From Plymouth Rock to Palmyra

Joseph Smith Jr., the Second Great Awakening, and the Quest for Divine Truth

Richard E. Bennett, “From Plymouth Rock to Palmyra: Joseph Smith Jr., the Second Great Awakening, and the Quest for Divine Truth,” in 1820: Dawning of the Restoration (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 317‒42.

“Some time in the second year after our removal to Manchester [New York], there was in the place where we lived an unusual excitement on the subject of religion. It commenced with the Methodists, but soon became general among all the sects in that region of country. Indeed, the whole district of country seemed affected by it, and great multitudes united themselves to the different religious parties, which created no small stir and division amongst the people, some crying ‘Lo, here!’ and others, ‘Lo, there.’”[1] So wrote the Latter-day Saint prophet Joseph Smith Jr. (1805–44) of the scenes of religious intensity, turmoil, and confusion that permeated much of western upstate New York in the winter of 1819–20. “I was at this time in my fifteenth year,” he further recalled.

My father’s family was proselyted to the Presbyterian faith, and four of them joined that church, namely, my mother, Lucy; my brothers Hyrum and Samuel Harrison; and my sister Sophronia. . . . In process of time my mind became somewhat partial to the Methodist sect, . . . but so great were the confusion and strife among the different denominations, that it was impossible for a person young as I was, and so unacquainted with men and things, to come to any certain conclusion who was right and who was wrong. . . . I at length came to the determination to “ask of God.”[2]

This book culminates in a study of an early American boy prophet’s quest for divine truth, but will do so by endeavoring to place it within the larger context of American religious history. In the words of Jan Shipps, Joseph Smith may have begun “a great new religious tradition,” but he was very much a product of his family, time, and place.[3]

“I Covenanted with God”

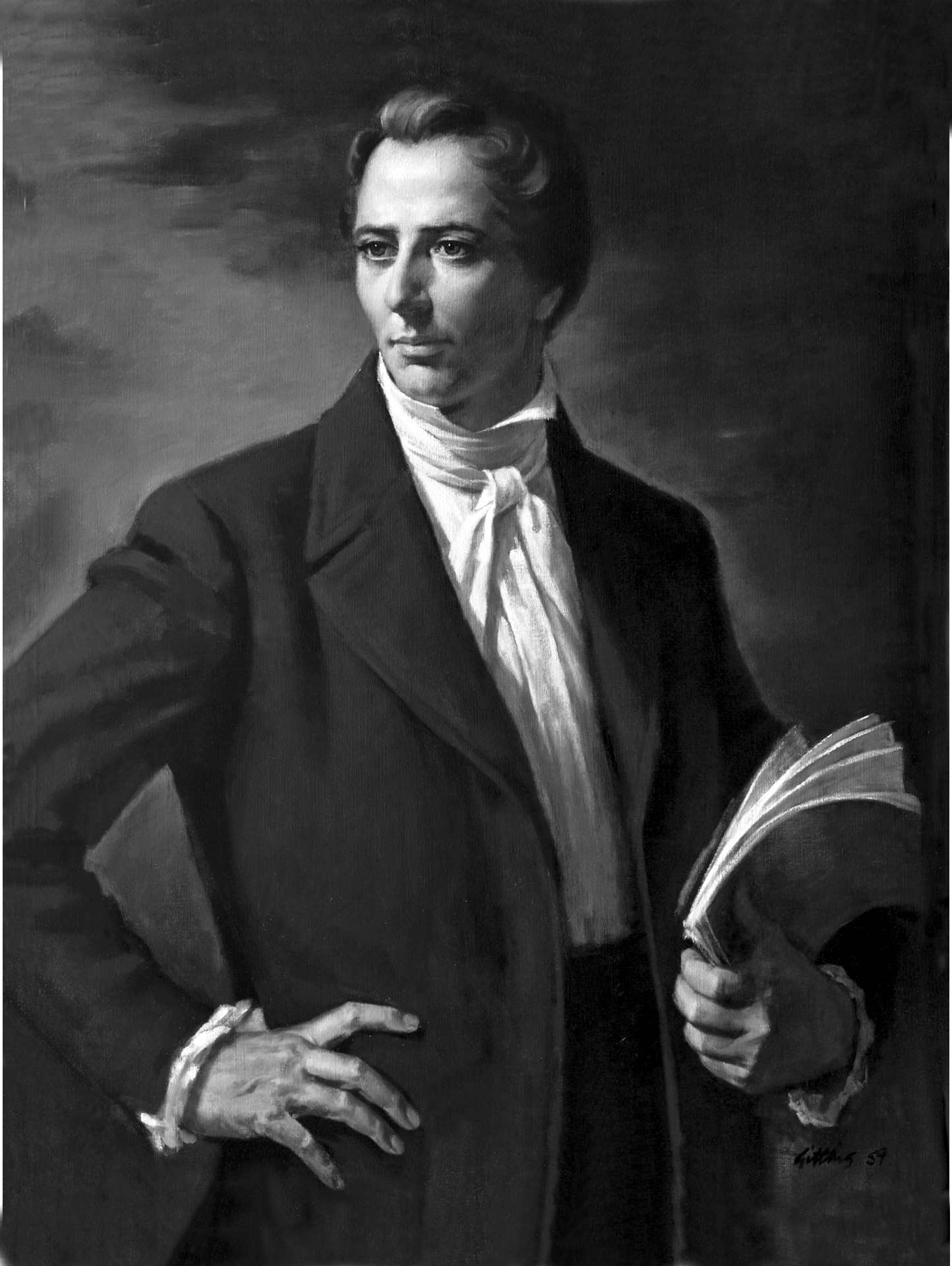

Joseph Smith Jr., by Alvin Gittins. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Joseph Smith Jr., by Alvin Gittins. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Joseph Smith Jr. was born in a crude cabin on a cold, wintry 23 December 1805 in the town of Sharon, Windsor County, Vermont, the fourth child of his farmer father, Joseph Smith (1771–1840), and devout mother, Lucy Mack Smith (1775–1856). A determined, hardworking, and deeply religious woman, Lucy had found God in her own difficult life for at least three reasons. The first was her father, Solomon; the second was a painful near-death experience; and the third was her husband’s own quest for spiritual truth.

The youngest of eight children, Lucy was the daughter of Solomon Mack (1735–1820), son of Ebenezer Mack. Solomon was born in Connecticut and had fought in the king’s service during the French and Indian War (1754–63), barely escaping with his life at the bloody Battle of Ticonderoga in 1758. Later he fought against the British in the American Revolutionary War as a naval gunner. Marrying young schoolteacher Lydia Gates in 1759, Solomon failed at almost everything in life—whether as a farmer, seafarer, or businessman. Prone to accidents and even shipwrecks, and vulnerable to swindlers and poor judgment generally, Solomon lived a careless and profligate lifestyle for most of his adult life, barely able to support his family in their various moves from one part of New England to another. When afflicted with a terrible siege of rheumatism in the winter of 1810–11 at the age of seventy-five, however, his life was dramatically transformed as he prayed as never before for his health, forgiveness, and salvation. In a forty-eight-page self-published autobiography titled A Narrative of the Life of Solomon Mack, a penitent Solomon wrote:

I prayed to the Lord, as if he was with me, that I might know it by this token—that my pains might all be eased for that night. And blessed be the Lord, I was entirely free from pain that night. And I rejoiced in the God of my salvation—and found Christ’s promises verified. . . . Everything appeared new and beautiful. Oh how I loved my neighbors. How I loved my enemies—I could pray for them. . . . The love of Christ is beautiful. There is more satisfaction to be taken in the enjoyment of Christ [in] one day than in half a century serving our master, the devil.[4]

Solomon spent his declining years in service to God, family, and friends before his death in Gilsum, New Hampshire, in August 1820.

Some few years before her father’s conversion, Lucy had undergone a near-death experience of her own. While living in Randolph, Vermont, a few years after her marriage, Lucy came down with “a hectic fever” sometime in the fall of 1802 that almost claimed her life. Freely admitting that at the time she was unprepared to die, she sensed “a dark and lonely chasm between myself and Christ that I dared not attempt to cross.” After her husband and several doctors gave her up to die, the twenty-seven-year-old Lucy desperately covenanted with God that if he would let her live, she would endeavor “to get religion that would enable me to serve him right, whether it was in the Bible or wherever it might be found, even if it was to be obtained from heaven by prayer and faith.”[5] On hearing a voice declare, “Seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you,” Lucy miraculously recovered from her illness.[6] As a seeker of true religion, she began attending one church after another, favoring at first the Methodists but finally finding a minister who baptized her but left her free from membership in any particular church. Right up to the Palmyra area revivals of 1819–20, Lucy, though firm in her Christian devotions, was looking for something more. She ultimately joined the Presbyterians.

In addition to her own conversion as well as her father’s changed life, Lucy came to religion by yet another way. Historians have commonly described her husband, Joseph Smith Sr., as a nondenominational, almost Universalist in his religious leanings, as was certainly the case with his father, Asael Smith. However, Joseph Sr., unlike others in his family, was a man of recurring dreams and visions.

Joseph Sr. was a descendant of Robert Smith, who emigrated from England in 1638 at the height of the Puritan immigration and settled in Topsfield, eight miles north of Salem, Massachusetts. Robert’s son, Samuel, was a highly esteemed citizen, and his grandson, Asael, briefly fought in the Revolutionary War. A Congregationalist with Universalist leanings, Asael “owned the [Congregationalist] covenant” and “promised to live an upright and moral life.”[7] Asael’s marriage to Mary Duty in 1767 resulted in a large family, including Joseph Sr., who was born in 1771.

At age twenty-five, Joseph Sr. married Lucy Mack in 1796 in Tunbridge, Vermont, where their two oldest children, Alvin and Hyrum, were born before moving to Royalton and then later, Sharon, where Joseph Jr. was born. Their marriage was off to a promising economic start until Lucy’s husband was swindled out of almost all they owned, owing to an overseas ginseng trade deal that went sour.[8] Moving seven times in fourteen years from one rented farm to another, Joseph Sr. finally resolved to pull up stakes and moved to greener pastures in 1816 after the “year without a summer.”[9] After locating a new rented farm, he sent word to Lucy to bring the family to start a new life in Palmyra, New York, some thirty-five miles southeast of Rochester.

When Lucy told of their early efforts in Palmyra to eke out a living, eventually making a modest down payment on a hundred-acre farm straddling the townships of Palmyra and Manchester, she also referred to her husband’s dreams and religious searching. In 1808 a series of religious revivals engulfed the Royalton, Vermont, region, so much so that Father Smith became “much excited” on the subject of religion. As he “contemplated the confusion and discord that were extant” among the various Christian religions, he “contended for the ancient order”[10] of religious truth—embarking on a spiritual quest very similar to that which his son would later follow.

Joseph Smith Sr. had at least seven dreams, the earliest of which Lucy called “The First Vision of Joseph Smith, Sr.” Most of them shared a common element of a field, a spiritual guide, a broad and narrow path, a stream or river of water, a rope running along its banks, a large building in the distance, and a tree, “exceedingly handsome” and beautiful with fruit of “dazzling whiteness.”[11] It was after his seventh dream in 1819 during a great revival near Palmyra in which his guide said, “There is but one thing that you lack,” that his son Joseph Jr. set out on his own prayer of discovery.[12] Thus family dynamics and a sincere, deep-seated family quest for religious truth prepared their son Joseph Jr. for a religious quest of his own. Yet there were other, broader factors at play more general and far-sweeping than the intimate family inquiries described above, for 1820 was by all accounts a very special year in American religious history.

“A City upon a Hill”

Speaking of the “peculiar benignity of a superintending Providence” in a sermon delivered in New York City in 1820, the Reverend Gardiner Spring (1785–1873) reminded his congregation that the year 1820 marked the two hundredth anniversary of the coming of the Pilgrims to Plymouth Rock in 1620. Taking as his text Psalm 107:7, which reads “And he led them forth by the right way, that they might go to a city of habitation,” Dr. Spring rehearsed with deep devotion the causes and details of the Puritans’ coming so long before. He saw it, as did many others before him, as fulfillment of a divine grand design. Quoting the Reverend Jonathan Edwards, he said, “We may well look upon the discovery of so great a part of the world as America, and bringing the Gospel into it, as one thing by which Divine Providence is preparing the way for those glorious times, when Satan’s kingdom shall be overthrown throughout the whole habitable globe.”[13]

While lauding the Puritans and their immediate descendants who had made the New England wilderness “blossom as the rose” and made the desert “become as the garden of the Lord,” Spring decried the decay in faith since those earlier days. In so doing he lamented the apostasy of these latter times, “an apostasy that involved the rejection of all the essential articles of the Christian faith; all that is binding in the plenary of the Holy Scriptures; all that is precious in the hopes of the Gospel; and all that is holy in a Christian walk and conversation; and all that is solemn in the retributions of the eternal world.”[14]

Reverend Spring’s sermon embodied a recurring sentiment expressed in American religious thought in both the Great Awakening of the 1740s centered in New England and its sequel, the Second Great Awakening from 1800 to 1830 farther west and south: to remind America of its deeply Christian roots, to revive the covenant of grace that brought the Puritans to New Plymouth in the first place, and to reclaim and convert to Christ a new generation of Americans who had lost their way in the wilderness. To look back, therefore, on American religious history was characteristic of 1820.

The Puritans who came to New England’s rocky coast in 1620 were unquestionably a deeply Christian people. Derisively labeled Puritans by their English persecutors, who felt their desires to purify the Anglican Church were overly zealous, more than eight hundred of these wandering Pilgrims, or Separatists, sought refuge first in Amsterdam in 1606 and later in Leyden, Holland. In their view, King Henry VIII had not gone nearly far enough in distancing the Church of England from the apostate rituals, corrupt priesthood, and unholy performances of the clergy of the Roman Catholic Church.[15]

Fundamental to the Puritan argument was the centrality of individual spiritual experience and the supremacy of the Bible over the “tyranny of the Papacy.” Puritanism was “an emotional dissent,” or, as Patrick Collinson described it, “a hotter sort of Protestantism.”[16] The mainspring “of all their protests,” as historian George Ellis has argued, was “the simplicity that was in Christ,” “the word versus the Church,” and sola scriptura—that is, the scriptures were the sole and final religious authority, not a Roman Catholic pope or an English archbishop.[17] They wanted a reversion to simplicity and to the “first principles” of gospel living and envisioned a church without priesthood hierarchy, superstition, or ceremony. Queen Elizabeth I and her successor, King James I of Scotland, had done precious little to make needed ecclesiastical change, and when King James decreed in 1603, “No Bishop, No King,” the Puritans saw no other solution but exile.

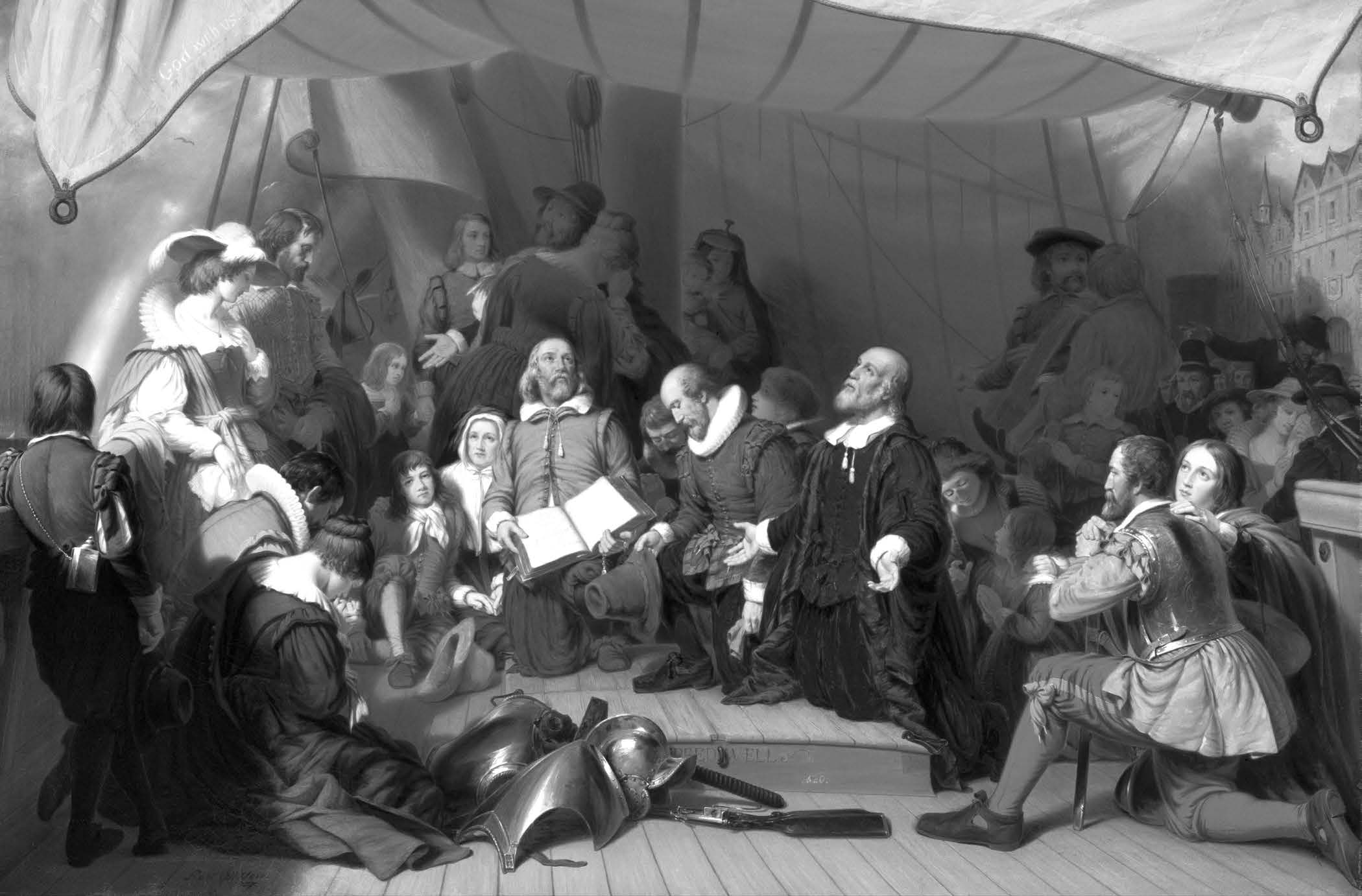

Embarkation of the Pilgrims, by Robert W. Weir.

Embarkation of the Pilgrims, by Robert W. Weir.

Fearing the loss of their English customs and language, if not their religious convictions, and promising the king full obedience, the Puritans secured a patent from the new Virginia Company, England’s first American colony of 1606, to establish their colony in the New World.[18] Sailing aboard the Mayflower, 102 would-be settlers left Southampton on 5 August and made the transatlantic voyage under difficult and crowded circumstances before finally anchoring off Plymouth Rock on 26 December 1620. Plagued by sickness and malnutrition, many perished in their rather crude settlement that first harsh winter, including their original governor, John Carver. Surely more would have died had it not been for the “social compact” they had signed to assist and govern one another. By 1630 New Plymouth had grown from a single plantation to eight towns along the shore of Cape Cod, consisting of 2,500 souls.

A second wave of Puritans, less persecuted and less strident than the first but still called Nonconformists, arrived in Massachusetts Bay beginning in 1624 and continuing until 1628 under the direction of the Cambridge-educated John Winthrop (1588–1649). Though Governor Winthrop and his Massachusetts Bay Colony of planters denied any intention of separating formally from the Church of England, after moving to Salem they soon established a church separate from the Church of England—the Congregational Church—and abandoned use of the Book of Common Prayer. Decimated by scurvy and malnutrition like their Plymouth Colony settlers some sixty miles to the south, they too barely survived their first winter. Still, they did not regret their coming. “I do hope that our days of affliction will soon have an end,” Winthrop wrote in a letter to his wife. “We here enjoy God and Jesus Christ. Is not this enough? What would we have more? I thank God. I like so well to be here, as I do not repent my coming.”[19] In 1642, four years after Robert Smith, Joseph Smith’s great-great-grandfather, immigrated to America, the two Pilgrim colonies, now numbering more than thirty thousand, combined into the United Colonies of New England.

Winthrop fervently believed that God had led them to the New World not to found a new nation but to reform the old in their new Zion community. “Through a special overvaluing providence,” their coming was, in Winthrop’s famous words, “to be better preserved from the common corruptions of this evil world, to serve the Lord and work out our own salvation under the power and purity of his holy ordinances.” And they would do so by covenant. “Thus stands the cause between God and us. We are entered into covenant with him for this work. We have taken out a commission.”[20] Their keeping of such a “covenant of grace” with the God of the New Testament and their “being knit together by this bond of love” would result either in permanent blessings or in endless damnations. “We must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill,” Winthrop wrote in A Model for Christian Charity.[21] But if righteously obedient they would bless themselves, England, and the whole world by hastening the time of the Second Coming of Christ and by ushering in the long-sought-for millennial day.[22]

John Cotton (1584–1652), who arrived in Boston in 1633 with another eight hundred settlers and who became the generally recognized spiritual leader of the colony, likewise saw it all as God’s doing. “The placing of people in this or that country is from God’s sovereignty over all the earth,” he said.[23] Edward Johnson (1598–1672), who wrote the first history of New England in 1648, said, “These are but the beginnings of Christ’s glorious reformation and restoration of his churches to a more glorious splendor than ever. . . . Will you not believe that a nation can be born in a day?”[24] Peter Bulkeley (1583–1659) reiterated their covenant theology when he too wrote of their being “a city on a hill,” “a special people,” a New Jerusalem in the making. “Heaven and earth . . . will cry shame upon us, if we walk contrary to the covenant which we have professed and promised to walk in.”[25]

Such a covenant required strict conformity to the Puritan way of Christian living and thought. It would not countenance dissent of any kind. Anne Hutchinson (1591–1643) and Roger Williams (1603–83) found that out the hard way. Critical of many of her Puritan leaders for what she perceived as their lack of spiritual zeal and an increasingly works-and-rewards-driven soteriology, Hutchinson soon found herself banished to that new colony for outcasts—Rhode Island. Roger Williams, a strident Separatist, soon followed her for believing that John Cotton and other Puritan divines were liberalizing the purity of the faith and minimizing a “by grace only” salvation.

“Errand into the Wilderness”

With the passage of time, however, the earlier passion of conversion became increasingly hard to maintain. By 1670 some second-generation Puritans sensed that much had gone wrong with what the Reverend Samuel Danforth called “New England’s Errand into the Wilderness.” Increase Mather and other second-generation Puritan leaders began speaking of a growing “apostasy,” while Michael Wigglesworth (1631–1705) called it “God’s controversy with New England.”

There were reasons for such drift. In 1662 King Charles II reaffirmed the Massachusetts Bay Charter but, in lessening Puritan authority, demanded that all but the openly reprobate be granted baptism and other sacraments. Many new settlers were Anglicans who resisted Puritan Congregationalism. Thomas Hooker (1586–1647) formed a new colony in Hartford, up the Connecticut River, in 1636. Though the Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut colonies were equally religious and devout, fissures were beginning to appear in Puritan solidarity.

And though Puritanism was essentially Calvinistic in its theology, as scholar Perry Miller has noticed, the Calvinist belief in election or predestination, the transcendent sovereignty and redeeming grace of God in Christ, and humankind’s total depravity were gradually being modified to allow for a more Arminian belief in human free will, the saving value of good works, and heartfelt faith and repentance.[26] The constant struggle for survival in the harsh wilderness led inexorably to a sense of accomplishment, of achievement, of well-deserved profits, and of a grateful reliance tinged with personal pride. As Thomas Morton (1575–1646) wrote, “If this land is not rich, then is the whole world poor.”[27] Taming the wilderness bred a new frontier-style individualism and sense of personal accomplishments that balked at a theology of absolute determinism and humankind’s nothingness.[28]

These and other factors led to the adoption of the so-called Half-Way Covenant of 1662, a watershed moment in Puritanism’s decline. This compromise essentially was a begrudging admission that a great many second-generation settlers had never made the profession of faith required for full membership in the Congregationalist Church. Before 1662, children of such halfway members could not be baptized, but with the Half-Way Covenant they would now at least be treated as church members, even if they had not experienced the same soul-changing experience that had qualified their fathers. It was a religious rapprochement, a regression that allowed membership for new generations of members like Joseph Smith’s ancestors, Samuel and Asael Smith, but did not guarantee them the right to partake of the Lord’s Supper.

Jonathan Edwards and the Great Colonial Awakening

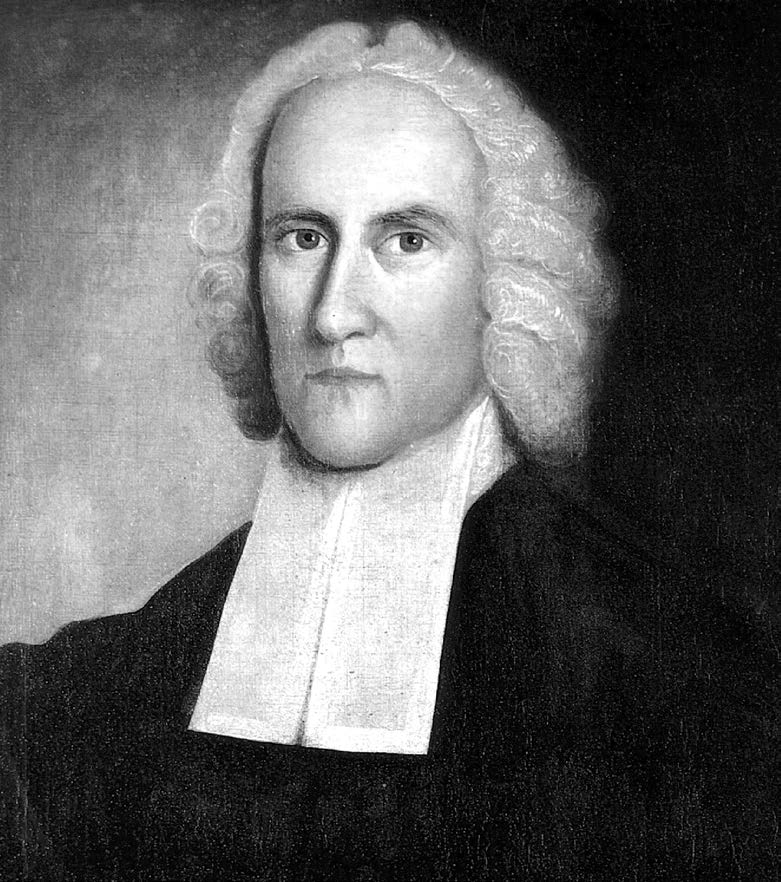

Jonathan Edwards, by unknown artist.

Jonathan Edwards, by unknown artist.

Jonathan Edwards (1703–58) of Northampton, Massachusetts, a child of both Puritanism and the wilderness, kindled an unparalleled revival of religious fervor in 1739–40.[29] Edwards called this religious phenomenon “a flash of lightning” on “the hearts of the people.”[30] Blessed with an uncanny ability to infuse old doctrines with new meanings through a radical reformulation of language and metaphor, Edwards was both a caring pastor and a towering intellect. His lasting work, A Treatise Concerning Religious Affections, called for deep emotion in one’s conversion, not mere stylistic conviction. Arguing that “the heart of true religion is holy affection,” Edwards believed in the love and beauty of God and the need for believers to feel their way to Christ and conversion.[31] As he once said: “He that has doctrinal knowledge and speculation only, without affection, never is engaged in the business of religion. . . . True religion is a powerful thing, . . . a ferment, a vigorous engagedness of the heart.”[32] Through his masterful sermonizing, including his famous “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” (1741), Edwards convinced thousands of the unchurched and halfway religionists to repent of their sins and convert to the Christ of their Puritan forefathers. With his blending of a fear for God but belief in a God who loved, Edwards made religion and religious emotion “theologically and intellectually respectable.”[33]

Calling on George Whitefield (1714–70), the well-known English Methodist itinerant preacher and spell-binding orator, to help push the work forward with him, Edwards fathered the Great Awakening all over New England and the Atlantic Seaboard and as far south as Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia.[34] Other evangelists included Theodore J. Frelinghuysen (ca. 1691–ca. 1747), a Dutch Reformed minister in New Jersey, and Gilbert Tennent (1703–64), of Pennsylvania. As Richard Bushman has written, “People could not get enough of preaching.”[35] And this from Benjamin Franklin: “It seemed as if all the world were growing religious; so that one could not walk through the town in an evening without hearing Psalms sung in different families of every street.”[36]

The message was much the same as before, but with a softer tone: All were sinners, if not enemies of God, bound for damnation; no amount of their good works could ever save them; all were justified by faith alone; and their increasing New England prosperity served only to augment a guilty conscience. Edwards and company emphasized more than before eternal rescue through the freely accepted grace of Christ, a salvation that “dissolved uncertainty and fear” and ensured to every true seeker the joy of rebirth.[37] The Great Awakening taught a much more optimistic expression of Christian faith than Puritanism ever did, and for many their conversion brought about a new sense of peace and joy that would last a lifetime.

Aimed at all classes of people, the Great Awakening was an awakening of another sort. It was, arguably, a democratic movement.[38] As Perry Miller has argued, it was a revolution, a populist movement, an awakening to the power and influence of the people as a whole to demand a more personalized religion that spoke to all of them, not just a favored few. Edwards must be seen as a transitional figure in the rise of individualism and democracy in the colonies because he gave the people a voice. [39]

By midcentury the Great Awakening had subsided, but not before converting tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, while also giving rise to Rutgers, Dartmouth, Princeton, and Brown universities—all based on a deeply Christian premise.[40]

“Increasing Apathy and Coldness”: 1750–1800

For all its profound impact, the Great Awakening could last only so long and reach only so many people. In fact, some scholars are now arguing that it never did have the influence many have long assumed, that it was far more localized and scattered in nature than a general outpouring of the Holy Spirit.[41] This debate promises to continue, but it is generally agreed that during the ensuing years in the last half of the eighteenth century, other urgent priorities and compelling schools of thought were competing for the hearts and minds of the American colonists. These cultural forces might best be categorized in three ways: intellectual, political, and social.

Rising in opposition to the Calvinist Puritan doctrines of the total depravity of humankind, God’s election of grace, and the sovereignty of God in Christ Jesus was deism—that theological product of the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and the age of reason. As opposed to atheism, deism provided place for a creator God, but one who, after creation, left the world on its own without interfering collectively or individually in the affairs of humankind. Rejecting a belief in the Trinity, human depravity, the need of a Savior, and miracles and revelations, deism claimed that one came to truth by way of reason, not by revealed religion, and that man was the source of his or her own salvation. The devotion of Voltaire and Thomas Paine, deism was human-centered and democratic in its tendencies and counted such famous early American disciples as George Washington, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson. Believing in God’s benevolence, generosity and all-forgiving nature, deists practiced, as Bernard Weisberger has written, a nice “rational religion.”[42]

A sort of halfway house between deism and Puritan Calvinism was Unitarianism. It attempted to “reconcile the lion of God’s almighty power” and majesty with God’s affection for his children or creations on the one hand and humanity’s use of intellect on the other. In trying to unite both ends of the God-man spectrum, Unitarianism was essentially a difficult compromise between revealed Christianity on the one hand and the religion of reason on the other. By 1820 Unitarianism had gained a particularly strong foothold at Harvard and Yale as a favored religion of the more highly educated.[43]

In the political realm, the rising spirit of democracy and a growing climate of restless independence led inexorably to the American Revolutionary War. Ironically, the Great Awakening, with its message of obedience and dependency on God, may well have contributed to the Revolutionary War by instilling in its adherents a sense of power, personal liberty, and conviction and a resistance to former authorities and institutions.[44]

The political results of the war are well known; no less far-reaching were its religious ramifications. The Church of England, which supported the Loyalist cause (as did the Quakers), fell out of favor with many Americans and was disestablished as the government-supported religion. So too Congregationalism was eventually disestablished in New Hampshire (1817), Connecticut (1818), and Massachusetts (1833). Meanwhile, Unitarianism and deism flourished, as did a new liberal religious expression—Universalism—and its contention that in the end, all humanity would be universally saved anyway.

As regards the social realm, historians generally agree that during the closing years of the eighteenth century, church attendance noticeably declined throughout the new American nation. As Catharine Cleveland noted over a century ago, since the American Revolution an “increasing apathy and coldness” in church involvement and devotion, coupled with rising immorality, had filled religious leaders with “apprehension and alarm.”[45]

Many of these independent thinkers moved to the expanding frontier of the United States of America. Others, like the Loyalists, fled to the British colonies of Upper Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, resulting in the emptying of more churches in New England and the Eastern Seaboard states than any other factor. And with what Reverend Timothy Wright of Yale University once called an “unregenerate frontier,” many turned to violence and alcohol, “the haunt of vicious men.”[46]

The Second Great Awakening

Ironically, this westward migration sowed the seeds of the Second Great Awakening (ca. 1798–ca. 1835), a term evangelists deliberately employed to link them and their work to the former Great Awakening of Jonathan Edwards, George Whitefield, and William Tennant. This new generation of evangelists saw their day as an age of reformation and restoration and of preparing anew for Christ’s Second Coming.[47] Christianity was hardly dead in the new republic. The Church of England, Congregationalism, and Presbyterianism all survived the war, but they were eclipsed on the rural frontier by the vitality, flexibility, and relevancy of the Baptists and more especially the Wesleyan Methodists.

To the Baptists, religion was not a formal profession or a hierarchical institution but rather a passionate expression of one’s faith in Christ. The unlicensed and relatively uneducated Baptist farm preachers were very effective revivalists, particularly in the South, and appealed most to the common people, the illiterate and the unschooled. Samuel Harris and James Ireland were just two of many well-known contemporary Baptist preachers.[48]

Methodism, transplanted from Great Britain in about 1765, was particularly suited to the American frontier, both doctrinally and structurally. Emphatically individualistic, Methodism taught a modified form of Arminianism by stressing that salvation, though originating in Christ, was in part conditional, depending on one’s behavior. Those who had come to rely on their own hard work to forge a living on the frontier resonated with a doctrine that put stock in individual effort and obedience.

Furthermore, the structures of Methodism were successful and appealing. While well organized and controlled, with a top-down chain of ecclesiastical command and authority, Methodism’s army of relatively uneducated circuit riders or itinerant traveling evangelical ministers made the critical difference. They went almost anywhere at any time and, in doing so, created an atmosphere of intensity and religious zeal that largely accounts for Methodism’s spectacular growth from a mere 15,000 in 1785 to 850,000 by 1840.[49]

Sometimes called “sons of thunder,” these itinerant preachers underwent two years of training and then stayed out on the hustings for one or two years at a time. Lorenzo Dow was one of the better-known Methodist circuit riders. Dressed in a broad-brimmed hat, a round-breasted frock coat, and breeches, many with hair to their shoulders, these “saddlebag preachers” often slept on the hard floor of a pioneer’s cabin or out under the stars, “a saddle for their pillow and the sky their coverlet.”[50]

Following a highly demanding lifestyle, by day they forded rivers and streams on horseback; rode through storms in capes and with umbrellas; braved blistering summer heat, Native American conflicts, and endless mosquitoes; and still persevered. The key to their success was that they brought their Methodist religion and their well-worn Bibles and Methodist hymnals and the works and music of John and Charles Wesley to the doorsteps of frontier America. As in England (see chapter 8), Methodism delighted in coming to the people, not the other way around. Excellent record keepers who preached with such earnestness that even devils may have stopped to listen, these “brush preachers” were indefatigable missionaries of the frontier’s “personal religion.”[51]

And they almost always found a ready audience. To the backwoods frontiersman, fear of death by Native American attacks, lawlessness, and even starvation was all too real. The “possibility of sudden death,” as historian Charles A. Johnson has noted, “made the question of one’s eternal destiny a matter of great concern.”[52] The frontier was no place for mild homilies; rather, it demanded rigorous, forceful preaching, often with great bodily gestures. Immorality, intemperance, tobacco, gambling, card playing, Sabbath breaking—all came under condemnation. Standing in awful earnestness at a flickering fireplace and preaching in solemn tones to a farmer and his family sitting on the floor and leaning against the cabin wall, the Methodist itinerant preacher had found his most intimate stage and most effective pulpit. It was one such Methodist preacher that had visited Joseph Smith’s mother, Lucy Mack Smith, during her sickness in 1802.

Methodism succeeded for another reason: its belief in what Methodist scholar John H. Wigger calls “the efficacy of prophetic dreams, visions, and supernatural impressions,” not unlike those experienced by Joseph Smith Jr. Referencing the conversion accounts of Thomas Rankin and Freeborn and Catherine Livingston Garrettson, Wigger has shown that the “quest for the supernatural in everyday life” was “the key theological characteristic of early American Methodism.” Adherents put great stock in “signs, wonders, and ecstatic experiences.” Wigger makes a strong point when he writes, “Early Methodism without such spiritual enthusiasm would be like Hamlet, not without the prince, but without the Ghost.”[53]

Surprisingly, it was not only the Methodists who fanned the flames of the Second Great Awakening; it was also the Presbyterians who, under the Reverend James McGready of Pennsylvania, introduced the camp meeting concept of public religious expression. Having moved to Kentucky in 1798, McGready employed a powerful, if unpolished, preaching style that attracted so many followers that no single edifice could begin to hold them all. In the ensuing Western (or Kentucky) Great Revival, which almost amounted to “godly hysteria,” McGready and his fellow preachers conceived the idea of a religious service of several days’ length held outdoors and for vast numbers of followers who were obliged to eat and find shelter far from home.[54] Best remembered was his monster meeting at Cane Ridge in 1801 where some twenty thousand people congregated for days on end to listen to one sermon after another. With preachers standing, shouting, and exhorting from wagons or tree stumps, something was bound to happen. People spontaneously began shrieking and groaning and singing amens and hallelujahs with thunder, lightning, and horses’ whinnying all thrown in for good measure. Soon such a grand cacophony of bustle and noise erupted that some described it as a “sound like the roar of Niagara.”

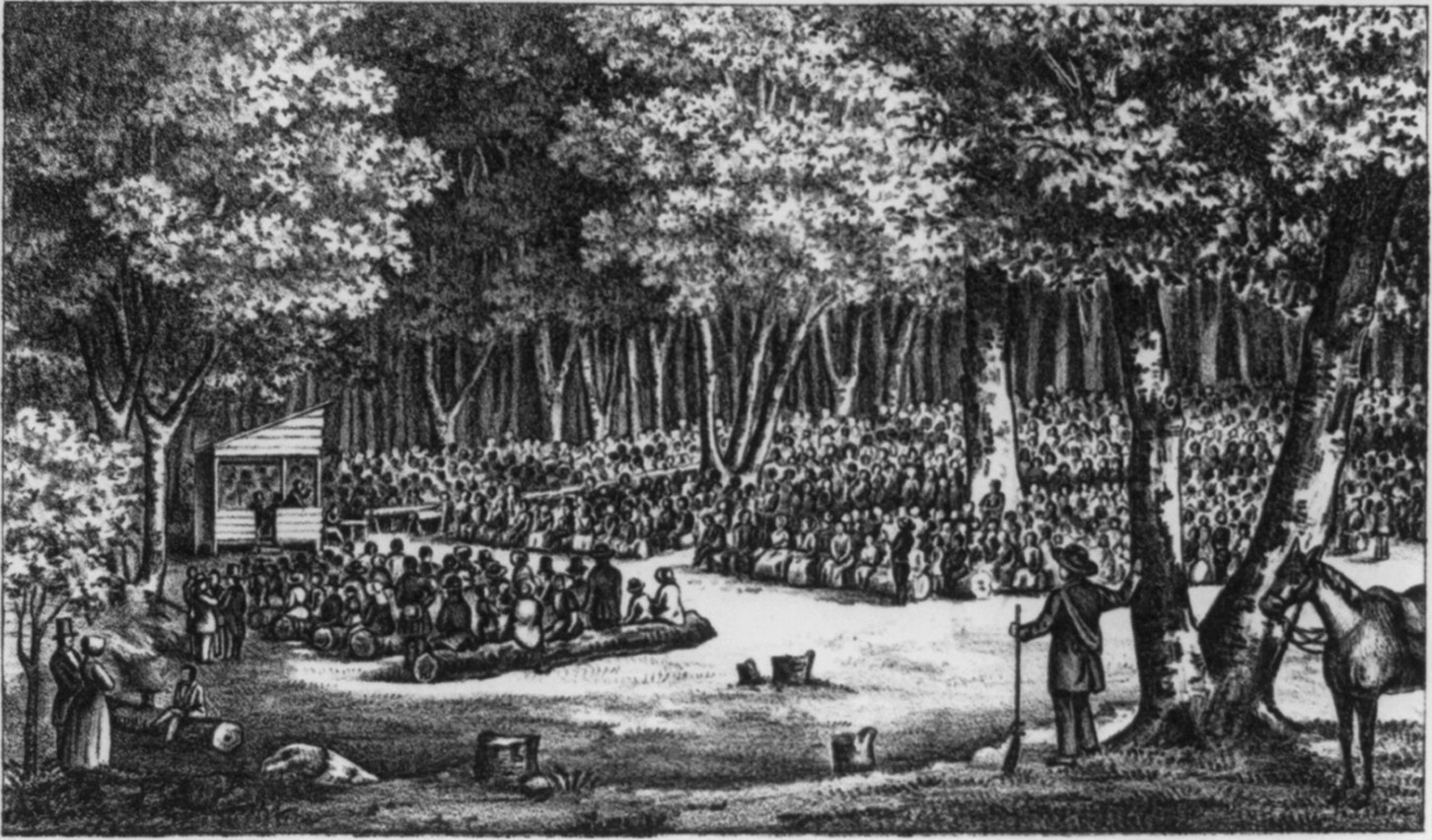

Sacramental Scene in a Western Forest, by unknown artist.

Sacramental Scene in a Western Forest, by unknown artist.

The camp meeting movement soon spread like wildfire. Reported one eyewitness:

The woods and paths seemed alive with people, and the number reported as attending is almost incredible. The laborer quitted his task; age snatched his crutch; youth forgot his pastime; the plow was left in the furrow; the deer enjoyed a respite upon the mountains; business of all kinds was suspended; dwelling houses were deserted; whole neighborhoods were emptied; bold hunters and sober matrons, young women and maidens, and little children, flocked to the common center of attraction; every difficulty was surmounted, every risk ventured, to be present at the camp meeting.[55]

This unbridled spirit of camp meeting enthusiasm quickly rolled out over Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia, and eventually north to Pennsylvania, Ohio, New England, and New York, though not without some resistance. McCready and other “New Lights,” as they were called, or revivalists who put stock in experiential, “felt” religion, offended many “Old Light” Presbyterians, who favored a more subdued and traditional form of sacred worship, preachers like the Reverend Barton Stone and Richard McNemar. Rigid Calvinism, as Bernard Weisberger has argued, could not “coexist with revivalism.”[56] Such contrasting points of view caused deep schisms within the Presbyterian clergy.

If Presbyterianism had trouble constraining the passions of the revival, “Methodism was made for it.”[57] By 1805, Joseph Smith Jr.’s birth year, the Methodists had taken over most camp meetings and, in their penchant for organization, gave them new structure, a more defined purpose, and much more careful planning and preparation. By so doing, the Methodist camp meeting regularly attracted crowds commonly in excess of twenty thousand people, often for days at a time.[58]

The central physical feature of the Methodist camp meetings was the wooden pulpit, often placed under roofed platforms and set up at one or both ends of an outdoor amphitheater, facing parallel rows of circular or horizontal hewn-log seating. The “mourning bench” or “anxious seat” was conspicuously placed in front of the pulpit and was used for sinners seeking forgiveness. The aisles and rows were filled with straw to make kneeling prayer more comfortable. Beyond the benches were their many tents, wagons, carriages, and horses to which the crowds reverted at night or between meetings for meals, rest, and refreshment. Lighting came from flickering lamps, candles, tent fires, and torches attached to trees or set on six-foot-high wooden tripods throughout the camp, allowing for meetings to last far into the night. Women sat on the right and the men on the left, always with scriptures in hand. Depending on the size of the crowd, there could be several adjacent arenas or amphitheaters prepared with as many as twenty to thirty ministers, several preaching simultaneously.

Usually these camp meetings lasted four days, from Friday until Monday and from dawn to dusk. With the sound of a trumpet at an early hour, all were to have concluded their tent family prayers and breakfast before the first meeting of the day at 8:00 a.m. Then came the “main event” at 11:00 a.m., another “handshake ceremony” at 3:00 p.m., and finally the candlelight confessionals—often the most stirring of all—from 7:00 p.m. to whenever the Spirit dictated. Services began with prayer, much singing, and a stirring sermon one to two hours long. Sundays featured communion services with the sacramental tables covered in sheets. “Prayer circles” or “prayer rings” materialized, usually between meetings when laymen and preachers joined hands to form a “circle of brotherly love” and where sinners too shy to walk to the anxious seat could come for encouragement, support, and acceptance.

Everything about these outdoor assemblies was carefully designed to convict people of their sins, to turn their hearts to Christ, and to have them confess their sins and repent. Their songs and sermons were often unforgettable, usually full of fear, hellfire, and damnation but always with the promise of redemption. Shall we listen in?

The opening hymn might well have been “A Mighty Fortress,” “Fairest Lord Jesus,” “Come, Thou Fount of Every Blessing,” or the ever-popular “Come and Taste Along with Me” as found in well-worn copies of The Wesleyan Camp Meeting Hymn-Book:

When I hear the pleasing sound

Of weeping mourners just converted,

The dead’s alive, the lost is found.

The Lord has healed the broken-hearted.

When I join to sing his praise,

The heart, in holy raptures use;

I view Immanuel’s land afar,

I shout and wish my spirit there.

Glory, honor and salvation;

What I feel is past expression.[59]

As for the sermons, they were of the urgent, thunderous, introspective, and enthusiastic variety, given spontaneously and without notes, and often concentrated on a single passage of scripture. As one “soul-melting minister” followed after another, they earnestly called on everyone within the sound of their voice and within the scope of their fierce eye to repentance before it became everlastingly too late. “If therefore your mind is more intent on the possession of this world than on your soul’s welfare,” exhorted one minister in one such camp meeting west of Schenectady, New York in 1820,

If you are more anxious to make gain than to honor God with your substance; if your thought and desires are more conversant about the body than about the soul, you must be satisfied that you seek your portion in this world and are numbered with the wicked. . . .

If therefore you do not sincerely mourn for your sins, if you do not hate your sins, and desire above all things to be delivered from their burthen, you are ranked with those who must be cast out, who must perish because you are wicked. . . . If therefore you do not put your trust in the Lord Jesus Christ as your only hope, if you do not renounce all dependence on your own supposed goodness or your deeds of morality and trust entirely in the obedience and death of Christ as the only [means of] acceptance with God, if you do not receive him as your Lord and Savior and neglect to live devoted to his service, you are numbered with them who are . . . wicked and must be so accounted in the great day.[60]

Such sermonizing condemned not only the sinners but also the would-be saints who were content to think they had lived sufficiently righteously and had worked their way into the good graces of an all-forgiving God.

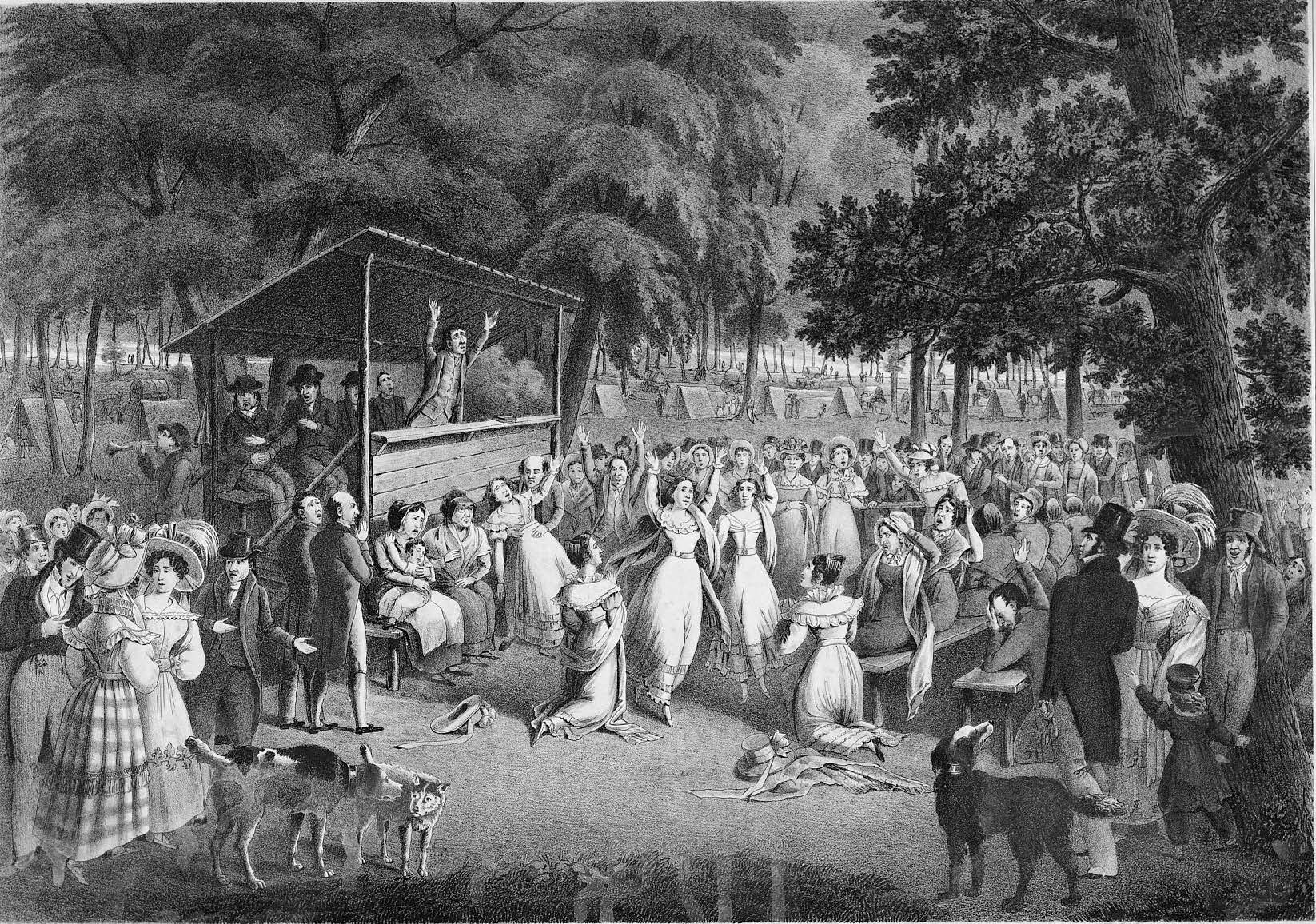

Camp-Meeting, by Harry T. Peters. Courtesy of National Museum of American History, "America on Stone" Lithography Collection.

Camp-Meeting, by Harry T. Peters. Courtesy of National Museum of American History, "America on Stone" Lithography Collection.

At the end of such rounds of preaching, with or without invitation, the assembled throngs would often stand and break out in singing another favorite, soul-stirring hymn, such as “Shout Old Satan’s Kingdom Down.”

This day my soul has caught new fire—Hallelujah!

I feel that heaven is coming nearer, O glory Hallelujah!

(Chorus)

Shout, shout, we’re gaining ground, Hallelujah!

We’ll shout old Satan’s kingdom down, Hallelujah!

When Christians pray, the devil runs, Hallelujah!

And leaves the field to Zion’s sons, O glory Hallelujah![61]

The effects wrought upon the vast assemblies by such powerful hymn singing and hand-wringing, soul-shaking sermons defy simple explanation. Many a convicted sinner could not wait to walk up to the mourner’s bench. As one Methodist leader, John McGee, said, “The people were differently exercised all over the ground, some exhorting, some crying for mercy, while others lay as dead men on the ground.”[62]

The different exercises McGee referred to included a large number of unexplainable, Pentecostal-like behaviors that affected hundreds of people both young and old, male and female, simultaneously or intermittently. Speaking in tongues (glossolalia) for hours at a time was common, as were other manifestations of the gifts of the Spirit. In the falling exercise, women and men shouted out praises to God and suddenly, as if on cue, fell to the ground lifeless, only to rise up hours later with stirring accounts of dreams and visions of the Almighty. With others, their necks and limbs began to twitch and jerk so violently that they fell down, doubled up, and rolled over and over in somersault fashion, rolling like a wheel. Others began to laugh uncontrollably or dance so vigorously that they whirled around fifty times a minute before collapsing in exhaustion, while still others, particularly women, began singing and chanting in melodious beautiful tones not from their mouths and throats, but, strangely, from deep within their breasts. Some laughed, most cried, and some even began to gather at the trunk of a nearby tree and bark in short guttural sounds while falling on all fours and “treeing the devil.” There are even accounts of a “running exercise” in which those who tried to run away, either for fear or disbelief, suddenly stopped and began to shout praises to their God before falling down and later awakening confirmed in the faith. Little children spoke and sang in tongues, while others, never known to speak with erudition, preached powerful sermons and often “so loud that they might be heard at a distance of a mile.”[63]

Such camp meetings were open to ministers of all denominations since the demand for preachers far exceeded the local Methodist supply. Usually they took on the personality of the leading preacher. Some were more subdued, some more unrestrained, some given to the great fear of the Lord, others to solemn gratitude and joy. While their messages more or less agreed one with another, not infrequently great debates and shouting matches broke out between the warring sides. Bitterly sectarian sermons were common, particularly at the eleven o’clock meetings, as many a preacher waxed loquacious and dogmatic on matters of creed. During one 1822 setting, the well-known reverend Peter Cartwright held his audience spellbound and long past their lunchtime with a three-hour diatribe against the Baptists. His remarks prompted a visiting Baptist minister to quit the field in disgust.[64] Other ministers often got into fierce debates and shouting matches one with another to such a degree that in such emotionally charged settings, many wondered who was right and who was wrong. When Joseph Smith Jr. referenced so great a scene of “confusion and strife among the different denominations,” he could not have been more accurate.[65]

This spirit of religious revivalism eventually spilled into western upstate New York and in such a sustained and pronounced fashion that historian Whitney Cross called it “the burned-over district.”[66] So many men of the cloth were vying for converts, so many revivals and torch-lit camp meetings were staged, that the area was burned over with religious excess. Said Joseph Smith, “There was in the place where we lived an unusual excitement on the subject of religion”[67]—an understatement, to say the least.

It would be an egregious error, however, to paint the burned-over district revivals with only the loud zealotry and emotional excesses of the camp meeting. Many new converts came to their own spiritual encounters in a much more subdued and reflective way. As noted previously, Joseph Smith’s mother, Lucy, converted to the Presbyterian faith. This may not be too surprising, considering her own previous covenant with God for sparing her life, her father Solomon Mack’s sudden conversion, and a sense that all their hard work had failed to get her and her indigent family any further ahead financially. Despite all this, Lucy Mack nurtured an abiding belief in God’s overarching purposes. However, there may well have been another reason for her Calvinist tendencies and the contrasting style of Presbyterian revivals in western New York state in 1819–20 as personified in the work of the Reverend Asahel Nettleton (1783–1844).

Born in 1783 in North Killingworth, Connecticut, to parents of the Half-Way Covenant, Nettleton had converted to Christianity at age eighteen in 1800 after spending many a night in prayer in nearby fields and forests. In 1805 he entered Yale College, where he came to know both Timothy Dwight and the writings of Jonathan Edwards well. Graduating in 1811 as an ordained Presbyterian minister, Nettleton declined a life of foreign missionary service in favor of pursuing Christian revivalism closer to home. Kind and courteous, conscientious and exemplary, unassuming and unostentatious, the Reverend Nettleton began his ministry in New Haven, where his congregants soon regarded him as their “spiritual father.”[68]

Asahel Nettleton, by Samuel

Asahel Nettleton, by Samuel

Lovett Waldo and William Jewett.

As the fire of the Second Great Awakening swept into upstate New York, Nettleton, now in increasing demand, accepted offers to conduct revivals in Schenectady, Nassau, Malta, Galway, and several other communities in the Finger Lakes region in early 1820. Wherever he went his style of preaching converted many, some say as many as thirty thousand.[69] When at the pulpit, “he was remarkably clear and forcible in his illustration of the sinner’s total depravity, and in his utter inability to procure salvation by unregenerate works, or any desperate efforts. . . . Absolute, unconditional submission to a sovereign God, was the first thing to be done.”[70] As to his quiet effectiveness, one of his disciples wrote: “This evening we met in the school house. The room was crowded, and the meeting was exceedingly joyful. Every word that was spoken, seemed to find a place in some heart. ‘Old things are passed away, and all things are become new.’”[71]

The key to Nettleton’s success was not only his plain, simple style of instructive preaching but also his fatherly care and concern for the individual. Shying away from large, camp meeting–style assemblies as those just described, Nettleton discouraged fanaticism, alcohol, confusion, and disorder of any kind, choosing the more intimate paths to individual conversion. Consequently, many felt free and easy with him, as if he were some long-tried friend. His idea of an “anxious meeting” was to pray and fast with others one-on-one, often walking home with both sinners and saved, listening and supporting. One man spoke reverently of their private conversations eighteen years after the fact. “I have found Him, I have found Him, and He is a precious Savior,” he confided to Nettleton. And in words similar to those describing the conversion of Solomon Mack, Lucy’s father, he further said: “That night I could not sleep for joy. I do not think I closed my eyes. I found myself singing several times in the night. In the morning all nature seemed in a new dress and vocal with the praises of a God all glorious. Everything seemed changed, and I could scarcely realize that one, only yesterday so wretched, was now so happy.”[72]

A confirmed bachelor throughout his life, Nettleton was a wise, caring evangelist who died in May 1844, just one month before Joseph Smith died. Whether Reverend Nettleton ever preached in or near the Smith home in Palmyra is not yet known, but his style of Presbyterian preaching, his house-to-house visits, and his caring concern paint a very different picture from that of the loud, Methodist-dominated camp meeting. The one was as still as the other was boisterous and may beg a revision to what some readers assume was the spirit of revivalism. Considering Lucy’s serious frame of mind and convictions, her conversion to Presbyterianism likely came through a Nettleton-like revival experience.[73]

Much of the spirit of Presbyterian evangelicalism in upstate New York in early 1820 began with Nettleton’s visit to Union College in Schenectady, where the sudden death of a young student in the third week of January sparked a revival of religion. In addition to Nettleton, professors like the Reverend E. Nott, president of the college, T. McAuley, Walter Monteith, Halsey A. Wood, and Elisha Yale began fanning out in all directions in what was a case of a college-inspired educated revival.

During 1820 in Saratoga, New York, Nettleton added fifty-five converts to the local church. In Malta, New York, the awakening spread over different parts of the town until almost all were affected. “Every house exhibited the solemnity and silence of a continued Sabbath; so profound was this stillness and solemnity, that a recent death could have added nothing to it in many families.” And in Stillwater, New York, “in a large district, though harassed by sectarian contention, there is now scarcely one house where daily prayer is not want to be made. . . . Boatmen, tipplers, infidels and atheists, were mixed with the unholy multitude, . . . [and all] felt the power of the Holy Ghost, and yielded to his influence.” By the end of March, more than twelve hundred people had converted in Stillwater alone.[74]

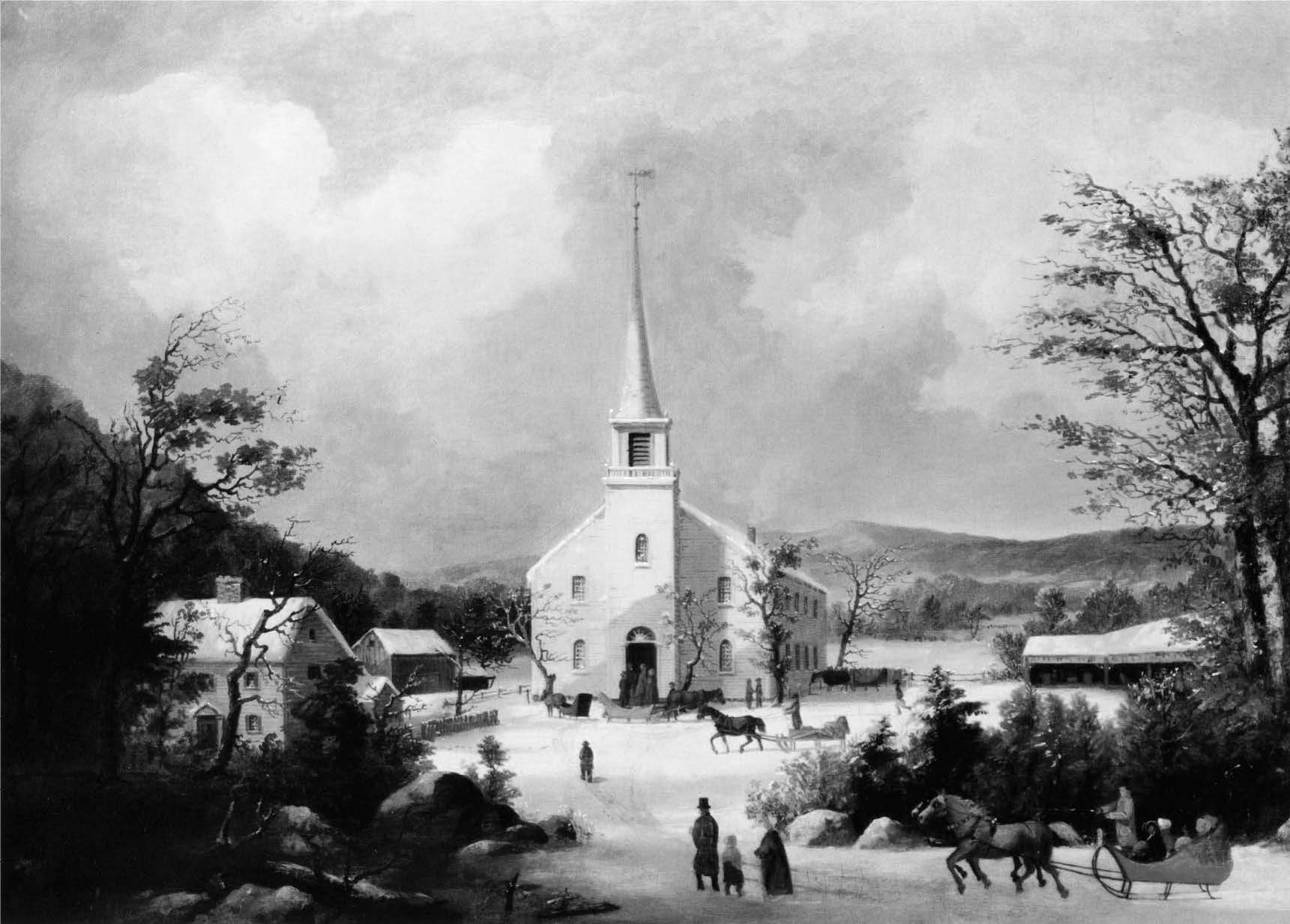

Going to Church, by George Henry Durrie.

Going to Church, by George Henry Durrie.

Unlike outdoor camp meetings, these Presbyterian-led revivals occurred during the dead of winter, after the harvests and before the busy springtime planting season, as evidenced in this March 1820 report from Amsterdam, New York:

An awe! A stillness! An oppressive silence, which cannot be described. . . . It was the sinking of the wounded heart! . . . Many who visited these meetings from motives of curiosity, totally careless! Beholding the mighty power of God, were terrified at their own hard and impenitent hearts; convicted of sin; awakened to a sense of the misery of their state. . . .

Sometimes, sleigh loads of convinced sinners, after leaving the meeting, and riding half a mile, or a mile, homewards, would turn back again to the place of prayer, to hear still more about the salvation of Jesus! And they often did this too, through lanes and ways and snows, that would have been deemed by persons in any other state of mind, to have been impassible.[75]

Women were key to the success of revivals. Many, particularly widows, visited from house to house encouraging family and individual prayers, holding anxious meetings of whispering or conversing individually with God, reading scriptures, and in other intimate ways furthering the flame of the local revival by challenging individuals to change course. Women clearly were a numerical majority among Methodist and Presbyterian adherents and formed the backbone of these revivals.[76]

Another highly effective mode of visitation was to hold meetings of as many as possible of one sex where they would discuss their most perplexing concerns and the deep issue of personal conversion. These visits were sometimes made to male heads of families, sometimes to the female heads, sometimes to young men or young women, sometimes to Native Americans and people of color, “which gave an unembarrassed opportunity of suiting an address to the persons present.”[77]

And it was among the youth, young men, and young women where revivals of all kinds bore the greatest fruit. One Baptist minister writing in January 1820 in speaking of mass conversions in Cornish, New York, told of “a number of young children” from “thirteen down to seven years of age” singing hosannas to the Son of David.[78]

Another Baptist minister in Bristol, Rhode Island, reported:

There are as many as four or five crowded meetings at once, at almost every hour of the day, from an early hour in the morning, until late at night. And even at the corners of our streets, you will scarcely see two or three persons together, but the great concern of the salvation of the soul is the subject of their conversation. . . .

Were I to attempt to tell you the number of young converts, who in a judgment of charity, have been brought out of darkness into God’s marvelous light, it would be utterly impossible.[79]

It was not uncommon for ministers of all faiths to report from the field that “two thirds of [the] whole number of converts are under 20 years of age.”[80]

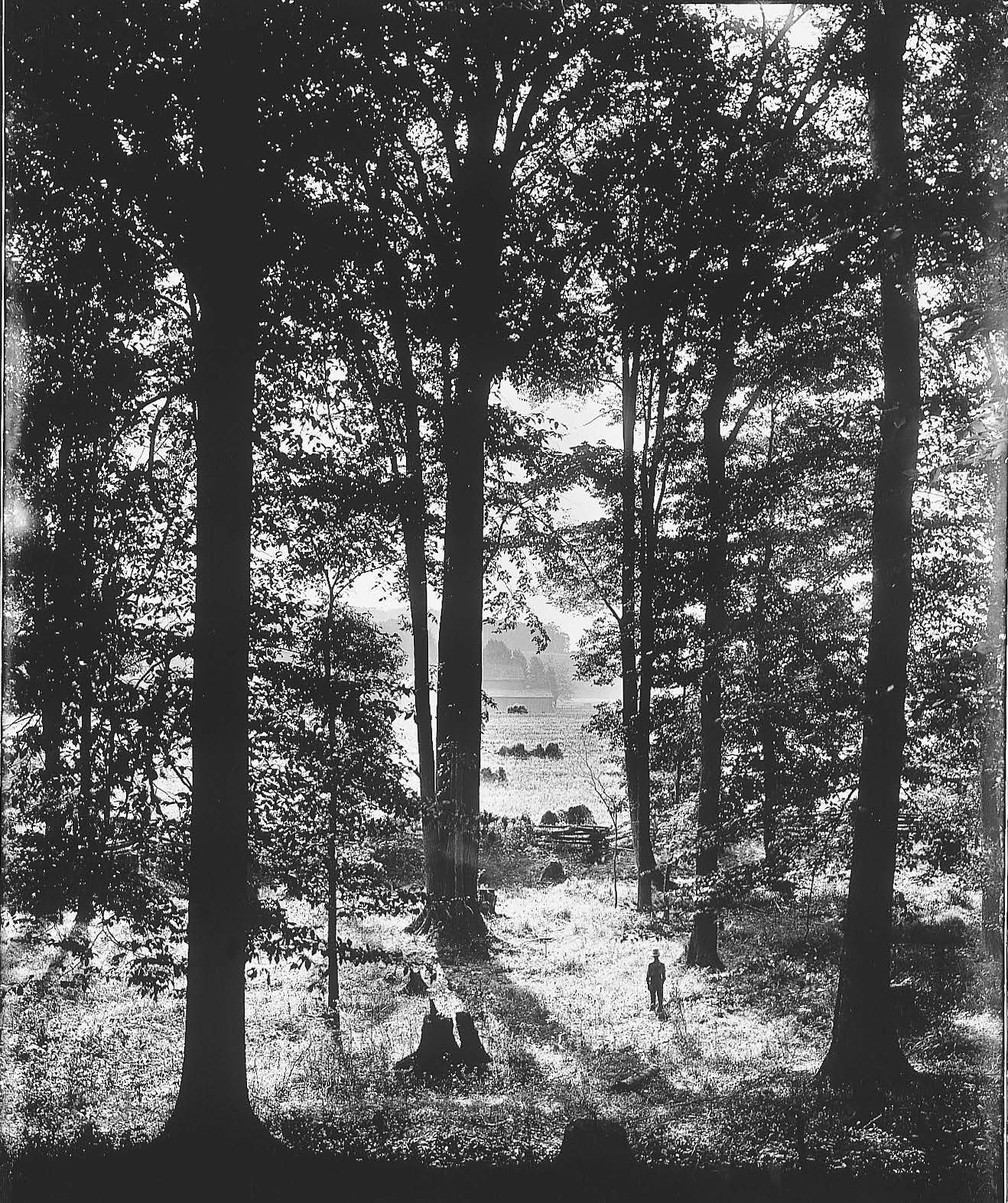

Often “a sound of a going” was heard, and entire schoolhouses emptied their anxious students, who scattered out into the nearby fields and quiet groves to pray to God above. In so doing, they usually took their Bibles with them and were encouraged to pray over a single verse or specific passage of scripture in their soliciting heaven for the salvation of their souls. Once in their quiet place of meditation, they would then stand and see the workings of heaven. “There you are at the place of meeting between the Spirit of God and your own spirit,” one minister reported in 1819. “You may have to wait, as if at the pool of Siloam; but the many calls of the Bible to wait upon God, to wait upon him with patience, to wait, and to be of good courage, all prove that this waiting is a frequent and a familiar part of that process by which a sinner finds his way out of darkness into the marvelous light of the gospel.”[81]

And such waiting on the Lord often bore remarkable fruit, as the following 1820 letter by a young lady to her minister friend attests:

From the age of 13 years I was blessed with the strivings of the Holy Spirit; but alas, I did not yield until your voice, by the Power of God, reached my heart. From that time I resolved to repent and forsake my most pleasing sins, if haply I might find that peaceful but unknown way. While in the sacred grove on the 14th of August 1818, my incessant cries reached the Father of mercies, and my benighted soul received the dawn of heaven. My confidence in God, through the atoning blood of the Dear Redeemer, has grown stronger and stronger.[82]

“I Became Convicted of My Sins”

If the outcome of Joseph Smith’s sacred grove experience resulted in his vision of God the Father and the Son and in the birth of a new American religion, the pathway to that theophany was very much in consonance with the religious strivings and experience of his time and place.

As he explained it in his original account:

At about the age of twelve years my mind became seriously impressed with regard to the all important concerns for the welfare of my immortal Soul which led me to searching the scriptures. . . . I became convicted of my sins and by searching the scriptures I found that mankind did not come unto the Lord, but that they had apostatized from the true and living faith and there was no society or denomination that built upon the Gospel of Jesus Christ as recorded in the New Testament and I felt to mourn for my own sins and for the sins of the world.[83]

Sacred Grove, photograph by George Edward Anderson. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Sacred Grove, photograph by George Edward Anderson. Courtesy of Church History Library.

It is beyond the scope of this study to look at the result of his erstwhile prayers and strivings. Many readers know full well of his succeeding visions and revelations, his ensuing translation and publication of the Book of Mormon in 1829–30; his organization of the “Church of Christ” in April 1830 and of its early growth in Ohio, Missouri, and in Illinois; and of Joseph Smith’s ultimate death in Carthage, Illinois, in 1844 at the hand of mobs and persecutors. These all derived from what happened in 1820. Rather, what this concluding chapter has endeavored to do is to show that Joseph Smith’s prayerful, deeply faithful yearnings did not emerge from a vacuum. There is no question that he was very much exercised over religion and his own salvation, and that he possessed extraordinary faith. What this chapter has tried to do is to place his religious quest within a long and fascinating American religious context, one that began with the Puritans and continued through one apostasy and one great awakening after another. Such earlier lights as John Winthrop and Jonathan Edwards, James McGready and Asahel Nettleton, Solomon and Lucy Mack, and Joseph Smith Sr. in their own time and place uniquely prepared the way for his First Vision experience.

Hence it was, he wrote, “in accordance with this, my determination to ask of God,” to seek forgiveness, and, like his mother and father, to know which church to join, that young Joseph Smith Jr. “retired to the woods to make the attempt. It was on the morning of a beautiful, clear day, early in the spring of eighteen hundred and twenty.”[84]

Notes

[1] Joseph Smith—History 1:5.

[2] Joseph Smith—History 1:7–8, 13.

[3] Shipps, Mormonism, x.

[4] Mack, Narrative of the Life of Solomon Mack, 23–24.

[5] Proctor and Proctor, Revised and Enhanced History, 48.

[6] History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, 47–50.

[7] Bushman, Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Mormonism, 26.

[8] The root of the ginseng, which grows wild in parts of Vermont, is prized in China as a panacea for cancer, rheumatism, diabetes, and other ailments. To this day, the lucrative ginseng trade is still active in parts of Vermont. History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, 57.

[9] History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, 81. Volcanic ash in the atmosphere, caused by the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia more than twelve thousand miles away, devastated what few crops remained in New England and drove thousands of dispirited New Englanders west to the Finger Lakes region of western New York, where farmers raised wheat in abundance.

[10] History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, 63.

[11] History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, 65–66.

[12] History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, 94.

[13] Brainerd and Brainerd, New England Society Orations, 1:30.

[14] Brainerd and Brainerd, New England Society Orations, 1:34, 45–46.

[15] For a helpful, if dated, primer on the Puritans, see Skelton, Story of New England.The less religious term Pilgrim was much later applied to these early settlers.

[16] Heimert and Delbanco, Puritans in America, 14.

[17] Ellis, “The Religious Element in the Settlement of New England,” in Winsor, English Explorations, 3:225–29.

[18] The “Council for New England” was incorporated in November 1620 for the original Plymouth Colony. It was a Crown-approved reincorporation of the earlier adventures of the “Northern Colony of Virginia,” under which authority Jamestown had been established in 1607. See Deane, “New England.”

[19] Adair, Founding Fathers, 14–15.

[20] Heimert and Delbanco, Puritans in America, 89–91.

[21] Heimert and Delbanco, Puritans in America, 91.

[22] Heimert and Delbanco, Puritans in America, 9.

[23] Heimert and Delbanco, Puritans in America, 77.

[24] Heimert and Delbanco, Puritans in America, 116.

[25] Heimert and Delbanco, Puritans in America, 120.

[26] Jacobus Arminius, a seventeenth-century Dutch theologian, had taught that God’s grace is conditional on the free-will obedience of man, that the works of faith and repentance are essential to salvation.

[27] Heimert and Delbanco, Puritans in America, 50.

[28] Miller, Errand into the Wilderness, 35–57.

[29] For the most complete biography of Edwards, see Marsden, Jonathan Edwards. For a comprehensive new study of Edwards’s complex theology, see McClymond and McDermott, Theology of Jonathan Edwards. The authors contend that Edwards, “the greatest religious thinker in the history of America” (23), believed in the beauty of God and his creation, in the charismatic gifts of the Spirit, and in salvation coming through a mixture of faith and love.

[30] Bushman, From Puritan to Yankee, 183.

[31] Sweet, Revivalism in America, 30; emphasis added.

[32] Sweet, Revivalism in America, xvii.

[33] Sweet, Revivalism in America, 85.

[34] Though an ordained priest in the Church of England, George Whitefield converted to a form of “personalized” Calvinism. Between 1738 and 1770, he made seven voyages to America, preaching from Georgia to Maine. Sometimes called “the flaming apostle,” he preached to far more American colonists than did anyone else. Ministers and congregations welcomed him everywhere as the crystalizing force that galvanized the “here and there awakenings into a continent-wide renewal.” Rutman, Great Awakening, 35. One would err, however, in concluding that the colonial Great Awakening owed its origins to the British Wesleyan Methodist movement, since that effort blossomed in Great Britain after the time of the Great Awakening. For more on Wakefield and the British Wesleyan Methodist Movement, see chapter 8.

[35] Bushman, From Puritan to Yankee, 185.

[36] Rutman, Great Awakening, 36.

[37] Bushman, From Puritan to Yankee, 187–95.

[38] Miller, Errand into the Wilderness, 162–63. Religious historian William Sweet observed, “They sowed the basic seeds of democracy more widely than any other single influence.” Sweet, Revivalism in America, 41. Richard Bushman likewise contends that the institutional church lost power and authority while individuals gained a new “investiture of authority” through experiencing the joy and liberty of personal spiritual experience and conversion. Bushman, From Puritan to Yankee, 220. Not all scholars today, however, accept Sweet and Bushman’s view that such religionists contributed to the rise of democracy and the fire of the American Revolution.

[39] Miller, Errand into the Wilderness, 162–64,

[40] Weisberger, They Gathered at the River, 54–60. Harvard College was founded by the Reverend John Harvard in 1639, and Yale University was founded in 1701, both religious schools.

[41] One revisionist branch of scholarship asserts that the term Great Awakening was an overstatement and oversimplification, that it was not nearly so great or widespread as many historians have long assumed. One of the first to make this argument was Jon Butler, “Enthusiasm Described and Decried: The Great Awakening as Interpretive Fiction,” 305–25. More recently, Frank Lambert claims it was at best “a creation of a particular group of evangelicals,” that it was far more localized and scattered in scope and that its religious publicists generated a false image of a widespread, interconnected religious movement. Lambert goes so far to call the Great Awakening “an invention,” an overstatement and oversimplification, and not a widespread movement. It was all just an “ordinary occurrence,” more local than general. See Lambert, Inventing the “Great Awakening,” 6–8, 11, and 255. From my own limited research on the topic, however, I have found compelling evidence that the Great Awakening was both a widespread and a very intense religious movement.

[42] Weisberger, They Gathered at the River, 7.

[43] Weisberger, They Gathered at the River, 15.

[44] Bushman, From Puritan to Yankee, 267–71.

[45] Cleveland, Great Revival in the West, 1797–1805, 30.

[46] Weisberger, They Gathered at the River, 11.

[47] Scott, Evangelicalism, Revivalism, and the Second Great Awakening.

[48] Sweet, Revivalism in America, 93–95.

[49] Weisberger, They Gathered at the River, 46.

[50] Johnson, Frontier Camp Meeting, 156.

[51] Johnson, Frontier Camp Meeting, 158–67. From one circuit rider came this representative report of February 1820: “I shall here state for the benefit of the society, that I have visited and preached in seventy towns, travelled three thousand six hundred and seventy miles, (in about eight months) and preached two hundred and forty sermons.” Joseph A. Merrill, from a letter dated 15 February 1820, in The Methodist Magazine, April 1820.

[52] Johnson, Frontier Camp Meeting, 170–71.

[53] Wigger, “Taking Heaven by Storm,” 167–94; see especially 170, 173, 191.

[54] Weisberger, They Gathered at the River, 21–28.

[55] Davidson, History of the Presbyterian Church in the State of Kentucky, 136–37, as cited in Sweet, Revivalism in America, 123.

[56] Weisberger, They Gathered at the River, 83.

[57] Weisberger, They Gathered at the River, 42.

[58] See Jones, “The Power and Form of Godliness,” 88–114. See also Fleming, “John Wesley,” 131–49.

[59] The Wesleyan Camp Meeting Hymn-Book, as cited in Johnson, Frontier Camp Meeting, 135. I am indebted to Charles Johnson for his excellent study of everything pertaining to the order, structure, and sentiment of the camp meetings.

[60] From an unpublished sermon titled “Woe unto the Wicked,” by the Reverend Andrew Yates (1772–1844) and delivered 21 March 1813 and in l820 at or near Schenectady, New York.

[61] From Mead, Hymns and Spiritual Songs. See also Scott, New and Improved Camp Meeting Hymnbook, as cited by Sweet, Revivalism in America, 144.

[62] Words of John McGee, 1800, as cited in Johnson, Frontier Camp Meeting, 57.

[63] Letter by Rev. Thomas Moore, Ten Mile, Pennsylvania, 9 March 1803, in the Massachusetts Missionary Magazine, 198–99, as cited in Cleveland, Great Revival in the West, 95–96.

[64] Johnson, Frontier Camp Meeting, 126.

[65] Joseph Smith—History, 1:8. One minister, in speaking of sectarian strife in 1819, reported as follows: “The Rev. Simeon Snow was employed 26 weeks, chiefly in the [New York] counties of Oneida, Otsego, and Delaware. The people in those parts were much divided by sectarian prejudices. . . . At Lewiston, [Niagara County] . . . the Rev. David M. Smith has a pastoral charge. . . . When the small number of praying people have been cheered with the prospects and hopes of a revival, a sectarian spirit, under the impulse of ignorance and a passionate zeal for proselyting, has grievously disappointed their pleasing expectations.” In Genesee County in particular, “sectarian bigotry divided the people.” 21st Annual Narrative of Missions Directed by the Trustees of the Missionary Society of Connecticut in 1819, 4.

[66] Cross, Burned-Over District.

[67] Joseph Smith—History, 1:5.

[68] Tyler, Memoirs, 91.

[69] Cheek, “Revivalism: A Study of Asahel Nettleton.”

[70] Tyler, Memoirs, 156.

[71] Tyler, Memoirs, 106.

[72] Tyler, Memoirs, 172.

[73] William Smith, a younger brother to Joseph Smith, remembered that it was his mother, Lucy Mack Smith, who “prevailed on us to attend the meetings, and almost the whole family became interested in the matter, and seekers after truth.” She continued her importunities and exertions to interest us in the importance of seeking for the salvation of our immortal souls, until almost all the family became either converted or seriously inclined.” Smith, William Smith on Mormonism, 6–7. I am indebted to Kyle R. Walker for bringing this remembrance to my attention. For more on revivalism near the Smith Palmyra home, see Backman, Joseph Smith’s First Vision. For a more current study, Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision.

[74] Narrative of the Revival of Religion, 6–10, 22.

[75] Narrative of the Revival of Religion, 17.

[76] Wigger, Taking Heaven by Storm, 184.

[77] Narrative of the Revival of Religion, 23.

[78] Letter from Ariel Kendrick to the editors, January 1820, in American Baptist Magazine 2, no. 8 (March 1820): 297.

[79] Letter from L. W. B., 7 April 1820, to Rev. Dr. Baldwin, in American Baptist Magazine 2, no. 9 (May 1820): 343. For a fine treatment of the role of youth in the Second Great Awakening, see Wright, “‘Your Sons and Your Daughters Shall Prophesy . . . Your Young Men Shall See Visions,’” 147–50. Wright demonstrates both qualitatively and quantitatively that youth were more than passive onlookers in these religious revivals but were very active participants.

[80] Letter from R. Maddocks to the editors, in American Baptist Magazine 2, no. 11 (September 1820): 407.

[81] Chalmers, Sermons Preached in the Iron Church, Glasgow, 68.

[82] Letter of Miss Eliza Higgins, 30 October 1820, Methodist Magazine (August 1822): 291. For much more on the important role women played in the conversion process during this time, see Cope, “‘In Some Places a Few Drops.’”

[83] 1832 Recital of the First Vision, in Backman, Joseph Smith’s First Vision, 156.

[84] Joseph Smith—History 1:14.