"To Extend the Boundaries of Zion"

The London Missionary Society and Rev, John Williams, "Apostle of Polynesia"

Richard E. Bennett, “'To Extend the Boundaries of Zion': The London Missionary Society and Rev. John Williams, 'Apostle of Polynesia,'” in 1820: Dawning of the Restoration (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 231‒58.

“Some were tattooed from head to foot; some were painted most fantastically, with pipe-clay and yellow and red-ochre; others were smeared all over with charcoal; and in this state were dancing, shouting, and exhibiting the most frantic gestures.”[1] Upon welcoming Chief Tamatoa on board his vessel, the twenty-five-year-old Reverend John Williams found he could converse readily with the chief in his own language and told him of the Christianizing influences then happening in the Tahitian and Society Islands. “He asked me, very significantly, where great Tangaroa was? I told him that he, with all the other gods, was burned. He then inquired where Koro of Raiatea was? I replied, that he too was consumed of fire; and that I had brought two teachers to instruct him and his people in the word and knowledge of the true God.” The two men were pressing noses in greeting when the chief suddenly spotted the minister’s four-year-old boy, the first European white child he had ever seen. The child “attracted so much notice, that every native wished to rub noses with the little fellow” and begged John Williams to give the child to them, to make him king. But the mother and child quickly hastened away to the ship’s cabin, fearful of possible kidnapping, torture, or worse.[2]

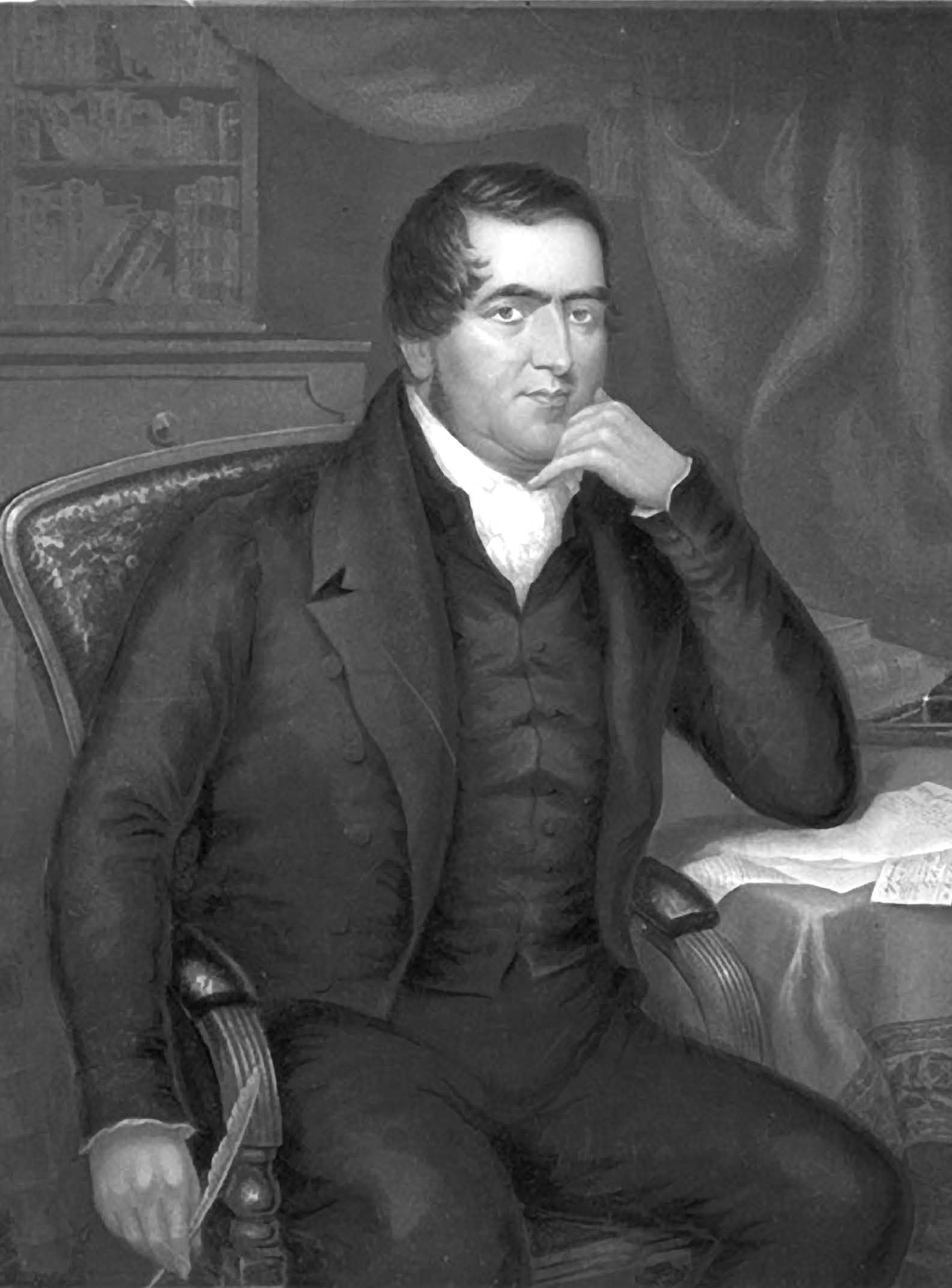

The Rev. John Williams, the Martyr of Erromanga, with a Landscape of the Mission House and Grounds of Rarotonga, by George Baxter.

The Rev. John Williams, the Martyr of Erromanga, with a Landscape of the Mission House and Grounds of Rarotonga, by George Baxter.

The above account was written by the Reverend John Williams of his first encounter with the native islanders of Aitutaki of the Cook Islands of the South Pacific in the year 1821. It was but one of scores this illustrious “apostle of Polynesia” from the London Missionary Society (LMS) would write during a lifetime of dedicated missionary service among the peoples of the South Pacific. His was a life that many years later would end tragically on the shores of yet another beautiful, mysterious South Sea island.

The Christian evangelization of indigenous Pacific peoples is a hotly debated topic among many modern scholars. Some argue that it was an exercise in western paternalism, a “cultural” or “Christian imperialism,” expressed in how Christian missionary societies looked down upon their distant counterparts with thinly veiled disdain and all but replaced their native cultures. To this school of thinking, the Western missionary agenda was a “treacherous” exercise, one “inseparably linked to a broad and deliberate effort to dismantle” local cultures.[3] Such efforts were viewed as nothing short of the imposition of one, supposedly more advanced empire, on a far less advanced, “heathen” society, more of a disservice than a blessing. These Christian missionaries, and quite often their wives, feared intimacy with the locals, refused to send their children to native schools, and in other ways refused “going native.”[4] As Emily Conroy-Krutz has likewise argued, such missionaries obeying the Great Commission may have seen themselves as “servants of Christ” but were actually “partisans of a particular Anglo-American style of civilization.”[5]

There may well have been some Christian missionaries who thought this way, who harbored prejudices, fears, and biases toward the islanders and their way of life. Certainly, Christian missionaries saw some islander practices as destructive, particularly slavery, human sacrifice, infanticide, and polygamy, and were committed to eliminating such practices. These missionaries were equally critical of the drunken European or American beachcomber and the lascivious buccaneer influences that proved harmful and degrading to so many in the islands.[6] For those missionaries who spent much of their adult lives among the islands of the Pacific, they could not have succeeded without the love and respect of the people they had set out to teach and convert. Their main intention was not so much to supplant one empire with another, but to educate, evangelize, and make safer the world about them. Some even translated local beliefs and customs to send back home, to give the so-called civilized world the best of a distant culture in what was sometimes a two-way beneficial process of learning. Admittedly, not all missionaries were respectful of, or “Christian,” to the island peoples; however, the fact is men and women like the Williams were highly esteemed by their native counterparts who sought to learn what they knew and believed.

If every age must have its heroes, then the name that had captured the imagination of the people of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century was the adventurous circumnavigator and intrepid British explorer Captain James Cook (1728–79). On board his famous ships HMS Endeavor and later HMS Revolution, this incomparable seaman conducted three memorable voyages: first of the southern seas and two later on of the entire Pacific Ocean, from 1768 to 1779. His vivid journal descriptions of majestically beautiful, faraway islands and accompanying traditions of native life proved irresistibly popular to both English and European audiences. By circumnavigating the southern waters around Antarctica, Cook was the first to map the entire coastline of New Zealand, to find several island chains in the South Pacific, to map much of eastern New South Wales (Australia), to found Botany Bay, and to prove the nonexistence of a habitable southern continent. Cook was also the first European to have widespread and sustained contact with the various native peoples of the Pacific and was the first to argue that there was an anthropological relationship among them. He was also the first to successfully combat scurvy, the sailor’s dreaded scourge, through the use of such fresh citrus as lemons and limes.

Sailing the vast Pacific Ocean from east to west and then from south to north, Cook mapped the entire coastline of northwestern North America (north of Nootka Sound to Alaska) and proved the impenetrability of the ice-jammed Bering Sea and, with it, the improbability of an easy Northwest Passage connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific. While returning from his third voyage, he landed on the Hawaiian Islands, which he promptly christened the Sandwich Islands, where unfortunately he was killed by native islanders in 1779. His tragic death stirred his many readers, some of whom vowed someday to spread the gospel to these same beautiful, faraway isles of the sea. In praise of the great navigator, Rev. Williams said, “[His] name I never mention but with feelings of veneration and regret.”[7]

Born 29 June 1796 at Tottenham High Cross, a suburb of London, John Williams was a child of the Industrial Revolution. Although his mother insisted that he receive a religious upbringing, his apprenticeship at the age of fourteen to an ironmaker by the name of Enoch Tonkin brought out his native interests in the mechanical arts. Particularly adept at blowing at the forge, hammering out new tools, and repairing and recasting a myriad of mechanical parts, young Williams soon “became a skillful workman, and was able to finish more perfectly than many whose lives had been devoted to the attainment.”[8]

Thanks to Mrs. Tonkin, Williams also experienced a Christian conversion in 1814 during his eighteenth year as he listened to a sermon by the Reverend Timothy East. “What is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” the minister had demanded. “From that hour my blind eyes were opened,” Williams later recalled, “and I beheld wondrous things out of God’s law. I diligently attended the means of grace. I saw the beauty and reality in religion which I had never seen before. My love to it and delight in it increased, . . . and I grew in grace, and in the knowledge of my Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ.”[9] Soon afterward, young Williams became an avid Sunday School teacher.

Upon learning of the LMS, he applied in July 1816 to become one of their missionaries. The LMS had just learned of the amazing evangelical successes of the Reverend Henry Nott in Tahiti and was desperately seeking young new missionaries—preferably married. In late October 1816, Williams married Mary Chauner, “the ornament of a meek and quiet spirit,”[10] who was as equally committed to promoting the Christian gospel as he was. Just weeks later, on 17 November 1816, John and Mary Williams set sail on board the Harriett on a five-month voyage to Sydney, New South Wales, and on a twenty-five-year mission to the South Pacific. Theirs was destined to become one of the most successful Christianizing missions of the nineteenth century. The work of John and Mary Williams cannot be fully appreciated without first placing it within the larger context of the tract and Bible societies of which the harder Missionary Society war so much a part.

“This Is the Age of Societies”

“This is the age of societies,” wrote the British historian Thomas Macaulay in 1823.[11] It expressed itself in ways that crossed over many cultures and in many fields of endeavor, foreign or domestic. Some such societies were formed to establish universal peace, to Christianize the Jews, or to improve upon the family. This surging humanitarian and religious impulse was neither government-sponsored nor denominationally directed. Instead, it was a local, spontaneous, Protestant-inspired groundswell spreading from England that was in many ways a reaction to the irreligious spirit of the French Revolution.

Some of the societies that contributed to this era of change were designed solely for women—the Institution for the Protection of Young Country Girls; the Ladies’ Association for the Benefit of Gentlewomen of Good Family, Reduced in Fortune Below the State of Comfort to Which They Have Been Accustomed; and the Friendly Female Society for the Relief of Poor, Infirm, Aged Widows and Single Women of Good Character Who Have Seen Better Days. Others catered generally to the poor—the so-called mendicity orders—including the Climbing Boy Society (aiding young chimney sweeps), the General Benevolent Institution for the Relief of Decayed Artists of the United Kingdom, and the Clothing Society for the Benefit of Poor Pious Clergymen.

Far more than casual afternoon tea get-togethers, such societies were strongly supported by the Quakers, the orthodox clergy, evangelicals, and many in the upper classes of society, depending on the cause. The Small Debts Society, for instance, helped discharge twenty-four thousand men and women from debtors’ prisons by 1808 at a cost of sixty-six thousand pounds.[12] And some, like the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals have survived to the present day.

Of all the many religious societies, three kinds or groupings are especially relevant to our discussion: the religious tract societies, the Bible societies, and finally, the missionary societies.

Inspired in large measure by the Cheap Repository Tracts of Hannah More, as well as the spectacular rise in popularity of the Sunday School movement of Robert Raikes (see chapter 8), the dual aim of most of these tract societies was to counter the concomitant rise of popular vile and vulgar literature, especially among the poorer classes. They also set out to improve moral behavior in England and abroad and to spread Christianity worldwide through the power of the pen. Although religious tract societies had been in existence in England since 1647, the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge Among the Poor in England (instituted in 1799) was the parent of the religious tract phenomenon.

Other tract societies soon sprang up all over England and later in the United States and British North America (Canada) and as far away as India, China, and Ceylon. The London Religious Tract Society (established in 1799) became the most ambitious of them all, distributing an astonishing thirty million tracts by 1820 and creating 999 branches and 4,595 auxiliaries.[13] “Your Tracts instruct the ignorant in the Sunday School,” one religious paper exulted in 1820, “in the factory, in the fields, in the mines, by the docks, and on the public way. Your tracts enter the cottages of the poor, the chamber of disease, the cell of the condemned, and yield consolation and hope to the wretched and the dying; and perhaps, in many instances, unknown to us . . . they are the means of saving knowledge and eternal life.”[14]

In North America, the New England Religious Tract Society, established in 1814, became the most famous of all American tract societies. By 1855 it had distributed 800,000 tracts of its own, containing over ten million pages.[15] These North American tracts, like their English counterparts, included hymns, stories for children in Sunday Schools, scriptures, sermon extracts, prayers, and more.

“Without Note or Comment”

These religious tract societies served well as indispensable aids to the far-flung missionary efforts and became the essential precursor to the even more spectacularly successful Bible societies. However, the spark that ignited the Bible movement was the desperate lack of Bibles in northern Wales, most poignantly felt by a sweet Welsh maiden. Since 1791, Wales had been experiencing a religious awakening and among the converts was one Mary Jones, then a girl of about ten years of age. She walked two miles every Saturday to a relative’s home to read from the nearest Bible. Over the next several years, she tried hard to save enough money to finally purchase her own set of scriptures, which she did when seventeen years old, after walking twenty-eight miles barefoot to buy her first Bible from the good reverend Thomas Charles. As the popular story goes, “He reached her a copy, she paid him the money and there [they] stood, their hearts too full for utterance, and their tears streaming from their eyes.”[16]

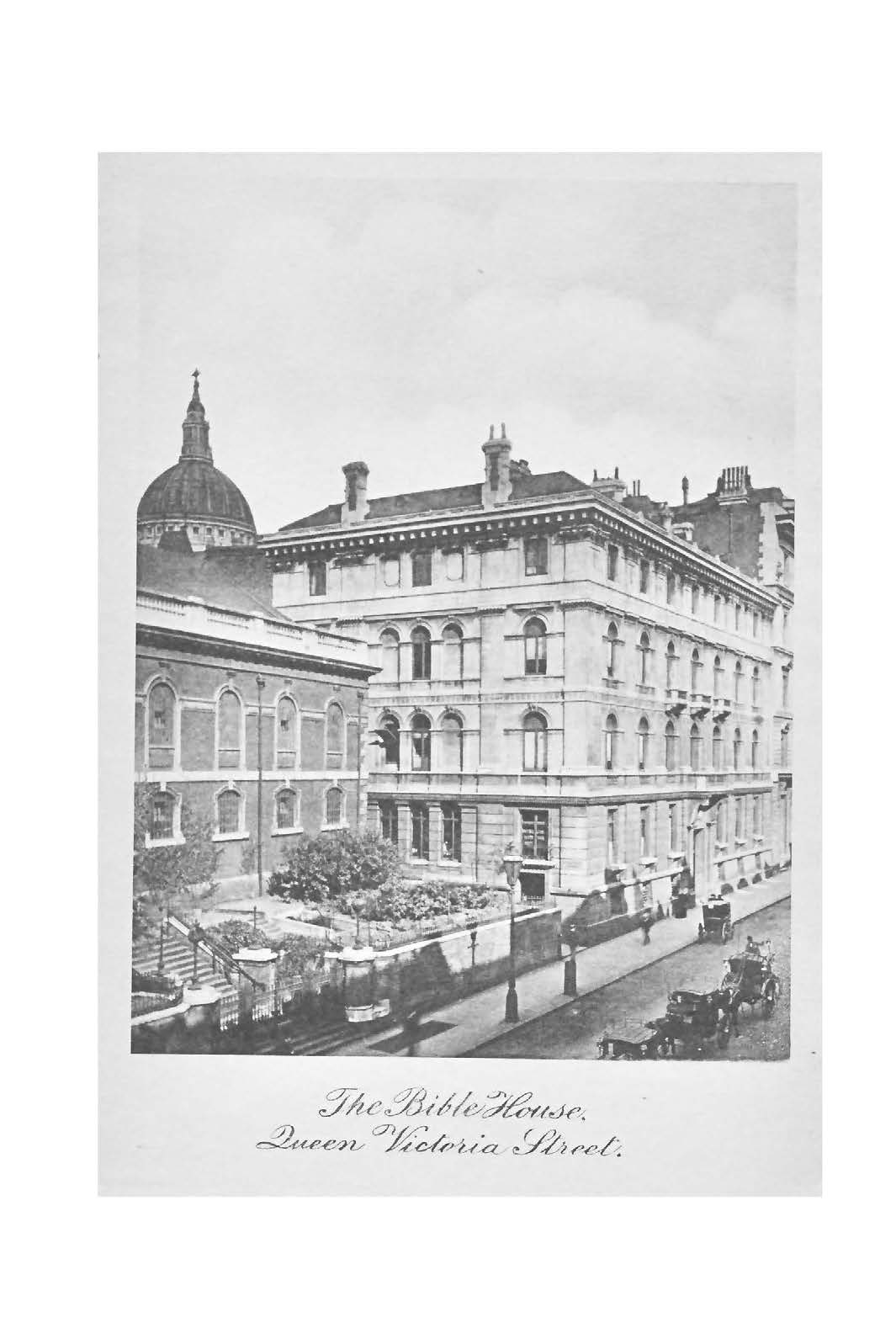

Inspired by the young girl’s devotion, Rev. Charles traveled to London in 1802 in quest of ten thousand Welsh Bibles from the almost moribund Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, an Anglican Bible Society that had begun in 1698.[17] Its representatives declined his request. He then approached the LMS and Religious Tract Society. Rev. Joseph Hughes of the latter society wondered why no such vibrant Bible society existed. Subsequently, he, along with Rev. C. Steinkopf of the German Lutherans, Rev. John Owen (chaplain to the Anglican bishop of London), Samuel Mills, Zachary Macauley, William Wilberforce, Granville Sharp, and some three hundred others set about organizing the founding meeting of the Society for Promoting a More Extensive Circulation of the Scriptures at Home and Abroad on 7 March 1804 at 123 Bishopsgate Street in London. Soon renamed the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS), the BFBS immediately garnered interdenominational, pan-evangelical support, with its first three secretaries acting as a triumvirate: John Owen, Anglican; Joseph Hughes, evangelist or Nonconformist; and Carl F. Steinkopf, foreign. The respected John Shore, Lord Teignmouth, was appointed president, an office he would hold for thirty years. Its purpose was “to encourage a wider dispersion of the Holy Scriptures through the British Dominions and to other countries whether Christian, Mahomedan, or Pagan.”[18] Thus was born “a society for furnishing the means of religion, but not a religious society.”[19] In short order, the BFBS printed twenty thousand Welsh Bibles and in the space of only three years, printed, and distributed 1,816,000 Bibles, testaments, and portions thereof in sixty-six languages.[20]

The British and Foreign Bible Society, London. From A History of the The British and Foreign

The British and Foreign Bible Society, London. From A History of the The British and Foreign

Bible Society, by William Canton.

What accounts for this remarkable success? Most scholars rightly point to the BFBS’s multidenominational organization and support as a critical positive factor. While some Anglican clergy in particular bemoaned the absence of the Book of Common Prayer, and later arguments erupted over whether or not to include the Apocrypha, virtually everyone rallied around its constitution, the seminal first article of which mandated that its Bibles (then only the King James Version) be distributed “without note or comment.” Prefaces, explanatory notes, and particular creeds and theologies “were explicitly forbidden.”[21] The conviction reigned that the power of the word was sufficient enough to inspire, reprove, correct, and instruct “in righteousness” (2 Timothy 3:16).

While the original leadership was deeply religious, they were also tough-minded business people, innovators, and risk-takers with a global perspective. Soon after the society’s formation and in the wake of Napoléon’s recent defeat in 1812, Secretary Steinkopf embarked on incredibly ambitious tours of Prussia, Denmark, Russia, Sweden, and Finland, even the Middle East. Unforeseen by these founders was the remarkable and immediate popularity of what rapidly became a thriving business and a vast, international grass-roots movement. The rapid multiplication of auxiliaries and associations, in chain-reaction style in virtually every county in the United Kingdom, throughout Europe (including France), in Russia, in North America, and even in parts of the Orient, was a critical element of the society’s success.[22] Its phenomenal expansion was clear evidence of the popular desire for Bibles at home and abroad.[23]

Local leaders of various Christian faiths, including Roman Catholic priests in several areas, with independent boards soon joined in promoting subscriptions, appointing agents, and receiving and filling orders for scriptures.[24] This capillary action, extending down to the hosts of volunteer “home visitors” and colporteurs (traveling salesmen) who went from house to house, skirted the traditional bookseller method of distribution. At this level, women served by the thousands, often appointing their own auxiliaries with their own presidents, officers, and appointments. The ladies’ associations were “enormously more successful and widespread than those of gentlemen” in distributing both tracts and Bibles.

No gentleman could be found, who would undertake the task of going from house to house, to receive the subscriptions, and to make the necessary inquiries into the actual want of Bibles; but . . .[the ladies] immediately set to work with cheerfulness and courage, not minding the cold and even unfriendly reception which they met with here and there. . . . On entering a room whence an old woman was about to dismiss them with repulsive language, a poor girl, who had earnestly listened to their representation, arose from her spinning wheel, saying, in a cheerful tone, “I believe I have a few halfpence in my box; most gladly will I give them for so blessed a design.” She fetched them, and they were her little all. Her conduct softened the old woman, and she likewise came forward with a few pence.[25]

By 1819, the BFBS counted 629 such auxiliaries, and in 1820 women home visitors in Liverpool alone made 20,800 Bible visits.[26]

The critical barrier, however, to popular ownership of the Bible in the United Kingdom and elsewhere was not so much ignorance, illiteracy, indifference, or even Catholic resistance but poverty—abject and universal. As late as 1812, British bishops estimated that at least half the population of the United Kingdom was destitute of Bibles.[27] In Ireland and other more impoverished countries, the percentage was steeply higher.

Thanks to the significant contributions of hundreds of wealthy philanthropists and the thousands of small donations from supporters everywhere, the BFBS vigorously financed ways to reduce the costs of production. By former royal decree, Cambridge University, Oxford Press, and the King’s Printer owned the charters for printing the authorized King James Version of the Bible, if for no other reason than to ensure accuracy and dependability. But by ordering vast quantities, using such new advances as steam-power presses and stereotype printing (a process by which pages of type were cast as permanent metal plates and stored for reprinting),[28] using cheaper paper and binding, and printing in smaller quarto size volumes, the society continued to reduce the costs of its Bibles. A Bible that once cost a day’s wages now sold for twenty-five shillings, within reach of most family incomes.

The proliferation in Bibles was not just a matter of reduced cost. The society early on vigorously sought to translate the scriptures into foreign languages, beginning with Mohawk language for those in Upper Canada (Ontario). Other early translations soon followed, including Italian (1807), Portuguese (1809), Dutch (1809), Danish (1809), French (1811), and Greek (1814). As one contemporary put it: “The most extraordinary disposition of the whole, however, is the remarkable exertions in translating the Bible into so many different languages—in 17 languages in the Russian Empire alone. . . . This is an extraordinary event. The like, in all circumstances, has never taken place in the world before.”[29]

Yet even this winning combination of affordability, sound leadership, excellent organization, spirited volunteers, and a distribution system using Great Britain’s Royal Navy does not fully explain the phenomenon. The fact is, in this prescientific epoch, the times were right for this new holy war. Many interpreted the successful termination of the Napoleonic Wars as a victory of Christian thought against the godless secularism of the French Revolution, a divine approbation of the expanding British Empire. They saw it as a new “Age of Light” of blessed opportunities, a “New Morality.”[30] “Since the glorious period of the Reformation,” wrote one American observer in 1818, “no age has been distinguished with such remarkable and important changes.”[31]

What had started inauspiciously quickly exceeded every expectation of the society’s founders. Speaking in the spring of 1820, the Right Honourable Lord Teignmouth, former governor general of the British East India Company and president of the BFBS, took justifiable pride in the society’s spectacular accomplishments:

Never has the benign spirit of our holy religion appeared with a brighter or a more attractive luster, since the Apostolic times, then in the zeal and efforts displayed during the last sixteen years for disseminating the records of divine truth and knowledge. The benefit of these exertions has already extended to millions, and when we contemplate the vast machinery now in action for the unlimited diffusion of the Holy Scriptures, the energy which impels its movements, and the accession of power which it is constantly receiving, we cannot but indulge the exhilarating hope, “that the Angel, having the everlasting Gospel to preach to them that are upon the earth” has commenced his auspicious career. Even now, the light of divine revelation has dawned in the horizon of regions which it never before illuminated, and is becoming visible in others in which it had suffered a disastrous eclipse. . . . By His special favour the Bible Institution has proved a blessing to man-kind, and with the continuance of it . . . it will be hailed by future generations as one of the greatest blessings, next to that of divine Revelation itself, ever conferred on the human race.[32]

As of 1834 the BFBS had distributed 8,549,000 Bibles in 157 different languages.[33] By 1900 that figure had grown to 229,000,000 volumes of scripture in 418 languages. And by 1965 it had printed 723,000,000 volumes in 829 languages![34]

“Errand of Mercy”: The American Bible Society

In America, the need for Bibles was no less real and immediate. Up until 1780 almost all Bibles circulating in America had been printed in Great Britain. The Puritans had brought with them their Geneva Bible, first published in 1560, with its notes and teachings by John Calvin. Other immigrants brought the so-called Bishops’ Bible, published by the Church of England in 1568.[35] With the suspension of British imports during the Revolutionary War, there developed a “famine of Bibles” in America, one of the many ills which “a distracted Congress was called upon promptly to remedy.”[36] Scottish-born Robert Aitken, at the direction of Congress, became America’s first Bible publisher in 1781. Isaiah Thomas printed the first folio Bible from an American press ten years later. The Quaker Isaac Collins began printing his Bibles, known for their accuracy, that same year. The Irish-American Matthew Carey became the best-known Bible printer in early America, publishing more than sixty different editions in the early 1800s.[37] Between 1777 and 1820, propelled in part by the Second Great Awakening, the formation of Bible societies, and the aim of evangelizing the West,[38] four hundred new American editions of Bibles and New Testaments had been issued. By 1830 that number had climbed to seven hundred.[39]

Such increased production could not, however, keep up with population growth. Between 1790 and 1830, America’s population skyrocketed from 3.9 to 9.6 million, with a very large number of people still not owning their own Bibles. For instance, an 1824 Bible society report from Rochester, New York, reported that in Monroe County alone some twenty-three hundred families were without Bibles.[40] An 1825 report stated at least 20 percent of Ohio families were without Bibles and in Alabama, out of its thirty-six counties, half of the population did not own scriptures. In that same year, a reported ten thousand people in Maine were without Bibles, and in North Carolina there “cannot be less than 10,000 families . . . without the Bible.” Even large metropolitan areas, such as New York and Philadelphia, were reported as seriously lacking.[41]

Such lack had been the reason for the organization of the Philadelphia Bible Society in 1808, the Connecticut and Massachusetts Bible Societies in 1809, and the New York Bible Society in that same year. Scores of others followed throughout New England and in the South. Yet even with these, many feared not “famine of bread, not a thirst for water, but of hearing the words of the Lord” (Amos 8:11). Among these was the intrepid reverend Samuel J. Mills, who viewed the Louisiana Purchase and the opening of a vast new western frontier as a potential new “valley of the shadow of death” (Psalm 23:4) in a future America unschooled in the Bible. In a series of tours and travels throughout the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys, Mills spread his message of Christian revivalism. More than any other person, Mills was the inspiration for the establishment of the American Bible Society (ABS).[42]

Seeing the need for cheaper American Bibles at a convention of American Bible societies in New York, Samuel Mills, Lyman Beecher, Thomas Biggs, Jedediah Morse, John E. Caldwell, William Jay, and several others presided over the formation of the ABS in May 1816. Elias Boudinot, of Cherokee descent and a former New Jersey delegate to the Continental Congress, presided over the society in its infant years. Soon forty-two other smaller state and regional societies merged under its expanding banner.[43]

Like its British parent and model, the ABS had as its sole object “to encourage a wider circulation of the Holy Scriptures without note or comment.”[44] In what was called the “General Supply,” the aim of the ABS was to furnish or “supply all the destitute families in the United States with the Holy Scriptures that may be willing to purchase or receive them.”[45] It also aimed at resisting Thomas Paine’s godless Age of Reason, a work that the ABS viewed as a “type of infection” and a flood of infidelity.[46] In addition to its primary goal of disseminating scriptures, it also served as a catalyst for local religious revivals and very much supported evangelistic activities and temperance movements.[47] Initially headquartered on Nassau Street in New York City, the ABS constantly enlarged its facilities to keep up with demand as well as advances in technology. Stereotype plates facilitated the printing process; auxiliaries soon spread to most American cities (301 by 1821); and every effort was made to put copies of the scriptures in every home. Among its many early translations were French, Spanish, and some Native American languages, the first of which was Delaware. After just four years in operation, the ABS had printed and distributed 231,552 Bibles and New Testaments.[48] By 1830 the numbers had climbed to 1,084,000.[49] By 1848 that figure would reach 5,860,000. And by 1916, after its first century, the corresponding figure stood at 115,000,000 volumes of scripture printed in 164 different languages.[50] Where the Smith family found its Bible that came to have such enormous influence on the boy prophet, Joseph Smith, is unknown (see chapter 13); however, it may well have come from the efforts of the American Bible Society. Without such a set of scriptures in his home, it is doubtful he would have ever been led to reading the scripture that changed his life—James 1:5–6—or made the invocations that led to a whole new religion.

“Go Ye into All the World”: The Age of Missionaries

As impressive as were the accomplishments of these tract and Bible societies, it was the dedicated men and women of the reinvigorated missionary societies who, in spending their lives in the cause, “extend[ed] the boundaries of Zion” in so real and permanent a way. Their stories of devotion and adventure, hardship and suffering—both in the home missions within England as well as those far afield—would fill volumes.

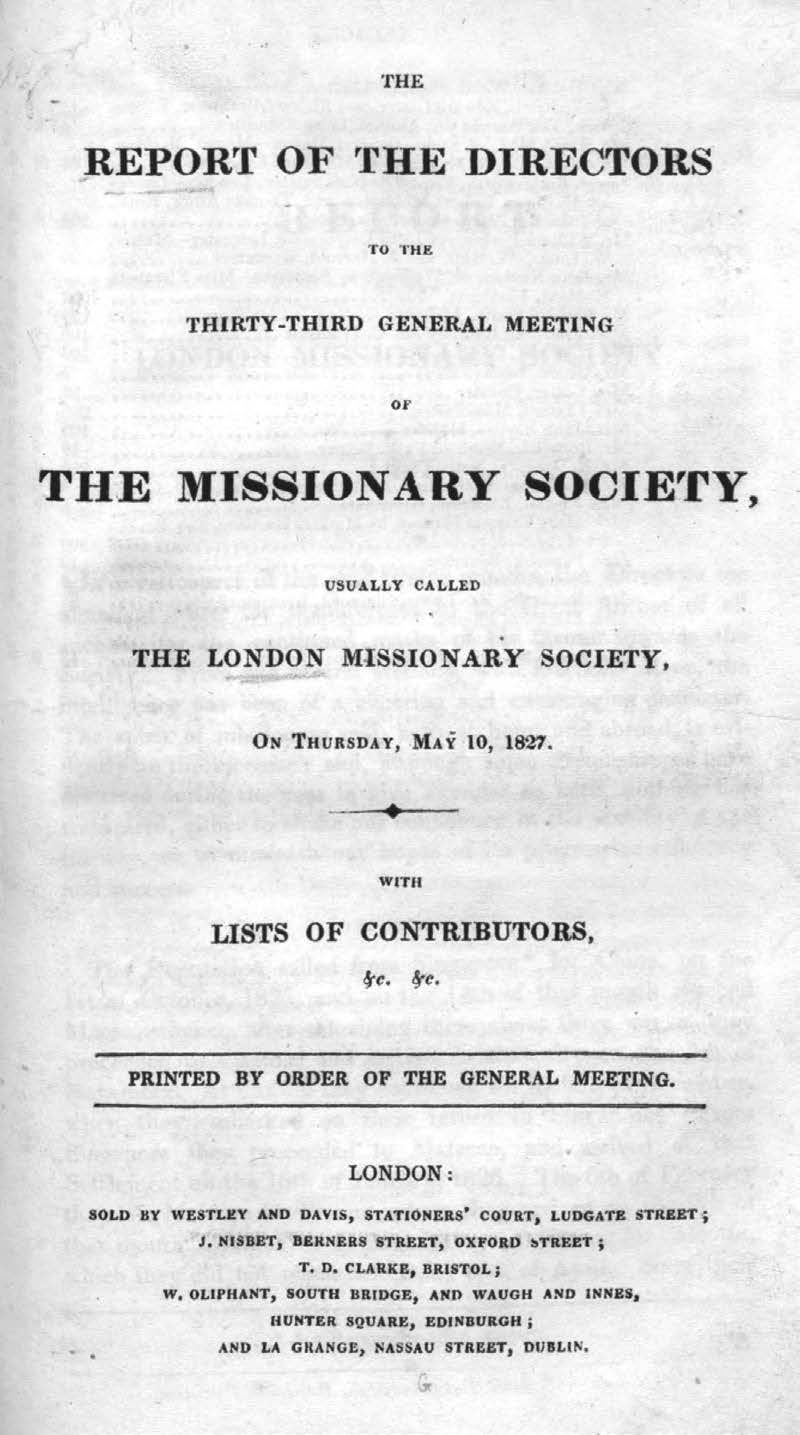

The Reverend John Williams characterized this as the “Great Century” of modern missions. While Catholicism had its full share of intrepid Jesuit missionaries in the form of St. Jean de Baptiste (1686–1770), Pierre Jean de Smet (1801–73), and many others, the Protestant initiatives were launched by William Carey (1761–1834), “the father of modern missions.”[51] A masterful linguist, agriculturalist, botanist, and lover of books and learning, Carey authored the famed Enquiry into the Obligations of the Christians to the Means for the Conversion of the Heathen.” Carey devoted forty years of unbroken service as a Baptist missionary in India, beginning in tiger-infested jungles of Sunderbund, south of Calcutta, and later in Serampore, north of Calcutta. Carey mastered not only the languages but also the literature in Sanskrit, Punjabi, Bangali, and Mindi. He also translated and published the Bible from English into forty languages and dialects of India and Southeast Asia. A careful and wise administrator, he discreetly handled the antagonism of both local Indian officials opposed to Christianity, as well as the opposition of the East India Company (at least until its charter, guaranteeing religious freedom, was renewed in 1813), which worried that religious tampering might threaten its profits. Carey established a lasting reputation as a Christian educator who fell in love with his adopted country. Though an ardent proponent of Christianity, he founded Serampore College in Bengal in 1819 and became “an architect of secular education and social reformation in India.”[52] What made his college so successful a role model and one so far ahead of its time was the policy of imparting all instruction in both English and local languages, of teaching the most modern Western sciences and classic Western literature in combination with a respect for Indian literature and culture, and of including a faculty of Christian theology. No less a pioneering feat in what was then a rigid caste-bound society, his college was “open admission to all persons, irrespective of caste, creed, color or religion.”[53]

Suffering the loss of his wife, Dorothy, and two of his children, Carey soldiered on until his own death in June 1834. By that time, there were thirty missionaries in India, forty-five native teachers, forty-five stations, and over six hundred Christian converts. More than anyone else, Carey inspired the formation of the LMS in 1795 and the Church Missionary Society in 1799. Carey “inaugurated a new era of united, organized and systematic operations” that have persisted to the present day.[54]

Report of the Directors to the Twenty-Third General Meeting of the Missionary Society, in London, on Thursday, May 15, 1827.

Report of the Directors to the Twenty-Third General Meeting of the Missionary Society, in London, on Thursday, May 15, 1827.

Carey’s pioneering counterpart in China was the Reverend Robert Morrison (1782–1834). Having learned Chinese before his mission departure in 1807, he worked for the East India Company for a time before becoming a resident of China. A narrow survivor of the emperor’s 1812 edict that forbid the printing of any Christian books on pain of death, Morrison completed his translation of the New Testament into Chinese in 1814. After twenty-seven years of persecution, “incessant labour and of great loneliness for the Master’s sake,” deprivation of family for several years, and subsistence living on a diet of only Irish stew and dried roots, Morrison baptized only ten persons.[55] Yet, despite almost every conceivable discouragement, he produced his English-Chinese dictionary, established the Anglo-Chinese College at Malacca, and finally translated the entire Bible into Chinese.[56]

Besides the Far East, three other areas of special concern for the LMS were the British West Indies (Jamaica and British Guiana), Africa, and the South Pacific. The Reverend John Smith will ever be remembered for his Christianizing, courageous, and liberalizing efforts among the much-abused and tortured slaves of Demerara, Berbice, Jamaica, and elsewhere in the West Indies. What Smith opposed was a culture of atrocity and inhuman cruelty to enslaved people, which included lack of medical treatment, the prohibition of marriage, gross licentiousness, whippings, indiscriminate and defenseless murdering, black holes of endless punishments, insufficient nourishment, and excessive work demands.[57] Despised on the one hand by many white plantation owners for fomenting ideas of freedom, equality, and human dignity, he was cherished on the other hand by the native populations who welcomed his liberating spirit, sense of human justice, unflinching honor, integrity, and Christian zeal. Tragically, Rev. Smith was imprisoned in hideous circumstances. He perished in 1824, a martyr to his cause, and is buried in an unmarked grave somewhere on the beautiful isle of Jamaica.[58]

William Carey, by unknown artist.

William Carey, by unknown artist.

Dr. J. T. Vanderkemp, MD, was the first LMS missionary to South Africa, arriving there in 1797, just two years after the British seizure of the former Dutch colonies there. Distrusted by both disgruntled Dutch farmers and nervous British overseers and administrators for believing in “equal rights for blacks and whites, for Kafir [natives] and Boer, for Hottentot and colonist,” Vanderkemp spread the Christian gospel to native and colonist alike and in the process founded Bethelsdorp, a Dutch colony. He died in Cape Town at age sixty-three in 1811.

He was succeeded by the Reverend John Campbell in 1812 and Dr. John Philip in 1819, both of whom were vilified by British and Dutch established interests for their “ceaseless, energetic, and successful toil on behalf of the native races” and for confronting the evils of slavery, racial prejudice, opium trafficking and addiction.[59] While the stated objective of the LMS was “to spread the knowledge of Christ among heathen and other unenlightened nations” and to do so without regard to denominationalism, LMS missionaries confronted social and cultural evils whenever and wherever they encountered them. While they generally stayed out of local politics and governance, they believed that “if the government of a country allies itself with cruelty, social wrongs, and oppression, the Christian missionary, working within the sphere of such government, must find himself in active opposition to such things.”[60]

Gradually the proselytizing efforts of the LMS in Africa moved northward through the efforts of Rev. Robert Moffat at Kuruman, a missionary outpost in South Africa north of the Orange River, eventually culminating in the multiyear explorations and evangelical efforts of the famed Scotsman Dr. David Livingstone (1813–73). Both Kuruman and Livingstone were anxious to rid Africa of the slave trade. During Livingstone’s expeditions across Africa from the Atlantic to the Indian Oceans, and later northward into the African interior in search of the source of the Nile, he identified twenty-eight previously unknown tribes. He died of malaria at the village of Ilala in Zambia in central Africa years later in 1873 and today lies buried in Westminster Abbey. In America the Calvinist-oriented Boston Mission, or American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), began in 1810 and concentrated its early efforts on Native Americans and on Hawaiians, with its first missionaries disembarking there in the spring of 1820.

David Livingstone, by Thomas Annan

David Livingstone, by Thomas Annan

What turned the attention of the LMS to the Polynesian Islands (literally meaning “many islands”) was a combination of several factors. These included Carey’s own interests in the region; the Reverend Henry Nott’s (1774–1844) recent proselyting successes in Tahiti; the tragic death of Captain Cook in Hawaii; “its conflicting if not mysterious scenes of incredible beauty, adventure and human degradation”; the success of the Wesleyan Missionary Society in Tonga, Australia, and New Zealand; and concern over a renewal of post-Revolution, French-sponsored, Roman Catholic missionary endeavors.[61]

After sailing 13,820 miles aboard the sailing ship Duff, Rev. Nott first set foot on the island of Tahiti on 5 March 1797, along with twenty-nine other missionaries. A bricklayer by trade, Nott applied himself to learning the native language and to teaching the gospel without ceasing, refusing to give up when many of his minister colleagues became discouraged and returned home. A natural peacemaker, he negotiated a remarkable peace between warring tribes in the island of Tutuai. Nott’s greatest breakthrough came in 1813 with the conversion of Otu, King Pōmare in 1813 and his victory over the island’s pagan chiefs. Pōmare’s conversion resulted in the eventual Christianization of most of Tahiti, the destruction of pagan temples and of the pagan idol Oro, and erection of the 730-foot-long, 54-foot-wide Royal Mission Chapel at Papaoa, which opened in 1819. Pōmare baptized some five thousand of his people in June 1819, and Christian churches and chapels began springing up all over Tahiti. Before Nott’s death of a stroke in 1844, he had translated the entire Bible into Tahitian. The islanders’ rapid conversion to Christianity persuaded many of the missionaries as well as the native populations that the Polynesians descended from the ten tribes of Israel.[62] Tahiti remained in English hands until the time of the French interventions in 1838 and the coming of large numbers of Roman Catholic priests. Even though Tahiti became a French protectorate in 1847, much of Protestantism has endured there to this day.

“We Must Branch Out to the Right and Left”

We must now return to our “apostle of Polynesia. Nott’s impressive success inspired young John Williams to apply to serve in the LMS in the first place. “A man of restless energy, of sunny temperament, of strong self-confidence, of bold initiative, [and] of resolute faith,” Williams and his wife, Mary, arrived in Tahiti on 16 November 1817, twelve long months to the day after leaving England’s shores.[63] Two months later their first child, a boy, was born, one of the first European babies born in Tahiti. Mary found companionship with the wives of other missionaries and tried to adjust to raising a newborn and living a half a globe away from home. Mail took months to arrive, and a twenty-week-old newspaper was about as current as could be expected.

Unlike Rev. Nott, who had confined himself throughout his forty-seven years of missionary service almost exclusively to Tahiti, Williams was a restless sort who would spread his nets wide across the many islands and vast distances of Polynesia. “I never considered [Tahiti] alone as worthy of the lives and labours of the number of missionaries who have been employed there,” he later wrote. “I cannot content myself within the narrow limits of a single reef,” and “we must branch out to the right and left.”[64] Oftentimes called the ironmonger apostle, “the apostolic skipper,” and “Polynesian apostle,” Rev. Williams would spread the Protestant Christian gospel from Tahiti and Raiatea of the Society Islands and other islands of what today is French Polynesia to the Samoan (Navigator) Islands, where his pioneering missionary efforts reached crowning success.

Williams and his wife knew full well the dangers they were up against. The work of converting these peoples was challenging. A highly intelligent, remarkably curious, cheerful, and inquisitive people, the natives of these many islands had accumulated over the centuries many customs that were strange and offensive to Europeans. Oro, the god of war, seemed to rule everywhere, at least in the Society Islands, and his priests delighted in offering human sacrifice. Their constant interisland wars, which lasted with atrocious vengeance from one generation to the next, featured wholesale massacres at sea or on land and human dismemberment, with captives slain and cannibalized on the spot or burned alive in giant bonfires. One of the great evils of the islands was the existence of Ono, a systematic revenge for the killing of a family member. “It was a legacy bequeathed from father to son to avenge that injury, even if an opportunity did not occur until the third or fourth generation.”[65]

The idolatry of these islands was fearful and legendary. The creator god was Tangaroa, sometimies called Taaroa, or Taau, god of thunder. There were deities of snakes, lizards, dogs, and almost every other creature on land and in the sea—be it turtles, sharks, and even eels. To appease the anger of these myriad divinities, human sacrifice or disfigurements often took place in their island temples, or marae. Each island had its own oracle or priestly class to divine the will of the gods through their incessant prayers or ubu, chants and drum beating. Witchcraft and sorcery were also common, as were divinations and exorcisms.[66]

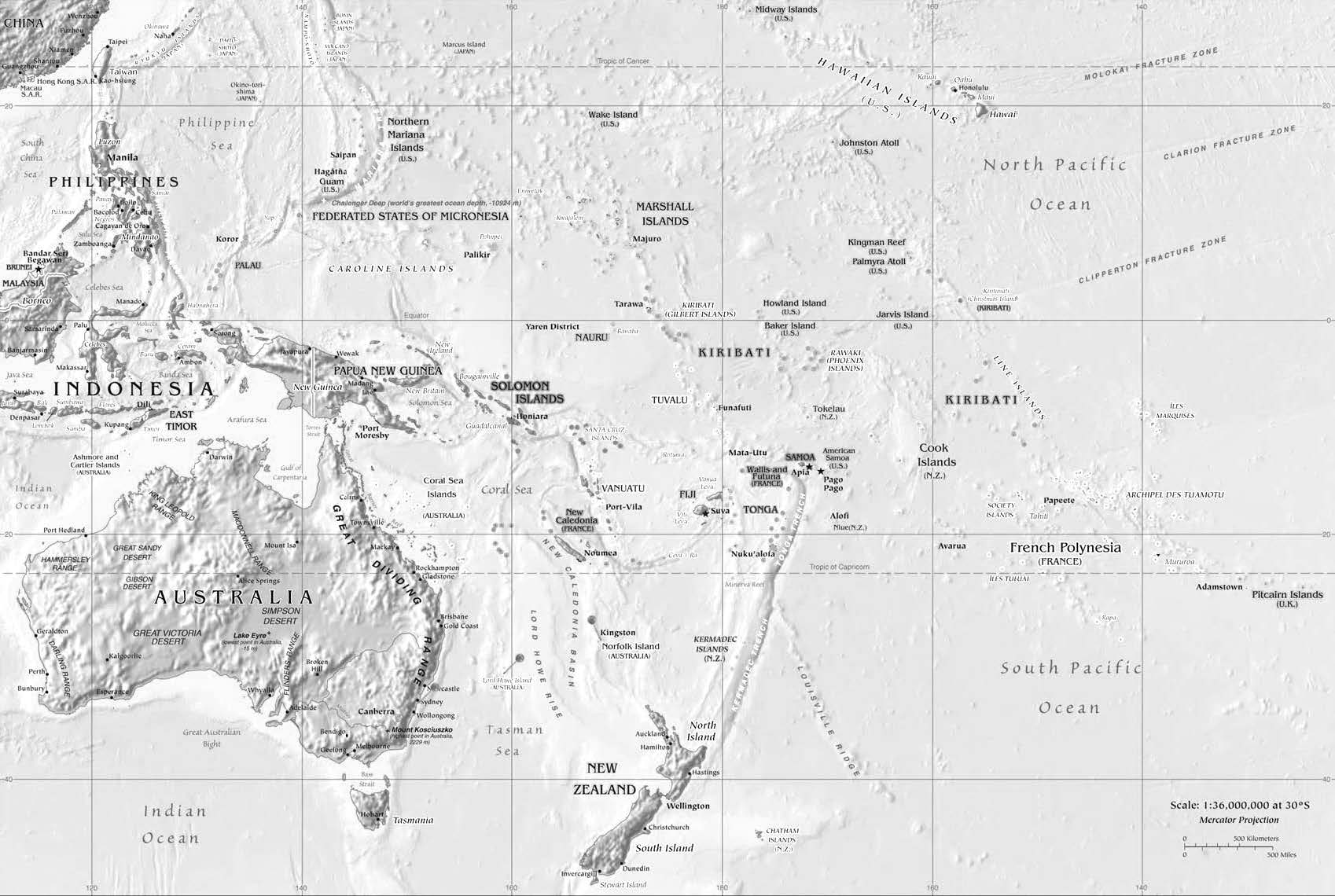

A Map Covering Most of Oceania. Courtesy of Cental Intelligence Agency.

A Map Covering Most of Oceania. Courtesy of Cental Intelligence Agency.

These islands were as beautiful as they were dangerous and unpredictable. Many of Williams’s missionary colleagues disappeared, either at sea or on land. Others of the less courageous makeup gave up and returned with their families to England. The natives’ social customs and codes of conduct could be harsh. Thieves caught in the act were sometimes cut in pieces and their limbs hung up in different parts of the kainga, or farm. Even young children caught stealing could be thrown into the sea with a heavy stone attached to one or both legs. The sick and the elderly were often buried alive because they were seen as a troubling nuisance.

On some islands, women were considered to be a necessary evil. As Williams described it, “Females were looked upon as so polluting, that they were never allowed to enter the sacred precincts (idol temples); and even the presence of the pigs in the enclosure was not considered so dreadful a desecration as that of women.”[67] Immorality and polygamy were rampant. Many of a chief’s young polygamous wives were purchased, and “if a sufficient price is paid to the relatives, the young woman seldom refuses to go, though the purchaser be ever so old and unlovely.”[68] Many older wives were abandoned. In Fiji when a chief died, all his wives were executed one by one, much like the custom of Suttee in India.

Abortions and infanticide were considered to be among the worst of the practices. In a society and culture that emphasized violence and criminality and minimized conscience, such atrocities were especially rampant in the Society and Georgian Islands. Mothers would sometimes kill their own children if they and their husbands were of inferior rank one to another, if the nursing of a child was seen as reducing a mother’s beauty, or if they feared their children would be killed or sacrificed as a by-product of an impending war. They would either break their bones and limbs and bury them alive in a hole or else strangle them to death. There are accounts of many women who had killed at least five of their own children. One woman killed sixteen of her children. Such atrocities particularly bothered Mrs. Williams, who worked to improve their style of dress and morality and to abandon violent practices.[69]

As frightful as many of these customs were to the eyes of these early missionaries, they were made worse by runaway sailors and escaped convicts (beachcombers) who performed “incalculable mischief.” Their acts of murder, kidnapping, cruelty, and “harbour prostitution” made the missionary efforts all the more difficult. They spread a religion of a very selfish and destructive kind. Ship captains of one nation or another often unloaded barrels of alcohol of every variety in exchange for booty and to buy the support of one tribe or another in interior island conflicts. John and Mary Williams despised these beachcombers and fought to lessen their damaging influence.[70]

Rev. Williams employed many of the proven tactics of the more successful missionaries of the LMS, plus several of his own variety. Like William Carey in India, Williams had a remarkable aptitude for learning the native languages and possessed an unfailing memory. An intense observer, he astounded even the natives by how quickly he learned the inflection and accentuations of their languages and dialects, which, at least west of the Melanesia Islands, bore a striking similarity one to another. He soon was sermonizing in their languages, and translated the scriptures into native languages. He taught in their new Christian schools and introduced new and more powerful medicines. He also taught them of the advances in agriculture and showed them new crops to grow—sugar and tobacco—but how to make the necessary tools to plant and harvest their crops. A definite hands-on kind of educator and minister, he delivered many of his best sermons at the plow rather than the pulpit. He taught with scythe as well as scripture and carried within him an uncommonly deep respect for the island culture and people, their native cheerfulness, trusting disposition, and sense of gratitude. He appreciated their unbounding curiosity, inquisitiveness, and strong intelligence; their eagerness to learn and to improve; and their native humility. Because of such endearing qualities, wherever he sailed, he soon came to be loved and respected.

Williams did not stay long in Tahiti. Perhaps the work done there by Rev. Nott, their file leader, left little room for a young, ambitious soldier of the cross. Williams and his young family sailed to a new field of endeavor in the island of Raiatea in September 1818, with its magnificent natural harbor and two-thousand-foot-high, cloud-enshrined mountains rising majestically from the blue watery carpet of the surrounding sea. Recently devastated by plague and epidemic, Raiatea was particularly disposed to hear of a powerful religion.

Though Raiatea had been the center of the worship of Ono and of human sacrifices, King Tamatoa had already met Rev. Williams and invited him to come. Soon after arriving, Williams set about erecting a fine new dwelling house for his wife and family unlike anything the islanders had ever seen before. It was sixty by thirty feet with seven rooms and their own handcrafted furniture. The natives loved to visit and have tea. The women were as impressed with Mary’s long dresses and sunbonnets as the men were with Rev. Williams’s feats of carpentry. Once Williams had finished the house, he went to work teaching the islanders the practical gospel of mechanical arts: carpentry, smithing, plastering, and other aspects of house building as well as gardening. The natives learned these newfound skills quickly. Williams knew that a new house was as good as a homily in changing old ways. He lived by the motto “Expect great things and attempt them.”[71]

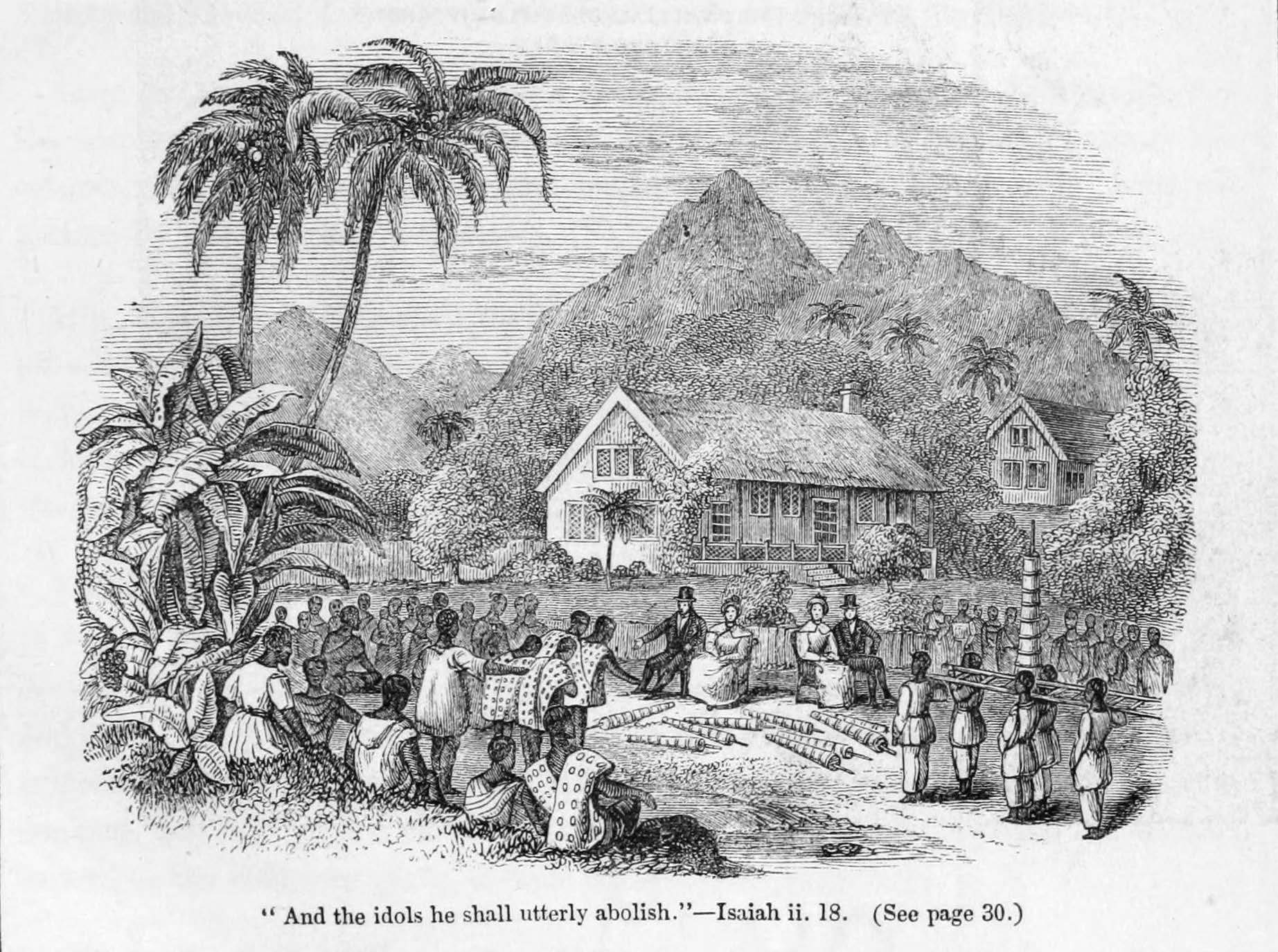

The Reverend John Williams and his wife watching as natives give up their idols. From Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, engraving by George Baxter.

The Reverend John Williams and his wife watching as natives give up their idols. From Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, engraving by George Baxter.

Williams taught his new island friends not only mechanical skills but also how to read and write in the best Sunday School tradition. Attendance at their Sabbath sermons and Bible-reading services Sunday morning and evening significantly increased, and many learned English by ponderously reading aloud the Gospel of Luke. Williams and his wife both loved to sing, and hearing the islanders sing “Abide with Me” was a new experience. Although he sermonized from the Christian gospels, Williams followed LMS policy in not establishing new codes of laws or imposing a new political system in his growing number of followers. He keenly sensed the delicate balance between teaching a new religion and imposing a new political order.[72] However, he did teach about the Decalogue and the Bible, a new respect for life, and other important laws prohibiting criminal and unduly cruel behavior. In this broader sense, he became one of “the legislators of the islands.”[73]

To accommodate his growing number of followers, Williams next did what was characteristic of most LMS missionaries: he constructed a chapel. With the help of many of the natives, anxious to show off their new skills, he built a massive 191- by 44-foot chapel with strong pillars, pulpits, and glorious candle-bearing chandeliers in the winter of 1819–20. At its opening on 11 May 1820, 2,400 Raiateans crowded in, and hundreds of them were soon baptized. The birth of the Williams’s second child that same season gave cause for the entire island to celebrate, with women bearing so many gifts of coconuts and plants to Mrs. Williams that their home could not contain them all.

A particular attraction of Christianity to the Polynesians was the Christian doctrine of redemption of sin and the common belief in the afterlife . “The fate of their departed ancestors was to them a subject of painful interest. ‘Have none of the former inhabitants of these islands gone to heaven?’ many often asked.”[74] Indeed, one primary reason for tattooing was to perpetuate the memory of a beloved and departed relative.[75]

Leaving Mary in Raiatea and having established a winning pattern, Williams sailed to Ruruta in 1821, where he met a supreme test. The local priests invited William to a large feast. Feeding pork, turtle, and other substances of unknown content to the guests, the priests predicted some would die, especially those sitting at unknown, prearranged seating places. Those who sickened, would themselves be sacrificed and eaten. However, if no one sustained any injury or illness, they would destroy their idols. “They met accordingly; and after satisfying their appetites without any injuries being sustained, they arose; boldly seized their gods; set fire to the three sacred houses, the residences of their godships; and then proceeded to demolish the maraes.”[76] Relieved and highly encouraged, Williams promptly set about building a new Christian chapel.

Still, not all of their news that year was good. Their worst sadness that year was the unexpected death of their second child, a devastating blow especially for Mary, who was growing weary of her husband’s island hopping. Later that year, William visited the island of Aitutaki, pressed noses with the chiefs, and told the islanders of the overthrow and destruction of Raiatea’s gods. Convinced that Williams’s god was more powerful than all their idols, the natives of Aitutaki proved especially receptive to the Christian gospel, in part because of Williams’s particularly effective evangelizing tactic of leaving behind indigenous island mission teachers as pastors to teach their own people.[77]

With the death of his mother in 1819, Williams had used part of her estate to purchase a boat in Sydney, New South Wales, which he named the Endeavor, in remembrance of Captain Cook. While still recovering from giving birth to her second stillborn child, Mary joined her husband on yet another Christian conquest in 1823, this time to Rarotonga. Kindly received by King Makea as a healer and builder, Williams went right to work erecting another massive chapel as big as the Royal Chapel at Tahiti. Built without nails or any ironwork, it was large enough to accommodate three thousand new converts.

The Rarotongans soon learned to love their island apostle. His biggest obstacle proved not to be the islanders but the LMS itself. Somehow persuaded that Williams was becoming more of a merchantman than a missionary, his overseers demanded that he surrender his ship, which he had no choice but to do. His wife firmly at his side, Williams felt that he was misunderstood. After two years in Rarotonga, he hoped to set sail aboard the next vessel for Samoa in the Navigators’ Islands. This time, Mary demurred. Not one to complain, she felt she could go no further. “How can you suppose that I can give my consent to such a strange proposition?” she asked. “You will be 1800 miles away, six months absent, and among the most savage people we are acquainted with; and if you should lose your life in the attempt, I shall be left a widow with my fatherless children, 20,000 miles from my friends and my home.”

No doubt such pioneering missionary work took its toll on marriage and family life. Although the LMS pursued a policy of married couples going out together, such service was extremely demanding. William Carey’s wife lost her mind; other wives became alcoholics; not a few returned homesick and heartbroken to England. Education for missionary children was always a grave concern.

One particular trial bears mentioning. Although an island of exquisite beauty, Rarotonga was overridden with rats. There were so many of them that when eating, two or more people had to knock them off the table. When kneeling in family prayer, the Williamses had to fight off rats that would run over them from all directions. They reported, “We found much difficulty in keeping them out of our beds.”[78] One night the rats even devoured Mary’s shoes. The infestation continued until Williams brought back from a nearby island a shipload of cats and hogs that in short order decimated the rat populations.[79]

Mary soon came down with a terrible fever and took deathly ill. Miraculously, she recovered. In her still faithful way, she chose to see it as a sign, a trial sent from God for her stubbornness. Turning to her husband, who had put off his Samoan plans indefinitely, she said, “From this time your desire has my full concurrence; and when you go, I shall follow you every day with my prayers, that God may preserve you from danger, crown your attempt with success, and bring you back in safety.”[80]

Buoyed by his wife’s support and confidence, and waiting in frustration for a passing ship that would never dare come to such a feared island, Williams set upon a new course of action. He resolved, in Robinson Crusoe fashion, to build one himself. Applying all the iron-making, woodworking, and other mechanical skills he had ever learned, the resourceful Williams crafted a set of bellows out of goatskins, a variety of machine pumps, a lathe, pincers, tongs, rope-spinning machinery, cordage, sails, oakum, pitch, paint, anchors, and rudder. With iron in short supply and a lack of saws and nails, he used wedges to split the wood and wooden pins or treenails to fasten boards together. For sails, he used the mats on which the natives slept. Fortunately, he had his own compass and quadrant. To the fascination and delight of the native islanders that winter of 1827–28, who rushed to help him out and called it all “godly mechanicks,” the new ship-builder of Rarotonga fashioned in three months’ time a seaworthy vessel of some fifty to sixty tons’ displacement that he christened the Messenger of Peace. Some of his amazed missionary colleagues preferred to see it as “the finger of God.”[81] In evaluating his success, Williams later provided this insight: “There are two little words in our language which I always admired, try and trust. You know not what you can or cannot effect, until you try; and if you make your trials in the exercise of trust in God, mountains of imaginary difficulties will vanish as you approach them, and facilities will be afforded you never anticipated.”[82]

The Williamses’ return to Raiatea in 1828 was not without disappointment: the death of yet another infant child. Leaving Mary behind but with her support, Rev. Williams finally realized his long-standing dream of spreading the gospel to the Samoan Islands. With few, if any, of the idols and temples with the reputation for cruelties and human sacrifices, Samoa was a favored destination. The absence of a priestly hierarchy (unlike Tahiti) worked to Williams’s advantage. And as fortune had it, the leading antagonist chief against Christianity died just days before Williams disembarked. The new chief, Malietoa, welcomed him and allowed him to preach his message. The result was that “a wide and effectual door was here opened for the gospel.”[83] Rev. Williams’s successful work in converting virtually the entire Samoan Islands was no less an accomplishment than what Nott had done previously in Tahiti and will ever remain Williams’s crowning missionary achievement.

After seventeen years in the islands, John and Mary and family returned to England for two years to reacquaint themselves with family, write, publish a book of their missionary experience, buy a bigger boat, and complete the translation and printing of the Bible into the Rarotonga tongue. They also used this opportunity to raise much-needed funds from selling the book and lecturing throughout Great Britain on their experiences. Little did they know that this would be the last time John Williams would see England.

The Williamses returned to Rarotonga in February 1839 on board the Camden, a much bigger ship that the islanders, eagerly awaiting their return, promptly renamed “the praying ship.”[84] Williams’s determination was to move to the islands further west to proselyte in the New Hebrides because he was convinced they were the key to successfully proselyting New Caledonia, New Guinea, and the whole of western Polynesia.

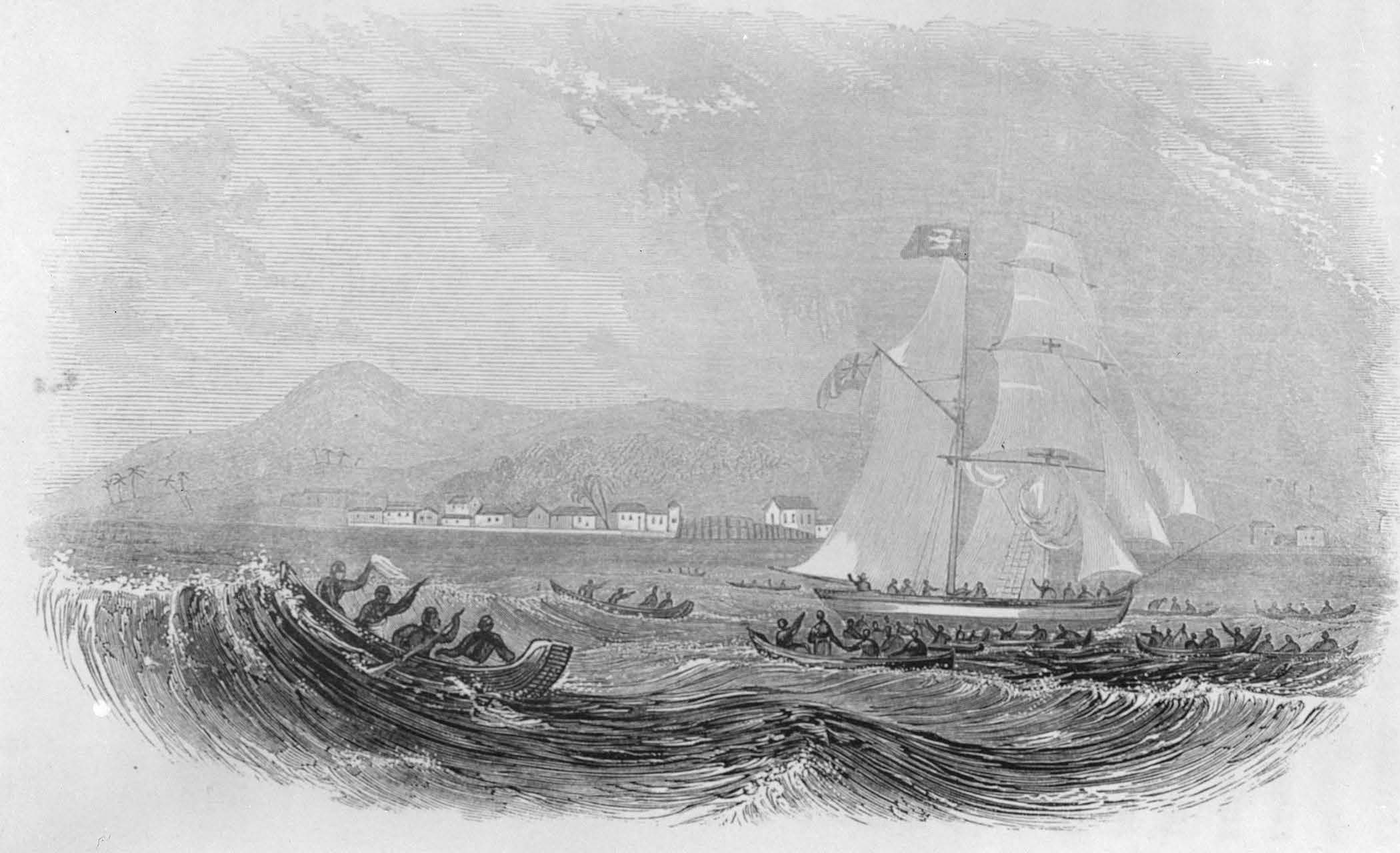

The Messenger of Peace Leaving Aitutak (London, Snow, 1837), engraving by George Baxter.

The Messenger of Peace Leaving Aitutak (London, Snow, 1837), engraving by George Baxter.

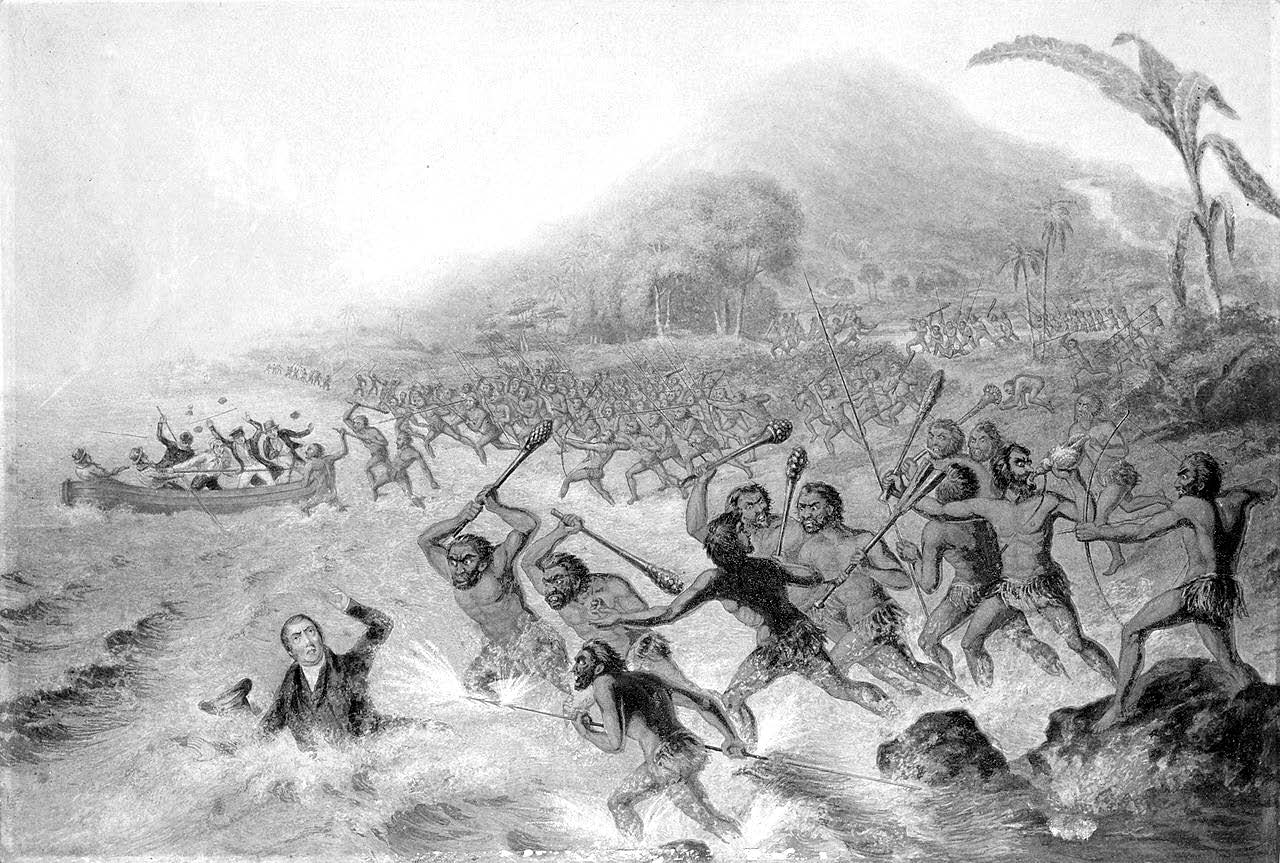

His dream never materialized. On 20 November 1839, while on a surveying mission to the island of Erromango, an island in Vanuatu, everything began to go terribly wrong. The islanders there spoke a language Williams did not know and were very shy and of a more untrusting demeanor. Not long before, European traders in search of sandalwood had invaded the island and committed several atrocities against the natives, particularly the women. Sailing on a small whaleboat to the shore, Williams noticed yet another ominous sign: the absence of women, who almost always were made absent when hostilities seemed imminent. He and a missionary companion, Mr. Harris, disembarked and attempted to give their presents to their frowning hosts. Suddenly, a large number of shouting islanders charged out from behind the trees, setting the two men scrambling for the sea. Both were brutally clubbed before being pierced with several arrows, their blood staining the sandy shoreline. A distraught Captain Robert C. Morgan and the other sailors aboard the Camden were powerless to help and could not even retrieve the bodies, which were soon stripped and hauled inland. Three months later, Captain Morgan returned on board The Favorite, a British man-of-war, to recover their bodies, only to learn the sordid tale that the islanders “had devoured the bodies, of which nothing remained but some of the bones.”[85] Wrote Captain Morgan in his ship’s log: “Thus died a great and good man, like a soldier standing to his post: a heavy loss to his beloved wife and three children. He was a faithful and successful laborer among the islands of these seas. . . . I have lost a father, a brother, a valuable friend and advisor.”[86]

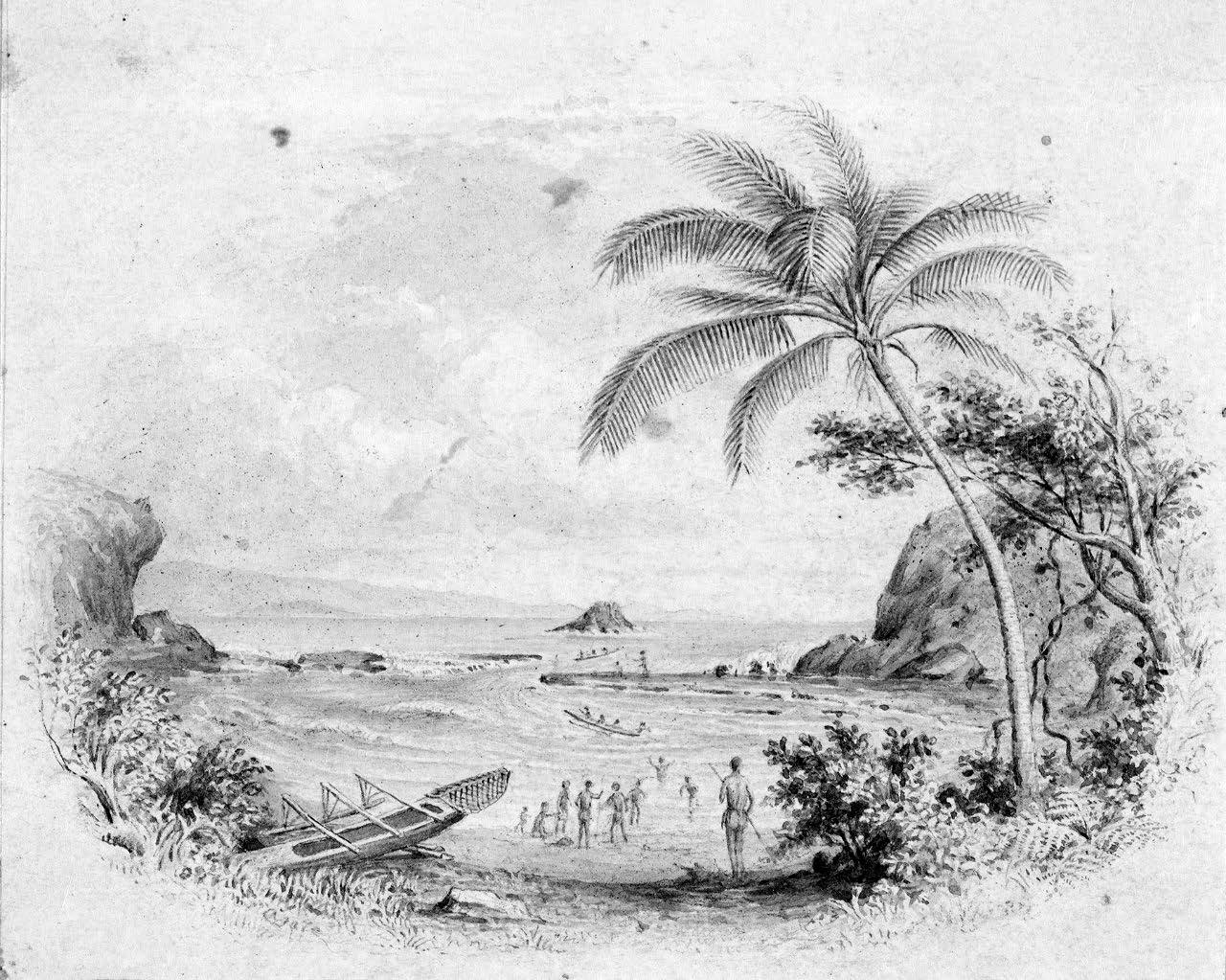

Apolima Island, Samoa, by Alfred T. Agate (ca. 1840). Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command.

Apolima Island, Samoa, by Alfred T. Agate (ca. 1840). Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command.

The news of his tragic death devastated his wife and children and set the islanders of Samoa, Rarotonga, Raiatea, Hitataki, and a score of other islands into an extended period of sorrow and mourning. Gone was their teacher and guide, their missionary friend and builder, their kind exemplar and devoted servant. At his wife’s instructions, his few remains were buried in Apia, Samoa. She eventually returned to England, a sad and lonely woman who died faithful to the Christian cause in 1852, two years after the first Latter-day Saint missionaries arrived in the Sandwich Islands.

The pioneering efforts of men and women like John and Mary Williams paved the way for the later arrival of the Latter-day Saint missionaries. Latter-day Saint historian Fred E. Woods may have summed up their contributions best:

Although there was a vying for native converts, the LDS missionaries benefited from the preparatory work of the LMS, which had launched Christianity in this region at the end of the eighteenth century. Further, primary evidence reveals that although there was certainly friction between representatives of these two denominations, some degree of mutual respect occurred when the missionaries from each party discussed their personal beliefs while meeting in private. . . . Surely the Mormons recognized how LMS work laid the groundwork for their own, just as Paul wrote: “I have planted, Apollos watered; but God gave the increase” (1 Cor. 3:6).[87]

The fire of religious fervor that characterized our age of 1820 found expression in hundreds of different kinds of improvement societies that sprang up almost spontaneously, first in Great Britain and then later in America and elsewhere. This chapter has emphasized three kinds of Christian societies in particular that wielded such astonishing influence worldwide that their story had to be told: the religious tract societies, the British Foreign Bible Society and its Americana counterpart, the American Bible Society, and their incredible success in disseminating scripture, and most noteworthy the London Missionary Society. Their efforts led to millions of people having copies of the Holy Bible in their home, and may even have resulted in the Joseph Smith family having one such set of scriptures at their kitchen table.

The Massacre of the Lamented Missionary the Rev. J. Williams and Mr. Harris, by George Baxter (1841).

The Massacre of the Lamented Missionary the Rev. J. Williams and Mr. Harris, by George Baxter (1841).

Yet it was the faith and sacrifice of men and women like the faithful Rev. John Williams, the “apostle of Polynesia,” and his devoted wife, Mary, who really made it happen. Their proselytizing efforts among the islanders struck a responsive chord. They were particularly successful because they taught practical skills as well as religious convictions, because they respected island culture while teaching them new ways of behavior, and because they loved and were loved in return.

Notes

[1] Williams, Narrative of the Missionary Enterprises, 12–13.

[2] Williams, Narrative of the Missionary Enterprises, 14.

[3] Herbert, Culture and Anomie, 165. Herbert continued: “Despite the ambition to inculcate right beliefs, deeds—and the passage from one set of practices to another was the only markers available for missionaries to gauge conversion. In fact, missionaries spent far less time worrying about beliefs than they did regulating conduct.” Culture and Anomie, 58.

[4] Maffly-Kipp, “Assembling Bodies and Souls: Missionary Practices on the Pacific-Frontier,” in Maffly-Kipp, Schmidt, and Valeri, Practicing Protestants, 62–63, 71.

[5] Conroy-Krutz, Christian Imperialism, 15. To be Christian, he insisted, “one had to be civilized” (210).

[6] “The cultural-imperialist narrative . . . has not yielded fruitful explanation for why non-Western resisters embraced Christianity with such confounding enthusiasm that they now outnumber the Western imposters.” Case, Unpredictable Gospel, 5.

[7] Williams, Narrative of the Missionary Enterprises, 2.

[8] Prout, Memoirs, 9.

[9] Prout, Memoirs, 8, 13–14.

[10] Prout, Memoirs, 23.

[11] Brown, Fathers of the Victorians, 317.

[12] Brown, Fathers of the Victorians, 350.

[13] The Weekly Recorder (London), 9 February 1820.

[14] The Weekly Recorder (London), 16 February 1820.

[15] Brief History of the Organization and Work of the American Tract Society, 5–10.

[16] Canton, History of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1:466. See also Owen, History of the Origin and First Ten Years, 15. The above famous account was first published in the Bible Society’s Monthly Reporter, January 1867.

[17] The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge had distributed some copies of the Bible in England, Wales, India, and Arabia. In 1701 the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts commenced, with special emphasis on the American Colonies. The year 1750 saw the startup of the Scottish Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge Among the Poor, and in 1780 the Naval and Military Bible Society began. See The Catholic Encyclopedia, New Advent, http://

[18] Browne, History of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1:10.

[19] Canton, History of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 2:359.

[20] Canton, History of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1:318.

[21] Howsam, Cheap Bibles, 6.

[22] Within fourteen years of the establishment of the British and Foreign Bible Society, the following societies had been organized in imitation of the BFBS: the Basel Bible Society (Nuremberg, 1804), the Prussian Bible Society (1895), the Swedish Evangelical Society (1808), the Dorpat British Society (1811), the Riga Bible Society (1812), the Finnish Bible Society (1812), the Hungarian Bible Institution (1812), the Russian Bible Society (1812), the Swedish Bible Society (1814), the Danish Bible Society (1814), the Saxon Bible Society (1814), the Hanover Bible Society (1814), the Netherlands Bible Society (1814), the American Bible Society (1816), and the Norwegian Bible Society (1817). By 1817 these societies had printed 436,000 copies of the scriptures (Bibles and testaments) and had received gifts of sixty-two thousand volumes from the parent British and Foreign Bible Society. See “Bible Societies,” https://

[23] As one early historian of the society put it, “This augmented demand for the English Scriptures [in Britain] was stimulated by the discoveries successively made of the want of them existing in a degree that could hardly have been conceived.” Strickland, History of the American Bible Society, 55.

[24] Despite the fact that the pope issued a bull against Bible societies as a weapon of Protestant evangelism that was “immensely dangerous to the faith,” many Catholics supported local Bible society initiatives. “Religious Intelligence,” American Monthly Magazine and Critical Review (New York) 1, no. 3 (July 1817): 202.

[25] From the 16th Report of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 102, as cited in Howsam, Cheap Bibles, 53. Whenever possible, the societies sought to sell their Bibles, rather than merely give them away.

[26] Browne, History of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1:76.

[27] As one bishop lamented, “Half the population of the labouring classes in the metropolis of the British Empire were destitute of the Holy Scriptures.” Browne, History of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1:60.

[28] Howsam, Cheap Bibles, 79.

[29] Remembrancer, 22 January 1820, 88. Serious consideration was early on given to translating into the languages of India; however, the East India Company was for many years resistant to missionary work and Bible distribution for fear of possible revolt. See Browne, History of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1:166–72, 273.

[30] As Briggs put it, “The wars against France reinforced the movements for the reformation of manners and the enforcement of a strict morality; in many ways they widened the ‘moral gap’ between Britain and the Continent, as much as they widened the economic gap. . . . Only moral standards, supported by ‘vital religion’ were guarantees of social order, national greatness, and individual salvation.” Briggs, Age of Improvement, 172.

[31] Evangelical Recorder, 31 January 1818, 1. And from another, writing in February 1820: “We are labouring in a pacified world! The sword is beaten into the plough share, and the spear into the pruning hook. . . . The spirit of enterprize, nurtured in a protracted contest, is bursting forth in the discovery of new nations. The relations of Commerce, broken by war, are renewed; and are extending themselves on all sides. Every shore of the world is accessible to our Christian efforts. The civil and military servants of the Crown throughout its foreign possessions . . . are freely offering their labour and their influence to aid the benevolent designs of Christians. . . . Let us offer, then, as we have never yet offered. Let us meet the openings of Divine Providence.” From “Extract from the 10th Report of the Church Missionary Society.” Remembrancer, 12 February 1820, 99.

[32] From a speech by The Right Hon. Lord Teignmouth, President, at the Sixteenth Anniversary of the Society, 3 May 1820, Sixteenth Report of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 223, 225.

[33] From a speech by The Right Hon. Lord Teignmouth, President, at the Sixteenth Anniversary of the Society, 3 May 1820, Sixteenth Report of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 223, 225.

[34] “List of Contributing Institutions,” Mundus: Gateway to Missionary Collection in the United Kingdom, http://

[35] Jackson, “Joseph Smith’s Cooperstown Bible,” 41. For an excellent study of the history of the Bible in America, see Gutjahr, American Bible.

[36] Dwight, Centennial History of the American Bible Society, 3.

[37] Daniell, Bible in English, 594–96, 598–99, 627–29.

[38] For a comprehensive and detailed study of the various American Bible editions, see Hills, English Bible in America.

[39] Daniell, Bible in English, 639.

[40] Dwight, Centennial History, 85. It may be worth noting that the Bible, “which fed the soul of Abraham Lincoln in the Kentucky log cabin of his boyhood, was one of those cheap little Bibles imported from London” (3).

[41] Lacy, Word-Carrying Giant, 50. See also Dwight, Centennial History, 84. See also American Bible Society, Brief Analysis of the System of the American Bible Society, 45. The following report is from an agent in Long Island, New York: “I am confident no region will be found in a Christian land where Bibles are more needed. There are here multitudes of people but just able to live, and who live and die almost as ignorant of the gospel as the Heathen. Many observe no Sabbaths, enjoy no religious ordinances, and have no religion, and they value them not, for they have no Bibles.” Lacy, Word-Carrying Giant, 41.

[42] Lacy, Word-Carrying Giant, 49.

[43] “The First Annual Report of the Board of Managers of the American Bible Society, presented May 8, 1817.” Evangelical Guardian and Review (New York), July 1817, 137.

[44] Strickland, History of the American Bible Society, 31.

[45] Lacy, Word-Carrying Giant, 51.

[46] Few, Bible Cause, 28.

[47] Few, Bible Cause, 52.

[48] “First Report of the American Bible Society, Presented at the Annual Meeting, May 10, 1821.” Methodist Magazine, August 1821, 312.

[49] Brief Analysis of the System of the American Bible Society, 33.

[50] Dwight, Centennial History, 521.

[51] Kane, Concise History of the Christian World Mission, 83.

[52] Ngapkynta, William Carey, i.

[53] Ngapkynta, William Carey, 105.

[54] Kane, Progress of World-Wide Missions, 59.

[55] Lovett, History of the London Missionary Society, 1795–1895, 2:422. Of the religious persecutions in China, the following 1815 letter from a Catholic missionary there affords some details: “Every European priest that is discovered, is instantly seized and put to death; Chinese Christian priests undergo the same fate. Christians of the laity, unless they will apostatize, are first dreadfully tortured, and then banished. . . . This year, in the prisons of one province alone, (Sutchen) two hundred Christians were expecting the orders for their exile. A Christian Chinese priest has just been strangled, and two others were also under sentence of death.” “Persecution in China,” American Masonic Register 1, no. 1 (September 1820): 73.

[56] A man of encyclopedic interests and one who respected other faiths, Morrison also translated Buddha’s biography from Chinese into English: entitled Account of Foe: The Deified Founder of a Chinese Sect. This translation, published in 1812, gave Europeans a direct sense of the religion and contributions of Buddha in a biographical setting. See Wu and Wilkinson, Reinventing the Tripitika, 12.

[57] Lovett, History of the London Missionary Society, 2:337–45.

[58] Wallbridge, Demerara Martyr.

[59] Lovett, History of the London Missionary Society, 2:541.

[60] Lovett, History of the London Missionary Society, 2:544.

[61] Smith, History of the Establishment and Progress, 108. Peru had sent Catholic missionaries to Tahiti in the early 1770s but with little effect.

[62] Koskinen, Missionary Influence as a Political Factor in the Pacific Islands, 101–2.

[63] Lovett, History of the London Missionary Society, 2:238.

[64] Lovett, History of the London Missionary Society, 2:254, 378.

[65] Williams, Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, 64.

[66] Smith, History of the Establishment and Progress, 60–97.

[67] Williams, Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, 83.

[68] Williams, Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, 91.

[69] Prout, Memoirs, 280–90. See also Williams, Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, 65–83.

[70] Williams, Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, 119–20.

[71] Prout, Memoirs, 68.

[72] Williams, Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, 36–37.

[73] Koskinen, Missionary Influence, 58.

[74] Smith, History of the Establishment and Progress, 222.

[75] Williams, Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, 139–40.

[76] Lovett, History of the London Missionary Society, 252.

[77] Boutilier, “‘We Fear Not the Ultimate Triumph,’” in Miller, Missions and Missionaries in the Pacific, 38–39. “Indigenous Christians, not the missionaries, were the experts.” Case, Unpredictable Gospel, 8.

[78] Williams, Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, 40.

[79] Williams, Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, 40.

[80] Williams, Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, 37–38.

[81] Prout, Memoirs,176. See also Boutilier, “‘We Fear Not the Ultimate Triumph,’” 34.

[82] Williams, Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, 93.

[83] Prout, Memoirs, 220.

[84] Prout, Memoirs, 330.

[85] Williams, Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, 394.

[86] Williams, Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, 392.

[87] Woods, “Latter-day Saint Missionaries Encounter the London Missionary Society,” 124.