Of Prophets, Preachers, and Poets

William Wilberforce, Hannah More, And The Abolition of Slavery

Richard E. Bennett, “Of Prophets, Preachers, and Poets: William Wilberforce,” in 1820: Dawning of the Restoration (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 181‒206.

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound

That saved a wretch like me.

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind, but now, I see.

’Twas grace that taught my heart to fear.

And grace, my fears relieved.

How precious did that grace appear

The hour I first believed.

—John Newton (1725–1807)

Hannah More, by Henry William Pickersgill.

Hannah More, by Henry William Pickersgill.

The purpose of this chapter is to investigate yet another kind of revolution contemporary to, and descriptive of, the age of 1820—a revolution in religious belief, practices, and social thought that set a conservative tone in the social mannerisms and religious behavior of the coming Victorian era, the effects of which are still being felt. Our study has given ample space thus far to studying the French, the Industrial, the Romantic, and the Agricultural Revolutions with all their many characteristics and consequences. What now begs our attention is the Methodist and evangelical revival that spared England and its expanding overseas empire from what many Britons saw as the godless secularism then engulfing France. This religious revolution eventually culminated in that long, arduous, and eventually successful effort of two “earlier lights” in the morning of the Restoration, to cite B. H. Roberts once again, that eventually ended the scourge of slavery throughout the British Empire.[1]

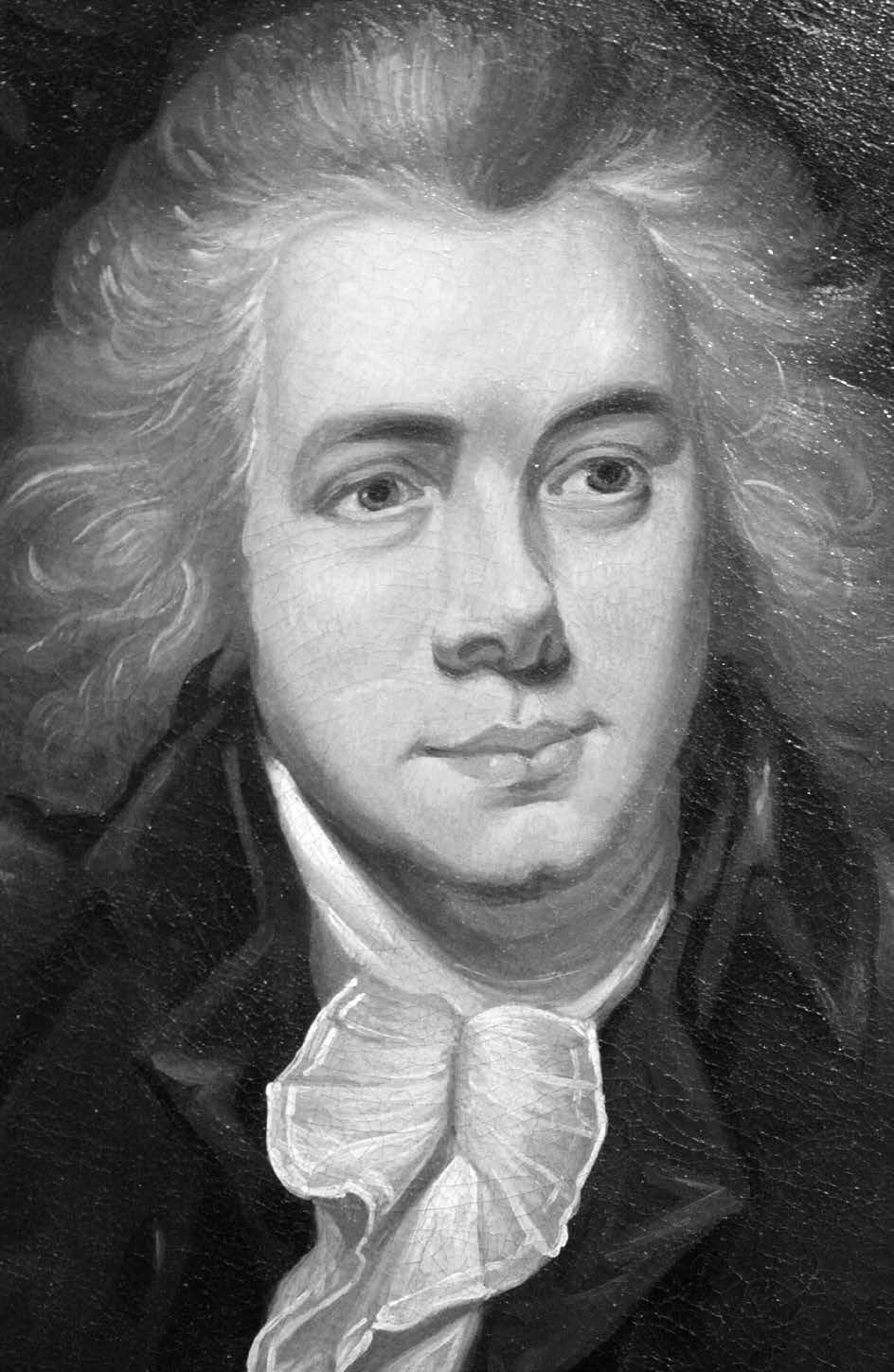

William Wilberforce c. 1790 (after John Rising), by Stephen C. Dickson.

William Wilberforce c. 1790 (after John Rising), by Stephen C. Dickson.

Of all the many personalities on this religious stage, we have time to study but two, without either of whom this transformation would have been impossible: William Wilberforce (1759–1833) and Hannah More (1745–1833). If Napoléon was the spirit of the age, Wilberforce became its moral conscience first by spearheading the long but ultimately successful campaign to rid England and its empire of slavery and second by establishing a new and renewed sense of “vital Christianity,” especially among the higher ranks of society. And if Wilberforce was the prophetic voice of this great humanitarian and religious revival, then Hannah More, with her persuasive pen, was its poet, transcribing Christian beliefs, customs, and convictions into a compelling popular literature that spoke to the millions of poor and barely educated men and women. Wilberforce’s and More’s deeply held convictions and combined efforts revitalized British Christianity and the efforts to eliminate slavery in the British Empire. This momentous accomplishment later inspired Abraham Lincoln to push for the same in an America slow to divest itself of this moral curse. Without the persistent influence of Wilberforce, slavery may have endured decades longer than it did, and without his Christianizing influence, Great Britain may well have gone the secular route of France.

“The Church Militant”: John Wesley and the Earlier Methodist Revivals

To understand why Wilberforce became such a transforming figure, we must once again travel further back in time to appreciate the foundations that later bore such positive fruit. Over a century ago, Elie Halévy (1870–1937), the noted French scholar of British religious history, argued that the revival of evangelical religion in the late eighteenth century spared England of a French-style Jacobin Revolution.[2] As discussed in the previous chapter, surely all the makings of a class struggle were evident: the economic disruption and unemployment brought on by the Industrial Revolution; family displacements; the despair and riots of the working classes, or proletariat; rising class envies and agitations; a weak, increasingly distant, and unsympathetic established church; and a conservative government intent on repressing violence and resisting the growing democratic demands of the commoner. By 1800, Great Britain was at a crossroads but, instead of turning against the established order, reasserted itself religiously in a way unlike any other European nation.

What happened in England in the era of 1820 with Wilberforce and More had its roots some eighty years before in 1739 with John Wesley (1703–91), Charles Wesley (1707–88), George Whitefield (1714–70), and the great Methodist revivals. This highly spirited religious reformation was a reaffirmation and a rekindling of England’s long-standing, deeply felt Christian convictions. Another famous French historian, Hippolyte Taine, once described the English as possessing a “naturally serious, meditative, and sad” temperament that can be traced back as far as the Protestant Reformation.[3] Generally uneasy, if not distrustful of the clergy and of its priestly ordinances, the English, despite the Glorious Revolution of 1689 and the reestablishment of a Protestant monarchy, had never warmed to its own established Church of England. It was more “a country of voluntary obedience” than of imposed religious prescriptions and creedal directives.[4]

Capitalizing on economic discontent, the Methodist movement gained rapid popularity for at least four reasons: (1) the inability of the Church of England to satisfy the deep religious cravings of its people; (2) the rise of vice and popular degradation and the fear over what English society was becoming; (3) the outstanding courage, spiritual command, doctrinal understandings, powerful preaching, and organizational skills of John and Charles Wesley and George Whitefield; and (4) the give-and-take doctrine of man’s condemnation for sin on the one hand and Christ’s willing forgiveness on the other.

The seeds of this religious outburst were sown in large part by a static, state-supported church that was never too popular and in a society “no longer constrained to accept its leadership.”[5] Financially supported by the state rather than by its parishioners, the Anglican clergy was perceived as overpaid, out of touch, and indifferent to the needs of its membership, a profession of inheritance and prestige rather than a call to service. Many parishes suffered from absentee clergy, due in part to the wrenching demographic changes brought on by the Industrial Revolution. While England’s population grew from 5.5 million in 1740 to 13.1 million in 1831, the number of Anglican churches remained static, and the Church of England declined from monopoly to minority status.[6] Tightly bound by prayer book formality, the church was perceived by many as class-bound, aristocratic, apathetic, nepotistic, and out of touch with the everyday needs and problems facing most English families living in poverty from day to day. Consequently, just after its formation, it lost favor with the modern urban working class.

The Methodist movement came also as a response to a perceived decline in societal morals and conduct. “The superstitions of Popery were disregarded and despised, but the licentiousness of infidelity covered the land,” wrote one nineteenth-century scholar of Methodism. “The rich were wholly regardless of the claims of religion, and even considered vital godliness as the height of fanaticism. The poor were sunk into the lowest depth of vice and degradation,” a state of “spiritual putrefaction.” He added, “Wickedness flourished, piety languished, and God was forgotten.”[7]

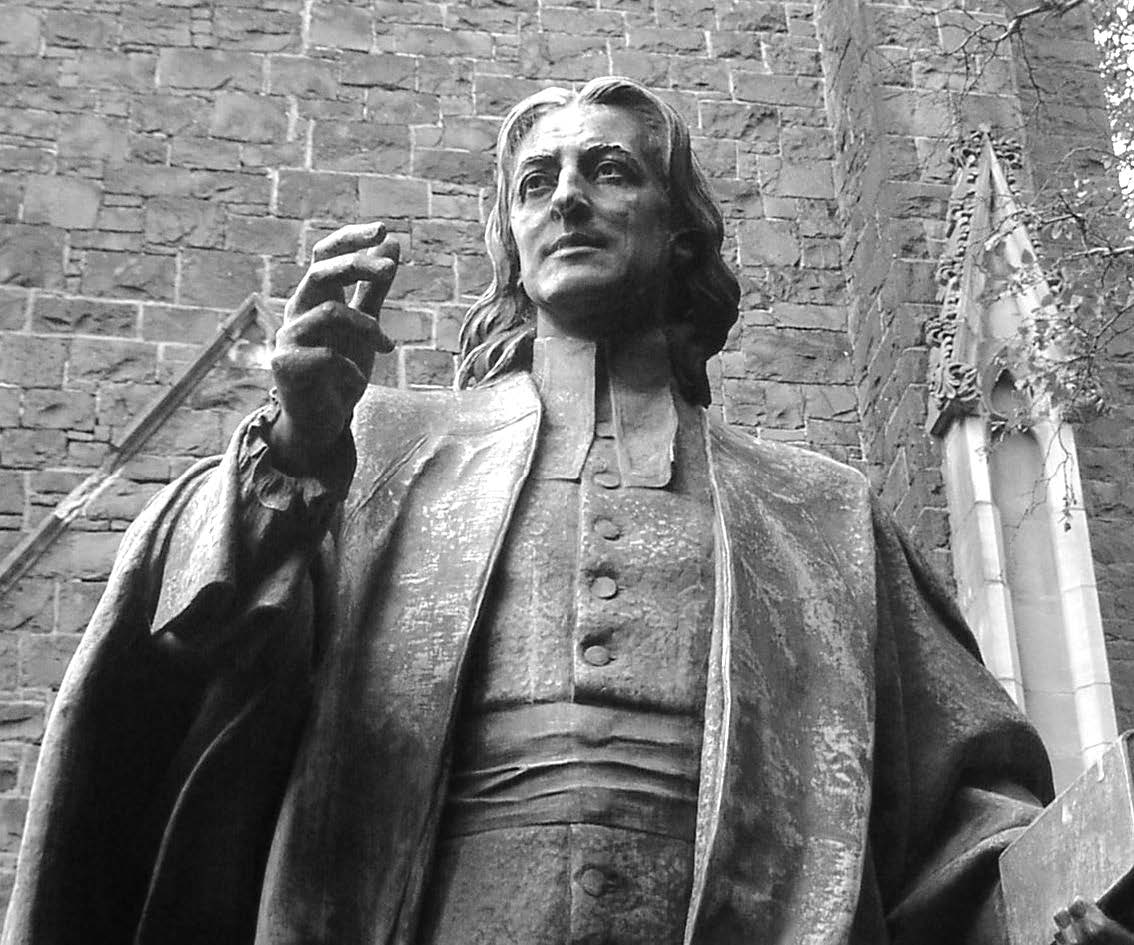

Statue of John Wesley in Melbourne, by Paul Raphael Montford.

Statue of John Wesley in Melbourne, by Paul Raphael Montford.

The clerical spark plug to the Methodist movement was John Wesley. Born in 1703, educated at Christ Church, Oxford, and ordained an Anglican clergyman in 1725, Wesley underwent a crisis of faith after returning from a mission tour to the colony of Georgia in America. Having witnessed there the personal assurance of salvation among the German Moravian missionaries, he prayed for and received a life-changing spiritual certainty and conversion to Christ. “I felt my heart strangely warmed,” he wrote. “I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone, for salvation; and an assurance was given me that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death.”[8]

Convinced that his own Church of England was lacking the spiritual enthusiasm or power to change hearts and bring souls to Christ, he set out on a new path. In company with his more musically talented and poetic younger brother, Charles, whose hymns portrayed the spiritual majesty of the movement, and encouraged by his former pupil George Whitefield, John Wesley took the unprecedented and courageous step in 1739 of preaching beyond parish boundaries, not in the churches and cathedrals, which were closed to him, but in the barns and byways of England. “I look upon all the world as my parish,” he said and began spreading the good news from Bristol to Norwich and from London to Glasgow. An enormously commanding speaker with a highly compelling message, Wesley was soon attracting audiences that numbered in the tens of thousands.

Eyewitness accounts of the preaching of John Wesley and George Whitefield, sometimes to outdoor crowds as large as eighty thousand people, attest to the awesome power of their presence. Dressed in long, black gowns with his locks flowing around his neck, Wesley usually spoke extemporaneously with fiery emotion about sin and hell, followed by a message of hope and a mood of blissful peace.

No sooner would he commence his sermon, than every eye involuntarily gazed with fixed attention upon the holy man of God. In fact, if you once fixed your eye upon him you could not take it off again. His musical voice conveyed the word with such power and effect that seldom was a sermon heard without the heart being touched, mellowed, and affected. The voice of Mr. Wesley was not so strong as it was fine, clear, and distinct, so much so that even . . . at the distance of one hundred and forty yards, persons . . . heard and understood the sounds of his voice.[9]

Whitefield, who had followed Wesley to Georgia, where his passionate and thunderous preaching sparked an American Great Awakening of religion in the 1740s (see chapter 13), was more Calvinist than Arminian in his theology but readily joined his former teacher in the great English Methodist crusade of bringing souls to Christ. The following account of his outdoor preaching in 1756 captures, if not his preaching style, then surely the popularity of his preaching:

When Mr. Whitefield arrived at Bristol, a platform was erected at the foot of a hill adjoining the town, whence he addressed the immense concourse of twenty thousand people. . . . Much as he was in the habit of public speaking and preaching to large and promiscuous multitudes, when he cast his eyes on the vast assemblage around him, and was about to mount the temporary stage, he expressed to his surrounding friends a considerable degree of timidity; but when he began to speak, an unusual solemnity pervaded the vast assembly. Thousands during the sermon, as was often the case, vented their emotions in tears and groans, and “Fools, who came to mock, remained to pray.”[10]

Not content to follow normal ecclesiastical channels, Wesley began to ordain a lay clergy of field preachers, “a church militant”—an itinerant ministry of zealous though untrained followers—and organized societies, or bands, of believers. Soon Methodist conferences, or parish districts, were organized with their characteristic systems of discussions, questions, and minutes, forming a new society or “a circle within a circle, a church within a church.” Condemned by the Anglican Church for exceeding his authority and for preaching a gospel of justification by faith detached from salvation through priesthood sacraments, Wesley, like Luther two centuries before, had never intended to start his own church. Though he ever considered himself an ordained clergyman of the Church of England, his labors eventually gave rise to the Methodist churches, so named in part because of their method of organization and desire to re-create the life and method of salvation as seen in the early apostolic church.

Traveling thousands of miles and preaching hundreds of times each year, visiting the sick, and organizing prayer groups wherever he went, Wesley became the “poor people’s friend.”[11] Beginning in 1769, Methodist preachers traveled overseas to America, the West Indies, Upper and Lower Canada, and soon afterward to Europe.

Ironically, the pessimism of Methodist doctrine—that man is innately evil and worthy of eternal damnation, if not utterly depraved, as Calvinism taught—was counterbalanced by the optimism of the free and proffered grace of Christ that brought peace, the warmth of forgiveness, and a surety of salvation that many longed for but could not find in the cold formality of Anglican liturgy and dogma. It was at once a personal and more approachable doctrine, more spiritual and hopeful and certainly more pertinent to daily living than what many had ever heard before.

Methodism found its most responsive audiences among England’s poor. As Halévy has further observed, “The despair of the working class was the raw material to which Methodist doctrine and discipline gave a shape.”[12] Wesley deliberately packaged his preaching and tailored his message to reach the collier and the factory worker, the fisherman and the farmer, often teaching in the fields before sunrise and then again at eventide. Soon bonfires of religious revival were aflame all over Britain. In many towns, preaching and prayer meetings were held every night and continued at times until two o’clock in the morning in what one observer called “a sin-killing, soul-saving, and spirit-quickening time.”[13] On some occasions, “all work ceased, whole families were brought under the influence of God’s Spirit; night and day the voice of prayer was heard to ascend from the dwellings of the people.”[14] And in many coastal villages, “fishermen held prayer meetings on board their vessels while anchored in the bay and even the sea resounded with the praises of the Most High.”[15]

A supremely gifted sermonizer, Wesley popularized the gospel message by bringing the church to the people where they lived and in what they did, meeting their spiritual, emotional, and physical wants rather than waiting for them to come to church to hear an erudite but distant sermon. As one early Methodist directive put it, “We strongly advise the preachers in their respective circuits, particularly in the more populous districts, . . . to avail themselves of every opportunity to preach in private houses, especially in the cottages of the poor . . . in order to obtain access to the more neglected part of our people.”[16] The persecution that these early Methodists suffered—false arrests, riots, unjustified jailings, mob violence, and senseless beatings, and these often at the initiation of the local parish priest—only fanned the flame of devotion higher.

While France was undergoing a secularizing revolution, Methodism rose so rapidly in popularity among the poor, the disenfranchised, and the working classes all over Great Britain that it remains difficult to refute Halévy’s thesis that Methodism was the antidote to revolutionary Jacobinism, a sort of anti-revolution, the influence of which “contributed a great deal . . . to preventing the French Revolution from having an English counterpart.”[17] More recent historians agree that popular evangelicalism did indeed make “a fundamental difference to the political stability of industrial England” and “produced a profound shift of allegiance in the nation as a whole.”[18]

Yet, for all of its successes, there developed a strong backlash to these Methodist advances. Albeit in a weakened state, the Church of England was still the dominant, established religion and began to actively resist Wesley’s advances. Not all its clergy were ravenous wolves or scribes and Pharisees. Many were good and noble men who cared deeply about their parishioners. Some serviced more than one parish but did so to eke out a living. Its bishops, while denouncing the Methodist fanatics, slowly but surely realized improvements had to be made. Moreover, the ruling class, the nobility, and the rich were deeply offended by the puritanical morality of Methodism and felt themselves too often the target of Wesley’s preaching. Others openly questioned how patriotic Methodism really was, how committed it was to England’s national and global interests. While succeeding among the lower classes, Methodism offended the rich and the powerful who were put off by religious piety and fanaticism and thus alienated itself from the very ones who could have transformed a stirring movement into a true societal reformation. After sixty years of Methodist revivals (1740–1800), there was not a single Methodist in Parliament, and very few were in business or among the gentry.[19]

Likewise, Christianity’s fight with sin and corruption among the high and the low, the princes and the prostitutes, was a never-ending war. Although there was arguably a general improvement in the moral tone of England in the latter half of the eighteenth century, Christian evangelicals focused on the corruption still so evident. “Sin wears a front of brass among us,” the Christian Guardian newspaper lamented in 1809, and a “veritable tide of evil,” as one person put it, engulfed the nation, particularly London, where at least thirty thousand female prostitutes, averaging age sixteen, roamed the streets—“the open female debauchery of the age,” as one put it. With prostitution came increased crime, violence, abortion, infanticide, and the breakdown of family values. Even the Church of England, while anxious to blame it all on the notoriously promiscuous French, admitted that it was an age of “luxurious habits, dissipated manners, and shameless profligacy. . . . Bastardy is now scarcely deemed a disgrace. . . . Adultery and concubinage in the lower classes of society are unhappily most prevalent.”[20] The age of elegance had deteriorated into the triumph of sin. One had only to look at the immorality of Prince George IV and Princess Caroline and others in the royal court to see what examples royalty cared about setting (see chapter 7).

“Measures, Not Men”

Onto this conflicted stage came one destined to change British society more profoundly than any reigning head of state and who in time became one of the foremost moral figures of the world. Born after his father’s death in the port city of Hull in 1759 into a nominally Christian home, William Wilberforce was raised by a childless uncle and aunt who had been previously evangelized by George Whitefield. In their careful religious enthusiasm, they introduced young William to one of the more remarkable men of the age: the kind, homely, old Calvinist divine—the Reverend John Newton (1725–1807). Author of the classic Christian hymn “Amazing Grace,” Newton firmly believed that God had a “controversy” with England because of its corrupt state. Wilberforce, an unassuming young man of small stature, was as humble as he was full of good humor. He endeared himself to the older Newton, who in turn enthralled his young pupil with exciting tales of maritime adventure. Newton had gone to sea at age eleven, deserted the navy, and eventually became the overseer of a slave depot on the Plantain Islands off the coast of Africa. A slave himself for two years until rescued by his father, Newton became a captain of a slave ship in 1750 and made several transatlantic voyages with human cargo, witnessing firsthand the awful inhumanities and cruel injustices of the slave trade. Pressed down with guilt for his sins and deep regret for the “wretch” he felt he had become, Newton—the “old African blasphemer,” as he called himself—saw his subsequent Christian conversion and call to the ministry as a miraculous rescue and a merciful personal redemption. He came to view his time with the young and impressionable Wilberforce as providential. Their friendship, built on trust, mutual admiration, and respect, would last a lifetime.

Portait of William Wilberforce (1794), by Anton Hickel.

Portait of William Wilberforce (1794), by Anton Hickel.

At age seventeen, Wilberforce set off to Cambridge, where, like so many of his contemporaries, he enjoyed the new and unrestrained life of a party goer. A talented singer and an easy conversationalist, but with a serious turn of mind, young Wilberforce made friends easily. Of all his Cambridge associates, none would come to play so great a role in his life as William Pitt (1759–1806), a son of the Earl of Chatham who was even then being groomed for a life in politics. In just seven years’ time, Pitt would rise to become prime minister of Great Britain at age twenty-four, the youngest in British history.

With Pitt’s election to Parliament, Wilberforce felt compelled to follow suit, a decision made possible by the death of his uncle William Alderman, who left him a sizable fortune (£30,000/

The two young Tory parliamentarians greatly complemented one another. Pitt was the brilliant debater, gifted speaker, and astute and respected politician, whereas Wilberforce was developing his own depths of passion, principle, and persuasive powers. The dynamic pair became animated in their youthful opposition to Lord North and England’s involvement in the American Revolutionary War (see chapter 11), which they both considered ruinous, cruel, and unwinnable.

While at times capable of vicious satire, Wilberforce was given to hospitality and the art of the gentle compromise. He also became known for his sterling integrity, unassailable personal morality, and independent thinking. Gaining the respect of friend and foe alike, Wilberforce was never predictable, never a safe bet to vote purely along Tory party lines. In 1783, he and some other members of Parliament formed a rump, or subparty of independents who renounced patronage and vowed never to be “raised” (bought out) to peerage in the upper chamber of the House of Lords.[21]

The following year changed Wilberforce’s life. While touring Europe with the openly Christian Isaac Milner (1750–1820), a Cambridge don, Wilberforce began a thorough study of the scriptures, a daily habit that would last a lifetime. Between their visits to various sites, the two men also read and discussed works such as Sir Francis Bacon’s (1561–1626) Essays and Philip Doddridge’s (1702–51) Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul. In due time, Wilberforce experienced the need for personal salvation and underwent a conversion so deep and soul-stirring that he returned to England a changed man. Upon visiting with Newton and listening to his sage advice, Wilberforce determined against a career in the clergy and decided to remain in politics and mingle with high societies of influence where he might effect change at the highest levels. “Measures, not men” became his personal motto, and he set about to reform society incrementally by living a life of personal holiness in a world of political vice and economic compromise.[22]

The “African Emancipator”

Perhaps it was Newton’s riveting stories of slave ship abuses or Wilberforce’s own innate sense of justice and mercy now quickened by his Christian conversion. Whatever the cause, Wilberforce, in 1787, began in earnest his unrelenting campaign to abolish England’s involvement in the African slave trade and to eventually free African slaves throughout the British Empire. It would prove to be a long and oftentimes discouraging fight against both the propertied and the prejudiced.

The Atlantic slave trade had begun with the Spanish and Portuguese as early as 1502 when conquered natives in Brazil and elsewhere in the Americas were understandably slow to accept slavery status and were dying off in very large numbers (see chapter 9). Consequently, frustrated overseers began to import enslaved Africans to do their bidding. The other colonial powers (British, French, and Dutch) had followed suit by midcentury, with England importing enslaved people to support its labor-intensive plantations in its Caribbean islands and southern colonies of North America. The importation of enslaved people soon became part of a highly lucrative triangular trade, consisting of carrying liquor and supplies from Europe to West Africa, then shipping enslaved people westward across the Atlantic and finally returning to Europe with ships now filled with sugar, lumber, and other produce—a three-part round trip that took up to eighteen months.[23] British defenders of the trade called it “the foundation of our commerce, the support of our colonies, the life of our navigation, and the first cause of our national industry and riches.”[24]

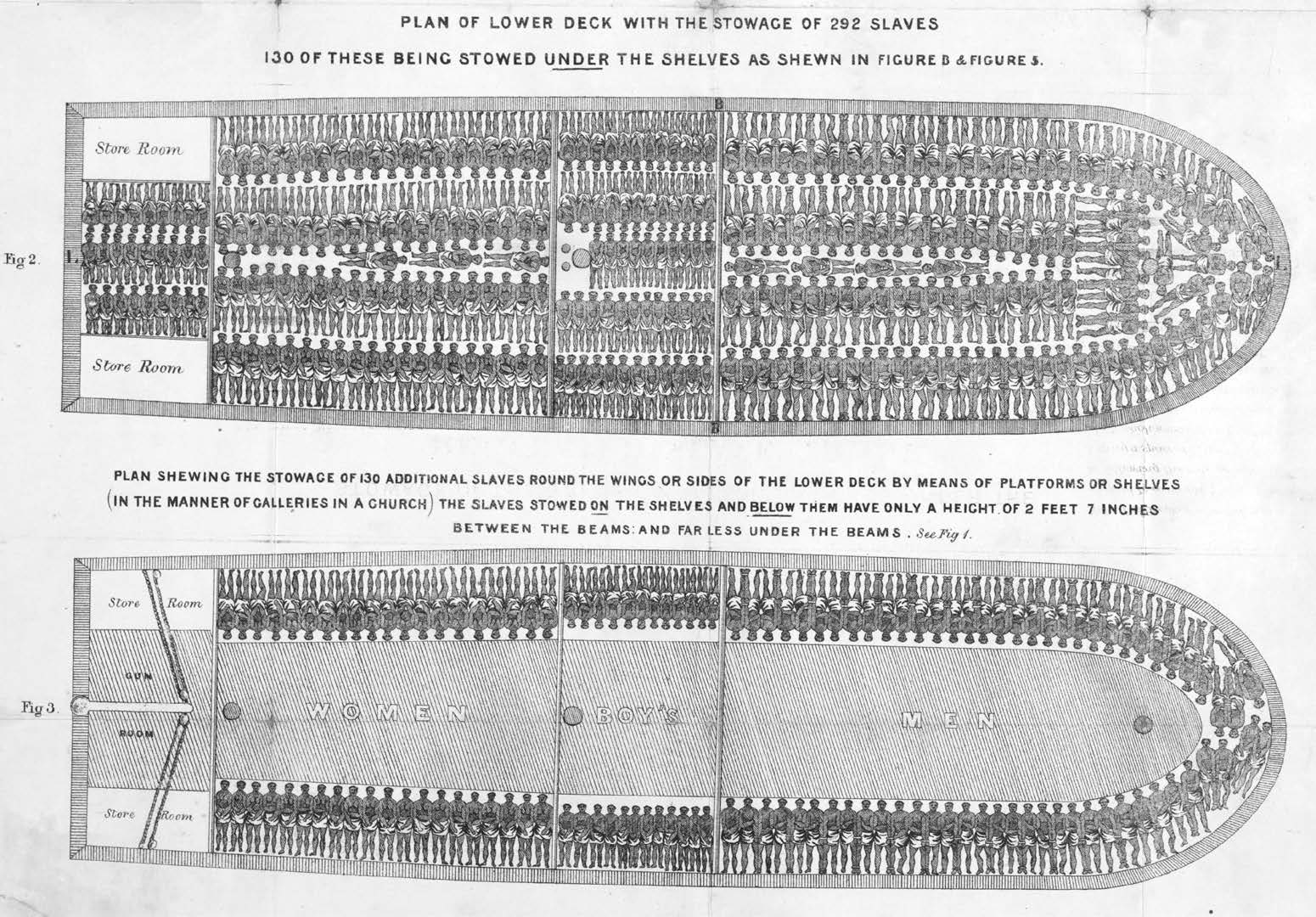

But some connected to this sordid business, such as the Reverend Newton, found it difficult, if not impossible, to defend so reprehensible a traffic in human suffering. Between 1760 and 1820, a minimum of almost four million enslaved Africans, both male and female, were forcibly uprooted from their tribal lands in the Congo and bought by slave ship captains. They were then chained and crammed… poorly ventilated lower decks (some only three feet high), where they endured unspeakable heat, filth, and squalor and the occasional flogging during their eight-week voyage across the Atlantic. Although fed reasonably well so that they, like cattle, could later fetch a decent price, many enslaved people mutinied, only to be tortured, wounded, or drowned. Upon arriving at Barbados or some other Caribbean port, ship captains sold enslaved people at scramble sales, or auctions, to plantation owners for the highest possible price, usually without concern for preserving family ties. During the entire 350 years of importation, some forty thousand ships brought over as many as eight to ten million black slaves!

One of the very few slaves who could write later recounted his reaction to living in a slave ship:

The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast was the sea, and a slaveship which was then riding at anchor and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon converted into terror when I was carried on board. I was immediately handled and tossed up to see if I were sound by some of the crew, and I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits and that they were going to kill me. . . . Indeed such were the horrors of my views and fears at the moment, that, if ten thousand worlds had been my own, I would have freely parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that of the meanest slave in my country. When I looked round the ship and saw a large furnace or copper boiling and a multitude of black people of every description chained together, every one of their countenances expressing dejection and sorrow, I no longer doubted of my fate; and quite overpowered with horror and anguish, I fell motionless on the deck and fainted. . . . Soon after this the blacks who brought me on board went off, and left me abandoned to despair.[25]

Atlantic slave-trade ship. Stowage of the British Slave Ship Brookes under the Regulated Slave Trade Act of 1788, published by the Plymouth Chapter of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Atlantic slave-trade ship. Stowage of the British Slave Ship Brookes under the Regulated Slave Trade Act of 1788, published by the Plymouth Chapter of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

And if Britain’s House of Commons Subcommittee reports are to be believed, some atrocities border on the incredible, as described in the following 1764 account by one crew member:

What were the circumstances of this child’s ill-treatment? The child took sulk and would not eat. . . . The captain took the child up in his hand, and flogged it with the cat. Do you remember anything more about this child? Yes; the child had swelled feet; the captain desired the cook to put on some water to heat to see if he could abate the swelling and it was done. He then ordered the child’s feet to be put into the water, and the cook putting his finger into the water, said, “Sir, it is too hot.” The captain said, “Damn it, never mind it, put the feet in,” and so doing the skin and nails came off, and he got some sweet oil and cloths and wrapped round the feet in order to take the fire out of them; and I myself bathed the feet with oil, and wrapped cloths around; and laying the child on the quarter deck in the afternoon at mess time, I gave the child some victuals, but it would not eat; the captain took the child up again, and flogged it, and said, “Damn you, I will make you eat,” and so he continued in that way for four or five days at mess time, when the child would not eat, and flogged it, and he tied a log of mango, eighteen or twenty inches long, and about twelve or thirteen pound weight, to the child by a string round its neck. The last time he took the child up and flogged it, and let it drop out of his hands, “Damn you (says he) I will make you eat, or I will be the death of you;” and in three quarters of an hour after that the child died. He would not suffer any of the people that were on the quarter deck to heave the child overboard, but he called the mother of the child to heave it overboard. She was not willing to do so, and I think he flogged her; but I am sure that he beat her in some way for refusing to throw the child overboard; at last he made her take the child up, and she took it in her hand, and went to the ship’s side, holding her head on one side, because she would not see the child go out of her hand, and she dropped the child overboard. She seemed to be very sorry, and cried for several hours.[26]

Wilberforce was not the first to decry the sordid spectacle of the slave trade. A groundswell of opposition had been developing for decades. Samuel Johnson, Charles Montesquieu, John Wesley, William Paley, Edmund Burke, Adam Smith, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, François-Marie Arouet (Voltaire), and scores of other eighteenth-century writers, philosophers, and religionists were adamantly opposed to it. Leaders of the French Revolution also roundly condemned slavery as a vicious attack on human rights and staunchly criticized the Roman Catholic Church for idly standing by in quiet sanction of a human abomination.

Most scholars agree, however, that the practice was so ensconced in the popular mind, so highly profitable to British and European colonial interests, so defended by various religionists as a decree of God and sanctioned by biblical slavery that only a well-financed, highly sustained, and inspired movement of widespread popular reform could ever discredit and destroy it. The Crown was too complacent, and the Church of England was ill-disposed to take on the fight, as were also the universities and capitalists. The labor movement led by William Cobbett was too busy with its own agenda (see chapter 7). As long as other European powers and America profited therefrom, why shouldn’t England? To abolish the slave trade would cause undue economic hardship to port cities all over Great Britain. The trade’s stout defenders, most often Tories and astute businessmen, increasingly articulated their concerns in direct proportion to the rising chorus of their critics. Thus, it would take nothing less than a nationwide religious crusade to dislodge the slave trade—which is precisely what happened.

Even before his conversion to evangelical Christianity, Wilberforce had been schooled in the inhumanities of the slave trade. Reverend Newton had seen to that. But Wilberforce was also greatly affected by James Ramsay’s disturbingly frank and critical Essay on the Treatment . . . of Slaves in the British Sugar Colonies.[27] When Wilberforce began his antislavery efforts in earnest in 1787, he remarked, “I confess to you . . . so enormous, so dreadful, so irremediable did its wickedness appear, that my own mind was completely made up for the abolition.”[28]

The coalition for change and reform began in 1790 with the Clapham Sect (Clapham was a small suburb of London), made up of such leading and influential evangelical Christians as Wilberforce (MP), Henry Thornton (MP) (1760–1815), the Reverend John Venn, Charles Grant, Isaac Milner, Zachary Macaulay (1768–1839), Thomas Babbington, Lord Teignmouth, and Hannah More. The Clapham Sect became a formidable agent for improving society in many ways but took initial and special aim at slavery. Christ died for all humankind, they asserted, and his Atonement applied to all. Because he came to free humankind from spiritual bondage, how could physical bondage ever be biblically condoned? And with the same fervency with which many believed they had been saved from their own shackles of sin, so they would now attack the shackles of human slavery at whatever the cost to personal fame or reputation. If slavery’s defenders drew on the Old Testament for support, the evangelical Christian drew upon the New Testament to denounce it. And while some may disagree that religion was the driving force behind British abolitionism, it was, as one of the foremost scholars on the slave trade put it, “precisely because of [Wilberforce’s] predominantly spiritual concern that he was so sensitive to the slavery issue.” These evangelical Christians came to see a “superintending Providence,” a kind of urgent, ever-intensifying “continuing divine revelation” from a God intent on change. And they believed ardently, as did the Reverend Newton, that England would forever stand condemned of God until and unless this curse was lifted.[29]

To the work of the Clapham Sect must be added that of another powerful religious influence—the Society of Friends, better known as the Quakers. Although in 1806 there were only some fifty thousand Quakers then living in England and another forty thousand in the United States (mostly in Pennsylvania), their moral influence and reputation for integrity, equality, and fairness far outweighed their numbers. Believing in true brotherly love and Christian charity and piety and opposed to war and conflict, the Quakers believed that all men were created equal and that slavery was an immoral affront to God. Led by such leaders as Anthony Benezet (1713–84) and John Woolman (1720–72), the Quakers had begun attacking slavery as early as 1750. Perhaps their greatest role was one of adding an early and deeply moral conscience and inspiration to the crusade.

Religious arguments alone, however, could hardly have turned the tide. There were also changing political and economic factors at play that an astute Wilberforce, situated as he was as a close friend of Pitt and as an ever more highly respected member of Parliament, could see and understand and use to full advantage. The campaign for abolition lasted for twenty years (1787–1807) before culminating in the passage of the Abolition Act in 1807. The fundamental reasons for its success may be attributed to the following: (1) publicity and the power of the press; (2) a highly successful grassroots organization; (3) intensive research into the abuses of the trade; and above all (4) Wilberforce’s powerful and winsome personality, his reputation for integrity, and his ever increasing popularity among the rich, powerful, and influential classes of society. Religious but not preachy, converted but warmly sociable, secure in his faith but a friend to all, Wilberforce spoke the language of the Bible and of the barroom equally well.

Poets and pamphleteers, printers and publishers lent their talents to publicizing the wrongs of slavery. Of all these many writers, none was as widely read, respected, and revered as Hannah More, arguably more popular than William Wordsworth, Samuel T. Coleridge, or Sir Walter Scott, at least for a time. More was the primary pamphleteer and moralist of the age, and in her poem “The Slave Trade,” published in 1787, she captured the injustices of slavery as perhaps none of her colleagues could have ever done. Appealing to the British sense of fair play and love of liberty, she quietly rallied millions to abolition’s banner as is perhaps most keenly felt in her poem “The Slave Trade, from Thoughts on the Importance of the Manners of the Great to General Society.

“The Slave Trade”

. . . Perish the illiberal thought which would debase

The native genius of the sable race!

Perish the proud philosophy, which sought

To rob them of the powers of equal thought!

Does then the immortal principle within

Change with the casual colour of a skin?

Does matter govern spirit? or is mind

Degraded by the form to which ‘tis join’d?

No, they have heads to think, and hearts to feel,

And souls to act, with firm though erring zeal,

For they have keen affections, kind desires,

Love strong as death, and active patriot fires.

. . . Whene’er to Africa’s shores I turn my eyes,

Horrors of deepest, deadliest guilt arise;

I see, by more than fancy’s mirror shown,

The burning village, and the blazing town:

See the dire victim torn from social life

The shrieking babe, the agonizing wife;

She, wretch forlorn! is dragged by hostile hands,

To distant tyrants sold, in distant lands!

Transmitted miseries, and successive chains,

The sole sad heritage her child obtains!

. . . What wrongs, what injuries, does oppression plead

To smooth the crime and sanctify the deed?

What strange offence, what aggravated sin?

They stand convicted—of a darker skin!

. . . Though dark and savage, ignorant and blind,

They claim the common privilege of kind;

Let malice strip them of each other plea,

They still are men, and men should still be free.

. . . Shall Britain, where the soul of freedom reigns,

Forge chains for others she herself disdains?

Forbid it, Heaven! O let the nations know

The liberty she loves she will bestow;

Not to herself the glorious gift confined

She spreads the blessing wide as humankind;

And, scorning narrow views of time and place,

Bids all be free in earth’s extended space.[30]

While the writings of Hannah More, Reverend Newton, Thomas Clarkson, Anthony Benezet, William Cowper (“The Negro Complaint,” 1788), and John Wesley (Thoughts upon Slavery, 1774) were becoming ever more popular in the broadways of thought, the careful organization of the abolitionist campaign at the town and village level—the capillaries of society—was likewise critical to its success. Often borrowing from Methodist organizations and their successes, local abolition committees (usually led by Quakers and evangelical Christians) promoted the cause through correspondents, informal meetings, house visits, speaking tours, local petitions, and the active dissemination of abolitionist literature. Gradually the very conscience of the nation became tormented.

Yet for all of this, there was persistently strong opposition to the abolitionist movement, and a cacophony of arguments was raised against it. The propertied and capitalist classes of society, so well represented in the Tory Party, maintained that slavery was in the best economic interests of western England, particularly for such port cities as Bristol, Liverpool, and Lancashire. They argued that chimney sweeps and dairymaids were treated far worse than slaves; that Africa was overpopulated; that many more blacks suffered and were butchered to death in the Congo than in the plantations of the Caribbean; that if England unilaterally withdrew from the trade, far less principled American, French, and Spanish slave interests would predominate and ruin the British colonies; and that with the Napoleonic Wars about to break out, there were more important matters to debate. Even if the abolitionist crusade was morally right, this was no time for change.[31]

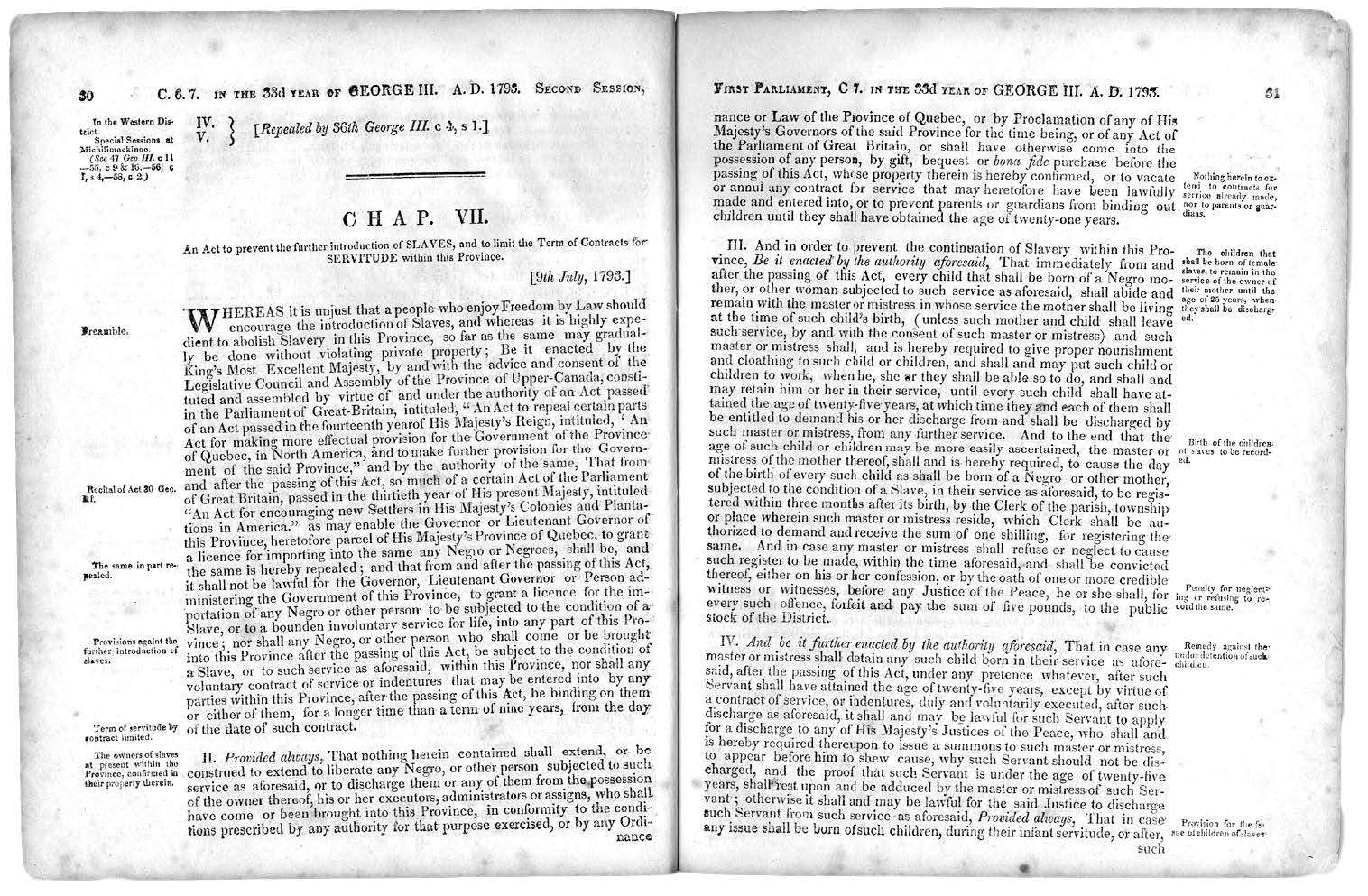

Act to Prevent the Further Introduction of Slaves and to Limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude within This Province, Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada.

Act to Prevent the Further Introduction of Slaves and to Limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude within This Province, Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada.

Because of these and related reasons, the abolitionist movement stalled time after time. Hard-liners against Napoléon branded the abolitionists, including Wilberforce and the Whigs, as pro-French revolutionaries for wanting to weaken the labor force of British colonies for the benefit of France. When word arrived of a Nat Turner–like slave uprising and bloody rebellion on the British isles of Grenada, Dominica, and St. Vincent in 1795 in which slaves killed many of their white masters, the movement almost failed entirely. Time after time Wilberforce tabled a bill for abolition—often to the embarrassment of his fellow Tories—only to see it defeated by significant majorities.

However, with French and Spanish privateers importing West Indian sugar at much cheaper prices than the English colonies could ever sell it for, with Napoléon’s European embargo making English trade on the continent ever more difficult, and with the Tory defeat in 1806, the abolitionist campaign began to catch its stride. The final death knell of the pro-slavery economic argument may well have been Lord Horatio Nelson’s (1758–1805) stunning victory at Trafalgar in 1805 and the subsequent British naval mastery of the seas. Why continue to use British slave ships to supply labor to French and Spanish colonial possessions in Central and South America? In a word, why abet the enemy?

When the ultimate passage of the Foreign Slave Trade Bill finally occurred in a cheering House of Commons on 23 February 1807, it came by “a more overwhelming” vote than anyone could have ever predicted—283 to 16—a moral, humanitarian, and religious victory over the long combined forces of economic and political self-interest. Exactly one month later, the bill passed the House of Lords by a vote of 100 to 34 and received royal assent on 25 March with the act taking effect on 1 May 1807. A long, dark night had finally come to an end. The abolition of the British slave trade eventually proved the death knell for slavery in Britain and in all its colonies. Twenty-six years later, another bill was passed—the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833—that freed over eight hundred thousand slaves and effectively abolished slavery forever in the British Empire.

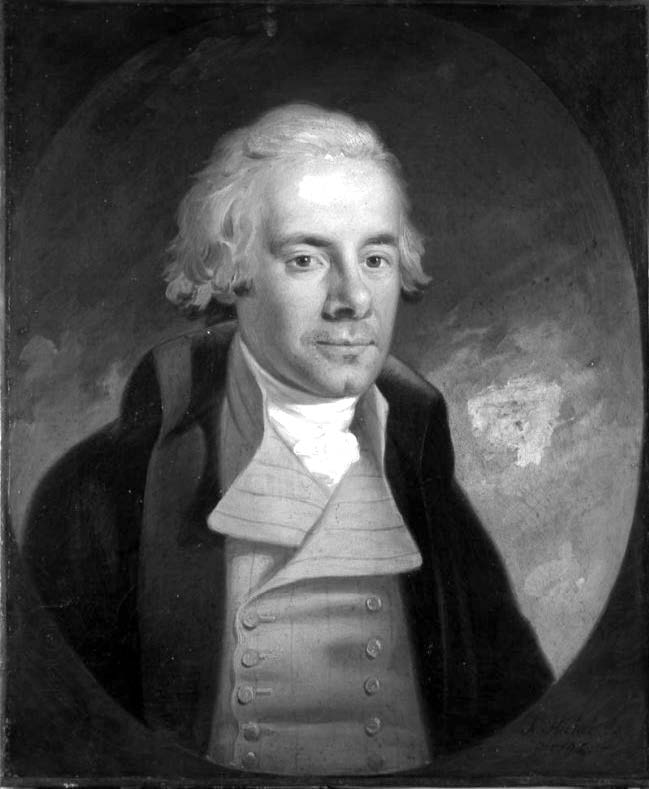

Bishop in Petticoats: Hannah More

While Wilberforce was changing attitudes in the House of Commons, Hannah More was reaching the houses of commoners all over Britain. Born in Stapleton in 1745 to a strong-willed Protestant schoolmaster father who taught in poor country districts near Bristol in west England, More was the fourth of five sisters, all of whom were well educated and groomed to become teachers themselves. Believing that women should be educated beyond the traditional domestic roles, her oldest sister, Mary, began a very successful boarding school in Bristol in 1758 for girls of wealthy families and invited the likes of Charles and John Wesley, the astronomer James Ferguson, and William Wilberforce to come and lecture. “The Sisterhood,” as the More sisters came to be known, were “men’s women” in that they were strong-minded, energetic, deeply religious, and committed to educating young women and young men.[32]

Mrs. Hannah More, Popular Graphic Arts.

Mrs. Hannah More, Popular Graphic Arts.

Like her sisters, Hannah never married, so dedicated were they to their work and to one another. However, her wealthy onetime fiancé, Edward Turner (1788–1837), set up an annuity for her of £200 as a way of extricating himself from the engagement, helping finance her later writing career. Her first love was the theater, and in the 1770s, Bristol, then rich in wealth from the overseas triangular trade, was the busiest theater city outside of London. At age sixteen Hannah wrote her first play, The Search after Happiness: A Pastoral Drama” (1773), a work that showed her early interests in promoting Christian virtues and innocent amusements, especially among young women. Before long, she took to writing tragedies (The Inflexible Captive [1775], Percy, A Tragedy [1777], and more complex plots), leading her to London, where she became an enthusiastic admirer of the immensely popular David Garrick (1717–79), whom many considered the greatest actor of his age. She even wrote “Ode to Dragon” as a poetic tribute to Garrick upon his 1777 retirement from the stage. While in London she became acquainted with Dr. Samuel Johnson (1709–84), the renowned writer and critic, who favored her work. He called her “the most powerful versificatrix” in England and encouraged her to pursue a literary and theatrical career.[33] She had other admirers as well—the critic Horace Walpole (1717–97), the historian Edward Gibbon (1796–1862), and the statesman Edmund Burke (1729–97). Even Coleridge dedicated one of his plays to her, and John Wesley encouraged her in her literary pursuits.

Garrick’s death in 1778 devastated the young poet and playwright, and though she remained in contact with Mrs. Eva Garrick, More “gradually turned against the stage” and the oftentimes sordid living of many in the theater business, convinced that there were better avenues for her increasingly moralistic and deep-toned religious convictions.[34] As one of her recent biographers put it, she realized that “the theater was ineffective in propagating godliness.”[35]

Returning to live and work with her three sisters (Elizabeth, Mary, and Martha More), she resumed teaching in the country schools near Bristol, but with a difference from before. Following the example of Robert Raikes (1736–1811) of Gloucester, who had founded the nondenominational Sunday School movement in 1780, she and her sister Martha (1747–1819) began their Cheddar school in October 1789 with financial backing from Wilberforce and other Clapham reformers. Raikes’s amazingly successful and rapidly expanding system of Sunday Schools, which were usually held in homes or barns on Sunday afternoons or evenings, taught destitute boys and girls how to read by studying from the Bible and singing gospel hymns, how to dress in clean clothes, and how to learn to be honest and morally upright. It was a grassroots, primarily evangelical movement that struck an extremely responsive chord all over Great Britain.[36] It stirred the imagination of educators like the Mores while embarrassing and frustrating the established but out-of-touch church that, once again misreading the needs of the people, saw it all as little less than Methodist propaganda.

The Cheddar school represented a blended form of secular and religious education and aimed primarily at educating poor children with financial support of the lords of the manor and of others who had means. Held on Sundays as a Sunday School and on some weeknights for training in various literary skills, personal behavior, domestic arts, and more, the Cheddar school proved highly popular and soon expanded into the nearby coal-mining districts. Some of the weekday classes were held to teach mothers how to read as well as to instruct them in knitting, sewing, and other domestic skills.

Committed to remaining steadfastly single, Hannah adhered to a very rigid, almost puritan form of personal conduct, including strict Sabbath observance, no playing cards, no dancing, strict temperance, a concentrated study of the scriptures and little else, and a carefully self-scrutinized form of individual obedience. As she once phrased it, “My Bible has been meat, drink and company to me.”[37]

Hannah More’s religious convictions were deeply rooted in her belief in the Fall of Adam and the need for Christ as a personal Savior. In a letter she wrote in 1820 she said:

I cannot conceive that the most enchanting beauties of nature, or the most splendid production of the fine arts, have any necessary connection with religion. . . . Adam sinned in a garden too beautiful for us to have any conception of it. . . . The distinctive nature of Christianity [means] a deep and abiding sense in the heart of our fallen nature; of our actual and personal sinfulness; of our low state, but for the redemption wrought for us by Jesus Christ; and of our universal necessity of a change of heart and the connection that this change can only be effected by the influence of the Holy Spirit.[38]

Religious commitment meant far more to her than merely accepting Christ—it meant consistently living a life of personal holiness and consecration. “The two great principles on which our salvation must be founded are faith and holiness; faith, without which it is impossible to please God, and holiness, without which no man can see the Lord.”[39] Given to severe headaches and repeated bouts of depression, Hannah retreated into the life of a virtual religious hypochondriac. Keeping detailed notes of all her sins and shortcomings, “she was never sure that she had won what she passionately desired—God’s complete approval.”[40]

Committed to humanitarian causes, Hannah gravitated toward the Clapham Sect and the rapidly expanding evangelical and antislavery movement. Aware of her talents as a writer, Wilberforce and the Anglican bishop of London and private chaplain to King George III, Beilby Porteus (1731–1809), urged her to get out of herself and write popular moralistic stories and uplifting ballads to support the aims of the Clapham Sect. Such was the beginning of her early tract writing that soon mushroomed into scores of inexpensive Repository Tracts, which sold for mere shillings with a reading audience soon in the millions. By 1795 “the great Evangelical propagandist,” as she was coming to be known, was writing a new tract every month, published on coarse brown paper with lively woodcuts, the likes of which included Village Politics, by Will Chip, a Country Carpenter; The History of Idle Jack Brown; The Story of Sinful Sally; and by far her best-known work, The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain, based on a true character (which sold two million copies in four years!). In just three years’ time, she wrote thirty-nine Repository Tracts, becoming both rich and famous in the process.

She also found time to write several popular books of essays of similar tone and purpose, including Thoughts on the Importance of the Manners of the Great and General Society (1788), An Estimate of the Religion of the Fashionable World (1790), Hints for Forming the Character of a Young Princess (1805), and her most famous book and only novel, Coelebs in Search of a Wife (1809), an essay on how to choose a good wife, which went through twelve editions its first year. Deeply religious, platitudinous, and highly moralistic in tone, her writings established her reputation as “the most greatly respected woman of the Christian world.”[41]

Her book Thoughts on the Importance of Manners, which appeared in seven editions in one year, took special aim at the rich and powerful classes of society, “the good kind of people” who were “the makers of manners,” and gently admonished them in how to live true Christian lives and help the less privileged to do the same. “Believe and forgive me,” she pleaded, “reformation must begin with the great or it will never be effectual.”[42]

If her essays took aim at the rich, her tracts were designed in large part to convince the poor to find better ways to live than to criticize the rich and wish for a better world. “Be honest, be industrious—Anything is better than idleness, sir.” “Pay down your debts, count your blessings, submit to the lot God has appointed you, and be content with all that you have save your sins.” As her poor Shepherd on Salisbury Plain put it to the rich nobleman: “My cottage is a palace!” and “I have health, peace, and liberty, and no man maketh me afraid.” “God is pleased to contrive to make things more equal than we poor, ignorant, short-sighted creatures are apt to think.”[43]

More’s fabulously popular The Importance of Manners called not just for improving manners but also for acquiring a new religious disposition. While complimenting on the one hand—“A good spirit seems to be at work. . . . We have a pious King; a wise and virtuous [prime] minister, very many respectable . . . clergy,” and “an increasing desire to instruct the poor”—she could be blisteringly critical on the other: “May I venture to be a little paradoxical,” she asked while rebuking the “shining counterfeit” of many doing good but not really changing. “Is it not almost ridiculous to observe the zeal we have for doing good at a distance, while we neglect the little, obvious, every day domestic duties?”[44] “What is morally wrong can never be politically right,” she chided. “Reformation must begin with the great, or it will never be effectual. Their example is the fountain whence the vulgar draw their habits, actions and characters. To expect to reform the poor while the opulent are corrupt, is to throw odours into the stream while the springs are poisoned.”[45]

In her Estimate of the Religion of the Fashionable World, More showed herself far more than a poet or a storyteller or admonisher for good, but a highly intelligent defender of Christianity. Scolding those whose “practical irreligion” saw Christianity as merely a perfect system of morals, while they deny its divine authority,” she wrote: “As noble as the principle itself is, [it] has engendered a dangerous notion, that all error is innocent. Whether it be owing to this, or to whatever other cause, it is certain that the discriminating features of the Christian religion are every day growing into less repute; and it is become the fashion, even among the better sort, to evade, to lower, or to generalize, its most distinguishing peculiarities.”[46]

Believing there was little of Christ in the Christianity of her day, she asserted that Christianity was more than merely doing good: “It is a disposition, a habit, a temper; it is not a name, but a nature.”[47] Strict obedience, whether keeping the Sabbath holy or daily reading the scriptures, is what brings “perfect freedom.” “It is a folly to talk of being too holy, too strict, or too good,” any more than it is to be “too wise, too strong, or too healthy,” for the heart must change. To More, Christianity was all-encompassing, a religion that “must be embraced entirely, if it be received at all.” If it is to be anything, “we must allow it to be everything.”[48]

What explains More’s meteoric rise in popularity? To answer this question is to capture the prevailing mood of contemporary English society. England was a religious country, anxious to get more religion than the established church knew how to give. Most people were the rural poor and the uneducated and identified more with her plain and powerful stories and parables than they did with the erudite and distant sermon. Having seen firsthand the sufferings of the poor, More spoke to their poverty, their family conditions, their longings—in a word, she understood them.

While calling on the rich to do much more to provide for the poor, she also criticized the lower classes for their greediness, for regarding appearances too much, for even thinking of revolting against the system—inviting them to be happy and content with what God has provided and look to a better world hereafter. “To fear God and honour the King—to meddle not with them who are given to change—To not speak evil of dignitaries—to render honour to whom honour is due.”[49] Above all, More preached with paper and pen that “sin is the great cause and source of every existing evil,” that “sin is a greater evil than poverty, that personal reformation, not political revolution, was all that most mattered.”[50] Her lively, simple, and persuasive style of writing inspired many readers, especially women, to improve their literacy and education while tending the hearth and home. Although she was more of a religious family traditionalist than many modern feminist scholars might prefer, More was nevertheless ahead of her time as an educator, religious spokeswoman, and philanthropist.

Yet there was more to Hannah More’s writing than religion: not a political agitator, she nonetheless had very strong economic, political, and patriotic convictions. She believed the gentry had a God-given duty to look after the worthy poor, that government had no social responsibilities to feed the poor, and that God, who knows best, will provide in his own time and way. She despised the French Revolution and Napoléon’s growing sinister shadow, Tom Paine’s Rights of Man and the anti-British aims of the recent American Revolution, and the secular humanitarian Robert Owen.[51]

More staunchly believed that British royalty was a God-given institution despite its flaws. Such a stance explains her popularity with even the upper classes. Likewise, she feared that the rising trade union and democratic movements and wrenching agricultural changes in England would destroy an established and trusted way of life. In her mind, there was no pressing need for a social or political gospel that emphasized widespread societal improvements. What was most needed was changing one’s individual life for the better through daily acts of strictly chaste and righteous living: “A man can’t talk like a saint and live like a sinner.”[52] She urged discontent with personal sins more than society’s problems and finding happiness in personal reformation, not public revolution. Outliving all her sisters, More spent her declining years at Barley Wood in the Mendy’s Hills and later in Clifton, where her home became a shrine for thousands of admirers who came from all over Britain, the Continent, and North America. Until the end, she was an inveterate letter writer, and copies of her correspondence are now scattered in libraries and archives all over the Western world. Disposing of most of her fortune to various charities and religious societies, she died 7 September 1833 at the age of eighty-eight and was buried with her sisters in Wrington churchyard.[53]

Real Christianity

One year before the appearance of More’s Importance of Manners, Wilberforce published his own Christian manifesto titled A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians in the Higher and Middle Classes in the Country, Contrasted with Real Christianity (1797). An enduring classic in modern Christian literature, Real Christianity is a stirring, book-length essay on deep-seated, evangelical Christian faith and a thoroughly scripture-based invitation—and warning—to the British upper classes to come unto Christ and change their worldly ways. Reminiscent of Martin Luther’s “Here I Stand” declaration over two centuries before, and Coleridge’s later Aids to Reflection, Real Christianity was Wilberforce’s personal declaration of belief. Written between 1789 and 1797 while Wilberforce was a sitting member of Parliament, Real Christianity might have branded a lesser man as a Christian do-gooder and mere moralistic preacher. Instead, the book was quickly revered as a reflection of the highly respected character of the author and, as such, a work to be seriously regarded. As England’s most esteemed humanitarian in the war against the slave trade, child labor, and the exploitation of women in the work force, Wilberforce was a highly respected figure. Unlike More or even Wesley, Wilberforce was more intellectually and artistically in the world than out of it, more connected to the rich and the socially influential, and thus spoke with a powerful credibility other religionists could not then feign to obtain.

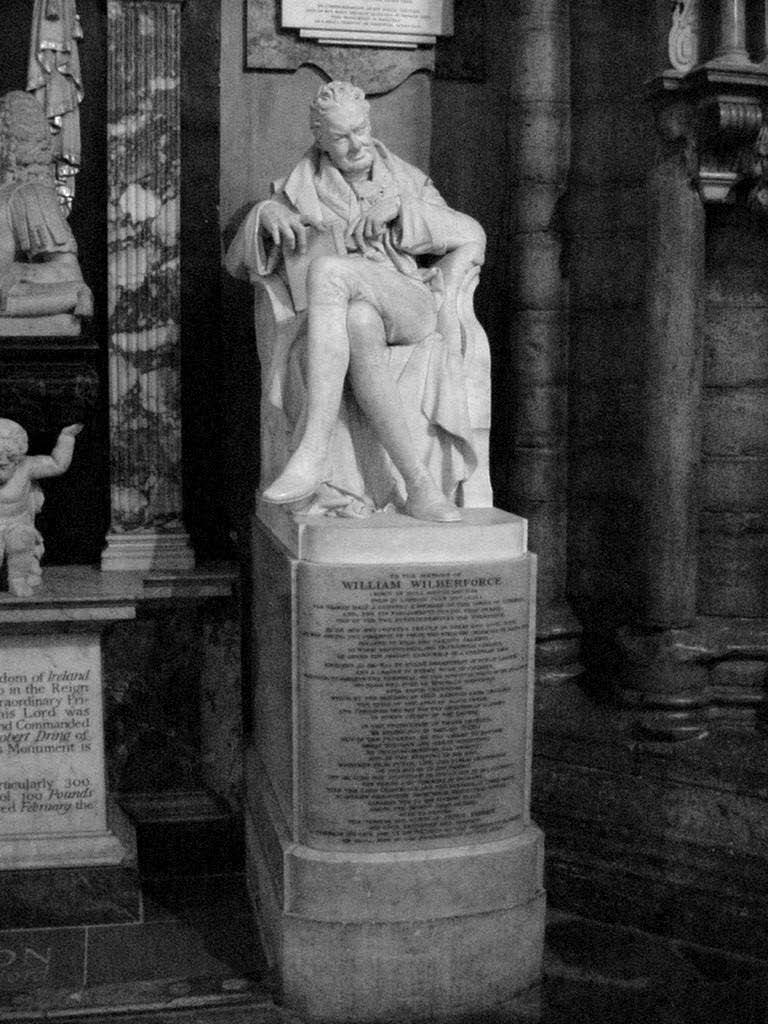

Memorial to William Wilberforce, by Samuel Joseph.

Memorial to William Wilberforce, by Samuel Joseph.

In some superficial ways, Wilberforce echoed More’s writings. He, too, criticized Sabbath breakers, the debauchery of the theater, the writing of corrupt and evil novels, and other outward manifestations of sin. Yet, as a patron of the arts (he had cofounded the National Galleries), Wilberforce was no narrow-minded religious zealot. While decrying mere “nominal,” “geographic,” and “general” Christians (a nation Christian in name only), Wilberforce probed deeper than had Hannah More in deciphering the true nature of what he called “a religion of motives,” a “radical or essential Christianity.” While complimenting royalty and the influential classes for their benevolence and good desires, he, like Coleridge, believed that most people “advance principles and maintain opinions altogether opposite to the genius and character of Christianity” and that too many neglected the Bible and turned from the gospel “as a thing of no estimation.”[54]

His work emphasized four principal elements: the root cause of societal decay, the essential Christian solution, a call for voluntary change and a whole-scale reformation, and finally, a warning. The primary reason for England’s malaise, or “fatal malignancy” as he viewed it, was the sin of pride, which he defined as “a disposition in each individual to make self the grand centre and end of his desires and enjoyments.”[55] To have lost the sense of guilt and the evil of sin and its malignancy was sin enough, but to revel and rebel in “that proud self-complacency so apt to grow upon the human heart” was humanity’s great weakness.[56] In words later echoed by twentieth-century writer C. S. Lewis (1898–1963), Wilberforce believed that “we do not set ourselves in earnest to the work of self-examination.” And humility, the “vital principle of Christianity, [is] its only antidote.”[57] Pride inoculated one from changing, and those guilty of it viewed Christianity as nothing more than “a cold compilation of restraints and prohibitions, . . . a set of penal statutes” that “stressed external actions rather than the habits of the mind.”[58] Because of pride, “a system of decent selfishness is avowedly established” and the sensual pleasures predominate. He observed that England’s main desire was “to multiply the comforts of affluence, to provide for the gratification of appetite, to [have] . . . magnificent houses, grand equipages, high and fashionable connexions [sic].” England’s heart is “set on these things.”[59] Pride, he argued, is the very opposite of love, whereas humility “will prevent a thousand difficulties,” and it “changes all to gold.”[60]

Thus the “main object and chief concern of Christianity” was “to root out our national selfishness,”[61] to counter it with benevolence, moderation, humility, and meekness. This solution and societal change would come not by conforming to outward rules and laws but by confirming the affections of the fallen heart on Jesus Christ, the “blessed Savior” and “Redeemer.” “For all our moral superiority, . . . we are altogether indebted to the unmerited goodness of God”[62] and his “undeserved grace.”[63] Through the “atoning sacrifice” of Jesus Christ and his death at the cross, “Christianity became far more than a creed, a rational system of ethics or morality, but the perfect contrast to Epicurean selfishness, . . . stoical pride, . . . and cynical brutality.”[64]

To all the above admonitions, he sounded this note of warning: if England and its higher classes in particular do not reform and repent, no amount of military or financial strength will ever save her. A sterling patriot, Wilberforce nonetheless said, “My only solid hopes for the well-being of my country depend not so much on her fleets and armies, not so much on the wisdom of her rulers, or the spirit of her people, as on the persuasions that she still contains many who love and obey the Gospel of Christ.” “We bear upon us too plainly the marks of a declining empire,” and “God will be disposed to favour the nation to which his servants belong.”[65] England must no longer be Christian in name only. “Every effort should be used to raise the depressed tone of public morals” or else a France-like state of “moral deprivation” will ensue.[66] Without such changes, the time will soon come, he warned, “when Christianity will be almost as openly disavowed in the language, as in fact it is already supposed to have disappeared from the conduct of men; when infidelity will be held to be the necessary appendage of a man of fashion and to behave will be deemed the indication of a feeble mind and a contracted understanding.”[67]

Of all the important accomplishments of our age of 1820, few were as momentous as the abolition of the British slave trade and, in its wake, the eradication of slavery within the British Empire. Against insuperable odds, William Wilberforce, Hannah More, and a host of other humanitarian leaders successfully waged a war against prejudice, bigotry, economic disparity, and human degradation in its meanest expressions. Theirs was a victory for the ages, and it characterized the strivings and struggles of the period of our study for a better world. And in the process, they also stamped on the coming Victorian age an expectation of a new order of Christian living, a change of heart and mind that far transcended the commonplace and the ordinary.

In retrospect, one has to wonder how The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints could ever have made the inroads it did in Great Britain in the late 1830s and early 1840s without John Wesley’s religion preparations among the poorer classes of society. For it is a well-known fact that a majority of its early covenants were Methodists of one kind or another, and many were discontent with their social and economic lot in a rapidly changing British Society.

Furthermore, the untiring efforts of Wilberforce. More, and countless other towards the successful abolition of the Slave Trade gradually resulted in a growing spirit of emancipation, tolerance, and respect that would slowly counter long held attitudes of pride and prejudice, even among those who considered themselves devoutly Christian.

Notes

[1] Roberts, Comprehensive History of the Church, 6:252.

[2] Halévy, Birth of Methodism in England, 1–3.

[3] Semmel, in the introduction of Halévy, Birth of Methodism in England, 14.

[4] Halévy, Birth of Methodism in England, 12.

[5] Gilbert, Religion and Society in Industrial England, 12.

[6] Gilley, “The Church of England in the 19th Century,” in Gilley and Shields, History of Religion in Britain, 293–94.

[7] Harwood, History of Wesleyan Methodism, 20–21.

[8] Baker, “Wesley Brothers,” in Eliade, Encyclopedia of Religion, 15:370.

[9] Walker, History of Wesleyan Methodism in Halifax, 84.

[10] Walker, History of Wesleyan Methodism in Halifax, 84, 95.

[11] Aspland, Rise, Progress, and Present Influence, 23.

[12] Halévy, Birth of Methodism, 8.

[13] Brownsword, “Extracts of Journals,” 19.

[14] Ward, Brief Sketch of Methodism in Bridlington and Its Vicinity, 25.

[15] Ward, Brief Sketch of Methodism in England, 25.

[16] From “Minutes or Journal of the Conference of the People Called Methodists,” vol. 2.

[17] Halévy, Birth of Methodism, 51.

[18] Hampton, “Evangelicalism and Reform, c. 1780–1832,” in Wolffe, Evangelical Faith and Public Zeal, 24–28.

[19] Brown, Fathers of the Victorians, 16, 22–24.

[20] Brown, Fathers of the Victorians, 46.

[21] Belmonte, William Wilberforce, 18–65.

[22] Belmonte, Wilberforce, 70–94.

[23] Anstey, Atlantic Slave Trade and British Abolition, 34–37.

[24] An African Merchant [John Peter Demarin], A Treatise upon the Trade from Great Britain to Africa, 7, as cited in Anstey, Atlantic Slave Trade, 36–37.

[25] Edwards, Equiano’s Travels, 25–26, as cited in Anstey, Atlantic Slave Trade, 27–28.

[26] A crew member, “Britain’s House of commons subcommittee Report,” as cited in Anstey, Atlantic Slave Trade, 33.

[27] Ramsey, Essay on the Treatment . . . of Slaves.

[28] Belmonte, William Wilberforce, 109.

[29] Anstey, Atlantic Slave Trade, 191, 198.

[30] In the Miscellaneous Works of Hannah More, 1:209–11.

[31] Anstey, The Atlantic Slave Trade, 303.

[32] Hopkins, Hannah More and Her Circle, 25.

[33] Brown, Fathers of the Victorians, 76–77.

[34] Hopkins, Hannah More, 102–3.

[35] Ford, Hannah More, 43.

[36] Royle, “Evangelicals and Education,” in Wolffe, Evangelical Faith and Public Zeal, 121. In 1800 the number of students enrolled in British Sunday Schools barely reached 200,000. By 1851 there were over two million, and by 1881 there were 5.7 million! The Sunday School movement later inspired the rise of elementary schools after 1840. Richard Ballantyne (1817–98), a Scottish convert founded the Sunday School of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in December 1849 that continues to the present time.

[37] More, The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain, 15.

[38] Hannah More to Mr. and Mrs. Huber, 1820. In Roberts, Memories of the Life and Correspondence of Mrs. Hannah More, 4:139.

[39] Roberts, Memories, 4:147.

[40] Hopkins, Hannah More, 199.

[41] Brown, Fathers of the Victorians, 98.

[42] Brown, Fathers of the Victorians, 101.

[43] More, ’Tis All for the Best, in The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain and Other Narratives, 45, 50, 52.

[44] More, ’Tis All for the Best, in The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain and Other Narratives, 45, 50, 52.

[45] More, Importance of Manners, 293.

[46] More, Estimate of the Religion of the Fashionable World, in Miscellaneous Works of Hannah More, 1:302.

[47] More, Fashionable World, 306.

[48] More, Fashionable World, 333–34.

[49] From The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain, as cited in Brown, Fathers of the Victorians, 144.

[50] Brown, Fathers of the Victorians, 155.

[51] Thomas Paine (1737–1809), an Englishman who moved to America to save his life, was a radical critic of establishment politics and religion. His essays Common Sense (1776), The Rights of Man (1791), and The Age of Reason (1794/

Robert Owen (1771–1858) of Scotland was a benevolent factory master who believed in education reform and fairer working conditions for the working class. Regarding himself as “the prophet of the new age,” Owen was a deist, a socialist, and a rationalist thinker who gave little regard to Christianity. He believed that if ever a new world order or millennium were to come, it would be built by man, human reason, and humanitarianism, not by the return of a savior. Royle, “Secularists and Rationalists,” 408 (see chapter 7 herein).

[52] More, Religion of the Fashionable World, 329.

[53] M. K. Smith, “Hannah More: Sunday Schools, Education and Youth Work,” in The Encyclopedia of Informal Education.

[54] Wilberforce, Real Christianity, 9–14.

[55] Wilberforce, Real Christianity, 337.

[56] Wilberforce, Practical View, 137.

[57] Wilberforce, Real Christianity, 251, 375.

[58] Wilberforce, Real Christianity, 156, 159.

[59] Wilberforce, Real Christianity, 144, 147.

[60] Wilberforce, Real Christianity, 376–77.

[61] Wilberforce, Real Christianity, 340.

[62] Wilberforce, Real Christianity, 180.

[63] Wilberforce, Real Christianity, 253.

[64] Wilberforce, Real Christianity, 208.

[65] Wilberforce, Real Christianity, 411.

[66] Wilberforce, Real Christianity, 349–50.

[67] Wilberforce, Real Christianity, 317.