"We Never Had So Ominous a Question"

Henry Clay, The Rise of America, and the Value of Political Compromise

Richard E. Bennett, “'We Never Had So Ominous a Question': Henry Clay, The Rise of America, and the Value of Political Compromise,” in 1820: Dawning of the Restoration (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 259‒86.

“We should become the center of a system which would constitute the rallying-point of human freedom against all the despotism of the old world.”[1] So wrote Henry Clay, one of America’s finest patriots and most successful compromisers, who on several different occasions would run for president of the United States. Although he was never elected to that high office, his most fascinating life and his many contributions to his native country will serve as a springboard for the following short study of American history in the age of 1820.

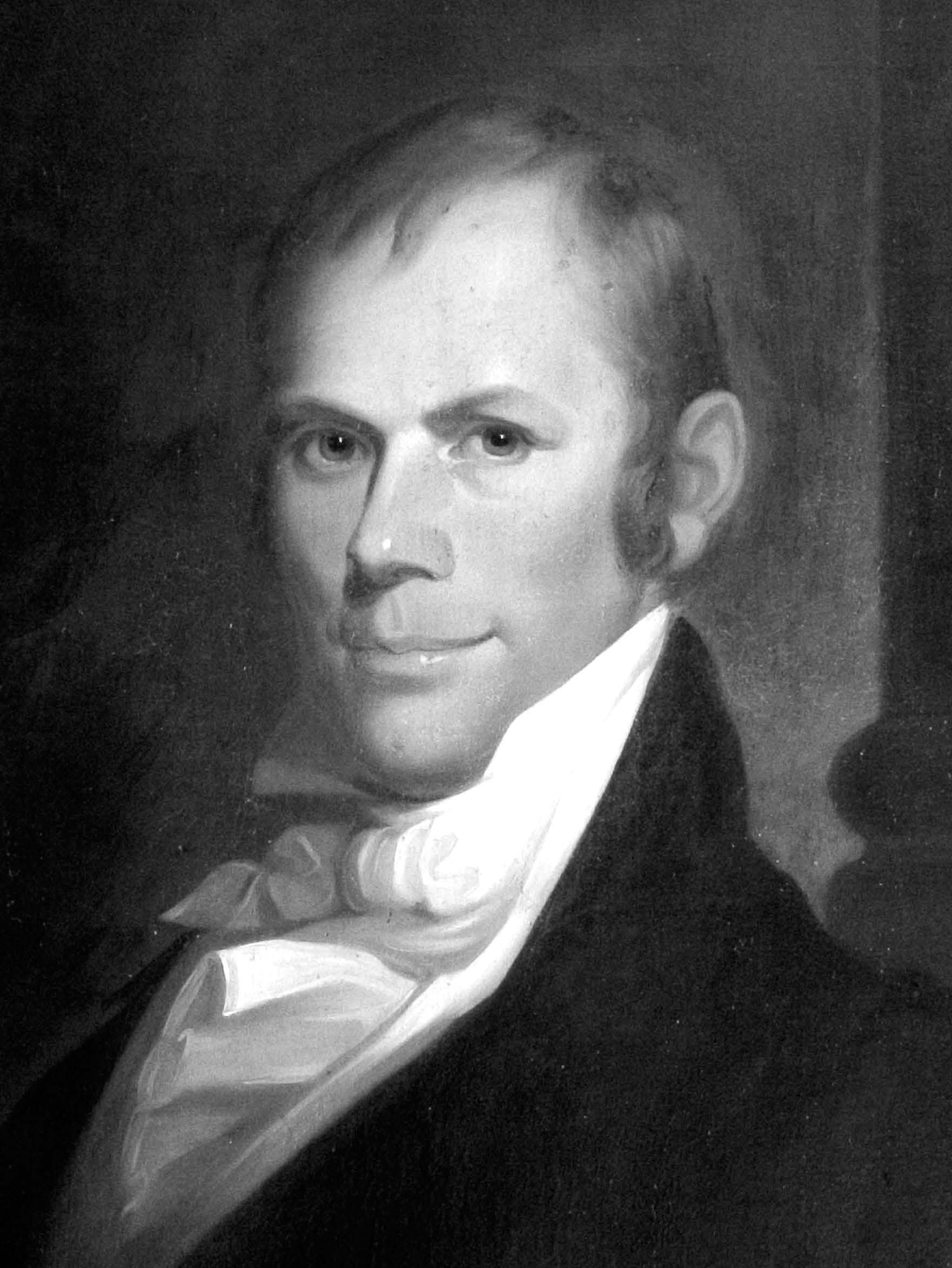

Henry Clay, by Matthew Harris Jouett.

Henry Clay, by Matthew Harris Jouett.

In the year of our Lord 1820, the young and emboldened United States of America increasingly viewed itself as the rising bastion of liberty and equality for all the world to see, the last, great hope of better things to come. Yet it almost dismembered itself in a cacophony of harsh-sounding warnings and epithets that reverberated through the halls of Congress and all across the land in debates over admission of its first state west of the Mississippi River. This stunning controversy, what Thomas Jefferson called “a fire bell in the night,” marked the greatest crisis in America’s short history up until that time.[2] Had it not been for the statesmanship of one particular Kentucky politician, the bloodbath of the American Civil War may well have begun forty years ahead of its time and perhaps with a much different outcome.

At issue was the admission of Missouri into the Union and the fractious controversy over slavery. Warned Senator Freeman Walker of Georgia in a speech he delivered in Congress on 19 January 1820:

I fear—much do I fear—that the imposition of restrictions on the refusal to admit [Missouri] unconditionally, into the Union, will excite a tempest, whose fury will not be easily allayed. It is, perhaps, wrong to predict or anticipate evil, but he must be badly acquainted with the signs of the times, who does not perceive a storm portending; and callous to all the finer feelings must he be, who does not dread the bursting of that storm. . . .

I behold the father armed against the son, and the son against the father. I perceive a brother’s sword crimsoned with a brother’s blood. I perceive our houses wrapped in flames, and our wives and infant children driven from their homes. . . . I trust in God, that this creature of the imagination may never be realized. But if Congress persist[s] in the determination to impose the restriction contemplated, I fear there is too much cause to apprehend that consequences fatal to the peace and harmony of this Union will be the inevitable result.[3]

As Representative Thomas W. Cobb, also of Georgia, phrased it, “We have kindled a fire which all the waters of the ocean cannot put out, which seas of blood can only extinguish.”[4]

Speaking for the majority in the House of Representatives that strongly opposed Missouri’s entrance into the Union as a slave state, an exasperated and emotional James Tallmadge of New York fervently responded: “Sir, if a dissolution of the Union must take place, let it be so! If civil war, which gentlemen so much threatens, must come, I can only say, let it come! My hold on life is probably as frail as that of any man who now hears me; but while that hold lasts, it shall be devoted to the service of my country—to the freedom of man. . . . Now is the time. [Slavery] must now be met, and the extension of the evil must now be prevented, or the occasion is irrevocably lost.”[5]

Meanwhile, several thousand miles away, in Göttingen, Germany, two young American students were studying abroad, oblivious to the rancorous debates then paralyzing Washington. They raised their glasses in a 4 July 1820 toast to the goodness, greatness, and divine destiny of their glorious, young American republic. One of them, nineteen-year-old George Bancroft of Worcester, Massachusetts, who would become one of America’s most towering nineteenth-century future historians and intellects, read the honor roll of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and President James Monroe. He then proclaimed his allegiance to his native land: “The great forests of the west, the hum of business, the vessels of commerce, the American Eagle, ‘the sweet nymph of liberty,’ the abolition of slavery, and last of all, ‘Our country—the asylum of the oppressed.’”[6]

The year 1820 therefore marked both a dream and a warning, an unfolding promise of liberty in a land that had grown sixfold from a mere 1.6 million in 1760 to 9.6 million in 1820, an unmistakable warning of the unbridgeable divide over the existence and attempted extension of that peculiar institution of slavery. Bancroft’s optimism was surely tempered by Senator Walker’s gloomy prophecies. This tug of war of expectations forms the entry point for our following discussion on the rise of America and its place on the world stage.

“Was Ever a People More Blessed?”

If the age of 1820 was one of rights and revolutions, of liberty and rising equality, of congresses and enduring peace agreements, and of continuing exploration and discovery, then the story of America fits well into this larger historical pattern. These impulses were far more than a national or American expression; they were of universal origins, but they played out remarkably well on a national scale in the New World.

The American dream was not to be obscured or dominated by its fears. Said Henry Clay: “But if one dark spot exists on our political horizon, is it not obscured by the bright and effulgent and cheering light that beams all around us? Was ever a people so blessed as we are, if true to ourselves? Did any other nation contain within its bosom so many elements of prosperity, of greatness, and of glory?”[7] Or, as Jefferson so optimistically painted it in his first inaugural address, “[America] is a chosen country, with room enough for our descendants to the thousandth and thousandth generation.”[8]

A native son of the American Revolution, Henry Clay was born near Richmond, Hanover County, Virginia, on 12 April 1777. He was the son of John Clay and Elizabeth Hudson, both of English descent. His father, a Baptist minister, died young, and his mother remarried Captain Henry Watkins. Clay’s early formal schooling came under the hand of an itinerant Englishman, Peter Deacon, at the old field log schoolhouse. It was a very meager education, however, as it was ever interrupted by clearing, planting, plowing, harvesting, and every other chore expected of a healthy boy growing up on a farm. Clay always regretted not learning more about history, literature, and the classics. “I never studied half enough,” he lamented later in life.[9] What he did learn was how to write legibly, how to work hard, how to debate, how to ride horses, and how to play the fiddle and have a good time. He made friends easily and could drink and party with the best of them. Nothing in these early years indicated anything more than an average young man with a normal future.

Clay grew up in a most exciting time and place, with the sounds of the Revolutionary War in his backyard. He could remember Lt. Tarleton’s British regulars ransacking his home and running their swords into the newly made graves of his father and grandfather in search of buried goods. Clay thus grew up with a deep wellspring of patriotic devotion to his country and an intense hatred of the British. He viewed General George Washington as his childhood military hero and Thomas Jefferson as God’s architect of American independence.

Clay doubtless heard at the dinner table, fireplace, and schoolroom all about the inequities of the British Parliament’s Stamp Act of 1765, the resultant Virginia Resolutions spearheaded by that fiery patriot Patrick Henry, the Boston Massacre of 1770, and the Boston Tea Party of December 1773, which led to the well-known American battle cry of “No taxation without representation.” When Great Britain responded with a set of harsh measures that included the suspension of the Charter of Massachusetts, the other colonies made the Boston cause their own and assembled together in Philadelphia nine months later in Samuel Adams’s First Continental Congress.

Then in April 1775 a large body of British troops stationed in Boston, while seeking stores and supplies outside the city, met armed colonial resistance for the first time at Concord and at Lexington. A similarly armed confrontation soon followed at Bunker Hill and Breed’s Hill, where British forces lost 1,500 men in a pyrrhic victory over the well-armed colonialist defenders. When the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia in May 1775, it appointed George Washington of Virginia as commander-in-chief of the American forces, drafted the Articles of Confederation, and adopted Thomas Jefferson’s Locke-inspired Declaration of Independence, which was passed and signed on 4 July 1776, the birthdate of the United States of America.

The details of the ensuing Revolutionary War, from Washington’s tactical retreats to the eventual surrender of General Cornwallis and seven thousand British regulars at Yorktown in 1781—all these and more were surely not lost on young Clay. The ultimate result was British recognition of American independence and the birth of a new nation. Two years later, in 1783, Great Britain ceded to the United States the vast territory between the Alleghenies and the Mississippi River. Four years later the Continental Congress passed the Ordinance of 1787, which allowed for the ultimate organization of six new states on equal basis with the original thirteen states in what was then considered the Northwest, with slavery expressly forbidden therein.

The Articles of Confederation failed, however, in one critically important aspect—passing legislation for the federal government to raise money and to control commerce. The goal was “a more perfect union” that balanced the unique needs of the new nation with the vested interests of the several states. For this purpose, a new Federal Convention convened in Philadelphia in May 1787 when Clay was only ten years old. After months of toiling through a long, hot summer, the several delegates crafted a new Constitution of the United States with seven articles that, among other things, called for a tripartite form of government—the executive branch, with an elected president; the legislative or congressional branch, with a bicameral elected House and Senate; and the judicial branch, with a Supreme Court nominated by the president and ratified by Congress. The Constitution provided Congress power to lay and collect taxes and pay debts, allowed for a difficult but possible amendment process, and ensured elected representation, with two representatives per state in the Senate and with proportional representation by population in the House. When it was ultimately approved by the individual states, several amendments were incorporated that limited the powers of Congress, the first of which became the Bill of Rights. These preserved the freedoms of religion, speech, press, and the right to assemble and reserved to the states those powers not expressly delegated to the federal government. With New Hampshire’s ratification vote in June 1788, the Constitution became the supreme law of the land.

In contrast with the almost simultaneous French Revolution (see chapter 1), the American Revolution, which in many ways inspired the French uprisings, was a much less bloody affair. Unlike France, which regurgitated the accumulated abuses of a corrupt caste system over a millennia, the American Revolution was directed at its mother country and resulted in a far more peaceful transition from one form of parliamentary democracy to a republican style of government. While both the French and American republics chose military figures as their first leaders, the United States was spared the bloody wars of liberation that soon engulfed the European continent. Fifty-seven-year-old general George Washington, “Columbia’s Savior” and the man most highly regarded in all the land, was unanimously elected America’s first president and inaugurated in 1789.

“Fun to Have Around”: Henry Clay’s Formative Years

Washington had been president for only three years when fifteen-year-old Clay began working as a clerk in Peter Tinsley’s prestigious law office in Richmond, Virginia, in 1792. An “extraordinarily intelligent and diligent worker, and friendly and fun to have around,” Clay soon gained the attention of George Wythe, chancellor of the Virginia High Court of Chancery.[10] Wythe was himself a signer of the Declaration of Independence, the most learned jurist in Virginia, and the law professor to Jefferson, Chief Justice John Marshall, and James Monroe. He was also a firm opponent of slavery. Wythe took Clay under his wing as his amanuensis and student for the next four years, introducing him to great literature and encouraging the development of his debating skills. As historian Robert Remini put it, Wythe “was the father Henry Clay never had.”[11] For a few months Clay even worked for Robert Brooke, former governor and later attorney general of Virginia.

Clay was tall and thin and as confident, relaxed, and self-assured as he was singularly unattractive, “loosely put together.” Although he developed a devastating wit, a biting sarcasm, and an overbearing arrogance, his native charm and unfailing sense of humor easily made him a great many friends. Never a loner, he played as hard as he worked, spending as many hours in backroom gambling halls with convivial company playing whist and poker as he did in the barrooms of the law. He developed a love for gambling, hard drink, and beautiful women. As he once admitted, “I have always paid peculiar homage to the fickle goddess.”[12] But he knew his limits. After a late-night reverie, he was almost always back at his law desk the next morning. He was quick to apologize to anyone he had offended the night before. And after his marriage to Lucretia Hart in 1799, he was ever faithful to her.

Even before he was admitted to the Virginia bar at the age of twenty, Clay had formed his own political convictions. His time with Wythe and Brooke had endeared him to the Jeffersonian doctrine of states’ rights, agrarian democracy, the French Revolution, the ideals of a limited interpretation of the Constitution, and a commitment to the Republican Party. James Madison became another one of his heroes.

Following his mother and stepfather, he moved from Virginia to Lexington, Kentucky—then a town of two thousand—in 1797, five years before Kentucky became America’s fifteenth state. He soon gained admission to the Kentucky bar, whereupon he opened a law office, specializing in criminal law. Save for farming, law was the only career he ever seriously considered. A superb actor, Clay loved to debate and developed a flair for the theatrical. His voice had a wonderful musical tone that could rise and fall as if on cue. With such talent, the courtroom soon became his stage.

Yet there was much more to Clay than sound, fury, and histrionics. He earned his reputation as a very good defense attorney because of the clarity of his arguments, his careful preparations, and his highly intelligent reasonings based on comparisons, contrasts, and common sense. There was always enormous substance in what he had to say, and he genuinely persuaded gentlemen and juries to his way of thinking.[13]

Often accepting land as payment for his legal services, while at the same time running his wealthy father-in-law’s—Colonel Thomas Hart—many businesses, Clay soon owned several thousand acres, some of which he eventually developed into his Ashland estate, just a mile or two out of town. He soon gained a reputation as a successful land developer. Clay enjoyed farming, horse breeding, and his estate, where he later retreated often for rest and inspiration. Like many other Kentucky farmers, he owned several slaves, some of whom he had inherited from his father and grandfather. Thanks to his wife who was as good if not a better manager of money than he was, Ashland usually prospered. Although theirs would be a happy marriage, it was constantly beset with deep sorrow. All six of their daughters and two of their sons would predecease them, and two of their other boys would spend time in insane asylums. Though Clay was a believer in God, he deliberately refrained from joining any organized religion until much later in life, when he became an Episcopalian.

An exciting new era in American history began to unfold with the election of Jefferson as the country’s third president in 1800. An intellectual, philosopher, science enthusiast, and careful constrictionist in constitutional matters, Jefferson will ever be remembered as much for expanding the nation as for defining it in writing. Ironically, for one so committed to performing no more than what the Constitution allowed, it was Jefferson who exercised unstated power to secure the vast Louisiana Purchase from Napoléon in 1803. For a sum of fifteen million dollars, which was then a staggering amount of money, and with one stroke of the presidential pen, America’s land mass almost doubled, extending from West Florida (Louisiana and Mississippi) all the way to the Rocky Mountains, although the precise boundaries of the purchase were not yet determined.

An Engraving of “Ashland,” Henry Clay's Home near Lexington, Kentucky, by Carl Schurz, in Life of Henry Clay (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1899), vol. 2, secondary frontispiece.

An Engraving of “Ashland,” Henry Clay's Home near Lexington, Kentucky, by Carl Schurz, in Life of Henry Clay (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1899), vol. 2, secondary frontispiece.

Jefferson also dispatched Lewis and Clark on their famous expedition up the Missouri River, to the Yellowstone and Columbia Rivers, and eventually to Oregon in 1804–6, thereby laying tentative American claim to the great Pacific Northwest. Soon other intrepid explorers like Zebulon M. Pike, Henry M. Breckenridge, and Stephen H. Long further defined the exciting vastness of the American West and described the territory west of the Mississippi River to the Rockies as the Great American Desert. America’s frontiers were moving relentlessly westward while Europe was sinking into the abyss of the Napoleonic Wars.

It wasn’t long before rugged pioneers and restless farmers were seeking out new lands and opportunities in the new American West. Many were anxious to escape the cold and rocky terrain of New England. Others wanted to leave the overly aggressive cotton plantation owners of Georgia and the Carolinas. And some fled the economic and political exigencies in Great Britain and Europe. Fiercely individualistic, highly ambitious, anti-elitist, and intolerant of indigenous claims of any kind, the new American commoner would not be denied. Vermont was accepted into the Union in 1792 as the fourteenth state, followed by Kentucky (the same year), Tennessee (1796), Ohio (1803), Louisiana (1812), Indiana (1816), Mississippi (1817), Illinois (1818), Alabama (1819), and Maine (1820).

In 1803, during Jefferson’s presidency, Clay entered politics as an elected assemblyman in the first Kentucky legislature. A Jeffersonian Republican by leaning, he was nonetheless astute enough to support the manufacturing and mercantile interests of his new adopted state, and he recognized the need for active government participation in its economic behalf. The peculiar genius of Clay was that he was as much pragmatic as he was idealistic; he was a conciliator who could see the value of opposing political interests. Early on, he learned that the art of compromise was necessary if anything lasting were to be accomplished. In large part, his role in having the state step in and save the ailing Bank of Kentucky led to the legislature electing him to the United States Senate to replace John Adair, who had unexpectedly resigned his seat. Clay was only twenty-nine years old at the time, one year younger than the required age of thirty, but no one cared to ask.

Never known for bashfulness, the aspiring young senator soon made a name for himself on the Senate floor as a skilled orator and debater. Even federalist senator John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts took notice of Clay and his Jeffersonian ideals. “Quite a young man—an orator—a Republican of the first fire.”[14] Clay strongly argued for the federal government to take the lead in making better internal improvements such as roads, bridges, and canals, and levying the requisite taxes and tariffs to make them all possible. Such would lead to a continental home market, further westward expansion, and promotion of new manufacturing possibilities. In such arguments lay the kernel of his later famous “American System” economic plan. A pragmatic Republican who championed states’ rights, he nonetheless saw the need for a strong national government and sound banking principles. Clay blended the ideals of Jefferson with the financial practicalities of Alexander Hamilton.

Clay owned that wonderful political asset of not taking personally the jibes and jostlings of congressional debate. He usually rose above personal injury, but there were occasions when he felt his honor and good name were so impugned that he would fight back. Such was the case in 1809. Believing in the cult of honor, then still prevalent in the South, Clay could have suffered the same fate as Alexander Hamilton, who died in a duel with Aaron Burr in 1804. In 1809, Clay and former U.S. senator, Humphrey Marshall, a cousin of Chief Justice John Marshall, went to the wall in a duel of their own. Although wounded in the thigh, Clay was fortunate to survive. Marshall suffered only a few bruises and went on to write a two-volume history of Kentucky.

The following year, his wounds healed, Clay returned to the Senate at a time when strong congressional pressure was being exerted on Jefferson’s successor, President James Madison, to declare war once more on Great Britain. Upon quitting the Senate, Clay returned home, where he was elected a member of the House of Representatives, which he greatly preferred over the staid Senate. In short order, largely because of his anti-British stance, he was elected Speaker of the House in 1811 at the age of thirty-four, perhaps the only freshman Congressman ever to be so honored. Soon dubbed “the Western Star,” Clay, then as much a war hawk as any other elected official from the West and South, soon joined forces with those who saw conflict as the preferred resolution. Concluded Josiah Quincy, the Boston federalist, Clay “was the man whose influence and power more than that of any other produced the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain.”[15]

America’s “Second War of Independence”

The War of 1812 was but an echo of that much greater conflict then raging on the European continent. Napoléon and his Grande Armée were marching on Moscow in their last, great campaign. The French had placed embargos on British and foreign trade all across Europe, and in return Great Britain, supreme ruler on the sea, was blockading marine trade in and out of Europe. America was a hapless neutral power that was eventually shut off from foreign trade and commerce. New England manufactories and Southern cotton producers were especially hard hit. The resulting war was essentially an unnecessary conflict, born of the hysteria of the time, that solved nothing. As Edward Channing dryly put it, “The War of 1812 was waged by one free people against another free people in the interest of Napoleon, the real enemy of them both.”[16]

Of particular annoyance to America was the humiliating British habit of impressment. American ships were captured and their American sailors were impressed, or sworn into forceful duty aboard British navy vessels, often in sight of the American seacoast. This practice of “inalienable allegiance” was, at base, a deliberate mockery of American citizenship, and it demonstrated, perhaps more than anything else, British arrogance and contempt for the new nation. When President Jefferson foolishly retaliated with an embargo of his own in 1807, it only made things worse for American trade and commerce.

America’s anglophobia at home was no less galling to the British, whose hands were then full fighting “Napoléon.” The upstart American, particularly in the western frontier states, suspected British collusion with angry, displaced Native American tribes who felt cheated by unfair American land treaties that increasingly deprived them of their long-held homes and hunting lands. Indian warriors like Tecumseh and his brother “The Prophet” were difficult to defeat, even with the full force of General William Henry Harrison and the United States Army.

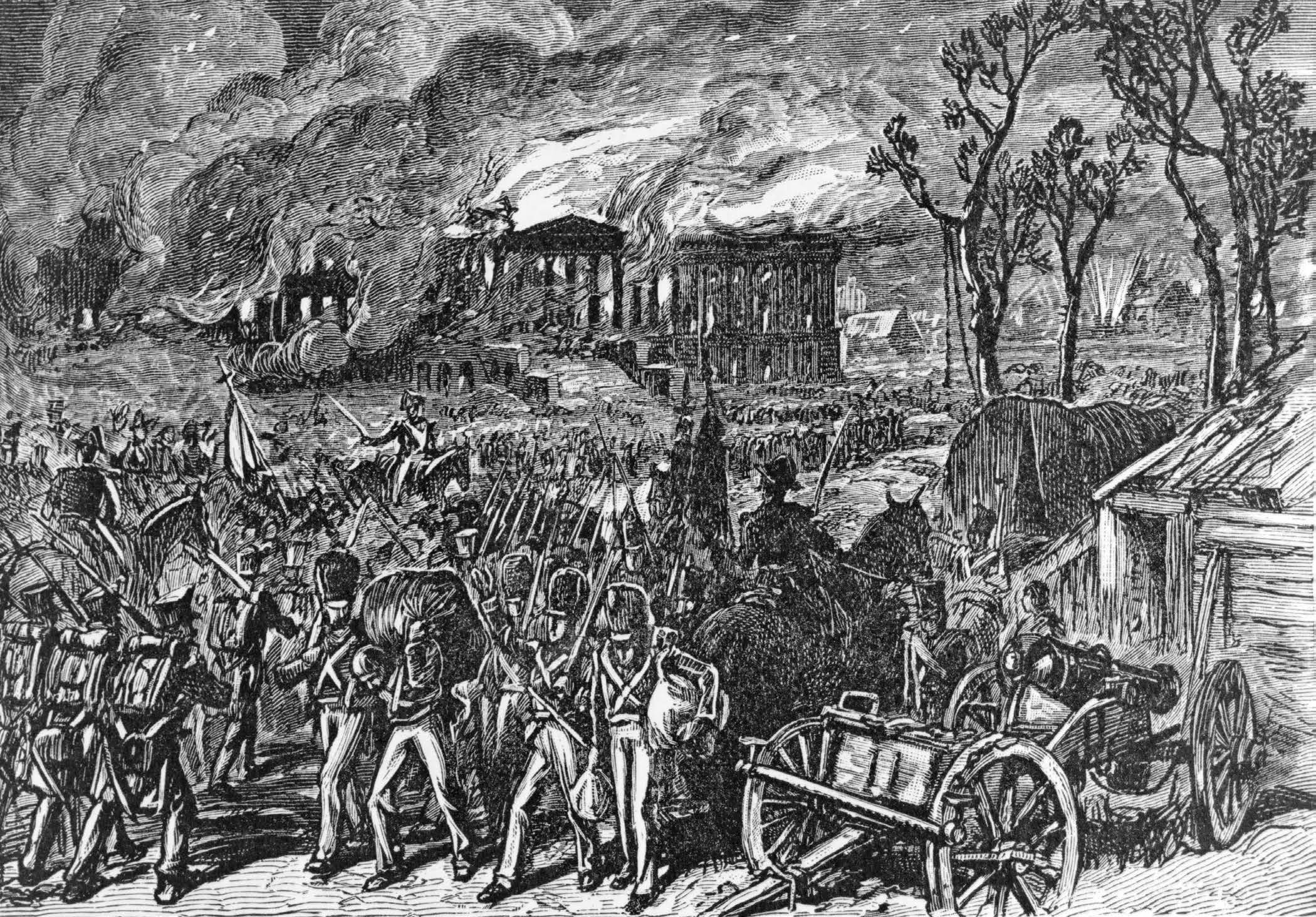

While the Americans distinguished themselves at sea and on the waters of the Great Lakes during the War of 1812, they generally failed miserably on land. American losses at Niagara, Lundy’s Lane, and Detroit were as much the result of state militias refusing to obey national orders as from British General Isaac Brock’s, and other British general’s superlative field strategies. The American goal of the conquest of Canada backfired, with British raiders burning Washington, D.C. On 24 December 1814 the peace treaty of Ghent was signed in Belgium. News was slow to travel, so the brightest moment for American land forces—General Andrew Jackson’s brilliant 1815 victory in New Orleans against a vastly superior army of British regulars—came two weeks after the signing of the treaty. The utter futility of the war is apparent in that none of the issues that started the war—impressment, squabbles over fisheries, and British demands for navigation of the Mississippi River—were even mentioned in the final treaty.

The manner of ending the War of 1812 accomplished three very important things. First, the Treaty of Ghent was the first formal international recognition of American nationality. For this reason, the War of 1812 has been called America’s “Second War of Independence.” The fact that America had taken on such a vastly superior power and held its own, if not more so after Jackson’s stunning victory, instilled a sense of pride in many Americans and established a lasting peace that would endure for half a century.. Shortly afterward, in a separate treaty, Spain forfeited all its claims to East or modern Florida, consenting to sell what she could no longer defend.

Capture and Burning of Washington by the British, in 1814 (wood engraving, 1876), by unknown artist.

Capture and Burning of Washington by the British, in 1814 (wood engraving, 1876), by unknown artist.

Second, the pro-English Federalist Party found itself on the losing end of popular support as the war dragged on, and by 1820 it had virtually disappeared from off the American political landscape. Commensurate with its decline came the “Era of Good Feelings,” in which federalist partisan politics, at least on the surface, had given way to Jeffersonian principles.

Third, because of America’s failure to win the war, Canada, then better known as British North America, was now assured of a great, new future of its own. While Upper Canada (Ontario) and Lower Canada (Quebec) still held on to vastly different cultures, religions, and languages—the one province English and the other French—the war and its treaty ensured their future as well as those of the maritime provinces—New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. In 1820, William Lyon Mackenzie (1795–1861) and Sir John A. Macdonald (1815–91)—two men synonymous with Canadian independence and later confederation—immigrated from Scotland and soon began their own careers in Toronto (York) and Kingston, respectively. With the later signing of the Rush-Bagot Treaty, recognizing the 49th parallel as the border between the United States and Rupert’s Land extending from the Lake-of-the-Woods to the Rocky Mountains, the possibility of another great nation from sea to shining sea was all but assured. Some forty-three years later, the Dominion of Canada did indeed come into being on 1 July 1867.

As one of the five American peace commissioners assigned to Ghent to hammer out the treaty ending the war, Clay played a greater role forging the peace than he had ever done supporting the war, despite the fact that he had spearheaded a new conscription bill to raise thousands of troops. Clay clashed more, through his compulsive gambling, with his fellow commissioners, including John Quincy Adams, the senior American statesman, than he ever did with his British counterparts, who were mere puppets of Lord Castlereagh anyway. Distrustful of Tsar Alexander’s “unholy alliance” and of growing Russian hegemony and its potential alliance with America, Castlereagh preferred to forge a separate peace treaty with America. Still young and brash, Clay’s sometimes erratic behavior offended some, but he was unbending in preventing the surrender of any American territory. In the end, the war concluded on the basis of the “status quo ante bellum,” or things as they were before the war, and both the United States and British Canada preserved all their former territories.

“Settle and Sell, Settle and Sell”

In many ways, Henry Clay epitomized the America of 1820. He was incurably optimistic, ardently if not irritably patriotic, and restlessly ambitious, seeking new lands, wealth, and limitless opportunities in the ever-expanding westward reaches of the confident, young nation. With the Revolutionary War over and won, the Louisiana Purchase completed, and the War of 1812 now behind them, Americans looked forward to what many would soon call their Manifest Destiny.

At its most dynamic core was the family. One may speak of the spirit of equality and American democracy, as Alexis de Tocqueville so brilliantly did in his magisterial book Democracy in America (1832); the predominantly rural and agricultural way of life, as so many British travelers described America at this time; or the changing and challenging economics. Yet at its base, America rose on the shoulders of the family—its greatest strength. “Marriage,” Tocqueville observed, was more “highly regarded” in America than in any other nation.[17]

From his early childhood, a young man was trained to tame the wilderness. “Every man, or nearly every man,” one female traveler noted, “knows how to handle the axe, the hammer, the plane, all the mechanic tools in short, besides the musket, to the use of which he is not only regularly trained as a man but practiced as a boy.”[18] Raised to be independent and self-reliant, the American farmer—with his skills, tools, practices, ambitions and a coarse common sense—was expected to make a living. A young farmer’s hardest work was in felling trees, burning stumps, clearing the land, fencing, planting, and harvesting. Split-rail fences stretched everywhere, demarcating one farm from the other. Families often grew their own food in tended gardens. And as they prospered, log cabins with dirt floors gave way to painted houses and cottages with larger rooms, better chimneys, larger stables and painted barns. The spirit of improvement seemed everywhere.

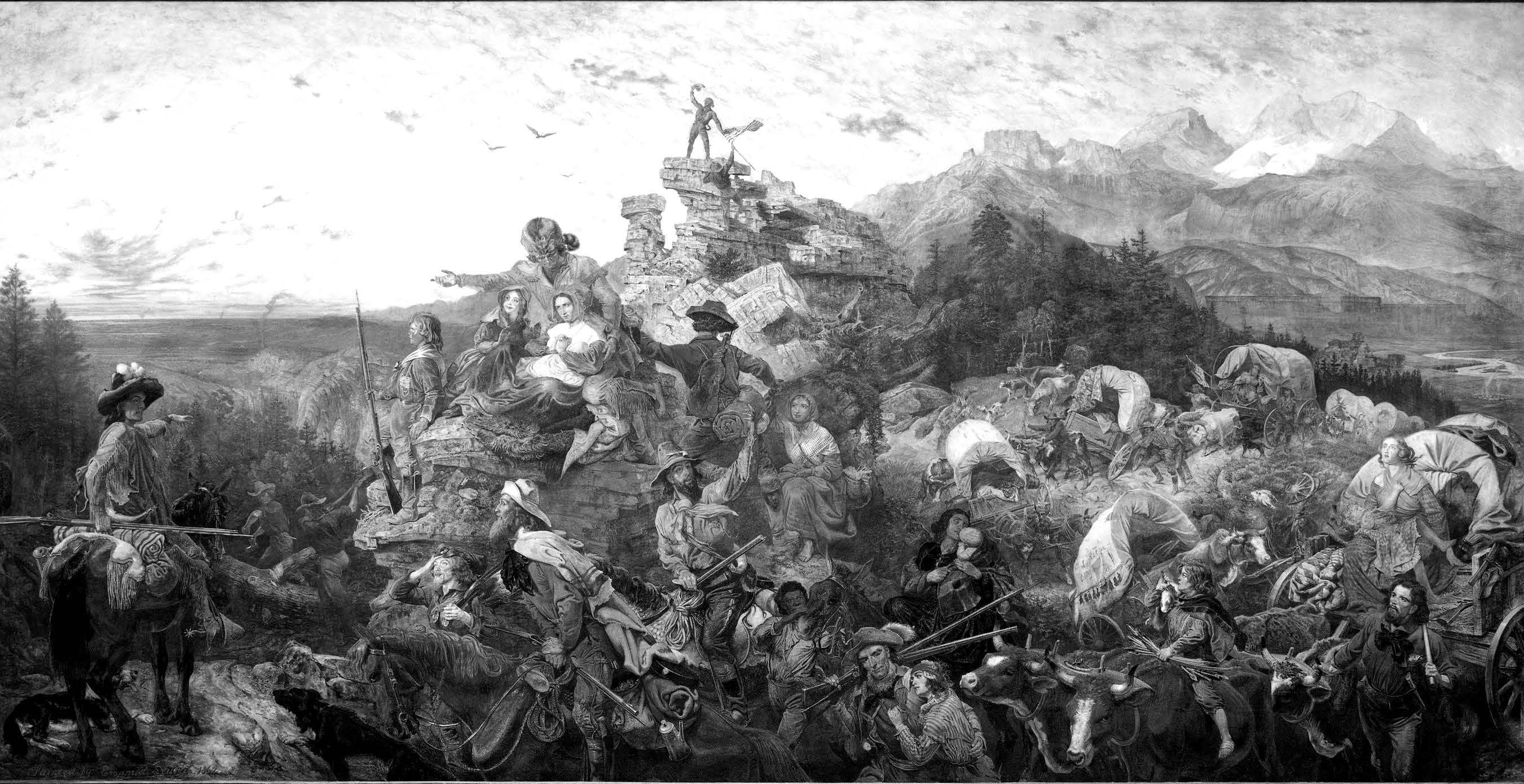

Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way, by Emanuel Leutze.

Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way, by Emanuel Leutze.

While a basic elementary education was more or less universally accessible, education beyond that was not particularly valued. Most Americans cared more about the practicalities of making a living than the generalities of abstract thinking. They were far more interested in business and politics than they were in music and literature. Higher education was almost an anomaly, with more energy devoted to heated argument and debate than to idle book reading, at least among young men. For those who did find time to read, the historical novels of Sir Walter Scott were very popular, and Hannah More was more widely read than Shakespeare. The works of American writers such as James Fenimore Cooper and Washington Irving bespoke the rise of American literature dominated by such publishing houses as Carey & Lea in Philadelphia and Harper & Brothers in New York.

And there was little time for recreation or diversion. Organized sports were a future luxury. Many found entertainment in hunting and fishing and in rough-and-tumble fighting in the bar or tavern. If chewing tobacco was an everyday experience, drinking was even more constant, even among the young women. If outright drunkenness was rare, “constant tippling” was everywhere.[19]

At the risk of overgeneralizing, the America of 1820 was always on the move in a state of restless agitation, eyeing more and better land westward, as if afraid of finding insufficient room for growing families. And with the new land system of 1800 that divided townships into thirty-six square miles and subdivided them into sections of 640 acres, one could buy small or large acreages at very competitive prices. It was, as one scholar has described, a time of “settle and sell, settle and sell.”[20]

America was thus predominantly rural and agricultural. The largest cities were New York City (pop. 122,000), Philadelphia (64,000), Boston (43,000), Charleston (25,000), and other eastern seaboard cities and towns with internal riverside cities such as Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, which were in their industrial infancy. What manufacturing did exist was centered primarily in New England, with as many women working in the new cotton mills and factories as men. Labor unions were nonexistent, and many, such as President Jefferson, believed manufacturing was far more apt to corrupt personal morality than a life on the land could ever do.

Patterns and pathways of transportation were in their infancy. Families travelled over ill-marked paths and byways by wagons or carts, often migrating in groups of family caravans. From Auburn, New York, in April 1815 came the statement that “during the past winter our roads have been thronged with families moving westerly. It has been remarked by our oldest settlers, that they never before witnessed so great a number of teams passing, laden with women, children, furniture, etc. to people the fertile forests of New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio.”[21] Tens of thousands were on the move in what the Niles Register, one of America’s most popular American newspaper magazines of the day, referred to as “The Great Migration.” “Old America seems to be breaking up, and moving westward,” wrote Morris Birkbeck in 1817 while on the road to Pittsburgh. “We are seldom out of sight, as we travel on this grand track towards the Ohio, of family groups, behind and before us.”[22] By 1820 there were nearly 1,140,000 more people living west of the Allegheny Mountains than in 1810.

Roads were often impassable, with few inns or conveniences along the way. The Genesee Road west of Utica to Buffalo, New York, and the Forbes Road over the Allegheny Ridge and across Pennsylvania were rough precursors to the National or Cumberland Road, which stretched from Cumberland, Maryland, to Wheeling, West Virginia, and over the mountain passes that for so long had held back westward migrations. The 363-mile Erie Canal, completed in 1825, connected the Hudson River in the east to Lake Erie in the west, greatly facilitating trade and travel. It opened up settlement of the old Northwest, promised the rise of Chicago, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and other great lake ports, and guaranteed the place of New York as America’s largest city and commercial center. The invention of Robert Fulton’s river steamboat in 1806 ushered in a new industrial age of sea and river travel. And with the organization of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in 1828, travel to places far removed from rivers would soon become possible. Americans were in haste and on the move, and there seemed to be a confused clamor of new trails and travels and innovations and opportunities, as if Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle were just waking up to the morning of a bright new day.

The nation then was enjoying another form of liberty—a country virtually out of debt. As a country without income tax, the United States relied on income from the sale of public lands and from duties (or tariffs) on imported goods. The debts incurred by the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 were virtually eliminated by the late 1820s, and the government was running a balanced budget by 1823.[23]

Yet people were moving just to eke out a living. Though many sought wealth, few found it. There were very few millionaires in 1820. Foreign markets for American products and produce were hard to come by, and distribution systems within the country were few and poorly developed. America’s greatest internal debate, other than that of slavery, was surely the murky issue of banking and finance. Since the collapse of the unpopular federalist-inspired First National Bank in 1811, financial chaos had ensued. Despite the bank being rechartered in 1816, this was a time of serious recession. Without a recognized standard national currency and sufficient hard specie, foreign coins and cut money abounded with “half bits” or “quarter bits” of Spanish gold or silver dollars. Small, local wildcat banks proliferated to fill the void, each issuing its own paper money, often accepted at a fraction of its value by the larger eastern banks. The notes of unchartered banks were especially discounted. In 1819, many state banks collapsed, and enormous amounts of Western real estate were foreclosed by the Bank of the United States. Not until 1823 would the economy finally pull out of the nation’s first economic depression. America’s banking and currency system was in chaos, with no federal reserve system, no deposit insurance programs, no uniformity, and precious little regulation and oversight, resulting in a general lack of trust and confidence. The two great political parties that followed the Era of Good Feelings—Democratic and Republican—debated the issue for years, with Henry Clay favoring and Andrew Jackson vehemently opposing the concept of a national bank, which he believed was a dangerous, cruel, and useless monopoly. It would take years and other panics and depressions before the American banking system finally stabilized.

While it was the province of young men to learn the professional arts and sciences and the rigors of law, medicine, and business, young women were generally educated in such domestic arts as spinning, weaving, cooking, reading, writing, and other skills considered necessary to build a home. It was customary for women to marry young—often only between the ages of twelve to fourteen—and to have a family of six or more children before the age of twenty-five. Divorce was a rarity, and large families the order of the day. The politics of America was, at base, the economics of the home. The spirit of democracy, independence, and equality that colored governmental politics emanated in large measure from the log cabins and houses of the nation, the very capillaries of society.

However, it took consistent, backbreaking labor of both husband and wife, working equally hard together, to tame the wilderness and make a living as the following traveler’s account will show of one young New York family who had turned their cabin into an inn.

Alighting at the little tavern, we found the only public apartment sufficiently occupied and accordingly made bold to enter a small room, which by the cheering blaze of an oak fire, we discovered to be the kitchen and, for the time being, the peculiar residence of the family of the house. An unusual inundation of travelers had thrown all into confusion. The busy matron, nursing an infant with one arm and cooking with the other, seemed worked out of strength and almost out of temper. A tribe of young urchins, kept from their rest by the unusual stir, were lying half asleep, some on the floor and some upon the bed, which filled a third of the apartment. We were sufficed to establish ourselves by the fire, and having relieved the troubled hostess from her chief incumbrance, she recovered good humour and presently prepared our supper. While rocking the infant, it was with pleasure that I observed its healthy cheeks and those of the drowsy imps scattered around.[24]

This same female traveler opined that the future of woman in America was bright indeed.

I must remark that in no particular is the liberal philosophy of the Americans more honorably evinced than in the place which is awarded to women. . . . [They] are assuming their place as thinking beings, not in despite of the men, but chiefly in consequence of their enlarged views and exertions as fathers and legislators. It strikes me that it would be impossible for women to stand in higher estimation than they do here [in America]. The deference that is paid to them at all times and in all places has often occasioned [in] me as much surprise as pleasure . . . and as their education shall become more and more the concern of the state, their character may aspire in each succeeding generation to a higher standard.[25]

As for dress, men were giving up wigs and powder and exchanging breeches and silk stockings for pantaloons. Women were also wearing more practical and modest attire. As one observer wrote: “Their light hair is tastefully turned up behind in the modern style and fastened with a comb. Their dress is neat, simple and genteel, usually consisting of a printed cotton jacket with long sleeves, a petticoat of the same, with a colored cotton apron or pin cloth without sleeves, tied tight and covering the lower part of the bosom. This seemed to be the prevailing dress in the country places.”[26]

In the political sphere, America proudly took ownership of their system of government in a way Europeans never did. “He’s our president,” “our governor,” “our senator,” US citizens would often say. The love of family, liberty, individuality, democracy, majority rule, and equality were very real fruits of a young America. There exuded a strong feeling of independence, a reverence for the power and sovereignty of the people and their beloved Constitution bordering on religious fervor. As Tocqueville put it, “Nothing struck me more forcibly than the general equality of condition among the people,” a people “eminently democratic” seeking “heaven in the world beyond . . . and liberty in this one.”[27] Indeed, many interpreted the death of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams on the very same day, 4 July 1826, as a “palpable sign of divine favor,” a country called of, and created by, Providence.[28] The new nation was the political showcase of the world, and Americans never stopped talking about it. America was coming into her own and, in Clay’s words, “gaining that height to which God and nature have destined it.”[29]

“We Never Had So Ominous a Question”: The Missouri Compromise of 1819–21

Yet ever lurking beneath these times of good feelings and positive advancement was the loathsome legacy of slavery—America’s shadow in the sunlight. It was countenanced by the Founding Fathers as a necessary evil; increasingly condemned by the North, which viewed it as a stain upon America’s conscience; and ever more rigorously defended by the South as a property right protected in the Constitution.

The antebellum South had a mind of its own, a culture and character very distinct from that of the northern states. While it is true that tens of thousands of people in Virginia and the Carolinas were moving westward in parallel migrations to those in the North, their destinations were usually to the more southerly regions of Arkansas, Mississippi, Texas, and Missouri, where they hoped to perpetuate their unique way of life. Most were also lower middle-class farmers in search of richer opportunities. One Missouri observer in 1818 counted over one hundred persons a day, for many days in succession, passing through St. Charles, Missouri. He saw a train of “nine wagons harnessed with four to six horses. We may allow a hundred cattle, besides hogs, horses, and sheep, to each wagon; and from three to four to twenty slaves. The whole appearance of the train, the cattle with their hundred bells; the negroes with delight in their countenances, for their labors are suspended and their imaginations excited; the wagons, after carrying two or three tons, so loaded that the mistress and children are strolling carelessly along . . . the whole group occupies three quarters of a mile.”[30]

The climate was hotter and the pace of life slower in the South. If more committed to church attendance and Bible reading, the South was less open to rapid change and unfriendly to novelties in law and technology. Less affected by the rapid rise in European emigration, the South was fiercely individualistic. It proudly preserved its ancestral ties, where family honor, dignity, and moral conduct led to an unwritten code of honor that, as we have already seen with Clay, sometimes led to the fatal custom of dueling to retain the good opinion of one’s equals. There was in the South a strong streak of violence and an unwritten law of vigilante justice to address old grievances and simmering arguments.

Since the invention of the cotton gin in 1793 and the rise of “King Cotton,” the lower South had witnessed a growing number of plantation owners, along with an increase in tobacco growers, both of which demanded increased slave labor. As W. J. Cash has argued, “It was actually 1820 before the plantation was fully on the march, striding over the hills of Carolina to Mississippi.”[31] In the mind of the South, slavery was essential to its economic well-being and a property right guaranteed under the Constitution. Such views led to a prevailing political philosophy that put a premium on states’ rights and sectional interests. Southern interests of the state were above those of the nation, and the true power of the country lay in the individual states’ consenting to a confederation of all the other states. Residing in the sovereignty of such states’ rights was the ultimate legal authority and constitutional provision to secede—that the creators were greater than the creation. No consortium of other states or prevailing popular opinion elsewhere could overrule the conviction or rights of any one state. Abraham Lincoln’s later vision of an indissoluble union was not the Southern view. The South had imposed its limitation on a new national membership from the beginning.

With the British abolition of the slave trade in 1807, through the work of William Wilberforce (see chapter 8) and the eradication of slavery in the North (New York abolished slavery in 1817), the number of newly enslaved blacks brought to America declined. However, interstate slave trade and illicit slave smuggling activities increased into a thriving business, with many plantation owners purchasing as many enslaved people at auction as possible, even renting enslaved people from other owners on a seasonal or monthly basis. Long lines of chained slaves could be heard mournfully singing and trudging along the dusty Southern roads under a hot summer sun.

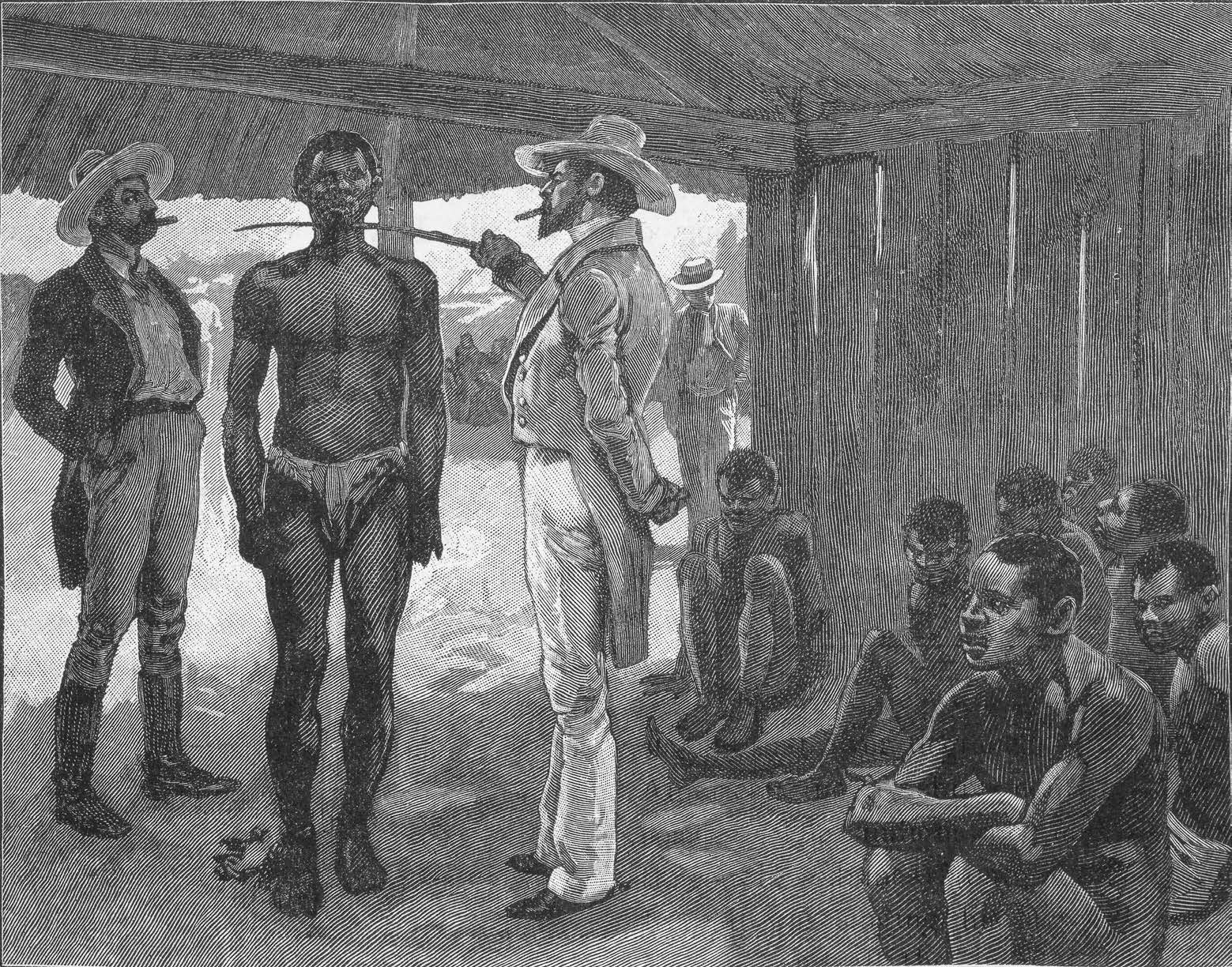

Slave auctions occurred regularly in many major cities and presented such a sight that few outsiders could refrain from describing them. “The usual process differs in nothing from that of selling a horse,” wrote one observer. “The poor object of traffic is mounted on a table, intending purchasers examine his points, and put questions as to his age, health, etc. The auctioneer dilates on his value, enumerates his accomplishments, and when the hammer at length falls, protests in the usual place that poor Sambo has been absolutely thrown away. When a woman is sold, he usually puts his audience in good humor by a few indecent jokes.”[32]

Buying Slaves, Havana, Cuba, 1837, in Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch, ed., The Story of the Sea, 2:440. Courtesy of Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora.

Buying Slaves, Havana, Cuba, 1837, in Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch, ed., The Story of the Sea, 2:440. Courtesy of Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora.

Slaves were often treated as chattel and separated from family members, not allowed or encouraged to marry, and forbidden from going to church or gaining an education. They were treated unkindly or kindly depending on the attitudes of their owner and his family. Slave communities worshipped in “hush harbors,” densely forested areas away from the plantations, to shield their secret religious meetings.[33] There were, of course, both good and bad masters, but the incidents of abuse—the floggings, lynchings, tortures, dismemberments, and other forms of inhuman treatment—left a scar and a stain so deep and profound on the American conscience that not even a future Civil War could remove it.

The spirit of America in 1820, with respect to the “peculiar institution” was one of accommodation, not emancipation. While there was a rising spirit of indignation in the North, the nation was too young, tender, and unprepared for a national conflict. The nation’s collective social conscience had not yet reached a strong enough point to take on the evil of slavery. Resolving that issue was a horror reserved for a later generation.

As early as 1790, Southern congressmen like William Smith of North Carolina were stoutly condemning Northern arguments, petitions, and memorials to limit or abolish slavery. Smith saw such as attacks on the integrity of the South that represented a spirit of persecution. It was not the business of the Quakers, abolitionists, or any other antislavery Northern voices “to be busy bodies above their stations.” Claiming that enslaved Africans were “an indolent people, improvident, adverse to labor” and, if emancipated, “would either starve or plunder,” Representative Williams argued that “the Northern states knew that slavery was so ingrafted into the policy of the Southern States, that it could not be eradicated without tearing up by the roots their happiness, tranquility, and prosperity; that if it was an evil, it was one for which there was no remedy.”[34]

In 1790 the country counted 697,000 slaves and a “free colored population” of 59,000, the majority of whom lived in the North. Thirty years later, in 1820, those numbers had dramatically increased to 1,538,000 and 234,000 respectively.[35]

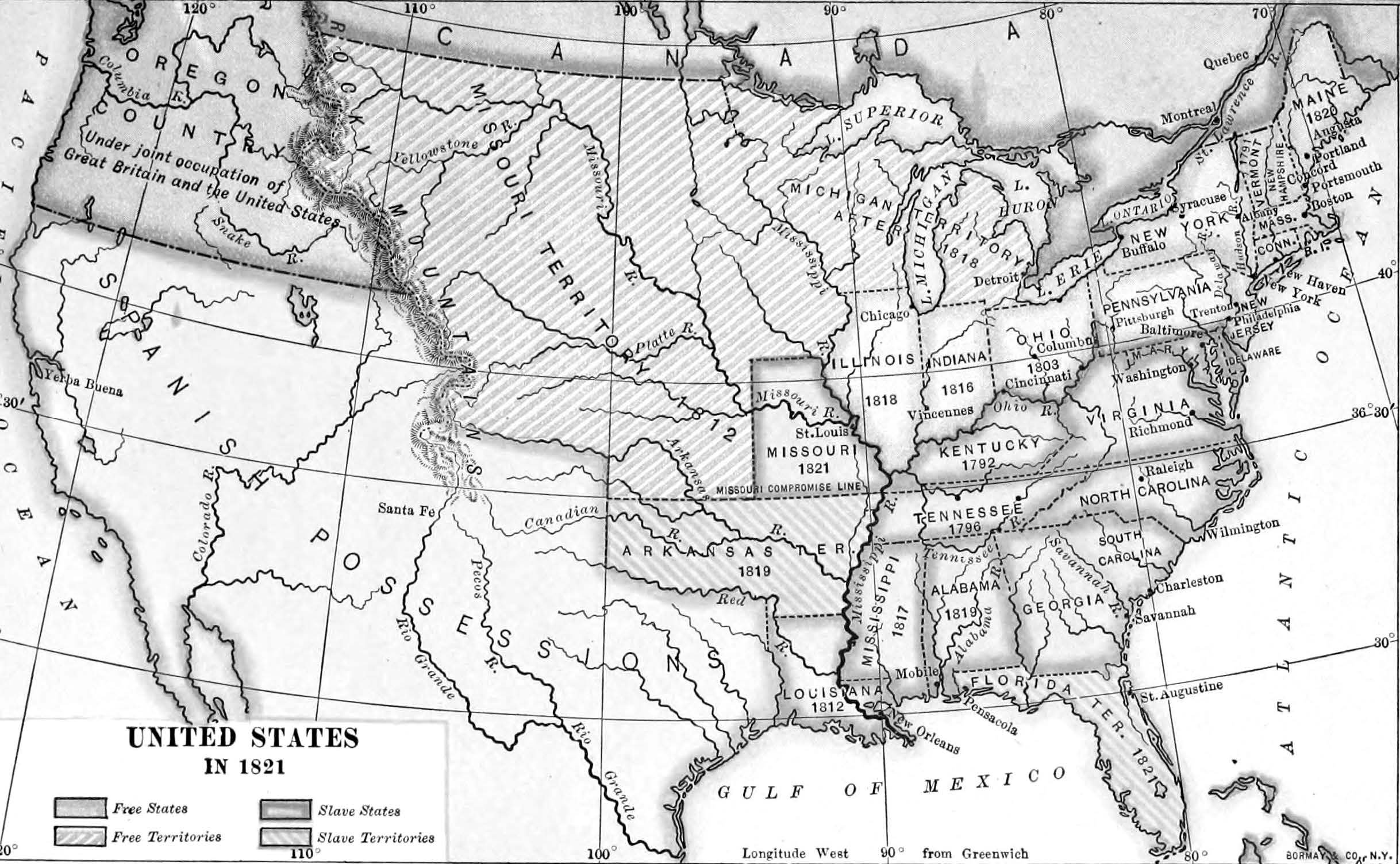

The admission of the several new states of the Union between 1790 and 1819 was a careful regional or sectional balancing act between slave and non-slave states. This was a deliberate attempt to maintain the status quo and provide the South equal representation—if not in the House of Representatives, whose members represented a population growth more rapid in the North, then certainly in the Senate, where each state, small or large, was guaranteed two senators under the Constitution.

This sectional balance, allowing for parity in the Senate, was achieved by the careful balancing act of accepting new states into the Union in a “their turn, our turn” manner (see table).

State Admissions into the Union, 1790–1819

| Northern States | Southern States |

| Vermont (1792) | Kentucky (1792) |

| Ohio (1803) | Tennessee (1796) |

| Indiana (1816) | Louisiana (1812) |

| Illinois (1818) | Mississippi (1817) |

| Maine (1820) | Alabama (1819) |

Table. From Dan Elbert Clark, West in American History, 178.

The Territory of Missouri had been experiencing a rapid influx of settlers almost from the time Jefferson had signed the Louisiana Purchase. Most of them were streaming in from the Carolinas, Virginia, and other Southern states, and some were bringing their slaves with them. By 1820, several thousand slaves were living west of the Mississippi.[36] Jackson County and other areas in western Missouri had already gained the nickname “Little Dixie.”

The United States in 1821. From Mowry and Mowry, Essentials of United States History.

The United States in 1821. From Mowry and Mowry, Essentials of United States History.

When the Territory of Missouri gained sufficient population, it petitioned Congress for statehood in January 1818, and most observers anticipated it would enter as a slave state. The trouble was, as shown in table, that after Alabama had entered the Union in 1819, it was the North’s turn to have a free state admitted. More to the point, a rising, ever louder, and more persistent antislavery sentiment in the North demanded an end to slavery, whatever the cost, due to their fear that slavery would extend far into the reaches of the Louisiana Purchase. To the North’s way of thinking, slavery should never be allowed to extend west of the Mississippi River.[37]

The matter included more than whose turn it was to add a state or even the morality of slavery. Slavery was also seen as a constitutional issue. Was it the prerogative of Congress and the national government to determine whether an incoming state should be slavery friendly, or was it the right of those residing there to decide for themselves? Opponents of slavery argued that because Missouri was still a territory and not a state, it was subject to the control of Congress. After all, if Congress had previously legislated that no state carved out of the North-West Ordinance could come in as slave states, why could it not do the same in the Louisiana Purchase country?

Representative James Tallmadge of New York opposed the admission of Missouri as a slave state. Riding the rising humanitarian impulse sweeping over the North, Tallmadge proposed an amendment that would halt the importation of slaves and free the children of slaves already in the United States at age twenty-five. On the failure of this motion, another New York representative, John W. Taylor, fearing that if slavery were allowed in Missouri it would spread throughout the West “with all its baneful consequences,”[38] proposed something of a compromise. His motion allowed for the allowance for slavery in Missouri and west of the Mississippi River but forbade it in those regions or territory north of latitude 36° 30¢ (a line westward corresponding to the southern border of Missouri).[39] To Northerners, the chief objection to Missouri’s admission as a slave state was that it was in the same latitude with Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Stalled in conflict, Congress recessed without a resolution to the ongoing debate.

The acrimony engendered over the matter of Missouri can hardly be overstated. The South saw it as a Yankee conspiracy. “The Missouri question,” wrote an aging Jefferson, “is a breaker on which we lose the Missouri country by revolt, and what more God only knows. From the battle of Bunker Hill to the Treaty of Paris, we never had so ominous a question.”[40] John Quincy Adams, fearful that the present question was but “a preamble—a title page to a great tragic volume,” recorded in January 1820 that “the Missouri or slave question . . . is beginning to shake this Union to its foundations.”[41] Between sessions of Congress, public meetings were held all over the South and the North, and passions on both sides were running dangerously high.

When Congress reconvened in December 1819, during the severe economic depression discussed earlier, a new twist developed: Massachusetts consented to a division of its land mass, which allowed Maine to be admitted into the union as a new free state. To this proposition, the South agreed, so long as Congress would allow Missouri in as a slave state. When the North refused on matters of principle, Southern representatives became ever more indignant, ever more bitter. “If you get Maine, why not Missouri for us?” came the Southern response. “If peace did not come, war would, and that soon.”[42]

While outnumbered in the House, the South voted down almost every resolution in the Senate. The Senate united Maine and Missouri on the same bill and on the same terms, without any restriction upon slavery. Senator Jesse B. Thomas of Illinois then inserted the 36° 30¢ clause proposed by Representative Taylor the year before. The House originally rejected the combination of Maine and Missouri in one bill but gradually gave way, and a committee of both houses of Congress reached a tentative compromise. President James Monroe signed the bill, allowing Maine admittance as the twenty-third state of the Union on 3 March 1820, and Missouri, once its constitution had been approved by Congress, was to follow shortly thereafter. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 was now assured—or was it?

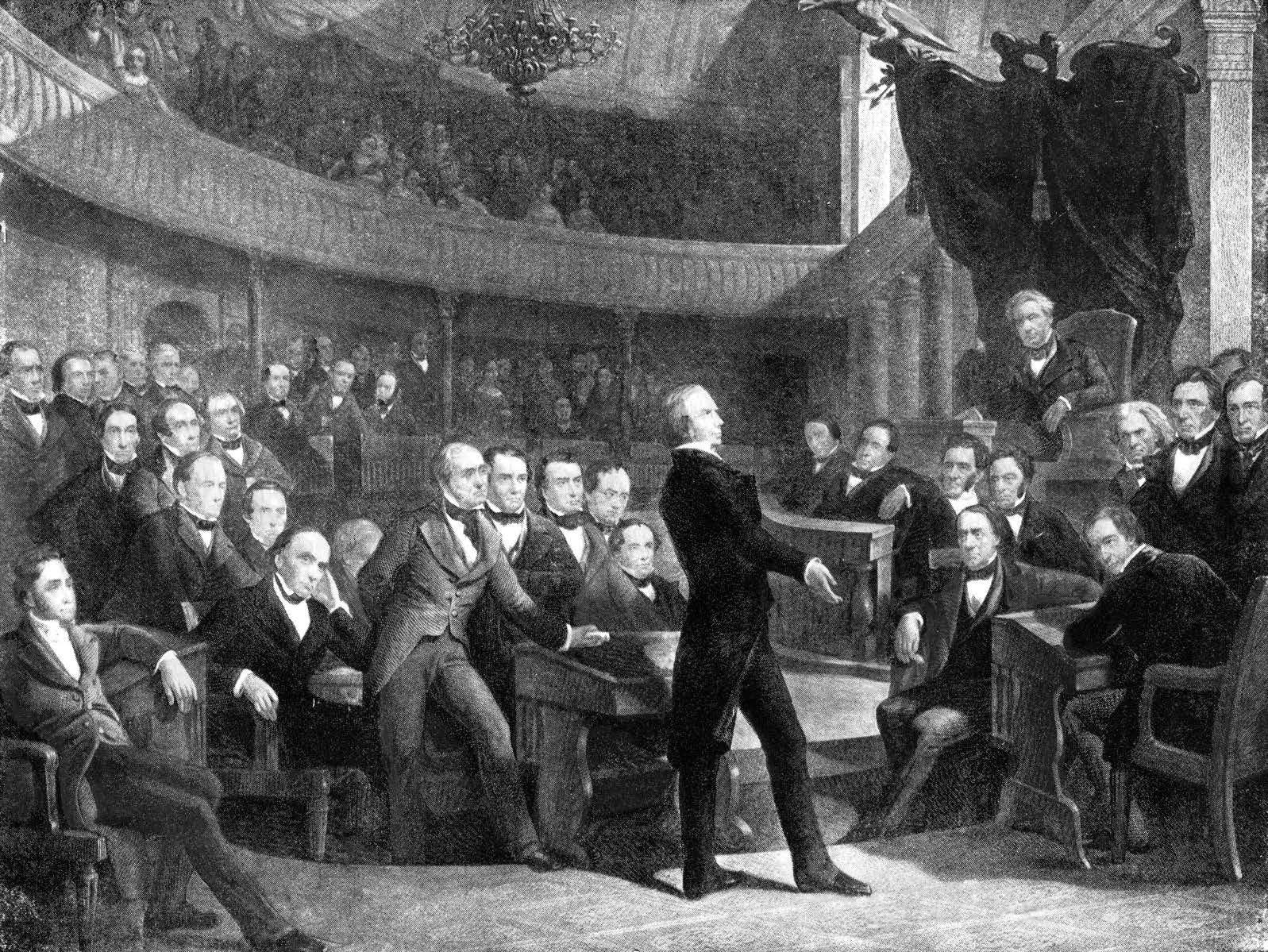

Senator Henry Clay Speaking about the Missouri Compromise in the Old Senate Chamber, by unknown artist.

Senator Henry Clay Speaking about the Missouri Compromise in the Old Senate Chamber, by unknown artist.

Like a recurring nightmare, the conflict unfortunately erupted all over again and more loudly than before when the Territory of Missouri, either in a mood of spiteful defiance or shameful ignorance of the prevailing national sentiment, adopted a state constitution that denied citizenship rights to free blacks. Southern extremists called for immediate admission, while many Northerners desperately urged rejection of the state, constitution, and compromise. As Clay put it, “The flame which had been repressed during the previous session now burst forth with double violence.”[43]

The debate revealed one of the fundamental causes of the entire controversy. As Glover Moore has well argued, “The desire of each great section of the nation [was] to spread its own type of civilization over the western country and appropriate the resources of the West for its own use.”[44] It would take a man of towering intellect, courage, and political skills; one who had the ear and trust of politicians from both North and South; and one whose whole soul was bound up in the cause of the Union to untie the Gordian knot of Missouri’s claim for admission into the Union.

“I Know No South, No North, No East, No West”: The Great Compromiser

As Speaker of the House of Representatives from 1811 to 1820 and again from 1823 to 1825, Henry Clay, “the Great Pacificator,” continued his own style of pragmatic Republicanism. He sought to create an American System, which would provide protection for business in the form of higher tariffs, a stronger military, a national bank, continued westward expansion, and a deep distrust of postwar Europe. Like Jefferson, he had been a strong supporter of the French Revolution and many of Napoléon’s liberal policies and firmly believed that the Congress of Vienna, in seeking to restore constitutional monarchies, was “destructive of every principle of liberty.” With the French monarchy restored, America was, he believed, now the only real bastion of liberty.[45]

Clay was also the most conversant and well-informed American politician in the doings of Simón Bolívar, San Martin, and the independence movements of South and Central America. He ardently believed that it was in America’s best interest to do all it could to aid the revolutionary spirit then fanning across South America, and he constantly called upon Congress to render financial aid to their brothers in arms (see chapter 9). He believed, as one scholar has argued, that “continued Spanish dominion over Latin America was . . . a danger to the security of the United States, an impediment to possible trade relations, an affront to republican ideals, and probably of highest magnitude, a detriment to hemispheric influence.”[46] He saw enormous trade opportunities in the Caribbean and with South America and believed the two continents could combine to form a counterpoise against European imperialism. Though eventually a supporter of the Monroe Doctrine, Clay overextended himself in attacking Monroe and secretary of state John Quincy Adams in their more reasoned approach toward recognizing the emerging Spanish independencies. Yet there is no doubt that his fiery speeches emboldened Bolívar in his revolutionary efforts against Spain. As Clay said in 1816, “It would undoubtedly be good policy to take part with the patriots of South America.”[47]

It was as Speaker of the House that Henry Clay forged a brilliant political career while leaving an indelible impression upon the functions of Congress. Ronald M. Peters has well argued that Clay was “the first strong Speaker” who carved a role for himself that has found no imitation in American history.[48] By dint of his own forceful personality, he demanded respect—and earned it. Even the boisterous and argumentative John Randolph of Virginia, who was an ardent proponent of slavery, highly regarded Clay. There was something in his voice and oratory, his honest, friendly demeanor, his courtesies and congeniality, his boldness, his respect for differing, even warring opinions, his earnest convictions, and his charismatic popularity that continually won the support of his colleagues in the House. It was more his winning and engaging personality and less his skills as a parliamentarian that made him so attractive. Ever more popular personally than the policies he espoused, Clay was never censured by the entire House or was found to be out of order.

One particularly astute British female observer had this to say of Clay at the height of the debate, “He seems, indeed, to unite all the qualities essential to an orator: animation, energy, high moral feeling, ardent patriotism, a subliminal love of liberty, a rapid flow of ideas and of language, a happy vein of irony, an action at once vehement and dignified, and a voice full, sonorous, distinct, and flexible . . . without exception the most masterly voice that I ever remember to have heard. . . . In conversation he is no less eloquent than in debate.”[49]

The fact that he was from the South and that he owned slaves of his own back in Ashland, endeared him to his Southern colleagues. Yet Clay was known for his temperate, antislavery sentiments, including his “gradual emancipationist” views. These views included either sending slaves back to Africa (he was president of the American Colonization Society for years) or having the government buy freedom for the slaves gradually from their masters. He opposed slavery, but not at the cost of the Union.

He had many Northern admirers as well because of his pro-federalist stance in promoting higher tariffs, improving roads and bridges, and instituting the National Bank, a measure he pushed through Congress in 1816 to the discomfort of his fellow Republican colleagues. He was respected by friend and foe alike because he saw the value in all sides of almost any argument. The ideals of liberty and union were more important to him than ideology. Admitted John Quincy Adams, who often disagreed with his Kentucky colleague: “Clay is an eloquent man, with very popular manners and great political management. He is, like almost all the eminent men of this country, only half educated. His school has been the world, and in that he is proficient. His morals, public and private, are loose, but he has all the virtues, indispensable to be a popular man.”[50] He was, in short, the right person at the right time, with the right blend of philosophy, personality, background, and political skill.

His success as Speaker and as the eventual broker of the Missouri Compromise owed much to his organizational and political skills. From the beginning, the House of Representatives had several standing committees, but they were not yet well developed. There were few fixed assignments and members often switched from one to another. Membership turnover on committees was high. Clay greatly expanded the number of both standing and select or specialized committees to handle the ever-increasing burden of new legislation. It can be argued that the standing committee system is a monument to Clay’s efforts to mobilize the House.[51] He had an uncanny ability to put the best talents and interests of his colleagues to work most efficiently at a time when party politics were more regional and less ideologically rigid as today—even when he knew their politics and desired outcomes might very well differ from his own.[52] And they admired and respected him because of it. In short, he knew how to govern through committees and how to reach consensus out of argument, and he invented as many new committees as necessary to solve the problem at hand.

Such was the diplomatic magic he brought to bear to the Missouri Compromise debate, particularly on what scholars later termed the “Second Compromise of 1821,” when the debate renewed after Missouri came back with that objectionable constitution. Even though Clay was not then Speaker, having temporarily resigned to take care of financial problems back home in Ashland, he was still the most influential member of the House. He clearly and unmistakably saw the nature and deep peril in the debate at hand. All looked to him for a resolution. He begged and beseeched, with all his powers of persuasion, for all to compromise. And then he put his organization skills to work. If one joint committee of thirteen from both the House and Senate failed to break the impasse, he requested another, this time of twenty-three. Gradually and with great patience, like a mother with squabbling children, he won over his colleagues. All were given voice; all were respected by Clay as committee chairman. Said Clay: “I am for something practical, something conclusive, something decisive upon this agitating question, and it should be carried by a good majority. How will you vote, Mr. A.? how will you vote, Mr. B? how will you vote, Mr. C?”[53] Reducing the logjam to its simplest common denominator—a skill few others could imitate so often and so well—Clay finally put it thus: “Shall not Missouri be admitted into this Union on an equal footing with the original states in all respects whatever so long as the Constitution of the United States is paramount over the local Constitution of any one of the states of the Union?”[54]

Who could disagree with such a resolution? This second compromise was, therefore, achieved on 2 March 1821. The pledge was secured, and on 10 August 1821, Missouri became the United States’ twenty-fourth state. Such was the work of the Great Compromiser, who believed that “the art of politics consists only in the possible.”[55]

Conclusion

Henry Clay served as senator from Kentucky for most of the rest of his life. As ambitious as he was respected, Clay never attained his long-sought prize of the presidency, despite the fact he ran for the post three different times in 1824, 1832, and 1844. He came closest when he lost to John Quincy Adams in 1824 who then appointed him in what some felt was an act of collusion as his Secretary of State. Riding a tide of anti-banking democratic anger, Jackson was elected in 1828. Then in 1832, Clay suffered his worst loss in 1832 to his old nemesis “Old Hickory,” who was then up for reelection, one of the few men Clay thoroughly distrusted personally and utterly despised politically, as one unfit for the presidency. Clay, however, lacked Jackson’s populist instinct, his democratic impulse, and underestimated Jackson’s appeal to rural America. Jackson’s dismantling of the National Bank of the United States in 1834, his harsh Indian Removal policies, and his contempt of the “American System” of higher tariffs, internal improvements and his imperious nature were all anathema to Clay.

Next to Jackson, if there was another man in Congress Clay resisted the most, it was John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, not on account of his personality—they got along reasonably quite well—but because of his ideology. Calhoun was the embodiment of the principle of states’ rights to the point, as seen in the Nullification Crisis of 1833, that states’ rights were more important that the preservation of the Union. To this viewpoint, Clay could never agree. His stand on the preservation of the Union later earned him the accolades of a new Congressman from Illinois—Abraham Lincoln.

He may have shown ambivalence towards the slavery question, as James Klotter and others have well argued, but the essential point to make is that at center, Clay stood firmly for the preservation of the Union. “Union was his motto; conciliation his maxim.”[56] “I know no South, no North, no East, no West,” he said on another occasion.[57] And, where at all possible, war must be avoided. Once a war hawk, he had witnessed firsthand the terrible cost to the nation the War of 1812 had been and how costly, ruinous, and totally unpredictable wars could be. Truth is, he feared a civil war and what the unknown results of it might be. “If there be any who want civil war . . . I am not one of them. I wish to see war of no kind; but, above all, I do not desire to see civil war.” He continued:

When war begins, whether civil or foreign, no human sight is competent to foresee when, or how, or where it is to terminate. But when a civil war shall be lighted up in the bosom of our own happy land, and armies are marching and commanders are winning their victories, and fleets are in motion on our coast; tell me, if you can, tell me, if any human beings can tell the duration. God alone knows where such a war would end. In what a state will our institutions be left? In what state our liberties? I want no war; above all, no war at home.[58]

The question of Missouri is probably more relevant to the Latter-day Saints than almost any other Christian denomination in America for in Joseph Smith’s budding theology Independence, Jackson County, Missouri was to be the center stake of Zion, where thousands were to gather in imminent expectation of the Second Coming of Christ. If Missouri had become part of a new Southern confederacy in the early 1820s, could a church then made up predominantly of northerners and not a few abolitionists have thrived in such a place?

Fact is, Latter-day Saints encountered enormous problems in Missouri when it was part of the Union. As historian Stephen Le Sueur has well shown, the fundamental causes for the Mormon-Missouri conflict were multiple but certainly included religious incompatibilities and prejudices; a restless anxiety that the Saints, as predominantly northerners, would inevitably tamper with the “peculiar institution” of slavery; a lingering suspicion that they would stir up, if not align themselves with, the Indian tribes whom the Saints regarded were of the House of Israel; a resentment of Mormon-style economics with its emphasis on consecration and internal trade; and finally, a fear that the Saints would “dominate local politics to the exclusion of all non-Mormons.”[59] Had war broken out and had the South won that war, such fears and suspicions would very likely have been even further exacerbated. Furthermore, if the South had seceded in 1820 and if war had followed, what impact would such events have had on missionary work, on the gathering, and on the entire mission of the Church? Admittedly, these are impossible questions to answer, but this chapter has tried to show that Henry Clay had so developed his unique talents and political skills that he played a pivotal role in the preservation of the Union in 1820, which preservation was likely very beneficial to the cause of the Restoration.

Missouri finally came into the Union in 1821, and America was spared a Civil War for over forty years in large measure because of the statesmanship of Henry Clay. Trusted by both North and South, respected in both the House and the Senate, and revered by millions, the Great Compromiser has been overlooked and underappreciated in American history. He not only forged the Compromise of 1820–21 but also helped dissolve the Nullification Crisis of 1832-33 and brokered yet another compromise between bitter factions in 1850. The forces of enmity and irreconciliation eventually overwhelmed his efforts at peaceful resolution, but for our time and age he represents the best in American politics—a nation-building age of hope and optimism.

Notes

[1] Henry Clay, 10 May 1820, in Colton, Life, Correspondence, and Speeches of Henry Clay, 5:243.

[2] Moore, Missouri Controversy, 1.

[3] Abridgment of the Debates of Congress, from 1789 to 1856, 16th Congress, 1st Session, Senate Papers, 6:400.

[4] As cited in Jones, “Henry Clay and Continental Expansion, 1820–1844,” 244.

[5] From a speech by Mr. James Tallmadge (New York), 16 February 1819, 15th Congress, 2nd Session, House of Representatives, Debates of Congress, 6:351–52.

[6] Howe, Life and Letters of George Bancroft, 75–76. See also Nye, George Bancroft, 45.

[7] From a speech by Henry Clay in the U.S. Senate, 7 February 1839, in Colton, Life, Correspondence, and Speeches of Henry Clay, 6:157.

[8] As cited in Cunliffe, The Nation Takes Shape, 70.

[9] Remini, Henry Clay, 6.

[10] Remini, Henry Clay, 9.

[11] Remini, Henry Clay, 9–10.

[12] Van Deusen, Life of Henry Clay, 25.

[13] Remini, Henry Clay, 20.

[14] John Quincy Adams, Memoirs, 1:44, in Van Deusen, Life of Henry Clay, 46.

[15] Josiah Quincy, Life of Josiah Quincy, 259, in Remini, 413.

[16] Channing, United States of America, 189. For the most recent study of the ward 1812, see Alan Taylor, Civil Ward 1812.

[17] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1:303.

[18] Letter XVI, September 1819, in Wright, Views of Society and Manners in America, 150.

[19] Mesick, English Traveller, 73–75.

[20] Boorstin, Americans, 91.

[21] Clark, West in American History, 173.

[22] Clark, West in American History, 175.

[23] Mesick, English Traveller, 190–96.

[24] Letter XIII, September 1819, in Wright, Views of Society, 123.

[25] Letter XXIII, March 1820, in Wright, Views of Society, 218–19, 221.

[26] Mesick, English Traveller, 2:323.

[27] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1:3, 43, 46.

[28] Boorstin, Americans, 387.

[29] Van Deusen, Life of Henry Clay, 109.

[30] Clark, West in American History, 175.

[31] Cash, Mind of the South, 10.

[32] Hamilton, Men and Manners in America, 2:216, as cited in Mesick, English Traveller, 139–40.

[33] Hucks, “Black Church,” in Encyclopedia of American Cultural and Intellectual History, 1:230.

[34] Joseph Gales, debate of 17 March 1790, in The Debates and Proceedings in the Congress of the United States, 2:1503–4.

[35] DeBow, Statistical View of the United States, 63, 82.

[36] See Moore, Missouri Controversy, chap. 1.

[37] Williams, Historian’s History of the World, 23:347–50.

[38] Moore, Missouri Controversy, 42.

[39] It was generally understood that cotton could not grow north of latitude 36°.

[40] Recited in Williams, Historian’s History, 348.

[41] Adams, Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, 5:502, 505.

[42] Williams, Historian’s History, 348.

[43] Colton, Life, Correspondence, and Speeches of Henry Clay, 3:334.

[44] Moore, Missouri Controversy, 49.

[45] Van Deuson, Life of Henry Clay, 117–18.

[46] Wilkinson, “Henry Clay and South America,” 15.

[47] Wilkinson, “Henry Clay and South America,” 16.

[48] Peters, American Speakership, 31–34.

[49] Letter XXVIII, Washington, DC, April 1820, in Wright, Views of Society and Manners in America, 262–63.

[50] Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, 5:325.

[51] Peters, American Speakership, 38.

[52] Peters, American Speakership, 38.

[53] Colton, Life, Correspondence and Speeches of Henry Clay, 3:336.

[54] Colton, Life, Correspondence and Speeches of Henry Clay, 3:337.

[55] For an excellent, succinct study on this topic, see Lightfoot, “Henry Clay and the Missouri Question,” 143–65.

[56] Klein, “Henry Clay, Nationalist,” 229.

[57] Klein, “Henry Clay, Nationalist,” 238.

[58] Register of Debates, 22nd Congress, 2nd Session, 472, as quoted in Klein, “Henry Clay, Nationalist,” 213.

[59] LeSueur, 1838 Mormon War in Missouri, 17. See also Alex Bough, Call to Arms.