Le Petit Caporal: Napoléon Bonaparte

Richard E. Bennett, “Le Petit Caporal: Napoleon Bonaparte,” in 1820: Dawning of the Restoration (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 1‒30.

The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries, by Jacques-Louis David.

The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries, by Jacques-Louis David.

By the spring of 1820, Napoléon Bonaparte’s health had begun to wane. Banished to the tiny, windswept island of St. Helena, far from anywhere in the South Atlantic, the former emperor of France languished in exile, reduced to the petty disciplines of a third-rate British officer. Napoléon spent his declining days riding horseback under the gaze of an uneasy regiment of British redcoats, gardening at Longwood—his small villa residence—and dictating his memoirs. He could only hope for better news from Europe—perhaps a release and safe passage to America.

What had brought him to this? And what is it about Napoléon that has since caused more biographies to be written about him than any other person in history except Jesus Christ? Napoléon’s story is one for the ages, but can claim him the year 1820 as one of its most celebrated figures and the dominant spirit of the age, one forged in the fiery furnace of the French Revolution, who went on to change the history of not only France but also the world.

“Puss in Boots”

Having just returned from attending mass, Letizia Buonaparte gave birth to her fourth child, her second son, in her small home in Ajaccio, on the island of Corsica, on 15 August 1769. Her husband, Carlo Buonaparte, though “very far from rich,” had gained a reputation for himself, having been elected to the council of twelve nobles in Corsica, which had only recently been wrested by the French from the hated Genoese. Ironically, they named their new son Nabulion, later christened Napoléon Bonaparte, after an uncle who had recently fought against the conquering French forces.[1]

As the second oldest son of a family of eight children—five brothers and three sisters—Napoléon grew up in an Italian-speaking, Roman Catholic home. Letizia was a strict disciplinarian whose deep maternal affections instilled in him a love for his mother that would last a lifetime. Although she tried to develop religious faith in the lad, his interests were ever more inclined to the military than to the church. While his brothers were drawing “grotesque figures on the walls of a large empty room which she had set apart for them to play in, Napoléon drew only soldiers ranged in order of battle.”[2] She encouraged his interests by securing for him a toy drum and a wooden saber. All through his growing up years, Letizia tried hard to teach him and all her other children a Christian sense of faith and morality as well as honor, fidelity, courage, and a strong sense of justice.

Meanwhile, Napoléon became increasingly aware of his father’s library, numbering over one thousand titles. No one knows just what books he read as a boy, but they were obviously instrumental in providing him an early worldview and in introducing him to some of the world’s greatest minds in politics, art, and literature. His greatest loves were history and geography.

When Napoléon was only nine years old, his watchful father determined to enroll him and his older brother Joseph in the Brienne Military Academy in Autun, France, if for no other reason than to help his sons become more proficient in French. Run by friars of the Roman Catholic Church, this elementary-school–like experience taught Napoléon far more than French (though he ever afterward spoke French with a thick Corsican accent, much to his embarrassment), for it was while at Brienne that he showed surprising skills in mathematics and military maneuvers. An “obedient, affable, straight forward and grateful” student, by the time Napoléon graduated (middle of his class) he fancied a career in writing and had come to believe less in God and more in France and its place of supremacy in the world.[3]

Upon graduation, Napoléon was one of only five chosen to continue military training at l’Ecole militaire de Paris in 1784. He was then only fifteen years old. Initially inclined to the navy, Napoléon later gravitated toward an interest in artillery warfare, and by the time he was commissioned a second lieutenant the following year, he had selected a career in the army. Never more than 5 feet, 6 inches tall, Napoléon took more than enough ribbing from his fellow officers as well as the teasing of his young female admirers, who called him “puss in boots.”[4]

With the death of his father in 1785, Lieutenant Bonaparte assumed the financial obligations of the family. As he read ever more seriously, including Plato, Rousseau, Voltaire, and James Macpherson, he concluded that what most ailed France was the virtually unlimited, absolute power of the king and the excessive privileges of the aristocracy and clergy. What France needed most urgently, he came to believe, was a new constitution, one that would ensure greater liberties, freedoms, and economic opportunities for the so-called third estate—the common people. Soon he was composing such essays as “Man Is Born to Be Happy” and “Morality Will Exist When Governments Are Free.”[5]

In 1789 his regiment was called up to quell some of the winter food riots that were then erupting in various parts of the country. Although he disliked King Louis XVI’s abuse of executive power, Napoléon deplored chaos, anarchy, and mob rule even more so. Before long, he found himself in the middle of a violent political upheaval that was rapidly spinning out of control, one destined to change modern European society forever.

Napoléon and the French Revolution

The seeds of the French Revolution may be traced to the embedded injustices of ancient feudal times. Over the centuries, French society had become stratified into three categories: “clerics who prayed, nobles who fought, and commoners who labored.”[6] Known as the first, second, and third estates respectively, the first two—the Roman Catholic Church clergy of bishops, priests, nuns, and friars and the landed gentry and nobility—came to be regarded as the “privileged orders,” which, if not above the law, certainly enjoyed a disproportionate share of benefits. These included much lower taxation rates, feudal powers over laborers, and immunity from many forms of legal prosecution.[7]

The third estate—the commoners—made up 98 percent of the nation’s population of twenty-seven million people (a true superpower in its time)[8] but enjoyed little, if any, individual power and only a small voice in the three-chambered French legislature. This old way of doing things—the so-called ancien régime—included a cumbersome judicial order, an inefficient system of local governments, an excessively complicated method of road tolls, and a porous, unfair, and punitive system of taxation. It also handicapped enterprising merchants and laborers, perpetuated vested class interests, stubbornly resisted reform, and caused France to lag behind England in enjoying the economic benefits of the Industrial Revolution. Overseeing and superintending it all was an absolute Bourbon monarchy, with its several tiers of overpaid regulators and ministers and a royal army officered by privileged sons of the landed gentry and French nobility.

Aware of the rising popular chorus for change and in desperate need for increased revenue, the French government considered making real reforms in 1787, particularly with respect to fairer taxation. The only way to solve the problem, however, was for the king to reconvene the French Parliament—the Estates General—in 1789.[9] In the meantime, bread riots had broken out all over the country, following poor harvests and a punishingly cold winter. In addition, common citizens began promoting a very successful pamphlet campaign aimed at doubling the power of the third estate’s voice in government at the expense of the clergy and aristocracy. With such actions, “the time-bomb of revolution . . . started ticking.”[10]

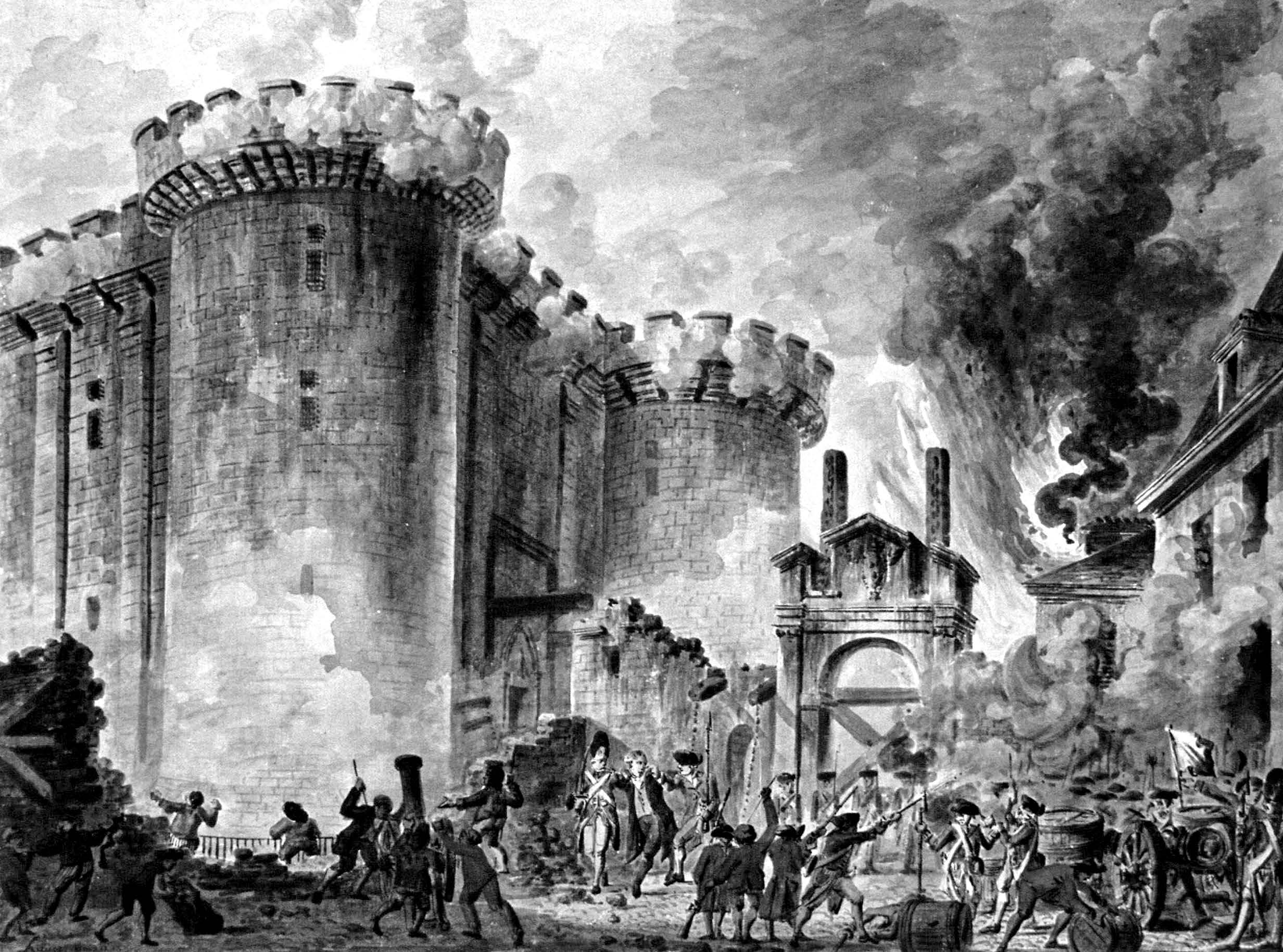

The complexities of the French Revolution may be simplified by dividing its history into four distinct phases: (1) the Bastille (1789), (2) the Reform (1789–91), (3) the Reign of Terror (1792–94), and (4) the Restoration (1794–99). When at last the Estates General convened at Versailles on 5 May 1789, the third estate’s elected deputies virtually abolished the other two estates and took on the title of National Assembly. Under Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau, their spirited leader, the commoners defied the king’s order to disband, and in the famous Tennis Court Oath on 20 June, they refused to dismiss until they had given France a constitution. Thereupon the king called in the army on 27 June to expel the stubborn deputies at the point of gun and bayonet. Instead of disseminating, however, the deputies held firm and on 9 July reconstituted themselves as the National Constituent Assembly. The assembly’ courageous action in the face of determined royal opposition inspired all of Paris to arise with indignation. Then on 14 July 1789, Parisians stormed the Bastille, a prison fortress in central Paris and a symbol of everything that was hated about the ancien régime. They overpowered and killed the guards and razed the Bastille. As if on cue, all across the country peasants rose up in arms against their feudal masters and seigneurs. They burned fields and chateaux indiscriminately in what came to be known as the “Great Fear.”[11]

The Storming of the Bastille, or Prise de la Bastille (1789), by Jean Pierre Houël.

The Storming of the Bastille, or Prise de la Bastille (1789), by Jean Pierre Houël.

Truly, the time for reform had given way to a fiery revolution that engulfed France as never seen before. Law and order fell victim to a pell-mell rush for liberty as the awesome, fearful power of the people rose up in anger, rushing everywhere. Men and women throughout the tired, old country were willing to countenance the destruction of an entire way of life in hopes of a new, if unpredictable, more equitable, more just, more egalitarian world. Napoléon and much of the army could only watch the fires light up the skies all over France.

Within a month of the storming of the Bastille, the National Constituent Assembly

convened in what might be called the Reform, or second phase of the Revolution. Painfully aware of the spirit of insurrection then engulfing France, the deputies moved swiftly in doing away with all forms of feudal society in what has been termed “the bonfire of privilege.”[12] In short order, the National Constituent Assembly abolished a plethora of hated tithes and taxes and ordered the nobility to pay its fair share. It then reorganized the country administratively by abolishing the old provinces and establishing a new, more efficient governmental structure, liberalized the terms of citizenship, mandated the popular election of local officials as well as justices of the peace, and abolished hereditable nobility altogether with its titles and symbols. No less sweeping and controversial, the National Constituent Assembly passed a law entitled the “Civil Constitution of the Clergy,” which nationalized the Roman Catholic Church by confiscating its vast, tax-free land holdings, abolishing its monastic orders, and mandating the election of its bishops and priests—in short, turning the clergy into employees of the state. Although there was still popular goodwill for the Crown, the National Constituent Assembly envisioned a constitutional monarchy with reduced powers and, looking to the US Declaration of Independence as a model, issued its famous Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen on 26 August 1789.

What triggered the violent third stage of the Revolution was the royal family’s opposition to the course of the uprising and its clumsy effort to escape the country in 1791. News of the king’s written renunciation of the aims of the Revolution and of the royal family’s subsequent failed defection, along with the Austrian-born Queen Marie-Antoinette’s treasonous correspondence with Austrian military forces, shook the nation to its core. Confidence in the monarchy plummeted everywhere. Captured in June of that year at Varennes just before crossing the border into the Netherlands, the royal family was arrested, paraded in disgrace, and promptly imprisoned without trial.[13]

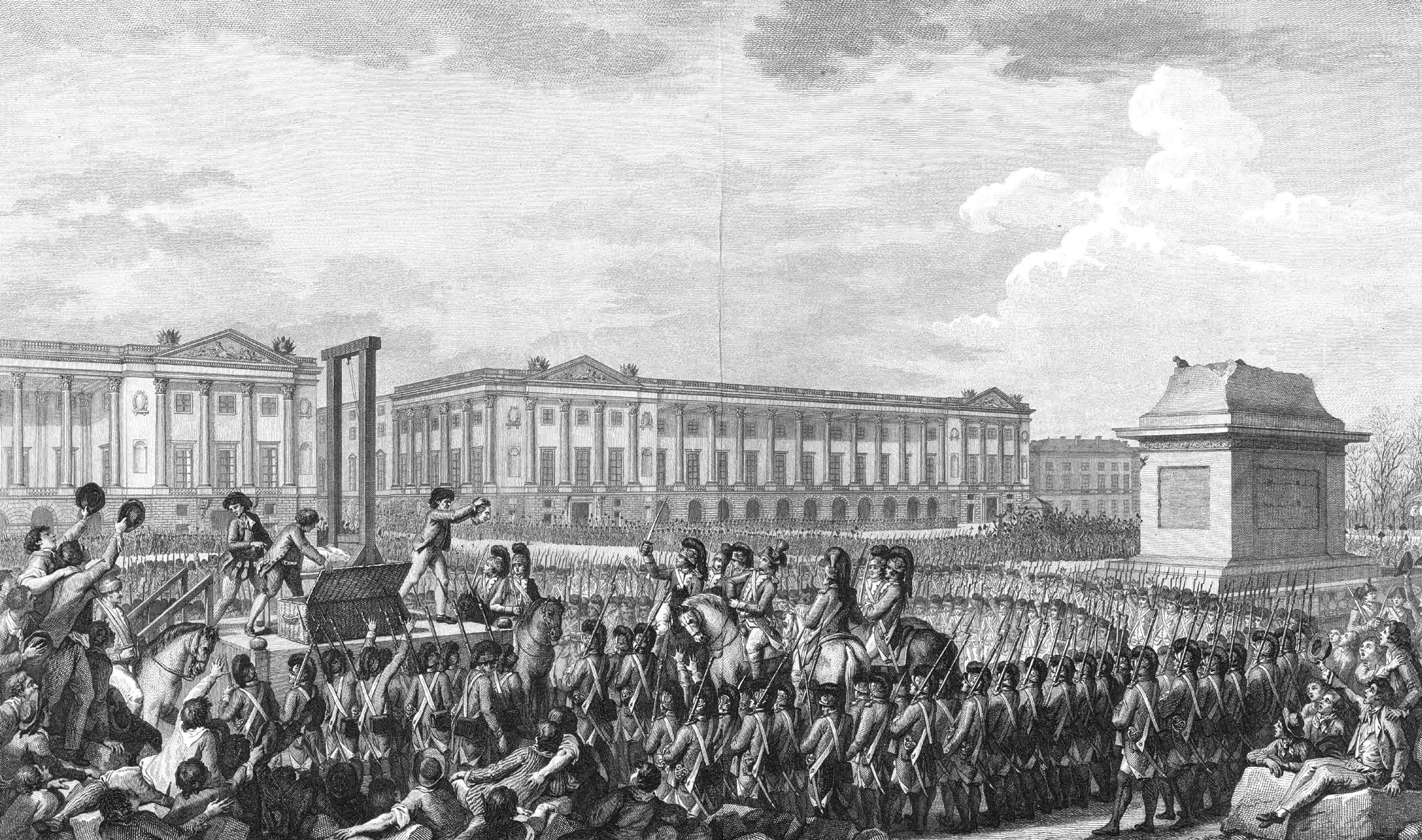

The Legislative Assembly then voted to suspend King Louis XVI from his royal functions and to call nationwide elections for yet another assembly that would determine the fate of the monarchy, thus in effect scrapping the constitution of 1791. In this newly elected National Convention, the Jacobins, or Parisian radicals—led by such puritanical moralists as Georges Danton, Maximilien Robespierre, and others—seized parliamentary control, abolished the monarchy and every symbol of it, and declared France a republic on 20 September 1792. Condemning the king and queen as traitors to France, the National Convention took the drastic action of executing King Louis “the Faithless” by guillotine on 21 January 1793, followed by the execution of his wife—the hated Marie-Antoinette—on 16 October, in the public square now more euphemistically known as the Place de la Concorde, thus hurling a ghastly challenge to European monarchists everywhere. Soon afterward, the Jacobins set up a new, powerful executive body ironically called the Committee of Public Safety, which unleashed the Reign of Terror by executing imprisoned noblemen, clergy, and others who were considered even slightly counterrevolutionary.

Execution of Louis XVI, by Isidore Stanislas Helman.

Execution of Louis XVI, by Isidore Stanislas Helman.

By 1793 the rebellion had become a veritable civil war waged with “unrelenting cruelty on both sides.”[14] The drastic methods used to put down the rebellion, “which included mass drownings of prisoners in the Loire River and the burning down of entire villages, together with the massacre of their inhabitants, were the bloodiest episodes of the revolution. The estimates suggest that the fighting in the Vendée may have claimed over 200,000 lives.”[15]

During the second year of the Reign of Terror, “perhaps half a million men and women saw the inside of a cell . . . and around 16,000 mounted the steps of the guillotine. Many more were killed during spectacular acts of collective repression” by both republicans and royalists.[16] Robespierre eventually gained total control over the blood bath that the Revolution was fast becoming, ordering the execution of hundreds of innocent citizens, Danton included.

One of the most bizarre acts of the Committee on Public Safety was its dechristianization campaign. Initiated by “revolutionary militants” in outlying areas, the movement blamed the Roman Catholic Church for abuses and subjugations of all kinds. More to the point, revolutionaries knew that more than half the parish clergymen in France had refused to swear a loyalty oath in the words specified by the National Constituent Assembly and believed that refractory priests, especially in western France, were plotting sedition and counterrevolutionary activities.[17] This may explain why they closed churches, defrocked priests, transformed church buildings into granaries, and even rechristened the venerable Notre Dame Cathedral a “Temple of Reason.”[18] Even the Christian calendar was abolished, and a new secular version was adopted in which Sundays were done away with and years were counted from the birth year of the new republic.[19] It seemed almost everyone was suspected of some treasonable act or another. Robespierre himself became a victim of his own excesses and was executed late in Thermidor year II (July 1794). Meanwhile, the Thermidorian Convention (made up of the legislators who had survived Robespierre) drafted the Constitution of 1795, aimed at preventing the rise of another dictatorial government.

Gradually, under such leaders as Abbé Sieyès, the French citizenry revolted against these excesses of the Reign of Terror. More moderate voices—the Girondists—prevailed and regained control of government, freed thousands of prisoners, reopened many of the churches, tore down the scaffolds of execution, renamed the Place de la Révolution (where the guillotine had once stood) the Place de la Concorde, and drafted yet another constitution calling for the executive power, now void of a king, to be vested in a Directory of five men elected by the legislature, renamed the Chamber of Five Hundred.

“The Whiff of Grapeshot”

With the resurgence of royalist influence in the Chamber of Five Hundred and the massing of Austrian and Prussian royalist armies to the east with the British fleet prowling the coastlines of France, the Directory felt threatened from within and without. When an army of twenty thousand royalist national guardsmen took control over much of Paris, the desperate Directory sought help from those in the military who were supportive of the spirit of the Revolution.

Ever the realist, Napoléon knew which way the political winds were blowing, although he was legitimately a supporter of the republican cause.[20] Promoted to the rank of captain in 1792, he had witnessed firsthand the near anarchy of the food riots in Paris, and he sympathized with the overthrow—though not the execution—of the king and queen. His regiment was called up in 1794 to help drive back a British force of eighteen thousand troops that had landed in Toulon, in southern France. As second in command in charge of hillside batteries, Napoléon successfully shelled the British fleet below before leading his men in fierce hand-to-hand combat, during which he suffered a bayonet stab to his left thigh, the only wound of his illustrious military career. Courageous and unflinching in battle, he harbored an almost fatalistic view toward death—“If your number is up, no point in worrying.”[21]

Napoléon’s valor and successful use of ballistics in the “mathematics of warfare” soon led to his promotion to brigadier general. Word of his prorepublican sympathies and military expertise quickly reached Paris, where the new Directory was contending against ever mounting opposition. Consequently, the Directory called on Napoléon to rush to the capital and put down the royalist uprising. Soon in command of his own troops in the streets of Paris, Napoléon employed “the whiff of grapeshot,” in which he fired both gun and cannon indiscriminately upon Parisians, successfully crushing the “rising of Vendémiaire.”[22] With the Parisian uprisings quashed, a desperate Directory immediately promoted Napoléon to general of the French forces in Italy, where enemy forces were massing for war.

On the Italian front, Napoléon’s brilliance and daring as a military commander began to shine. Though his forces were significantly outnumbered, Napoléon routed not one but three opposing Austrian and papal armies and earned the zealous admiration of his troops at the Bridge of Lodi, where his personal bravery earned him the title Le Petit Caporal (the dear corporal). In quick succession, Napoléon pushed southward, seizing Milan, Turin, Mantua, and other papal state cities and “liberating” most of Italy. Forced to capitulate, a stunned Austria soon surrendered both the Netherlands and the Milanese to the French forces.

When Napoléon returned in triumph to Paris in late 1797, he was lionized everywhere as savior of the Revolution and France, and he then very likely could have seized control of the faltering government, but cunningly chose not to do so. As one scholar put it, “he knew the pear was not ripe.”[23] When asked to seriously consider the advantages of attacking and crippling Great Britain, Napoléon deferred, respecting well the one true lifeline of Britain’s sure defense—its glorious navy. Rather, he turned his sights eastward to Egypt, from which he could mount an attack on Asiatic trade routes, thereby disrupting Britain’s lucrative cotton trade with India and the Far East. The date of his Mediterranean project was so closely guarded a secret that not even Napoléon’s fellow commanders knew of it until the very day of sailing on 19 May 1798. Successfully evading the British fleet and the watchful eye of Admiral Horatio Nelson, Napoléon commanded a force of thirteen ships, four hundred transports, an army of thirty-eight thousand men, and a corps of many of France’s leading scientists—“a complete encyclopédie vivante, equipped with libraries and instruments”—to further the cause of France, of modern science, and, of course, of Napoléon himself.[24] Though Nelson later destroyed the French fleet at Aboukir Bay at the Battle of the Nile, Napoléon, “who took to the desert as most men do who love the sea,”[25] easily conquered the Mamluks of Alexandria and Cairo and the Turks of Aboukir and likely would have overrun Syria had he been able to retain sufficient naval power.

Upon hearing that the French government was teetering and that the Directory was in jeopardy from yet another Austrian invasion, Napoléon decided to return to Paris, where he captured the hearts of a grateful, adoring nation that heralded his return once again as a conquering hero and the savior of France. At the request of the Directory, now more beholden to him than ever before, Napoléon dissolved the legislature in his famous coup d’état of 18 Brumaire (9 November) 1799. Now holding the full power of the military, he concentrated the executive power of the former Directory into a new three-man consulate or triumvirate with himself as the first, or most powerful, of the consuls. He may have saved the government, but he was a self-serving savior.[26]

Consolidator of the Revolution

In his meteoric rise to power, Napoléon ever regarded himself as “the consolidator of the Revolution,” or, as many called him, its “savior.”[27] Blessed with an extraordinary capacity for work, a prodigious memory, and an impressive grasp of the complexities of contemporary politics, Napoléon set out to preserve the ideals and gains of the Revolution. As important as his Concordat with the Roman Catholic Church in July 1801 was, in which many of the egregious policies of dechristianization were overturned, his most long-lasting, far-reaching accomplishment was the establishment of the Civil or Napoleonic Code of 1804, which “gave legal expression” and safeguards “to the social gains of the Revolution.”[28] These included the equality of all under the law, the sanctity of property and individual ownership, freedom of commerce and contract, freedom of career, and the strengthened place of family, particularly the authority of the husband and father. One can well argue that the Consulate, led by Napoléon, secured virtually all the gains of the Revolution—liberté, égalité, et fraternité.

Few people, however, seemed to have noticed or even cared that their conquering hero was moving France away from a democracy and toward a dictatorship of his own creation, or as one scholar has stated, “a dazzling embodiment of the enlightened despot in action.”[29] But once he had declared himself sole consul in 1802 and crowned himself emperor of France in December 1804 in the Cathedral of Notre Dame, few could anymore doubt that the French Revolution was over and that a new form of monarchy was now firmly in control.

Yet, for all the adoring crowds and the fierce loyalty of his troops, Napoléon was a lonely man. His very successes set him apart from many of his military and political colleagues, who feared or were jealous of him, and by others who began to revere him as something almost more than a man. Even his enemies were beginning to see in him as a figure the likes of which the world had not seen in a very long time. Had he married well, his wife may have been his best counselor. The fact was, however, that the first consul of France was suspicious of most women, certainly of women in authority.

Napoléon may have had affairs of his own, but he was not the kind of man to be distracted by sex. It was a hunger that never dominated him, although many women were attracted to him, or at least to his power, and would have been more than willing to be mistresses despite his foul language, quick temper, and dismissive style. His penetrating gaze, fine Corsican skin, and neatness in dress made for an impressive figure.[30]

The first woman he loved, at least from a distance, he could not have—his brother’s wife, Désirée. But he gave his heart in marriage in 1796 to Josephine, a widow six years his senior with two small children, whose husband had been earlier executed during the Revolution. She admired the way he loved her and also the way he rose in power, but she never fully loved him in return. She had one eye for expensive things and another for handsome young men. News of her torrid extramarital fling with Hippolyte Charles, a handsome, young officer and “accomplished womanizer,” made it all the way to Egypt and may well have been a factor in Napoléon’s abrupt return to Paris in 1799.[31] Although he captured the hearts of a grateful nation, he never could command Josephine’s deepest affections. Their marriage was at best one of tepid affection, bordering on distrust. When their marriage ended in divorce in 1809, with Josephine unable to bare a son, Napoléon married Marie-Louise, an immature, sixteen-year-old schoolgirl and daughter of the Austrian king, in what was a blatant political relationship of convenience. Although she bore him a son—Napoléon II—she was as unfaithful to Napoléon as Josephine had been, choosing to love a much younger man.

Josephine Bonaparte. Joséphine de Beauharnais vers 1809, by Antoine-Jean Gros.

Josephine Bonaparte. Joséphine de Beauharnais vers 1809, by Antoine-Jean Gros.

Thus, even in the matrimonial bed, France’s favorite son was a lonely figure. The women and men who might have mellowed him were unable, unwilling, and incapable of doing so. And Letizia, his mother, could not dictate to him. The fact is he was too proud for love, “except perhaps, a little, with Josephine,” too contemptuous of both men and women, and too involved with the affairs of state rather than with personal relationships.[32]

“Vive L’Empereur” (1800–1811)

It was on the blood-soaked battlefields of Europe where Napoléon, “the God of Modern War,” won the begrudging respect of his enemies and the unending admiration of history.[33] One of his most critical biographers admitted: “[One] cannot refuse to acknowledge that no man ever comprehended more clearly the splendid science of war; [one] cannot fail to bow to the genius which conceived and executed the Italian campaign, which fought the classic battles of Austerlitz, Jena and Wagram. These deeds are great epics. They move in noble, measured lines and stir us by their might and perfection. It is only a genius of the most magnificent order which could handle men and materials as Napoleon did.”[34]

What accounts for his successes? One key factor was his early mastering of the element of surprise. Abrupt and impatient to a fault and almost carelessly decisive, he could hardly ever be second-guessed. When Austria redeclared war on France in 1800, he did the unthinkable by marching his army, Carthaginian-like, across the snow-packed Swiss Alps into northern Italy, shocking his enemies by attacking them from the rear. His victory at the Battle of Marengo near Turin was subsequently a most resounding one.

After the collapse of the Peace of Amiens (1802), the British determined to crush Napoléon by bankrolling the armies of Austria and Russia in the so-called Third Coalition against France. In response, Napoléon once more seriously considered invading England, this time at the head of a Grande Armée of 120,000 battle-hardened veterans. Had not Nelson, by this time a mighty legend in his own right, shattered the combined French and Spanish fleet at Trafalgar off the coast of Spain in October 1805 in one of the most brilliant naval victories of all time, Napoléon may well have crossed over the English Channel.

Pretending to ignore the British victory, Napoléon, within weeks of Trafalgar, performed a no less memorable victory on land, not once but twice. First against superior numbers, he launched a daring surprise attack and defeated General Mack and the Austrian armies at Ulm in late October, and thereafter he marched into Vienna without a fight. Next, he routed the Russian armies at Austerlitz in early December 1805. By the end of 1806, Napoléon occupied Berlin.

His stunning victories at Ulm and Austerlitz underscore another reason for his success: Napoléon was a master strategist. His “consummate skill,” remarked one astute observer, “was . . . in estimating and combining time, distance, and number; in calculating the movements of great armies; . . . with a promptitude that was quite surprising. A single glance through his telescope in the midst of smoke and confusion, gave him instantly the actual state of affairs, at moments of greatest danger.”[35] Napoléon, albeit a risk-taker, left little to chance. He planned for victory. In his mind, a campaign was faulty “unless it anticipated everything that the enemy might do and provided the means of outmaneuvering him.”[36]

A third factor for success was that he acted courageously and lightning fast. “My troops have moved as rapidly as my thoughts,”[37] he once declared. He was at his best when outnumbered for he knew well how to divide and conquer. His habit was to spread out his forces when marching, then quickly concentrate them into attacking relentlessly with splendid cavalry rushes and incredibly accurate artillery fire on one column and flank of the enemy, then turning with full force on another.[38] Even at night, by the light of torch fire, Napoléon’s field headquarters always featured a large table with a large map of the theatre of war spread out upon it with troop positions marked with different colored pens. From there, Napoléon, who seldom slept, would redeploy, amass his forces on another front, and, come the dawn, take full advantage of the situation, surprising his enemy. The elements of speed, surprise, careful strategy, and flexibility, along with his superb use of the cavalry and his deadly use of artillery consistently frustrated and overwhelmed his opposing forces. Indeed, he once said, “It is with artillery that war is made.”[39]

The Battle of Austerlitz, 2nd December 1805, by François Gérard.

The Battle of Austerlitz, 2nd December 1805, by François Gérard.

Napoléon was more than a brilliant tactical strategist. He brought a degree of passion, emotion, and enthusiasm to the front that his men had seldom, if ever, seen before. As one American journalist wrote, “We have never heard of a general who possessed the love and confidence of his soldiers like Bonaparte. . . . Without the love of his army he could have done nothing—with it, everything.”[40] As much a father figure as a commander, Napoléon loved his men, and in return many gave their lives for him. Endowed with an incredible memory, he could call many of even the lowest ranking officers by name. Many a time he would scratch out written notes of commendation and affection for those showing true gallantry in battle, and in his famous bulletins, Napoléon reported on their bravery for all the world to read. He constantly rewarded them with advancement or with the Legion of Honour. He ensured their widows were given lifetime pensions; his successful marshals were promised duchies; and surviving children were given the right to use his name.[41]

Napoléon was not immune to the sufferings, brutality, and horrors of war. He wrote in a letter to Josephine, “One suffers and the soul is oppressed to see so many victims.”[42] He nevertheless viewed human life as the necessary currency for victory. “A man such as I am does not concern himself much about the lives of a million men,” he once remarked.[43] He was ruthless and “did not economize the lives of his men.”[44]

Napoléon’s very presence was incredibly motivational to his forces. A man of raw courage and indomitable will, Napoléon was always in the forefront of his armies. Wellington once said of him, “His presence on the field made a difference of 40,000 men.”[45] Consider the following description of the French victory at Austerlitz:

The Emperor, surrounded by all the marshals, wanted only for the horizon to clear to issue his last orders. At the first rays of the sun, the orders were issued and each marshal rejoined his corps at full gallop. The Emperor said, in passing along the front of several regiments, “Soldiers, we must finish this campaign by a thunderbolt that shall confound the pride of our enemies,” and instantly hats were placed at the point of bayonets, and cries of “Long live the Emperor” were the true signal of battle. A moment afterwards, the cannonade began . . . and the battle was engaged.[46]

In this, undeniably one of Napoleon’s greatest victories, the Russian-Austrian forces suffered thirty thousand fatalities and an equal number of prisoners, compared to a French loss of only fifteen hundred.

Ever the willing improviser, Napoléon also streamlined his forces into smaller combat units or corps of twenty to thirty thousand men led by field marshals who were given surprising autonomy and freedom of action. Each corps was subdivided into four or five divisions, each division equipped with regiments and battalions, cavalry brigades, infantry, and even medical and service units, the latter of which implemented “ambulances,” light carriages that removed the wounded and dying quickly from the battle. Napoleon’s organization of the Imperial Guard, made up the finest soldiers in the army, created a genuine sense of honor and mystique, a true fighting elite.[47]

Of course, as emperor and supreme head of state, Napoléon had the advantage of calling upon the full financial powers of France and of several conquered nations to support his military exploits. One reason for his selling the Louisiana Purchase to the Americans in 1803 was to raise funds to support his military conquests. He was also able to draft conscripts into his Grande Armée from conquered nations.

In 1806, a Fourth Coalition made up of England, Russia, Austria, and Prussia had formed with England once again, providing the necessary financial backing. But at the battles of Jena and Auerstadt in October 1806 and again at Elyan in 1807, Napoléon once again proved successful. Suing for peace at almost any cost, the Russian tsar Alexander I, who hated the English almost as much as Napoléon did and who wanted to keep Prussia and Austria at bay, met with the French emperor on a raft on the Niemen River (see chapter 3). In the famous Treaty of Tilsit (1807), Alexander I agreed to participate in Napoléon’s continental blockade, aimed at closing all European and Asian ports to British trade, thereby forcing England to its knees.[48] The entire continent was now more or less under Napoléon’s command. At this, arguably the apex of Napoléon’s military fortunes, friends and foes alike were hailing Napoléon as “above human history,” declaring, “He belongs to the heroic age.”[49]

Portugal’s refusal, however, to join in the blockade and its decision to allow British expeditionary forces under Arthur Wellesley (Lord Wellington) to reenter Europe in 1809, was the beginning of the bloody Peninsular War, which proved a quagmire for French forces: a constant drain and distraction to Napoléon’s eastern European campaigns. The savage fighting in Portugal and Spain—characterized by anti-French guerilla warfare, widespread pillaging and banditry on both sides, bloody city sieges (like that at Saragossa), and wholesale massacres—absorbed the attention of many hundreds of thousands of French troops, although Napoléon himself never bothered to involve himself personally in the eroding conflict.

Sensing its chance, Austria once again declared war on France only to be decisively defeated again at the battle of Wagram in July 1809. In this one battle, 200,000 French soldiers, with Napoléon galloping along the frontline on a white charger, faced an even larger enemy army. Napoléon’s twenty-fifth bulletin, though slanted in his favor, provides us with a sense of the terror of that scene.

Such is the narrative of the battle of Wagram, a battle decisive and ever memorable, in which from 300,000 to 400,000 men, and from 1,200 to 1,500 pieces of artillery, contended for great interest, upon a battlefield, studied, planned and fortified by the enemy for several months. Ten pairs of colours, 40 cannon, 20,000 prisoners, including between 300 and 400 officers, and a considerable number of generals, colonels, and majors are the trophies of this victory. The battlefields are covered with the slain, among whom are the bodies of several generals, and among others, Norman, a Frenchman, traitor to his country, who prostituted his talents against her.[50]

Napoléon lost twenty-seven thousand men and Austria lost twenty-five thousand, but in the end Austria was routed and Archduke Ferdinand sued for peace.

As a teenage cadet back in Brienne, Napoléon had once built so dazzling a fortification of ice and snow, from which he launched magnificent snowball attacks against his fellow cadets, that many local townspeople came out to see it—all in good fun and humor.[51] But there would be nothing fun or kind about the ice, snow, famine, and suffering of the Russian winter of 1812 that ultimately destroyed la gloire de la France. Napoléon’s tragic defeat, less at the hands of opposing Russian armies and more from the icy grip of a Russian winter, has gone down in history as one of the greatest military tragedies of all time. Yet even his losses, on so vast a scale, have magnified his legend and made of it an epic drama about which grand symphonies and great novels have been written.

“My Army Has Had Some Losses”: The Russian Campaign of 1812

Where once upon a time they had been uneasy allies (Napoléon had even tried to marry Alexander’s sister at one time), the two emperors, Napoléon and Tsar Alexander I, had become enemies for at least two reasons: first, Napoléon’s desire to extend French imperialism over the Polish territories and into the Baltics; and second, the economic devastation wrought upon Russian trade because of the continental blockade. To these must be added another: Napoléon’s overreaching and, by now, unbridled ambition. Never were his military powers so great and never was he so close to bankrupting Great Britain. This was his moment, despite festering problems in Spain, to seize total control of virtually all of Europe. Confident of victory, Napoléon declared war on Russia.

“Since the days of Xerxes no invasion of war had been prepared on so gigantic a scale.”[52] Napoléon’s Grande Armée of over 610,000 men (made up of French, Swiss, Italian, Polish, Prussian, Austrian, and Bavarian soldiers), 182,000 horses, 1,300 cannons, and 20,000 commissary wagons began crossing the Niemen River at Kovno on 24 June 1812, marching eastward in three parallel columns, an invading force not seen since ancient times. Its purpose was to divide and defeat the two defending Russian armies that Alexander had earlier deployed to Russia’s western front. Instead of engaging the enemy, Napoléon kept looking for it, like a shadow boxer, swinging every which way but seldom making contact. While some have argued that the Russian retreat was a clever, calculated strategy designed to entrap the invaders deep inside Russian territory, more likely the Russian commanders feared to confront, at least too early in the campaign, so vast and formidable a foe.[53] Whatever the real Russian strategy, it frustrated Napoléon’s desire to end the conflict quickly and drew him ever further east into the Russian vortex in his chase of an elusive victory.

And the further eastward they marched, the more apparent became their problems. As we have already seen, Napoléon was at his best when outnumbered and with smaller, not larger and unwieldy, armies. Communication between such a polyglot, cosmopolitan, and multilingual army proved ever problematic. And the further east the army marched, the longer the necessary supply lines stretched behind and the more difficult it became to maintain and protect them. Bad roads, insufficient harvests, lengthy forced marches, and Russia’s scorched-earth tactics all contributed to a rapidly worsening situation.

Fire of Moscow (1812), by Viktor Mazurovsky

Fire of Moscow (1812), by Viktor Mazurovsky

When Napoléon finally decided to march on Moscow, the combined Russian armies made their long-awaited stand at Borodino in September 1812, near St. Petersburg, where between five and six hundred thousand men fought for more than fifteen hours within the space of a square league. The losses were staggering on both sides: forty-four thousand Russian soldiers and thirty-three thousand French Imperial Forces soldiers were killed or wounded. The dead were piled up six to eight men deep in spots. It was, Napoléon considered, “the most terrible battle he had ever fought.” [54]

Borodino proved a Pyrrhic victory for Napoléon’s forces because the Russians adroitly retreated, preventing the rout Napoléon had needed. Weakened, frustrated, and without the knockout blow necessary to claim victory, Napoléon, with one hundred thousand men, at long last entered a deserted, nearly burned-out, Moscow on 15 September. Hoping to have defeated Russia by this time, Napoléon had barely gained the capital, and with Alexander refusing to negotiate or surrender, Napoléon could hardly claim victory. Surprisingly, the evacuating Russian forces had forgotten to destroy warehouses of grain and fodder that were enough to feed the entire French army for six months. Had Napoléon chosen to winter at the capital until the spring, he may well have won the war. However, he was uneasy being so far removed from his Polish bases, worried that news of the war was not going over well back in Paris, and concerned that Russia would strengthen its forces over the winter. Finally, in a pique of rage over Alexander’s steadfast resolve not to surrender, Napoléon quit the city late in October and began his inglorious return march to France.

“Now we shall make war in earnest,” Tsar Alexander reportedly declared. Thousands of infuriated Russian peasants, feigning food and friendship, butchered the retreating French soldiers with knives and pitchforks. Vicious Cossack attacks eliminated advance parties and sentinels while the Russian armies harassed the rear of the French columns. Then on came the Russian winter and with it famine and disease. Self-preservation became the only motive. Unheard-of calamities began thinning the ranks of a proud army now staggering like a wounded blind man.

The winter was so severe, with nighttime temperatures as low as -25°F, that desperate soldiers, often with their hands, feet, ears, and noses entirely frozen, “burnt whole houses to avoid being frozen [to death]. We saw around the fires, the half-consumed bodies of many unfortunate men, who having advanced too near in order to warm themselves, and being too weak to recede, had become a prey to the flames. Some miserable beings, blackened with smoke, and besmeared with the blood of the horses which they had devoured, wandered like ghosts around the burning houses.”[55] Panic replaced discipline, and chaos reigned in a frightful, cannibalistic effort to stay alive.

The French crossing of the Beresina River, with its burned-out bridges and ice-cold water temperatures, was but one of many heroic yet tragic stories of the weary march west. Had the Russians been able to pin down Napoléon on its eastern banks, he likely would have been captured. However, the French were able to decoy away and delay their pursuers long enough for some four hundred geographical engineers to wade into the icy river waters and construct a makeshift bridge strong enough to support the retreating army. Almost to a man, the engineers died of exhaustion and exposure.[56]

Impatient and fearful of an attempted plot against him, Napoléon, as he did in Egypt, went ahead to Paris to retain his weakening grip on power, secure help for his men, and raise new armies, for of the 610,000 men who had marched with him to Russia, only 40,000 returned! A wounded Napoléon would muster enough new recruits to fight on, winning several major battles, but the French reversals against Wellington in Spain and the realignment of Russia, Austria, Prussia, and England against him spelled the end of Napoléon’s imperial France. “As he returned across the Rhine to Paris, Napoléon found himself an Emperor without an Empire.”[57] Weary of war, French forces continually retreated until the victorious allied armies marched into Paris on 31 March 1814.

The subsequent Congress of Vienna (see chapter 3) strove to achieve a lasting peace in the Treaty of Fontainebleau, carved up much of Napoléon’s European victories, and banished Napoléon to the island of Elba in the Mediterranean Sea in April 1814, ironically not far from Corsica. The world, so everyone surmised, could finally move forward.

“Here Am I”: The One Hundred Days

Reduced to “Emperor and Sovereign of the Isle of Elba”—a small island twelve by eighteen miles with a population of only twelve thousand—Napoléon spent his days gardening and his nights plotting a return. He knew that the restored Bourbon monarchy was not playing well in France, and incredibly, despite spies covering the island, Napoléon quietly slipped away with seven ships and 1,150 men, landing in France on 1 March 1815. His destination, Paris. His design, France!

While marching northward, the great testing moment came near Grenoble when he encountered a royal regiment of French grenadiers who had been ordered to shoot him on sight. At that moment, wearing his famous gray coat and three-pointed hat, Napoléon walked out alone in front of the royalist troops, threw open his coat and shouted: “Soldiers of the Fifth of the Line, do you remember me? . . . If there is in your ranks a single soldier who would kill his Emperor, let him fire. Here am I.”[58] A deafening silence followed. Instead of a volley there arose a tremendous shout of “Vive l’Empereur!” And he was instantly mobbed with veneration by men still willing to sacrifice their all for him. Playing the stirring strains of “La Marseillaise,” the anthem of the Revolution, Napoléon’s ever-growing army marched northward. On 19 March, one day after the puppet king Louis XVIII had hurried out of town, Napoléon returned once more in triumph to a Paris wild with jubilation.

Stunned by the incredible news of the vanquished’s resurrection, the Austrian prime minister Klemens von Metternich and the Congress of Vienna, which he supervised, moved promptly to counter the revived threat. England, Prussia, Russia, and Austria each pledged to send an army of 150,000 men against Napoléon—600,000 men in aggregate, called the Armies of the seventh Coalition—all under the command of Wellington, the “Iron Duke.” Napoléon knew that his only chance of success was to go on the offensive and, by once again employing the element of surprise, attack and destroy in sequence first the British and then the Prussian armies that were then massing under Wellington’s command. He would then move on to Brussels before the advancing Russians and Austrians could join the fray. With incredible dispatch, he soon amassed a new army—L’Armée du Nord—to spearhead the assault against the advancing allied armies.

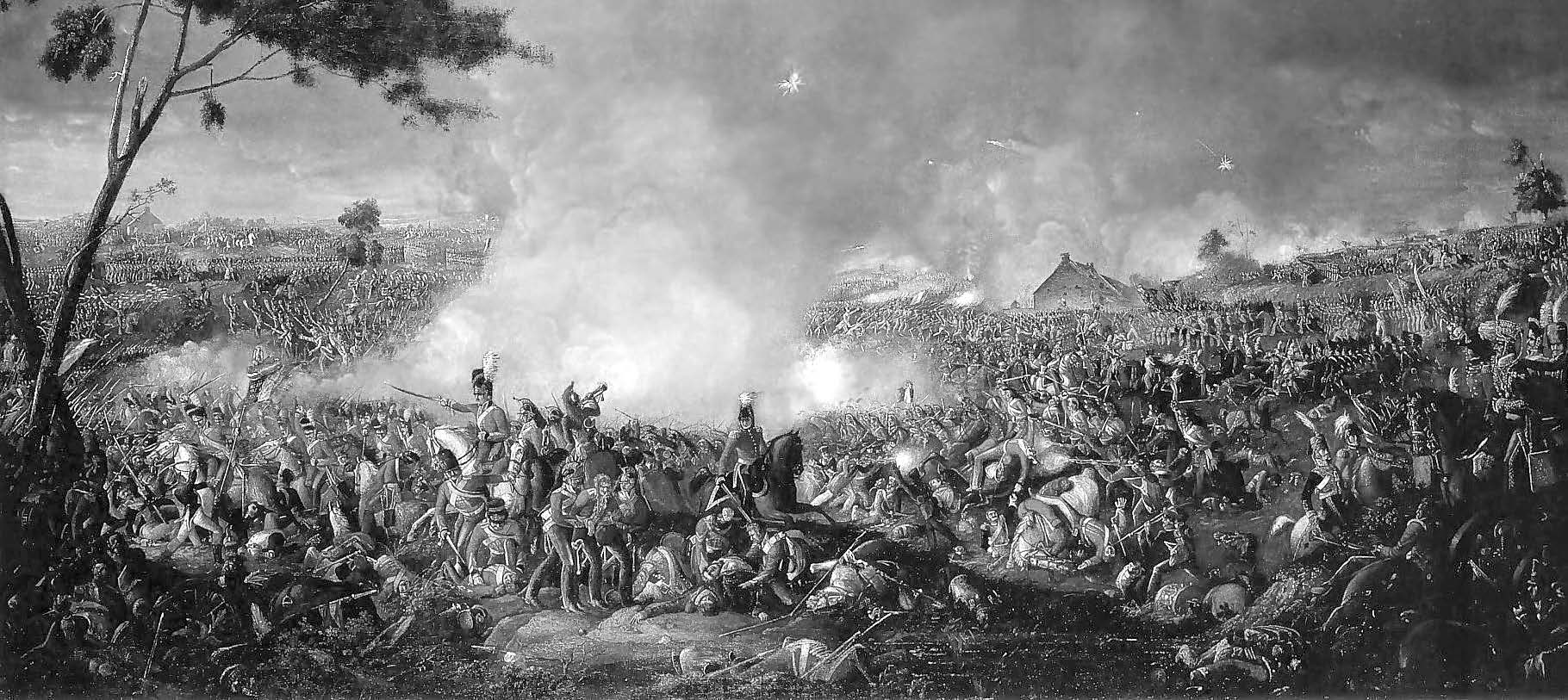

After four days of preliminary skirmishes and heated battles at Quatre Bras in Ligny, in which the French won Pyrrhic victories, Sunday, 18 June 1815, broke bright and beautiful over the Belgian fields near the tiny village of Waterloo, not far from Brussels. Waiting impatiently for the ground to dry sufficiently after days of heavy rain, the overly confident Napoléon once more heard the stirring strains of “La Marseillaise” waft across the tender wheat fields as one hundred thousand French soldiers, dressed in parade uniforms resplendent as the rising sun shouted,“Vive l’Empereur.” Less than a mile away, Wellington stood restless yet resolute, poised at the head of a British-Dutch-Belgian, multinational, multilingual army of 93,000, cautiously optimistic that his battle-tested regulars, with the expectant arrival of General Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher and his Prussian army of over 120,000 men would withstand the imminent French onslaught. All sensed it would be a day of days, balanced between an unforgettable past and an unforgiving future.

At about 11:30 a.m. Napoléon’s artillery began its fearful, incessant bombardment of Wellington’s forces, stretched across a three-and-a-half-mile front. The cannonading from both sides tore down whole rows of advancing columns in fighting that was “so terrible as to strike with awe the oldest veteran on the field.”[59] Yet even with this, Wellington knew he could be cut from the field only by Napoléon’s cavalry and infantry charges. Surprisingly unsupported by French artillery—a critical error on Napoléon’s part—the French cavalry was swept down by Wellington’s blisteringly effective counterattacks. Then, at the Iron Duke’s famous command, “Up, guards, at them,” the allied forces went on the offensive.

The Battle of Waterloo, by William Sadler.

The Battle of Waterloo, by William Sadler.

As well as Wellington fought (Napoléon later said of him, “Wellington is a man of great firmness” [60] ) and as disciplined as the British foot soldiers were in repelling one wave of Field Marshal Ney’s French cavalry after another, what turned the tide that fateful day was Field Marshal Grouchy’s tardiness and failure to join in with Napoléon, combined with the sudden, unexpected appearance on the battle field of the determined Prussian columns. When Napoléon heard of it, he said to Ney, “On a perdu la France” (We lost France). Wellington then “rode to the crest of the position, took off his hat, and waved it in the air. Forty thousand men came pouring down the slopes in the twilight, the drums beat, and the trumpets sounded the charge.”[61] Panic spread like wildfire. By evening, with the dreaded words La Garde recule (The Guard retreats), the French were routed, and Napoléon barely escaped to Paris.

Back in Paris, General Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, rose in the chambers to distance France once and for all from Napoléon: “Three million Frenchmen have perished for one man who still wishes to fight the combined powers of Europe. We have done enough for Napoleon; let us now try to save France.”[62]

“How I Am Fallen”[63]

Fearing arrest from his own government, Napoléon calibrated his best chances of survival. On the 22 June 1815, the restored French royalist government gave Napoléon a single hour to abdicate before Louis XVIII’s imminent arrival in Paris. General Blücher announced “that he would have Napoleon shot at the head of his columns,” rather than be captured by the advancing Prussian armies, who entered Paris on 7 July. Napoléon then fled westward for the coast, where he spent a fortnight in hiding, mulling over his next move.[64] Surrender to King Louis XVIII? Flee to the United States? Sail to South America? Finally, on 15 July, knowing the effectiveness of the British naval blockade, he decided to test the good graces of the British government by surrendering himself up to his majesty’s ship Bellerophon in hopes of securing passage to the United States of America. “I have come to throw myself on the protection of your Prince and your laws,” he said to the ship’s startled commander, Captain Frederick Maitland.[65] Maitland and his crew, as surprised as anyone at this unexpected turn of events, accepted Napoléon as their worthy prisoner, treated him as a royal personage, gave him and his aides Maitland’s private quarters, and immediately set sail for England. The Bellerophon anchored in Plymouth harbor for almost two weeks while London wrestled with the question of what to do with the captured emperor.

The news out of London, however, was anything but cheery. Fearing another French uprising if they returned Napoléon to France, yet anxious to banish him far away from England, Prime Minister Lord Liverpool ordered him exiled to the destitute volcanic island of St. Helena, a British East India Company refueling station located in the South Atlantic Ocean five thousand miles away from France and much further away than Elba. Napoléon and his small company of aides were transferred to another warship, the HMS Northumberland, and they arrived on the island seventy days later on 17 October 1815 to a small, curious, and admiring crowd.

There at St. Helena for the next six years, General Napoléon (as his captors insisted on calling him) took up forced residence in a small, unpretentious, rather uncomfortable wooden house called Longwood, located on a high table of land looking out over the broad expanse of limitless ocean. Across a deep ravine in the front of the house encamped the British 53rd Regiment, whose twice-daily cannon firings announced day break and sunset. In all, some twenty-five hundred British soldiers encamped on the small island, with two ships constantly patrolling the island’s ragged coast lines to ensure against any repeat of what had happened on Elba.

Napoleon in St Helena, by Franz Josef Sandmann, c. 1820.

Napoleon in St Helena, by Franz Josef Sandmann, c. 1820.

Napoléon, longing for his son and hoping that, with a change in governments, London might change its mind, devoured every newspaper and every bit of letter-borne news and rumors. Determined to make the best of a bad situation, he began dictating his memoirs to Las Cases, one of his personal secretaries, from journals he had kept during his many campaigns. He was determined to make sure his interpretation of his life would outlast him. Consciously playing what one scholar has called their little game of “make believe,”[66] he resigned himself to commanding his little, adoring household while sparring with his British overseers with all the enthusiasm of a royal magistrate. Le Petit Caporal was as much the abrupt and domineering dictator in his island prison as he had ever been in battle or in his Parisian palaces, and his aides would have it no other way.

At the advice of his personal surgeon, Napoléon rekindled his lifelong Corsican interest in gardening and soon put all his household to work planting scores of peach trees, willows, oaks, and vegetables of every kind. He put in water fountains, a fishpond, and an arbor-covered pavilion. Rising before daybreak and dressed in a jacket, large trousers, an enormous straw hat, and sandals, he would “rush outside to plant new seeds, to water the roses and the strawberries, to arrange for trees and bushes to be moved like furniture from one place to another until the correct symmetry had been achieved” in the arboretum of his new empire.[67]

By 1818 his health began to fail. Seriously overweight and feeling the effects of the damp and incessant wind, Napoléon complained of what he termed a “knife turning inside his belly”[68] and around his liver. At the request of his mother, two Catholic priests were permitted to land on the island in September 1819, and, with Napoléon’s permission, they transformed Longwood’s sparsely furnished dining room into a chapel, where they celebrated mass every Sunday. On those days when their bedridden parishioner was too ill to move, he listened to the service through the open door of his bedroom.

While it is true that in his declining days Napoléon reverted to the Roman Catholic faith of his youth—“I believe in God; I am of the religion of my fathers,” he allegedly once declared[69]—he was a man of fate more than faith and was deeply pessimistic about life after death. If not an atheist, he believed Christianity was fundamentally a “man-made edifice.”[70]

Throughout the year 1820, his health steadily declined, though on occasion he strolled through his garden and even rode around the island. Toward the end of the year, he was walking with increasing difficulty and needed help even to reach a chair in the garden. Meanwhile Sir Hudson Lowe, the island’s new governor, court-martialed Napoléon’s surgeon for being too kind. As Napoléon’s legs swelled and his appetite waned, the rounds of nausea and sweats increased. He grew increasingly depressed and morose. “How I am fallen!” Napoléon said, “I, whose activity was boundless, whose mind never slumbered, am now plunged into a lethargic stupor, so that it requires effort even to raise my eyelids. I sometimes dictated to four or five secretaries, who wrote as fast as words could be uttered, but then I was NAPOLEON—now I am no longer anything. My strength, my faculties forsake me. I do not live—I merely exist.”[71]

The year 1820 was the period of his steepest decline. His last airing came on 17 March 1821. He dictated his last will and testament in which he expressed the wish that “his ashes should repose on the banks of the Seine, in the midst of the French people whom he had loved so well.” In the early evening of Saturday, 5 May, while a tremendous storm thundered by overhead and after receiving communion and extreme unction, he spoke his last: “France, armée, tete d’armée, Josephine” (France, army, head of the army, Josephine)[72] Though debate continues to swirl to this day over the precise cause of his death, Napoléon almost certainly succumbed to the same malady that took the life of his father and two of his sisters—a painful cancer of the lower stomach.[73]

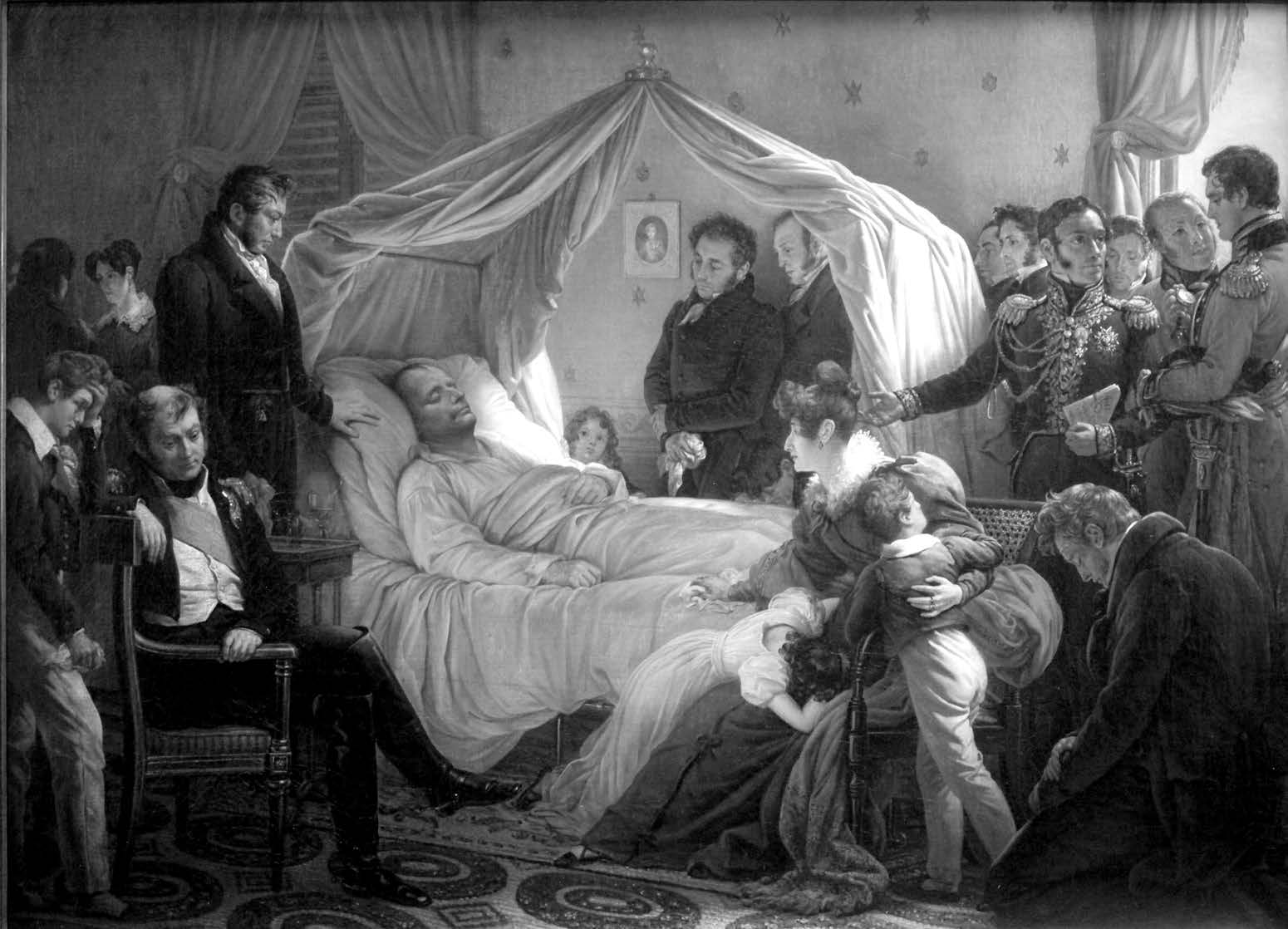

Death of Napoléon, by Charles de Steuben.

Death of Napoléon, by Charles de Steuben.

While Napoleon lay in state in his little bedroom, draped in black cloth, at Longwood, virtually the entire island population filed by his body, which was dressed in the green uniform of the Chasseurs of the Guard with the grand cordon of the Legion of Honour across his breast, long boots with spurs, and three-cornered hat. Many a British soldier bent the knee and kissed the corner of his cloak. At his funeral on 8 May, his last adversary, Governor Lowe, ordered full military honors and British soldiers bore him to his grave in Rupert Valley while the guns of the Royal Navy, his lifelong enemy, boomed their final salute.[74] The day was beautiful and clear, the islanders crowded the roads, and music resounded from the heights. “Never had a spectacle so sad and solemn been witnessed in these remote regions.”[75] His grave was marked by stone with only the words “here lies” engraved thereon, “because the French and the English could not agree on the inscription.”[76] Nineteen years later, his body was exhumed and moved to Paris, where a magnificent funeral was held in December 1840. Today he lies encased in marble and enshrined in glory as “the greatest soldier who ever lived”[77] in the historic military hospital of Les Invalides on the banks of the Seine, as he wished.

Not a Personality but a Principle

So what are we to make of this “Ogre from Corsica” (as his enemies called him), this spirit of the age, after a mere chapter of review? Appraisals by some of the world’s leading historians are continually changing and defy a simple consensus. Napoléon still refuses to be captured and defined. As Ida Tarbell has written: “No man ever did more drudgery, ever followed details more slavishly, yet who ever dared so divinely, ever played such hazardous games of chance. . . . No man ever made practical realities of so many of liberty’s dreams, yet it was by despotism that he gave liberal and beneficent laws. . . . He was valorous as a god in danger. . . . He was the greatest genius of his time.” Yet this same writer could only lament that he lacked “the crown of greatness, that high wisdom born of reflection and integration which knows its own powers and limitations.”[78]

Surely he will be continually criticized, if not despised, by many who regard him as nothing less than a dictator in republican clothing, a despot, a tyrant, and even a criminal whose bloody conquests and violent, rapacious conduct created unfathomable suffering on an unbelievable scale and spawned universal hatred and decades of resentment throughout much of Europe. The human toll of his exploits cost the flower of a generation on all sides—an estimated 1.4 million men killed in battle and another 1.6 million wounded or disfigured. He was a man of war and those who love and promote peace are effusive in their negative estimation of him. They choose to see him as but another dictator on par with such notorious totalitarian rulers as Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, and Mao Zedong. These critics brush aside any of his accomplishments, believing they are meaningless and irrelevant. As the British historian Paul Johnson has said: “The great evils of Bonapartism—the deification of force and war, the all-powerful centralized state, the use of cultural propaganda to apotheosize the autocrat, the marshaling of entire peoples in the pursuit of personal and ideological power—came to hateful maturity only in the twentieth century, which will go down in history as the Age of Infamy. It is well to remember the truth about the man whose example gave rise to it all, to strip away the myth and reveal the reality.”[79]

His detractors likewise despise his use of self-promotion, his relentless propaganda machine, his ill treatment of women, and his disregard for the environment. They loathe him for his self-aggrandizement and for fostering the myth that he was a superior being. Even many of his contemporaries, like Alexis de Tocqueville, charged him with being “a political domination unparalleled in modern history.”[80] To them, his empire “was in many respects a personal act of vanity.”[81] At base he remains for many not a reformer but a cruel, egotistical conqueror and megalomaniac whose tragic human flaw was that he did it all for the glory of self. And because of this “overweening ambition and ego, Napoléon was as much the cause of the wars of 1796–1815 as were the forces unleashed by the French Revolution.”[82] At best, his detractors see him as a “tragic hero,” one who failed his moment and the test of time for not being all he could have been.

Yet, for all this, the sun is beginning to shine once more on Napoléon, not merely for what he did for France but for Europe and the world. Wellington, his worthy adversary, was probably right when he once said of him: “Napoleon was not a personality, but a principle.”[83] To his lasting credit, Napoléon consolidated, institutionalized, and disseminated the hard-fought gains of the French Revolution. That he did so in a self-aggrandizing fashion and by military conquests that spilled the blood of millions cannot be denied. But the French Revolution, imperfect in its aims and ofttime horrific in its methods, was the bloody, long-coming statement of the common man and woman that the abuses of aristocratic privilege, absolutist royal power, and ecclesiastical paternalism could no longer be tolerated. Inspired in part by the American Revolution, the French Revolution had an even greater effect, throwing off a millennium of European feudalism and cruel domination. Against overwhelming odds and long-established inertia, it won a new world of freedom, equality, and justice. Had the European monarchies and class systems succeeded in preserving their ancien régime, their old, tired ways of doing things, more horrific wars with more terrible weapons would inevitably have been later fought. The French Revolution was inevitable, although its gains may not have been defensible or endurable without a Napoléon to buy a generation of time to let such freedoms take root and survive.[84]

Arguably, Napoléon’s greatest reform, at least that closest to the soul of the Revolution, was the establishment of the Napoleonic Code, a code of civil law. Enshrining the spirit of liberté, égalité, and fraternité, his new system of laws proclaimed legal equality, abolished serfdom, established fairer justice and taxation for all, gave new rights to home and family, and guaranteed property rights and the right to choose a career independent of status or rank. He upheld the legal institution of marriage and restricted divorce.

Yet Napoléon not only fought for new principles: he also was a man of practical innovations. Ever concerned with the details of administration and government—indeed, if he made “war with his genius,” he made “politics with his passions”[85]—he consolidated hundreds of levels of unwieldy government bureaucracies into a much more merit-based, centrally controlled, and hierarchical administration, much of which is still in operation today. He also reformed the treasury, modernized accounting systems, and created a central bank. Local provincial governments were strengthened into prefects and administration greatly improved.

Napoléon’s reforms were arguably positive in many other areas. In the field of education, he mandated free education; improved the nation’s secondary school system with standardized curriculum, exams, libraries, and uniforms; reorganized the nation’s schools under a state model rather than a Roman Catholic model; and established a National University.[86] His interests in furthering the cause of science and research were seen most vividly in his Egyptian campaign and in the establishment of Les Archives Nationale, which have paid lasting dividends. Without the French invasion of Egypt, the Rosetta Stone would likely not have been discovered or decoded by Jean-François Champollion in 1822 (see chapter 2). In the arts, Napoléon improved the Louvre, erected many other museums, and encouraged fine art, architecture, and the opera. Though he feared the power of a free press, the books and pamphlets of the era were relatively free of government censorship. In public works, he built thirty-two hundred miles of new roads, a thousand miles of canals, introduced gas lighting, and beautified the city of Paris with new bridges, boulevards, and monuments.

As for religion, no one can doubt that he was a liberating, albeit secularizing, force. “Faith,” he once declared, “is beyond the reach of the law. It is the most personal possession of man, and no one has the right to demand an account for it.”[87] Although his own belief in God will ever be a point of debate, his was a force for religious toleration and pluralism. Napoléon declared freedom of religion throughout the regions under his control. He also restored the presence of the Catholic Church, without its dominance and exclusivity, by removing it from its place as the established church. Under his rule, the dreaded Italian laws of Inquisition and the horrors of the Spanish Inquisition were, at least for a time, done away with. Protestants as well as Moors (Muslims) were allowed to worship more freely than ever before and Jewish ghettos were abolished. Several Jews, in fact, looked upon Napoléon as their messiah for liberating them in whatever country he conquered, granting them full citizenship and freedom of worship. One modern scholar even went so far to say, “The encounter of the Jewish people with Napoléon was a turning point in Jewish history. For the first time, a modern statesman had envisaged the Jewish problem as a fundamental issue of international politics.”[88]

Napoléon’s softening of the absolute power of the clergy over the religious domain of France and several other European nations opened the door for a new kind of religious pluralism and freedom. While slow in coming, such new religious toleration opened the door for evangelistic Protestantism and for a host of other faiths.

If Napoléon consolidated the gains of the French Revolution within France, as a military conqueror he disseminated them beyond its borders in the Frenchification of Europe.[89] He was far more than a mere occupier; he was just as much a force for change in Berlin, Vienna, or Milan as he ever was in Paris. While the inner realms of empire—those countries closest to France—were more influenced by his reforms than those in the outer realms, Europe would never be the same because of him. Even the Congress of Vienna, which was dominated by his adversaries and ushered in almost a century of peace, preserved many of Napoléon’s reforms because of their popularity and liberalizing influence (see chapter 3). Thus, even in defeat, Napoléon may be said to have claimed partial victory.

Europeans may have hated the pride, power, and nationalism of Napoleonic France, but they found inspiration in Napoleon’s reforms. Little wonder the peasants welcomed him everywhere. The heavy hand of nobility, aristocracy, and privilege was dealt a severe blow in the name of the common class all over a Europe that was anxious to enjoy a better life. Clearly, Napoléon “advanced the position of the middle classes and provided an impetus to sound mobility on the basis of wealth, education, and merit, criteria that remained dominant in modern Europe.”[90] Governments all across Europe were modernized and made to be more efficient, more open, and, to some greater degree, more answerable to their people. The revolutions of the 1820s and 1830s were ample proof that it was not possible to return to the old order. And as will be shown in a later chapter, his military conquests and political reforms inspired Simón Bolívar, who in turn inspired the independence movement an ocean away that transformed so much of South America.

Thanks to Napoléon, many of the modern German, Polish, and Italian states were formed with far fewer divisions and far greater territorial unity than before. Napoléon radically redrew the map of Germany, reducing the number of sovereign states from over three hundred to approximately fifty, thereby creating the modern German confederation.[91] Good or bad, European nationalism of the modern era owes much to Napoléon.

As for Napoléon’s impact on religion, Joseph Smith’s vision of an expanding world religion could hardly have been realized without the liberalizing, liberating religious concepts of Napoléon, at least not on so grand an international scale. If Napoléon hastened the decline of established religions, he heralded a new age of religious pluralism that has benefitted a galaxy of new religions. As will be more amply shown in the following chapter, without Napoléon’s invasion of Egypt not only may the famed Rosetta Stone not have been discovered but also the papyri from which the Book of Abraham was eventually translated would likely never have been found.

Napoleon remains a difficult personality to capture and understand, especially in so short a study as this inevitably is. We give the final word to two of his most dedicated detractors. First from the French foreign minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord: “His career is the most extraordinary that has occurred for one thousand years. . . . He was clearly the most extraordinary man I ever saw, and I believe the most extraordinary that has lived in our age.” And this from the Austrian prime minister Klemens von Metternich: “By the force of his character, the activity and lucidity of his mind, and by his genius for the great combinations of military science, he had risen to the level of the position which [destiny] had destined for him. Having but one passion, power, he never lost either his time or his means in those objects which might have diverted him from his aim. Master of himself, he soon became master of events.”[92]

Notes

[1] Cronin, Napoleon, 21–22. “An analysis of Napoleonic autographs, of which thousands exist, shows that he always signed himself Buonaparte, then later Bonaparte. This was the name by which all his friends, and even his first wife, Josephine, knew him and addressed him, both officially and familiarly. . . . When he became emperor, he reluctantly adopted Napoleon as his name.” Johnson, Napoleon, 4.

[2] William, Women Bonapartes, 39.

[3] Cronin, Napoléon, 34. There is some evidence to show that a Breton nobleman, the comte de Marbeuf, may also have played a role in funding the young boy’s early education. See Johnson, Napoleon, 7–8.

[4] Markham, Napoleon, 18–19.

[5] Cronin, Napoleon, 52. In these formative years, Napoleon was a strong supporter of the republican (antimonarchist) movement. Once arrested for supporting other young revolutionaries, he later admitted, “When I was young I was a revolutionary from ignorance and ambition.” Seward, Napoleon’s Family, 23.

[6] Jones, French Revolution, 4. See Hunt, French Revolution, 3–5.

[7] “Because of their special status as mediators between God and humanity, members of the clergy enjoyed exemption from most taxes.” Popkin, Short History, 9.

[8] Jones, French Revolution, 4.

[9] Though on the losing side of the Seven Years’ War with England (1756–63), France supported the American War of Independence (1776–83) against England. These wars came at a steep financial price—as most wars invariably do—to the point that King Louis XVI’s government fell into virtual bankruptcy. The only solution was to increase revenue by drastically reforming an archaic system of taxation that had plagued the country for centuries.

[10] Jones, French Revolution, 25.

[11] Popkin, Short History, 35.

[12] Jones, French Revolution, 31. Thomas Jefferson was in Paris at the time of the storming of Bastille and at first was wildly in favor of the Revolution. However, unlike the American Revolution, which was a movement of independence from Great Britain, the French Revolution took on a thousand years of privilege from an entire class society that was thoroughly guarded by entrenched special interests. As one historian of the age wrote, “No event in European history ever caused such a change in the political thought of the ruling classes as did the French Revolution.” Fueter, World History, 16. By nature, the French Revolution would be a far bloodier affair than its American counterpart. As the intensity and bloodletting of the French Revolution unfolded, American support waned. See Kramer, “French Revolution,” in klaits and Haltzel Global Ranifications.

[13] King Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette had “greatly underestimated the extent of popular support for the Revolution” and wrongly believed that a great counter-revolution would restore them back to power. Tackett, When the King Took Flight, 56. See also Tackett, The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution, chapter 3 & 4 in particular.

[14] Popkin, Short History, 76.

[15] Popkin, Short History, 76.

[16] Jones, French Revolution, 8.

[17] Tackett, When the King Took Flight, 167.

[18] Popkin, Short History, 86.

[19] Jones, French Revolution, 60–62.

[20] In the early days of the Revolution, Napoléon Bonaparte was “a ferocious republican” and antirevolutionary. He was arrested for his close support of Robespierre but was released soon after. Seward, Napoleon’s Family, 22.

[21] Cronin, Napoleon, 76.

[22] “Bonaparte preferred musket balls encased in tins, known as canister or caseshot, or in canvas bags, known as grapeshot. The advantage of grapeshot was that it scattered over a wide area, tending to produce a lot of blood and often maiming its victims, but had to be fired at close range. It rarely killed and thus, while effective as drastic crowd control, did not enable opponents to create the myth of a ‘massacre.’ Its aim was to frighten and disperse. But it ended the attempted coup forthwith, and with it the Revolution itself: the era of the mob yielded to a new era of order under fear.” Johnson, Napoleon, 26–27.

[23] Markham, Napoleon, 57.

[24] Markham, Napoleon, 59. See chapter 2.

[25] Cronin, Napoleon, 152.

[26] Crook, Napoleon Comes to Power, 3.

[27] Jones, French Revolution, 76.

[28] Jones, French Revolution, 83.

[29] Markham, Napoleon, 95.

[30] “Napoleon had an established reputation for continence. . . . It rarely seems that carnal impulse troubled him hardly at all.” Aubry, St. Helena, 210, 292.

[31] Seward, Napoleon’s Family, 39.

[32] Tulard, Napoleon, 232.

[33] Becke, Napoleon’s Waterloo, 165.

[34] Tarbell, Life of Napoleon Bonaparte, 291.

[35] Review of Relation Circonstanciée de la Campagne de 1813 en Saxe by M. Le Baron d’Odeleben, 216.

[36] Luvaas, “Napoleon on the Art of Command,” 31.

[37] Cronin, Napoleon, 128.

[38] “In this way,” writes another of his biographers, “he was able to concentrate overwhelming masses of men against opponents whose overall numbers were much greater than his own.” Seward, Napoleon’s Family, 32.

[39] Markham, Napoleon, 37.

[40] “Bonaparte,” Ladies’ Literary Cabinet 44.

[41] Markham, Imperial Glory, 5.

[42] Emerson, History of the Nineteenth Century, 1:190.

[43] Strawson, The Duke and the Emperor, 15.

[44] Becke, Napoleon’s Waterloo, 21.

[45] Roberts, Napoleon and Wellington, 283.

[46] Markham, Imperial Glory, 53.

[47] Ellis, Napoleonic Empire, 74–77.

[48] Tulard, Napoleon, 148.

[49] Emerson, History, 1:210.

[50] Markham, Imperial Glory, 233.

[51] Browning, Boyhood and Youth, 56–57.

[52] Emerson, History, 1:420–21.

[53] See Labaume, A Circumstantial Narrative of the Campaign in Russia, for one of the earliest accounts of the Russian campaign. For one of the most recent and perhaps most remarkable studies of this episode, see Zamoyski, Moscow 1812.

[54] Cronin, Napoleon, 318.

[55] LaBaume, Campaign in Russia, 400.

[56] Cronin, Napoleon, 328.

[57] Cronin, Napoleon, 351.

[58] Becke, Napoleon’s Waterloo, 2.

[59] Becke, Napoleon’s Waterloo, 191.

[60] Bourrienne, Memoirs, vol. 16, 13.

[61] Becke, Napoleon’s Waterloo, 227.

[62] Emerson, History, 1:586–87.

[63] Markham, Napoleon, 252.

[64] Aubry, St. Helena, 43. General LaFayette had offered to take him to America in a merchant vessel.

[65] Coote, Napoleon and the Hundred Days, 271.

[66] Ballard, Napoleon, 293.

[67] Blackburn, Emperor’s Last Island, 147.

[68] Blackburn, Emperor’s Last Island, 161–62.

[69] Bourriennne, Memoirs, 16.

[70] Aubry, St. Helena, 314.

[71] Bourrienne, Memoirs, 16.

[72] Ballard, Napoleon, 290 and Markham, Napoleon, 203.

[73] “Death of Napoleon Bonaparte,” Saturday Magazine, 207–8.

[74] Ballard, Napoleon, 292.

[75] Bourrienne, Memoirs, chapter 16.

[76] Johnson, Napoleon, 182.

[77] Johnson, Napoleon,183.

[78] Tarbell, Life of Napoleon Bonaparte, 293–94.

[79] Johnson, Napoleon, 186.

[80] Hazareesingh, “Napoleonic Memory,” 748.

[81] Hazareesingh, “Napoleonic Memory,” 766.

[82] Byman and Pollack, “Let Us Now Praise Great Men,” 127.

[83] Markham, Napoleon, 257.