Prologue

Latter-day Saint Missionary Efforts in South America, 1851–1947

Richard E. Turley Jr. and Clinton D. Christensen, "Prologue," in An Apostolic Journey: Stephen L. Richards and the Expansion of Missionary Work in South America (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), xi–xxxvii.

An Ongoing Charge to Preach the Gospel Worldwide

In concluding his forty-day postresurrection ministry, Jesus Christ commanded his disciples:

Go ye therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost: teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you: and, lo, I am with you alway, even unto the end of the world. Amen. (Matthew 28:19–20)

When the American prophet Joseph Smith and his associates formally organized the Church of Christ on April 6, 1830, they understood it to be the restoration of Christ’s ancient church and took seriously the New Testament charge to take the gospel to all nations and peoples.[1] Even before the Church’s formal organization, believers spread word of the new movement to regions surrounding where Smith and his family lived in upstate New York and northern Pennsylvania.[2]

The Prophet Joseph Smith translated an ancient book of scripture that became known as the Book of Mormon. Before the book became available for sale in March 1830, believers with access to press galleys took portions for others to read, and a local journalist with after-hours access to the printshop began pirating major segments of the volume in his own newspaper.[3] When the book became available in its entirety, readers discovered that its title page represented the volume as a modern translation of an ancient book of scripture intended for “the convincing of the Jew and Gentile that Jesus is the Christ, the Eternal God, manifesting Himself unto all nations.”[4]

Early efforts to take this restored gospel to all people included famous missionary forays by Smith’s younger brother Samuel. His labors led to the conversion of Brigham Young, the man who would succeed Smith after the founding prophet’s death at the hands of vigilantes in 1844.[5] During Smith’s lifetime, Church members spread the gospel message throughout much of the United States, Canada, and the British Isles; to portions of continental Europe, the Middle East, and Australia; and even to the islands of what became French Polynesia.[6]

Early Missionary Interest in South America

One of the most famous efforts to spread the latter-day gospel occurred just months after the Church’s organization when a revelation received by Joseph Smith called his closest associate in the work, Oliver Cowdery, and ultimately three companions to preach to native peoples of the Americas.[7]

A Call to Teach Native Peoples

One of Cowdery’s companions was Parley P. Pratt, later dubbed by biographers “the Apostle Paul of Mormonism.”[8] Pratt’s mind was far-reaching, and he took seriously the revealed missionary charge that “he shall go . . . into the wilderness among the Lamanites,” a Book of Mormon term for ancient peoples of America that Church members of his generation interpreted to mean America’s Indians.[9] Cowdery, Pratt, and their companions endured bitter winter cold and other harsh conditions as they moved west to the frontiers of the organized United States to commune with Indian peoples who had been pushed to the nation’s margins.[10]

The Latter-day Saint missionaries soon found themselves forced out of Indian territory by government agents tasked with protecting native peoples from the kind of exploitation that had marked centuries of interaction with colonial Europeans. But the mission journey was not a total failure: they found great success among Pratt’s former associates in Ohio, many of whom joined the fledging Church.[11]

Parley P. Pratt’s 1851 Journey to Chile

Pratt never forgot his original charge, and when he followed Brigham Young west to what became Utah and received responsibility over the Church’s new mission in the Pacific, he studied Spanish and made plans to take the Latter-day Saint message to the native peoples of South America whose nations bordered the Pacific Ocean. To that end, Pratt left in 1851 on a cargo ship for Chile, accompanied by two companions: his ailing, pregnant wife Phoebe Soper Pratt and Rufus C. Allen.

This small missionary group suffered immensely before arriving in Chile, where they encountered language challenges, limitations on religious liberty, and soaring inflation. They also faced political challenges, ran out of money to support themselves, and failed to secure employment to replenish their stores. Most notably, Phoebe suffered through an excruciating labor, giving birth to a son, Omner, who died a few weeks later. The Pratts buried their son and returned with Allen to the United States in 1852, feeling their labors had failed.[12]

Further Missionary Setbacks

After Pratt and his companions arrived in the United States, but before they returned to Utah, Latter-day Saint leaders in Salt Lake City held a conference on August 29, 1852, in which Pratt’s brother Orson officially announced the Saints’ longtime practice of plural marriage. To offset the public relations firestorm they knew would ensue, and to gather believers as part of their millennial message, the leaders called some one hundred missionaries to take the message of the restored gospel throughout the world. The leaders assigned missionaries to serve in North America, South America, Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia.[13]

The missionaries called to South America were directed to British Guiana on the northeast coast of the continent, apparently assuming that English influence on the colony would ensure that language and religious liberty would pose fewer problems than they had earlier for Parley P. Pratt and his companions in Chile. The two newly called missionaries, James Brown and Elijah Thomas, traveled to California and by sea to Panama, becoming the first Latter-day Saints known to reach Central America.[14]

The missionaries crossed the Panamanian isthmus and took a boat to Jamaica, which was then a British colony. In Jamaica they joined four fellow missionaries who had arrived by a different route.[15] The growing opposition to Latter-day Saints in the press, however, stopped the Elders Brown and Thomas before they could reach their assigned field of labor. Unable to get passage directly to British Guiana, they planned to first go to the island of Barbados. “After paying their passages” to Barbados, a Church historian recorded, “they were not allowed to proceed thither; the prejudice was so great against the Elders [missionaries] that the harbor agent or naval officers would not allow them to be shipped to any English island.”[16] By January 1853 formal efforts in the nineteenth century to take The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to South America had ended.

After Parley P. Pratt left South America in 1852, he wrote that he desired to go to Peru, where the political environment was more promising, but the missionaries had run out of funds. Pratt came to understand that Peru was more populated with native peoples than Chile was and thus more closely fit his original revelatory charge as a missionary. His plans to return to South America at some point were thwarted when he died at an assassin’s hand in 1857.[17] It was not until the early twentieth century that the next known Latter-day Saint, Alfred William McCune, traveled to Peru. Although not an ardent believer in the restored gospel, McCune, a mining and railroad magnate, went to Peru in 1901 as part of a multiyear effort to develop mines there and build a railway that would transport mining products to the coast for shipping.[18]

Mexico: Gateway for Expanding the Work Southward

Meanwhile, official Church efforts to reach Latin America focused on Mexico, which had been on the minds of ecclesiastical leaders during Joseph Smith’s lifetime. Latter-day Saint newspapers in Nauvoo, Illinois, repeatedly carried articles on Mexico, especially its relationship with Texas.[19] In 1843 Joseph Smith formed the Council of Fifty, a confidential administrative body that he charged with exploring future settlement sites for the Saints. The council looked at Mexico as a place for both settlement and future missionary work.[20]

Latter-day Saints were interested in Mexico, and Mexicans were curious about the Saints. Within a month of Smith’s death on June 27, 1844, a newspaper in Mexico reported his martyrdom as a subject of public interest.[21] Subsequent newspaper articles in Mexico featured Latter-day Saint history and scripture.[22] When Brigham Young led the famous Latter-day Saint pioneer company to the Great Basin in 1847, he settled the Saints at the foot of the mountains southeast of the Great Salt Lake and named the community after that body of water. At the time, the land where they settled (which later became the territory and then state of Utah) was in the Mexican territory of Alta, or Upper, California. After settling most of his party there, Young returned east, and for half a year the Saints in Great Salt Lake City worked on building their community in Mexican territory.[23] Before Young returned west in 1848, land ownership in the region shifted from Mexico to the United States with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2.[24] Later, when US president James Buchanan sent troops to Utah in 1857 to ensure the seating of new federal appointees among the Saints, who would rather have governed themselves, he had expansionist ideas that included nudging the Latter-day Saints into Mexico.[25]

During the Utah War, among the schemes to entice the Saints to move south of America’s territorial borders were one to get them into Mexico and another to the Mosquito Coast.

Recognizing that the Mormons would move again if they had to, “General” William Walker and a Colonel Kinney offered to sell to the church thirty million acres of land on the Mosquito Coast in Central America. Another proposition came to settle Sonora, in northern Mexico. Some officials in Washington seemed to regard the proposals as offering means of disposing once and for all of America’s “Mormon question” and were prepared to recommend that financial inducement be offered the Mormons to accept. But Brigham, determined if at all possible to remain in Utah Territory, did not carry these negotiations to the advanced stage.[26]

The Utah War of 1857–58 ended after questions posed by Congress about Buchanan’s military plans led to a resolution and peace commission.[27] However, before federal troops entered the Salt Lake Valley following a negotiated peace, Brigham Young and most of the Saints temporarily left Salt Lake for points farther south, and thereafter Young kept open an escape route in that direction, a pathway to travel in the event persecution forced him and his people to flee, as it had previously done in New York, Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois.[28]

The Saints returned to their homes after the Utah War, but Young kept looking south, especially after the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 led to an influx of people who were not members of the Church to the greater Salt Lake region. In 1873 Young ordered pioneering missionaries to cross the Colorado and move deeper into Arizona. The first efforts at settling the region failed, though later efforts proved successful.[29]

In 1875 Latter-day Saint missionaries published extracts of the Book of Mormon in Spanish and soon traveled to Mexico.[30] By 1876 Brigham Young saw Mexico as the key to preaching the latter-day gospel throughout all of Latin America and establishing settlements there. “I look forward to the time when the settlements of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints will extend right through to the City of Old Mexico,” he wrote, “and from thence on through Central America to the land where the Nephites [a Book of Mormon people] flourished in the Golden era of their history, and this great backbone of the American Continent be filled, north and south, with the cities and temples of the people of God.”[31]

Young died the following year in 1877, but his successor, John Taylor, authorized missionary work to Mexico City in 1879 and settlement in northern Mexico during the mid-1880s. Soon a Latter-day Saint mission sprang up, along with several colonies of immigrant Saints of many nations who worked the soil and sold goods in an effort to establish themselves on sound financial footing. They worked at learning Spanish, and many of the next generation learned it fluently. The Spanish language had proved an impediment during Parley P. Pratt’s first trip to Latin America, but subsequent generations of Saints living in Mexico, including many who descended from Pratt, would speak the language well and thus be able to communicate their missionary message throughout much of Latin America.[32]

Between 1885 and 1912, the Church grew among the Latter-day Saint immigrants to Mexico, if less so among the native-born Mexicans outside the colonies. In 1912 political problems forced most Anglo Latter-day Saints from Mexico. Some of them later returned to Mexico, where their descendants live to this day. Others remained in the United States and retained their ability to speak Spanish.[33]

Rey L. Pratt, a grandson of Parley P. Pratt, grew up in the Latter-day Saint colonies in Mexico and used his language abilities to steer the Mexican Mission for twenty-four years until 1931. During times of revolution and political problems, President Pratt’s contact with Mexican members kept the Church moving forward in a struggling country.[34] The Latter-day Saint colonies in Mexico eventually became a rich resource for missionaries and leaders with language skills to further the work in Mexico and serve throughout Latin America.[35]

Twentieth-Century Missionary Developments in South America

Andrew Jenson’s Central and South American Tour

The catalyst for establishing a permanent Latter-day Saint presence in South America was a Latin American tour taken unofficially by assistant Latter-day Saint Church historian Andrew Jenson, originally of Denmark. Jenson had become the Church’s most traveled official and had visited numerous countries. But he had yet to visit South America when he sought permission and Church sponsorship to do so in 1923.[36]

When Church leaders declined to sponsor his trip, he elected to go anyway, taking the trip as a vacation experience with the financial aid and companionship of a well-to-do sponsor, Thomas Page. Their travels from January to May 1923 took them coast-to-coast in the United States and through much of Latin America.[37]

“On my recent tour to Central and South America,” Jenson reported to senior Church leaders in July 1923, “I visited eleven different countries, namely Mexico, Guatemala, Salvador, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil, and while traveling I also obtained important information concerning other countries near the line of my journeyings, including Honduras, British Honduras, and Costa Rica in Central America, and Venezuela, Colombia, Paraguay, and Ecuador in South America, and the West Indies.”[38]

Two of the major problems that plagued Parley P. Pratt and other early missionaries to Latin America—the language barrier and lack of religious freedom—now seemed solvable in Jenson’s mind. Nearly a half century of missionary work and settlement in Mexico showed that Latter-day Saints now possessed the necessary language skills. And fortuitously, in all the Latin American countries, Jenson noted with simplicity, “the Spanish language is the prevailing tongue, with the exception of Brazil, where the Portuguese is the national tongue, though Spanish is understood there also by most of the inhabitants.”[39]

As for the lack of religious freedom, Jenson wrote, “Though the Roman Catholic religion prevails in nearly all parts of Mexico, Central America, and South America, and on many of the islands in the West Indies, there is perfect religious liberty in all, and I have reason to believe that, at least in some of the republics in both Central and South America, Latter-day Saint missionaries would be well-received.”[40]

Jenson went on to provide statistics on each country, “knowing, as I do,” he wrote, “that the Lord has commanded the Latter-day Saints to preach the gospel to every nation, kindred, tongue and people.”[41]

Melvin J. Ballard’s Apostolic Journey to South America

Besides pursuing a scriptural mandate and following Jenson’s recommendation, Church leaders had another reason for sending missionaries to South America. Latter-day Saint converts from Europe had migrated there, providing natural seedbeds for Church growth and expansion on the continent. In Argentina, German members had begun holding meetings, doing missionary work, and publishing articles about the Church. They had also opened correspondence with the Church’s Presiding Bishop in Salt Lake City, Charles Nibley, who spoke German and encouraged their efforts.[42]

In May 1925 Nibley became a member of the Church’s First Presidency, who had been talking about South America for months and now discussed how to respond to requests from the Argentine members for missionaries. “We have taken up with the Presidency the matter of sending missionaries to the Argentine, but so far nothing definite has been decided,” Nibley’s successor as Presiding Bishop, Sylvester Q. Cannon, informed his South American correspondent. “However, we are making inquiry with regard to suitable men who can speak the German and Spanish languages.”[43] Though the immigrant Church members in Argentina at the time spoke German, Church leaders were well aware that significant expansion of membership there would also require preaching in Spanish.

In their quest for the right people to send to South America, Church leaders counseled with linguist Gerrit de Jong Jr., who had just been named dean of the College of Fine Arts at Brigham Young University and professor of modern languages. Ultimately, they decided to send a member of the Church’s Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, the group who had been responsible for opening new missions since the first decade of the Church’s history. They also decided that “two men be sent along with the member of the Quorum of the Twelve, one to speak German and one to speak Spanish.”[44]

From among the Church’s Apostles, the First Presidency chose Melvin J. Ballard, a junior member of the Twelve who had been a mission president among native peoples in Montana.[45] To accompany him, the leaders chose two members from the next tier of Church leadership, the First Council of the Seventy: Rulon S. Wells and Rey L. Pratt.[46] Nearly a generation older than Ballard, Wells had substantial missionary experience that included missions to Germany and Switzerland, so his language ability was valuable.[47] Pratt, who had moved to Mexico with his family at age nine, was a former missionary and mission president in Mexico who later oversaw all of the Church’s Spanish-speaking entities before being called to the First Council of the Seventy in early 1925. He was the obvious choice for the Spanish-speaking member of the group.[48]

In November 1925, Ballard, Wells, and Pratt traveled eastward to New York and boarded a steamship bound for South America. During the ocean voyage, Ballard studied Spanish and South American history. The missionaries crossed the equator on November 25 and five days later docked at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. “I was the first one to put my feet on South American soil,” Ballard recorded in his journal.[49] After spending the day touring, they left at midnight for Buenos Aires. They paused for half a day in Montevideo, Uruguay, on December 5 and early the next morning arrived at their destination in Argentina, where the local German-speaking Saints welcomed them. After getting settled in their hotel that afternoon, the visiting missionaries held a meeting in which each of them spoke. They had begun their work in South America, a labor that would finally succeed on that continent.[50]

The three missionaries quickly made history. On December 12, 1925, within a week of their arrival, Ballard recorded in his journal, “Just as the sun was going down, I baptized six people in the Rio de la Plata, near the German electric plant here, the first in this generation in South America.”[51] The converts were all of German descent.[52] The next day, the missionaries confirmed those who were baptized, ordained two priests and a deacon, and administered the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper for the first time.[53]

Soon they visited the mayor of Buenos Aires, with whom they were able to communicate effectively because of Pratt’s considerable fluency in Spanish. The mayor guaranteed them complete religious liberty and said the government would not interfere in their work.[54]

Dedicating the Land for Preaching the Gospel

Finally, early on Christmas morning 1925, the missionaries visited a park to dedicate the continent of South America for missionary work. They sang hymns, read scriptures, and then knelt under a weeping willow as Ballard offered a dedicatory prayer.[55] He expressed gratitude for being chosen “to come to this great land of South America, to unlock the door for the preaching of the gospel to all the peoples of the South American nations, and to search out the blood of Israel that has been sifted among the Gentile nations, many of whom, influenced by the spirit of gathering, have assembled in this land.”[56]

The prayer was lengthy, in part expressing gratitude, in part imploring further blessings. “We thank thee,” he said, “for the few who have received us and for those we have had the joy of taking into the waters of baptism in this land. May they be the first fruits of a glorious harvest.”[57]

Two days after the dedication, the missionaries began holding meetings in Spanish, a portent of the harvest they expected to achieve among the native Spanish-speaking population.[58]

These early successes and the hope they inspired for continued success did not mean the way was easy for the missionaries. Sadly, Wells became dizzy to the point of incapacitation the day they arrived in Buenos Aires, and on January 14, 1926, he returned home with what turned out to be hemorrhaging in the brain. That left Ballard and Pratt without the translator they had brought to communicate with the German Church members.[59]

The Acorn-to-Oak-Tree Prophecy

After several more months of struggles and some successes, Ballard and Pratt finally returned to the United States in July 1926, but not before Ballard uttered what later Latter-day Saints looked upon as a noteworthy prophecy. During his last meeting in Buenos Aires that month, Ballard spoke of the future of the Church in South America. “The work will go forth slowly for a time,” he predicted, “just as the oak grows slowly from an acorn. It will not shoot up in a day as does the sunflower that grows quickly and thus dies. Thousands will join here. It will be divided into more than one mission and will be one of the strongest in the Church. The work here is the smallest that it will ever be. The day will come when the Lamanites here in South America will get the chance. The South American Mission will become a power in the Church.”[60]

The 1925–26 visit to South America of Melvin J. Ballard, Rulon S. Wells, and Rey L. Pratt took on even greater significance in the years to come. Frederick Salem Williams, who was born in one of the Latter-day Saint colonies in Mexico, heard Elder Ballard speak a few months after his return to the United States and, deciding to follow in his footsteps, requested to go to South America. Williams became a missionary in Argentina in 1927 and president of the Argentine Mission in 1938.[61] Williams noted that when he served in South America, “the members and investigators I knew always spoke of him [Elder Ballard] in reverent tones. Many of them would show me their right hands and say, ‘I shook hands with Apostle Ballard with this hand!’”[62]

The Church grew much as Elder Ballard had predicted, eventually being divided into Brazilian and Argentine missions. Elder Ballard’s visit to South America as a senior Latter-day Saint leader was not followed by another such visit until J. Reuben Clark, former US ambassador to Mexico and newly called second counselor in the First Presidency, traveled to South America late in 1933 at the behest of US president Franklin D. Roosevelt to attend the International Conference of American States in Uruguay. Clark also visited briefly with the Church’s members in a stopover in Buenos Aires on January 2, 1934.[63]

Opening the Way for Another Apostolic Visit

Knowing how important it was for the South American Saints to receive an extended visit from an eminent Church leader, Williams wrote to the First Presidency in 1941 to recommend an extended visit from one of the Church’s General Authorities:

President Bowers of the Brazilian Mission and I feel that it would be of immense worth to us if one of the Authorities could come and visit us. Then the Church would know at firsthand what our problems are. Then too, the visit would be a great stimulation to the missionaries and to the saints. There are hundreds of saints who are eagerly looking forward to the time when they can meet one of the Authorities. It is true that we have been visited by Brother Ballard, President Clark and Wells, but this was a long time ago. There are less than twenty saints that knew Brother Ballard, and perhaps about fifty that were fortunate enough to hear President Clark. Since then our mission has changed as from day to night.

Williams went on to list other challenges in the mission and then pleaded:

I realize how busy you all are and that the time involved is great, but if the airlines were used one can be in Buenos Aires from Salt Lake City in less than a week’s time. And between the Brazilian and the Argentine Missions I feel a great work could be accomplished by said visit. But I would ask that at least a month be spent in Argentina so that one could become thoroughly conversant with the conditions and the wonderful promises for the future.[64]

Later that month, the First Presidency replied in a letter that expressed sympathy for the mission’s challenges but also a desire to balance Williams’s wishes with the Church’s resource restraints:

Your first suggestion is that one of the General Authorities visit you and the Brazilian Mission at the earliest opportunity. We know from the results of other missions that official visits by members of the First Presidency or of the Council of the Twelve to the Missions result in a great deal of good. Direct observation is far more enlightening than information obtained by correspondence, especially is this true when conditions in the Mission are more or less unfamiliar. At present, however, the prospects of such a visit to South America are somewhat remote.[65]

Besides seeking a visit from a senior Church leader, Williams had requested an automobile to help in traveling over the immense area of the mission and permission to establish a printing operation for publishing Church literature in Spanish. The leaders granted his request for the car and would look further into the need for published literature.[66]

“I got the car; one out of three isn’t bad,” Williams later quipped.[67] He remained convinced, however, that a General Authority visit and a printing operation were also important, and over time both became realities.

The US entry into World War II following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, three months after Williams made his request, not only postponed any visit from a senior Church leader but also led to a reduction in the number of Latter-day Saint missionaries in Argentina.[68] During the war, after concluding his term as president of the Argentine Mission, Williams worked under the US State Department in Washington, DC, and then for the Institute of Inter-American Affairs in Venezuela and later in Uruguay. After the war, he returned to the United States to work in California.[69]

In August 1946 Williams went with family members to Utah to attend a wedding. He took advantage of his time there to hold a reunion with some of the missionaries who served with him in Argentina. Williams later recalled what happened at the reunion:

After reliving our experiences in South America and reaffirming our commitment to and love for the people, we began wondering why the Church wasn’t expanding into new South American countries. At that time only the Argentine and Brazilian missions existed. It seemed to us that Europe and the United States had received far more attention over the past twenty years. After some discussion we came to the conclusion that we should do something about it, for no one was in a better position to bring the matter to the attention of the Brethren. We felt we could point out to them in a forceful yet loving manner the tremendous proselyting opportunities existing to the south.[70]

One of the former Argentine missionaries who engaged with Williams in this discussion was Don Smith, nephew of George Albert Smith, who at the time was the Church’s President. Don Smith phoned his uncle and set up a meeting with him and the former missionaries the next morning. Williams, the designated speaker for the group, started by saying the missionaries felt that “because no General Authorities had ever lived in South America, with the exception of those who opened the work there under Elder Melvin J. Ballard (who died in 1939), [the group] felt perhaps [Church leaders] were not sufficiently acquainted with the conditions.”[71] Williams also justified the need for this meeting by recounting the dearth of Church leader visits to South America:

I pointed out that Elder Ballard had opened the South American Mission in 1925, some twenty-one years before. Since then, the only General Authority to visit had been President J. Reuben Clark, Jr., of the First Presidency; he had been there less than a week to represent the United States Government in Uruguay and had visited with the Saints in Buenos Aires for only a matter of hours.[72]

As Williams went on recounting the history and condition of the Church in South America, George Albert Smith sat quietly, neither commenting nor asking questions. At the end of Williams’s presentation, which lasted about an hour, the President excused himself without comment and left.

“Because he had made no observations we felt that we had displeased him and began thinking to ourselves, ‘Well, it was wonderful being a member of the Church while it lasted,’” Williams recalled. President Smith surprised them, however, by returning with David O. McKay, his second counselor, who had a well-deserved reputation of being among the most traveled of all Church leaders at the time, a man whose tenure included visits to many countries.[73]

“I asked David to leave the meeting he was attending and come back with me,” Smith explained. “Please repeat to him what you have told me, President Williams.”

Williams rehearsed what he had already said and added a few further ideas. When he finished talking, a long period of silence ensued. “Our hearts fell” once again, Williams recalled.

Finally, Smith turned to his counselor and asked, “David, what do you think of all this?”

“I’m impressed with it,” McKay replied. “I’m happy they came and brought it to our attention; I think we should do something about it.”

“I do too,” Smith concurred.

The two senior Church leaders thanked their visitors and told them to reduce their thoughts to paper. The former Argentine missionaries agreed to do so and left ebullient.

“We felt we were walking on air,” Williams recorded.[74]

As spokesperson for the group, Williams wrote the requested report to the First Presidency. In it he related the history and conditions of each country of interest and recommended an order in which the Church should enter the nations, with Uruguay leading the list. “I also respectfully recommended that someone, preferably a General Authority, be called to live in South America to supervise and coordinate the activity of the various missions after they were established,” Williams wrote in a letter that accompanied the report.[75]

The letter and report, which Williams forwarded to the First Presidency on September 28, 1946, after he returned to California, ran several pages. “It is lamentable that it is so voluminous,” Williams apologized, “but to show a complete picture it was felt necessary to present one this length.” Williams expressed his love and support of his church leaders and wrote that “in no sense of the word is there any criticism impl[i]ed.” Instead, he and his fellow returned missionaries offered their help “because,” he wrote, “we feel we are more familiar with conditions and peoples of Central and South America” than others.[76]

The report began with a background section that emphasized the importance of Latin America. It listed the total population of the area and the major language groups, particularly Spanish. “The Spanish language,” the report explained, “is spoken by more Christians, with the exception of English, than any other language in the world today.”[77]

“The peoples of Latin America have much in common with the inhabitants of the United States,” it pointed out. For example, people in both areas “are living in choice lands, they are living in Zion”—a reference to the Latter-day Saint belief that God would establish his people in this region. The report noted that like many people in the United States, many in Latin America descended from European roots. As for native Indian peoples, believed by the Saints to be descendants of Book of Mormon peoples,[78] the report posited, “we feel that the day of redemption for the Lamanite people will only come as fast as we are prepared to make it come about.”[79]

“We feel we should devote time and energy to prepare ourselves to rede[e]m these people,” Williams wrote on behalf of the returned missionaries. “To begin the work among the Indians does not necessarily mean going into the mountains and devoting all of our time to the pure races,” many of whom spoke neither Spanish nor English. Instead, he suggested, work could begin “among the inhabitants of the Central and South American republics,” many of whom were mixed “descendants of the Indians and also . . . some of the best blood of Europe that has immigrated to America.” Over time, “our activities can fan out to embrace all of the Indian people.”[80]

The report then went on to divide the countries according to where missionary work should begin. It recommended not starting in “Bolivia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Venezuela, and the three Guianas,” giving reasons ranging from illiteracy and “low moral standards” to malaria. In this period more than three decades before the landmark 1978 revelation on priesthood that opened priesthood ordination and temple blessings to all Latter-day Saint men regardless of race, a key factor in why Williams and his companions sought to avoid some areas was “the great mixture” with people of African heritage.”[81] Gratefully, in the 1970s the faithfulness of black Saints in South America would be a catalyst in the pondering that led to the 1978 revelation.[82]

Given Williams’s experience in Uruguay, it was no surprise that he recommended that country as a place to start a mission. The report called Uruguay “the most democratic country and the most pleasant one in which to live in South America.”[83]

In his cover letter, Williams wrote, “Our only wish and hope is to further the missionary work and to ask the Church to look Southward toward the great opportunities there awaiting our efforts.”[84]

Persistence Pays Off

Williams had high hopes the report would lead to action. “I sent the document off,” he later wrote, “but never heard of it again.”[85] Yet the letter did have an effect on Church leaders. In April 1947, about eight months after the missionaries met with George Albert Smith and David O. McKay, Williams received a telegram asking him to phone McKay the next morning.

When he did so, McKay asked, “Do you remember recommending opening a mission in Uruguay?”

Williams acknowledged that he did.

McKay responded, “How would you like to go down and open it?”[86]

By the end of August 1947, Williams had arrived in Uruguay to do just that.[87] But before he left for South America, he renewed his request for a high-ranking Church leader to tour the missions on that continent. “While in Salt Lake City preparing to leave for Uruguay to open the mission,” he remembered, “I took occasion to invite the Brethren to visit the South American missions, so that they might know the conditions first hand.” McKay, whose son served under Williams in the Argentine Mission, responded, “It would be wonderful if one could be spared; we’ll see what can be done.”[88]

After Williams arrived in Uruguay, he renewed the invitation in a letter to McKay, repeating the benefits that would follow from such a visit. McKay answered Williams’s letter cordially, saying such a tour “would be most delightful” to him and “very informative.” He noted that his son and other former missionaries to South America had been urging him to take such a trip. “Of this I am convinced,” McKay concluded, “that one of the Presidency should visit these missions in the very near future. We should then be in a position to render clearer judgment regarding the matters that come before us from time to time.”

By “near future,” however, McKay did not mean very soon. He told Williams, “We have the matter under consideration, but prospects for a visit this year are very dim.”[89]

Undeterred, Williams wrote a long letter to Spencer W. Kimball, then serving in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, the second tier of Church leadership, but who would later become President of the Church, a world traveler, and the prophet who announced the 1978 revelation on priesthood that helped overcome barriers to the Church’s expansion in Latin America and elsewhere. Williams predicted that the “future missionary field is in South America” and expressed his hope that a senior Church leader would visit. “What the South American missions need more than anything else is the visit of one or more of the General Authorities,” Williams asserted. “Won’t you please come and see?”[90]

Stephen L Richards Appointed for South American Missions Tour

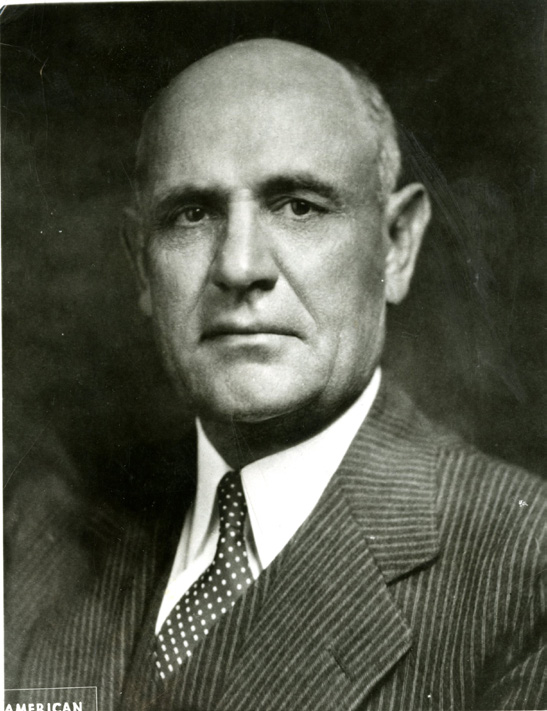

Stephen L Richards's official photo that was given to the press to use in news articles throughout South America. Courtesy of Church History Library (hereafter “CHL”).

Stephen L Richards's official photo that was given to the press to use in news articles throughout South America. Courtesy of Church History Library (hereafter “CHL”).

Finally, after years of pleading, Williams received the hoped-for reply. On December 10, 1947, Stephen L Richards of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles wrote him a letter explaining that the First Presidency had appointed him “to visit the South American missions” with his wife, Irene Smith Merrill Richards.[91] Elder Richards was one of the most respected of all Church leaders in his day. Born in 1879 in Mendon, Utah, to parents with prominent Latter-day Saint pioneer ancestry, Stephen grew up imbued with the culture and doctrine of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and a love of the outdoors, sports, and recreation.[92] Also being a man of the mind, he attended the University of Utah, where he excelled in debate, drama, and literature. Science courses favoring evolution over creationism shook his “pre-conceived ideas” of religion, and “for a period of time,” he later said, “I suffered from doubt and uncertainty.” Unsure how to handle his doubts in a culture of belief, Stephen kept them to himself.[93]

Irene Smith Merrill was born in 1876 in Fillmore, Utah. Like Stephen, she was descended from notable Latter-day Saint ancestors. Stephen’s senior in age by three years, Irene shared his interest in literature and drama. When they fell in love and Stephen asked her to marry him, she agreed, provided they could marry in a Latter-day Saint temple.[94] This condition brought to the forefront Stephen’s simmering spiritual doubts. In Latter-day Saint culture, only devout members are permitted to marry in the temple. A man of integrity, Stephen would not feign belief in order to marry Irene. “He was a student at the U[niversity] of U[tah] and didn’t really know what he believed,” Irene recalled, and “so he began to study, debate, consider, and pray.”[95]

Stephen talked with family members and friends about his doubts. But in the end, he turned to God to resolve his problems. “I finally decided I would appeal to a higher source of wisdom in the solution of my difficulties,” he later explained. In the process, filled with what Irene called “real desire,” Stephen “finally decided that he really knew that the Gospel was true.”[96]

“My approach was very humble and I suppose many would say very naive,” he later acknowledged. Yet Irene noted in her journal, “The richness of his study and convictions gave him a marvelous foundation for his whole life’s work and accomplishments.” “Never since then,” he wrote of his conversion, “have I experienced any doubt as to the reality of spiritual forces nor have I had difficulty in correlating all that I have been able to learn with spiritual philosophy in my life.”[97]

Stephen and Irene married and began their life together, a life that over the course of decades focused on family, community, church, and recreation. They sacrificed so Stephen could begin a graduate program in law at the University of Michigan and complete it at the University of Chicago in the first graduating class of that law school. In time he became successful in law, business, and politics. He also served on the law faculty of the University of Utah. His successful career, coupled with Church service at both the local and general levels, led to a call to serve as an Apostle of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1917 at age thirty-seven.[98]

Elder Richards threw himself into his new calling with the same energy that characterized much of the rest of his life. Although his heavy duties kept him away from home much of the time, he and Irene continued to grow together as they raised their family and enjoyed vacations that took them outdoors. One of the heaviest responsibilities he bore was service on the Church Missionary Committee. It was this assignment that made him a natural choice to tour the missions of South America in 1948.

Irene looked at the trip as an adventure that would put her literary skills to work. “Papa will do all the work,” she wrote in a letter to her children, “and I’ll look at the scenery and do the writing.”[99] Although Elder Richards would receive most of the attention on the trip, Irene’s writing would preserve their historic journey for future readers. Indeed, she was the one who, over time, kept the most complete and interesting record of their lives.

Overjoyed to learn that the Richardses were coming to visit, mission president Frederick S. Williams wrote a two-page letter of gratitude and travel tips for them, expressing thanks “that after twenty years of waiting, the South American Saints ‘would have the privilege of hearing an Apostle of the Lord.’”[100]

Notes

[1] . See Dean C. Jessee, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, eds., Journals, Volume 1: 1832–1839, vol. 1 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2008), xxiii; James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 56. The restored Church of Christ was formally named The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1838; see Doctrine and Covenants 115:4.

[2] . See Solomon Chamberlain autobiography, 9–11, CHL; John Taylor Journal, 50–54, CHL; Larry C. Porter, “The Book of Mormon: Historical Setting for Its Translation and Publication,” in Joseph Smith: The Prophet, the Man, ed. Susan Easton Black and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1993), 58–59.

[3] . See Chamberlain autobiography, 9–11; Porter, “Book of Mormon,” 58–59; “The First Book of Nephi,” Palmyra (NY) Reflector, January 2, 13, 1830, CHL; Richard E. Turley Jr. and William W. Slaughter, How We Got the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 32; Russell R. Rich, “The Dogberry Papers and the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies 10, no. 3 (Spring 1970): 315–20.

[4] . The Book of Mormon (Palmyra, NY: E. B. Grandin, 1830).

[5] . See The Life of Brigham Young (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon and Sons, 1893), 14; Leonard J. Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985), 19; Richard E. Turley Jr. and Brittany A. Chapman, eds., Women of Faith in the Latter Days (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 1:130n3.

[6] . See Steven C. Harper, “The Restoration of Mormonism to Erie County, Pennsylvania,” Mormon Historical Studies 1, no. 1 (Spring 2000): 4–5; Richard Price and Pamela Price, “Missionary Successes, 1836–1844,” Restoration Voice 26, no. 14 (November/

[7] . See Doctrine and Covenants 28:8; Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 122.

[8] . See Terryl L. Givens and Matthew J. Grow, Parley P. Pratt: The Apostle Paul of Mormonism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 5–8.

[9] . Doctrine and Covenants 32:2.

[10] . See Autobiography of Parley Parker Pratt, ed. Parley P. Pratt Jr. (New York: Russell Brothers, 1874), 54–55; Givens and Grow, Parley P. Pratt, 45–46.

[11] . See Givens and Grow, Parley P. Pratt, 37–39, 46–47.

[12] . See Givens and Grow, Parley P. Pratt, 290, 306–12; A. Delbert Palmer and Mark L. Grover, “Hoping to Establish a Presence: Parley P. Pratt’s 1851 Mission to Chile,” BYU Studies 38, no. 4 (1999): 115–28; Frederick S. Williams and Frederick G. Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree: A Personal History of the Establishment and First Quarter Century Development of the South American Missions (Fullerton, CA: Et Cetera, Et Cetera Graphics, 1987), 1.

[13] . See David J. Whittaker, “The Bone in the Throat: Orson Pratt and the Public Announcement of Plural Marriage,” Western Historical Quarterly 18, no. 3 (July 1987): 293–314; Deseret News Extra, September 14, 1852, Mormon Publications: 19th and 20th Centuries, Harold B. Lee Library Digital Collections, Brigham Young University.

[14] . See George A. Smith, The Rise, Progress and Travels of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1872), 36.

[15] . See Aaron F. Farr to George A. Smith, June 2, 1865, Correspondence, Missionary Reports, 1831–1900, CHL. The missionaries to Jamaica were Aaron Farr, Jesse Turpin, Darwin Richardson, and Alfred B. Lambson.

[16] . Smith, Rise, Progress and Travels, 36.

[17] . See Parley P. Pratt to Brigham Young, March 13, 1852, Incoming Correspondence, Brigham Young Office Files, CHL; reprinted in Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt, ed. Parley P. Pratt Jr., 4th ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1985), 367–68; Palmer and Grover, “Hoping to Establish a Presence,” 129; Givens and Grow, Parley P. Pratt, 382–84.

[18] . See Orson F. Whitney, History of Utah (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon and Sons, 1904), 4:508.

[19] . See The Wasp 1, no. 1 (April 16, 1842): 3; no. 6 (May 21, 1842): 23; no. 12 (July 2, 1842): 45; no. 36 (January 7, 1842 [1843]): 141.

[20] . See Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Administrative Records: Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 17, 47–48, 140–42.

[21] . El Siglo Diez y Nueve, July 27, 1844, in private possession of Fernando Gomez; copy located at Museum of Mexican Mormon History.

[22] . According to Fernando Gomez, “the official newspaper of the Mexican Government called Diario Oficial del Supremo Gobierno as early as the 1850s printed articles from The Herald of New York,” which included content about Latter-day Saints. Fernando R. Gomez and Sergio Pagaza Castillo, Benito Juarez and the Mormon Connection of the 19th Century (Mexico City: Museo de Historia del Mormonismo en México, 2007), 10, 27n56.

[23] . See John G. Turner, Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2012), 123, 170; Allen and Leonard, Story of the Latter-day Saints, 257–58; Arrington, Brigham Young, 146–47.

[24] . See Turner, Brigham Young, 174; Tom Gray, “The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo,” National Archives, updated April 25, 2018 https://

[25] . See William P. MacKinnon, “‘Not as a Stranger’: A Presbyterian Afoot in the Mormon Past,” Journal of Mormon History 38, no. 2 (Spring 2012): 26–33.

[26] . Arrington, Brigham Young, 265–66. See also “The Utah Expedition: Its Causes and Consequences,” part 3, Atlantic Monthly, May 1859, 583–84.

[27] . See Norman F. Furniss, The Mormon Conflict, 1850–1859 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1960), 168–76; Will Bagley, ed., Kingdom in the West: The Mormons and the American Frontier, vol. 10 of At Sword’s Point, Part I: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858, ed. William P. MacKinnon (Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark, 2008), 479–81; LeRoy R. Hafen and Ann W. Hafen, eds., The Utah Expedition, 1857–1858 (Glendale, CA: Arthur H. Clark, 1958), 327–28; Allen and Leonard, Story of the Latter-day Saints, 315–17.

[28] . See Eugene E. Campbell, Establishing Zion: The Mormon Church in the American West, 1847–1869 (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1988), 246–48; John D. Lee to Emma B. Lee, December 9, 1876, HM 31214, John D. Lee Collection, Huntington Library, San Marino, CA.

[29] . See Donald Levi Gale Hammon, Levi Byram and Martha Jane Belnap Hammon: Gold Medal Pioneers (Chapel Hill, NC: Professional Press, 1996), 59–60; Kevin H. Folkman, “‘The Moste Desert Lukking Plase I Ever Saw, Amen!’ The ‘Failed’ 1873 Arizona Mission to the Little Colorado River,” Journal of Mormon History 37, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 115–50.

[30] . See Daniel W. Jones, Forty Years among the Indians (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office, 1890), 219–332; Helaman Pratt Journal, 1875–78, CHL; Anthony Woodward Ivins Diary, Anthony W. Ivins Collection, CHL.

[31] . Brigham Young to Wm. C. Staines, January 11, 1876, letterpress copybook, 14:125–26, Brigham Young Office Files, CHL.

[32] . See F. LaMond Tullis, Mormons in Mexico: The Dynamics of Faith and Culture (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1987); Thomas Cottam Romney, The Mormon Colonies in Mexico (1938; repr., Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005); LaVon Brown Whetten, Colonia Juarez: Commemorating 125 Years of the Mormon Colonies in Mexico (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2010).

[33] . See Tullis, Mormons in Mexico; Romney, Mormon Colonies in Mexico; Whetten, Colonia Juarez.

[34] . See Andrew Jenson, comp., Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jenson Memorial Association, 1901–36), 4:348; Dale F. Beecher, “Rey L. Pratt and the Mexican Mission,” BYU Studies 15, no. 3 (1975): 293–307.

[35] . See Jason Swensen, “Mexican Colonies Offering Fruits of Leadership,” Church News, May 11, 2001.

[36] . See Autobiography of Andrew Jenson (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1938), 547; Justin R. Bray and Reid L. Neilson, Exploring Book of Mormon Lands: The 1923 Latin American Travel Writings of Mormon Historian Andrew Jenson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2014), 1–26.

[37] . See Bray and Neilson, Exploring Book of Mormon Lands, 21–24, 31n10.

[38] . Bray and Neilson, Exploring Book of Mormon Lands, 291.

[39] . Bray and Neilson, Exploring Book of Mormon Lands, 291.

[40] . Bray and Neilson, Exploring Book of Mormon Lands, 291.

[41] . Bray and Neilson, Exploring Book of Mormon Lands, 292.

[42] . See Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 18–20.

[43] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 20.

[44] . Bryant S. Hinckley, Sermons and Missionary Services of Melvin Joseph Ballard (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1949), 89; Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 20–21. On the role of the Quorum of the Twelve in opening missions, see Record of the Twelve, February 14, 1835, CHL; also available at the Joseph Smith Papers, https://

[45] . See Melvin R. Ballard, Melvin J. Ballard—Crusader for Righteousness (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1966), 54–57.

[46] . See Ballard, Crusader for Righteousness, 54–57, 75–76; Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:419–20.

[47] . See Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:212–14.

[48] . See Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:348; Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan, eds., Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 942–43.

[49] . Hinckley, Sermons, 92. Elder Ballard’s original journals were lost after his death. Bryant Hinckley had access to it, and so excerpts appear in his book.

[50] . See Hinckley, Sermons, 91–93.

[51] . See Hinckley, Sermons, 94.

[52] . To better understand Latter-day Saint German migration to South America, see Mark L. Grover, “The Mormon Church and German Immigrants in Southern Brazil: Religion and Language,” Jahrbuch für Geschichte von Staat, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft: Lateinamerikas (1989), 26:302–5.

[53] . See Hinckley, Sermons, 94.

[54] . See Hinckley, Sermons, 94.

[55] . See Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 23–25.

[56] . Hinckley, Sermons, 94–95.

[57] . Hinckley, Sermons, 95.

[58] . See Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 25.

[59] . See Hinckley, Sermons, 93; Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 25.

[60] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 30.

[61] . See Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 3, 79; obituary of Frederick Salem Williams, Deseret News, October 10, 1991.

[62] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 30.

[63] . See The Diaries of J. Reuben Clark, 1933–1961, Abridged (Salt Lake City: privately printed, 2010), 8–10; Frederick S. Williams to the First Presidency, September 1, 1941, in Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 187. See also Buenos Aires Branch, January 2, 1934, in South American Mission Manuscript History and Historical Reports, vol. 2, Branch Histories, 1925–1935, CHL.

[64] . Williams to the First Presidency, September 1, 1941, 187–89.

[65] . First Presidency [Heber J. Grant, J. Reuben Clark Jr., and David O. McKay] to Frederick S. Williams, September 17, 1941, in Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 191.

[66] . First Presidency to Frederick S. Williams, September 17, 1941.

[67] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 191.

[68] . See Mark L. Grover, “Argentina: Building the Church One Bloque at a Time,” in A Land of Promise and Prophecy: Elder A. Theodore Tuttle in South America, 1960–1965 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), 186–231; Frederick S. Williams Oral History, interviewed by William G. Hartley, 1972, 25–33, CHL.

[69] . See Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 195.

[70] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 201.

[71] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 201.

[72] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 201.

[73] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 201–2; Hugh J. Cannon, To the Peripheries of Mormondom: The Apostolic Around-the-World Journey of David O. McKay, 1920–1921, ed. Reid L. Neilson (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2011).

[74] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 202; Keith McCune to the First Presidency, November 30, 2005, in Frederick S. Williams et al., “Proposed Plan for Activating and Extending the Missionary Work in Latin America,” September 28, 1946, CHL. The last page of the report states that returned missionaries J. Vernon Graves, Robert R. McKay, Don Hyrum Smith, Edgar B. Mitchell, and Keith N. McCune assisted Williams with the report.

[75] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 202–3.

[76] . Frederick S. Williams to the First Presidency, September 28, 1946, in Williams et al., “Proposed Plan,” 1.

[77] . Williams et al., “Proposed Plan,” 3.

[78] . For a geneticist’s discussion of the complications inherent in attempts to reconstruct the genetic structure of ancient Native American populations, see Ugo A. Perego, “The Book of Mormon and the Origin of Native Americans from a Maternally Inherited DNA Standpoint,” in No Weapon Shall Prosper: New Light on Sensitive Issues, ed. Robert L. Millet (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011), 171–217.

[79] . Williams et al., “Proposed Plan,” 3.

[80] . Williams et al., “Proposed Plan,” 3.

[81] . Williams et al., “Proposed Plan,” 4.

[82] . See Edward L. Kimball, “Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood,” BYU Studies 47, no. 2 (2008): 5–78; Jeremy Talmage and Clinton D. Christensen, “Black, White, or Brown? Racial Perceptions and the Priesthood Policy in Latin America,” Journal of Mormon History 44, no. 1 (January 2018): 119–45; Mark L. Grover, “The Mormon Priesthood Revelation and the São Paulo, Brazil Temple,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 23, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 42–44.

[83] . Williams et al., “Proposed Plan,” 5.

[84] . Williams to First Presidency, September 28, 1946.

[85] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 203. Decades after Williams and his fellow missionaries submitted their report, one of the missionaries wrote to a later First Presidency: “It is of interest that our recommendations were adopted by the brethren, pretty much as presented, over the following years.” Keith McCune to the First Presidency, November 30, 2005.

[86] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 203.

[87] . See Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 219.

[88] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 237.

[89] . David O. McKay to Frederick S. Williams, October 28, 1947, Stephen L Richards Papers; Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 238.

[90] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 238; Kimball, “Revelation on Priesthood.”

[91] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 238–39; Stephen L Richards to Frederick S. Williams, December 10, 1947, Frederick S. Williams Papers, CHL.

[92] . See W. Dee Halverson, Stephen L Richards, 1879–1959 (n.p.: Heritage Press, n.d.), 1–34.

[93] . See Halverson, Stephen L Richards, 34–40.

[94] . See Halverson, Stephen L Richards, 39, 42–53.

[95] . Halverson, Stephen L Richards, 39.

[96] . Halverson, Stephen L Richards, 39, 40.

[97] . Halverson, Stephen L Richards, 40.

[98] . See Halverson, Stephen L Richards, 55–116.

[99] . Halverson, Stephen L Richards, 141.

[100] . Williams and Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree, 238–39.