Pandora's Box

King George IV, Queen Caroline, and the Industrial Revolution

Richard E. Bennett, “Pandora's Box: King George IV, Queen Caroline, and the Industrial Revolution,” in 1820: Dawning of the Restoration (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 153‒80.

The central feature of this chapter is to assess the wrenching impact the Industrial Revolution made on British society in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. While some insist that it eventually resulted in an age of improvement, such growing pains came with a steep price. These profound changes shook English society to its very core, scarring an agrarian landscape, disrupting patterns of family living, replacing men with machines, and improving the lives of some while impoverishing those of many others. Like a pot of water about to boil over, the heat was turned up on an England now bubbling and steaming over for radical change. Such changes, while falling short of causing an English-styled French Revolution, were revolutionary in and of themselves and led to much-needed reforms that ultimately changed a nation and eventually transformed the world.[1] However, this study will begin—and end with what some might consider window dressing, an interesting royal sideshow between two selfish, self-centered personalities whose inconsiderate actions toward one another riveted the attention of the nation, sparked the beginnings of popular journalism, and ironically contributed to many necessary reforms and genuine improvements in society. And certain it was that the Industrial Revelution would affect the Restoration and the rise of the Church of Jesus Christ in ways not yet fully appreciated.

Coronation Portrait of George IV, by Thomas Lawrence.

Coronation Portrait of George IV, by Thomas Lawrence.

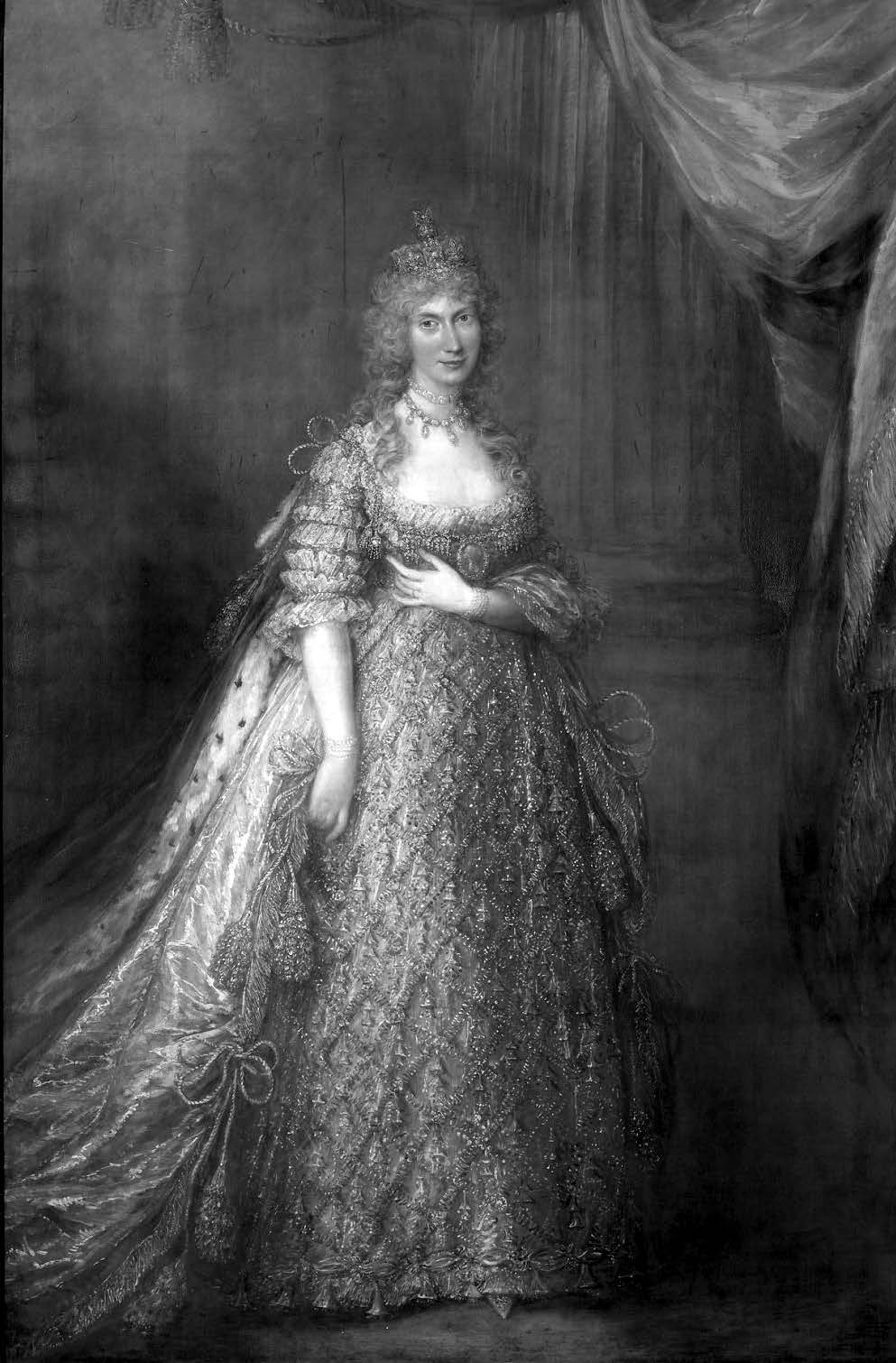

Caroline of Brunswick (1768–1821) When Princess of Wales, by Gainsborough Dupont.

Caroline of Brunswick (1768–1821) When Princess of Wales, by Gainsborough Dupont.

Pandora’s Box

Early in the spring of 1820, King George IV received the jarring news from his royal couriers that his estranged wife, Caroline, had defied his decree and left Rome for London. After a six-year, self-imposed absence abroad, she had determined to return to take her rightful place as England’s queen at her husband’s impending coronation ceremony, whether or not it ruined the monarchy or ruptured the nation. “My mind is in a state that is not to be described,” the king admitted in a mood of profound melancholy and disbelief. Confided his foreign secretary, Lord Castlereagh, “If she is mad enough or so ill-advised as to put her foot upon English ground, I shall from that moment, regard Pandora’s box as opened.”[2]

When Caroline reached the outskirts of London on 6 June 1820, rays of sunlight broke through the cloudy skies, and her carriage top was thrown open so that the princess could be clearly seen dressed in a black gown with a fur ruff and a black satin hat adorned at the front with a few high, luxuriant feathers. “It was a look,” wrote one of her biographers, “that during the coming months, she was to make her own.”[3] All of London seemingly turned jubilant at the news of her pending arrival.

Come nightfall, however, the mood turned sinister. For three consecutive nights, mobs with torches in hand roamed the streets, knocking on doors, demanding that residents illuminate their houses “for the queen,” and smashing windows of every government cabinet minister and known King George supporter. The Austrian countess Dorothea Von Lieven (1785–1857) described the city in a letter to Metternich: “What a stir, what excitement, what noise! The mob streamed through the streets all night making passers-by shout ‘Long live the Queen.”[4] Several soldiers mutinied, and it seemed the furious crowds were “careering towards rebellion.” The cry of “No Queen, no King” was heard on every corner. Arthur Wellesley (1769–1852), the Duke of Wellington, expressed his “greatest anxiety” respecting the state of the military in London, and Lady Frances Jerningham (1747–1825) believed that England “[was] nearer disaster than it [had] been since the days of Charles 1st.”[5] Lord Charles Grey (1764–1845), the Whig leader in the House of Lords, feared “a Jacobin Revolution more bloody than that of France.”[6] Never had England so revered a blemished royal, and never had it so despised its king.

The immediate cause of Caroline’s return was the king’s insistence that they divorce, that she be degraded from her royal rank, and that her name be expunged from the Anglican Church Litany and no longer prayed for. Having indignantly refused an annual pension of £50,000 on condition of her not using the title of queen of England or any other royal title, she had courageously decided to return, knowing full well Parliament would immediately put her on trial for adultery, if not high treason, which, if proved, would be sufficient grounds for the king’s desired divorce. Her plan was, however, to put the king on trial in the court of public opinion, for if she were far from perfect, King George was far more so, with more mistresses on call than government ministers at bay. She would play the role of the victim for all it was worth and win over the hearts of women and men everywhere until her husband would be forced to relent, bow the knee, and accept her back as the rightful princess of Wales, queen consort of England.

A Medley for the Most Opposite Qualities: The Prince of Wales

Born in 1762 as the oldest of the fifteen children of King George III and Queen Charlotte, George Augustus Frederick, first Prince of Wales and Duke of Cornwall, was indeed in a royal predicament, although one not all of his own making. He has received more than his share of criticism. Upon his death in 1830, The Times thundered out this verdict: “There never was an individual less regretted by his fellow creatures, . . . an inveterate voluptuary, . . . of all known beings the most selfish.” Charles Grenville (1794–1865), clerk to the privy council and famous diarist, wrote of him: “A more contemptible, cowardly, selfish, unfeeling dog does not exist. . . . There have been good and wise kings but not many of them, . . . and this I believe to be one of the worst.” Even Lord Wellington, who served him as prime minister from 1828 to 1830, could muster only muffled praise: “The most extraordinary compound of talent, wit, buffoonery, obstinacy, and good feeling—in short a medley of the most opposite qualities with a great preponderance of good—that I ever saw in any character in my life.”[7]

When George IV, or “Prinny” as he was called for being the Prince of Wales, was fifteen years old, his tutor said, “He will be either the most polished gentleman or the most accomplished blackguard in Europe—possibly both.”[8] Although at heart a good and decent man, by his early teens he had already rebelled against the strictness of his father and the overbearing nature of his mother. King George III reigned over England for sixty years, presiding over the disastrous American Revolutionary War (1776–83) as well as the triumphant victory over Napoléon. A deeply religious, very moral man, “Farmer George,” as King George III was sometimes called because of his love for agriculture and the simple things of life, firmly believed his mission was to spread the Protestant faith and to save the rapidly expanding British Empire from moral collapse. But he could not do so without his sons. King George III often punished his oldest son, fearing that he lacked the inner discipline, industry, good manners, and integrity he so ardently wished for in his successor. This drove the prince closer to his more tolerant mother. King George III always favored his second son, Frederick, Duke of York, and Prince George knew and resented it. Whatever the cause for his flagrant misbehaviors, the volatile prince of Wales rebelled against his father and turned to bad company, drink, and an extravagant lifestyle. A quick learner who loved music, the fine arts, and architecture and a student of several languages, his accomplishments were more “elegant than necessary.”[9] He was a handsome, overweight young man whose love for all things equestrian was eclipsed only by his love for wine, women, and waging bets. At age sixteen, he fell in love—or at least in lust—with Mary Hamilton, one of his sister’s governesses, who, seven years his senior, set the pattern of loving older women. He next fell in love with actress Betty Robinson and at age eighteen fathered a child with a married woman.[10]

King George IV, by Thomas Lawrence.

King George IV, by Thomas Lawrence.

E. A. Smith, one of King George IV’s finest biographers, noted that it was “a licentious age, when young and adolescent sprigs of nobility sowed wild oats with reckless abandon.” Drunkenness was “the vice of the age,” and during the middle to later years of the eighteenth century, “attitudes towards sex in England, especially in London, were unusually relaxed.” But Prince George, “a man of a thousand loves,” was more “relaxed” and easily persuaded than most others.[11] Among the aristocracy, women were frequently as free as men in their social flings and illicit sexual behavior. “Pleasure was king, and for a time George was its prince.”[12]

At age twenty-one, the prince moved out of the royal palace and took up residence at Carlton House on Pall Mall, where he pursued his lifelong habits of constantly remodeling his living quarters, hosting wildly expensive balls, and entertaining lavishly, all at a cost he could ill afford. The future king never understood the value of a pound, shilling, or crown and racked up debts that only Parliament and his father could pay off.

Then in 1785, at age twenty-three, he found the one true love of his life. Maria Fitzherbert (1756–1837), already twice widowed, was his senior by six years and was as virtuous as he was promiscuous, a noble and highly religious woman of rosebud complexion. The prince tried everything—feigning even suicide—to win over her affections. Finally, after reading her own emotions, she agreed to secretly marry him. But there was one fundamental problem: Maria was a Roman Catholic, while he was committed as the future leader of the Church of England to uphold Protestantism at all costs throughout the realm. Given five hundred pounds for agreeing to perform the ceremony, a Catholic priest married the couple in Maria’s drawing room on Parte Street in December of that year. Although they lived apart and in secret, the star-crossed lovers lived happily as husband and wife. Eventually, however, Maria, unwilling to be seen as another mistress, moved away and loved him from afar.

The sad fact is that “he never found anyone whom he loved as he had loved her.”[13] Incapable of giving the same devotion she conferred on him, Prince George had affairs with Lady Jersey (1753–1821), Lady Hertford (1759–1834), and Lady Conyngham (1769–1861), to name but three of many—some married, some not. When King George III finally learned of Prince George’s marriage to Maria, he invoked the Royal Marriage Act, revoking his son’s clandestine union and declaring it null and void and without effect because no royal consent had been given. If he persisted in his marriage to Maria, he would be forced to forfeit the crown, something the prince was not disposed to do. But all of England knew who his real love was.

Torn between the woman he loved and the crown he craved, what was he to do? Some maintain that Lady Jersey had concocted a plan for him to marry a German princess while she, Lady Jersey, stayed on the royal payroll as chambermaid and mistress. More likely it was his father’s decision for an arranged marriage that saw his son marry—sight unseen—his first cousin, a German Protestant, Princess Caroline Amelia Elizabeth (1768–1821), daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Brunswick. In exchange for the arranged marriage, Parliament paid off the prince’s debt of 375,000 pounds.

And They Lived Happily Never After

Caroline Amelia Elizabeth of Brunswick, by James Lonsdale.

Caroline Amelia Elizabeth of Brunswick, by James Lonsdale.

James Harris, 1st Earl of Malmesbury (1746–1820) and a highly regarded British diplomat, was sent to prime and prepare the princess and escort her back to England for the wedding. He sensed from the start that the proposed marriage would prove disastrous. Caroline, he soon discovered, was a loud, uncouth, scatter-brained chatterbox who lacked discrimination, tact, sound judgment, and common sense. She was “a creature of impulse” and was “carried away by appearances and enthusiasms.”[14] She spoke English poorly and cared little about education and learning the great matters of the day. And although she had her physical charms, she had little sense of fashion and cared even less about personal hygiene. One would have to get over the initial sense of repulsion before beginning to enjoy her company. In short, Caroline was “one of the most unattractive and almost repulsive women for an elegant-minded man that could have been found amongst German royalty.”[15] Although a mismatch of minds and hearts, brought together by circumstances not of their choosing, the two were equally selfish, self-centered, undisciplined, and rebellious.

At the first meeting of Caroline and the prince, he is reported to have turned and said to an apprehensive Lord Malmesbury, “I am not well; pray get me a glass of brandy.” It was contempt at first sight. Never was a prince dragged more reluctantly to a wedding than Prince George was that fateful 8 April 1795. Even the archbishop of Canterbury who officiated at the ceremony laid down his book and looked earnestly at the groom, who was as forlorn and disconsolate as the bride was giddy and full of high spirits, smiling and nodding to everyone. Others were mortified. On hearing news of the marriage, Maria Fitzherbert fainted. The queen mother, Charlotte, who abhorred Caroline from the start, vowed never to talk to her new daughter-in-law and resolved to hate her till her dying day. Even King George III now recognized the impossibility of a lasting union but urged them to live at least for a time under the same roof. Prince George spent his wedding night drunk on the floor. Their honeymoon, with his mistress Lady Jersey “in constant malicious attendance,” was an awkward catastrophe, and the prince and bride never lived as man and wife for more than a few days.[16] Put simply, they lived happily never after.

The Wedding of George, Prince of Wales, and Princess Caroline of Brunswick Officiated on 8 April 1795 in the Chapel Royal of St. James's Palace, London, by Gainsborough Dupont. The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo.

The Wedding of George, Prince of Wales, and Princess Caroline of Brunswick Officiated on 8 April 1795 in the Chapel Royal of St. James's Palace, London, by Gainsborough Dupont. The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo.

The marriage, however, did solve some immediate problems. As promised, Parliament paid off the prince’s debts and increased his annual income to 125,000 pounds, hardly enough to support his lavish style of living. In early 1796, nine months after the wedding, Caroline gave birth to their only child, a daughter, whom they named Charlotte Augusta. Recognizing the futility of their marriage, Prince George wrote Caroline a famous letter, essentially dictating their own standards of morality by attempting to absolve each of fidelity, with neither “to be left answerable to the other.”[17]

Meanwhile, the prince begged Maria to return to his side, beseeching her, in his words, to “save me . . . from myself,” and Caroline, pursuing old habits of her own, moved to Blackheath, where she found comfort with other men. The scorned princess decided to get even with her unfaithful husband by dressing provocatively and acting eccentrically. “What a pity she has not a grain of common sense, not an ounce of ballast to prevent high spirits, and a coarse mind without any degree of moral taste,” said one woman at court. Another stated: “She was a nasty, vulgar, impudent woman that was not worth telling a lie about.”[18]

Their daughter, Charlotte, was as high-spirited and independently minded as her parents. She proved to be an unhappy scapegoat of contention between two quarreling parents. Fearful that she would follow after her mother, Prince George treated her sternly and did all he could to keep mother and daughter apart. He chose one governess after another to look after the young girl, intercepted correspondence between Caroline and Charlotte, and limited their visits to only twice a week. Charlotte came to distrust both of her parents and detested their constant selfish bickering and machinations. Anxious to set out on her own, she married at age nineteen in 1815, but to everyone’s utter dismay she died two years later while giving birth to a stillborn son, throwing all of England into deep mourning over the deaths of both of Prince George’s lawful successors. Caroline, then away on the continent, was not even told of the tragedy until sometime afterward. More than any other factor, Charlotte’s untimely death spurred the prince toward getting a divorce.

Meanwhile, Prince George’s path to the throne was a much delayed and twisted one. Not only did his father live for a very long time, but in 1788 King George III suffered his first bout of madness. If not caused by a form of manic depression (to which his own arguably failed marriage may have contributed), it stemmed more likely from acute intermittent porphyria, a physical disorder that may have also affected his son and even Caroline, his niece and daughter-in-law.[19] Although he recovered, King George III’s unhappy malady reoccurred in 1804 and then again permanently in 1810. For the last ten years of his life, he wandered the halls of Windsor castle in insanity, a blind old man with a long white beard and a violet dressing gown. Only the “Star of the Order of the Garter” pinned to his chest was a reminder “that this wreck of a man was King of England.”[20] Prince George was subsequently appointed regent—acting king—with unrestricted royal prerogatives in 1811 and served as such until his father’s death on 29 January 1820.

Distanced from her own daughter and barred from celebration and other royal festivities at St. James’s Palace, Charing Cross, and Temple Ben, Princess Caroline gained increasing sympathy in the public eye for what seemed to be unnecessary persecution of a woman deprived of her place and of her daughter. Shrewdly guided by Lord Minto (1751–1814), Sir Matthew Wood (Lord Mayor of London, 1768–1843), and especially Sir Henry Peter Brougham (a Whig leader in Parliament and a highly regarded barrister, 1778–1868), Caroline fought back, firing Lady Jersey and many other unfriendly ladies at court. Why she then foolishly decided to leave her daughter and go abroad on an open-ended tour of Europe just when her popularity rising is still not entirely clear. Perhaps it was a desire to go home to Prussia, to get away from the king, to see the world, or to find happiness away from England—whatever the cause, she departed in August 1814. With peace restored and Napoléon in Elba, now was her moment to travel.

For the next six years, Europe was her unwilling playground. With a small train of chambermaids and chamberlains in tow, “the tatterdemalion caravan,” to borrow Joanna Richardson’s phrase, frolicked across Europe.[21] After spending several months in Brunswick, she stopped at Milan, Bologna, Florence, and Rome before reaching Naples, her intended destination. Unwilling to stay too long in any one place, the restless princess traveled on to Africa, Constantinople, the Holy Land, and back again through Europe. She was a woman without a home and on the loose, lavishly spending money on balls, clothing, and food. A traveling embarrassment to England, she soon met Bartolomeu Pergami, a handsome Italian security guard, whom she assigned to her entourage and upon whom she conferred the title Baron de la Francino. All of England was atwitter with accounts of the German-born English queen under the spell of her Italian dandy.

With his daughter now dead and his wife away carousing on the Continent, Prince George determined to divorce, believing, at fifty-nine years of age, that it might not yet be too late to sire another legitimate heir. However, obtaining such a divorce would not come easily. Constitutionally, adultery would have to be proven; it was an act potentially seen as tantamount to high treason against the state and often punishable by death. As for Caroline, although she was willing to grant a separation, she resolutely opposed divorce, which would remove her royal privileges and the chance to be queen. If not for reasons of privilege, style, and wealth, she would have resisted out of spite. Once a royal commission—the so-called Milan Commission—had been established to spy on and prove her activities, Caroline began to fear for her life. All such things, coupled with the news of King George III’s death, induced her to return to England, where she would test the levels of popular support and fight it out with the new king. It was a fateful decision, for the new king and the queen neither cared about nor understood the economic, social, and political unrest then gripping the nation.

An Age of Improvement?

As interesting as the warfare between these two quarreling monarchs may have been, by far the more important story of the age was the mighty changes wrenching their way throughout Great Britain that shook society to its core, arguably improving the everyday standard of living for millions of people and laying the groundwork for our modern era. The specific post-Waterloo years from 1815 to 1819 were especially painful and led England to the cusp of a political revolution on the eve of Caroline’s return. “From all parts of the country came reports of violence and crime,” as the British historian J. A. R. Marriott has contended. “In the Eastern countries there was an alarming amount of unrest and disorder. Barns and bricks were burnt to the ground; threshing machines and other agricultural implements were publicly burned; bakers’ and butchers’ shops were attacked, and angry mobs demanded ‘bread or blood.’ . . . Immense damage was inflicted upon property. . . . Nor was the unrest confined to the agricultural countries. The Tyneside colliers, the Preston cotton-weavers, the Wiltshire cloth-workers, the Monmouthshire and Staffordshire iron-workers, the jute-workers of Dundee—all alike were in turmoil, demanding more employment, higher wages, and cheaper food.”[22]

The immediate postwar era constituted a cold, wintry period in an otherwise warming spring. Just as the French Revolution heralded a time of new freedoms and the Congress of Vienna ensured a century of peace, so likewise did the Industrial Revolution ensure the promise of a better age, but only over time. Life in Great Britain was rapidly improving for the majority of people, and while not every improvement or change can or ought to be attributed to the Industrial Revolution, it gradually and inexorably changed daily life for millions and surely stands as the gateway to a new and better day, the foundation of modern society.

In the words of historian Asa Briggs, “If France had a political revolution in 1789, England had an industrial revolution already in progress.”[23] Simplifying the incredible complexity of the Industrial Revolution and the new enabling economic order ushered in by the economist Adam Smith (1723–90) with his pathbreaking work Wealth of Nations (1776) is no small order. It might be better to tell of three simultaneous, interlocking revolutions rather than one. It was a trinity of change in one essential union of societal reformation, with gradual, uneven stops and starts that occurred between 1760 and 1830. The first was demographic; the second agricultural; and the third, industrial and economic. While these changes were certainly not confined to Great Britain they followed hard thereafter in Europe and in North America), they were at first most concentrated in an England, Scotland, and Wales untouched by the recent ravages of war. Furthermore, Great Britain was blessed with such other unique advantages as naval supremacy, a developing colonial empire of abundant raw resources, a rapidly improving system of roads and canals, an improving banking system, relatively low taxation, a government that ensured freedom and encouraged innovation, a seemingly endless supply of keen inventors and curious engineers (men with the “mechanical hobby,” to borrow J. H. Clapham’s term), a growing amount of food, and an enormous supply of coal and iron located in close proximity one to another.

Two important points must be made about population: first, unparalleled growth and second, movement. Between 1750 and 1820, the population of Great Britain grew extraordinarily fast—it doubled, in fact—in what J. H. Clapham called “the flood of life.” From 7.3 million in 1751, the population in Great Britain increased to 11 million in 1801, to 12.6 million ten years later, and to 14.4 million in 1821, despite an ever-increasing exodus to Canada, Australia, and the United States, a trend that dramatically increased during the second quarter of the century.[24] Such rise in population drove Thomas Malthus (1766–1834), in his ponderous study on the sources of poverty, to gloomily predict in his Essays on Population (1798) widescale famine, death, and self-destruction in a world unable to feed so many mouths. What Malthus failed to anticipate were the twice as many hands available to plant and harvest, which led to the dramatic increase in agricultural yields of the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He also failed to take into account the twentyfold increases in average real per capita gross domestic product since his time, allowing for more to be spent on nutrition, sanitation, and health care.

This population growth was more the effect of a dramatic decrease in death rates starting in the mid-eighteenth century than a rising birth rate. Advances in medicine—including the conquest of smallpox, the disappearance of scurvy (at least on land), improvements in obstetrics (leading to less death among infants and mothers in childbirth), the growing number of better trained doctors and midwives, and the spreading and improving of hospitals, dispensaries, and medical schools—were definitely mitigating factors.

Improvements in sanitation and personal hygiene also contributed to population growth. With better soaps and purer water supplies, people washed their clothes and themselves more regularly. The number of cesspools decreased as water closets improved drainage and public sewer systems increased. Dirty and antiquated farmhouses and putrid privies were steadily replaced. Newer, cheaper, and cleaner cotton clothing became available, allowing for more frequent changes in wardrobes. It was, to be concise, a cleaner, healthier age, a breath of fresher air. People looked better, smelled better, ate better. Vegetables were more readily available, as even the most common laborers had small gardens and a potato patch. And with improvements in travel and communication, some of the more fortunate escaped to the lake events or to coastal towns and villages—resorts in embryo—although the masses could ill afford to travel too far away from their village hovels.

The result of such change and improvements was, as N. F. R. Crafts has carefully pointed out, a dramatic shift in labor. In 1750, 55 percent of the workforce was concentrated in agriculture, and by 1850 that figure had dropped to merely 22 percent. Similarly, in 1750 some 21 percent of the population lived in towns, compared to 54 percent a century later.[25] The shift to urbanization was in full swing.

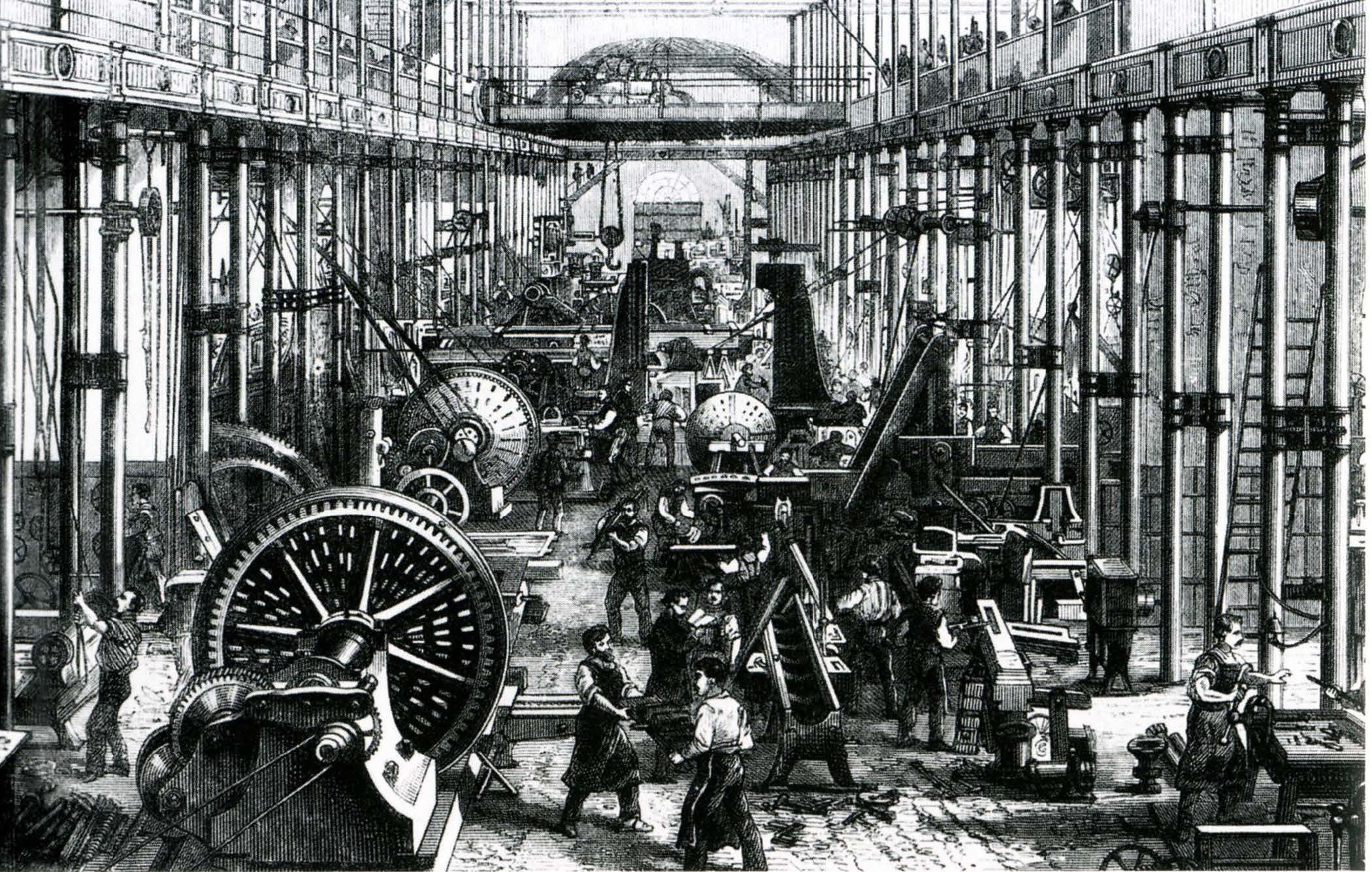

Machines of the Industrial Revolution. Hartmann Maschinenhalle (1868), by unknown artist.

Machines of the Industrial Revolution. Hartmann Maschinenhalle (1868), by unknown artist.

The agrarian revolution likewise contributed to making life more bearable, sustainable, and attractive. Heavy remnants of feudalism, such as open field farming in the form of narrow strips of land with bulks of uncultivated land separating them—what might simplistically be called subsistence agriculture—were giving way to more efficient and profitable techniques. These included husbandry of larger farms and land enclosures, specialization in better summer and winter crops, improved crop rotations, more durable breeds of cattle and sheep, improved top drainage, and better farm implements. Large farm holders and landed proprietors dramatically increased the amount of enclosed or fenced land, especially after 1760, and also increased the number of tenant farmers by buying up large amounts of common pasture and wastelands previously in possession of the village as a whole. This had the unfortunate result of driving many yeoman and peasant poor from their tiny family holdings. Dispossessed and often living on the verge of starvation, these cottagers either became the hired laborers of their new landlords or left to work in collieries (coal mines), factories, or foundries. The net demographic result, as already shown, was a steady shift from rural hamlets and villages to the urban towns and cities.[26] Difficult and traumatic as these changes were for common people, crop yields dramatically improved, as did the supply of meat, cheese, and milk, which permitted the feeding of a rapidly growing and increasingly urbanized population.[27] This agrarian revolution fed the increase in population that in turn fueled the fire of the Industrial Revolution.

The essence of the Industrial Revolution was the harnessing and specialized application of steam power and with it, the invention of new tools and machines that transformed and greatly enhanced methods of production. Such advances led to a rapid rise in industrial output, especially in the textile, coal, iron, and transportation industries, all of which led to increased productivity, rapid urbanization, the proliferation of factories, and the relentless relocation of labor. The Industrial Revolution demanded the new economics of competitive capitalization or, as Arnold Toynbee phrased it, the “substitution of competition for the medieval regulations which had previously controlled the production and distribution of wealth.”[28] The new machines and the rise of the forge and the factory gradually replaced the domestic system so long in vogue, although many of the greatest changes did not occur until after 1820, by which time Great Britain had become the workshop of the world.

The introduction of steam power as the “all-powerful agent,” as Briggs has phrased it, afforded two indispensable advantages: first, the necessary power to manufacture vastly increased volumes of materials in virtually every branch of production, and, second, freeing industry from its dependence on water power and having to locate mills and factories near rivers or falls.[29] There was as much geographical change as there was economic, for now factories of production could be built closer to the necessary resources of coal and iron, thereby ensuring the rise of company towns such as the new industrial cities of Manchester, Sheffield, and Birmingham. Manchester alone grew from 75,000 in 1801 to 303,000 fifty years later, and Sheffield grew from 46,000 to 135,000.[30]

James Watt (1736–1819), a Scottish-born inventor and son of an architect, was a key figure in the birth of the new age. Thomas Newcomen, a Cornish mechanic, had previously invented steam pumps—or “fire-engines,” as they were more commonly called—long before Watt’s day and had pioneered water pumping operations needed for mines, floods, and the regulation of urban water supplies. In 1781 Watt, with the financial backing of Matthew Boulton, invented something of far greater importance. What he designed was a new and more efficient piston, combined with a rotary motion that, through a watch-like mechanism of interlocking gears, enabled his steam engine to be used directly to supply machine power, thereby giving “an immense impetus” to the growth of the factory system.[31]

The first massive application of Watt’s steam engine technology came in the textile industry. Improvements had been made to automate the spinning and weaving process, including John Kay’s (1704–79) “flying shuttle” (1733), James Hargreaves’s (1720–78) multiple spinning wheel or “spinning jenny” (1765), and Reverend Edmund Cartwright’s (1743–1823) “power loom” (1785). But it was Sir Richard Arkwright’s (1732–92) new water frames and cotton mills—first water-driven but soon geared to steam power—that quickly made cotton king. This allowed for the production of an entirely new line of clothing that soon far surpassed the traditional wool and silk industries in terms of volume, size of the labor force, and number of factories. The first Manchester steam-driven cotton loom factory was built in 1806. By 1818 there were over 2,000 such establishments, and by 1830 there were no less than 55,000. The wool industry was older and more resistant to modernization in part because they worked with heavier products such as broadcloth, blankets, and carpets, which defied simple mechanized procedures. Yet even with wool, mechanization predominated after 1820, as it did in the flax and silk-spinning industries.[32] Between the accession of King George III and the death of George IV, the output of the cotton industry increased an astonishing hundredfold.[33] Christopher Daniell argues that between 1760 and 1800, cotton cloth production rose in value from 227,000 pounds in 1760 to 16,000,000 pounds in 1800, a staggering 7,000 percent increase![34]

The second area where steam power came quickly into play was in iron making. John Wilkinson (1728–1808) was the first ironmaster to replace charcoal from burnt wood with coke from purified coal in blast furnaces. He also pioneered the use and manufacture of cast iron, thereby removing the need to access ever-depleting timber supplies. With new steam-powered machinery, blast furnaces became much bigger, hotter, and more efficient, producing larger volumes of cast iron and cast-iron goods than ever before. In 1788 Great Britain’s twenty-six charcoal furnaces produced a mere sixty-eight thousand tons of pig iron; by 1830 almost all had been replaced, and between 250 and 300 coke furnaces (many in Wales) were putting out some seven hundred thousand tons of pig iron annually—a tenfold increase in less than fifty years.

Thanks to the Scottish ironmaster Henry Cort (1741–1800) of Portsmouth and Peter Onions (1724–98) of Merthyr Tydfil, Wales, who simultaneously developed what is known as the puddling and rolling process, pig iron could now be smelted and refined into more malleable and usable wrought iron. Whereas pig iron was used in building cast-iron objects such as pots, kettles, cannons, stoves, nails and such, the stronger, more purified wrought or malleable iron was used to make tougher metal for rails, plates, and chains and finer applications such as gates, bridges, machines, and tools. With the proximity of coal to iron ore in northwest England, the iron industry inevitably congregated there.

The new demand for iron caused a commensurate growth in the coal and iron mining industry, especially in the northeast. In Yorkshire alone, the number of collieries increased from one to forty-one between 1800 and 1830 and from an annual production of 160,000 tons to almost 3,000,000 tons of coal. The number of workers, both above and below ground, climbed to 12,000.[35]

In the field of transportation and communication, through the work of John Loudon McAdam (1756–1836), a Scottish engineer, and Thomas Telford (1757–1837), a canal builder, the nation’s bumpy and often impassable muddy roads were vastly improved. McAdam pioneered the use of small, broken stones in much smoother road construction (“macadamization”). The era of canal building lasted from 1790 to 1830, and networks of such waterways coursed through most of England, carrying manufactured goods, raw resources, and an increasing number of passengers. George Stephenson’s (1781–1848) invention of the steam-driven iron horse earned him the title “Father of Railways.” His steam locomotive, called the “Rocket” (1829), set a new standard for speed and efficiency. Prior to Stephenson, a railroad was merely a horse-drawn feeder line connecting coalfields and factories with nearby rivers and canals. Come the invention of the iron horse, however, railways began connecting cities and towns, with the first railway being the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, which opened in September 1830.

With steam engines and iron came the age of steam on the water, first on river and then at sea, with the first iron steamship built by the American Robert Fulton (1765–1815), which sailed up the Hudson River in 1807.

Catharine Akerly Mitchill (1778–1864), wife of Senator Samuel L. Mitchill (1764–1831) of New York, witnessed the inaugural voyage of Mr. Fulton’s steamboat:

I had the opportunity of seeing her pass our house. She moved very rapidly through the water, with the high tide rather against her, without aid of sails. It was a novel and interesting sight. The experiment succeeds perfectly, and you may suppose that Mr. Fulton is much elated with his success. I walked up to the Hook to look at her before she started, and had an invitation to take a sail in her; but declined the honor. The machinery is so complicated, and I understand it so little, that I shall not attempt a description, but it is certainly a very ingenious piece of workmanship. You would have been pleased to have seen her rolled along through the water by her two great arms, resembling the wheels of a grist mill.[36]

Henry Bell (1767–1830), Fulton’s tutor, returned to Glasgow in 1811, where he constructed the Comet, a steamboat that weighed twenty-five tons. The first passenger steamboat to sail the Thames was the Margery in 1815. In 1818 the first steam ships began making scheduled voyages at sea.[37]

If the changes in agriculture displaced the poorer segments of population, industrialization eventually scaled back the so-called domestic or putting-out system, where workers collected the raw materials, worked on them at the capitalist’s premises, and then sold them back to the supplier. Knitting and hosiery were essentially outwork industries where craftsmen and their helpers worked for the commercial entrepreneur. With the invention of the spinning jenny and looms run by steam power, machines became concentrated in mills and factories and demanded a far larger workforce of men, women, and even children.

The theoretical foundation to this changing economy lay in the writings of that apostle of capitalism, global growth, and the potential for accumulation of wealth—the Scottish-born Adam Smith. Smith was influenced by the ideas and events of the Protestant Reformation that resisted Catholic authority, the divine right of kings, and the status quo, and he wrote at a time when market forces were lessening the rigidities of the remaining feudal and medieval practices and the mercantilism that followed them. He saw the potential of individuals to act, as economist Alan Greenspan has argued, “independently of ecclesiastic and state restraint” and in an era of economic freedom. A “whole new system of enterprise” was now possible.[38] As Smith wrote in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, every man should be “free to pursue his own interest in his own way and to bring both his industry and capital into competition with those of . . . other . . . men.”[39] He also recognized the enormous “productive powers of labor” and argued that freedom, capital, vision, and labor, when combined with the above-described principles would promote the public good by developing a whole new system of enterprise and would increase the wealth and the standards of living in potentially every nation and in virtually limitless ways. His argument provided for a whole new class of merchants, traders, and manufacturers. “Perhaps if the Wealth of Nations had never been written, the Industrial Revolution would still have proceeded . . . at an impressive pace,” Greenspan further argued. “But without his demonstration of the inherent stability and growth of what we now term free-market capitalism, the remarkable advance of material well-being for whole nations might well have been quashed.”[40]

Of course, not everyone agreed with Adam Smith, and some elements of his arguments were later modified. He naively believed in the unselfishness of men. Social reformers like Robert Owen (1771–1858) and Lord Shaftesbury (1801–85) campaigned hard against unrestrained laissez-faire that, if left unchecked, led to poverty, child exploitation, disease, and premature death. Owen criticized the religions of the day for emphasizing too much the state of the soul hereafter and too little the fair treatment and improvement of the worker’s plight in the present world. Improving one’s environment improved one’s character as much as going to church or reading the Bible ever did. His school of utopian socialists and new villages of cooperation, such as his 1826 New Harmony experiment in Indiana in the United States, were failed attempts to rectify what he perceived to be untrammeled capitalism.

The cost of all this economic progress and of the age of improvement, as well argued by Briggs and other scholars, came at a terrible price. The very conditions that brought wealth to the landed interests and manufacturers often brought misery to the laboring class. As historian Alfred Henry Sweet has pointed out, cotton spinners who were working seventy-four hours a week in 1801 were paid a meager thirty-six shillings and six pence, and weavers were paid only seven to eleven shillings a week.[41] The hardships of poverty, dislocation, family rupture, inhumane working conditions, child exploitation, fractious employee-employer relationships—to name but a few—were all too painfully real. Not all were necessary, and few can be defended in the name of economic progress. Whenever technology changes and advances, human nature remains doggedly the same. Greed, selfishness, and corruption have never been vanquished simply by changing technologies.

Historian William Cunningham has noted that while many in the rising ranks of entrepreneurs believed the “production of increased quantities of material goods” was the only valid means by which to improve society, “they seemed to attach very little importance to measures for the direct protection of human life.”[42]

Women in the Industrial Revolution. Power Loom Weaving, by unknown artist. Courtesy of Wellcome Collection.

Women in the Industrial Revolution. Power Loom Weaving, by unknown artist. Courtesy of Wellcome Collection.

In the textile industry, at least in the early years, women, youth, and children predominated because they could be paid less than male adults, especially handloom weavers and framework twitters. Pay was minimal, and working conditions were dismal, if not frightful. In the textile mills, for instance, because of the nature of the material, it was best to spin and weave flax when it was wet. Consequently, workers labored all day standing up in a continual cold, wet spray, their hands constantly sore from never being dry.

Factory children fared little better. Parents were known to carry their children to the mills in the morning on their backs and then carry them back again at night. Both girls and boys, some no more than six years old, often worked thirteen- to fourteen-hour days, starting work at three or four in the morning, with little time off for meals or rest breaks. Reported one young man: “Am twelve years old. Have been in the mill twelve months. Begin at six o’clock, and stop at half past seven. Generally have about twelve hours and a half of it. Have worked over-hours for two or three weeks together. Worked breakfast time and tea-time and did not go away till eight.” Another worker stated, “We only get a penny an hour for over-time. . . . We used to come at half-past eight at night, and work all night, till the rest of the girls came in the morning. They would come at seven. Sometimes we worked on till half-past eight the next night, after we had been working all the night before. We worked in meal-hours, except at dinner. . . . It was just as the overlooker chose.”[43]

It was only in the 1830s that factory reforms and establishing ten-hour days for children were initiated by Robert Owen. The smaller mills were decidedly the worst, with children often severely punished by tyrannical supervisors for tardiness, lack of performance, or even illness. Sanitation was often wholly lacking, and the frequency of accidents was especially shocking because of overcrowded conditions, overworked machinery, and tired and underpaid laborers.

The employment of women and children in the collieries was a particularly disgusting and brutalizing state of affairs that had negative impacts on families. As more and more women left their homes to work in such places, as well as in factories, infants were neglected. To what extent sexual immorality increased among both men and women because of families under economic stress is debatable. Yet, as one witness declared before a Parliamentary Factory Commission in 1833, prostitution was rampant: “It would be no strain on his conscience to say that three-quarters of young women between fourteen and twenty years of age were unchaste” and that “some of the married women were as bad as the girls.”[44]

The stress on family life was increasingly exacerbated. Farm laborer families were torn asunder in the tiring efforts to make a barely subsistent living. The accounts of pregnant women, covered in coal dust, lugging bags of coal over their heads and on their backs while climbing up broken ladders to the mine’s surface are easy to find. Boys and some girls—some only six or seven years old—would go down with the men at four o’clock in the morning and remain in a stope or pit, six hundred feet deep, for up to twelve hours. One six-year-old child had the forlorn duty of opening and shutting the traps or doors to prevent flammable drafts whenever the coal wagons would pass and repass.[45]

Looking over the bustling city of Birmingham now so dramatically transformed by such economic ‘progress’, Robert Southey saw it as little better than a new blight on English society: “A heavy cloud of smoke hung over the city, above which in many places black columns were sent up with prodigious force from the steam-engines . . . the contagion spread far and wide. Every where around us . . . the tower of some manufactory was seen at a distance, vomiting up flames and smoke, and blasting everything around with its metallic vapours. The vicinity was as thickly peopled as that of London. . . . Such swarms of children I never beheld in any other place, nor such wretched ones.”[46]

Defenders of the new order said that families worked no harder in factories, workshops, and mines than they had on farms, where they had eked out an even worse standard of living. But, given the overwhelming evidence and the eventual reforms mandated, it seems clear that many were exploited. Young mothers especially were deprived of caring for their infants and children, and infant mortality rates were markedly higher, sometimes as much as 50 percent or more.[47]

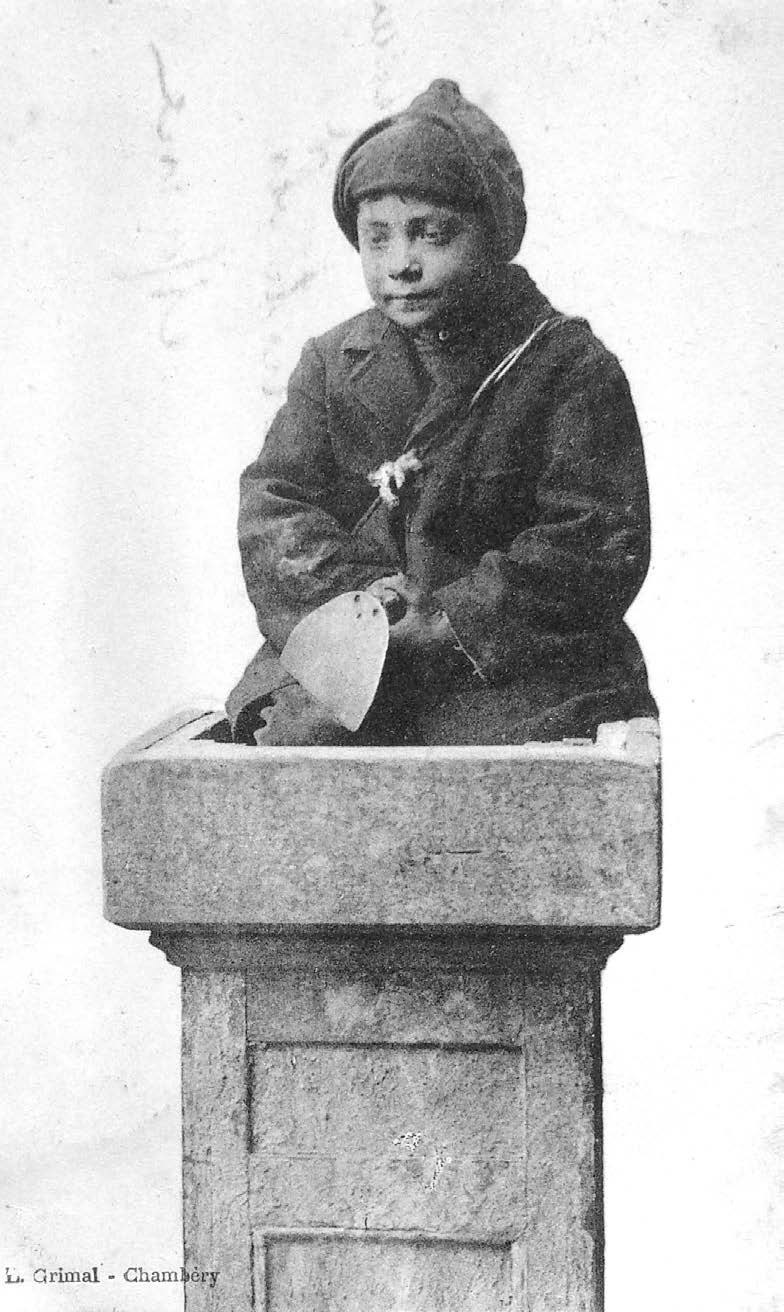

A postcard of a young chimney sweep. Little Savoyard Chimney Sweep, photographer unknown.

A postcard of a young chimney sweep. Little Savoyard Chimney Sweep, photographer unknown.

Perhaps the worst examples of child exploitation existed in London when chimney sweeps were in constant demand. With many flues no bigger than nine inches square, very small boys (and a few girls), no more than five or six years old, were sent out to work. Many got stuck and were then beaten. Some died. Even worse than sweeping a normal chimney was to clean a hot chimney. “Did your master or the journeymen ever direct you to go up a chimney that was on fire?” a young boy was once asked. “Yes, it is a general case.” “Do they compel you to go up a chimney that is on fire?” “Oh yes, it was the general practice for two of us to stop at home on Sunday to be ready in case.” The soot often remained on their unwashed bodies for a week or two. There is even evidence that some parents, especially poor single parents, sold their children as chimney slaves. Samuel T. Coleridge (see chapter 6) called them “our poor little white-slaves.” William Blake also spoke of this notorious trade in his “Songs of Innocence:”

When my mother died I was very young,

And my father sold me while yet my tongue

Could scarcely cry “’weep! ’weep! ’weep! ’weep!”

So your chimneys I sweep, and in soot I sleep.[48]

While some went up chimneys, others of these so-called street children—untutored, independent urchins—took on every job imaginable, including tumbling, fetching cabs, and even finding prostitutes for “gentlemen.” Tiny “nightmen” were let down holes and into privies, where they forlornly splashed about fetching watches and other lost articles. Such dirty, young, and barefoot lads were often employed by a master who forced them to sleep in cellars without a bed.[49]

A combination of interrelated factors in postwar England from 1815 to 1819 created an “unprecedented stagnation of every branch of commerce and manufacture,” or in today’s parlance, a perfect storm. The rapid demobilization of over 330,000 sailors and soldiers after Napoléon’s defeat flooded an already saturated labor market and led to widescale and massive unemployment. Continental buyers were impoverished by the great war. Price inflation had greatly increased the cost of living, while taxation was at an all-time high in order to pay off the nation’s enormous war debts. Antistrike legislation made workers powerless to organize. To make matters worse, crops were almost ruinous in 1816 and 1817, and Parliament had recently passed Poor Laws and Corn Laws at the behest of landowners, which placed artificially high tariffs on imported grain and encouraged idleness and the dole. All these factors resulted in the economic depression of 1819, with its tell-tale signs of tight and shrinking credit, sharp declines in property values, a spike in the number of bank failures and bankruptcies, massive unemployment, and all around economic turmoil and suffering. The following extract of an 1818 letter from a village in Scotland puts the dire situation of the common laborer into perspective:

This county is still in a miserable state, for although trade is getting rather better, yet numbers are still out of work and the landed proprietors taking advantage of this, endeavor to reduce the price of labor as much as possible. . . . A laborer’s wages are from one shilling to one shilling three pence per day. Oatmeal from one shilling and eight pence, to two shillings per peck. Indeed you will be hardly able to imagine how a poor man can manage to keep himself and family alive from this pittance. . . . Many families have nothing but potatoes three times a day.[50]

Add to this distressing scene the rise in contagious fevers such as typhus, scarlet fever, and whooping cough, in part contracted by returning soldiers (much like how the Spanish influenza killed millions worldwide a century later), and one begins to question the term “age of improvement.”[51]

The end result of all such discomfitures was a series of mass meetings, a rise in radical agitation, assassination attempts, and worker-inspired riots that rocked the nation. William Cobbett (1763–1835), a brilliant labor pamphleteer, demanded such political reforms as universal suffrage and annual Parliaments, and Lord Byron used his sarcasm to pour contempt on Parliament. Most notable were the Greenock riots in Scotland, the Spa Field riots of 1816, the Pentridge’s rising in 1817, and the Scottish insurrection of 1820 and with it the execution of James Wilson. In Manchester, which was not even represented in Parliament, a crowd of over fifty thousand amassed in protest on 16 August 1819 at St. Peter’s Field. Henry Hunt (1773–1835) and other radical labor orators received a hero’s welcome, and their highly inflammatory speeches fanned discontent. Fearful of a riot, authorities ordered the dispersal of the protesters. When the crowds resisted, a cavalry charge ensued with sabers in hand. Eleven people, including two women, were hacked to death, and four hundred others were injured in the ensuing stampede. The Peterloo Massacre, as it became known, greatly frightened the nation. Parliament reacted repressively and failed to ease the tension when it sentenced Hunt to two and a half years’ imprisonment and forbade future public meetings in the name of preserving peace and public safety.[52]

In 1820 a group of radicals from their headquarters in Cato Street in London, conspired to murder the entire cabinet while dining at a house in Grosvenor Square and then seize the Bank of England, but the plot was betrayed at the very last moment. This “Cato Conspiracy” resulted in the execution of several conspirators and placed the government on a near-panic footing. There can be little doubt that the nation was in despair, and many feared an imminent revolution, which might well have occurred had not crops and employment dramatically improved in 1820.

At this turbulent time, the wandering Queen Caroline decided to return to capitalize on the seething, widespread unrest aimed at a Parliament and a king too preoccupied and oblivious to the crises of working men, women, and children.

“What a Stir, What Excitement, What Noise”

Quitting Rome on 8 April and crossing the Alps into Switzerland, Caroline, “like any general on the move,” resolutely formed her plans on the go.[53] She traveled swiftly in a “miserable half-broken down carriage covered with dust” to Geneva and thence down the Rhone valley to Lyon, Villeneuve, and St. Omer, eventually reaching Calais in early June, where hundreds of curious French onlookers crowded the pier. Her request for a royal yacht denied, she and her small traveling party embarked directly onboard the Prince Leopold. At six o’clock on the morning of 5 June, she set sail, crossing the Channel in seven hours. Disembarking at one in the afternoon, she was greeted by a royal salute in the form of a roar of cannon from Dover Castle, accompanied by lusty cries of “God Bless Queen Caroline” from some ten thousand cheering well-wishers. Waving to all her jubilant supporters as if running for election, she sped westward to London, traveling through Canterbury, Sittingbourn, Chatham, Deptford, Greenwich, and other towns, where rumors of her impending arrival had spread like prairie wildfire. In every town and hamlet, the locals insisted upon drawing “Her Majesty” through the town, displaying royal insignia and Union Jack flags from building windows on each side of her route. Some were even strewn across the road. Well-dressed ladies were seen everywhere waving their handkerchiefs and joining in the general exclamations of “Long Live Our Gracious Queen. Long Live Queen Caroline.” Wrote one London Times reporter, “The bells of the churches were set ringing, and all was joy and exultation.”[54]

As she traveled further west, so many new horsemen and carriages joined her royal entourage that by the time she reached London, like another William the Conqueror or a triumphant Napoléon returning from Elba, she presided over a veritable army of devoted, cheering followers. It seemed like all of England had stirred to support her return. “The Queen of England now occupies all thoughts,” this same reporter observed, “and is at present every thing with every body.”[55] Robert Peel (1788–1850) spoke more perceptively of “a feeling, becoming daily more general and more confirmed . . . in favour of some undefined change in the mode of governing the country. . . . Public opinion never had such influence on public measures, and yet never was so dissatisfied with the share it possessed. It is growing too large for the channels that it has been accustomed to run through.”[56] And wrote the editors of the Ladies’ Literary Cabinet, “From the obstinacy of the King and his ministers, and the strength of the new queen’s party, it would not be surprising if a civil war were to grow out of this affair.”[57]

Shortly after Caroline’s return to London (without Pergami), by order of the king, Lord Liverpool (1770–1828), his Tory prime minister, reluctantly introduced to Parliament a “Bill of Pains and Penalties against her Majesty,” charging Queen Caroline with “an adulterous intercourse with Pergami, her menial servant” and proposing that she should be “degraded” from the title and station of queen and that her marriage with the king should be “dissolved.”[58] Liverpool’s reluctance stemmed not from any lack of evidence in the king’s “Green Bag” of documentation but from his sense that the king would lose in winning, especially among the masses. A guilty verdict might well result not merely in a loss of Tory support but also in a revolution against the monarchy and the establishment of a republican form of government that many radicals and some of his Whig counterparts had been clamoring for ever since the French and American Revolutions. At stake were not merely the whims of a highly unpopular king and a troubled, embarrassing queen, but the very form of future British governments. Civil war might well erupt.

The ensuing trial lasted almost three months. The crown had enough witnesses and sufficient evidence, but the queen, who often attended the court in person, was masterfully represented by Henry Brougham, the ablest of the young Whigs, who admitted the queen’s faults but still fully played up the king’s unfairness to her through the years, his double standard of behavior, and his 1797 letter granting her, in effect, license for what he was now trying to condemn. After a long, hot summer, the bill passed first, second, and third and final readings in the House of Lords, though with steadily eroding support with each successive vote. Well aware that popular opinion was rising in support of the victim queen (“The Queen forever! The King in the River!”[59]) and that a verdict against her might result in a tidal wave of anger, especially among her many female supporters, Prime Minister Liverpool astutely called for a time out. Instead of moving “that this bill do pass” for consideration in the lower House of Commons, he postponed further action for a period of six months. The London mobs erupted with joy. “Caroline the Glorious” was granted an annuity of fifty thousand pounds but no castle.[60]

Popular support for Caroline, however, proved fickle and short-lived. The evidence produced at trial had proven the baseness of her character and her subsequent drunken parties, outlandish dress, and uncouth behavior at theaters and balls in London disgraced her dignity and was an affront to her supporters. If she had successfully counted on public favor, she was now squandering it. Said Lady Cowper, “There never was such an Apple of Discord as that woman has been.”[61]

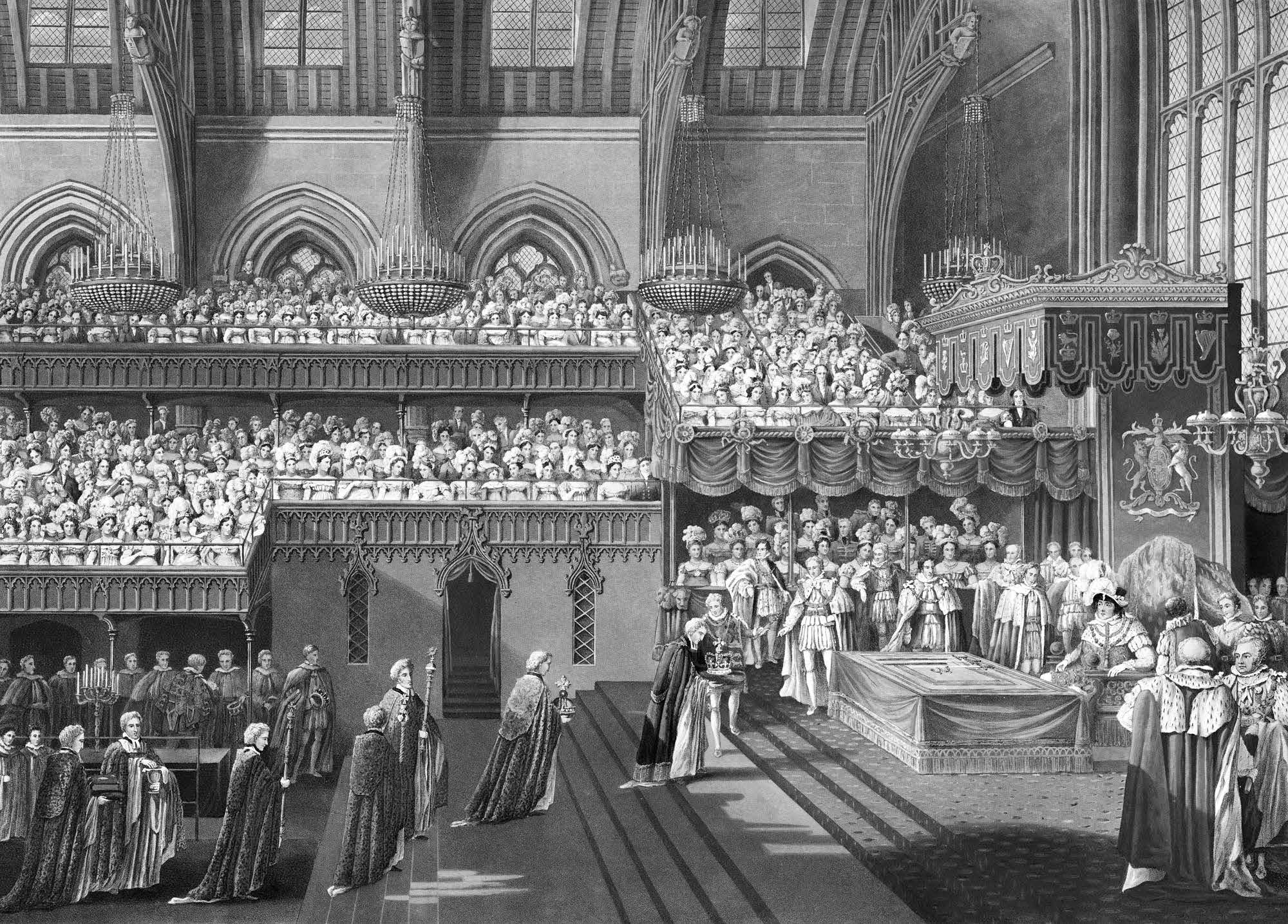

Coronation Banquet of King George IV of Great Britain, by Sir George Naylor, 19 July 1821.

Coronation Banquet of King George IV of Great Britain, by Sir George Naylor, 19 July 1821.

Surely one of the most pathetic moments in the annals of British Royalty occurred on 19 July 1821, the day George IV was crowned in a glory of unsurpassed pomp and ceremony at Westminster Abbey. His new crown featured 12,532 diamonds, and his coronation robes, trimmed with gold, took nine pages to support, while Caroline, uninvited and unwelcomed, was twice barred from entering. The great hall had begun to fill up as early as one o’clock in the morning. Caroline arrived at 5:30 in a morning already lit by the rising summer sun and knocked personally at the door at Poet’s Corner but was refused entrance because she had no ticket. In tears, she climbed back into her carriage amid such insults from the crowd as “Go home, you common disturber” and “Go back to Pergami.” She circled about and tried yet a second time to enter Westminster Hall, only to have a hunched red-robed page bang the door shut in her face. Demanding a coronation of her own in two or three weeks’ time, her reputation sullied, and whatever little dignity she had left now in tatters, Caroline returned to her rented residence where she took sick, and died three weeks later on 7 August 1821, if not from an overdose of laudanum and excessive blood-letting, then surely of acute depression and a broken heart. There was little mourning at her private funeral, and she was quietly laid to rest in Harwick, eighty miles away from her few remaining London supporters.

A Sordid Legacy

Queen Caroline was an unhappy figure, ill-equipped for her royal role. She may well have had the same afflictions that robbed her father-in-law of his sanity. She managed to offend even her most ardent supporters as she unloved and essentially unappreciated, wore out her welcome. Seldom before had anyone galvanized public opinion so quickly, then lost it so decidedly. Her escapades both home and abroad, her fateful return to England, and her subsequent trial and sorry end all contributed to the birth of a popular press that spun off hundreds of thousands of pamphlets, broadsides, squibs, and penny-a-yard ballads that resulted in the divorce bill being dropped.[62] It may well be argued that the trial of Queen Caroline was “the spark that set Britain on the road to political reform.”[63] Certainly it sparked the rise of a truly popular press with the London Times and William Cobbett’s pamphleteering, which all demanded change and reform.

By 1822 the worst of the postwar adjustment had passed. The economy was rapidly improving in what might be called the first boom of the industrial era. Soon public tensions eased. With the suicidal death of the foreign secretary Castlereagh in 1822, King George IV appointed the generous-minded George Canning (1770–1827) in his place and Sir Robert Peel (1788–1850), son of a cotton spinner, as home secretary. Both Tories under Liverpool, Peel and Canning practiced a brand of social or Tory liberalism, being much more attuned to the suffering and welfare of the middle and lower classes than aligned with the aristocracy. Peel took up the cause of penal and prison reform, greatly reduced the number of capital (death penalty) offenses, and sought for and obtained Roman Catholic emancipation. Fearful of another Peterloo Massacre debacle, Peel established the London Metropolitan Police, an unarmed but highly trained force soon nicknamed “bobbies,” after him. In the hopes of lessening support for the radical cause, working class claims were more fully entertained and trade unionism grew steadily, especially in the shipbuilding, manufacturing, and mining industries, with John Doherty as a leading figure. In foreign affairs, Canning’s new Navigation Act permitted freer trade between the colonial empire and Europe, and tariffs were reduced. After a short, more conservative reign under Prime Minister Wellington from 1827 to 1830, during which time Parliament passed the long overdue Catholic Emancipation Act, Charles Grey became prime minister in 1830 and, under the new Whig government, passed the famous Reform Bill of 1832, which put resolutions to the grievances of a generation into law.

The great Reform Bill of 1832, a major turning point in British history, owed much to many people, including many reform-minded souls already discussed—William Cobbett, Robert Peel, Robert Owen, Anthony Ashley-Cooper (Lord Shaftesbury), William Wilberforce (see chapter 8), and Charles Grey. The rising middle class of merchants and industrial employees in the Midlands and the North also wanted policies and laws less favorable to the interests of the landowners. Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), the philosopher and famous social reformer, believed that government existed to ensure the greatest happiness of the greatest number, and the more Parliament listened to the voice of the majority and less to the vested interests, the better life would be for all.[64]

Among other things, the Reform Bill disenfranchised scores of boroughs, more than doubled the number of people entitled to vote, increased representation from counties and cities heretofore unrepresented, and increased Scottish and Irish representation. This important piece of legislation took power from the upper social class and gave it to the strongly emerging middle classes; there was more democratic power for the people. And the very next year Lord Shaftesbury succeeded in finally passing his Factory Act, forbidding child labor for those under nine years of age and limiting the hours of women and children to ten a day.

And as for Prinny, finally King George IV, he would reign over England for the next decade. A man of style, he did not follow fashions; he set them. A patron of the arts and of literature, he donated his father’s library to form the basis of the British Museum Library. He loved the writings of Jane Austen, Sir Walter Scott, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. He encouraged the renaissance of the ballet with such new brilliant dancers and choreographers as Lise Noblet, Fanny Bias, François Decombe, Charles Vestris, and James d’Egville.[65] His greatest legacy was in architecture: he built the Brighton Pavilion and Carlton House, extensively renovated and extended both Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace, and, with the help of architect John Nash (1752–1835), transformed and beautified the heart of Regency London by remodeling and replanting St. James’s and Regent’s Parks. His taste in furniture and ornamentation is still known as the Regency style. And, as perhaps the greatest common scion ever to sit on the British throne, he acquired the works of Rembrandt, Peter Paul Reubens, Aelbert Cuyp, and Pietrde Hooch, making it one of the finest art collections in the world. He commissioned every leading English painter, including Gainsborough, Reynolds, Lawrence, Stubbs, and Turner. His state visits to Ireland and Scotland set a new precedent and drew the monarchy closer to the people.

Of perhaps greater significance, his refusal to dismiss his Cabinet ministers if they disagreed with him during such crises and setbacks as the failed divorce trial was a major step toward a constitutional monarchy with more power vested in Cabinet and Parliament than ever before.[66]

For all his accomplishments, King George IV lived out his life a lonely and tragic figure. At his death in June 1830 he was buried with a picture of Maria Fitzherbert around his neck, who died on a dark and windy day seven years later. He was little more than an entertaining shadow, and a very expensive one at that. Concluded one leading scholar of British royalty: “It is sad that one of the most gifted of British monarchs was, by the time of his death, also one of the most despised. George IV’s undoubted charm, his evident wit, his innate aesthetic sense, his enthusiasm and his imagination ultimately left him insufficiently equipped to rise to the challenge of a nation daily growing in self-confidence and wealth. His self-indulgence and short attention span, together with his evident ability to abandon political principles and to forget friendships with barely a backward glance, won him few encomiums after his death.”[67] And, as the royal historian Sir Owen Moreshead concluded: “George IV had melted like a snowman: only the clothes remained.”[68]

When King George IV died in June 1830, few mourned his passing. He was neither loved nor respected. He had grown so enormously fat and increasingly out of touch with his subjects that he was enveloped by the disdain that had followed him since before Caroline. His childless second brother, the Duke of Clarence, had already predeceased him. Next in line was his third brother, William, Duke of Clarence, who became king in 1830. Upon William’s death in 1837, and that of two of his oldest daughters, the scepter fell on one few had ever imagined would ascend—Queen Victoria (1819–1901)—the unlikely monarch who would reign over England and the British Empire for the next sixty-three years.

The impact of King George IV and Queen Caroline, despite their many flaws, was paradoxically positive and far-reaching. After the trial, there was a “softening in the Tory style of government.” Governments seemed “less willing to use old methods of suppressing dissent.” Public opinion had triumphed and would now be of a positive force in shaping legislation than ever before. And the power of the press, the popular press, was now recognized as a powerful influence on molding public opinion and legislative initiatives.[69]

It is nigh impossible to measuer or assess how the Industrial Revolution influenced religion generally. But certainly advances and improvements in land and sea transportation, communication, capitalization, and rapid urbanization changed and facilitated missionary work, the gathering impulse, publishing efforts, and intercity communication. The effects which the Industrial Revolution had upon the later arrival of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints beginning in 1837 would be substantial. It is a well-established fact that most Latter-day Saint converts came mainly from the laboring classes in the industrial regions of northwest England.[70] Dislocation, rapid urbanization, displacement of workers and their families, poor working conditions for many, child labor, unequal distribution of wealth and services, and the economic depression of the late 1830s and early 1840s—all these and other related factors “helped create an atmosphere for success” when Latter-day Saint missionaries began spreading their message of faith and hope. Between 1837 and 1848, the number of British Latter-day Saint converts skyrocketed from a mere handful to about 31,000.[71] Likewise, their invitation to new converts to emigrate to America would play well at a time when the total annual figures of British emigrants bound mainly for America and Canada reached as high as 250,000, some of them Latter-day Saints. It marked a new harvest of emigrant converts that continues to bless the Church into the twenty-first century.

Notes

[1] The terms England and Great Britain are not synonymous. As a result of the Act of Union in 1801, England, Wales, and Scotland together became the nation of Great Britain. When Ireland was added, the term United Kingdom came into being.

[2] Flora Fraser, The Unruly Queen (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996), 353.

[3] Jane Robins, Trial of Queen Caroline: The scandalous Affair that Nearly Ended a Monarchy (New York: Free Press, 2006), 123.

[4] Robins, Trial of Queen Caroline, 123.

[5] Robins, Trial of Queen Caroline, 123.

[6] Robins, Trial of Queen Caroline, 126.

[7] Kenneth Baker, “George IV: A Sketch.” History Today (October 2005), 30.

[8] Kings and Queens of England and Great Britain. Ed. Eric R. Delderfield, (New York: David and Charles, 1970), 114.

[9] Joanna Richardson, The Disastrous Marriage: A Study of George IV and Caroline of Brunswick (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1960), 13.

[10] Heather Jenner, Royal Wives (London: Gerald Duckworth and Co, 1967), 226.

[11] E. A. Smith, George IV (New Haven: Yale University, 1999), 19.

[12] Smith, George IV, 20.

[13] Smith, George IV, 39.

[14] Richardson, Disastrous Marriage, 28–29.

[15] Richardson, Disastrous Marriage, 33.

[16] Richardson, Disastrous Marriage, 33–35.

[17] Richardson, Disastrous Marriage, 37.

[18] Richardson, Disastrous Marriage, 74–75.

[19] Smith, George IV, ch. 5.

[20] Fraser, Lives of the Kings and Queens of England, 285.

[21] Richardson, Disastrous Marriage, 93.

[22] Marriott, England Since Waterloo, 25–26.

[23] Briggs, Age of Improvement, 30.

[24] Clapham, Economic History of Modern Britain, 54–55.

[25] Crafts, British Economic Growth, 4, 65–69.

[26] Cole and Postgate, 120–23.

[27] Briggs, Age of Improvement, 34–36.

[28] Toynbee, Lectures on the Industrial Revolution, 85.

[29] Briggs, Age of Improvement, 21

[30] Eastwood, “Age of Uncertainty: Britain in the Early Nineteenth Century,” in Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 8:100.

[31] Cole and Postgate, British People, 133.

[32] Clapham, Economic History of Modern Britain, 143–47.

[33] Trevelyan, British History in the Nineteenth Century and After, 155.

[34] Daniell, Traveller’s History of England, 168.

[35] Clapham, Economic History of Modern Britain, 186.

[36] Catherine Mitchill to her sister, 17 August 1870, Catherine Mitchill Papers, Library of Congress, MSS Division, Washington, DC.

[37] Thornton, Short Account of the Origin of Steam Boats, 29–37.

[38] Alan Greenspan, The Adam Smith Lecture, Fife College in Kirkcaldy, Scotland.

[39] Smith, Wealth of Nations, 687.

[40] Greenspan, Lecture.

[41] Sweet, History of England, 597.

[42] Cunningham, Growth of English Industry and Commerce, 775.

[43] Report of the Minutes of Evidence taken before the Select Committee on the State of Children employed in the Cotton Manufactures of the United Kingdom (1816), as cited in Cunningham, Growth of English Industry and Commerce, 779–82, 785–86.

[44] Harold James Perkin, The Origins of Modern English Society 1780-1880 (London: Routledge and K. Paul, 1969), 150.

[45] Cunningham, Growth of English Industry and Commerce, 805.

[46] Robert Southey, Letters from England (London: Longman, 1814), 203.

[47] Perkin, Origins of Modern English Society, 154–55.

[48] “The Chimney Sweeper” (1789), in Bernbaum, Anthology of Romanticism, 115.

[49] From An Account of the Proceedings of the Society for Superseding the Necessity of Climbing Boys, as cited in the Edinburgh Review 32 (1810): 309–14.

[50] “Foreign Affairs,” National Register, 21 November 1818, 6.

[51] Edinburgh Review 31 (1819): 415–19. See also Marriott, England Since Waterloo, 24–26.

[52] Anthony Babington, Military Intervention in Britain: From the Gordon Riots to the Gibralter Killings (London: Routledge, 1990), 46–58.

[53] Fraser, Unruly Queen, 355.

[54] London Times, 7 June 1820, 3.

[55] London Times, 7 June 1820, 3.

[56] Fraser, Unruly Queen, 365.

[57] “Queen of England,” Ladies’ Literary Cabinet 2, no. 2 (20 May 1820): 16.

[58] Campbell, Lives of the Lord Chancellors, 7:367.

[59] The Lives of the Kings and Queens of England. Ed. Antonia Fraser. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975), 287.

[60] Churchill, History of the English-Speaking Peoples, 4:17–21.

[61] Richardson, Disastrous Marriage, 198. Some people chanted, “Gracious Queen, We thee implore: Go away, sin no more. Or if the effort be too great, go away at any rate.” Richardson, Disastrous Marriage, 86.

[62] “A Right Royal Scandal,” Economist, 381.

[63] Robins, Trial of Queen Caroline, 319.

[64] Sweet, History of England, 615–16.

[65] Although ballet was still essentially a man’s art, the place of women was becoming increasingly center stage in the 1820s. The display of a ballerina’s legs was something recent in ballet as was the cultivation of the “pointe,” a female dancing on the very tips of her toes.

[66] Baker, George IV, 32.

[67] Parissien, “George IV,” 9–11.

[68] As cited in Parissien, “George IV,” 9–11.

[69] Robins, The Trial of Queen Caroline, 322.

[70] Allen, Esplin, and Whittaker, Men with a Mission, 18–19.

[71] Allen, Esplin, and Whittaker, Men with a Mission, 321.