"An Archangel a Little Damaged"

Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the Romantics

Richard E. Bennett, “'An Archangel a Little Damaged': Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the Romantics,” in 1820: Dawning of the Restoration (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 125‒52.

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.[1]

“If I should leave you restored to my moral and bodily health, it is not myself only that will love and honour you. Every friend I have (and thank God! Spite of this wretched vice I have many and warm ones who were friends of my youth and have never deserted me) will think of you with reverence.”[2] So admitted one of England’s favorite literary sons in April 1816, less than a year after the Battle of Waterloo. What had brought this giant of a critic, philosopher, and poet, this friend of William Wordsworth, Robert Southey, Charles Lamb, and a host of other literary figures of his age, on bended knee to an obscure surgeon at Highgate, North London? And what were the lasting contributions this tortured soul made to our unfolding understanding of the age of 1820?

Portrait of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834), Peter Vandyke.

Portrait of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834), Peter Vandyke.

The careful reader will find much in Coleridge’s late but remarkable conversion to Christianity to stir the soul. Like a C. S. Lewis of an earlier century, his was more than a remarkable transformation: Coleridge was one of the few literary geniuses of his time to proclaim his conversion to the gospel of the New Testament. And he did so in a way that his critics could not easily dismiss. If not the prophet of his age, Coleridge may well have been its poet, writing a modern style of scripture that many are only now beginning to appreciate.

The youngest of thirteen children, Samuel Taylor Coleridge was born 21 October 1772 at Ottery St. Mary in Devonshire. His father, John Coleridge, whom he loved dearly, was a Cambridge graduate, a schoolmaster, and an Anglican vicar who called the scriptures “the immediate language of the Holy Ghost.”[3] “My father was fond of me,” Coleridge remembered, “and used to take me on his knee, and hold long conversations with me. I remember that at eight years old I walked with him one winter evening . . . and he told me the names of the stars, and how Jupiter was a thousand times larger than our world and that the other twinkling stars were suns that had worlds rolling round them, . . . and I heard him with a powerful delight and admiration. . . . From my early reading of Faery Tales and Genii etc. my mind had been habituated to the vast.”[4] Coleridge later called his father a perfect Parson Adams, an allusion to the benevolent character in Henry Fielding’s novel Joseph Andrews.

On the other hand, his mother, Ann Bowden, was an unimaginative, uneducated, and rather strict and distant parent who seemed to begrudge his very existence. Coleridge never found in her the love he yearned to have from a mother. Being part of a very large and lively family, he learned early in life to assert himself. Although six of his siblings died during his childhood, Coleridge developed fortitude and faith in God.

A dreamer and an imaginary, young Coleridge learned early on to love the outdoors and its resplendent beauties through his many nature walks in the nearby countryside, and, though given to books, he was gregarious and amiable and made friends freely. As one later said of him, “He was a creature made to love and be loved.”[5] From all accounts, his was a happy childhood. “Visions of childhood! Oft have ye beguiled lone manhood’s cares, yet waking fondest sighs; Oh! that once more I were a careless child.”[6] But everything changed for the worse when his father died. His penniless mother shipped him off to London to go to boarding school. Mother and son seemed satisfied not to have to live under the same roof and seldom corresponded thereafter. In London, Coleridge’s maternal uncle, a tobacconist by trade, fortunately got him into Christ’s Hospital, a renowned charity school on Newgate Street, founded two hundred years before to educate the orphaned sons of poor gentry. Famous for its blue coats and yellow stockings and its academic rigor and strict discipline, Christ’s Hospital left an indelibly forlorn impression upon the young, untidy, and unkempt scholar, who studied there until age eighteen.

Headmaster Reverend James Bowyer more than once flogged Coleridge, as he did most other boys, for want of this or that—harsh experiences that Coleridge remembered in vivid nightmares for the rest of his life. Yet Bowyer saw in the lad real academic promise, for Coleridge was a veritable “library cormorant”—having already read so much of Shakespeare, Milton, Voltaire, and other great writers. From Bowyer, Coleridge learned that poetry “had a logic of its own, as severe as that of science; and more difficult, because more subtle, more complex and dependent on more and more fugitive causes.” Of the truly great poets, he would say, “There is a reason assignable, not only for every word, but for the position of every word.”[7] Bowyer successfully instilled in Coleridge precision in writing, logical thinking, economy of words, and “a deep sense of [his] . . . moral and intellectual obligations.”[8]

While at Christ’s Hospital, Coleridge “immersed himself in metaphysics and in theological controversy” and found the old poetry of Pope and other eighteenth-century classical writers “insipid, lifeless, and artificial.” Alternatively, the sonnets of Reverend W. L. Bowles, with his love of fancy, nature, and “the sense of beauty in forms and sounds,” impressed Coleridge deeply.[9] Prone to loneliness, Coleridge combined “an advanced intelligence with emotional immaturity.”[10] “There was something awful about him,” a contemporary recalled, “for all his equals in age and rank quailed before him.”[11]

While still at boarding school, Coleridge met Charles Lamb, who was destined to become a lifelong friend, and Tom Evans, who, in turn, introduced Coleridge to his widowed mother and his five sisters. Coleridge soon preferred to spend his weekends and holidays with the Evans family. It was there that he found the maternal love in Mrs. Evans that he never found in Devonshire. Coleridge also soon fell in youthful love with Mary, the oldest Evans daughter, whom he admired “almost to madness.”[12]

Admitted to Cambridge in 1781, Coleridge began attending Jesus College in the fall. Although training to become an Anglican clergyman, he could never quite see himself in that pastoral role. His theology was much freer and more expansive, almost Unitarian, than Anglicanism would allow. He also preferred the spontaneous writing of creative poetry and the company of friends. His room was ever a clutter of conversations. Moreover, his youthful political radicalism set him apart from—if not at odds with—the staunch, conservative Cambridge political and religious culture. Praising the French Revolution and condemning Britain’s war with France at a time in England when it was politically inexpedient to do so, he identified himself with the cry for liberty, equality, and fraternity, a stance which many of his countrymen perceived as radical.

When France in wrath her giant limbs upreared,

And with that oath, which smote air, earth, and sea,

Stamped her strong foot and said she would be free,

Bear witness for me, how I hoped and feared!

With what joy my lofty gratulation

Unawed I sang, amid slavish band.

. . . For ne’er, O Liberty! With partial aim

I dimmed thy light or damped thy holy flame;

But blessed the paens of delivered France,

And hung my head and wept at Britain’s name.[13]

Unhappy and unfulfilled, Coleridge suddenly quit Cambridge, preferring to beg on the streets of London, quoting Greek and Latin to all who would listen. Hungry for food, lodging, and companionship, Coleridge was driven to enlist in the very thing he despised most—the army, specifically, the 15th Company of Dragoons, under the fictitious name of Silas Titus Comberbach (though retaining his initials S. T. C.). As clumsy a horseman as he was gifted a poet, Coleridge would have been laughed to scorn by his illiterate comrades had he not enthralled them with his gift of telling ancient Greek and Roman warfare stories and more especially his skills of writing eloquent love letters to their wives and girlfriends back home. It was also during his four-month stay in the military that he discovered his love for alcohol and for medicine. He spent time bandaging the wounded, caring for those with smallpox, and nursing others back to health. Undoubtedly, he would have made a most capable surgeon. Thanks to his brothers, George and James, Coleridge was able to quit the military in April 1794 after only four months’ service when they bought out his contract. He returned to Cambridge wiser and humbler than before.

Back in school, he met a fellow pupil destined to become a future poet laureate of England who would greatly influence his life—Robert Southey (1774–1843). Like brothers, the two shared much in common ideologically, politically, and poetically. Southey invited Coleridge to his hometown of Bristol and into his circle of influential literary friends and intellectuals, which included George Burnet, Hannah More, Ann Yearsley (the literary milkwoman), Robert Lovell, and William Gilbert. It was in Bristol that Coleridge, spurred on by Southey and his newfound friends, began writing his earliest sonnets.

Southey shared Coleridge’s disdain at becoming a priest; in fact, he was distinctly and radically Unitarian in his Godwinian belief that the real sin in the world was not the Fall of Adam but the depravity of society, the crime of inequity in private property and the consequential social inequality, and the hypocrisy of the judicial system. William Godwin had espoused in his Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793) that humanity was an optimistically good creature who sinned only because of the repressive laws of bad government. What was needed was a new society with entirely different values, a new utopia.

Quite conveniently, Southey introduced Coleridge to his future wife. Southey was engaged to Edith Fricker, and when Coleridge was introduced, he began meeting with Sara Fricker, Edith’s older sister. Within just two weeks they were engaged. Coleridge subsequently married Sara, a clever, stylish, quick-witted young lady, on 4 October 1795 in Bristol’s St. Mary Redcliffe Church, just weeks before Southey and Edith Fricker were married in the same building. Another fellow writer, Robert Lovell, married a third sister, Mary Fricker. Coleridge later described his new wife as “an honest, simple, lively-minded, affectionate woman but without meretricious accomplishments; a comfortable and a practical wife for a man of somewhat changeable temper.”[14]

The young married couple first moved into a small, comfortable cottage but soon relocated to Nether Stowey in Somerset, closer to Bristol, where their first child, Hartley, was born in 1796. While there, Coleridge launched his own weekly literary magazine called The Watchman. Designed to be a commentary on current affairs and parliamentary debates and a forum for his poetry and that of like-minded associates, it provided Coleridege with an opportunity to express his liberal, if not radical, political views, which were often aimed at Prime Minister William Pitt’s foreign policy, and to show off the latest in literature. But the pressures of finding and collecting information, the challenges of composition, and the rigors of meeting publishing deadlines all proved far too daunting a task for a one-man operation. Consequently, The Watchman folded after only ten issues, throwing its proprietor and his family deep into debt. Had it not been for the timely financial assistance from Josiah and Thomas Wedgwood, the famous potters, who admired his poetry and established an annuity for him, Coleridge would have faced bankruptcy.

Such financial blunders became a pattern in his life as he darted from one financial crisis to another, for Coleridge was not so much a mismanager of funds as he was philosophically opposed to accumulating wealth. As Cottle put it in more delicate terms, he was “too well disciplined to covet inordinately nonessentials.”[15] Such financial carelessness put an enormous strain on his marriage because his wife, Sara, never really understood him or appreciated his impracticalities.

Reluctantly, Coleridge came to admit that he was still in love with Mary Evans, whose image was “in the sanctuary of his bosom.”[16] Not surprisingly, he soon found reasons to be lecturing and writing back in London, and only at the persuasions of Southey did he find time to write home. His marriage to Sara was at best a sentimental relationship, a union of duty, and though they would have several children together, they later separated. However, like Tsar Alexander and Elizabeth, they rejoined as friends in much later years.

Romanticism: A Revolution in Literary and Artistic Thought

Literary scholars today place Coleridge squarely in the camp of Romantic poets. As with music and art, Romanticism in literature was essentially a reaction against constraint, against rigid and artificial formalities of style and format. It defied the openly didactic and pedagogical styles of the neoclassical era of Pope, Dryden, and Johnson. It was, as Henry Beers wrote over a century ago, “the effect of the poetic imagination to create for itself a richer environment, . . . a reaching out of the human spirit after a more ideal type of religion and ethics than it could find in the official churchmanship and formal morality of the time.”[17]

More recent commentators, like literary critic Northrop Frye, argue that Romanticism was a “new kind of sensibility,” a new “mythology” in the broadest sense of a paradigm shift in how to view creation. Before, all was seen through the lenses of God as supreme Creator, the Fall of Man, Christ’s Atonement, and mankind’s ultimate redemption. But in the minds of many of the Romantics, humanity is its own agent of creation, not fallen from God but from nature. And redemption comes through a sensory reconnection, as Wordsworth taught, with the beauty, laws, and profundity in nature. It was, in a sense, a new religion no longer tied, as Milton had done, to a moral responsibility. Little wonder that in much of Romanticism on both sides of the Atlantic there were strong strains of deism, Pantheism, Universalism, and Unitarianism.[18]

Romanticism was also a more optimistic view of the nature of humankind than what had been portrayed for centuries. Resisting classical atheism on the one side and rejecting the Calvinist view of man’s total depravity on the other, many Romantic writers believed the beauties and glories of nature attested to an exalted creation, not a fallen one. They also believed in the power of the human will to reason and to overcome afflictions and in the divinity within humankind that was so well expressed in the beauties of nature.

Writing his famous poem “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” in 1751, Thomas Grey popularized the early Romantic’s love for twilight, solitude, “the darkening vale” of melancholy, and Gothic castles, architecture, and the antiquarian spirit. Others, like Clara Reeve and Anne Radcliffe, protested against “the emotional coldness of the classical age.”[19] Near the end of the century, Thomas Percy’s “Reliques of Ancient English Poetry” made known the ancient ballads and songs of Scotland, Wales, and North England, including those of King Arthur and of Robin Hood, providing the indispensable groundwork for Sir Walter Scott and his incredibly popular Waverley novels. Thomas Chatterton, that “exalted genius” who died at age seventeen, captivated the attention of a generation of poets, including Coleridge and Wordsworth. Jane Austen (1775–1817) authored Sense and Sensibility in 1811 and Pride and Prejudice two years later and through her exquisite development of character, explored the affections of the heart in a compressed domestic setting in ways that none of her peers could match.[20]

It was Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832) who best captured the Gothic sentiment of the treasures of Scottish legend on a grand scale. The author of The Heart of Midlothian (1818), Ivanhoe (1819), The Legend of Montrose (1819), and scores of other novels, Scott fathered the historical novel as its own genre and popularized the Gothic novel as no one had before—or has since.

Coleridge and Wordsworth

Coleridge’s early poetry was didactic, simple, and lifeless. All that changed, however, when he read Wordsworth for the first time. In Wordsworth he immediately sensed a philosophical and poetic bond. Wordsworth’s powerful, though simple verse was a mirror to the soul and stirred in Coleridge a spiritual awakening and a yearning to compose his finest poetry. He was therefore delighted when Wordsworth and his sister, Dorothy, a woman of education and refined feelings, deliberately came to Bristol in 1797 to see him.

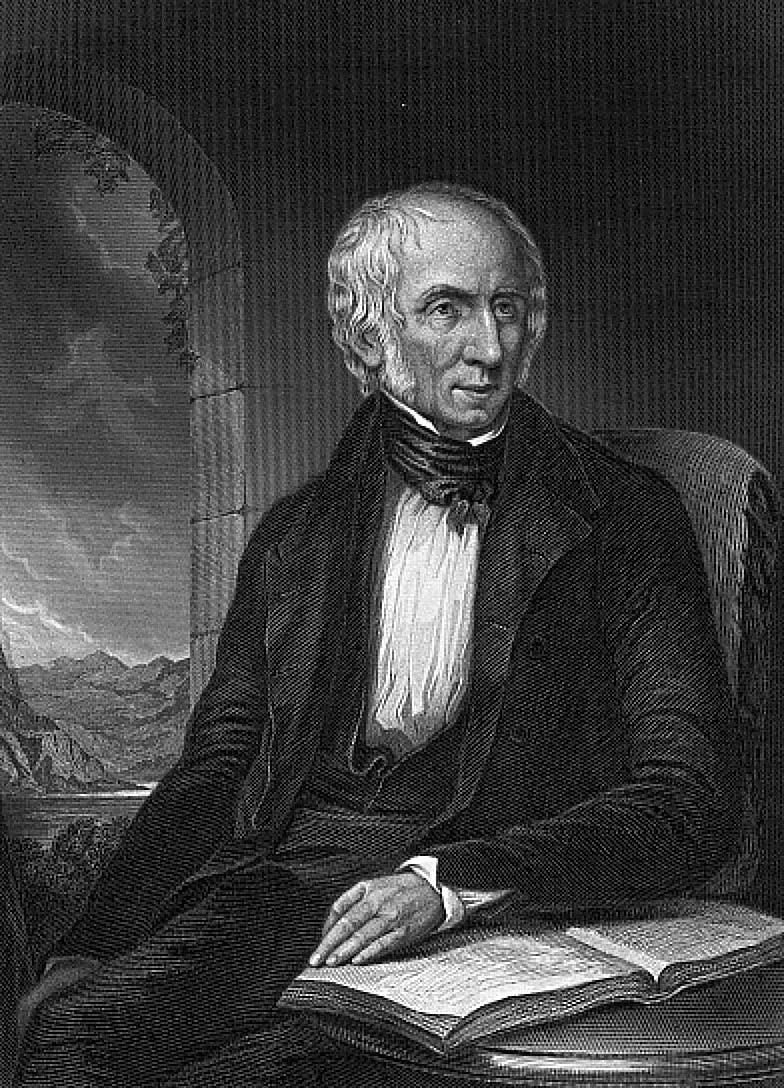

William Wordsworth, 1873 reproduction of an 1839 watercolor by Margaret Gillies.

William Wordsworth, 1873 reproduction of an 1839 watercolor by Margaret Gillies.

The son of an attorney and two years older than Coleridge, Wordsworth had taken notice of several of Coleridge’s so-called conservative poems, including “The Nightingale,” “The Eolian Harp,” and “Religious Musings,” works that interwove natural objects with deep personal religious feeling. Like Coleridge, Wordsworth had quit Cambridge and had separated himself from the Anglican Church. Likewise, he sympathized with the aims and ideals of the French Revolution. He had even visited France in 1790, where he fell in love with a French army surgeon’s daughter, Annette Vallon of Orleans, and fathered a daughter, Caroline, born in 1792. They considered marriage, but the outbreak of war between France and England and the atrocities of the Reign of Terror prevented his return to France.

In addition to these similarities, Coleridge and Wordsworth discovered in one another an ideal harmony of philosophical and poetic viewpoint. The two men shared an appreciation for the beauty of nature, a reverence for the immortal and marvelous mystery or soul of life, and the talent to capture such sentiments in sublime poetry. Thus began one of the most creative, synergistic friendships in all of literary history. Their mutual admiration for each other and for one another’s poetry was virtually boundless and would last a lifetime. While Wordsworth esteemed Coleridge as “the best poet of the age,” Coleridge saw in his new friend “the only man to whom at all times and in all modes of excellence I feel myself inferior.”[21] “I feel myself a little man by his side,” he once confided.[22]

Dorothy Wordsworth was also highly impressed: “Coleridge is a wonderful man; his face beams with mind, soul and spirit. He is so benevolent, so good-tempered and cheerful. . . . At first I thought him plain, that is for about three minutes. He is pale, thin, has a wide mouth, thick lips and not very good teeth, longish loose-growing, half-curling, rough black hair. . . . His eye is large and full, . . . fine dark eyebrows and over-hanging forehead.”[23]

Unlike Coleridge, who was very much cut off from his own family, Wordsworth enjoyed the love, companionship, and keen support of his devoted and intelligent younger sister, Dorothy, who encouraged and supported his literary interests. Wordsworth’s marriage in 1802 to Mary Hutchinson proved to be long and happy, in sharp contrast to that of Coleridge, who seemed seldom at peace with himself or others—a ship without a harbor.

Wordsworth spurned the rigid, intellectual approach to poetry in favor of simple, free-flowing verse. Wordsworth loved to take long walking tours, often for hundreds of miles, over hill and valley, mountain and seacoast, all the time ruminating on the beauties and lasting truths of nature, on the immortality of the soul, and the innocence of childhood. From these he penned such lines as:

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father to the Man![24]

And in his unforgettably beautiful “Ode to Intimations of Immortality,” published in 1807, he penned these lines:

But for those first affections,

Those shadowy recollections,

Which be they what they may,

Are yet the fountain-light of all our day,

Are yet a master-light of all our seeing;

Uphold us, cherish, and have power to make

Our noisy years seem moments in the being

Of the eternal silence: truths that wake

To perish never;

Which neither listlessness, nor mad endeavor,

Nor man nor boy,

Nor all that is at enmity with joy,

Can utterly abolish or destroy!

Hence is a season of calm weather

Though inland far we be,

Our souls have sight of that immortal sea

Which brought us hither,

Can in a moment travel thither,

And see the children sport upon the shore,

And hear the mighty waters rolling evermore.[25]

Like Coleridge and most other Romantics, Wordsworth decried the advances of the Industrial Revolution with its disregard for the environment and the spreading disease of unchecked commercialism:

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers:

Little we see in nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon![26]

Ever more financially comfortable than Coleridge, Wordsworth published ten thousand other lines of rich poetry, including The Excursion (1814), The White Doe of Rylstone and Miscellaneous Poems (1815), Peter Bell and The Waggoner (1819), Yarrow Revisited, and Other Poems (1835), and Poems Chiefly of Early and Late Years (1842).

Later in his life, again like Coleridge, his liberal political views died with the ruthless ambitions of Napoléon. Wordsworth became increasingly conservative with age. He never returned, as Coleridge did, to the orthodoxy of Anglican Christianity, preferring to see God everywhere, manifested in the harmony of nature. Much more acclaimed in life than Coleridge ever was, Wordsworth succeeded Southey as poet laureate of England, receiving honorary degrees from Oxford and Durham Universities before his death in 1850. His simplicity of verse, his careful descriptions, his ability to touch the deepest human emotions, aspirations, and inner religious convictions and blend them into memorable and beautiful verse made Wordsworth arguably the greatest poet of his age.

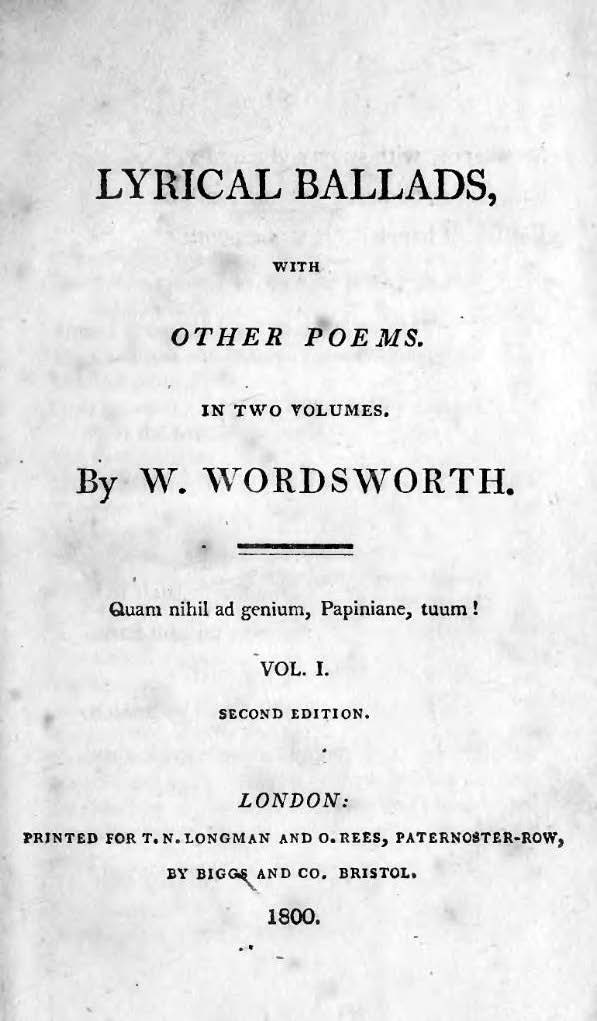

Title page of Lyrical Ballads (1800).

Title page of Lyrical Ballads (1800).

Wordsworth and Coleridge blended philosophically and poetically so very well together that they decided to publish a combined collection of their early poetry in a simple, thin volume entitled Lyrical Ballads, which their bookseller friend Joseph Cottle published in Bristol in 1798. Coleridge contributed his “Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” “Christabel,” “The Nightingale,” and other poems, to which Wordsworth added “The Dungeon,” “The Idiot Boy,” and “Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey,” plus several others.[27] Coleridge later looked back at this time as the high tide of happiness in his life.

Though dual in authorship, the purpose of Lyrical Ballads was one: to write a wholly new kind of poetry in search of the enduring truth of who man is and of what constitutes the soul. Coleridge wrote about supernatural persons and characters, such as the ancient mariner, whose fantastic voyage of death and redemption nevertheless taught profound truths, so long as the reader gave it “poetic faith”—“that willing suspension of disbelief” so essential to understand all his poetry.

For his part, Wordsworth meant “to give the charm of novelty to things of every day” by awakening attention to “the loveliness and wonders” of the everyday world and encouraging others to see and learn from nature “truths which perish never.”[28] His poetic vision was to give nature a meaning it had never taken before.

These few lines from “Tintern Abbey” may capture his intent: “For I have learned to look on nature,” he penned:

. . .Therefore am I still

A lover of the meadows and the woods,

And mountains; and of all that we behold

From this green earth; . . . well pleased to recognize

In nature and the language of the sense,

The anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse,

The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul

Of all my moral being.[29]

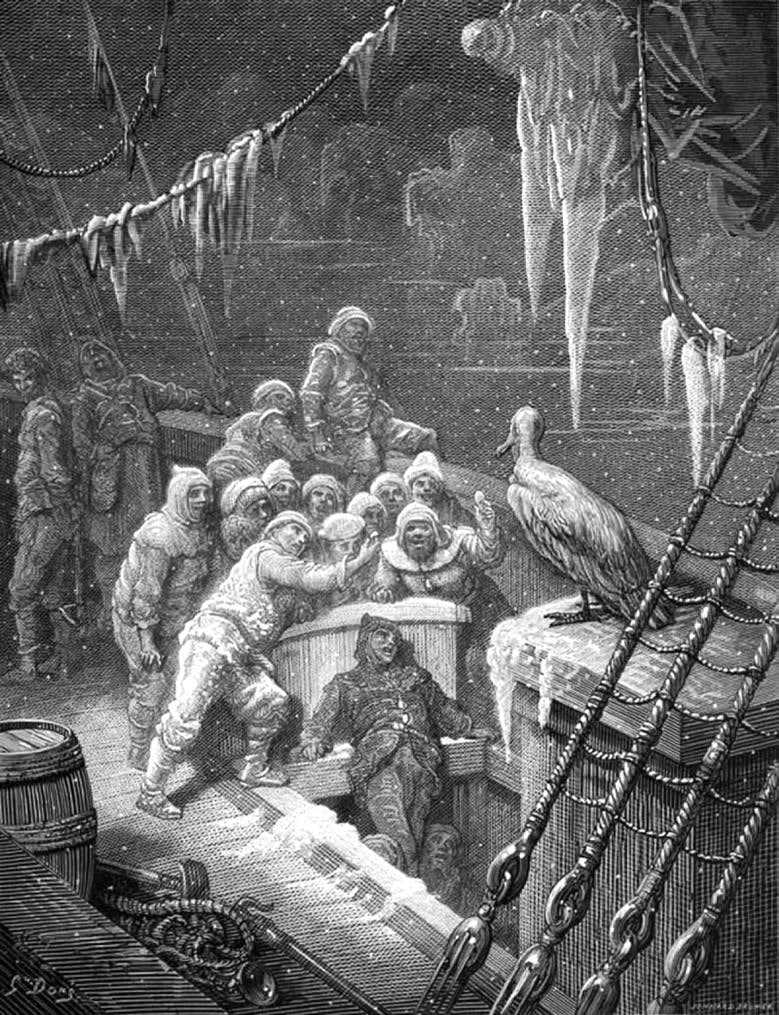

The Albatross, engraving by Gustave Doré (1876).

The Albatross, engraving by Gustave Doré (1876).

Few poems are so easy to read and yet so difficult to comprehend as “Rime of the Ancient Mariner.”[30] Though Coleridge and Wordsworth set out together to write it, Wordsworth soon deferred to the supernatural and fantastic imagination of Coleridge, whose ancient mariner taps a passerby on his way to a wedding feast. This Mariner’s story or dream ballad was so spellbindingly interesting that his listener soon forgot all about, the wedding feast; he and others fell into its trance.

The wedding guest sat on a stone;

He cannot choose but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man

The bright-eyed Mariner.

The ship was cheered, the harbor cleared,

Merrily did we drop

Below the kirk, below the hill,

Below the lighthouse top.

The sun came up upon the left,

Out of the sea came he!

And he shone bright, and on the right

Went down into the sea.[31]

Far down into the southern sea, they sailed into the “copper sky” of the tropics until an albatross flew across the sky and followed them for days. The mariner’s killing of the bird, soon perceived by his fellow sailors as “a hellish thing to do,” cast a shadow over the voyage and brought misery, misfortune, and death upon the crew.

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

Water, water, everywhere,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, everywhere,

Nor any drop to drink.[32]

Becalmed one moment and frozen in ice “as green as emerald” the next, the ship sailed on from one misfortune to another, all in punishment for the mariner’s sinful act. Eventually after a ghost ship passed by, all two hundred of his fellow sailors died at sea, but upon his remorse and repentance, they mysteriously returned to life, “a ghastly crew” to sail with him back northward.

They groaned, they stirred, they all uprose,

Nor spake, nor moved their eyes;

It had been strange, even in a dream,

To have seen those dead men rise.[33]

Chastened and unforgetting, the mariner concluded his tale with these famous lines:

Farewell, farewell! But this I tell

To thee, thou Wedding Guest!

He prayeth well, who loveth well

Both men and bird and beast.

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.[34]

Coleridge’s haunting dream-poem can be understood on many different levels. Through his imaginary, supernatural archetype, he speaks to humankind’s earthly odyssey: the inevitable fall from grace through the sinful act of killing the albatross and the ultimate redemption and resurrection, “almost restoration.” “Almost” is the appropriate term, because Coleridge never tells a fully happy ending. Neither the mariner nor his listener went to the wedding feast. There is always a sense of disappointed resolution in his writings, at best a damaged redemption. “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” is, at base, a deeply Christian poem. Whereas Wordsworth found new meaning and salvation in nature, Coleridge found them in Christianity—not in the narrow confines of evangelical revivalism or Anglican ritualism and denominationalism, but in a deeply personal Christian conversion. This, however, is getting ahead of our story.

“Sinking, Sinking, Sinking”: Coleridge’s Slide into Darkness, 1799–1816

While Lyrical Ballads was being published, Coleridge, Wordsworth, and Dorothy Wordsworth traveled to Germany on yet another of their trips together, walking, as was their custom, hundreds of miles through the countryside.[35] While Wordsworth and Dorothy were writing an explanatory “Prelude” to a second edition of Lyrical Ballads, Coleridge spent three months as a guest in a home at Ratzeburg, where he learned to converse and write in German. Then from February to June, fulfilling the design of his trip, he studied the writings of Friedrich Schiller and other German philosophers and writers at Gottingen University. Coleridge would soon translate Schiller’s Wallenstein into English.

On their return to England in May 1799, Coleridge went on yet another long walking tour with the Wordsworths through their childhood countryside in the Lake District near Afton, England. Coleridge became so enamored with the astonishing beauty of the place that he convinced his wife to move with him into a new cottage at Greta Hall near Keswick, only thirteen miles away from where the Wordsworths took up their residence at Dove Cottage. Coleridge felt more the genius of creation when around Wordsworth and the Lake District than anywhere else. It was here the Coleridge’s third son, Derwent, was born in late 1800.[36]

There was, however, another attraction, this time in the form of yet another Sara—Sara Hutchinson, the younger sister of Mary Wordsworth. Coleridge found in her the love he never felt for his wife: a companionship of mind and spirit he longed to have. His unfulfilled marriage, acute poverty, proneness to drink, and his acute sciatica, likely brought on by his exceedingly long walks and climbs, led Coleridge to experiment with “Kendal Black Drop,” another name for laudanum. Coleridge first began taking it with good results, but he soon began consuming it in ever greater quantities. Laudanum, a preparation of opium, eventually wrought its devastatingly addictive powers on Coleridge until he was secretly taking a pint of opium every day—the “accursed drug,” as he put it.

The change in him was noticeable as he missed, without explanation, many appointments and lectures. His hands began shaking so that he could not lift a glass of wine without spilling it all over the floor, although one hand supported the other. His efforts at quitting caused “intolerable restlessness, incipient bewilderment.” “You bid a man paralytic in both arms,” he wrote to a close friend who was wondering at his inability to quit, “to rub them briskly together, and that will cure him. ‘Alas!’ he would reply, ‘that I cannot move my arms, is my complaint and my musing.’”[37] “Sinking, sinking, sinking!” he wrote Humphrey Davy in April 1801, “I feel that I am sinking.”[38]

Putting into poetry the growing agony of his soul, Coleridge, otherwise an optimist, wrote “Dejection: An Ode” in 1802, wherein he lamented the downward course his life was taking:

A grief without a pang, void, dark, and drear,

A stifled, drowsy, unimpassioned grief,

Which finds no natural outlet, no relief,

In word or sigh, or tear. . . .

There was a time, when though my path was rough,

This joy within me dallied with distress,

And all misfortunes were but as the stuff

Whence fancy made me dreams of happiness:

For hope grew round me, like the twining vine,

And fruits, and foliage, not my own, seemed mine.

But now afflictions bow me down to earth:

Nor care I that they rob me of my mirth;

But oh! such visitation

Suspends what nature gave me at my birth,

My shaping spirit of imagination.[39]

In search of a better climate and in hopes of recovery, Coleridge set out for Malta in 1804 with a new friend, John Stoddart. In so doing, Coleridge left his wife and children once again in the “trusty vice fathership” of his brother-in-law, Robert Southey, who was now more than ever critical of his brother-in-law’s repeated moral misjudgments in leaving his family “to chance and charity.”[40] So too was Wordsworth critical of Coleridge spending much more time with the unmarried Sara Hutchinson than with his own wife.

While at Malta, Coleridge accepted one of the only regular paying positions of his life, as public secretary to the British governor of the island. However, after only a few months, he moved on to Sicily, Etna, and finally to Rome. At this same time Napoléon, having just won the Battle of Austerlitz, was on the march through Italy. With England now at war with France, no Englishman was safe, especially one who had recently condemned Napoléon in the Morning Post as “a remorseless invader, tyrant, usurper.”[41] Coleridge fortunately found passage on an American ship for England.

Not anxious to return home, though his wife dearly wanted him back, and in agony of self-reproach, a virtually penniless Coleridge went instead to London, where he moved into a tiny one-room apartment in the upstairs offices of the Courier, a newspaper owned by Daniel Stuart, his former employer at the Morning Post. Thanks to the financial windfall of some three hundred pounds from a young admirer, the future famous essayist Thomas de Quincey (yet another in a long list of benefactors), Coleridge eventually returned to his wife and family in August 1806 after a three-year absence from home, having written no more than a handful of letters to his wife in all that time. Still hoping to preserve at least a semblance of a marriage, his long-suffering Sara tried to welcome him back. By now, their third child and only daughter, Sara, had been born. And while their feelings one for another were obviously strained, the Coleridges did love and enjoy their children. Young Sara, who far exceeded her brothers in intellect and literary skills, would edit and publish a great many of her father’s unpublished works.

Meanwhile, Coleridge was undergoing a profound change in outlook. As his poetic powers and interests faded and Wordsworth’s increased, he became more and more the literary critic, philosopher, and, eventually, theologian. He accepted an ever-increasing number of invitations to return to London to lecture on literature, specifically on Shakespeare, Milton, Homer, Dryden, and several other great writers. Showing a mastery of Shakespeare’s dramas, especially Hamlet, and the character and structure of his many plays and sonnets, Coleridge spoke of essential meanings of Shakespeare not often heard. Speaking extemporaneously and often without written notes, his green eyes darting wildly, he soon found himself in increasing demand. Here at last he had found, as one of his most recent biographies has noted, “a forum ideally suited to his extemporizing genius.”[42] Wrote one of his listeners, “It was unlike anything that could be heard elsewhere; the kind was different, the degree was different, the manner was different. The boundless range of scientific knowledge, the brilliancy and exquisite nicety of illustration, the deep and ready reasoning, the strangeness and immensity of bookish lore.”[43]

Coleridge was a gifted orator and lecturer, “like a being dropped from the clouds,”[44] as Cottle once described him. Said the critic William Hazlitt, “He talked on forever, and you wished him to talk on forever.”[45] He took scarce attention to dress or appearances but enthralled his listeners at this time as much as he had done in his early years in the army and at Cambridge. He was always planning more than he could ever accomplish, but his listeners loved him regardless and considered it almost a “profanation to interrupt so impressive and mellifluous a speaker.”[46] However, Madame Germaine de Staël, a well-known contemporary critic of the arts, said that Coleridge was “great in monologue, but he has no idea of dialogue.”[47]

Coleridge enthralled his listeners with his exciting and enthusiastic probes into the life and thought of Aristotle, Milton, Shakespeare, Christ and his Apostles, Wordsworth, Kant, Schelling, and other German philosophers. He quite literally talked his way into developing his own philosophy of life, so much so that he earned the title “The Great Conversationalist,” or as one described him, “an intellectual exhibition altogether matchless.”[48] In the process, Coleridge created an ever-expanding circle of friends who kept coming back for more. What he lacked with home and family he made up for with friends.

In 1810 he decided on yet another ill-fated publishing project, this time The Friend: A Literary, Moral, and Political Weekly Paper, a rather highbrow enterprise aimed at London’s intelligentsia. Unlike The Watchman, The Friend set out to be an entirely literary journal of poetry, prose, and criticism. With the indispensable help of Sara Hutchinson as collaborator, Coleridge managed to publish twenty-seven issues. It became a vehicle for much of his thought, literary criticism, and poetry, but it could not, however, survive the competition, his continuing proneness to drink, his addiction to opium, and of course, his habitual fiscal irresponsibility.

Coleridge’s personal habits and addiction and his continued emotional attachment to Sara Hutchinson led not only to an inevitable separation from his wife but also to an unfortunate estrangement from the Wordsworths, a loss Coleridge took particularly hard. Long tolerant of his best friend’s weaknesses, Wordsworth deplored what Coleridge was doing to himself and the shame he was bringing upon others.

Oh! piteous sight it was to see this man

When he came back to us a withered flower,

Or, like a sinful creature, pale and wan.

Down would he sit; and without strength or power

Look at the common grass from hour to hour.[49]

The two men said things about one another that they later regretted. And though they later tried to patch up their differences, their friendship never quite recovered, and it left a wound on both men’s souls.

Coleridge returned to London, this time for good, in 1810. After being asked to leave his apartment at his old Bristol friends’ house, the Morgans, he once again begged scant room and board from his associates at the Courier in exchange for freelance writing and editing. By this time the Wedgwood brothers had revoked their pledged annuity, convinced that Coleridge was squandering the funds for no good purposes. Despite the fact that his one attempt at drama, the tragedy Osoric, was accepted and ran for twenty performances, Coleridge was so poor he couldn’t even buy issues of the paper he worked for!

De Quincey described Coleridge’s descent as follows: “I called upon him daily, and pitied his forlorn condition. There was no bell in the room which for many months answered the double purpose of bed-room and sitting-room. Consequently I often saw him picturesquely enveloped in night caps surmounted by handkerchiefs indorsed upon handkerchiefs, shouting . . . down three or four flights of stairs, to a certain ‘Mrs. Brainbridge,’ his sole attendant, whose dwelling was in the subterranean regions of the house.”[50]

In these, his darkest hours, this “Archangel a little damaged”—as his lifelong friend Charles Lamb called him—wrote on. Sometime between 1808 and 1810, due largely to his “boundless power of self-retrieval,” he managed to write one of his greatest pieces of prose and literary criticism: Biographia Literaria.

Still, his hapless addiction only worsened until even his beloved Sara Hutchinson left him to his nighttime agonies and howls. In his poem “The Pains of Sleep,” he offered this glimpse at his sufferings and nightmares, or what he called “the unfathomable hell within,” for Coleridge looked at his drinking and opium addiction not merely as human weaknesses but abominable sins in the sight of God. “You bid me pray,” he responded to one of his well-meaning friends. “O, I do pray inwardly to be able to pray.”[51]

But yester-night I prayed aloud

In anguish and in agony,

Up-starting from the fiendish crowd

Of shapes and thoughts that tortured me

A lurid light, a trampling throng,

Sense of intolerable wrong,

And whom I scored, those only strong!

He ended the poem with this expression of love:

To be beloved is all I need

And whom I love, I love indeed.[52]

In a letter to an old Bristol friend, Coleridge penned the following painful picture of himself: “Conceive a poor miserable wretch, who for many years has been attempting to beat off pain by a constant recurrence to the vice that produces it. Conceive a spirit in hell, employed in tracing out for others the road to that heaven, from which his crimes exclude him! In short, conceive whatever is most wretched, helpless and hopeless, and you will form a tolerable notion of my state.”[53] On hearing one of Coleridge’s rambling lectures, Lord Byron took pity on him and gave him a hundred pounds to live on and publish a small volume of his more recent poetry.

One of Coleridge’s biographers summed up his situation most powerfully: “It was a terrible conflict. No struggle more awful played a part in the life of any man. That fearful conflict day by day, night by night, between remorse and appetite, the heartrending appeals for mercy, and forgiveness for genius wasted, the anguish of powerlessness, the sense of extinguished vigour, the thought of what might have been, and is not, and never can be.”[54]

Coleridge was truly a pitiable specimen of human nature, seeking and praying for help and asylum from whatever quarter he could find it. He had, as one might say today, hit rock bottom and had nowhere else to turn. Suicide—or, as he put it, “annihilation”—may well have been the one alternative left. At this moment of deepest distress, salvation came in the form of a friend, Joseph Adams, who put him in touch with Dr. James Gillman, a surgeon, apothecary, and naturalist, who would prove a good Samaritan to Coleridge for the rest of his life. Adams’ importuning letter to Gillman is worth citing:

Halton Garden, 9 April 1816

Dear Sir:

A very learned, but in one respect an unfortunate gentleman has applied to me on a singular occasion. He has for several years been in the habit of taking large quantities of opium. For some time past, he has been in vain endeavoring to break himself off it. It is apprehended his friends are not firm enough, from a dread, lest he should suffer by suddenly leaving it off, though he is conscious of the contrary; and has proposed to me to submit himself to any regimen, however severe. With this view, he wishes to fix himself in the house of some medical gentleman, who will have courage to refuse him any laudanum, and under whose assertions, should he be the worse for it, he may be relieved. As he is desirous of retirement, and a garden, I could think of no one so readily as yourself. Be so good as to inform me, whether such a proposal is absolutely inconsistent with your family arrangements. I should not have proposed it, but on account of the great importance of his character, as a literary man. His communicative temper will make his society very interesting, as well as useful. Have the goodness to favour me with an immediate answer; and believe me, dear sir, your faithful humble servant.[55]

Five days later, the forty-three-year-old Coleridge moved in with the good doctor and his kindly wife at their Highgate residence and began a slow, painful, and cautious recovery. A stay that was meant to have lasted one month stretched out for eighteen years until Coleridge’s death in 1834. At last he had found a home, and he began to rediscover himself.

“It Is Better Than I Deserve”: His Final Years

The concluding years of Coleridge’s life at Highgate from 1816 to 1834 provide the ideal opportunity to contemplate three legacies of his life and thought; first, a physical and mental recovery more wonderful than his fall; second, his rising reputation among scholars as perhaps the towering literary figure, critic, and philosopher of his time; and finally, his odyssey into Christianity, a religious sojourn tempered by the agony of his own personal tragedies. For, of all the major English romantics, many of whom believed Christianity to be a cultural and philosophical irrelevancy, Coleridge found in Christ, the Bible, and the Holy Spirit the redemption of his sufferings, the revelation to his inquiries, and the purpose to his ponderings. These three factors, in addition to the recent recovery of so much of his thought and writings, go far to explain why Coleridge has been rediscovered by many modern scholars and why much has recently been written about his life, thought, and faith.

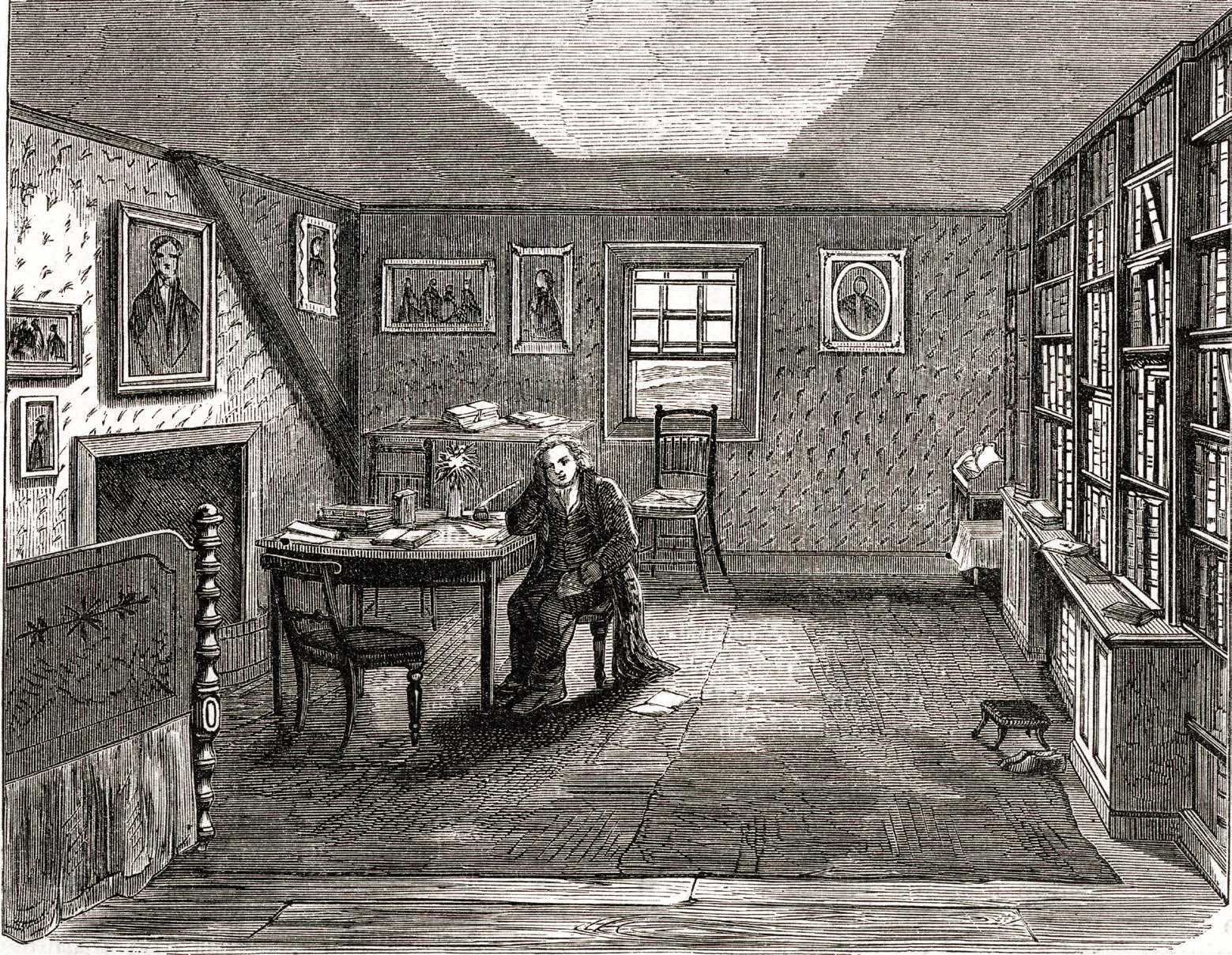

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, English Poet and Critic in His Room at Gillman's House, The Grove, Highgate, London. Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, English Poet and Critic in His Room at Gillman's House, The Grove, Highgate, London. Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo.

As to his recovery, none of his recent biographers claim that he quit opium entirely, but all agree that he reduced the use of it so dramatically that the drug no longer dominated his life. That he was in near constant pain is also clear; however, he fought his way on not merely to a physical recovery but also to a profoundly spiritual recovery. And it was the Gillmans to whom he gave full and constant credit. “The fortunate state of convalescence I am now in,” he wrote three months into his recovery in a tone of cherished optimism, “I owe to the unrelaxed attention, the professional skill, and above all the continued firmness and affectionateness of Dr. Gillman, his wife, and their two sons.”[56]

Thomas Carlyle came to know and greatly admire Coleridge at Highgate and tells this touching remembrance of one of his many visits: “‘Ah, your tea is too cold, Mr. Coleridge!’ moaned the good Mrs. Gillman once, in her kind, reverential and yet protective manner, handing him a very tolerable though belated cup. ‘It’s better than I deserve!’ said Coleridge, in a low hoarse murmur. ‘It’s better than I deserve.’”[57]

The Gillman’s benefited from Coleridge’s presence as well. The good doctor and his wife adopted him into their daily family routine, even taking him with them on annual vacations to the coast, thoroughly enjoying his kindness and lively conversations. “His manner, his appearance, and above all, his conversation, were captivating,” Gillman once remarked. “I felt indeed almost spell-bound.”[58]

A recovering Coleridge set out to mend his broken family life. He tried hard to see his oldest and favorite son, Hartley, now at Cambridge, and to help him recover from his own propensities to alcohol, an inclination that unfortunately led to his ruin. Coleridge took much of the blame on himself and wished for a happier day. The blighted life Hartley chose for himself became very painful to a profoundly disappointed, self-recriminating father, a “peal of thunder,” as he called it in his declining years. After 1822 father and son never met again, despite Coleridge’s several written overtures.

With the encouragement of Coleridge, Derwent, one of his younger sons, went on to become an Anglican minister. Meanwhile Coleridge’s wife and daughter moved to nearby quarters to spend more time with him. Coleridge and his estranged wife soon recovered a semblance of friendship not felt in almost forty years, and as grandparents they came to enjoy one another’s company and that of their extended family. Sara, their daughter, of a strong literary bent herself, loved and admired her father and spent much of her adult life compiling, cataloging, and publishing his writings, as did his nephew (William Hart Coleridge) and grandson, Carl Woodring.

Meanwhile friends, younger writers, and admirers of all kinds gravitated to the “sage of Highgate” in ever-growing numbers. These included such luminaries as Thomas Carlyle, Sir Walter Scott, the American novelists James Fenimore Cooper and Ralph Waldo Emerson, the Scottish divine Ernest Irving, the German poet Ludwig Tieck, the businessman Thomas Allsop, the founder of the Swendenborgian Society—Charles Tulk, his constant friend Charles Lamb, and hosts of others. Lamb could not withhold the excitement he felt at seeing his old friend rejuvenated. “The world has given you many a shrewd nip and gird,” he said, “but either my eyes are grown dimmer, or my old friend is the same who stood before me 23 years ago, his hair a little confessing the hand of time, but still shrouding the same capacious brain, his heart not altered, scarcely where it ‘alteration finds.’”[59] Coleridge’s so-called “Highgate Thursdays” became a lively forum of literary, philosophical, and religious musings. Much of what he said others eagerly jotted down, and his writings were later published by his grandson in two volumes of Table Talk.[60]

John Keats—another giant of the Romantic age and an exquisite observer of nature, as seen in his “Ode to a Nightingale” and “Ode on a Grecian Urn”—visited Coleridge just before his own untimely death in 1819. Keats was drawn captive into the writings of Coleridge, especially his Biographia Literaria. Within days of their meeting, Keats wrote his “La Belle Dame Sans Merci,” and “Ode to a Nightingale.” Roundly criticized by William Hazlitt, a critic and an old protégé, for its unsystematic ramblings, Biographia Literaria struck a resonant chord with Keats, especially Coleridge’s account of Shakespeare’s “protean” imaginative powers and the idea of poetry demanding “a willing suspension of disbelief.” Meanwhile, Byron, for all his sarcasm and witty criticism, loved Coleridge’s “Christabel” and referred to him as “a genuinely prophetic writer.”[61] Coleridge’s “growing sense of security”—as one of his finest biographers, Richard Holmes, has phrased it—resulted in his bringing more of his finest work into print than ever before. These included Biographia Literaria (1817) and Sibylline Leaves (1817). Highgate was a harvest, a second birth, and Coleridge became a national figure.[62]

One of his greatest joys was a partial reconnection with Wordsworth. In the summer of 1828 the two men, along with Dorothy Wordsworth, who was then experiencing the early onset of dementia, spent a wonderful six weeks together touring the Rhineland, striving to rekindle the joys of a youthful friendship.

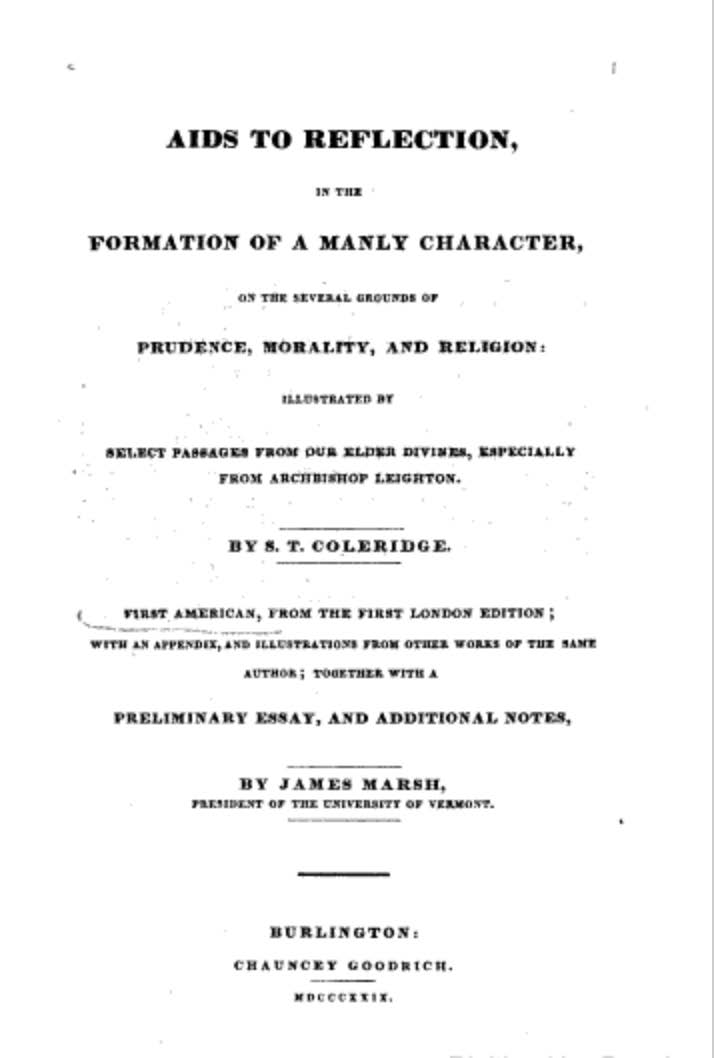

Title page of Aids to Reflection: In the Formation of a Manly Character on the Several Grounds of Prudence, Morality, and Religion (1825), by Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Title page of Aids to Reflection: In the Formation of a Manly Character on the Several Grounds of Prudence, Morality, and Religion (1825), by Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Coleridge continued to write poetry and at last received recognition of his rising reputation from the Crown in the form of a public pension. In 1819 he delivered his final series of lectures, focusing on Shakespeare (of whom he had devoted some sixty lectures in his lifetime) and the reconciliation of philosophy and religion. Coleridge distinguished the Bard from all other writers and poets by seeing in his plays expectation placed above surprise, an unfailing and remarkable development of strong and memorable characters, and a keeping to what Coleridge called “the high road of life”—that there are no innocent adulteries, no virtuous vices. Shakespeare never “rendered amiable” that which religion and reason teach one to detest. Shakespeare succeeds because he expresses human emotions so brilliantly, vengeance and revenge, passion and love.[63]

Literary scholar René Wellek has argued Coleridge’s place in the sun as follows: “Coleridge is the intellectual centre of the English Romantic Movement. Without him, we would feel that English Romanticism, glorious as its poetry and prose is in its artistic achievements, remained dumb in matters of the intellect. We can extract a point of view, a certain attitude from the writings of Shelley and Keats, we find an expression of a creed in Wordsworth, but only in Coleridge we have thought which can be expressed in logical form and can claim comparison with the systems of the great German philosophers of the time.”[64]

Coleridge sought to overcome the dualism that had separated the philosophies of past centuries essentially into the two camps of spirit and body, mind and matter, and reason and understanding that had prompted pantheism, deism, and atheism.[65] In his philosophical lectures, which filled 123 pages of a brown leather-bound notebook, he covered all of Western philosophy from Plato and Aristotle, to medieval Christian thought, the Reformation and the Enlightenment, and eventually Kant and Schelling. Praising the new spirit of science, he argued that it was compatible with religion and urged the rejection of the philosophy of materialism. In his brand of metaphysics, reason stood outside of mechanistic, logical thought and was the domain of knowledge learned by the inner soul of man. As much, if not more, would be learned from the inner man and the nature within than from deductive reasoning, science, and logic.

In these later years, Coleridge also recognized the pressing need in postwar England for social change and urgent political action to minimize the “tremendous economic gaps between classes,” which he termed in his Lay Sermons the “anti-magnet of social disorganization.” In a series of political pamphlets, he criticized not only Parliament for doing too little to address economic problems, child exploitation, insufferably long work hours, and the negative impact upon the family therefrom, but he also condemned the clergy for, “sleeping with their eyes half-open.”[66]

Thomas Carlyle may have best captured Coleridge’s rising public reputation and magnetic literary force:

Coleridge sat on the brow of Highgate Hill, in those years, looking down on London and its smoke-tumult, like a sage escaped from the inanity of life’s battle, attracting towards him the thoughts of innumerable brave souls still engaged there. His express contributions to poetry, philosophy, or any specific province of human literature or enlightenment, had been small and sadly intermittent; but he had, especially among young enquiring men, a higher than literary, a kind of prophetic or magician character. He was thought to hold, he alone in England, the key to German and other Transcendentalisms . . . to the rising spirits of the young generation he had this dusky sublime character; and sat there as a kind of Magus, girt in mystery and enigma.[67]

Highgate may best be remembered as the setting for the 1825 for the publication of Coleridge’s Aids to Reflection, which stands as a testament to his philosophy that the greatest truths of the soul are not obtained through logic and deductive reasoning or even through communing with nature. Rather, the deepest truths, those which he believed were found in orthodox Christianity, come through “Reason” which he defined as an imputation of the logos, or spirit, and specifically, the spirit of Christ within. Above all, Aids to Reflection amounted to a series of carefully reasoned arguments or, better, “reflections” on why he had come to Christianity and what in Christianity stands above all other philosophies: (a) a belief in a risen Christ who redeems mankind, (b) a belief in the necessity of repentance and faith, (c) a belief in the immortality of the soul, (d) a belief in the awakening of the spirit and its communion with the Holy Spirit, (e) a belief that by the gifts of that Spirit one will manifest works of love and obedience, (f) a belief that such works “are the appointed signs and evidences of our faith,” and (g) a belief in a “kind and gracious Father in Heaven, who may grant forgiveness of our deficiencies by the perfect righteousness of the Man, Christ Jesus, even the Word that was in the beginning with God.”[68]

It would be both simplistic and erroneous to argue that Coleridge was here, in the twilight of his life, returning to his childhood Anglican beliefs. However, what he believed as a child laid the foundation of the later discovery of his life. “Christianity is not a theory, or a speculation,” he wrote, having learned much from his own self-imposed sufferings, “but a life; not a philosophy of life, but a life and a living process.”[69]

Besides asserting his own deep Christian convictions, Coleridge tangled with many of the greatest theological and philosophical questions facing Christianity since the Reformation. What had happened to Christianity through the ages? What is the origin of the devil? What is the nature of man and the Trinity? What is reason and its relationship to understanding and faith?

After the deliberate renunciation of early Christianity, and “across the night of Paganism, philosophy flitted on, like the lantern-fly of the Tropics, a light to itself, and an ornament, but alas! No more than an ornament of the surrounding darkness.”[70] “This was the true and first apostasy,” he continued, in words that would have resonated with Joseph Smith, “when in Council and synod the Divine Humanities of the Gospel gave way to speculative systems, and religion became a science of shadows under the name of theology, or at best a bare skeleton of truth, without life or interest, alike inaccessible and unintelligible to the majority of Christians. For these therefore there remained only rites and ceremonies and spectacles, shows and semblances.”[71]

The result of this apostasy was a decrease in willingness to consider God in his “personal attributes,” and from thence came a distaste of all the peculiar doctrines of the Christian faith, the Trinity, the Incarnation, and redemption. Coleridge says of this, “I speak feelingly; for I speak of that which for a brief period was my own state.”[72] Coleridge condemned pantheism and deism as impersonal religions, prone to the secularism he saw as encroaching upon the world. He even condemned the nature god of his fellow Romantics, Wordsworth included. “The last and total apostasy of the Pagan world, when the faith in the great I AM, the Creator, was extinguished in the sensual polytheism which is inevitably the final result of Pantheism or the worship of Nature, . . . that the material universe [is] the only absolute Being.”[73]

Yet Coleridge was also highly critical of the evangelical Christian movement then coursing through Great Britain, which he denounced as fanatic literalism, a sordid “Bibliolatry” in its attempt to see in every word and phrase therein the infallible word of God. Not that Coleridge denied the supreme place of the Bible. In fact he once wrote, “in the Bible there is more that finds me than I have experienced in all other books put together.” The “words of the Bible find me at greater depths of my being; and that whatever finds me brings with it an irresistible evidence of its having proceeded from the Holy spirit.”[74] However, he believed the Bible was not the sole source of truth. It “is the appointed conservatory, an indispensable criterion, and a combined source and support of true belief. But that the Bible is the sole source; that it not only contains, but constitutes the Christian religion; that it is, in short, a creed, consisting wholly of Articles of Faith, . . . I, who hold that the Bible contains the religion of Christianity . . . dare not say.”[75]

Thus, Coleridge believed that revelation was an ongoing necessity, that it was both objective, coming from the prophets and the Bible as the law, and subjective, emanating from the Holy Spirit within man. “Without that spirit in each true believer, whereby we know the spirit of truth and the spirit of error in all things pertaining to salvation, the consequence must be ‘so many men, so many minds!’”[76] “Revealed religion is in its highest contemplation the unity, that is, the identity or co-inherence of subjective and objective.”[77] Coleridge’s Christianity was too broadly conceived to be straightjacketed by sectarianism and too narrowly perceived to allow for godless secularism. Little wonder his views later gave rise to what in Anglican Church history is known as the “Broad Church Movement” of the latter nineteenth century.

On the matters of the fall of man and original sin, he felt the weight of that terrible reality in his own life: “which I feel and groan under, and by which all the world is miserable.” Fallen as he believed himself to be, however, he wrote that humankind is not predestined to heaven or hell, as the Calvinists insisted, nor is the will of humankind a captive of fallen nature, as Luther indicated. “The least reflection will convince even man that he is a responsible being” and that his will is the “condition of his personality.” “Evil is not something imposed on man,” he argued.[78] “The corruption of my will may very warrantably be spoken of as ‘consequence’ of Adam’s fall,” he went on to clarify, “even as my birth of Adam’s existence. . . . But that it is on account of Adam, or that evil principle was, a priori, inserted or infused into my will by the will of another, . . . this is nowhere in scripture.”[79] “Sin is an evil which has its ground or origin in the agent, and not in the compulsion of circumstances.”[80] Little wonder that he opposed infant baptism.

One of Coleridge’s lasting contributions to philosophy was his carefully developed differentiation between reason and understanding. In his mind, to mix the two led to hopeless mysticism and atheism. Understanding pertains to sensory perception of the external realities around us, including nature, science, and all other “experimental notices,” and is “the faculty by which we reflect and generalize.” Even animals have understanding, at least to some degree.

Reason, on the other hand, is neither cold logic nor a form of mysticism; rather, it is essentially spiritual and comes from within. He described it as “the power of universal and necessary convictions, the source and substance of truths above sense, having their evidence in themselves.” It is “the light that lighteth every man’s individual understanding,” “an influence from the Glory of the Almighty, . . . the Messiah, as the Logos.”[81] Reason, therefore, is a God-sponsored, Christ-given endowment and “affirms truths which no sense could perceive, nor experiment verify, nor experience confirm.”[82] Likewise, such reason leads the true Christian to a belief in the Holy Spirit.

The remedy to fallen humankind, he argued, lies outside of oneself, much like a sick patient who cannot nurse or cure him or herself. Coleridge had arrived at a point in his life when he was asking “the most momentous question a man can ask: . . . Have I a Savior? . . . Have I any need of a Savior? For him who needs none, . . . there is none, as long as he feels no need.”[83] Redemption, or rescue through Christ, is the great design of religion, a truth many past philosophers and contemporaries did not or would not see. Drawing this lesson from art, Coleridge concluded:

As in great maps or pictures you will see the border decorated with meadows, fountains, flowers, and the like, represented in it, but in the middle you have the main design; so amongst the works of God is it with the foreordained Redemption of Man. All his other works in the world, all the beauty of the creatures, the succession of ages, and all the things that come to pass in them, are but as the border to this as the main piece. But as a foolish unskilled beholder, not discerning the excellency of the principal piece in such maps or pictures, gazes only on the fair border and goes no further, so thus do the greatest part of us as to the great work of God, the redemption of our personal Being, and the reunion of the Human with the Divine, by and through the Divine Humanity of the Incarnate Word.[84]

Cottle recalled that Coleridge spoke of Christ “with an utterance so sublime and reverential, that none could have heard him without experiencing an occasion of love, gratitude, and adoration. . . . a truth incontestable to all who admitted the inspiration and consequent authority of scripture.”[85]

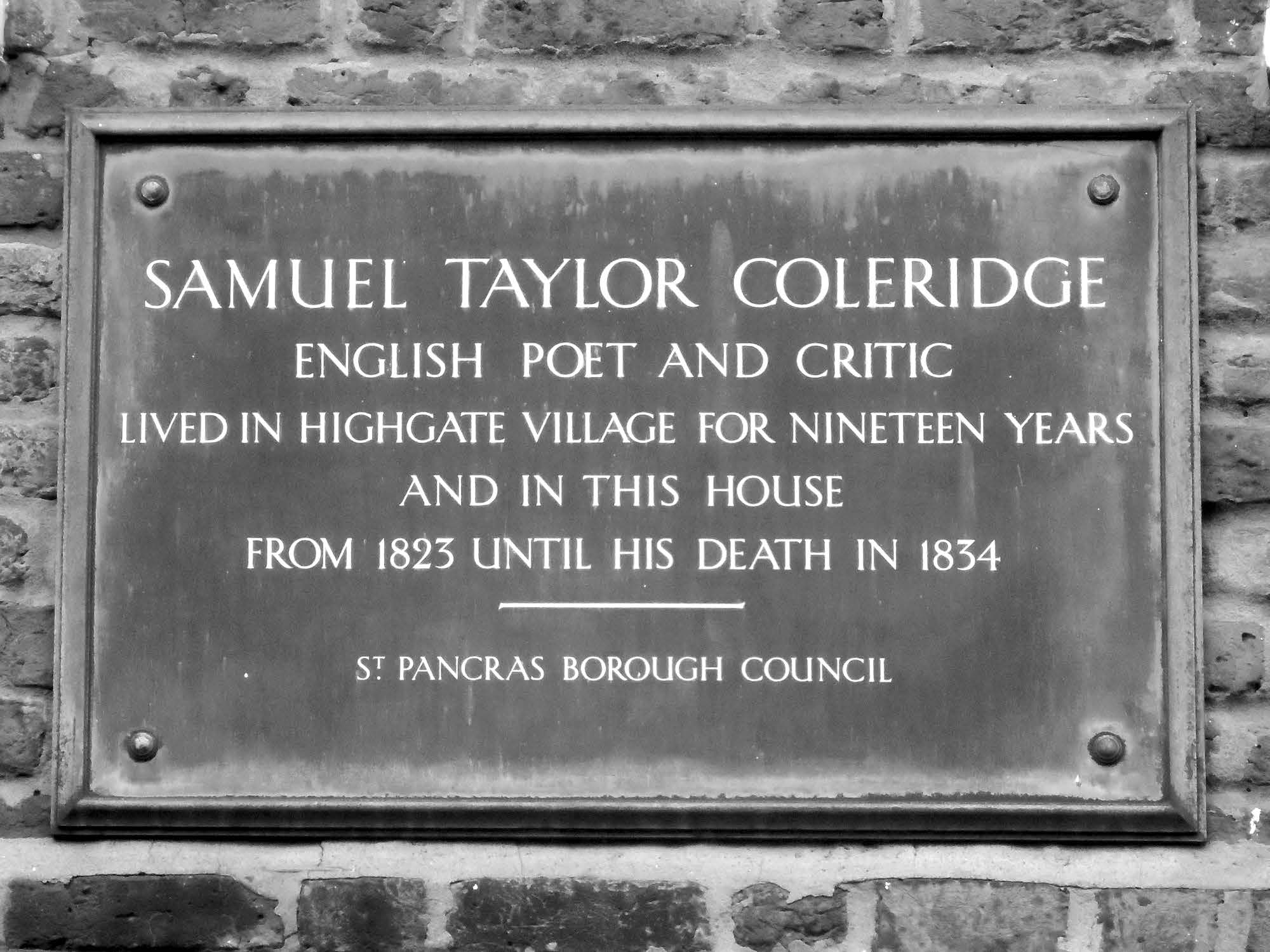

Bronze plaque erected by St Pancras Borough Council.

Bronze plaque erected by St Pancras Borough Council.

Conclusion

Coleridge’s health took a dramatic turn for the worse in 1830, and for his last three and a half years he was almost entirely bedridden. Yet his mind remained lucid and surprisingly active right up until the end. He died on 25 July 1834 at Highgate in the company of those who had nursed him back to health and sanity the last several years of his life. He is buried in Highgate Village churchyard. Less than a fortnight before his death, in one of his final letters to an old German friend, he summed up his life as follows: “I now on the eve of my departure, declare to you and earnestly pray that you may hereafter live and act in the conviction that health is a great blessing; competence, obtained by honorable industry, a great blessing; and a great blessing it is, to have kind, faithful and loving friends and relations. But the greatest of all blessings, as it is the most ennobling of all privileges, is to be indeed a Christian.”[86]

I give the final words to Charles Lamb, the one who knew him at his best times and at his worst and who once called him “an Archangel a little damaged”: “Never saw I his likeness, nor probably the world can see again.”[87]

Notes

[1] Coleridge, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” lines 614–17.

[2] Samuel Taylor Coleridge to James Gillam, 13 April 1816, in Griggs, Collected Letters, 4:630.

[3] Caine, Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 12.

[4] Samuel Taylor Coleridge to Poole, 16 October 1797, in Griggs, Collected Letters, 1:354.

[5] Caine, Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 16.

[6] Caine, Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 15.

[7] Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, 1:4.

[8] Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, 1:6.

[9] “To the Reverend W. L. Bowles,” lines 1–3, in Perry, Coleridge, 52.

[10] Ashton, Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 18.

[11] Perry, Coleridge, 10.

[12] Perry, Coleridge, 12.

[13] From “France, An Ode” (1797–98), lines 22–27, 39–42, as found in Bernbaum and Jones, Blake, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Lamb, and Hazlitt, 86–87.

[14] Caine, Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 48.

[15] Cottle, Reminiscences, 30.

[16] Campbell, Coleridge, 34.

[17] Beers, History of English Romanticism, 32.

[18] Frye, Study of English Romanticism, 3–14.

[19] Beers, English Romanticism, 252.

[20] In Germany, the transition came later and much faster through the writings of Lessing, Herder, Goethe, and Schiller, but in France barely at all. In America the Romantic impulse came later in the form of the Transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

[21] Perry, Coleridge, 41.

[22] Cottle, Reminiscences, 107.

[23] Caine, Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 62.

[24] William Wordsworth, “My Heart Leaps Up When I Behold” (1807), in Bernbaum, Anthology of Romanticism, 217.

[25] William Wordsworth, “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” (1807), in Bernbaum, Anthology of Romanticism, 233–34.

[26] William Wordsworth, “The World Is Too Much with Us: Late and Soon” (1807), in Anthology of Romanticism, 236.

[27] A second edition came out two years later with an explanatory preface and Wordsworth as the sole author.

[28] Wordsworth and Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads, xix.

[29] Wordsworth, “Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey,” lines 89–112, 114–15.

[30] The storyline owes much to George Shelrocke’s “Voyage Round the World by the Way of the Great Sea” (1726), which Coleridge had previously read and which tells of a sailor killing an albatross, an act his fellow sailors regarded as an ill omen. Perry, Coleridge, 44.

[31] Bernbaum and Jones, Blake, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Lamb, and Hazlitt, 64, lines 17–28.

[32] Lines 115–21.

[33] Lines 331–34.

[34] Lines 610–17, 85.

[35] When it was republished in 1800, with Wordsworth inexplicably listed as the sole author, the “Ancient Mariner,” which Wordsworth felt was hard for readers to understand, was placed at the back of the book.

[36] A second son, Berkeley, had died in infancy, and a fourth son, Thomas, would die in 1812.

[37] Cottle, Reminiscences, 273.

[38] Perry, Coleridge, 65.

[39] “Dejection: An Ode,” (1802), lines 21–24, 76–86, in Bernbaum and Jones, Blake, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Lamb, and Hazlitt, 131–32.

[40] Caine, Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 110.

[41] Campbell, Coleridge, 175.

[42] Perry, Coleridge, 101.

[43] Cottle, Reminiscences, 224.

[44] Cottle, Reminiscences, 53.

[45] Caine, Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 11.

[46] Cottle, Reminiscences, 57.

[47] Perry, Coleridge, 97.

[48] Cottle, Reminiscences, 221.

[49] Caine, Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 104.

[50] Campbell, Coleridge, 167.

[51] Cottle, Reminiscences, 274.

[52] “The Pains of Sleep” (1816), lines 14–20, 51–52, in Guide to Anthology of Romanticism, 137–38.

[53] Samuel Taylor Coleridge to Josiah Wade, 26 June 1814, cited in Cottle, Reminiscences, 292.

[54] Caine, Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 125.

[55] Griggs, Collected Letters of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 4:628–29.

[56] Coleridge to John Gale, 8 July 1816, as cited in Campbell, Coleridge, 221.

[57] Carlye, as cited in Hennelling, Coleridge’s Progress to Christianity, 33.

[58] Cited in Perry, Coleridge, 110.

[59] Ashton, Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 325.

[60] Woodring, Collected Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

[61] Holmes, Coleridge, 457.

[62] Holmes, Coleridge, 432.

[63] Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, 423.

[64] From René Wellek in Kant in England, 1793–1938, as cited in Blunden and Griggs, Coleridge Studies by Several Hands on the Anniversary of His Death 181.

[65] Ashton, Life of Samuel Taylor, 328.

[66] Holmes, Coleridge, 449.

[67] Carlyle, Life of John Sterling (1851), as cited in Holmes, Coleridge, 488.

[68] Coleridge, Aids to Reflection, aphorism 7, 130–31.

[69] Aids, 134.

[70] Aids, 125.

[71] Aids, 126.

[72] Aids, 70–71.

[73] Aids, 188.

[74] “Confessions of an Inquiring Spirit,” in Aids to Reflection, 296.

[75] Letter 4, “Confessions,” 315.

[76] Letter 7, “Confessions,” 334.

[77] Letter 7, “Confessions,” 335.

[78] “Confessions,” 189–91.

[79] “Confessions,” 194.

[80] “Confessions,” 175.

[81] Aids, 143–44.

[82] Aids, 154.

[83] Aids, 165–66.

[84] Aids, 200–201.

[85] Cottle, Reminiscences, 246.

[86] Samuel Taylor Coleridge to Adam Steinmetzkinnaird, 13 July 1834, as cited in Cottle, Reminiscences, 245.

[87] Charles Lamb, in Perry, Coleridge, 121.