"Who Can Ever Surpass These inexpressible Heights?"

Ludwig van Beethoven

Richard E. Bennett, “'Who Can Ever Surpass These Inexpressible Heights?': Ludwig van Beethoven,” in 1820: Dawning of the Restoration (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 81‒104.

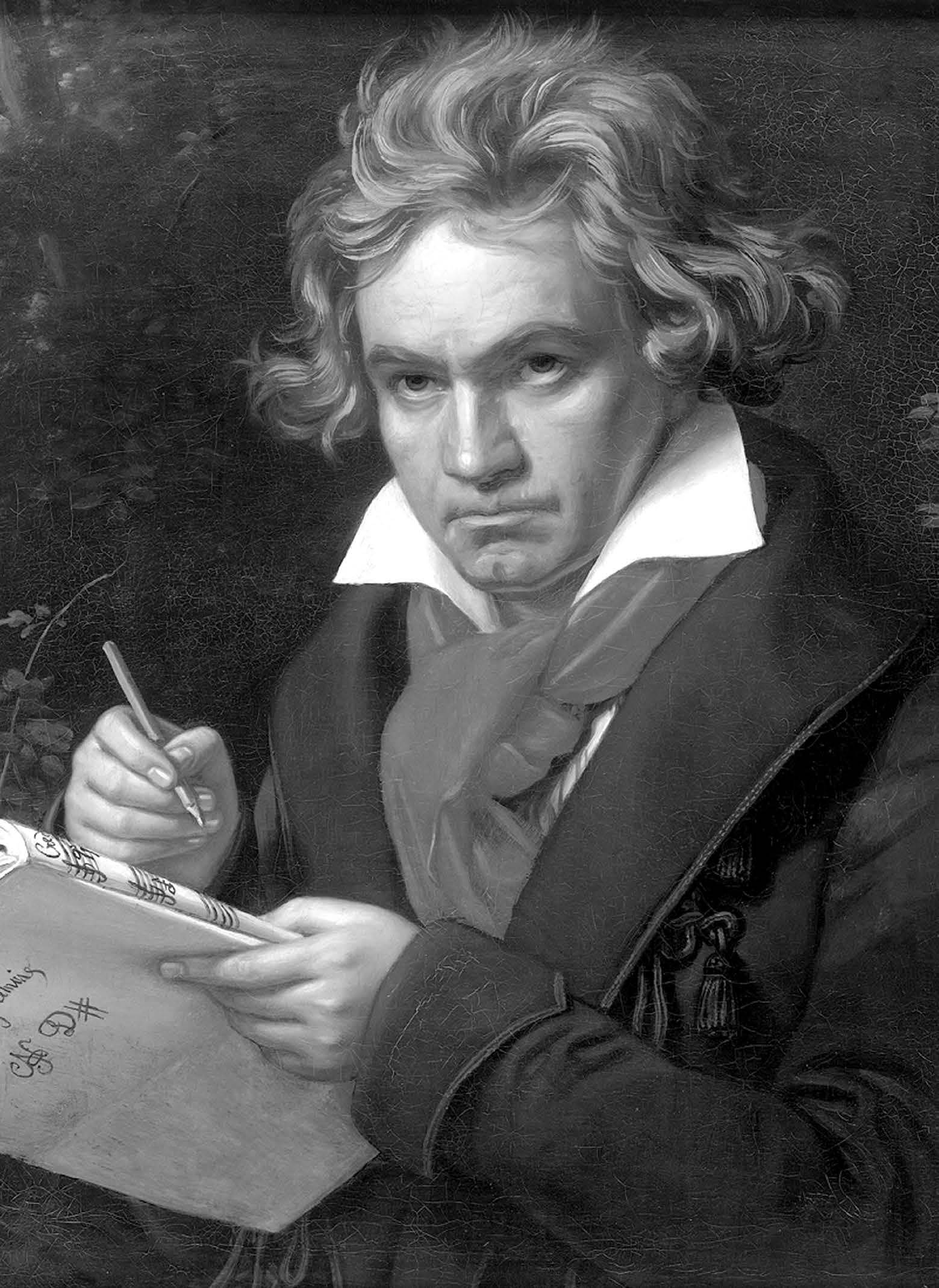

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven When Composing the Missa Solemnis, by Joseph Karl Stieler.

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven When Composing the Missa Solemnis, by Joseph Karl Stieler.

A hush of anxious, silent anticipation settled over the small, candlelit crowd that cold winter night of 25 January 1815. Seated in the center of the front row of the drawing room in royal evening attire was the beautiful Russian princess Elizaveta. She was accompanied by her attendants and a handpicked audience of Vienna’s finest and best. She had been waiting years for this magical moment. Suddenly he appeared, slipping through the curtains. All eyes strained to see; all ears yearned to listen, including those of Foreign minister Klemens von Metternich’s hated secret police. A short, stocky man with a large head, a pockmarked face, and ruddy complexion, Ludwig van Beethoven was smartly dressed in powder blue evening attire. His appearance belied which opposed his long-established reputation as a slovenly dresser, one who was as clumsy, awkward, and ill-tempered as the princess was elegant, poised, and good-natured. Rather than convey the impression that this was just another unwanted demand on his hectic schedule, the forty-five-year-old Beethoven filled the room with graciousness. After bowing before the audience and kissing the outstretched hand of the waiting empress, Beethoven sat down at the piano to his left and began to play.

As shown in the preceding chapter, the Congress of Vienna was as well known for its pageantry as it was for its politics. Concerts and symphonies, dances and balls, operas and plays lasted well into the night, and Vienna—the city of Haydn and of Mozart—would boast its finest. But its finest had been reluctant to come. Suffering from advanced deafness, acute colitis, and possibly cirrhosis of the liver, a sullen, reclusive, and overworked Beethoven was facing a pending physical breakdown. Persuaded to capitalize on the patriotic fervor of the time, if only to pay his mounting debts, Beethoven had hurriedly composed two rather bombastic pieces in line with his earlier nationalistic “Wellington Song,” “You Wise Founders of Happy Nations” and a cantata in praise of the Congress entitled “The Glorious Moment.” All three pieces were faint echoes to the greatness of his more established works. Of all the artists performing and conducting that Viennese winter, Beethoven was by far the one most in demand, yet he was the one least anxious to perform.

His stirring and majestic Seventh Symphony, completed just three years before and first performed in 1814, had already gained enormous popularity and renown across war-torn Europe as a stirring and majestic musical celebration of Napoléon’s Russian defeat. Many recent veterans wept publicly upon hearing it, so stirred were they by the force and power of Beethoven’s Seventh. Having dedicated the symphony to the empress—who in company with her husband, Tsar Alexander I, had become one of his most famous patrons and financial supporters—Beethoven accepted her invitation to perform, knowing full well it would not be his best showing. The tragedy was that he could not hear what he would now play.

Other than himself and his sternest critics, everyone in attendance, the empress included, thoroughly enjoyed the performance. Beethoven, however, knew it had fallen short of his accustomed best. Disgusted with himself, he was barely able to remain civil, and when his performance ended, he almost bolted from the room in a state of anger, depression, and frustration. He left as brusquely as he had entered graciously, determined never to play the piano in public again.

While the focus of this chapter will be Beethoven, the man and his works, some attention must inevitably be given to other musical geniuses of his time, many of whom knew and respected Beethoven as one of the most masterful composers of all time. Together, they made music that has endured since and that will continue to enthrall music lovers for centuries yet to come.

“I Had Some Talent for Music”: A Challenging Childhood, 1770–92

Ludwig van Beethoven’s childhood and adolescence have been a source of unending scholarly debate. Born 17 December 1770 into a musical family in the electorate of Cologne, Beethoven grew up in Bonn (West Germany). Of his mother, Maria Magdalena Leym (1746–87), he once said she was his “best friend” and his “kindest supporter, protector, and most affectionate influence.” Even though he later gained the friendship of the widow Frau von Breuning, the untimely death of his mother when he was sixteen years old devastated him and left a vacuum of affection no other person could fill.

On the other hand, his father, Johann van Beethoven (1740–92), a court tenor and music teacher who was in want of a decent education, never reached the towering expectations of his own father and kapellmeister and eventually turned to drink to drown his sorrows and failures. When enraged, he often belittled his promising young son, boxing him hard on the ears, berating him in public, and scolding him unmercifully. With his father so often away drinking or suffering from a hangover, young Ludwig, rather than run away, took care of his five younger siblings and did all he could to protect them from the wrath of their tyrant father, whom Beethoven also eventually took care of. Feeling abandoned, unwanted, and unloved by his father but resigned to live out the storm, Beethoven became the protector and guardian of his own brothers and—in time—f his own disconsolate father. A virtual orphan in his own home, Beethoven learned early the solace of isolation and loneliness; what it meant to live in an unkempt, disorganized, and unclean home; and the pain and sorrow of broken family relationships. At the same time, he drew strength from the inner music of his soul, a veritable musical balm of Gilead. As one of his best biographers phrased it, “He seems to have found sustenance in inwardness.”[1]

The young Beethoven chose to emulate his musically talented grandfather, also named Ludwig van Beethoven (1712–73), even though his grandfather had died when Beethoven was but three years of age. Beethoven turned first to the piano and organ and later to the violin and the viola as his most trusted friends. Despite his father’s discouragement, he began to compose early in his life. A virtuoso at playing the piano, Beethoven was driven towards originality as if to express the yearnings of a tormented soul. He was so proficient, through long hours of daily practice that often lasted past midnight, that he became a deputy court organist when merely fourteen years of age.

Never the best of students in a formal classroom setting and “sadly deficient” in spelling, grammar, and arithmetic,[2] Beethoven “took from the legacy of his elders only what made sense to him in terms of his own inner experience.”[3] He learned best from one-on-one instruction. Fortunately, during this dark and formative time of his life, the eleven-year-old Beethoven fell under the influence of a wise tutor. Just as Tsar Alexander I had developed and matured under Frédéric La Harpe, Beethoven stood to gain much from Christian Gottlob Neefe (1748–98), a composer, organist, and conductor with rigorous standards of performance. Neefe recognized at once the genius in his young student’s talent and encouraged him to compose and play sonatas and lieders (songs). Far more than a mere music teacher, Neefe also inculcated in Beethoven a philosophy of learning and of viewing the world; a love of great literature—especially of Shakespeare but also of Kant, Schiller, Rousseau, and Goethe; and an appreciation of the romanticist ideals of the European Enlightenment. Thus, from his adolescence, Beethoven developed a love of freedom, a hatred of tyranny, and a desire to reach for the divine in the human soul.

As Neefe taught Beethoven a love for the harmonies of Bach and the operatic magnificence of Mozart, he saw far more than a gifted musician. He saw one who, while emulating others, could also follow his own creative voice. As another biographer put it, Beethoven had an “inner, self-critical drive toward originality.”[4] Beethoven regarded Mozart, whom he likely met while visiting Vienna in 1787, “as his early musical god” and may well have studied under him had not Mozart died so tragically young in 1791.[5] Much in Beethoven’s finest musical compositions would hearken back to both Mozart and Bach.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart,

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart,

c. 1780, by Johann Nepomuk della Croce. Courtesy of Encyclopædia Britannica.

By the age of fourteen, Beethoven had already written three quartets for piano and strings and a large number of lieders, including the so-called “Dressler Variations.”[6] These early Bonn compositions, though not emotionally powerful, showed many of those elements that would go on to characterize his music: dynamic contrasts, abrupt pianissimos and fortissimos, broad rhythms, eight-measure groupings, and an overriding “absolute” or overarching melody that entwined itself throughout the work.[7] William Kinderman, a musician and scholar, argues that from Beethoven’s earliest compositions in Bonn, there is a “progressive unification” in all his works and that his earlier works “were eventually absorbed into the mainstream of his creative enterprise.”[8] Constantly writing down themes, patterns and melodies, Beethoven developed ideas early on for entire concertos and symphonies and could transform a very simple melody into a symphony.

In the era before the Congress of Vienna, Bonn was the central city of the electorate of Cologne, one of over three hundred German feudal territories, or kleinstaaten (ministates), and all part of the decaying Holy Roman Empire. Bonn, although a local center for culture and theater, never rivaled the cultural splendor of Vienna or even Berlin. Although he was financially supported by local royalty and aristocrats, most notably the elector Max Franz (Marie-Antoinette’s brother), Beethoven yearned to move on from Bonn. With the death of his father in 1792, he seized his opportunity and, at age twenty-two, accepted the invitation to study for at least a year under one of Vienna’s finest musicians—Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809). He would never return.

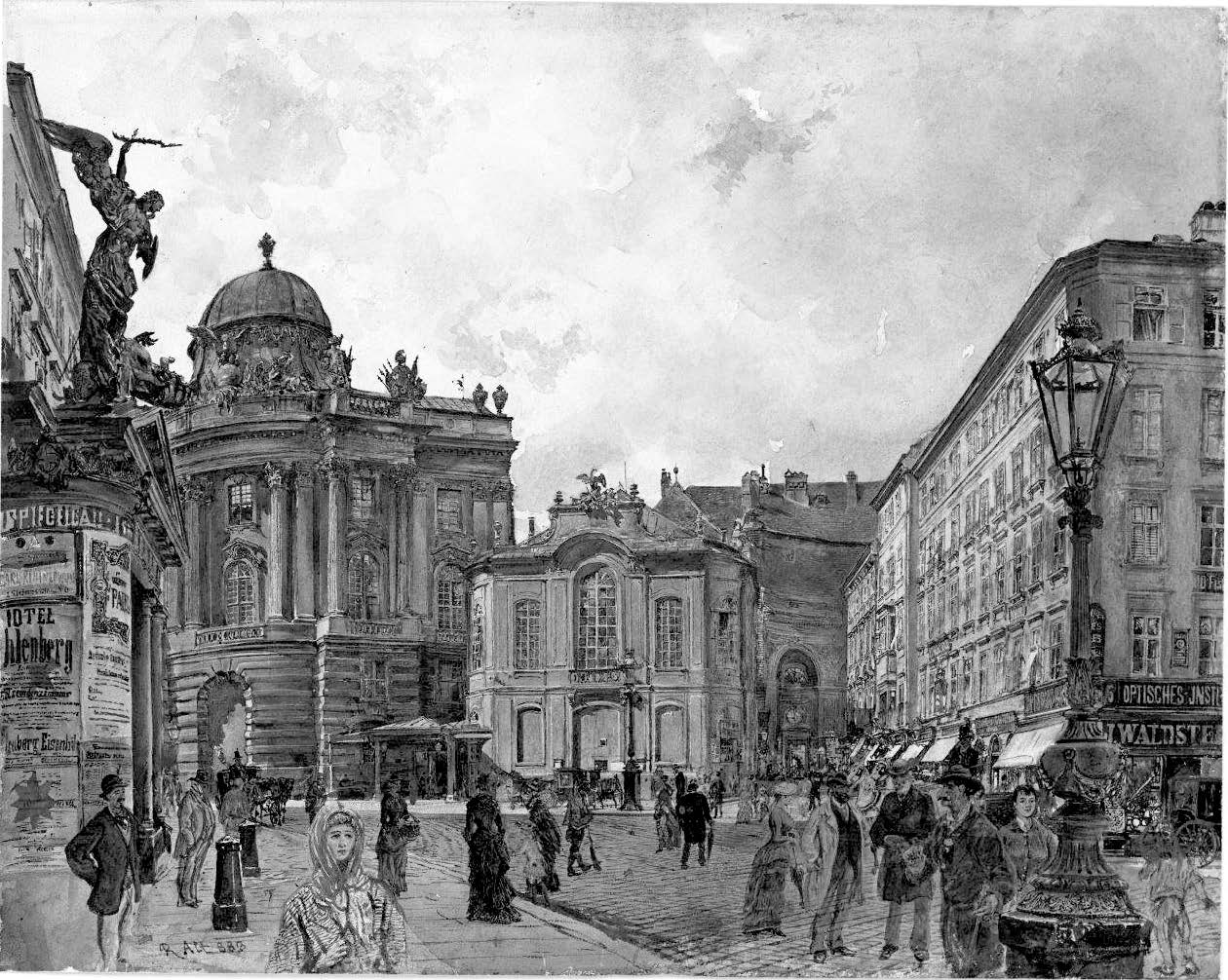

Vienna in the early nineteenth century. Wien, Michaelertor der Hofburg und altes Burgtheater, Aquarell (1888), by Rudolf von Alt.

Vienna in the early nineteenth century. Wien, Michaelertor der Hofburg und altes Burgtheater, Aquarell (1888), by Rudolf von Alt.

There was another, very practical and pressing reason for Beethoven’s move east to Vienna—the growing fear of Napoléon. Even at this early date, Prussian and Austrian royalties worried over the rising influence of the republican ideals of the French Revolution and of the reputation of its militant son, Napoléon. Were Napoléon to advance eastward to Berlin, Bonn stood squarely in his path. Beethoven would develop a love-hate attitude toward the French general—on the one hand, Beethoven had an undying admiration for Napoléon’s personal courage, military prowess, and allegiance to the republican ideals of the French Revolution; on the other, he later had a repugnance against Napoléon’s rising ambition, ruthlessness, and self-admiration. While Beethoven despised tyranny, he was a political moderate, advocating neither the abolition of royalty nor aristocracy but also ever in search of expanding personal liberties. Much of his music would be written either in praise or in criticism of Bonaparte, though to his dying breath, Beethoven ever retained a powerful admiration for the man. And Metternicht spies and secret police knew it.

An Age of Music

Of all the arts at the end of the eighteenth century, music was the least esteemed. Musicians were low- or middle-ranking servants in the households of the great or minor cathedral functionaries. Immanuel Kant, summing up prevailing sentiment, admitted that music could “move the mind in a variety of ways, and very intensely” but that its impact was fleeting and “[did] not, like poetry, leave anything over for reflections.”[9] By 1800, however, the emotive power of music was becoming more valued in an age that was learning to prize individual expression, emotions, and personal inspirations. As Paul Johnson has noted, emotion created forms of knowledge as “serious as reason, and music, as a key to it, became more serious” and respected as a way “to enhance serious meaning.”[10] By the turn of the century, music was becoming more popular among the masses, and the concert began to rival the opera in popularity.

Vienna had long been the musical and operatic center of Europe. It was there that Joseph Haydn, who had known and admired Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), composed most of his 104 symphonies, 68 string quartets, and 20 concertos. And it was also in Vienna that Haydn met young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–81). A child prodigy, Mozart had composed his first minuet at age five, his first symphony at eight, his first oratorio at eleven, and his first opera at twelve. Mozart went on to write more than six hundred musical compositions, the likes of which have never been equaled for their joyful, uplifting songs and melodies. A lover of the stage, Mozart’s finest operas were Marriage of Figaro (1786), Don Giovanni (1787), and The Magic Flute (1791). Mozart and Haydn’s operas, symphonies, and sonatas came to epitomize the classical style in music.[11]

Portrait of Joseph Haydn, by Thomas Hardy.

Portrait of Joseph Haydn, by Thomas Hardy.

To think of music in the early nineteenth century was to think of opera, particularly comic opera, and no one had popularized the opera more by 1820 than the outstanding Italian composer Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868). So ardent an admirer of the music of both Haydn and Mozart that he was called “the little German,” Rossini wrote his first opera at age fourteen and went on to compose more than forty more. A man of sparkling wit, corpulent stature, and exuberant personality, by age twenty-one Rossini had become the idol of Italian opera. Some were even then calling him “the first composer in the world” and “the god of modern music.” In 1816 at age twenty-four, Rossini produced The Barber of Seville in just a three-week period, which almost immediately earned him both fame and fortune. His immense popularity followed him all across Europe, and when he met Beethoven, whom he greatly admired, in 1822, Rossini heard the older man say, “So you’re the composer of ‘The Barber of Seville’! I congratulate you. It will be played as long as Italian opera exists.” Rossini’s other great works included Cinderella (1817), Semiramide (1823), and William Tell (1829). In contrast to Mozart, who died in undeserved poverty and obscurity in 1791, Rossini lived in fame and fortune until his death in 1868. Music scholars maintain that he helped to push opera into the age of Romanticism, breaking down one convention after another.[12]

The age was also one that saw the piano replace the harpsichord in popularity. A transitional musical figure between the more classical style music of Mozart and Haydn and the more Romantic music of Beethoven was the Austrian composer Franz Schubert (1797–1828), the “Prince of Song.” Though he, like Mozart, died prematurely, he also was a prolific composer, producing more than six hundred lieder (written to the words and poetry of Goethe, Mayrhofer, and Schiller), ten symphonies, and more than a score of piano sonatas and duets, which Felix Mendelssohn (1809–47), Franz Liszt (1811–86), and Johannes Brahms (1833–97) later made memorable. His Unfinished Symphony of 1822 and his Symphony No. 9 are still frequently performed and are highly regarded by music lovers the world over. Schubert, a fervent admirer of Beethoven whom he first met in 1822, insisted on being buried next to the “Master’s” grave in the village of Währing.[13]

“No Longer a Prophecy but a Truth”—His First Maturity (1792–1802)[14]

As generous and courteous as his young student was irascible and often obstinate, Haydn was for Beethoven more an inspiration than a hands-on instructor. A careful student of Haydn’s symphonies, Beethoven copied many of his ideas and innovations and embarked on tours of his own, albeit to more local sites such as Leipzig and Berlin. Soon he became regarded as one of the finest young composers and pianists of his time. Though Haydn never warmed to the aloofness of Beethoven, Haydn proudly saw in him his protégé. Maynard Solomon has summarized Haydn’s influence on Beethoven as follows: “To study with Haydn was to learn not merely textbook rules of counterpoint and part writing, but the principles of formal organization, the nature of sonata writing, the handling of tonal forces, the techniques by which dynamic contrasts could be achieved, the alternation of emotional moods consistent with artistic unity, thematic development, harmonic structure—in short, the whole range of ideas and techniques of the Classical style.”[15]

It is not, however, sufficient to discuss merely the techniques or even the dynamics of Beethoven’s music. What is important to show is that he felt deeply compelled, if not driven, to compose. “Beethoven the pupil may have honestly and conscientiously followed the precepts of his instructors in whatever he wrote, . . . but Beethoven the composer stood upon his own territory, following his own tastes and impulses, [and] wrote and wrought subject to no other control.”[16] He was a man born with a mission, a calling, an unquenchable drive to write from the inner depths of his being and not the mere reflections of the age. He wrote from within. A deeply sensitive and spiritual man, though a Catholic only nominally, he loved nature and the conformities and uniformities of creation. Often depressed but still believing, he held to the fatherhood of God and the essential brotherhood of man. He loved his art and revered the talent he believed Providence had given him. As he once said, “Strength is the morality of those who distinguish themselves from the rest, and it is mine too.”[17]

His foremost patron in Vienna was Prince Karl Lichnowsky (1761–1814), a longtime financial supporter of Mozart who looked upon Beethoven almost as a son. Though Beethoven wanted to be free of aristocratic sponsorship, he needed the funds to pursue his lessons, travels, and tutorships. Mastering the skills of both harmony and counterpoint, between 1798 and 1802 Beethoven composed several piano sonatas, three piano concertos, and several chamber works. His boldly independent sonatas, especially for piano with cello or violin accompaniment, illustrated his budding genius and power of invention. For the first time, the piano assumed an essential, virtuoso role.[18] At a time when piano music was gaining in popularity and improvements were being made to the piano itself, the forcefulness and assertiveness of his music found growing favor with increasingly large audiences. Ever desirous of writing an opera to equal the likes of Mozart’s Magic Flute, Beethoven studied vocal composition under the imperial court Kapellmeiseter and opera composer Antonio Salieri (1750–1825). Salieri found Beethoven “self-willed and difficult” and was bewildered at his ingratitude, stubbornness, and multiplicity of compositions, wondering what other directions his restless student would take.

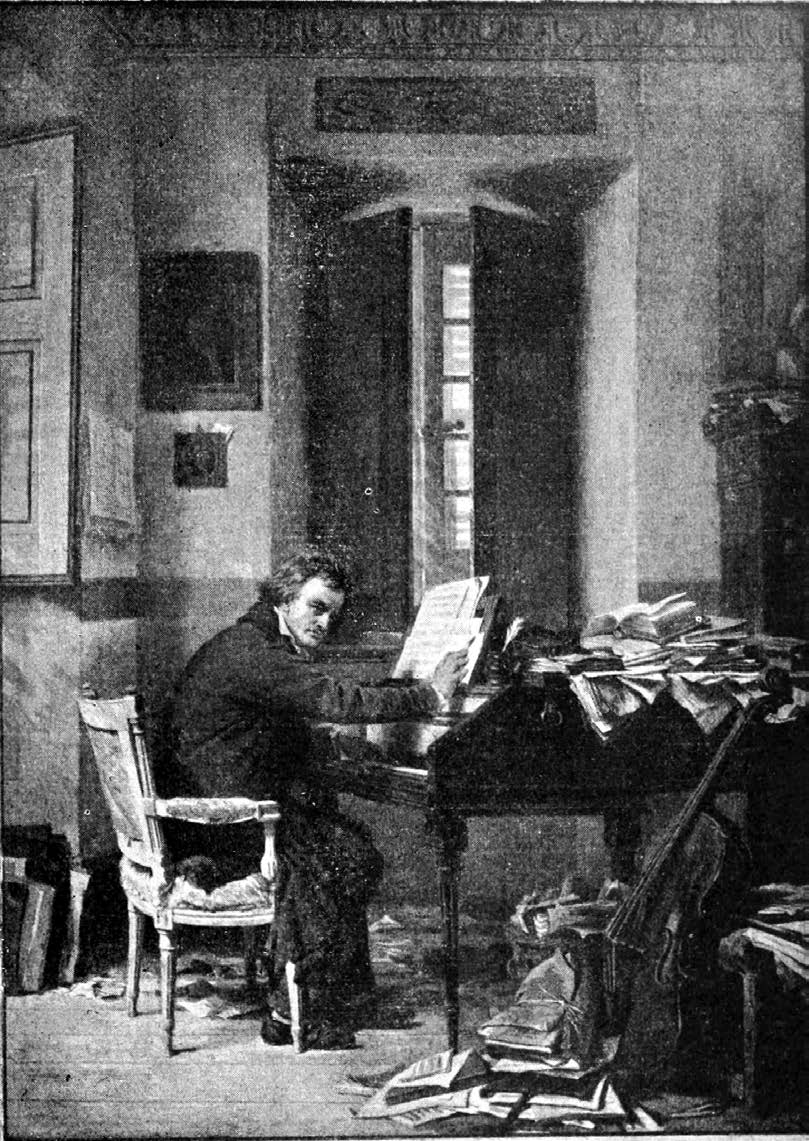

Haydn and Salieri were not alone in finding Beethoven a difficult young man to teach. Goethe regarded him as “an utterly untamed personality.”[19] Beethoven held powerful views and opinions and never took criticism gracefully. Short but powerfully built with a face scarred by an early attack of smallpox, Beethoven was awkward and clumsy and always seemed to be knocking things over. He would have been an utter failure on the dance floor. He often lost his temper and would brood in sullen moodiness for days. As a housekeeper, there were few bachelors worse. When ill-tempered, he would often throw his inkwell into the piano or up against the wall. No piece of furniture was safe with him, least of all a valuable one. “Imagine all that is most filthy and untidy,” remembered a visitor to Beethoven’s apartment. “Puddles on the floor, a rather old grand piano covered in dust and laden with piles of music, in manuscript or engraved. Beneath it (I do not exaggerate) an unemptied chamber pot. The little walnut table next to it was evidently accustomed to having the contents of the inkwell spilled over it. A mass of pens encrusted with ink—and more musical scores. The chairs, most of them straw chairs, were covered with plates full of the remains of the previous evening’s meal and with clothes.”[20]

He loved women from afar. “Beethoven was always glad to see women,” the famous pianist Ferdinand Reis once remarked, “especially beautiful, youthful faces, and usually when we walked past a rather attractive girl, he would turn around, look at her again sharply through his glasses, and laughed and grinned when he found that I had observed him. He was very frequently in love, but usually for a very short time.”[21] Distrusting deeply personal relationships, he was attracted physically but seldom emotionally. He had a fondness for women he could not have—either those married or engaged to be—as if he most enjoyed what he knew deep inside he would never have. Beethoven was not given to the women of the street, and nightlife for him meant composition, not moral dissolution. Most women were put off by his shoddy appearance and ungainly demeanor, believing he would be too much of a handful to train in the domestic arts.

Beethoven in His Study, by Carl Schloesser.

Beethoven in His Study, by Carl Schloesser.

However, if his home life and relationships with others were less than endearing or ideal, his music was becoming more powerful, more accomplished, more unforgettably beautiful and compelling as time went by. In the ten years between 1782 and 1792, he composed at least forty pieces, the most substantial being piano sonatas and quartets, many of which were never published. Two of his most famous works, composed in 1795, were his Sonata in C Minor (“Pathetique”) and his Opus 27, the hauntingly beautiful and utterly unforgettable “Moonlight Sonata”. In 1801 he composed his First Symphony and his first ballet, Prometheus. No longer a mere copyist, Beethoven was finding his own voice. While writing within the formal musical conventions and constraints of his time, he was pouring new musical wine into old bottles at such a pace and with such force and beauty that his role as Mozart’s successor was “no longer a prophecy but a truth.”[22]

“I Shall Seize Fate by the Throat”—The Second Maturity, 1802–12

Beethoven’s Second Maturity was characterized by a flurry of compositions in the new heroic style of music’s Romantic age, his finding but not securing the one woman he most deeply loved, the deterioration and ultimate loss of his hearing, and finally, despite all these bitter and profound disappointments, an abiding determination to write music even more majestic than before.

Key to understanding Beethoven as composer is his custom of using sketchbooks from as early as 1798 to capture melodies and bring sense, order, and continuity to his work. Almost always carrying blank composition books, he would compose several new pieces simultaneously and while on the go as his many moods and circumstances changed.[23] Such style of creation was in his nature. “I carry my thoughts about with me for a long time, often for a very long time, before writing them down,” he once confided to a friend, sharing profound insights into his creative process.

I can rely upon my memory in doing so, and can be sure that once I have grasped a theme I shall not have forgotten it even years later. I change many things, discard others, and try again and again until I am satisfied; then, in my head, I begin to elaborate the work in its breadth, its narrowness, its height, and its depth, and as I am aware of what I want to do, the underlying idea never deserts me. It rises, it grows up, I hear and see the image in front of me from every angle . . . and only the labour of writing it down remains, a labour which need not take long but varies according to the amount of time at my disposal, as very often I work at several things at the same time, but I can always be sure that I shall not confuse one with the other. [24]

Beethoven went on to comment on the origins of his ideas and the provenance or the source of his inspiration. “They come unevoked, spontaneously or unspontaneously. I could grasp them with my hands in the open air, in the woods while walking, in the stillness of the night, at early morning, stimulated by those moods which the poets turn into words, in[to] tones within me, which resound, roar and rage until at last they stand before me in the form of notes.”[25] He often made several revisions and refinements to each of these works over long periods of time, a continuing process of improving upon earlier themes and melodies, what Kinderman and others have called his “aesthetic project.” Thus Beethoven’s music ripened and matured, like vintage wine, over time through various moods and conditions, “a blend of the rational and sensuous achieved in a prolonged process of critical reflection.”[26]

Eventually Beethoven fever swept the continent, and he began making a very good living from commissions and the sale of his printed music. Besides piano sonatas such as Waldstein, he composed several violin sonatas including his Kreutzer Sonata (one of his finest violin sonatas), his Second Symphony, his Mass in C, and at least three piano concertos—all of which demanded the finest in keyboard virtuosity. Though he often played his own pieces, he was never considered a concert soloist. Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio, a story of daring, imprisonment, and rescue in the heroic style, was first performed in Vienna in 1804 at the same time the city was occupied by French forces. Panned by critics for being far too long and much too difficult to play, Fidelio was one of his rare failures. Some wondered if Beethoven, as much as he wanted to write opera, ever really understood the theater. [27]

Though given to writing in the formal classical style of Haydn, Mozart, and Handel, Beethoven was influenced by the rigor, power, and nationalistic fervor of postrevolutionary French music that was very much in vogue. Such music featured stirring military marches and songs, all designed to stroke nationalistic fervor and pride, and was perhaps best epitomized in the new French national anthem, “La Marseillaise,” composed by a young French lieutenant in 1792. However, it is also recognizable in such other contemporary patriotic works as “Rule Britannia,” “Finlandia,” and the enormously popular “God Save the King,” This genre of music, written for the masses, has been called the heroic style.

Yet Beethoven’s music was far more than heroic; it was romantic and free in the sense that it exhibited much more passion and emotion than Haydn’s would ever allow. Beethoven’s music spoke of tragedy and death, anxiety and aggression, vitality and victory. That may explain, at least in part, why his music is also called tragic—not because it is unhappy, indeed quite the reverse, but because, while recognizing the desperate struggles and disappointments of human existence individually and collectively, it nevertheless rises to a glorious, crowning celebration of the human soul.[28]

If Beethoven’s Second Symphony overwhelmed his critics with its strong contrasts, stirring military marches, tumultuous force, and “manic” finale, few were prepared for his Eroica, or Third Symphony. Filled with bewildering originality and far greater emotion than most of his earlier works, this enormously energetic piece owed everything to Napoléon, who was then proudly on the march. Despite Austria’s secret police, Beethoven spoke publicly in favor of Napoléon at every opportunity and took thinly veiled inspiration from an emperor many yet hoped would overthrow despotism and tyranny. Napoléon was, as Lockwood has well written, “a worldly counterpart of what Beethoven imagined his own role in the world of music could become.”[29] Beethoven initially dedicated his heroic-styled Third Symphony to Napoléon. “In writing this symphony,” one of his students recorded, “Beethoven had been thinking of Buonaparte, but Buonaparte while he was still First Consul. At that time Beethoven had the highest esteem for him and compared him to the greatest consuls of ancient Rome. Many of Beethoven’s closest friends saw this symphony on his table, beautifully copied in manuscript, with the word, ‘Buonaparte’ inscribed at the very top of the title page and ‘Luigi von Beethoven’ at the very bottom.

However, in 1804, upon learning that Napoléon had crowned himself emperor, Beethoven exclaimed, “So he is no more than a common mortal! . . . He will tread under foot all the rights of man, indulge only his own ambition and . . . become a tyrant.” Angrily he tore the top of the symphony’s title page in half and thrust it on the floor. Eventually he retitled it “Sinfonia Eroica.”[30] Another heroic work of this time was his Egmont overture, written from his admiration of a great Belgian warrior. In contrast, his Fourth Symphony, written in 1805 and 1806, was much slower and majestic, almost lyrical, manifesting his ability to write in other styles than the heroic.

Meanwhile, still longing for love, Beethoven proposed marriage to a nineteen-year-old countess, Giulietta Guicciardi (1782–1856), but she spurned him, as did Josephine von Brunsvik (1779–1821), a widow with four children. Later he met his “Immortal Beloved,” who was likely Bettina Antonie Brentano (1780–1869), a talented married woman with several children who was long out of love with her husband.[31] Of all the women in his life, she was arguably his only true love, the only woman who captured his deepest affections and fully reciprocated his love, the one woman more than any other he yearned to have. “I must live with you entirely, or not at all,” he pleadingly wrote, sensing the impending hurt he would bring upon himself. “Never shall another be able to possess my heart, never—never! Oh, God, why is one forced to part from her whom one loves so well. My life, my all!”[32]

Yet at the crucial moment Beethoven backed away, unwilling to destroy her marriage and unable, as Solomon writes, “to overcome the nightmarish burden of his past and set the ghosts to rest.”[33] The truth is, at the deepest level Beethoven could not share his life with anyone. He was too much the artist, too self-sufficient, too independent, too used to creative solitude to give himself away. An ancient Egyptian inscription that he kept on his desk said it well—one translated by Champollion, another of Beethoven’s heroes—“He is of himself alone, and it is to this loneliness that all things owe their being.”[34]

Exacerbating everything at this time of life was the highly disturbing fact that Beethoven had been losing his hearing for some time. Precisely when he began to go deaf has not yet been determined. Whether brought on by childhood beatings from his father or, as is more likely, from a disease of the inner ear, his hearing was fading as early as 1796. Writing to his close friend Karl Amenda in 1801, Beethoven painfully admitted the problem: “You must be told that the finest part of me, my hearing, has greatly deteriorated [and] has grown progressively worse. Whether it can ever be cured, remains to be seen.” For one who lived by his music, for whom music was his profession and his deepest consolation and inspiration, his increasing deafness was a most terrifying affliction. Though he was at first desperate for some kind of cure, he sensed early on that little could be done. “Illnesses of this kind are most incurable,” he plaintively wrote. “How miserably I must now live, and avoid all that is dear and precious to me. . . . Oh, how happy I should be if only I had the full use of my ears.”[35] As his condition worsened, it made him more of a misunderstood recluse than ever before. “I have been avoiding all social functions simply because I feel incapable of telling people,” he said to another friend.

In the theatre I have to keep quite close to the orchestra, lean against the railings, in fact, to understand the actors. The high notes of instruments, singing voices, I do not hear at all if I am at some distance from them. As for conversation, it is a marvel that there are people who have never noticed my deafness; as I have always been absent-minded, it is attributed to this. . . . Heaven only knows what will come of it . . . already I have cursed the Creator and my existence. Resignation! what a wretched refuge, and yet it is the only one left for me.[36]

For a time, Beethoven thought seriously of taking his life, believing that God had scorned and punished him. “I might easily have put an end to my life,” he admitted in 1802:

Only one thing, Art, held me back. Oh, it seemed impossible to me to leave this world before I had produced all that I felt capable of producing, and so I prolonged this wretched existence. . . . My determination to hold out until it pleases the inexorable Fates to cut the thread shall be a lasting one. . . . Recommend virtue to your children: for virtue alone, not money, can grant us happiness. I speak from experience. It was virtue that raised me up even in my misery. . . . How glad I am at the thought that even in the grave I may render some service.[37]

Then, at this critical turning point and deepest crisis of his life, he made peace with his condition and decided to go on as never before. “I shall seize fate by the throat,” he declared.[38] Beethoven managed to hold on to some of his hearing until about 1812, but the loss became so progressive thereafter that by 1818 he could hear virtually nothing at all.

As was his life’s pattern, there followed after this crisis a period of intense creativity—much of the music of Beethoven’s Second Maturity came in response to his loss of hearing. Indeed, one scholar has argued that his deafness proved ironically beneficial. Although he came to terms with his infirmity “only very gradually,” “his art actually became richer as his hearing declined.”[39] A key to understanding why this was so was his aforementioned use of sketchbooks in which melodies from years past, complete with his several revisions and self-criticisms, would find later melodic expression and fulfilment. This may well explain the origins of his incomparable Fifth Symphony.

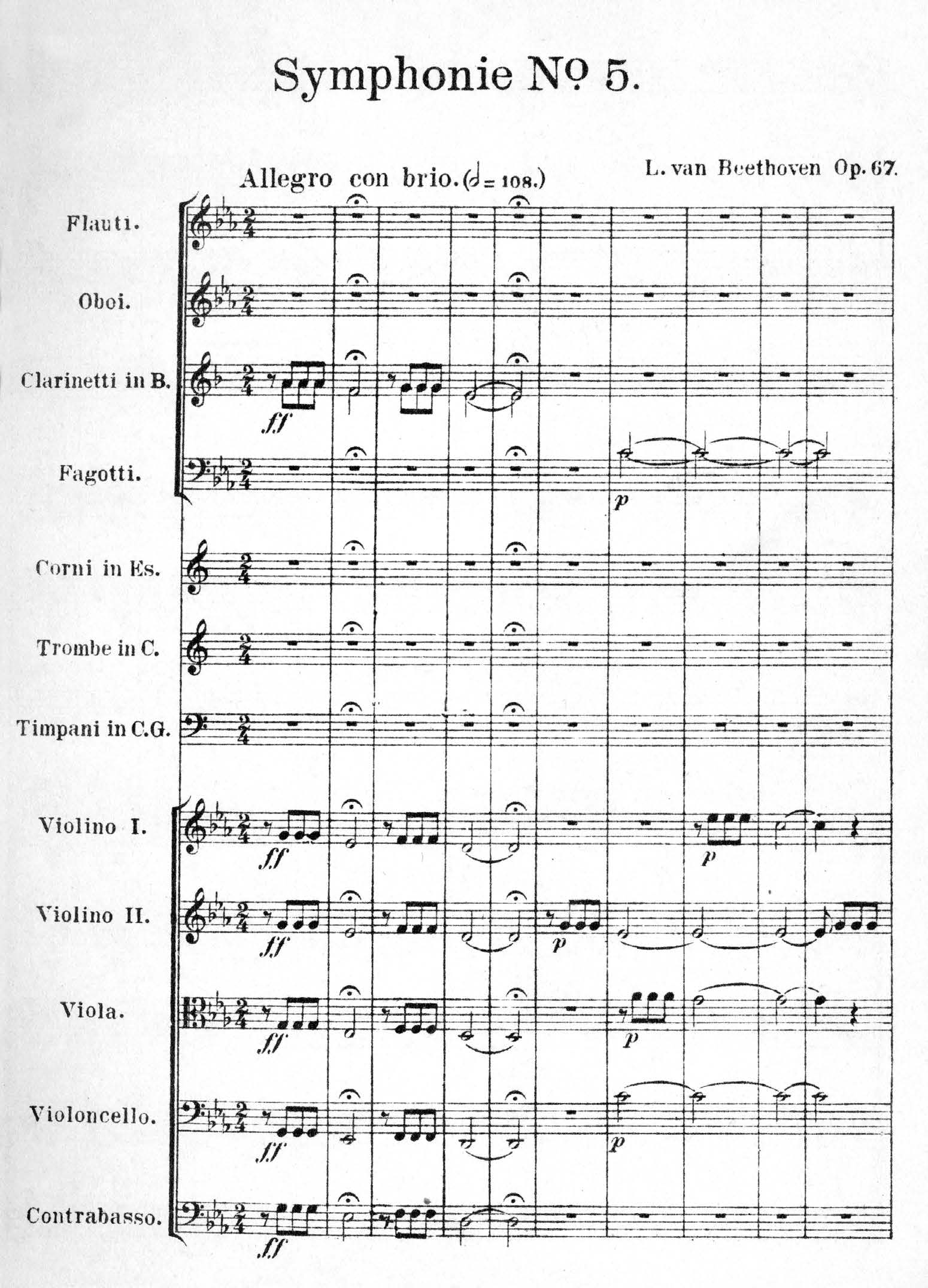

Beethoven's 5th Symphony No. 5—opening bars of the printed score for full orchestra instruments. Courtesy of Alamy Stock Photo.

Beethoven's 5th Symphony No. 5—opening bars of the printed score for full orchestra instruments. Courtesy of Alamy Stock Photo.

We writers and biographers, for all our best efforts, will always do a disservice to Beethoven and place him at a terrible disadvantage to the visual arts by trying to capture in writing the art and majesty of his music, a music that defies and transcends the power of pen and paper to re-create. Certainly that is the case in so short a study as this is. Like describing the beauties of a painting to one who cannot see, or the deliciousness of a Thanksgiving dinner to one who cannot taste, Beethoven must be heard, not read. The power of the pen simply cannot describe it. His majestic strains are for the ear, not the eye, and are to be experienced, not merely heard. His work transcends time and place. He is to music what Shakespeare is to literature—unforgettable, timeless, without peer.

Some passionately assert that his Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Opus 67, which he wrote simultaneously with the Sixth Symphony, remains his most famous work. Written in 1807 and 1808 at the time of the Treaty of Tilsit, his Fifth Symphony is a stirring revolutionary anthem not in praise of Napoléon but of his enemies—Tsar Alexander and the allied powers. Filled with patriotic and military energy, the Fifth Symphony is a classic example of thematic unification, how Beethoven took a very simple, magnificent opening melody, a single four-note (short-short-short-long) motif and wrote an entire symphony around it. It begins in C minor, ends in C major, and covers a wide range of moods from deep despair to near ecstasy. The last movement, featuring piccolo and trombone, culminates in a note of transcendent triumph. First performed in the Theater an der Wien in December 1808, it quickly attained a reputation as a prodigious, enduring anthem of magnificent music. Beethoven produced his Eighth Symphony and Quartet in F Minor, Op. 95, in 1812.

“God Has Never Forsaken Me”—The Final Maturity, 1813–27

At the same time Napoléon was suffering his ignominious Russian defeat, Beethoven was enjoying enormous success. Outside Vienna, he had “moved into a position of extraordinary preeminence and popular appreciation, unmatched by any nonoperatic composer of the era, and even surpassing the great popularity of Mozart and Haydn.”[40] Especially popular were his Third, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Symphonies—particularly the Fifth and Seventh because of the perception that they celebrated Napoléon’s defeat. Also popular were his Fidelio overture, Egmont overture, “Wellington’s Song,” and “Adelaide.”

Adored far more by the British than the French, Beethoven probably would have fulfilled his lifelong desire to visit England had it not been for certain diversions. He had become so popular and so highly revered that the many visitors became a distraction. A steady stream of students and admirers knocked at his Vienna residence, anxious to catch a glimpse or talk to the man many were now calling the “master.” Rossini, Schubert, and many other great composers all came in praise of him and his work. Yet he managed to keep his success in proper perspective. Writing to a friend in April 1815, he said, “Have you heard at all of my great works? Great, I say—compared with the works of the Supreme Creator, all things are small.”[41]

Lucky were the favored few, like the dazzling young eleven-year-old pianist, Franz Liszt, who managed to play for him and to receive personal instruction. After playing a piece by Bach, Liszt looked up, noting that Beethoven’s

darkly glowing gaze was fixed upon me penetratingly. Yet suddenly a benevolent smile broke upon his gloomy features, Beethoven came quite close, bent over me, laid his hand on my head and repeatedly stroked my hair. “Devil of a fellow!” he whispered, “such a young rascal!” I suddenly plucked up courage. “May I play something of yours now?” I asked cheekily. Beethoven nodded with a smile. I played the first movement of the C Major Concerto. When I had ended, Beethoven seized both my hands, kissed me on the forehead and said gently, “Off with you! You’re a happy fellow, for you’ll give happiness and joy to many other people. There is nothing better or greater than that.”

Remembering this moment with fondness, Liszt later called it “the palladium of my whole artistic career.”[42]

Liszt’s own teacher, Carl Czerny (1791–1857), himself an accomplished pianist, went on to describe Beethoven at the keyboard: “No one equaled him in the rapidity of his scales, double trills, skips, etc. . . . His bearing, while playing was perfectly quiet, noble, and beautiful, without the slightest grimace—but bent forward low, as his deafness increased; his fingers were very powerful, not long, and broadened at the tips from much playing, for he told me that in his youth he generally had to practice until after midnight. . . . He could scarcely span a tenth. . . . He was also the greatest sight reader of his time.”[43]

Maria von Weber described him as follows: “His hair [was] dense, grey, standing up, quite white in places, forehead and skull extraordinarily wide and rounded; high as a temple, the nose square, like a lion’s, the mouth nobly formed and soft, the chin broad with those marvelous dimples. . . . A dark ruddiness coloured his broad, pock-marked face; beneath the bushy and sullenly contracted eyebrows, small, shining eyes were fixed benevolently upon the ‘visitors.’”[44]

As a piano teacher, he could be both surprisingly patient and incredibly demanding but for reasons not immediately obvious. “When Beethoven gave me a lesson, he was unnaturally patient,” Ferdinand Reis once recalled.

He would often have me repeat a single number ten or more times. . . . When I left out something in a passage, a note or a skip, which in many cases he wished to have specially emphasized, or if I struck a wrong key, he seldom said anything; yet when I was at fault with regard to the expression, the crescendi or matters of that kind, or in the character of the piece, he would grow angry. Mistakes of the other kind, he said, were due to chance; but these last resulted from want of knowledge, feeling or attention. He himself often made mistakes of the first kind, even when playing in public.[45]

Goethe saw, perhaps better than most, the strengths and the weaknesses of his fellow countryman. “I have never seen an artist more concentrated, energetic and intense,” he wrote in 1812.[46] Amazed at Beethoven’s talent, Goethe gave this insightful premonition of Beethoven’s uncomfortable evening with the empress at the Congress of Vienna, an insight into how his deafness was warping his personality and how Beethoven may have often been misunderstood by others: “His is a personality utterly lacking in self-control; he may not be wrong at all in thinking that the world is odious, but neither does such an attitude make it any mere delectable to himself or to others. On the other hand, he much deserves to be both excused and pitied, for his hearing almost failed him, which probably does more harm to the social part of his character than to the musical part. He, who in any case is laconic by nature, is now becoming doubly so because of this defect.”[47]

Visitors, however, were not nearly as much a distraction as family concerns soon became. At what surely would have been a most productive time in his life, Beethoven became embroiled in a highly charged emotional tug-of-war over the guardianship of his young nephew. For the next five years, his music suffered noticeably. Even before his father’s death in 1792, Beethoven had taken on a paternalistic, even possessive interest in his younger siblings. Later, he became particularly incensed with his brother, Caspar Carl, and his marriage to Johanna Reiss, whom Beethoven disdainfully regarded as little more than a criminal and a street prostitute. When Carl died young in 1815, Beethoven became fretful and obsessive over his nephew, Karl, and—convinced that Karl’s mother was totally unfit to raise the child—launched into a long series of legal challenges to win guardianship. While no doubt Reiss’s reputation was a tainted one, something more must explain Beethoven’s implacable hatred toward her and the enormous emotional and monetary expense he endured in promoting his case. While it is true that his brother Carl had wanted Beethoven to have at least a share in the custody of his child, Beethoven sought for more—the chance to be the father he had always wanted to be. Losing his first legal custody battle, he turned sullen, depressed, ever angrier. He began to look worse than ever before, pale and frightful in his long, dark overcoat and low top hat, wandering the streets until late into the night. While he turned to drink, Beethoven was not an alcoholic; however, the secret police would surely have arrested him for wandering alone at nights had he not been so popular a figure. Some even thought he was going mad.

When in early 1820 the courts reversed their ruling (after Johanna had become pregnant out of wedlock) and gave Beethoven co-guardianship of his nephew, his moods considerably brightened. He soon oversaw the boy’s education and development, and though he loved his nephew, he interfered too much and was far too possessive, demanding to know his every move, even spying on the young man’s romantic interests. Only after Carl had threatened suicide and demanded that his uncle back away did Beethoven finally surrender such tight control. Eventually Beethoven and his sister-in-law reconciled, and he would will more than half his estate to his nephew and a considerable amount to Johanna.

With the conflict resolved, Beethoven gravitated back to his music, but this time with an unequalled determination and passion. Absolutely “every thing was subordinated to his work.” Some argue that his emotional struggles may have even served as “catalysts” to bring his deepest feelings to the surface, thereby helping to set the scene for a “breakthrough of his creativity into hitherto imagined territories.”[48]

Some of his finest string quartets and piano sonatas (Opp. 109–11), including the Hammerklavier Sonata, can be dated to 1818–20. Early in 1821, he composed and compiled his “Eleven Bagatelles for Piano” (Opus 119), which included his famous “Für Elise.” These bagatelles (literally meaning “trifles”) were short piano pieces, either cast-offs from more advanced sonatas or concertos, some going back forty years to his earliest childhood compositions. Often the delight of today’s piano students, his bagatelles feature unforgettably haunting melodies and “convey a sense of completeness within the smallest boundaries.”[49]

In these later years, Beethoven became increasingly religious, not in the denominational mode of the avid churchgoer but in the spiritual sense of recognizing and worshipping a loving, omnipotent, supernatural being, a benevolent Father in Heaven. In February 1820, he penned one of his most famous citations: “The moral law within us, and the starry heavens above us.”[50] His faith had matured to the point of believing in a God who had intervened and overruled man’s politics for good in the past and would so again in the future, that nature was his sublime handiwork, and that humankind was his crowning accomplishment. In the words of the Psalmist, “For thou hast made him a little lower than the angels, and hast crowned him with glory and honour” (Psalms 8:5). At this time, Beethoven’s most earnest inspiration did not come from Napoléon or Alexander, kingdom or nationality, but the fatherhood of God and the humanity of man. At the deepest personal level Beethoven believed God had blessed him beyond measure with talent, and despite his deafness—indeed, perhaps because of it—Beethoven would now write perhaps his greatest pieces of music in praise of him. “God has not forsaken me,” he wrote just two years before his death.[51]

This shift in spirituality accounts for the composing of what Beethoven thought was his finest piece, his immense Missa Solemnis in D Major, written in four parts: Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei. This mass was originally intended for the installation ceremony of his friend and pupil Archduke Rudolf of Austria as bishop of Olmutz in 1821, but it was not completed until three years after. It first performed in St. Petersburg in March 1824. Beethoven’s chief aim in writing it was to awaken and permanently instill spiritual feelings not only within the singers but also within the listeners. For at least a year, he had studied meticulously Handel’s Messiah and Mozart’s Requiem Mass. Beethoven’s work demonstrates its composer’s mastery of the highest forms of liturgical music. Born out of his entire life’s experience, Missa Solemnis depicts the death, Resurrection, and victorious ascension of Christ and the inner peace of the soul. Written on his original score were his words “Brothers, above the starry text of heaven, a beloved Father must dwell.”[52]

The Ninth Symphony—“Ode to Joy”

With his Missa Solemnis completed by mid-1823, Beethoven returned to his last and most glorious composition—a culmination of a lifetime of musical creation—a veritable climax of talent. Written over an eight-month span between July 1823 and February 1824 while at his retreats in Hetzendorf and Baden, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony—“Ode to Joy”—stands as his grandest symphony and one of the finest pieces of music ever written. Louis Schlösser, a contemporary musician, said of Beethoven’s efforts in composing it, “The Ninth Symphony filled his imagination, at home and in the highest spheres and the composition of this gigantic work displaced every other occupation at this time.”[53]

If it was his finest work, it came at a time of his most intense physical afflictions. By 1823, Beethoven was almost totally deaf, although it is true that at odd moments he could hear the faintest of sounds. Furthermore, his eyes had become so weak after years of strain working late by candlelight that he was visually impaired. His lifelong colitis had worsened to the point of acute pain and discomfort. He likewise suffered from jaundice and increased liver disorder. Yet he remained surprisingly cheerful, determined to complete his life’s work. Having been composing this piece for over thirty years but never taking the time to write it down, Beethoven’s Ninth was his life’s most fulfilling work.

Since his youth, Beethoven had been drawn to the writings of the great Romantic poets, most notably Friedrich Schiller and his “Ode to Joy,” which he wrote in 1785. Schiller’s views and writings on the brotherhood of man were a deep well of inspiration to Beethoven, and as the years passed, these feelings intensified. Beethoven had witnessed Napoléon Bonaparte’s rise and subsequent decline and applauded the enduring values of the French Revolution and its assault on those forces that put down man’s liberty, and he was now ready to write a colossal objection to tyranny of all kinds, including Metternich’s petty secret police. This piece would be an anthem to liberty, an optimistic tribute to humanity, a musical ode to joy, and a sacred rendering to God. Though he had failed to compose a great opera, Beethoven was still anxious to put to music Schiller’s unforgettable words and phrases, believing no instrumentation could match the power of the human voice to portray such lofty human sentiments. He would write what is essentially a choral anthem on the grandest possible scale, with Schiller’s poem sung in the stirring climax of the fourth movement. Translated into English, the text reads as follows:

Joy, beautiful spark of divinity,

Daughter of Elysium,

We enter thy sanctuary

Heavenly one, drunk with fire;

Your magic binds again

What custom rudely divided;

All mankind becomes brothers,

Where your gentle wing abides.

The Ninth Symphony owes less to Haydn and Mozart and far more to the supernal harmonies of Bach and the Baroque era. Written in the key of D major, the opening of the overture connects thematically with the finale’s climax; indeed the finale, in chorus form, reconnects with the introduction, giving the piece a certain wholeness and completeness. Some have called this device the art of “foreshadowing, early in the work, important musical events come.”[54] At times, it stops almost in midsentence; dramatic and compelling pauses signal new waves of majestic music. Incredibly complex in its entirety, a score written for a gigantic orchestra and deliberately designed to test the finest talents of the greatest violinists, cellists, and other instrumental musicians and singers of the age, it at one point features the voice of a single baritone, placed perilously close to the climax. Then, with an avalanche of onrushing sound of orchestra and chorus combined, the Ninth Symphony reaches its unforgettable choral climax in everlasting tribute to the unrelenting joy of man, in the liberty of soul, and in coming into the presence of God—a musical vision of humanity’s unconquerable spirit and of God’s everlasting majesty! As one musical scholar said, it is “an enduring monument to the compatibility of beauty and truth.”[55] In this stirring musical vision of God and His creations, could even prophets have asked for anything more?

The Kärntnertor Theater. Das Kärntnertortheater in Wien, by Carl Wenzel Zajicek.

The Kärntnertor Theater. Das Kärntnertortheater in Wien, by Carl Wenzel Zajicek.

The piece was originally commissioned by London’s Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, which was fully aware that Beethoven’s fortunes had been decimated by currency devaluations and years of legal wrangling. Beethoven, however, decided late in the composition to have it initially performed in his beloved Vienna. On what surely must have been an unforgettable, four-and-a-half-hour evening of music, both the Missa Solemnis and the Ninth Symphony—each with four movements—premiered together at the Kärntnertor Theatre on the evening of 7 May 1824. The much-enlarged orchestra and chorus only had time to practice these pieces two or three times before the opening performances, and from what the critics said, it showed.

The mass went first, and after a shortened intermission most returned to hear the Ninth Symphony and to participate in a moment never to be forgotten in music history. In the audience were many of the finest of Vienna’s musicians, composers, and critics, as well as royalty. Kapellmeister Michael Umlauf (1781–1842) was the principal conductor, assisted by the world-renowned violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh (1776–1830). At their side and simultaneously turning the pages of his score while beating time, stood Beethoven. Umlauf had previously warned the choir and orchestra to pay little attention to Beethoven since he was too deaf to know precisely where they were in the score. The music, despite a flawed performance, electrified the audience. Either at the end of the scherzo or, as is more likely, at the end of the entire symphony, amid deafening applause, Beethoven—who we must remember could not hear and who could barely see—still stood poring over his score, his back to the audience, until the contralto soloist, Caroline Unger, plucked at his sleeve and pointed him to the cheering audience. Whereupon the master turned and bowed to the weary but adoring audience, jubilant in its encores of applause.

Although not a financial success, the Ninth Symphony was met with positive critical reviews. E. T. A. Hoffman, perhaps the most renowned critic of his age, called it a “masterpiece,” praising it “for its capacity to transport the listener into the realm of the infinite.”[56] Another critic stated: “Art and truth here celebrate their most brilliant triumph. . . . Who can ever surpass these inexpressible heights?”[57] Most German composers afterward, including Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms, Buchner, and Mahler, described the Ninth Symphony as the “central bulwark of musical experience.”[58] Performed in London the following year (1825) but not in America until 1846, the Ninth was not an instant worldwide success. The world only gradually caught up to that night in Vienna in 1824. However, by the late nineteenth century, the Ninth Symphony had taken on mythic proportions as one of Europe’s finest musical compositions, transcending time and place. Interpreted in so many ways and by so many different musicians and conductors, it remains a modern favorite of classical music and has been played at such memorable occasions as Olympic performances and in celebration of the tearing down of the Berlin Wall.

Beethoven continued to compose after 1824, including his last quartets, but nothing on so grand a scale. Opus 135, another string quartet, was his final piece. When he finally died of a liver complaint on 26 March 1827, ten thousand Viennese turned out in a steady downpour to pay their last respects. The Austrian dramatist and poet Franz Grillparzer (1791–1872) delivered the oration. Of all the swelling words and phrases, this remains: “He was an artist, and who can bear comparison with him? . . . Thus he lived, thus he died, thus he shall live forever.”

Notes

[1] Solomon, Beethoven, 27.

[2] Forbes, Thayer’s Life of Beethoven, 59.

[3] Siepmann, Beethoven, 6.

[4] Lockwood, Beethoven, 15.

[5] Some believe that Beethoven, when seventeen, played for Mozart and that Mozart said of him: “Keep your eyes on him; some day he will give the world something to talk about.” Forbes, Thayer’s Life of Beethoven, 87. See also Landon, Beethoven, 52.

[6] Lockwood, Beethoven, 59. Throughout his life, Beethoven, never good at handling money, earned his living by way of commissions.

[7] Solomon, Beethoven, 70.

[8] Kinderman, Beethoven, 1, 27.

[9] Johnson, Birth of the Modern, 118.

[10] Johnson, Birth of the Modern: 117–19.

[11] For two excellent studies on Mozart, see Gutman, Mozart; and Deutsch, Mozart.

[12] Two of the many excellent works on Rossini include Osborne, Rossini, and Weinstock, Rossini.

[13] In 1888, both Schubert’s and Beethoven’s graves were moved to Zentralfriedhof, where they can now be found next to those of Johann Strauss II and Johannes Brahms. For more on Schubert, see Kreissle, The Life of Franz Schubert, Newbould, Schubert; and Gibbs, Life of Schubert.

[14] Dividing Beethoven’s life into three distinct periods called “mafurities” was first proposed in 1828 and has since settled into something of a consensus. Though attacked by various critics as overly simplistic, such a scheme refuses to die because, in spite of all, it obviously does accommodate “the bluntest style distinctions” in Beethoven’s output. Sadie, New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 3:95.

[15] Solomon, Beethoven, 93.

[16] Forbes, Thayer’s Beethoven, 150.

[17] Hamburger, Letters, 29; hereafter referred to as Letters.

[18] Kinderman, Beethoven, 45.

[19] Solomon, Beethoven, 106.

[20] From the Memoirs of Baron de Tremont, Letters, 77.

[21] From the “Biographical Notes” of Ferdinand Ries, Letters, 59.

[22] Lockwood, Beethoven, 174.

[23] Johnson, Taylor, and Winter, The Beethoven Sketchbooks, built upon the earlier work (1865) of Nottebohm, Two Beethoven Sketchbooks, to bring to greater light some eight thousand pages of Beethoven’s sketchbooks and loose sketch leaves.

[24] From “An Account by Louis Schlosser,” 1823, Letters, 194–95.

[25] From “An Account by Louis Schlosser,” 1823, Letters, 194–95.

[26] Kinderman, Beethoven, 64.

[27] Opera was not Beethoven’s strong suit. Most musical scholars consider Fidelio (originally titled Leonore) as falling far short of Beethoven’s best efforts, even though he revised it in 1814. Kinderman, Beethoven, 102–7.

[28] Solomon, Beethoven, 252.

[29] Lockwood, Beethoven, 187.

[30] From the “Biographical Notes” of Ferdinand Reis, Letters, 47.

[31] Sadie, New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 3:85.

[32] Beethoven “To His Immortal Beloved,” 7 July 1806 [or 1807], Letters, 113.

[33] Solomon, Beethoven, 246.

[34] Solomon, Beethoven, 206.

[35] Beethoven to Karl Amenda, 1 June 1801, Letters, 34–41.

[36] Beethoven to Franz Wegeler, 29 June 1801, Letters, 41–42.

[37] From Beethoven’s “Heiligenstadt Testament” (a small village near Vienna), 1802, Letters, 50.

[38] Beethoven to Franz Wegeler, 25 June 1801, Letters, 41–42.

[39] Kinderman, Beethoven, 61.

[40] Solomon, Beethoven, 324.

[41] Beethoven to “Amanda,” 12 April 1815, Letters, 137.

[42] From “Franz Liszt’s Account of His Visit to Beethoven,” 1823, Letters, 197–98.

[43] From C. Czerny, Uber den richtingen Vortrag der samtlichen Beethoven’s schen Klavierwerke, in Lockwood, Beethoven, 284–85.

[44] From “Max Maria Von Weber’s Biography of His Father,” Letters, 208.

[45] Siepmann, Beethoven, 38.

[46] From a letter to Christine von Goethe, 19 July 1812, Letters, 116.

[47] From a letter to Zelter, 2 September 1815, Letters, 116.

[48] Solomon, Beethoven, 327.

[49] Lockwood, Beethoven, 397.

[50] Kinderman, Beethoven, 238.

[51] Ludwig von Beethoven to Karl B., 14 September 1825, Letters, 240.

[52] Lockwood, Beethoven, 407, 411.

[53] From an account by Louis Schlösser, 1823, Letters, 193.

[54] Kinderman, Beethoven, 240.

[55] Kinderman, Beethoven, 283.

[56] Lockwood, Beethoven, 306.

[57] Solomon, Beethoven, 351.

[58] Lockwood, Beethoven, 418.