Théodore Géricault, Romantic Artists, and The Raft of the Medusa

Richard E. Bennett, “Theodore Gericault, Romantic Artists, and the The Raft of the Medusa,” in 1820: Dawning of the Restoration (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 105‒24.

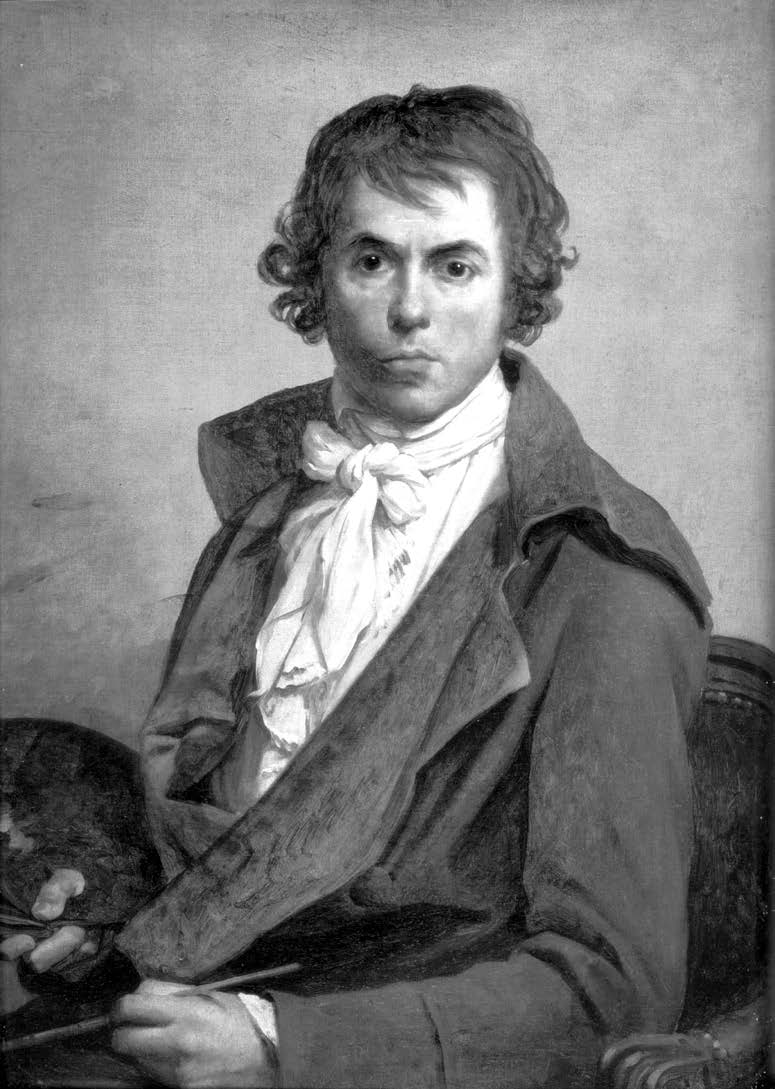

Théodore Géricault. Jean-Louis-André-Théodore Gericault, by Horace Vernet.

Théodore Géricault. Jean-Louis-André-Théodore Gericault, by Horace Vernet.

Beethoven was not the only one gifted with artistic genius that revolutionized the world. There were other “earlier lights” in the morning of the Restoration whose genius and talent have stood the test of time and who expressed themselves in light of the revolutionary ideals of liberty with a certain newfound freedom of expression. [1] This chapter will examine such a person, a deeply tormented soul whose paintings of suffering and portraits of madness nonetheless speak of hope, rescue, and the indomitable spirit of humankind. His life—and death—will provide us with yet another vantage point to view the age of 1820, this time from the painter’s brush.

The aspiring twenty-six-year-old French artist Jean-Louis André Théodore Géricault read the tragic story of the loss of 150 passengers of La Méduse soon after his return to Paris in September 1817 after a yearlong visit to Italy, where he had systematically studied the paintings of Michelangelo, Raphael, and several other leading Renaissance painters. What baited his interest even more than the tragedy itself was the French Bourbon government’s attempt to cover up the whole affair. It became Géricault’s mission to expose the tragic episode.

On 2 July 1816, the French frigate La Méduse, flagship of a convoy carrying soldiers and settlers to the colony of Senegal on Africa’s west coast, ran aground on the reefs of Arguin, an island off the coast of Mauritania. Two hundred fifty of the ship’s four hundred passengers and crew, including the cowardly captain, crowded onto six lifeboats, leaving the unfortunate others to fend for themselves on a makeshift raft. This crude floating device, made from the ship’s masts and beams that those left behind had hurriedly lashed together, measured sixty-five feet long by twenty-eight feet wide. As these unfortunate 150 castaways, including one woman, were herded onto the slippery beams, the raft sank at least three feet below the surface of the sea under the weight of the panic-driven assembly. Sensing that the weight of the raft would drag them under, those in the lifeboats cut the towing ropes, leaving the heaving raft and its doomed passengers to the mercies of the wind-tossed Atlantic.

That first nightmare at sea served as notice of the calamities that awaited them. The ship’s surgeon, Jean Baptiste Henri Savigny, one of the mere handful who survived the horrors of the “raft of the Medusa,” recalled the following: “A great number of our passengers who had not a seaman’s foot tumbled over one another; after ten hours of the most cruel sufferings, day arrived. What a spectacle! . . . Ten or twelve unfortunate creatures having their lower extremities entangled in the interstices left between the planks of the raft, had been unable to disengage themselves, and had lost their lives. Several others had been carried off the raft by the violence of the sea, so that by morning we were already twenty fewer in number.”[2]

Come daybreak, panic ensued as all hands pushed to the center of the raft, and several mutinied against the officers among them, throwing several overboard before they, in turn, were quieted by the charge of surviving armed soldiers. Sixty-five more died that second day. By the third day, weakness, fatigue, and raw hunger had driven the remaining survivors to that basest act: “Those whom death had spared in the disastrous night which I have just described threw themselves ravenously on the dead bodies with which the raft was covered, cut them up in slices which some even that instant devoured. A great number of us at first refused to touch the horrible food; but at last . . . we saw in their frightful repast our only deplorable means of prolonging existence; and I proposed . . . to dry these bleeding limbs in order to render them a little more supportable to the taste.”[3]

This dreadful scene of hunger, thirst, and insanity repeated itself day after weary day until by the sixth day at sea only twenty-eight survivors remained. When there was too little drinking water left, the strongest resolved to practice survival of the fittest by throwing their weaker comrades into the sea in a blatant act of murder.

The fifteen ruthless men now in sole command of the raft managed to survive another seven days when, on the morning of 17 July, after virtually all hope for rescue had been lost in an abject spirit of delirium and despair, “Captain Dupont, casting his eye towards the horizon, perceived a ship, and announced it to us by a cry of joy; we perceived it to be a brig, but it was at a very great distance; we could only distinguish the top of its mast. The sight of the vessel spread amongst us a joy which it would be difficult to describe. . . . We did all we could to make ourselves observed; we piled up our [wine] castes, at the top of which we fixed handkerchiefs of different colours.”[4]

When, however, the distant ship disappeared over the horizon, the shipwrecked crew members fell in utter despair and lay down together in a makeshift tent, which they had rigged beneath the mast to await an almost certain death. To their disbelief, two hours later, the ship Argus of the original convoy sent out to search for survivors returned, miraculously spotted them, and turned sail for their deliverance. Of the fifteen starving, sunbaked men rescued from the raft, five died soon afterward, leaving only ten to tell the sordid tale.

Géricault could hardly have chosen a topic more in tune with his own inclinations to the violent and the macabre, his own self-condemnation and guilt over a tortured love affair, and his own artistic talent for painting scenes of grandeur in the neoclassical style. A colossal painting that mirrored Géricault’s inner talent and distress, a masterpiece of political art that captured the decline of Napoléon’s military power, and a robust transitional piece of Romantic art, The Raft of the Medusa continues to elicit critical acclaim. In fact, Géricault’s life and his many other works have been eclipsed by the very grandeur of this one enduring, monumental piece. This enormous painting, which is sixteen by twenty-four feet and still on display on the walls of the Louvre in Paris, speaks to the universal themes of suffering and death, tragedy and triumph, hopelessness and redemption.

A Self-Taught Artist

Géricault was born 26 September 1791 in Rouen, France, to forty-seven-year-old Georges-Nicolas Géricault (1743–1826), a wealthy and well-established lawyer, and thirty-seven-year-old Louise-Jeanne-Marie Caruel (1753–1808), who was from a well-known merchant family with connections to the slave trade. He moved with his wealthy parents to Paris when only four years old. There he spent a troubled childhood in the turbulent, terrifying Reign of Terror. What psychological impact the chilling atrocities of the French Revolution and the death of both his mother and father had upon him when he was still relatively young has not been sufficiently analyzed, but his parents left him an annuity that freed him from financial cares for most of his life. He never painted by commission; he was free to paint “fully at the mercy of his temperament.”[5] If not a brilliant student, Géricault was keenly perceptive and blessed with an exquisite talent to draw and a remarkable memory for detail.

During his formative years, he spent days visiting the Louvre and studying paintings of every sort. He also looked forward to vacations with relatives in rural Normandy, where he developed his taste for high-bred horses and a love and skill for horsemanship. Never close to his rather quaint and unimaginative father, who failed to understand his son, Géricault gravitated to his kinder, more affectionate, and much more supportive uncle, Jean-Baptiste Caruel—his mother’s brother. Things were going quite well indeed until Caruel married the young and beautiful Alexandrine-Modeste. It did not take long for Géricault to see in his new aunt the sister he never had and, as time went on, someone much more than that.

His first lessons in art came at the Lycée Impérial at the hands of Pierre Bouillon (1776–1831), a winner of the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1787, an award that provided talented young artists fame and prestige. Soon afterward Géricault decided to travel to Italy to study Renaissance art—a rite of passage for aspiring French artists. There he began visiting the studio of the affable Carle Vernet (1758–1836), who was well known for his remarkable equestrian paintings but who, like most other struggling artists of the day, had accepted commissions from the French Directory to draw glorified paintings of Napoléon and his military conquests. Vernet’s drawings of Napoléon’s Italian campaign had won him acclaim, as did his Battle of Marengo . For his Morning of Usterlitz, Napoléon had also awarded him the Legion of Honour.

Sensing his own developing interests and talents and the need for more earnest artistic training, nineteen-year-old Géricault later enlisted as a pupil of the better-known Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1774–1838), whose 1799 painting Marcus Sextus had earned him fame and a little fortune. Although he studied under Guérin for six months and occasionally thereafter, the independent-minded Géricault would always regard himself as a self-taught artist. After studying the mechanics of monumental painting with Guérin, Géricault studied at the Louvre, where from about 1810 to 1815 he copied the works of Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), Diego Velázquez (1590–1660), and Rembrandt (1606–69). While at the Louvre, he explored a wide range of emotion and choice of subjects common to the budding Romantic school of art that the prevailing classical art forms lacked. And all the while he gave the appearance of “a gentleman-artist, an outsider, by habit and temperament, to the professional world of art.”[6]

Art and the Romantics

Géricault was very much a pioneering product of his time and in company with several other developing Romantic painters and artists. The Romantic impulse in art, as we have already seen in music and will also see in literature, was a self-conscious cultural movement, a highly individualized, emotional reaction to the perceived formalized, rule-bound rigidities of the earlier Enlightenment era. It was a highly popular, more democratic movement of expression than the top-down, aristocratic, state- or Church-commissioned art that had for so long subsidized and dominated the world of art. Although Romanticism was not a religious movement, it was certainly an emotional (some even say spiritual) trend—a deeply moving yearning of the soul and a revolt against the enveloping materialism and increasing mechanization of the industrial age. Marcel Brion, in his study of Romanticism, described its principal elements in terms of feelings—a “feeling for nature, for the infinite and far distant pastures, for solitude, for the tragedy of Being and the inaccessible ideal.”[7]

Admiration for the Gothic had been growing in European art circles since at least 1750. This “medieval revival” soon became widespread, not only in art but also in literature. However, in no small part, Romanticism owed its true beginnings to the French Revolution, which, in overturning the established political, religious, and economic orders of the time, permanently cast doubts on those earlier strains of classical artistic thought and expression. The French and American Revolutions and the Napoleonic Wars all showed the unpredictability of human history and of how humanity reacts in difficult circumstances.

Self-Portrait, by Jacques-Louis David.

Self-Portrait, by Jacques-Louis David.

The Romantic impulse in art viewed men and women as highly emotional as well as rational beings, capable of the grand and the noble as well as the base and the deplorable. Whether they chose to see humanity in positive hues, like Wordsworth, or in more pessimistic strokes, as did Francisco de Goya and Géricault, the Romantics believed in giving full rein to their emotions. To the Romantics, truth was more a subjective than objective reality, and inspiration and emotion were the most dependable arbiters for understanding and capturing life’s moods, ideals, and meanings whether in music, on paper, or on canvas. As another noted scholar succinctly phrased it, “Romanticism sought to express ideals which could be sensed only in the individual soul and lay beyond the bounds of logical discourse.”[8]

The most significant visual interest among the Romantic painters was that of color and illusion. This led many to see painting—in particular the portrayal of the heroic, the picturesque or landscape, the spiritual, and the portraiture—as the quintessential Romantic visual art, far more so than with sculpture or architecture.

Arguably the most famous artist of the age was Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825). Destined to live through the tumultuous times of the French Revolution, the rise and fall of Napoléon’s empire, and the restoration of Bourbon authority, David honed his skill of capturing the defining moments and dominating personalities of his time in majestic, neoclassical style paintings. As astute politically as he was gifted artistically, David managed to survive through a most tumultuous political era.

Having studied in Rome for several years, David understood “the classicing art of the Italian Renaissance,” with its catalogue of pomp and magnificence, and the prevailing sentiment that the highest beauty was Greek art as expressed in the human figure. “Antiquity,” David once said, “has not ceased to be the great school of modern painters, the source from which they draw the beauties of their art. We seek to imitate the ancient artists, in the genius of their conceptions, the purity of their design, the expressiveness of their features, and the grace of their forms.”[9]

Upon returning to France after a temporary, self-imposed exile, David continued his formal training at the Royal Academy of Paintings and Sculpture, created by Louis XIV. Following the standard sequence of training for French schools, David spent long years of drawing from prints, plaster casts of ancient sculptures, and live models. A republican and avid supporter of Robespierre and the aims of the French Revolution, the “Robespierre of the Brush”—as David was sometimes called—was elected to the National Convention, where he acted almost as dictator of art for all of France. After Robespierre’s death in 1794, David spent a year in prison, and upon his release he kept a low profile. Knowing of David’s artistic genius, Napoléon visited his studios before becoming emperor and enlisted his artistic support.

Painting with astonishing clarity, color, detail, and with “personal determination and passion,” David produced heroic historical paintings with stunning, photograph-like style. [10] In demand by republicans, royalists, and emperors alike, David memorialized the Revolution and immortalized Napoléon, bequeathing to the world of art such timeless patriotic classics as Belisarius (1781), Oath of the Moratir (1784–85), The Oath of the Tennis Court (1791), The Death of Marat (1793), Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801), and The Coronation of Napoleon (1806).[11] With the post-Waterloo Bourbon restoration in 1815, David fled to Brussels, where he lived his declining years in exile.[12]

David also encouraged his better pupils to express their own style and individuality. Under David’s direction in 1791, the Salon, an annual public exhibition of paintings at the Louvre, was open to most every artist and not just servants of the state. More than ever before, artists were being commissioned by wealthy sponsors and less by the Church itself. Among David’s more notable disciples was Anne-Louis Girodet (1767–1824), François Gerard (1770–1837), Jean-Germain Drouais (1763–1788), and Jean-Auguste-Dominic Ingres (1780–1867), whose hero-worship painting of Napoleon on His Imperial Throne (1806) stunned even David with its majestic colors and deification overtones.[13] It was in France that the controversy between Romantic art and classicism became “most vociferous,” even violent. Art became the surrogate of political action. Romantic art was a school of painting so aberrant and “full of drama and emotional complexity” that only the word Romantic captures its essence.[14]

The Coronation of Napoleon, by Jacques-Louis David.

The Coronation of Napoleon, by Jacques-Louis David.

One clearly begins to detect the bedrock meaning of Romantic heroic art in the paintings of yet another one of David’s loyal disciples, Antoine-Jean Gros (1771–1835). In his Napoléon on the Battlefield of Eylau (1808), Gros shows not just the conquering Napoléon but also focuses, in the forefront of that painting, on the dead and dying. Attuned more to expressing feelings and raw emotions than to following slavishly the formalities of style, the French Romantics tended to be less worshipful of military and spiritual heroes and more observant of the common soldier, of human suffering, and of the best and worst in humanity, while not abandoning the classical forms of art.[15] They exhibited, as Robert Rosenblum puts it, “a condition of emotional unrest” and explored “new dimensions of irrational experience that are couched in images of awe, terror, hallucination [and] mystery.”[16]

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) was a close friend and artistic heir to Géricault and, in many ways, a later leader of the French Romantic school. Delacroix’s impressive use of brush-strokes and the optical effects of color and movement prepared the way for the later Impressionist School of Art. Like Géricault, Delacroix had studied the great Renaissance artists and had also painted scenes of death and dissolution (for example, The Barque of Dante in 1822 and The Massacre at Chios in 1824) and emotional scenes of stirring nationalism, but he did so with more emotional control than Géricault. His most renowned painting, Liberty Leading the People (1830), portrayed a bare-breasted female symbol of Republican Liberty marching under the banner of the tricolor flag, representing liberty, equality, and fraternity. Over 9,000 works have been attributed to Delacroix, including 850 paintings, 1,500 pastels, and more than 6,600 drawings.[17]

No study of Romantic art would be complete without considering William Blake, the so-called prophet of his age, who stands defiantly outside all formal schools of training. His work tended to the mystic and the spiritual, exploring the problem of evil in a God-created world. An English Jacobin, Blake opposed royal and sectarian subjugation and authority and yearned for an English revolution like that in France or America (see his “Albion Rose”). He was, to borrow Brian Luhacher’s phrase, a countercultural Romantic poet, painter, and engraver.[18] He decorated his books of poetry—including Songs of Innocence (“The Lamb,” 1789) and Songs of Experience (“The Tiger,” 1794)—in the medieval fashion of illuminated manuscripts complete with relief etchings and woodcuts. Blake was a mystic, an enigma, and a believer in the Swedenborgian tradition of prophecies, visions and dreams, and an imminent apocalypse. His inspiration came not from nature’s landscapes but, as he believed, the voice of God speaking to him from within. His art, what one scholar called “the super-reality of the visionary,” is brilliantly colored and unique in symbolism, bordering on the sublime and the surreal.[19]

With England being spared the traumas and terrors of the French Revolution and the scourge of conquering armies, the Romantic impulse there took a more graceful turn. More a nostalgic response to the intrusion of the Industrial Revolution on English agricultural life and society, the English art of this period favored the picturesque landscape paintings of William Gilpin (1724–1804), Humphry Repton (1752–1818), and the watercolorist Thomas Girtin (1775–1802), with his famous The White House at Chelsea. This generation of painters took Romantic landscape painting to new heights. In England, an early precursor of Romantic artists was the Swiss-born Henry Fuseli (1741–1825), who was as prolific with the pen of an art critic as he was with the brush. Many of his early paintings were inspired by the works of John Milton. Fuseli favored the supernatural and grotesque humor, as evidenced in The Nightmare (1781) and Horseman Attacked by a Giant Snake (1800).

Perhaps the three most famous English artists of the rustic landscape school were John Constable (1776–1837), John Martin (1789–1854), and that renowned painter of light, J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851). These artists sought to portray insensate nature in a way that was emotionally compelling to the viewer. They believed that “the contemplation of nature can provide the deepest moments of self-discovery,” which has led some scholars to refer to this expression as “transcendent landscape art.”[20] Constable is well remembered for his pure and unaffected paintings of pastoral England. His The Hay Wain and The Clouds, for example, are pure and unaffected efforts to feel the simple, peaceful, and enduring beauty of nature in a way that is spiritually uplifting and wholly unforgettable.

As much a traveler as Constable was a stay-at-home idyllic artist, J. M. W. Turner painted oil landscapes of grandiose historical themes (Battle of Trafalgar, 1822) but more especially nature’s many moods and sublime or terrifying indomitability and mastery over man, as best seen in his Shipwreck (1805) and Snow Storm: Hannibal and His Army Crossing the Alps (1812). Disaster pictures, especially shipwrecks, were favorite topics of many Romantic artists. And in the best Romantic tradition, Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed: The Great Western Railway (1844) blended reality with imagination as it captures an intruding, oncoming train of the Industrial Revolution into the once idyllic, picturesque English landscape with impressionistic-like mood and vitality. Turner is properly called the painter of light because of his transcendent visions of color and its effects. Turner captures the brilliance of the sun and the ghostly effect of moonlight in his paintings of Venice and Rome. Through this skill, Turner speaks of a divine spirituality and a wonderful optimism of a benevolent, shining nature that, when all is said and done, promises more light and truth. As bright and optimistic as Goya tended to the dark and pessimistic, Turner captured the brightness of day like no other contemporary artist.

Rain, Steam and Speed: The Great Western Railway (1844), by J. M. W. Turner.

Rain, Steam and Speed: The Great Western Railway (1844), by J. M. W. Turner.

The Romantic landscape impulse likewise found expression in Germany, where a longing for German unification and budding nationalism found full sway in the Blake-like mystic landscape art of Phillip Otto Runge (1777–1810) and was more darkly manifested in the works of Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840). Both artists strenuously opposed French occupation and showed a more Christian-centered, melancholy theme. Well known are Friedrich’s Procession at Dawn (1805), The Cross in the Mountains (1808), and more particularly his Abbey in the Oakwood (1809–10), with its Gothic overtones and stark landscapes. He seemed to show that the era when God revealed himself directly to man may have passed, that nature, and not sectarian religion, was the sublime way to gaining true spirituality and oneness with God and Christ. Many of Friedrich’s paintings of lonely, barren landscapes and of Arctic shipwrecks reflect his “fading hope of a united German nation.” [21]

In America, the mood was much brighter and far more optimistic than in Europe. The recent American Revolution, the declaration of independence from Great Britain, and the beckoning of a magnificent western wilderness all filled the new republic (see chapter 11) with a hope and vibrancy that was in stark contrast to the gloom and despondency of many post-Napoleonic European Romantic artists. Inspired by the works of John Constable, J. M. W. Turner, and other English Romantic artists, Thomas Cole (1801–48, leading artist of the Hudson River School), Asher B. Durand (1796–1886), and Frederic E. Church (1826–1900) boldly presented vast panoramic vistas of America’s promised land. A notable example of this is Cole’s View of the Round-Top in the Catskill Mountains (1827). This school of art presented intoxicating spectacles of national power and of America’s destiny in successfully taming a new and seemingly endless wilderness of opportunity. Depicting scenes along the Hudson River in the 1820s and later of New England, Niagara Falls, and more westward places, these vivid paintings depicted America as a new and bountiful Garden of Eden, an idealistic manifestation of sublime peace and wonder where both humans and nature could coexist in majestic beauty and everlasting harmony.

Another notable innovation associated with Romanticism was the emergence of political caricature in the graphic arts. In Great Britain, James Gillray (1756–1815) pioneered exaggerated portraiture, particularly in his satirical representations of King George III. In France the political cartoonist of the day was Honoré Daumier (1808–79). Etching was also becoming an acceptable creative medium.

In portraiture painting, one sees the influence of early Romanticism. Probably the most famous portrait painter of the eighteenth century, certainly in England, was Thomas Gainsborough (1727–88). Remarkably proficient technically, he had developed a style of portrait in which he integrated the sitter into the background landscape, as in his famous Blue Boy (1770). Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830) followed suit with his equally famous Pinkie, painted in much the same fashion in 1794.

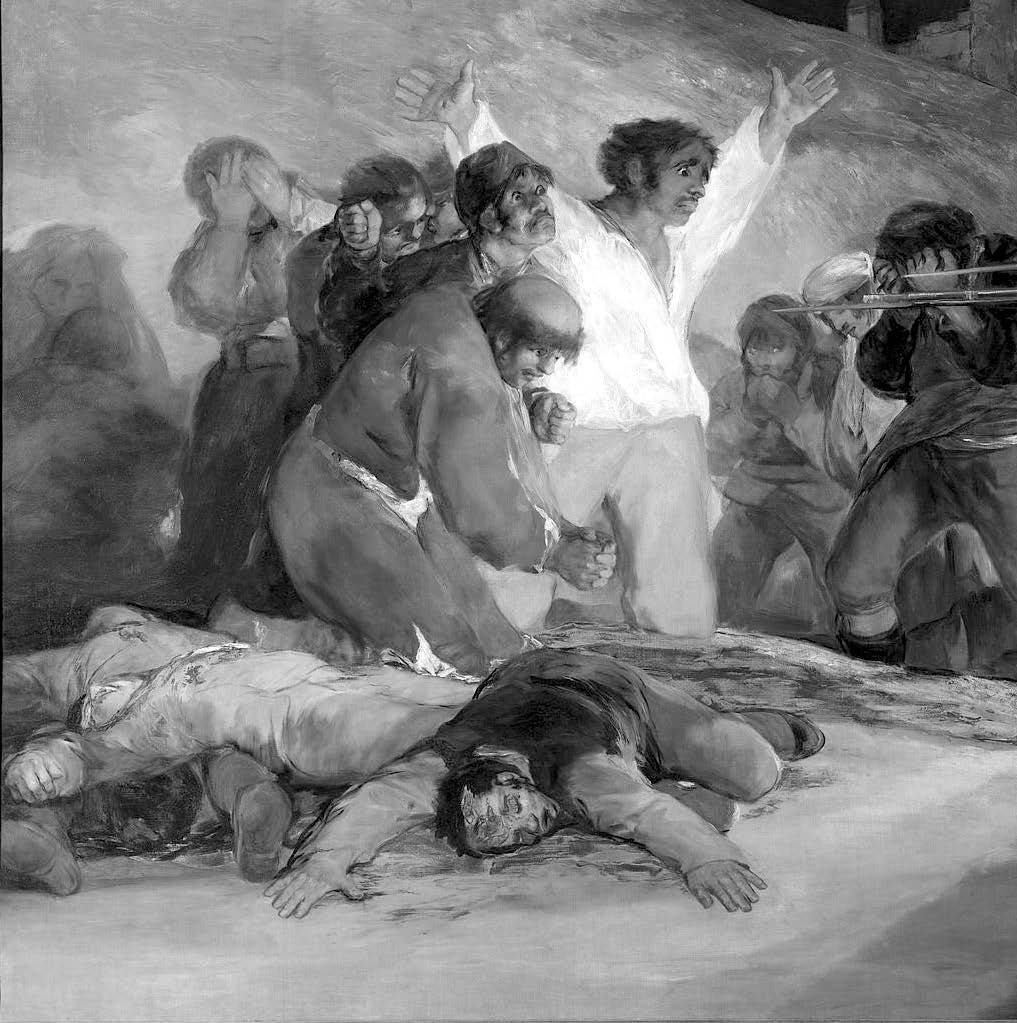

The Third of May, 1808, by Francisco de Goya. Detail.

The Third of May, 1808, by Francisco de Goya. Detail.

On the continent, the most famous portrait painter was the inimitable and highly imaginative Spanish painter, Francisco de Goya (1746–1828)—at least he started out as such. As with David in France, Goya was royalty’s “first painter” (in this case for Spain’s King Charles V) and a magnificent portrait painter of the aristocracy. Goya’s portraits captured much more than likeness: they expressed the psychology and the deepest sentiments and slightest nuances of emotion and heightened feelings in his subjects—especially fear. Privately he was inclined to paint the troubled waters of the grotesque, the nightmarish, and the mysterious. An eyewitness to the horrors of the French occupation of Spain from 1808 to 1814, he turned his attention from mere portraits to capturing on canvas the panic, chaos, and awful brutalities of the Iberian Peninsula War. Unforgettable are his Third of May, 1808 (1814), in which he painted Spanish insurgents being executed by French occupational forces, and his scores of drawings entitled The Disasters of War (1810–20). Like Beethoven, Goya became deaf near the end of his life. Nevertheless, he emotionalized his art by dramatizing his way through to the awful truths of inhumanity to and the ignobleness of war.

Although the Romantic impulse was harder to see in sculptures, the most prominent sculptor of the age was likely Pierre-Jean David D’Angers (1788–1856), who made very enthusiastic studies of the most prominent figures of his time, as evidenced by his Wounded Philopoemen. Along with such other contemporary French practitioners as August Préault (1809–79), Johan de Seigneur (1808–66), Antoine Louise Barye (1796–1875), and François Rude (1784–1855), D’Angers moved somewhat away from the smooth surfaces of classical sculpture to rougher, more individualistic, more emotional effects.

And in architecture, the Romantic once again found its finest expression in recapturing the past of the Medieval Age, most particularly in Gothic representations on both sides of the Atlantic. This was most evident in the building of churches and universities. James Wyatt’s Fonthill Abbey (1807), Alexander Davis’s Blithewood Estate in Fishkill, New York (1834), and Richard Upjohn’s Trinity Church in New York City all come to mind as examples of this reclaimed, artificial Gothic. And in the field of landscape gardening, there were grandiose redevelopments in major capital cities. Napoléon set the new standards for this expression in Paris, and the Prince Regent (later George IV) commissioned John Nash (1752–1835) to do the same in London.

Géricault in Italy

The factors that led up to Géricault’s decision to go to Italy and the influence his study of Roman and Florentine art had upon him are central to understanding the troubled genius of the man. As with David, Delacroix, and other contemporary French painters, most serious artists of the time believed that a season in Italy studying the classics of antiquarian art was a necessary rite of passage, an essential prerequisite for professional advancement and state appointments. Still somewhat of an outsider to the academic art establishment, Géricault may never have won the Prix de Rome, but he was financially secure enough to spend a year in Italy.

The Wounded Cuirassier, by Théodore Géricault, study (ca. 1814).

The Wounded Cuirassier, by Théodore Géricault, study (ca. 1814).

Géricault sought to escape the stagnant depression that gripped Paris and all of France in the wake of Napoléon’s crushing defeat at Waterloo and his subsequent exile to the island of St. Helena. To one as fervently patriotic and republican as Géricault was (he briefly served in the army), la gloire de la France was a painful memory. Two of his earlier paintings, Chasseur de la Garde (The Charging Light Cavalryman) of 1812 and Le Cuirassier Blessé Quittant le Feu (The Wounded Heavy Cavalryman), which he painted only two years later, are vivid studies in emotional contrasts, capturing the rise and fall of France’s once-feared cavalry. The former is a glorification of French triumphant military might and ascendancy, with a cavalry officer on the back of a charging steed. It was well received. The latter, a much more forceful and original work in more subdued shades and leaden tones, shows a wounded, dismounted, and defeated cavalryman solemnly retreating from the scene of battle, a sober testament to Napoléon’s devastating defeat. Considered a transitionalist artist, Géricault sought to capture the drama, expressive force, and feelings of war among the anonymous men who fought in it, both victors and victims. Inclined as he was to the violent, macabre, and pessimistic, Géricault sensed a prolonged stay in Italy would do good for his mental and physical health.

There was also another reason for his extended visit. By 1816, now aged twenty-five, Géricault had fallen passionately in love with his aunt, Alexandrine-Modeste Caruel, wife of his uncle Jean-Baptiste Caruel, head of the family business. At the time, she was already mother to two sons who were six and seven years old. Unlike her husband, she was drawn to art. Charles Clément, Géricault’s biographer, called the relationship with Alexandrine a “reciprocated, irregular stormy love that he could not acknowledge but to which he saw all the vehemence of his character.”[22] While his kind and trusting uncle continued to support and sustain him, Géricault secretly carried on with his liaison. Afflicted by contrasting feelings of love and guilt, joy and remorse, and with an agonizing fear of being discovered, Géricault tore himself away from the only woman he ever loved, crossing over the Alps.[23]

In Italy, first in Florence and then in Naples and Rome, Géricault entered into what one might call his second period of creativity. While studying the paintings of Michelangelo and Raphael, Géricault found his own inner artistic expression and creativity, not a mere mimicking of classical art but, as Wheelock Whitney describes it, a capturing of the “antique manner” of great classical art without its rigid classical forms.[24]

Learning to go deeper than outward appearance by capturing underlying human emotion, Géricault blended “the solemn, timeless qualities of the art of antiquity, and the High Renaissance with the excitement and energy of ideas from everyday life, . . . a synthesis of the Rome of the Caesars and the Rome of the Popes.”[25] Drawn to the common rather than the heroic, he gained his greatest inspiration from everyday occurrences such as parades, street rallies, and carnivals. He shared the Romantic fascination with the horse as an image of superhuman energy. In all of Géricault’s equestrian paintings, he captured not only differences in breeds but also differences in personality, with something almost human in their expressions.[26]

He was also fascinated by the violent, the gruesome, and the macabre, as evidenced by his many Italian notebook sketches of men injured in the streets, the butchering of cattle, and public executions and decapitations—a “brutal realism undiluted by literary, mythological, historical or political associations.”[27] And he owned that unique ability of capturing the spontaneous and the extreme or climactic moment of virtually any event before him without the clutter of detail or distraction.

His self-imposed absence from Alexandrine may go far in explaining the turbulent erotica and rampant sexuality evident in his later Italian paintings of 1817. Géricault was a passionate, troubled young man who often used brush and canvas to work out the warring emotions that bedeviled him. From out of this cauldron of heightened emotions, he produced such exquisite art as Young Woman Holding a Child (1816–17) and Leda and the Swan (1816–17). His most important Italian project was Start of the Barberi Race (1817), inspired by the carnivals and horse races of Naples. In many of the eighty-five preliminary drawings and paintings he drew before completing his central piece, there are mass groupings of many human figures in pyramidal form, showing a collective sense of impending danger and a severe juxtaposition of darkness and light—all painted in the grand scale that presaged his Raft of the Medusa. Men and horses were shown in classic Apollo form as he combined neoclassical and Romantic expressions.[28]

The Raft of the Medusa

Upon his return to Paris in the fall of 1817, a hapless Géricault renewed his secret love affair with Alexandrine, no matter the shame and regret it would inevitably cause. She soon became pregnant, and when it was discerned that his uncle could not possibly have been the father, family suspicion turned frowningly on Géricault, who, painfully and reluctantly, admitted to it all. To prevent further reproach and dishonor, Alexandrine sought privacy in a country estate, where in November 1818 she gave birth to their son, Georges-Hippolyte (d. 1882), a secret kept hidden from sleuths and scholars for over 150 years.[29]

Such was the troubled and tormented life of Théodore Géricault when he stumbled across the story of the sinking of the Medusa. Immediately captivated by its enormous human drama of suffering and death, Géricault sequestered himself, monk-like, in his private studio, where he embarked upon the painting of his life in February 1818. He spent the next eight months at work, occasionally visiting morgues and hospitals to study body parts of the sick and dying but mostly secluding himself at home, where he painted series of episodes relating to the mayhem and mutiny of the disaster. Over time, he painstakingly sketched out on a colossal canvas, some twenty feet high, one larger-than-life figure after another. Visitors were few and infrequent, although Delacroix posed for one of the dying figures. Géricault worked at a feverish pace, sleeping and eating only intermittently, seldom stopping for visitors or relaxation. Gradually, his enormous painting began to emerge.[30]

A painting of such power that was so blatantly critical of the ruling governing authorities would inevitably stir controversy, if not intervention. And with the secret of his love affair now out in the open and his aunt forced far away, Géricault drowned his sorrow and his guilt in secrecy and in a torrent of activity. So he toiled on in tormented seclusion. His love for Alexandrine was one he took to his early grave, for in truth he almost worked himself to death painting his masterpiece.

Le Radeau de la Méduse (The Raft of the Medusa) is a timeless drama. Its series of diagonals moving up from the foreground toward the sky captures the climactic moment of both hope and despair, that precise time when several in that collection of writhing sailors and survivors were at the point of death. The positioning of Géricault’s human figures into four distinct groupings—the dead and dying at the stern, the more alert and watchful on the other side of the mast, the struggling men who drag themselves to the far edge of the raft, and the three men who mount some barrels at the raft’s forward end to signal the distant ship—is “so precisely thought out, so clearly described, that the conflicting gestures are held in a coherent pattern that has the powerful simplicity of truly monumental art.”[31]

The Raft of the Medusa (1818–1819), by Theodore Gericault.

The Raft of the Medusa (1818–1819), by Theodore Gericault.

The Raft of the Medusa defies simple explanation but is considered an important bridge between the neoclassical and Romantic styles. Géricault’s human figures, nearly twice life-size, though pale and apparently emaciated, are portrayed in a powerful, classical, superhuman style, like Olympic deities. The lines in the painting direct the eye upward, pyramid-wise, to a pinnacle where a black man, signaling the hope not only of their rescue but also of emancipation for an entire race, reaches above the rest, savior-like, seeking for the redemption of his ship and of all humankind. The contrasts in mood are remarkable between the disconsolate father—grasping the partly cannibalized body of his dead son, whose left arm is stretched out in invitation for all viewers to understand—and the jubilation of another man, turning in excitement to tell the news of the distant ship with his left arm pointing upward in contrast to the dead son below. It is a dense, crowded, and graphic scene of contrasts: hope and despair, young and old, life and death, and past and future. It is almost biblical—certainly Romantic—in its vivid portrayal of abject suffering, utter despair, and unexpected joy—a kaleidoscope of human emotions all tossed together in a storm on a single raft in a roiling sea.

When unveiled to the public at the Salon of 1819, it stirred immediate controversy. Reaction to it was muted and mixed. Some critics adored; others deplored it or were at least disturbed. King Louis XVIII gazed at it for several long moments, not sure at first what to make of it. The royal word, however, is said to have been: “Mr. Gericault, you have just made a shipwreck that is not one for you,” although the king did award him with a medal.[32] Other government officials, who by then had tried and court-martialed the ship’s captain, were less condemning than Géricault thought they might be. But no royal commission was forthcoming, and Géricault, discouraged over a less-than-enthusiastic response, left for England in the fall where the painting, on display at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly in June 1820, generated a much more favorable public response—a case of a prophet without honor in his own country.[33] Géricault’s share of the receipts amounted to almost twenty thousand francs, a most considerable sum. Although Géricault was arguably “the purest incarnation of Romantic art in France,”[34] it took the stilling of a thousand prejudices before his painting could ever be accepted as the masterpiece it has become.

The Raft of the Medusa has since gained universal renown as a classic metaphor for humankind. Contemporary journalists saw in it the obvious condemnation of the naval ministry, which surely it was, while others viewed it as Géricault’s chastisement of the Bourbon royalty. Jules Michelet later said of it, “C’est la France elle-même; c’est notre societé toute entiére qu’il embarqua sur ce radeau.” (It is France itself and all of our society, that embarked upon that raft.)[35] Still others have seen in it a religious motif symbolizing the fall of man, his apostasy from truth, and his desperate need for rescue, restoration, and redemption. For our purposes, however, Géricault’s painting may well have captured the spirit of the age of 1820. It too was a time of searching and of revolution, of prophets and of revelation, of coming out of the despair born out of the ancient regimes of the past, and of being rescued by the emerging light of a new age. A long, dark night of death and despondency was finally coming to its close.

His Final Years

Géricault lived for only four years after returning home from England in this the third and final creative period of his short life. Until recently, most scholars believed that this was his least productive time. Although he gave serious thought to painting another mighty mural on yet another political and humanitarian theme such as the injustices of the slave trade or the cruelties of the Spanish Inquisition, nothing ever came from such plans, likely on account of the severe depression that overtook him. Some believe he may have even considered suicide, a realistic possibility, considering the fact that there was a history of mental illness in his family. His maternal grandfather had committed suicide, and an uncle on his mother’s side had died insane in 1805.[36]

Surely had every reason to be depressed. He was almost daily haunted by the guilty memory of the one who died in his place. When Géricault was drafted into Napoléon’s army some years before, his father had paid for a substitute to serve in his place, a young man by the name of Claude Petit. Tragically, Petit had died from wounds he suffered in 1812 at the Russian front, along with three hundred thousand other men. Furthermore, the man who sat for Géricault’s painting of the Chasseur de la Garde, Lt. Alexandre Dieudonné, had also perished while fighting in Russia that same year. The fact that both men died in a losing cause hurt Géricault even more. Surely Napoléon’s inglorious defeat and the return of the French monarchy was a bitter pill to swallow.

To add to his troubled spirit was the disappointment of never having won the much-coveted Prix de Rome and the fame it surely would have brought him. Perhaps the strain of painting the Medusa and the less-than-positive response it initially received also discouraged him from going further. Nor did he ever recover emotionally from the loss of his star-crossed lover, the erosion of family respect, and the wall of separation the family erected between him and his infant son. Such grief and guilt led to moral lassitude, which at times laid him low with syphilis, likely being the cause of his many illnesses late in life.[37] Compounding his misery was a foolish investment in a failed factory enterprise that led to personal bankruptcy in 1823.

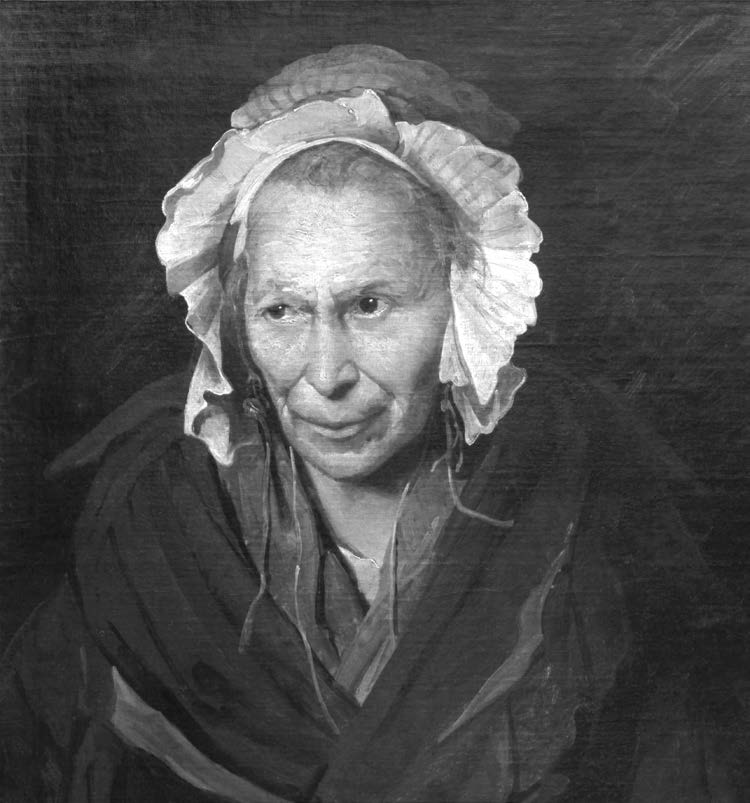

The Mad Woman, by Théodore Géricault (ca. 1819/

The Mad Woman, by Théodore Géricault (ca. 1819/

During these final years, Géricault was driven to painting the poor, the alcoholic, the sick, and the insane in a series of portrait sketches unique for their subject matter. It was almost as if he were painting his own despair. In his Portrait of a Kleptomaniac (1822), Monomaniac of Child Abduction (1823), Monomaniac of Military Command (1823), Monomaniac of Gambling (1823), and The Madwoman or Monomaniac of Theft (1824), Géricault displayed a profound psychological penetration uncommon in other painters, a morbid empathy for the outcast and the ignored. This series of maniacal paintings, originally ten in all, were rejected by the Louvre, set aside, and virtually lost for some forty years before they were rediscovered piecemeal, sold to various buyers, and all but forgotten. In time, five of the lot were eventually tracked down and once more exhibited together in Paris in 1924, a century after their creation.

The plight of the mentally challenged had for centuries been an uncelebrated cause. Conditions in hospitals, asylums, and prisons, even in the late eighteenth century, were still horrible. Locked up, chained, crammed together in the most filthy and squalid conditions imaginable, treated as animals, and displayed as curiosities and wild beasts, those with mental illness were viewed as a derangement to be feared, forgotten, and forsaken.

It took the pioneering efforts of Dr. Philippe Pinel (1745–1826) to take up the cause of the mentally ill in a serious, scientific manner. Working in concert with others of similar interests, most especially Jean-Etienne Dominique Esquirol (1772–1840), the most eminent specialist of the day in insanity, Pinel set about ordering and classifying the various levels of madness, such as distinguishing melancholics from maniacs and separating the curable from the incurable. Interviewing hundreds of the insane, he founded a new form of “moral” psychotherapy: “to engage the patient in dialogue during periods of lucidity, and establish a relationship of trust, in what would now be called a therapeutic alliance.”[38] As a doctor who would listen to rather than mock his patients, Pinel unchained many of his patients and discarded the long-popular equating of mental illness with demon possession. Taking careful and voluminous notes and compiling statistical summaries of his work, he set about publishing his results and making highly informed and enlightened recommendations on the treatment of the mentally ill. Many today regard him as the father of modern psychiatry.[39]

Géricault likely knew both Pinel and Esquirol. He may have even been a patient. Whether that is true or not, Géricault also went about visiting various asylums and hospitals, interviewing many of the insane who resided there. As a “painter-analyst,” to borrow Robert Snell’s phrase, Géricault forced his viewers to reflect upon such people and their conditions and to register a sense of their unique personhood. His surviving portraits of anonymous inmates are “powerful, startling works, . . . far from voyeuristic or prurient. They show ordinary, recognizably individual idiosyncratic people” and offer viewers even today an indispensable aid to understanding the subject matter of mental illness. They therefore provide “critical reflection for our own uneasy times.”[40]

Art historians have since come to see Géricault’s efforts as unique, a serious probing of a long taboo subject, a penetrating effort to try to understand the mentally ill and challenged. His painting of such subjects was “not through a diabolical lack of feeling but for the value of such scenes as unique documentation for their monstrous strangeness, for their anomalousness.”[41] In taking interest in such lost souls onboard rafts or bound in asylums and in capturing on canvas their likeness and pain, Géricault was a morning light with a newfound vision of what could and should be done for them. In that regard, he was a pioneer painter-analyst, decades ahead of his time.

France’s tormented artist died in relative obscurity on 18 January 1824 from injuries suffered, ironically, after falling from a horse. Quietly and without fanfare, the Louvre set about purchasing his mighty Medusa only afterward. A monument was finally erected in his memory at the Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris’s largest cemetery, seventeen years later in 1841, just after Napoléon’s remains were returned to France.

For over a century, Géricault’s reputation has languished behind that of several other leading Romantic painters of his time, particularly Delacroix, who was always more emotionally controlled than Géricault.[42] Gradually, however, as several more of his sketches and paintings have come to light and as many more details of his life have been uncovered, Géricault has been reclaimed and his reputation reestablished. Considered a tragic figure still, Géricault is now esteemed as a key transitional painter of his age. His masterpiece painting, with its powerful penetration and presentation of a struggling humanity but with hope and light on the horizon, will surely stand as one of the finest artistic expressions of the Romantic era.

Notes

[1] Roberts, Comprehensive History of the Church, 6:252.

[2] The Times (London), 17 September 1816, 2.

[3] The Times, 17 September 1816, 2.

[4] The Times, 17 September 1816, 2.

[5] Vaughan, Romantic Art, 232.

[6] Eitner, Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa, 12.

[7] Brion, Art of the Romantic Era, 13.

[8] Honour, Romanticism, 16.

[9] From the foreword of David’s The Painting of the Sabines, as exhibited to the Republic at the National Palace of the Sciences and the Arts, Hall of the Former Academy of Art by The Citizen David, member of the National Institute, Paris, Year VIII, as cited in Holt, From the Classicists to the Impressionists, 4.

[10] Vaughan, Romantic Art, 61.

[11] Rosenblum, 19th-Century Art, 24–30.

[12] Crow, “Classicism and Romanticism: Patriotism and Virtue: David to the Young Ingres,” in Eisenman, Nineteenth Century Art, 18–20.

[13] For more on David, see Robert, Jacques-Louis David.

[14] Vaughan, Romantic Art, 222.

[15] Honour, Romanticism, 36–38.

[16] Rosenblum, 19th-Century Art, 62.

[17] For a good, recent study of Delacroix and the French Romantic School of Art, see Johnson, David to Delacroix.

[18] Brian Lukacher, “Blake and His Contemporaries,” in Eisenman, Nineteenth Century Art, 102.

[19] Vaughan, Romantics, 82.

[20] Vaughan, Romantic Art, 134.

[21] Lukacher, “Landscape Art and Romantic Nationalism in Germany and America,” in Eisenman, Nineteenth Century Art, 150.

[22] Clément, Géricault, 77.

[23] Eitner, Géricault, 75.

[24] Whitney, Géricault in Italy, 3.

[25] Whitney, Géricaultin Italy, 43, 49.

[26] Berger, Gericault, 11.

[27] Whitney, Géricault in Italy, 55–57.

[28] For instance, see Start of the Barberi Race (1817).

[29] If Charles Clément, Géricault’s nineteenth-century biographer, knew of this episode, he conveniently kept it quiet to guard the reputation of those involved. Only recently and quite by accident did researchers stumble across evidence of the episode in papers found in a Normandy attic.

[30] Zerner, Géricault, 28–33.

[31] Vaughan, Romantic Art, 240. For a discussion of the four groupings, see Eitner, Géricault’s Raft, 29.

[32] Eitner, Géricault’s Raft, 6.

[33] Appearing in the Literary Gazette was this comment: “Taken all together, his work is, as we before observed, one of the finest specimens of the French school ever brought to this country.” The London Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, etc., 1 July 1820, 427.

[34] Rosen and Zeiner, Romanticism and Realism, 39.

[35] Honour, Romanticism, 41.

[36] Snell, Portraits of the Insane, 39–41.

[37] Michel, Chenique, and Laveissiere, Géricault, 34.

[38] Snell, Portraits of the Insane, 70–78.

[39] Pinel, Treatise on Insanity.

[40] Snell, Portraits of the Insane, xv.

[41] Brion, Art of the Romantic Era, 154.

[42] Thomas Crow, “Classicism in Crisis,” in Eisenman, Nineteenth Century Art, 77–81.