The Returning Prodigal

Bruce A. Van Orden, "The Returning Prodigal" in We'll Sing and We'll Shout: The Life and Times of W. W. Phelps (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 295–312.

W. W. Phelps witnessed the desperate condition of rank-and-file Latter-day Saints in Caldwell and Daviess Counties after surrendering to the Missouri militia forces on October 31, 1838. First, soldiers stripped the innocents of their grain and livestock. After the army left, non-Mormon raiders took over the marauding and robbed people of their properties. This was especially acute in Adam-ondi-Ahman, where militia commanders ordered the Saints to leave immediately for Far West, thus requiring them to lose their earthly goods. About a hundred women were without male support because their husbands had been taken as prisoners, killed in action, or forced to flee the state because of their “wanted” status. Furthermore, it was cold and snowy throughout much of the month, and many families had to endure terrible privation. Yet, even as bad as these circumstances were, the Saints still hoped that Missouri state leaders, especially in the legislature, would come to their senses and provide redress to the people and allow them to remain, at least in Caldwell County.[1]

Phelps Family in Far West

Phelps may have been temporarily reprieved from having his household attacked, but given his experiences in November 1833 of being exiled from Jackson County under similar conditions, his heart must have melted to witness the horrible depredations in front of his eyes. What could he do to help? Would anyone in Far West want his help? Maybe, he thought, he had gone too far to allow himself to be used by the Missourians in testifying at the Richmond court of inquiry.

As a cold and stormy November 1838 turned into a biting December in Far West, W. W. Phelps stood facing a chasm. He was nearly forty-seven years old. Unless one owned a farm or was already gainfully employed in some form of mercantilism or government service, men of that age in America could not look to an easy future financially. William had been a successful printer and newspaper publisher. But for whom could he work now? He had been economically sustained by the church, but nearly every loyal Latter-day Saint shunned him at this point. Years earlier, he had been close friends with members of the First Presidency—Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and Hyrum Smith—but they were now incarcerated. Phelps had been partly responsible for that by testifying at the hearing. They considered him nothing more than an ignorant traitor. The Twelve Apostles offered no hope. Those who remained loyal to Joseph Smith, now led by Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball, wanted nothing to do with Phelps. Those who had fallen away—Thomas Marsh, Orson Hyde, William McLellin, Lyman Johnson, Luke Johnson, and John Boynton—were not his friends, at least not now. Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, John Whitmer, and all other Whitmers, “dissidents” of June 1838 now living in Richmond, probably would have taken Phelps into their circle. Maybe he could eke out a living among them and their families. Also, Phelps was still a friend to George Hinkle, John Corrill, Reed Peck, Frederick G. Williams, Burr Riggs, and John Cleminson, who had adhered to the middle of the road with him in the recent conflict between the church and the Missourians. Could they do something together? Most of them, Phelps included, still held property in or near Far West.

Phelps had a family to consider. They needed to be fed and cared for. What about their religious upbringing? Heretofore, Phelps had known nothing but religious devotions within the family circle. But what kind of religious feelings should he give his family now? William and Sally had lost to death their little Princetta the previous August 31 and probably still mourned her loss. Sabrina (twenty-two) had been married since July 1837. The others were Mehitabel (or “Hitty,” age nineteen), Waterman (nearly sixteen), Sarah (thirteen), Henry (ten), James (six), and Lydia (three).

Could they go live with extended family on either William’s or Sally’s side? William had lost nearly all contact with his parents and siblings back in Cortland County, New York. Sally’s family lived in Ohio, and she had maintained somewhat better contact. Perhaps there was a future back in Ohio.

No doubt William and Sally went into the new year of 1839 contemplating and praying about what course their lives and those of their children should take. What would happen to the Mormon people, those whom he had previously shepherded and counseled? Virtually no surviving records, letters, or reminiscences exist from either William or Sally from December 1838 to April 1839. We can only ascertain their decision-making by what course they ended up taking and by observing what course William’s friends took.

Saints Exiled to Illinois

By January 1839, the Saints and their leaders came to realize that their hopes for redress from the state legislature had come to nothing. They would have to leave the state; they had no other recourse.[2]

In Far West, with the First Presidency as well as many other leading Mormon men in jail, it fell to the Twelve Apostles to openly lead the church and its people. The Saints surely needed skilled and creative shepherds to guide them in their day-to-day needs and in organizing their exile from Missouri. Bishop Edward Partridge was critically ill and not in a position to help others.

Brigham Young leaped into action. He presented before the Saints a resolution stipulating that each member would “stand by and assist” his neighbor and would “never desert the poor who were worthy, till they shall be out of reach of the exterminating order [i.e., safely out of Missouri].”[3] A formal covenant was drawn up, and most of the people signed it and covenanted all their available assets to help each other leave the state. By the end of April, nearly all worthy poor were gone from Far West. Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and John Taylor, along with other heroes, oversaw removing more than ten thousand Latter-day Saints to safety. Most gathered to Quincy and surrounding locations in Adams County, Illinois, where they were generously aided with housing and employment.

Brigham Young called a conference for Sunday, March 17, 1839, in Quincy. He reported on the conditions in Far West and urged that further strenuous efforts were required to bring all the members to safety. At the conference, George W. Harris of the high council “made some remarks relative to those who had left us in the time of our perils, persecutions and dangers, and were acting against the interests of the Church [i.e., Phelps and others]; he said that the Church could no longer hold them in fellowship unless they repented of their sins, and turned unto God.” The minutes then recorded, “After the conference had fully expressed their feelings upon the subject it was unanimously voted that the following persons be excommunicated from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, viz.: George M. Hinkle, Sampson Avard, John Corrill, Reed Peck, William W. Phelps, Frederick G. Williams, Thomas B. Marsh, Burr Riggs, and several others.”[4] Phelps’s excommunication was his second. Hinkle, Avard, Corrill, and Peck would never return to the church. Williams and his son-in-law Riggs would come back within a few months, and Phelps would return to the fold in the summer of 1840. Marsh, after many years apart, would make his way to Utah and the church in 1857.

W. W. Phelps in Far West in 1839

What did W. W. Phelps do in the forepart of 1839? At least a part of his interest was in helping solve problems in Far West. He and others desired to sell their properties, but there were few takers since it was so easy for intruders simply to take over empty houses and lands. In a letter to John P. Greene, one of Joseph Smith’s financial agents, on April 23, 1839, Phelps indicated that the committee for the removal of the poor had finished their work in Far West. He also offered to sell more properties of the Saints to help with their finances. He even suggested that he be given “power of attorney” for Joseph Smith Sr., even as he held that authority for John Corrill, and thus sell some of “Father Smith[’s]” assets. Phelps also indicated that he had promised Hyrum Smith that he would do the same for Hyrum’s family.[5]

Joseph Smith, recently escaped from incarceration in Missouri, and not Greene, angrily responded personally to Phelps on May 22, 1839. He still considered Phelps an enemy.

In answer to yours of 23rd April to John P Green[e] we have to say that we shall feel obliged by your not making yourself officious concerning any part of our business in the future. We shall be glad if you can make off a living by minding your own affairs, and we desire (so far as you are concerned) to be left to manage ours as well as we can. We would much rather loose our properties, than be molested by such interference, and as we consider that we have already experienced much over officiousness at your hand, Concerning men and things pertaining to our concerns, we now request once for all, that you will avoid all interference in our business or affairs, from this time henceforth And for ever. Amen.[6]

Phelps wrote a seven-page letter to his wife on May 1, 1839.[7] Evidently, Sally had been gone from Far West for about a month and was temporarily living in St. Louis. William mentioned that he had under his care the three youngest children: Henry (ten), James (six), and Lydia (four). William reported that Waterman (sixteen) had gone to Liberty to find work. Although not explicitly stated, the females who were teenagers or older had gone with Sally to St. Louis.[8] Maybe this was for their personal safety. Numerous Mormon women had been molested in northern Missouri during the exodus.

William chided Sally for not writing since her letter to him a couple of weeks earlier. Did she not know how the postal system worked? William indicated that he was preparing to move, but there were still many challenges. He hoped to settle his financial affairs and sell off his house and properties, a project he did not succeed at for lack of buyers. He also had livestock to take care of. Again and again he mentioned how lonesome he was for Sally, but he was also terribly lonesome in general—he felt empty inside since having seen most of his former colleagues leave his life, perhaps forever. The three young children missed their mother and yearned to be back with her. Filled with “melancholy,” he commented to Sally, “I hardly know what to say, but I hope you are contented, and will wait patiently [for us to arrive]. Whether you write to comfort us or not, for God knows I want you happy whether I am or not.” William said that he would have his friend Reed Peck, who was planning to go through St. Louis soon, check in on Sally.[9]

Phelps also wrote of his observations. He had just heard that Joseph Smith and his fellow prisoners had successfully escaped incarceration. Phelps believed the rumor that Smith had bribed the guard with six thousand dollars. He had witnessed or heard of the quick-by-night visit to Far West of seven of the Twelve Apostles in the early morning of April 26, 1839. A revelation (D&C 118) had directed the Twelve to meet at the Far West Temple site on that very day to leave for their mission to Europe. To fulfill the revelation, Brigham Young led a company of seven apostles and other men on horses to Far West. These seven apostles excommunicated a number of members who had stayed in Far West and were current dissidents. They sang the hymn “Adam-ondi-Ahman” (composed by Phelps, ironically), prayed, and were soon on their way. Sarcastically, Phelps wrote:

This looks a little like choosing or loving darkness rather than light because their deeds are evil. You know I think as much of pure religion as ever, but this foolish mocking disgusts me, and all decent people. Force the fulfillment of Jo’s revelation! You might as well dam the the [sic] waters of [the] Missouri River with a lime siddle [saddle?]! It was undoubtedly done to strengthen the faith of weak members, and for effect abroad: as I understand the Twelve are a going to try their luck again among the nations: Tis really a pity they cannot get a looking glass large enough to see the saw log in their own eyes while they are endeavoring to pull the slab out of the neighboring nations. All I can say is: “Physician save thyself!”[10]

William passed on other news that might interest Sally. John Whitmer, cofounder of Far West with Phelps in 1836, had returned to his home in Far West.[11] Whitmer would live out his life in Far West and die there in 1878.

In a melancholy vein, Phelps observed how much had changed in Far West:

There is such a wide difference in the aspect and prospect of Far West, that I hardly know how to describe it to you. The inhabitants are gone. The sound of the hammer, and the bustle of business have ceased; The grass is growing in the streets, or where they were: The fences have disappeared, and nothing but empty houses, and the moaning of the Spring breeze, tell what was in Zion (so revealed.) My love of it has vanished.[12]

William had not lost his touch for poetry. He penned a thoughtful poem in honor of his marriage to Sally:

’Tis sweet to think of days gone by,

When hope expected pleasures double,

Would leave no room for care or trouble;

When love was sparkling in thine eye,

And roses bloom’d upon thy cheek,

And all thy words and ways were meek:—

When married life was truly pleasant;

And all the varied pass’d and present—

Time, had not evil tales to tell

Of you and I—so all is well.

…………………………….

’Tis sweet to think of days to come,

And bid adieu to earthly leaven,

And be, O be always at home:—

Where none are known but real friends,

And love and beauty never ends;

And where united life is pleasant—

And all eternal pass’d and present—

Time, has no evil tales to tell

Of you and I, So all is well.[13]

If a rift in their relationship had led to their separation, this tender poem attests that William was clearly striving to repair it.

The documentary trail for the Phelps family is lost for several months—up through March 1840. Presumably, William brought Waterman back from Liberty and took him and the other three children to St. Louis to be with the rest of the family. How long they remained in St. Louis is not known. William, who had left Far West without selling off his properties, may have sought employment in St. Louis.[14]

The Phelpses in Dayton, Ohio

Sometime in late 1839 or early 1840, the Phelps family moved on to Ohio. Available evidence shows that Sally had a first cousin named John Waterman living in or near Dayton. Likely the Phelpses moved to this area at John’s invitation.[15]

In a March 1840 letter from Phelps to his friend John Whitmer, we gather that William and Sally were not sure where they might permanently settle. (A preceding letter from Whitmer to Phelps is not extant.) William’s letter is informative about his family’s bouts with sickness, indebtedness, and poverty. He also remembered fondly his associations with Whitmer and the early Saints. Phelps wrote from Bellbrooke, located about ten miles east of Dayton. His remarks are included here to demonstrate his state of mind and contemporaneous circumstances.

On my return from the north the other day, where I had been looking for a resting place, I called at Dayton and found a letter from you which brought “Old times home again”. Having hardly recovered from my long illness and that of my family—and being in poverty without money, or as yet a resting place, you will have to excuse all my neglects, &c.

The happy days we have passed in Sweet communion together, are gone . . . but hope, precious hope, with me abides, and, I trow [think], with you too.

I might say much if I had time and Space but it Suffices that I long for the days when we can do as we used to, enjoying ourselves in a happiness that does not exist only where “brethren dwell together in unity”. Say what you will of the world, and think what you may of the Church of Christ, when new members walked in the path marked out by the finger of God, the world has not Joys as pure as hers.

As to the debts we contracted, I have ever done and meant to do my part. . . .

I am about to start east [perhaps to find living quarters near other Waterman relatives] in quest of a home where we can rest a while—as soon as we can move I shall write to you, and then the whole concern can be finished. . . .

You have a desire to know what kind of sickness were afficted with: The answer is: I had several disorders but the chills and fever were the worst. My wife had the Billous [bilious] fever—&c Waterman fever and Ague, and inflammatory Dysentary Sarah two or three disseases and the chills & fever, and so on.[16]

The Phelpses evidently decided to stay in the Dayton vicinity because they were there in June 1840. Dayton had about six thousand inhabitants at this time. It was a bustling community because of the Dayton-to-Cincinnati Canal that had been completed in 1829. Dayton boasted a number of plants that produced guns, hats, iron plows, silk, wool, flour, paper, machinery, furniture, stoves, carpets, clocks, and pianos. Phelps probably thought he could find employment there, perhaps at a business owned by his cousin-in-law John Waterman. No newspapers in Dayton before 1844 are extant to verify what Phelps might have done there in that business.

The Phelpses’ second daughter, Mehitabel, was twenty-one in the summer of 1840. She married her husband, Willis C. Fallis, in Dayton on October 25, 1840. Fallis wasn’t a Mormon. Willis and Hitty moved numerous times throughout Indiana and Missouri. She died in St. Louis from effects of asthma on May 13, 1877.[17] Maybe she moved to St. Louis to be near her sister Sabrina. Neither Sabrina nor Hitty lived anywhere near their father and mother when William and Sally came back to the church in 1840 and made their way to Nauvoo in 1841. Evidently, Sabrina and Hitty became disenchanted with Mormonism after the problems the Phelps family passed through from 1837 to 1840.

William W. Phelps endured the so-called buffetings of Satan from late 1838 up through the summer of 1840. In his December 16, 1838, letter from Liberty Jail to the Saints in Far West, Joseph Smith wrote about the dissenters, including by name W. W. Phelps: “We say unto you dear brethren, in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ, that we deliver these characters unto the buffetings of satan until the day of redemption that they may be dealt with according to their works and from henceforth shall their works be made manifest.”[18] The Phelps family was still impoverished in June 1840 when William met up with apostles Orson Hyde and John E. Page in Dayton.

Phelps Accepted Back into the Church

Orson Hyde, who had cosigned an affidavit in October 1838 along with Thomas Marsh attacking Joseph Smith, had since repented and come back to the church. He partly blamed his delirious illness on his joining up with Marsh. When Hyde recovered, he went to his friend Heber C. Kimball of the Twelve and wept bitterly about his mistake. Kimball spoke with both Brigham Young and Joseph Smith, and Orson Hyde was returned to full fellowship and regained his position in the Twelve Apostles. By 1840 Orson Hyde and John E. Page were under way to Jerusalem on assignment from Joseph Smith to dedicate the Holy Land for the return of the Jews to the lands of their inheritance.

William W. Phelps evidently learned of Hyde and Page’s presence in Dayton, where they were there spending a few weeks preaching and baptizing. He went to them and asked for forgiveness and the chance to come back to the church. The poignant reunion and Phelps’s acceptance back into the church are found in an exchange of letters with Joseph Smith. They are recounted here in full because of their significance.[19]

Orson Hyde and John E. Page wrote Joseph Smith on June 29, 1840:

Dear Brother:—We have been in this place a few days, and have preached faithfully, a very great prospect of some able and influential men embracing the faith in this place. We have moved along slowly, but have left a sealing testimony. Baptized a considerable number. We shall write again more particularly as soon as we learn the result of our labors here. We are well and in good spirits through the favor of the Lord.

Brother Phelps requests us to write a few lines in his letter, and we cheerfully embrace the opportunity. Brother Phelps says he wants to live, but we do not feel ourselves authorized to act upon his case, but have recommended him to you; but he says his poverty will not allow him to visit you in person, at this time, and we think he tells the truth. We therefore advise him to write, which he has done.

He tells us verbally that he is willing to make any sacrifice to procure your fellowship, life not excepted, yet reposing that confidence in your magnanimity that you will take no advantage of this open and frank confession. If he can obtain your fellowship he wants to come to Commerce [Nauvoo] as soon as he can. But if he cannot be received into the fellowship of the Church, he must do the best he can in banishment and exile.

Brethren, with you are the keys of the Kingdom; to you is power given to “exert your clemency, or display your vengeance.” By the former you will save a soul from death, and hide a multitude of sins; by the latter, you will forever discourage a returning prodigal[,] cause sorrow without benefit, pain without pleasure, [and the] ending [of Brother Phelps] in wretchedness and despair. But former experience teaches [us] that you are workmen in the art of saving souls; therefore with greater confidence do we recommend to your clemency and favorable consideration, the author [of the foregoing] and subject of this communication. “Whosoever will, let him take of the waters of life freely.” Brother Phelps says he will, and so far as we are concerned we say he may.

In the bonds of the covenant,

Orson Hyde,

John E. Page.[20]

Actually, the Hyde and Page letter above was an addendum to William W. Phelps’s letter. William’s letter to Joseph Smith from June 29 follows:

Brother Joseph:—I am alive, and with the help of God I mean to live still. I am as the prodigal son, though I never doubt[ed] or disbelieve[0] the fulness of the Gospel. I have been greatly abused and humbled, and I blessed the God of Israel when I lately read your prophetic blessing on my head [in 1835 in Kirtland], as follows:

“The Lord will chasten him because he taketh honor to himself, and when his soul is greatly humbled he will forsake the evil. Then shall the light of the Lord break upon him as at noonday and in him shall be no darkness,” &c.

I have seen the folly of my way, and I tremble at the gulf I have passed. So it is, and why I know not. I prayed and God answered, but what could I do? Says I, “I will repent and live, and ask my old brethren to forgive me, and though they chasten me to death, yet I will die with them, for their God is my God. The least place with them is enough for me, yea, it is bigger and better than all Babylon.” Then I dreamed that I was in a large house with many mansions, with you and Hyrum and Sidney, and when it was said, “Supper must be made ready,” by one of the cooks, I saw no meat, but you said there was plenty, and you showed me much, and as good as I ever saw; and while cutting to cook, your heart and mine beat within us, and we took each other’s hand and cried for joy, and I awoke and took courage.

I know my situation, you know it, and God knows it, and I want to be saved if my friends will help me. Like the captain that was cast away on a desert island; when he got off he went to sea again, and made his fortune the next time, so let my lot be. I have done wrong and I am sorry. The beam is in my own eye. I have not walked along with my friends according to my holy anointing. I ask forgiveness in the name of Jesus Christ of all the Saints, for I will do right, God helping me. I want your fellowship; if you cannot grant that, grant me your peace and friendship, for we are brethren, and our communion used to be sweet, and whenever the Lord brings us together again, I will make all the satisfaction on every point that Saints or God can require. Amen.

W. W. Phelps.[21]

As he had done countless times before, William referred to a dream he had had to help formulate his feelings. Moreover, he was completely humble in asking for forgiveness. His contrition appeared to be genuine. Many people, when they apologize, might say, “I am sorry if my words or my actions offended you.” Instead, Phelps said, “I have done wrong and I am sorry. The beam is in my own eye. I have not walked along with my friends according to my holy anointing.”

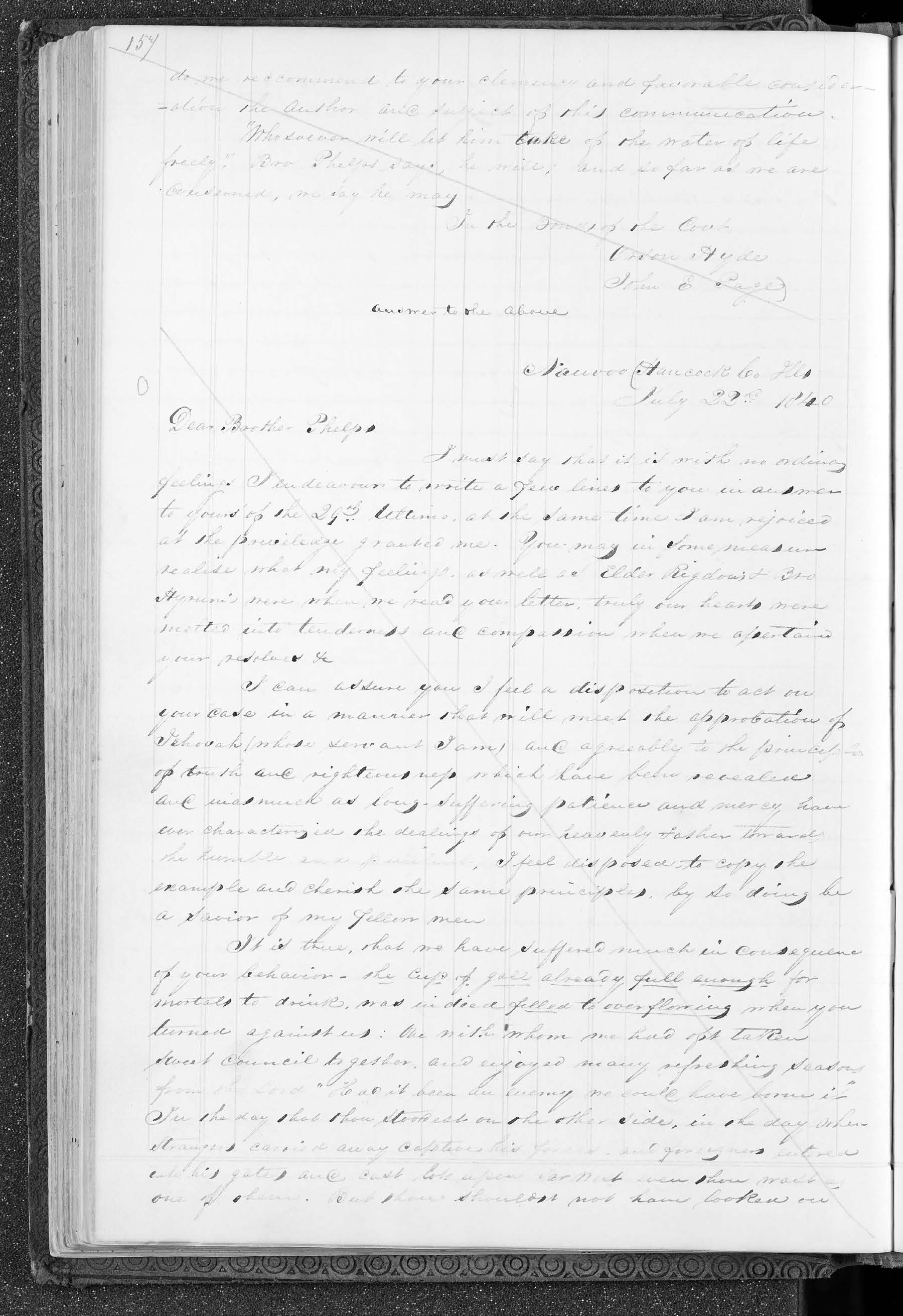

Joseph Smith’s dictated response was quick in coming, on July 22, 1840. He had Phelps’s letter in hand probably less than ten days before responding. He used the few days to pray, ponder, and confer with the other members of the First Presidency, Sidney Rigdon and Hyrum Smith.

Dear Brother Phelps:—I must say that it is with no ordinary feelings I endeavor to write a few lines to you in answer to yours of the 29th ultimo; at the same time I am rejoiced at the privilege granted me.

You may in some measure realize what my feelings, as well as Elder Rigdon’s and Brother Hyrum’s were, when we read your letter—truly our hearts were melted into tenderness and compassion when we ascertained your resolves, &c. I can assure you I feel a disposition to act on your case in a manner that will meet the approbation of Jehovah (whose servant I am), and agreeable to the principles of truth and righteousness which have been revealed; and inasmuch as long-suffering, patience, and mercy have ever characterized the dealings of our heavenly Father towards the humble and penitent, I feel disposed to copy the example, cherish the same principles, and by so doing be a savior of my fellow men.

It is true, that we have suffered much in consequence of your behavior—the cup of gall, already full enough for mortals to drink, was indeed filled to overflowing when you turned against us. One with whom we had oft taken sweet counsel together, and enjoyed many refreshing seasons from the Lord—“had it been an enemy, we could have borne it.” “In the day that thou stoodest on the other side, in the day when strangers carried away captive his forces, and foreigners entered into his gates, and cast lots upon Far West, even thou wast as one of them; but thou shouldest not have looked on the day of thy brother, in the day that he became a stranger, neither shouldst thou have spoken proudly in the day of distress.”[22]

However, the cup has been drunk, the will of our Father has been done, and we are yet alive, for which we thank the Lord. And having been delivered from the hands of wicked men by the mercy of our God, we say it is your privilege to be delivered from the powers of the adversary, be brought into the liberty of God’s dear children, and again take your stand among the Saints of the Most High, and by diligence, humility, and love unfeigned, commend yourself to our God, and your God, and to the Church of Jesus Christ.

Believing your confession to be real, and your repentance genuine, I shall be happy once again to give you the right hand of fellowship, and rejoice over the returning prodigal.

Your letter was read to the Saints last Sunday, and an expression of their feeling was taken, when it was unanimously

Resolved, That W. W. Phelps should be received into fellowship.

“Come on, dear brother, since the war is past,

For friends at first, are friends again at last.”

Yours as ever,

Joseph Smith, Jun.[23]

This response is one of the most-quoted statements of Joseph Smith in the twenty-first century in popular literature, church classes, and talks across the pulpit.[24] It is used to demonstrate the forgiving spirit and compassion of the Prophet. It shows that Joseph with God’s help was able to reclaim a useful servant who would go on to assist the kingdom of God profitably in years to come. Smith indicated how deeply Phelps’s words and actions had hurt him and his fellow sufferers in jail. But he did not allow that to poison his thoughts toward one who was evidently as contrite as Phelps had become.

Joseph Smith’s letter to W. W. Phelps, July 22, 1840. Courtesy of the Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Joseph Smith’s letter to W. W. Phelps, July 22, 1840. Courtesy of the Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

One can only wonder how circumstances might have been different if Joseph Smith and his closest colleagues in the First Presidency and the Twelve Apostles in Nauvoo had carefully and repeatedly reached out to many other dissidents, who had been just as close to the work as was Phelps. If Oliver Cowdery, Martin Harris, David Whitmer, John Whitmer, Lyman Johnson, George M. Hinkle, and John Corrill, who obviously were all good and honorable men, could have returned to the fold in Joseph Smith’s lifetime, wonderful results could have followed.

Phelps compared himself to the prodigal son spoken of by Jesus Christ in Luke 15:11–32 in the New Testament. Joseph Smith referred to Phelps as a prodigal as well. Two major differences from Jesus’s parable is that Phelps did not ask for money, nor did he squander his life in “riotous living.” However, like the prodigal, William became impoverished. He was willing to make penance and go back to the fold as nothing more than a “hired servant.” Like the lost son, William was embraced back into the fold and allowed to participate once more as an equal in the family of God. When Latter-day Saints refer to the parable of the prodigal son in various lessons or sermons in the modern era, often they will retell the story of Phelps coming back to the church and Smith exhibiting the same type of forgiveness as the father in the parable.

Times and Seasons and Mission to the East

It is unclear whether or not Phelps was rebaptized or if the ordinance was even considered necessary. We know he remained for several months in Dayton. Once he knew that he was accepted back into the church, Phelps started receiving copies of the church’s new Nauvoo newspaper, the Times and Seasons. He maintained a correspondence with Editor Don Carlos Smith, younger brother to the Prophet. D. C. Smith, as he went by in the newspaper, requested that Phelps write articles for the paper. Smith identified individuals in other states and in Britain as “agents” of the Times and Seasons. W. W. Phelps served as a Times and Seasons agent for Dayton, Ohio. Editor Smith regularly implored the agents to send him money for subscriptions in certificates of deposit or checks. Phelps indicated in one letter to Smith that he was actively gathering subscriptions.

Through the Times and Seasons, W. W. Phelps learned of the death of Bishop Edward Partridge in Nauvoo on May 27, 1840. Partridge was only forty-six. For many years, Partridge had suffered from ill health exacerbated by his arduous work of handling finances and caring for the poor, being whipped and tarred and feathered in Independence, being briefly imprisoned in November 1838, and being exiled from Clay County in 1836 and from all of Missouri in 1839. As soon as he belatedly learned of his friend’s death, Phelps opened his heart in a post to Don Carlos Smith that demonstrated his tender feelings and his hope for eternal life:

The death of br. Edward Partridge (in that paper) struck me with deep solemnity. Since 1831 we had passed through many trying scenes, and he ever proved himself a faithful friend. His private and official duties were performed with an eye single to the glory of God. He was faithful stew- [steward] and the church had unlimited confidence in his integrity. He lived Godly in Christ Jesus, and suffered persecution. As a Bishop he was one of the Lords great men, and few will be able to wear his mantle with such simple dignity. He was an honest man, and I loved him.

When the first Elders went along with br. Joseph to the western boundaries of Missouri, to seek the land of Zion, for the gathering of the saints in the last days, he and I was in the little band; when that goodly land was consecrated, we kneeled together; when the first house was raised, he and I help[ed] carry the first log; when the mob first rose to drive the saints from their inher[1]tances in Jackson co. and six of us offered our lives for the church, he was one; and for his faith, virtue, knowledge, temperance, patience, godliness, brotherly kindness and charity, he was stript on the public square, and tarred and feathered in this boasted land of liberty; by all Jackson co. (except the saints) for which God’s will be done; when we were driven out in 1833, and escaped in the night for our lives, into Clay co. he and I went hand in hand: we were anointed together at Kirtland, and came home together; when Caldwell co. was searched out he and I did it; we made the first prayer to God on that goodly land that had been for about fourteen hundred years; [referring to Book of Mormon peoples] and saw a glory that will yet cover the saints “as a clear heat upon herbs,” we lived together in peace, and our communion was sweet; although we often rebuked each other in plainness and had snaps according to passion, yet, like the used key, our friendship was bright and moistened with tears.

Lord thine anointed was a just man, and precious in thy sight, was his death! His name will be had in everlasting remembrance, while his enemies will be struck out of existence: so let me say:—

Our Father in heaven, whom all saints rely on, Exalt ye to glory the Bishop of Zion, As an heir to dominion, and power and might; The called and chosen, and faithful, is worthy To rise from a Saint to an angel of light.[25]

D. C. Smith dedicated several pages of his February 1, 1841, issue of the Times and Seasons to William W. Phelps. Don Carlos commended Phelps by comparing him to the Apostle Peter, who had denied the Christ but then repented sincerely and went on to great service. “We believe that Elder Phelps has a great work yet to do, and let the Saints hold him up by the prayer of faith, and help him do it. We hope Elder Phelps will continue to contribute his favors and they shall have a place in our little sheet.”[26] D. C. Smith’s desire for Phelps to reenter the writing profession was key to Phelps’s role starting later that year in writing for and helping edit the Times and Seasons.

Phelps entitled an essay “Despise Not Prophesyings.” As earlier in his ministry, he defended the restored gospel and the Prophet Joseph Smith. Phelps decried the belief of “the mother of harlots, and her daughters” that there was no need in the modern age for prophets and prophesying. He asked the question, “What is the use of prophets? My plain answer is this:—To reveal the will of God, and perfect the salvation of man. From this simple answer the conclusion is natural, that God never had a church without a prophet in it.” Phelps testified that the “restitution of all things” had taken place as “prophesied of by all the holy prophets, from Adam to Joseph [Smith].”[27]

W. W. Phelps sent another article to the Times and Seasons, entitled “Pray without Ceasing,” that was published on June 15, 1841. He wrote, “Prayer is the sacred coin of the heart which buys blessings, and should be offered freely to God twice, if not thrice, a day in public and private; at home and abroad; on the land and the sea; in sickness and in health.”[28] William appeared to have returned to his native spirituality.

Phelps continued as an agent for the Times and Seasons in Dayton until April 1841. In the first half of that month he moved with his family to Kirtland, where approximately four hundred Saints were still living. He became the agent for the newspaper in Kirtland and also helped care for the temple that he loved but that was falling into disrepair.

On May 22–24 an official Latter-day Saint conference took place in Kirtland under the direction of Almon Babbitt, who presided over the Saints there. Phelps served as clerk for the conference and sent the minutes to the Times and Seasons. Phelps mentioned that he was planning to serve a mission in the East and that he had spoken at length in the conference on the subject of baptism for the dead, a doctrine that had only recently been introduced to the Saints in Nauvoo by Joseph Smith.[29]

Within a few days Phelps left Kirtland for his short-term mission. No reports are extant as to all the places he visited. High on his list was his home community in Cortland County, New York, to check on his extended family. He wrote a lengthy letter to Sally explaining the status of his family, particularly as it pertained to the gospel of Jesus Christ.

William’s letter to Sally indicates that he wrote her other letters as well and that he had taken sick in Rochester for a few days. “[I was not able to start] for Homer, till Saturday the 12th, and, on Monday the 14 at 6 o’clock P.M. I arrived to the astonishment and joy of my father’s family. I found my father helpless; had a fit of the Palsy two years and two months ago, which numbed half of his body and otherwise dibilitated him. Mother was well and hearty.” William filled Sally in on how all his siblings were doing and then of his father Enon: “My father lost his farm, and bought back fifty acres for $500.00, which has been paid, but in his helpless condition, as all his children are of age, and excepting Joshua, in the world and for the work [referring to his brothers who had moved away and seemed not to care much for the parents], he cannot do more than live.”

William was eager to inform Sally about his preaching the gospel to his family:

I found the seed of Mormonism sown ten years ago [likely by Phelps himself sometime in 1831], like the fire without wood, had gone out. . . . In the morning after my arrival I commenced my work and on Saturday, after four days talking, and diligent prayer, which was about the same as a four day meeting, we got into the wagon and went [to the Tioughnioga River] where I had the unspeakable Joy of baptizing my father (who I carried in my arms into water,) and my mother and my brother Joshua, while some of the rest of the family stood and cried. Joshua is a real Saint, for as soon as I commenced preaching he commenced searching the scriptures to see if I quoted correctly, and when he saw that I literally quoted and fairly explained the bible, he join’d with me and said, “O, it is Just so, William is right.”

William added that his parents, Enon and Mehitabel Phelps, bore “an excellent crop of patience in age, and sincerity of religion.” The entire Phelps family also spoke with fondness of Sally, “both as to [her] disposition and red cheeks.”[30] Likely this was William’s last visit to his family, unless he went to Cortland County in 1848 en route to or from Boston. His mother died in 1854 and his father in 1855. They were buried in a Baptist cemetery.

Times and Seasons and Nauvoo

What happened with W. W. Phelps after he left Cortland County in mid-June 1841? Clues from the Times and Seasons indicate that Phelps made a separate trip to Nauvoo and lived there for a few weeks from July to September, probably without his family, and then returned to Kirtland to retrieve Sally and the children for a permanent move to Nauvoo.

In February 1841, Editor Don Carlos Smith had invited Phelps to write regularly for the Times and Seasons.[31] Before leaving for his short-term mission, Phelps wrote another article that was published.[32] Conceivably, Don Carlos could have asked Phelps to make a report of events in the East as he observed them. An article appeared in the August 2, 1841, edition of the paper that bears marks of Phelps’s familiar style. It’s title—“War! War!! and Rumors of War!!!”—indicates Phelps’s propensity for enthusiasm and hyperbole. The first two paragraphs follow:

Never since the rise of this church, have such interest and intense anxiety been manifested in the public mind, particularly on the sea-board. The falsehoods that have been circulated respecting us, being arrayed in the garb of truth, and having been published from the sacred desk by the reverend clergy with all the weight of sanctity which their long faces are calculated to inspire, and having found their way into the popular newspapers of the day, and circulated to the four winds, render it impossible for us to correct the public mind on the subject.

From the newspapers we have seen—the letters we have received—and the testimony of gentlemen who have just returned from the east, we are assured that rumor, with her thousand tongues, is at work, expectation is on the tiptoe, curiosity is on the stretch, all eyes are turned to the Far West, and all are anxious to hear the last accounts from the seat of war.[33]

More than other members, Phelps was aware of what other American newspapers had been writing about Mormonism. He was astounded at the newest phenomenon of eastern papers writing disparaging reports of the Mormons in Missouri. Having been on a recent mission to the East, Phelps was aware of references to Mormonism in the major papers. He knew that James Gordon Bennett, the editor and publisher of the New York Herald, which had the largest circulation of any newspaper in the land, could become a positive narrator of items pertaining to Mormonism. Subsequent events in Nauvoo would demonstrate that Phelps would cultivate a respectful relationship with Bennett. In future years, with Phelps’s help, Mormons indeed would receive favorable coverage in the Herald.

The article ended with an attack on the “Warsaw Junto,” which was the anti-Mormon group then just forming under the direction of Warsaw residents and newspapermen Thomas Sharp and Thomas Gregg. From that point on, Phelps would write in Nauvoo newspapers obsessively and vituperatively about Sharp, Gregg, and the so-called Anti-Mormon Party.

The next issue of the Times and Seasons, dated August 16, 1841, announced the sudden and totally unexpected death (likely from pneumonia) on August 7 of Don Carlos Smith, age twenty-five, who had been the coeditor or editor of the publication since its beginning in 1839. W. W. Phelps appears to have had a hand in publishing this issue, because his easily recognizable dingbat [an ornamental printing device]—a pointing finger—suddenly appeared in the paper. Phelps probably wrote two useful newsworthy pieces is this edition—“News from Abroad” and “Anti-Mormon Almanac.”[34] They certainly bespeak his style, enthusiasm, and specific interests.

Then, in the succeeding issue, dated September 1, Phelps wrote another article, one more recognizable as his own writing. He used his son’s name—“W. Waterman Phelps”—as a pseudonym. He wrote another piece a month later with the same pseudonym.[35]

The first piece was in honor of Robert B. Thompson, who had passed away only four days earlier, on August 27. Thompson had been coeditor with Don Carlos in the printing office. Phelps knew Thompson well from Far West, Missouri. In the printed eulogy, Phelps wrote words of praise about the deceased and that a “Merciful Providence who had given the church such a useful man, in his own wise purpose has taken him from us.” He urged readers to live uprightly so that “on the morning of the first resurrection, we may be found among those who have fought the good fight and been as firm and steadfast as our deceased brother.”[36]

Phelps’s second article using his son’s name dealt with falsehoods spread by the Anti-Mormon Party to the south in Warsaw as fomented by an archenemy of Mormonism, Thomas B. Sharp. Phelps sarcastically referred to Sharp as “the sapient editor of the Warsaw Signal” and pointed out Sharp’s numerous “palpable falsehoods.” Phelps, to show off his language skills, added some sarcastic Latin phrases.[37] Phelps wrote this article because the Saints feared being incorrectly labeled in the nation’s public press after reading an exchange paper from an editor who lived near Nauvoo. Correcting the record, so to speak, would become Phelps’s role again and again.

Sometime in September, likely after he wrote the above piece, W. W. Phelps returned to Kirtland to retrieve his family. He was present for an official church conference held in Kirtland on October 2, 1841. Phelps recorded the minutes and sent them on to the new and also former editor of the Times and Seasons, Ebenezer Robinson. At the conference, Phelps gave a discourse on his familiar theme of “Despise Not Prophesyings.”[38]

W. W. Phelps, Sally, and their unmarried children then prepared to emigrate to Nauvoo. They arrived at their new home sometime in late October or November 1841. They were warmly received by the Saints. Knowing William’s talents, Joseph Smith put him to work immediately. Phelps was now fifty years old. The future looked bright for the Phelps family once more.

Notes

[1] This tragic story and the documentation for it are found in Leland H. Gentry and Todd M. Compton, Fire and Sword: A History of the Latter-day Saints in Northern Missouri, 1836–39 (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2011), 447–62.

[2] Gentry and Compton, Fire and Sword, 462.

[3] MHC, vol. C-1, 881; HC, 3:250.

[4] MHC, vol. C-1, 898–99; HC, 3:284; JSP, D6:468, 468n187.

[5] See Joseph Smith Letterbook 2, Joseph Smith Collection, CHL, p. 7, available on the Joseph Smith Papers website; JSP, D6:468, 468n191; JSP, D7:303–4.

[6] JSP, D6:467–60.

[7] This letter has been published, along with a background to circumstances in Far West and Missouri generally, in Alexander L. Baugh, “A Community Abandoned: W. W. Phelps’ 1839 Letter to Sally Waterman Phelps from Far West, Missouri,” Nauvoo Journal 10, no. 2 (Fall 1998): 19–32. The original of this letter is located in the CHL, MS 667.

[8] Baugh, “Community Abandoned,” 25.

[9] Baugh, “Community Abandoned,” 25, 27.

[10] Baugh, “Community Abandoned,” 25–27; emphasis added. Phelps used the pejorative form “Jo” and wrote other deriding remarks, thus indicating his distaste at that time of what had happened in the church.

[11] Baugh, “Community Abandoned,” 25.

[12] Baugh, “Community Abandoned,” 26.

[13] Baugh, “Community Abandoned,” 25–26.

[14] Sabrina, the oldest child, likely stayed in St. Louis. Available genealogical records indicate that she and her husband lived out their lives there (see www.ancestry.com). Also of note is that Sabrina’s husband, Joseph Kilburn Bent, son of Mormon stalwart Samuel Bent, appears to have remained with the Phelps family and not with the Bent family, who migrated with the body of the Saints to Illinois in 1839. There is no evidence that Joseph or Sabrina Bent ever affiliated with the church after 1839.

[15] John Waterman, according to an article in Times and Seasons, was a member of the Dayton Branch (“Dayton, Ohio, October 8th 1842,” T&S 4 [November 1, 1842]: 13). Lyman Wight of the Twelve Apostles held a conference in the Waterman home on October 8, 1842. Presumably this John Waterman (born ca. 1805 in Watertown, Washington County, Ohio) was the oldest son of John Waterman (1768–1834), one of the founders along with other relatives of settlements in Washington County, Ohio. See Edgar Francis Waterman and Donald Lines Jacobus, The Waterman Family: Descendants of Robert Waterman (New Haven, CT: Edgar F. Waterman, 1939), 242–43, 493–94, 496–98.

[16] Letter of W. W. Phelps (Bellbrooke, OH) to John Whitmer (Far West, MO), March 4, 1840. Copies are available in the CHL, MS 667, and in L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. Underlining in original.

[17] See www.ancestry.com.

[18] “Communications,” T&S 1 (April 1840): 85; JSP, D6:309; emphasis added. For references to buffetings of Satan in the revelations, see D&C 78:12; 82:20–21; 104:9–10; and 132:26.

[19] The letters from Hyde, Page, and Phelps first appeared at the behest of Don Carlos Smith, editor of the Times and Seasons, in T&S 2 (February 1, 1841): 304–5. However, Joseph Smith’s return letter to Phelps did not appear in the Times and Seasons.

[20] JSP, D7:305–6; MHC, vol. C-1, 1066–67; HC, 4:142–43.

[21] JSP, D7:303–5; MHC, vol. C-1, 1066; HC, 4:141–42. They are in the hand of Robert B. Thompson, then assistant editor of the Times and Seasons, where the letters were then published. These letters are from “Joseph Smith Letter Book 2,” 155–57. Joseph Smith referred to Phelps’s missive in a letter to Oliver Granger wherein he stated that Phelps “appears very humble and is willing to make every satisfaction that Saints or God may require.” See “Letter to Oliver Granger, between circa 22 and circa 28 July 1840,” http://

[22] This phrase is a figurative application of Obadiah 1:11–12 in the Old Testament.

[23] JSP, D7:345–58; MHC, vol. C-1, 1082–83; HC, 4:162–64. Underlining and emphasis in original. This letter was originally recorded in “Joseph Smith Letterbook 2,” 157–58.

[24] A prominent example is “I know of no private document or personal response in the life of Joseph Smith . . . which so powerfully demonstrates the magnificence of his soul.” Jeffrey R. Holland, “A Robe, a Ring, and a Fatted Calf” (Brigham Young University devotional, January 31, 1984), speeches.byu.edu.

[25] “Extract of a Letter from W. W. Phelps,” T&S 1 (October 1840): 190; emphasis in original.

[26] T&S 2 (February 1, 1841): 304.

[27] W. W. Phelps, “Despise Not Prophesyings,” T&S 2 (February 1, 1841): 297.

[28] W. W. Phelps, “Pray Without Ceasing.—St. Paul,” T&S 2 (June 15, 1841): 451.

[29] “Minutes of a conference, held in Kirtland, Ohio, May 22nd 1841,” T&S 2 (July 1, 1841): 458–60.

[30] This letter of June 1841 is in WWPP; underlining in original.

[31] T&S 2 (February 1, 1841): 304.

[32] Phelps, “Pray Without Ceasing,” 451. Circumstantial evidence also points to Phelps’s authorship of two unattributed articles in July: “Dialogue on Mormonism. No. 1,” T&S 2 (July 1, 1841): 456–57; and “Dialogue on Mormonism. II,” T&S 2 (July 15, 1841): 472–74.

[33] “War! War!! and Rumors of War!!!,” T&S 2 (August 2, 1841): 495–97; emphasis in original.

[34] T&S 2 (August 16, 1841): 511–12, 513–14.

[35] These two articles do not reflect Waterman’s experiences at all, but rather those of his father. They are in Phelps’s writing style and reflect his interests. Waterman, age eighteen at that time, was still in Kirtland with his mother. Waterman was never identified as a writer in his lifetime.

[36] “Br. Robinson,” T&S 2 (September 1, 1841): 531.

[37] “Falsehoods Refuted,” T&S 2 (October 1, 1841): 562–63. Waterman Phelps could not have written this article because he was in Ohio and was not aware of the conflicts with Warsaw community leaders.

[38] “Kirtland Conference Minutes,” T&S 3 (November 1, 1841): 587–89; MHC, vol. C-1, 1228, 1242–43; HC, 4:443–44.