in the “upcountry towns” a little tougher, and the mix of cowboy, lumberjack, sheepherder, backslid Mormon, pretty girls, rainy season, and holiday-reverie tinctured tedium with cultural tension and toughness—if indeed not with vice and sin to endear the years of my youth—as talking about them does now.

J. Peterson: Is it fair to say, then, that you grew up with a sense of a broader heritage in this little Mormon community of pioneers?

C. Peterson: No question it had an impact, and in flashbacks, as in the present situation, it still does. I liked the give and take of history. I knew that at an early date. I loved old-timers’ stories. One of the greatest storytellers of my town was Lewis Decker, whose father, Zachariah B. Decker Jr., had faced down the cowboy faction in the cattle-sheep wars and could still be seen on an early spring afternoon sitting rheumy-eyed and palsied in the sun south of the town’s last log cabin.

More important was the example my folks set. Both were engaged fully in the town’s Church and civic life. Father was in the stake presidency and, as the only driver, often waited upon visiting General Authorities, who sometimes also slept and ate at our modest home. He was also a regular speaker on the funeral circuit, carrying with him notes for ten or fifteen sermons that he shook out on need, the last occasion being services for Aunt Em Smith, President Jesse N. Smith’s last surviving wife, hours before he himself went to bed never to rise from cancer. Mother was on the Relief Society stake board and later was president. She sat on the school board of trustees, and both she and Father were on the board of the maternity hospital that began to emerge through arrangements with the General Relief Society Board in the middle 1930s. Late in life, when genealogy became a transcending interest, she was called to be the founding director of the Snowflake Stake’s Family History Library. Because her patriarchal blessing foretold that she would “teach the daughters of the Lamanites,” she sought opportunity to fill a two-year mission focusing on weekend visits to Navajo and Hopi women.

Among Father’s most taxing responsibilities was the stake presidency’s support of the Lone Pine Water Storage Project, which involved an iffy undertaking that, in spite of Apostle John A. Widtsoe’s blessings, sharply divided the membership of the stake. Not only did the stake presidency lend full-hearted ecclesiastical backing, but Father was also cosigner for the winning contracting company’s financial obligations, much to Mother’s distress.

J. Peterson: Your father died when you were sixteen?

C. Peterson: Yes, after a period in which he had trained me intensively in farming procedures, he died of cancer. My mother was still a vigorous woman—fifty-one years old. She was a very capable person, in many ways the key individual around whom the growing clan revolved. Our economy took a turn for the better immediately when she took over the breadwinning. I don’t credit it entirely to her, though some credit ought to be hers. Dad always thought he was going to be rich, but he never did stop to think about how he was going to get rich and what you ought to do if you had money. But Mother was a managing sort of person. World War II had started on December 7, 1941, and by the time of Dad’s death in June 1943, the war’s economic repercussions began to reach Snowflake. With teachers leaving for high-paying war jobs, school trustees beat a path to Mother’s door, urging her to teach at the grade school only a block away so she could duck home during recess to look after her invalid mother. Kids who hadn’t been able to find a job anywhere during the generations just past could hardly beat a job off with a stick during my years. Yet I stayed with the farm. The other boys (my younger brothers) began to work out as quickly as they could, but in due time I got drafted, and they each took a turn running the farm that Dad had saddled Mom with—the poorest farm in the country. It was at Belly Button—a little valley located midway between the two Mormon towns of Snowflake and Taylor.

J. Peterson: What about World War II and being drafted? Can you give us just a word or two about that experience and about your mission?

C. Peterson: Well, like most guys, I went to join a time or two, but I chickened out each time as I thought of Mother’s needs. So I left it in God’s hands and waited to be drafted. I didn’t go into the service until April 1945. In about three weeks, the war in Europe ended; and just before I got overseas, the atomic bombs had been dropped and Japan capitulated. After waiting around on the ocean awhile, the troop transport I was on docked in Yokohama Harbor on a sunny October afternoon. Although I didn’t realize it then, the six-by-six trucks that unloaded us and the tattered dock facilities stretching off toward Tokyo symbolized global conquest at its all-time high. Japan and Germany were prostrate. Europe and Russia were exhausted, and, for the moment, the US alone had the bomb. I spent thirteen months in Japan and came back with a full ride of the GI Bill that covered four and a half years of college. Mail call aboard the General Black as we prepared to leave carried a letter from my mother. In it was wise counsel. I was returning. I would want to go on a mission, go to school, and get married, probably in that sequence.

My initial impulse was, “Baloney, Mom! How little you know me or understand the costs my generation has paid.” For the moment, I was obsessed with the idea that I was a Depression baby and a World War II adolescent. I had never really had the fun of being young under normal circumstances in good times. Now was the time for me to catch up on life. But as I arrived home and as my mood swung from euphoria to soberness, my thoughts changed. Particularly, I watched my peers, some of whom constituted what we called the “52-20 club”—guys who for fifty-two weeks opted to draw twenty dollars a week in severance pay as part of the military separation program rather than go to school or work. As I watched them sit lined along the south side of the old Turley Garage each Tuesday morning to draw their twenty dollars, I got fed up with the idea that I was entitled to idleness. I told my mother—threatening her that if she whispered it to the bishop, I’d find out and give her no end of trouble—that if I got called on a mission right then, I would take it as the Lord’s will and go.

Sure enough—the next Sunday was stake conference. That morning, the bishop, dressed in his best, came stepping primly among frost-crusted cow droppings to where I was doing the milking. Elder S. Dilworth Young was in town. He wanted to see me. That evening in the Boy Scout room of the Old Main Street Chapel, he interviewed me for a mission. So there I was, stuck.

J. Peterson: What role did your mother have in that?

C. Peterson: She maintained until her dying day that she didn’t breathe a word. I’m convinced she didn’t. Although Mother always did the long-range planning that got her sons into college and off to a good start in life, why should she in this case? She was getting exactly what she and the Lord wanted.

J. Peterson: Where did you serve?

C. Peterson: I went to Sweden. Father maintained a strong sense of his Scandinavian heritage, and he endowed me with it as well. In the first days after receiving my call, I thought of myself as making a surrogate trip to the homeland. I wanted to get back to Ystad, the southernmost city in Sweden, where Father’s parents had joined the Church. (Grandma came from a little farther north in Sweden than Grandpa.) Both Grandfather Peterson and his father had been stoned as Mormon elders before fleeing to Denmark to be missionaries across the neck of the Baltic Sea. In the wake of Elder Young’s interview, I was eager to go, and I was thrilled when the call came. But as the weeks passed, I was worried somewhat about it. I was breaking horses that winter, and I found myself praying that one of those broncos would stack me up somewhere and break some of my bones so I could take the outcome as evidence that the Lord didn’t really think I would make much of a missionary and that I could minimize the loss of face I would incur by backing out of my mission. But it didn’t happen. The horses gentled right down, and off I went.

J. Peterson: How did your mission go?

C. Peterson: About par for the course. It was exciting to be on the road again; it had been nearly fifteen years since I had been in Salt Lake City. With Douglas McArthur’s show of pomp, I had something to compare to the morning arrival of the General Authorities and downtown businessmen in their big cars. The disparity between our country circumstances and theirs was not altogether lost on me. The trip over on the Gripsholm was fantastic. The ship was filled with emigrants visiting home for the first time in years. The seas were rough. As an ex-infantryman, I fell in with a former Marine named Ralph Berquist from Mink Creek, Idaho. Like myself, he had spent months on troop ships and now shared in my pleasure when those members of our missionary group who had been naval officer candidates got seasick. To some degree, that spirit of dissent stayed with me for perhaps six months before a growing testimony stirred in me as I studied the Doctrine and Covenants Commentary by Hyrum M. Smith and Janne Sjodahl and met with Elders Ezra T. Benson and Alma Sonne, who were buying and renovating buildings throughout northern Sweden to make into LDS chapels. I worked for a year and a half in Norrland, part of it above the Arctic Circle. I felt closest to a temperance group in Lulea, consisting of young people, several of whom were interested in the gospel. Later, I worked at Karlstad in central Sweden and at Ystad, the home area of my father’s people. Although we had been cautioned not to promote the gathering, two families of members came to Utah with my aid. In both cases, Zion was not the answer to their needs. Yet the magic of Scandinavia’s seasons and character touched me deeply as I understood the gospel better. For the first time, a maritime spirit moved me as I came to know the Baltic region and a bit about its history. The magic of the Spirit that brought so many Scandinavians into the Church and to Utah lingers as a sweet testimony in my life.

J. Peterson: What year did you get off your mission?

C. Peterson: 1949.

J. Peterson: Then what?

C. Peterson: I started out farming the old place again, which I assumed after a year or two of college would be my life’s work. But it was a short-lived dream. Where Silver Creek ran through our Belly Button farm, there were two diversion dams within a few hundred yards of each other, one taking water out for the East Snowflake Ditch and the other for the West Snowflake Ditch. As silt came in over the years, the irrigation people kept raising those diversion dams to push water out. All of that backed the water up in flood times onto our farm. The summer I got home I planted cucumbers, hoping to make enough cash on the crop to get me into BYU, together with my GI Bill (meaning I wanted to buy a car). One of those floods came and wiped all of that out just as the second or third picking of cucumbers was harvested. I hadn’t even paid off my expenses yet. So I quit the next day, giving up forever, as it turned out, on that farm. Making my first compromise with the industrial world, I went to Southwest Lumber Company’s drying kiln and stacked lumber for six weeks, where I saved six hundred dollars. I went to Mesa and bought a 1939 Oldsmobile two-door sedan, and there I was, equipped with a fine automobile and a dull mind, ready for school.

J. Peterson: Tell us about your college education. Were there any “awakenings” in historical sense there? Didn’t you study animal husbandry?

C. Peterson: Well, in 1949, I took a history class from a very remarkable young man, Richard D. Poll, who had finished everything for his doctorate except his dissertation. He would be well known to readers in Mormon and western American history. At that early point of his career, Poll had what struck me as a wonderful philosophy. You didn’t need to come to class any day except Thursday, and then you could leave right after you took the exams. And if you’d take the exams and be satisfied with a C, you could whistle right along and be happy, and that’s what I did. There were two history professors who did catch my attention at that time, Poll being one and the other being Brigham D. Madsen. It was really by their reputation as dynamite teachers that I was first attracted to history and also because I rather quickly decided that I would take classes that came easily for me. I never actually took a class from Brigham Madsen, but he later came to play an important role in my life.

Still anxious to measure up as a son, I thought to major in English, which my father had taught toward the end of his career. Adding to the luster of his reputation locally and in my admiring eyes, he had staged annual pageants in a sinkhole west of Snowflake. Written, produced, and acted out by graduating classes on Arizona and classical themes, these pageants brought hundreds of spectators over nearly impassible wagon-track roads. Making English my major involved commitments to the Veterans Administration. It took only one quarter to change my mind. Taking another bout of questions that showed me to be the most ardent farmer ever, I shifted to agriculture, an almost invisible field of study at the Y. During the next three years, I did what I could to give it visibility. To my satisfaction, classes seemed much easier; and in this secluded part of academic life, I was well thought of by my “an-hus” colleagues and was happy in a course of study that to me seemed to protest gently against the urban smartness of the white-collar grain, then beginning to dominate the Y.

J. Peterson: So you graduated in . . .

C. Peterson: In animal husbandry on June 4, 1952. I used Swedish to beef up my credits and went one summer and got a BA degree in three years. Early in 1953, I leased a dairy farm at La Sal between Moab and Monticello from southern Utah ranch baron Charlie Redd—a hard-nosed man who, if you made it, sometimes helped young men get a start in livestock business. But he and I didn’t make it, and after about four years, I jumped my contract. It was for five years, and with legal advice from a former congressman, who with the uranium boom was practicing law in Monticello, I was able to detach myself from Charlie Redd in the fall of 1956. I still loved farming. I loved the land, and “vo-ag” principles like the sanctity of the family farm were strong in my blood. Consequently, as I left the ranch, it seemed best to go back and get a degree in some phase of agriculture and become a teacher, probably a “vo-ag” teacher in a high school. That was really my first idea. So I took a couple of education classes that first fall, and they bored me stiff. I thought they were a waste of time, and I was delighted with the history classes I took. I didn’t have as dynamic a teacher as Richard Poll by any means, but something much more important happened.

At Redd Ranches, I had belonged to a little Church branch with about fifty members, of whom maybe twenty-five attended. Charlie had the capacity to gather first-rate people around him, and this was not a slouchy bunch of crackers off in some hillbilly backwoods. They were people with advanced degrees and a lot of education, and they responded very well to the best kind of teaching. I don’t know that they got it from me, but I ended up being in the branch presidency and doing anything else there was to do, including teaching the Gospel Doctrine class. The last year we were there, the Sunday School course of study was on the life and epistles of Paul. The primary author of that book was Russell Swenson, and I had a support book by Sydney Sperry. I also had a book from my college years on the life and mission of Paul that gave me a further resource. I had such fun teaching that year that I thought I would like to take a class from this man, Russell Swenson, who had written the lesson book and who was teaching at BYU. It turned out that he was one of three Church Education System men whom BYU president Franklin S. Harris had sent to Divinity School at the University of Chicago, on the assumption that maybe CES ought to train its professors in schools of divinity throughout the country. These were Russell Swenson from Pleasant Grove, Utah; George Tanner from Joseph City, Arizona, who had studied under my father at the Snowflake Academy; and Daryl Chase, who was president of Utah State University just before I joined the USU faculty in 1971. Interestingly, each of these men played important roles in my life.

Swenson was teaching world civilization, and I signed up for the classical period. I didn’t know that he had experienced some kind of serious hormonal imbalance with one of the glands in his throat, and after an operation he ended up with tunnel vision. I sat right up on the front row to his right, but he’d never call on me. He couldn’t see me—never did see me waving my hand over to his right. But I finally began to notice the pattern of where he called on the students, and I sat over in that “channel,” attracted his attention, and became one of the prominent students of the class. At the end of the quarter, I had my first A in history. I also had him asking me if I didn’t want to take a graduate course he was offering on the history of the medieval mind, which had been one of his areas of specialty at Chicago. So I signed up and survived the course in pretty good shape.

Meantime, an event of the utmost importance had taken place in my life. I had fallen in with a young lady of fine achievements at the Y; Betty Hayes was her name. Her grandfather John E. Hayes was the registrar at Brigham Young University from 1900 until 1951. She had been born in the East herself, where her folks had gone to college in the early years of the Depression, and they had never gotten back. Her dad had an MBA from New York University and had spent much of his life at Wilmington, Delaware, working for Dupont, but Betty was thrilled with the Y, and I was thrilled with her. Finally, I talked her into marrying me and into going down to Charlie Redd’s ranch. We had two children by the time we came back in 1956 to take up my education and enter a stream that drew me into western American history.

J. Peterson: Was this Swenson class part of your master’s program?

C. Peterson: Initially, I didn’t know I was starting on a master’s program in history. I was really compromising myself away from the farm. It was a long and, in some ways, agonizing process, and the focus I’ve had on rural Mormondom has been closely related to that bond. I’ve made all my kids go from dam to dam throughout the West and study their dynamics, as well as go to the Mountain Meadows Massacre site—no choice of theirs, just sheer force. But Swenson never taught any western history, and indeed I had no idea I was headed that way except that there were facilities for it.

A new western history professor had come from Colorado that year. He was no youth himself. Leroy Hafen had received his PhD at the University of California under “Spanish Borderlands” great Herbert Eugene Bolton. He hadn’t found a job teaching but had become the Colorado state historian. Now, after at least twenty-five years with the Colorado Historical Society and a long list of publications in the history of the fur trade and exploration, Leroy Hafen came to the Y. I fell under his tolerant and benign influence. Richard Poll was still there and also had much influence on me. But for the first quarter and a half, I still had no idea I was headed into history—and certainly not into western history. But by spring quarter’s end, I knew I would probably be a western historian.

J. Peterson: What caused that realization to come?

C. Peterson: Well, I think the fact that sources were available locally for a master’s thesis.

J. Peterson: So it wasn’t Hafen. . . .

C. Peterson: Hafen had a lot to do with it, and so did Richard Poll. Keith Melville and Stewart Grow, two political scientists who awakened in me an interest in political history, and I minored in political science. By the end of spring quarter, I was an avowed western history major; and, in spite of Melville and Grow telling me that political science was where it was really at, I got a master’s in history with a local thesis.

J. Peterson: What was your thesis on?

C. Peterson: My thesis was on the administration of Alfred Cumming, Utah’s first Gentile governor who, with the aid of the US Army, replaced Brigham Young in 1858.

J. Peterson: At that point in your life, what were your career goals? What did you think you would do with a master’s degree in history?

C. Peterson: Oh, I thought I might get hired teaching at a junior college, and I thought that would be just fine. I wasn’t one who dreamed great dreams or aspired largely. I still had visions of Snowflake and remembered a high school teacher or two who had big families, worked farms, and busied themselves in church and public life. Together with Betty, I thought we might patch something together with a junior college position and a piece of land and raise twelve kids, maybe being locally revered like my father and her Grandfather Hayes and their wives had been before us. Like my mission, my decision to teach had much to do with loyalty to who I was and where I was from. Such a life had been good enough for Joseph and Lydia, my parents, and it would be good enough for me. I didn’t know that “you can’t go home.” And in a way, I have never come to know it; hanging on to your first self-image isn’t the worst thing you can do.

J. Peterson: And when did you finish your master’s degree?

C. Peterson: In 1958, at the end of the summer.

J. Peterson: And then what?

C. Peterson: Well, the year of 1957–58 was kind of traumatic in a number of ways. On the plus side, you [John Peterson] were born in August of 1957 and spent your life from when you were about ten months old until you were a year old in a jumper that hung from the clothesline post where your mother could see you while she typed my thesis. But some issues associated with graduate work and with history weren’t easy on my attitude toward the Church.

J. Peterson: So your studies in history had an impact on your attitude toward the Church?

C. Peterson: Yes, that’s safe to say. In the Orem neighborhood where we lived, there were three young liberal professors—my contemporaries who, without the dairy ranch interlude to slow them, had been off to the University of Indiana and other similar places. Assistant professors of English Dale Bailey and Lyman Smart lived within a block or two of me, and Kent Fielding, also an ABD, was beginning a prominent career in the BYU History Department. All three of them were in my seventies quorum. Although it didn’t make much sense, I was called to be the group instructor, and the lesson manual was Hugh Nibley’s Lehi in the Desert. Those three guys were regular in their priesthood attendance where they just tore me and Nibley’s book to pieces and tossed the bits around. Never leaving well enough alone, I carpooled with them, where in addition to Lehi in the Desert they savaged two brothers, the Bankheads—contemporaries who, dedicated to their own causes, were savaging the rise of intellectualism among Mormon professors. Altogether, it was a rugged transition from the placid conditions of my milking barn in La Sal.

Dale Bailey and his wife, Marilyn, would come walking down at night to find us already gone to bed and knock on the window, and we’d open it and talk family and university shop. Sometimes we’d return the favor. So we had a close, close relationship. And we liked the Smarts. The Fieldings we knew less closely, but they all three raged at anti-intellectualism the whole year of 1957–58. Together with a couple of other conditions at the Y, it threw me into a blue funk. That took quite a bit of getting over, but program-wise I got the pieces together. And that summer, I passed my defense of thesis, not with any great distinction, I might add. I got a B. I doubt that George M. Addy, who had taken over as my thesis director for Richard Poll late in the game . . .

J. Peterson: George M. . . . ?

C. Peterson: Addy. Richard Poll and I would have, I think, done a little better with the overall project, and maybe I’d have merited an A, but I didn’t worry too much about it. I had it done. I didn’t hear of many junior college jobs for holders of master’s degrees, and people kept telling me the likelihood of a guy like me getting a job was almost nil. But while I was doing research, I had ridden to Salt Lake regularly with a librarian named Ralph Hansen, who was also working on his master’s. Hansen told me that Ted Warner, a buddy of his who was teaching at Carbon College in Price, was going to the University of New Mexico to get his PhD, and his job would be up for grabs. So I hustled a letter off to Aaron Jones, president of what was then a joint high school and junior college. The letter got there before Warner had announced that he was going to leave. I guess Jones was impressed by my moving ahead. He had a big job; his hands were full; and I was Johnny-on-the-spot. By golly, I got the job. Before the first year was over, I think Jones was sorry. I don’t believe he thought I had the stuff that Ted Warner had. And, in fact, Warner had left a big pair of shoes to fill. He later became a professor at the Y and dearly loved it there. He became a close friend of mine. But fortunately, Aaron Jones retired himself and was replaced by Claude Burtenshaw, who became my champion. Within a short time, I came on as a creditable teacher in the junior college setting and loved it, and I have never enjoyed teaching more than I did those ten years, even though I was worked nearly to death with it. I taught not only all kinds of history but also two political science classes and one economics class. After a while, Burtenshaw suggested that maybe I ought to teach an agricultural class as well because of my farm background and because we were desperate for students. I taught one general agriculture course for a few quarters.

J. Peterson: Did you mention history in that lineup?

C. Peterson: Yes, I taught that agriculture class in addition to the history classes.

J. Peterson: How long were you at the College of Eastern Utah?

C. Peterson: I was there ten years. One year I was absent, so I really taught for only nine years, 1958 to 1968.

J. Peterson: What caused you to decide to go back to school for a PhD?

C. Peterson: Well, I guess finally the burden of being all by myself at CEU got to me. I felt like I needed someone with whom I could share history. I loved Price and its heritage and its attitude about western America and its loyalty to southeastern Europeans and how different it was from the rest of the state. All of those things I liked, but I had learned very quickly that when anyone said the word “history” in Price, the next words were “Butch Cassidy.” All true Price people believed that Butch Cassidy was buried up there in the back part of the city cemetery, along with another guy that the local sheriff had gone out and plugged. One old-timer named Abraham Powell, a close friend, repeatedly told me, “Butch Cassidy used to stay in my mother’s boarding house. I knew him lots better than I know you. Do you suppose I could tell who you were if you were dead?” He didn’t give me a chance to answer. He then said, “You bet I could. I could tell it was Butch, and I could see the holes where those two bullets came out of his back. I could have put my fist in either of them.” He then summed up, “Butch Cassidy is up there dead. He didn’t go to South America and do all those things in all those stories.” So I learned that although Price was a wonderful place to live, it was a lonely place professionally. A blossoming historian needed somebody to talk shop with. As it turned out, I found plenty.

J. Peterson: Before we leave the topic of Price, were you so busy with teaching that you didn’t get to do much research, or were you also doing historical research and writing during this time?

C. Peterson: Yes and no. At first I threw all my Governor Cumming notes away and swore I would never go on for more schooling. But I changed my mind on that assumption, too. I kind of got over whatever it was that made me feel so down at the heels the last months I was in Provo, and I perked up some. In a tiny student body, say 350 to 500, I competed head-to-head with psychologist Joe Salvator for control of the “big classroom,” which held 105 students. The lecture floor contact in world civilization and American history thrilled me. On the other hand, processing class work with the aid of a sophomore assistant absolutely decked me. Good students kept me alive—especially those in brown-bag, no-credit weekly lunch discussion groups that surrogated for graduate seminars during the last years I was there.

J. Peterson: When did the things like the Doris Duke project take place—you know, our visits to the Hopi country? What were you involved in that for? That was Price time.

C. Peterson: Yes, that was Price time, but late Price time, the summer of 1967. The first two or three years down there I was determined not to go back to school at all. Then I began to think of going back, and by 1962, I tried sticking my toe in the pool and took a summer course at the U of U called “Utah and the West,” which a group of western historians put on in a seminar kind of context as a two-week course. Levi, my brother, and I took it together. I stayed at his Stadium Village apartment. Among other things, he introduced me to The Big Sky, by A. B. Guthrie, and I fell irretrievably in love with the mountain-man West. I also ran into an old friend of mine at that seminar, Brig Madsen, who by this time had finished his PhD and had left the Y and had, I believe, gotten started with his Peace Corps activities. I went up to him and asked him, “Dr. Madsen, you got your degree after you had a family, and you did a lot of it working your way through school as a carpenter. I’ve got four children. What kind of school should I go to, a name institution or one close to home?” He said, “It strikes me that you’ve got a good job down there in Price. Hang on to it, get an occasional leave, and go to some Mountain West institution. Don’t worry about a name institution.” With that advice, I began to negotiate to get into the University of Utah.

During 1962, it became apparent that a former missionary companion of mine, John Tucker, was going to be president at CEU. That boded well for me. John made me his dean of instruction. Although he wasn’t able to get a sabbatical leave for me, he did give me a leave of absence that guaranteed such perks as my situation at CEU held, and I took off for 1963 and 1964. Ed Geary, who now [as of 2002] heads the Redd Center at BYU, an English professor with a good perspective about history and western American literature, came to take my place. He didn’t teach any of the classes I’d been teaching, but he took my salary.

Beginning then (in 1963 and 1964), I began to think about writing and publishing. The first historical figure I took up was Thomas L. Kane, friend to the Mormons. He had not been a major factor in my MA studies, but I had become acquainted with him because he played a critical role in the Utah experience of Governor Alfred Cumming, the figure I’d written my thesis about. I’d found some good stuff on the time Kane spent in southern Utah and the plans he and Brigham Young had laid to establish a port at Guaymas in Mexico and launch Mormon colonization in that direction. I did a serviceable paper on him that I read at three or four historical gatherings throughout the state. I never did get it published, unless how it shows up in Take Up Your Mission, my first book, counts. But I’d talked some to Everett Cooley, and he had seemed interested in it.

J. Peterson: What had Everett Cooley been doing?

C. Peterson: He was the director of the Utah Historical Society at this time and editor of the Utah Historical Quarterly. So I was beginning to have some contact with historians. He was state archivist in 1957 when I became acquainted with him and with Russell Mortensen, director of the society, when I did research for my master’s thesis at the society. But more important in getting me in touch with history were the dozen or so candidates for PhDs whom I met at the U of U when I started my residency there.

By this time, the U was the mother institution to the College of Eastern Utah, and as John Tucker’s second in command I had contact with some of the deans at the University of Utah, while at the same time I was the lowliest of flunkies in the History Department. Presidents Ray Olpin and James Fletcher treated me like a dean, and one or two of the deans treated me like their colleague. So it was kind of an interesting tightrope to walk. But I got through successfully.

I got my PhD from the U of U in western American history in 1967. My thesis was on Mormon colonization along the Little Colorado River. I renamed it Take Up Your Mission. It was published by the University of Arizona Press, and many people liked it. I suppose it’s the most important thing I ever did. My graduate studies were well directed by Gregory Crampton, a superb human being and a student of Herbert Bolton, one of those great University of California historians—and, as a scholar, equal to the best of them. He was backed up by Russ Mortensen, by this time director of the University of Utah Press, and David Miller, a tall, gangling man, chairman of the History Department and a tremendous friend in the times that lay ahead.

The PhD candidates at that time, a dozen or so of us, have stood our ground throughout long careers in universities all over the United States. I am proud to be one of the graduates of the U of U’s history PhD program during that 1965 to 1970 period. We lacked the cohesive presence in the western history field that led some to make jesting reference to the scholarly phalanxes turned out by midwestern and southwestern graduate schools such as the “Texas Rangers” or the “Oklahoma Mafia.” Similarly, Mormon/

J. Peterson: What were the names of some of those U of U PhDs again?

C. Peterson: Richard Sadler and Richard Roberts at Weber are two; Glen Leonard at the Church Department of Museums; Stan Layton, distinguished editor of the Utah Historical Quarterly; Joe Cannon at BYU Idaho; Bart Olsen at Cal Polytechnic; Floyd O’Neil at the U of U’s American West Center; Burt Marley at Idaho State; and Dirk Raat and Dennis Lythgoe at Eastern schools constitute a fairly complete list. And there was David Folkman, an Air Force major, who made more money than any of our professors while on leave from the academy. They were great colleagues. We held forth in the Rosenbaum Room in Orson Spencer Hall. For a year or more, I had the wonderful privilege of sitting across a desk from my brother Levi, who was getting his PhD in English under Don Walker, who specialized in western American literature.

J. Peterson: Not Norton?

C. Peterson: No, I believe that’s my oldest son, Joe’s, friend who entered our consciousness later. But Don Walker wrote articles that we accepted for the Western Historical Quarterly. He seemed as much a historian as he was an English professor. To sit there with Levi for a whole year, at a time when I was going through these exciting things, was just great. I can hardly express how fulfilling it was to have somebody I could talk with about what was happening in my mind. The classroom experience was marvelous. I loved those senior western history professors. They have remained my close friends ever since.

J. Peterson: What kind of issues did you run into writing about the Mormon community you grew up in—that small, tight-knit Mormon Country group that you described earlier? Now you’ve been away from them for some years and can reflect on the fact you have written about your home country and its history from a secular and intellectual point of view. What kind of things should be said?

C. Peterson: There aren’t many things that could be called exposés in my Mormon colonization book. There is a lot of candor, however. I brought new understanding to the role of the mission as a colonizing institution. I talked about the truncated dream of converting the sons and daughters of Laman, I talked about polygamy like it was, and I talked about the United Order like it was and about the persistence of cooperation and brotherly love and also that there were rifts, warts, and blemishes that made life difficult. I found out quickly that many people in my home locality loved what I had written, but some of them also took offense at things that more or less “came out in the wash.” In effect, I had taken prized pieces of a region’s parlor-room conversation and worked them into my history and shown how they connected with the larger written word. When they found themselves face-to-face with what they thought was reserved for Sunday afternoon in the privacy of their front rooms and saw it in print, some were offended—even by the benign treatment they got from me. A few thought I had been unfair to their family or had told stories that I ought not to have told. My mother broke into tears when she got to the section about a United Order settlement coming from Lot Smith to her father, making him as affluent as he ever was.

J. Peterson: Why would that make her cry?

C. Peterson: She thought I was reflecting adversely on her father.

J. Peterson: I guess I don’t understand what you mean by a settlement from Lot Smith making her father rich.

C. Peterson: Well, “affluent” wasn’t a good word to use. Nobody ever got rich in those Arizona United Orders. Her folks had been in the Sunset United Order, headed by Smith, and when complaints continued to roll in after it had been disbanded, the Church sent a team of Apostles and local stake presidents in. They analyzed his business, calculated it, and redistributed it. Levi M. Savage, my grandfather, got a substantial cut out of it that he wouldn’t have had if he had taken the division Lot initially offered. It almost certainly was the time in Grandfather’s life when he was best off financially. When I wrote, it had been three-quarters of a century, but a few people still remembered the bitterness.

But I remember best the good things that were said and how they made me feel. In my high school years, I had little concern for scholarly things. I felt dumb and comforted myself with the idea that the common man was the backbone of democracy and continued to feel that scholarship wasn’t important throughout my animal-husbandry years. But feedback on the Little Colorado book suggested that most of the local Mormon community appreciated me as a scholar. Now that’s a very small group, I’ll grant you, but it still shocks me to find this mediocre kid, hiding in anonymity’s guise, accepted as one of the locality’s top scholars. There was no tendency to look at my work like the Mormon community looked at No Man Knows My History or even like it looked at Kimball Young’s sociological analysis of polygamy.

J. Peterson: What role has Take Up Your Mission had in your career since then?

C. Peterson: Well, I think the book was well received. And it surely became the primary vehicle for my development and movement in Mormon history. It even had considerable influence on my opportunities in western history, and it had some influence on the role I played in the American Association for State and Local History. Maybe most easily reckoned is the fact that my salary raises were a little better after it came along.

J. Peterson: What was its relation to your role in Mormon history?

C. Peterson: I’ve been president of the Mormon History Association, and I was one of the founders of the Journal of Mormon History. You might say I wasn’t really elected to be president of the Mormon History Association. I believe Leonard Arrington, for many years the Grand Pooh-Bah of Mormon history, wanted me to be a leader in the Mormon history movement, and he managed it. But I suspect the same thing happened to many others who have been president of MHA. He was favorably impressed, even before he saw the book, by an article I had written on Lot Smith, “A Mighty Man Was Brother Lot,” that appeared in the Western Historical Quarterly. It was a good article, and I had a real eye-catcher for a title. I borrowed it from a great-grandfather, Lorenzo Hill Hatch, whose journalizing sometimes had a nice poetic cadence to it. I believe Arrington liked the work I had done on the Little Colorado and, perhaps, responded favorably to my stint as director of the Historical Society and consequently forwarded me for president of MHA.

Here I need to talk a little more about the University of Utah. After I graduated there, I went back to CEU and immediately decided that I ought to try to get into a four-year institution as quickly as possible. When an opening came, it was at the U, and, as it turned out, it wasn’t the best of opportunities. But I took it, nevertheless. It was a soft-money position in which I thought I could see implications of permanency. There was a strong faction in the History Department that wasn’t pleased with my showing up. They thought the department was already much too heavy in western history. As nearly as I could tell, most of them had seen me graduate with some pride and were happy about how I was looking, but for me to be coming back now, as even a soft-money colleague—that was another thing.

J. Peterson: What does “soft money” mean?

C. Peterson: Just that the money they rounded up to make my salary didn’t have a continuing appropriation back of it. They didn’t offer me a tenure-track position in the immediate proposal, but there were those who suspected the western historians wanted to make a hard-money, tenure-track slot for me, as indeed some may have. Let me say a word or two about how they put what I was paid together. First, they found a half-salary in the department and then another half from the Organization of American Historians [OAH], where I was made acting executive secretary of a three- or four-thousand-member national organization. This element of the proposition drew me immediately out of Price, where I knew Butch Cassidy’s sort better than I knew scholars. Rubbing shoulders with the finest historians in America as an officer of OHA, I became privy to all the issues that were in their minds and worked closely with their leaders. It was a position that would last only a year or two at most.

At that time, Martin Ridge, editor of the Journal of American History at Indiana, and Ray Billington, resident historian at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, had masterminded a deal creating the Organization of American Historians and the Western History Association out of the old Mississippi Valley Historical Association. With those two nationally known historians, I became part of a triumvirate of power in as unlikely a set of circumstances as human beings could have contrived. Simultaneously, a powerful faction of young history professors at the University of Utah went into a full-court press against the old western history crowd, whom they outnumbered badly. They made it clear that I wasn’t going to spend another year at the U of U. They tried to talk in kindly terms to me, but several of them played the ugliest of politics with their old teammates in the department. For a few weeks that dark winter, it looked like I would be unemployed.

But fortunately, things were moving rapidly. Everett Cooley, who had been at the Historical Society, ended his tenure there December 31, 1968, to accept a position at the university’s new Marriott Library. The same qualities that made me appeal to the OAH as an administrator suggested to some that I could offer myself as a candidate for the director of the State Historical Society. It would at least be a job so I could feed my family the next year. So I applied, and, in due time, the senior scholars who had taken the flack of the “young Turks” at the History Department got me elected as the director of the Utah State Historical Society.

J. Peterson: Elected or appointed by the governor?

C. Peterson: I was appointed by the governor. I took over with an established staff.

J. Peterson: You were there for three years?

C. Peterson: From January 1, 1969, to September 1, 1971.

J. Peterson: At this time, wasn’t the Historical Society located in the Kearns Mansion?

C. Peterson: The Historical Society was headquartered in the grand but deteriorating Kearns Mansion on South Temple Street. Utah was awakening to preservation as a historical responsibility, and two great centennials were underway. In the legislature, an administrative struggle to retain the State Archives was being lost, and at the society itself, some of the greatest issues of an excellent journal of state history were in the offing. In addition to a good staff, Cooley left a superb bunch of manuscripts in process for issues of the Utah Historical Quarterly on the joining of the rails at Promontory in May 1869 and on John Wesley Powell launching his run down the Green and Colorado Rivers in June of the same year. Although they bore my name as editor, much credit for these benchmark issues of the Quarterly should go to Everett Cooley, as should the second issue of 1970, Helen Papanikolas’s Toil and Rage in a New Land: The Greek Immigrants in Utah, one of the most important social histories ever published about Utah. Altogether it was a period from which I take great satisfaction.

J. Peterson: So along with the directorship of the Historical Society went the editorship of the Utah Historical Quarterly?

C. Peterson: That’s correct. Before I left, I had an assistant who was the editor of the Quarterly, but during my first year at the society, I was doing it all like Cooley had done. As I say, one has to give Cooley a lot of credit. But I think I managed the transition quite effectively. Those were prominent ceremonial events in Utah, and I remember my role in that grand celebration with pleasure. In fact, both of them were great fun. Take, for example, receiving at the State Capitol the famous golden spike from Stanford University, where the same Ralph Hansen who tipped me off about the CEU opening was by now archivist in charge of that valuable relic. With a fleet of state highway troopers keeping tabs on us on May 10, 1969, we hauled that spike up to Promontory so a ceremonial “driving of the last spike” could be repeated. Also arranged was a commemorative river run from Ouray down the Green to the town of Green River in honor of John Wesley Powell’s great achievement. Making up our crew were Doc Marsden, the foremost authority on Utah river running and a crusty Powell detractor; Wilbur Rusho, historian for the Bureau of Reclamation, and his two sons; George Stewart, a Uinta Basin lawyer who was dedicated to western history; and me.

J. Peterson: Moab?

C. Peterson: No. The place you let me off was Ouray on the Green River in the southeast part of the Uinta Basin. You were there all right. You took me to the river that June morning.

J. Peterson: Yes. That’s funny. I remember just being on the Colorado down in Moab, but I remember your climbing into the boat. Was it above Split Mountain?

C. Peterson: No, Ouray is below Split Mountain but above Sand Creek. We floated for three days and, in the process, contacted three or four flotillas that had come down from Green River, Wyoming, through Split Mountain Gorge. They had faster boats than we did, and they caught us. Most of them were representatives of major magazines in California.

My predecessors at the society continued to open doors for me. Russ Mortensen, by then teaching and editing the American West, arranged for me to get to know Yale’s Howard Lamar, who had written about Utah’s territorial experience. Lamar agreed to give the keynote speech at the 1969 annual meeting. Political scientist Jean White from Weber State and historian Henry Wolfinger from the National Archives also read distinguished papers on Utah statehood, and I had the makings of another significant issue of the Quarterly. After the near disaster of 1968, things went rather well at the society.

I can’t take a lot of the credit. Good friends got me the job. Sometimes I felt like they saved me from being in the soup line down there on Fourth West and Third South. But the society’s path actually led to Utah State University. My friends Gregory Crampton, David Miller, Russell Mortensen, Brigham Madsen, and Lyman Tyler at the University of Utah History Department arranged things for me to make that transition. To their names ought to be added Everett Cooley, who, in coming to the Marriott Library as curator of western Americana, left the society in great shape, thus saving my bacon.

We kept getting good articles, and the Quarterly remained strong—and maybe even strengthened some. I made arrangements with Greg Crampton and Tom Alexander to edit respective issues of the Quarterly on Native Americans and the environment. Among other things, having guest editors allowed me to justify publication of my own articles. So altogether in the less than three years at the society, we had at least five significant issues.

In the meantime, things were moving rapidly elsewhere. When the Organization of American Historians was established, the Western History Association [WHA] was also organized to absorb western American scholars and other regional friends of history. Interestingly, Ray Billington and Martin Ridge were also central in this development, and together with Bob Utley, chief historian of the National Park Service, and a number of others, we were struggling to define what the nature of this new association would be and what publications would represent it. Even more interesting to me was the fact that I also became involved in the process.

One of the chief battlefields was the American West, which, as noted above, was edited by Mortensen and Crampton at the U of U. It did very well to begin with, serving as a richly illustrated “popular but sound history”—kind of an “American Heritage of the West.” It was bankrolled out of California in some measure and, over a period of years, was captured by environmentalists, who made it a glossy advocacy magazine, abandoning more traditional interests in western history and coming into complete loggerheads with the history professor core of WHA.

Two Utah State University professors took advantage of the resulting hiatus to work on serious history when they sold the Western History Association, and Utah State University worked on establishing the Western Historical Quarterly as an outlet for scholarly articles on the West. These professors were Leonard Arrington, an economic historian as well as the father of the New Mormon History movement, and historian George Ellsworth, who, according to Arrington, taught him all he knew about the historian’s craft. Arrington was the more skilled negotiator, and he manipulated things through regional and national associations and pinned down enough institutional backing to pay for it, although Ellsworth’s holding the journal together during its incipiency was a major achievement. As early as the summer of 1970, they began talking to me about coming to USU as the associate editor of the new journal and member of the history faculty in a tenured, hard-money situation. They put that together, and I went to Utah State in September 1971. As I left the Historical Society, Mel Smith, who had come aboard as director of preservation programs, stepped into the society’s directorship. By this time, Glen Leonard, who shortly after moved to the Museum of Church History, was editing the Utah Historical Quarterly and heading up a state pilot project in museums we had underway with the American Association for State and Local History. Mel Smith was able to pull in U of U PhD Stan Layton as editor of the Utah Historical Quarterly, which worked out very well indeed, with Layton editing the Utah Quarterly for upwards of thirty years.

I was finally into a hard-money position where I got to help firsthand in the inner workings of the Western History Association. I’d been part of the OAH’s transition from regional society to national professional organization. At that same time, I also had a springboard into the great national organization for people concerned with state history, the American Association for State and Local History [AASLH]. Opening the way for other Utahns was the role of the redoubtable Kate B. Carter, longtime president of the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, who in the early 1940s had been one of the founding members of AASLH.

J. Peterson: That fits Kate.

C. Peterson: Yes, it does. Mrs. Carter was deeply respected. But during their tenure at the Historical Society, Mortensen and Cooley were anything but high on her. In fact, they boiled inwardly that her lobby succeeded in winning a substantial portion of the tiny appropriation for state history for the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, which struck them as a thoroughgoing Mormon organization. Nevertheless, there’s little question that she broke the path into the inner circle of the AASLH for them, just as they broke a path for me. By the early seventies, Mortensen was moving toward becoming AASLH president, and both men had been on its council and on the awards committee, which was the most powerful of the organization’s committees at the time. In effect, they said, “Well, look. We got this guy down at the Utah Historical Society. He needs your help. The society will be stronger if he’s connected.” And the first thing I knew, I was on the awards committee, where I sat for eight or ten years. From it I gained ringside access to what was going on in state history all over the United States as well as in Canada and in the Caribbean Islands. From that, I went onto the board and its executive council. I don’t suppose I could’ve ever made it to be president. I maybe should have kept hanging in and trying.

But I was selected to write the Utah volume of the States and the Nation series, the AASLH’s flagship bicentennial effort. Russ Mortensen was secretary and a member of the national board of that series. In fact, he came near being its action wing as far as choosing who would write the books and run the editorial offices.

J. Peterson: This is the bicentennial book?

C. Peterson: Yes. Utah: A Bicentennial History.

J. Peterson: It’s part of a fifty-volume set.

C. Peterson: Right. W. W. Norton published it. Mortensen wanted Wallace Stegner to write the Utah volume, and his second choice was Fawn Brodie, but he knew if he failed to land one of them that he had me in hand because he had been on my doctoral committee and because I owed it to him because of his many kindnesses to me. He lined me up tentatively at a conference in Edmonton, Canada, midsummer of 1971, and then messed around until late the next spring, trying to line up one of those writers with a nationally known name. I admit they’d have been good prospects. I don’t think there are finer historians or better writers. He put me in the running late in the spring, not any quicker than that. But I was still grateful to Russ for getting it for me. Not only that, but I was also able to return the favor. They weren’t being successful in lining up anybody to do Idaho, and I was able to get my office mate, Ross Peterson, to do it—at least we shared the same phone through the wall at Utah State.

J. Peterson: At Old Main at Utah State.

C. Peterson: Yes. Ross Peterson, who wrote the Idaho volume in the States and the Nation series. So those were exciting times. I had come on fast, and Arrington exercised his influence and got me on the board of the Mormon History Association. He had at about this same time become Church historian and was putting all his machinery together, and I served satisfactorily, I suppose, as an MHA board member for three or four years, maybe five. Then, I was nominated to be president. I also got two more books published during this same period, the Mormon Battalion Trail Guide and Look to the Mountains on the national forests in southeastern Utah. Then, in September of 1971, we took up our place in Logan.

J. Peterson: You’ve told stories in the past of early conferences and of discussions with Bob Flanders and other RLDS Church historians and interactions there.

C. Peterson: One of the amazing things about the Mormon History Association was Leonard Arrington. He was ubiquitous. Any action found him near its heart. He helped create the Western History Association. He got the money to finance the Western Historical Quarterly, he put things together to become Church historian, and he helped sponsor what became Dialogue and the Mormon History Association. He showed up at my defense of thesis in July 1958. From that point on, he was aware of me—and from 1962 especially so.

That fall of 1962, the Western History Association met in Salt Lake City in the Hotel Utah. I was standing on the mezzanine in a long line waiting to get registered, thinking that I knew absolutely no one. Immediately in front of me (it was the first western history conference I ever went to) stood this short, fat fellow—pleasant and balding—a chicken farmer from the Twin Falls, Idaho, area. Leonard Arrington and I talked for what seemed like a long time pretty much undisturbed. He spoke candidly about his interests and prospects, like I was his peer. I was enthralled and flattered. At that moment, he was quite pessimistic about things at the Church Department of History; they weren’t letting him in. He was moving into secular history, particularly into the study of World War II’s impact on the western states, including Utah, and he talked to me with excitement about those things. Even better, he was pleased to see me trying to break out of the situation at Price and broadening my field of enterprise. Leonard’s presence was a factor from there on. Later, I learned that at almost any and every history conference, Arrington collected Mormons attending and had a late night klatch, kind of a roundtable discussion where each of us made a progress report.

Also a close friend was George Ellsworth, with whom I worked for a decade at the Western Historical Quarterly. To work closely with me could not have been easy for him. He was the ultimate perfectionist in the historical method. The Western Historical Quarterly showed it from front to back during the entire nineteen volumes with which I was associated. I think that more recently they’ve kind of lost the taut conservatism that characterized George’s work. I learned tremendously from him, and he helped me in many, many ways. For the first eight or nine years, I was his understudy, and then I was editor in my own right. In the progress of those years, I met and corresponded with thousands of the best men and women in western history. We all did our best. The articles that were published did much to shape the course of scholarship during an era that changed thinking about the West dramatically.

J. Peterson: Tell us about your association with Bob Flanders and others who were interested in Mormon as well as state and local history.

C. Peterson: The fraternal aspects of the New Mormon History came on quickly for me and reached deeply. That opportunity with the Awards Committee of AASLH was one dimension of it; the opportunity of involvement in Mormon history was another; and western history was yet another. Not satisfied with all of those, I also got invited to join Forest History Society’s board of editors and then sat for many years on the Forest History board itself.

J. Peterson: So no longer were you Charles Peterson all alone at Carbon College with your brown-bag student group or with Levi in your discussions at the graduate reading room, but you were having lots of people to talk to and bounce ideas off of.

C. Peterson: Right, and different ideas came from all directions—opportunities and cross-fertilization of every kind came as well. I found myself able to move well in those circumstances. I worked closely with people like Ray Billington at the Huntington Library and Arthur Link at North Carolina. Looming especially in my life were scholarly friends such as Harold “Pete” Steen and Marion Clawson in forest history, and pushing into my memories of AASLH were the admiration and affection I had for Jim Moss at the San Diego and later Arizona Historical Societies and Nyle Miller and Tom Vaughn, respectively, at the Kansas and Oregon state societies. I’ve been so far away from these people that their names have all but left me. I’ve had a lot of opportunities, but central to everything was the Church because it has been central to my life and because the Church is central to a lot of things here in Utah, as it was to the Mormon History Association. Among the most influential, and just fun and stimulating, were friendships with historians from the Reorganized Church, or the Community of Christ as it is now called, the RLDS as I have referred to it here. Among those I knew best were Bob Flanders, Mark McKiernan, Alma Blair, and Paul Edwards.

J. Peterson: Alma Blair?

C. Peterson: Alma Blair, yes. But Paul Edwards was probably the finest mind I’ve met anytime in any place. One way or another I had a succession of meetings with these fine RLDS scholars that sometimes lasted for three or four days. One summer in the early 1970s, McKiernan and I went to a set of conferences at a succession of living-history farms. I rented a car, and we drove for several days around the Nauvoo area and to Lamoni, Iowa, where Graceland College is located—the RLDS institution of higher education where Edwards and Blair had faculty appointments. We spent several nights together, during one of which we talked all night. A year or two later, there was a symposium in Chicago on Indian studies, to which Bob Flanders had been invited from the University of Southwestern Missouri. Somehow he and I were put in the same room. Again, we talked nights. If we didn’t talk all night, it was darn near all night. Although it is difficult to assess objectively, I do not think this influenced me religiously. Nevertheless, they gave me a different view of who I am by letting me see myself in the refraction of the RLDS cultural mirror. And social or cultural things that I thought were outlined specifically one way began to take on a little different form. It was more interesting, I think, than it was . . .

J. Peterson: Life-changing?

C. Peterson: Yes, life-changing. But I admired them, I respected them, and I loved them. Then, after a flurry of contacts into the late 1970s, my interaction with them began to slow down. Flanders showed up once at the Jensen Living History Farm in Logan shortly after I severed my relationship with USU’s museum program. We looked off from that bucolic setting toward Wellsville and Mendon and beyond the ascending dryland farms to the Wellsville mountain range. We talked of “reading the landscape” as we contemplated the different contexts of agrarian Mormonism—the two towns laid out in square blocks and the nearby commuter farms—and as development pushed farming to increased elevations, we traced the successive swaths of highline canals and last of all the newer sprinkler-pipe extensions and dry farms phasing up the benches of the Wellsville Mountains. The last time I was with Flanders was at a WHA conference in Wichita, Kansas. I glimpsed him first at the Wednesday “happy hour.” He seemed to brush me off initially, but I kind of hung with him for a minute or two. He had suffered so much flack from the RLDS people on his book.

J. Peterson: Nauvoo: Kingdom on the Mississippi?

C. Peterson: Yes, that one. He had finally decided that it was not worth keeping his association with Mormons of any kind. But pretty quick he relented, and we had a good talk. And we ended up going on a bus tour to Abilene and once there indulged an affection we both felt for Eisenhower at the Presidential Library, where we walked together in the late afternoon. I admired what he did well that I only floundered at; it elevated me to find myself in the presence of a stimulating person and to have things in common. In a way, this characterizes the whole of my associations during these years. Again and again I found in knowing them ways to know myself better and to stimulate my interest in my life and the life of my people and the things and places with which I was involved.

J. Peterson: You know what intrigues me as I listen to this is that rather than looking inward in terms of Mormon history and in all of your cross-fertilization coming from Mormons, your experience has been outward. I remember at an earlier time, actually in my youth, your talking about the difference of being a big fish in a little pond or being a little fish in a big pond, and you have made a point to being the little fish in the larger pond, not just being content to be a member of the Mormon History Association, but reaching out to a much broader community. Do you care to speak to that at all?

C. Peterson: Well, yes. I think so. I think that’s a fair assessment of what I have expressed and how I feel about the AASLH experience especially—those weeklong sessions we would have with the regional chairpersons for awards from thirteen regions in the United States and Canada and one or two down in the Caribbean. We would start at seven in the morning and run until midnight. Delegations would be in, pushing a book from this area, or a restoration from that, or a children’s program from another, or a state board for museums. We’d give them fifteen or twenty minutes, and then we would hash it out in some of the finest give-and-take I have ever witnessed. Increasingly, I found myself being one of those who could see across fields. When I went to USU, to my initial disappointment, Glen Taggart, then president, caught me and said, “Look, Daryl Chase,” his predecessor and one of those Chicago three whom we mentioned way back early tonight, “has left me with a millstone and I want you to lift it.”

Taggart wanted me to manage the Jensen Living History Farm. This got me into museum work, made me closer to Bob Flanders and Mark McKiernon, who were doing related things in their areas, and, more recently, even opened the door to my friendship with Patty Limerick. As invulnerable as she seems, as a power on the lecture circuit and in western history, she has apparently been relegated to the University of Colorado’s version of the western history center, a kind of graveyard for professors whose prominence can no longer be countenanced by their departments. The point I’m making is that those things opened doors, and, in sitting with the AASLH Awards Committee, I not only knew books because I was an editor but I also knew museums. I knew something about restoration, as well, from my experience at the Historical Society. So I had a pretty broad kind of base to move from, and it made lots of good friends for me.

In the Forest History Society, circumstances were quite different. Among their primary purposes was the task of raising money. For this to succeed, they needed a university base and had one at Santa Cruz, near San Francisco. But big timber in the Northwest was about gone, and the industry wasn’t as wealthy as it had been. Raising big bucks in the Far West was not as easy as it had been, so that was an ongoing topic of discussion. With increasing urgency, we talked about places all over the United States for several years. Among other suggestions, I proposed that we bring the Forest History headquarters to USU. Utah State had a number of things going for it, including one of the early forestry schools in the West, an extremely good natural resources college, a strong western history program, a strong western American literature program, and considerable experience in publication of scholarly periodicals. The people from the East put together a package at Duke University, and we visited both places as the list of possibilities narrowed down. I had dickered with President Stan Cazier, a historian himself, about how much the university might help, and I had a couple of board meetings in Logan to see how air traffic worked and if Utah’s liquor laws could be met without drying the board out completely. With accessibility being among the determining factors, the new headquarters finally ended up going to Duke. It was almost certainly the right thing to do. But the effort to get it had been real, and its success would have entailed a few more years before I retired at USU and perhaps continuing activity with forest history.

J. Peterson: Let’s talk about the New Mormon History movement. When did you become aware that the kind of history you were doing and that Leonard Arrington was doing and that others were doing was something new or something different as far as Mormon history was concerned? Or was it something that you kind of learned later and looked back and said, “Oh, that was something that . . .”

C. Peterson: People began to talk about it by the late 1960s. I’m not sure when the idea was accepted or when an organization came into being. Leonard moved into the Church Historian’s Office in ’72, and it wasn’t too far from then that I think we began talking in terms of the New Mormon History. MHA annual meetings began to grow in size and began to attract bigger groups of people, and yet they were peculiarly Mormon. MHA really had relatively few established scholars, but interest was high, and a large percentage of the participants were producing papers and doing it almost annually. Mormon historians and would-be historians were prodigiously busy—busy doing other things and busy studying Mormon history—perhaps rarely taking the time to delve deeply. One characteristic of the movement was the great number of studies presented, and related was the large percentage of people going to conferences who attended the sessions.