Frontiers Coming Together

Donald G. Godfrey, "Frontiers Coming Together," in In Their Footsteps: Mormon Pioneers of Faith (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 191–250.

Bridging decades of frontiers can appear as rapid transitions if people simply look back. In reality, those bridges come one day at a time, with significant physical labor, trials, and a hope for the future. Pioneer life revolved around the essentials of shelter, food, and clothing. It was an agrarian farm and ranch lifestyle, at the start, often isolated from the big city and national business centers. Homes were constructed with the available local materials surrounding the farm. This is why Charles Ora Card, as he explored British Columbia and Alberta, was always alert for land with timber and water resources. As settlers moved into the West, they organized local communities, churches, schools, and governments. People worked together, particularly in small villages. Working together meant clearing the land, building homes, and practicing a cooperative enterprise. A quilting bee brought women of the neighborhoods together to sew quilts. Similarly, barns were raised, and crops were planted, harvested, and preserved.

It was the Union Pacific Railroad and the Canadian Pacific Railroad that brought the East to the West in both nations. It happened just before Card’s exploration. Distances once traversed slowly by horse, covered wagon, and foot were now covered comparatively quickly. The first Mormon settlers into southern Alberta came in wagons and later by the rails. The trains of Alberta linked the US and Canadian railways.[1] By 1899, the first pioneers were arriving at Stirling, Alberta, on the Alberta Railway and Coal Company (AR&CC) trains. By 1900 the St. Mary’s River Railway Company (SMRRC) connected Stirling with Magrath and Spring Coolee. Between 1902 and 1905, the lines were extended to Cardston, Raley, Woolford, and Kimball, Alberta.[2] All interlinked to the rail centers in Lethbridge and Calgary. These lines moved people and freight in unprecedented numbers.

At the turn of the century, other modes of transportation and communication were evolving. The steam-driven automobiles were first called the horseless carriage. The first US patent for the gasoline engine was actually filed in 1885. The Stanley Steamer was in production in 1896. By 1899, there were eighty-four automobile manufacturers in the United States, all of which were in the New England states. In Canada, the first automobile plant was near Windsor, Ontario, in 1904. The steam engines burned kerosene, also used in home oil lamps. The burner heated the water, creating steam pressure to push the crankshaft driving the engine. The electric cars were quieter, but the batteries were too heavy, and the drivers had to stop often and recharge. The gasoline-powered engine would take over the market simply because an abundance of oil had just been discovered in Texas and Alberta. By the 1920 automobiles were becoming the primary means of transportation.[3] Distances were closing. Along with automobile travel, the Industrial Age ushered in mechanical farm machinery and a host of new technology, including film and radio.[4]

At the same time transportation was growing and countries were expanding, territorial issues of imperialism ideology were debated. Card was not the only individual who saw missionary opportunities among the First Nations peoples. Josiah Strong, an American Protestant clergyman, argued that it was the mission of America to “carry the blessing of spiritual Christianity, to the backward areas if the earth.”[5] Missionaries of all faiths were reaching out around the globe to convert and educate native peoples to the new ways of Christianity. It was a national debate, and the approach was not always gentle.[6]

At almost the beginning of the twentieth century, illness, war, frivolity, and depression seemed to come in rapid progression: World War I, the 1918–20 Spanish Flu, the Roaring Twenties, and Great Depression of the 1930s. World War I broke out in 1914, and the armistice was signed 11 November 1918. Children in elementary schools were taught the exercises of war, and boys were taught how to handle a rifle. It was 1917 when the United States ultimately declared war on Germany. “It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war,” Woodrow Wilson declared. He was thinking of a time when “a concert of free people” could eliminate the necessity of war.[7] The end of WWI was followed by a flu epidemic that killed millions. The flu touched every community and almost every household in North America and the globe.[8] The Roaring Twenties followed, with the Charleston on the dance floor. It was a short decade of social revolution, economic prosperity, cultural development, new freedoms, and a revolution in morals and manners. Darwin’s Origin of the Species introduced the idea of evolution into the religious debates. Freud brought forward the open discussions of sex. It was a comparatively footloose and free decade of history. It ended abruptly on 29 October 1929, often referred to as Black Tuesday. The stock market suddenly crashed, and the Great Depression would last more than a decade.[9]

Families on the Frontiers

The histories of the western frontier and the modern West were bridged by families. During frontier times, the Cards led the Mormon migration into Canada (see chapter 5). Charles Ora Card established “Card’s town,” along with multiple LDS settlements throughout southern Alberta. He organized, directed, and worked to construct the irrigation systems that opened a new land for farming and ranching. He promoted the Canadian Mormon immigration through the Deseret News, calling for “200 Men With Teams Wanted, who will become actual settlers in southern Alberta, Canada.”[10] It offered Latter-day Saints “a grand opportunity to accumulate means to pay for [homes and farms] without incurring the bondage of debt.” Twelve years after the first LDS settlers arrived, the town had “a newspaper, a cheese factory, a gristmill, two blacksmith shops, two carpenter shops, one tin shop, a shoe shop and a meat market. Taxes? We have none except those we impose on ourselves.”[11] Card’s town was incorporated 29 December 1898 and became Cardston. In 190, the Alberta Railway and Irrigation Company connected Cardston with Lethbridge, the major city of the area. The settlements of Magrath, Raymond, Mountain View, and others were just beginning to dot the district.[12]

A decade after the establishment of Cardston, the Godfreys, who had been living in Star Valley, Wyoming, packed their horses, carriages, and belongings into a train car and headed for Stirling, Alberta. Their destination was Magrath, twenty miles west of Stirling and east of Cardston. They arrived in Stirling in the middle of a late spring blizzard. They were venturing into the new land, following the first pioneers, all of whom labored with a vision of hope and opportunity. When their train arrived at the Stirling Station, the snow was so deep the horses could not even walk through the wind-packed drifts to Magrath. The train track had not yet reached Magrath, so each step was a forward lunge. This made progress excruciatingly slow and created significant stress on horses and riders. Riders felt like they were sitting atop a bucking bronco in a freezing winter rodeo, but there were no spectators or cheering crowds.

The family struggled reestablishing themselves. Melvin settled into a routine of working a handful of construction jobs, all the time looking for permanent work. He served as a carpenter, as town marshal, as a judge, and later as the owner of several small businesses. He would become heavily involved in public projects, working with Levi Harker and others, creating the framework for success in agriculture, electricity, roads, churches, schools, local businesses, and town government. The town boasted a growing complement of Main Street enterprises and by 1906 offered a post office and general store, the Magrath Trading Company, Christensen’s Blacksmith Shop, and the Tanner Lumber Yard to serve the continual flow of settlers still arriving from Utah.[13] Magrath would eventually be on the railway line between Cardston and Lethbridge. Available land, successful farms, irrigation, and transportation encouraged newcomers. Magrath farmers were shipping fifteen to twenty tons of sugar beets per acre to the Raymond Sugar Factory, twelve miles east.

Charles Ora Card had broken the first ground for planting in southern Alberta. He even had a handy grocery store in his Cardston log-cabin home. His son George followed his father’s entrepreneurial footsteps, working on the vital irrigation canals—earning both salary and land in Magrath for his labors. Settlers were coming, going, and growing with an abundance of available opportunities. Religious freedom, land, and employment opportunities were catalysts for growth. But it took hard work and ingenuity of the pioneering kind to succeed.

The Godfrey and Card families were poor, but like most pioneers they were determined. They were adventurous agrarians and were bold in new business undertakings. There was little difference between the “haves” and “have nots.” Most had very little of anything, but they were a bit daring and certainly industrious.

Melvin Godfrey arrived at the turn of the century. He eventually became the town marshal and constructed a three-unit business building. Gust’s Grocery was in the third unit, and Melvin owned and operated the store. He rented space for Long Jim’s Chinese Restaurant. The third unit was rented to a barber and periodically a dentist. It was the Godfrey children’s job to work the grocery store, and the youngest, Douglas, was in charge of keeping the new sidewalk clear of snow.[14] Melvin introduced the first silent movies to Magrath when he purchased the Electric Theater and Skating Rink. His Empress Theater took viewers from the silent screen into the age of sound and color. All the early settlers supported growing families taking advantage of every opportunity to prosper in peace.

Childhood on the Frontier

Magrath was a western frontier town. Cattle ranges were wide open, barbed wire fences only just beginning to appear. The McIntyre Ranch was the largest in the region. It was just south of Magrath and north of the US border. Each fall and spring they shipped and received hundreds of cattle from the Magrath train station. The station was at the north end of Main Street. Herds were driven from the ranch right through the town center by real cowboys, much to the excitement of the youthful wannabe cowboys who lined the dirt road, cheering the parade. Youngsters ran alongside the galloping cattle, at times grabbing the tails of the calves and hanging on for dear life. Laughter rang out as they were pulled along and splatted with fresh, wet cow dung, before falling into the irrigation ditch to clean off their bib overalls. Local branding and dehorning of the cattle kept the boys entertained almost as much as the cattle drives or watching the local blacksmith.[15] Every household had a barn and large gardens, so there was always plenty of work to do.

Melvin and Eva Godfrey’s children were Bert, Parley, Lottie, Floyd, Mervin, Joseph, Norris, and Douglas. Parley and Norris both passed away as children, leaving six in the growing family. Lottie was the only sister. The children were robust, playful, fun loving, full of themselves, and pranksters. They were outgoing, and, being a little rough around the edges, they liked a good boxing match. They could be mischievous, but they were easily loved. Bert and Floyd were perhaps a little shyer and more conservative than their younger brothers, Mervin and Joseph Douglas bore the brunt of friendly teasing. Harassing the littlest was a favorite pastime of the elder brothers. Joe and Mervin once convinced their kid brother that “Watkins Salve” would remove his freckles. The salve was an ointment used to soften a cow’s chapped nipples before daily milking, with no effect on freckles.[16] Playing on the hay ropes hanging in his father’s barn, Floyd once fell and bit a hole right through his tongue. He later liked to pull out his tongue with his thumb and forefingers, grossing out his children and grandchildren as the story grew with each telling.[17]

One of the Godfrey boys’ favorite pranks happened at the Magrath Agricultural Fairs when they were ribbon winners. Everyone brought his or her best chickens, horses, cows, homemade pies, and alfalfa to be judged. Floyd and his brothers were winners for their alfalfa crop entries. The local farmers never figured out how Melvin Godfrey’s town boys were raising such good alfalfa. It was full and sometimes five feet tall. What the farmers didn’t know was that, although Melvin’s sons had no alfalfa field, they had an irrigation ditch where wild alfalfa flourished. Floyd and his brother would gather a large bundle, cut and tie it together with one of their mother’s sewing ribbons, and take it to the fair. They won first prize every year.[18]

Melvin and Eva Godfrey’s second home. Courtesy of Godfrey Family Organization.

Melvin and Eva Godfrey’s second home. Courtesy of Godfrey Family Organization.

The irrigation ditches that wove throughout the town were a popular place for children to play. The water flowed toward the east and the north, with larger lateral ditches feeding smaller yards. These water funnels fed gardens throughout the town and neighboring farms, and they were summer swimming holes and bathing troughs for the young at heart. If a serious farmer diverted water to his field and bypassed the children’s favorite swimming spots, it was not beyond the rabbles to redirect the fun back where they wanted it. The farmer patrolled the length of the dig ditch, checking to see that no one used the water out of turn. When the farmer rode by, the boys hid in the barn until he had passed. Then the mischievous children ran to the head gates and switched gates so water would flow down the ditch where they played. Later, they’d run back to the barns and watch for the farmer to return, fuming and scolding as he closed the gates again. It was a game played between the working granger and the neighborhood children. Although no fun for the farmer, it would become a tale told often by the ruffians.[19] Such was the life of rambunctious frontier children.

Humble, Humble Homes

Melvin and Eva’s Magrath homes were modest. The very first, where Floyd was born, was a lean-to dugout built into the south banks of Pothole Creek near the north end of the Magrath Cemetery. These structures were temporary homes used often by the pioneers. They were sometimes called pit houses or mud huts.[20] They were just shelters for families and often their animals. Melvin simply excavated the ground from the side of the hill facing the creek and built a lean-to cutting into the bank. The sides of the structure were wood, and the roof was loose lumber covered with sod. This was how many western pioneers started what they called home.

Godfrey’s second Magrath home was one house north of the Cards on 2nd Street. Melvin dismantled the old lean-to and with a team of horses dragged the lumber up to the meadow and used it to build his second home. This more than doubled their living space. There were originally two rooms, but more were added as Mervin, Joseph, Norris, and Douglas came into the family. The walls and roof were wood framed. The outside wall was covered with chicken wire, stuccoed with mud, then painted. There were two small enclosed entries on the south and east sides. Dirty gum boots and overshoes were stored here in these entryways, with parkas hung against the wall.

Wooden shingles covered the roof. They were soaked in thick red lead paint and nailed to the double-pitched roof. The roof was held in position by skeleton-like walls erected from the foundation. There was no insulation in the walls. In the winter, ice built up inside the room on the northwest corner of the house, just below the children’s bed, due to poor air circulation. The structure itself was the only protection against the elements. Water in the tea kettle on the old coal stove froze at night. Winters were stinging cold.[21]

Outside and just west of the house was the all-important coal and wood shed. These 8 x 10–foot structures kept the coal and wood dry and usable in the winter, and they were close enough to haul a heavy bucket in the cold. The fire was stoked early each morning with the wood over any burning embers from overnight. Once a good fire was burning steady, mother cooked breakfast as the children gathered around the stove to get warm. In the summer, the woodshed was a secret retreat—a place to play out childhood dreams and cool down from the summer sun.

The outhouse was the coldest place in the winter world. “You didn’t stay long out there.”[22] The Godfrey’s outhouse was a “two holer,” a little bigger than usual.[23]

A water well was dug outside and away from the outhouse. It provided the water for cooking, drinking, and bathing. It was hauled indoors by the bucket full. The well was more than a fresh water source. It served as a summer refrigerator, a place for keeping butter and meat. Perishable foods were packed in a sack and lowered down the well on a rope close to the cold water. Eventually, Melvin installed a water pump in the kitchen, replacing the outside well. Running water in the house was a luxury, even though it still required being drawn up by hand with a pump. An ice box would eventually replace the well to keep things cool. This was indoor progress in small doses.

A root cellar was dug between the house and the barn. It was a hole about six feet deep, six feet wide, and twelve feet long with a door at one end. An A-frame roof covered the hole, and soil was spread over it for insulation. Inside, vegetable bins were dug deeper into the earth. These bins were for food storage. Shelves jutted from the dirt walls. The harvest from the gardens yielded potatoes, carrots, beets, parsnips, and turnips, hence the name root cellar. The bins were covered with a layer of dirt, and square lids were placed over the holes. This was sufficient insulation against the winter freeze and offered access when a child was sent for food.

A root cellar was not without its unexpected dangers. When Floyd was a young boy, his mother went into the cellar, filled her bucket, and was returning when she spotted a rattlesnake under the first step up to the door. She put down her bucket and made a run for it, jumping over the reptile onto the steps. The snake was hibernating, but she hurried inside, leaving Melvin to take care of the snake.[24]

After Floyd and Clarice were married and took over the old Godfrey home, young Kenneth went missing one summer day. Parents and grandparents engaged in a prayerful search. After a time, Clarice’s father thought, “Look in the root cellar.” There was Ken. He’d been playing in the yard, gone into the cellar for a carrot, and fallen asleep on the cool soil atop the vegetable bin.

The barn was farther back from the root cellar and woodshed. Their barn housed the family’s milk cow, pigs, chickens, and horses, which they used for transportation. A buggy shed on the south side of the barn was just a large lean-to structure. It faced east. It was large enough for two or three wagons, but Melvin owned just one buggy. It had the luxury of a cover that made it a more expensive model, $87.50 ($1,957). Around 1914, after he purchased his first Model T Ford, the shed was converted into a garage.[25]

Melvin was proud of his car. His first had headlights, a taillight, and two wide lamps operated with coal oil on each side of the windshield. There was a running board along the sides, allowing passengers to step up into the vehicle. On the driver’s side, there was a toolbox with pliers, a screwdriver, a tire-patching kit, a jack, and tire tools. The gas tank and spare tire were mounted on back. The front radiator was gleaming polished brass, and a hand crank in front got the engine fired, often more difficult to use than perceived. Many a broken bone was created when the cold engine backfired, spinning the crank back and smacking the driver’s arm. The car’s canopy was heavy leather; the windows were isinglass that flapped in Alberta’s west winds.[26] The morning after buying the car, Melvin showed it off to the family. He cranked it up and the engine started with a bang. The family all jumped in. Melvin released the brake, stepped on the gas, and “went right through the back of the buggy shed.”[27] A second version of this tale has Floyd’s brother Bert coming home late from a dance, and he drove the car through the back of the shed, “pushing the wall into the air.” Both stories were memorable family firsts. While he was a policeman, Melvin even tried his hand as a car salesman, but being an officer and running the Empress Theater took his time. Car sales proved one job too many.

The family garden filled the largest section of the yard, perhaps a half acre. Every spring their horse, “Old Baldy,” was hooked to the plow to prepare and plant the garden. The Alberta growing season was short—June through September, if the weather cooperated. Golden Bantam sweet corn, head lettuce, potatoes, peas, carrots, and all kinds of vegetables ripened in the summer sun. Old Baldy plowed the garden for Melvin, but the kids thought the horse was for their entertainment. After working all day, Old Baldy did not always agree. He was smarter than the boys who wanted to ride him and act like cowboys. If they approached with a bridle, even when it was held behind their backs, he could see it. He turned and ran, playing his own game of “catch me if you can.” Melvin taught his boys a better way to bridle Old Baldy. First, put some oats in the feed boxes. This attracted their horse, and the bridling became easy. They would say, “Old Baldy trained everyone well.”[28]

Childhood in Magrath

The childhood house for Floyd was Melvin and Eva’s second home at 155 1st Street West. Only Mervin, Joseph, and Douglas spent any time in the new brick home constructed later on Main Street. Floyd was close to his brothers, but around others he felt insecure and somewhat shy. He saw himself as “An Unkempt Lad.”[29] His bib overalls, which he did not like, were worn. He went barefoot for play and wore gum boots for work, and his shoes were half-soled with slick rubber his father cut to shape from an old piece of boot or a tire. He was embarrassed to wear his short knee pants because they were baggy. When he stood straight, his more formal bloomers looked like a “girl’s skirt.” After much pleading, his mother bought him long pants and a suit. He proudly headed to church in his new outfit, when a neighbor saw him cutting through the yard and teasingly commented, “Well look at the little girl.” Floyd ran home crying. His mother hugged him, “telling [him] not to pay attention” to that old man but to just go to Sunday School. However, Floyd never wore the suit again. Years later there were rumors that this man’s cow kept ending up in the town corral on the weekends. The boys always pleaded their innocence.

The Godfrey boys played with the other neighborhood kids, the Andersons, Jensens, Colemans, Schaffers, Merkleys, Cards, and Fletchers.[30] The Fletchers’ home, immediately south of the Godfreys’, became the Cards’ new place when George and Rose moved their family into town. In the Fletchers’ attic one day, after parents warned them they were “not to go up there,” Lottie lost an expensive watch while playing “dress-up” and posing behind empty picture frames. Her younger brother Floyd, their friends Howard and Gail Fletcher, and Lottie all went outside and knelt down around a bush. They prayed, “and when we got up there was the watch in the bush.” It was the beginning of their faith in prayer.[31] As the only girl in the family, “Lottie was spoiled,” her brothers and sisters said, which she denied, but “they were good to [her] sometimes taking the blame for what [she] had done.”[32]

There were friendly and not-so-friendly boxing matches in the house to settle childhood disagreements. Floyd seemed to be on the losing end of the matches, so his father bought two pairs of boxing gloves and taught Floyd some moves. At the next bout, the boys put on the gloves and went at it, but Floyd landed a few blows with his newly acquired skills, and the disagreements ended.

The Godfrey family may never have had much, but their needs were always met as family and community worked together. Harvesting ice in the winter was one such collaborative effort. There was no refrigeration, but there was a deep, muddy slough along the creek, south of the Card and Godfrey homes. It was the place where the community cut ice for preserving summer vegetables in their root cellars and ice boxes. The blocks of ice were perhaps eighteen inches square and three or four feet long, cut straight out of the creek, winched up to the ground with a team of horses, and hauled home. The ice blocks were placed in the cellars and covered with sawdust to prolong their shelf life. When needed, pieces were sawed for the ice box in the house.

One winter day, wearing his father’s awkward-fitting gum boots, Floyd went down to the creek to watch the workers cut the ice. It was slippery and wet. The adults tried to shoo children away from the icy creek, but as Floyd stood to move, his boots slipped out from under him and he skidded into the water. One of the workers, Alva Merkley, grabbed him at the back by his overcoat. He pulled him out of the creek, took off his boots, drained the icy water and gave him “a kick in the pants” to encourage him to leave. Floyd really didn’t need a lot of encouragement. He was freezing as he ran up the hill and back home.[33]

In the summer, the creek provided a place to swim. Pothole Creek was filled with adventure. It was a boy’s wilderness paradise. At first, Floyd just wandered down to the canal and watched the older boys. He was timid. Bravery came slowly and with experience. He started to swim with his clothes on. He learned a lot faster when one of the older boys, Red Stoddard, picked him up and threw him off the bridge into the middle of the swimming hole. Floyd “dog-paddled” to shore and afterward took a liking to the sport. He eventually had his own circle of swimming buddies and a secret swimming spot called “the old whirlpool.” It was not a well-kept secret. After school, in the warmth of spring, even with the water still cold, it was a popular place to go. In the summer, the boys lay in the warmth of the sand and tanned in the sun. No girls allowed! The boys were skinny-dipping.[34]

Guns were in every home as a necessity, not recreation. Fathers and sons hunted for food, and serious respect for weapons was paramount. Melvin instructed his boys to especially leave the shotgun alone. Floyd, at age eleven, thought he was old enough to hike down by the creek and get a prairie chicken or partridge for supper. Despite his father’s warnings, he took the shotgun and walked toward the stream. As he approached, he sat on the ground to look around, watching for any movement of the birds in the grass. He laid the gun down beside him, and the trigger caught on a sturdy dry weed, and it went off. The recoil from the shot spun the gun around and a second shot went off as the barrel struck Floyd in the leg like a swinging baseball bat. The incident scared Floyd, and he went directly home. It was a situation that could have ended in tragedy, but it reinforced his father’s admonitions, leaving Floyd with a lifetime respect for firearms.

Floyd was around twelve years old when he decided to run away from home since “no body loved me.” His father, at age eighteen, tried the same thing in his own North Ogden youth and knew what would result. Eva asked Floyd where he planned on going. He didn’t know, but he figured he could live with friends. “Just let him go,” Melvin told Eva. His father rolled up an old blanket with some of Floyd’s belongings and put a rope around it. The plan was that after school Floyd could take his things and leave to live with his childhood allies. Later that day he left home, heading south around the block, but he didn’t get far. He sat down on the hill overlooking the creek and cried. He gazed at the old creamery where the farmers sold their milk for butter and home delivery. He thought of the crystal-like garnet pitcher his mother filled with buttermilk from the creamery for hot breakfast pancakes. The recollections sent him home. When he walked back in the house, his mother and father there waiting for him. “I love you,” Floyd said. He did not want to live with a friend, “I want to stay here.”[35] Years later, Floyd would teach a similar lesson to one of his own sons.

Learning Responsibility

Melvin was strict with his boys. Floyd learned to work while he was a youngster. He and his brothers worked around the home, doing their part as members of the family, whether milking or helping their mother in the garden. Like all boys, they preferred fun over work.

Daily milking was required if you wanted the cow to produce milk for the family. In preparation, Floyd led the cow out of the barn each morning and down to the creek for water. He liked to jump up on her back and ride to and from the stream. One day, Howard Fletcher wanted to ride with him. Unfortunately, someone kicked the cow, and she ran under the fence. The fall cut Howard up a bit. He ran to his mother for help, and Floyd ended up in trouble.[36]

Floyd has a haunting memory of when he was twelve and failed to help his mother when she was pregnant with Douglas. Melvin pitched a tent outside for Floyd and Mervin so Eva would have privacy. The two boys were out there for a few weeks, thrilled that they were camping. One morning, Eva called Floyd, asking him to pick some peas from the garden for supper. Floyd knew what he was supposed to do, but the temptation of friends who were headed down to the swimming hole was too much. Fun won out that day, but not without consequence. When Floyd returned from swimming, his mother was feeling worse because she had strained herself picking the peas. She was in labor, and Douglas was on his way. That night Floyd’s father, Melvin, took his son to the woodshed. Many a time the boys received a thrashing with a willow from the yard for their misbehavior. “I can still feel it to this day around my legs.”[37] The next morning, Floyd and Mervin went into the house and met their new baby brother.

When Melvin started the movie theater, Floyd was expected to deliver the movie films. The train station was about a mile north of their home, and the multiple film reels were heavy. Melvin devised a two-wheeled cart that he hitched to their pony so he and his brothers could easily pick up and return the films sent from Calgary to Magrath by rail. If they missed the deadline, a fee was assessed, so punctuality was a part of the lesson. Generally, the conductor waited patiently, and when he saw them coming, he teasingly scolded, “You Godfrey kids have got to hurry up. I can’t hold this train just for you.”[38] In his late teens and into his early marriage, Floyd progressed from film delivery to projectionist and earned his Third Class Projectionists’ License.

Washing the clothes was a rigorous Monday affair that required help from the whole family. The boys were expected to gather their own clothes and help wash all of the laundry. In the days before electricity, the clothes-washing machine featured a large wheel or lever on one side. The Godfreys’ had a wheel model. Two boys took turns keeping that wheel spinning so the machine could agitate the clothes in the tub and clean them. This was tiring physical labor. Each took ten minutes at the wheel while the others rested. They kept up this rotation until all of the clothes were clean and hung on the outside line to dry.

Clothes washing was different after their dad purchased his Model T Ford. The boys and their father dreamed up a washing machine idea that proved to be a labor-saving one. With their father’s help, they backed the car up to the washing-machine, hooked a wide, heavy leather belt around the car’s back tire and placed the other end of the belt around the wheel of the washer. “You’ve never seen a washing machine move so fast in your life. I think it about shook the machine to pieces.” But it worked. “That was the first power washer” in the Godfrey family.[39]

As teenagers, Melvin pushed his boys to find full-time summer work during the farm harvests. A successful harvest was critical to the Canadian farmer. Grain crops, wheat oats, and barley required a lot of work to harvest. The fields were worked largely by hand. Like all farm workers, Floyd and Mervin cut and then bunched the grain into bundlers. The bundles were then stooked, or set up in groups for drying, and then taken to the thrasher.[40] “A boy is not worth his salt if he doesn’t know how to work,” Melvin said, and work the boys did.[41] Their goal was to earn a little winter spending money and buy their own clothes. Floyd was fifteen years old when he traveled with his brother Bert and later Mervin. They worked on farms in Raymond and in the foothills west of Cardston. The ranch of Richard Bradshaw was among the first that provided work. The Bradshaws had moved from Magrath to Cardston and purchased a part of Charles Brewer Ockey’s ranch.[42] They harvested hay for winter feed, and the farmers sold grain to the elevator operators, who shipped it across the country. Harvesting took teams consisting of laborers, horses pulling the cutters, and the hay wagons. A cutter mowed the hay, creating wind rows. After it dried, farm workers such as Floyd and one of his brothers walked on each side of the wagon and used pitch forks to toss the dried hay up into the hayrack. There were no bailing machines, and there was no stopping to rest for a drink. There was a water jug sitting in the sun at the end of a line that was sometimes a half mile long. It was appealing to the boys, who were always thirsty from the workout in the summer heat. The hay was either loaded in the wagons and driven to a nearby haystack for storage or to the barn for immediate use. During the winter, the hay was loaded back into a wagon, driven over the frozen pastures, and scattered for the animals.

Harvesting grain was a little more challenging than harvesting hay for the animals. The work was defined by the size of the field and the yield of whatever crops were harvested. The grain was first cut and bound by hand or a mechanical grain binder and then laid in wind rows across the field. The job was to create a stook, seven to ten bundles together in a sheave; it got its name because it looked something like miniature teepee-shaped bouquets called stooks. The bouquet shape made the grain dry quicker. If a thresher was unavailable, the workers cut the grain with a scythe, a long sword with the blade forged into a C shape. The swing of the farm worker’s arm cut the grain and helped gather the stalks together. The stalks were long and heavy. The stooks were tied together by hand with binder twine just above the center of the straw below the grain. The first stooks stood exactly vertical. Then others were placed around them, leaning into each other. This was stooking the grain. It was not casual nor unskilled labor. Stooking the grain was dirty, hard, and long work. Each bundle weighed perhaps thirty to forty pounds, and by evening the workers’ hands were cramped from picking up and tying so many bundles. One thousand acres would produce hundreds of stooks. Proper stooking protected the harvest from rain while the grain dried and finished ripening prior to further harvest.

Once dry, the granulated seed was extracted from the straw and husk with a new separator machine. These early mechanical separators were about thirty-five feet long, five feet wide, and six to ten feet high. The whole rig was drawn by a team of horses. This involved Floyd, Bert, and Mervin tossing the bundles of stooks up onto the separator belt that fed them into the thresher, where it removed the dust and shook the grain stalks violently, separating the seed from the husk and the stalk.[43] Floyd enjoyed this dusty, heavy work. Working with his brothers created lifelong memories and strong relationships between them.[44]

On the Lockmans’ farm, Floyd was assigned to the threshing crew. The crew pitched the sheaves of grain on a bundle rack moving up and down the fields by a team of horses. When the rack was full, the sheaves were hauled to the separator and fed along the belt through the machine. If the crew was in a hurry, then too many bundles would overload the machine, stopping the engine. Then one of the men in charge, the threshing operator, would dig out the jammed straw and restart the engine. It was a good way to get ten or fifteen minutes’ rest before they could go again. Floyd’s reward for the backbreaking work was one cent per harvested bushel ($0.13).[45]

Good cookhouse meals were provided for the hungry crew. They included steaks, vegetables aplenty, cold milk, and pies of every kind: “You name it, our cook could prepare it,” Floyd reported.[46]

Within a few years, Floyd was promoted to handyman on the harvesting crews, more commonly known as a roustabout. Floyd was paid $7.50 ($97) per day, and he thought he was rich. He did whatever the boss wanted done. He went to town for groceries, transported the boss to the next farm to secure the next job, got repairs done, posted the mail, took the men to and from the fields for their 3:00 p.m. lunch break, and helped the supervisor and the engine man on the thresher. The job and the harvest were intense and lasted only for a month or two at summer’s end. Then it was back home and to school.

Floyd learned the meaning of work early in life. He earned his longtime job at the Magrath Trading Company as a result of his reputation for honesty and hard work. At the trading company he started as a delivery boy and worked as hardware clerk. He did this ten years into his marriage, through to the mid-1930s and into the Great Depression.

Loving Disciplinarian

Floyd admired his father’s courage and work ethic. The two had a good relationship. Melvin was energetic and at times also “very emotional . . . and had a tender heart.”[47] He taught work by example and discipline. Coming home from Calgary after municipal meetings, Melvin asked for little Floyd to meet him at the train station. They had one of the few telephones in town because Melvin was the marshal. Floyd was not yet in school and was unsure what to expect. Melvin told him to go and look in the baggage car, “There is something for you.” Floyd ran excitedly down the station’s wooden platform. In the baggage car he found an iron-wheeled red tricycle with his name on it. He was thrilled. Melvin likely thought the gift was to share with Floyd and his younger brothers, Mervin and Joseph, but “my name was on it,” and he felt like one special little boy.[48]

Melvin created memories for his boys even when it would have been easier to work alone. He took Floyd out for a day on a forty-acre plot he thought he might buy near the Magrath graveyard. Floyd took a sack lunch, and they went together. Worried about the gophers getting his lunch, Floyd placed it on the fence post for safe keeping while they were working. He didn’t notice until it was too late, but a wild donkey had come along and eaten his whole lunch, bag and all. So his father shared his lunch with him.

As the town police officer, Melvin created unique teaching moments with his children, whether it was ringing the curfew bell or just riding along with their father. On a legal outing, Floyd went to Spring Coulee to repossess a sewing machine. Floyd was an impressionable seven-year-old. As they approached the home, the owner stepped out of the house, striding toward the gate with a shotgun in his hand. “Godfrey, I know what you want and you’re not going to get it. I’ll blow your head off if you come any closer.” Floyd was petrified, but Melvin never slowed his pace, “Now . . . you wouldn’t do that. . . . I’m here for the company. . . . I know you’re having a hard time.” After a few minutes of conversation, the stand-off ended and the man put down his gun. “Hell Melvin, come in and get the darn thing.”[49]

On a later trip to Spring Coulee, Melvin drove with Floyd in his Model T Ford. The road was rough, and they sheared off the axle, forcing the father-and-son team to walk down the railroad track back eleven miles to Magrath, where they could get help to retrieve and repair the car. Floyd wrote of that experience, “Dad and son were never closer.”[50]

Melvin wielded a great influence on Floyd. He molded him from a shy boy into a confident young man unafraid to reach out. His often-repeated line was, “You can, if you try hard enough.” He instilled enthusiasm in his son and the significance of bringing a project to a successful conclusion. His acts of bravery were indelibly impressed on Floyd’s young mind.

Some would not describe Melvin as a religious man, but he had a love for the gospel. He was in the elders quorum presidency in his ward. He had the solemn responsibility of caring for the dead and preparing them for their funeral and burial. He was always there when family needed him, leading, directing—sometimes rather firmly—and he was outspoken in his beliefs.[51] Everyone knew where Melvin stood on any issue. He was a fair man in all his endeavors as a police officer, a judge, a theater owner, and a grocer.

There was never a doubt that Melvin loved his family. He twice sacrificed his own safety saving Floyd’s life. The first lifesaving incident occurred in Magrath when Floyd was small. Melvin had picked up extra work putting up hay for the Eldridge Cattle Company. There were severe storms in the area that spring. Heavy rains and melting snow filled the coulees, canals, and streams. Melvin was concerned that the hay he had recently cut would rot on the wet ground, so he headed to the Bradshaw siding to check the field. On his way, he crossed a small ravine that usually held only a trickle of water. However, this time it was a raging river. Melvin’s horses hesitated until he gave them a crack with the reins. They moved forward and disappeared into the water. Midstream, the horses’ heads were all that could be seen. Then the buoyant wooden wagon box came loose from the wagon frame and began to float downstream in the swift current. Melvin was holding the horses while his sons, Bert and Floyd, floated away in the wagon box. Without hesitation, Melvin dropped the reins and swam with the current, catching the box and its terrified passengers. He took Floyd, then Bert, and literally flung them out of the wagon onto the soft wet bank. Then he fought his own way to the edge of the ravine to recover the horses. They had escaped and were waiting for Melvin to come and find them. It was a dramatic rescue.[52]

A second rescue occurred in the summer of 1919, when Melvin and Eva took the family to Waterton for a week. Waterton-Glacier was described by George Bird Grinnell as “The Crown of the Continent,” with watersheds feeding the Atlantic, the Pacific, and Hudson’s Bay.[53] Floyd, now thirteen, had heard about the wonders and the beauty of this spot, where mountains supposedly reached into the sky. It was hard to imagine, so he was anxious. And Melvin wanted to show off his new Model T Ford.

Melvin left his two oldest, Bert and Lottie, in charge of the theater. He then took Floyd with his two younger brothers, Mervin and Joseph, packed groceries, frying pans, and everything else into a large wooden box and loaded it into the car along with quilts, pillows, clean clothing, a shovel, and bamboo fishing poles. Melvin cranked and cranked. The engine sputtered to a start, and they were off. The car was running, but the boys had to wait while their mother checked the stove one last time and instructed Lottie on the danger of fire.

Heading west, the roads were rough and dusty but graveled. They were used mainly by farmers, lumber wagons, and oil entrepreneurs hauling building supplies, equipment, and pipe into the mountains near Cameron Lake. There were no bridges, and the family crossed the St. Mary’s and Belly Rivers where they could find shallow rapids. Reaching their halfway point, Cardston, the rear wheel of the car collapsed under the extra weight. The wooden spokes and the wheel rim broke. They hiked to the nearest farm house and found a telephone, and soon Mr. Low came with a new wheel and got them on their way.[54]

As the family left Cardston, they got their first glimpse of the mountains. Chief Mountain stood out, invitingly majestic. They kept moving and finally camped at the park entrance and registered at the office. The hills were green, the water clear and refreshing. Exploring everywhere, they hiked from their camp on Crooked Creek. The fish were so plentiful they actually shoveled the white fish out of the water. At night, the boys spread their bedding and quilts. Melvin and Eva sat by the campfire, just talking and laughing. Every day was an adventure for Floyd and his brothers as they trekked down the paths left by the deer and mountain animals. One day they had hiked quite a distance from the camp and stopped for supper. Melvin cleaned the fish and was preparing supper when he could not find the frying pan. He improvised. Using a short-handled shovel, he cleaned it in the sand, washed it off in the creek, greased it up, and soon the fish were sizzling in the shovel over the fire. They returned to camp tired but well fed. Building a raft and heading out to the end of Waterton Lake was the plan for the next day. That idea was vetoed by Eva: “In no way are my sons going on that water.” The plan was revised to a hiking excursion to Cameron Falls, which was equally exciting.[55] The boys pleaded with their father to go the next day.

They slept quietly under their denim quilt with mom and dad close by, only the food box separating boys and parents. They were sound asleep and woke immediately as a bear searching for food began tossing knives, forks, and plates across the camp. Two stunned parents with three scared boys sat straight upright from their deep sleep and in unison let out a loud scream. Their scream startled the bear, and all that the boys could see peeking out from under the covers was the bear’s retreat. For an excited and still-shaken group of children, the sun rose slowly as they anticipated the hike to the falls the next morning.[56]

Melvin explained that the unique geography of the falls was formed by a steep cliff and rocks plunging deep into the earth. The falls were actually created by older layers of rock, which over the centuries were displaced by the pressure of upper layers of new rock, giving it a dramatic angular presentation of water and rock.[57]

Breakfast that morning was hotcakes and eggs. “We’ll wash the dishes when we get back,” they told their mother. Eva made jelly sandwiches, with carrots to chew on the hike. The kids stuffed their pockets full of cookies and picked out a walking stick to fight off any wild bears encountered on the seven-mile hike. They marched up the hills and forged the Waterton River and Blackston Creek. It seemed like a long hike. They had heard so much about the falls that when they arrived it was “almost, to we boys, like one of the seven wonders of the world. . . . The falls were massive. The huge cliffs rose [and] excited the opportunity to climb.” They cooled their feet in the pool at the base of the falls as they watched the waterfall. But they were not content to sit too long. They coaxed their reluctant father into going with them to climb the face of the cliff at the top of the falls. He agreed so long as they followed in his footsteps.

They made it to the top but needed to descend downward just a little to reach a lookout point above the falls. When they reached the point, they were again delighted at their view as the water thundered over arms of the very rocks on which they were standing. They sat and stared into the deep pool carved by the falls below. They inched a little farther along a large, flat stone outcropping where they could get an even better view. “Floyd, Mervin, Joe . . . come away from that edge,” Melvin instructed. The rock at this spot was slanting down at about a thirty-degree angle. There were small slivers of water dripping over the stone face right where they stood. They were too close to the edge, but it was spectacular. Floyd was trying to discover the source of the water noise when his feet slipped from under him and he began sliding toward the falls. He was going down. Melvin had been watching about ten feet away and immediately plunged forward prostrate on the west rock in front of Floyd, just as Floyd slid straight into his dad “with a thump.” They both stopped at the very edge of the roaring falls. “Take off your shoes, son,” Melvin directed, “and creep to that trail above.” With hearts racing, they dragged themselves back to the dry rock. Melvin was frightened, Floyd was shaking, and his brothers had already scampered back down to the creek below. Not a word was said between the two as they climbed down the fall’s cliff and hiked back to camp. Melvin reported to Eva, “The boys enjoyed themselves.” She did not find out until later what had actually happened.[58] In writing about this event, Floyd commented, “I have never thanked him [for saving my life]. I would like to do it now, but he is long gone. When I see him over there, I’ll do this thing and I supposed he will laugh about it.”[59]

Church and Family

Cameron Falls, circa 1925. Courtesy of Cardston Court House Museum Archives, Wolsey Collection.

Cameron Falls, circa 1925. Courtesy of Cardston Court House Museum Archives, Wolsey Collection.

Eva always threw her arms around her children, hugging them and teaching them to love and pray. She had a firm testimony of the gospel. She was as firm as she could be with eight children. If a child was too slow at following Mother’s directions, it was Melvin who applied the motivation and the rescue. Eva pushed them to attend their Church meetings and involved them with learning and activities that taught them spirituality. Bert would serve a mission in the eastern states, spending most of his time in Vermont. Floyd would remain home to work in the theater.[60] Eva reinforced the principles of honesty and hard work that Melvin taught and that they both had learned in their youth and from pioneering parents.

It was a bright sunshiny day on 7 June 1914, a day Floyd had been anticipating for a long time. The chapel had no baptismal font, so the ordinance took place in Pothole Creek, near today’s Magrath Park. It was two months after his eighth birthday. His mother had scrubbed him clean for the event. He was not sure why, because he was a boy of eight who swam twice a day in the creek and did not see the need for all the scrubbing. The air was cool, so his mother put him in a pair of fleece-lined underwear, a clean pair of overalls, and a clean shirt. He and his dad hitched Old Kate to the single-horse buggy, and they all rode to the creek. Floyd waited his turn and walked down into the water with his father. It was summer, but still cold, and when he came out of the water he was almost stiff because the clothing his mother had him wear was now soaked. She took him and wrapped him in a blanket, and he stood while Bishop Harker confirmed him.[61] Afterward, the family hurried home. His mom, who feared he would get pneumonia, changed him into dry clothes. “She was a wonderful mother.”[62]

It was a proud day for the eight-year-old. He was proud to be a member of the Church; “I feel (really) this was the beginning of church activity in my life.” He was now expected to live, serve, and help more in Church activities. He had always had something to do, but he now felt the duty.[63]

The Children’s Primary

Eva took Floyd and all her children to Primary when they were young. Idell Jane Toomer was an influential Primary teacher in Floyd’s pursuit of those things sacred.[64] “A little smart for his britches,” one day he ran into the church classroom, stepped on the bench, and jumped up into the window sill to sit and listen to the lesson. He was at the center of attention, but it was a different lesson that day. Sister Toomer saw him sitting in the windowsill, grabbed hold of his feet, pulled him out of the window and sat him down so hard the bench broke. Afterward, Floyd was the ideal of reverence and remembered Miss Toomer as “the best teacher ever.”[65] She disciplined him “very harshly, which I needed, but I loved her.”[66]

Elmer Ririe was the Magrath First Ward bishop during Floyd’s growing years.[67] Louisa Alston was Floyd’s Scoutmaster.[68] Although Scouting was not as prevalent in the LDS Church during the early 1900s as it is today, it was a social experience. Floyd was a patrol leader in his troop when Mrs. Alston planned a special outing for the children to see Lord Beaverbrook, who was coming to Lethbridge. William Aitken Beaverbrook was a famous Canadian and British author, businessman, and politician.[69] The Scouts went to Lethbridge on the train. It was snowing and cold the night before the dignified British lord was to arrive. It was still snowing the next morning. Nevertheless, the Magrath Scout Troop stood in full dress uniform (short pants and bare legs), with their Scout staves, standing at attention on the train station platform as the lord stuck his head out the train window for a minute, waved a celebrity “hello and goodbye,” and that was it. Though it was only for a few seconds, the Scouts enjoyed being that close to such a celebrity.[70]

Learning Honesty

Honesty was a characteristic that paid dividends, as Floyd learned from both his mother and father. The dividends for his honesty were realized quickly when he was digging a trench for Richard Bradshaw. They had agreed on a specific price for the work, and when the job was completed, Bradshaw wrote a check for more than the agreed amount. When Floyd pointed out the error, Bradshaw gave him a corrected check. He was out at his front fence making this exchange when Alfred Ririe, owner of the Magrath Trading Company, happened to be passing by, and Bradshaw hollered at him, “Alf if you want a good man to work for you, here is a real honest fellow.” Ririe hired Floyd that same week, and he worked for the Magrath Trading Company for the next ten years.[71]

Floyd was fifteen when he started working a weekend job at the Magrath Trading Company. His first responsibilities were assisting the man who delivered the groceries and dry goods to local customers in his horse-drawn wagon. One Saturday, Floyd was cleaning and closing the store. He was working behind the counter. This was a long cupboard-style counter where parcels were wrapped and groceries bagged for delivery. Inside the counter drawers were bulk products: rice, raisins, current berries, coffee, and dry products. The customers made their selections, and workers scooped out the order into a paper bag and weighed it. On one evening, at the end of a busy day, the floor behind the counter was particularly messy. Spills from the scoops, labels, old paper bags, and a mess of scrap paper covered the aisle. Floyd’s job was to sweep, clean, and separate all the paper into the burn box. As he swept, he found a $20 ($254) bill on the floor behind the cash register near the telephone. A thrill shot through his body. He hesitated, then hastily picked it up and put it into his pocket, wondering if anyone had noticed. It was late at night. He finished cleaning the store, closed shop for the night, and hurried home to tell his mother of the treasure he’d found and all the things he could now buy for himself, along with a present for his mother, of course.[72]

Floyd waited until he could talk alone with her and then told her of his good fortune. She listened quietly and asked, “Do you really think that is your money?” In his excitement, that question had barely registered with him. He thought about it, and he realized she was right. Eva paused for the right words to teach honesty and the Golden Rule, “Floyd it is not yours, it belongs to the store.” After a few tears of disappointment, he knew what he must do. The next day was Sunday, but early that Sabbath he was at the door of Ben Hood, who was in charge of balancing the cash register receipts at the store.[73] Floyd was nervous as Hood answered his door, but he did as his mother directed. Hood questioned him about the find. Truth be known, Floyd was proud to be honest. Hood explained that he had been unable to balance the books that evening, he was $20 off and preparing to make up the difference out of his own pocket. He was grateful that Floyd had returned the cash, advising him, “Always listen to your mother.”[74]

Eva loved the gospel and planted it in Floyd’s heart. He attended his Primary, Mutual Improvement Association, Sunday School, sacrament, and priesthood meetings as expected. He was the deacons and teachers quorum president. He would marry in the temple. Eva and Melvin instilled the lifelong regard for ethics, honesty, and hard labor into their boys. These were the never-ending lessons of their lifetime, passed from generation to generation.

Frontier Public Schools

At age seven, in the fall of 1913, Floyd started elementary school. The school was a four-room, two-story, square wooden structure that faced south, with a belfry dominating the front of the building. The school was in the center of town about two blocks from Main Street and a block and a half from Floyd’s home. There were two classrooms on each floor and two windows on the east and west sides of the building.[75] Two outhouses were behind the school and just beyond a small barn housing the horses students rode from nearby farms into school. The blackboards at the front of the room were small, and the pupils sat two to a desk. There was a two-inch hole drilled through the center top of the desk for an inkwell, which held a small glass bottle of black ink. A young lady sitting in front of a spirited young male might get her braids dunked into an open inkwell. Pencils and straight pens were stored in grooves cut on each side of the inkwell. Books were stowed under the desktop.

Within a few years, a second, much larger brick building was constructed under the supervision of Daniel T. Fowler, with the assistance of Melvin Godfrey.[76] The old wooden schoolhouse was abandoned, and “it became the local ghost haunt.”[77] The new structure had sixteen rooms and until 1930 served for both the elementary and high school students.[78] The curfew bell was retained from the old school and placed atop the new structure. It was here that Floyd climbed the stairs with his father to ring the nightly curfew. The bell could be “heard for miles, especially in cold weather.”[79]

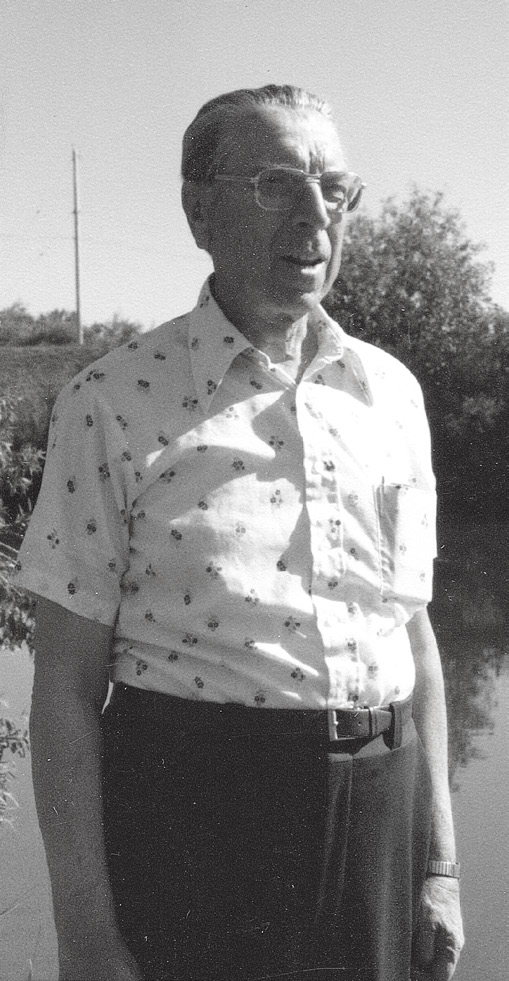

Top and Bottom: Floyd Godfrey, at Pot Hole Creek, where he was

Top and Bottom: Floyd Godfrey, at Pot Hole Creek, where he was

baptized in 1914. Courtesy of Donald G. Godfrey.

Floyd’s education took place in both of these school buildings. In the old school hall he would often sneak into the attic at night, nervous but determined to catch a pigeon from the flock that nested in the rafters. He climbed to the top and crawled his way through the trusses, feeling his way to where the pigeons nested. The pigeons couldn’t see the boys, and the boys couldn’t see the pigeons. It was too dark, but the boys heard the cooing. They followed the sound and the birds were easily caught. They would crawl in, reach out, grab one, and carefully cross the wings so that the struggle the birds were unhurt. Then they would place them in a gunny sack and head home. Floyd fed and watered his captives in a box he kept in his father’s barn. Within a few weeks, they were his pet pigeons. “I remember I had so many in the top of our barn, they were spoiling the hay. Dad was not too happy.” He seemed pleased when one night some boys from across town snuck in and stole most of them.[80]

Elementary School and War

Elementary school between 1914 and 1918 was about reading, writing, and arithmetic, along with military training. World War I began 4 August 1914, when Britain declared war on Germany, and Canadians of British ancestry supported the war.[81] War was frightening even for those not on the front lines. In addition to scholastics, the boys at the Magrath schools were marched to the north side of the building, where in the park they trained using wooden guns to be the soldiers of the future. This was World War I preparation for service and possible attack. Floyd and his classmates were taught how to lay prone, run, drop, and shoot in one motion. After the outside exercises, they went to the school basement for target practice with 22-caliber rifles. The Canadian Army almost immediately began recruiting. Floyd was eight, obviously too young, but he felt the strain. Farmers were in the middle of their harvest. “Men from 19-40 Your King and Country Needs You,” the posters advertised.[82] Patriotism was strong among the Mormons, no matter which side of the border they settled.

Prior to the war, a recognized LDS southern Albertan, Hugh B. Brown, had handpicked men to serve with him in the “C” Squadron 13th Mounted Rifles of the Canadian Overseas Expedition Force, the “COEF” of Calgary.[83] Eventually, sixty-six soldiers from Magrath served in World War I. Six were killed in action. The town’s population would have been around nine hundred people.[84] Emotions were high everywhere, and Magrath was no exception. German Kaiser Wilhelm II, blamed for starting the war, was depicted as a straw man, like a scarecrow standing in the fields. The town built a mock scaffolding from which they hung the strawman, set the hay on fire, and burned him in effigy. It was a patriotic action repeated across nations.[85]

Floyd was blessed to miss both wars. He was too young for World War I and too old for World War II.

High School in the Roaring Twenties

World War I ended and history moved into the Roaring Twenties as Floyd reached high school age. US President Woodrow Wilson characterized the 1920s as moving from war “Back to Normalcy.”[86] Canadian author Pierre Berton implied that as a result of their success in WWI, the “Canadians were a cocky lot in the twenties.”[87] They kicked up their heals dancing the Charleston, and the morals and manner changed in the decade.[88] There was no such thing as cinema. Early film was experimental, moving into the ’20s with silent film entertainment.[89] “There was no such thing as radio broadcasting.”[90] Stations were experimental, and technology was just developing before the radio boom.[91] This was the environment of Floyd’s teenage growing years.

Magrath High School. Courtesy of Magrath Museum.

Magrath High School. Courtesy of Magrath Museum.

High school changed Floyd’s life. He broke free of his boyhood shell. He started noticing girls. Following the encouragement of his father, he went to work outside the family, earning his own money. He worked harder and grew respectful and “more considerate of his mother and father.” If Floyd asked his dad for a little cash for a weekend date, he knew the answer before he asked: “How do you suppose I got mine?” Melvin responded.[92] Melvin’s boys got what they needed in terms of home, food, and shelter, but they had to earn their own spending money and pay for school clothing.

Floyd remembers his instructors fondly and fell in love with the beauty of his first grade teacher, Miss Parish. Floyd appreciated all of his teachers, including Miss Sutherland in grade four; Drew Clark, grade five; Ammon Mercer, grade eight; Drew Clark and Nephi Head, grade nine; Mr. Pharis and Miss Redd, grade ten; and Golden Woolf, grade eleven.[93] His high school teacher Golden Woolf survived Floyd’s pranks and instilled in him the idea that he could accomplish something if he would apply himself.[94] In high school, a group of friends in his science class decided to play a trick on Mr. Woolf involving chemistry and electricity, which they were studying. From inside the classroom they created a battery and connected it to the doorknob. As Mr. Woolf approached, the boys poured water under the door. Of course, when Woolf grabbed the doorknob he was shocked and could not let go. Several students, including Floyd, were temporarily expelled. Ironically, Mr. Woolf, who later became the principle, reached out when Floyd was in the eleventh grade, giving him the responsibility to monitor the twelfth-grade chemistry class. Woolf’s assignments and mentoring gave Floyd confidence to be trusted, and the prank was forgiven.

Floyd competed in debate and won several awards. One judge thought he might have even been more effective if he had only stopped pacing back and forth behind the podium during his speech. “Well done, now young Godfrey, had a good talk if he’d just stand still.”[95] Floyd’s favorite subjects were geography, math, chemistry, and the study of foreign countries. He did not care for English or grammar.

Floyd played the clarinet in the high school band. “My dad wasted a lot of money on me playing the clarinet,” Floyd said. He “hated every minute of it,” but his mother was persistent.[96] The day his band leader tuned all of the instruments to Floyd’s clarinet’s middle C bolstered his confidence, and he continued with the instrument several years. The Magrath Band performed around the town for the 1 July “Dominion Day” parades and celebrations. Dominion Day was created to celebrate Canadian independence, 1 July 1867. It was changed to Canada Day 27 October 1982.[97] Band members were up at 4 a.m. A loud cannon announced the beginning of the day, and the sixteen-member band rode round town in a hay wagon decorated in red, white, and blue, along with the Union Jack (Canadian flag at the time). All climbed aboard the wagon with their instruments and kitchen chairs borrowed from their mothers’ tables. The wagon was drawn by four beautiful Clydesdale horses, a powerful breed used to pull heavy loads. They stopped at the corners of the town blocks. Sleepy people emerged out of their houses for the national anthem, “O Canada,” or a rousing march. Spectators sometimes brought the musicians a cake, which delayed their progress as they ate. It was a morning revelry lasting until 6:30 or 7:00 a.m., after which the band left to prepare for the big town parade down Main Street, and the townspeople readied themselves for the celebrations.

Floyd might have thought the clarinet was a waste, but the band added to his self-confidence and gave him an appreciation for John Philip Sousa and good music that he carried all his life. As an adult, he loved the town celebrations, rodeos, and parades. He sang in the ward choirs and around the house. If he knew the melody but had forgotten the words to the song, he would just invent them and keep right on singing.

Dating, Dancing, and School

Teenage Floyd was initially a reluctant dancer. His mother had tried to encourage him during a community-wide assembly hall dance, but he clung onto the post of the balcony for dear life as she pulled him onto the floor. Drucilla Passey, a young girl his own age, was a little more persuasive.[98] He didn’t like it at first, but he warmed to the notion as he began paying attention to possible dance partners.

It was about this time he started noticing the girl across the south fence from his home— Clarice Card. As teenagers, she and her girlfriends generally attended the dances alone, but as they matured, a boy would escort them home. Floyd saw Rose Bennett, May Sabey, and Clarice home from various dances. Sometimes they all came home in a group. Occasionally, Clarice was escorted by Reed Bennett (Rose’s brother) and Floyd.[99]

Dancing with Floyd was quite the Charleston experience. He was always into the swing of the music, carefree and fun. Chaperoning adults sat on the sides of the dance floor and watched with a careful eye. These new freestyle dances were far different from those of their parents, which were more rigid.[100] Floyd and Rose were dancing one evening when her petticoat suddenly fell to the floor. Rose was faster than the eyes of the chaperones. She leaned over, quickly pocketing her undergarment, without missing a step.

Floyd was a cutup. He loved a teenage good time. After a dance or a movie, revelers all headed uptown to the Jones Bakery, where ice cream and pie topped off the night. The dances were, of course, all chaperoned by the mothers of the community, who positioned themselves on the stage where they could watch and make sure their teenagers behaved. After a dance one evening, Floyd’s father asked if he had been drinking alcohol at the dance. “No, I have never drank in my life,” Floyd responded. “Well,” his father replied, “somebody said you were cutting-up at the dance last night.” Floyd had indeed led a chain of dancers, holding on at each other’s waists in the bunny-hop fashion all around the dance floor while chanting to the music. “There must have been 150 of them following me,” Floyd recalled.[101] Floyd’s teenage memories of fun and frolicking stayed with him as he enjoyed life.

As president of the student organization, Floyd was at the forefront of those organizing the parties and dances throughout the year. They relied on lots of teenage creativity generating their own entertainment. One Halloween night, Floyd and fellow students constructed a tall water slide where students slid down and landed in an old sofa at the bottom. It was fun until one of the girls broke her leg. Every event featured the Magrath High School song. There were no radio stations and few record players, so the dance bands were local and live. Their only entertainment beyond Floyd’s father’s Empress Theater were dances, school, church, and community socials.

In the late 1920s few students finished high school. Most completed the eighth grade and headed for the real-world work opportunities. A small group graduated, but most were unable to afford university studies. Floyd finished the eleventh grade. His high school experience in leadership and academics had helped him out of his shell. He was a member of the student body leadership. He mixed with the girls and worked summers in the harvests. He was evolving into an adult with a new respect for the wisdom of his parents.

Frontier Holiday Celebrations

In pioneering days, holidays were comparatively few and all locally organized. Even then there were chores to be done, cows to milk, and animals to feed before the fun began. The national holidays were Dominion Day, Easter, and Christmas.

Dominion Day, 1 July, is the celebration of Canadian independence from Great Britain in 1867. Magrath’s commemoration started at sunrise with the firing of the cannon, followed by the band touring the town, the parade, and the evening baseball game and feasting. The parade floats were farm wagons decorated with Canadian flags and red, white, and blue crepe paper. They were organized by local groups and included a few of the businesses.

Baseball games featured regional competition. In the Godfrey tradition, Floyd was the catcher for the team, as his father had been earlier. Once he caught the ball on the end of his fingers and split them, after which he was not too fussy about being the catcher. Games were mostly a social event and were played in every community. The teams piled into a wagon or the car as they rode into neighboring towns to play ball. The evening concluded with more food, more dancing, and the singing of “Oh Canada.” Dominion Day was a highlight of the year.

Easter and Christmas were more family celebrations. School was dismissed for only Good Friday and Easter Monday. Hiding and finding Easter eggs was unique to a child’s memories of these days. Floyd, with his brothers and sister, checked the chicken coop and selected one or two eggs each day. They hid them in the barn until Easter, and by then they might have a dozen eggs each. Eva hard-boiled the eggs and colored them with food dye for her children. For the finale, they walked to the coulee hill, just a half block south of their house, and rolled them down toward the stream.[102] The prankster in Floyd appeared one year when he found a fresh egg and slipped it into the pocket of one of his sister Lottie’s friends. He thought it was a big joke when he kicked her pocket. However, the joke was on him! As she reached into her coat, retrieving what she could of the broken egg, she threw it right in his face.[103]

Christmas was the most exciting children’s holiday of the year. Eva decorated the house with brightly colored green and red crepe paper. The children cut paper into strips and created paper chains that hung from the ceiling. The chains were draped from the corners of the room to the center where Eva placed a large decorative Christmas bell. Eva and Lottie did most of the decorating. The family popped corn on the stove in a wire basket. Shaking the basket over the top of the red-hot coal was intriguing, as the kernels of corn exploded. After it cooled, the children took a needle and thread and crafted long strings of popcorn cascading around the tree. These were family activities as well as holiday preparations. The tree was likely acquired from the Magrath Trading Company or a local entrepreneur who had a license to cut trees and had ventured into the foothills to Pole Haven or Dug Way on Lee’s Creek near Cardston. They were scrawny trees compared to the lush trees harvested today for the holiday, but in the eyes of the children they were a wonder as they stood in the northeast corner of the front room.[104] There were no lights on the Christmas tree, as there was no electricity. Eva and Lottie cautiously placed and lit the candles on the branches. Eva’s memories of the fire in her childhood home kept her fearful even as an adult. The candles were lit only briefly and not too often. They were placed in a small cup to capture the melting wax and held the flame steady on the branch. There was a large stove with windows on three sides. As the fire burned, it would cast flickering light across the festive decorations and the tree.

Christmas was simple and exciting. On Christmas Eve a small wooden box of Japanese oranges (imported tangerines) appeared. The Godfrey family sat around the stove and ate them all. Often on Christmas Eve the children had to wait for their father, who was patrolling the streets. It was his job to see that the people and cattle were home at night. It was always snowy and cold, but they waited patiently for their father.

One Christmas the snow was twelve inches deep. Sleigh bells rang passed their home. There was a long expectant pause as Melvin dramatically threw open the door, covered with snow, and hollered, “Santa just drove by and may not come back if there are any lights still on, so you guys better get to bed.” The children were already tired but too excited to sleep. They scrambled for their beds. Bert, the oldest, pretended to sleep for a few hours. It was more than he could take. He slid from under the covers and crept “very quietly, into the front room, found his long black stocking” and scurried back to bed. He hid under the covers, took out one orange and one apple, and down in the toe of his sock he found Santa’s present. He had left Bert with his “own cherished dollar watch.”[105]

Christmas mornings the children were allowed to light the candles on the tree. Gifts were simple. Santa brought each child a gift or two: perhaps a pocket knife, a new flashlight, and a doll for Lottie. Eva got Lily of the Valley perfume every year from her son Douglas. Cast iron toy cars came from Santa.[106] Gifts such as a sleigh or a wagon were often shared with one another. Each child had their own stocking hanging on a chair with their name on it. The stockings were filled with apples, oranges, peanuts, homemade candy, and sometimes a package of the new sweet chewing gum. Gifts of clothing were always needed and received. “We didn’t have to have much, but we were happy with what we had.”[107]

Christmas dinner was turkey, dressing, potatoes, carrots, and gravy. Plum pudding, apple pie, and homemade ice cream were dessert. Eva cooked the plum pudding in a cloth and a pot of boiling water. It was a traditional Christmas treat and often called Christmas pudding. It had no plums but was a mixture of dried fruits, hard beef or mutton fat, molasses, and spices—such as ginger, cloves, nutmeg, or cinnamon providing a fragrance throughout the house for several weeks as Christmas approached and their mother prepared.

All holidays were a delightful respite from the physical demands of work, but there were always chores and the cows to be milked both morning and night. They were heartfelt celebrations and a day or two to relax and socialize. They came too slowly and left too quickly in the pioneer lives. Soon the holiday was over and done, and it was back to work meeting the challenges of keeping food on the table.

Frontier Medicines at Home

Pioneers relied on their own knowledge when it came to medicine, and it was no different for the people of Magrath. Healthcare came in the form of herbal remedies passed from previous generations. Accidents and illnesses were treated with a poultice, a tonic, and a prayer. There were no ambulances or emergency rooms. Medical doctors were just beginning to appear in the local communities, and they drove to the homes of their patients to administer their services. Until 1938, child birth generally took place at home with assistance from female relatives, a midwife, or a local physician.[108] For those living in Magrath, if the patient did not get well, the Lethbridge hospital was two hours away by horse and buggy, assuming the family had a fast horse and the patient was well enough to make the journey. Dr. C. W. Sanders was the first doctor in Magrath. He visited the homes of his patients.[109]