Helping Create Deseret

Bruce A. Van Orden, "Helping Create Deseret" in We'll Sing and We'll Shout: The Life and Times of W. W. Phelps (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 443–464.

Crossing the Plains

Traversing the plains, entering the mountains, and creaking through the canyons proved to be a stupendous task for more than 2,400 immigrants in 1848 to the Salt Lake Valley. Three huge companies headed respectively by Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and Willard Richards (the First Presidency) started in June to make their journey. Throughout the difficult months until late September, the companies often intermingled. The Phelpses were official members of Brigham Young’s party.

Phelps did not keep a record of the journey.[1] The trek demanded the best of both William and Sally as they cared for their children and handled the challenging oxen that pulled their wagon. Henry, eighteen, was a helpful hand. There was inevitable discord in the camp from time to time. The Phelps family dynamics were no doubt occasionally testy, particularly given a new polygamous relationship. William took his turn as a watchman at night. He would have found fulfillment in his frequent opportunity to speak at Sunday services.[2] Likely some of his hymns, such as “Adam-ondi-Ahman,” “The Spirit of God,” “Praise to the Man,” and “O God, the Eternal Father” (regarding the sacrament), were sung on the journey. On July 9 Phelps wrote a poem called “The Saints upon the Prairie” and had it sung at Sunday services.[3] Thomas Bullock reported “Story Teller” Phelps delighting “spellbound” young listeners in the evenings with his renditions.[4]

The Salt Lake Valley and surrounding valleys were no longer in Mexican territory. The Mexican-American War ended in February 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Virtually all of Mexico that is now in the United States, the current state of Utah included, was ceded with that treaty. Phelps would remain the rest of his life (twenty-one years) within present-day Utah boundaries.

Events in Early Deseret

These arriving pioneers found temporary refuge in the “Old Fort” that was created the previous year. Phelps and his sons quickly built an adobe house at the northwest corner of West Temple and First South Streets in Salt Lake City and continued to live there the remainder of William’s life. The well-known “Phelps schoolroom” became part of the Phelps residence.

William and Sally Phelps began teaching in the schoolroom as soon as it was available in January 1849. One of Sally’s students that year was Solomon Henry Hale, ten years old. “During the winter, [Solomon] had opportunity to attend a school taught by Mrs. W. W. Phelps. He had to go barefooted, as he had no shoes. The teacher would allow him to warm his feet in the ashes at the edge of the fireplace. His only book was an old ‘Elementary Speller.’”[5]

As he had done back in Winter Quarters, Phelps kept a daily “meteorological journal” of weather conditions in Great Salt Lake City.[6] His detailed weather records would come in handy in developing Deseret and Utah in subsequent years.

Phelps helped create the emerging identity of Saints in the West in the ever-enlarging community that went by the preferred title of “Deseret.” (The name Deseret comes from Ether 2:3 in the Book of Mormon—the Jaredite word for bees in a beehive, denoting industriousness on the part of the people.) Phelps’s contributions were significant in government, education, law, newspaper editing, weather recording, almanac publishing, poetry writing, and preaching gospel principles in those early Utah years. He would be involved, it seems, in all things “Deseret,” such as the Deseret News, the Deseret Almanac, the University of the State of Deseret, the State of Deseret general assembly (the legislature), the Deseret Theological Institute, the Deseret Horticultural Society, and the Deseret Alphabet. Phelps’s multiple activities during his first five years in Deseret were totally intertwined.

Council of Fifty

After arriving in the Salt Lake Valley in December 1848, Brigham Young convened anew the Council of Fifty, which became the de facto regime for all new settlements.[7] Phelps was in attendance and contributed to discussions on creating exploration parties, establishing property rights, and considering means to rid the community of “wasters” (wild animals and scavenger birds) that were harming the already-meager crops and cattle. He attended an important meeting on December 13 where it was decided that the citizens would send a petition for self-government to Congress.[8]

By February 9, 1849, the council had begun meeting for a time in Phelps’s schoolroom. On March 4 Phelps was placed on a committee to oversee the first elections in the State of Deseret and to create a state constitution.[9] On the same day he was also chosen to be on the state’s canal committee based on his experience with understanding topography. On March 10 Phelps presented to the council the list of men (all Mormon) to be elected to key provisional state positions. The election on March 12 would see no opponents, much as was the case back in Nauvoo. On March 10 Phelps also made a report on surveying results of the canal committee. In subsequent meetings Phelps continued to make reports of the ongoing progress of canal construction. The council named Phelps surveyor general and chief engineer on April 5.[10] On July 19 the Constitution of the State of Deseret, which Phelps helped create,[11] was ready to be sent east to Washington, DC, for consideration by Congress and the president. It was clear that the “Council of Fifty” evolved quickly into the governing bodies of the “State of Deseret.”

The government of the provisional State of Deseret, including its legislative general assembly, began operations in May 1849 and would continue until August 1851 (when the newly created Utah Territory was officially recognized). Phelps was a senator in the general assembly and served on several committees.[12]

After 1851, Brigham Young discontinued the Council of Fifty, although he could reconstitute it at any time. Phelps knew this, and when the State of Deseret was reconsidered in 1862, Phelps wrote Young, “As I am nearly the oldest member of the ‘Council of Fifty,’ when the state of Deseret is officered, I wish to be remembered.”[13]

Southern Exploration Mission

Governor Brigham Young called for settlement expansion throughout the massive boundaries of the “state.” As part of this expansion plan, Young authorized an exploration mission of about fifty men to the south of Utah County (named after the “Utah Indians” and where the city of Provo had been established) in quest of potential settlement sites. It was called the “Southern Exploration Expedition of 1849–1850” and was headed by apostle Parley P. Pratt, a member of the Council of Fifty.

Phelps was called as first counselor to Pratt, partly because he had already served as an official explorer. In August 1849, as part of an earlier discovery party into San Pete Valley, Phelps had scaled an enormous mountain south of Utah Valley that he had named Mt. Nebo.[14] That he climbed this mountain at age fifty-seven speaks well to his health and conditioning. This mountain turned out to be the highest mountain in the Wasatch Range, nearly twelve thousand feet above sea level. From that vantage point, Phelps looked out over several valleys, including what came to be known as Utah Valley, San Pete Valley, and Sevier Valley. Phelps sketched out a diagram or map identifying the various valleys and their relationships to each other and the surrounding mountains. This drawing ended up helping the Pratt exploration of southern regions. A cartographic expert described Phelps’s map:

What impressed one immediately about this map is how unconventional it appears from our modern perspective, standing out much like a primitive painting in a gallery of works by formalists. Painting is an appropriate word here, for Phelps’s map is actually rendered as a series of washes rather than a traditional map, in which lines determine form. The next thing that captures one’s attention is its stunning use of color, with the higher valleys in light green, the lower slopes of certain mountains in an oxide red, and the mountains in umber. . . . Another thing apparent is the map’s perspective, for it reflects Phelps’s vantage point on Mt. Nebo by placing that prominent geographic feather at the top.[15]

On November 17, 1849, the Council of Fifty heard Pratt’s report that more provisions were needed for the party’s grueling midwinter trek. This bold enterprise required money or contributions to provide “twelve wagons, one carriage, twenty-four yoke of oxen, seven beef cattle, thirty-eight horses and mules, and supplies that included trade items for the Indians, fifty pounds of flour for each man, crackers, bread, and meal, sixty pounds of coffee, an odometer, a brass cannon, and plenty of arms and ammunition.”[16]

Phelps’s assets were his unique training as a weather observer and surveyor. He also bore the designation of the company’s “topographical engineer.” The expedition was divided into five official “companies of ten,” harking back to Brigham Young’s January 1847 revelation to the Camp of Israel (D&C 136). Phelps kept the minutes of the organization meeting. The fifty men were carefully handpicked for their wilderness skills. The average age was thirty-five. Pratt was forty-two and Phelps fifty-seven.[17]

The expedition took off from Salt Lake County on November 24, 1849. They traversed valleys that would ultimately be Utah, Juab, Sanpete, Sevier, Millard, Beaver, Piute, Iron, and Washington Counties. The explorers endured numerous snowstorms, being occasionally snowed in, and frequent subzero (Fahrenheit) temperatures. Phelps faithfully kept weather, topographical, and latitudinal and longitudinal logs. As one of the older members of the party, Phelps suffered more than many of the skilled outdoorsmen. The men struggled to maintain their morale, and did so by singing, speechmaking, and dancing. Phelps, as would be expected, frequently gave lively speeches.[18]

The expedition proved to be exceptionally successful. The explorers identified twenty-six locations desirable for settlement. President Young sent settlers to most of them, many within the next three years. The brethren found fruitful coalfields near the future settlement of Richfield and iron ore deposits near the future settlements of Parowan and Cedar City.[19]

University of Deseret

Phelps participated in a number of early educational efforts in Deseret, most significantly the founding of the University of the State of Deseret. The state legislature created the university on February 28, 1850. Phelps had scarcely returned from his exploring when he was named one of the regents of the university. As with the University of Nauvoo, this “university” was considered an educational system for all ages of pupils, both youths and young adults. Phelps’s first main duty was to seek out schoolbooks for the elementary classes.

Willard Richards, secretary of the State of Deseret and a member of the church’s First Presidency, prepared a lofty charge to the chancellor and regents of the university on April 17, 1850. Richards outlined phenomenal heights to which the university should aspire and insisted that Mormon theology and truths should be the bedrock foundation of the university’s teachings.

We see then that a liberally endowed institution, is one that is able and every way qualified, to present free instruction, in all languages, arts, science, and intelligence, to all men, women, and children, who are looking, or have a right to look to the same, for the means of expending their mental and physical powers, until they are all qualified to act in any sphere of life where God and duty may call them; and acquiring all the intelligence that man is capable of possessing on earth; he may then with propriety receive his honorary diploma on real merit, and soar aloft among the Gods, where he may enter on new fields of science, enter a college of far more liberal endowments, and progress in intelligence through all eternity of eternities.[20]

These ideals matched Phelps’s exactly. Phelps probably had a hand in writing and publishing this charge.

Later in 1850, local citizens learned that Congress had not granted statehood to Deseret but rather territorial status under the name of “Utah Territory.” President Millard Fillmore appointed Brigham Young as governor. The newly identified territorial officials set up a complete governmental system, including a legislature consisting of both an assembly and a house of representatives. As far as the university and education system were concerned, the title shifted from the University of the State of Deseret to simply the University of Deseret. Many years later the university came to be known as the University of Utah.

On November 11, 1850, forty students enrolled in elementary classes of the university and began meeting in the adobe home of John Pack, located at the corner of Second North on West Temple. In 1851 classes moved to the Council House, or “state house,” and then to the Fourteenth Ward (Phelps’s ward) schoolhouse.[21] Orson Spencer, a distinguished college graduate and trusted priesthood leader, was the chancellor, and Phelps was the chief regent. They also created a “parent school” (also called a “normal school”) that would help prepare teachers for all of Utah. Prominent learned men such as Spencer, Phelps, Daniel H. Wells, Orson Pratt, Albert Carrington, and John M. Bernhisel taught at the parent school in the evenings. The First Presidency wrote in a “general epistle” to all the Saints, “The Parent school is in successful operation in the Council House under the tuition of Chancellor O. Spencer and Regent W. W. Phelps. The design of this school is to prepare its pupils to become teachers, and for all who may desire to advance in the higher branches of education. It is designed for the Parent school to be open continually.”[22]

In the Deseret News, Phelps reported on the first “Deseret Dance” that took place on “May Day” 1851 for students of the parent school. He boasted of the beauty and virtue of the participants. He described the young women thus:

Several parties of young ladies, beautifully attired in white, walked our streets and visited our canyons, (the free gardens of the mountains,) to decorate themselves with garlands of flowers, and evergreen sprigs, and relevantly act the queen; for they are all queens who do the will of God; so that a little praise cannot be misapplied to goodly models of the rising Deseretians.[23]

In the same edition of the paper, Phelps discussed a “public visitation,” or open house, that took place on May 9, 1851, designed to display the progress of the teenage pupils preparing to be teachers themselves. Chancellor Spencer and Regent Phelps were eager to show off the fruits of their teaching and by means of this newspaper report encourage others to enroll in future sessions. The students demonstrated their capacities in various disciplines and then read composed essays. “Many compositions were read, which as a whole, were of a higher order, a more exalted tone and sentiment, than we ever before witnessed in a similar school, and many of them would honor far older heads,” Phelps exulted. He added that their “singing appeared to us as a little foretaste of heaven.”[24]

Official notices about the University of Deseret in the Deseret News came out under the names of Chancellor Orson Spencer and Regent W. W. Phelps, the only men who regularly gave substantial time to administering the ever-growing school system.[25] In his bombastic way, Phelps indicated in a public speech on July 24, 1851, that university officials would not follow the ways of the world:

And what is expected of this board [of regents]? will they walk in the tracks of the Literati of the old world? Tie up the philosophy, wisdom, researches, classics and learned labors of six thousand years in a silken money purse? Fiddle for the pope, and dance for the devil? Hold the king’s stirrups, and kiss the emperor’s foot, crape the regions of light in black? Write upon the priest’s robe, mystery of mysteries? . . . No! No!! God forbid that these messengers of light shall ever blast their reputations, by stealing the sights from dead men’s eyes, to mystify the truth with. This is the sum of the matter: Up for heaven; down for hell.[26]

Sadly, crop failures, hard economic times, the need to receive new Mormon immigrants, and other church and territorial priorities hindered rapid growth of the university. The University of Deseret did not become solidified until the late 1860s and 1870s, when Phelps no longer was involved.

Deseret Alphabet

The most curious product of the University of Deseret was the “Deseret Alphabet.” Phelps was involved with this unusual project—helping create the characters and promulgating the alphabet.

The Deseret Alphabet originated with the baptism of George D. Watt in England. Watt, a student of the shorthand phonography invented in Britain by Isaac Pitman in 1837, immigrated to Nauvoo in 1842. Brigham Young took lessons from Watt in Nauvoo and was impressed with phonography. While Watt was in England on a mission in 1847, Young instructed him to bring back various phonographic materials (which now included “phonotypy,” the transcription of speech into printable phonetic symbols) created by Pitman. President Brigham Young promoted the creation of a somewhat similar Deseret Alphabet, and he decided that the University of Deseret would be the natural place for its conception.[27]

Throughout 1853, the Board of Regents, with Phelps a prominent member, frequently met to prepare a phonetic alphabet. They reached a consensus in December and planned to implement the alphabet in schools and among the public in 1854. Phelps reported:

The Board of Regents, in company with the Governor and heads of departments, have adopted a new alphabet, consisting of 38 characters. The Board have held frequent sittings this winter, with the sanguine hope of simplifying the English language, and especially its Orthography. After many fruitless attempts to render the common alphabet of the day subservient to their purpose, they found it expedient to invent an entirely new and original set of characters.

These characters are much more simple in their structure than the usual alphabetical characters; every superfluous mark supposable, is wholly excluded from them. The written and printed hand are substantially merged into one.

We may derive a hint of advantage to orthography by spelling the word eight, which in the new alphabet requires only two letters to spell it, viz. AT. There will be a great saving of time and paper by the use of the new characters; and but a very small part of the time and expense will be requisite in obtaining a knowledge of the language.[28]

This “sanguine” prognostication did not work out well, but not without effort on Phelps’s part. He prepared numerous items connected with the Deseret Alphabet: approximately seventy articles in the Deseret News (primarily scriptural quotations),[29] a display of the Deseret Alphabet with instructions on its use in the 1855 Deseret Almanac, two primers for children (Deseret First Book and Deseret Second Book), and a selection from the Book of Mormon (Book of Nephi).[30] Many men and women tried to make the Deseret Alphabet succeed, but numerous factors worked against it, primarily lack of sufficient funds and of interest from the people themselves. The church abandoned the alphabet in the 1870s.[31]

Legal Work

Phelps also participated in the valley’s early legal affairs as he had done in Nauvoo, where Joseph Smith had called him “Judge Phelps” and had sought legal advice from him. Phelps’s knowledge base proved beneficial in Deseret as well, and he maintained his “Judge” moniker. Church leaders appointed Phelps justice of the peace and charged him to become a licensed lawyer, which he became. One of his first cases took place on August 17, 1850, when he represented passengers in a wagon train of gold seekers, whose proprietors simply forsook their duties to lead the train to California as per contract after arriving in Salt Lake Valley. The case was resolved to the satisfaction of all parties.[32]

Once Utah was designated as a territory, it became necessary for all lawyers to be readmitted to the bar, to which Phelps was admitted on October 7, 1851.[33] Immediately he participated in a famous homicide case. Church agent Howard Egan had gone to California by assignment and, upon his return, learned that another man had seduced Egan’s first wife and fathered a child through her. Egan sought out the offender and killed him. When the case came to trial, Egan was represented by Phelps and George A. Smith, an apostle. Phelps and Smith argued that Blackstone’s “common law” principles did not apply in the Mountain West and that Egan was justified in slaying this man who had wickedly interfered with his marriage. Phelps also drew on the Bible and classical writers Homer and Virgil! The jury acquitted Egan.[34]

Upon Utah Territory’s inception, Phelps was named the official notary public for Great Salt Lake County. He maintained this position well into the 1860s. It allowed him to do paid legal work for clients and official government business.

Having served in the original general assembly of the State of Deseret, Phelps was elected from Great Salt Lake County to Utah Territory’s House of Representatives in its first legislative assembly. The legislature met for the first time on September 22, 1851. Phelps was selected as the first Speaker of the House. He continued in that capacity through March 1852 while also serving as a Utah Library commissioner. He was replaced as Speaker for the 1852–1853 legislative session by Jedediah M. Grant.[35] Perhaps church leaders were not pleased with Phelps’s role and wanted a priesthood authority in that position. Phelps would go on to serve in the House of Representative through 1860.

Junior Editor of the Deseret News

Phelps began editing the Deseret News and other documents when the newspaper started in June 1850. He served as junior editor to nominal editor Willard Richards, as he had similarly done at the Nauvoo printing office and for precisely the same reasons. President Joseph Smith desired that ecclesiastical leaders be seen as supervising the church-owned press; President Brigham Young continued this precedent with the Deseret News in the West. Thus Phelps supervised the daily editing and printing operations in Great Salt Lake City and wrote many news items and editorials. (In Utah Willard Richards was otherwise busily engaged as postmaster, Deseret Secretary of State, president of the Territorial Legislative Council, church historian, and second counselor in the First Presidency. On top of those responsibilities, he participated in numerous trips to outside settlements. Richards, who was overweight and had suffered a long time from painful bouts of palsy and dropsy, passed away on March 11, 1854.)[36]

Phelps and other trained printers supervised daily operations of the Salt Lake printing office. Thomas Bullock, a protégé of Richards, contributed a great deal to publishing the Deseret News. Phelps’s contributions were in the form of poetry and hymns; weather reports and suggestions for more productive farming; monthly data on sunrises, sunsets, and moon phases; the serialized “Life of Joseph Smith”; republished articles from exchange papers; reports on world events involving chaos and serious diseases, particularly “the cholera”; reports on Deseret events of which he was a part; presenting toasts at celebratory events; preaching gospel principles; and promoting the annual Deseret Almanac, which he prepared himself and printed on the Deseret News press.[37]

This chapter contains many samples of Phelps’s writing that illustrate his thoughts and ideas and indicate his significant role in early Deseret. One of his early Utah poems was “I Am Not Old,” which referred to plural wives more than a year before the church’s first official acknowledgement of its practice of polygamy in September 1852.

I am not old,—it can’t be so

At three score years and ten;

For what I see, and what I know,

Show beings be again.

I am not old,—nor will I be

When four score years are done;

For truth declares, eternity

Has only just begun.

I am not old,—nor can I hope

That death will trouble me;

For, like a sleep, I’ll soon wake up

In Paradise I’ll be.

I am not old,—like feeble flesh

That fear scares out of breath;

For life, with me, will bloom afresh,

Beyond the grave of death.

I am not old,—but on a term;—

Who cares where death has trod?

The Savior’s flesh fed not a worm:—

’Twas tomb’d, but rose a God!

I am not old,—and what of age?

The spirit is the leav’n;

I’ll set my part upon the state,

As I once did in heav’n

I am not old,—life pleases me;

You know I tell the truth;

What was it I came here to be,

BUT EVER-LASTING TRUTH!

I am not old,—but am and was

Like God, to have my wives,

And children, with celestial laws,

TO LIVE ETERNAL LIVES.[38]

Phelps ran a regular column in the Deseret News entitled “Valley Journal” in which he reported important daily events along with observations about the weather. A sample follows:

Sunday, 12 [January 1851]. Clear and warm weather, snow melting, while a large congregation assembled at the Bowery, for religious worship. At evening, the Seventies met in the State House to make arrangements for their conference on Saturday next.

Monday, 13. Frost last night, cloudy day. City council in session at the State House, 10 a.m.

Tuesday, 14. Some hail last night, and half in snow. General Assembly [of State of Deseret] in convention. Thawing and muddy, P.M.[39]

Repeating a practice that he employed in the Nauvoo newspapers, Phelps used a pseudonym to put forward his views in the Deseret News. This time he used “Homer,” a name he drew from his boyhood home in Homer, New York. On December 14, 1850, he wrote a letter to the editor, Willard Richards, with statements about church procedures. Phelps then responded to his own statements with his typical firm observations. For example:

Also, whether a Latter Day Saint would be counted in good standing and fellowship in the church, if he believes some principles, and disbelieves others. [No; Saints should be charitable and believe all things.—Ed.]

I think those who keep the commandments of God will be very likely to take the place and crown of those who deride them. [True. Ed.]

For my own part I do not want to see any of our brethren or sisters countermanding persons who will treat the principles of our holy religion or any of our people with disrespect for the gospel sake. [Neither do we, and a withering blight will brood over the spirits who do. Ed.][40]

Contextually, this was midwinter when many discouraged Mormons decided to leave Deseret and take off for warmer climes and enticing goldfields in California. In the next edition of the News, “Homer” again emphasized that members strictly follow directions of the fifteen presiding church authorities and be willing to sacrifice worldly pleasures because their eternal salvation was at stake. “When the Saints of God can feel the same interest in this work, as the Presidency or Twelve, and seek for the interest of the whole, then the work will roll on with such rapidity, that it will astonish the world and will give power and influence to this people that they have little conception of.”[41]

Phelps repeatedly wrote under his pseudonym to promote his ideas of building the kingdom of God.[42] “Homer” even wrote poetry. Continuing his grandfatherly counsel to Zion, Phelps penned:

The Saints of God should shun three things:

Slander, tattling, and hypocrisy;

They’re like the Upas Tree,[43] which brings

Death and accompanying misery.

Three others they’ll do well to own:

Truth, virtue, and integrity;

These, like the angels in their homes,

Bring joy, and peace, and harmony.[44]

At the July 24, 1851, celebration in Great Salt Lake City, a male trio sang “Homer’s” song “The Union,” in which Phelps sarcastically derided the so-called unity in America after the Compromise of 1850.[45]

Remarkable Toastmaster

Offering toasts on celebratory occasions was an honored tradition dating back to the ancient Greeks and Romans. Latter-day Saints also participated in toasting, especially on holidays. Phelps loved being the chief toastmaster for many years. Normally, toasts were accompanied by the raising of a glass of wine or some other beverage. Whether Mormon toasting included the raising of glasses and, if so, what beverage may have been involved is not known.

The 24th of July holiday included toasts at the public celebration in downtown Great Salt Lake City. Often more than a dozen toasts were offered. Phelps offered more than half of them. On the July 24 holiday in 1850, for example, Phelps toasted:

The Declaration of Independence, and the Constitution of the United States:—Our fathers fought and bled for them, and their children should live and die for them.

Joseph Smith the Prophet, & Hyrum Smith, the Patriarch:—Martyrd for the truth in a land of liberty, and yet the truth lives.

The State of Deseret:—The bees save honey, & the wise virgins keep oil in their lamps: so Deseretians, live by the golden rule.

The University of Deseret:—Who comes there? A friend with the Candle of the Lord.

Shine on brilliant light; guide the Mormon in his path

From the dark ancient banquet of Baal;

That ever, ever more, he may walk in the truth

Till, in glory, he comes to his own fathers’ house.

Our Feast of the 24th of July:—The first fruits of the Valley for the first-born of Israel; our Father honors them that honor Him.[46]

On July 4, 1851, Phelps led the way with additional interesting toasts:

“The President of the United States.” Good deeds make a great man at home and abroad.[47]

“The Several States.” United, they’re hailed as the chief—divided, disgrac’d as a thief.[48]

“The Public Domain.” Free land, free water, free air, and free men, give all an equal chance to live; amen.

“Agriculture and Manufactures.” When they bud in righteousness, the earth will be clothed in beauty.

“Learning.” Happy the people that get wisdom, for they shall find grace on earth, and glory in heaven.

“The Territory of Utah.” Rocky mountains, sandy plains; Truth and labor have their gains.

“The Ladies of Deseret.” Like early swarms, make full hives, And that’s the way the kingdom thrives.

“The Fourth of July.” We celebrate the fathers’ patriotism of ’76; but spurn their sons’ degeneracy of latter days.[49]

Deseret Almanac

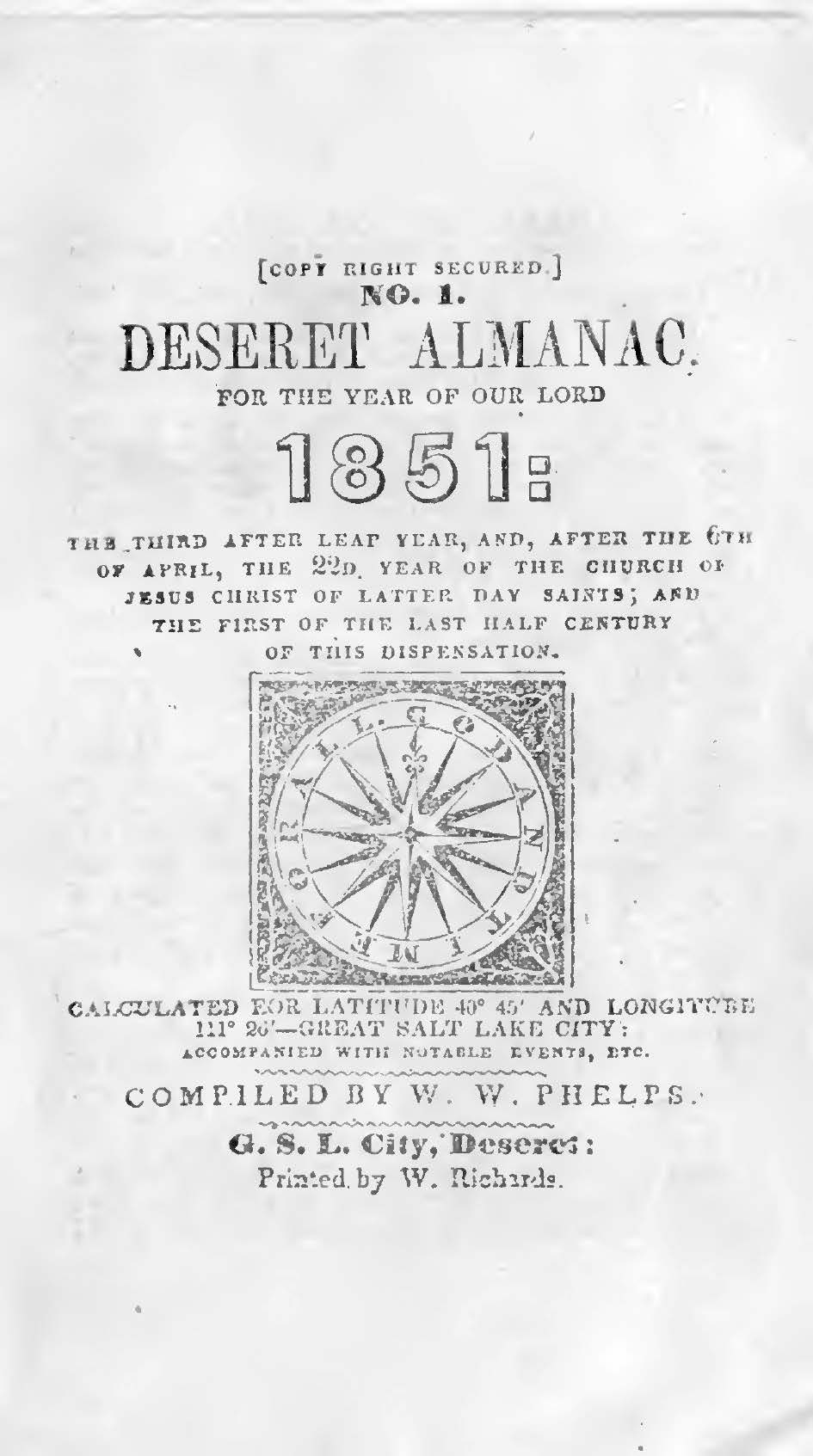

Phelps’s 1851 Deseret Almanac

Phelps’s 1851 Deseret Almanac

Phelps promoted himself through the Deseret News to advertise for his forthcoming Deseret Almanac, a publication that would become nearly an annual staple in Utah through 1865. Early in 1851 he advertised the following:

THE DESERET ALMANAC, for 1851, by W. W. Phelps, is in press, and will be ready for sale early next week. So far as we have had the opportunity of examining, we believe that our friend, Judge Phelps, has spared no exertion to get up an almanac that will be desirable, useful, and acceptable to the Saints of Deseret, in which many interesting items of history, including chronology, which ought to be impressed upon the minds of all our children at the earliest age, and ought to be known by all who have not been with the church during the past twenty years.[50]

Phelps’s almanacs were indeed a potpourri of useful information, and they provided the Phelps family with needed income. The first, the 1851 almanac, sixteen pages long, contained information for the year about eclipses, names of the planets, evening and morning stars, sunrises and sunsets for each day, recording of important church milestones on certain calendar dates and for each year of the Restoration, and a list of the First Presidency and the Twelve Apostles along with the dates of their birth. Phelps explicitly omitted astrological tables that were typical in other American almanacs, calling them “matters of ancient fancy.” He included numerous pithy words of his self-styled wisdom such as “The wisdom of the world is like dust, which falls on everything, and remains till it is washed off by a refreshing shower from heaven.” Phelps provided a theological poem of his own composition, “The Center of the Heavens,” in which he extolled the powers of God and the priesthood that are manifest in a “fountain of love” and “millions of worlds, and their people.”[51]

In his 1852 Deseret Almanac, Phelps introduced himself as “K. J.” (for “King’s Jester),”[52] a moniker he would use in future almanacs. Phelps considered his role as “King’s Jester” to be a calling he received from Joseph Smith. “My sixth office, As King’s Jester and Devil,” he wrote, “I have performed as well as I could for twenty years. Hope to do better when more spirit comes.”[53] Indeed, Phelps had performed the role of the serpent/

This second almanac became Phelps’s longest—forty-eight pages. In addition to typical astronomical, weather, calendrical, and agricultural information, it contained copious amounts of the King Jester’s theology and witticisms. K. J. authored six poems. In “Our Father in the Heavens,” Phelps reiterated Joseph Smith’s theology of multiple earths, Gods, and eternal increase:

When eternities began,

There were precepts made for man,

Knowing Lucifer deceives,—

For each Adam had his Eves.—

Like millions of millions his Father once had blest;—

Or millions of millions in everlasting rest.

Then our Father in his youth,

Came from Teman[54] full of truth,

Cloth’d in flesh like you and I,

Sav’d his world, and went on high,

Like millions, &c.

Morning Stars together sang,

Sweet the song on Kolob rang;

“There’s another Kingdom Come;

“There’s another God come home:”—

Like millions, &c.

O’ what glory fills each realm!

And what wisdom guides the helm!—

As a resurrected soul,

Every God controls a whole:—

Like millions, &c

What a mighty scope for thought,—

Where the spirits are begot?

Born for Kingdoms yet to be,

In a new eternity?

Like millions, &c.

There’s the mansions; there’s the means;

There’s the Kings, and there’s the Queens;

There’s the children; there’s the plan;

There’s the glory yet for man—

Like millions, &c.[55]

Phelps exaggerated his own experiences and importance in his poem “Home”:

I have traveled all over this fame spotted earth,

To pick up the crumbles of innocent mirth,

And gather the diamonds of wisdom and worth;

And lo! the best treasure,

The sincerest pleasure,

I found was at home.

I have been to the palace where kings sat in state,

Surrounded with nobles, the great with the great,

Where subjects were lingering to find out their fate:

And O! how they trembled!

And each one dissembled!—

There’s no place like home.

I have been to the cottage, when there sat the poor,

In want of the blessings that money procure;

Or were sick, for the doctor had fail’d them to cure;

And yet all their troubles,

Were transient as bubbles,

For they were at home.

I have been to the banquet, of feastings and glee,

Where beauty and fashion were tete-a-tetee,—

As if fortune and friendship were ever to be:

And mid all this showment,

Each heart took a moment,

To sigh for its home.

I have ask’d the old sailor, that sail’d on the sea,—

I have talk’d with the soldier that fought to be free,—

To tell, if they could, where contentment might be:—

Without an emotion,

Or separate notion

They said ’Tis at home!

I have dreamed of the Zion where God lives above,

Where perfection is basking in union and love

And spirits go down in the form of a dove:

So kindly to meet us;

And sweetly to greet us;—

Go there:—There is home.[56]

In his 1853 almanac, as was his annual wont at this point, Phelps penned proverblike statements within the pages dedicated to monthly calendars. Examples of these statements in 1853 include the following:

- Sectarianism: Truth and error married together for life only.

- Celestial bodies have one spirit. Evil bodies hold seven devils.

- Meekness conquers more than might.

- Flattery is the fog of greatness.

- Why does man fail at nine times out of ten? Because he does not honor God.

- God was married, or how could he beget his Son Jesus Christ lawfully, and do the works of the father?

- Bogus, a saint digging gold.

- Death and Satan are trappers.

- A tempest in a tea-pot, a grumbling saint.

- Doctors pick bones. Mormons hate drones.

- Light is as the great ocean of the Gods, for the commerce of the heavens, without attraction or gravitation.

- Gods are nurtured on earth.

- Days are pieces of time:—Do save the pieces.

- Sincerity is better than bank stock.

- Sincerity, Truth, Uprightness, and Virtue are exalting qualities.

- Make your own clothes and wear them.

- The King’s Jester makes the people drink the truth with sweetening.

- Be Zealous:—& not jealous.[57]

Preaching Practical Mormonism

Relentlessly, Phelps promoted Mormonism and its principles as he understood them. In so doing, he drew enthusiastically from the teachings of both Joseph Smith and Brigham Young. At a holiday celebration on July 24, 1851, Phelps delivered a resounding address to the people, part of which reads as follows:

Today we celebrate the victory of patience over passions; the dawn of light over darkness; the success of reason over madness; the reign of wisdom over folly; the prosperity of truth over error; the triumph of pure religion over strong persecution:—and, what shall I say? It is a day of exultation; the pastime of the Lord’s anointed; a holiday of bliss; for the achievement of this human happiness; this Mormon jubilee, was not won at the cannon’s mouth; fighting for the laurels of fame; neither was it won by storming a fortress, and butchering men, women, and children, to satisfy a sovereign that we were heroes: the bloody battlefield and the crimson flag, have not told the world that we cope with our foes by the purse or the sword: the honor of plundering nations, if that is honor, belongs to the Christians—not the Mormons—the trophies of war are the property of citizen soldiers—not the wealth of pioneer saints—No; we come not as the scientific world, with philosophy to-day, and devastation to-morrow; with a Bible in one hand, and a sword in the other; we come not as the hypocrites with long faces and long prayers to be seen and heard of men; but we come in the name of Israel’s God, as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; we come as the sons apparent of the sires of “76;” we come as the heirs of the kingdom holding the keys of the Priesthood, to minister salvation where there is an ear to hear, and a heart to receive; and we come as a part of the people of the republic of North America—to rejoice because the Lord has led us out of bondage, and placed us among the mountains in this goodly valley.

Four years ago to-day, President Young, with the faithful pioneers, came into this valley by inspiration. . . . The destiny of the church was hid in this unmissioned recess, like a pearl in the sea; but when a prayer ascended up to the Recorder of heaven, the spell burst; the angels shouted, and we—WE! not the God forsaken, but the world-hated Mormons, had a home prepared in the desert. Yes, a home prepared, a thousand miles from the confines of democracy or freedom on the east, and nearly a thousand miles from the suburbs of hell on the west. Yes! the valley of rest in the tops of the mountains, where as Isaiah wisely predicted:—“No galley with oars, neither gallant ship shall pass by.” Glory to God for his mercy and thanks to the pioneers for fortitude.

And what has been done in four years? Let the public works bear testimony; then look to the east and west, the north and the south, and behold the golden wheat fields smiling with abundance, and all this, too, where it rarely rains in summer. Success to irrigation and industry, what has been done can be, and what has not been done may be.

The valley teems with health and happiness, peace and joy, and like the star-spangled heavens after a storm, the Great Basin is sprinkled with the life-glowing habitations of heaven’s noblemen.[58]

Phelps also gave affectionate nicknames “as the spirit prompted [him]” to each member of the presidency and the Twelve, using those he had penned in Nauvoo and then adding additional ones to the apostles who had subsequently been called:

Presidency. Brigham Young, the Lion of the Lord. Heber C. Kimball, the Herald of Grace. Willard Richards, the Keeper of the Rolls.

The Twelve. Orson Hyde, the Olive-branch of Israel. Parley P. Pratt, the Archer of Paradise. Orson Pratt, the Gauge of Philosophy. Wilford Woodruff, the Banner of the Gospel. John Taylor, the Champion of Right. Geo. A. Smith, the Entablature of Truth. Amasa Lyman, the Aegis of Justice. Ezra T. Benson, the Helmet of Righteousness. Charles C. Rich, the Measuring Rule of Patience. Lorenzo Snow, the Mirror of Hope. Erastus Snow, the Evergreen Sprig of the Mountain. Franklin D. Richards, the Spy-glass of Faith.[59]

Phelps Family through 1854

In early Deseret, Phelps presided over two polygamous families. He and his ever-loyal first wife, Sally Waterman Phelps, had three children still residing in the household: Henry Enon (born 1828), James (born 1832), and Lydia (born 1835). William and Sally’s oldest son, Waterman, along with his wife, only temporarily stopped in Great Salt Lake City before moving on permanently to the California goldfields and out of the church. The three oldest daughters, two of them married to non-Mormons, remained with their families permanently in the Midwest. Henry became an aide to William and was gradually gaining respect on his own in Salt Lake.

William married plural wife Sarah Betsina Gleason in Winter Quarters in December 1847, and she went west with the Phelpses in 1848. Correspondence with Brigham Young in March 1849 shows that Sarah was displeased with her role—a “menial slave” in her words—in the Phelps family. Young counseled Phelps to be a better husband.[60] The marriage survived. In 1850 Sarah gave birth to Gleason Wines Phelps, but the little boy passed away in 1853. Ellen Cleary Phelps was born to Sarah in March 1853. Sarah remained Phelps’s wife and part of his household until he passed away in 1872.

Phelps added another plural wife, Mary Roberts Jones, on April 3, 1853. Mary was born in Wales on August 1, 1837, making her not yet sixteen when sealed to sixty-one-year-old Phelps. She and her parents had joined the church in their homeland, but her mother died at sea and her father passed away in St. Louis. Mary was orphaned and essentially unwanted as she crossed the plains in 1852. No details exist; perhaps church authorities recommended that Phelps take her into his household as a wife. But this union tragically ended quickly, when William desired to procreate with her, and she wanted no part of it.[61] They were divorced in October. Only months later, in February 1854, Mary married twenty-six-year-old James Record Dunster, another orphan. This pair remained stalwart church members.[62] Mary’s posterity came to look upon Phelps with disdain.[63]

Prospects for the Future

Despite his eccentricities, W. W. Phelps remained a highly esteemed citizen after five years following the founding of Deseret. He was one of the few adult contemporaries of the Prophet Joseph Smith remaining in Great Salt Lake City, other than the First Presidency and the Twelve Apostles. He was nine years older than Brigham Young and much older than most other apostles. Phelps’s knowledge of the early church, its revelations, and its organizational structures remained useful. His printing experience still paid enormous dividends at the printing office, especially with regard to the Deseret News since editor Willard Richards had become incapacitated. Phelps was an elder statesman in Utah, and even at age sixty-one, from all appearances he would serve effectively for many years to come. He fully expected to live up through the millennial day.

Notes

[1] A few diarists or autobiographers kept a record of the journey. Some mentioned Phelps and his family. Richard Ballantyne wrote on July 7, 1848: “W[illiam]. W[ines]. Phelp’s wife crowded Brigham Youngs Carriage or rather drove her Team in ahead of his Carriage while he was going to cross a creek. Prest. Young said in the meeting if Judge Phelps would not teach his wife better manners he would kick his arse out of the Company.” Journal of Richard Ballantyne, July 7, 1848, https://

[2] JH, July 2, 1848; July 9, 1848; “Historian’s Office General Church Minutes,” July 9, 1848, CR 100 318, CHL.

[3] JH, July 9, 1848, taken from Thomas Bullock’s journal; John D. Lee reported also of this composition and singing in A Mormon Chronicle: The Diaries of John D. Lee, 1848–1876, ed. Robert Glass Cleland and Juanita Brooks (1955), 1:30–79,

https://

[4] Journal of Thomas Bullock, June 26, 1848, https://

[5] Heber Q. Hale, Bishop Jonathan H. Hale of Nauvoo: His Life and Ministry (Salt Lake City: printed by the author, 1938), 178.

[6] W. W. Phelps, meteorological journal, 1847–1849, Brigham Young office files, CR 1234/

[7] JSP, CFM:xliv.

[8] “Constitution of the State of Deseret, with the journal of the convention which formed it, and the proceedings of the legislature consequent thereon,” 342.792 D451c 1850, CHL. See also Dale Morgan, “State of Deseret,” Utah Historical Quarterly 8, no. 2 (1940): 82.

[9] JH, March 4, 1849; Kate P. Carter, comp., “Exploration in the Rocky Mountain West,” lesson prepared for Daughters of Utah Pioneers, Central Company, February 1951, 223.

[10] JH, April 5, 1849. Phelps referred to his supervision of canal digging and surveying in a letter to Brigham Young dated March 20, 1849. CR 1234/

[11] “The Constitution of the New State of Deseret,” 342.792 D451ca vol. 3, nos. 1–2, 1849, CHL. A printed rendition of the constitution was published in Great Salt Lake City in 1850 after Phelps’s Ramage press arrived in the valley. This publication also contained some of the early laws passed by the general assembly, including the formation of the “University of the State of Deseret,” of which Phelps was a founding regent, and the creation of the surveyor general’s office, first held by Phelps. “Constitution of the New State of Deseret,” 342.792 D451c 1850, CHL. A petition for the creation of this university is found in “To the General Assembly of the State of Deseret,” M261 T627 1850, CHL.

[12] “Rules and regulations for the governing of both houses of the General Assembly of the State of Deseret, . . . December 2, 1850,” 328.7925 D451r 1850, CHL; Morgan, “State of Deseret,” 89.

[13] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, January 20, 1862, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[14] Andrew Jenson, Church Chronology: A Record of Important Events Pertaining to the History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2nd rev. ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1914), 37.

[15] Richard Francaviglia, The Mapmakers of New Zion: A Cartographic History of Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2015), 88, 90–91. Page 91 contains a reproduction of Phelps’s map/

[16] The exploring expedition is discussed in William B. Smart and Donna T. Smart, “The 1849 Southern Exploration Expedition of Parley P. Pratt,” Nauvoo Journal 11, no. 1 (Spring 1999): 125–37 (quotation from p. 126).

[17] Smart and Smart, “1849 Southern Exploration Expedition of Parley P. Pratt,” 125–37; Southern Exploring Expedition papers, 1849–1850, MS 2334, CHL. From the small Salt Lake Valley settlement of Cottonwood, Phelps wrote a letter to Brigham Young on November 24, 1849, in which he outlined the immediate plans of the expedition that was to leave that very day. Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[18] Smart and Smart, “1849 Southern Exploration Expedition of Parley P. Pratt,” 125–37.

[19] Smart and Smart, “1849 Southern Exploration Expedition of Parley P. Pratt,” 129.

[20] Willard Richards, address to the Chancellor and Regents of the University of the State of Deseret, April 17, 1850, https://

[21] Phelps spoke at the dedication of this schoolhouse on the value of learning and the evil of too much frivolity. “Fourteenth Ward,” Deseret News 1, no. 24 (January 11, 1851): 188.

[22] Messages of the First Presidency, comp. James R. Clark (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965), 2:69; Kate B. Carter, ed., “Pioneer Schools and Schoolmasters: The University of Deseret,” Heart Throbs of the West (Salt Lake City: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, 1940), 2:114–16; “Parent School,” Deseret News 1 (November 16, 1850): 158 (this same article ran in the next three issues of the Deseret News); “Parent School,” Deseret News 1 (February 22, 1851): 212.

[23] “May Day,” Deseret News 1 (May 17, 1851): 261–62.

[24] “Parent School,” Deseret News 1 (May 17, 1851): 260.

[25] A notice to potential “scholars” who would become teachers was first posted as “Parent School,” Deseret News 1 (February 8, 1851): 206. It was signed by Orson Spencer, Chancellor, and W. W. Phelps, Regent. This notice was reprinted for several weeks. A report of the third term for the parent school appeared in “Parent School,” Deseret News 2 (December 13, 1851): 11. Spencer and Phelps then continued to advertise for the school in the newspaper.

[26] “The Celebration of the Twenty-fourth of July,” Deseret News 1 (July 26, 1851): 298.

[27] Neil Alexander Walker, A Complete Guide to Reading and Writing the Deseret Alphabet (self-published, 2005); Kenneth R. Beesley, “The Deseret Alphabet in Unicode” (paper delivered at the 22nd International Unicode Conference, San Jose, CA, August 14, 2002).

[28] “The New Alphabet,” Deseret News 4 (January 19, 1854): 10; emphasis in original.

[29] For example, “Deseret Alphabet,” Deseret News 8, no. 50 (February 16, 1859): 213.

[30] Phelps actually asked Brigham Young if he could publish books in the Deseret Alphabet. W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, September 17, 1855, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[31] Peter Crawley, ed., A Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1997), 3:136–40.

[32] Brooks, On the Mormon Frontier, 2:378.

[33] Brooks, On the Mormon Frontier, 2:406–7. Hosea Stout was much more active as a lawyer than was Phelps. In his diary, Stout went into detail about his participation in court cases. Occasionally he made brief mention of Phelps’s activities with the law. See Brooks, On the Mormon Frontier, 2:375, 431–33, 551, 627.

[34] Deseret News 2 (November 15, 1851): 3; Kenneth L. Cannon, “Mountain Common Law: The Extra-Legal Punishment of Seducers in Early Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 51 (Fall 1983): 308–27; Brooks, On the Mormon Frontier, 2:407, 407n76.

[35] “Legislative Assembly Rosters: 1851–1894,” compiled by Utah State Archives staff, 2007, http://

[36] Orson Spencer, “Death of Our Beloved Brother Willard Richards,” Deseret News 4 (March 16, 1854): 34.

[37] In his almanac, Phelps often used the pointing-finger dingbat that he had used so frequently in past newspapers to highlight certain subjects.

[38] “I Am Not Old,” Deseret News 1 (April 8, 1851): 233; emphasis added. Phelps noted March 29, 1851, as the date for the poem’s creation. On July 15, 1852, renowned New York Herald editor James Gordon Bennett published a letter from Phelps that also spoke openly of Mormon plural marriage.

[39] “Valley Journal,” Deseret News 1 (January 25, 1851): 197.

[40] Homer, “For the News, Mr. Editor,” Deseret News 1 (December 14, 1850): 169.

[41] Homer, “For the News, Mr. Editor,” Deseret News 1 (December 28, 1850): 180–81.

[42] Other dogmatic letters to the editor in Phelps’s style from “Homer” appeared in Deseret News 1 (January 25, 1851): 195–96; (February 8, 1851): 203–4; (February 22, 1851): 211; (March 8, 1851): 220; and (April 19, 1851): 243.

[43] The upas tree, which grows in parts of Africa and Asia, contains extremely toxic sap used for poisonous arrows.

[44] Homer, “For the News,” Deseret News 1 (May 17, 1851): 257.

[45] Homer, “The North and South Do Agree,” Deseret News 1 (August 19, 1851): 306–7.

[46] “News,” Deseret News 1 (August 10, 1850): 66; emphasis in original. Phelps offered fourteen total toasts on this occasion.

[47] President Millard Fillmore was appreciated by Mormons because he had appointed Brigham Young as governor of Utah Territory.

[48] This was a period of steep divides between the northern states and the southern states over issues of states’ rights and slavery.

[49] “The Celebration of the Fourth of July,” Deseret News 1 (August 12, 1851): 292. Phelps offered sixteen total toasts on this occasion.

[50] “The Deseret Almanac,” Deseret News 1 (January 25, 1851): 197. For a comprehensive discussion of almanacs in America and of Phelps’s almanacs in particular, see David J. Whittaker, “Almanacs in the New England Heritage of Mormonism,” BYU Studies 29, no. 4 (Fall 1989): 89–113.

[51] This almanac bore the lengthy title Deseret almanac, for the year of our Lord 1851: the third after leap year, and, after the 6th of April, the 22d year of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints; and the first of the last half century of this dispensation [.. .], M288 P541d 1851b, CHL. Each annual Deseret Almanac has been digitally reproduced and made available online by the CHL. Phelps’s comment on astrology is on p. 2, his proverb on p. 14, and his poem on p. 3.

[52] On the title page of the 1852 Deseret Almanac appears “By W. W. Phelps, K. J.” (with the abbreviation explained as “King’s Jester” on p. 3). Thereafter, Phelps often used “K. J.” or “King’s Jester” to identify his poetry and other statements.

[53] William W. Phelps to Brigham Young (both in Great Salt Lake City), October 12, 1863, Brigham Young office files, CR 1234 1, CHL. This letter is now digitalized and is available at the CHL website.

[54] Teman was the name of an Edomite clan and an Edomite city. This idea that “God came from Teman” originated in Habakkuk 3:3 and refers to God appearing out of the east, or in other words, shining his light on his children like the sun.

[55] K. J., “Our Father in the Heavens,” Deseret Almanac (1852), 8, 10. Phelps’s ideas influenced Brigham Young, who at this same time was developing and expressing his own cosmological ideas. See C. Chase Kirkham, “‘Tempered for Glory’: Brigham Young’s Cosmological Theodicy,” Journal of Mormon History 42, no. 1 (January 2016): 128–65, especially 160–61.

[56] K. J., “Home,” Deseret Almanac (1852), 22.

[57] Deseret Almanac (1853), 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23; emphasis in original.

[58] “W. W. Phelps’ Speech,” Deseret News 1 (July 26, 1851): 297–98. The handwritten copy of this speech, in Phelps’s hand, is found in Deseret News editor’s files, 1850–1854, vol. 1, nos. 38–39, July 24, 1851, CHL.

[59] W. W. Phelps, “Appellations,” Deseret News 1 (March 8, 1851): 221.

[60] Sarah B. G. Phelps to Brigham Young, March 6, 1849; W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, March 18, 1849; Sarah B. G. Phelps to Brigham Young, March 20, 1849; Brigham Young to W. W. Phelps, March 30, 1849, box 66, folder 19, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[61] A newspaper in Honolulu, Hawaii, picked up some information about this union between Phelps and Jones, reporting that Phelps persuaded Jones that she “could not be saved unless she was ‘sealed’ to him. She, not understanding exactly what was expected from ‘sealed’ ones, consented; but when night came on and he wanted to share her couch, she exclaimed: ‘Is this what you are after, you old covey? I’ll seal you,’ and thereupon struck him in the face with her fist, giving him a black eye which he carried for several days. Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands), September 24, 1857, 4.

[62] This information is available at www.myheritage.com.

[63] Many years ago, I received a phone call from a descendant of Mary Roberts Jones, who told me of their attitude toward Phelps. I failed to document the specifics of the call.